|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Pliny the Elder |

|

back |

Pliny the Elder |

|

|

| |

Pliny the Elder

The Roman author Gaius Plinius Secundus (23 - 25 August 79 AD) is usually referred to in English as Pliny, or as Pliny the Elder to distinguish him from his nephew Pliny the Younger [1]. He is best known for his only surviving work, the encyclopedic 37 volume Naturalis Historia (Natural History), written in Latin and published around 77-79 AD, which he dedicated to the newly-crowned emperor Titus (reigned 79-81 AD). This influential work remains an important source for scholars of the ancient history of science and culture.

Pliny the Elder was a biographer, historian, naturalist and natural philosopher, as well as a lawyer, provincial governor and army and naval commander of the early Roman Empire, and a personal friend of Emperor Vespasian (reigned 69-79 AD) and his son and successor Titus. Born in Novum Comum (Como, northern Italy), he was the son of Gaius Plinius Celer, a member of the equestrian order of equites (knights), and his wife Marcella. He never married and had no children. In his will he adopted his nephew, Pliny the Younger, who inherited his estate and considerable wealth.

After his education in Rome, Pliny served as an infantry and cavalry officer in Germania during the reigns of Claudius (41-54 AD) and Nero (54-68 AD), and wrote De jaculatione equestri (Throwing the javelin from horseback), a treatise on the use of the javelin by cavalry. On his return to Rome, around 56-59 AD, he practised as a lawyer and wrote a two-volume biography of his former commander and patron Publius Pomponius Secundus (a poet and author of tragedies, and a brother-in-law of Caligula), and Bella Germaniae (History of the German Wars) in twenty volumes, which was used as a source by the historians Tacitus and Suetonius.

During Nero's "reign of terror", his deposition in 68 AD and the consequent civil war (the Year of the Four Emperors, 69 AD), Pliny kept a low profile, held no public office and wrote on politically safe subjects such as a three-volume educational manual on rhetoric, Studiosus (The student, later divided into six books because of its length), and an eight-volume work on grammar, Dubii sermonis (On doubtful phraseology or Ambiguity in language). None of these works have survived.

When Vespasian became emperor Pliny was appointed as a procurator (governor) of a number of imperial provinces. The number (perhaps four) and locations of his procuratorships are uncertain, but he is known to have governed in Hispania Tarraconensis (northern and eastern Spain) [2], and perhaps Gallia Narbonensis (southeastern France), Africa (north Africa) and Gallia Belgica (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands).

During this period Pliny also added thirty one books to the unfinished Histories by Aufidius Bassus [3]. He did not publish this work, leaving it, as he says in the preface to the Natural History, to his heir Pliny the Younger. He claims he did this to avoid the accusation of ambition, but may have feared that it was too politically controversial.

He probably returned to Rome in 75 or 76 AD, and is thought to have published the first version of the first ten books of the Natural History in 77 AD. He was busy enlarging and revising the work when he was appointed as prefect (commander or admiral) of the fleet at Misenum (Cape Miseno), the largest base of the Roman navy, at the northwest end of the Bay of Naples.

According to the letters of Pliny the Younger [see note 1], he died in his 56th year during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 25 August 79 AD, which destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. He had been staying with his sister and nephew at Misenum, and was preparing to sail to investigate the eruption when he received a plea for help from a friend named Rectina, who with her family was trapped by the catastrophe at their villa at Stabiae, near Pompeii. During the rescue attempt the wind prevented his ship leaving the shore, and he is said to have died as a result of volcanic fumes, although his companions survived.

The final version of the Natural History was published after his death by Pliny the Younger. It is a vast work and a wide-ranging attempt to provide a comprehensive record of contemporary knowledge of the natural world, its resources and their exploitation by humans. Pliny claimed to have been the first Roman to have written such an encyclopedia, and such comprehensive works had previously only been attempted by Greeks.

