|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Pergamon |

| Pergamon, Turkey |

History of Pergamon |

|

|

page 2 |

|

|

| |

The western side of the Pergamon Acropolis. |

| |

"Pergamon, the most illustrious city in Asia Minor"

Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) [1]

Pergamon, in northwest Anatolia, whose ancient name Pergamos (Greek, Πέργαμον or Πέργαμος; Latin, Pergamum) means "people of the high city", had been inhabited since prehistory, and the name is thought to predate the arrival of the Greeks. However, it really appeared on the map during Hellenistic period (323-146 BC) [2] which began with the conquests of Alexander the Great (see below).

Archaeological finds around Pergamon date back to the Stone Age and Bronze Age, including the time of the Hittites, who at the zenith of their power in the the 14th century BC had conquered most of Anatolia (Asia Minor). After around 1180 BC, as the Hittite empire collapsed, Thracian and Mycenean Greek tribes moved through or settled in the area, though little is known of the early history of Pergamon itself.

At some point this part of Anatolia, which included Troy, became known as Mysia. Ancient writers refer to the area of Mysia around Pergamon in pre-Hellenistic times as Teuthrania, which was possibly also the name of a town, named after the mythical king Teuthras (Τεύθρας).

It is not known whether Teuthras actually existed, and if so whether he was Greek or an indigenous Anatolian. However, according to the complicated mythological geneaologies, he would have lived before the time of the Trojan War, and his grandson and successor Eurypylos (Εὐρύπυλος), son of Telephos (Τήλεφος, far-shining), fought against the invading Greeks on the side of Troy at the head of the Ceteians (of the river Ketios, today the Kestel Çayı, which runs through Bergama; see gallery 1, page 25), even if he did have to be bribed by his mother to do so. [3]

Telephos, the son of Herakles and Auge (Αὔγη), was a prince of Tegea in the Peloponnese, and Teuthras is said to have given him and his mother refuge, offered him his daughter in marriage and made him his heir. This all sounds like either a Greek non-hostile take-over or assimilation into an Anatolian society. In most other places in Anatolia, such as Ephesus, the Greeks simply killed, enslaved and drove off the local inhabitants and stole their land.

The heroic tales concerning Telephos and Auge became part of the foundation myths of the Pergamon kingdom, and were graphically depicted on the reliefs on the inner court walls of the Great Altar of Zeus on the Pergamon Acropolis (now in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin; see gallery 2, pages 23-26). This complicated yarn has all the ingredients of epic myth: love, sex, lost children, betrayal, battles, shipwrecks, rescues, prophecies and divine interventions. It is suprising it hasn't been made into a movie.

The much-embroidered story was used by Pergamon's Hellenistic Attalid rulers (4th - 2nd centuries BC, see below) as legitimizing propaganda, weaving in elements of mortal heroism, the ancient Greek gods and ancestor worship. The Attalids claimed to be descendants of Telephos, despite the fact that their founder came from the Black Sea coast. The narrative also ties Pergamon to other places revered in classical times such as Arcadia, Delphi and Troy.

Another foundation myth was retold by the Greek travel writer and historian Pausanias (2nd century AD), who spent some time in Pergamon. Pergamos, son of the Homeric Pyrrhos, son of Achilles, and Andromache, widow of Prince Hector of Troy, crossed from Epiros in northwestern Greece to Asia, killed King Areios of Teuthrania in single combat, took the throne and renamed the city after himself. His mother Andromache went with him, and Pausanias tells us that her shrine there still existed in his day. [4]

|

Pergamon Acropolis |

photo gallery 1

Photos and information

about Pergamon's sights.

photo gallery 2

Photos and information

about art and architectural

objects, from or related

to Pergamon, in various museums. |

Marble female idol

of the Kiliya type,

from Babaköy,

northwest Anatolia.

Circa 4200-3000 BC,

Chalcolithic Period.

Height 9.9 cm.

Antikensammlung SMB,

Berlin. Inv. No. 31457.

Acquired in 1933 by

Theodor Wiegand. |

| |

Archaic "wild goat style" pottery from Gryneion (Yenişakran) near

Pergamon.

7th - 5th century BC.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

| |

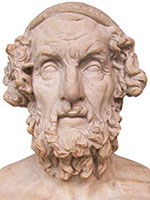

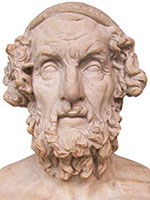

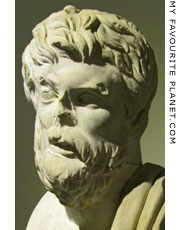

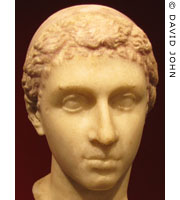

Homer, the first writer

to mention the area

of Pergamon.

See gallery 2, page 1.

Marble bust,

British Museum, London. |

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

1000 BC: Greek settlers |

|

|

|

Aeolian Greeks from Thessaly and Boeotia settled here around 1000 BC when they were driven from mainland Greece by invading Dorians, and the coastal region in which they settled also became known as Aeolia (Αἰολία, Aiolia, or Αἰολίς, Aiolis), just as the area taken over by Ionian Greeks further south along the Aegean coast (for example Ephesus) became known as Ionia.

In contrast to the sea-going Ionians, their new neighbours in Asia, the Aeolians were landlubbers and farmers. The Greek historian Herodotus (circa 485-425 BC), who was born in Halicarnassos (today the Turkish city of Bodrum) in Caria, wrote that "the soil of Aeolia is better than that of Ionia, but the climate is not so good." [5]

Mysia was overtaken by the neighbouring kingdom of Phrygia (to the east) and then by Lydia (to the south). |

Lydian gold stater,

Sardis, 610-560 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

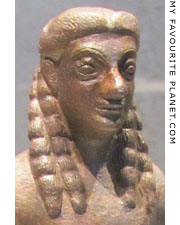

Detail of an Archaic

Greek kouros statuette.

Bronze, 570-560 BC.

From the Sanctuary of

Hera, Samos, Greece.

Neues Museum, Berlin. |

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

546-334 BC: The Persians |

|

|

|

In 546 BC the Lydian King Croesos was defeated by King Cyrus the Great (559-529 BC), and the Greek cities of Anatolia became part of the Persian empire, governed on behalf of the king by a series of local rulers known as satraps.

For the next 200 years the Greeks and Persians were to be arch enemies, with wars on an enormous scale and unsuccessful revolts by conquered Greek cities, and for a while it seemed that the Greek culture and way of life was doomed. This situation was made worse by the age-old prediliction of the Greek states for fighting among themselves, particularly Athens, Thebes and Sparta. Various Greek states and generals also allied themselves with Persia either to damage competing Greek states, or because they were bribed or compelled to by the Persian kings.

But the Persian empire also had its weaknesses and internecine struggles. The Greeks were not above using Persia's problems to their own advantage, even supplying mercenaries to one side or the other.

Archaeologists have found artefacts at Pergamon which they believe prove that there was a small settlement here during the 6th - 5th centuries BC, although not much more has yet been discovered about life here during this period.

The earliest known historical mention of Pergamon was by the general, historian and pupil of Socrates, Xenophon of Athens (circa 430-354 BC) who arrived with his army in 399 BC. In his memoir Anabasis (The march up country), he recounts how he led "the ten thousand" Greek soldiers out of south eastern Anatolia after a disastrous military expedition to support Cyrus the Younger, satrap of Asia Minor, against his brother, emperor Artaxerxes II of Persia (401 BC).

He concludes the work with an odd sort of "happy end" by telling of another military adventure. He and his soldiers travel through Mysia (northwestern Anatolia) on their way to yet another war. Xenophon is, as ever, short of money. In Pergamon he is "hospitably entertained" by Hellas, the widow of the city's administrator Gongylos the Eretrian. She tells him about Asidates, a rich Persian who lives in a tower nearby on the plain of the Kaikos River, and suggests that he should rob and capture him, "wife, children, money, and all; of money he has a store". This Xenophon does, and his troops unanimously vote to give him the first pick of the loot. [6]

He makes no attempt to justify this opportunistic robbery or explain his or Hellas' motives for it. Perhaps it was clear to his Greek readership that the Persians were the enemy and therefore fair game. |

Persian gold daric coin,

5th - 4th century BC.

