|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Niobe |

|

| |

The "Weeping Rock of Niobe" (Niobe Ağlayan Kaya) at the foot of Mount Sipylos (Sipil Daği),

on the outskirts of Magnesia ad Sypilum, Lydia, today Manisa, Turkey (see details below). |

| |

Niobe

Ancient Greek mythology, religion and art

Niobe (Νιόβη) was a daughter of Tanatalos (Τάνταλος), the semi-divine king of Sipylos (Σίπυλος), Lydia, and the wife of Amphion (Ἀμφίων), the semi-divine co-founder and king of Thebes. She had many children - the number differ in versions of the myth by various ancient authors (see below) - and taunted the nymph Leto (Λητώ) who only had two, the twins Apollo and Artemis by Zeus. In an act of vengeance on behalf of their enraged mother, Apollo and Artemis killed Niobe's children, usually referred to as the Niobids, by shooting them with arrows. Niobe returned home to Sipylos and wept an age for her loss, until Zeus put an end to her misery by turning to her into this rock. Amphion killed himself from grief after the death of his wife and children.

"Being blessed with children, Niobe said that she was more blessed with children than Latona [Leto]. Stung by the taunt, Latona incited Artemis and Apollo against them, and Artemis shot down the females in the house, and Apollo killed all the males together as they were hunting on Cithaeron... Niobe herself quitted Thebes and went to her father Tantalus at Sipylus, and there, on praying to Zeus, she was transformed into a stone, and tears flow night and day from the stone."

Apollodorus, The Library, Book 3, chapter 5. [1]

The 2nd century AD Greek travel writer Pausanias described the "Weeping Rock of Niobe" at the foot of Mount Sipylos (Sipil Daği), south of Magnesia ad Sypilum, Lydia (today the city of Manisa, Turkey).

"This Niobe I myself saw when I had gone up to Mount Sipylus. When you are near it is a beetling crag, with not the slightest resemblance to a woman, mourning or otherwise; but if you go further away you will think you see a woman in tears, with head bowed down." [2]

It seems that even in the time of Pausanias the rock appeared to be naturally-formed and weathered. If it was sculpted or decorated in prehistory, the marks of human intervention had long-since been eroded away. With a bit of imagination and some serious squinting, one can see the form of a seated woman with bowed head and empty lap. To the left of the figure is a small cleft or niche from which today a tree grows.

There is a local legend at Manisa that the rock weeps every Friday, a miracle this author failed to witness. He did notice, however, that locals come to a nearby spring to fill enormous plastic containers with the water, because, they say, it tastes excellent, and also because the tap water in the city is not drinkable. [3]

According to a fragment of a poem by Sappho, "Leto and Niobe were once bosom friends". [4] Little mention has been made of the family aspect of their close relationship and the blood feud that followed, not to mention the implications of incest. Both Niobe's father Tantalos and her husband Amphion were said to be sons of Zeus, thus she and her children were all grandchildren of the god. This also made Tantalos and Amphion half-brothers of Apollo and Artemis as children of Zeus, who according to Homer (see below) took Leto's side, and turned the local people to stone to prevent them from burying the slaughtered Niobids.

When discussing what ancient Greek poets had to say about the mythological history of Thebes, Pausanias commented that Amphion and a number of others also mocked Leto and her twins. He also alludes to the idea that the Niobids were not killed literally by arrows but were struck down by a plague, presumably sent by Apollo and Artemis.

"It is also said that Amphion is punished in Hades for being among those who made a mock of Leto and her children.

The punishment of Amphion is dealt with in the epic poem Minyad [Μινυάδος], which treats both of Amphion and also of Thamyris of Thrace. The houses of both Amphion and Zethus were visited by bereavement: Amphion's was left desolate by plague, and the son of Zethus was killed through some mistake or other of his mother." [5]

The theme of Apollo and Artemis shooting the Niobids was depicted many times by ancient Greek artists. Pausanias [see note 2] reported seeing an image of "Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe" in the cave of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos on the south slope of the Athens Acropolis. It is not clear whether this image was a painting, a relief or statue group. He also reported that the Thebans claimed that tombs near the Proetidian Gate of their city were those of the Niobids, and that even their funeral pyre and ashes were preserved nearby.

"Here too at Thebes are the tombs of the children of Amphion. The boys lie apart; the girls are buried by themselves. ... The pyre of the children of Amphion is about half a stade from the graves. The ashes from the pyre are still there." [see note 5] |

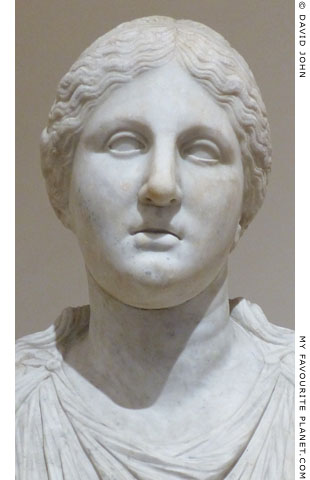

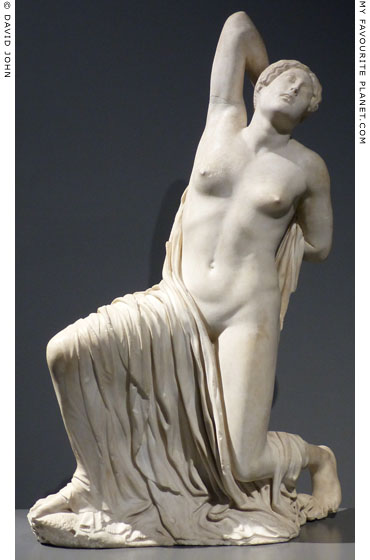

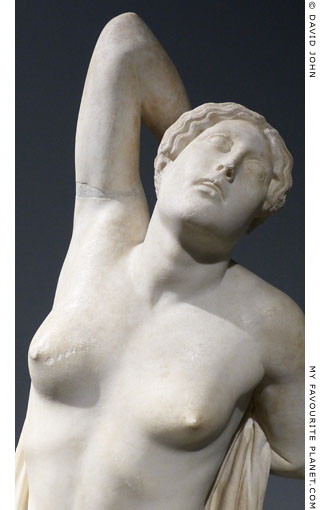

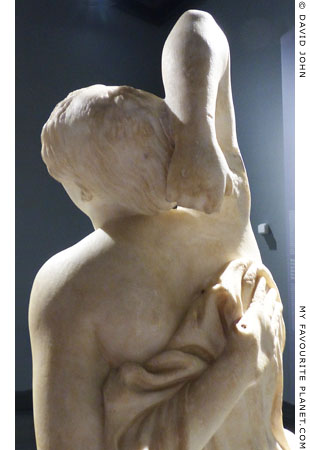

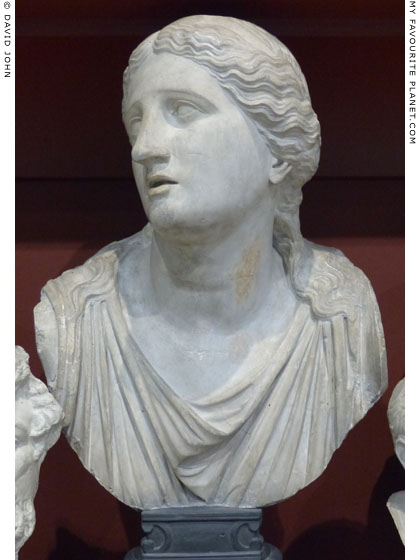

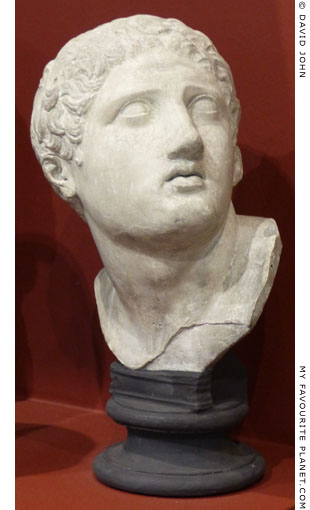

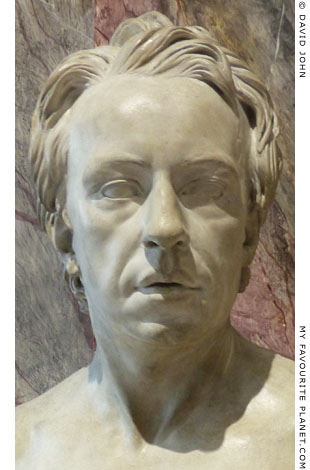

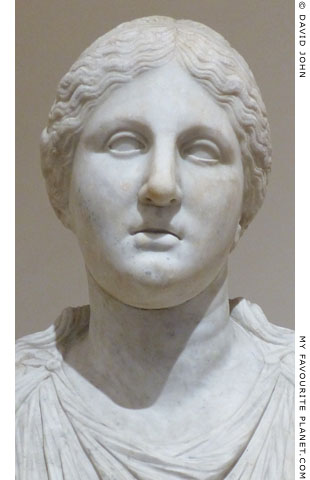

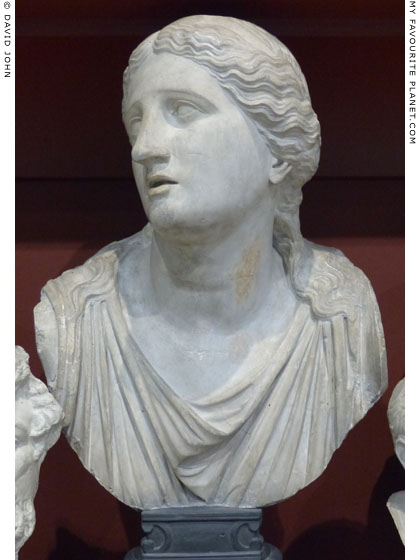

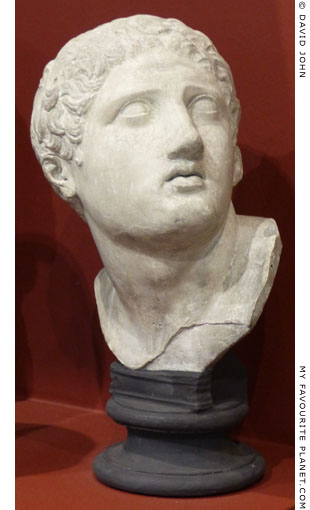

Marble head thought to represent Niobe,

later believed to be a copy of the Aphrodite

of Knidos by Praxiteles (4th century BC).

Roman period. Coarse-grained marble.

The bust is a modern addition.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of

Rome. Inv. No. 8586. Ludovisi Collection. |

| |

| |

How many children did Niobe have?

"A strange and indeed almost absurd variation is to be noted in the Greek poets as to the number of Niobe's children. For Homer says that she had six sons and six daughters; Euripides, seven of each; Sappho, nine; Bacchylides and Pindar, ten; while certain other writers have said that there were only three sons and three daughters."

Aulus Gellius (circa 125-180 AD), Attic Nights, Book 20, chapter 7. [6]

"The Ancients seem not to agree with one another concerning the number of the Children of Niobe. Homer says there were six sons and as many daughters; Lasos says twice seven; Hesiod nineteen, if those verses are Hesiod's, and not rather, as many others, falsely ascribed to him. Alkman reckons them ten, Mimnermos twenty, and Pindar as many."

Claudius Aelianus (circa 175-235 AD), Varia Historia, Book 12, chapter 36. [7]

It appears that in antiquity there was no standard or canonical version of the myth, and the question of the number of Niobe's children seems to be an obsure matter which bothers the minds of only a small number of academics. Interest in the question was rekindled following the discovery of ancient depictions of the slaughter of the Niobids by Apollo and Artemis since the 16th century. The famous "Uffizi Niobid Group" of statues (see below) was discovered in Rome in 1583, along with other statues which may or may not have been related to the group, and perhaps missing other lost sculptures which were part of the representation of the mythological tale. Historians have since asked how many Niobids were portrayed in such statue groups, which were perhaps copies of an original of the Classical or Hellenistic period.

