|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

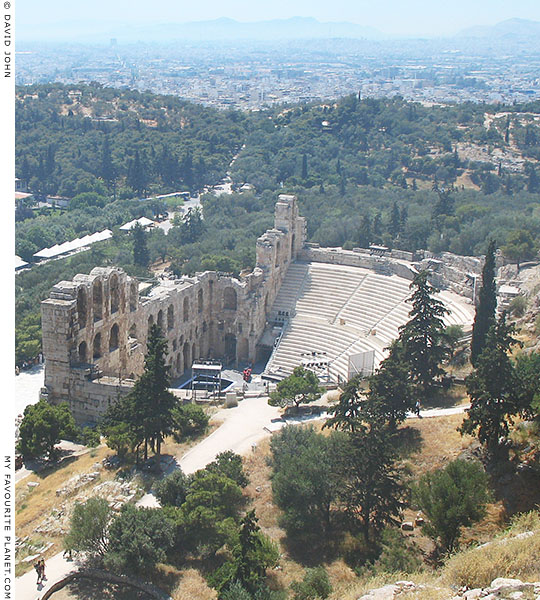

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus from the south wall of the Acropolis |

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus

part 1 |

| |

In the photo above, immediately beyond the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, a row of white tents of a book fair stretch along the pedestrianized Dionysiou Areopagitou Street, on which are the entrance to the Odeion and the Theatre of Dionysos and the footpath to the Acropolis entrance.

Immediately above the Odeion runs the Peripatos, the circuit path around the foot of the Acropolis (see gallery page 34 and gallery page 5). Steps to the east (left) of the Odeion lead up from the Peripatos to the top of the Acropolis.

Philopappou Hill, in ancient times known as the Museion or the Hill of the Muses, rises from the opposite side of the street. The ruin of the Philopappos Monument can be seen standing on the top. In the background the urban sprawl continues to Piraeus and Faliron (Phaleron) and the Saronic Gulf; beyond are the mountains of Salamis island (Salamina) and the Peloponnese. |

|

|

| |

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus. |

| |

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus (Ωδείο Ηρώδου του Αττικού) [1], at the foot of the southwest slope of the Acropolis, is named after the wealthy and influential Herodes Atticus [2], who financed the building of this theatre around 160-174 AD. It was one of the last major public buildings to be constructed in Athens in antiquity.

The grand marble ampitheatre is also referred to as the Herodeion (Ἡρώδειον), the Regillum or Odeum of Regilla, as Herodes Atticus dedicated it to his wife Aspasia Annia Regilla, who had died in 160 AD. [3]

It was built of Piraeus limestone, clad with marble, and had a cedar wood roof [4]. The 81 metre wide, semi-circular cavea (audience seating area) is supported by a massive buttressed wall, for which the surrounding natural rock was cut away. It has been estimated that the seating capacity was 5,500. [5] The orchestra, the floor used as a performance area (stage), is 21.4 metres wide.

The three-storey skene (or scaena, the building behind the stage), which is today the facade of the building, was 28 metres high, built of massive limestone blocks and had rows of tall, deep arched niches in which stood statues (see illustrations on the next page). The surviving part of the skene stands in some places up to the second storey, and today forms the facade of the Odeion, one the most distinctive architectural forms in Athens. The enormous entrance portico which projected from the skene has not survived, although parts of its mosaic floor have been found.

See more about the Odeion's facade, as well as a reconstruction drawing and plan on the next page. |

|

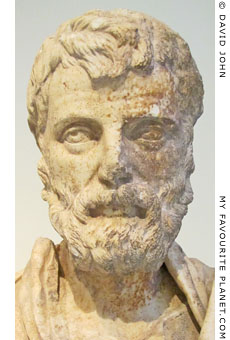

Portrait bust of Herodes Atticus

from his villa in Kifissia, north-

east of Athens. Pentelic marble,

mid 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4810.

|

|

| |

The interior of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus with its restored seating.

|

Pausanias, the second century AD Greek travel writer, considered the Odeion to be the finest in Greece, athough he may never have actually seen it, since, as he himself writes, it was built after his stay in Athens. [6]

By the 17th century, when northern European travellers such as Jacob Spon and George Wheler [7] visited Athens, the Odeion was already in ruins. In the mid 18th century James Stuart and Nicholas Revett [8] reported that the interior of the building was covered in soil from which barley was grown to feed the horses of the Disdar Aga, the Turkish military commander of the Acropolis (see illustration below).

The floor of the Odeion had been filled with high with several tons of soil in 1060, during the Byzantine era, when it was converted into part of the fortifications around the foot of the Acropolis, known as the "Rizokastron", which included a massive surrounding wall (see illustration below). The fortifications were rebuilt and modified several times, including the construction of the Ottoman "Serpentzes" wall in 1687. Parts of ancient monuments were commonly used as building material, and marble was reduced to lime for cement. All the Medieval and later fortifications were demolished in the mid 19th century as part of the excavation works at the Acropolis. Over the centuries much other debris had also fallen into the Odeion from further up the slope.

