|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Vitruvius |

|

| |

Vitruvius

Vitruvius (circa 80-70 BC - after 15 BC) was a Roman architect, engineer and writer in the 1st century BC. He is known only as the author of De Architectura (On Architecture), his only known work, usually referred to as Ten Books on Architecture. The ten-volume treatise on architecture, probably written around 15 BC, has survived complete.

No other ancient author provides information about his life or work [1], and even his full name is not known: the name given him by modern scholars, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, is conjectural [2]. Attempts to identify him from inscriptions mentioning people called Vitruvius (not an uncommon name) have not been substantiated. There is no known surviving ancient portrait of him.

The little that is known about him has been taken from references in De Architectura itself. In the preface to Book 1, he dedicated the work to Emperor Augustus (reigned 27 BC - 14 AD), and stated that he was known to Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), who adopted his great nephew Augustus (then still known as Octavian) as his son in his will. He added that he had been recommended to Augustus by the emperor's sister, Octavia Minor. He also mentioned that he had served in the Roman army, constructing and maintaining artillery equipment, for which he was well paid:

"And so with Marcus Aurelius, Publius Minidius, and Gnaeus Cornelius, I was ready to supply and repair ballistae, scorpiones, and other artillery, and I have received rewards for good service with them. After your first bestowal of these upon me, you continued to renew them on the recommendation of your sister. Owing to this favour I need have no fear of want to the end of my life ..."

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, Book 1, Preface, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

From the preface, it appears that Vitruvius began writing De Architectura during his retirement from military service, and after Augustus had gained sole control over the Roman Empire and victory in the series of civil wars which followed Caesar's assassination. As part of his policy of consolidation, in order to maintain peace and his own power, Augustus initiated several building projects around the empire, and is said to have claimed on his deathbed: "I found a Rome of bricks; I leave to you one of marble." [3] Addressing the emperor, Vitruvius wrote that he undertook his work in support of this policy:

"But when I saw that you were giving your attention not only to the welfare of society in general and to the establishment of public order, but also to the providing of public buildings intended for utilitarian purposes, so that not only should the State have been enriched with provinces by your means, but that the greatness of its power might likewise be attended with distinguished authority in its public buildings, I thought that I ought to take the first opportunity to lay before you my writings on this theme ...

... and being thus laid under obligation I began to write this work for you, because I saw that you have built and are now building extensively, and that in future also you will take care that our public and private buildings shall be worthy to go down to posterity by the side of your other splendid achievements. I have drawn up definite rules to enable you, by observing them, to have personal knowledge of the quality both of existing buildings and of those which are yet to be constructed. For in the following books I have disclosed all the principles of the art."

Book 1, Preface, sections 2-3.

He indicated something of his age and appearance at the time of writing when discussing the career of Deinokrates, one of Alexander the Great's architects:

"This was how Dinocrates, recommended only by his good looks and dignified carriage, came to be so famous. But as for me, Emperor, nature has not given me stature, age has marred my face, and my strength is impaired by ill health. Therefore, since these advantages fail me, I shall win your approval, as I hope, by the help of my knowledge and my writings."

Book 2, Introduction, section 4.

Although Vitruvius has been critized by several modern scholars for what they considered his poor writing style, described by one as "turgid and pompous rhetoric" [4], his work remains the most important ancient source on Greek and Roman architecture and engineering. The work is particularly prized for its descriptions of construction materials, techniques and components, from foundations to roofs, including proportions, symmetry, acoustics, decoration and colours; types of buildings, engineering works and machinery; and considerations such as climate, geographical situation and water supply for the planning of cities, city walls and individual buildings.

Vitruvius is the only source of information about several specific ancient buildings and engineering works, as well as individual architects, engineers and artists. Despite his dry style, he pepped the work up with a number of entertaining anecdotes, some of which have become famous, including those concerning Euripides and Archimedes [5].

Like many ancient works, De Architectura appears to have been largely forgotten after the fall of the Roman Empire, but some copies survived. Many of the surviving manuscripts derive from an existing copy written in the palace scriptorium of Charlemagne in the early 9th century. The work was known by and influenced several Medieval scholars, indicating that copies were available around Europe, presumably in monastery libraries, and was to have a much greater influence on architects and artists from the Renaissance. |

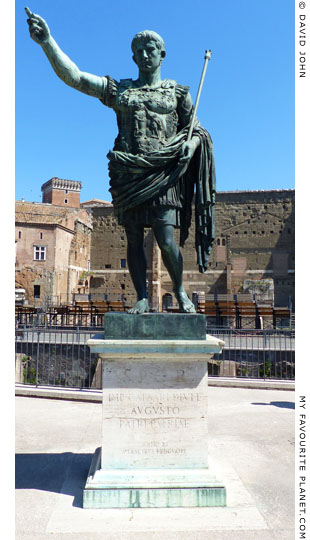

Bronze statue of Emperor Augustus

at the Forum of Octavian Augustus,

via dei Fori Imperiali, Rome.

A modern copy, set up in the 1930s,

of an over-lifesize marble statue of

the 1st century, known as "Augustus

of Prima Porta". Discovered in 1863

in the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta, north

of Rome, it is now in the Braccio Nuovo

(New Wing) of the Chiaramonti Museum,

Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 2290. |

| |

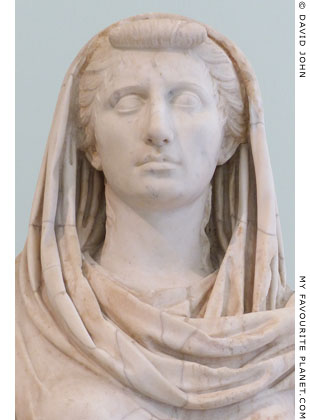

Detail of a marble statue, known as

"the Sybil", a portrait of Octavia Minor,

sister of Augustus.

Early 1st century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6125. Farnese Collection. |

| |

| |

Caryatids in the first illustrated edition of Vitruvius by

Fra Giovanni Giocondo, published in Venice in 1511.

Reprinted in Morris Hicky Morgan's 1914 translation. |

| |

The first printed edition was published in 1486 by the Veronese scholar Fra Giovanni Sulpitius (flourished around 1470-1490), and the first illustrated version was produced in Venice in 1511 by the Dominican friar Fra Giovanni Giocondo (circa 1433-1515). Following editions in Italian in the 1520s, German in 1528, French in 1547, and Spanish in 1582, the first introduction to Vitruvius for English readers was The elements of architecture, a treatise on his architectural principles by the English diplomat Sir Henry Wotton (1568-1639), written while he was the ambassador of King James I in Venice (1604-1624), and published in 1624.

A 1903 reprint: Henry Wotton, The elements of architecture, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1903. At the Internet Archive.

The first English translation of Vitruvius was An abridgment of the Architecture Of Vitruvius, published in 1692, a summary based on the authoritative 1673 French version by Claude Perrault (1613-1688). Described as being "Printed for Abel Small and T. Child, at the Unicorn in St. Paul's Church-yard, 1692", only electronic text editions (all of which appear to have been copied from the same source, perhaps the scan at Project Gutenberg), or paper copies printed from them, appear to be currently available. Some sources give the publishers' names as "Abel Swall" and "Timothy Child", but none seem to mention the author, who appears to be named Philebert de l'Orme. At the back of the online editions is an address to the reader, a preface one imagines belongs at the beginning ot the book:

"To the Reader.

Abridgments of Vitruvius have been formerly printed, but none of them have followed the design which Philebert de l'Orme has given in his Third Book: He desires that in abridging Vitruvius the matters which this Author treats of confusedly should be put into order..."

An abridgment of the Architecture Of Vitruvius. At the Internet Archive.

Architect William Newton (1735-1790) was the first to provide an unabridged English translation of De Architectura, although it took him over two decades. His first volume was published in 1771, but the second was completed after his death by his James Newton, who also created most of the illustrations, and published in 1791. Newton also wrote Commentaires sur Vitruve in French, published in 1780. As an architect he worked with James "Athenian" Stuart on the building of the Greenwich Infirmary, and edited Stuart's The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated after the author's death.

By the 1820s scholars had gained a better understanding of ancient Greek and Roman history, literature, art and architecture due to works written by travellers to the Mediterranean countries and early pioneers of art history, epigraphy and archaeology, as well as the practical experiences of Neoclassical architects. The one-volume translation by the architect Joseph Gwilt (1784-1863), published in 1826, was a fresh attempt to render Vitruvius into modern English in the light of this wealth of newly-acquired knowldege of the Roman architect's world, and replaced the previous attempts as the standard reference. |

|

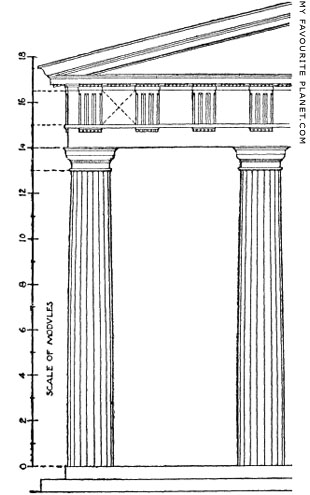

The Doric order according to Vitruvius.

Source:

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture,

translated by Morris Hicky Morgan and

Albert A. Howard. Illustrations by Herbert

Langford Warren. Havard University

Press and Oxford University Press, 1914. |

|

Morris Hicky Morgan's 1914 translation is available in paperback, published by Dover Publications, New York, 1960 (see also online editions below). It remains useful, accessible, popular and affordable, but has been recently been joined by two new critical translations:

Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe, Vitruvius: 'Ten Books on Architecture'. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Vitruvius, On Architecture, translated by Richard Schofield, with an introduction by Robert Tavernor. Penguin Classics, 2009.

Ten books on architecture can be read online.

In English:

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture, translated by Morris Hicky Morgan and Albert A. Howard. Havard University Press and Oxford University Press, 1914.

The entire work on one web page, with an introduction, illustrations and index at Project Gutenberg.

This edition is also available on other websites, including Wikisource and Perseus Digital Library.

See also Bill Thayer's excellent English version, Vitruvius: On Architecture, at his LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

In Latin:

Vitruvius, de Architectura. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

Vitruvius Pollio, De Architectura, edited by F. Krohn. B.G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1912. At Perseus Digital Library.

De architectura libri decem, edited by C. Fensterbusch, Darmstadt, 1964-1976. At Bibliotheca Augustana, Hochschule Augsburg. |

|

|

| |

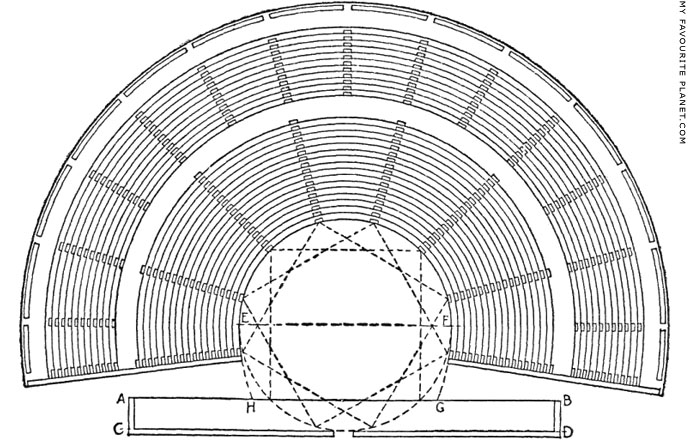

The plan of a Greek theatre according to Vitruvius.

Source: Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture, translated by Morris Hicky Morgan

and Albert A. Howard, with illustrations by Herbert Langford Warren.

Havard University Press and Oxford University Press, 1914. |

| |

Via Vitruvio in central Milan, Italy. |

| |

| Vitruvius |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Ancient authors on Vitruvius

It is widely thought that the Ten Books on Architecture was used as a source by Pliny the Elder, particularly on construction methods and wall painting, but he does not mention Vitruvius. The name Virtuvius appears as a source in a table of contents in some editions of Pliny's Natural history, but it is uncertain whether Pliny compiled this himself.

The prominent Roman civil engineer, author, general and politician Sextus Julius Frontinus (circa 40 - 103 AD) evidently knew of Vitruvius' work, and mentions him in De aquaeductu (On aqueducts) as "Vitruvius, the architect" in relation to units of measure used by plumbers.

See:

Sextus Julius Frontinus, The Aqueducts of Rome, Book I, section 25. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

In the 3rd or 4th century Marcus Cetius Faventinus wrote brief summaries of parts of the Ten Books on Architecture in his Artis architectonicae privatis usibus adbreviatus liber (Abbreviated book of the architectural arts for private uses). Divided into 29 parts, the work was compiled as a practical handbook for builders of private houses, and excluded information about public buildings, engineering and theoretical matters.

It was apparently Faventinus' work, rather than that of Vitruvius, which was later used as a source by Palladius and Isidorus (Isidore of Seville). A manuscript of the work, discovered in 1871, contains no biographical information about Vitruvius or Faventinus himself.

See:

Marcus Cetius Faventinus. In German at Wikipedia.

Hugh Plommer, Vitruvius and later Roman building manuals. Cambridge University Press, 1973.

2. Virtuvius' full name

Faventinus refers to his sources as "Vitruvius Polio aliique auctores", which may mean either "Vitruvius Polio and other authors" or "Vitruvius, Polio, and other authors". The main argument for the former reading is that the majority of Faventinus' work is taken from Vitruvius.

3. Augustus' Rome of marble

"The city, which was not built in a manner suitable to the grandeur of the empire, and was liable to inundations of the Tiber, as well as to fires, was so much improved under his administration, that he boasted, not without reason, that he 'found it of brick, but left it of marble'. He also rendered it secure for the time to come against such disasters, as far as could be effected by human foresight.

A great number of public buildings were erected by him, the most considerable of which were a forum, containing the temple of Mars the Avenger, the temple of Apollo on the Palatine hill, and the temple of Jupiter Tonans in the Capitol. The reason of his building a new forum was the vast increase in the population, and the number of causes to be tried in the courts, for which, the two already existing not affording sufficient space, it was thought necessary to have a third."

Suetonius (Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, circa 69 - after 122 AD), De Vita Caesarum (The twelve Caesars), Divus Augustus, chapter 29, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Bythinian historian Cassius Dio also uses this quote when describing the death of Augustus, but adds a quite different interpretation:

"At any rate, from this or some other cause he [Augustus] became ill, and sending for his associates, he told them all his wishes, adding finally: 'I found Rome of clay; I leave it to you of marble.' He did not thereby refer literally to the appearance of its buildings, but rather to the strength of the empire. And by asking them for their applause, after the manner of the comic actors, as if at the close of a mime, he ridiculed most tellingly the whole life of man."

Cassius Dio (Cassius Dio Cocceianus, 155-235 AD), Roman History, Book 56, chapter 30. Loeb Classical Library, Volume VII, 1924. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

4. "turgid and pompous rhetoric"

Albert A. Howard in his preface to Morris Hicky Morgan's translation of The ten books on architecture, which he completed after Morgan's death.

5. Vitruvius on Euripides and Archimedes

For his mention of Euripides' tomb in Macedonia (Book 8, chapter 3), see A brief history of Pella.

For his anecdote on Archimedes' eureka moment (Book 9, Introduction), see Ancient Stageira gallery, page 21. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|