Like many myths and legends, the story of Niobe was probably part of an oral tradition spread throughout the ancient Greek world, and several local versions, embellished by storytellers, poets and singers with details such as the number and names of the Niobids, may have been in circulation long before they were first written down from around the 8th - 7th century BC.

The earliest surviving mention of the Niobe and her children appeared in Homer's Iliad. The Greek hero Achilles has killed the Trojan prince Hector and taken the body to his camp. The grieving King Priam of Troy (Ilion) goes in disguise to Achilles' tent to ransom his son's corpse. Achilles agrees to the bargain and, as he invites Priam to dine with him, reminds him of the story of Niobe's twelve children in order to assuage his grief:

"Achilles then went back into the tent and took his place on the richly inlaid seat from which he had risen, by the wall that was at right angles to the one against which Priam was sitting.

'Sir,' he said, 'your son is now laid upon his bier and is ransomed according to desire. You shall look upon him when you take him away at daybreak. For the present let us prepare our supper. Even lovely Niobe had to think about eating, though her twelve children - six daughters and six lusty sons - had been all slain in her house.

Apollo killed the sons with arrows from his silver bow, to punish Niobe, and Artemis slew the daughters, because Niobe had vaunted herself against Leto. She said Leto had borne two children only, whereas she had herself borne many - whereon the two killed the many.

Nine days did they lie weltering, and there was none to bury them, for the son of Kronos [Zeus] turned the people into stone. But on the tenth day the gods in heaven themselves buried them, and Niobe then took food, being worn out with weeping.

They say that somewhere among the rocks on the mountain pastures of Sipylos, where the nymphs live that haunt the river Akheloos, there, they say, she lives in stone and still nurses the sorrows sent upon her by the hand of heaven.

Therefore, noble sir, let us two now take food. You can weep for your dear son hereafter as you are bearing him back to Ilion - and many a tear will he cost you.'"

Homer, The Iliad, Book 24, lines 595-620. At Perseus Digital Library.

It is not known how much the myths related by Homer are faithful recordings of older versions familiar to him, and how much he may have invented or embellished for narrative, literary or other reasons.

The poet Hesiod (Ἡσίοδος), thought to have lived around the same time as Homer, may also have mentioned Niobe's children. The passage by Aelian above may refer to the Catalogue of Women (Γυναικῶν Κατάλογος, Gynaikon Katalogos), a lost epic poem of mythological genealogies attributed to Hesiod, known only from papyrus fragments and references by other ancient authors.

The various names given to the Niobids first appear in works of the Roman period by Apollodorus and Ovid (43 BC - 17/18 AD), who names seven sons but none of the daughters [see note 1], Hyginus [8], Lactantius Placidus (circa 350-400 AD) and a scholiast (commentator) on Euripides. Some of the names in these lists have been associated with characters in other myths.

Two minor characters caught up in the tragic killing were the nurse (Trophos) and teacher (Pedagogue, see photo below) of the children, who are believed to have been depicted in sculpture groups of the slaughter, although it has been suggested that the figure identified as the Pedagogue may be Amphion, the Niobids' father. |

|

|

| |

Decorative marble roundel with a relief depicting Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe.

Roman, probably 1st century BC. From Italy. Diameter 94 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1887.7-21.1 (Sculpture 2200).

|

At the top Artemis (left) in a short chiton, and Apollo (right, kneeling), nude except for a himation, shoot arrows at the Niobids to avenge their mother Leto. The twin gods are depicted at a larger scale than their dying victims. It is thought that the many sculptures depicting this scene may have derived from a frieze which decorated the throne of the colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus made by the Athenian sculptor Pheidias for the god's temple at Olympia around 432 BC, which was described by Pausanias [9].

Some of the figures on the relief are comparable with surviving ancient statues of Niobids. For example, at the bottom of disc the pose of the figure holding on to a smaller figure is similar to that of the Uffizi statue of "Niobe and her youngest daughter" (see below). On the left edge of the disc, the pose of the male figure on one knee attempting to take an arrow from his back resembles those of the Uffizi statue of "a male Niobid on his knee" (see below) and the statue of the female Niobid from the Horti Sallustiani (see below).

Unfortunately, at the time this photo was taken the roundel was displayed in the shadow of a statue. |

|

|

| |

The Death of the Niobids, gold relief by Antonio Gentili (1519-1609). Gold sheet on a background

plate of lapis lazuli, decorated with carnelians. From a series of six mythological scenes

made in Rome around 1600, after models by Guglielmo della Porta, made 1552-1555.

Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 2911. |

| |

|

|

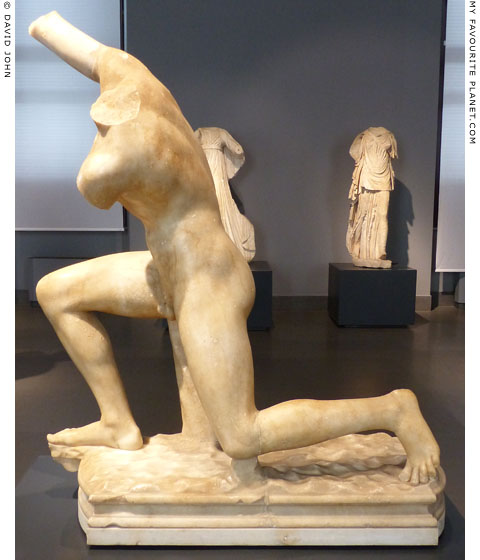

Marble statue of a dying female Niobid.

Parian marble. Circa 440-430 BC. Found in June 1906 on the Piazza Sallustio,

within the area of the ancient Horti Sallustiani (Gardens of Sallust),

on the Quirinal Hill, Rome. Height 149 cm.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 72274.

|

|

The young woman, one of Niobe's daughters, in obvious pain, falls on one knee and attempts to take out the arrow between her shoulders shot by Artemis. The sculpture originally included a bronze arrow and earrings.

This is one of three surviving statues, dated to around 440-430 BC, believed to be from the same group depicting the Niobids being killed by Apollo and Artemis, found in the area of the Horti Sallustiani, Rome (see also the statue fragment from the Horti Sallustiani below). The other two statues from the group, a Running Niobid and Lying Niobid, found with four or five other statues beneath a house at 3 Piazza Sallustiana in October 1886, are now in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. The statues from both finds had been deliberately hidden in underground passages in antiquity, possibly just before the sack of Rome by Alaric's Visigoths in 410 AD [10].

According to one theory, they may have decorated the pediment of the Temple of Apollo Daphnephoros at Eretria, Euboea. Some of the temple's sculptures were taken to Rome, probably during the reign of Augustus, and are thought to have been set up in the Horti Sallustiani, either in a building or the gardens themselves.

The American classical archaeologist and architectural historian William Bell Dinsmoor Jr. (1923-1988) argued that the three sculptures may have decorated the south pediment of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai in the Peloponnese (designed by Iktinos and built around 450-400 BC), and that they may have been looted from there by the Romans.

"No pedimental statues were ever found at Bassae, however, and we must conclude that they were carried off in ancient times, probably for the adornment of Rome."

"It so happens that a group of statues found at Rome, the Niobids of which two are now in Copenhagen and a third in the Terme Museum at Rome, would exactly fit the requirements of the temple at Bassae, so that we are probably to restore in its south pediment a scene representing the sons and daughters of Niobe slain by the invisible hands of Apollo and Artemis."

William Bell Dinsmoor, The architecture of Ancient Greece: An account of its historic development, page 159, and note 2. Biblo and Tannen Publishers, New York, 1950.

He had already written a more detailed argument in 1939:

William Bell Dinsmoor, The lost pedimental sculptures of Bassae. American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 43, No. 1 (January - March 1939), pages 27-47. At jstor. |

|

The back of the dying Niobid statue.

The small arrow hole can be seen

between her shoulders, just above

the top of the garment. |

|

| |

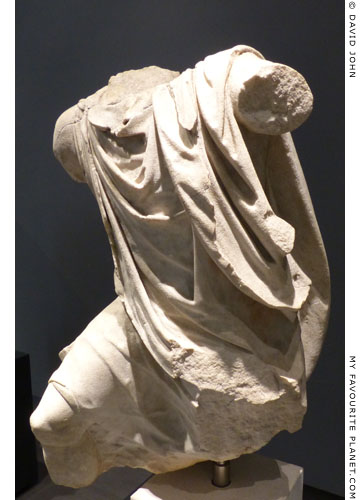

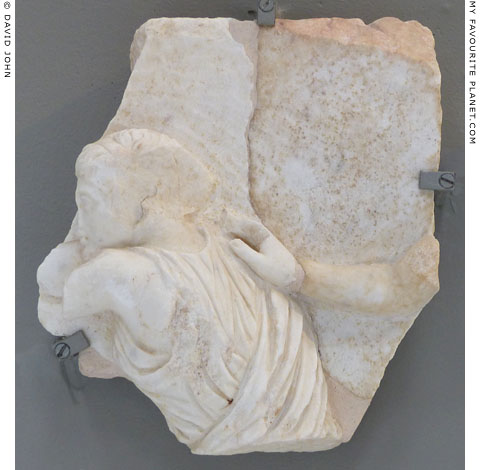

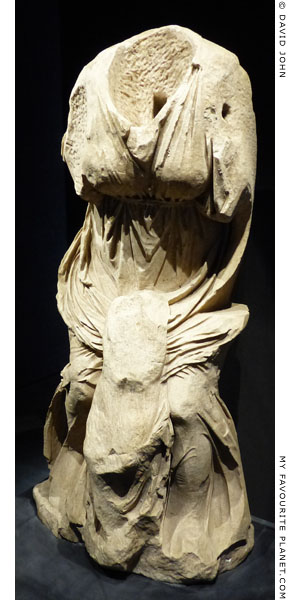

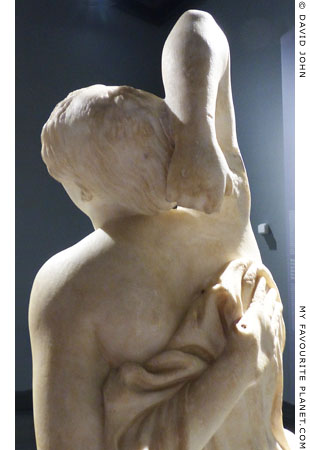

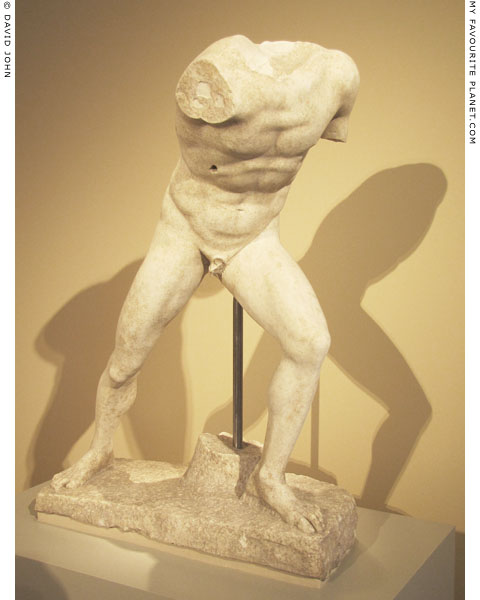

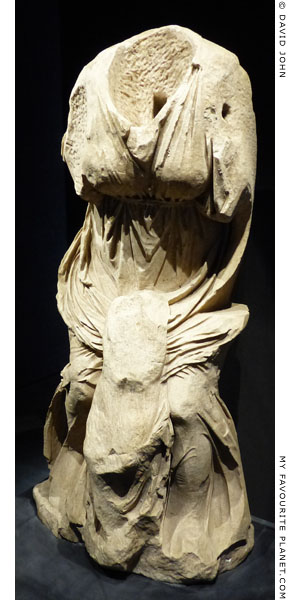

Torso of a marble statue thought

to depict the Niobids' pedagogue.

