|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Pergamon > gallery 1 |

| Pergamon gallery 1 |

Pergamon |

|

|

35 of 37 |

|

|

|

| |

The Asklepieion archaeological site, Bergama (Pergamon). |

| Asklepieion archaeological site |

Opening times: daily 8:30 - 17:30

Admission: 15 Turkish lira

An uphill walk or drive of about 2 kilometres southwest of the centre of Bergama, along a road which starts next to the Kurşunlu Cami mosque, opposite the post office (PTT) on Bankalar Cad, the town's main street.

The start of the road is marked by a signpost to the Asklepieion and a statue of the Greek physician Galen (see below) on Cumhuriyet Square.

There is a free car park, as well as toilets, a cafe and souvenir shops opposite the entrance to the site (see next page) outside the entrance to the site.

The Asklepieion (also asclepieion, asclepeion or asclepion; Greek, Ἀσκληπιεῖον, Asklepieion; Latin, aesculapium) was an ancient healing and cult centre, sacred to Asklepios (Ἀσκληπιός; Latin, Aesculapius), the Greek god of healing and son of Apollo. Approached by a sacred way, the Via Tecta, the sanctuary contained a round Temple of Asklepios (named Asklepios Soter or Zeus Soter Asklepios), as well as one to his son, the mysterious hooded youth Telesphoros (see below). There was also a spring of slightly radioactive water used for therapeutic purposes, a library and a small theatre.

The cult of Asklepios had a mysterious and mystical association with snakes (as did those of other Greek gods such as Athena), many of which were kept at the sanctuary. Therapy at the centre included the interpretation of dreams.

You can see the types of medical instruments used in antiquity in the photo below.

The Asklepieion is thought to have been founded in the 4th century BC by a certain Archias (Ἀρχίας) [1], who is said to have brought the Asklepios cult from its main centre at Epidauros (Ἐπίδαυρος, Latin Epidaurus; today Epidavros), in the northwestern Peloponnese. Eumenes II (ruled 263-241 BC) elevated the cult to a state religion.

Further enhancements were made to the healing centre by Roman emperors, including Hadrian (reigned 117-138 AD), who supported and financed building works at the Asklepieion. He is thought to have visited Pergamon during his travels through Asia Minor in 123 AD.

The spread of the cult of Asklepion and the establishment of such healing centres around the Greek world from the late Classical period had important practical aspects. The presence of an Asklepieion in an ancient city was the equivalent of a modern hospital for its citizens. It was also a source of prestige as well as considerable income, particularly in the case of Epidauros and Pergamon, to which rich people came from far afield to be cured, and in return paid, or donated as a religious offering, large sums of money and other gifts.

Several locations since time immemorial had been thought of as especially beneficial for the treatment of diseases, due to particular local properties, such as their waters, and the traditional associations they had acquired with deities, nymphs and other supernatural beings. With the scientific advancements of medical theories in Classical and Hellenistic times, the practice of medicine began to be systematized and standardized to a certain extent, and one could speak of a medical industry.

The profession of medicine at these centres was a male preserve, and it seems no accident that other healing deities, such as the health goddess Hygieia (Ὑγιεία, see photo below), came to be seen as subservient (sons and daughters) to Asklepios, who became the exemplary and primary divine master and patron of the healing arts. The new medical science of Hippocrates and the cult of Asklepios in many places replaced the more ancient local ways.

The Asklepieion was excavated in 1927 by the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand (1864-1936), who also discovered the Arsenal on the Pergamon Acropolis.

Some of the images relating to Asklepios

previously on this page can now be seen on

the Asklepios page of the MFP People section. |

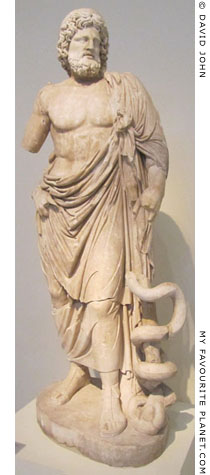

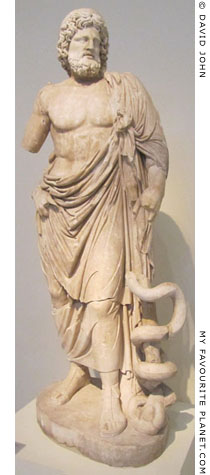

Statue of Asklepios,

Greek god of healing, from

the Sanctuary of Asklepios

at Epidauros, Greece. [2]

Pentelic marble. Roman

period, around 160 AD, copy

of a 4th century BC original.