The fields of natural sciences discussed by Pliny include botany, zoology, anthropology, human physiology, astronomy, geography, geology and mineralogy. He also describes how natural resources [4] such as water, animals, plants, wood, stone and metals are exploited in agriculture, medicine, mining, engineering, building and art. His mentions of ancient painters, sculptors and architects and their works (see below) continue to provide one of the most extensive ancient sources (along with Vitruvius and Pausanias) of information and debate - and often consternation - for historians of Greek and Roman art.

His travels around parts of the empire on his official duties provided him with material for his writing, and several accounts of phenomena, locations, buildings, artworks and events in the Natural History, such as a solar eclipse in Campania in 59 AD (Natural History, Book 2, chapter 72), are thought to be first-hand reports based on his own experiences and observations. However, most of the information in the work is based on books by several earlier authors.

Although the Natural History includes historical surveys of human activities such as sculpture and painting, it is not primarily a work of history. The word "history" in the title is often seen to mean enquiry, in the same way as the Greek title of the Histories of Herodotus also originally meant Enquiries.

The work has survived in around 200 Medieval manuscripts, the earliest dating from the 8th or 9th century, although some passages and abstracts appeared in works from as early as the 3rd century. They contain many errors, corruptions and alterations made by copyists, but no definitive version considered as closest to the original has been identified. The first printed edition was published in Venice in 1469 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer.

There is no known surviving ancient portrait of Pliny. A selection from Pliny's Natural history in English:

Pliny the Elder, Natural History: A selection. Translated with an introduction and notes by John F. Healey. Paperback. Penguin Classics, 1991.

Pliny's Natural history can be read online.

In English:

Pliny, The natural history. Translated by John Bostock and H. T. Riley. Taylor and Francis, London, 1855. At Perseus Digital Library. With notes.

Pliny's Natural History. Loeb Classical Library edition, in 10 volumes. Translated by H. Rackham (Volumes 1-5, 9), W. H. S. Jones (Volumes 6-8) and D. E. Eichholz (Volume 10). Harvard University Press, Massachusetts and William Heinemann, London, 1949-1954.

The entire work on one web page, with an introduction and table of contents. At Jon Lange's fascinating Masseiana website.

In Latin:

Pliny the Elder, The natural history. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

Naturalis Historia. Edited by Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1906. At Perseus Digital Library.

|

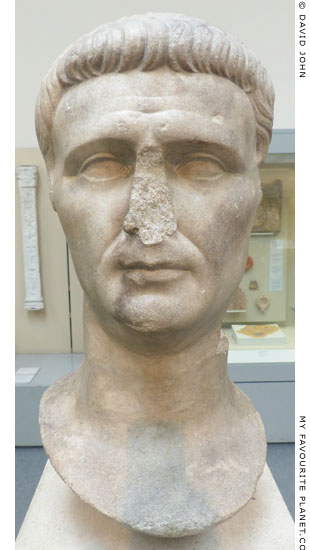

Marble head of Emperor Claudius.

From a statue. Found in the cella of the

temple of Athena Polias in Priene, Ionia,

Asia Minor. Circa 50 AD. One of a series

of portraits of members of the Julio-

Claudian dynasty, the first imperial

family, set up by the people of Priene.

Excavated 1868/1869. Height 44.45 cm.

British Museum.

1870.3-20.200 (Sculpture 1155).

Donated in 1870 by the Society of Dilettanti. |

| |

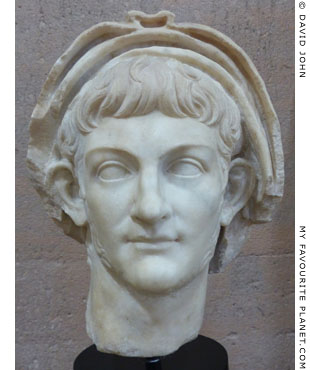

Marble portrait head from a statue

of Emperor Nero as a priest with

capita velato (covered head). [5]

