|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Cheshire Cat Blog > 2011 |

|

|

back |

The Cheshire Cat Blog

|

|

July 2011 |

|

| |

|

Do Meteora dogs dream of floating sheep? |

| |

Meteora means "rocks in the air" or "floating mountains" [1], and in certain light you can see why: huge slabs of naked rock soar up dramatically from the green valley below. The Cheshire Cat ran himself ragged around the rugged rocks in the rain, and was joined on his jaunt by an unlikely canine companion.

A shaggy dog story by David John

For Pamela Leake and Mike Cornford (wherever they may be)

"Alas! The woes of Thessaly! It is again pouring with rain..."

Edward Lear, May 1849 [2]

"Around the rugged rocks the ragged rascal ran", goes the old tongue twister, and after three days squelching around rain-sodden paths between the lofty crags of Meteora I am not so much ragged but more of a damp rag. I have been saturated so many times during the previous weeks of rambling around northern Turkey and Greece that I suspect I may start growing gills, scales and fins. Most of my clothing and footwear is wet, and with no let-up in the cold, damp weather, there seems little hope of ever getting them dry. |

|

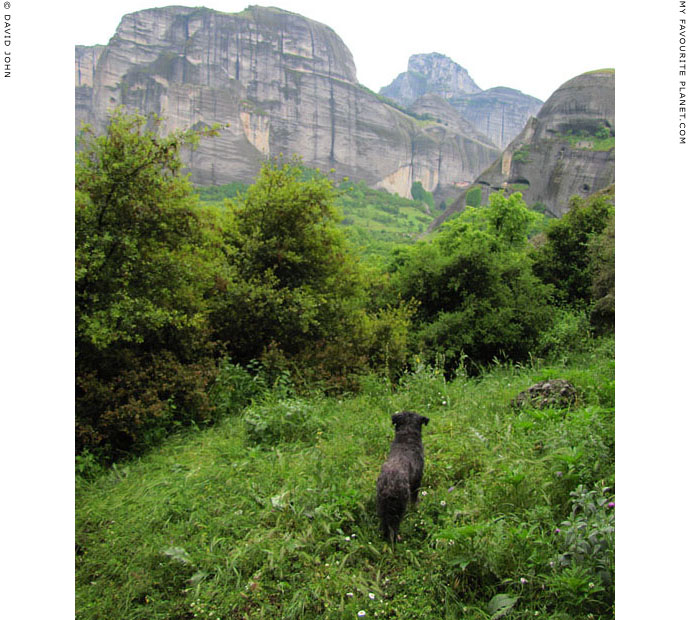

Spot the Dog wakes up

and smells the flowers. |

|

| |

Kalambaka town hall (Dimarcheion) and the rocks beyond shrouded in mist.

|

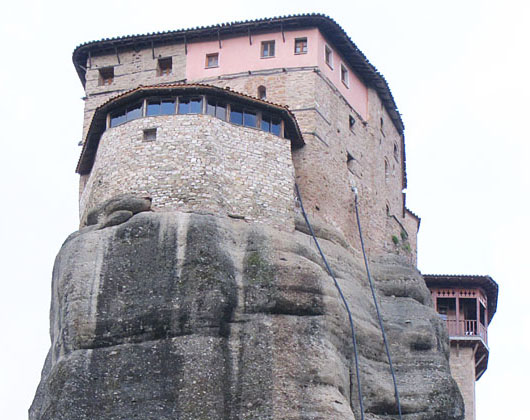

At some time in your life you may have received a postcard from Meteora. Perhaps you said to yourself: "My Aunty Nora went to Meteora, and all I got was a lousy postcard." And on it a postcard-blue sky against which slender pinnacles of rock rise gracefully like God's holy stalagmites from what appears to be a plain. Atop each of these natural columns a cute olde worlde monastery is delicately balanced like a cricket on an ear of wheat. Many literary descriptions of the topography enforce this picturesque impression. As far back as 1812, Dr Henry Holland wrote of the rocks:

"They rise from the comparatively flat surface of the valley; a group of isolated masses, cones, and pillars of rock, of great height, and for the most part so perpendicular in their ascent, that each one of their numerous fronts seems to the eye as a vast wall, formed rather by the art of man, than by the more varied and irregular workings of nature. In the deep and winding recesses which form the intervals between these lofty pinnacles, the thick foliage of trees gives a shade and colouring, which, while they enhance the contrast, do not diminish the effect of the great masses of naked rock impending above." [3]

Architect and archaeologist Charles Robert Cockerell was delighted by the place in 1814:

"Twelve sheets would not contain all the wonders of Meteora, nor convey to you an idea of the surprise and pleasure which I felt in beholding these curious monasteries, planted like the nests of eagles upon the summits of high and pointed rocks." [4] |

|

| |

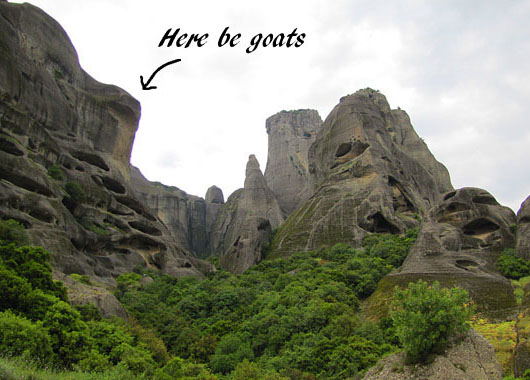

"Silvery white goats were peeping from the edge of the rocks

into the deep, black abyss below..." Edward Lear, 16 May 1849 [2] |

| |

A mother goat and her kid enjoy the view from the top of Ambraria. |

| |

| Ambraria |

|

Pixari |

Agios Nikolaos Bantovas |

| Some of the rocks which loom over Kalambaka |

|

Over a century later, even Osbert Lancaster admitted to being awed by the sight of Meteora, in spite of himself:

"Normally I am not one in whom the freaks of nature arouse an unqualified enthusiasm: stalagmites and stalactites, cliffs in the silhouettes of which the eye of faith can discern the profile of Napoleon, caves which the guide books delight to describe as 'Gothic chancels', leave me not merely unmoved but resentful; nature has no business, I consider, to go monkeying about in the province of art. But these extraordinary rocks, rising vertically from a cluster of low grassy hills divided by narrow wooded glens, like the decayed and irregular denture of some gigantic mammoth, would be remarkable even had their extravagance not been lent point by human ingenuity." [6]

When the artist Edward Lear visited in the spring of 1849, on his second journey through northern Greece, he was suffering repeated attacks of "Greek fever", exacerbated by the constant cold, wet weather. Right about now I can wholeheartedly empathize with his misery. Still, he was also impressed by the "wonderful spectacle" of this "peculiar" scenery to which he claimed "no pen or pencil can do justice". He even recommended that in order "to make any real use of the most exquisite landscape abounding throughout this marvellous spot, an artist should stay here for a month." [2] Lear himself, however, left after an overnight stay and a morning sketching the rocks.