The Theatre of Dionysos had become completely buried, with only a slight depression in the earth to betray its presence. Most foreign visitors, including Spon, Wheler, Stuart and Revett, took it for the site of the Odeion of Pericles, and thought that the Odeion of Herodes Atticus was the "Dionysiac Theatre". [9] It was only in the late 18th to the early 19th century that Dr Richard Chandler and Colonel William Martin Leake, having studied the works of previous travellers, ancient authors and more recent information on ancient monuments, carefully studied the area and were able to recognize the individual sites. [10]

Work to clear away the soil and debris in and around the Odeion began in 1848 under the auspices of the Archaeological Society of Athens (founded 1837), their first excavation. Excavations continued in 1857-1858, supervised by Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis (1798-1863). Pittakis discovered that the marble of the building was severely calcified and found a one meter deep layer of wood ash and charred roof tiles in the cavea, [11] which has been taken as evidence that the theatre did have a wooden roof, and that it was destroyed by fire, probably during the attack on Athens by east Germanic Heruli tribe in 267 AD. [12]

The find of a large quantity of murex shells, also unearthed during excavations, suggests that purple dye (Tyrian purple) was produced here in Byzantine times.

Further studies of the Odeion were made in 1861 by German architect W. P. Tuckermann (1840-1919, see next page), and in 1910 by Piraeus-born archaeologist Friderikos Versakis (1880-1921) of the Greek Archaeological Service. [13]

Professor Anastasios Orlandos (1887-1979) resumed archaeological investigation of the Odeion after World War II, and it was restored 1950-1961. The seating was reconstructed in Pentelic marble and the orchestra repaved with blue and white slabs. Further refurbishment has recently been undertaken during the general restoration work on and around the Acropolis. The auditorium now seats 5000 spectators, and in summer the theatre hosts world class plays, concerts and dance performances.

Events at the Odeion are part of the annual Athens and Epidaurus Festival.

See: www.greekfestival.gr/en/ |

|

|

| |

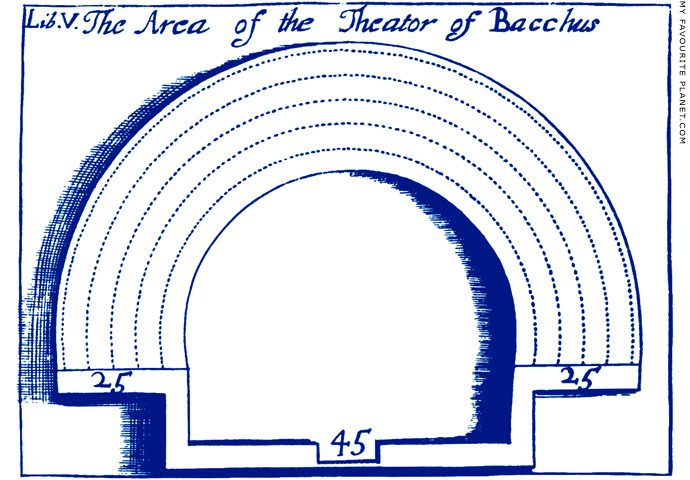

Jacob Spon and George Wheler's plan of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus,

which they mistook for "the Theatre of Bacchus" (the Theatre of Dionysos).

|

Despite Spon and Wheler's pioneering and painstaking attempts to study and measure ancient monuments during their stay in Athens in 1676, the results seem very disappointing by modern standards. They worked under difficult conditions, and neither of them were trained draughtsmen or architects. The illustrations which appeared in their books relating their travels together through Italy, Turkey and Greece are crude and inaccurate, and Wheler appears to be admitting his deficiencies in drawing when describing the caryatid he and Spon saw at Eleusis (see Demeter): "I designed the statue perhaps well enough, to give some rough imperfect idea of it; but not to express the exquisite beauties of the work." (A journey into Greece, page 428).

Still, their efforts were not in vain, and their sketches and descriptions provided sufficient material for renewed debate and curiosity about ancient Greek history and art for the next century, and a starting point for those who were to follow in their footsteps.

Image source: George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book V, page 365. Cademan, Kettlewell, and Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks. |

|

|

| |

Nicholas Revett (right) sketching in the ruins of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus during his stay

in Athens with James Stuart 1751-1753. [8] Turks exercise horses in the overgrown auditorium.

|

Like other early modern visitors to Athens, Stuart and Revett mistook the Odeion for the Theatre of Dionysos, the location of which was unknown as it had become completely covered with earth.

"The front of the scene occupies the principal part of this view ; the area, in which were the feats of the spectators, neglected for ages, has at length acquired a surface of vegetable earth, and is now annually sown with barley, which, as the general custom here is, the Disdar-Aga's horses eat green [14]; little or no grass being produced in the neighbourhood of Athens.

The foreground is a recess, or little grotto in the upper part of the Theatre, whence this view was taken. Here Sir G. Wheler imagines, not improbably, a tripod was placed, on which was wrought the story of Apollo and Diana, slaying the sons and daughters of Niobe. [15] In this place I have endeavoured to represent my companion Mr. Revett, who from hence did, with great patience and accuracy, mark all the masonry in the front of the Scene."

