|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Edwin Drood's Column > January 2012 |

|

|

back |

Edwin Drood's Column |

|

24 January 2012 |

|

| |

|

|

In which Edwin asks when we began to think in terms of modernity or the lack of it, what purpose is served thereby and just what is required for a thing, idea or phenomenon to be perceived as modern.

|

I’ve often wondered when we first began to see artefacts and even individuals as being either outdated or modern. Did the ancient Greeks think of themselves as modern? Did the Romans consider themselves cutting-edge? Did the Carthaginians, the Babylonians and the Assyrians? And what of the Medes and the Hittites, were they knowingly up to date in their product choices or was it mere chance that gave one man a better spear-thrower, another a more efficient plough? I rather suspect that we only gained the concept of modernity as a value when we began to view the future as something rather more than just today being repeated indefinitely. |

| The invention of modernity |

|

The term modern has been around since the Latin from which it derives, but only in the restricted sense of “that which is currently happening”, which might be a secret coven of subversives working on radical reform or a stuffy gathering of old pedants intent on preserving privilege and opposed to any kind of change. Insofar as both these events could occur simultaneously, modern (in its ancient sense) could apply equally to either of them. It would seem that, at least in English, the word was first used in its “modern” sense of contrasting with the established method, idea or thing, towards the end of the 16th Century.

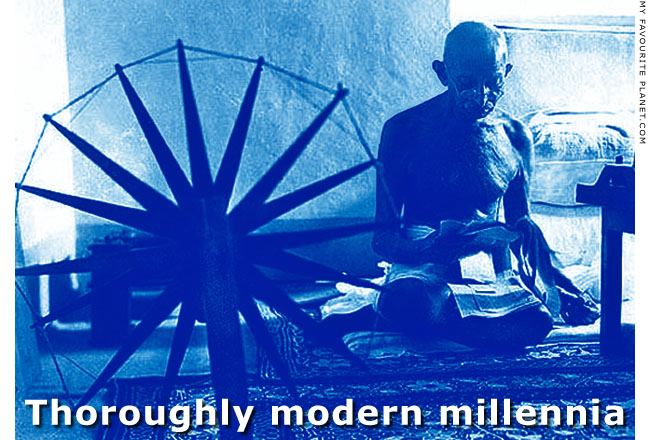

In historical terminology, “modern” designates an epoch that begins after the dark ages and ends right now. The modern epoch traces the urbanisation and secularisation of society as well as the demographic changes that altered traditional structures of power. Although earlier periods had seen the introduction of techniques and materials that were startlingly new and changed the way people worked (bronze, iron, glazed pottery, glass, woodblock printing etc), it wasn’t until the late mediaeval chartering of towns, the first agrarian revolution and the setting up of guilds and corporations that the conscious application and championing of newness became a predominant driver of social change. While we would find most of the sixteenth century shockingly primitive, yet we can resonate to Shakespeare as an essentially modern playwright, because that’s exactly what he was. He offered works that were repeatable, relevant and defining: all of which are generally accepted aspects of a modern thing, idea or phenomenon to this day. |

| The rise of the modern man |

|

The frame of repeatability, relevance and definition can be used to class anything as either outdated or modern. Take the steam locomotive, the newspaper or the postal service: all of these were wonderfully repeatable (and we can still produce them), yet their lack of relevance to our age is as clear as the way they defined a certain way of being for the people of the 19th and early 20th centuries. To be modern then was to be informed of a thing in the newspaper first thing in the morning and to take a train up to London to witness it yourself or simply write a letter to The Times about it that would arrive on the editor’s desk the very same day. The personal computer, in all its forms, now offers all these services even faster (newspapers, postal services and railways have, for the most part, miserably failed to maintain their standard), and if we really have to “be there”, we can still take a modern train or travel in our infinitely relevant, repeatable and defining personal transporter, the car ... or such is the dream at least.

A thing, service, phenomenon or idea must score sufficiently high on repeatability, relevance and the way it defines – by its very existence – a trend, class, group, movement or simply a precise moment in time in order to exist at all in the modern world. The invention of modernity as a concept has thus gone hand in hand with the gradual emergence of modern man as an independent creature with a personal style in a personalized space and a personal world view. Notwithstanding, all the diverse elements making up the former have been filtered through the creative, commercial and social processes of vast networks of resourceful people who have tested them for their robustness, validity and market value ... otherwise they would simply never have emerged as styles, preferences, objects, philosophies or opinions. |

|

Here today |

|

|

A feature of this current period, which we still refer to in cultural terms as “post-modern” (a ridiculous notion to pure historians, but understandable once you have decided for all time that Picasso and Pollock were modern artists, Stockhausen and Schonberg were modern composers and the Bauhaus school defined modernity in architecture) is that we can no longer separate ideas from the technologies that vector them.

|

The internet is thus as much an ideal as it is an electronic data exchange network. The movement of dramatic arts, fine arts and publication from the real to the virtual is a similar phenomenon, impossible to separate from the ever more refined technologies that act as carriers.

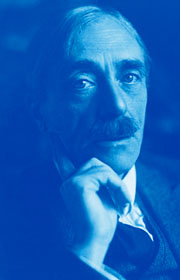

Writing on the subject of art and the technology of its creation, Paul Valéry already offered the following observation in the 1930s: |

| |

“In all the arts there is a physical component which can no longer be considered or treated as it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. For the last twenty years neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial. We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing transformation in our very notion of art ... the astonishing growth of our techniques, the adaptability and precision they have attained, the ideas and habits they are creating, make it a certainty that profound changes are impending in the ancient craft of the Beautiful.”

|

|

I don’t think he was talking about PowerPoint presentations, 3D cinema, Flickr or YouTube. So, even if they occasionally rise to the challenge, I believe much of his prophecy remains as yet unfulfilled. |

|

Paul Valéry (1871-1945)

French poet, essayist

and philosopher

photo: Pierre Choumoff |

|

| Gone tomorrow |

A further attribute of modernity, and a less desirable one, is evanescence. The great idea that defines its time can hardly be expected to define another age as well, unless the cyclical mill of history manages to present it in a new and refreshingly digestible guise to some future generation. Capitalism and socialism are both ideas that patiently suffer reinvention every few decades. Temperance is enjoying a new lease of life, as are virginity and vegetarianism. But we will probably wait in vain for slavery or feudalism, paternalism or orthodoxy to once more be perceived as modern.

Objects are even less fortunate. Aside from the slim chance of returning as nostalgia to take on a new lease of life and redefine a new generation of stylishly modern aficionados, like vinyl records or the Fiat 500, the life of an object as something acceptably modern is generally very short indeed, unless, like the Eames chair, the buildings of Mies van der Rohe, the Fender Stratocaster, the Cuban cigar, the image of Uncle Sam or the Coca-Cola bottle, you are lucky enough to be perceived as iconic: a status that confers incredible longevity, possibly even eternity. Steve Jobs may be the first person ever to have combined the attributes of cool, visionary, utilitarian and iconic in a single person and extend it to a whole line of repeatable and relevant products and services that have defined their own class and shaped an entire culture. |

| The once and future thing |

Will Jobs still be a giant in 2050? Will Marilyn Monroe still be modern in 2099? Will Jimi Hendrix and Bob Marley still hang on walls? Will James Dean, Kurt Cobain and Ché Guevara still represent rebellion in the 22nd century? How long will the ubiquitous smart-phone in its latest and coolest iteration be considered a cult object rather than just something you have? Paul Valéry, once again, already envisaged if not precisely ipad 2, then certainly something very like it:

| |

“Just as water, gas, and electricity are brought into our houses from far off to satisfy our needs in response to minimal effort, so we shall be supplied with visual or auditory images, which will appear and disappear at a simple movement of the hand, hardly more than a sign.”

|

For someone writing in 1931, Valéry was far, far ahead of his time. Did that make him modern? No, it made him a priest, an oracle. Prescience is the art of correctly imagining the future, modernity is the art of making it happen now for everyone. Take Buckminster Fuller as an example. He was modern in the 1970s and 80s. In his own decade he was a strange and marginal visionary who has since managed to scrape over the threshold of “footnote” to take his rightful place in the pantheon. The present isn’t what it used to be either.

© Edwin Drood, January 2012 |

|

| |

Responses to this blog

|

|

|

Dear Edwin,

Thanks for the clarifications re modernity. I shall immediately apply them to the baguettes here in France which now are of two types: the new "traditional" ones and the traditional "new" ones.

Roger Greatorex, Paris, France, via the My Favourite Planet Group page on Facebook.

Edwin replies:

Roger's comment exactly catches the dilemma of modernity. Your retro beetle is new, but it's not modern. Yet its attitude, marketing and tech is modern, so is it still retro? I've already noticed the baguette issue ... but forgotten it. Nice to have it mentioned. Edwin |

|

|

Edwin Drood's Column, the blog by The Mysterious Edwin Drood,

at My Favourite Planet Blogs.

We welcome all considerate responses to this article

and all other blogs on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|