These days most visitors don't stick around very long either. Day-trippers are shuttled in by convoys of huge tour buses, each of which disgorges up to 50 passengers who swarm through the monasteries like plagues of locusts. This mass infestation completely destroys the very isolation and tranquility which used to be the main attraction of the area and which brought the medieval monks here in the first place.

Of the innumerable hermits’ caves, 20 monasteries and around 13 smaller monastic settlements, only 6 monasteries are still inhabited. Since as early as the 1960s the remaining monks have been primarily engaged in dealing with the constant flow of tourists rather than quiet contemplation of the eternal. |

|

|

A tour bus convoy parked outside the monstery of Agios Stefanos.

Seven buses (parked in two rows) are visible in this photo,

which means as many as 350 tourists visiting the monastery at one time.

|

| In theory, it is possible to visit all the monasteries and churches in one day, but their various opening times are so cunningly devised that the independent traveller would have to plan a tactical campaign to achieve this and avoid the crush of tour groups. Anyone genuinely interested in the surviving religious and artistic treasures of the monasteries and churches, the magnificence of the landscapes and the hospitality of the locals is advised to stay for at least two days. |

|

| |

Wrong church, dummy!

The one you are looking for is always that little bit further up the hill. |

| |

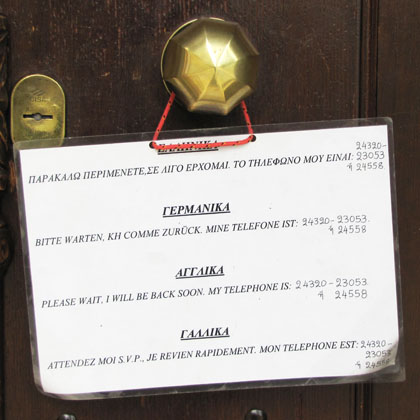

"Please wait. I will be back soon..."

Sign on the door of the (closed) Church of the Assumption

of the Virgin Mary, Kalambaka.

Opening hours: 8:00 - 13:00 and 15:00 - 20:00 |

| |

Opening times of the monastery of Agios Nikolaos Anapafsos

9:00 - 15:00 (or 15:30 for Greeks, apparently). Fridays closed. |

| |

If you don't manage to see the monasteries, because

of the weather or the Byzantine opening times, this

helpful scale model has been thoughtfully provided. |

| |

This is assuming, of course, that the weather plays along with your travel plans. Although Greece is generally famous for its hot, dry summers, northern Greece is subject to sudden and often violent rain and hail storms at all times of the year. From my experience, they are usually due to heavy masses of cloud which suddenly appear from the Balkan land mass to the north and dump their damp loads over the mountains, plains and coasts of Macedonia, Thrace, Epirus and Thessaly. It is this rainfall which makes the farmable lands of these regions so fertile, especially compared to the more arid, drought-prone areas of the mid and southern Aegean. It also helps explain why mass tourism has not been developed here on the scale of southern Greece.

Generally though, such storms are quite short, and rarely last more than an hour. Except this year. It has been a long time since I have seen such persistent rainfall, cold and gloomy weather outside Britain. Everywhere I've been, from Istanbul to Trikkala, people have been complaining – between bouts of coughing and sneezing – of the seemingly endless winter. Here it's the second most popular topic of conversation after the equally endless Greek economic crisis. Such talk of dreadful weather is somehow very British, and a few Greeks joke that I have brought the British weather with me. I'm tempted to tell them that it's all part of a sophisticated Anglo-Saxon conspiracy to lure tourists back to Margate, Blackpool and Llandudno. Instead, I laugh along with the bad weather banter, sip my Greek coffee and wait for the rain to stop. |

|

| |

Waiting for the rain to stop.

|

Outside, the famous rocks of Meteora are hidden by the lowest of low clouds, mist and incessant drizzle. Having rarely witnessed such a long soggy spell, people here remain confident that it will soon be over. “Tomorrow is beautiful,” they keep reassuring me. After a couple of long bus journeys, with fellow passengers sneezing and wheezing around me, and three days of Meteora mist I realize I’m coming down with what used to be quaintly referred to as “a chill”. My energy, enthusiasm and willingness to share the locals' optimism for a “brighter later” are draining rapidly down through my soused socks and leeching into the rich, moist Thessalian soil.

The carefree spirits of the Greeks here are also somewhat dampened by the gloom which is keeping the tourists away. Most of the hotels, tavernas, cafes, bars and shops remain yawningly empty, and since it's the beginning of the tourist season many locals desperately need to see them fill up after the financial doldrums of winter. But right now it's hard to imagine all the places full, even in high season: there are just so many of them, and new ones seem to be springing up every year. The local town of Kalambaka and the neighbouring village of Kastraki are gradually spreading out around the mouths of the vales of Meteora, and one wonders how long it will take before the expansion heads up-valley and hotels and bars begin appearing among the rocks themselves. In the present economic climate worst-case-scenario paranoia takes a grip: that the monasteries will be privatized and turned into exclusive “theme boutique hotels” or “panorama restaurants”, or sold off to wealthy Russians as holiday villas.

A local hotel owner sadly agrees that there are just too many businesses in the area and that the expansion may not be economically sustainable. Then, later in our conversation, he asks me if I have seen the new, bigger hotel he has just built on the other side of town. There is a Persian saying: “If a word burns on your tongue, let it burn.” I hope he doesn't notice the smoke coming out of my ears. |

|

Meteora building boom

|

| |

Kastraki chimney

|

Talking of smoke, one of the unexpected drawbacks of this weather is that the fumes pouring out from the chimneys of wood and oil stoves hang around in the heavy, damp air of the villages, burn in the nose and throat and make breathing as you slog up the steep streets just that bit more difficult. There's real village atmosphere for you.

The drizzle appears to lift slightly and my coffee is finished - those tiny Greek coffees don’t go far - and I can't face another, or the blaring TV (all the cafes around here have one; it must be obligatory). So I bid farewell to the handful of Greek men who make up this café society and head off once more with the water-logged ruins of hope in the direction of the valley of rocks.

As I start the ascent towards where the buildings and mesh of overhead telephone cables end and the road and footpaths wind upwards between the rocks, the mist drifts away, the sun actually appears, and for the first time I can see the tops of Lear's “vast sheer perpendicular pyramids”. Wonderful! But the temperature rises rapidly from around 5 degrees Centigrade to the mid 20s. I am forced to do a quick striptease in the middle of the village, removing my jacket, pullover and heavy shirt. Now I'll have to carry the cursed things rather than wear them. Oh well, onwards and upwards.

Things are looking up, I get into my stride and lose myself in the newly-revealed splendour all around me. I feel like singing, but exercise restraint and indulge merely in a bit of low humming. Ye gods! No sooner have I left the last houses behind me than an enormous crack of thunder shatters my reverie. Even as I look up, the newly arrived storm clouds – huge dark bruisers with rolled-up sleeves which make the earlier gentle drizzlers look like wimps in tutus – have begun beating up the long-suffering pinnacles with heavy fists of rain. Misery by a thousand blows. The sun retreats and so do I. Exit, stage, er... downhill.

In the so-called “plain” below Meteora's rocks (pretty steep for a plain, I'd say) there is no place to shelter. Few of the trees could do the job, and anyhow, you don't want to be standing under one during a thunderstorm, do you? At this time of year there are also few places where you can sit for a rest, as the grass is too long and wet; although in summer there are several knolls-with-a-view on which you can picnic. Luckily, there is a small taverna right at the very end of the village, which turns out to be very pleasant, with a more rural atmosphere, and cheaper than those “downtown”. (And there was me moaning that there are too many businesses around here. I will have to, ahem, class this one as an exception.)

So I sit in the taverna, the only customer, and quickly re-apply the layers of clothing while the temperature plummets, sucker-punches of rain descend and thunder and lightning (very, very frightening) scare the wits out of the waitress and me. The thunder is mega loud, amplified no doubt by the acoustic properties of the rocks. It sounds like a mighty streak of lightning hits the rock right above us. BAM! And the power in the taverna goes out. No more light, no more bouzouki music. This is going to be a long one. |

| |

Swing low, sweet chariot.

|

| |

naked lunch |

I nurse a beer, blow my nose and reflect on the situation. My Big Fat Greek Travel Plan isn't going at all well. Usually, I find May and June excellent months to travel through Greece and enjoy the sights and landscapes before the place gets too hot and clogged with tourists. I mean, a little bit of cloud cover and even some rain can make a place look quite picturesque; you might even catch a glimpse of a rainbow. Whoopee! But this! Exactly this kind of weather and its relentlessness is proving as disastrous to my travel plans as they were for Lear's in 1849 (he was attempting for the second year running to reach Mount Athos). To make things worse all my planned destinations are relatively high altitude locations, rendered totally invisible by low cloud. I have already had to cancel visits to Mount Olympus (first there was a mountain, then there was no mountain ...) and the Vale of Tempe, thinking that a couple of days walking around Meteora would be preferable to hanging around in a fog-bound pine forest. And now I'm thinking that my projected route around the Pindos Mountains, through Metsovo to Ioannina and eventually to elevated Delphi is bound to be a wash-out too.

Enough, I tell myself, is enough. I've had it with this lousy weather, thank you very much. This I can get in northern Europe at wholesale prices. Down south in Athens and beyond it's warm and sunny. And warm and sunny is exactly what I need right now: go straight to Athens and get on a ferry for the hottest, driest island I can find, burn off these accursed sniffles and finally get the Thessalian damp out of my clothes. To Hell with pinnacles, Meteorites, candle-darkened icons, mountain fastnesses and sacred groves. Get me outta here!

I try to placate Disappointment, Regret and Cultural Curiosity, but give up and move away from these morose entities to raise my glass to Sunshine and Sandcastles, and smile triumphantly with Decision and Escape. Is that waitress giving me funny looks?

So that's it then. I shall go back to my hotel, turn the heating up full, have a hot shower, pack my stuff, get into bed, watch a Greek soap and eat some of those emergency chocolate biscuits which have been loitering in my luggage for just such an occasion. And tomorrow morning I'll be on that train to Athens.

What a relief. I'm already looking forward to the train journey, and consider celebrating my executive decision with another beer, when, as suddenly as it arrived, the storm departs. |

|

A dark and rainy night in Meteora.

|

As I emerge from the taverna the lights and the bouzouki music stutter back to life, the awning out front is still dripping and a shoal of tour buses slosh by on their way back down the hill, their huge tyres splashing a couple of hikers walking along the side of the road. They hardly seem to notice: they look as though they got caught in the storm somewhere up there, and are already so thoroughly wet and discouraged that only complete concentration on reaching anticipated dry towels, a change of clothes and a couple of belts of ouzo are keeping them slithering and squelching on... For some reason, the name Llanberis springs to mind.

I cross the road to look over the bushes at the bullying clouds swaggering off behind the great rocks and on to terrorize the next neighbourhood. Good riddance! Higher above there is still a sheet of grey covering the sky, but it looks harmless enough and there are even a few gaps admitting flecks of yellow sunlight down to the post-diluvial surface, with a few playing among the peaks of the snow-covered Pindos mountains on the other side of the Peneios valley. It's actually quite a beautiful scene, and the downpour has washed away the acrid smoke. I breathe deeply and revel in the intoxicating fragrance of the sweet, green, earthy, pollen-laden air that you only get after spring rain. Wonderful! My heart may not exactly be soaring like a hawk, but it is hovering quite nicely. |

| |

You never quite know what's around the next bend.

|

Maybe it's the pollen, or maybe it's the beer, but I rashly decide to turn uphill rather than down. Well, I tell myself, Sunshine, Sandcastles and the others, it can't do any harm just to walk up to the next bend in the road and take a last look at the vista before retiring to the shower, the soap and the biscuits, can it? Who knows when we'll pass this way again? Decision and Escape seem uncertain, while Disappointment, Regret and Cultural Curiosity, still sulking, mumble unenthusiastic assent. And as I turn I almost step on a small, scruffy looking dog.

| |

The wet flokati look.

|

“Oh sorry, I didn't see you there. Where did you come from?”

He looks up at me with those big doggy eyes (well, what other kind of eyes would he have?) and wags his tail a bit. Over the years I've become very wary of Greek dogs: either they get very aggressive or they follow you around for ages until they realize you aren't going to feed them, then they get aggressive. They prefer to practice this kind of behaviour in packs, but one, however small, can be as much of a pain as ten. And this is just as true in a city like Athens as it is in the country. They'll quite happily take on passing cars and trucks, but pedestrians and cyclists are easy game.

