|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Cheshire Cat Blog > 2013 |

|

|

back |

The Cheshire Cat Blog

|

|

June - July 2013 |

|

| |

|

The Queen Elizabeth II Court of the British Museum, London.

Revamped by Sir Norman Foster and opened in 2000.

Museum boom - part 1

The Cheshire Cat tests the turnstiles of modern museums. |

| |

Before we get started ...

If you have ever travelled to a museum only to find that it is closed, you may like to to know about some of the museums you will not be able to visit this year.

To the right is a list of a few of the museums which are currently closed for renovation or rebuilding, and we report on some of them below. So far we have only listed those we know about in Greece and Turkey.

We will be adding further news and information about museums in future editions of this blog.

If you have any information about other museums, please get in contact.

We welcome information about any kind of museum anywhere in the world, whether it is opening, closing or changing.

See also:

Museum boom part 2 - Digging Aristotle

The Cheshire Cat Blog about the oft-delayed opening of the site of Aristotle's Lyceum in Athens. |

| |

| |

| |

For the turnstiles |

|

|

The Neo-Classical Ionic facade of the main entrance to the British Museum, London.

|

Museums are big business, attracting millions of visitors each year. The top global attraction, the Beijing Palace Museum (the Forbidden City), draws around 12 million punters annually, and 9,720,260 went to the Louvre in 2012.

While these institutions are ostensibly concerned with culture and education as their primary raison d'etre, many are now locked into their local and national governments' strategic financial objectives; in other words, competing for a share of tourist dollars, euros, pounds, yen and yuan.

Many people base their decisions about where to spend their vacations and hard-earned cash on a potential destination's sights and attractions. Historical sites and museums are often on top of holiday-makers' wish-lists, although even the British Museum, Brtiain's top visitor attraction with 5,575,946 visitors in 2012, has to compete with other museums, including the Tate Modern, the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, not to mention tourist magnets such as the London Eye, Madame Tussauds, Blackpool Beach, stately homes, zoos...

The competition is hot, if not cut-throat, to acquire the best objets, put on the most spectacular exhibitions and pull in the biggest crowds.

In order to keep in the game, museums are continually having to repackage themselves, reinvent their public images, grow and improve, by renovating, building new extensions or even new premises, equipped with the latest lighting, display, information, conservation, security and crowd control technologies.

Yes, crowd control: the deliberate policies of attracting masses of people mean that visitors to museums and historical sites are increasingly being treated like fans at football matches and other huge sports events, or passengers on mass transport systems.

The old-fashioned ticket booths are being replaced by hi-tech facilities which process credit cards, automatic ticket machines and online booking systems; the friendly or bored-looking uniformed guards who tore your ticket on admission have given way to stainless steel turnstiles.

The modern push for increased efficiency in museum visitor-flows began in the 1970s when the designers of the Paris Pompidou Centre, Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Su Rogers, Gianfranco Franchini and Ove Arup & Partners, took a look at how people actually moved around public spaces. One of their aims, which was largely successful, was to design a cultural centre in which visitors could move around exhibition spaces without crowding or bumping into each other. The subsequent placing of entrances and escalators also meant that visitors were hardly aware that they were being led - literally by design - through the planned sequence of exhibits (some curators prefer chronological sequences while other go for thematic areas).

Their studies were informed by urban planning and traffic surveys, and in turn influenced the rationalized planning of other museums and public spaces such as shopping centres, airports and railway stations (though obviously not in Berlin, which is quite another story).

The motivations for the constant craving for improvement on the part of museum administrators include goals summed up by the Oxford Pitt Rivers Museum (see below) planning project acronym "VERVE: Visitors, Engagement, Renewal, Visibility, Enrichment". The Pitt Rivers, to which admission is free, is one of the diminishing number of prominent museums which can still honestly claim to provide a public service not driven merely by business interests or marketing urges.

But improvements are expensive, especially if you engage "star architects" to tart up your turf and raise your profile. The British Museum, another free-to-enter institution, could depend upon public and private funding to afford to commission Sir Norman Foster to create the impressive atrium in their formerly dowdy entrance court.

Other museums resort to pushing up admission prices and moving parts of their inventories into special, highly-publicized exhibitions for which extra tickets must be purchased. They also raise revenues through their books and publications, shops, cafes and restaurants, as well as renting out parts of their premises for filming,

special events and even corporate parties.

During my most recent visit to Ephesus, the area around the Library of Celcus, the site's most popular ruin, was cordoned off due to preparations for a private wedding celebration. Understandably, several people were a bit miffed about this, having paid their 25 Turkish Lira admission charge. |

Turnstiles in the landscape.

The entrance to the Asclepieion

archaeological site, Pergamon. |

| |

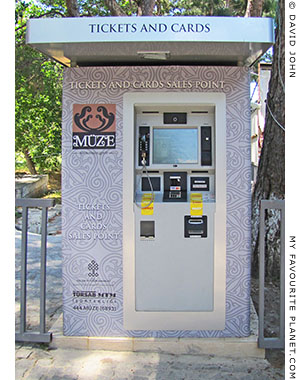

Ticket and card "sales point" machine

at the entrance to the Ephesus

archaeological site, Turkey. |

| |

| |

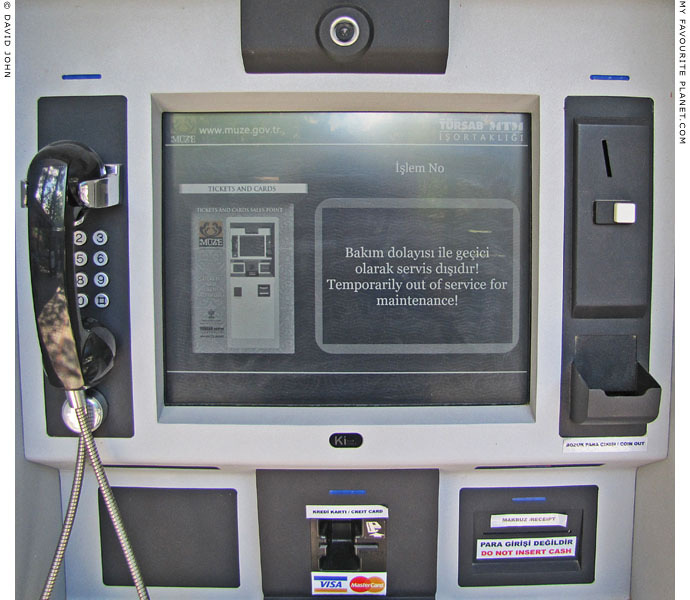

Oops! The sales point is out of service again. So it's back to old-fashioned cash.