Numismatic Collection,

Bode Museum, Berlin.

See: Big Money

at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

| |

Xenophon of Athens.

Marble bust from the

Asklepieion, Pergamon.

Roman Imperial period,

2nd century AD. [7]

Bergama Museum.

Inv. No. 784. |

| |

Detail of a Greco-Persian

grave stele from Magnesia

ad Sypilum (Manisa).

Bergama Museum. |

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

334-281 BC: Alexander the Great

and his successors |

|

|

|

Alexander the Great is said to have studied Xenophon's Anabasis as a field guide to Anatolia before embarking on his campaign against the Persian king Darius III. In 334 BC Alexander defeated Darius on the River Granicus (near modern Çanakkale). As he marched through western Anatolia, Pergamon surrendered to him, and he appointed Barsine, the widow of the Persian commander, as administrator.

After Alexander the Great's sudden death in Babylon in 323 BC, his generals and relations (Διάδοχοι, the Diadochi, successors) waged war on each other for control of parts of his empire. Eventually, in 301 BC Lysimachus (Λυσίμαχος, Lysimachos, circa 360-281 BC), king of Thrace [8], took control of western Anatolia (Lydia, Ionia and Phrygia), including Pergamon. With the great riches he had accumulated as the spoils of war, he began rebuilding ancient cities such as Ephesus, and several new cities appeared in Anatolia.

Lysimachus stored his war booty, a fortune of 9,000 talents of silver [9], estimated to be worth 54 million drachmas, at Pergamon, choosing as treasurer (gazophylax) one of his officers, Philetaerus (Φιλέταιρος, Philetairos, circa 343-263 BC) of Tios (Τίειον) [10], a colony of Miletus on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia. Philetaerus is said to have been a eunuch, whose father Attalus (Ἄτταλος, Attalos) was Greek, perhaps from Macedon, and mother Boa (Βόα), a Paphlagonian concubine and musician. He had previously served Antigonus, one of Lysimachus' enemies, but had switched sides. He was to do this again as later the wars of the Diadochi became ever more complex and murderous.

Lysimachus had made himself very unpopular with the people of western Anatolia, especially after he had his own son Agothocles executed, and his days were numbered. Philetaerus offered the fortress of Pergamon and its treasury to Seleucus (circa 358-281 BC, later known as Σέλευκος Α΄ Νικάτωρ, Seleukos I Nikator, the Victor), ruler of much of Alexander's empire in Asia and founder of the Seleucid dynasty (often referred to as the Syrian kings), who defeated and killed Lysimachus at the Battle of Corupedium in 281 BC.

After his victory, Seleucus was naturally keen to claim the promised riches of Pergamon in order to finance the expansion of his empire into Europe. The cunning Philetaerus was able to keep deferring the payoff, and luckily for him Seleucus was murdered soon after by one of his own protegés, Ptolemy Keraunos [11]. |

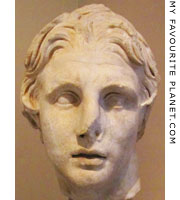

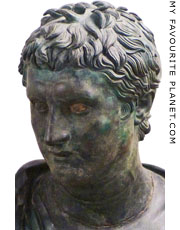

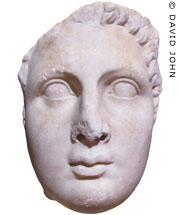

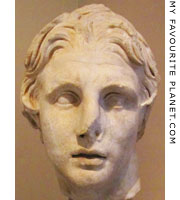

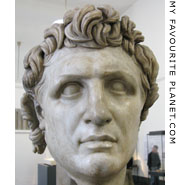

Marble head of Alexander

the Great from Pergamon.

2nd century BC.

Istanbul Archaeological

Museum.

See gallery 2, page 2. |

| |

Alexander's portrait on a

silver tetradrachm coin of

Lysimachus. From Ainos,

Thrace, circa 297-281 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

See gallery 2, page 3. |

| |

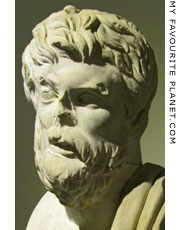

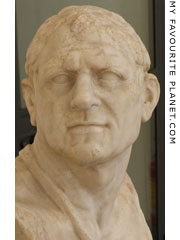

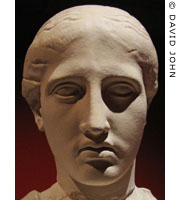

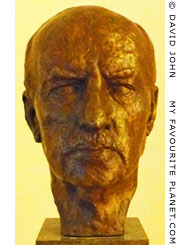

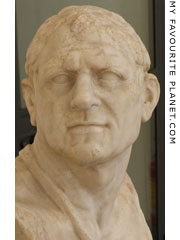

Marble bust thought to be

a portrait of Lysimachus.

Augustan copy (23 BC -

14 AD) of a 2nd century

BC Greek original.

National Archaeological

Museum, Naples.

See gallery 2, page 3. |

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

281 BC: The Attalid dynasty

and the Gauls |

|

|

|

Although Pergamon was now part of the Seleucid empire it was left largely autonomous. Philetaerus was able to hold onto Pergamon's wealth and use it to increase his power and influence and found the Attalid dynasty, named after his father Attalos, which was to rule Pergamon until 133 BC. All the Attalid rulers, except Eumenes II, depicted his head on their coins in honour of the dynastic founder.

On the Pergamon Acropolis Philetaerus built the temple of Demeter, the temple of Athena (the city's patron goddess) and the first palace, and improved the city's fortifications. He donated funds to other cities and religious centres, including Delphi and Delos, thus strengthening diplomatic ties.

He also contributed troops, money and provisions to fight the Gauls, Celtic tribes who had invaded the Balkans and Anatolia, and in 278 BC settled in the area of central Anatolia which was to become known as Galatia (Γαλατία). The Gauls continually raided Greek settlements and were deemed invincible. They began demanding tributes, i.e. protection money, which the Greek cities were forced to pay. [12]

|

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

263-241 BC: Eumenes I |

|

|

|

Philetaerus was succeeded by Eumenes I (Ευμένης Α' της Περγάμου, died 241 BC), his nephew and adopted son, who revolted against the Seleucid king Antiochus I and defeated him near Sardis in 261 BC. He extended the land under the control of the newly independent Pergamon, and managed to maintain peace with the Seleucids and the Gauls who were still plaguing Anatolia. Eumenes also continued the building work on the Pergamon Acropolis begun by his uncle and encouraged the arts, philosophy and sports.

Like his uncle Philetaerus, Eumenes I died childless and was succeeded by his second cousin and adopted son Attalus. |

|

Silver tetradrachm coin of

Eumenes I, with a portrait

of Philetaerus. 262-241 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

See gallery 2, page 3. |

|

| |

History of

Pergamon |

241-197 BC: Attalus I Soter |

|

|

|

Attalus I (Ἄτταλος Αʹ, 269-197 BC) became known as Soter (Σωτὴρ, Saviour) and was the first Attalid to take the title king (238 BC). One of his first decrees banned the payment of tributes to the Galatians, the Celtic warriors who had settled in central Anatolia. They attacked Pergamon, causing severe losses to the Attalus' forces. However, the next year he managed to turn the tide against them and their Seleucid allies, and by 227 BC he had totally destroyed the Gallic threat.

His victories made him a popular hero throughout the Greek world, and he set up victory monuments consisting of bronze statues and statue groups at several places, including Delos, Delphi, the Sanctuary of Athena Nikephoros on Pergamon's Acropolis and next to the Parthenon on the Athens Acropolis (see below).