Late Hadrianic period (117-138 AD) copy of a Greek

original. Found in 1840 in the Horti Sallustiani, Rome,

in the area of the co-called Nympheum.

Identified as the pedagogue of Niobe's children from a statue group

of the massacre of the Niobids, by comparison with copies of the

same type. He attempts to save one of the male children by grabbing

him by the arm and pulling him to his body. It has been suggested

that the figure may be Amphion, the father of the Niobids.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 380382. |

| |

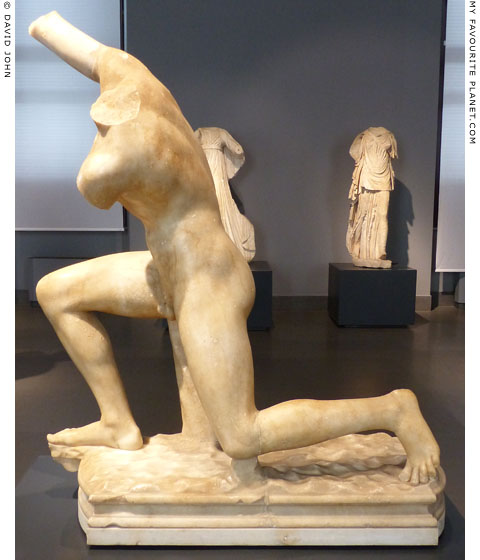

The so-called "Subiaco Ephebe" (or "Youth from Subiaco"), a marble

statue of a falling youth, perhaps depicting a fleeing or dying Niobid.

1st century AD, Roman Imperial period. Thought to be a copy of a late

Hellenistic bronze original of the 2nd century BC. Anatolian marble.

Discovered during excavations 1883-1884 by the Italian archaeologist

Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani (1845-1929) at the Villa di Nerone, Subiaco

(ancient Sublaqueum), near Rome [11].

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 1075. |

| |

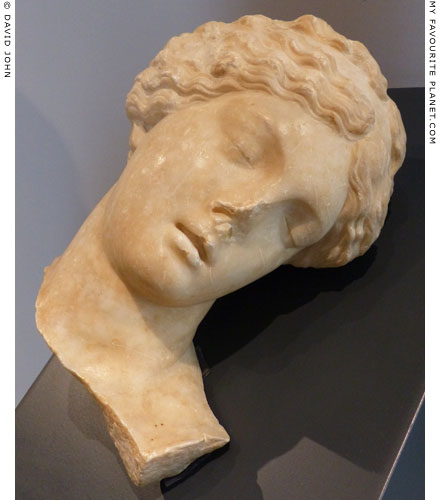

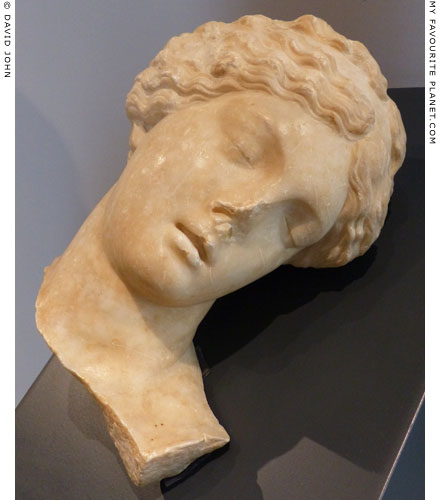

A marble head from a statue of a sleeping or dead girl, perhaps a Niobid.

Found at Subiaco together with the "Subiaco Ephebe" (see above).

1st century AD, Imperial period. Thought to be a copy of a late

Hellenistic bronze original of the 2nd century BC. Anatolian marble.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 1194. |

| |

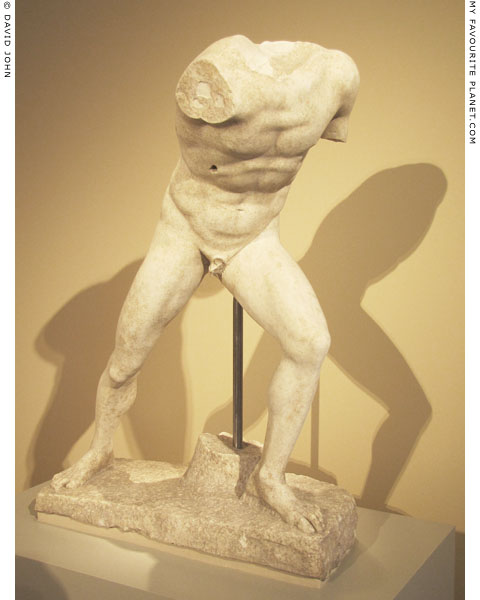

A marble statue of a wounded Niobid, the head and arms now missing.

The pose of the nude figure is similar to that of the "Elder male Niobid"

in the Uffizi Niobid group in Florence (see below). Identified as a Niobid

partly from the pose and the hole in the figure's right side, into which

it is thought a bronze arrow was inserted. Circa 440-430 BC. From Rome. Height 117.8 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1958.1.

Purchased in 1955 from the art dealer Barsanti, Rome, for 63,000 Deutschmarks

with funds from the Zahlenlotterie Berlin, and lent to the Berlin State Museums

(SMB). Donated to the the museum in 1958 by the Berlin state government. |

| |

The "Chiaramonti Niobid", a fragmentary marble

statue thought to depict a daughter of Niobe.

Named after the Chiaramonti Museum where

it was previously exhibited. Height 168 cm.

Gregoriano Profano Museum, Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 1035.

|

The "Chiaramonti Niobid" is usually described as being a Roman copy of an original of the late 4th or 3rd century BC, and probably discovered during the mid 16th century excavations at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, organized by Cardinal Ippolito d'Este (1509-1572). However, the Italian archaeologist Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani (1845-1929), who excavated Nero's Villa at Subiaco (ancient Sublaqueum, see above) and found the "Subiaco Ephebe" (see photo above), believed that the statue belonged to the same Niobid group as the sculptures from Subiaco, and that it had been found there during the pontificate of Pope Paul III (1534-1549):

"The falling youth, now in the Museo Nazionale alle Terme, is not the only specimen of the group placed by Nero in his villa at Sublaqueum. One of his sisters, now in the Museo Chiaramonti, was found in the same place in the time of Pope Paul III. Both statues, once standing on the same mass of rock, were most carefully detached from it in the time of Nero, who probably wanted to place them one by one in a symmetrical line against a triangular background of evergreen, imitating the shape of a pediment. This process of separation from the socket originally shared by the whole group of boys and girls, is quite noticeable in the plinth of the youth, where the right foot has been made to rest on a projecting bracket because a larger piece could not be cut away from the rock without damaging the nearest figure."

Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani, Wanderings in the Roman Campagna, pages 357-358. Constable & Co., London, and Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1909. At the Internet Archive.

The photo above is from page 357.

Written for popular consumption, the book contains few detailed accounts or footnotes and no bibliography, and Lanciani did not provide evidence or references to support his claims.

A more recent article, concerning the analysis of the types of marble used to make the Uffizi Niobid Group (see below), pointed out that the "Chiaramonti Niobid" is quite different to the other Niobid statues found at Hadrian's Villa:

"The most famous artifacts are the Niobids in white and bigio morato marble found in the Hadrian's Villa, where also another isolated example, the so-called Chiaramonti type now in the Vatican, had been discovered long before, suggesting the unlikely hypothesis that two separate copies might exist in the Villa (Diacciati, 2009, 200)."

Donato Attanasio, Chiara Boschi, Susanna Bracci, Emma Cantisani, Flavio Paolucci, The Greek and Asiatic marbles of the Florentine Niobids. Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 66, February 2016, pages 103-111. At researchgate.net.

The composition of the statue is similar to that of the "Nike of Paionios" (425-420 BC) and the "Winged Victory of Samothrace" (circa 220-185 BC); the striding pose of the figure, and the deep folds of the himation (cloak) and peplos (belted by a knotted cord just below the breasts) which cling to the body and legs due to wind or swift movement.

|

|

|

| |

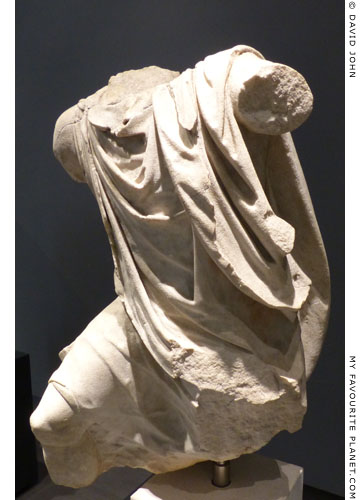

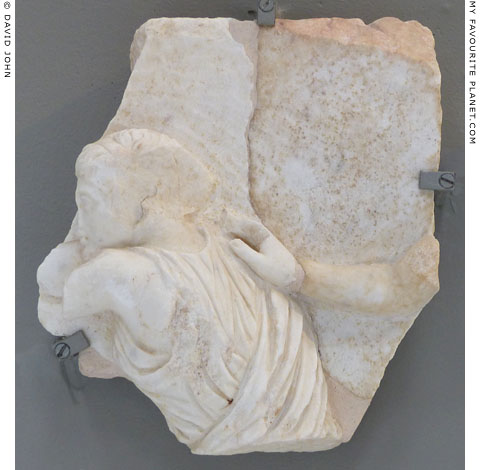

Two fragments of a marble relief panel depicting

the slaughter of the Niobids by Apollo and Artemis.

Antonine period, 2nd century AD. Pentelic marble. Excavated

1952-1954 at the Temple of Poseidon at Isthmia, Corinthia.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Slab 3, Figure 3.

Left fragment, Inv. No. IS 6, discovered in 1952.

Right fragment, Inv. No. IS 171, discovered in 1954.

|

Two series of marble panels with reliefs depicting the myths of the Kalydonian Boar hunt and the slaughter of the Niobids decorated the base on which colossal marble statues of Poseidon and Amphitrite stood. The three-times larger than lifesize statues, probably made by Attic sculptors, depicted Poseidon, the patron deity of Isthmia, standing, with his consort Amphitrite enthroned to his right. Only fragments of the statues and panels have survived, and the Isthmia museum exhibits Amphitrite's torso, two parts of the Niobid reliefs (see the other below) and one of the hunt relief.

It is thought that the subject matter of the reliefs was meant to warn the athletes participating in the pan-Hellenic Isthmian games against cheating and excessive pride (hubris).

According to the museum reconstruction drawings, the fragments above show part of the figure of Artemis shooting an arrow. However, the figure in the second part (see photo below) is more difficult to identify. It depicts the head (in profile), shoulders and part of the raised right arm of an apparently bearded man with short hair, who in the reconstruction drawing holds a weapon (a sword or club). In other depictions of the Niobids scene only Apollo and Artemis are shown taking part in the slaughter, while the Niobids themselves are passive victims who do not defend themselves. This figure is evidently not Apollo, so who then? Perhaps he belongs to the Kalydonian Boar hunt reliefs. A relief of the hunt on a marble sarcophagus panel (150-250 AD) in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Inv. No. AD 1947.278) depicts a similar figure, identified as Meleager, in exactly this pose (see photos on the Dioskouroi page).

The fragmentary part of the hunt relief in the Isthmia museum appears to depict Artemis (or Atalanta?) drawing her bow, unusually with Hermes (with a petasos hat) to the left of her.

The statue group may have been replaced in the mid 2nd century AD by a chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue group featuring Poseidon and Amphitrite in a chariot. This group was described by Pausanias, who wrote that it was dedicated by Herodes Atticus, and that "among the reliefs on the base of the statue of Poseidon are the sons of Tyndareus [the Dioskouroi]". (See the Herodes Atticus page for further details.) |

|

|

| |

The second fragmentary relief panel of the slaughter of the Niobids (?)

in the Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Slab 5, Figure 5.

This part is displayed in the museum to the right of the one above.