In his Journals of a landscape painter in Greece and Albania Lear mentions dogs no les than 43 times, describing them variously as "huge", "immense", "formidable", "wolfish", "lion-like", "angry", "furious", "fierce", "ferocious", "rabid", "ravenous" and "brutes" (a veritable thesaurus of canine cruelty), which lurk everywhere in "packs", "companies" or "troops" of as many as "eighty to a hundred", often hiding among "innocent looking bushes" and rushing out "with unpleasant abruptness" to attack passers-by. Despite some close shaves, he remained quite philosophical about such dangers and tried to let nothing get in the way of his sketching. He wrote the following in Yenidje (Giannitsa), Macedonia, on 14 September 1848:

"The village, composed of scattered wooden houses, is full of prettiness; but fierce dogs, when the rain ceases, prevent my going near any of the buildings, as much as a multitude of wasps do my eating a peaceful dinner on the khan platform. Yet, spite of dogs, wasps, and wet, distances veiled over by cloud, and all other hindrances, there is opportunity to remark in the scene before me a subject somewhat ready-made to the pencil of a painter, which is marvellous: it is not easy to say why it is so, but a picture it is. Copy what you see before you, and you have a picture full of good qualities, in its way – a small way, we grant – a mere village landscape in a classic land." [2]

Cockerell and his companions also narrowly escaped being savaged by over-enthusiastic guard dogs in 1814, while walking through the village of Vareatis, not too far from here:

"In this walk we should probably have suffered an attack made upon us by some fierce Molossian dogs, had we not been armed with our travelling sabres; Mr Cockerell happening luckily to turn round discovered them running at us without barking or making any signal ..." [5]

Not that I would recommend anyone travelling through Greece with a sabre or flintlock pistol these days, or attempting to do battle with local hounds. Often saying something with an authoritative voice will get rid of the malignant mutts. It doesn't matter particularly what you say – “bugger off, dogs!” or “You ought be ashamed of yourselves!” or “This will go down on your permanent record!” – it's the firm tone that counts. If this doesn't do the trick and you are not toting a walking stick, an umbrella or an Uzi, try swinging your bag or pack around threateningly, especially if it's nice and heavy. Throwing stones or your packed lunch at them may also work as a last resort. It's better to assert yourself with them or confuse them rather than raise the stakes by angering them. But generally, unless they are defending sheep, their young or territory, they'll usually back off: their snarls are worse than their snaps.

When walking in the country I often carry some biscuits or food especially to bribe off pesky pooches, although sometimes this can prove counter-productive: a tidbit will divert curs from immediately attacking you, but once they've wolfed the proffered morsel down, they may literally hound you for more.

This little guy doesn't look particularly like a trouble maker, but you never know, do you? Anyway, I'm only carrying a bottle of water, some Fisherman's Friends (these lifesavers I always have about me; never leave home without them) and a cheese pie; nothing then of interest to a canine gastronome.

“If it's chow you're after, young lad, you've picked on the wrong human. Perhaps you should try those two,” I say, pointing at the seekers-after-dry-towels who are still to be seen solemnly portaging their dismay down the hill. “They're bound to have a salami sandwich or something left over from their hike.”

He cocks his head appreciatively, but tacitly declines the offer.

“Hmm, is that so? I hear they do very fine lamb chops in this taverna. Perhaps the charming waitress will slip you one?”

This doesn't seem to appeal either.

“No? Well, you should know, being from around here and all.”

I notice that the waitress is staring at me through the taverna window, with a look of stupefaction, and the cook, wiping his hands on a dish cloth, has left his pots and pans and joined her to watch what this demented foreigner is up to. It occurs to me that from their observation point they can’t see the small dog with whom I am conversing. They probably think I'm a mad person talking to myself. “Look,” I feel like telling them, “I'm just having a perfectly normal conversation with this diminutive local. I'm not really insane. Honest.” But I decide simply to take my leave of my new acquaintance and depart with as much dignity as I can muster.

“Well, look at the time! It's been nice meeting you, but I really have to get going now. So if you'll excuse me...”

As I start to walk up the hill he trots quietly alongside me, rather than behind as is usual with strays. “You've been well brought up, haven't you?”

This he knows already.

It looks like I’m stuck with him, or he’s stuck with me, so I may as well get used to it. I still suspect his motives, though. What if his fellow gang members – all slobbering, rabid Dobermans and pit-bulls – are lurking around the next corner and waiting to mug biscuitless and Uziless me? But he seems to show no sign of interest in chasing the passing cars, and he even totally ignores a couple of extremely tempting German cyclists swishing downhill, exchanging German cyclist quips with one another as they freewheel toward Kastraki. Interesting, I muse, either he’s a subtle rogue, with as much cunning as patience, or else he's just what he seems: an apprentice sheep dog with an afternoon off and a penchant for human company. I decide to trust him and relax the grip on the strap of my weighty daypack.

“Well,” I venture, “I'm not going very far, you understand. Just to that next bend, let's say as far as Agios Nikolas Anapafsas. Then it's back down the hill to Kalambaka for me. Not up for a long jaunt today.”

This appears to be fine by him, I think. |

|

Clouds over the snow-covered Pindos mountains.

|

A typical human, I'm already thinking of giving him a name. “Should I call you Cerberus, perhaps? No, unfair. Forgive me, you hardly seem the savage type, you're evidently too smart to fall for a sop, and as far as I can see, you only have one head. And anyway, the weather may be hellish around here, but it's hardly Hades, is it? I could imitate Orpheus and try to soothe you with music, but I'm not sure how you'd take to my humming. It's not to everyone's taste, I suppose. OK, forget that idea, then.”

I can feel the eyes of the waitress and the cook burning at my back. I hope that we get to that bend in the road soon, and wonder if there is an alternative route for the return journey. Good thing I'm leaving town tomorrow: word gets around quickly in small places like this.

| |

"PROSOKI SKYLOS"

Beware of the Dog!

|

Most Greeks don't have much time for dogs, they don't trust them and generally try to avoid them. This is understandable to a certain extent. It used to be that very few people here kept them as pets; they are used as working animals and guards by farmers, businesses, gangster-types and the police. Occasionally puppies were bought as gifts, particularly for children, but shortly after found themselves dumped on some roadside (the puppies, that is, not the children). Hence the considerable number of strays chasing cyclists around town and country. “Dogs cost money and are always up to no good,” a Greek friend told me earlier this year. But in recent years, with the general rise in disposable incomes (for those who have work) and the increase in violent burglaries (by some of those who don't), more families have taken them into their homes, if not quite to their bosoms. But of the few Greeks I know who have dogs, none have given them a Greek name; they prefer foreign names such as Olga, Boris, Rex, Rover, etc., or just call them simply “skylo” (dog). Presumably a Greek name such as Dimitri, Maria or Yannis would be considered disrespectful or even blasphemous, as these are saints' names.

I once dubbed a black Labrador Biggles, because his enormous floppy ears reminded me of the leather ear-flaps of the fictional First World War fighter pilot’s flying helmet. He became the centre of conversation, as I always had to explain to Greek people the British fascination with the air ace. Eventually, he went to live on the Albanian border with a friend's grandmother, who renamed him David. |

|

A huge, ferocious guard dog? |

| |

"You better believe it, pal."

|

“I dub thee Spot,” I inform Spot. “It's not very imaginative, I know, but it's only a temporary measure.”

Spot suddenly runs ahead of me and disappears into the bushes on the left side of the road. “That's it, then,” I think, “I've insulted him now, and he's off.” But he reappears, looking quite excited and does a little dance around me, then returns to wait for me at the gap in the bushes he had entered.