"The greatest of his [Attalus] achievements was his forcing the Gauls to retire from the sea into the country which they still hold."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias reported that the Delphians claimed that their oracle had prophesied the invasion of the Galatians and their defeat by Attalus.

"The Aetolians have statues of most of their generals, and images of Artemis, Athena and two of Apollo, dedicated after their conclusion of the war against the Gauls. That the Celtic army would cross from Europe to Asia to destroy the cities there was prophesied by Phaennis in her oracles a generation before the invasion occurred:

'Then verily, having crossed the narrow strait of the Hellespont,

The devastating host of the Gauls shall pipe; and lawlessly

They shall ravage Asia; and much worse shall God do

To those who dwell by the shores of the sea

For a short while. For right soon the son of Cronos

Shall raise them a helper, the dear son of a bull reared by Zeus,

Who on all the Gauls shall bring a day of destruction.'

By 'the son of a bull' she meant Attalus, king of Pergamus, who was also styled bull-horned by an oracle."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 15, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Attalus also began the building of the Pergamon Library, which was to became the second most important in the ancient world after the Library of Alexandria in Egypt. (There were actually two libraries at Alexandria, but that's another story). The building of the library was continued in grand style by his son Eumenes II (see below).

In Asia he had several victories and setbacks as he attempted to seize territory from the Seleucids, and he eventually turned his attentions westwards to Greece.

Significantly, he also allied himself with Rome which meanwhile had become the dominant power in the Mediterranean and was rapidly taking over Greek territories in Europe. At the time, many Greek states, including Athens, welcomed the interventions by Attalus and the Romans against Philip V of Macedon (Φίλιππος Ε΄, 238-179 BC, king of Macedon 221-179 BC) in the first and second Macedonian Wars. During these wars Attalus gained the Aegean islands of Andros, Euboea and Aegina [13] (see photo, below right) which he made his base of operations.

In 201 BC Philip V invaded Pergamon, but due to Attalus' improved fortifications he was unable to take the city and had to satisfy himself by destroying temples and altars outside the walls.

In 200 BC Attalus was given a hero's welcome in Athens, and an Athenian tribe was named Attalis in his honour. Pergamon had arrived as a power to be reckoned with in the Aegean, and Attalus had further enriched the city with the booty he had taken from defeated enemies.

The period of his reign was marked by wars throughout Asia and the Mediterranean, including Rome's war against Hannibal of Carthage. The stakes were very high, as the losers were either slaughtered or enslaved and the winners gained power, territory, slaves and riches; mercy was in very short supply.

Attalus, as one of the winners, was able to live to the ripe old age of 72 and leave a stable family and kingdom to his four sons. In 197 BC, during the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BC), he collapsed from a stroke while giving a speech to a Boeotian council in Thebes. Partly paralyzed, he was taken home to Pergamon where he died in the same year, either before or shortly after the Battle of Cynoscephalae, in which Philip V was defeated, bringing about the end of the war. [14] |

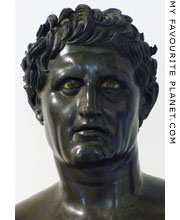

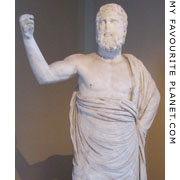

Attalus I.

Marble head from the

Pergamon Acropolis.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

See gallery 2, page 4. |

| |

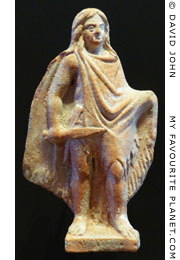

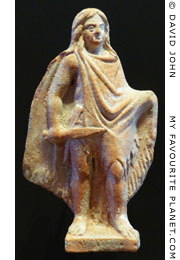

Ceramic figure of a Celtic

warrior from Myrina,

Mysia. 2nd century BC.

Height 14.2 cm.

Antikensammlung SMB,

Berlin. Inv. No. 30026.

Purchased 1910 in Izmir. |

| |

Inscribed limestone altar

dedicated to Zeus and

Athena on behalf of

Attalus I by officers and

men of the Pergamene

garrison on Aegina.

2nd century BC. [15]

Attalus I purchased the

island from the Aetolian

League for 30 talents in

210 BC [see note 13],

and soldiers of the

garrison settled there.

It remained Pergamene

property until 133 BC,

when, along with the rest

of Pergamon's territory,

it was inherited from

Attalus III by the Roman

Republic (see below).

Aegina Archaeological

Museum. Inv. No. 1331. |

| |

| |

The "the Dying Gaul" or "Capitoline Gaul" ("Galata Capitolino"), a marble statue of a dying

Gaulish warrior. Thought to be a copy of one of the bronze statues commissioned by

Attalus I to commemorate his victories over the Galatians around 238-227 BC. [16]

The monument was set up around 226-220 BC on the Pergamon Acropolis and

dedicated to Athena (see gallery 2, pages 20-22). The "Ludovisi Gaul" (see below)

may also have been part of the monument.

Found about 1622 in the area of the Villa Ludovisi, on the Quirinal Hill, Rome, the location of the

ancient Horti Sallustiani (Gardens of Sallust), previously the Horti Cesari (Gardens of Caesar).

It has been suggested that the "Capitoline Gaul" and the "Ludovisi Gaul" may have been

commissioned by Julius Caesar as symbolic copies following his victories in Gaul. Moved from

the Villa Ludovisi to the Capitoline during the papacy of Clement XII (1730-1740). Height 93 cm.

Sala del Galata (Hall of the Gaul), Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums,

Rome. Inv. No. MC 747. From the Ludovisi Collection. |

| |

The "Ludovisi Gaul", a marble statue group of a Gaul, perhaps a chieftain,

killing himself and his wife rather than surrender to their enemies.

Found around the same time as the "Capitoline Gaul" (see above), probably

in the area of the Villa Ludovisi, on the Quirinal Hill, Rome. Docimenum marble.

Carrara marble used for restorations. Height 211 cm.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 8608.

From the Boncompagni Ludovisi Collection. |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

197-159 BC: Eumenes II |

|

|

|

Attalus' eldest son and successor Eumenes II (Εὐμένης Β' τῆς Περγάμου, ruled 197-159 BC) continued his father's policies, and was probably advised by his mother Apollonis (Ἀπoλλωνίς). As an ally of Rome he continued to oppose Macedonia and the Seleucids under Antiochus III the Great.

With the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Scipio he defeated Antiochus at the Battle of Magnesia, near Magnesia ad Sipylum (today Manisa, Turkey) in 190 BC, and gained the regions of Phrygia, Lydia, Pisidia, Pamphylia and parts of Lycia with the blessing of the Romans.

Eumenes fostered the Attalids' good relations with Greece, particularly Athens, where a colossal statue of him and his brother Attalus (later Attalus II, see below) commemorated their victory in a chariot race during the Panathenaic Games in 178 BC, one of a number they won there (see Athens Acropolis page 8). Eumenes built the Stoa of Eumenes beneath the north side of the Athens Acropolis, between the Theatre of Dionysos and the site later occupied by the Odeion of Herodes Atticus.

As part of his plans for the Pergamon Acropolis, Eumenes built the Altar of Zeus and undertook extensive renovations of the theatre. An avid collector of books, he also expanded the Pergamon Library, which gave rise to the legend that parchment (also known as pergament and charta pergamena, made from animal skins) was invented here.

According the Roman historian Varro (quoted by another Roman author Pliny the Elder), the Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes (ruled 203-181 BC) was so envious of Pergamon's growing library, which was competing with his own at Alexandria, that he banned the export of papyrus. Necessity being the mother of invention, the Pergamese are said to have devised parchment to meet their needs [17]. Writing on skins was known long before Eumenes' time, indeeed Herodotus (circa 485-425 BC) mentions it as an ancient practice [18], but it is probable that the production of parchment was refined at Pergamon which must also have manufactured a considerable amount for writing and copying manuscripts for the library.

Since parchment could not be rolled up like papyrus, the development of sheets of treated skins sewn together as a codex led to the form of modern books.