Luckily, there is a PTT post office bank at the entrance to

the Ephesus archaeological site for currency exchange. |

| |

| |

That's edutainment |

|

|

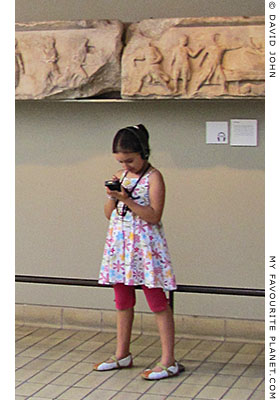

A young visitor to the British Museum explores her multimedia guide.

In the foreground: a statue of a Nereid from the 4th century BC Lycian Nereid Monument (see below). |

| |

Listen with father |

|

It has been quite a while since museums could content themselves with merely exhibiting a bunch of objects accompanied by little labels. Even catalogues and contextual information boards are now considered old hat. What we, the public, really, really want, apparently, is a "Kulturerlebnis" or a "Kunstvergnügung", the kind of words creeping into Kulturbusiness vocabulary for which the translation "an enjoyable cultural experience" is just not "sexy" enough.

Several museums have experimented with more interactive exhibits, of the play-and-learn, touchy-feely, try-it-and-see-what-happens varieties, and many of these have been successful, particularly at science and technology museums. A world leader in this kind of interactivity is the Smithsonian Institute's National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C., at which you can not only look at vintage aeroplanes (sorry, airplanes) and used spacecraft, but even get your hands on a piece of real genuine Moon rock.

It is a bit more challenging for art and history museums to devise interactive exhibits: how can you allow visitors to have a tactile experience of a Rembrandt, or engage in some action painting in the foyer? Most museum visits are strictly hands-off experiences.

The archaeological site at Ephesus has a tiny Museum for the Visually Impaired, in which visually impaired visitors can touch plaster casts of ancient sculptures and reliefs. In theory. However, there is no information given about this museum, and it always appears to be locked and unattended. When I saw it in May this year it looked as though nobody had visited it or cleaned it since I was last there in 2004.

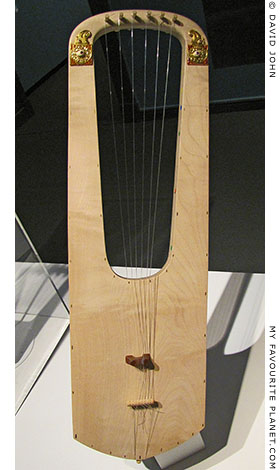

A recent exhibition in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin was a little more successful in this respect [1]. Exhibits included replicas of ancient musical instruments which a label invited visitors to try out. So I did. At my first tentative twang on the strings of a lyre the eyes of a group of children almost popped out their heads with amazement. "Ohmygod! That man is playing with the museum stuff!" I pointed to the label and they needed no further encouragement. A new band was instantly formed, then everybody wanted a go. I discreetly left the room, for the sake of my eardrums, you understand.

But since "Look, don't touch" is the general rule at most museums, designers have to come up with other ways of getting us "involved", or at least interested.

Videos and interactive audio-visual displays have limited appeal, except for maybe school groups, students, real enthusiasts for a particular subject and those waiting for the rain to stop. If you only have an afternoon to visit an enormous museum or a specific exhibition, for example a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see an artist's major works in the flesh under one roof, the last thing you want to do is spend an hour in a darkened room gawping at a beamer projection, or trying to master the geeky interface of a computer terminal. Let me just see the goddam show, and perhaps I'll buy the DVD to watch at my leisure.

Berlin style |

|

More promising are the portable audio and multimedia guides available at many museums, as well as the increasing number of cellphone guides. You can also use your mobile phone to search the internet for information about specific exhibits. Such virtual guides are constantly improving in design, ease-of-use and usefulness. But still, it's a bit strange to see people spending more time absorbed in fiddling with a handheld device than actually looking at an exhibition.

Another recent phenomenon is the number of headphone-wearing individuals and groups drifting silently around museums, following the voice of their electronic guide. Sometimes they feel obliged to stand in front of an exhibit until the voice has finished describing it to them and they are permitted to move on. Slight fidgeting and other body language signals betray impatience at having to wait in front of a boring object while they can spot something far more interesting ten tantalizing metres further on. Perhaps they haven't figured out how to fast-forward the device, or are far too polite to interrupt their charming virtual companion. Transfixed in narration.

It is uncanny to see these detached entities floating around, and annoying when your view of an exhibit is suddenly blocked by a gang of digitalized zombies who have been rendered oblivious to the space or other beings around them by tiny voices in their heads; you know you will have to wait behind these fidgeting fixtures until the audio avatars release them and allow them to lurch onwards, and you can continue to study the curio in question.

The rapidly-proliferating audiotouritis malady is closely related to those afflicting wearers-of-Walkmen and bellowers-down-cellphones, though the collateral sufferers are the innocent bystanders and fellow train or bus passengers. I am therefore not convinced that museums should really be encouraging the use of these devices which spread debilitating diseases.

Edutainment notes

1. "Jenseits des Horizonts, Raum and Wissen in den kulturen der alten Welten" (The other side of the horizon - space and knowledge in the ancient world), special exhibition at the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, 22 June - 30 September 2012. |

DON'T TOUCH! |

| |

Playalongalyre

Replica of the "Sutton Hoo Lyre",

England, early 7th century AD.