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. 263. |

| |

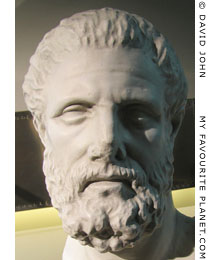

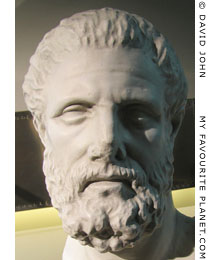

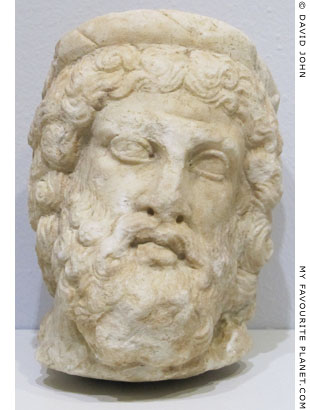

Copy of a marble head of

Hippocrates, from an over

life-size statue. Second half

of the 2nd century BC.

Found near the Odeion on

the island of Kos, Greece.

Replica in the National

Archaeological Museum,

Athens, of the original

in the Archaeological

Museum of Kos. |

| |

| |

A road sign showing the way to the Asklepieion of Pergamon, just outside modern Bergama. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The Via Tecta between Pergamon and the Asklepieion, viewed from just before

the entrance to the Asklepieion at its east side, looking towards Bergama and the

acropolis to the northeast. On each side of the road were colonnaded rows of

shops as well as monumental buildings such as fountains, a baths and a heroon. |

| |

The west side of the Asklepieion from above the theatre.

|

The sanctuary took its present form following a series of renovations, particularly during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD). A large quardrangular courtyard, approximately 130 x 110 metres, bounded on three sides (north, south and west) by stoas (colonnaded walkways). The entrance was on the east side, at the end of the Via Tecta from the city. Along the east side were a number of monumental buildings, including (from north to south) a library, the propylon (entrance gateway), the round temple of Zeus Asklepios and a large treatment centre with a circular core 18 metres in diameter.

Within the quadrangle itself stood the older temple of Asklepios Soter (Saviour) and two smaller temples for Apollo and Hygieia, sleeping rooms (abata) for patients, gardens, fountains and pools built around three sacred springs. These were connected to the treatment centre by the cryptoporticus, a 70 metre long underground vaulted tunnel (see below).

Another long stoa, built during the Hellenistic period, ran westwards from outside the west side of the quardrangle (see below). The Roman period theatre also stood outside the quadrangle, its skene (stage building) stood behind the back wall of the north stoa. |

|

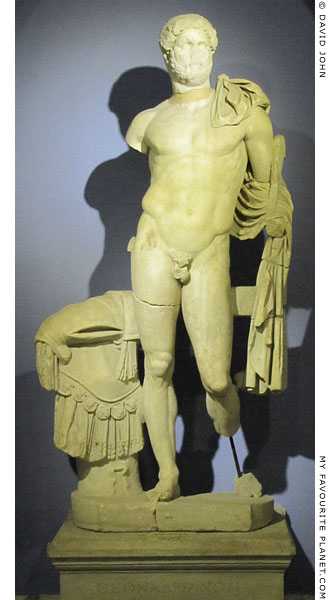

A marble statue of Emperor Hadrian, found

in the library of the Pergamon Asklepieion.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

The 3500 seat Roman theatre at the northwest corner of the Asklepieion, was built on the natural

slope along the south end of the sanctuary. It also served the emperor cult. It was the first theatre

in Anatolia (Asia Minor) to have a three-storey skene (stage building) which has not survived.

Some of the seating has been restored and a modern stage built for summer performances. |

| |

The marble seats of honour in the front of the centre kerkis (κερκίς, wedge-shaped block of

seating) in the theatre cavea (the semi-circular audience seating area). These, the best seats

in the house, were reserved for priests, officials, honoured citizens and visiting dignitaries.

