|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > Blogs > Edwin Drood's Column > April 2020 |

|

back |

Edwin Drood's Column |

|

21 April 2020 |

|

|

| |

|

| The Lender of Last Resort |

| |

In which Edwin tells a timely tale from two other times, thus helping to pass

time across three generations and while away the time for yet another. |

| |

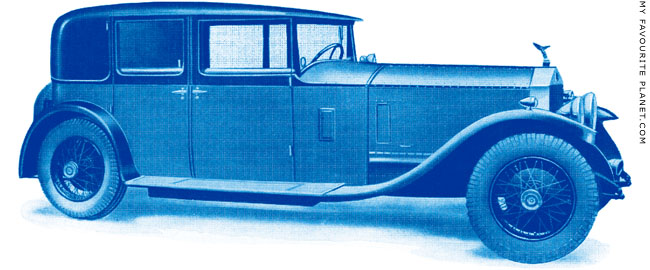

Quentin Drood, grandson of the notorious Sir Tristan, brother of the enigmatic Haviland (known at the Foreign Office as ‘Drood the Obscure’), stood on the sturdy running board that Gurney Nutting had so thoughtfully provided to his brother’s 1933 Rolls Royce Phantom II Continental and surveyed the valley. The car was at last seeing some serious mileage. Since its latest change of ownership, it had been mothballed for three years while its owner was on government business in the Far East. After much cajoling and pleading, Quentin had finally gained both permission and keys: high time for a European Tour!

Seen from the crest road, the view for miles across this rugged country was inspiring. But that which held my father’s attention was happening right in the foreground, where a funeral procession was moving slowly along a village street. What attracted his notice were not only the bright colours but also that the pallbearers appeared to be children, no mere effect of distance, but real children, for the coffin was clearly full-sized! When he remarked upon this, his guide, a man from the region, said that it was a very ancient tradition in these parts. No matter who was being buried, the pallbearers were always the children of the village. It might have surprised the guide to learn that the tradition dated back only to the beginning of the last century ... not so very ancient after all. |

|

Once upon a time there lived an old man. He had always been old. Perhaps he was born that way. Certainly, he had an old heart, as old and tired as a dried up pump, and old lungs like a pair of worn out bellows. They made a wheezy, whistling noise as he breathed. There was a leak there somewhere. His life was leaking away with each breath and yet he lived on, outlasting many younger and fitter men and many a young girl in the flower of youth.

For these were dark times. It had been many years now that the sickness lay upon those valleys. It struck without regard for age or rank, for humour or constitution, honour or virtue. It killed the saint and the ruffian. It took the master and the servant, the high and the humble. It broke open whole families like rotted wine casks and wasted their lifeblood upon the cellar floor. Prosperity was long gone from those hills. The rich clung on from the sheer habit of privilege and the poor from the mere habit of submission. Everyone wished and prayed for better times. No one really believed their prayers.

The people sold what they had to survive. They would travel far with a cartload and come home with a pittance. The walled towns would not let them in, for it was known that the sickness, which had ravaged the cities, was still at work in the countryside. So they would leave their meagre property at the gate for the sheriff’s agents to make an arbitrary valuation. Hours later they would find an empty cart and a piece of paper nailed to it. They would take the paper to a small dark window near the city gate where they could cash it in for coin or even for cheese, bread and olives from healthier regions beyond the mountains, if they were lucky and if they were first in line. |

|

The old man was rich: very, very rich. Just as he had been born old, he had also been born wealthy. He came from a long line of lenders, from father to son, from mother to daughter. They had all learned the hard rules of a hard house: never to be generous, never to be lenient and above all, never to be trusting. So, like his forefathers, he always insisted on collateral for every loan, however small: collateral and a contract.

A house was collateral, but houses were crumbling into terminal disrepair. Land was collateral, but the land was going back to the harsh wilderness it had been carved out of. Wine was collateral, but the wine was bitter and brackish and would not keep. Rings and trinkets, cutlery and cruets, medals and keepsakes ... all were grist to his mill. And so the loans kept on coming, even for the most desperate, if the collateral was right. For if all else failed, they said, the old man could be relied on. They called him what he called himself: ‘the lender of last resort’.

Very few could pay the interest on their loans, so instead it ate up the collateral. Thus, piece-by-piece, gem-by-gem, brick-by-brick, acre-by-acre the villages of those valleys passed into the hands of the lender of last resort, who day-by-day grew older and richer. But his wealth was meaningless where nothing could be bought for it. And the quality of collateral was changing from things of substance and value to mere bric-a-brac. You cannot draw blood from a stone. Yet soon only stones would be left to draw blood from ... which was where the contract came in.

The contract always carried the same obligation. The remaining value of the loan and any interest not absorbed by the collateral could be called upon at any time in hours of labour from the contractual party, or their heirs unto the next generation, if the party was no longer able or available to render such labour themselves.

It was the lender of last resort who would deem whether a borrower was fit to pay him off in labour ... or not. In the latter case, and recently most cases were of this kind, the old man would demand the service not of his debtors, but of their children. Children were young, easily driven and relatively strong. Even the very young or the weak could work at tasks fit for small hands, such as sewing and mending, cleaning and polishing, or keeping the books in good order in the old man’s library while their elder brothers and sisters tilled the land, seeded and harvested the fields, trimmed and cared for the old man’s spacious park, fetched and carried wood and water, food and wine. |

|

In one of the walled towns further down the valley lived a notary. To this notary came one day a request to hurry urgently to the city gate. There he was surprised to find a small messenger waiting. “Please sir”, said the little girl, “I’m to give you this letter, sir and await a reply.” The letter, which came from the lender of last resort, was a formal request that the notary might please be so good as to immediately draw up a will in two copies with two straightforward testamentary clauses. This will was then to be carried by the small messenger to a tavern outside the city wall where it would be signed in two copies by the lender – who would arrive by coach at midday, wrapped in a thick cloak to preserve his anonymity – and then witnessed by two randomly chosen citizens under terms of the strictest confidence. Thereafter, the small messenger would return one copy to the notary, while the other would travel back to the village by coach with the old man. How the small messenger would get home after her second walk into town was not considered of any consequence.

But neither the long walk, nor the heat, nor the thirst could sadden the small messenger. On the contrary, her heart was singing with every step because the old man had promised her a gold quarter sovereign for the completion of her mission but, above all, for her silence. The lender, whose jaundiced eyes saw everything, had noticed the care with which this child handled his valuable books when working about the house and, rather than pick just any fleet-footed lad for this important task, had chosen her as being the one most likely to carry out his orders with diligence.

As far as the little girl knew, the lender had never paid any of his charges for the errands they ran, or indeed for any kind of labour, it all being understood as payment for their parent’s debt. This then was something most unusual and the small messenger felt privileged to have been singled out for such an honour and, above all, for such a reward, to which she was greatly looking forward. For her it represented a small fortune, perhaps the start of a better life altogether. But little could she know, as she strode cheerfully back up the valley, how her childish dreams now hung in the balance. |

|

Just a half-mile from home, while negotiating a steep escarpment, one of the carriage horses threw a shoe, which then hung awkwardly by one nail. The loose shoe caused the animal to stumble and slip sideways down a gravel embankment. The carriage teetered for a moment at the edge of a dried up streambed before capsizing with much creaking and crashing amid the shouted imprecations of its elderly passenger.

When the coachman had recovered sufficiently from the fall to inspect the wreckage, he found the coach to be in passable condition and both horses quite unscathed, but that his master had not fared so well. It wasn’t the dry heart, nor yet the leaky lungs that took him. In the tumble, which threw him hard against the doorframe, his neck met the window ledge at an unfortunate angle. The lender of last resort would no longer be extending credit, his personal line of liquidity having been most abruptly and definitively withdrawn. |

|

When the villagers were told of the accident, their sympathy did not extend far beyond the bruises of the coachman and the fright of the horses. For the old man, no one had any particular feelings other than a permanent sense of dread from being beholden to someone malignant and powerful, of standing forever in his debt, yet without either gratitude or hope of redemption.

Each was considering in his heart how things might develop. Were they all now freed from their obligations? Or would some relative, some bank or distant official arrive to make their lives even worse by recovering the old man’s debts on pain of imprisonment or the workhouse? Whole families had died in the workhouses back when the sickness first came. Everyone knew the grim stories of wardens running away in the night for fear, leaving their sick and helpless charges to starve behind locked doors.

Yet despite this uncertainty they still dared to believe that their troubles might be over, even if nobody else were there to advance them money in the hardest of times, albeit at the price of their property, their freedom or their children’s future. For though the lender of last resort was an ogre, he was an ogre they had grown to rely on. Like most primitive people in the service of a harsh god, they had become so used to paying tribute with their lives and honour that they could neither remember how life was before nor easily imagine how it could be different in the future. |

|

As the small messenger dragged her exhausted feet along the village’s one paved road that evening, she was immediately aware of a strange atmosphere: on the one hand there was the usual silence of that sad place, home to so much misfortune and so little joy that one seldom heard much above murmured conversation at the best of times, on the other hand there hung in the air a strange sense of relief or expectancy, as if something momentous had taken place and everyone was waiting to see what it meant for them. It was as if the whole valley was holding its breath.

However, no sooner had the child been apprised of the news by her parents that the region’s most fearsome inhabitant was dead, the man to whom every family and every farm stood in debt, for whom no one had ever had a kind word or thought as far back as could be remembered ... no sooner had they told her about the upturned carriage and the broken neck, than she burst into tears and then fainted clean away onto the hard earth floor. And the moment she had revived and had her little body sufficiently under control to stand up again, she rushed out of the door and up through the village to where the old man’s house stood apart from all others in its high-walled garden. Once inside she dashed past the few startled retainers and flung herself across the old man’s corpse where it lay, much as it had arrived, with its head on one side and a large envelope tucked into the breast pocket of the velvet doublet under the voluminous dark cloak. And there the small messenger remained, weak with tears and inconsolable until the room grew quite dark and the body was quite cold. |

|

The next day saw the arrival of a masked priest and a clerk of the county court who periodically sprayed himself and everything around him with a mixture of oil of cloves and rosewater. The clerk was there to evaluate the dead man’s estate and secure any will or other document of intention that he might have left behind. The priest was there to see to the progress of the lender’s immortal soul, for which sad spectre, due to his manifest disbelief in anything other than hard cash, little hope was proffered.

The village had no undertaker. Usually it was the family of the departed who prepared their loved one for burial. But at the height of the sickness, when every day had seen its share of death, such things were impossible. Since then the duty had fallen upon a rough couple whose lives had been lived more outside the law than in and who thus owed a debt to the community for being allowed to exist at all among good honest working folk. These two would wash and lay out even diseased bodies for a price. The price was agreed with the parish and this became their livelihood. While the man sawed wood for the most makeshift of caskets and dug the grave, his wife would be occupied with preparing the body and generally making sure that anything found in its pockets might later be found in hers.

This delightful couple now occupied the old man’s home under the righteous and vigilant eye of the county clerk. They were also under the equally vigilant eye of the small messenger who, throughout the comings and goings of the days following the old man’s death, only left the house to sleep ... until, that is, the day of the burial. For on that day, she gathered all the children of the village together on the plot of land halfway up the mountainside, which had been given over to burials since the sickness made inhumation in the chapel graveyard impossible.

An hour later a solemn group of children could be seen with picks and spades digging away diligently in the hard earth. Meanwhile, another equally solemn group were making their way – in the cleanest clothes they had and with small sprays of wild flowers in their hands – to the home of the lender of last resort. The undertaker couple were completely nonplussed by their arrival and even more surprised to hear that they need not trouble themselves with digging a grave as that had already been taken care of. |

|

Neither the old man nor the casket weighed very much, but it still took three teams of six of the village’s sturdiest children to carry it down the central street and then up the long diagonal slope that led to the cemetery. Once there, the priest, who was as surprised as everybody else by these developments, led a brief ceremony, after which the county clerk let it be known that the old man’s will would be opened that afternoon at his house and that the notary from the town had been sent for, so that the copies could be compared to ensure no funny business, at which point he let his glance sweep balefully across the entire assembly, lingering rather long on the unfortunate priest and the undertaker’s wife.

As the villagers drifted away in groups the youngsters stayed behind in silence for a while before laying their posies on the grave they had dug and filled themselves. The priest watched them from the gate, wondering at such signs of earnest religiosity and grief from the children of such hardy, practical people. Everybody knew that these kids had worked their fingers to the bone to pay off their parents’ debt. How could they mourn a man who had treated them with such harsh indifference?

It was mysterious indeed, particularly to this acolyte, who was not cut from an especially spiritual pattern, but rather from that clerical template formed by the pragmatic need to choose a profession that offered security and respect in equal measure. For his part, he honestly found it hard to believe in miracles in this scientific age, and was most uncomfortable with the emotions he was now feeling. His faith had taught him that the wages of a sinful life were death, not merely of the body but of the soul. Yet here he could see that the wages of death might be the ruddy faces of children, satisfied with a good job done at the end of a hard day.

Could this also be a miracle, as miraculous as the saving of publicans and tax collectors, the conversion of Saul on the road to Damascus, or the raising of Lazarus? Should he write a letter to his bishop? What lesson had these children learned, that they could now teach their elders the true nature of love, which even when openly scorned can be freely given: unasked, unconditional and unearned to even the most undeserving? It was, to say the least, puzzling. |

|

The reading of the will was a momentous affair, not only because everyone in the village had a keen interest in its content, but also because not one, not two, but three pretenders to the lender’s fortune had arrived within the last hour. Yes, they were genuine kin, of a distant variety, but family all the same, but no, they could hardly pretend to be in mourning, since none of them had ever met the man. The notary was quick to point out that contesting the will would be pointless. It was ironclad. He had drawn it up himself. For obvious reasons there could be no later version, and if earlier versions existed, they were herewith invalid. After such an introduction, the testament itself could hardly fail to disappoint ... yet it did not.

The provisions were clear and simple: the ‘immoveable estate’ in land, dwellings, outbuildings, streams, wells and springs, together with all rights of access and utility pertaining to them would form a financial foundation “for the construction of a medical hospice to defeat the scourge of sickness that has crippled the economic life of this region.” If this were not already enough of a surprise, the next clause would awaken even greater wonder. Excepted from the medical foundation were such lands and buildings held in collateral against loans “granted to any persons who voluntarily – free of remuneration, conscription or coercion – step forth to accomplish their civic duty” by the deceased in the performance of his funeral rites. Such actions would fully redeem the debt and reclaim the collateral of anyone who undertook them.

There was a long moment of stunned silence while these words took what was, for many of those present, a seldom-travelled route from ear to brain. Then all eyes swung to the children grouped together near the door. For their part, the children stared solemnly at the ground and tried very hard to be invisible.

But the notary was not done. There was more. “The ‘moveable estate’,” he read, “comprising notes and coin to the sum of (and here a truly paint-stripping amount was mentioned as being present at the time of writing) also diverse medals, jewellery, keepsakes & trinkets, together with the furnishings and contents of my house, I bequeath in full to be shared equally among those of my kinfolk, my neighbours, my employees and acquaintance who show heartfelt grief at my passing, in the absence of which, such moneys and properties shall be used to endow in perpetuity the aforementioned hospice with the skills of a trained research physician.”

Those same eyes which had swept the group of children from top to bottom and from end to end, as they stood and stared at the dried mud on their boots with quite unnatural concern, now fixed like gimlets upon the waif-like figure of the small messenger, whose interest was currently held by a barely visible repair on the front of her best smock, but whose abject grief at the old man’s demise had been the talk of the village for the last three days. Clearly, an explanation was called for. |

|

It was the priest who spoke first. “Rather than permit the possible perpetration of a fraud, might it not be in the best interest of all if I were to have a brief word in the next room with the young person?” But whatever the intent of this negotiation, it was not to be, for the “young person” herself spoke up, clear and calm.

“He didn’t know I could read. He didn’t ask. So I didn’t tell him. I learned at his house, from his books. There’s a big one, a dictionary, and it’s got all the words, but when it’s a real thing, like a pig or a jug or a chair, there’s a picture. I only had to use the words I already knew to work out the rest. It took me three years, using every bit of free time I had! He didn’t say I wasn’t to read. All he told me was to keep things tidy. And then, the other day, he called me over to give me the letter and he said I was a good girl and I had to do a job for him and not tell anyone about it, and for that he promised me a gold quarter sovereign.

I had all that time walking into town to read the letter, but I didn’t, because it was sealed. I wouldn’t do that. I know that’s not right. But on the way back I was carrying the notary’s paper, the one you just heard, the will, and that wasn’t sealed, because it still had to be signed and witnessed and all. So I thought it wouldn’t hurt nobody if I read what was on it. After all, he didn’t say I wasn’t to know anything, just that I wasn’t to tell no one and that’s not the same, is it? I never thought I’d need what I learned so soon. How could I?

Then, when my parents told me he was dead, I was in such a state, I didn’t know what to do. I was that tired and upset that I fainted. Ask my Dad! I was sure the old boy hadn’t told nobody else about the quarter sovereign. What if I didn’t get it ‘cause I couldn’t prove what he’d promised? That was when I remembered what I’d read that morning, about the grieving and everything. And I thought, ‘Well, girl, if you can’t prove that with the quarter sovereign you’ll have to try your luck at getting some of the rest.’ How was I to know I’d be the only one who cared a fig about him?

And then I remembered the rest of what he’d written, about the debts being cancelled and the property redeemed and all. So as soon as I could, I told my friends. And they said they’d give it a go. They could dig. They’d dug his ditches and his garden every day! They could carry. They’d carried his firewood and his trunks and his boxes and his books and his trays of food every day! The will doesn’t say they weren’t to know what they were doing. It only says they’re to do it on their own decision. Well, it was their decision, so they should get everything he promised them, shouldn’t they? Of course they should! ...

... But I shouldn’t, ‘cause I was faking it and I’m sorry. I know what grieving is. I grieved for my little brother and for my auntie Beth. That was real. This wasn’t. I was just angry and needed an excuse to be in the house to see that nobody got up to nothing as they shouldn’t be getting up to. So you needn’t look at me like that! And you don’t need to tell me that I can’t have the money, because I’m not stupid. And anyway, I don’t want it. It never did him much good and I wouldn’t want to turn out the same way. I’d much rather we had a phish, a fiph ... you know, the fizzy thing what the notary said. I think that’s a kind of doctor and we never had one of those round here.

All I want is my quarter sovereign. That’s what he promised.” She paused for a moment before adding firmly: “I got plans for that!” |

|

A small thing can change destinies: a horseshoe, some loose gravel, a quarter sovereign – but a piece of paper can change them the most. And it is strange indeed how such a document may alter not only the future, but also the past. If the lender of last resort was never loved in his lifetime, he became respected in death. In place of the grasping miser there appeared a public benefactor. Instead of a vampire sucking life from the valley, the villagers now beheld a visionary, an erudite man of sciences and letters who was bringing life back. The wheezing, dried-up husk had become the horn of fruitful providence.

For the will was only part of the story. For years he had been planning his exit. The groundwork for the hospital was detailed in a whole series of papers that were found among his personal effects: its design, its administration, its functioning and staffing. He was utterly convinced that the church was wrong and that science was right. It was not repentance that would save the region, but knowledge. The sickness was not a punishment, it was a crime; a crime rooted in a lack of hygiene, bad practice, poverty and superstition. To stamp out the scourge, he had envisioned the hospital as a place of treatment, but beyond this, as a place of education in civics and public health.

This vision would revolutionise the region. Within a decade all houses had access to some kind of sanitation. Within two decades there were paved roads and covered sewers ran alongside them. The same period would see the county establish a civic board to maintain the provision and quality of drinking water. And it was not much later that the kerosene lamp made its appearance, and the cooperative society, and the public library. And though not all of these advances had their origin in the lender’s will, they were nonetheless locally attributed to him.

For the redemption of collateral and cancelling of debt caused a massive return of pride and spirit to the villages of those valleys. The defeat of the sickness turned out to be almost as much a question of morale as it was of medicine. Although the hospital turned out less grand than in the lender’s plans, the foundation being greatly circumscribed by the loss of so much collateral, yet it was effective from the outset. And the research physician, when he finally arrived a few years later, turned out not to be some venerable academic, but a most sympathetic young doctor in his twenties. Yes, a piece of paper, and the initiative of a quick-witted girl, would lead in time to the full economic recovery of the region.

But you’re not really interested in all that! You want to know what happened to the small messenger, don’t you? She eventually became a nurse and after a while, as nurses so often do, she married the young doctor and local legend records that she paid for her wedding dress with a gold quarter sovereign, exactly as she had planned ... for every respectable economic recovery needs a plan, and a respectable middle class. |

|

The Rolls behaved magnificently for the duration of the season, but failed to impress my mother, whom Quentin would encounter for the first time later that summer. She called it ‘your brother’s mastodon’ and did not like to travel in it at all. She was more at ease in a Land Rover anyway, but had set her heart on one of Mr Alec Issigoni’s new creations: the Morris Minor. And it was in her second Minor, black like its sister, that I learned to drive some twenty years later. Mother never did take to the Mini, she believed it encouraged indecency, by which she was referring, I think, to the ingress and egress of famous models. The Phantom II went back to its garage in Gidea Park after its grand tour and, apart from a single family Christmas at Blake Atherton, I cannot remember Haviland ever driving it.

© Edwin Drood

Illustration above:

Screw, the money lender, detail of a drawing by Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789-1856). In: Pierce Egan (1772-1849), The finish to the adventures of Tom, Jerry, and Logic, in their pursuits through life in and out of London, page 192. Reeves and Turner, London, 1887 At the Internet Achive. |

|

| |

Rolls Royce Phantom II.

After a newspaper advertisement,

"Rolls-Royce, the best car in the world", 1929. |

Edwin Drood's Column, the blog by The Mysterious Edwin Drood,

at My Favourite Planet Blogs.

We welcome all considerate responses to this article

and all other blogs on My Favourite Planet.

Please get in contact. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

Views of blog authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers

or anyone else at, on or in the vicinity of My Favourite Planet. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms

in Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr |

| |

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de |

| |

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece +30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr |

| |

| |

|