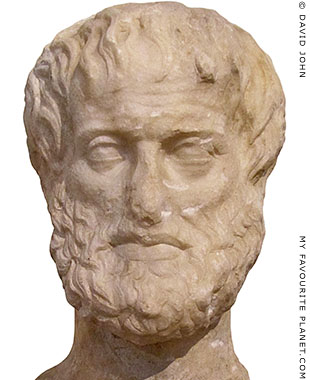

The archaeological site of Aristotle's Lyceum in Athens was open for a short time this summer - for philosophers only. Around 3,000 participants of the seven-day 23rd World Congress of Philosophy [1] were permitted to visit the recently-excavated site in the centre of Greece's capital, and many attended congress sessions there, including a series of talks on "The importance of Aristotelian philosophy today" (Σημασία της Αριστοτελικής φιλοσοφίας σήμερα) on 9th August.

This was the first time that members of the public - albeit a rather select band - had been allowed into the site since its discovery in 1996.

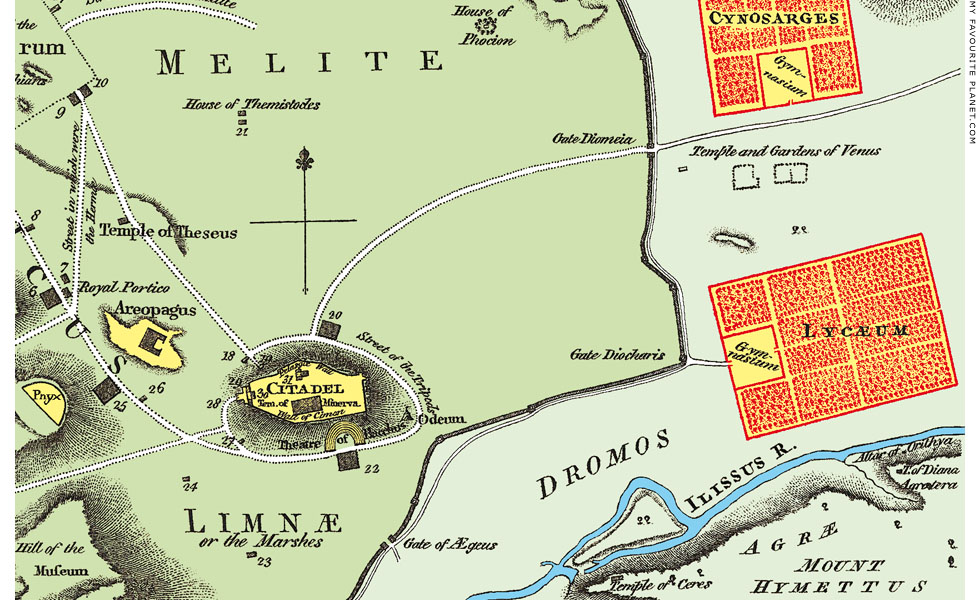

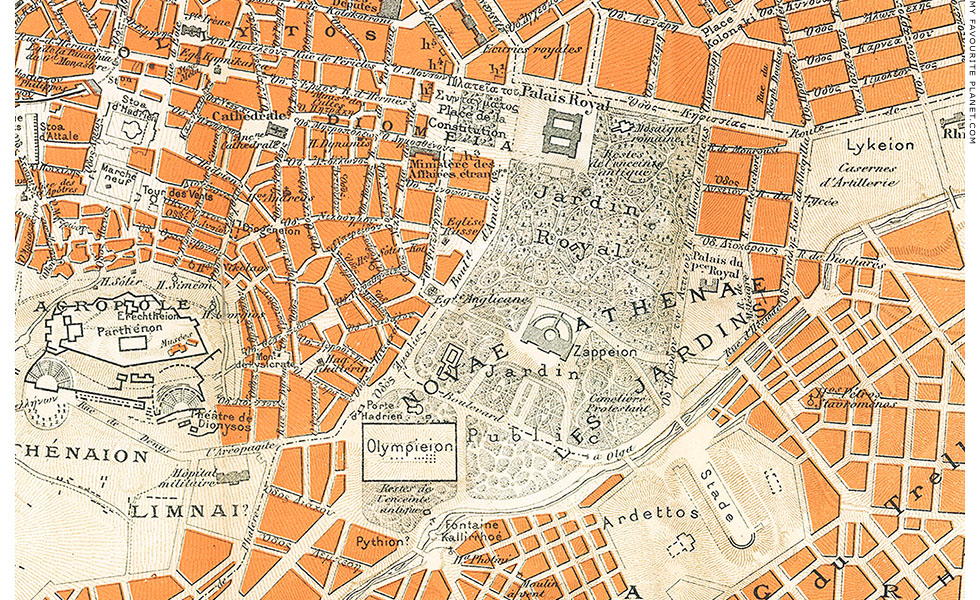

From references by ancient writers it had been known for over two centuries that the Lyceum gymnasium, in which Aristotle established his school of philosophy in 334/335 BC, was situated somewhere outside the ancient city walls of Athens (see map 1 below), just to the east of the modern central Syntagma Square and the Greek parliament building. The Lyceum has been marked on historical maps, with varying degrees of certainty, since the 18th century, and a nearby street connecting Rigilles and Herodou Attikou Streets was even named Lykeiou (Οδός Λύκειου). However, it was only rediscovered by chance during the construction of a new contemporary art museum in late 1996.