Circa 60 AD. Excavated in the Julian

Basilica, in the Forum of Ancient Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. S-1088. |

| |

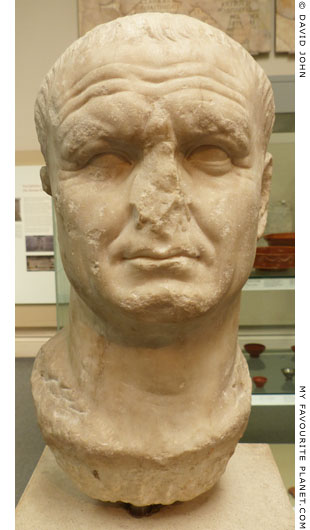

Marble head of Emperor Vespasian.

From Carthage, Tunisia. Circa 70-80 AD.

Height 45.72 cm.

The larger than lifesize head from

a statue may have been re-carved

from a portrait of Nero after his

suicide and damnatio memoriae.

British Museum.

Inv. No. 1850.3-4.35 (Sculpture 1890).

Bequeathed by Sir Thomas Reade. [6] |

| |

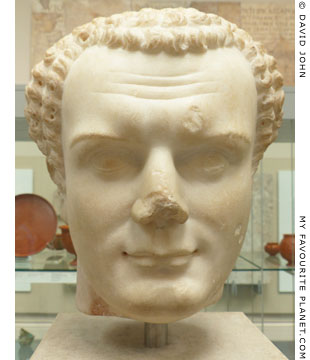

Marble head of Emperor Titus.

From Utica, Tunisia. Circa 70-81 AD.

Height: 30.48 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1909.6-10.1.

Purchased in 1909 from W. Caudery & Co. |

| |

| |

|

|

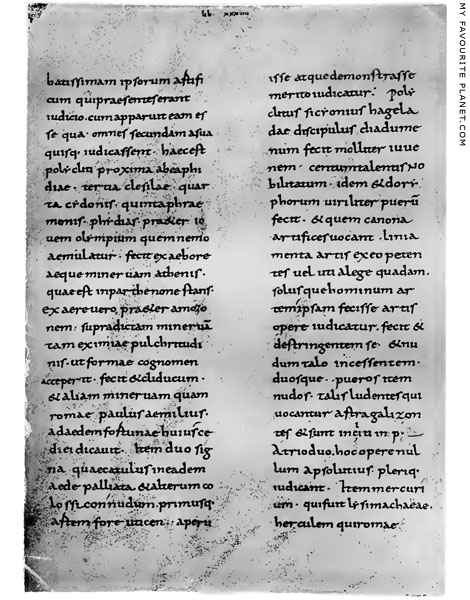

A page from the Bamberg Codex (Codex Bambergensis, Msc. Class. 42*), a hand-written manuscript containing only Books 32-37 of Pliny the Elder's Natural history, created in the second quarter of the 9th century AD in the palace scriptorum of Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious in Aachen. It is one of the oldest surviving manuscripts of Pliny’s work and the only one containing the ending of Book 37. It is named after the state library, the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg, Bavaria, Germany, in which it was discovered in 1831 by the German classical philologist Ludwig von Jan (1807-1869), a student of Friedrich Thiersch. Jan's discovery enabled Julius Sillig to compile the first complete edition of the Natural history in modern times, published in Leipzig, 1831-1836.

A digital edition of the codex is currently being created by the Plinius project. See:

hcmid.github.io/plinius/manuscripts.html

For Ludwig von Jan's search for manuscripts in European libraries, see:

Michael D. Reeve, The editing of Pliny’s Natural History. In: Revue d'histoire des Textes, Volume 2 (nouvelle série Tome II), Pages 107-179, particularly 111-112. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Belgium, 2007. PDF available at brepolsonline.net.

Image source: Katherine Jex-Blake and Eugenie Sellers, The elder Pliny's chapters on the history of art. Translation by K. Jex-Blake, with commentary and historical introduction by E. Sellers and additional notes contributed by Dr. Heinrich Ludwig Urlichs. Macmillan & Co., London, 1896. |

|

|

| |

Pliny

the Elder |

Dates of artists mentioned

by Pliny the Elder |

|

|

|

Pliny the Elder gave the dates at which Greek artists flourished or were at the height of their careers, calculated on Olympiads, the four-year cycle of the sequence of ancient Olympic Games, which according to tradition began in 776 BC. He sometimes added "the year of Rome", calculated on the number of years since the legendary foundation of the city (753 BC). As is the case of much of what Pliny wrote, many of the names and dates have been questioned by modern scholars.

Further information about many of these artists can be found in the Ancient Greek artists pages.

I have yet to find a reliable source for the conversion of all Olympiads into modern calendar years [7].

If you know of one, please get in contact.

B: Sculptors in bronze, Natural History, Book 34 (mostly chapter 19)

P: Painters, Natural History, Book 35

M: Sculptors in marble, Natural History, Book 36 |

|

| |

50th Olympiad

(580 BC) |

M: Dipoenos and Skyllis |

|

| |

60th Olympiad

(540 BC) |

M: Bupalus and Athenis, sons of Archermus |

|

| |

83rd Olympiad

(448 BC) |

B: Pheidias, Alkamenes, Kritias, Nesiotes (perhaps Nestocles), Hegias |

|

| |

87th Olympiad

(430 BC) |

B: Agelades, Callon, Gorgias the Laconian |

|

| |

89th Olympiad

(422 BC) |

P: Demophilus of Himera, Neseus of Thasos |

|

| |

90th Olympiad

(420 BC) |

B: Polykleitos, Phradmon, Myron, Pythagoras, Skopas, Perellus (probably Perillos), Lycius (pupil of Myron)

Pupils of Polykleitos: Argios, Asopodorus (these two may have been one person, the Argive Asopodorus), Alexis, Aristides, Phrynon, Dinon, Athenodoros, Demeas the Clitorian

P: "... before the 90th Olympiad, there were other celebrated painters, Polygnotus of Thasos..." (80th Oympiad?)

P: Aglaophon, Cephisodorus, Erillus, and Evenor, the father of Parrhasius |

|

| |

93rd Olympiad

(408 BC) |

P: Apollodorus of Athens |

|

| |

95th Olympiad

(400 BC) |

B: Naukydes, Dinomenes, Kanachos, Patroklos

P: Zeuxis of Heraclea ("By some writers he is erroneously placed in the 89th Olympiad") |

|

| |

102nd Olympiad

(372 BC) |

B: Polykles, Kephisodotos (the Elder), Leochares, Hypatodoros |

|

| |

104th Olympiad

(364 BC) |

B: Praxiteles, Euphranor

P: Euphranor of Isthmia, Cydias, Antidotus, a pupil of Euphranor, teacher of Nikias of Athens |

|

| |

107th Olympiad

(352 BC) |

B: Aetion, Therimachos

M: Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, Leochares (Mausoleum in Halicarnassus)

"Mausolus died in the 2nd year of the 107th Olympiad, being the year of Rome 403."

P: Aetion, Therimachus |

|

| |

112th Olympiad

(332 BC) |

P: Apelles of Kos, Protogenes (Rhodes); possibly Nikias of Athens (pupil of Antidotus) or another Nikias |

|

| |

113th Olympiad

(328 BC) |

B: Lysippus, his brother Lysistratus (of Sicyon), Sthennis, Euphron, Eucles, Sostratus, Ion, Silanion (Athenian; Zeuxis was his pupil) |

|

| |

121st Olympiad

(296 BC) |

B: Eutychides, Euthycrates, Laippos, Kephisodotos (the Younger), Timarchos, Pyromachos |

|

| |

"The practice of this art [bronze sculpture] then ceased

for some time, but revived in the 156th Olympiad..." |

| |

156th Olympiad

(154 BC) |

B: Antaeus, Kallistratos, Polykles, Athenaeus, Callixenus, Pythocles, Pythias, Timocles |

|

|

| |

Pliny

the Elder |

Pliny on the Earth, other worlds,

the universe, infininty and everthing |

|

|

|

Pliny began his Natural history with an attempt to describe or define the world. Like other ancient authors, he used the Latin word mundus, corresponding to the Greek kosmos (κόσμος), sometimes to mean the Earth and its immediate environment, and at other times what we now refer to as the universe. He was aware that the world was a globe spinning in space, and believed that the universe was infinite in size, but also that it had existed and would also exist for all time without beginning or end, and that as a whole it was a deity.

"The world, and whatever that be which we otherwise call the heavens, by the vault of which all things are enclosed, we must conceive to be a Deity, to be eternal, without bounds, neither created, nor subject, at any time, to destruction. To inquire what is beyond it is no concern of man, nor can the human mind form any conjecture respecting it. It is sacred, eternal, and without bounds, all in all; indeed including everything in itself; finite, yet like what is infinite; the most certain of all things, yet like what is uncertain, externally and internally embracing all things in itself; it is the work of nature, and itself constitutes nature.

It is madness to harass the mind, as some have done, with attempts to measure the world, and to publish these attempts; or, like others, to argue from what they have made out, that there are innumerable other worlds, and that we must believe there to be so many other natures, or that, if only one nature produced the whole, there will be so many suns and so many moons, and that each of them will have immense trains of other heavenly bodies. As if the same question would not recur at every step of our inquiry, anxious as we must be to arrive at some termination; or, as if this infinity, which we ascribe to nature, the former of all things, cannot be more easily comprehended by one single formation, especially when that is so extensive. It is madness, perfect madness, to go out of this world and to search for what is beyond it, as if one who is ignorant of his own dimensions could ascertain the measure of any thing else, or as if the human mind could see what the world itself cannot contain.

That it has the form of a perfect globe we learn from the name which has been uniformly given to it, as well as from numerous natural arguments. For not only does a figure of this kind return everywhere into itself and sustain itself, also including itself, requiring no adjustments, not sensible of either end or beginning in any of its parts, and is best fitted for that motion, with which, as will appear hereafter, it is continually turning round; but still more, because we perceive it, by the evidence of the sight, to be, in every part, convex and central, which could not be the case were it of any other figure.

The rising and the setting of the sun clearly prove, that this globe is carried round in the space of twenty-four hours, in an eternal and never-ceasing circuit, and with incredible swiftness. I am not able to say, whether the sound caused by the whirling about of so great a mass be excessive, and, therefore, far beyond what our ears can perceive, nor, indeed, whether the resounding of so many stars, all carried along at the same time and revolving in their orbits, may not produce a kind of delightful harmony of incredible sweetness. To us, who are in the interior, the world appears to glide silently along, both by day and by night."

He goes on to discuss the elements, the heavens, with its planets, stars and constellations, and God...

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 2, chapters 1-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

The notes to this edition discuss at length some of the concepts used by Pliny, with reference to other writers such as Plato and Aristotle. |

|

|

| |

Pliny

the Elder |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (61 - circa 112 AD), born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo, usually referred to in English as Pliny the Younger, was the nephew of Pliny the Elder. Born in Novum Comum (Como, Northern Italy), he was the son of Lucius Caecilius Cilo and Plinia Marcella, a sister of Pliny the Elder. His father died when he was a boy, and his uncle helped raise and educate him. He was a lawyer, magistrate, author, poet and orator. Like his father and uncle, he was a member of the aristocratic order of equites (knights). He held several of the highest imperial offices, including senator, quaestor, consul and governor of Bithynia and Pontus province. It is thought that he died while serving in Bythinia, northwestern Anatolia (Asia Minor).

Many of the letters he wrote to friends and associates have survived, collected in ten books known as the Epistulae (Letters), the last of which consists entirely of letters to and from Emperor Trajan. In two letters (Epistulae, Book 6, letters 16 and 20), written to Tacitus around 106 AD, he decribes the eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 25 August 79 AD, which he witnessed from Misenum, and Pliny the Elder's death. He wrote that he decided to stay and work at home rather than join his uncle's expedition.

The letters in Latin and English: Pliny the Younger : Letters. At attalus.org.

2. Pliny as procurator of Hispania Tarraconensis

Pliny the Younger mentions that his uncle was procurator of Hispania Tarraconensis in a letter to Baebius Macer (Epistulae, Book 3, letter 5), in which he lists Pliny the Elder's books in chronological order.

3. Aufidius Bassus

Little is known about the life and lost works of Aufidius Bassus. He lived during the reign of Tiberius (14-37 AD), was an Epicurean, a friend of Seneca, and much admired in Rome. He wrote a Bellum Germanicum, about the Roman conquest of Germania, and a Histories (or History of our own times), probably covering the period between the Roman civil wars or the death of Julius Caesar and the time of Tiberius. Bassus died after a long illness, leaving his Histories unfinished. Pliny's additional books probably continued the account up to the reign of Vespasian.

4. "Natural resources"

Nature has been seen by humans throughout history as a source of necessities and luxuries to be exploited, mostly unquestioningly, often as a god-given right or duty. Such attitudes, of course, are now being widely opposed.

5. The head of Nero from Corinth

The head is similar to one excavated in 1869 in Rome, dated around 54-59 BC, which may have originally stood in the temple of Apollo Palatinus (Palatine Apollo) on the Palatine Hill. Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 616.

6. The head of Vespasian in the British Museum

According to the museum label, the head of Vespasian was "bequeathed by Sir Thomas Reade". However, the Collection online of the British Museum website tells us that it was excavated by Sir Thomas Reade (1782-1849, British consul in Tunis 1844-1849) and purchased in 1850 from John Doubleday (1797-1856, a restorer and curator at the British Museum). In the short biography of Thomas Reade we learn that "he collected many antiquities, including numerous items from Carthage excavated by Nathan Davis".

Acccording to a British Museum catalogue, the head was found during excavations undertaken at Carthage by Sir Thomas Reade in 1835-1836, and purchased by the museum in 1850.

A. H. Smith, A catalogue of sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Volume III, No. 1890, page 155 and Plate XX. British Museum, 1901. At the Internet Archive.

The format of inventory numbers of objects ("Museum number") in the Collection online also differs from that on labels. On the label of the Vespasian head, the number is 1850.3-4.35, while in the database it is 1850,0304.35.

The British Museum does an exemplary job in providing a comprehensive online database of its enormous collection. It contains detailed information, photos and illustrations of most of the objects in the museum, including many that are not on display. We wish all museums would offer such an excellent public service. Compiling and maintaining such a database involves an enormous amount of work and expertise in several academic and technical fields, so it not surprising that there remain some gaps and inconsistencies in the documentation. Often the information varies from that on the museum's labelling and in other documents and publications.

Collection online at the British Museum website.

7. Olympiad dates

Here are a few more dates of Olympiads.

Olympiad

1

10

14

15

17

18

20

23

25

30

33

37

38

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49 |

Date (BC)

776

740

724

720

712

708

700

688

680

660

648

632

628

620

616

612

608

604

600

596

592

588

584 |

|

Olympiad

50

58

60

65

70

71

72

73

74

75

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

93

94

95

96

99 |

Date (BC)

580

548

540

520

500

496

492

488

484

480

460

456

452

448

444

440

436

432

428

424

420

408

404

400

396

384 |

|

Olympiad

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

120

121

124

128

130

131

140

145

150

156 |

Date (BC)

380

376

372

368

364

360

356

352

348

344

340

300

296

284

268

260

256

220

200

180

154 |

| |

Dates based on various sources, including labelling and literature of the Museum of the History of the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympia. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|