|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Cheshire Cat Blog > 2011 |

|

|

back |

The Cheshire Cat Blog

|

|

Feb-March 2011 |

|

| |

|

Radio City Tower and the drummer boy at the King's Liverpool Regiment Memorial. |

| |

Mersey beats

Part 1: She gives me religion |

Articles and

photos by

David John

|

|

|

The Cheshire Cat walks the streets of Liverpool and finds a city proud of its past, looking to the future and moving to the beat of a different drum.

In Part 1 we take a look at faith in the city. Liverpool has two main religions: one is the worship of great gods who do battle on holy turf amid a mass of true believers, and is known as football; the other one happens in churches. Each of the religions has two main sects which divide the loyalties of citizens: Liverpool F.C. and Everton F.C.; Catholicism and Protestantism. |

|

| |

Down the mystic avenue I walk again

Remembering the days gone by

And I'm knocking with my heart

And all the girls walk by

In all their summer fashions

And the churchbells chime

On a summer Sunday afternoon

She gives me religion

She gives me religion

She gives me religion by Van Morrison, from the album Beautiful Vision |

|

| |

Football crazy - even the houses are red

|

| |

Arriving in Liverpool on a warm summer evening it was puzzling to find the streets quite deserted. The reason: football, of course. We were in the middle of the World Cup 2010, and it seemed that everyone was indoors glued to the TV. I was surprised that there were no large groups of fans around, and I didn't find any of the public view areas which have become common in European cities. Most people were watching matches at home or in pubs. A few lucky ones were enjoying the competition under South African skies.

This is the most football-crazy city I know. It's not a game here, it's a religion, and either you support Liverpool or you support Everton. The legendary rivalry between the red and the blue is fierce, but during the international competitions Liverpudlians unite under the England flag.

Terraced houses, The Dingle, Liverpool, England. Photo: © 2010 David John |

|

| |

|

"For he's football crazy,

He's football mad,

The football it has taken away

The wee bit of sense he had,

And it would take a dozen skivvies

To wash his clothes and scrub,

Since Paul became a member of

That terrible football club."

English version of a traditional Scottish song,

attributed to James Curran (around 1885).

Made popular in the 1960s by Robin Hall

and Jimmie McGregor, Rolf Harris and others. |

|

|

| |

|

Over the last two decades, the red cross of Saint George (England's patron saint), which hangs outside so many houses, has supplanted the British Union Jack: not only do Scotland and Wales have their own national teams, but now they have their own parliaments too. It seems the English think they can get on quite well without them. It shouldn't be forgotten, though, that Ryan Giggs is a Welshman, even if he does play for Manchester United.

Terraced houses, The Dingle, Liverpool, England. Photo: © David John 2010 |

|

| |

Lubricating the larynx

|

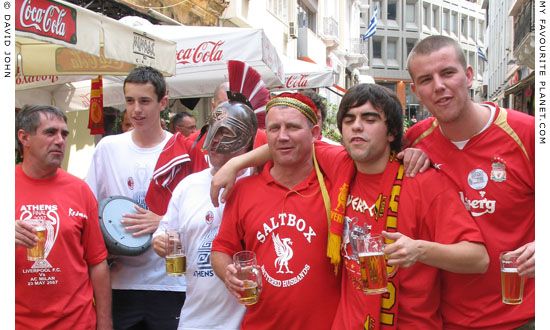

Since my last visit to Merseyside was out of season, I didn't see any Liverpool football fans in their native habitat. But just to prove how dedicated Liverpool fans are, here's a photo of a few of them in the Athens Plaka district in May 2007, warming up for the UEFA Champions League Final match against A.C. Milan. Sadly for the Reds, Milan won 2–1.

Liverpool fans in the Plaka, Athens, Greece. Photo: © David John 2007 |

|

| |

The lads from the Kop

|

The centre of Athens was flooded by a sea of red as Liverpool fans enjoyed a

pre-match day on the town. And a good time was had by all. The A.C. Milan fans, meanwhile, were hanging out in another part of the Greek capital.

Liverpool fans in Monastiraki, Athens, Greece. Photo: © David John 2007 |

|

| |

Go tell it to the Spartans

A Liverpool fan makes a strategic alliance

with a member of the Greek armed forces.

Liverpool fans in the Plaka, Athens, Greece. Photo: © David John 2007 |

| |

"I'm a celebrated footbal fan, as everybody knows;

And I've stood in every Kop and shed from here to Elland Road;

I can show a 4-3-3 can beat the old 5-3-3-1

And haven't I often proved it in the Public Bar?

I can kick like Kevin Keagan and I'm handy with me head,

And as for my allegiance, you can take it all as RED

So all I need is Paisley's call to rouse me from me bed

Where I've been scoring with the Judies in the Public Bar.

I can dribble down the alley, I can pass with either shoe

You should see me in the Nelso when I'm weaving through the queue

And no defence on earth could keep me from a pint or two

When I'm sweeping down the middle to the Public Bar.

I can settle any argument between the rival Fans,

I'm the Leslie Welsh of Wavertree, the Mersey Memo'ry Man

And I'll talk you through the goal that Roger scored against Milan

When I'm conducting the post-mortem in the Public Bar."

The Celebrated Footbal Fan by Stan Kelly,

songwriter,mathematician, columnist, 1974 |

|

| |

| |

... Meanwhile, back in Liverpool ... |

|

|

Down at the pub, the lads take in a few TV cookery tips

while waiting for the next soccer spectacular to kick-off.

|

The Bleak House pub in the Dingle is the kind of friendly local for which Liverpool has long been famous. Not merely a watering hole, it is an essential community meeting place. In the old tradition, people take care of each other. Improvised jokes flow like holy treacle.

The Bleak House pub, Toxteth, Liverpool, England. Photo: © David John 2010 |

|

| |

Sanctum sanctorum

|

A shrine to Liverpool Football Club, complete with icons and holy relics. During sacred games, the faithful gather beneath the holy light of the beamer which falls squarely on the altar screen; the modern iconostasis. Libations and burnt offerings can be ordered at the bar.

"Thank you very much for our gracious team

Thank you very much, thank you very very very much.

Thank you very much for our gracious team

Thank you very very very much!"

Thank U very much by Mike McGear (a.k.a. Mike McCartney) of The Scaffold, 1967

The Bleak House pub, Toxteth, Liverpool, England. Photo: © David John 2010 |

|

| |

Everton – the next generation

Just to prove that the Cheshire Cat is unbiased, here's a photo of an Everton fan.

|

"Over at Anfield the shirts they are red.

And the players play football as though they were dead.

While over at Goodison the shirts they are blue,

And the football they play is fantastic to view."

From the song In my Liverpool home by Pete McGovern (1928-2006)

Anfield is the spiritual home of Liverpool F.C. and Everton F.C.'s sacred turf is at Goodison.

Everton F.C. is the oldest of Merseyside's professional football clubs, having been founded in 1878. Across the Mersey in Birkenhead, not-quite-so-famous Tranmere Rovers kicked off in 1884, while Liverpool F.C. didn't get going until 1892. |

|

| |

Come on England!

An inflatable football fan as votive offering.

Toxteth, Liverpool, England. Photo: © David John 2010 |

| |

| |

Choose your pews |

|

|

Old Saint Nick's competes for space with modern towers.

|

The Anglican Church of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas, Chapel Street, known as the Old Church, the Sailors' Church and Saint Nick's, is the parish church of Liverpool. The Grade II listed building stands on the city centre's oldest church site, at what used to be the shoreline of the River Mersey, near the Pier Head.

The original small chapel of Saint Mary del Quay (or Saint Mary del Key), was founded here some time before 1267 and was in use until 1548. After its closure it was used as a warehouse, a school, a boat house and a tavern until its demolition in 1814.

By 1355 the original chapel was considered too small for the growing number of worshippers, and Liverpool's mayor and burgesses were granted a Royal Licence to purchase a piece of adjacent land from John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, for £10 to build a new chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas. The new building is thought to have been in use by 1360, and further extensions and alterations were made over the centuries.

In 1361 a plague struck Liverpool, and consent was given by Robert Stretton, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry (whose diocese at the time included Northwest England) to use the churchyard for burial. The chapel was consecrated in 1362.

Throughout its history Saint Nick's has had a close asscociation with Liverpool's maritime enterprises and the people involved in them, from poweful shipowners to ordinary sailors. In the churchyard was a statue of Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of seafarers, to which sailors prayed and made votive offerings in the hope of a safe and prosperous voyage.

Following the Reformation, both chapels ceased to be part of the Roman Catholic Church, and during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I the chapels' properties were appropriated by the Duchy of Lancaster. In 1554 Saint Mary's Chapel was sold for 20 shillings (presumably a nominal price) to the Corporation of Liverpool, who used it as the town's warehouse. With the dissolution of the monasteries in Britain, the ancient monopoly held by the Benedictine monks of Birkenhead Priory to ferry passengers across the Mersey (the Monk's Ferry) was also ended.

During the English Civil War, Liverpool was besieged and captured in turn by Parliamentary and Royalist forces (1643-4), and the chapel was used to inter prisoners of war.

Until Liverpool gained its first bishop in 1880, it had been part of the Diocese of Chester. Within the diocese, Liverpool was part of the parish of Walton, founded in 1326, the parish church being Saint Mary's Walton, which had been founded in Saxon times. In 1699 Liverpool was made a distinct parish, and unusually it had two parish churches, Saint Nicholas and the new Saint Peter's Church (built 1700-1704, demolished 1922) in nearby Church Street. It also had two rectors of equal status who preached on alternate Sundays in each church. In 1767 Liverpool was divided into 5 divisions or wards: Saint Nicholas's, Saint George's, Saint Peter's, Saint Thomas's and Saint John's. In 1916 Our Lady and St Nicholas became Liverpool's sole parish church.

The church was enlarged between 1673 and 1718, six new bells were installed in the tower in 1725, a new spire was built in 1746, and a new organ was installed in 1765. Despite all these works, by 1774 the church was in such a bad condition that it had to be rebuilt. The new church, in the Georgian Gothick style, was built under the direction of Joseph Brookes. The final design, an unhappy compromise caused by disputes between the parish and wealthy pew-owning families, has been described as "undistinguished".

|

On Sunday 11th February 1810 the spire and tower collapsed as the congegration were arriving for morning service, killing 25 people and seriously injuring another 24. The new 40 metre-high (120 feet) tower was built 1811-1815, designed by architect Thomas Harrison of Chester (1744-1829). It was topped by the distinctive 20 metre-high (60 feet) lantern spire, which at the time was visible from a great distance and became one of Liverpool's earliest landmarks. The ship weather vane is thought to date from the time of the church's 1746 spire. In 1834 the church acquired an illuminated clock dial, the wonder of the age and reported by The Liverpool Mercury to be "a capital landmark" as a navigation aid to shipping. Burials at the church ceased in 1849, and in 1891 the churchyard became a public garden as a memorial to shipowner James Harrison (1821-1891).

During the Second World War, German air raids in December 1940 and May 1941 destroyed the body of the church, although the tower remained standing. It was rebuilt 1949-1952 to a much altered design by Edward Charles Butler.

Like the Church of Saint Margaret of Antioch in Toxteth (see below), Saint Nick's describes its style of worship as being "in the catholic tradition". It became part of the High Church 1851-1852, and later, because of the opposition to Anglo-Catholicism by Benjamin Disraeli and James Ryall, the first Bishop of Liverpool (see below), Liverpool-born William Gladstone bought the patronage of the church's funding from the Corporation. Gladstone is still named as the church's patron, and the patronage remains in the Gladstone family.

Although little of Saint Nick's early structure has survived, the church and the site itself, now surrounded by modern buildings, still serves as a reminder of Liverpool's medieval beginnings as a small fishing village before it grew to become Britain's second largest port.

Saint Nick's is open Monday-Friday 9am - 5pm,

and Saturday and Sunday mornings.

Saint Nick's website: www.livpc.co.uk |

|

|

|

"And if you want a cathedral, we've got one to spare." *

|

Not only does Liverpool have two rival football teams, it also has a Protestant and a Roman Catholic cathedral. The Anglican (Protestant Church of England) Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool, more commonly known as Liverpool Cathedral, is the older and larger of the two. Designed by Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960, actually a Roman Catholic), building began on the Gothic Revival style cathedral in 1904. Construction was halted by World War II, and was only completed in 1978.

This enormous monumental edifice, built of sandstone from nearby Woolton, towers above Saint James' Mount in Liverpool's city centre. The 100.8 metre (331 feet) high Vestey Tower, completed 1942, makes the cathedral the 90th tallest church in the world. With a length of 188.7 metres (619 feet) and a total area of 9,687.4 square metres (104,275 square feet) it is the longest cathedral and second longest church building in the world, the 6th largest church building in the world by area, and 12th largest by volume. It is also the largest cathedral in the United Kingdom and 5th largest in the world.

As they say in Liverpool: "Izzdarrafact?" |

| |

| * In my Liverpool home |

From the song In my Liverpool home by Pete McGovern (1928-2006). I make no apologies for mentioning this song more than once on this blog as it describes life in and the spirit of the city better than any other song or poem I know - even Stan Kelly's Liverpool Lullaby (or The Mucky Kid) - and does it in such a poignant, funny and uplifting way. There are many versions of the song, and McGovern and others added innumerable verses to it.

The key verse/chorus goes like this:

"In my Liverpool home,

In my Liverpool home,

We speak with an accent exceedingly rare,

Meet under a statue exceedingly bare,

And if you want a cathedral, we've got one to spare,

In my Liverpool home."

The "accent exceedingly rare" is the Liverpool dialect Scouse, spoken by Liverpudlians or Scousers, whose most famous dish is the stew known as lob scouse. This local delicacy (strangely not mentioned in the song) is said to have been introduced to Liverpool by sailors who learnt about it from Scandinavian seamen (Norwegian Lapskaus). But when I was a kid I was told it got its name from the fact that you could "lob" (throw) anything into the pot, and the stew was made from whatever food that was left over when the "ackers" (money) had run out, just before the workers' weekly pay day.

The "statue exceedingly bare" is Liverpool Resurgent, the "naughty, naked, nude" statue by Jacob Epstein (see photo, right), nicknamed "Dickie Lewis", which adorns the main entrance to Lewis's Department Store (now closed down) in Lime Street, once a popular meeting place for friends and couples. During Lewis's heyday, Liverpudlians as well as people from Lancashire, Cheshire and Wales who came to Liverpool to do big-item shopping, will have had their first ever encounter with many exotic objects here, including elevators and escalators; now commonplace, they were then luxurious marvels. |

|

|

Hi there, and welcome to Liverpool.

Sandstone relief of a laid-back looking "The Welcoming Christ"

on the west side of Liverpool Cathedral.

|

| |

The original sculptures of Liverpool Cathedral, including "The Welcoming Christ",

were made by Liverpool-born sculptor Edward Carter Preston (1885-1965).

In 1931 he began 30 years of labour to produce 50 sculptures, 10 memorials

and several reliefs and inscriptions.

"In Delaware when I was younger

They thought Saint Andrew had sufficed

But in the Spring I had great hunger

I was Buddha. I was Christ.

You wicked wise men where you wonder

You Pharisees one day will pay

See my lightning, hear my thunder

I am truth, I know the way."

School Days by Loudon Wainwright III,

from the album Loudon Wainwright III |

|

| |

Sandstone statue of a spaced-out youth carrying loaves and fishes,

a reference to the Biblical story of the sermon on the mount.

West side of Liverpool Anglican Cathedral |

| |

"Risen Christ" statue by Elisabeth Frink (1930-1993),

on the north side of Liverpool Cathedral.

|

This colossal statue was Frink's final major commission, and she worked on it through serious illness. She was able to watch the unveiling on television in April 1993 just a week before her death.

There is something strangely unsettling about this figure: humble, vulnerable, exposed - more naked than nude - especially as placed on such a relatively tiny pedestal high on the exterior of Gilbert Scott's massive, perpendicular gothic architecture. Viewed from ground level, the foreshortened limbs appear disproportionately short, the head too large, making him seem awkward and alien. The green patina of the bronze contrasts strongly with the red sandstone, making the figure seem even more alien.

The subject of the risen Christ, a central theme in Christian philosophy and art, is that of resurrection after and victory over death. From a distance, this figure, standing stiffly with outstretched arms, does not seem particularly triumphant. However, a closer look at the head held high, the strong facial features and the clear, resolute gaze reveal a great strength, tranquility and perhaps a quiet defiance. I also think that there is more than a passing resemblance to Frink herself. |

|

Head of Frink's

Risen Christ |

|

| |

The Oratory, former chapel of Saint James' Cemetery (1829),

Duke Street (next to Liverpool Cathedral). Designed by John Foster Junior.

|

Son of the Liverpool architect and dock engineer John Foster Senior (1758-1827), John Foster Junior (circa 1787-1846) travelled through Italy, Turkey and Greece 1809-1816, hung out with Lord Byron in Constantinople (Istanbul), shared a house in Athens with Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863, also to become a noted Greek Revivalist architect), and was involved in archaeological excavations with Cockerell, Carl Haller von Hallerstein, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, Jakob Linckh and others at Aegina and Bassae in Greece. [1]

His Mediterranean travels left a great impression on him (he even married a woman from Smyrna [2]) and influenced his architectural style which has been described as "severe" and "pure" classicism.

On his return to England he joined his father's building firm in Liverpool, and in 1824 succeeded him as Senior Surveyor to the Corporation of Liverpool. The family firm built seven churches, including Saint Luke's and Saint Mary's Church of the School for the Indigent Blind (see below), and several grand buildings in the city. Many, such as his Customs House, were destroyed by German bombing during World War II or subsequently demolished.

He designed Saint James' Cemetery (1827-1829, now Saint James' Gardens public park) on 44,000 square metres of land at the foot of St James' Mount. As well as the Oratory (1829), which served as the cemetery's funerary chapel until 1936, he also built a house for the minister (later demolished to make way for the cathedral), a monumental entrance arch, a porter’s lodge and the Huskisson Monument (1834), a small circular temple as the grave of William Huskisson (1770-1830), the Liverpool MP who was run over by Stepenson's Rocket at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on 15 September 1830, making him rail travel's first casualty. |

Triglyphs, metopes,

palmettes and lion

heads on the Oratory |

|

The form of the Oratory is that of a Doric temple in amphiprostyle, i.e. with porticos supported by six columns (hexastyle) at each end. Unlike most of the classical temples Foster would have seen on his travels, his temple did not have columns all round and was therefore probably modelled on a simpler temple, such as that of Athena Nike on the Athens Acropolis. The Oratory, however, is larger and its porches have six Doric columns rather than four Ionic. Also unlike most ancient Greek or Roman temples, it has no decorative friezes or sculpture (although it does have a row of 19 palmettes and 38 gargoyle-like lion's heads along the top of each side), adding to its "severity".

Inside are several 19th century statues and funeral monuments. Today, the Oratory, which is now part of National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, hosts occasional art exhibitions. |

Since 2005, a sculpture by Tracey Emin has stood in front of the building. See photo below.

The Oratory is open by appointment

with the Walker Art Gallery.

Tel: 0151 478 4102

www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/walker/

1. The archaeological exploits of Foster, Cockerell and the others, which have caused a controversy comparable with that surrounding the "Elgin Marbles", will be examined on My Favourite Planet at a later date.

See also:

The Cheshire Cat Blog, July 2011

and

Edwin Drood's Column, 21 June 2011

2. In February 1812 Foster fell in love with Mary Maraccini, daughter of the Russian consul in Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey), while travelling with Cockerell. So smitten was he that he abandoned his travel plans and Cockerell had to continue his explorations of western Anatolia alone. |

|

|

John Foster Jr. |

| |

Aphaea Temple,

Aegina, Greece |

| |

Hephaesteion,

Athens, Greece |

| |

Athena Nike Temple,

Acropolis, Athens |

| |

Plan of the

Athena Nike Temple |

| |

Lion-head spout of the Athena Nike Temple |

| |

| |

The Oratory at night, with an Egyptian-style obelisk in the garden. |

| |

"Roman Standard" sculpture by Tracey Emin (2005), outside the Oratory

|

| |

Commissioned by the BBC for the art05 festival, the 10 cm (4 inch) bronze sparrow stands on a 4 metre-high (13 foot) pole in front of the Oratory, positioned on the central axis of the building. You may find the title "Roman Standard" misleading if you expect the kind of great, vicious imperial eagle and military banner carried by macho legionaries as they slaughtered their way to empire. Tracey's sparrow has a subtle, delicate effect on its surroundings and intrigues passers-by. In an interview with BBC Radio Merseyside, Tracy said:

"Since 1992 I’ve been making a series of drawings, etchings and prints of birds. I’ve always had the idea that birds are the angels of this earth and that they represent freedom. My Roman Standard represents strength but also femininity. Most public sculptures are a symbol of power which I find oppressive and dark. I wanted something that had a magic and an alchemy, something which would appear and disappear, and not dominate."

Indeed, since the Oratory normally remains closed behind its cast iron railings and gate, many people don't even notice it at all. And persons unknown seem to have taken her words about appearing and disappearing quite literally. Since 2008 (when Liverpool was European Capital of Culture) the bird has been stolen at least twice and each time mysteriously returned unscathed. Was this some kind of gorilla art action, a publicity stunt or art thieves with a conscience? Who knows. Police do not suspect fowl play.

Tracey was also right in saying that "most public sculptures are a symbol of power", as well as being about death - dying and killing - as many of the photos on this page testify. So it's refreshing to see a sculpture about the delicate magic of life.

I have to admit that I hadn't heard of this work before coming across it on my latest visit to the city (we don't get The Liverpool Echo in Berlin). I didn't know who had made it or why, but was instantly charmed by it, and it seemed to naturally belong right there.

Those whacky Scousers (Liverpudlians) dubbed the sculpture "bird on a stick" (a kind of back-handed Scouse compliment?), and the media love to describe Tracey and her work as "controversial" (bad girl of art, femme tragique, shock, horror, etc., blah, blah). A lot of fuss was made about the fact that the work cost 60,000 pounds. Admittedly, that's a lot of toffees, but what is art actually worth then? Media proprietors make far more than that for publishing a load of tosh every day.

Anyway, a lot of people were so chuffed with her work that Liverpool Cathedral commissioned another work from her. In 2008 her neon sculpture "For You" was installed above the west doors in the cathedral. 6 metre-high (20 feet) pink neon letters in handwriting style proclaim: "I felt you and then I knew you loved me."

Tracey Emin's website: www.tracey-emin.co.uk |

|

| |

Where there's hope ...

The street which runs between Liverpool's Anglican and Catholic cathedrals is by happy coincidence called Hope, named after the merchant William Hope who built the first house there. It is home to several local landmarks, including the Everyman Theatre, the former School for the Blind and the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall. The love of harmony, indeed.

Homer has not fared so well. Blind, abandoned and unadopted, he slumbers in a corner of the Dingle, "down by the docks".

Maybe Matt Groening can save him?

"I was born in Liverpool, down by the docks,

Me religion was Catholic, occupation hard-knocks"

From the song In my Liverpool home

by Pete McGovern (1928-2006) |

|

|

|

The open air altar on the north side of Liverpool's Roman Catholic cathedral

|

To avoid confusion, Liverpool's Catholic cathedral is offically known as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King Liverpool. Quite a mouthful; no wonder Scousers call it "Paddy's Wigwam", "The Mersey Funnel" and "The Pope's Launching Pad".

A high percentage of Liverpool's population is Roman Catholic, which is unusual for England, where Catholicism was supressed for generations. As Liverpool grew into an important port during the industrial revolution, large numbers of Catholics moved here from Ireland to work on ships and in the docks and factories. The influx of Irish people also increased dramatically as a result of the potato famine in 1847. The 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act and subsequent legislation allowed the Catholic Church in England and Wales to reorganize, re-establish bishops and dioceses (of which there are currently 22) and eventually build cathedrals. From the 1850s several plans were laid to build a Catholic cathedral in Liverpool, but each failed due to disputes over proposed designs, particularly the ernormous costs involved.

Designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd (1908-1984), the Metropolitan Cathedral was completed in 1967, less than five years after construction began. At the time it was a very new and exciting piece of shiny space-age design, especially placed among the dark masses of Liverpool's 19th and early 20th century Neo-Gothic architecture. Today it is still impressive, and the use of light and space in the interior are spectacular.

The conical structure, supported by 16 curved concrete trusses attached to flying buttresses, is topped by a 2,000 ton lantern tower in the form of a truncated cone and a crown with 16 pinnacles. The cathedral's circular plan has a diameter of 59 metres (195 feet). Around its circumference are 13 chapels. Within this circle of chapels is the circular main area, the Sanctuary, with seating arranged in concentric sections around the central altar. It can be no coincidence that at the time of the nave's design, theatre-in-the-round (as opposed to the traditional proscenium arch arrangement) was popular in the world of profane drama.

Compared to the Anglican Cathedral (see above) its dimensions are quite modest. Construction had begun in 1933 for an even more enormous cathedral on the 36,000 square metre (9 acres) site, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944), which would have been the world's second largest church, with a dome to dwarf that of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. Perhaps it is fortunate that the gigantomanic project was halted by the Second World War. An impression of the scale of Lutyens' plan can be gained from directly outside the present cathedral: the platform on which it stands is actually formed by the foundations and crypt of the unfinished colossus, less than half whose area is occupied by the modern building. |

|

| |

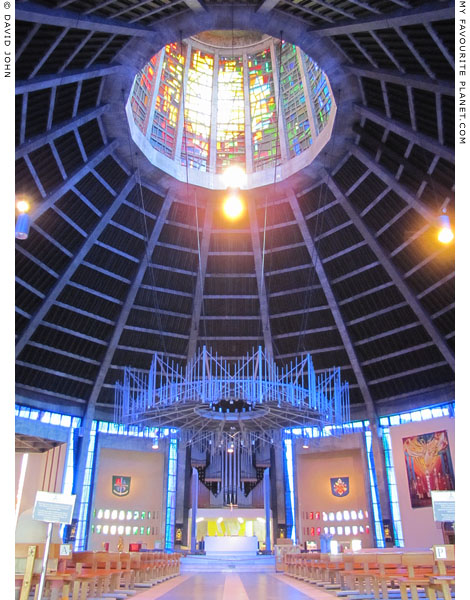

The interior of the Roman Catholic cathedral

|

This photo does not do justice to the cathedral's dramatic interior. On a sunny day the light floods down through the tower's abstract stained glass panels, designed by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens, and made up of large, irregularly-shaped pieces of glass in red, yellow and blue - three colours to represent the Christian Trinity.

Unfortunately, when you look up to admire this wonder you are likely to be blinded by the powerful spotlights intended to compensate for nature's occasional luminosity deficits. |

|

| |

The dark interior of the roof further highlights the brilliant light

filtered through the colours of the stained glass. The roof's

exposed structural elements remind one of a spider's web. |

| |

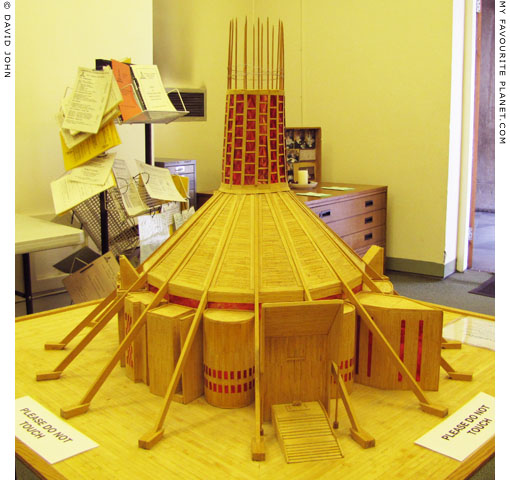

Matchstick model of the Metropolitan Cathedral

by Arthur Cunliffe. Completed 1999.

A man of enormous patience, great grandfather Arthur Cunliffe has

built several such scale models of buildings, including the Lourdes

Basilica and the Eiffel Tower, with only photographs as reference.

Many of his models have been exhibited to raise money for charity. |

|

"Abraham, our father in faith", sculpture by Sean Rice (1931-1997)

in the west apse of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral

|

Oh God said to Abraham, "Kill me a son"

Abe says, "Man, you must be puttin’ me on"

God say, "No." Abe say, "What?"

God say, "You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’ you better run"

Well Abe says, "Where do you want this killin’ done?"

God says, "Out on Highway 61"

Highway 61 Revisited by Bob Dylan

from the album Highway 61 Revisited, 1965 |

|

| |

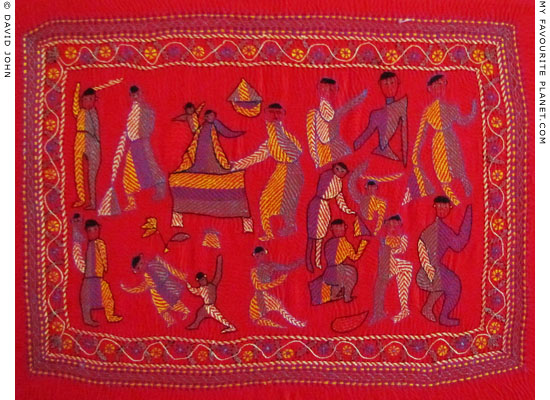

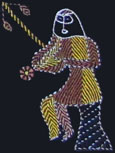

Exhibition of traditional Kantha embroidery from Bangladesh

in the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Hand embroidered

by the mothers from Sreepur and women from rural villages. |

| |

Traditional Kantha embroidery from Bangladesh

in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. |

| |

| |

Double take |

|

|

Saint Bride's Anglican Church, 1830, Percy Street, in Liverpool's Georgian Quarter.

|

Another of Liverpool's Greek Revivalist churches, Saint Bride's porch is supported by six Ionic columns. The white temple, set back from the road, surrounded by trees and bathed in the warm light of a summer afternoon, is reminiscent of the mansions of America's deep south. Unfortunately, Saint Bride's does not serve mint julips.

This is the Church of England's parish church for Liverpool's University and Canning areas, dedicated to Saint Bride (circa 451-525, also known as Saint Bridgit of Kildare), a contemporary of Saint Patrick, and along with him and Columba one of Ireland's patron saints. She is said to have been the daughter of an Irish prince and a druidic slave, and to have written the following beery-pious poem:

"I long for a great lake of ale

I long for the meats of belief and pure piety

I long for flails of penance at my house

I long for them to have barrels full of peace

I long to give away jars full of love

I long for them to have cellars full or mercy

I long for cheerfulness to be in their drinking

I long for Jesus too to be there among them."

I have been unable to find much information about Saint Bride's architect Samuel Rowland (died 1844 ?), except that he also designed the (former) Royal Bank (1837-38) and Queen Insurance Building (1837-1839), both in Dale Street, Liverpool. This is puzzling as an architect of such competence, entrusted with such prestige projects must have had some pedigree and left behind other traces of his work and life.

If you know anything about Mr Rowland, I would love to hear from you.

See contact.

Saint Bride's website: www.stbrides.com |

|

| |

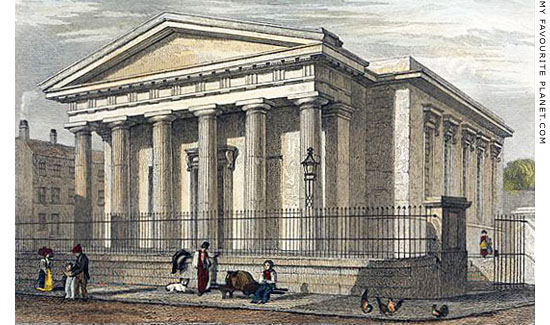

Saint Mary's Church of the School for the Indigent Blind,

built 1819, demolished 1930.

Hand-coloured engraving by Lowry after J. Harwood,

from Lancashire Illustrated, 1831.

|

| |

Another version of this book illustration of Saint Mary's Church is incorrectly captioned as Saint Bride's. The mix-up is perhaps understandable as the two Greek Revivalist temples are superficially similar, although this was a grander building than Saint Bride's and had a Doric rather than an Ionic portico.

Because of the similarity to Saint Bride's, and since it is one of the great buildings of Liverpool which has been swept away in the name of redevelopment, I include here a brief history of the church and the remarkable institution it served.

Liverpool's School for the Indigent Blind (indigent = poor, needy), founded in 1791 at the instigation of the blind poet and campaigner Edward Rushton (1756-1814) [1], was the first - and for many years the only - school for the blind of all ages in the world. At first the school rented two small houses on Commutation Row, at the north end of Lime Street. In 1800 it moved to a purpose-built school, designed by John Foster Junior, on the corner of London Road and Duncan Street East (in 1843 renamed Hotham Street [2]), where it was able to take resident pupils. Henry Smithers wrote: "Neatness, simplicity and usefulness are the characteristics of this building, rather than architectural beauty." [3].

| |

School for the Blind.

From The Stranger in Liverpool, 1812. |

By 1818 building had begun on the opposite side of Duncan Street East of the school's own church, Saint Mary's, also designed by John Foster Junior, which was completed in 1819 (11 years before Rowland's Saint Bride's). Contemporary writers described it as "one of the purest copies of the early Grecian architecture to be met with in England", and the portico as "an exact copy of the portico of the temple of Jupiter Panhellenius, in the island of Egina". [3] (The ruined temple on Aegina, which Foster had helped excavate, has since been identified as the temple of the goddess Aphaea.) The church even had an underground passage connecting it to the school.

Skills such as spinning, weaving and basket-making were taught at the school, with the aim of helping pupils to become self-sufficient rather than having to depend on charity. Music and singing were also important parts of the curriculum, and services at the church were fashionable among Liverpool's wealthier citizens for the performances. Such "strangers" to the church (visiting worshippers who did not hold a regular pew or seat) were expected to "contribute a trifle in silver".

The "strangers" would have presumably also been impressed by the large paintings "Christ Healing the Blind" by James Hilton and "Christ Blessing the Little Children" by Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786-1846), which were hung on either side of the altar. Both paintings are now in the Walker Art Gallery, although Hilton's picture is not currently on display.

Later, the school's Duncan Street East site was required for the enlargement of the railway to the new Lime Street Station (the neo-classical entrance to the original station had been designed by Foster in 1836 for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway), and in 1850-1851 the school moved into a new building, designed by A. H. Holme, on the corner of Hardman Street and Hope Street. The church was also moved piece by piece to the new location.

The above engraving was published in 1831, based on a drawing or watercolour made some years earlier, and is therefore a view of the church on its original Duncan Street East site. Given that such romantic artists' impressions were not always exact portrayals (i.e. they tended to "prettify" their subjects), this is a valuable historical representation of the street as it was then. A cockerel and three hens stand calmly on the street corner (right), and a young man sits on what looks like a bench or stretcher, next to his large, mysterious bundle. He may be a porter taking a rest on his barrow.

The church was closed in 1927 and demolished in 1930 (why?). The school building became part of the headquarters of the Merseyside Police, and later the Trades Union Centre. A drum from one of the church's columns is now in Saint James' Gardens, in front of the Huskisson Monument (see above), near John Foster's own grave.

1. Edward Rushton (1756-1814) was a seaman, publican, poet, journalist and campaigner against slavery and pressgangs and for human rights. For many years he was blind, a condition he did not accept as a so-called handicap. Read Mike Royden's excellent illustrated article about Edward Rushton's life and work at Mike Royden's Local History Pages.

2. Hotham Street, named after Admiral William Hotham, the 1st Baron Hotham. Today the narrow street behind Lime Street Station is the location of the Academy concert venue.

3. Liverpool, its commerce, statistics, and institutions: with a history of the cotton trade by Henry Smithers, Liverpool 1825. |

|

|

Saint Nicholas Greek Orthodox church, 1870,

Berkley Street, Toxteth, Liverpool.

|

Saint Nicholas was designed by William and James Hay [1] in the Neo-Byzantine style, based on the design of Hagios Theodoros church in Constantinople (now Molla Gürani Camii, also known as Vefa Kilise Mosque, Istanbul), which it resembles only slightly (see photo, right). It was built 1865-1870 under the supervision of local architect Henry Sumners (1825-1895), son of a Bold Street bootmaker. The second oldest purpose-built Greek Orthodox church in Britain [2], it is a Grade II Listed building.

As Liverpool's prosperity and population increased during the 19th century, members of various ethnic and religious communities, including the Welsh, Scottish, Greek and Jewish, settled here and built their own places of worship. A religious revival in Britain also led to the building of representative churches and chapels by adherents of various Protestant denominations, such as the Calvinists, Wesleyans, Presbyterians and Unitarians.

With a liitle help from Britain, Greece had recently won its War of Independence with Ottoman Turkey (1821-1830), and was keen to increase its share of international trade. Greek ship owners, merchants and sailors visited Liverpool and some of them settled here. Many of the Greek settlers were also refugees from the bitter Greek-Turkish conflicts of the 19th and early 20th century, and were followed by Greek Cypriots who fled Cyprus when Turkish armed forces occupied the north of the island in 1974.

Incidentally, there used to be a Greek-owned chippy in the Kensington district of Liverpool which made the best fish and chips I have ever tasted. I wonder if it is still there.

There were already two other churches dedicated to Saint Nicholas in Liverpool: the Roman Catholic Church of Saint Nicholas which stood on Copperas Hill from 1813 until its demolition in 1973, and which was the Catholic Pro-Cathedral 1850-1967, before the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral was built. The Anglican Church of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas (see above) in Chapel Street on the River Mersey is the city's oldest church site, founded around 1257. The Greek congregation presumably chose to name their church after Saint Nicholas of Myra (Agios Nikolaos) as he is the patron saint of seafarers, and churches dedicated to him can be found at ports and harbours all over Greece (see, for example, The waterfront Church of Agios Nikolaos in Olympiada, Halkidiki, Greece).

|

|

Tel: 0151 709 9543 Liverpool Greek Society: liverpoolgreeksociety.co.uk

1. "The Hays of Liverpool", a family architectural firm of three Scottish brothers, born in Coldstream, Berwickshire, and based in Liverpool from around 1847. Responsible for many buildings in Scotland and northern England. By the time of the building of Saint Nicholas, the eldest brother John Hay (1811-1861) had died, and various projects were continued by William Hardie Hay (1813-1901) and James Murdoch Hay (1823-1915, president of the Liverpool Architectural and Archaeological Society 1854-1856).

See: scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=200314

2. Saint Nicholas was at least the fourth purpose-built Greek Orthodox church in Britain. In 1677 Archbishop Joseph Georgerinis of Samos gained permission to build the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (Panagia), in Soho Fields, London (now Greek Street, Soho), on a site donated by Henry Compton, the Anglican Bishop of London. The Bishop appears to have later changed his mind. A strong anti-Catholic, he objected to the Greek rites and use of icons. A notorious court case involving the alleged theft of the church's funds must have also damaged its reputation, and in 1684 the church was confiscated and granted to the Huguenots. It subsequently became Saint Mary's Anglican church, demolished in 1932. Eventually, the new Church of Our Saviour, designed by Greek architect Lysandros Kaftantzoglou (1812-1885), was built in 1849 at 82 London Wall, in the City of London (since demolished).

See:

stsophia.org.uk

thyateira.org.uk

nostos.com

orthodoxwiki.org

The Manchester Greek community was by this time already well established and had worshipped at several addresses in the city. By 1848 they were in a position to build the large neo-classical Church of the Annunciation of the Mother of God in Salford. It was completed in 1861 and is still in use, making it the oldest extant Greek Orthodox church in England, Saint Nicholas in Liverpool being the second oldest.

See: www.greekchurchmanchester.org |

|

| |

The double-headed eagle, emblem of the Byzantine Empire and the Greek

Orthodox church, above the main entrance to Saint Nicholas. Usually the

eagle is shown with an orb in its left claw and a sword or cross in the right.

It is not clear whether it was the case with this bird, but the claws and

right wing appear to have been damaged and repaired at some point. |

|

The Anglican Church of Saint Margaret of Antioch,

Princes Road, Toxteth, Liverpool

|

Town planner 1: "How can we improve the look of Princes Road?"

Town planner 2: "Oh, I know, let's put a dirty great big lampost right outside this church. That'll cheer us all up."

|

Saint Margaret's, built 1868-1869, was designed by London architect George Edmund Street (1824-1881, former assistant to George Gilbert Scott), and financed by stockbroker Robert Horsfall (1807-1881), whose family built a number of churches in the Liverpool area. The church also received anonymous financial support from William Imrie (1836-1906), owner of the White Star Line, known as "the prince of shipowners".

Saint Margaret's describes its style of worship as being "in the catholic tradition", with a small c. At the time of its building the church was controversial, as both its patron Robert Horsfall and architect G. E. Street were active members of the Anglican "High Church" or Anglo-Catholic faction (which grew out of the Oxford Movement, also known as Tractarianism, Newmanism and Puseyism), considered by many, including Queen Victoria, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Conservative politician Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), to be too close in its beliefs and form of worship to Roman Catholicism. A great deal of public antagonism was stirred up against "Popery" and "Ritualism". A newspaper at the time even reported that High Church vicars "practiced celibacy in the open streets" (quoted in a speech by the Archbishop of Canterbury, 20 Jan. 2010).

The dispute between "High Church" and "Low Church" - known as the Ritualistic controversy - became a hot political issue, especially as the Liberal prime minister William Gladstone (1809-1898, Liverpool born), Disraeli's chief opponent in Parliament, was a High Church man who complained that religious practices were being used as "a parliamentary football". |

Benjamin Disraeli |

| |

William Gladstone |

|

In 1868 Disraeli made what The New York Times called "a fierce assault on Popery and Ritualism in Parliament ... and attempted to show that both of them were enemies of English liberty and the English Crown." This "was universally ridiculed as a stale trick of a hard-up politician." ("Disraeli as a Theologian", The New York Times, April 27 1868) However, there were many in Britain who shared his fears, and as the Bishop of Chester consecrated Saint Margaret's church on 20th July 1869, a protest by opponents of the High Church escalated into a riot, one of several Ritualism Riots in England during 1860s. (See Douglas Horsfall obituary, The Church Times, 18th January 1935)

In 1874 a Private Member's Bill introduced to Parliament by Archbishop of Canterbury Archibald Campbell Tait, backed by Disraeli (then prime minister for the second time), was passed with "a blustering majority" into law as the Public Worship Regulation Act, the object of which, according to Disraeli, was "to put down ritualism" and "the mass in masquerade". He also stated that "the necessity of putting down a small but pernicious sect is urgent". As a consequence several High Church clergymen were prosecuted, five of whom were imprisoned, including the vicar of Saint Margaret's, James Bell Cox (1837-1921), who spent 17 days in Walton Prison in 1887.

"The Queen was in the counting-house

Counting out her money

The Bishop in the garden

Talking to his honey

The Church was in the suburbs

Teaching of the truth

Pop came a State Judge

And pulled out A Tooth"

Contemporary satirical verse, an imitation of Sing a song of sixpence. "A Tooth" is a reference to Arthur Tooth, Vicar of St James's, Hatcham, who was imprisoned under the the Public Worship Regulation Act in 1877.

Quoted in W.H.B. Proby, Annals of the "low-church" party in England, down to the death of Archbishop Tait Vol. 2. J. T. Hayes, London 1888.

In 1906 a royal commission finally recognized the legitimacy of pluralism in worship, putting an end to the prosecutions, although the Public Worship Regulation Act was not repealed until 1965.

The Old Church of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas (see above), near the Pier Head, also became an Anglo-Catholic church in 1851-1852, and Gladstone later bought the patronage.

Saint Margaret's fell into a state of disrepair in the late 20th century, but was reopened in 2004 after a 1 million pound renovation, which included restoration of the frescos. A Grade II listed building (with ungraded streetlamp), it is often overlooked by visitors to the area because it is not as grand as its neighbour, Princes Road Synagogue (see below).

Further information about St Margaret's at:

achurchnearyou.com/toxteth-st-margaret |

|

|

Statue of Saint Margaret of Antioch with a dragon at her feet.

St Margaret's Church, Princes Road, Toxteth, Liverpool.

|

Legend has it that Saint Margaret of Antioch (also known as Margaret the Virgin, or Agia Marina in the Eastern Orthodox church) was the daughter of a pagan priest in Antioch during the late 3rd century. Following her conversion to Christianity she was tortured by the Roman authorities and finally martyred in 304 AD.

Her main claim to fame is that she was swallowed by a dragon, but due to the protective power of the crucifix she was holding, she sprang out of the monster's stomach. In art she is often portrayed standing over or emerging from the dragon, a symbol of evil.

The fabulous tales of her encounter with the dragon and her miraculous escapes from death at the hands of her persecutors made her popular in England, where over 250 churches have been dedicated to her, including the parish church of the Houses of Parliament, London. |

|

|

Princes Road Orthodox Synagogue (1874), Toxteth, Liverpool.

|

The Liverpool Old Hebrew Congregation is the oldest Jewish community in the city, dating to the mid 18th century. The Princes Road Orthodox synagogue, built 1872-1874, is one of six extant synagogues in Liverpool, five of which are still active: three Orthodox, a Lubavitch Chabad House and a Reform synagogue.

The present synagogue replaced a smaller one in Seel Street, built 1807, the congegration's fourth synagogue but the first to be purpose-built. It was designed by Thomas Harrison of Chester (1744-1829, who also rebuilt the tower of the Church of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas, see above) as a neo-classical building "of the Ionic order".

A Grade I listed building, the Princes Road Synagogue was designed by Scottish brothers William James Audsley (1833-1907) and George Ashdown Audsley (1838-1925, a follower of John Ruskin and designer of the Wanamaker Organ in Philadelphia, 1904), and built by Messrs Jones & Sons of Liverpool, with red sandstone, brick, polished red granite dressings and a slate roof. The architectural style, a mix of Gothic and Moorish, is known as Moorish Revival. Its central facade has a stepped gable with a rose window and flanked by octagonal turrets, with lower wings to each side. There are low towers at each of the buildings four corners. The turrets and towers were originally surmounted by 6 metre-high (20 ft) domed finials in the form of minarets which were removed in 1960 due to structural problems. The congregation is now hoping to replace them, as soon as it can find out where they were stored.

The interior is richly decorated with wood, marble and gold. All the windows have stained glass with floral designs made by R. B. Edmundson & Son of Manchester. The Audsleys themselves claimed it to be "an eclectic mixture of the best of Eastern and Western schools of art", and George Audsley particularly was known for being uncompromising in the quality of materials and workmanship in their buildings.

The building costs of £14,975 8s 11d were financed with donations by the congregation and patrons, including David Lewis (founder of Lewis's department store), Louis Cohen (later director of Lewis's and Lord Mayor of Liverpool), Samuel Montagu (banker, Liberal politician, 1st Lord Swaythling and member of the family who owned the well-known jewellers' H. Samuel) and George Behrend (merchant and ship owner).

It is the only synagogue in England with a mixed-sex choir. Its repertoire is still mainly based on the works of the synagogue's first choirmaster, Abraham Saqui (1824-1893), a renowned liturgical composer whose music is used in synagogues all over the world. His collection of liturgical music (chazzanut), Songs of Israel, was published in 1878.

See the article by Jonathan Greenstein at chazzanut.com/articles/saqui-1.html

Opening times (by appointment only):

Monday-Thursday 9:30-15:30, Friday-Sunday closed

The synagogue holds regular services, concerts and events.

Tel: 0151 709 3431 www.princesroad.org

Many prominent members of the synagogue's congregation, including Abraham Saqui and members of the Samuel and Lewis families, were buried in Deane Road Cemetery, Kensington, Liverpool 7. The city's oldest surviving Jewish cemetery, it was in use 1837-1929. After falling into disrepair, it is currently being restored. (See deaneroadcemetery.com)

See also the Merseyside Jewish Community website: www.liverpooljewish.com |

|

| |

The Star of David, gilded and set in a rosette (the red rose of Lancashire?)

above the main entrance to the Princes Road Synagogue, Toxteth, Liverpool.

The petals appear to be formed by palm branches.

|

"Now I've heard there was a secret chord

That David played, and it pleased the Lord

But you don't really care for music, do you?

It goes like this

The fourth, the fifth

The minor fall, the major lift

The baffled king composing Hallelujah"

Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen, from his album Various Positions, 1984. |

|

|

Saint Luke's Church (built 1811-1831) and Gardens, Bold Street, Liverpool.

|

This Perpendicular Gothic church was originally designed by John Foster Senior (1758-1827) and building began in 1811. Following many delays and alterations to the design, John Foster Junior (see above) completed Saint Luke's after his father's death. The exterior was finished by January 1828, and its bells were rung for the first time on Saint George's Day 1829. The church was finally consecrated on 12 January 1831. Like many other churches in the city, it was commissioned by the Corporation of Liverpool, for which both Fosters held the office of Senior Surveyor.

With its extra-tall 40 metre high (133 feet) tower (compare it to a more usually proportioned English gothic church tower at Saint Mary's, Ege Hill below) and imposing hillside position at the junction of Leece Street, Berry Street, Bold Street and Renshaw Street, the church was to become an important focus for local religious and community life over the next 110 years.

Saint Luke's was struck by a German incendiary bomb during an air raid on 5th May 1941 and engulfed in an enormous fire which reduced it to a roofless shell. After World War II it was decided to let it stand as a monument to those who died during the Blitz, which wrought enormous destruction in the city.

Today the church and gardens are used for concerts, theatre, films and other cultural events.

Saint Luke's website: www.stlukeliverpool.co.uk |

|

| |

|

|

|

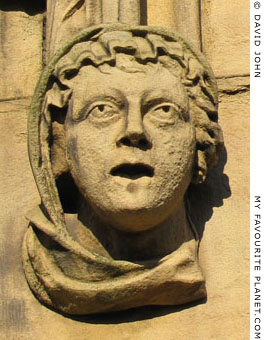

Caption Competition No. 0151

Kneestones (often referred to as corbels) in the form of human heads

decorate the arches of Saint Luke's doors and windows. The man looks

quite modern and realistic, someone you might meet on Bold Street today.

The woman's head is more a stylized, medieval type. |

|

|

Saint Mary's Parish Church (built 1813), Irvine Street, Edge Hill, Liverpool.

|

Edge Hill is just outside the centre of Liverpool, on a high sandstone outcrop with some good views over the city. At the end of the 18th century it was still mostly fields. However, as the population increased (from 25,000 in 1760 to 77,000 in 1801), people started moving out of town and new suburbs were created.

There is not much information available about Saint Mary's Church (apparently to be found in The History of Edge Hill by G. Hand, 1915). What is known is that in 1812 Mr. Edward Mason (see below) purchased a plot of land to build a church from a certain Bamber Gascoyne Esq. (not the host of the TV show University Challenge). The foundation stone was laid on 14th January 1812, the church was opened 14th March 1813 and consecrated by the Bishop of Chester on 25th September 1813 (at the time Liverpool was part of the Diocese of Chester, the Diocese of Liverpool being "carved out" of it in 1880).

With its simple open brick-built design, upper gallery, double rows of generous arched windows and square, crenallated tower with clock faces, the Grade II listed building is similar in style to Cuthbert Bisbrowne's Saint James, Toxteth (1774-1775) and belongs more to the late 18th than early 19th century, when architects were sharpening their pencils for new interpretations of the gothic and classical. Inside are two stained glass windows by William Morris (1873 and 1879) on the north side of nave. Outside there is a graveyard, in a neglected condition, with mid and late 19th century gravestones. There is also a Grade II listed memorial to victims of the First World War (see photos below).

In contrast to the European continent, most churches in Britain remain empty for the majority of time and their doors firmly locked against the curious. This is a sad reflection not only on the state of parishes but also the social condition of the country. Much is a question of finances, but perhaps British church administrators could learn something about visitor and information management from their continental counterparts. This could provide a great boost to spiritual, cultural and touristic activity, and no doubt contribute to local economies.

Having said this, Liverpool, which has one of the highest concentrations of notable urban landscapes, buildings and monuments in Britain, has done well to preserve what it has against the merciless ravages of "progress". This is in no small way due to the labours of local enthusiasts and activists, many of whom provide their services for free. |

|

| |

| |

Slavery – the fly in the cultural ointment |

|

|

The merchant Edward Mason, after whom nearby Mason Street was named and where he had his mansion, is said to have been a slave trader, or to have inherited his wealth from his father who was, allegedly.

Today this area of Liverpool is famous for Edge Hill Station, the world's oldest surviving passenger railway station, built by George Stephenson in 1836 as the passenger terminus for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The company's founders included the Caribbean plantation-owning families Gladstone, Moss and Earle, and the railway's principal use and source of profit was transporting slave-produced cotton and other raw materials to the mills and factories of Lancashire.

It seems that respectable "Christians" had no qualms about reconciling their faith with the inhuman practice of slavery. While their victims suffered on the plantations of the New World, they passed themselves off as public benefactors and philanthropists back home.

See: ihbc.org.uk/context_archive/108/slavery/one.html

"Man finds his fellow guilty of a skin

not coloured like his own, and, having power

To enforce the wrong, for such a worthy cause

dooms and devote him as his lawful Prey."

From Liverpool, its commerce, statistics, and institutions: with a history of the cotton trade by Henry Smithers, Liverpool 1825. |

|

| |

World War I memorial at the south-east corner of Saint Mary's Church,

Irvine Street, Edge Hill, Liverpool. A Grade II listed monument.

"LEST WE FORGET. In memory of those who fell in the Great War 1914-1919.

God is Our Refuge and Strength.

This cross was erected by the Friends of St Mary's Church Edgehill." |

| |

Late 19th century gravestone in the form of a Celtic cross in the graveyard

of Saint Mary's Parish Church, Irvine Street, Edge Hill, Liverpool.

|

"I don't know what happens when people die

Can't seem to grasp it as hard as I try

It's like a song I can hear playing right in my ear

That I can't sing, I can't help listening"

For a dancer by Jackson Browne, from the album Late for the sky |

|

| |

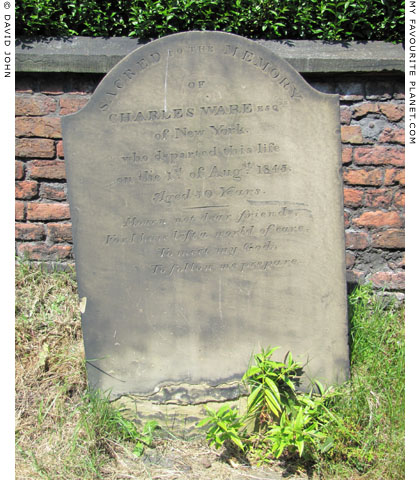

Mid 19th century gravestone, of Saint Mary's Parish Church, Edge Hill, Liverpool.

The grave of "Charles Ware Esquire of New York, who departed this life on

the 1st of August 1845 aged 50 years" and left us with these cheery words:

"Mourn not dear friends,

For I have left a world of care,

To meet my God,

To follow me prepare."

|

"Father McKenzie writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear

No one comes near.

Look at him working, darning his socks in the night when there's nobody there

What does he care?

All the lonely people

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people

Where do they all belong?

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Ah, look at all the lonely people

Eleanor Rigby died in the church and was buried along with her name

Nobody came

Father McKenzie wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave

No one was saved"

Eleanor Rigby by The Beatles (who?), from the album Revolver, 1966. |

|

| |

| |

... And last but not least ... |

|

|

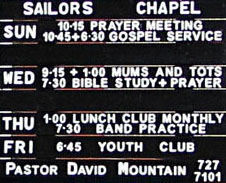

Sailors' Chapel, Beresford Road, near Herculaneum Docks (1866-1972), the Dingle.

|

A somewhat humbler place of worship than the grand temples above. The boarded-up windows give the impression that the modern single-storey brick building has been abandoned like many others in the area. But the sign outside looks freshly painted and the barbed wire adorning the exterior (symolic of Christ's crown of thorns?) seems free of rust. So there's life there yet.

If you want to find out more, visit:

www.sailorschapel.org |

|

|

|

| |

|

Year of Faith 2004 pavement,

Berkley Place, Liverpool

"Behold how good and joyful a thing it is

brethren to dwell together in unity!"

Psalm 133, VI |

|

|

| |

The themed year "Faith in One City 2004" consisted of a series of projects and events supported by the Merseyside Council of Faiths and the Liverpool Faith Network with the aim of bringing the different religious communities together.

The pavement depicts 16 stylized men and women, representing people of various faiths, standing together in a circle at whose centre is the Earth.

The religions represented are (in alphabetical order):

Bahai, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Rastafarian and Sikh.

I would like to have provided links here to each of the local religious communities, but apart from the Bahai's, all the other faiths have so many groups and factions that no one website represents any religion as a whole.

Those who are unsure or skeptical about religion, or even abhor it,

may find these Liverpool links of interest:

merseysideskeptics.org.uk

You can not be absolutely certain that the Merseyside Skeptics really do exist,

but this website claims that they do. Honest.

humanism.org.uk/meet-up/groups/student-groups/liverpool-university

University of Liverpool Humanist, Atheist, Secular and Agnostic Society,

"a non-prophet organization" (geddit?) who now have a new website at:

ahsstudents.org.uk/society/university-of-liverpool-humanist-atheist-secular-and-agnostic-society/

Ecumenicalism for infidels.

pcwww.liv.ac.uk/~chassall/ULAS/

University of Liverpool Atheist Society (ULAS) "since 2008"

Athiesm pure; none of this wishy-washy dilution with Humanism and the like.

liverpoolatheists.com/smf/

The official forum of the Atheist Community of Liverpool (ACL).

Not much going on at this forum. Maybe they don't yet have enough (dis)believers.

So now we know. Or do we? |

|

| |

Part of the Year of Faith 2004 pavement depicting the Baha'i Faith. |

| |

Part of the Year of Faith 2004 pavement depicting the Rastafarian religion. |

| |

Is anybody up there? Bill Shankly, can you hear us?

|

"I dreamt that force could be the servant of justice

And truth the servant of the state

I failed to vector in the human factor

The word is frightening when it comes too late

I tried to build a world we'd all be proud of

A place of dignity and life

But those around me had a hidden agenda

Those behind me had a hidden knife

How could there be so much hatred here

So many races out of none

So many ready to kill for an opinion

So many dying just for having one?"

Kingdom of the blind by Hugh Feathersone,

from his album Negotiations and Lovesongs, 1995

Sunset over the River Mersey, Liverpool, England.

Photo: © David John 2010 |

|

| |

Many thanks to the people of Liverpool for their Scouse hospitality, wit and wisdom. Wherever I went, somebody engaged me in friendly conversation, often explaining to me something about their area or street. It's a wonder that I managed to get around the city at all, and I wished I had had more time to spend talking with and listening to them.

Special thanks to the owners and staff of the Pineapple Hotel, Toxteth, for their hospitality, friendliness, great service, helpful advice, comfy beds and a great view across the Mersey.

Pineapple Hotel, 258 Park Road, Dingle, Merseyside, L8 4UE.

Tel/Fax: +44 (0)8000 98 86 14 www.thepineapplehotel.co.uk

Gratitude is also due to the weather gods who provided warm, sunny days during my visit to England and Wales in June 2010.

I have tried to make this article accurate, balanced, fair and hopefully interesting.

As ever, comments, criticisms and suggestions are welcome.

Please get in contact. |

| |

Merseyside icons

Put your mouse

over an image to

see further details. |

| |

Radio City Tower

Liverpool |

| |

King's Regiment

Memorial |

| |

Royal Liver Building

Pier Head |

| |

Liver bird |

| |

Polite notice

Dingle |

| |

Mersey ferry

MV Snowdrop |

| |

Port of Liverpool

Building, Pier Head |

| |

Liverpool Cathedral |

| |

Liverpool Catholic Cathedral |

| |

St. Luke's Church

Bold Street |

| |

Saint Nick's

Pier Head |

| |

Tracey Emin

bird sculpture |

| |

Bessie Braddock

Lime Street Station |

| |

Ken Dodd

Lime Street Station |

| |

gargoyle

Victoria Street |

| |

gargoyle

Crosshall Street |

| |

Statue of liberty

Lime Street |

| |

dragon, Chinatown |

| |

angel

Shaw Street |

| |

Hope University

Shaw Street |

| |

Risen Christ

by Elisabeth Frink

Liverpool Cathedral |

| |

Welcoming Christ

Liverpool Cathedral |

| |

Abraham

Catholic Cathedral |

| |

Greek God

Bear's Paw pub |

| |

Mercury

Exchange Flags |

| |

Britannia / Minerva

St John's Gardens |

| |

Justice

St. George's Hall |

| |

Liverpool Resurgent

by Jacob Epstein

Lewis's, Lime St. |

| |

Saint Margaret

Princes Road |

| |

Queen Victoria

St. George's Hall |

| |

King Edward VII

Moss Street |

| |

Benjamin Disraeli

St. George's Hall |

| |

Nelson's Monument

Exchange Flags |

| |

Philharmonic pub

Hope Street |

| |

Duke of Wellington

Brown Street |

| |

Major General Earle

St. George's Hall |

| |

Captain F.J. Walker

Pier Head |

| |

"Pro Patria"

Pier Head |

| |

Titanic Memorial

Pier Head |

| |

Merchant Navy

monument

Pier Head |

| |

suitcase climbing

Hope Street |

| |

Kantha embroidery

from Bangladesh |

| |

Superlambanana

Hope Street |

| |

Big Wheel

Albert Dock |

| |

Chinatown

Nelson Street |

| |

water tower

Everton |

| |

water fountain

West Derby Road |

Liverpool University

Brownlow Hill |

| |

letter box

Moss Street |

| |

Bleak House pub

The Dingle |

| |

Pedestrians

this way |

| |

lost shoe

Dale street

All photos

on this page

© David John

2007 - 2011

If you would like

to use any of the photos for your website, blog or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

|

| |

| |

Articles and photos: © David John 2010 - 2011

The Cheshire Cat Blog at My Favourite Planet Blogs

We welcome considerate responses to these articles

and all other content on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact.

The photos on this page are copyright protected.

Please do not use them without permission.

If you wish to use any of the photos for your website,

blog, project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr |

| |

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de |

| |

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr |

| |

| |

|