It's at this point of the story when you think, “Gee, he's trying to tell me something.” OK, I'll play along. When I get to where he's waiting, I see a steep track winding up through a field. It's not signposted as a footpath, and looks like a typical farmer's track, just wide enough for a tractor or a flock of sheep. Does this lead to where he lives? And if so, maybe there really will be a gang of terrible farm dogs – his big brothers – lying in ambush up there. I also notice a spent shotgun cartridge lying on the ground. Do they shoot trespassers around here? Gulp.

But the track is enticing, and there's Cultural Curiosity whispering encouragement in my ear (or is it just Nosiness impersonating her?). Spot gives me an encouraging “this way, old chap!” look and heads up the track.

Reader, I followed him. |

|

spent shotgun

cartridge |

|

| |

"Here it is: Meteora's own mini Shangri-La." |

| |

"Well, what are you waiting for, a written invitation?" |

|

And here are some of the things we saw ...

plenty of poppies |

| |

Modern multi-storey beehives in their own spacious grounds |

| |

A mysterious stone circle |

| |

The abandoned monastery of Doupiani |

| |

The Ruins of the Agios Georgios Monastery

(Mantilas), outside the village of Kastraki.

Every year, on Saint George's day, local young men

risk life and limb climbing up to this cave to replace

the colourful scarves (mantilas) which adorn the ruins. |

| |

The Monastery of Agios Nikolaos Anapafsas, founded in the 14th century. |

| |

The Monastery of Agios Nikolaos Anapafsas |

| |

Wild flowers growing on a rock face |

| |

Wisps of Meteora mist |

| |

The bell tower of the Monastery of Agios Nikolaos Anapafsas |

| |

Some craggy crags |

| |

Trees growing on top of a pinnacle |

| |

a green cleft |

| |

The Monastery of Roussanou, dedicated to Saint Barbara, built 1530. |

| |

The Monastery of Roussanou |

|

| |

A few aspects

of Meteora.

Put your mouse

over an image to see further details. |

| |

Rock of

Agios Stefanos |

| |

Agios Kosmas |

| |

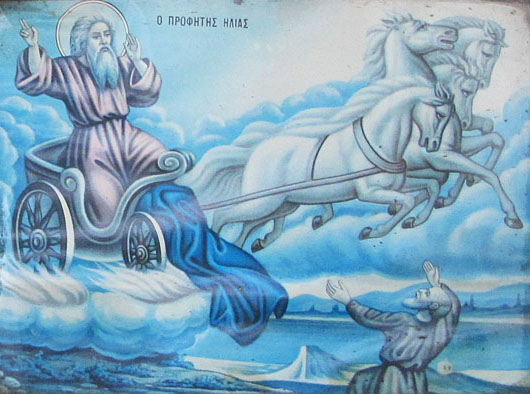

Prophet Ilias |

| |

one few east |

| |

one flew west |

| |

one flew over

the monk's nest |

| |

cock-a-doodle-tap |

| |

keep on rocking

in the free world |

| |

Dionysos

ancient... |

| |

... and modern |

| |

Agios Nikolaos |

| |

Agia Paraskevi

"Saint Friday" |

| |

The plates

have eyes |

| |

Hermes,

messenger of the

gods and patron

of the Greek

postal service |

| |

| |

|

The Monastery of Roussanou (left), with the Pindos mountains in the background. |

| |

green and grey |

| |

The rock of Agion Pnevma (left) |

| |

The view westwards to Kastraki, across the valley

of the Peneios River and the Pindos mountains. |

| |

The rocks of Plakes Keleraka |

|

Time to depart from Meteora

For now, it's so long from the Cheshire Cat ...

... and so long from Spot the dog. |

| |

"I say hello..." |

| |

"... And you say good bye." |

| |

The railway line from Kalambaka to Trikkala on the Plain of Thessaly.

"The wide Thessalian plain ... has little but its width to commend it." Osbert Lancaster |

| |

| |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

Sorry about all these notes. While writing this blog I happened also to be researching for an article about prominent travellers in Greece and got quite carried away.

It once occurred to me that some academic publications seem to consist of a volume of footnotes and references which equals or even exceeds that of the actual main text. The logical extension of this would be a book containing just one letter or character – or, even better, nothing at all, not unlike John Cage's compostion 4'33" (four minutes, thirty-three seconds of silence) – with footnotes and bibliographical references, which in turn require voluminous explanations, further qualified by sub-sub-notes, and so on (listed numerically, alphabetically, alphanumerically, with a forest of dingbats and asterisks, etc) ... until the subtexts branch off and spiral into infinity, in a way which would send even Jorge Luis Borges around the bend. At some point pendantry would sublimate into mysticism.

1. Metéora (Greek, Μετέωρα). The Greek word metéoron (μετέωρον) is today used to mean suspended, hanging, dangling, floating in the air; oros means mountain. Meteora has been variously translated as suspended rocks, rocks in the air, floating mountains, etc.

The name of the town Kalambaka (Greek, Καλαμπάκα), is from the old Turkish Kalé Bak, meaning "strong fortress"; although it has been suggested that it also signified strong rock or pinnacle, rather like the German "Berg" (mountain) and "Burg" (castle) derive from the same root. Thessaly was occupied by Ottoman Turkey from 1395 until 1881, when it became part of modern Greece following the Treaty of Berlin (1878).

The name is also transliterated as Kalabáka or Kalampaka; μπ is equivalent to MP (as in μπύρα for beer), since there is no single letter for B in modern Greek, βήτα (Beta) being prounounced "veeta".

In ancient times it was the city of Aiginion, and from at least the 10th century AD it was the Byzantine fortified bishop's seat Stagoi (Στάγοι, "the saints").

Kastraki (Καστρακί), the name of the neighbouring village, is Greek, meaning literally "little castle". |

|

|

| Some previous visitors to Meteora |

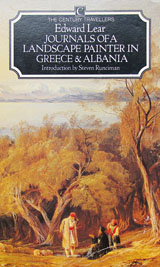

2. Edward Lear, Journals of a landscape painter in Greece and Albania.

R. Bentley, London, 1851.

Edward Lear (1812-1888), English artist, illustrator, author, and poet, particularly famous for his nonsense poetry and limericks. See some nonsense by and about Edward Lear at The Cheshire Cat Blog, 7 October 2010.

He was a prolific artist with considerable skill as a draughtsman and colourist. Today his vivid ornithological and landscape drawings, watercolours and paintings sell for high prices. However, during his lifetime he had difficulties selling his pictures and was often in debt, despite having taught drawing to Queen Victoria for a short time and commissions from the Zoological Society, the Earl of Derby and other wealthy patrons. With the support of influential friends he was able to travel widely through Europe, the Middle East, India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Books resulting from these journeys proved more popular.

In the late 1840s, when Lear travelled though Greece and Albania, the region was not quite as dangerous as it had been when Byron, Cockerell et al passed through (see note 4 below), but still a daunting prospect for any mortal. Never a physically robust man, Lear suffered from short-sightedness, epilepsy, asthma, bronchitis and had caught malaria as well as being injured by a fall from a horse on an earlier visit to Greece. On his return in 1848, at the beginning of of these journals, he had to flee from a cholera epidemic in Thessaloniki and made the courageous decision to travel alone (i.e. with a local dragoman as guide, servant and translator, but without the company of fellow northern Europeans) through this wild terra incognita, as he did again on his 1849 trip, which included the visit to Meteora.

Since the principle medium of communicating his experiences on these two journeys was meant to be his pictures, the private journals, which he was only later persuaded to publish, lack detailed descriptions of the places he visited. However they remain a valuable historical document and provide some insight into the people, life and conditions here at the time, as well as his personal reactions to them. Through all the highs and lows of his travels, Lear retains an admirable resilience of spirit and a gently ironic humour, which help make the journals well worth reading.

See also:

A Blog of Bosh, dedicated to Edward Lear,

nonsense literature and more:

nonsenselit.wordpress.com |

Edward Lear

Drawing by William

Holman Hunt, 1857 |

| |

Journals of a landscape

painter in Greece and

Albania by Edward Lear.

Century Hutchinson, 1988. |

| |

|

3. Dr Henry Holland, Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia, etc. during the years 1812 and 1813, Chapter XI. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, London, 1815.

| |

Dr Henry Holland,

from a portrait

made in 1873.

|

Dr Henry Holland (1788-1873), born in Knutsford, Cheshire, was related to Josiah Wedgwood, Charles Darwin and Elizabeth Gaskell. He rose to become consultant physician to six prime ministers, Physician Extraordinary to King William IV and Queen Victoria, Physician in Ordinary to Prince Albert, president of the Royal Institution of Great Britain and was created a baronet in 1853. He wrote a number of books, essays, articles and poems on several subjects, particularly his two main passions, medicine and travel.

Like all educated gentlemen of his day, Holland had received a thorough grounding in the classics and drawing, and like most of those who made the grand tour around the Mediterranean, it sometimes seems as if he rode through Greece with the tome of an ancient geographer in one hand (conjecturing on the possible connection between some eroded blocks of marble strewn over a rural hillside and an ambiguous passage from Strabo) and a pencil in the other. Presumably one of his locally-hired servants held his horse's reins for him and another his sketch book.

Typical also of such literary travellers is the enthusiasm with which they regale us with copious quotations from Homer, Strabo, Livy, Pausanias et al in Greek and Latin (plus the occasional exclamation in French, Italian, Turkish or Albanian), without entertaining the slightest suspicion that any reader would require a translation. I have often wondered about the grip on reality possessed by authors of "popular" books about Greek history which they litter with untranslated quotations in Greek; did it not occur to them that if the reader was capable of understanding these pearls of ancient wisdom they would hardly need to read such a book? Έτσι είναι η ζωή (c'est la vie).

As a physician and man of science (the word scientist was yet to be invented), Holland's interests went beyond the discovery of ancient ruins: he was one of the first modern travellers to attempt a scientific survey of Greece, studying the history, geography, topography, mineralogy, botany, ethnicity as well as the political, social, economic and medical conditions in the places he visited. At that time, before the paradigma-shattering discoveries of the geologist William Smith (ironically Smith completed his famous geological map of part of Great Britain in 1815, the same year as Holland's book was published), Charles Darwin and Heinrich Schliemann, there were more questions than answers concerning natural and human history. His researches were also limited by how long he was able to spend in any location while travelling on horseback between the relative safety of one town, village or khan (roadside inn) and the next; dallying or camping out in the countryside was not an option in an age of robber clans.

His rather old-fashioned writing style – even compared with some of his contemporaries – though noble and poetic, did not lend itself well to methodological description, for example of complex topographical features such as the Meteora. Modern descriptive narrative was still in its infancy. Colonel William Martin Leake, who published his The topography of Athens six years later, and Travels in Northern Greece in 1835, presumably learned from the failings of Holland and others in this respect. Leake's military experience as an artillery surveyor and instructor must have taught him to produce concise and accurate (if somewhat dry) reporting, and his works on Greece were long considered standards for topographers, historians, archaeologists and travellers; Osbert Lancaster (see below) referred to him as "the ever-admirable Colonel Leake".

Holland modestly omitted from his book accounts of places and subjects which he considered had already been covered by other writers, as well as much of the data he had collected on medical matters (perhaps to the great relief of his editor and publishers). He had also managed to lose many of his sketches, maps and notes during a ferry crossing in northern Greece. What he did manage to save and publish remains a fascinating account of extraordinary journeys and a treasure trove for researchers in many fields.

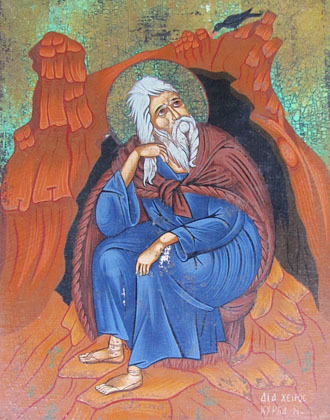

Despite his more scientific approach, he was by no means an objective observer and often betrays his northern European prejudices. The forms and practices of the Greek Orthodox Church in general and monasticism in particular were anathema to him as a native of Protestant England. It would take until the 1830s before Robert Curzon (1810-1873, from 1870 the 14th Baron Zouche) made a somewhat deeper investigation into Orthodox monasteries, including Meteora (published in Visits to Monasteries in the Levant, John Murray, London 1849), although a major motive for his visits to these establishments was to acquire their old manuscripts.

Here are a few further extracts from Holland's account of his visit to Meteora, which demonstrate his charming style, his love of nature and his disdain for monasticism:

"Long before we reached the town of Kalabaka, our attention was engaged by the distant view of the extraordinary rocks of the Meteora, which give to the vicinity of this place a character perfectly unique to the eye, and not less remarkable in the reality of the scene."

"When we approached this spot, the evening was already far advanced, but the setting sun still threw a gleam of light on the summits of these rocky pyramids, and shewed us the outline of several Greek monasteries in this extraordinary situation, and seeming as if entirely separated from the reach of the world below. For the delusion might have been extended to the moral character of these institutions, and the fancy might have framed to itself a purer form of religion amidst this insulated magnificence of nature, than when contaminated by a worldly intercourse and admixture. How completely this is delusion, it requires but a hasty reference to the present and past history of monastic worship, sufficiently to prove. It is the splendour of nature alone, which is seen in the rocks of Meteora; and the light of the sun lingering on their heights, shews only those monuments of mingled vanity and superstition, which have arisen from the devices of selfish policy, or of mistaken religion."

"The monks whom vanity or superstition condemned to an abode in this place, might once perhaps have obtained something of that fame, which Simeon Stylites purchased for himself by a similar, yet more exalted degree of religious inflictions. But these days and opinions are gone by, and the wretched devotee of Meteora now procures little more than the pity or contempt of the world, upon which he looks down from his solitary and comfortless dwelling."

Holland on his visit to the monastery of Agios Stephanos:

"We were afterwards conducted into the chapel, a small building, no otherwise remarkable than for those tawdry and tasteless ornaments which are so common in Greek churches; and of which, though now greatly decayed, our monks appeared not a little proud ... " |

|

|

| |

Part of Dr Henry Holland's map of Greece (1815), showing the Plain of Thessaly

and the position of Meteora to the east of the Pindos mountain range. |

|

|

GRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR!

|

4. Thomas Smart Hughes (1786-1847), Travels in Sicily, Greece, and Albania, Volume I, Chapter XVII. J. Mawman, London, 1820.

The quotation about Meteora by Charles Robert Cockerell is from a letter he wrote in Livadia, 9 February 1814, to Thomas Smart Hughes and Robert Townley Parker in Ioannina.

During the winter of 1813-1814 Cockerell travelled with Hughes, Parker and others from Athens, through central Greece to Epirus, in northwestern Greece. He returned alone to Athens via Meteora (30-31 January) and Thessaly in January-February 1814, writing the letter on his journey.

(This extract is also quoted by Edward Lear [2] from Hughes' book.)

5. Ibid. The incident involving the "fierce Molossian dogs" is related by Hughes himself. The large, mastiff-like Molossus breed, originally from Molossia in Epirus, was well-known in ancient times, and used for guarding property and livestock, hunting, fighting and in warfare. The ancient Greek word for hunter was Κυνηγός (kynegos), literally "leader of dogs". The original Molossus is now extinct, but its genes live on in several modern breeds. |

|

Ancient Greek hound,

one of two akroteria

on the grave enclosure

of Lysimachides of

Acharnai (eponymous

archon of Athens in

339/338 BC), on the

Street of the Tombs,

Kerameikos, Athens.

Hymettian marble.

Circa 320 BC.

Kerameikos Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. P 670. |

|

| |

Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), English architect, archaeologist and great-great-great nephew of the diarist Samuel Pepys. He made his grand tour (peregrinatio academica) 1810-1817, travelling through Italy, Turkey, Greece and southern Albania (Epirus, today part of Greece). He was fortunate - or rather, well-connected - enough to get a free passage from Plymouth to Constantinople (Istanbul) as a king's messenger, taking dispatches to the British ambassador there. The aged ship hired by the government for what turned out to be an adventurous voyage was called The Black Joke.

* The pencil drawing of Cockerell (right) was made by the French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres some time after the two met in Rome in the summer of 1816, as the former was returning to England from Greece.

Like many grand tourers of his day - well-to-do young gentlemen from northern Europe - he felt it a kind of patriotic duty to dabble in a bit of amateur archaeology. He got lucky, and along wih fellow architect John Foster of Liverpool, Carl Haller von Hallerstein, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, Jakob Linckh, Peter Oluf Brøndsted and others, dug up and sold parts of the ancient Greek temples at Aegina (1811) and Bassae (1811-1812). Such exploits made him a hero to the European intelligentsia, but a thief and a vandal among Greeks who view his removal of the Aegina and Bassae marbles as despicable as Lord Elgin's "plunder" of the Parthenon (see Edwin Drood's Column, 21 June 2011).

By chance, as Cockerell, Foster, Haller and Linckh were sailing for the first time to Aegina from Athens in April 1811, they came alongside the Royal Navy ship which was carrying not only part of Elgin's booty but also Lord Byron, who was leaving Athens for Malta, and they went aboard for a farewell glass of port wine with him.

See further information about Cockerell and the "Bassae marbles" on the Niobe page in the MFP People section.

Travelling around the eastern Mediterranean in the early 19th century was a perilous business: apart from the dangers of the elements, inept ships' captains, poor horses and bad or non-existent roads, war with Napoleon was still going on, as well as that between Russia and Turkey; and travellers were prey to French privateers and pirates by sea, and on land to robber bands, corrupt or ignorant officials and other species of rogues, as well as malaria, cholera and the plague, to say nothing of mosquitos, fleas and packs of dogs. Accounts of the adventurous journeys of Cockerell and others are replete with tales of derring-do, involving kidnappings, robberies, stand-offs, sabres and pistols. Some of Cockerell's own accounts can be found in Hughes' book and:

Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817: the Journal of C. R. Cockerell, R. A., edited by his son Samuel Pepys Cockerell. Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1903. At the Internet Archive.

|

|

C. R. Cockerell

Drawing by Ingres * |

Fop the dog

From his journal we learn that Cockerell travelled from England with his Skye terrier, Fop. This seems a rather eccentric or capricious thing to do, rather like the Belgian cartoon character Tin Tin travelling around the big, bad world with his white wire fox terrier Snowy (a.k.a. Milou).

[ Meteora trivia: the rocks of Meteora were used as a setting for the 1961 French live-action film Tintin et le mystère de la Toison d'Or (Tin Tin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece). ]

Sailing from Constantinople to Athens, Cockerell stopped off on the island of Andros, where "Fop, my dog, fell into a well and was rescued with great difficulty. One of the peasants, who had never seen anything like a Skye terrier before, when he saw him pulled out took him for a fiend or a goblin, and crossed himself devoutly."

When he left Athens for Crete (he had intended to visit Egypt but ended up visiting Anatolia, Malta and Sicily), he left Fop behind with a servant called Nicolo, who travelled with Brønsted and Linkh in December 1811 to the island of Zea, where it seems the dog it was who died. "Pauvre Fope".

On his return to London Cockerell established his own prestigious architectural practice, specializing in the Greek Revivalist style. He became a member of the Royal Academy in 1829, and Professor of Architecture there in 1840. In 1848 he won the first Royal Gold Medal for architecture, and became the first professional president of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1860. He was buried in Saint Paul's Cathedral, next to Sir Cristopher Wren. |

|

Skye Terrier |

|

|

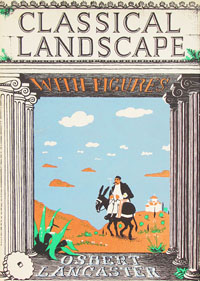

6. Osbert Lancaster, Classical Landscape with Figures. John Murray, London, 1947.

| |

Classical Landscape with Figures

by Osbert Lancaster

|

Sir Osbert Lancaster CBE (1908-1986), English cartoonist, stage designer, architectural historian, art critic, travel writer and dandy. He had a great affection for Greece, at least certain parts and aspects of it, and in Classical Landscape with Figures he presents fascinating sketches of the country, its people, history and particularly its art and architecture in an intelligent, witty and entertaining way. His atmospheric cartoon-style line drawings, some with flat colour washes, illustrate his narratives admirably, and today evoke the kind of nostalgia for a long-lost Greece as it was in the 1940s that the sketches and watercolours by the 19th century Grand Tourers did for the armchair travellers of Lancaster's generation.

Like his predecessors, his eye was mainly drawn to Classical and Byzantine edifices and ruins, and though he also diverted his attention to the modern and even more obscure epochs such as that of the medieval Frankish knights, he had little interest in Ottoman architecture and was generally of the opinion that the Turks contributed little to the country during 400 years of occupation. He does, however, mention in passing (and from a distance) his admiration for a couple of mosques. He is to be applauded for pointedly refusing to dismiss particular periods or styles as "degenerate", as many previous literary travellers had felt obliged to do.

His book contains several caveats and satirical criticisms concerning the Greek social, cultural and political landscape of his day. He even introduces a new word into the English language: "praxicopomatic", which he defines as being "from the adjectival form of the modern Greek word for coup d'etat, meaning liable to coups d'etat and used exclusively for generals and admirals". Although his neologism never seems to have caught on, it certainly indicates the prevalence of a phenomenon which he saw as symptomatic of Greece's political state: "In these circumstances the coup d'etat becomes an accepted constitutional device and is usually attended with far less bloodshed than a general election."

Lancaster's very British upper middle-class background coloured his judgement not only in aesthetic but also political matters. During the Second World War he was given a relatively cushy job in the press censorship bureau (did he have to censor cartoons or potentially subversive art criticism?), and in 1944 the Foreign Office sent him as a press attaché to the British Embassy in Athens – after the Germans had been driven out. Greek left-wing factions, whose resistance forces had fought the Axis occupiers and helped the allies open an extra front, expected to receive a lion's share in the post-war government. British prime minister Churchill and the United States (from 1945 under President Truman), fearing that Greece would become a communist state in the thrall of Stalin, were determined to keep them out of power, and left-wing demonstrations in Athens were brutally repressed. A violent uprising or "revolution" flared up, with left-wing partisans controlling parts of the city and fighting British paratroops backed by the Royal Air Force. The uprising was put down but led to a bloody civil war (1946-1949) and three decades of political oppression by the western-backed right-wing.

Lancaster made quite a point of his contempt of the left-wing, and this book contains passages condemning them, telling tales of the "bloodthirstiness" of "ruthless" Communist leaders, who he accuses of war atrocities. His is a very narrow, disingenuous or misinformed picture of events which took place during terrible, chaotic times, as the Greeks fought first the Germans, Italians and Bulgarians and then each other. It may be that a definitive – or at least satisfactorily unpartisan – political history of Greece during the mid 20th century has yet to be written; but it is clear that terrible atrocities were commited by both left and right wing forces during World War II and the Greek Civil War, to say nothing of the horrors inflicted by the Axis authorities, including reprisal massacres and the deportation and murder of Greek Jews. The Brtitish and Americans provided the right-wing coalition with superior armaments, including warplanes which used napalm as a weapon for the first time. Not exactly cricket, Mr Lancaster. When the left were defeated, many of those survivors who had not escaped into exile were imprisoned, tortured and executed. Such horrors, albeit on a lesser scale, continued until the collapse of the military junta in 1974. We shall never know, of course, whether the left-wing forces would have been any more humane or just had they been victorious.

Another odd note in Lancaster's book is his undisguised admiration of the pre-war fascist dictator General Ioannis Metaxas (1871-1941) who seized power in 1936 and died in 1941, just before the Germans invaded. Metaxas is mentioned seven times, while Themistocles and Alexander the Great only merit three references each, and Aristophanes, Praxiteles and Sophocles none at all. Two of these mentions concern the general's road building schemes, one of which, the road over the Pindos mountains from Kalambaka (here we are back at Meteora), he claimed "is probably the finest piece of engineering in Greece. Completed just before the war by General Metaxas, to whose skill and foresight in military matters not only Greece but all the united nations owe a debt which ideological fashion makes them cravenly loath to acknowldege..." Lancaster does not tell us whether the dictator made the trains run on time, or elaborate on what he calls "those totalitarian gestures which so excited the wrath of foreign anti-fascists", but does relate that he banned the hubble bubble because he considered it to be "un-Greek".

This catalogue of political incorrectness and the general tenor of this book makes one wonder why it was written and published at that particular time. Ostensibly it is a travel book written for educated British readers (the cosy Betjemanesque references to Bournemouth, Derbyshire and Wembley), who at the time of its publication in 1947, when post-war austerity in the United Kingdom meant money was tight and rationing and foreign currency restrictions were still in force, and the Hellenes were embroiled in a bitter civil war, were very unlikely to be able to visit Greece, "a country which", as Lancaster himself writes, "world events seem all too likely to put out of bounds for an indefinite period". There is more of a hint of propagandizing in this work, and although one cannot accuse him of being an official apologist for Churchill's foreign policy or the Truman Doctrine, despite his wartime functions, he does confess in his introduction that one of his motives in writing the book was: "... the presumptuous idea that as a great deal of nonsense, most of it ill-informed and much of it wilfully predjudiced, has recently been written about Greece, a fresh attempt to provide a picture, even one so personal and specialised as this, of a country with which, as the latest development of American foreign policy has forcefully demonstrated, our own future is so intimately bound up, might not be untimely".

Perhaps the kind of propaganda Lancaster was personally more interested in was the diffusion of optimism sorely sought after by Britons recovering from the trauma and privations of war. Most had never been beyond their island's shores, apart from on military or colonial service, and a country like Greece, familiar only from school books, museum visits and news media, was an exotic and distant planet. At the time of this book's publication, Lancaster had only spent 18 months in Greece, and that mainly in the company of Athenian politicians and officials (despite allusions to long nights slumming it in shady Piraeus bars frequented by musicians and prostitutes), but he was a shrewd observer, a quick learner, well-read and able to communicate with considerable charm and wit. His well-written and designed volume, with its splendid illustrations, helped make Greece for its readers into a real place, with real people, not merely a collection of outdoor ruins and Pausanian itineraries. It would have been just the medicine for a teacher in Tenby or a clerk in Clerkenwell dreaming of a three-egg omelette made with real eggs, a new non-utilitarian armchair or a peep at the Parthenon.

I am not entirely sure that I would get on well with Lancaster the man (or he with me), but Lancaster the writer and artist is a genial companion. Despite over 30 years trying to understand Greece and the Greeks, the results of his 18 months experience, distilled into 218 pages, still teach me much and constantly force me to reevaluate my judgements and refresh my outlook. Much is to be learned in these pages of Greece's past and present. Its future, as in Lancaster's time, remains at the mercy of greater powers beyond its borders. |

|

|

| |

A lounging lizard at Kalambaka railway station. |

Articles and photos by David John copyright © 2011

The Cheshire Cat Blog at My Favourite Planet Blogs

We welcome considerate responses to these articles

and all other content on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact.

The photos on this page are copyright protected.

Please do not use them without permission.

If you wish to use any of the photos for your website,

blog, project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr |

| |

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de |

| |

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr |

| |

| |

|