Reconstruction:

Graeme Lawson, Cambridge.

German Archaeological Institute, Berlin.

Inv. DAI-OA M2 |

| |

Turn on, tune out. |

| |

| |

| |

Hunters and collectors |

|

|

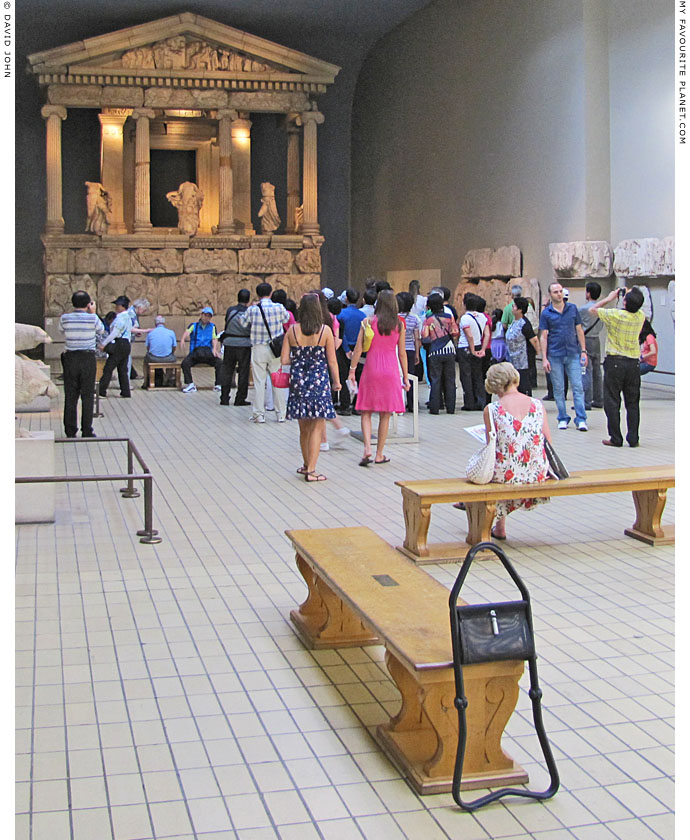

Visitors to the British Museum crowd around the Nereid Monument

(390-380 BC) from Lycia, southwest Turkey. |

| |

gallery closed.

British Museum. |

|

Early humans developed from hunter-gatherers to hunters and collectors (to borrow Holger Czukay's phrase) and farmers and collectors, as they took up agriculture and became less nomadic and more sedentary. With the establishment of permanent homes, settlements and cities, people began to gather possessions as signs of wealth, prestige, religious devotion and early manifestations of enjoyment of and curiosity about natural and man-made objects. Apart from tools, weapons, utensils and clothing, Neolithic people made, traded and collected items not essential to survival, including jewellery and other works today considered as art.

As time went on some of these collections and the objects in them became larger, more elaborate, and often more specialized, as in the case of statuary and libraries. Only kings and emperors could afford really serious collections, although some wealthy individuals such as the Athenian Herodes Atticus and his wife Aspasia Annia Regilla were rich enough to commission sculptures and other luxurious objects to adorn their villas in Greece and Rome, and to subsidize the construction of grand public buildings decorated with artworks, such as the Odeion of Herodes Atticus and Panathenaic Stadium in Athens (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 32).

Apart from private art collections, architecture, sculpture, painting, mosaics and books were increasingly accessible to the public in many cities of the Graeco-Roman world. Temple sanctuaries, then churches, monasteries and mosques, and later the first universities, became repositories of the arts, crafts and literature, and centres of learning and taste.

Following the Renaissance and Enlightenment in Europe, more people began to take an interest in studying and collecting natural, scientific, artistic and historic objects. Specimens of plant and animal species and rocks were collected by early botanists, zoologists and geologists.

Antiquarians, who were later to become known as historians and archaeologists (as well as a host of other specialists such as palaeoanthropologists), travelled further abroad in search of signs of the past, hauling home coins, inscriptions, sculptures and anything else they could buy or dig up and carry off. What they could not acquire they sketched or wrote about. Most antiquarians were gentlemen amateurs, such as members of the 18th century British Society of Dilettanti.

Still the best collections and the rights to exploration remained in the hands of the rich and powerful: in Europe kings, aristocrats, popes and top clergy; and in the Ottoman Empire sultans, pashas and viziers. The greatest concentration of antiquities was in Italy, especially in Rome, to which students of art and architecture flocked to study from all over Europe in the 17th-19th centuries. Some of these gentlemen travellers undertook "Grand Tours" of cultural destinations, which extended ever further, from Italy to the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, the Holy Land and Egypt. Many took home booty of ancient objects for their studies and drawing rooms.

Collections of all sorts formed the contents of cabinets of curiosities opened to the public of western cities eager to be astonished and even revolted by rotting Egyptian mummies, stuffed malformed animals and gruesome greegrees.

One of the most avid private collectors of the 19th century was the English army officer and archaeologist / anthropologist Lieutenant-Colonel Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827-1900), who picked up around 22,000 disparate objects from around the world. These objects now fill old-fashioned wood and glass cases and cabinets and clutter the walls of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. The somewhat bizarre but fascinating collection, which renders the word eclectic inadequate, ranges from shrunken heads, fetishes, tools and weapons to a lump of hashish. See the Pitt Rivers Museum website at prm.ox.ac.uk.