"In the distant horizon appears part of the Sinus Saronicus, or gulph of Athens, and the mountains near Hermione and Troezene, in the territory of Argos; at the extremity of these mountains is the promontory Scyllaeum, and the island Calaurea in which Demosthenes died. Nearer is a part of the Attic shore about Aexone, now Hassane, maintaining still its ancient reputation for red mullets.

Just over the cypress tree, on the right hand, is the Monument of Philopappus; the hill on which it stands is now called To Seggio, but anciently the Museum, from the Poet Musaeus, who Pausanias informs us was buried there; and that on the place where his sepulchre had been built, the monument of a Syrian (evidently Philopappus) was afterwards erected."

James Stuart, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter III.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter III, Plate I. John Nichols, London, 1787. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

| |

Stuart and Revett's cross-section of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, showing the depth of soil and debris.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and

delineated, Volume IV, Chapter V, Plate VI. J. Taylor, London, 1816. At the Internet Archive.

See also 19th and early 20th century plans and reconstructions of the Odeion on the next page. |

| |

Watercolour of the west of the Acropolis, seen from the Pnyx,

before 1836 *, by William Page (1794-1872).

|

The painting shows the Medieval and Ottoman fortifications and the Odeion of Herodes Atticus (centre). The tall 14th century Frankish Tower, built by the Florentine Duke of Athens, Nerio I Acciaioli, dominates the Acropolis itself. Heinrich Schliemann financed the demolition of the tower in 1874, during the restoration of the Acropolis.

* This painting has been dated to "around 1840", which may be the year when it was completed, perhaps from studies made earlier. However, by 1836 many of the Medieval and Turkish fortifications, particularly those around the Propylaia and the Temple of Athena Nike, had already been demolished by archaeologists and architects during restoration works (see the illustrations on gallery page 12).

To the left of the Odeion can be seen a walled Turkish cemetery, in which there was a ruined church. James Stuart described the buildings around the cemetery as "Turkish sepulchres" (tombs). See Stuart's view of this scene on gallery page 1.

Edward Dodwell, visiting Athens in 1801, remarked of the Turkish cemetery:

"Here are several fragments of columns, architectural decorations, and mutilated inscriptions; with some fine ancient sarcophagi of white marble, upon which Turkish artificers have exercised their ingenuity.

We may here also remark some small buildings with cupolas, which, as I imagine, contain the remains of Mohamedan saints; the principal one is called Kara-Baba [literally, Black Grandfather]; and a Turk very gravely assured me, that on certain occasions they placed a supper before the tomb of the saint, which was consumed before the following morning." [16]

On the right of the picture stand the surviving columns of the Temple of Olympian Zeus. In the background, the peak of Mount Lykavittos is on the left, and Mount Ymittos (Hymettos) is on the right.

The track running behind the two figures in the foreground has become the modern Dionysiou Areopagitou Street, which becomes Apostolou Pavlou Street, running between Hadrian's Arch and the district of Thission. The path leading northwards from it follows the same route as today's footpath up to the entrance of the Acropolis. |

|

|

| |

Odeion of

Herodes Atticus |

Notes, references, links |

|

|

1. Odeion or odeum - the singing place

The word odeion (or odeon; Greek, ᾠδεῖον or ᾠιδεῖον; Latin, odeum) derives from the Ancient Greek ᾨδεῖον, Ōideion, singing place; from the verb ἀείδω, aeidō, I sing, and the nouns ᾠδή, ōdē, song or ode, and ἀοιδός, aoidos, singer. The ending -εῖον, -eion, is a suffix denoting a place.

Odeions in the Greek and Roman world were areas, and later buildings, where songs, music and poetry were performed, often in competitions. The distinction between an odeion and a theatre (θέατρον, a place for beholding; used for dramatic performances, and in Roman times for spectacles and bloodthirsty sports) is debatable, particularly as ancient authors refer to odeions, including the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, as theatres (see quote by Philostratus below).

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus was the third odeion built in Athens, after the Odeion of Pericles (next to the Theatre of Dionysos) which was restored by Herodes Atticus although no remains have survived, and the Odeion of Agrippa, in the Ancient Agora.

See: George C. Izenour, Roofed theaters of classical antiquity. Yale University Press, 1992.

Preview at googlebooks.

Here is a description of the Odeion from the late 19th century:

"Its seats were divided by one precinction (diazoma); the lower tier had twenty rows divided into five cunei, the upper, which is in great part destroyed, about thirteen, divided into ten cunei. The height of the seats is 1 ft. 5 in., and in profile they resemble those of the Dionysiac theatre. The seats of the lower tier were seats of honor, with backs.

A gallery ran round the top, enclosed by a massive semicircular wall of Piraic stone, on which the roof rested.

The orchestra, rather more than a half circle, is paved with rectangular slabs of different colored marbles. At either side are exit-passages (parodoi) along the stage-wall, leading down by easy steps to doorways opening upon vestibules through which one can pass out to the south.

The stage is about 115 ft. long and 26 ft. deep, and is raised 5 ft. above the orchestra, with which it communicated by two flights of steps. The front wall of the stage was ornamented with slabs and mouldings of marble.

In the rear wall of the stage are three doors, the side doors flanked by arched niches for statues. A row of columns about 17 ft. high ran across the width of the stage. Upon their entablature probably stood a second row of smaller columns, in front of the seven arched windows of the second story. Above, some remains survive of a third storey, also with windows.

In each wing of the building in the second storey are two vaulted rooms, communicating with the orchestra, the stage, and the precinction of the auditorium. The most eastern of these rooms opened directly upon the great stoa or portico connecting the Odeum and the Dionysiac Theatre.

The exterior face of the back wall of the stage bears also six niches for statues. The exterior wall of the two wings is plain below, and shows two upper tiers of arched openings, as high as the uppermost seats of the auditorium.

The masonry of the building is very fine and massive, the stone blocks large, and the joints carefully cut and fitted."

William P. P. Longfellow (editor), A cyclopaedia of works of architecture in Italy, Greece and the Levant, pages 35-36. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1895. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

2. Herodes Atticus

For further information about Herodes Atticus, his family, monuments and building works, see the Herodes Atticus page in the MFP People section.

Lucius Vibullius Hipparchus Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes (Ἡρῴδης ὁ Ἀττικός, circa 101-179 AD), a rich and cultured Greek aristocrat, born in Marathon, whose family claimed ancient and distinguished Athenian lineage.

He was elected Agoranomos (official who controlled the marketplace) around 122-125 AD, Archon of Athens in 126/127 AD, was appointed prefect of the free cities of Asia Minor in 134/135 AD by Emperor Hadrian, and served as a Roman senator and as consul ordinarius in 143 AD. He also served as agonothetes, a presiding officer, at the Panhellenic and Panathenean games (see below), and was a priest of the Roman imperial cult.

He was also a Sophist philosopher, orator and teacher; he taught the adopted sons of Emperor Antoninus Pius, who were later to become emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

He returned to Athens towards the end of his life, and as well as writing and teaching philosophy and rhetoric, he also financed public games and building works, including the Odeion, the renovation of the Classical Odeion of Pericles (which was next to the Theatre of Dionysos) and the Panathenaic Stadium (see photo below), in which his funeral was held.

While prefect in Asia he also financed or part-financed many public works, at Nicomedia, Nicea, Prusa, Claudiopolis and Sinope, as well as an extensive aqueduct in Alexandria Troas, said to have cost seven million drachmes (Philostratus, page 143 *). He also built monumental works at Olympia, Delphi, Corinth, Thermopylae and Canusium (Italy).

According to Philostratus, his greatest unfulfilled ambition was to complete the canal across the Isthmus of Corinth:

"And yet, though he had achieved such great works, he held that he had done nothing important because he had not cut through the Isthmus. For he regarded it as a really brilliant achievement to cut away the mainland to join two seas, and to contract lengths of sea into a voyage of twenty-six stades. This then he longed to do, but he never had the courage to ask the Emperor to grant him permission, lest he should be accused of grasping at an ambitious plan to which not even Nero had proved himself equal."

Philostratus, page 151 *

In his final years he spent much of his time at his estates at Kifissia (now a wealthy suburb northeast of Athens), Marathon and Loukou (ancient Eua, Εύα, Arcadia), where he had richly-appointed villas.

Herodou Attikou Street (Οδός Ηρώδου Αττικού) in central Athens is named after him, and Regilles Street and Square (Οδός Ρηγίλλης, often written Rigillis; the square is also known as Platea P. Mela) are named after his wife Aspasia Annia Regilla. The streets run parallel to each other, just east of Syntagma Square and the National Garden, an affluent area in which are located the residences of the president and prime minister of Greece, the barracks of the Evzone guards and the Athens Conservatory, as well as the archaeological site of Aristotle's Lyceum (see Digging Aristotle, The Cheshire Cat Blog).

* Quotes and references concerning Herodes Atticus and the Odeion by Philostratus are taken from:

Philostratus and Eunapius; The lives of the Sophists, Philostratus, Book II. In ancient Greek and English, translated by William Cave Wright. Heinemann, London and Putnam, New York, 1922. At the Internet Archive.

See also:

Joseph L. Rife, The burial of Herodes Atticus: Élite identity, urban society, and public memory in Roman Greece. Journal of Hellenic Studies, Volume 128 (2008), pages 92-127. At jstor.org.

Jennifer Tobin, Some new thoughts on Herodes Atticus's tomb, his stadium of 143/4, and Philostratus VS 2.550. American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 97, No. 1 (Jan., 1993), pages 81-89. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Frederick William Faber, A biographical notice of Atticus Herodes, prefect of the free cities of Asia. Davison, Simmons, 1832. E-book at googlebooks.

To modern readers this may seem more like an uncritical sermon in praise of Herodes Atticus than a historical appraisal of his life and achievements.

While researching these articles, I found the following whacky description of Herodes Atticus on a website:

"... the Rockerfeller of his day, Herodes Atticus, whose life reads like something out of the Arabian Nights." |

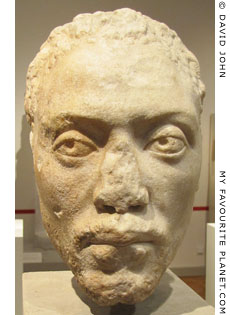

Portrait head of Memnon (Mέμνων).

After the death of his own children,

Herodes Atticus adopted three of

his pupils, including Memnon, an

Ethiopian. He set up portraits

of his adopted sons in his villas.

Marble. 160-165 AD.

From Loukou, Arkadia, Greece.

(see also photo below).

Altes Museum. Berlin. Sk 1503. |

| |

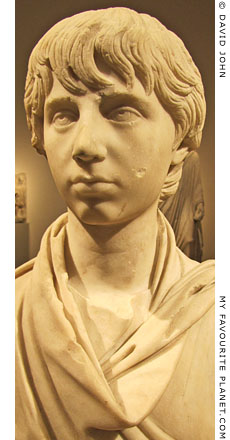

Bust of Polydeukes (Πολυδευκης),

another of Herodes Atticus'

adopted sons, thought to have

been his lover, who died young,

around 173-174 AD. After his

death, Herodes founded a cult

to him, similar to that created by

Emperor Hadrian for Antinous.

Several portraits of Polydeukes

have been found at Herodes'

villas (see also photo below).

Marble. Around 165 AD.

Acquired in Athens in 1844.

Altes Museum. Berlin. Sk 413. |

| |

Statuette of Artemis Ephesia, patron goddess of Ephesus,

found at the Villa of Herodes

Atticus in Loukou, Arkadia in

the Peloponnese, where much

of his large art collection has

survived, including 100

sculptures, several inscriptions,

mosaics and other works, many

of which are now in the Astros

Museum (currently closed).

Astros Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese. |

| |

| |

A marble epistyle from a building in Athens with two dedicatory inscriptions

for Herodes Atticus and his second daughter Claudia Athenais by the Council

of the Areopagus, Council (βουλὴ, Boule) of the 600 and the Assembly of the

People (δῆμος, demos). Before 150 AD.

|

ἡ είου πάλὴ καὶ ἡ βουλὴ τῶν ἑξακοσίων καὶ ὁ δῆμος Κλαυδίαν Ἀθηναΐδα εὐεργεσίας ἕνεκεν.

ἡ ἐξ Ἀρείου πάγουλὴ καὶ ἡ βουλὴ τῶν ἑξακοσίων καὶ ὁ δῆμος τὸν ἀρχιερέα τῶν Σεβαστῶν διὰ

βίου Τιβ Κλαύδιον Ἀττικὸν Ἡρώδην Μαραθώνιον εὐεργεσίας ἕνεκεν.

Marcia Annia Claudia Alcia Athenais Gavidia Latiaria, commonly known as Athenais (143-161 AD),

was Herodes Atticus' third child and second daughter.

Athens Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 10313. Inscription IG II (2) 3594 / 5. |

|

| |

Marble relief in the form of a naiskos (small temple), depicting a naked youth,

identified as the heroized Polydeukes, adopted son of Herodes Atticus

(see above). Typical of such hero reliefs, he is shown with a horse.

To the left is a tree, around which is entwined a snake, armour and a sword.

On the right is a slave holding his helmet and a loutrophos (a tall vase used

as a grave marker) on a pedestal.

Pentelic marble, after the middle of the 2nd century AD.

Found near the Monastery of Loukou, Arkadia.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1450.

Herodes Atticus' villa at Loukou contained a large art collection. Over 100 sculptures,

several inscriptions, mosaics and other works from the villa are now in the nearby

Archaeological Museum of Astros (unfortunately closed for many years).

See more portraits of Polydeukes on the Herodes Atticus page in the MFP People section.

Read more about hero reliefs on Pergamon gallery 2, page 10 and Pella gallery page 17. |

|

3. Aspasia Annia Regilla

For further information about Annia Regilla and her children, see the Herodes Atticus page in the MFP People section.

Appia (or Aspasia) Annia Regilla Atilia Caucidia Tertulla (158/160 AD; known in Greek as Ἀσπασία Ἄννια Ῥήγιλλα, Aspasia Annia Regilla), to whom the Odeion was dedicated, was the wife of Herodes Atticus. A member of an influential Roman aristocratic family and distantly related to the imperial line, she was married to Atticus when she was about 14 and he was about 40. Of the six children they are known to have had, only three survived into adulthood.

She was the priestess of Demeter at Olympia, the only woman allowed to attend the Olympic Games, and built the Nymphaeum, a monumental fountain (also known as the Fountain or Exedra of Herodes Atticus) decorated with statues of Zeus, members of her and Atticus' families and the imperial family. The fountain also featured a marble statue of a bull, now in the Olympia Museum, on the side of which a Greek inscription proclaims: "Regilla, priestess of Demeter, dedicated the water and the fixtures to Zeus."

Among her other distinctions, she was also the first priestess of Tyche (Τύχη; Latin, Fortuna) in Athens, probably at the temple of Tyche built by Atticus near the Panathenaic Stadium. A statue of her was dedicated by the traders of Piraeus at the request of the Areopagus. No surviving sculpture head or bust can be definitely identified as a portrait of Regilla, although a now headless statue from the Nymphaeum in Olympia is thought to have depicted her.

During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Atticus was accused of murdering Regilla by her brother Appius Annius Atilius Bradua, who was at the time Consul. At the trial in Rome it was alleged that she died in premature childbirth after being kicked in the stomach by a freedman of Atticus while she was eight months pregnant with her sixth child. (Philostratus, pages 159-163 *) It is thought that the child also died, either at the same time or shortly after. Atticus was acquitted, and went on to erect monuments to her, including the Odeion. The question of whether he was motivated by genuine grief or a sense of guilt continues to be debated by modern scholars.

See:

Sarah B. Pomeroy, The Murder of Regilla: A case of domestic violence in antiquity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2007.

Maud W. Gleason, Making space for bicultural identity: Herodes Atticus commemorates Regilla, Version 1.0, July 2008. Princeton/ Stanford Working Papers in Classics, Stanford University. (PDF)

Helen McClees, A study of women in Attic inscriptions. Columbia University Press, New York, 1920. At the Internet Archive. |

|

Rigillis Street (Οδός Ρηγίλλης),

Athens, named after

Aspasia Annia Regilla.

Rigillis Street is the location

of Aristotle's Lyceum.

See Digging Aristotle

at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

|

| |

The "Tomb of Annia Regilla" in Caffarella Park, near the Via Appia, southeast of Rome city centre.

The tomb was built by Herodes Atticus for his deceased wife on his estate, known as the Pagus

Triopius (Triopius Farm), in the Valle della Caffarella, between the Via Appia and the Almone river,

outside the Aurelian Wall. Annia Regilla is thought to have been buried near Athens (although her

tomb has not yet been found), and this may have been a cenotaph (κενοτάφιον, kenotaphion,

symbolic empty grave) or shrine to her, unless her remains had been returned to Rome.

The area around the tomb is open to the public

on Saturdays and Sundays, 10 am - 4 pm (6 pm in summer).

For further information about the Triopion estate, see the articles

and photos on the Herodes Atticus page in the MFP People section.

|

4. Philostratus and the cedar roof of the Odeion

Modern scholars differ over whether the Odeion was roofed or open. The mention of a cedar roof by Philostratus (page 149) appears to have been confirmed by Kyriakos Pittakis' discovery of wood ash and ceramic roof tiles during excavations 1857-1858. One wonders if the ashes have been chemically analyzed to confirm they were of cedar. Several scholars, including John Travlos, have attempted reconstructions of the Odeion in order to assess whether such a suspended roof was structurally feasible without the support of columns.

"Herodes also dedicated to the Athenians the theatre in memory of Regilla, and he made its roof of cedar wood, though this wood is considered costly even for making statues."

Philostratus Lucius Flavius Philostratus (Φλάβιος Φιλόστρατος, circa 170-247 AD), nicknamed "the Athenian", was a Greek sophist, probably from the island of Lemnos, an overseas territory of Athens. Book II of his influential work Lives of the Sophists, written around 230-240 AD, contains a biography of Herodes Atticus, including several anecdotes about him.

Philostratus and Eunapius; The lives of the Sophists, Philostratus, Book II, chapter 1, section 551, page 149. In ancient Greek and English, translated by William Cave Wright. Heinemann, London and Putnam, New York, 1922. At the Internet Archive.

5. The audience capacity of the Odeion

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus was considered small by Roman standards, and compared with other theatres in the Graeco-Roman world. The estimates of seating capacities are sometimes quite staggering. When making such calculations, archaeologists generally allow a width of 50-60 centimetres per person - or per backside. High-ranking people took more space, and their chairs and thrones of honour in the front rows were over 60 cm wide. See the illustrations of seating for the elite in the Theatre of Dionysos on Acropolis gallery page 36.

6. Pausanias on the Odeion of Herodes Atticus

Pausanias first mentions the Odeion of Herodes Atticus when describing the Odeion at Patras:

"Next to the market-place is the Music Hall, where has been dedicated an Apollo well worth seeing. It was made from the spoils taken when alone of the Achaeans the people of Patrae helped the Aetolians against the army of the Gauls. The Music Hall is in every way the finest in Greece, except, of course, the one at Athens. This is unrivalled in size and magnificence, and was built by Herodes, an Athenian, in memory of his dead wife. The reason why I omitted to mention this Music Hall in my history of Attica is that my account of the Athenians was finished before Herodes began the building."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 20, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

This aside by Pausanias is an aid to scholars attempting to date his travels, his visit to Athens and the events he mentions.

Of the Panathenaic Stadium (see photo below), also built by Herodes Atticus, Pausanias writes:

"A marvel to the eyes, though not so impressive to hear of, is a race-course of white marble, the size of which can best be estimated from the fact that beginning in a crescent on the heights above the Ilissos, it descends in two straight lines to the river bank. This was built by Herodes, an Athenian, and the greater part of the Pentelic quarry was exhausted in its construction."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 19, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Further information about Pausanias in the MFP PEOPLE section. |

|

|

| |

The restored Panathenaic Stadium, originally built by Herodes Atticus

before 143 AD, south of the National Gardens in the centre of Athens.

|

For further information about the stadium, see the article

on the Herodes Atticus page in the MFP People section.

The Panathenaic Stadium, Pangrati, Athens

Tickets (from 1 January 2022): €10; reductions (students and visitors over 65 year old) €5.

Free Admission: children under 6 years; visitors with disabilities and person accompanying them.

Opening hours:

March - October 8:00 - 19:00;

November - February 8:00 - 17:00.

Website: www.panathenaicstadium.gr

The stadium, run by the Hellenic Olympic Committee, contains a museum of the building's history. Two of the four ancient herms found by archaeologists during excavations prior to the restoration of the stadium for the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 still stand at the near turn of the racetrack. Another is displayed in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens (see Pergamon gallery 2, page 15). |

|

|

|

7. Spon and Wheler

The French doctor and antiquarian Jacob Spon (1647-1685) and the English botanist (and later clergyman) George Wheler (1650–1723) visited Athens in 1676. See Acropolis gallery page 12 and page 35.

8. Stuart and Revett

James "Athenian" Stuart (1713–1788) and Nicholas Revett (1720–1804), English architects and artists, travelled through Italy, the Balkans and Greece 1749-1755. They stayed in Athens from 1751 to 1753, making the first accurate measurements and drawings of several ancient monuments, which appeared in their The Antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, the first volume of which was published in 1762.

See further information about Stuart and Revett on Acropolis gallery page 12 and page 35.

9. Early European visitors to Athens

Thomas Henry Dyer (1804-1888), writing in the early 1870s, outlines the confusion among early visitors to Athens in identifying the Odeion and the Theatre of Dionysos:

"From the time of Spon and Wheler down to that of Chandler, the Odeium of Regilla was thought to be the Dionysiac theatre. Even Stuart and Revett adopted this error. The opinions of earlier topographers were still more absurd. The Anonymous who visited it in 1460 called it the palace of Leonidas and Miltiades, and the school of Aristotle. Theodore Zygomalas, in a letter to Crusius in 1575 also calls it the school of Aristotle and Miltiades; Babin in 1665 took it for the Areiopagus. In the reign of Valerian it had been converted into a fortress."

Thomas Henry Dyer, Ancient Athens: its history, topography, and remains, Chapter X,

page 351. Bell and Daldy, London, 1873. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

10. Chandler and Leake study the topography

By the middle of the 18th century, historians (often referred to as antiquarians) and topographers travelling around the Mediterranean and Near East, could benefit from the works of earlier travellers and advances in historical and scientific knowledge. Dr Richard Chandler (1738-1810) and Colonel William Martin Leake (1777-1860) stand out as learned travellers and keen observers who did much to improve understanding of ancient civilizations.

"Richard Chandler was the first to recognize the true site [of the Theate of Dionysos]; and Leake, by calling attention to the now well-known coin of the Payne-Knight collection in the British Museum, removed all doubt on the subject.

This coin, although valueless in its details, at least proves conclusively that the theatre lay at the eastern end of the south side of the Acropolis, since otherwise the eastern front of the Parthenon could not have been represented on it.

Excavations were first made upon this spot by Athenian archaeologists shortly before 1860, but these led to no other result than the uncovering of the steps which are hewn in the rock near the former site of the choragic monument of Thrasyllus."

James A. Wheeler, The Theatre of Dionysus, in Papers of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume I, 1882-1883, Chapter 3, pages 121-179. Archaeological Institute of America. Cupples, Upham & Co., Boston, MA, 1885. At the Internet Archive.

For more about Chandler, see gallery page 8, 12, 35 and 36.

For more about Leake, see gallery page 12, 8, 33, 35 and 36. |

|

The Athenian bronze coin showing the Theatre of Dionysos. From the Payne-Knight collection,

British Museum, London.

See gallery page 36. |

|

11. Kyriakos Pittakis

Pittakis published his findings in Greek in Περί Θεάτρου Ηρώδου του Αττικού (On the Theatre of Herodes Atticus), Archaeological Society of Athens, 1858, pages 1707-1714.

Read more about Kyriakos Pittakis on Acropolis gallery page 12.

Thomas Henry Dyer recorded the following about the excavation of the Odeion by Pittakis:

"In the reign of Valerian it [the Odeion] had been converted into a fortress; and when excavated in 1857, under the superintendence of M. Pittakis, was found covered with rubbish to a great depth. This debris, among which was a mass of shells whose presence it is difficult to account for, showed, by the coins found in it, five different strata, from the Byzantine times down to the Turkish. It contained a great many other remains, such as vases, and other earthenware, sculptures, rings, etc.; also pieces of calcined cedar, which must have belonged to the roof.

A bomb still full of powder was also discovered, probably one of those discharged by Morosini and Königsmark. The scene must have extended upwards of seventy feet to the south of what is still seen, as indicated by several large stones, which must have belonged to the foundations of the facade."

Thomas Henry Dyer (1804-1888), Ancient Athens: its history, topography, and remains, Chapter X, page 351. Bell and Daldy, London, 1873. At the Internet Archive.

For a summary of archaeology in Athens in the mid 19th century, see:

John Travlos, Athens after the liberation: planning the new city and exploring the old. Hesperia, Volume 50, Issue 4, Greek Towns and Cities: A Symposium (Oct-Dec 1981), pages 393-407. American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org. |

|

Kyriakos Pittakis (1798-1863),

the first Greek archaeologist. |

|

|

12. Destruction by the Heruli

The Heruli have been blamed by historians for the destruction of many of the ancient monuments of Athens. However, it has also been argued that some this damage may have been caused by the attack of the Alaric's Goths in 396 AD. Accidental fires and natural catastrophes are also possibilities.

13. Versakis studies the Odeion

Friderikos Versakis (Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, 1880-1921), Μνημεία τών νοτίων προπόδων της Ακροπόλεως (Monuments on the south slope of the Acropolis). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1912, pages 161-182. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Versakis' article, in two parts, examines the southwest slope beneath the Acropolis, including the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, the Asklepeion and the Stoa of Eumenes (see next page).

Versakis also published an architectural study of the Choragic Monument of Nikias in 1913.

14. The Disdar Aga

The title Disdar Aga (also written Dizdar Aga, or Agha) was given to local military commanders in the Ottoman Empire. Such provincial officials earned various degrees of notoriety for injustice and corruption, and although not all were rogues, few of them were loved by their subjects, particularly in the Balkans.

The Disdar Aga of Athens lived in the "Palace of the Acciaiuoli", built by the Florentine Duke of Athens Nerio I Acciaioli (died 1394) in the Propylaia of the Acropolis, and his harem was housed in the Erechtheion.

Foreign visitors to Athens were expected to pay bakshish to the Disdar Aga as an 'entry fee' to the Acropolis. The English painter Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793-1865), who spent three and a half moths in Athens in 1818 (with trips to Aegina and Sounion), recorded in his journal:

"Admittance to the Acropolis was purchased by a present of three or four dollars to the Disdar Aga, a very civil old man. The Greeks never go there, so that we drew there in perfect tranquillity."

Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, Contributions to the literature of the fine arts, with a memoir by Lady Eastlake, chapter 3, page 85. John Murray, London, 1870. At the Internet Archive.

The Acropolis was occupied by the Turks until Spring 1833. But even after the Greek independence fighters had retaken the rock, it remained a military garrison, with a general quartered in the mosque in the Parthenon and a barracks in the Propylaia. The archaeologist Ludwig Ross finally managed to persuade the Greek government to demilitarize the Acropolis and oust the soldiers in 1834 (see Acropolis gallery page 12, note 6).

15. "Sir G. Wheler imagines ..."

Sir G. Wheler was George Wheler, who visited Athens with Jacob Spon in 1676 (see note 7).

It seems odd that Stuart here admits the probability of Wheler's theory that the archway behind the Odeion was the cave "where a tripod was placed, on which was wrought the story of Apollo and Diana [Artemis], slaying the sons and daughters of Niobe".

Wheler, incorrectly identifying the Odeion as the Theatre of Dionysos, imagined that this must be the cave above the theatre mentioned by Pausanias:

"At the top of the theater is a cave in the rocks under the Acropolis. This also has a tripod over it, wherein are Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book I, Chapter 21, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

However, Spon, Wheler, Stuart and Revett had already found and drawn this cave, the site of the Monument of Thrasyllos, which was converted in Byzantine times to the chapel of Panagia Spiliotissa (see Acropolis gallery page 35).

The arched recess in which Revett sat, and which he and Stuart took for a cave, no longer exists; it was presumably destroyed during one of the subsequent sieges and bombardments of the Acropolis. Recent reconstruction drawings, by researchers such as John Travlos **, show two storeys of arches curved around the top of the back wall of the cavea. These arches, the bases of which can still be seen, may have fronted covered galleries or walkways behind the Odeion and have supported the roof. Such an archway, covered by soil and rubble, may have appeared to Stuart and Revett as a cave.

** See:

John Travlos (Ιωάννης Τραυλός, 1908-1985), Pictorial dictionary of ancient Athens.

Thames and Hudson, London, 1971.

In German: Bildlexikon zur Topographie des antiken Attika. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

Ernst J. Wasmuth Verlag, Tübingen, 1988.

Read more about Niobe and see a photo of the "Weeping Rock of Niobe" in Manisa (Magnesia ad Sypilum) on Acropolis gallery page 35.

16. Dodwell on the Turkish cemetery west of the Acropolis

Edward Dodwell (1767-1832), Irish painter, travel writer and antiquarian, A classical and topographical tour through Greece, during the Years 1801, 1805, and 1806, Volume Ι, chapter X, page 305. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819. |

|

|

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|