See more about the structure of ancient Greek theatres on Athens Acropolis page 36. |

| |

Reconstructed Doric columns and part of an architrave, all of local red andesite stone

(see gallery 1 page 5), which were part of the long Hellenistic stoa at the west side of

the Pergamon Asklepieion. According to an archaeologist's plan, the building consisted

of a long colonnaded passage along the front and 18 square rooms along the rear. |

| |

The 70 metre long cryptoporticus, an underground vaulted tunnel in the Asklepieion that

connected the circular treatment centre to the pools in the centre of the sanctuary courtyard. |

| |

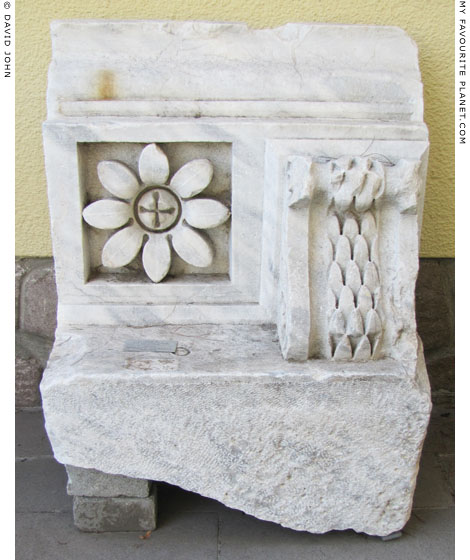

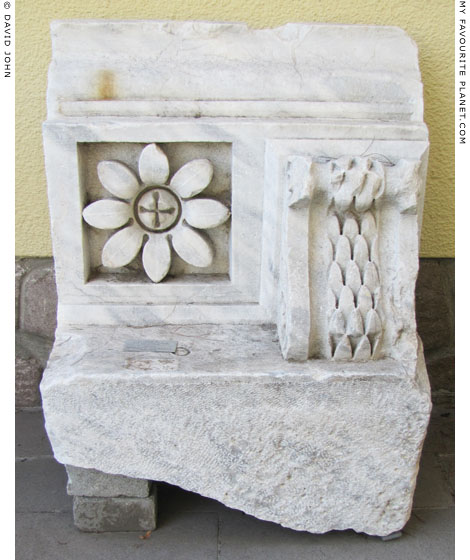

Part of a cornice from the temple of Zeus Asklepios in the Asklepieion.

Roman period, 2nd century AD.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2069. |

| |

Remains of an inscribed marble clipeus (shield) on the broken tympanum of the east pediment

of the north hall of the propylon, the monumental gateway of the Pergamon Asklepieion.

The inscription is a dedication by Aulus Claudius Charax of Pergamon (circa 115 - after

147 AD), who was a priest at the sanctuary and financed the building of the propylon:

ΚΛ[ΑΥΔΙΟΣ] ΧΑΡΑΞ ΤΟ ΠΡ[Ο]ΠΥΛΟ[Ν]

Cl[audius] Charax [dedicated] the pr[o]pylo[n]

In situ at the site of the propylon. Inv. No. 193,7. Inscription IvP III 141. [6]

Height of Tympanum 130 cm, diameter of clipeus 80 cm, letter height 1.75 cm.

The propylon, known as "the Propylon of Claudius Charax",

was built in the mid second century AD, during the reign of

Hadrian (117-138 AD) or Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD),

replacing the Hellenistic buidling of the 3rd century BC.

See also a inscription honouring Aulus Iulius Charax, grandson

or great-grandson of Aulus Claudius Charax, on gallery 1, page 14. |

| |

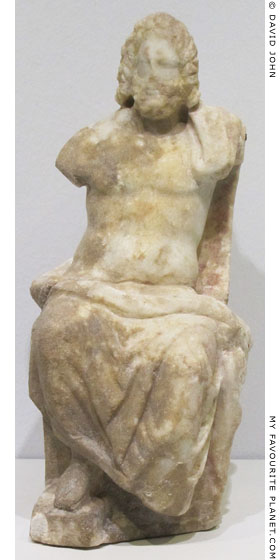

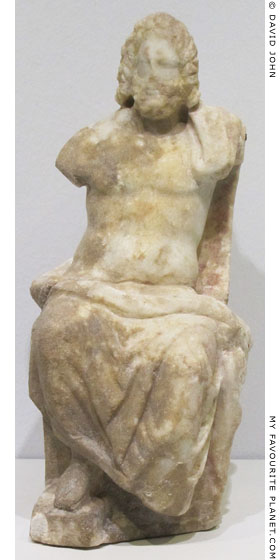

Marble figurine of enthroned Asklepios

from the Pergamon Asklepieion.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

Terracotta votive figurine of

a statue of Asklepios from

the Pergamon Asklepieion.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

Coin from Pergamon showing Asklepios

and Artemis of Ephesus, 253-268 AD.