Other travellers were far more ambitious, and Lord Elgin was among the 19th century freelancers who restarted a trend, already common practice in ancient times, of the wholesale freighting of huge sculptures and chunks of ancient architecture back to their native lands. Such large-scale trophies became the core of royal and national collections which evolved into the renowned museums of London, Paris, Berlin, Munich and Vienna. (See Losing their marbles, Edwin Drood's Column, 21 June 2011.) |

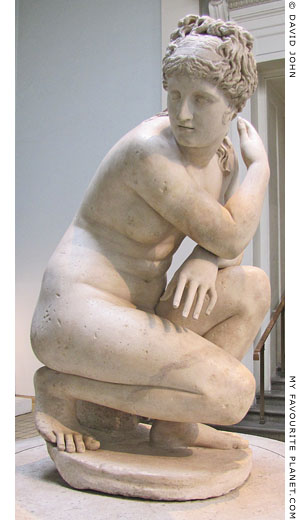

Crouching Aphrodite statue, 1st or 2nd

century AD Roman copy of a 2nd century

BC Greek original.

British Museum. Sculpture 1963. 10-29. 1.

Known as "Lely's Venus", after the artist

Sir Peter Lely (1616-1680) who purchased

it from the collection of Charles I after the

king's execution in 1649. It was later

reacquired by the royal family, and in

2005 was loaned by Queen Elizabeth II

to the British Museum.

The Crouching Aphrodite type statue

appears to have been popular in Roman

times. The National Archaeological Museum

in Naples, for example, has two copies. |

| |

English archaeologist Charles Fellows

(1799-1860) and workers in Lycia,

southwest Turkey. On the right is the

base of an inscribed Lycian pillar tomb,

circa 400 BC.

Drawing by George Scharf (1820-1895). |

| |

| |

| |

Ephesus Museum, Selçuk, Turkey |

|

|

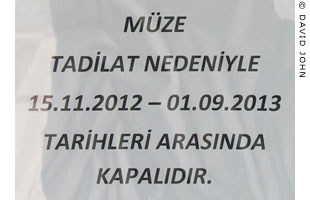

Ephesus Museum, Selçuk. Closed until September 2013, or posssibly much longer.

|

The Ephesus Museum

is closed for renovation

15 November 2012 - 1 September 2013

Update April 2014:

Reopening now scheduled for 6 July 2014

So, now you know.

There will be a lot of people turning up at the Ephesus Museum this summer only to be disappointed to find it closed.

This writer, for one, would have preferred to have been informed about the closure so that he could postpone his visit until the renovation was complete, and thus saved himself the time, money and frustration.

However, none of the official websites - the museum's own or those of Selçuk Municipality or the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism [1] - mention the temporary closure. There is no information about the renovation in the websites' "bulletins", "announcements" or "press information" sections.

Local tour operators and guides will have been informed of the closure or found out for themselves, but the independent traveller is left in the dark.

The same applies to several other museums and visitor attractions, including those in Kuşadası, Manisa and Miletus, which we look at below.

The Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism's curiously named subsidiary, the Central Directorate of Revolving Funds, is the body that "conducts the commercial activities of the Ministry, provides financial support to protect and improve the cultural entities and values, and raises funds for culture and tourism infrastructure investments and promotion activities". But its website, dosim.kulturturizm.gov.tr, makes no mention of the closures or renovations of the museums in Ephesus, Manisa or Miletus. Its list of state-run museums and archaeological sites, with admission charges, including the feature marking certain museums with "(x) Closed to visit because of restoration", is at least two years out of date.

Normally, organizations and ministries proudly announce their intentions to expand and improve such facilities and publish pretty architects' drawings of the projects; there is usually a lot of drum-banging about policies, strategies, investments, cultural promotion and the like. So why the curious silence about these places?

Turkish and foreign tourists may quite justifiably feel duped if they travel to a place to see a museum which is still being advertised as "kept open all year round", "365 days a year" and find it most definitely closed. For many visitors, particularly those from far-away places, this may have been the only opportunity to see this renowned collection of antiquities.

Ephesus is not a cheap place to visit: admission to the archaeological site now costs 25 Turkish Lira (around 12 Euros); the privately run Terrace Houses area within the site costs an extra 15 TL; the House of the Virgin Mary (Meryemana) also 15 TL; the Basilica of Saint John costs 8 TL; and before its closure a ticket to the Ephesus Museum was 8 TL. A typical visitor will therefore be paying as much as 71 TL (35 Euros) just in ticket charges on a day-trip [2]. It's an even more expensive business for families. Now multiply that by 20,000 - the estimated average number of visitors to Ephesus per day all year round - and, to paraphrase Paul Getty, it soon adds up to real money; and that is before you add the amounts visitors spend in hotels, restaurants, cafes, shops and hamams, and for buses, taxis, car hire, tours and guides.

According to ministry figures, Ephesus is the third biggest visitor attraction in Turkey, after the Hagia Sofia and Topkapı Palace in Istanbul, and in 2011 1,099,000 people passed through its turnstiles. In the same year the country's museums and historical sites received 28,462,893 visitors, a 13 percent increase on 2010 [3].

With all that revenue flooding into the public and private coffers of Selçuk, Ankara and other places, the authorities should have the decency to inform their customers about such changes to the availability of services.

This problem is by no means restricted to Turkey, as we shall see with the case of Polygyros in northern Greece. In Bulgaria I once paid for a ticket to enter a park which contained a historical site, but when I got to the entrance of the site it was closed. I and several other visitors were refused a refund or even an explanation for such a blatant rip-off.

The positive side of the closure of the Ephesus Museum is that its sorely needed renovation and expansion should allow for an improved presentation of the exhibits, which will hopefully include objects for which there was previously no space. The museum, founded in 1929 and enlarged in 1964, was last renovated and expanded in 1976, and like many museums around the world, was becoming outdated and cramped, with insufficient room for either newly discovered archaeological artefacts or the rapidly increasing number of visitors.

In May this year a large area immediately to the south of the existing museum building had already been cleared and foundations were being laid for the new extension (see photo below). Even given the speed with which modern buildings can be thrown up these days, I wonder if the planned reopening will take place on schedule in September.

