|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Edwin Drood's Column > September 2010 |

|

|

back |

Edwin Drood's Column |

|

7 September 2010 |

|

| |

|

| The best years of our lives |

In which Edwin asks whether adolescence may not be overrated to the point that

for many young people this rather underwhelming experience has reduced them

to a state of fatalistic apathy beyond even that common to their age-group.

|

|

When does suicide begin to look like a good option? Obviously those in severe and constant physical pain, the terminally and hopelessly ill, those who are at the end of their emotional tether, worn out by circumstance and the cumulative effect of bad luck and even worse decisions, the lonely and neglected, the deserted and devalued, the publicly disgraced ... all these garner a degree of sympathy when one hears that they have succumbed to their inner voices. “There but for fortune”, one mutters under one’s breath.

There is always a nagging feeling that the rest of us, who dare to continue living and enjoying God’s good daylight have somehow misunderstood them, let them down, failed to intervene, failed to love enough or care enough. But after a while we come to terms with these feelings. There is a limit to the amount of responsibility you can take for someone who is adult and vaccinated.

I for one refuse the burden of guilt by association, no matter how many lines of John Donne get quoted at me. The suicide has made a sovereign, unforced and probably informed decision that they knew from the outset carried wide-ranging implications for their family and circle of acquaintance. “All are punishéd” cries the Prince, but I shrug it off. No, I’m not being hard-hearted. This yoke was thrust upon me and I refuse it. There were alternatives. Depression is an illness, not an excuse. Pain can be managed. Lives can be turned around. The world is full of support groups and networks as never before. Suicide, except in the most limited of cases (medically-assisted and after consultation with doctors and family), is less an act of release than an act of violence against self and others – irresponsible, accusatory and, for all its apparent self-effacement, somehow arrogant.

Irresponsible, accusatory and arrogant are all adjectives that crop up a lot when the subject is the behaviour of the young, so it is hardly surprising that this much courted, cosseted and yet dissected segment of the population thrones so high in the suicide statistics. And here our common liability is clearly engaged, because we’re talking about kids. But is it really the irresponsibility of youth, its accusatory stance against the incomprehension of its elders or its downright egocentric arrogance that is driving the current rise in sudden and dramatic exit strategies?

Well, they’re not dying of love in junior high. The Juliet paradigm is one of the least significant contributors to youth suicide. They’re not dying from academic pressure either, except in China, South Korea and Taiwan. In Europe and North America it is getting easier to succeed at school every year. Educational systems will do anything to improve their statistics, lowering the bar is usually the easiest option. There is certainly bullying and other forms of peer-group pressure that play a role in many cases. But once again, the number of teen suicides with a clear causal link to such behaviour is relatively small. Depression and/or deprivation are often cited as factors: both raise a nest of questions. Why depression, what sort of depression (teen burn-out, chemically induced by diet or brought on by ADD syndrome medication etc.), why now more than before and why the young? And how can the young, on whom the entire marketing and media planet showers its undivided attention, possibly be suffering from deprivation? What are they deprived of and by whom? |

| Madison Avenue wants your teen |

Youth are hardly deprived as a group. They are fought over from the cradle (diapers, creams, powders, medication, clothes, cots, buggies and other baby-kit) through infancy (books, toys, pre-school learning plans, more clothes) through school (books, films, TV, accident insurance, foodstuffs, educational toys, computer programs, games, more and more clothes, entry-level cosmetics, sports equipment) into adolescence (all of the last section but more intrusive to a power of 10 plus counselling services, therapists, career consultants, soft drinks, junk-food, lifestyle magazines, mp3 players, cell phones, laptops) and on up to adulthood by vast armies of marketing experts and trend scouts.

This ever-shrinking population (in Europe at least, the young are endangered by definition) has proportionately more cash and is burdened with less responsibility than any previous generation. The world is their oyster. Potential employers (even in a time of economic downturn) are ready to take them on at the drop of a diploma. Skilled labour, trades and craftsmen and graduates in all fields of professional endeavour are wanted desperately. Those who actually bother to learn a skill, a trade or an extra language are going to find work. It’s that simple. So what’s going wrong?

We used to have wars that culled each generation, leaving the survivors either too shocked to do much more than stumble through the next decade, using work as a distraction, or too grateful to be alive to consider anything other than the fast-track to family and suburbia as the way back to Eden and normality.

But the wars (at least where I live) have thankfully been superseded by a new form of market internationalism so complex as to make all thought of physical aggression against tomorrow’s stakeholders or today’s consumers absolutely unthinkable. We have neither our elected leaders to thank for this, nor the nuclear balance of power nor the end of the cold war. Those responsible for sixty years of peace sit in the same financial, commercial and manufacturing entities that once saw their advantage in war. It’s that simple.

Nowadays war is only a paying proposition in the third world, where people have no money to buy the rest of the kit we produce, but their governments always have enough cash for a few more F16s. The surrogates for war in Europe, most of Asia and the US are commercial battles over segments and sub-groups, target populations, the upwardly mobile, the nouveau poor (who will consume anything as long as it’s cheap, rather like a man catching at a bloated cow in a flood), the nouveau rich and demographic newcomer groups such as gay couples, transatlantic parents, net-teens, cocooners, neo-luddites, bohemian dinks and techies, etc. |

| Share the pod and foil the wild |

I sometimes wonder whether there is not a banality of goodness, not such as might balance Hannah Arendt’s famous “banality of evil”, but rather as might actually contribute towards it by sheer blandness. If Tolstoy was right to consider all unhappy families as unique, the corollary does not necessarily stand that the ubiquitous nature of other family constructs need be confused with contentment.

Poor parenting is usually held to be as responsible for the unhappy and dysfunctional family as nominally “good” parenting is for the shallow kind of happiness that is the unfortunate lot of so many teenagers who might wish their backgrounds were a little more romantic. Wannabe Heathcliffs are nipped in the bud by the sheer niceness of the cosy pod they are raised in. The underwhelming nature of childhood experience either reduces them to a state of apathy beyond even that which is common to their age-group, or the utterly uncool ennui of so much down-home, average goodness forces them into a life of thrash-metal music, secret genital piercings and gruesome horror flicks to compensate. Small wonder that many “normal” parents discover with a jolt that their teenage progeny are from another planet, belong to another life-form altogether and exchange suicide tips on the internet. In other words, you don’t have to be deprived to end up on page two of your local paper, nor do your parents have to spend their entire lives in front of the telly ignoring you.

However, it does help if there is an over-developed culture of privacy and individual space within your home. If you are fifteen and have your own TV, your own hi-fi and your own computer in your own room, a place where you generally snack your own micro-waved meals because your family doesn’t eat together during the week ... then yes, you are one of the luxurious dysfunctional and in clear and present danger from all the dystopian influences that surround your unformed and MSG-hyped-up mind. This is not to say that you’re definitely going to jump off a bridge. But yes, the chances are significantly higher than for a child of the same age who shares a room, shares a computer, shares a TV ... and shares all his/her meals with a family that still has old-fashioned conversations from time to time: and by conversations I mean something more than a parental interrogation on your day or a list of items to tick off (homework done, shoes cleaned, bed made, room tidied), guilt to be attributed or accusations to be made between two immiscible generations.

Notice I have mentioned neither single parents, nor re-composed or unconventional family units. Because it’s the health and vibrancy of a family that is important, the amount of common experience it shares, rather than the social model it represents that is most likely to keep an adolescent on the rails and clear of the wild side. |

| “They’ve got a name for the winners in the world ... |

New theories on teen suicide abound: some say sensory saturation is just as dangerous as sensory deprivation and many children are suffering from overload to the point that they can no longer dissociate fact from fiction. This leads them to project the tragedies of fictional lives, or even lives of their own invention, onto their own. A process of over-identification or assumed identification ensues that can lead to distress and self-estrangement.

Others say that we’re all mother hens, selfishly having kids far too late in life to be anything other than over-cautious and possessive, so that our coddled and over-protected young are as emotionally deprived as those who are “genuinely” neglected (by absentee, drugged, drunk or abusive parents), because they lack the all-important adrenaline rush of risk and adventure in their lives that comes from assuming responsibility. As a result such teenagers seek out or deliberately create extreme situations, exaggerate the importance of small set-backs and make anti-heroes of themselves in the context of their social group.

Yet another theory maintains that the current generation of parents are too “friendly and complicit” with their kids. They lack sufficient distance, gravitas, self-discipline or, all too frequently, job stability and thus appear far more vulnerable in the eyes of their children than our own parents did to us. This creates teens like Adrian Mole, already unsure of their own identity and even less secure in their skin when they realize they are sharing a house with a couple of day-dreaming neophytes, who have clearly failed to successfully check-out of the Hotel California of their own formative years.

A fourth theory suggests that all recent generations of youth, at least since the nineteen-eighties, lack the real challenges of dragons to kill, since all the big causes, such as climate, the environment, equality, peace, civil and human rights, have become the institutionalized playthings of the political classes. |

| ... I want a name when I lose” |

But perhaps, at least to my mind, the most significant additional contributor to teen suicide (reinforcing any or all of those mentioned above) may well be the generalized acceptance that “it’s my life”: it’s my party, it’s my body and it’s my future ... or lack of it, which brings us back to irresponsibility, accusation and arrogance.

The post-modern definition of self purely in terms of individual rights has led to a belief that my destiny is, on the one hand, entirely of my own making (succeed with aplomb, fail gloriously, take a bow) and yet, on the other, that this same manifest destiny can be just as entirely hindered or thwarted by the lack of recognition or support that it receives on the part of my family and peers. In other words; everybody thinks of themselves, I’m the only one thinking of me. No wonder I’m a loser.

If it takes a village, as Hilary Clinton once so memorably put it, to form a mature citizen (parents, siblings, relatives, friends, neighbours, teachers, church, sports team, family doctor etc.), then it ought certainly to take at least another village to deform one, as J.B. Priestley reminded us in “An Inspector Calls” all those years ago. Unfortunately, in the age of the ‘Individualista’, this final decision is all too often taken by a corrupted teenissimo ego: all alone, without benefit of experienced council, referential structure of comparison or hope of reprieve.

If we really want to save our children’s futures and maybe even their lives, it’s time to start rewarding good parenting instead of merely punishing bad parenting by the default position of social failure. Extra child allocation money put into a trust fund in the child’s own name for every hurdle successfully negotiated (relative to that child’s estimated ability, of course) could be a big incentive to families and kids alike from their earliest age. Get all your infant check-ups and vaccinations = money in the bank, go to pre-school and behave well = money in the bank, finish primary school = money in the bank, without any unpleasant incidents = money in the bank, finish secondary school = money in the bank, learn a skill = money in the bank, get into higher education = money in the bank. Get your degree = money in the bank. But do something stupid, cruel or criminal = money out of the bank. Be anti-social or detestable, gross or hateful, unhelpful and selfish = money out of the bank. Make up for it with a year of good behaviour and social work = money back in the bank. Marry someone from outside your community, race, religion or nationality = extra money in the bank for being daring and contributing to the unity of humanity. And so the whole thing starts up all over again. |

| The return of the village green-back |

Meanwhile a whole community has been involved to decide whether this or that kid merits reward or not or how much for his/her performance, achievement and social comportment: the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, the teacher, the school director, the school social worker, the youth worker, the probation officer, the pastor or the imam or whatever, the family doctor, mum and dad and the next-door neighbours ... everyone with a stake in that child’s progress will have an influence on the level of reward granted. And at any time the family can put tax-deductible matching funds into the same account, a trust fund that our young Holden Caulfield will be able to draw on as soon as he reaches majority.

We need to invest in citizenship if we want our countries to have citizens and not merely a population. We need to invest in honesty if we want to empty our jails. We need to invest in a yearning for life if we want to overcome the seduction of death. As a society it will save us a whole lot of money and time and heartache in the end!

© Edwin Drood, September 2010

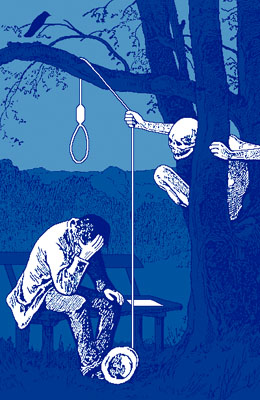

Illustration: "Ein neuer Totentanz" (A new dance of death), after a drawing by Otto Seutz, 1897. |

|

Edwin Drood's Column, the blog by The Mysterious Edwin Drood,

at My Favourite Planet Blogs.

We welcome all considerate responses to this article

and all other blogs on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|