Inscription: EΠI CEΞ KΛ - CEIΛI/ANO/

V - ΠEPΓ-AMHN-ΩN // KAI EΦECIΩN / OMON.

Minted during the reign of Emperor Gallienus,

253-268 AD, by the Asiarch (magistrate)

Sextus Claudius Silianus. the obverse side

shows a bust of Gallenius, facing right,

wearing a laurel wreath and cuirass, and

the inscription: AVT K Π ΛIKI - ΓAΛΛIHNOC.

Diameter 37 mm, weight 27.26 grams.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. 18200358.

Acquired in 1873 with the entire collection

of General Charles Richard Fox. |

|

| |

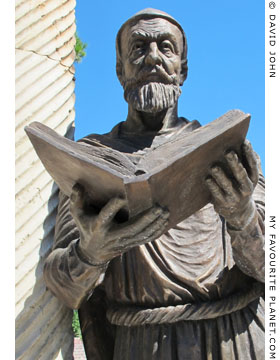

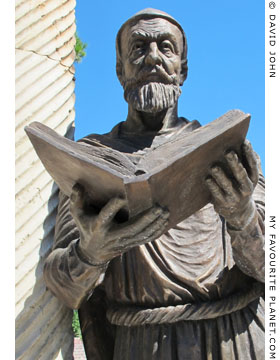

Galen of Pergamon

The famous Greek physician, philosopher and author on medicine, Galen of Pergamon (Γαληνός, Galenos, "calm"; Latin name Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus, 129 - circa 199/217 AD) studied medicine as a θεραπευτής (therapeutes, or attendant) at the Asklepieion for four years, from the age of 16. He then spent 8 years travelling around the cultural centres of the eastern Mediterranean, such as Alexandria in Egypt, which had a renowned medical school.

After widening his horizons and deepening his knowledge, he returned to Pergamon in 157 AD and worked as a doctor, treating the gladiators of the powerful High Priest of Asia. He left for Rome in 162 AD and became an imperial court physician to emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus and Septimius Severus.

Emperor Caracalla (188-217 AD, ruled 198-217 AD, see photo on gallery 1, page 7) may have received treatment here when he visited Pergamon. He made Asklepieion the neokoros, the official centre for the imperial cult of Asklepios and himself for the Roman province of Asia. This was the third of three neokoroi the city was awarded. [3] |

|

Modern statue of Galen

in the centre of Bergama. |

|

| |

An artist's impression of a doctor treating a wounded gladiator in a Roman arena.

Source: L. W. Yaggy and T. L. Haines, Museum of Antiquity: A description of ancient life.

J. B. Furman & Co., Western Publishing House, Chicago, Illinois, 1884. At Project Gutenberg. |

| |

Part of a marble architrave at the side of the Via Tecta near the entrance

to the Asklepieion, with an inscription mentioning Pergamon as neokoros.

Η ΒΟΥΛΗ ΚΑΙ Ο ΔΗΜΟΣ

...Ν ΝΕΩΚΟΡΩΝ ΠΕΡΓΑΜΗΝΩΝ

The stone has been left upside down among a number of other architectural

fragments. This is unfortunate, particularly since this inscription provides

important evidence for the fact that the Asklepieion was the city's third neokoros. |

| |

Telesphoros

Telesphoros (Τελεσφόρος, "the accomplisher" or "bringer of completion"; Latin, Telesphorus), a son of Asklepios was also worshipped at the Asklepieion as the helper in recovery from illness.

In stark contrast to the powerful images of his father Asklepios and his ancient health-conscious sister Hygieia, Telesphoros is always depicted as a small, sad-looking child or dwarf wearing a hooded cape or conical cap and a short tunic. This very un-Greek representation of a deity has led to theories that this late-comer to Hellenic religion was of foreign origin, possibly Thracian, Phrygian or Celtic, and that he was originally one of the hooded spirits (genii cuculati), daemons associated with fertility and death. Images of him are also known on the Danube. His worship may have been introduced to the Greek world by the Galatians when they invaded Anatolia in the 3rd century BC. He became associated with Asklepios by the Greeks of Pergamon and other Asklepios centres in Anatolia (Asia Minor).