Hopefully, I will have the chance of visiting the museum in the near future, a prospect I look forward to. My previous visits were very enjoyable. How much the new admission price will be is anybody's guess: mine is at least 10 TL, probably more like 15 TL. If you start saving now, you may just be able to afford to pay for all the tickets needed to visit Ephesus.

|

Ephesus Museum, Selçuk

Closed for renovation

15 November 2012 - 1 September 2013 |

| |

A marble hermeros (or hip-herm), a high

relief of Eros in the form of a herm, at the

entrance to the Ephesus Museum, Selçuk.

From a nymphaeum in Ephesus. Roman

period, 2nd century AD. Inv. No. 368. |

| |

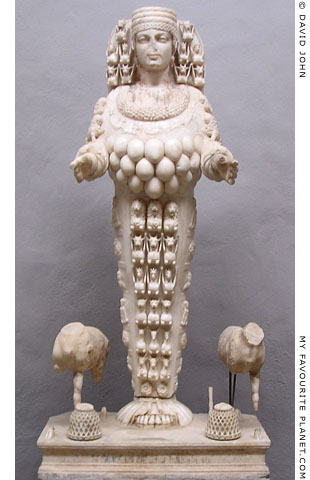

Statue of Ephesian Artemis, known as

the "Beautiful Artemis", 125-175 AD.

Ephesus Museum's most famous exhibit.

(Photo taken in 2004.) |

| |

My Favourite Planet has informative photo galleries for Ephesus, the Ephesus Museum and Selçuk. Admittedly, they could also do with a bit of renovation and expansion (the first versions went online in 2004), on which we shall start work as soon as we can find a sufficiently powerful pixeldozer. In the meantime the galleries will remain open - and free of charge.

Ephesus Museum notes

1. The website in English for the Ephesus Museum:

efesmuzesi.loriennetwork.com/en/museum

The museum's page on the Selçuk Municipality website:

selcuk.bel.tr/eng/selcuk.php?module=13

The museum's pages on Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism websites:

muze.gov.tr/ephesus

kultur.gov.tr/EN,34452/ephesus-museum.html

and

goturkey.com/en/pages/content/239

None of these webpages mention the museum's temporary closure or provide information about the renovation. These official sources can not even agree on museum opening times or ticket prices.

2. Admission to museums and archaeological sites in Turkey

There are discounts and free tickets for eligible categories of people such as students, children and accompanying teachers, senior citizens, soldiers, military veterans, journalists, etc.

See "Directive about the procedures and principles to be followed for admissions to museums and archaeological sites":

muze.gov.tr/Resources/ministerial_directive_eng_24_02_2012.pdf

Citizens of Turkey and Northern Cyprus, foreign residents and some foreign students can also take advantage of the credit card style Müzekart (Museum Card), costing 30 Turkish Lira, which allows free access for one year to museums and archaeological sites run by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Available to: "Turkish citizens, citizens of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, foreigners with Turkish residence permit, foreign students enrolled in associate degree, bachelor’s degree and master’s degree programs of higher education institutions in our country and students who are enrolled in universities in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus affiliated with the Council of Higher Education (Turkey) provided that they present university identification cards."

See: muze.gov.tr/museumcard_about

Museum Pass İstanbul, is available for everybody, costs 72 TL and is valid for 72 hours (3 days at 1 TL per hour), calculated from the first museum visit. It also provides discounts for private museums, museum shops and other venues.

Purchasers have to provide their own stamina and a good pair of shoes. The pass can only be used at each museum once, which is a pity, especially since the Archaeological Museums complex, consisting of three separate buildings, is huge and may take more than one visit to see its main attractions without dying of hunger, fatigue or sensory overload.

You would have to visit at least 10 Istanbul museums to make this pass pay its way (mosques, tombs and many churches are free anyway). Definitely a good gift idea.

Oh, and don't forget: nearly all museums in Turkey are closed on Mondays. Therefore starting your 72 hours on a Sunday is probably not a cost effective option.p

See: muze.gov.tr/museum_pass

A similar affordable card for Ephesus and Selçuk (or even the whole of Turkey - why not?) could well be a good idea for a government that is really commited to "protect", "improve" and "promote" "cultural entities and values". The same goes for London, Berlin, Paris, New York...

3. Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism visitor statistics for museums and historical sites.

See "2011 figures" at:

muze.gov.tr/announcements?type=2011-figures |

|

|

| |

The building site of the new extension to the Ephesus Museum, Selçuk, May 2013. |

| |

| |

Kuşadası, Turkey |

|

|

The Genoese fortress on Güvercin Ada (Dove Island

or Pigeon Island), Kuşadası. Closed for renovation.

|

Kuşadası? Museum? Surely not? Says nothing in my guide book about a museum here.

Well, apart from the Turkish habit of referring to historical sites as museums, the seaside resort town of Kuşadası does have a couple of ancient attractions, including the 13th century Genoese fortress, a couple of Ottoman mosques, a caravanserai (han) and Turkish baths (hamams). See the My Favourite Planet guide to Kuşadası for further details.

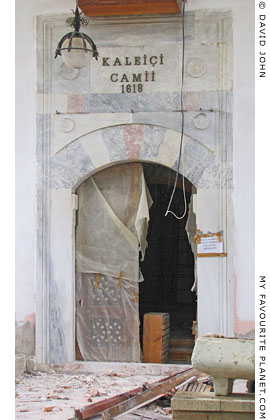

Kuşadası's historic buildings are not considered world class in terms of historical or architectural importance, and have hardly excited the interest of many historians or archaeologists; very little research has been published about the place, and the ancient Ionian settlement of Neo Polis has yet to be thoroughly investigated. However, the Güvercin Ada fortress and the early 17th century Kaleiçi Camii mosque are an important part of the port's character and it is good to see that some of the tourist money which pours into the area is being reinvested in renovating them. The Öküz Mehmet Paşa Han (caravanserai), built in the same year as the mosque and renovated in the 1960s, now houses the private hotel and restaurant Club Caravanserail.

That both fortress and mosque are being renovated simultaneously seems a bit of a puzzling planning decision. It may be a case of making hay while the financial sun shines, but it means that the two most important cultural tourism attractions in the town are presently closed.

Kaleiçi Camii is a working mosque used by local people rather than just a historical monument, and there is obviously local interest in seeing the renovation completed as quickly as possible. At the time of my most recent visit work appeared to be continuing steadily.

The fortress, on the other hand, has been out of bounds for over two years, and there seems to be no sign of when it will be completed or what exactly they are up to within the high walls. Once again there appears to be no published information about the work going on here. Perhaps the plans are posted in the basement of the town hall.

Has there been any new archaeological exploration on the island, and how interested are the renovators in preserving the historical authenticity of the structures? The walls themselves have been substantially cleaned and repaired, and gleam in the sunshine (not shown in Spring rainy-day photo above). One suspects that the old crumbling, makeshift look inside the fortress has been banished, along with the low-rent amenities: the restaurant, disco, flower garden, the rabbit enclosures and the pigeon temples on metal poles.

What marvels will eventually take their place

w i l l b e r e v e a l e d i n d u e c o u r s e . . . |

|

Kaleiçi Camii mosque, built in 1618

by Öküz Kara Mehmed Pasha,

in the old town of Kuşadası.

Currently undergoing renovation. |

|

| |

The renovators' scaffolding makes it look as if Kuşadası's

Genoese fortress is being besieged from within. |

| |

| |

Manisa Museum, Turkey |

|

|

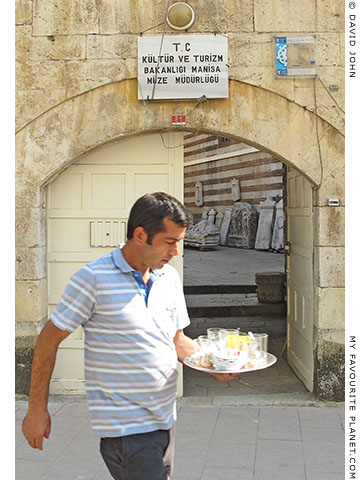

The (closed) entrance to the Manisa Archaeological Museum |

| |

I went to Manisa Museum but it was closed. Forever.

Another great travel plan bites the dust. Nobody tells me nothing. Having done quite a bit of research before setting off around western Turkey last year, it appeared that Manisa Archaeological Museum contained a huge variety of artefacts from Manisa province's ancient sites, notably Sardis, to which I was headed, and was housed in the extraordinary late 16th century Muradaiye Medresesi, part of the Muradiye Camii mosque complex, designed by the legendary Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan during the reign of Sultan Murad III. A must see, then, and well worth making a detour on my journey to Sardis.

The museum had a patchy reputation, having been closed following a coin robbery in 2000, and subsequently due to staff shortages (or some such). But it appeared to be open once more, was mentioned in several publications and had been visited recently by other travellers, allegedly.

Finding accommodation in the bustling city was not easy, as everywhere seemed to be booked out by students, businesspersons and even visiting sports stars. In the end I just rode into town and shamelessly blagged my way into a hotel room. It was expensive but good value, and I felt quite pleased with myself. But then my over-confidence started to falter slightly as I searched for the tourist information bureau. Various guide books and websites gave three different addresses for the local Directorate of Culture and Tourism's office. It appears to have been moved around several times in recent years, and nobody in Manisa knew where it had last landed.

The museum was relatively easy to find, and it was a good sign to find the entrance to the medressa open and the central courtyard furnished with the usual reliefs and sarcophagi which are left outside museums [1]. However, it appeared to be a case of one step forward two steps back when a security guard informed me that the museum was closed.

Luckily, at that moment Mr Sedat Türk, the new acting manager of the museum, happened to be crossing the courtyard. He was surprised to see a foreign visitor (I did not see a single tourist during my stay in Manisa) and took the time to explain that a new museum was being built and was due to be opened in 2014-2015. He gave me an interview, tea and a quick private tour of the old museum in the medressa's former imaret (soup kitchen for students and the poor).

And, indeed, there are some marvellous objects hidden within the ex-museums walls. Among the 32,000 archaeological finds are a forest of statues and reliefs, and many Greek and Roman inscriptions, some of which have not yet been thoroughly studied. On the other side of the entrance courtyard, a glass-walled gallery around an inner courtyard houses yet more sculptures and mosaics, as well as a small ethnographic museum - still open to the public - and the administrative offices.

It was easy to see the need for a new museum to house all those exhibits. The medressa itself is an architectural gem, first opened as a museum in 1935, having been previously used to house poor people and immigrants from Greece following the forced population exchanges of 1923. It now looks in dire need of renovation, and it would have been inappropriate to alter it in order to meet the requirements of a modern museum, such as lighting, security and environmental controls. As can be seen in the photo above, the building has already suffered insensitive ad-hoc repairs to the pointing of the stone work and clumsy installation of electrical cables.

Mr Türk told me that the new museum was being built just outside the city centre, near the main highway. He and other members of the new staff, including archaeologists, have been brought from Pergamon to prepare the museum's inventory for eventual installation in the new museum. Quite a challenging task, especially as, at the time of my visit, a new museum director was still to be appointed.

He also pointed me in the right direction for the tourist information office. The staff there were also surprised to see a foreigner - a rare species in these parts, apparently. However, they were very friendly and helpful, and showed me the new exhibition of local crafts they were preparing, including an ambitious audio-visual presentation.

Those interested in ancient history may also be disappointed to learn that there is nothing to be seen of the Lydian city of Magnesia ad Sipylum, "the city of Tantalus", the remains of which are thought to lie beneath modern Manisa and around the hillside Byzantine castle today known as Sandıkkale (Dowry-Chest Castle). The only surviving ancient monument is "the Weeping Rock of Niobe" (Niobe Ağlayan Kaya, see the Niobe page in the MFP People section) on the southern edge of the city, next to a modern open-air theatre at the foot of Mount Sipylus (Sipil Daği). At Akpinar, 7 km southeast of Manisa, is the Taş Suret, a Hittite relief of the mother goddess, known to the Greeks as Kybele (Cybele), carved into a rock face below the mountain. |

A marble relief of a Roman eagle, from Sardis.

One of a pair used during the Roman Imperial

period to support a table in the ancient city's

synagogue. They currently flank the doorway

to Manisa's old Archaeological Museum

(see photo above and note 1 below). |

| |

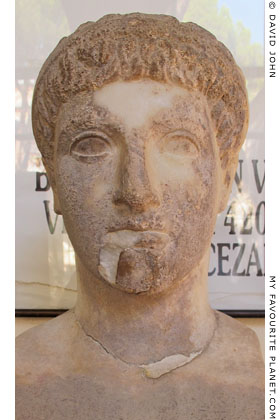

Head of a herm in the old Manisa Museum.

See more about herms on

Pergamon gallery 2, page 15. |

| |

Tea time at the Muradaiye Medresesi in Manisa. |

| |

Manisa itself is a pleasant, fast-growing modern city, with several Ottoman monuments, including imperial mosques of the 14th to 17th centuries, a 14th century Mevlevi Dervish lodge, türbes (Ottoman tombs), a large hamam and a caravanserai (han) now used as a crafts bazaar.

I did not attempt to visit the construction site for the new museum, by this time I had already seen enough of building sites. Subsequent searches for news of the new museum's progress have only revealed information about an enormous municipal centre being built in Manisa. No mention of a museum there, but perhaps it will be a part of this new complex.

If you have any news about Manisa's new Arkeoloji Müzesi, we would love to hear from you.

Please get in contact.

Manisa Museum notes

1. I often wonder why so many museums leave ancient artefacts outside, at the mercy of the weather, environmental pollution and pigeons. Mostly the sarcophagi, reliefs, inscriptions, architectural elements and headless statues are not even labelled or mentioned in catalogues or guidebooks. It is understandable that many are too large to fit into a museum, but often they are uncared for and just left to rot. Although they may be considered less interesting than a museum's star attractions, many are fascinating objects for which other museum directors would give their eye teeth.

Why for example, were the eagle reliefs (photo above right) removed from their historical context in the synagogue at Sardis, where they have been replaced by replicas, if they were destined to stand outside Manisa Museum as mere decoration? |

|

|

| |

The inner courtyard of the old Manisa Archaeological Museum, in the Muradaiye Medresesi. |

| |

"The exhibition at this window is temporarily disabled"

The collection of Roman coins at Izmir Museum of History and Art (Izmir Tarih

ve Sanat Müzesi), Izmir, Turkey, temporarily removed from its display case.

|

Sometimes exhibits are removed from museums to be cleaned, restored, photographed or studied by specialists. More often they are loaned to other museums or sent on tours for special thematic exhibitions. Museums earn much needed revenue and attention from such loans, and the transactions also help foster important relationships between the staff and experts in various fields in distant cities and countries.

Such activities and transactions are important to running museums and improving knowledge about the exhibits and the contexts in which they are displayed. The problem for the public is that they usually do not know that often important exhibits have been removed and are then disappointed to find objects they have come to the museum to see are not there. Of course, this is not nearly as bad as the entire museum being closed, but still ... |

|

|

| |

| |

Miletus, Turkey |

|

|

The new Archaeological Museum of Miletus - still not open.

|

In 2011 it was widely reported that the new archaeological museum of Miletus (or Miletos; Greek, Μίλητος; Latin, Miletus) was now open. See, for example "Turkey renovates museums", from a press release of the official Anatolia News Agency (Anadolu Ajansı), published by Hurriyet Daily News, 29 November 2011. [1] This story was still getting mileage at the end of 2012, being repeated on various websites, some even showing photos of ancient artefacts purportedly taken in the new museum.

However, when I visited Miletus in May 2013, I was told that the museum was still not yet finished, and nobody knew when it would be opening. Very curious.

Since then I have been unable to find any more up-to-date information concerning the museum, even from official Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism sources. Curiouser and curiouser. I did not even see any road signs indicating the existence of the museum, although it can be seen from the archaeological site, hiding among the trees to the southwest.

Miletus is not an easy place to get to, especially outside the summer season, as there are very few buses (or rather dolmuş minibuses) bound for the nearby village of Balat, and none at all after 12 noon. The next reliable dolmuş connection with Söke (the nearest town and public transport hub, 36 km north) is at the village of Akköy, 5 km to the south. The options are walking, hitch-hiking (although there is very little traffic along this minor road), or accepting the offer of a lift (for a small consideration of around 15 TL) from one of the local gentlemen at the site. [2]

While the archaeological site is moderately interesting (excellent theatre), anybody who has read the reports about the new museum and travels there expecting to see wonderful the sculptures, reliefs, mosaics and other finds which have been hidden from public view for many years is going to be sorely disappointed.

What is going on here? One would have expected that, having paid so much money to build a new museum at such an important ancient site, the responsible authorities would have made more effort to promote and publicize its existence. As at Ephesus, Kuşadası and Manisa, the silence concerning renovations and new museums is deafening.

Once again, if you have any news about the new Miletus Archaeological Museum, please get in contact.

You can see some photos of Miletus plant life in The Cheshire Cat Blog Ionian spring part 2, and its animal life in Ionian spring part 3.

Miletus Museum notes

1. The same press release stated that in 2011 Turkey had 189 museums, 141 tombs and 131 ruins open to visitors, and that the Ministry of Culture and Tourism had plans to open or reopen another 8 museums by the end of the same year.

2. From Akköy you can catch a dolmuş minibus to the archaeological site of Didyma, a further 15 km southwards. Until recently, the archaeological finds from Miletus had been displayed in a museum in Didyma since 1973. There does not seem to be any sign that this older museum is still open.

If you can get to the village of Güllübahçe, near the site of Priene, 22 km north of Miletus, there is also a frequent dolmuş service to Söke, with connections to Kuşadası and Izmir. |

"Miletus ruins". Yes, but what, or whom? |

| |

Relief of Helios-Serapis at the

3rd century AD Serapeion in Miletus. |

| |

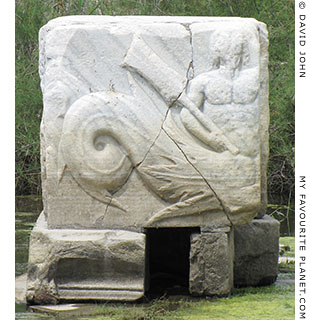

Relief of a triton from the 1st century BC

Harbour Monument in Miletus. |

| |

| |

The ruins of an Ionic stoa, 1st century AD, in the waterlogged site of ancient Miletus. |

| |

| |

Polygyros, Halkidiki, Greece |

|

|

Construction work on the new archaeological museum in Polygyros, Halkidiki, northern Greece.

|

And so I arrive in Polygyros, the small town which serves as the administrative capital of the regional unit of Halkidiki, Macedonia, northern Greece. And yes, the museum is definitely closed.

After visiting ancient Stageira, near the village of Olympiada on the north-eastern coast of the Halkidiki peninsula, and several other historical sites in the area, I had been looking forward to seeing the local archaeological finds in the Polygyros Museum. Tough luck.

Halkidiki is also not the easiest place to get around by public transport, i.e. buses. As with many places in Halkidiki, there is no direct connection between Olympiada and Polygyros. It is yet another "you can't get there from here" scenario. To travel from village A to village B, you often have to go via Thessaloniki, the local transport hub, so that a journey which should take 45 minutes, can take up to 5 hours. Bus schedules and information about routes are as rare as hen's teeth, and the Thessaloniki bus station which serves Halkidiki (KTEL Chalkidikis bus station) is a long way from the city centre and other transport connections (see How to get to Macedonia, Greece).

It almost goes without saying that Olympiada is served by a different bus company at yet another of Thessaloniki's bus stations (see How to get to Stageira and Olympiada).

But I finally get to Polygyros, and there I am once more, watching a man operating a mechanical digger rather than gazing at an Archaic sculpture or a Hellenistic trinket.

Once again I had trusted to what turned out to be misleading and outdated information. Once again I could not find out much more at the place itself. A construction worker told me that the museum was scheduled for reopening at the end of 2013, but he could not be more specific, and did not sound too convinced about it himself. As at the Ephesus Museum, workers here were still at the stage of preparing the foundations for the new extension (see photo above).

A visit to the friendly people at the town hall revealed... nothing new. I had also read that there was an ethnographical (or folklore) museum in Polygyros. My queries about this were met first by blank looks, as if they had never heard of such a thing, and then, after a bit of internal phoning, I was told that this museum too was closed, although nobody actually knew where it was or had been. I left the municipality's nerve centre with yet another expensively-printed colour brochure about the charms of Halkidiki, this one entitled "Halkidiki - inside your dreams", with the contradictory subtitle "Dream not - Go Live!" Naturally, it lists the archaeological and folklore museums among the attractions of Polygyros.

Still, Polygyros is in itself an attractive town, I had an excellent lunch in a garden restaurant in the shade of plane trees, the bus rides there and back through the Halkidiki countryside were very pleasant, and I met a friendly Italian couple on their way to what sounds like an idyllic seaside village. Next time I'll go there, and sod the closed museums of this world.

I did later find an online notice at odysseus.culture.gr informing the public about the temporary closure of "Archaeological Museum of Poligiros", but I had to trawl the internet for quite a while before stumbling upon it. There was silly me looking for "Polygyros", which is how the name is usually transliterated from the Greek Πολυγύρος.

Odysseus is an official website run by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and while it does feature a lot of information about Greece's museums, monuments and sites, much of it is incomplete or out of date, or in Greek only, and often the site is unavailable. Instead of summarizing information about a museum on a single page, users have to click between pages marked "Description", "History", "Exhibitions" and "Information", which often contain only the words "The description is not available". This means that the site is often ignored by search engines and users such me, who do not have time to navigate through empty pages.

The info is there, albeit in the website's virtual basement, and that's more than can be said for a host of other "authoritative" sites and publications, official or otherwise. Instant communication sometimes takes forever. |

The Polygyros Archaeological Museum

is closed due to renovation.

Well, what else would you expect? |

| |

UPDATE 2019

Polygyros Archaeological Museum

finally reopens

On 24 March 2019 an exhibition of part

of the Ioannis Lambropoulos Collection

of local ancient artefacts was opened

at the museum. It is hoped that the

number of objects on display can

be expanded by 2020.

See Polygyros gallery page 1 |

| |

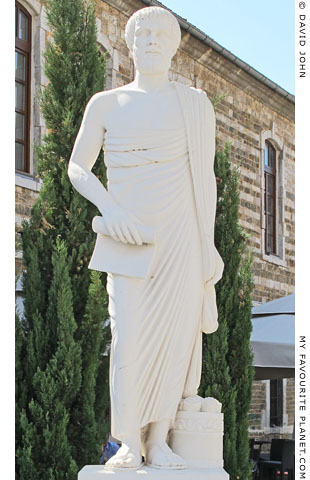

A modern marble statue of Aristotle by

A. Alexiades outside Polygyros Town Hall. |

| |

| |

I think they, and I, have made the point. |

| |

The Town Hall (Dimarcheion) of Polygyros |

| |

Articles and photos copyright © David John 2012-2013

Additional photos © Konstanze Gundudis

The Cheshire Cat Blog at My Favourite Planet Blogs

We welcome considerate responses to these articles

and all other content on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact.

The photos on this page are copyright protected.

Please do not use them without permission.

If you wish to use any of the photos for your website,

blog, project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr |

| |

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de |

| |

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr |

| |

| |

|