Photos of both parts are at approximately the same scale. |

| |

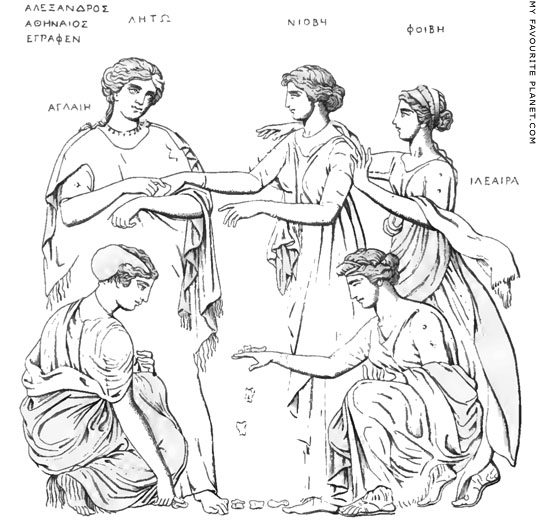

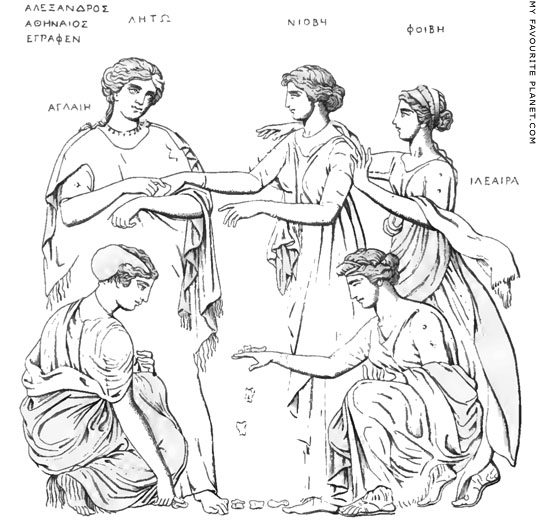

Engraving of a painting depicting Niobe among a group of female mythological

figures, with their names inscribed in Greek: Leto (Λητώ), Niobe (Νιόβη) and

Phoebe (Φοίβη) standing, and Aglaia (Ἀγλαΐα) and Hilaeira (Ιλάειρα) kneeling

and playing knucklebones (ἀστράγαλοι, astragaloi).

Monochrome painting in red on a white marble plaque. From Herculaneum.

1st century BC - 1st century AD, in the style of 5th century BC.

Height 45.7 cm, width 38.1 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 9562.

|

The painting, made with a type of red chalk and touches of colour, is signed ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ ΕΓΡΑΦΕΝ (Alexandros Athenaios egraphen, Alexander of Athens drew this) in the top left corner.

It was found on 24th May 1746 in a house in Herculaneum, along with four other marble slabs, thought to have been painted by another artist or artists. The paintings on the other slabs: a young man fighting a Centaur; a scene from a tragedy; a Dionysian scene; a quadriga (four-horse chariot).

Some early publications named the painting "Niobide Giocatrici di astragali" (Niobids playing dice astragali) and even "the five daughters of Niobe". The scene has also been described as Phoebe (the Shining one) attempting to pacify Leto and Niobe, while Aglaia (the Bright one) and Hilaeira (the Merry one), two of the Niobids, play knucklebones, unaware of their imminent fate. Phoebe has been identified as Artemis, the female form of Apollo's epiphet Phoebos, but the names Aglaia and Hilaeira, known from other mythological contexts, are not mentioned by ancient authors as daughters of Niobe or in connection with the story of the Niobids. (See the note on Hilaeira and Phoebe, the Leucippides, on the Dioskouroi page.)

According to a fragment of a poem by Sappho, "Leto and Niobe were once bosom friends" [see note 4], and the scene may depict a happier time before the two friends fell out.

Source: Domeniconi Monaco, Specimens from the Naples Museum, Plate 22. William Clowes and Sons, London, 1884. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

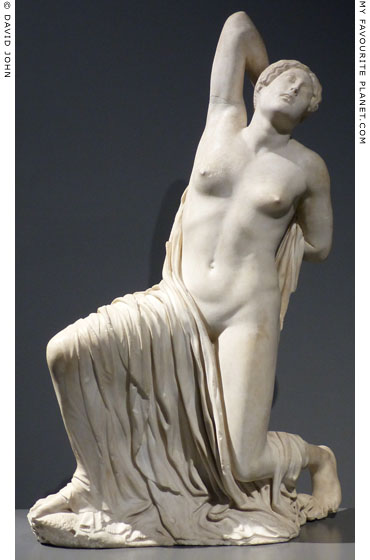

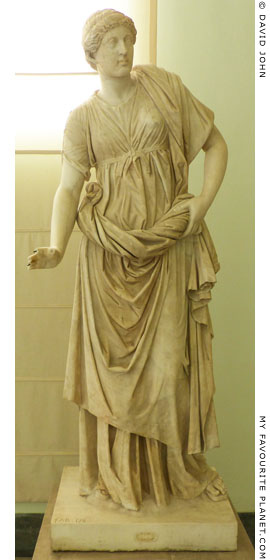

A plaster cast of a bust of Niobe [12], taken from the marble

statue "Niobe and her youngest daughter" (see photo below)

from the Uffizi Niobid Group in Florence.

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. ASN 4720.

From the plaster cast collection of Anton Raphael Mengs [13]. |

| |

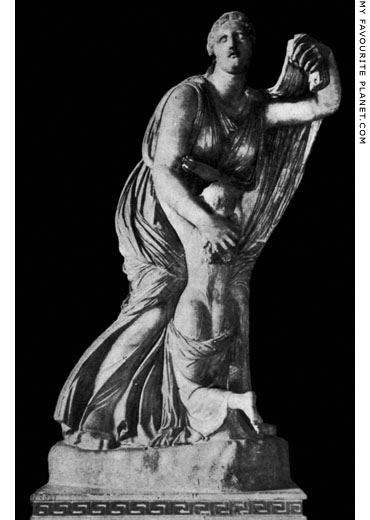

The marble statue of "Niobe and her youngest daughter" (photo, right) depicts Niobe holding one of her daughters in an attempt to protect her from the deadly arrows of Apollo and Artemis. It is believed to have stood in the centre of an ancient statue group showing the dramatic death of Niobe's children, known as the Uffizi Niobid Group, since 1779 exhibited in the Sala della Niobe (Hall of Niobe or Niobe’s Room) in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Fourteen ancient statues were found in March or April 1583 in the Vigna Tommasini, a vineyard outside the Porta San Giovanni, Rome, in the area which had been part of one of the imperial gardens, either the ancient Horti Lamiani or Horti Maecenatis. Around eleven of the works discovered are thought to have belonged to the original group depicting the Niobids. The sculptures were purchased the same year by Cardinal Ferdinando de Medici (1549-1609; from 1587 Grand Duke of Tuscany), who had them restored and set up in the garden of the Villa Medici, Rome. In 1588 he sent casts to Florence.

The statues in the Medici garden, particularly that of Niobe, were admired by the 18th century traveller James "Athenian" Stuart (1713-1788):

"... among the excellent sculptures in the Medicean gardens at Rome, there is a celebrated statue of Niobe, the attitude and countenance of which are wonderfully expressive of her anguish at the sight of her slaughtered children, and her apprehensions for those who survive." [14]

The statues were later purchased by Peter Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1747-1792, from 1790 Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II), who had most of them moved from Rome to Livorno in 1769, where they were again restored by Innocenzo Spinazzi between 1770 and 1776 when they were taken to Florence. The remaining four statues were taken from the Villa Medici to Florence in 1778. In 1779 the entire group were arranged in the Sala della Niobe, the room especially designed for them by the architect Gaspare Maria Paoletti.

For many years there has been debate over which of the statues now in the Uffizi were part of the Vigna Tommasini find, and which actually represent Niobids. No detailed list was made of the fourteen Vigna Tommasini statues, and contemporary sources appear to indicate that "Niobe and her youngest daughter" and a statue of two wrestlers (see below) were each counted as two sculptures. According to Ovid [see note 1], Niobe had seven sons and seven daughters, and so with Niobe and the pedagogue there ought to be sixteen figures. Ferdinando de Medici added non-related statues from the Medici collection, including a horse (see below), to complete the set displayed in his garden. On arrival in the Uffizi other non-related but better-preserved statues were exhibited to complete the group in place of some of the Vigna Tommasini statues.

It is currently considered that of the eighteen "Niobids" in the Uffizi, ten are from the Vigna Tommasini, four are "doubles", including a so-called "Psyche", and four are non-related statues resembling or restored as Niobids: a "Selene" (the so-called "Trophos", τροφός, nurse), the so-called "Narkissos" and two "Muses" (see for example the photo below, right). Another "Psyche", now in the Bardini Museum, Florence, was suggested as the eleventh statue from the Vigna Tommasini group in the late 20th century.

Usually described as being made of Pentelic marble, recent analysis has shown that only six of the ten Uffizi Niobid statues from the Vigna Tommasini are made of marble from Mount Penteli, the other four being of Anatolian marble from the vicinty of Aphrodisias [15].

Since their discovery various theories have proposed that the statues are either Roman period copies, perhaps from the reign of Nero (54-68 AD), or Hellenistic Greek originals of the 4th or 3rd century BC, based on Classical models. It has even been suggested that Paionios of Mende, Skopas or Praxiteles may have sculpted the originals. They are thought to have been made for the pediment of a temple or to have decorated a nymphaeum (ornamental fountain) in a way similar to the Niobid group found at Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli. The third possibility is that they were originally pedimental sculptures later placed in a nymphaeum in the Horti Lamiani or Horti Maecenatis. A semi-circular structure discovered in the 19th century nearby, in the area of the modern Piazza Dante, may have been such a nymphaeum.

Other possibilities which have been considered include theories that such statue groups of dying Niobids were based on reliefs or paintings.

One theory, once widely accepted but now rejected by many sholars, is that the group was brought to Rome from Cilicia in southern Anatolia (Asia Minor) around 38 BC by the Roman general and politician Gaius Sosius, and placed in the Temple of Apollo Sosias. This theory is based on a remark by Pliny the Elder:

"With reference, too, to the Dying Children of Niobe, in the Temple of the Sosian Apollo, there is an equal degree of uncertainty, whether it is the work of Scopas or of Praxiteles."

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

The connection with Praxiteles appears to be strengthened by a short epigram by the Roman poet Ausonius:

"I once was Niobe, and fill'd a throne,

Till fate severe transform'd me into stone:

Behold the change which mimic art can give!

From stone Praxiteles has made me live." [16]

As with many attempts by modern scholars to associate surviving artworks with such brief, often vague reports by ancient authors, the theory led to the statues being given a conjectural history. According to this story, the statues were commissioned by Seleukos I Nikator (Σέλευκος Α΄ Νικάτωρ, circa 358 - 281 BC), one of the generals and successors (Diadochi) of Alexander the Great and founder of the Seleucid dynasty, and set up in Seleukia (Σελεύκεια; Latin, Seleucia ad Calycadnum, today Silifke, Turkey) in Cilicia, one of a number of cities he named after himself. Gaius Sosius, who was appointed quastor (governor) of Syria and Cilicia by Mark Antony in 38 BC, had the statues shipped to Rome. Following his return to Rome he placed them in the Temple of Apollo Medicus in the Campus Martius, next to the Theatre of Marcellus and the Porticus Octaviae, which he began rebuilding around 34 BC, and which was later named the Temple of Apollo Sosias after him.

The 19th century English architect and archaeologist Charles Robert Cockerell, who studied the Uffizi Niobid Group in 1816, believed that the statues were those mentioned by Pliny, and that they were Greek originals from the pediment of a temple (see below).

Since 1583, several similar statues and groups have been discovered, most in the vicinity of Rome, including a group of seven sculptures found at the villa of Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus in 2012 [17]. Two marble statuettes, one of Niobe and her youngest daughter, a smaller version of the Uffizi statue, and the other of Artemis with a bow, perhaps from a group, were discovered at Tsoutsouros, Crete in 1929 [18]. It now appears that the story of the slaughter of the Niobids was represented in several artworks from the time of Augustus, and that the theme was revived during the reign of Hadrian. These works may have been based on a common original which is as yet unknown.