The spread of his cult westwards to Greece and the Roman Empire was accelerated following his adoption by Epidauros in the 2nd century AD. [4]

See more photos and information about Telesphoros

on the Asklepios page of the MFP People section. |

|

Ceramic figurine of Telesphoros

wearing a long hooded cloak.

From the Yortanli Dam

salvage excavation, Allianoi,

near Pergamon (see below).

Bergama Archaeological

Museum. |

|

| |

Ancient bronze medical instruments [5] found at the Asklepieion in Allianoi, near Pergamon.

From the Yortanli Dam salvage excavation, Allianoi.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Allianoi (Ἀλλιανοί) is - or rather was - 18 kilometres northeast of Bergama, along the road between Bergama and Ivrindi. The thermal spring is thought to have been founded as a sanctuary of the Asklepios cult and health centre during the Hellenistic period. It was probably a rural sanctuary of the Pergamon kingdom rather than a city, and it appears not to have issued any coins of its own. It was in continuous use from the 3rd century BC until the 11th century AD, and had its heyday during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD) when it was rebuilt on a grand scale. During the Ottoman period it was known as Paşa Ilıcası (Thermal Baths of the Pasha).

No epigraphical evidence has been found at the site to confirm its identity as ancient Allianoi. However, in his book Sacred tales (Ιεροί λόγοι, Hieroi logoi) the orator Aelius Aristides of Mysia (Αἴλιος Ἀριστείδης, 117-181 AD) wrote that he received treatment at the thermal spring, 120 stadia (23-25 km) from Pergamon, and that Asklepios appeared to him there in a dream.

The site had hardly been explored by archaeologists when it was announced in 1994 that the area was to be flooded for as part of a dam project in the valley of the Yortanli stream (Yortanlı Deresi) and the Ilya river (İlya Çayı) on which Allianoi stood. Emergency salvage excavations were undertaken, directed by Dr. Ahmet Yaraş, former director of the Bergama Archaeological Museum, with the support of the Turkish Ministry of Culture, the State Water Administration, the Bergama Yortanli Rescue Society, Trakya University and the German Archaeological Institute (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut). Parts of the extensive site were uncovered from centuries of accumulated silt, although it was estimated that only around 20 per cent of the area had been explored in the time available. The finds, some of which are now exhibited in the Bergama Archaeological Museum, included mosaics, sculptures, ceramics, depictions of Asklepios (see photo right) and Telesphoros (see photo above), coins, metal, bone and glass objects, as well as 348 surgical instruments.

Despite appeals in Turkey and worldwide to save Allianoi by the public, academics, non-government organizations, ICOMOS, UNESCO, Europa Nostra and the European Union, the construction of the Yortanli Dam (Yortanlı Barajı) continued and the site was submerged on 31 December 2010. It now lies at the bottom of the dam reservoir. |