The site, with an area of 2,400 square metres (50 x 48 metres), had been used as an unpaved car park, and was previously the location of an artillery barracks [2] (see map 2 below). It seems a miracle that such a prime piece of real estate in this densely built-up part of the city - the highest rent district in Greece - had not already been covered by yet another concrete monstrosity, even during the shameless building boom under the corrupt military dictatorship in the 1960s and 70s. It may be that the suspicion that the Lyceum lay here saved it, or that the land is surrounded by other cultural institutions such as the Byzantine and Christian Museum, the Athens War Museum, the Athens Conservatory and the Sarogleion (armed forces Officers' Club, see photo below).

On the discovery of the remains of ancient buildings construction work on the art museum was halted and archaeologist Efi Lykouri was called in to investigate. By January 1997, the Central Council of Archeology was able to confirm that the ruins were those of the Lyceum, and the then Greek Minister of Culture, Evangelos Venizelos announced:

"There is no doubt whatsoever that this is the school where Aristotle taught. We have decided that the excavations to unearth the remains will continue and that the site will co-exist in harmony next to the Museum of Modern Art so that the two can be visited simultaneously by Greeks and tourists."

However, as the extent and importance of the site became apparent, this decision was revised and the construction of the art museum was abandoned. [3] Archaeologists got busy with their spades and trowels, and politicians and officials considered how best the site could be developed and exploited as a cultural tourist attraction.

Plans evolved for a landscaped park around the site and the Ministry of Culture held an architectural design competition. The winning entry, announced in 2003, featured an enormous 12 metre high glass and steel canopy with a curved translucent roof to cover the ruins.

The archaeologists continued to excavate the site, and it became obvious that the site would not be opened to the public in time for the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens.

More disappointingly, the archaeological finds at the gymnasium site proved meagre: only the foundations and lower courses of walls of the wrestling area (palaestra) and library and part of a baths from the Roman period were uncovered; there appeared to be no sign of statues, inscriptions or any significant evidence of the site as the ancient sanctuary of Apollo Lykeios, after whom the Lyceum (Λύκειον, Lykeion) was named, or as a gathering place for philosophers; and unfortunately, no treasures, revelations or "astonishing discoveries". So far, very little has been published about the excavation finds in English, which can only be taken as a discouraging sign.

Some historians and archaeologists have expressed doubt concerning the identification of the site as the Lyceum, and in 2001 the American archaeologist John M. Camp wrote:

"Some modest remains uncovered in 1996 several hundred meters farther east [of Syntagma Square] have been identified as the remains of the palaistra (wrestling ground) of the gymnasium, but as of 2000 the identification remains unsubstantiated." [4]

Political interest in the open-air museum project appeared to have dwindled as towards the end of the decade Greece slid into economic crisis. By 2009 the country had a new government and a new Minister of Culture, Antonis Samaras (since June 2012 Prime Minister), who in April of that year announced not only the revival of the project but also a budget of 4 million Euros, donated by the betting firm OPAP, which at that time was still 33% state-owned (since privatized). It was also announced that the project would be completed and the site opened to the public in 2010.

This proved to be yet another of many official announcements promising the opening of the site which have become almost an annual ritual. Several times after this author had heard that the site would be opened he dutifully traipsed along to only to find the same fence screening a closed building site on which nothing whatsoever was happening. In September 2010 a press release by the official Athens News Agency stated that the restoration work was finally - really, really, really - about to begin. However, when I visited the site again in May 2011 there had been no discernible progress (see photo below).

Although the Greek Ministry of Culture had 4 million Euros at its disposal, it had not even managed to put up a sign to indicate the presence of the Lyceum or what was planned for the site.

Again, in February this year an official announcement trumpeted the opening of the site by mid-summer. And this is where we came in. I was among those few fortunate enough to be able to visit the Lyceum in August, and was told that the public opening was now scheduled for October. Since then, silence.

There is no sign of the much-vaunted giant canopy, which appears to have been cancelled, just the same three small temporary canopies covering sensitive areas. Having visited the site, one wonders what the function of such a large, expensive canopy, which would have cost 400,000 Euros, could have been. It would not have been closed, so would protect neither the ruins nor visitors from weather; its translucence would have meant no shade from the sun. It would have certainly blocked the public's view of the remains, particularly from the adjacent Rigillis Street, the only place where the site can be seen from the outside. It seems to have been more of a grandiose architectural statement, a propaganda gimmick, or an attempt to divert attention from the deficiency of visual interest for the general visitor.

The garden around the site, on the other hand, is wonderful, and a particular joy to behold as an oasis of green in the hectic centre of Athens. The exposed area of the gymnasium dig has been surrounded by a lush lawn, itself a rare luxury in arid Hellas. Footpaths lead the visitor from the site's two entrances and around the ruins. The planting of trees, flowers and herbs [5] is also a balm to the eyes and helps provide a pleasant setting to contemplate history, philosophy, the meaning of life and the best way to get to the Plaka for lunch.

The presence of the tiny, little-known church of Agios Nikolaos on the eastern edge of the site (see photo below) and the other cultural buildings surrounding it add to the atmosphere. The latter also provide a visual and aural buffer zone between the site and the non-stop traffic on Vassilissis Sofias Avenue.

Apart from the garden, you may think that there is not a lot to look at on the site itself, especially if you have already seen Athens' other ancient splendours. But it is still an important place that deserves to be saved and preserved, and the people who have worked hard over the last 17 years to make it happen are to be applauded for their efforts. It is a tribute to Socrates, who spent much of his days here, to Aristotle and his Peripatetic school of philosophers who have influenced our ways of thinking and learning, and to the innumerable people who played, trained, bathed and worshipped here over several centuries.

The discovery of the Lyceum has also provided another piece of the puzzle of the topography of ancient Athens, vital for historians' attempts to decipher the city's past.