In September 1800 two of the statues, a daughter and lying son (see below), were shipped to Palermo along with other artworks from the Uffizi in order to avoid their seizure by Napoleon's troops. They were returned to Florence in February 1803.

On 27 May 1993 a powerful car bomb planted by the Sicilian Mafia exploded on the Via dei Georgofili, behind the Uffizi, killing six people and wounding twenty six. The bomb also destroyed three artworks in the Uffizi and severely damaged thirty others, including the frescoes and sculptures in the Sala della Niobe. The "Niobe and her youngest daughter" had to be removed for restoration, and was finally put back on display in 2006.

Statues of the Uffizi Niobe Group

The 10 Niobids from the Vigna Tommasini:

• Niobe and her youngest daughter. Inv. No. 294.

• Elder male Niobid. Inv. No. 302.

• Younger male Niobid. Inv. No. 292.

• Fleeing female Niobid. Inv. No. 293.

• Fleeing female Niobid, Chiaramonti type. Inv. No. 300.

• Dying male Niobid. Inv. No. 298.

• Male Niobid on his knee. Inv. No. 289.

• Male Niobid climbing a rock (or second Niobid). Inv. No. 13864.

• Male Niobid climbing a rock (or third Niobid). Inv. No. 306.

• Pedagogue. Inv. No. 301.

(The 11th statue, "Psyche", is in the Bardini Museum, Florence.)

4 doubles:

• Male Niobid on his knee. Inv. No. 290.

• Male Niobid climbing a rock (or second Niobid). Inv. No. 304.

• Male Niobid climbing a rock (or third Niobid). Inv. No. 291.

• "Psyche in torment". Inv. No. 305.

4 added Niobids:

• Muse restored as a Niobid. Inv. No. 297.

• Muse, so-called "Anchyrroe" (a water nymph). Inv. No. 303. Acquired by Ferdinando de Medici in 1582 with the della Valle Collection of Cardinal Andrea della Valle (1463-1534).

• So-called "Narkissos" (or "Narcissus"). Inv. No. 299. Perhaps a Niobid, with a modern head. Added to the group at the suggestion of Thorvaldsen (see below).

• "Selene", so-called "Trophos" (Nurse). Inv. No. 296. Known before 1583, unknown provenance.

The rearing horse in the Uffizi, Inv. No. 69, was found near Magliana, southwest of Rome. 1st century BC. Pentelic marble. Height 270 cm. It was added to the Niobid group at the Villa Medici in 1588 because Ovid wrote that the killing occurred on a plain outside the walls of Thebes, where the older sons of Niobe were riding "steeds emblazoned with bright dyes and harness rich with studded gold" (Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 6, lines 221-224).

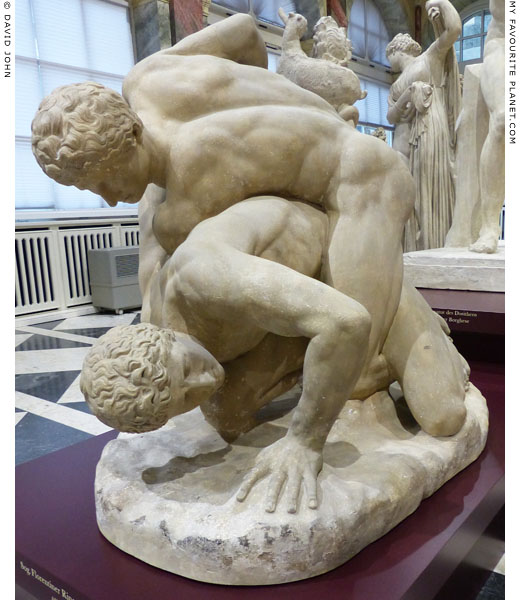

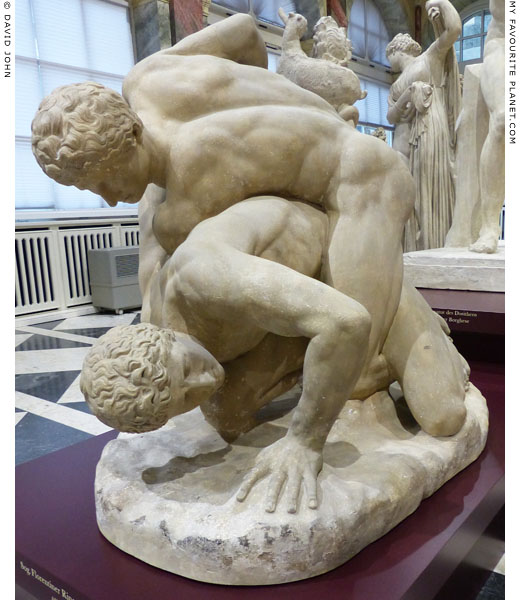

The statue of two wrestlers, the "Uffizi Wrestlers" or "Pancrastinae" (see photo below), made of Parian marble and dated to the 1st century AD, was part of the Vigna Tommasini find but not considered to be part of the Niobid group, and is exhibited in the Tribuna of the Uffizi, Inv. No. 216. Height 89 cm. However, Ovid wrote that two of the male Niobids, Phaedimus, and Tantalus, who had also been horse-riding, were wrestling when the slaughter began: "And while those brothers struggled - breast to breast - another arrow, hurtling from the sky, pierced them together, just as they were clinched..." (Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 6, lines 241-256). |

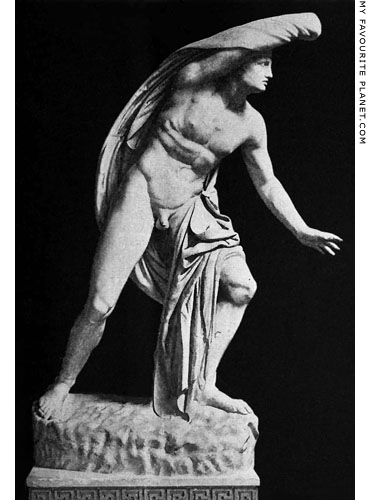

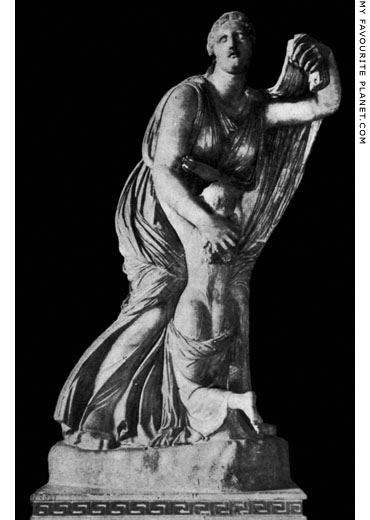

"Niobe and her youngest daughter", considered

to be the central statue of the Uffizi Niobid Group.

Docimium marble from west-central

Anatolia [see note 15]. Height 228 cm.

Sala della Niobe (Hall of Niobe), Uffizi Gallery,

Florence. Inv. No. 294.

Image source: Edmund von Mach (editor), Greek

and Roman sculpture; 500 plates to accompany

a handbook, Plate A 220. University prints, Series A,

Boston, Mass., 1916. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

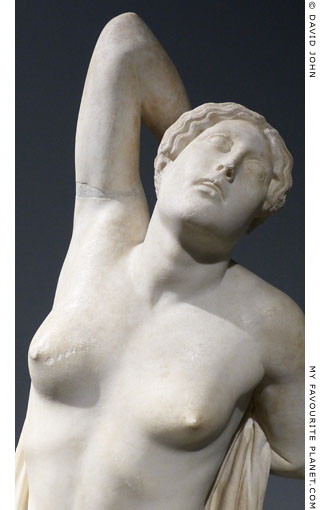

Part of a marble statue thought to depict Niobe

and her mortally wounded youngest daughter.

The figures are very similar to those from

the Uffizi Niobid Group above, and may also

have been part of a large statue group.

2nd century AD. Believed to be a Roman period

copy of a Hellenistic original. Pentelic marble.

Discovered by the Italian archaeologist Carmen

Lalli in April 2005, during excavations at the

Grande Nymphaeum in the archaeological site

of the Villa dei Quintili on the Via Appia

Antica, south of Rome.

The "Nieborów Niobe" bust was also found

at the Villa dei Quintili [see note 12].

Antiquarium, Villa dei Quitili, Via Appia Antica,

Rome. Inv. No. 508491.

Exhibited in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome, during the temporary

exhibition Archaeology&ME: pensare l'archeologia

nell'Europa contemporanea (Archaeology&ME:

Looking at archaeology in contemporary Europe),

10 December 2016 - 23 April 2017.

See: Rita Paris, Barbara Pettinau, Dalla scenografia

alla decorazione: La statua di Niobe nella Villa

dei Quintili sulla via Appia, in Mitteilungen des

Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische

Abteilung, Volume 113 (2007), pages 471-483. |

| |

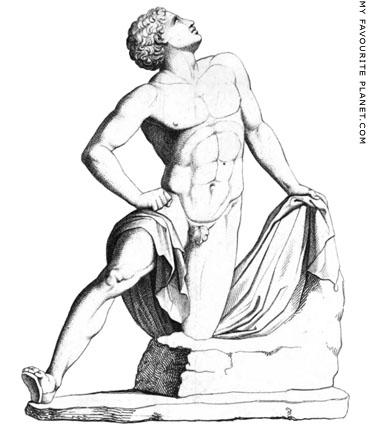

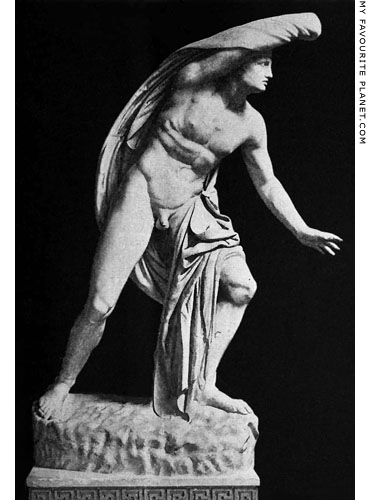

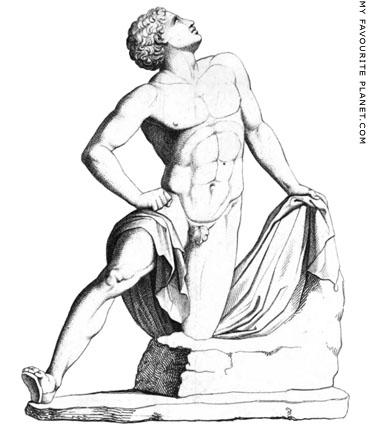

The marble statue of the "Elder male Niobid"

of the Uffizi Niobid Group. The naked young man,

slightly crouched, raises his right arm, covered by

part of his himation (cloak), in a futile attempt to

shield himself from the arrows of the twin gods.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Inv. No. 302.

Source: Ernest Arthur Gardner, A Handbook of

Greek Sculptures Part 2, Fig. 105, page 425.

Macmillan, London, 1897. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

| |

Plaster cast of the head of a male Niobid.

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden.

Inv. No. ASN 1985. From the plaster cast

collection of Anton Raphael Mengs.

Cast from the marble statue of a son of Niobe

resting on one knee (see image below), one

of the Uffizi Niobid Group found in 1583 in the

Vigna Tommasini, Rome. Docimium marble from

Anatolia [see note 15]. Sala della Niobe, Uffizi

Gallery, Florence. Inv. No. ASN 289. |

|

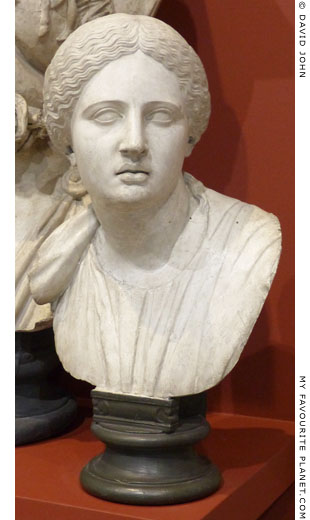

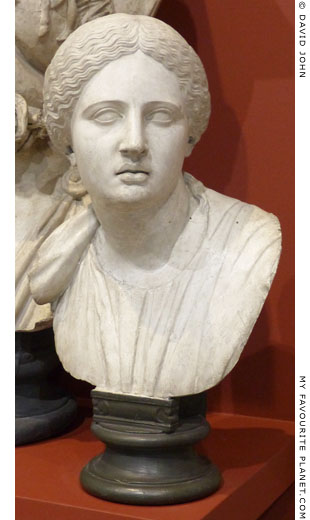

Plaster cast of a bust of a "daughter of Niobe".

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden.

Inv. No. ASN 2451. From the plaster

cast collection of Anton Raphael Mengs.

A cast of a marble statue of a muse restored

as a female Niobid, and exhibited as part of

the Uffizi Niobe Group. Height 186.5 cm.

Sala della Niobe, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Inv. No. ASN 297. |

|

| |

Plaster cast of the "Uffizi Wrestlers" or "Pancrastinae" in Dresden.

It is thought that the sport depicted may not be wrestling but the pankration

(παγκράτιον, all power or all force), an all-in, no-holds-barred, mixture of boxing

and wrestling, in which only biting and gouging out an opponent's eyes were

forbidden. [19] The right arm of the upper athlete is raised and his fist clenched

(not visible in photo), suggesting he about to thump his opponent.

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. ASN 2517.

The original, made of Parian marble in the 1st century AD, was found

in 1583 with the Uffizi Niobid Group in the Vigna Tommasini, Rome,

and is exhibited in the Tribuna of the Uffizi, Florence. Inv. No. 216.

Height 95 cm, width 115 cm, depth 76 cm. |

| |

Casts of the Uffizi Niobid Group exhibited in the Glyptothek, Munich at the end of the 19th century.

Both the Neues Museum, Berlin, and the Dresden Albertinum museum also had a "Niobid Room"

dedicated to casts of the group [see note 13], although arranged in a different orders.

Source: Ernest H. Short, A history of sculpture, page 136.

William Heinemann, London, 1907. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Cockerell's conjectural reconstruction of the Uffizi Niobid Group on a pediment of a temple.

Etching from a drawing by Charles Robert Cockerell in 1816,

on the page of a pamphlet, 52.6 x 60 cm, with a handwritten

dedication by Cockerell to the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen.

The Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen. Inv. No. E1461.

Public domain image, courtesy of the Thorvaldsen Museum.

Source: thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/collections/work/E1461 |

| |

The English architect and archaeologist Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863) stayed in Italy 1815-1817 on his way back to England, on the last leg of his seven-year Grand Tour around the Mediterranean. In Rome he was feted by intellectuals and the elite for his adventurous and pioneering voyages, exploring ancient sites in Greece, Turkey, Sicily and southern Italy, and his excavations of the temples at Aegina and Bassai.

In 1812 Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria (King Ludwig I of Bavaria from 1825) had purchased the pedimental sculptures taken by Cockerell and his companions from the Aegina temple (the "Aegina Marbles") [20], and commissioned the Danish neo-classicist sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), who had lived in Rome since 1797, to restore them. Cockerell worked in Thorvaldsen's studio on his reconstruction of the pediments.

In 1816 he travelled from Rome to Florence and visited the Uffizi with Jakob Ludwig Salomon Bartholdy (1779-1825), the Prussian Consul-General in Rome, who suggested that the Uffizi Niobid Group may have been from a temple pediment.

Working from this suggestion, and believing that the statues were those mentioned by Pliny (see above), and that they were Greek originals, Cockerell studied and drew the sculptures, and made drawings reconstructing their appearance on such a pediment. In 1816 he produced a pamphlet with etchings of two of the drawings and a brief account in Italian of his hypothesis, and dedicated the copy above to Thorvaldsen. The idea was accepted by many at the time, including the president and members of the Florentine Academy, who elected him as a member. He went on to produce a book in Italian on the Uffizi Niobid Group with another reconstruction of the pediment and drawings of seventeen individual sculptures, including the horse. The first of several editions was published in Pisa in 1818.

See: Charles Robert Cockerell, Le statue della favola di Niobe della Imp. e R. Galleria di Firenze. Presso Niccoló Capurro, Pisa, 1821. At the Internet Archive.

The British Museum also has a copy of the pamphlet etching, Inv. No. 2012,5001.637, although it is not on display and as yet there is no photo of it on their website.

See: britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/...

Another reconstruction drawing of the conjectural pediment was made in 1817 by the German artist Johann Heinrich Wolff (1792-1869), who collaborated with Cockerell on the project. A copy on transparent paper is now in the Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel. Inv. No. L GS 15112.

See: architekturzeichnungen.museum-kassel.de/8987/ |

|

A drawing by Cockerell the statue of "a male Niobid

on his knee" from the Uffizi Niobid Group [21].

Docimium marble from Phrygia, west-central

Anatolia [see note 15]. Height 124 cm.

Sala della Niobe (Niobe’s Room), Uffizi Gallery,

Florence. Inv. No. 289.

Source: Charles Robert Cockerell, Le statue della

favola di Niobe della Imp. e R. Galleria di Firenze,

Tavola IV. Presso Niccoló Capurro, Pisa, 1821. |

|

| |

The "Lying Niobid" or "Dying Niobid", a marble statue of a recumbent male Niobid lying on a cloak.

1st - 2nd century AD, after a model of around 320 BC. Pentelic marble.

Height 47.5 cm, width 45.5 cm, length (with restored parts) 177 cm.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 124.

Purchased in 1728 from the Albani Collection.

Currently (2023) displayed in the "Gläsernes Depot" along

with several ancient sculptures and modern copies.

|

The statue has been restored, with the addition of the missing right forearm and hand, the left leg below the knee and the right leg below the upper thigh.

There are several extant ancient statues and fragments believed to be depictions of dying male Niobids lying on their backs, two of which are similar in composition to this one, with the figure's right arm bent and the hand on the head, and left hand resting on the stomach just below the chest:

Dying male Niobid from the Vigna Tommasini find, part of the Uffizi Niobid Group (see above).

Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Inv. No. 298. Length 185 cm. Restored in 1994.

Dying male Niobid in the Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 269 (see photo below).

The Dresden State Art Collections (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, SKD) also have a plaster cast of another ancient version of this statue type. Inv. No. ASN 2726. |

|

| |

The "Dying Niobid" marble statue in Munich.

1st or 2nd century AD. Perhaps Parian Marble. Length 156 cm.

Known to have been in the Casa Maffei, Rome, in 1514. Taken with other antiquities before

1540 by Graf Mario Bevilacqua to the Palazzo Bevilacqua, Verona, where it was seen by

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. In 1811 it was purchased by the painter Johann Georg von Dillis

on behalf of Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria (King Ludwig I from 1825) and taken to Munich.

Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 269.

Image source: Edmund von Mach (editor), Greek and Roman sculpture; 500 plates to accompany

a handbook, Plate A 223. University prints, Series A, Boston, Mass., 1916. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

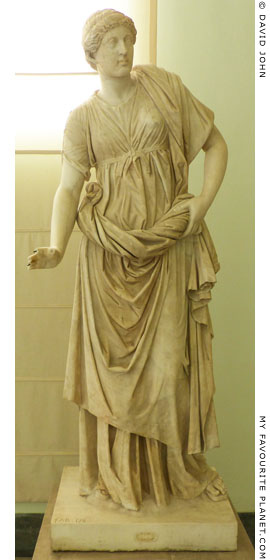

Marble statue of a female figure,

the so-called Niobid.

2nd century AD, Roman period copy of a late

3rd century BC Greek original. Height 150 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6391. From the Farnese Collection.

|

"248 (6391). Female statue, to which a head with modern neck has been added. The arms are restored. The girl, clad in chiton and himation is stooping slightly as she walks and bends her head back as if to watch something that threatens her from above. She is therefore designated as a Niobid or as the nurse of the Niobids, but the motive frequently recurs in ancient art. The figure seems originally to have represented a Danaid going to the fountain or a Dancing Muse, and is derived from a work of the Hellenistic period."

Giulio De Petra and others (editors), Illustrated guide to the National Museum in Naples: sanctioned by the Ministry of Education, page 30, No. 248 (6391). Richter & Co., Naples, 1897 (?). At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

| Niobe |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Apollodorus on the Niobe myth

Apollodorus, The Library, Book 3, chapter 5, section 6. English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, in 2 Volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd., London, 1921. At Perseus Digital Library.

For further information about Apollodorus (or Pseudo-Apollodorus) see note in Medusa part 1.

Mount Cithaeron (Κιθαιρών, Kithairon) is a mountain range in central Greece which forms a boundary between Attica and Boeotia, with Thebes to its north.

The myth of Niobe was also related by Ovid (43 BC - 17/18 AD):

P. Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses, Book 6, lines 146-312. Edited by Brookes More. Cornhill Publishing Co., Boston, 1922. At Perseus Digital Library.

2. Pausanias on the "Weeping Rock of Niobe" and the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book I, Chapter 21, section 3. English translation by W.H.S. Jones and H.A. Ormerod, in 4 Volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, London, 1918. At Perseus Digital Library.

Some scholars believe Pausanias may have come from Magnesia ad Sypilum (today Manisa, Turkey), the home of Tantalos and Niobe, as his references to this area are so detailed.

3. Niobe's spring

For further information about drinking water in Turkish cites,

see Ionian Spring Part 1 at The Cheshire Cat Blog.

4. Sappho on Leto and Niobe

"Λάτω καὶ Νιόβα μάλα μὲν φίλαι ἦσαν ἔταιραι"

Sappho (Ψάπφω, circa 630-570 BC), Fragment 142.

"ἔταιραι" (hetairai), in this context, has been translated as "dearest friends", "bosom friends", "the most devoted of friends", and "zärtlich befreundet" (German, tenderly befriended).

5. Pausanias on Amphion and the Niobids at Thebes

Amphion, Leto and the plague:

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 5, sections 8-9. At Perseus Digital Library.

The tombs and funeral pyre of the Niobids at Thebes:

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 16, section 7 and chapter 17, section 2.

6. Aulus Gellius on the number of Niobe's chlidren

The Latin author and grammarian, Aulus Gellius (circa 125-180 AD) noted the various numbers of Niobids given by Greek poets, ascribing the discrepency to accumulative errors in manuscripts: "error has grown and found its way into more manuscripts" (Attic Nights, Book 20, chapter 6).

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, Book 20, chapter 7. English Translation. John C. Rolfe. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. and William Heinemann, London, 1927. At Perseus Digital Library.

Both Euripides and Sophocles wrote tragedies titled Niobe, of which only fragments have survived. So far I have not found any of the relevant passages of Sappho, Bacchylides, Pindar, Lasos, Alkman or Mimnermos mentioned by Aelian and Gellius; most appear to be lost. Although both authors are discussing "the Greek poets" and "the Ancients", it may be significant that neither mentions Ovid, who is often referred to by modern scholars in relation to the number of Niobids depicted in statue groups.

7. Aelian on the number of Niobe's chlidren

Claudius Aelianus (Κλαύδιος Αἰλιανός; circa 175-235 AD), usually referred to as Aelian, was a Roman author and teacher of rhetoric, born at Praeneste (today Palestrina), 35 km east of Rome, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus. He is known as the author of two surviving works in Greek, usually referred to by their titles in Latin: De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals; Greek, Περὶ Ζῴων Ἰδιότητος), and Varia Historia (Various History; Greek, Ποικίλη Ἱστορία), which has survived in an abridged form. Both books consist of miscellaneous articles and anecdotes.

The translation of the passage, which I have slightly tweaked, is by Thomas Stanley, 1665:

Claudius Aelianus, His Various History, Book 12, Chapter XXXVI: Of the number of the Children of Niobe. English translation by Thomas Stanley. Printed for Thomas Dring, London, 1665. At James Eason's website, Penelope, University of Chicago.

The orignal Greek text:

"ἐοίκασιν οἱ ἀρχαῖοι ὑπὲρ τοῦ ἀριθμοῦ τῶν τῆς Νιόβης παίδων μὴ συνᾴδειν ἀλλήλοις. Ὅμηρος μὲν ἓξ λέγει ἄρρενας καὶ τοσαύτας κόρας, Λάσος δὲ δὶς ἑπτὰ λέγει, Ἡσίοδος δὲ ἐννέα καὶ δέκα, εἰ μὴ ἄρα οὐκ εἰσὶν Ἡσιόδου τὰ ἔπη, ἀλλ᾽ ὡς πολλὰ καὶ ἄλλα κατέψευσται αὐτοῦ. Ἀλκμὰν δέκα φησί, Μίμνερμος εἴκοσι, καὶ Πίνδαρος τοσούτους."

Rudolf Hercher (editor), Aelian, Varia Historia, Book 12, chapter 36. Claudii Aeliani de natura animalium libri xvii, varia historia, epistolae, fragmenta, Vol 2. Aelian. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1866. At Perseus Digital Library.

8. Hyginus on Niobe, Amphion and their children

For further information about Hyginus, see the note in Homer part 2. Sections in Fabulae by Hyginus dealing with Niobe and the Niobids:

section 9, Niobe

"Amphion and Zetus, sons of Jove [Zeus] and Antiopa, daughter of Nycteus, by the command of Apollo surrounded Thebes with a wall up to [corrupt text], and driving Laius, son of King Labdacus, into exile, themselves held he royal power there.

Amphion took in marriage Niobe, daughter of Tantalus and Dione, by whom he had seven sons and as many daughters. These children Niobe placed above those of Latona [Leto], and spoke rather contemptuously against Apollo and Diana [Artemis] because Diana was girt in man’s attire, and Apollo wore long hair and a woman’s gown. She said, too, that she surpassed Latona in number of children. Because of this Apollo slew her sons with arrows as they were hunting in the woods, and Diana shot and killed the daughters in the palace, all except Chloris.

But the mother, bereft if her children, is said to have been turned into stone by weeping on Mount Sipylus, and her tears today are said to trickle down. Amphion, however, tried to storm the temple of Apollo, and was slain by the arrows of Apollo."

section 10, Chloris

"Chloris was the only daughter of Niobe and Amphion who survived. Neleus, Hippocoon’s son, married her, and she bore to him twelve sons.

When Hercules [Herakles] was besieging Pylus he slew Neleus and ten of his sons, but the eleventh, Periclymenus, was changed to an eagle by the favour of Neptune [Poseidon], his grandfather, and escaped death. Now the twelfth, Nestor, was the one at Ilium [Troy]. He is said to have lived three generations by favour of Apollo, for the years which Apollo had taken from Chloris and her brothers he granted to Nestor."

section 10, Children of Niobe

"Tantalus, Ismenus, Eupinytus, Phaedimus, Sipylus, Damasichthon, Archenor; Neara, Phthia, Astycratia, Chloris, [corrupt text], Eudoxa, Ogygia. These are the sons and daughters of Niobe, wife of Amphion."

Periclymenus, son of Chloris, the only surviving daughter of Niobe was one of the Argonauts:

section 14, Argonauts assembled

"Castor and Pollux [the Dioskouroi], sons of Jove and Leda, daughter of Thestius, Lacedaemonians; others call them Spartans, both beardless youths. It is written that at the same time stars appeared on their heads, seeming to have fallen there. Periclymenus, son of Neleus and Chloris, daughter of Amphion and Niobe; he was from Pylos."

Hyginus, Fabulae, sections 1-49, translated and edited by Mary Amelia Grant. At the Theoi Project.

section 69, Adrastus

Here, Hyginus relates the claim that Amphion named the famous seven gates of Thebes after his daughters.

"For Amphion, who had surrounded Thebes with a wall set in it seven gates named for his daughters. These were Thera, Cleodoxe, Astynome, Astycratia, Chias, Ogygia, Chloris."

Hyginus, Fabulae, sections 50-99. At the Theoi Project.

9. The Niobid relief in the British Museum and the Zeus throne in Olympia

See:

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, Chapter 11, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Arthur H. Smith (1860-1941), Catalogue of sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities Volume 3, pages 260-263 and Plate XXVI. British Museum, London, 1904. At Heidelberg University Library. |

|

|

| |

10. Niobids from the Horti Sallustiani, Rome

See: Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani, Wanderings in the Roman Campagna, pages 353-354. Constable & Co., London, and Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1909. At the Internet Archive.

Lanciani lived in the house below which the dying female Niobid now in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme was found.

11. Villa di Nerone, Subiaco

Nero's Villa (Latin, Villa Neroniana Sublaquensis or Villa Sublacencis; Italian, Villa di Nerone) is outside Subiaco (ancient Sublaqueum), a town 70 km east of Rome. The large building complex, which once stood near three lakes fed by the Anio river (today the Teverone), is thought to have been built before 60 AD. It was mentioned by Tacitus (circa 55 - circa 120 AD), who wrote that Nero was dining there when it was struck by lightning.

Cornelius Tacitus, The Annals, book 14, chapter 22. At Perseus Digital Library.

The location and geography of Sublaquensis were briefly described by Pliny the Elder (who did not mention the villa) and the Roman civil engineer, author and politician Sextus Julius Frontinus (circa 40 - 103 AD), in whose De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae (The Aqueducts of Rome, also known as De Aquis) the villa is mentioned as "... villam Neronianam Sublacensem".

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 3, chapter 17. At Perseus Digital Library.

Sextus Julius Frontinus, The Aqueducts of Rome, Book 2, chapter 93. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

Although the villa is usually referred to as having been built by Nero (reigned 54-68 AD), it has been referred to as "the celebrated villa of Claudius and Nero" (note to Pliny's Natural history, Book 3, chapter 17, in the translation cited above). So far I have found no reference by an ancient author to a connection between Claudius (Nero's predecessor, reigned 41-54 AD) and the villa, or discovered why or by whom it was "celebrated". Perhaps the assumed date of its completion in 60 AD suggests that construction was begun during the reign of Claudius.

12. The Nieborow Niobe bust in Warsaw

A similar bust, known as the "Nieborów Niobe", is now in the Nieborow Palace, Nieborow, central Poland, a branch of the Polish National Museum (Warsaw). Inv. No. Nb 11. Height 58.3 cm, width 53 cm, depth 17 cm (according to another source, height 75 cm, width 45 cm, depth 40 cm).

Dated to the 1st - 2nd century AD and thought to be a copy of a Hellenistic original of the 4th century BC. The marble head was found 1763-1764 at the Villa dei Quintili on the Via Appia, south of Rome, after which it was restored and placed in a modern bust. Purchased in Rome by the banker, antiquarian and collector Lyde Browne (? - 1787) before 1779, it was sold between 1784 and 1787, along with a large number of ancient sculptures from the collection in his country house, Warren House in Wimbledon, to Catherine II of Russia (Catherine the Great, reigned 1762-1796) for the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. In 1802 it was given to Helena Radziwiłłowa (1753-1821) who placed it in the Nieborow Palace (Pałac w Nieborowie, formerly known as the Radziwill Palace, Pałac Radziwiłłów), where she and her husband Prince Michał Hieronim Radziwiłł had gathered a large art collection.

Surviving records concerning the provenance and history of many of the ancient sculptures from Lyde Browne's collection are sparing and often vague, and have only recently become a subject of scholarly investigation.

See also a statue thought to depict Niobe and her youngest daughter, also found at the Villa dei Quintili, above. |

|

Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani (1845-1929),

Italian archaeologist.

Source: Camden McCormack Cobern,

The new archeological discoveries

and their bearing upon the New

Testament and upon the life and

times of the primitive church,

page 356. Funk and Wagnalls,

New York and London, 1917.

At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

A print showing the Dresden cast collection as displayed in the Mengsische Museum in 1799.

Displayed in the Cast Collection room of the Semperbau, Dresden.

A monochrome version of the print also appeared in the

1831 catalogue of the Dresden Cast Collection (see below). |

| |

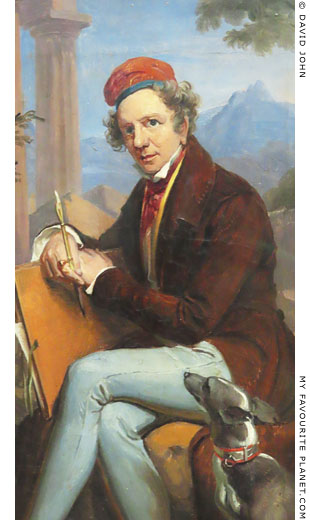

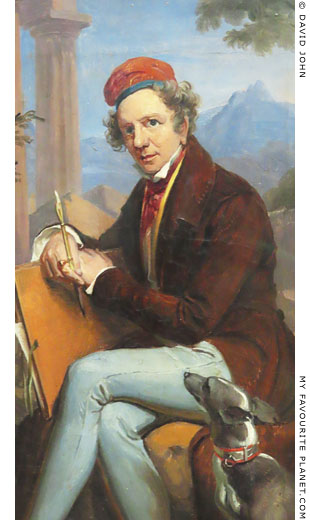

13. Anton Raphael Mengs and the Dresden cast collection

Around 1753, while living in Rome, the German-Bohemian painter Anton Raphael (or Raffael) Mengs (1728-1779) began acquiring what would turn out to be an enormous number of plaster casts of sculptures, mainly of classical works as well as some Renaissance and Baroque examples, in the collections in Rome and Florence, initially as a commission for King Carlos III of Spain, whose court painter he became from 1761 to 1769, and as teaching aids for pupils at his studio in the Via Sistina. His collection became known as die Abguss-Sammlung von Anton Raphael Mengs (the cast collection of Anton Raphael Mengs) or die Mengs'sche Abguss-Sammlung.

After his death 833 casts from the collection were purchased in 1783 on behalf of Friedrich August III, Elector of Saxony (1750-1827; from 1806 King Friedrich August I, the first king of Saxony) from Madame Maron, Mengs' sister. They were transported by ship in 96 boxes, and arrived in Dresden in 1784. The journey by water and the long period they spent in the boxes caused damage to some of the casts. In the same year Friedrich August gave them to the Kunstakademie. Casts from the collection were first exhibited in 1786, and in 1794 they were set up in the Mengs'ische Museum "unter dem Saale der Bildergallerie am Neumarkt" (under the halls of the Picture Gallery on the New Marketplace), on the ground floor of the Stallgebäude, the former palace stables, the first floor of which had been converted into an art gallery for paintings (now the Johanneum, which houses the Dresden Transport Museum). They were admired by a number of visitors to Dresden, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Further casts from other sources, including from Egyptian, Assyrian and Etruscan works, were subsequently acquired, and the collection steadily grew. In 1857 the collection was moved to the newly-built Neues Königliches Museum (New Royal Museum) in the Semperbau (Semper Gallery, named after its architect Gottfried Semper) on the north side of Zwinger courtyard, where the collection of antiquites was also housed.

With the archaeological boom of the second half of the 19th century, museums and collectors competed to acquire newly discovered artefacts from sites such as Athens, Pergamon and Ephesus. When the originals could not be obtained, museum directors contented themselves with casts, which at some places were being produced on an almost industrial scale. During excavations at Olympia in December 1876, casts from finds were delivered to Dresden within weeks of their discovery.

The Dresden museums rapidly ran out of space for the new acquisitions and, after much polital debate, the 16th century Zeughaus (armoury) was transformed 1884-1887 into a museum, named the Albertinum after King Albert of Saxony (reigned 1873-1902), to house the Sächsiche Hauptstaatsarchiv (Main State Archive of Saxony) and the Königliche Skultpurensammlung (Royal Sculpture Collection), which included ancient sculptures, mosaics and other objects, some works from the Renaissance and later, and the cast collection. The second floor, dedicated to casts, was the first part of the museum to be opened to the public on 19 January 1891, with separate rooms for works of particular artists or themes, such as Michelangelo, Praxiteles, Lisyppos, the Parthenon, Pergamon, Olympia and the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. The Niobe-Zimmer (Niobe Room) exhibited full casts of the Uffizi Niobid sculptures (rather than just busts), purchased by the museum's director Georg Treu (1843-1921; from October 1882 director of the antiquities and cast collections) at an auction in Frankfurt am Main in 1889.

During World War II bombing of Dresden on 13th February 1945 part of the Albertinum was damaged and some of the larger casts were destroyed. After the war the casts and original antiquities of the Dresden Antikensammlung, including sculptures and ceramics, were taken by the Soviet Union to Moscow, but returned to Dresden in 1958.

Now part of the Skulpturensammlung der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Sculpture Collection of the Dresden State Art Collections), the casts have been moved a number of times since the war. First stored in the cellar of the Albertinum (now the museum for sculpture and modern art), they were moved due to flooding of the River Elbe in 2002. A few of the casts of ancient sculptures were until recently exhibited in the Albertinum, but since 2016 around 120 of the over 400 surviving casts have been exhibited in the Semperbau, which now exhibits paintings of the Old Masters (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister).

Plaster casts of sculptures were for long highly prized by many museums, universities, art schools and private collections around the world. For those who were not able to travel to Italy, Greece or Turkey (i.e. most people), including students and art lovers, they provided the only opportunity to appreciate and study famous or exemplary artworks. Many were coloured and polished to imitate the marble or bronze surfaces of the originals. However, during the late 20th century, as more people were able to travel to museums further abroad or had access to higher quality images of originals in books and films and on websites, casts began to seem dull and definitely out of fashion. Casts are difficult to maintain and keep clean and fresh-looking, and some cast collections were long-neglected. To anyone who has seen an original of fine translucent marble or the patina of an ancient bronze, plaster appears flat and lifeless.

Casts became an embarrassing waste of space for many museums attempting to update their image, and they were often consigned to storerooms and depots, or sold or otherwise disposed of. In one of the worst cases, in 1950 the casts of the Rijksmuseum collection in Amsterdam were deliberately smashed up or sold off as junk (see: Frederik Theodoor Johannes Godin, Antiquity in plaster: Production, reception and destruction of plaster copies from the Athenian Agora to Felix Meritis in Amsterdam, page 270. PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2009).

However, many casts remain fascinating and still have something to teach us about the originals and their history, not to mention the history of art connoisseurship, collecting and museums themselves. Some casts are now all that remain of several lost artworks.

In the Semperbau room in which some of the casts are presently displayed (2018), a text catalogue with brief descriptions of the works in German is available to consult within the gallery (see photo, right). Unfortunately there are no copies for sale and the information is not available on the museum's online collections database, which contains some good photos but no depth in its data.

A number of catalogues of the Dresden cast collection were published in the 19th century. None are illustrated, and in all entries are numbered in order of the casts' positions in the respective museum at the time they were written. The catalogue numbers do not relate to the modern invoice numbers. Entries for each cast are usually short, some with little or no information about the originals.

The PDF versions available online do not contain searchable text.

Johann Gottlob Matthäy (1753-1832), Verzeichniss der im königl. sächs. Mengs'ischen Museum enthaltenen antiken und modernen Bildwerke in Gyps. Arnoldischen Buchhandlung, Dresden and Leipzig, 1831. PDF at Die Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB).

100 pages, plus a 6-page introduction and frontispiece showing the cast collection in the vaulted hall of the Mengs'sche Museum. Very brief descriptions of cast. Sizes are given in Fuss (F) and Zoll (Z), the German equivalents of foot and inch. Only 72 pages deal with the cast collection. Strangely, the contents from page 73 onwards consist of unrelated lists: uncommented lists of some of the sculptures in museums in Rome, Florence and Naples, inexplicably in French; an advertisement listing Matthäy's own copies of sculptures; and a list of books about Dresden.

PDF also available at the Hathi Trust Digital Library: catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010249539

Carl Theodor Chalybaeus, Das Königlich Sächsische Mengs’ische Museum zu Dresden. Blochmann, Dresden, 1843. PDF at SLUB (lovely name for a library).

48 pages and a 2-page introduction. More detailed entries, but terse, very academic and full of unexplained abbreviations, many literary references.

Hermann Hettner, Das Königliche Museum der Gypsabgüsse zu Dresden. E. Blochmann & Sohn, Dresden, 1881 (vierte Auflage, 4th edition). PDF at SLUB.

179 pages and a 2-page introduction. The most detailed entries. Includes casts of Egyptian, Assyrian, Etruscan, Greek (with sculptures from the Parthenon and Olympia) and Graeco-Roman works, at the time displayed in separate rooms of the Semperbau. There is also a section on the casts of Medieval and modern works then in the Zwinger, and an appendix on casts in the Bust Room.

See also:

Gudrun Elsner, Kordelia Knoll (editors), Das Albertinum vor 100 Jahren - die Skulpturensammlung Georg Treus (The Albertinum 100 years ago - the sculpture collection of Georg Treu). Catalogue of the exhibition in the Albertinum, Dresden, 18 December 1994 - 12 March 1995. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 1994. With several photos, drawings, plans and maps, illustrating the history of the Albertinum and Dresden art collections, archaeological contexts, individual objects (particularly ancient sculptures and casts) and some of the key personalities. Particular references to the history of the cast collection on pages 38-39, 46-48, 58-62; a photo of the Niobe Room in 1891, Cat. No. 93, page 105. |

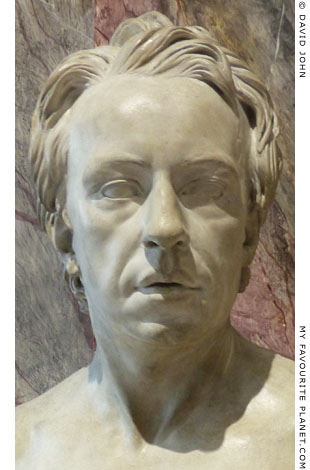

Detail of a plaster bust

of Anton Raphael Mengs.

1779. Height 65.5 cm, width 37 cm,

depth 24.5 cm.

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden.

Inv. No. ASN 4728.

The original bronze bust was made in Rome

around 1777-1779 by the Irish sculptor

Christopher Hewetson (circa 1736-1798).

There are a number of bronze and plaster

copies in various museums and collections.

The Spanish diplomat José Nicolás de

Azara (1730-1804, from 1785 Spanish

ambassador to the Papal court), a friend

and admirer of Mengs, commissioned

Hewetson to make a marble version of

the bust which was placed in a niche

in the Pantheon in Rome in 1782. |

| |

Text catalogues (in German) in the cast

collection room of the Semperbau, Dresden. |

| |

See other casts from the Dresden collection:

the "Belvedere Antinous" Hermes statue

the "Townley Antinous" bust

the "San Ildefonso Group"

the Vatican Dionysos Sardanapollos

relief of a Dioscuros with a horse

the "Medusa Rondanini"

the "Nike of Paionios" statue |

| |

A marble bust with a modern copy of the

head of a daughter of Niobe. Made in Italy

around 1700 by an unknown artist. The

original is in the Uffizi, Forence (see above).

Hall of Antiquities Semperbau, Dresden.

Inv No. H4 51/200. First mentioned in

the 1765 inventory of the museum. |

| |

| |

Part of the Dresden cast collection in a room of the Semperbau in 2018. |

| |

14. James Stuart on the Uffizi Niobid Group

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, page 93. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

For further information about James Stuart (1713-1788), see Athens Acropolis gallery page 12, 8, 32, 35 and 36.

The notes of the editor(s) on the same page of this edition of Stuart's book, published after his death, discuss Cockerell's theory concerning the Uffizi Niobid Group (see above).

15. The marble types of the Uffizi Niobid Group

Many ancient sculptures have been judged to be made of particular types of marble (Pentelic, Parian, Proconnesian, Carrara, Pavonazetto...), or described as fine or coarse grained or crystalline, veined, and so on. Often such descriptions have been based on the reports and opinions of one or two scholars, published in academic books, articles and catalogues, many now more than a century old. Such opinions and theories are even referred to as "traditional" (see also the note on the Dionysus page).

Identification of marbles has influenced debates and led to much speculation on where, when and even by whom the sculptures were made. In the case of the various Niobid groups, many scholars would love to know whether they were Greek originals taken as booty to Rome, or made during the Roman period, either as originals or copies of much older Greek works.

Recently, new techniques and technologies have allowed mineralogists and experts from several fields to analyze stone more accurately. The methods are still not foolproof and such work remains difficult, not the least because the marbles, consisting of limestone compressed by aeons of geological activity, are often mixed with other minerals. Marble samples from a particular quarrying area can vary widely in physical structure and chemical composition, whereas their complex structures often make them difficult to distinguish from those from an other area.

The Uffizi Niobid Group presents particular problems for analysis, since it includes sculptures which do not belong to those found in the Vigna Tommasini in 1583, and restorers used other types of marble and parts and fragments of other sculptures for their repairs. An Italian team have studied and analyzed the marble of eleven of the Uffizi statues, including one which was not originally part of the group (male Niobid climbing a rock, Inv. No. 304), taking into account properties such as colour, texture, translucency, crystal structure and isotopic density. They concluded that individual sculptures were made of different types of marble, suggesting that they may have been made at separate workshops, perhaps in Greece and Anatolia (Asia Minor). The marbles are thought to be:

Pentelic marble, from Mount Penteli, north of Athens (6 statues);

Docimium (Δοκίμειον, modern Iscehisar, Turkey) and Göktepe marble, from near Aphrodisias, Phrygia/Caria, west-central Anatolia (4 statues);

Paros II, Chorodaki marble, from the Chorodaki valley (Lakkoi), Paros, although very similar to Proconnesian marble (1 statue, Inv. No. 304).

See: Donato Attanasio, Chiara Boschi, Susanna Bracci, Emma Cantisani, Flavio Paolucci, The Greek and Asiatic marbles of the Florentine Niobids. Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 66, February 2016, pages 103-111. At researchgate.net.

The history of the Uffizi Niobid Group is more complex than many modern sources lead us to believe, and the methods used to analyze the marbles, using sophisticated scientific techniques as well as human expertise and experience-based intuition, are far from easy to describe. This fascinating illustrated article does a good job of explaining both aspects of the topic for non-technical readers.

16. Ausonius on Niobid

Decimus or Decimius Magnus Ausonius (circa 310-395 AD), usually referred to as Ausonius, was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala in Aquitaine (modern Bordeaux, France). The translation of the epigram, taken from Anthologia Graeca, 16.129, has been quoted in many publications, including:

The Works of Anacreon, Sappho, and Musaeus, translated from the Greek by Francis Fawkes, note on Ode XX, page 116. Whittingham and Rowland, London, 1810.

Another version of the epigram in Latin and English:

In Signum Matmoreum Niobes

Vivebam: sum facta silex, quae deinde polita

Praxiteli manibus vivo iterum Niobe.

reddidit artificis manus omnia, sed sine sensu:

hunc ego, cum laesi numina, non habui.

For a marble Statue of Niobe

I used to live: I became stone, and then being

polished by the hand of Praxiteles, I now live again

as Niobe. The artist's hand has restored me all but

sense: that, when I offended gods, I had not.

Hugh G. Evelyn-White (translator), Ausonius, Volume II (of 2), Book XIX, Epigrams on various matters (Epigramata de diversis rebus), Epigram LXIII, pages 192-193. W. Heinemann, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1921. At the Internet Archive.

17. Niobid statues discovered at the Corvinus villa

Seven statues of Niobids and a number of fragments, dated to the 1st century BC, were unearthed in June-July 2012 by archaeologists at the site of a planned construction in the town of Ciampino, south of Rome. The site is thought to have been the villa of Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 BC - 8 AD), a Roman general, politician, author and patron of literature and art (also a character in the novel Ben Hur), who is also thought to have been a friend or patron of Ovid. The larger than lifesize statues were found near the remains of a large natatio (outdoor swimming pool) next to a thermal bath complex, suggesting that they may have decorated the pool.

18. The Niobe and Artemis statuettes from Tsoutsouros, Crete