|

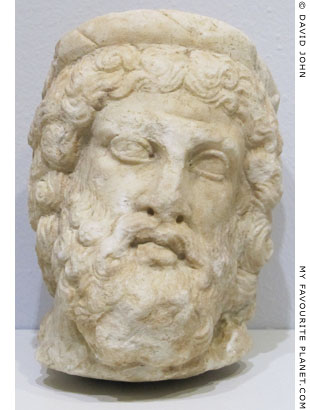

Small marble head of Asklepios from

the Yortanli Dam salvage excavation

at Allianoi, near Pergamon.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

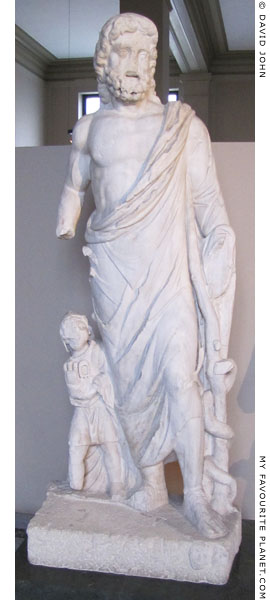

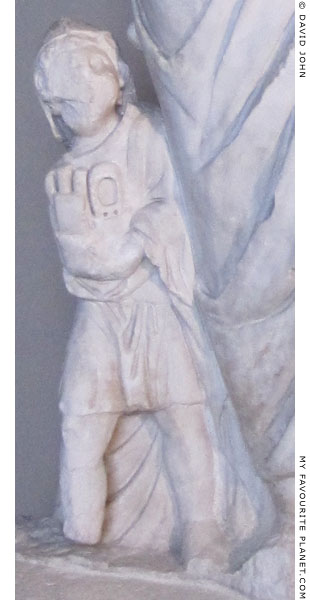

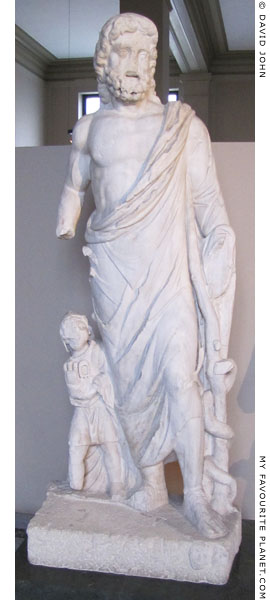

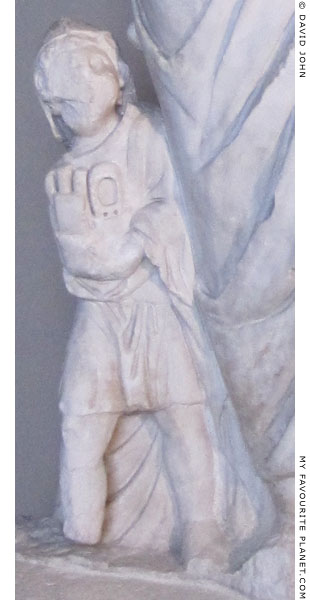

Marble statue of Asklepios and his son Telesphoros.

The detail on the right shows a close-up of the diminuitive daemon.

Excavated in 1906-1907 at the Faustina Baths, Miletus (Balat,

Aydin, Turkey). Height 213 cm; height of Telesphoros 81 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1995.

Cat. Mendel (Volume I, 1912) 124.

The statue depicts the lofty god Asklepios carrying his symbol of a staff (sometimes shown as a crutch), around which a snake is entwined. A relatively tiny Telesphoros is shown leaning against his father's protective garment, looking up to him, and clutching implements which are probably medical instruments. The implication of this image seems to be that Telesphoros was his father's little helper. |

|

| |

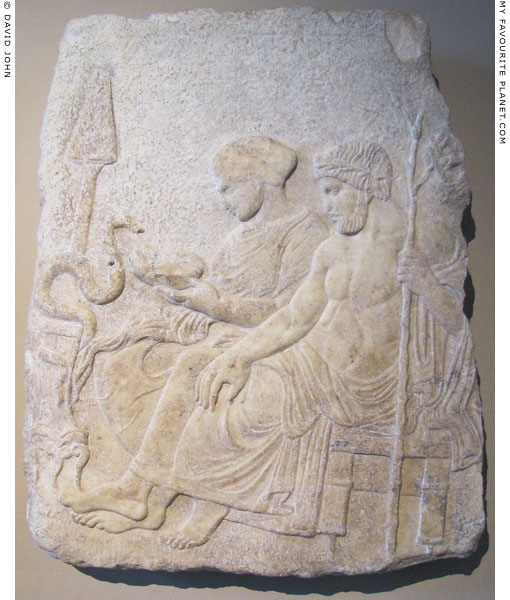

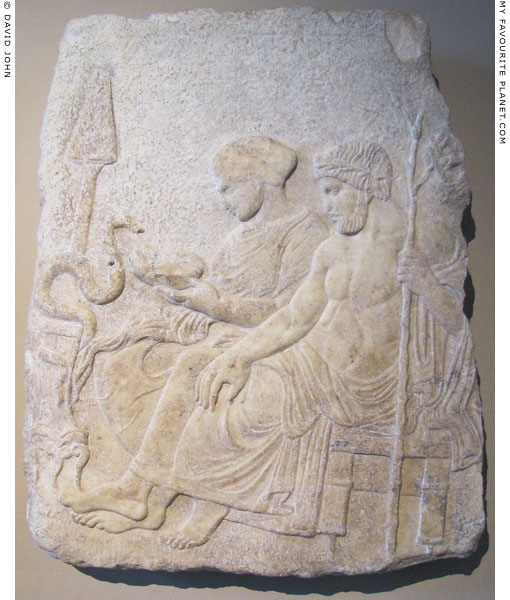

Marble relief showing the healing god Asklepios and his daughter Hygieia,

goddess of health. In some myths Hygieia is the wife of Asklepios.