Plutarch wrote that in the 1st century BC, Mark Antony (83-30 BC) was accused by Calvisius, one of his enemies in Rome, of taking the Pergamon library's 200,000 volumes as a gift for Cleopatra. [19]

The Romans later suspected Eumenes of plotting with Perseus of Macedon, and in 167 BC offered to assist his younger brother Attalus (the second son of Attalus I and Apollonis, to become Attalus II) to overthrow him, but Attalus refused. In Eumenes' last years he apparently suffered ill health, and Attalus co-ruled with him from 160 BC. |

| |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

159-138 BC: Attalus II Philadelphus |

|

|

|

When Eumenes II died in 158 BC, his son Attalus (later Attalus III, see below) was only around 12 years old and too young to rule, and so Eumenes' brother Attalus II Philadelphus (Ἄτταλος Β' ὁ Φιλάδελφος, Attalos B Philadelphos, Attalus the brother-loving, 220-138 BC) continued his regency. He also married Eumenes' widow Stratonike (Στρατονίκη, circa 200 - circa 138-135 BC), daughter of King Ariarathes IV of Cappadocia, who was a good friend and ally of Attalus.

Attalus had already proved himself an able military commander and diplomat, having made several diplomatic visits to Rome and seen off attacks by the Seleucids (190 and 182 BC) and Pharnaces I of Pontus (182 BC). He had also fought alongside the Romans in Galatia (189 BC) and Greece (171 BC, during the Third Macedonian War).

With the support of the Romans he helped the pretender Alexander Balas depose the Seleucid king Demetrius I in 150 BC, and Nicomedes II Epiphanes to overthrow his father, the Bithynian king Prusias II in 149 BC. He thus sought to make allies of two of Pergamon's strongest local enemies.

King Ariarathes IV of Cappadocia helped Attalus expand his territories and found the cities of Philadelphia and Attalia (the modern Turkish city of Antalya). By this time Pergamon had become the largest and most powerful kingdom in Anatolia.

Like his predecessors, Attalus encouraged the arts in Pergamon and abroad. He also financed the building of the Stoa of Attalus in the Athens Agora, which has now been restored and today is one of the gems of the ancient market place, housing the Agora Museum. |

| |

| |

A marble statue of a seated lion with a bovine head between its forepaws.

Hellenistic period. From Pergamon; found in Hamzali village, Bergama.

Exhibited in the courtyard of Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

138-133 BC: Attalus III,

the last Attalid king |

|

|

|

138-133 BC: Attalus III, the last Attalid king

Attalus III Philometor Euergetes (Άτταλος Γ' ο Φιλομήτωρ, Attalos Mother-Loving Benefactor, circa 170-133 BC) preferred studying medicine and botany to kingship, and having no male heir he decided to bequeath Pergamon and its extensive territories to the Roman Republic, presumably to prevent the kind of destructive wars of succession which had been tearing the Greek world apart since the death of Alexander the Great.

In Rome, the populist politician Tiberius Gracchus (162-133 BC) planned to use the inherited wealth of Pergamon to finance his radical land reforms, and even proposed selling off its artworks to raise capital. However these plans were thwarted by the rich and powerful noble families who controlled the Senate. Eventually they turned the Romans against Tiberius and murdered him and his followers.

See an inscription from the Sanctuary of Athena Nikephoros

with letters of Attalus II and Attalus III concerning priesthoods

in Pergamon on Pergamon gallery 1, page 20. |

|

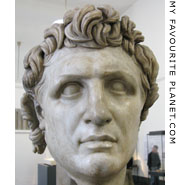

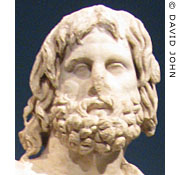

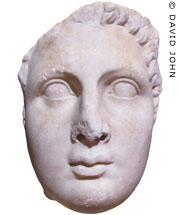

Marble head thought to be

a portrait of Attalus III of Pergamon. Circa 150 BC.

From the Dionysos Temple

at the Pergamon Theatre.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. AvP VII 132. |

|

| |

History of

Pergamon |

133-129 BC: the pretender Eumenes III |

|

|

|

Many of Pergamon's subjects were opposed to rule by Rome, which was slow to seize control, causing a power vacuum.

The pretender Aristonicus (Αριστόνικος, Aristonikos) claimed to be the illegitimate son of Eumenes II and took the throne of Pergamon as Eumenes III. He offered the Greek cities freedom in his new state of Heliopolis (Sun City), and even promised to free all slaves. However he received limited support.

At first he successfully fought off the Romans, and in 133 BC defeated Consul Publius Licinius Crassus Dives Mucianus, who died during the battle. In 129 BC he was defeated by Marcus Perperna, who took him as a captive to Rome where he was paraded through the streets and executed by strangulation. |

|

|

|

| |

History of

Pergamon |

From 129 BC: the Romans |

|

|

|

A silver tetradrachm coin of King Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus (Μιθραδάτης Στ' Ευπάτωρ;

135-63 BC, reigned 121-63 BC), minted in Pergamon, which he captured during the First

Mithridatic War, 89-85 BC, and where he is said to have resided until the end of the war.

This coin is dated ΓKΣ = 223 BE (74 BC), during the Third Mithridatic War (75-63 BC). [20]

On the obverse side (left) is a portrait head of Mithradates VI in profile, facing right.

On the reverse side is a stag (perhaps as a symbol of Artemis) grazing, the inscription

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΙΘΡΑΔΑΤΟΥ ΕΥΠΑΤΟΡΟΣ (of King Mithradates Eupator), as well as a star

above a crescent and a monogram of Pergamon; the entire design is surrounded by

a Dionysiac wreath of ivy leaves and berries. |

| |

Following the defeat of Aristonicus, Pergamon's vast territories were divided among the Roman Republic, Pontus and Cappadocia. The cities under Roman control, at first styled "the free cities of Asia", became part of the new province of Asia with Pergamon as its capital.

Roman rule became increasingly unpopular in Anatolia, particularly due to the increased taxation and other restrictions on freedom, as well as the growing dominance of Roman representatives and Italic (Italian) businessmen. Capitalizing on this, in 88 BC Mithridates VI of Pontus was able to conquer much of the province and instigate a revolt against Rome, during which as many as 80,000-150,000 Italics were massacred.

In 86-85 BC Mithridates' political aims were thwarted by the Roman general (later dictator) Lucius Cornelius Sulla who forced him to accept a peace agreement and withdraw from the lands he had captured. He also consolidated Roman rule and reorganized the province. As part of the punishments Sulla imposed on Pergamon and the other Asian cities for supporting Mithridates, they were forced to pay the back-taxes due from the years of the revolt, causing considerable debt, impoverishment and financial stagnation in the region.

Pergamon gradually recovered financially and culturally. Although Augustus (Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus, 63 BC - 14 AD, reigned 27 BC - 14 AD), the first Roman Emperor, moved the capital of the province of Asia from Pergamon to Ephesus, he doubled the size of the city by building a new district, based on a grid system, below the Acropolis, on the banks of the Selinus river.

Several prestigious building projects were undertaken during the reigns of successive emperors, including a theatre, ampitheatre and stadium and the enormous temple now known as "the Red Basilica" in the lower city; the Trajaneum and several enhancements to the institutions of the Acropolis and extensions to the Asklepion healing centre. The water supply system was also improved by the building of an aqueduct.

The city was made the Neokoros, the official centre of the Imperial cult, for the province of Asia three times (see Pergamon gallery 1, page 6). |

|

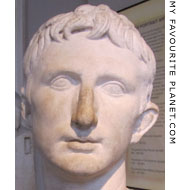

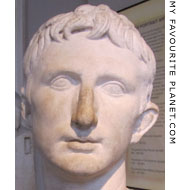

Emperor Augustus

(reigned 27 BC-14 AD).

Marble bust from the

Sanctuary of Demeter, Pergamon. Probably

made during the lifetime

of Augustus.

Istanbul Archaeological

Museum.

See gallery 2, page 6. |

|

| |

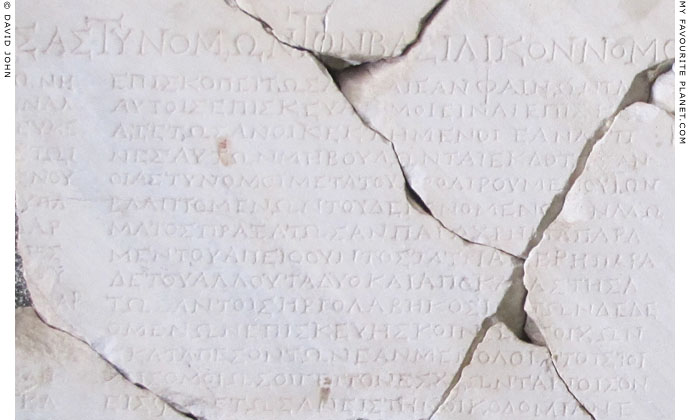

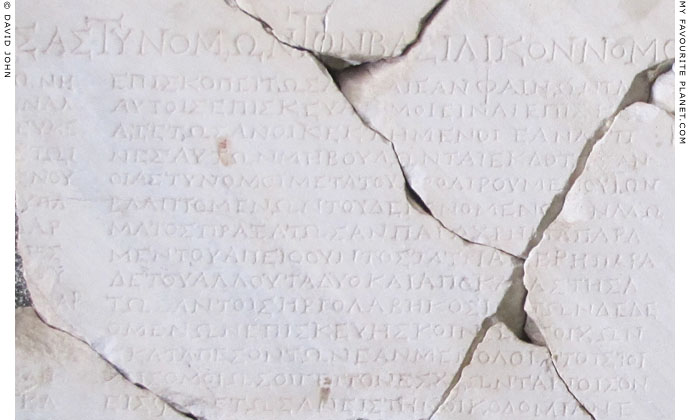

Detail of a limestone slab inscribed with the Astynomoi Law of Pergamon.

From the Lower Agora of the Pergamon Acropolis. Roman period. [21]

Bergama Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2006. |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

Early Christianity |

|

|

|

Pergamon was one of the seven churches of Asia addressed in the Book of Revelation, written by Saint John of Patmos (see our pages on Patmos, Greece). John referred to Pergamon as "the seat of Satan" (Revelation 2: 12-13).

According to tradition, Antipas, the first bishop of Pergamon, was martyred here around 92 AD.

The decline of the Roman Empire led to many of its great cities becoming gradually abandoned, and at some unknown date Pergamon too was deserted. Later a new settlement grew in the valley of the Bergama Çayı (the ancient Selinus river) below the western slope of the acropolis hill, which was used as a fortress. Under the Ottoman Turks the settlement became known as Bergama, which by the late 19th century was described as a city with a mixed population of around 20,000 Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Jews. |

Byzantine marble gargoyle

water spout from the

Lower Agora, Pergamon.

Bergama Museum. |

| |

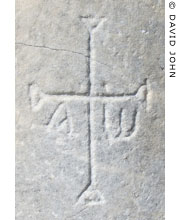

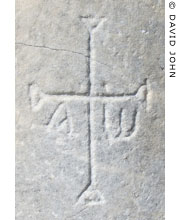

Grafitti, with Christian

symbols of the crucifix

and Aplha Omega, on

a marble column along

the Via Tecta between

Pergamon and the city's

Asklepieion. |

| |

| |

A fragment of a Byzantine mosaic from Pergamon

with a depiction of a dolphin. 5th - 6th century AD.

Izmir Museum of History and Art. |

| |

History of

Pergamon |

Rediscovery and archaeology |

|

|

|

"The acropolis of Pergamus", 1882, by English architect and landscape artist Thomas Allom [22].

A romanticized view of Pergamon, with a caravan crossing the Bakır Çayı river on the Roman bridge,

and the peaks of Madra Daği, here greatly exaggerated, soaring up behind the Pergamon Acropolis.

(Compare with the photo on gallery 1, page 3). |

| |

| Section in preparation |

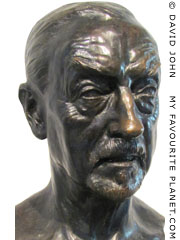

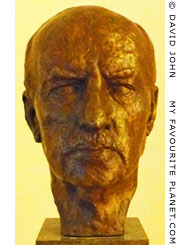

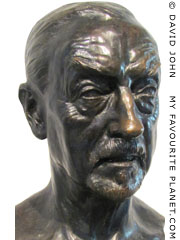

Bust of Carl Humann

by Adolf Brütt [23]

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. |

| |

Bust of Theodor Wiegand

by Carl Blümel.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. |

| |

Bust of Alexander Conze

by Fritz Klimsch [24].

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

| We are currently working to extend this history of Pergamon. |

Panoramic view from the west side of the Pergamon Acropolis. |

| |

|

|

|

|

History of

Pergamon |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Pliny on Pergamon

"... longeque clarissimum Asiae Pergamum"

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 5, chapter 33. At Perseus Digital Library.

In Latin: The Natural History, Liber V, xxxiii. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

2. The Hellenistic Age began with the conquests of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). During this era Greek culture was spread widely but was also influenced by the art, science and ideas from the known world. It ended during the 2nd - 1st centuries BC, following the Roman take-over of what had been Alexander's empire (i.e. Greece and parts of the Balkans, Asia and north Africa), as well as Greek colonies around the Mediterranean and Black Sea. However, Roman culture continued to be influenced by Greek architecture, science, art, literature, philosophy and religion. Several prominent Romans, particularly emperors such as Hadrian, were keen to have themselves associated with this Greek cultural heritage.

3. Teuthrania in Homer's Odyssey

See the article about Homer's reference to Telephos, Eurypylos and the Ceteians on gallery 2, page 1.

4. Pausanias (Παυσανίας), 2nd century AD Greek travel writer, thought to be from Lydia in Asia Minor. His only known book is Description of Greece (Ἑλλάδος περιήγησις). Although Book 1 (of 10) is a guide to Athens and Attica, but also contains information about other places, including summaries of phases of Pergamon's history.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, Chapter 11, Section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

5. Herodotus (Ἡρόδοτος, circa 484-425 BC), "the Father of History", Greek historian born in Halicarnassus, Caria (today Bodrum, Turkey).

Herodotus, The Histories, Volume I, Book I, 149. English translation by George Campbell Macaulay (1852-1915). Published in two volumes by MacMillan and Co., London and New York, 1890. At Project Gutenberg.

All nine books of The Histories are online in English and Greek at Project Gutenberg and Perseus Digital Library. The excellent Perseus version (English translation by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1920), annotated and with cross-reference links, presents a short section of a book on each web page, whereas the simpler Gutenberg layout (also with notes) displays an entire book on a single page.

The Sacred Text Archive has a parallel text version of The History of Herodotus, with the Greek and English versions displayed side by side. |

|

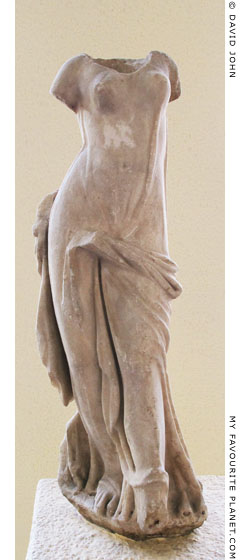

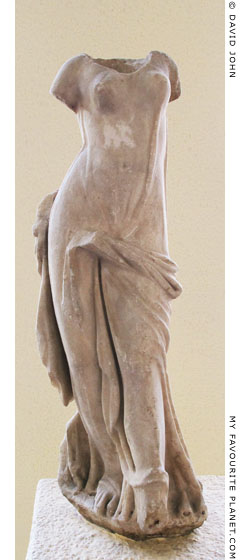

Marble statuette of a female

dancer from Pergamon.

Hellenistic period, 150-30 BC.

Izmir Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 608. |

|

6. Xenophon of Athens (Ξενοφῶν, circa 430-354 BC), general, historian and philosopher; pupil of Socrates.

Xenophon, Anabasis (The March Up Country), Book 7, chapter 8, sections 8-23. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Bust of Xenophon in Bergama Archaeological Museum

Inv. No. VTS 65/615; Museum Inv. No. 784.

Height 49.5 cm.

The bust was found in 1965 along the colonnaded street leading to the Asklepieion. The right side of the head is badly damaged, but has been identified as a portrait of Xenophon by comparison with other similar busts made about the same time ("late Antonine period") and thought to be modelled on an original of the late 4th century BC:

A portrait herm bust of Xenophon in the Graeco-Roman Museum, Alexandria, Egypt, inscribed with the name Xenophon in Greek on the front of the herm;

A marble herm bust in the Prado, Madrid. Inv. No. 100-E.

Other portrait busts have also been found on the colonnaded street, including one of a philosopher, perhaps Socrates (also in Bergama Museum, Inv. No. 772).

8. Lysimachus, "King of Thrace"

Lysimachus (Λυσίμαχος, Lysimachos, circa 360-281 BC) was born in Pella, the capital of Macedonia, and was the son of Agathocles, a Thessalian noble and favourite of Alexander the Great's father Philip II. He only ruled over the Hellenized coastal areas of Thrace; much of the interior was still controlled by Thracian tribes. Seuthes III (Greek, Σεύθης, ruled circa 331-300 BC), king of the Odrysians of eastern Thrace, proved a challenge for Lysimachus. They engaged in at least two battles, the results of which were inconclusive, and it is thought that they made a peace treaty.

See A brief history of Thrace

9. Lysimachus' treasure in Pergamon

Strabo (Στράβων, 64/63 BC - circa AD 24 AD), Greek historian, geographer and philosopher from Amaseia in Pontus (today Amasya, Turkey).

The Geography of Strabo, Book 13, Chapter 4, Section 1. Edited by H. L. Jones. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

"It is pertinent to add here an account of Attalus, because he too is one of the Athenian eponymoi. A Macedonian of the name of Docimus, a general of Antigonus, who afterwards surrendered both himself and his property to Lysimachus, had a Paphlagonian eunuch called Philetaerus. All that Philetaerus did to further the revolt from Lysimachus, and how he won over Seleucus, will form an episode in my account of Lysimachus. Attalus, however, son of Attalus and nephew of Philetaerus, received the kingdom from his cousin Eumenes, who handed it over. The greatest of his achievements was his forcing the Gauls to retire from the sea into the country which they still hold."

"And at the same time Philetaerus, to whom the property of Lysimachus had been entrusted, aggrieved at the death of Agathocles and suspicious of the treatment he would receive at the hands of Arsinoe, seized Pergamus on the Caicus, and sending a herald offered both the property and himself to Seleucus.

Lysimachus hearing of all these things lost no time in crossing into Asia [281 BC], and assuming the initiative met Seleucus, suffered a severe defeat and was killed. Alexander, his son by the Odrysian woman, after interceding long with Lysandra, won his body and afterwards carried it to the Chersonesus and buried it, where his grave is still to be seen between the village of Cardia and Pactye."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 1, and chapter 10, sections 4-5. At Perseus Digital Library.

10. Names of the rulers of Pergamon

Scholars appear neither certain nor united about the etymology, meaning or significance of many ancient Greek names. Here are some of translations and interpretations of the names of Hellenistic rulers offered by various sources.

Alexander (Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros), from alexein, to defend, and andros, man; hence defender of mankind.

Lysimachus (Λυσίμαχος), from λυσις (lysis) a release, loosening, and μαχη (mache) battle. The name has been variously interpreted as describing one who makes war, literally "looses battle" (perhaps as in "Cry 'Havoc!', and let slip the dogs of war" in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar); "free battle"; "freedom fighter"; and even one who ends war by a "release from battle".

Seleucus (Σέλευκος, Seleukos), possibly from λευκος (leukos), bright, white; hence brilliant, shining.

Philetaerus (Φιλέταιρος), fond of one's comrades or the good comrade.

Eumenes (Ευμένης), favourable, benign, genial, propitious.

Attalos (Ἄτταλος), increased, nourished.

Aristonikos (Αριστόνικος), the best victor or gaining glorious victory.

11. Ptolemy Keraunos

Ptolemy Keraunos (Πτολεμαῖος Κεραυνός, Ptolemy Thunderbolt; died 279 BC), the eldest son of Ptolemy I of Egypt. When his younger half-brother Ptolemy (later Ptolemy II) was named heir to the throne in 282 BC he left Egypt and went to live at the court of Lysimachus. His half-sister Arsinoe (later Arsinoe II of Egypt) had married Lysimachus, and another sister Lysandra was the wife of Lysimachus' son Agathocles.

After the death of Lysimachus and Seleucus in 281 BC, he had himself acclaimed as king of Macedonia by the army and married Arsinoe. She plotted against him, and he killed two of her sons by Lysimachus (Lysimachus and Philip) in 279 BC. She fled to Samothraki where she took refuge. Shortly after Keraunos was captured and killed by the invading Gaulish leader Bolgios. Arsinoe returned to Egypt where she married her brother Ptolemy II.

12. The Gauls in Anatolia

There are few accounts of the Celts in Greece and Asia, but Pausanias provided a short summary of the conflicts between the Gauls (Galatians) and Pergamens.

"The greater number of the Gauls crossed over to Asia by ship and plundered its coasts. Some time after, the inhabitants of Pergamus, that was called of old Teuthrania, drove the Gauls into it from the sea. Now this people occupied the country on the farther side of the river Sangarius capturing Ancyra [Ἄγκυρα, today Ankara, Turkey], a city of the Phrygians, which Midas son of Gordius had founded in former time. And the anchor, which Midas found, was even as late as my time in the sanctuary of Zeus, as well as a spring called the Spring of Midas, water from which they say Midas mixed with wine to capture Silenus. Well then, the Pergameni took Ancyra and Pessinus which lies under Mount Agdistis, where they say that Attis lies buried.

They [the Pergamenes] have spoils from the Gauls, and a painting which portrays their deed against them. The land they dwell in was, they say, in ancient times sacred to the Cabeiri, and they claim that they are themselves Arcadians, being of those who crossed into Asia with Telephus. Of the wars that they have waged no account has been published to the world, except that they have accomplished three most notable achievements; the subjection of the coast region of Asia, the expulsion of the Gauls therefrom, and the exploit of Telephus against the followers of Agamemnon, at a time when the Greeks after missing Troy, were plundering the Meian plain thinking it Trojan territory. Now I will return from my digression."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 4, sections 5-6. At Perseus Digital Library.

13. Attalus I and Aegina

Aegina was captured by the Roman fleet commanded by Proconsul Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus in 210 BC, during the First Macedonian War (214-205 BC). The fleet of Attalus I may have been involved in taking the island. The Greek historian Polybius (Πολύβιος, circa 200-118 BC), recounted the events when commenting on a speech by Cassander of Aegina at a meeting of the Achaean League at Megalopolis in 186/185 BC, during the reign of Eumenes II, Attalus' son and successor.

"Next rose Cassander of Aegina and reminded the Achaeans of 'The misfortunes which the Aeginetans had met with through being members of the Achaean league; when Publius Sulpicius sailed against them with the Roman fleet, and sold all the unhappy Aeginetans into slavery.' In regard to this subject I have already related how the Aetolians, having got possession of Aegina in virtue of their treaty with Rome, sold it to Attalus for thirty talents."

Polybius, Histories, Book 22, chapter 11. At Perseus Digital Library.

If there was a mention of the sale of Aegina to Attalus earlier in Polybius' Histories it has not survived. He did mention Publius Sulpicius' harsh reply to pleas by the captured Aeginetans that they be ransomed rather than enslaved (Book 9, chapter 42).

According to Livy (Titus Livius, 64/59 BC - 17 AD), citing Valerius Antias (first century BC), Aegina was presented as a gift to Attalus along with the war elephants given up by Philip V of Macedonia according to the terms of his peace treaty with Rome in 196 BC, following his defeat by Proconsul Titus Quinctius Flamininus at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. However, Attalus is thought to have died in Pergamon before or shortly after the battle.

"Valerius Antias adds that the island of Aegina and the elephants were presented as a gift to Attalus, who was absent ..."

Livy, The History of Rome, Book 33, chapter 30. At Perseus Digital Library.

14. The death of Attalus I

See:

Livy, The History of Rome, Book 33, chapters 1-2. At Perseus Digital Library.

"At the same time King Attalus, who had fallen ill at Thebes and then removed from Thebes to Pergamum, died in his seventy second year, after he had been on the throne for forty four years. Fortune had bestowed upon this man nothing but wealth to give him hope of royal power. By using this both wisely and splendidly he brought it about that he seemed worthy of the throne, first in his own eyes, then in those of others. Then when in a single battle he had conquered the Gauls, a people the more terrible to Asia by reason of their recent arrival, he assumed the title of king, and thenceforth his greatness of soul always matched the greatness of his distinction. He ruled his subjects with perfect justice, exhibited remarkable fidelity to his allies, was courteous to his wife and sons — four survived him — and kind and generous to his friends; he left a kingdom so strong and well-established that possession of it was handed down to the third generation."

The History of Rome, Book 33, chapter 21. At Perseus Digital Library.

15. The altar on Aegina

Aegina Archaeological Museum, Greece. Inv. No. 1331.

Height 48 cm, diameter 28.5 cm.

The cylindrical altar of poros limestone was found at the harbour of Aegina, near the Church of Kimisis Tis Theotokou (Κοίμησις της Θεοτόκου, Παναγίτσα). The lettering of the inscription was painted red, and is thought to have been originally gilded.

Διὶ καὶ Ἀθηνᾶι

ὑπὲρ βασιλέως

Ἀττάλου

Σατυρῖνος, Καλλίμαχος

καὶ οἱ ὑπ’ αὐτοὺς ἡγεμόνες

καὶ στρατιῶται.

To Zeus and Athena, for King Attalus, (dedicated by) Satyrinos, Kallimachos and their subordinate officers and soldiers.

Inscription IG IV² 2 765 (SEG 25 320).

See: Κωνσταντίνος Κουρουνιώτος, Αιγίνης μουσεϊον (Konstantinos Kourouniotes, Aigina Museum). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1913, pages 86-98 (altar on page 91, Βωμός μεζ επιγραφής γραπτής, and fig. 8). Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1913. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

This is one of a number of altars and other dedications to Attalus I found at Pergamon and elsewhere, thought to be among the earliest signs of the cult worship of deified members of the Attalid dynasty. From a fragmentary honorific decree found in Athens (inscription IG II² 885; Epigraphical Museum, Athens, Inv. No. EM 2672) it seems that Attalus was made synnaos (σύνναος, temple-sharing deity) with Aegina's mythical hero Aiakos (Αἰακός, son of Zeus and Aegina, grandfather of Achilles and Ajax). There was also an Attaleion, a centre for the cult of the Pergamene kings, in Aegina (IG IV² 2 749, honorific decree for Kleon; OGIS 3291 47), thought to have been near the Temple of Apollo at Kolonna.

16. The statues of defeated Gauls at Pergamon

The history of the two sculptures is conjectural. Following its discovery, the "Capitoline Gaul" was at first known as the "Dying Gladiator", and the "Ludovisi Gaul" was named "Arria and Paetus". However, the figures were subsequently identified as Gauls (or Galatians) and associated with Pergamon, and it was considered that they could only have been produced by Greek sculptors. It has also been suggested that they were made at Pergamon, perhaps even around the time of the bronze originals.

"With our present knowledge of the history of art, we cannot suppose that sculpture in Rome was ever capable of originating a figure of such wonderfully powerful modelling, and such dignity of pathos ; nor is the choice of subject in itself credible."

Ernest Arthur Gardner, A handbook of Greek sculpture, page 454. MacMillan and Co., London, 1897.

Pliny the Elder mentioned a number of artists who had made (bronze) sculptures of battles between the Attalids and Galatians, but did not say when these works were made or where they stood.

"Several artists have represented the battles fought by Attalus and Eumenes with the Galli; Isigonus, for instance, Pyromachus, Stratonicus, and Antigonus, who also wrote some works in reference to his art."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

These names and others have been discovered on inscribed statue bases at Pergamon. A little later in the same chapter, Pliny wrote that a sculptor named Epigonus had made a statue of a trumpeter.

"Epigonus, who has attempted nearly all the above-named classes of works [statues of gods, philosophers, comic playwrights and athletes], has distinguished himself more particularly by his Trumpeter, and his Child in Tears, caressing its murdered mother."

Inscribed signatures of a sculptor named Epigonos (Επίγονος ἐποίησεν) have also been found at Pergamon.

See: Max Fraenkel, Altertümer von Pergamon, Band 8, Die Inschriften von Pergamon, I. Bis zum Ende der Königszeit, Nos. 12, 22b, 29, 31, 32. Königliche Museen zur Berlin. Verlag von W. Spemann, Berlin, 1890. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Since a large trumpet lies on the base of the "Capitoline Gaul" statue, encircling the figure, many scholars have believed that it is the "Trumpeter" (tubicen) by Epigonus. However the sculpture has been extensively restored, and many parts, including the sword lying on the base, are modern. |

|

|

| |

A hypothetical reconstruction by A. Schober of "the Large Gallic Group"

dedicated by Attalus I in the temple of Athena Polias in Pergamon.

Source: A. Schober, Epigonos von Pergamon und die pergamenische Kunst.

In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 53 (1938), pages 126-149.

|

17. The invention of parchment at Pergamon

In his encyclopedic work Natural History (Naturalis Historia), Pliny the Elder ascribed the story of the invention of parchment at Pergamon to the Roman scholar Varro (Marcus Terentius Varro, also known as Varro Reatinus, 116-27 BC), most of whose works have been lost.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 13, chapter 21. At Perseus Digital Library.

18. Writing on animal skins

Herodotus writes that the Ionian name for paper was "skins" (διφθέραι, diphtherai), which he supposes went back to ancient times before papyrus was easily available, and that many "foreign peoples" still write on goat and sheep skins.

Herodotus, The Histories, Volume II, Book V, 58. At Project Gutenberg [see note 5]. |

|

|

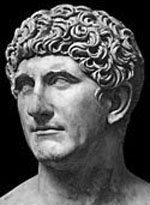

19. Marc Antony and the Library of Pergamon

41-31 BC the Roman politician and general Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius, 83-30 BC) ruled the eastern half of the Roman Empire, which included Greece and Asia Minor, while Octavian (later to become Emperor Augustus) ruled the west.

If the accusation of Calvisius is true, Antony may have given the books from Pergamon's library to Cleopatra to replace those destroyed by the fire at the Library of Alexandria in 48 BC. Julius Caesar is said to have caused the fire accidentally when he burnt his own ships in Alexandria harbour as a tactical ploy. Read more about Antony and Cleopatra on Athens Acropolis gallery page 8.

Plutarch (Greek: Πλούταρχος; name as Roman citizen Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, Μέστριος Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), Greek historian, biographer and essayist, born in Chaeronea, Boeotia, central Greece.

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives Volume IX: The Life of Antony. Loeb Classical Library, 1920. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

20. Coins of Mithradates VI minted in Pergamon

Image source, a woodcut in: Henry George Liddell, A History of Rome, from the earliest times to the establishment of the Empire, page 593. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1859.

The Persian name Mithradates (Given by Mithra; Greek, Μιθραδάτης) was written Mithridates (Μιθριδάτης) by Roman authors, and this spelling has since been followed by scholars. However, since the discovery of the Greek spelling on coins and inscriptions, writers are increasingly using this. The kingdom of Pontus (Πόντος) was on the south coast of the Black Sea (Εύξεινος Πόντος, Euxinos Pontos, Hospitable Sea), at the northeast of the Anatolian peninsula (Asia Minor).

As with many of the dates given for incidents in ancient history, several of those concerning Mithradates VI are inexact and remain subjects of debate.

Gold staters and silver tetradrachms of this type are engraved with a date, based either on the Bithynian Era (BE) or Pergamene Era. Mithradates VI began using the calendar of the Bithynian Era on his coins around 108 BC or a little later, after he made an alliance with Nikomedes III Euergetes (reigned 127-94 BC), king of Bithynia, in northwestern Anatolia. The dates of this era were calculated from 297 BC, when Zipoites I proclaimed himself the first king of Bithynia (see note on the Doidalsas page). The Pergamene Era, dated from the "liberation" of Pergamon by Mithridates VI in 89 BC, appeared on his coins minted there 89-85 BC.

The earliest silver tetradrachms of Mithradates VI with the Pergamon monogram are actually dated 95 BC (202 BE), and further gold and silver coins were struck as late as 75-74 BC (222-223 BE), during the Third Mithridatic War (75-63 BC).

See, for example:

Ancient Coinage of Pontos, Kings, Mithradates VI, at Wildwinds.

Mithradates VI, lots from auctions, at CoinArchives.

Gold stater, Pergamon 74 BC, (Roma Numismatics Ltd, Auction XIX, Lot 408: Kingdom of Pontos. Mithradates VI Eupator AV Stater. Pergamon, dated month 12, year 223 BE (September 74 BC). At NumisBids. |

| |

Mark Antony.

Marble bust.

Vatican Museums, Rome. |

| |

Cleopatra VII.

Marble head, 40-30 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. 1976.10. |

| |

| |

The reconstructed fragments of the Astynomoi Law stele.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2006.

|

21. The Astynomoi Law of Pergamon

Also referred as the "Law of Astynomoi", "Astynomos Law" or "Astynomic Law", and in German as "die Astynomeninschrift von Pergamon".

The limestone slab was found shattered into 13 fragments by German archaeologists in 1901, in a house at the southeast of Pergamon's Lower Agora, where it had been used as flooring. The top left corner of the slab is missing, but otherwise it contains an almost complete inscription proclaiming the legislation concerning the powers, duties and responsibilites of the astynomoi (Ancient Greek, ἀστυνόμος, plural ἀστυνόμοι, municipal administration; from ἄστυ, city, and νόμος, law), civic officials charged to control the condition and maintenance of buildings, thoroughfares and waterworks. The modern Greek words αστυνομία (astynomia, police) and αστυνόμος (astynomos, policeman) are derived from this concept.

The law states who is responsible for the work and costs involved in maintaining public roads, streets and paths, water cisterns, springs, conduits, fountains, toilets, sewers and rubbish collection, as well as public and private boundary walls. The aim is evidently order and cleanliness, and the law specifically forbids clothes to be washed or animals to drink from public fountains. Stealing paving stones is also among activities prohibited.

Each astynomos was responsible for a particular zone, in which he was to record and report on cisterns in private houses, and ensure that owners kept them clean and covered. He was obliged to impose fixed fines on transgressors, and hand the money either to the civic treasurers or to those who suffered damage due to a neighbour's negligence; officials who failed to charge the fine or report to the authorities were themselves fined.

The office of astynomos existed in many Greek cities, particularly in Ionia. In the fourth century BC Athens had 10 astynomoi who were selected by lot. Aristotle mentions astynomoi as a type of official essential to the ideal city.

See: Aristotle, Politics, Book VI, Section 1321b, lines 18-27. At Persus Digital Library.

The inscription has been dated to the second century AD, probably during the reign of Emperor Trajan or Hadrian. However, it is thought that the legislation itself may have originally been written in the time of the Attalid kings, in the second century BC, perhaps during the reign of Eumenes II (197-159 BC). The epigraphist Günther Klaffenbach (1890-1972), who wrote a study of the inscription in 1953, believed that the Attalid law was defunct by the Roman Imperial period, and that it was meant as a "summa honoraria", a dedication to the ancient office of the astynomoi, set up by an astynomos as a gift to the city.

The slab is made of light blue-grey limestone.

Width 105 cm, present height 82 cm, thickness 5 - 8.5 cm.

The upper left corner of the slab, containing the first 34 lines of column 1, is missing. The bottom of the slab has a roughly-cut edge.

237 lines of text have survived, written in 4 columns, each around 25 cm wide, with 35 letters per line. The law is arranged in paragraphs, similar to modern legislative clauses.

Inscription SEG 13 521 (= OGIS 483).

See:

H. von Prott and Walther Kolbe, Die Astynomeinschrift. Die Arbeiten zu Pergamon 1900-1901. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band XXVII, 1902, pages 47-77. Beck und Barth, Athens, 1902. At the Internet Archive.

Günther Klaffenbach, Die Astynomeninschrift von Pergamon. In: Abhandlungen der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Klasse für Sprachen, Literatur und Kunst, Jahrgang 1953, Nummer 6, Pages 3-25, 2 plates. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 1954.

James H. Oliver, The date of the Pergamene Astynomos Law. Hesperia, Volume 24, No. 1 (January - March 1955), pages 88-92. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. At ascsa.edu.gr.

Sara Saba, Cisterns in the Astynomoi Law of Pergamon. Essay in: Cynthia Kosso, Anne Scott, The Nature and Function of Water, Baths, Bathing, and Hygiene from Antiquity Through the Renaissance, pages 249-262. Brill, Leiden, 2009.

Sara Saba has recently written a new study of the Astynomoi Law, which I have unfortunately not yet seen:

Sara Saba, The Astynomoi Law from Pergamon: A New Commentary (Volume 6 of the series Die hellenistische Polis als Lebensform). Verlag Antike, Mainz 2012.

22. "The acropolis of Pergamus" by Thomas Allom

"The acropolis of Pergamus", 1882, by English architect and landscape artist Thomas Allom (1804-1872). Engraved by Archibald L. Dick (1805 - circa 1855).

From: Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823-1901), A pictorial history of the world's great nations, from the earliest dates to the present time. Selmar Hess, New York, circa 1882.

Volume 1 Volume 2 at the Internet Archive. |

|

|

23. Bust of Carl Humann in Berlin

Bust of Carl Humann by Adolf Brütt (1855-1939), Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

The bust was unveiled on 18 December 1901, when Kaiser Wilhelm II opened the first Pergamon Museum (demolished in 1908). In the present Pergamon Museum (opened 1930) it has been relegated to a back-lot, and has stood for years out of sight and inaccessible to the public, in a corridor leading to a lecture room behind the Pergamon Altar, opposite the bust of another German archaeologist, Theodor Wiegand (1864-1936) by Carl-Blümel (photo right). Wiegand also excavated at the Heraion on Samos (1910-1911) and at Pergamon (1927), and in 1898 rediscovered the site of the ancient Panionion, near the Turkish village of Güzelçamlı, on the coast opposite Samos (see Samos gallery page 29).

Currently the hall of the Pergamon Altar and the entire left wing of the Pergamon Museum are closed for renovation work until at least 2020.

24. Bust of Alexander Conze in Berlin

Archaeologist Alexander Conze (1831-1914) was Director of Ancient Sculptures in Berlin 1878-1886. He led the the excavations at Pergamon 1878-1886 for the Königliche Museen zu Berlin (Royal Museums, Berlin, now the State Museums, Berlin, SMB). He also led excavations at Samothraki for the Austrian Imperial Ministry of Culture and Education in 1873 and 1875.

His many publications include a catalogue of the Ancient sculptures in the Royal Collection of Classical Antiquities in Berlin, 1891.

Bronze bust made by Fritz Klimsch in 1913.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1974. |

| |

Bust of Carl-Blümel

(1893-1976),

German sculptor

and archaeologist.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 1977. |

| |

Maps, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |