|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Edwin Drood's Column > December 2014 |

|

|

back |

Edwin Drood's Column |

|

2 December 2014 |

|

| |

|

|

This is a second week in which, at the risk of being taken for one of those magazine programmes

that carry general interest stories instead of hard news, Edwin presents a little potpourri of themes

and ideas to delight your neurones instead of grappling with one big thing.

|

| “My brother Esau” |

Somebody once said (it might have been me) that the biggest problem with life is the lack of a handbook. What about the Bible, you might ask, or the Quran? Fine, as far as they go with loving your neighbour, smiting the infidel and such general topics. Not much good when it comes to the specifics of dealing with a hysterical 2-year-old in a supermarket checkout queue. Love is doubtless the desirable course, but smiting looks like a highly attractive option.

And even on big issues, you will often find ourself in conflict with the very neighbour you are trying to love, simply because his handbook doesn’t say the same thing as yours. He may be celebrating loudly when you are trying to get some sleep, or fasting just when you want to invite him over for a barbecue.

Sacred texts are also not much good on key practical questions, either, or not without a deal of research. Sure they’ll tell you either to drink or not drink alcohol (roughly this breaks down as Christians, Jews and Hindus = yes, Muslims, Baha’is and Sikhs = no) but whether you should go for red or white wine with the wild sea bass (wild? It was livid!) or mint tea with your spiced lamb or malt beer with the nut-burger? Silence on all of those … The abstruse nature of chapter and verse demands your full attention if it’s useful advice you’re looking for in a fix. Ambiguous tenets are surely the last thing you need when trying to survive your first earthquake, baby, riot, death, etc.

Holy books are also abominably badly structured. The index, if there is one, is generally no more than a list of chapters, which might be organized by length, chronology, or the purely arbitrary decisions of some anonymous 11th Century synod. You can’t simply look something up, like in a VW servicing manual. So it’s small wonder that so many people choose the “open-at-random-and-dab-with-finger” method when seeking divine guidance. As a modus operandi it’s as good as any. But if you’re caught in the middle of a flash flood in the Ghobi desert, don’t be too upset when your finger alights on the doubtless highly relevant verse: “For my brother Esau is a hairy man, but I am a smooth man”. And if that doesn’t help you, there’s no complaints department. |

| “Perchance to dream” |

I went shopping for a new mattress recently. Never again! This was the most exhausting day of my life. I must have almost, but not quite, fallen asleep a hundred times while dutifully testing different foams, forms and fillings, and had to emerge each time from that awful grogginess so familiar to surgeons, long distance lorry drivers and others whose profession routinely deprives them of rest. So now I know that the most tiring job in the world, if it exists as such, is that of mattress tester.

Before making my final and rather conventional choice, I was tempted by some quite extraordinary examples of modern sleep-tech, such as dynamically rated springing that adapts to your breathing rhythm, self-ventilating, anti-allergenic cores and body-moulding, variable-stress foam that remembers your favourite position … really? Yes, there are mattresses with memories. Now whether the mattress comes with its memories fully installed or gathers and organizes them gradually as it matures, I’m not entirely sure. But I find the idea a bit disturbing. Do I want my mattress recalling stuff? Exactly what kind of favourite positions does it remember? It might write a kiss-and-tell memoire like Valerie Trierweiler and then where would I be? Or does it prefer to remember my dreams? That might be useful; it could subtly cue me in to a particularly pleasing one. But its natural buoyancy, its flippant and flexible foam consciousness might capitulate under the numbing banality of most of them. |

| “They’re there” |

“There, there, there”, as our housekeeper used to say when I fell over and hurt myself, but I could never quite work out to what she was referring. Was something over “there”, and if so, where? Were “they” coming to kiss it better? “There, they’re there”? Or was my pain perhaps “their” problem? I grew up and understanding dawned: when you’re here and they’re there, then your “here” is their “there”. Got it?

Sixty years later, thanks to the glorious leveller of the internet, and in particular the grammatically unhealthy zone that is the comments section of almost any YouTube video, I’ve grown used to seeing people “loose” the things they’d like to “lose”, replace “your” with “you’re”, “too” with “to” and vice versa, as well as use all permutations of “there”, “their” and “they’re” in the wrong places. As a result I’m now numb to the finer points of grammar.

But ignorance must indeed be bliss, for while these partial illiterates seem immune to syntax or spelling, yet they are, by their own account, usually experts in whatever field they are commenting, or have a brother/cousin/neighbour who is, and delight in exposing the depth of that knowledge for the general delight of all, announcing the stature of their intellect and tenor of their character with every phrase. That most of these titans of prose come from a very large nation with a highly developed and expensive education system and an equally highly developed sense of its importance, a nation where English is the official tongue, is a sad testimony to the steady decline in our times of the language of Congreve and Shakespeare … or maybe not, because the latter also had his orthographic issues. And as Robert Savage famously quipped: “A chrysanthemum by any other name would be a lot easier to spell!” |

| “Death is a cold lasagne” |

From syntax and other taxes, I segue seamlessly into death, American style. Apparently a company in the USA can now compact your funeral ashes into a series of ceramic bullets for your dear descendants to blast away at the targets of their choice. The possibilities for poetic irony and justice are endless. You could end up posthumously killing your own bullying parents, or your as yet unborn grandchild, your daughter’s future cheating husband or her mother in law in a complex domestic firearms accident. ‘Ahmad, the Dead Terrorist’ could be reduced to a thousand ball bearings, untraceable by metal detector, through the agency of which he could be gloriously martyred a second time.

Oh my goodness, what a world of cinematographic opportunity for horror and black humour presents itself? The reality, I fear, will be more banal. People will take a clip of ammo distilled from the remains of their favourite dog to go hunting with, or hammer away for twenty sublime seconds with the residue of a hated domestic tyrant at his or her entire lifetime collection of sports memorabilia or beer bottles. I should like to make it clear that if anyone decides to reduce me to ammunition, I would prefer not to be used for the purpose of political assassination, however tempting it might seem. |

|

| “Of a foreign field” |

Just got back from visiting World War I sites in Flanders: not especially foreign fields, since I live here. But it has taken me thirty years and needed a significant centenary before I finally did the right thing by all our poor young lads and their German counterparts. This was the war that gave us the expression “cannon fodder” and richly is it deserved. The most profound effect of my visit was the realization that I feel closer to, and have more in common with, most of the men lying here than with most of my contemporaries, but perhaps that’s my own mortality whispering to me.

Yet these massive casualties have engendered other ties that are far from casual, as can be seen from the large number of modern testimonies left on British, Commonwealth or German graves right across the Westhoek region. Meanwhile, an entire economy has grown up on the basis of those four years of trench warfare. Towns once reduced to rubble are now restored to glory. The hotels and restaurants are full and a new generation of school children is today more familiar with WWI than with the Weimar Republic or the rise of fascism, better acquainted with Paschendael than with Bastogne. That is a good thing.

Nothing can really prepare you for the reality of those Flemish charnel houses! The scale of death and destruction of individuality and human potential in the service of the armaments industry is utterly staggering. Wandering solemnly through the beautifully laid out, impeccably well-tended cemeteries you realize that the majority of graves are either of unknown warriors or of soldiers whose regiment is known, but little else. There are 86,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers still unaccounted for from the battles of the Ypres Salient. It is unlikely now that they will ever be found or, if found, identified. Most of these were probably pulverized into fertilizer. Yet WWI was not the hecatomb we generally think it was. It was, for example, nowhere near as deadly as the Spanish flu epidemic that followed it.

Given the unbelievable levels of overkill (a typical trench mortar might leave a 10-metre crater, large calibre shells and mines would lift as much as 500 cubic metres of Flanders into the air to fall back down over an area the size of a football field) it may seem a miracle that anyone who served in the trenches survived to tell the tale. But they did, many, many thousands of them. In fact, you were seven and a half times more likely to survive the First World War than you were to die in it. Of course, survival came at a price, psychological, moral and physical. But all in all, thanks to the very short periods spent directly in the firing line, the ever-improving designs of trenches, dugouts and fortifications, life for those serving in this conflict was actually better than in previous wars. Common soldiers were better housed, better trained, better equipped and far better fed than their forbears or, indeed, than many of those they left at home.

Perhaps the war appears so especially horrific to us today on account of the almost non-existent grounds it was waged upon. If it was not history’s deadliest war, it was certainly its most unnecessary and futile. But titles such as “the Great War”, or the “war to end all wars”, are unjust to those who died and to those who survived to give their sons and daughters up to the next great conflict, born out of Adolf Hitler’s clever manipulation of the Versailles Treaty to his own political advantage. The truth is that Germany got away quite well under the Versailles terms; they lost little territory and were subjected to a regime of reparations in direct proportion to their economy. Things could have been a whole lot worse. They were a whole lot worse after WWII, when Germany was occupied, partitioned, sold off to the highest bidders … and yet they survived that period with a handful of aces and are now the most European of European nations.

However, despite the relative generosity of the Versailles Treaty, the Nazis managed to turn the grim depression years that affected the entire western monetary system in the late twenties into a uniquely German tragedy caused by the depredations of foreign governments and their enslavement to international Jewry. This, of course, was economic, historical and social nonsense, but it made good political copy and hungry Germans lapped it up.

If the WWI allied powers had taken their responsibilities more seriously and continued to strictly levy reparations on through the thirties while firmly prohibiting every attempt at German remilitarization, WWII might never have happened. Yes, that’s what Churchill said all along and, however unpopular he was at the time, history would prove him right and goes on proving him right today. Had we heeded that hawkish message, we could ALL, Germans included, have transitioned peacefully into three golden economic decades of the forties, fifties and sixties and so on and so forth. What a wonderful world this would be? No Cold War, no Korean or Vietnam wars, no Yugoslav conflict, no Islamic terrorism … but not much to write about for your favourite blogger. All quiet on the Western Front.

© Edwin Drood, December 2014

Illustrations

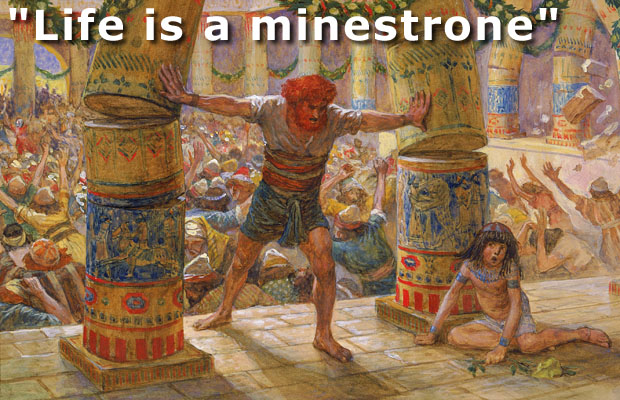

Top: Samson Puts Down the Pillars, gouache on board circa 1896-1902, by James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902). The Jewish Museum, New York.

Above: Zonnebeke (Ypres Salient, Belgium), 1918. Painting by William Orpen (1878-1931). Oil on canvas. Tate Gallery, London. |

| |

British soldiers of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division blinded by gas during the Battle of the Lys,

also known as the Fourth Battle of Ypres, 10 April 1918. The German Spring Offensive began

on 7 April 1918, and after a battle lasting three weeks and costing 120,000 lives on both sides,

was finally abandoned.

Photo: Thomas Keith Aitken, a press photographer serving as second lieutenant. |

| |

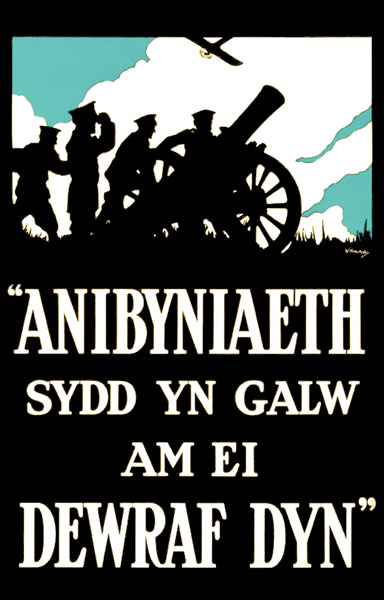

First World War recruitment poster in Welsh.

"Anibyniaeth sydd yn galw am ei dewraf dyn" (Independence which calls for its bravest man).

Ironically, a line from the military song Men of Harlech or The March of the Men of Harlech

(Rhyfelgyrch Gwŷr Harlech) which is about fighting the English.

Published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, London. Poster No. 148. |

|

Edwin Drood's Column, the blog by The Mysterious Edwin Drood,

at My Favourite Planet Blogs.

We welcome all considerate responses to this article

and all other blogs on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo, Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|