Classical, last quarter of the 5th century BC. From Therme, Macedonia, Greece.

Therme was the ancient name of Thessalonike (Thessaloniki) before it was

renamed by Cassander, king of Macedonia, in 316/315 BC.

See History of Stageira and Olympiada - Part 6.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 109 T. Cat. Mendel 51. |

| |

Small (mouse-size) cast bronze mouse, sitting on its hind feet and eating a

round object held between its forepaws. Perhaps a votive offering to Asklepios.

Found in the Pergamon Asklepieion in 1932. Helenistic or Roman period.

Antikensammlung, Berlin State Museums (SMB). Inv. No. 31533.

|

Why a mouse? The museum labelling suggests it is perhaps due to the fact that mice were part of the diet of the snakes kept at the sanctuary. Also, because as pests and carriers of diseases, contrary to modern expectations, they may have become associated with the healing god. Mice played an important role in the Anatolian cult of Apollo Smintheus (Ἀπόλλων Σμινθεύς, Apollo the Destroyer of Mice; also referred to as Sminthian Apollo, Σμινθέως Ἀπόλλωνός; mentioned in Homer, Iliad, Book 1, line 38), and the mouse may be a playful allusion to Apollo, the father of Asklepios. Other scholars have suggested that similar Roman figures of mice were used to guard food stores: animal magic.

The Greek geographer Strabo mentioned a statue by Skopas of Apollo Smintheus with a mouse, his symbol or attribute, at Chrysa (Χρῦσα) in the Troad (northwest Anatolia, near modern Göztepe, Turkey). The myth of Smintheus may have been began as a founding myth of the city, but the cult spread through the surrounding area, including nearby islands such as Tenedos (today Bozcaada, Turkey), and as far afield as Pergamon, Lesbos, Keos, Rhodes and Athens.

"The temple of Apollo Smintheus is in this Chrysa, and the symbol, a mouse, which shows the etymology of the epithet Smintheus, lying under the foot of the statue. They are the workmanship of Scopas of Paros."

Strabo, Geography, Book 13, chapter 1, section 48. Translated by H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer. George Bell & Sons, London, 1903. At Perseus Digital Library.

See:

Philip Kiernan, The bronze mice of Apollo Smintheus. American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 118, No. 4 (October 2014), pages 601-626. Archaeological Institute of America. Article at jstor.org.

Jos. Virgil Grohmann, Apollo Smintheus und die Bedeutung der Mäuse in der Mythologie der Indogermanen. Verlag der J. G. Calve'schen K. K. Universitäts-Büchhandlung, Prague, 1862. At the Internet Archive.

The best known surviving mouse in ancient art appears on the "Asarotos Oikos" (Unswept Room) mosaic in the Vatican Museums, which may be a copy of – or have been inspired by – a mosaic from Pergamon by Sosos (see Pergamon gallery 2, page 12).

Another very cute Roman bronze mouse (9.5 cm long), dated circa 2nd - 3rd century AD, was recently extimated by Christie's auction house at 10,000-15,000 US dollars. See: onlineonly.christies.com ... |

|

| |

A marble akroterion (roof decoration) from the Pergamon Asklepieion

with a depiction of winged Nike among plant forms.

Roman period.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Pergamon

Asklepieion |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Archias as founder of the Asklepios cult in Pergamon

This was mentioned by Pausanias (Παυσανίας), the 2nd century AD Greek travel writer, who may himself have been a doctor, and who spent some time in Pergamon.

"There is other evidence that the god was born in Epidaurus for I find that the most famous sanctuaries of Asclepius had their origin from Epidaurus. In the first place, the Athenians, who say that they gave a share of their mystic rites to Asclepius, call this day of the festival Epidauria, and they allege that their worship of Asclepius dates from then. Again, when Archias, son of Aristaechmus [Ἀρχίας ὁ Ἀρισταίχμου], was healed in Epidauria after spraining himself while hunting about Pindasus, he brought the cult to Pergamus.

From the one at Pergamus has been built in our own day the sanctuary of Asclepius by the sea at Smyrna. Further, at Balagrae of the Cyreneans there is an Asclepius called Healer, who like the others came from Epidaurus. From the one at Cyrene was founded the sanctuary of Asclepius at Lebene, in Crete. There is this difference between the Cyreneans and the Epidaurians, that whereas the former sacrifice goats, it is against the custom of the Epidaurians to do so."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 26, sections 8-9. At Perseus Digital Library.

2. Statues of Asklepios

For further information about this statue and other images related to Asklepios, see the Asklepios page of the MFP People section.

3. Pergamon's three neokoroi

The title "neokoros" also referred to the priest of the cult. From the Greek νεωκόρος, meaning temple-keeper or temple warden. Derived from koreo, to sweep, and hence one who sweeps and cleans a temple; temple servant; one who has charge of a temple, to keep and adorn it (a sacristan).

From the time of Augustus, the first Roman emperor, the Greek cities of Asia Minor, such as Pergamon, Smyrna and Ephesus, competed for the honour and prestige of becoming the official centre of the imperial cults for the new Roman province of Asia.

Pergamon's first neokoros, or "provincial temple" was the Temple of Augustus and Roma (see gallery 2, page 6).

The second neokoros at Pergamon was the Temple of Trajan, or Trajaneum, dedicated to Zeus Philios (Latin Jupiter Amicalis), Trajan and Hadrian (see gallery 1, pages 14-19).

4. Pausanias on Telesphoros

Pausanias mentioned Telesphoros in his description of the sanctuary of Asklepios at Titani (Τιτάνη Κορινθίας), in Sikyonia, near Corinth. He tells us that Asklepios' son was known at Titani as Euamerion (Ευαμεριων, prosperous), and at Epidauros as Akesis (Ακεσις, Cure).

"Alexanor, the son of Makhaon, the son of Asklepios, came to Sikyonia and built the sanctuary of Asklepios at Titane... There are images also of Alexanor and of Euamerion; to the former they give offerings as to a hero after the setting of the sun; to Euamerion, as being a god, they give burnt sacrifices. If my conjecture is correct, the Pergamenes, in accordance with an oracle, call this Euamerion Telesphoros, while the Epidaurians call him Akesis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 11, sections 5-7. English Translation by W.H.S. Jones and H.A. Ormerod. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, and William Heinemann Ltd., London, 1918. At Perseus Digital Library.

5. Ancient medical instruments

See: Lawrence J. Bliquez, The tools of Asclepius: Surgical instruments in Greek and Roman times. Brill, Leiden, 2014.

6. The Propylon of Claudius Charax

See: Christian Habicht, Die Inschriften des Asklepieions, Altertümer von Pergamon VIII 3, Nr. 141, Seite (page) 142, with Tafel 40, Abb. 141. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI). De Gruyter, Berlin, 1969. |

| |

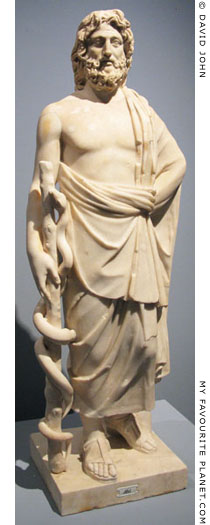

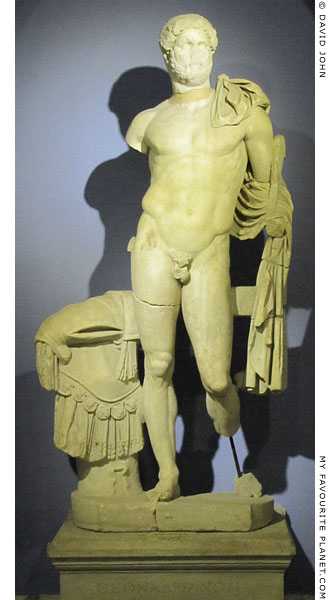

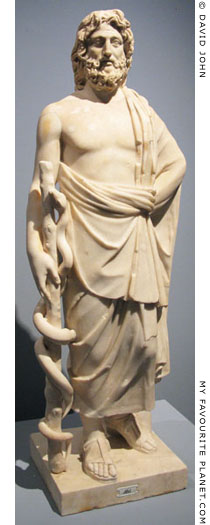

Statue of Asklepios.

From Rome, 2nd century AD.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 71. |

| |

| |

"Wellcome to Asklepion" or "Asklepieion", whichever you prefer. |

Maps, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |