| |

The orchestra (stage) of the Theatre of Dionysos. |

| |

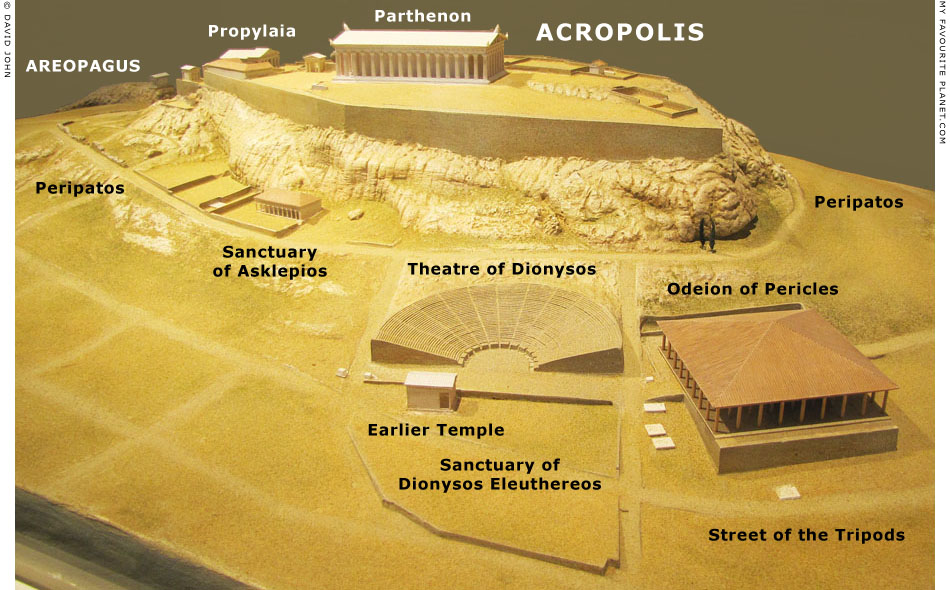

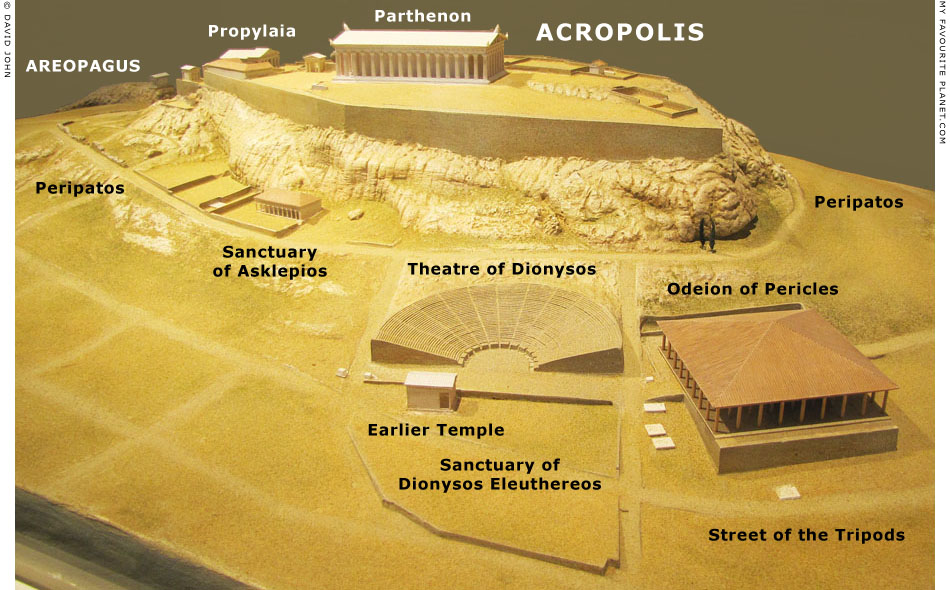

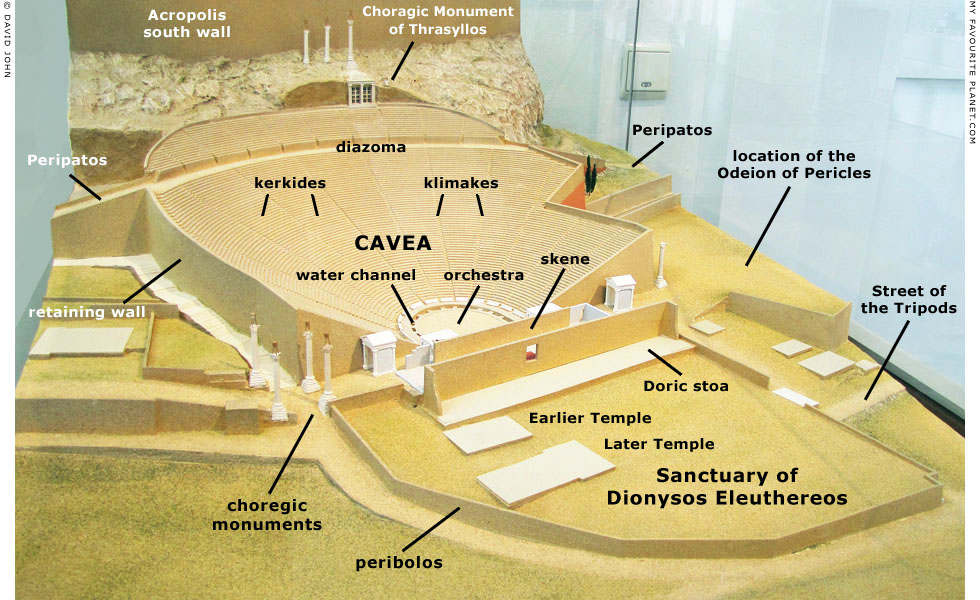

A simplified model of the Athenian Acropolis in the mid 5th century BC, showing

the Theatre of Dionysos, in front of which is the Earlier Temple of Dionysos.

To the right is the Odeion of Pericles. Above the theatre ran the Peripatos,

the circuit path around the foot of the Acropolis (see gallery page 34).

Reconstruction by M. Korres and P. Dimitriadis, Athens, 2001. Wood and cork.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Re 2002.4. |

| |

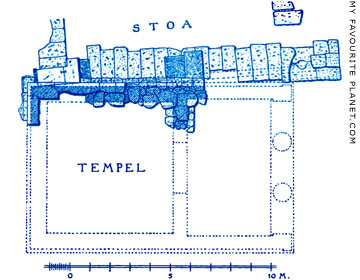

The Sanctuary and Temple of Dionysos Eleuthereos

The temenos (τήμενος, sacred area) was surrounded by a peribolos (περίβολος, perimeter wall) and was entered by a propylon (monumental gateway) at the east side. The road leading from the city to the propylon became known as the Street of Tripods (see below).

Directly in front (south) of the theatre stood the Earlier Temple of Dionysos Eleuthereos (Διονύσος Ελευθερέως, Dionysos the Liberator), to whom the sanctuary and the theatre were dedicated.

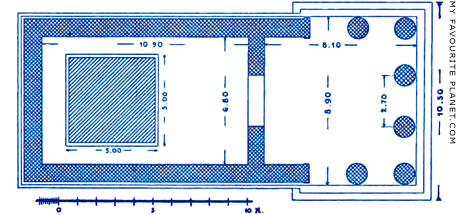

At the east side of this small Doric temple, built around 550-500 BC, was an entrance porch (pronaos) supported by two columns and side walls (distyle in antis), and a cella which housed the cult statue (ξόανον, xoanon) of Dionysos Eleuthereos [7]. Only the foundation and part of the krepis (stepped platform) of this temple have survived. The epiphet Eleuthereos may derive from the story that the Athenians took the statue from Eleutherai (Ἐλευθεραί), near the border between northern Attica and Boeotia, on a plain shared with neighbouring Plataea (Πλάταια).

"In this plain is a temple of Dionysus, from which the old wooden image was carried off to Athens. The image at Eleutherae at the present day is a copy of the old one."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 38, section 8.

The Later Temple of Dionysos (see the model below) was built around 350 BC to the south of the earlier one. This larger, tetrastyle prostyle temple, with 6 columns at the entrance on the eastern end, housed the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Dionysos made by Alkamenes in the 2nd half of the 5th century BC (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 20, section 3). The later temple was not built to replace the earlier, which remained in use. The foundation and the base of the cult statue have survived, but are usually covered for protection.

Around the same time a new propylon, of which only the foundation now exist, was built to replace the earlier gateway. To the southeast of the Later Temple are the foundations of a large altar, which are also usually covered. |

|

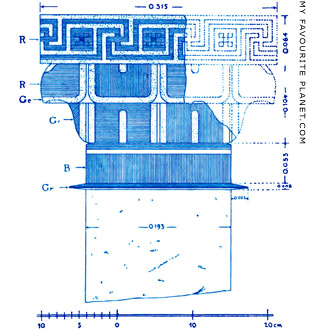

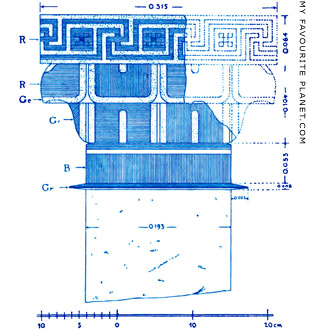

Reconstruction of the capital of one of the

antis walls of the Earlier Temple of Dionysos

Eleuthereos, according to Wilhelm Dörpfeld.

See plans of the the temple below. |

|

| |

The Odeion of Pericles

To the right (southeast) of the theatre, stood the large square Odeion of Pericles (Ωδείον του Περικλέους). The original building was said to have been constructed with the masts and yards of Persian ships taken as booty after the naval Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, and to have resembled the tent of Xerxes. Given the trophy monument aspects of the building, it has been suggested that it was built by Themistocles around 478-477 BC, and used as a shelter for theatre audiences during bad weather and for chorus rehearsals. Much later, the Stoa of Eumenes, built around 170 BC, fulfilled these functions. The tent-like construction was converted into an odeion (ᾠδεῖον, singing place) by Pericles around 455 BC as a venue for the musical and singing contests held during the Panathenaic Festival. [8]

The odeion was destroyed in 87-86 BC during the siege of Athens by the Roman general Sulla in the First Mithridatic War, and a new odeion was financed around 61 BC by the Cappadocian king Ariobazanes II (see photo, below right), and built by Gaius and Marcus Stallius and Menalippos (Μενάλιππος) [9].

Today only traces of the building's foundations remain. Archaeological investigations have revealed that the building covered an area 62.4 x 68.6 metres, and had a roof supported by ninety internal pillars, in nine rows (east-west) of ten (north-south). This design seems a little inappropriate for a performance space, as the forest of pillars, with a spacing of only around 6 metres, would have presumably obstructed the audiences' view of the performances. According to current theories the odeion had a pyramidal roof and no walls, as can bee seen in the model above, and this would account for need for so many supporting pillars. This would also have helped solved problems of lighting and ventilation, but also affected the acoustics of the building, probably not for the better.

According to another theory, the rows of columns and the shape of the roof (although Plutarch described it a conical, see note 8), were designed to imitate the "Great King's pavilion" (skene, tent) thought to have been taken by the Athenians after the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. Xerxes had actually left Greece after the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, before this battle (see History of Stageira part 4), and the tent may have been that of his general Mardonius (although he could well have used the luxurious tent hastily abandoned by king; wouldn't you?). The odeion's dimensions are also said to be similar to those of the royal pavilion known as "the Hall of Hundred Columns" in Persepolis (68.5 x 68.5 metres, 10 x 10 columns), the construction of which was started by Xerxes and completed during the rule of his son and successor Artaxerxes I. This building and the Themisoclean/Periclean odeion, may then have originally been tents later replaced by stone structures.

This theory has been challenged and Plutarch's report has been called "a Hellenistic fable", invented to explain the "Persoid" design of the anomalous building. But if the odeion was not designed in imitation of a Persian tent, why would any Greek or Roman architect create a theatre so unusual and un-Greek (its layout is unique in Greek architecture), and so apparently unsuitable for public performances? The odeion's unusual design and square plan have been compared with that of the Telesterion, the temple of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, which according to Vitruvius was designed by Iktinos, one of the architects of the Parthenon (see Demeter and Persephone).

By the time Pausanias visited Athens in the mid 2nd century AD (see note 8) it had probably been abandoned as a performance venue in favour of the Odeion of Agrippa (built around 15 BC) in the Agora, and the Odeion of Herodus Atticus was opened shortly after he left. It is thought to have been finally destroyed during the Herulian invasion in 267 AD (see gallery page 6).

The location of the odeion was discovered in 1914, during excavations directed by Panagiotes G. Kastriotes (Παναγιώτης Γ. Καστριώτης, 1859-1931) of the Archaeological Society of Athens. |

| |

The Street of the Tripods

Bronze tripods were awarded as prizes for performances in dramatic and choral contests and publicly displayed on monuments set up by the choregos (χορηγός), the sponsor of the winning performing group. In Athens, such choragic (or choregic) monuments were erected around or near the Theatre of Dionysos, and particularly on the Street of the Tripods (Οδός Τριπόδων, Odos Tripodon), which led from the Prytaneion to the propylon (monumental gateway) of the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos. The location of the Prytaneion remains uncertain [10], but the street known today as Odos Tripodon winds its way through the Plaka distict, and the famous Choragic Monument of Lysikrates (335/334 BC) still stands there.

"Leading from the prytaneum is a road called Tripods. The place takes its name from the shrines, large enough to hold the tripods which stand upon them, of bronze, but containing very remarkable works of art, including a Satyr, of which Praxiteles is said to have been very proud."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 20, section 1. |

| |

The Peripatos

Visitors to the Acropolis can still walk along the Peripatos, the ancient circuit path around the foot of the Acropolis. It can be accessed from the entrance to the archaeological site of the South Slope of Acropolis and the Theatre of Dionysos on the the southeast side, or from the main entrance to the Acropolis on the west side (ask for directions to the Caves of Apollo and Pan). See gallery pages 2, 4, 5 and 34. |

| |

The Sanctuary of Asklepios

The remains of the sanctuary of the healing god Asklepios and his daughter Hygieia are located along the Peripatos to the west of the top of the theatre. See gallery page 34. |

|

Athenian coin, believed to be a theorikon

(θεωρικόν; Plural, θεωρικά, theorika), a

token issued by a public fund as a

theatre ticket, showing the Odeion of

Pericles. Found at the site of the odeion.

Source: Παναγιώτης Γ. Καστριώτης,

Το Ωδείον του Περικλέους (Panagiotes

G. Kastriotes, The Odeion of Pericles),

fig. 2, page 147.

In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1914,

pages 143-166. Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική

Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal

of the Archaeological Society of Athens).

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

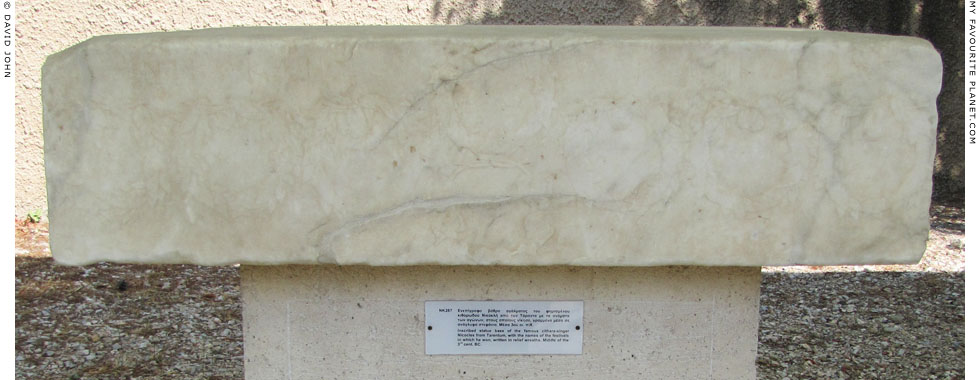

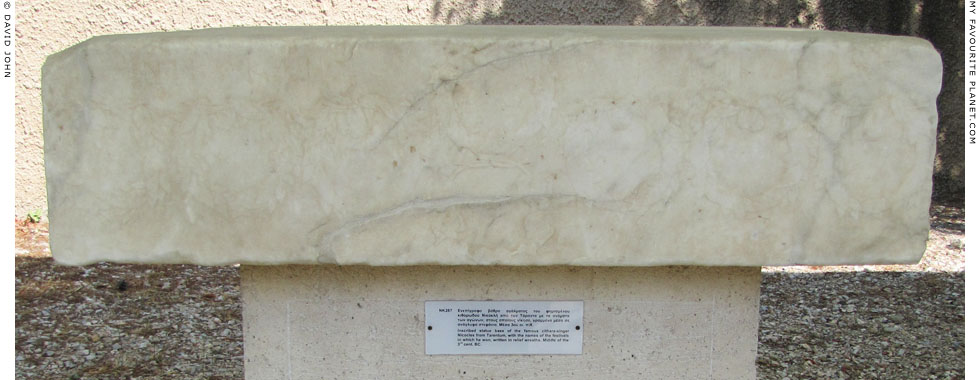

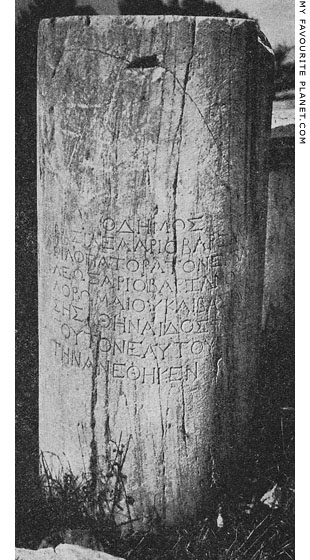

An inscribed column drum with a dedication

by the demos to King Ariobarzanes II of

Cappadocia, who financed the rebuilding

of the Odeion of Pericles [9]. Known since

the mid 18th century and rediscovered by

archaeologists in 1862, built into a later

wall of the skene of the theatre.

63-52 BC. Eleusinian marble. Height 163 cm,

diameter 74.5 cm (bottom) - 71.3 cm (top).

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

Inv. No. NK 284. Inscription IG II 2 3427. |

| |

| |

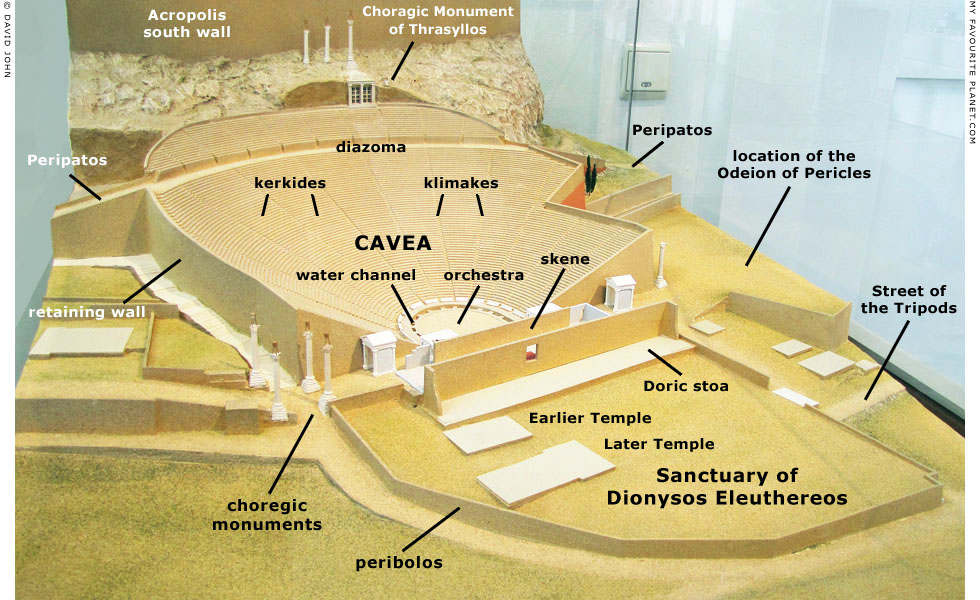

Another model of the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos in the late 5th century BC, as seen from above.

Model of the Acropolis designed by M. Korres, created by P. Demetriades

and G. Angelopoulos, 1998. British Museum, London. Scale 1:500. |

| |

A model of the Theatre of Dionysos as it would have appeared around 310 BC,

following the building of the cavea (audience seating area) and orchestra

(performing/dancing floor) in stone between 360 and 330 BC, thought by

many scholars to have been completed during the archonship of Lycurgos

(Λυκούργος, Lykourgos), 338-324 BC.

Reconstruction by M. Korres, N. Gerasimov and

P. Dimitriades, 2002. Plaster. Scale 1:200.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Re 2002.5. |

| |

The cavea was extended further up the south slope of the Acropolis, and an extra upper level was added, separated from the lower level by a diazoma (διάζωμα, girdle) walkway (see theatre terms below), which was part of the peripatos, the circuit path around the foot of the Acropolis (gallery pages 2, 4, 5 and 34). The nick on the east (right) side of the cavea was due to the space required between the theatre and the neighbouring Odeion of Pericles (not shown on model, see above).

A skene (stage building) was built to the south of the orchestra, behind it from the point of view of the audience. It shared its back wall with a Doric stoa (colonnaded walkway), around 62.3 metres long and 8.1 m wide, which ran from east to west between the front (south) of the theatre and the Earlier Temple. It had a 12 metre long room at the west end, with an opening on the side leading from the single-aisled colonnade of 22 columns which was open to the south. The architect and archaeologist John Travlos suggested that the stoa may have had two storeys. Little remains of these buildings, which were built over during the Roman period, and they have been "blocked in" by the model makers.

The columns in front of the cavea and other monuments around the theatre supported bronze tripods awarded as prizes for theatrical performances. The gated doorway with three columns above the cavea is the entrance to the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos (320/319 BC). |

| |

| |

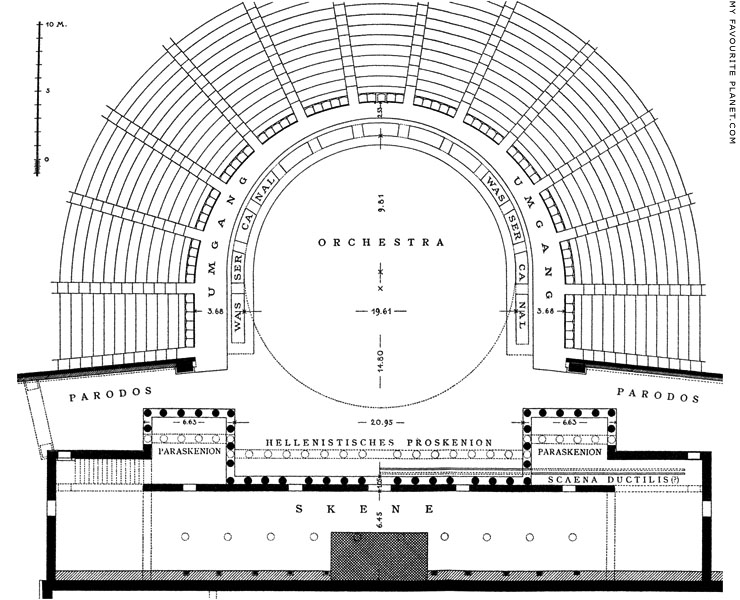

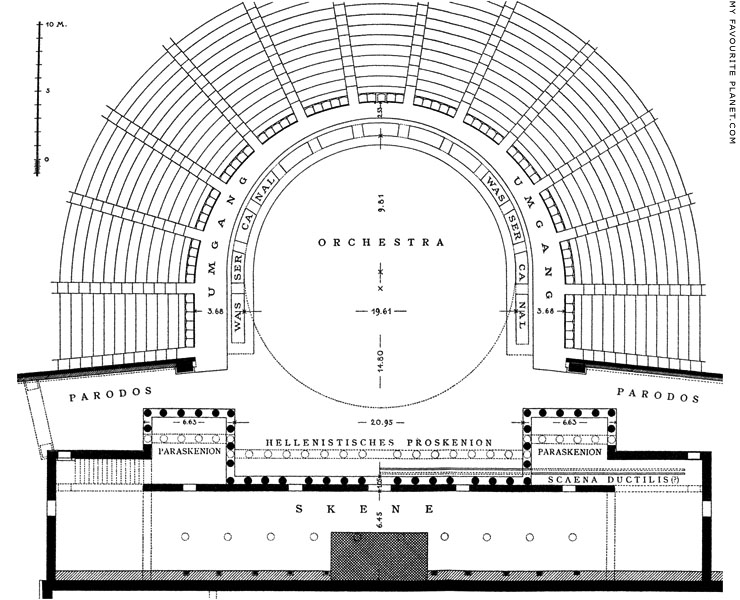

Plan of the Theatre of Dionysos: the cavea, orchestra and skene (stage

building), according to Wilhelm Dörpfeld. Drawn by Wilhelm Wilberg.

The reconstruction shows the theatre during the Hellenistic period, including

the proskenion (raised stage) with a parasekenion projecting from either

side as part of a large, eleborate skene (stage building). A water drainage

channel ran between the cavea and the orchestra, which is shown as circular.

Source: Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Emil Reisch, Das griechische Theater: Beitrage

zur Geschichte des Dionysos-Theaters in Athen und anderer griechischer

Theater, Tafel IV. Barth & von Hirst, Athens, 1896. At the Internet Archive.

|

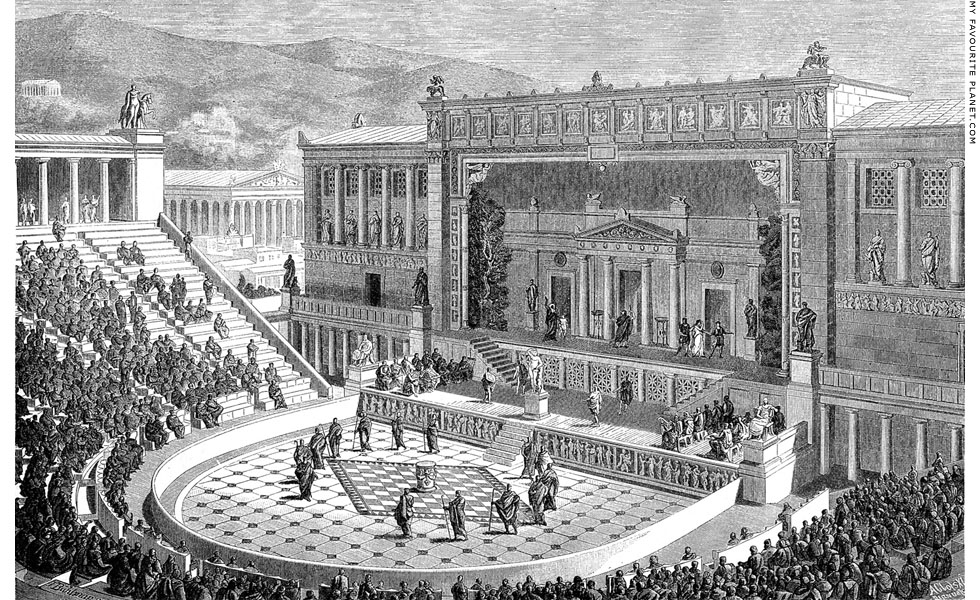

The age old pastimes of storytelling, music-making, dancing and singing have always been practised wherever people gather together. As forms of worship or religious celebration, particular places in or or near a settlement became favoured, where the community could participate or sit and view performances, that is songs and dances by individuals and groups rather than collectively. Hillsides were well-suited as seating places on which ascending rows of spectatators could get a good view. The Greeks called the performance area the orchestra (ὀρχήστρα), meaning dancing place, which in ancient Greek theatres was usually circular.

The Greek institution of theatre evolved from forms of singing and dancing during festivals in honour of the wine god Dionysus, which included processions to the theatron (θέατρον, viewing place) where the festivals were held. A thymele (θυμέλη), an altar for sacrifices to Dionysus, stood in the centre of the orchestra.

Eventually wooden seating and orchestra floorboards were built, then later replaced by stone fittings which became more elaborate and were decorated by reliefs, statues and inscriptions. As the peformance of dramas by actors (an actor was known in Greek as ὑποκριτής, hypokrites, literally answerer) became more important, a skene (σκηνή, literally tent or hut; the root of the English words scene and scenery) was built behind the orchestra for storing props and costumes, and as a place where performers could retire between scenes or to change costumes. A raised platform in front of the skene, known as the proskenion (προσκήνιον), provided an extra performance space and was the forerunner of the modern theatrical stage.

The audience seating area of Greek theatres, the theatron itself, is usually referred to by the Latin word cavea (hollow, cavity, enclosure), the equivalent of the modern auditorium. It was usually a little wider than a semi-circle, and the seating became divided into wedge-shaped blocks known as kerkides (κερκίδες; sigular, κερκίς, kerkis), by staired aisles called klimakes (κλίμακες; singular, κλίμαξ, klimax, stairway or ladder). Where there was more than one row of kerkides, the upper and lower levels were separated by a walkway known as a diazoma (διάζωμα, girdle). See the diazoma of the Hellenistic Theatre of Dionysos in the photo above. The theatre was entered by the paradoi (πάροδος, parados, entrance; plural πάροδοι), either side of the orchestra, at the ends of the cavea.

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods the stage buildings became larger and more monumental (see for example the Odeion of Herodes Atticus), often with extra wings, known as parasekenia (παρασκήνια), projecting from either end of the skene. |

|

| |

The remains of the lower cavea (audience seating area) and orchestra (performance area), viewed from the

northwest. In the background, to the southeast, the 1026 metre high Mount Ymittos (Hymettus), renowned

in ancient times for its industrious bees and their honey, slopes down to the Aegean seaside at Vouliagmeni. |

| |

Reconstruction drawing of the marble thrones, or seats of honour, reserved for priests,

officials, honoured citizens and visiting dignitaries, in the Prohedria (front row) around

the edge of the orchestra, east of the centre of the cavea in the Theatre of Dionysos.

Source: Albert Müller (1831-1916), Lehrbuch der griechischen Bühnenalterthümer,

Fig. 8, page 92. Volume 3 of K. F. Hermann's Lehrbuch der griechischen Antiquitäten.

J. C. B. Mohr, Freiburg, 1886. At the Internet Archive.

After Ernst Ziller, in Carl von Lützow, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Volume XIII,

Fig. 2, page 197. E. A. Seemann Verlag, Leipzig, 1878.

Also published in: Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach den

Berichten der Alten und den neusten Erforschungen, Fig. 116, page 247.

Julius Springer, Berlin, 1888. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

The marble throne of the priest of Dionysus in the

centre of the Prohedria of the Theatre of Dionysos.

4th century BC. Pentelic marble.

|

Literally the best seat in the house, in the centre of the theatre's front row. The backrest and the seat support are decorated with reliefs. Along the bottom of the seat support is the inscription:

ἱερέως Διονύσου Ἐλευθερέως

Inscription IG II 2 5022.

Image source: Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach den Berichten der Alten und den neusten Erforschungen, Fig. 115, page 245. Julius Springer, Berlin, 1888. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

After Ernst Ziller, in Carl von Lützow, Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Volume XIII, Fig. 1, page 196.

E. A. Seemann Verlag, Leipzig, 1878. |

|

| |

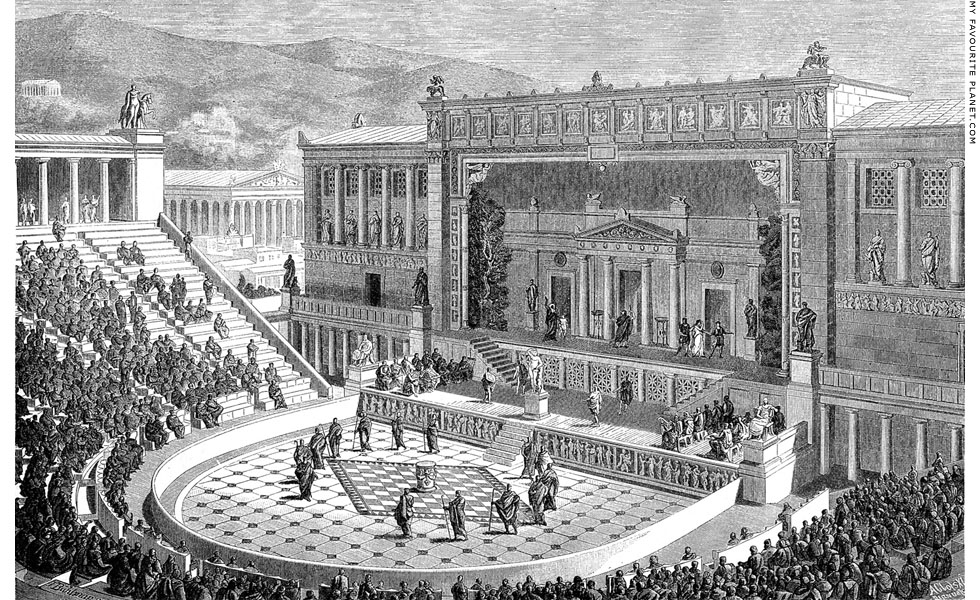

An imaginative reconstruction drawing of the Theatre of Dionysos during the Roman period.

Illustration from Jakob von Falke (1825-1897), Hellas und Rom, eine Culturgeschichte des

classischen Alterthums. W. Spemann, Stuttgart, 1878. Published in English as Greece and Rome,

their life and art, translated by William Hand Browne. Henry Holt and Co., New York, 1886. |

| |

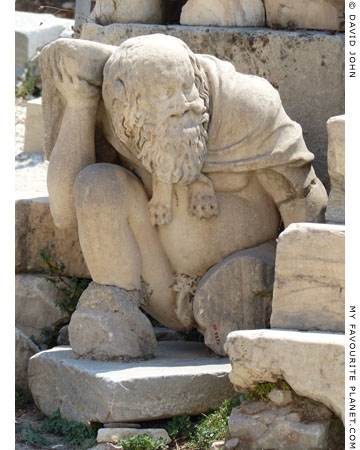

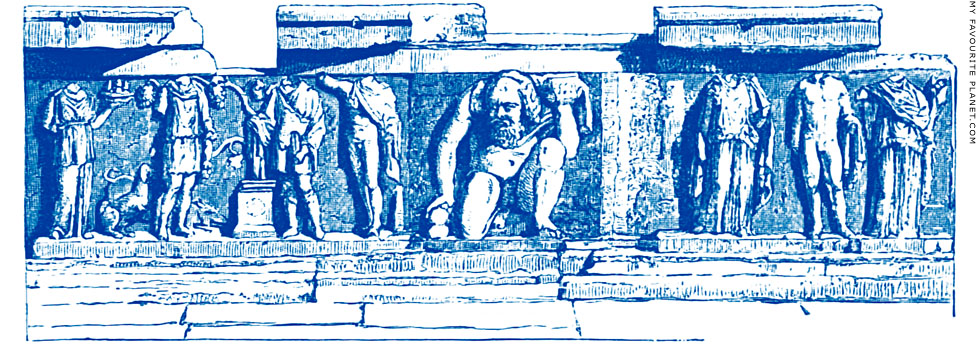

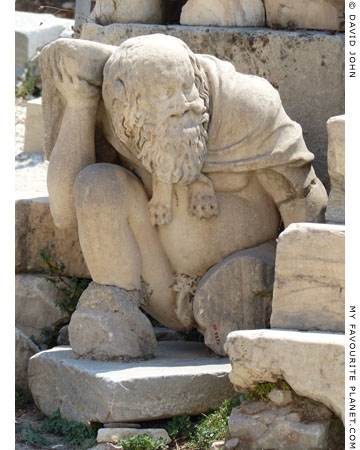

The surviving western part of the "Phaidros Bema", the late Roman period

proskenion of the Theatre of Dionysos, with a hyposkenion decorated with

reliefs depicting episodes from the life of Dionysus, and two statues of Silens. |

| |

The hyposkenion (ὑποσκήνιον, below the stage) was the area beneath the proskenion (προσκήνιον), the wooden and later stone platform in front of the skene (stage building) of Greek and Roman theatres. Its front was often featured columns, pillars or walls and was decorated with reliefs or statues. Larger stages even had doorways beneath for entrances and exits by the performers.

The late Roman period proskenion of the Theatre of Dionysos ran along the south side of the orchestra, that is behind it from the audience's point of view. Only part of the west side has survived, with four marble steps steps leading up from the orchestra to what was the centre of the stage, and a hyposkenion decorated with four reliefs and two statues of Silens. The stage is known as the "Phaidros Bema" (or "Bema of Phaidros") due to an inscription with a metrical dedication at the top of the steps, claiming that it was built by the archon Phaidros (Φαῖδρος), son of Zoilos [11].

σοὶ τόδε καλὸν ἔτευξε, φιλόργιε, βῆμα θεήτρου

Φαῖδρος Ζωίλου βιοδώτορος Ἀτθίδος ἀρχός.

For you, lover of the sacred rites, this beautiful stage has been built

by Phaidros, son of Zoilos, archon of life-giving Athens.

Inscription IG II 2 5021 (ICG 1877, 2015).

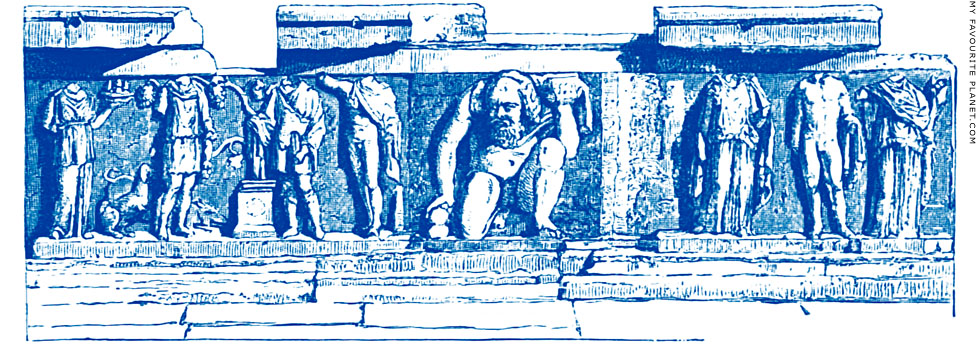

The dates of the inscription and the proskenion are still a matter of debate, with theories ranging from around the mid 4th to early 5th century AD [12]. It has been suggested that during this late period in the theatre's existence the stage was used by orators to practise their "glib and oily art". The quality of workmanship of the stage has been described as "inferior", and the poetry of the inscription "labored archaizing" and "clumsy". The reliefs below it, however, are accomplished and original, and the two statues of Silens are quite charming. The sculptures are thought to have been made in the 2nd century AD, perhaps during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD), and to have been taken from an earlier monument, which may have also been in the sanctuary.

The four surviving reliefs, on separate marble panels, depict episodes from the life of Dionysus. The now missing heads of the figures had been cut off and affixed to the cornices beneath the floor of the stage, presumably so that the panels fitted to give the platform the required height. The reliefs, from left (east) to right in photo above, depict:

1. The birth of Dionysus. Present height 78 cm, width 188 cm.

2. The entrance of Dionysus into Attica. Present height 78 cm, width 176 cm.

3. The sacred marriage of Dionysus and the Basilinna (wife of archon Basileus).

Present height 76-78 cm, width 178.5 cm.

4. The Enthronement of Dionysus. Present height 70-80 cm, width 181 cm. [13]

All the relief slabs are between 24.5 and 26 cm thick.

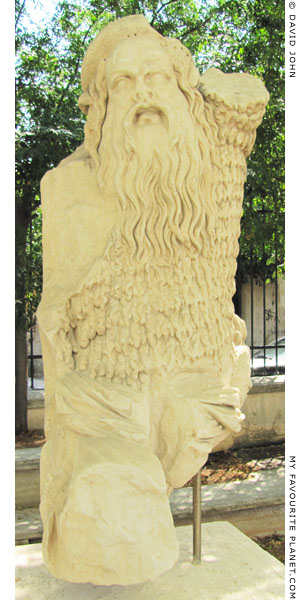

On the left (east) end of the bema, to the left of the steps which were originally at the centre of the stage, and between reliefs 2 and 3 are the two statues (or high reliefs) of Silens. Each of the bearded figures is naked apart from an animal skin around his shoulders with the beast's forelegs tied beneath his throat. They kneel on one knee and support the weight of the stage floor with their shoulders and one raised hand, which is covered by part of the animal skin to facilitate the task.

The bald Silen on the left (photo, above right) is obviously smiling, and appears jolly, despite or perhaps because of his burden. As companions of Dionysus, Silens and Satyrs are often shown literally playing a "supporting role" in depictions of the wine god in such an state of drunkenness that he has to be prevented from falling down by one or more of them (see images on the Dionysus page of the MFP People section). It was part of their job, a sacred task and function. The pose is also an echo of the depictions of Atlas and Herakles supporting the Heavens, or of the architectural figures of Telamons (or Atlantes), such as those at the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Agrigento. |

|

The Silen statue on the left (east) end

of the "Phaidros Bema". Height 92 cm.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

Inv. No. NK 5297. |

|

| |

Reliefs 2 and 3 on the hyposkenion of the Theatre of Dionysos,

with a statue of a crouching Silen (height 92 cm) between them. |

| |

A 19th century drawing of the hyposkenion reliefs by Ernst Ziller (1837-1923).

Source: Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach den Berichten

der Alten und den neusten Erforschungen, Fig. 118, page 255.

Julius Springer, Berlin, 1888. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

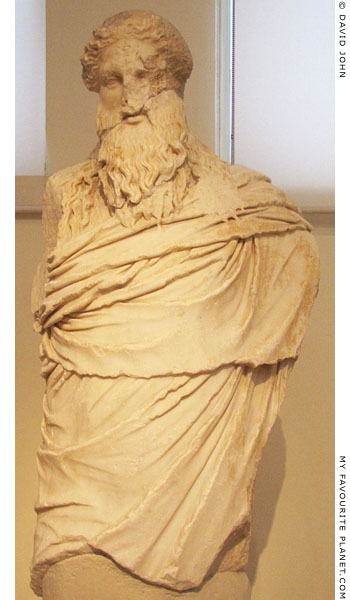

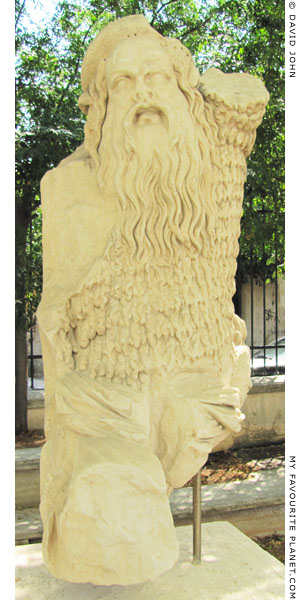

A marble statue of Papposilenos wearing

a hairy sheepskin garment, from the

Roman period skene (stage building)

of the Theatre of Dionysos.

1st or 2nd century AD.

Height 150 cm, width 63 cm.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

Inv. No. NK 2295. |

|

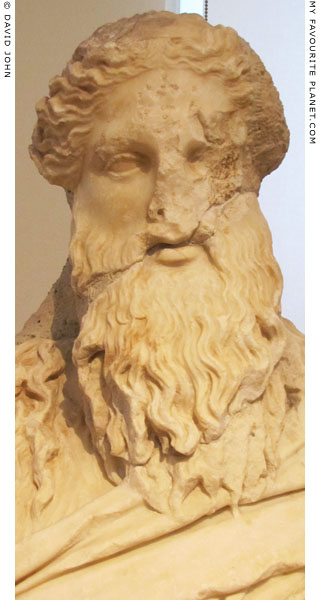

Colossal marble statue of a naked

Papposilenos, probably in the pose of Atlas.

From the Roman period skene (stage

building) of the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

1st or 2nd century AD.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

Inv. No. NK 2302. |

|

| |

Two of several surviving fragmentary statues of Papposilenos from the Theatre of Dionysos, now displayed in a small open-air area between the entrance to the archaeological site of the South Slope of Acropolis and the theatre, in which other ancient inscriptions, statues and architectural parts are exhibited (see the base of a statue of Thespis below).

The statue on the left (NK 2295) was found at the left end of the "Phaidros Bema", between one of the crouching Silen statues (see above) and steps up to the stage.

Silenos (Σειληνός, Seilenos; Latin, Silenus), was the oldest of the Silens, the tutor of Dionysus, in whose cult Greek theatre developed. He led the god's thiasos (retinue), which included Pan, Maenads, Satyrs and Silens. He is also referred to as Papposilenos (Παπποσειληνός, Father Silenos), particularly in the context of the theatre.

Pausanias noticed a stone near the Propylaia of the Acropolis, on which according to legend, Silenos rested when he came with Dionysus to Attica. As confused as most of us about the origin of Silens and Satyrs, the travel writer made some enquiries into the subject:

"There is also a smallish stone, just large enough to serve as a seat to a little man. On it legend says Silenus rested when Dionysus came to the land. The oldest of the Satyrs they call Sileni.

Wishing to know better than most people who the Satyrs are, I have inquired from many about this very point. Euphemus the Carian said that on a voyage to Italy he was driven out of his course by winds and was carried into the outer sea, beyond the course of seamen.

He affirmed that there were many uninhabited islands, while in others lived wild men. The sailors did not wish to put in at the latter, because, having put in before, they had some experience of the inhabitants, but on this occasion they had no choice in the matter.

The islands were called Satyrides by the sailors, and the inhabitants were red haired, and had upon their flanks tails not much smaller than those of horses. As soon as they caught sight of their visitors, they ran down to the ship without uttering a cry and assaulted the women in the ship. At last the sailors in fear cast a foreign woman on to the island. Her the Satyrs outraged not only in the usual way, but also in a most shocking manner."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, sections 5-6. At Perseus Digital Library.

See more images of statues of Papposilenos from Greek and Roman

theatres on the Dionysus page in the MFP People section. |

|

| |

A cylindrical marble altar from the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos, with four

reliefs of masks of silens around the side. A continuous garland of ivy and fruit

rests on each mask, then hangs beneath rosettes between the masks.

Late 2nd century BC. Height 123 cm.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 292.

|

The inscription on the altar states that it was dedicated by the brothers Pistokrates and Apollodoros, who as young men were pompostoloi, conductors of the procession in the City Dionysia festival, and were later appointed as archons.

Πιστοκράτης καὶ Ἀπολλόδωρος

Σατύρου Αὐρίδαι πομποστολήσαντες

καὶ ἄρχοντες γενόμενοι τοῦ γένους

τοῦ Βακχιαδῶν vvv ἀνέθηκαν.

Pistokrates and Apollodoros, sons of Satyros of the deme of

Auridai, and of the race of the Bacchiades, while they were

conductors of the procession and archons, dedicated it.

Inscription IG II 2 2949

The location of the small Attic Deme Auridai (Αὐρίδαι), which belonged to the Hippothontis tribe (Ἱπποθωντὶς φυλή), is unknown. For discussion of the inscription, its dating and the "race" or "genos" Bacchiades (Βακχιάδαι), see:

S. D. Lambert, The Attic "Genos" Bakchiadai and the City Dionysia. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Band 47, Heft 4 (4th Quarter, 1998), pages 394-403. At academia.edu. |

|

| |

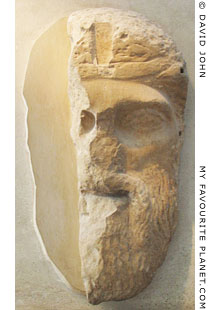

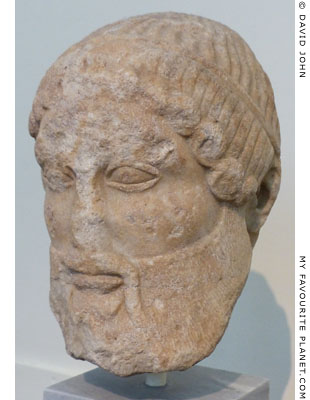

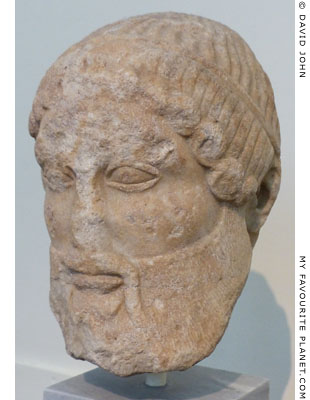

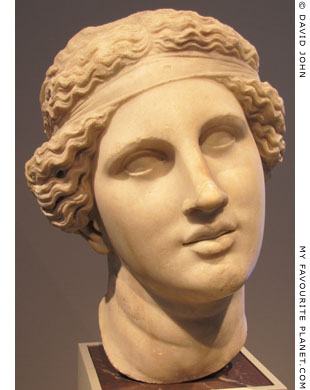

Head of mature, bearded Dionysus.

Parian marble. Early Archaistic work,

circa 480-470 BC. Found south of

the Acropolis, Athens.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 96. |

|

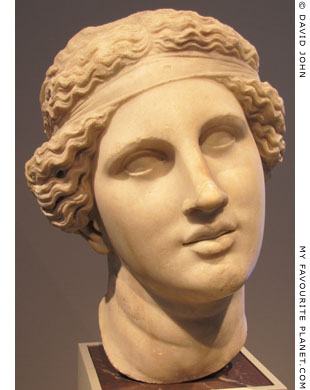

Marble head of a statue of a

singing or talking Dionysus,

wearing a mitra headband.

Roman period, after a Greek original

from 270-250 BC. Height 41 cm,

width 29.8 cm, depth 36.2 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 610.

Purchased for the museum by Gustav

Friedrich Waagen in 1842 from the

Riccardi Collection, Florence.

This is one of several ancient copies, of

which the "Head from the South Slope"

of the Acropolis is considered the most

excellent. The model may have been a

famous Hellenistic statue by Skopas in

the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos.

The almost identical "Head from the South

Slope", of Pentelic marble and dated 325-

300 BC, is in the National Archaeological

Museum, Athens (Inv. No. 182), where it

is labelled as "either Ariadne or Dionysos". |

|

| |

|

|

|

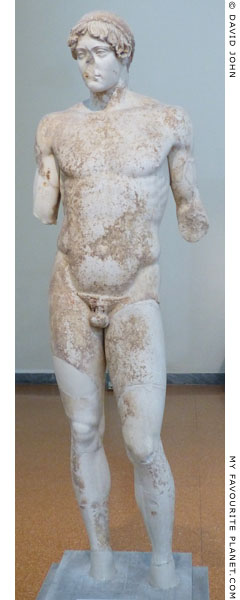

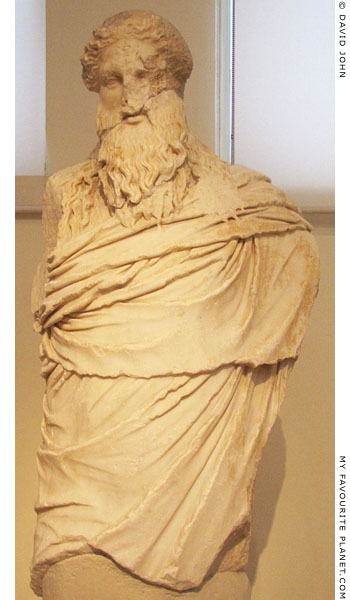

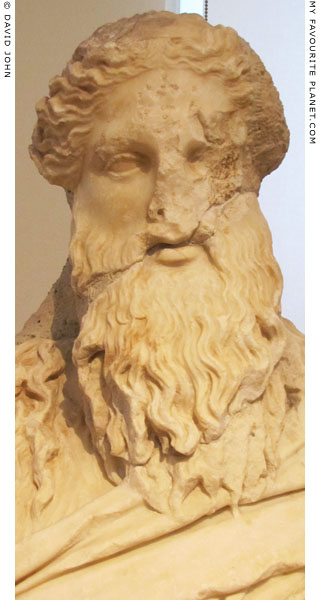

Marble statue of the "Dionysos-Sardanapalos" type from the Theatre of Dionysos.

As with other statues of this type, Dionysus is depicted with a long wavy

beard and tresses, and wrapped in a chiton (tunic) and a himation (cloak).

1st century AD, "after a Praxitelean original, circa 325-300 BC". Restored

1918-1920 from several fragments found separately between 1865 and

after 1891 at the Theatre of Dionysos. Pentelic marble. Height 123 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1656. |

|

| |

Dionysus and a female figure sitting together.

Detail of an Attic black-figure ceramic plate, made in Athens

around 575-525 BC. Found at Marathon, Attica. Diameter 19 cm.

Dionysus, holding a rhyton (drinking horn), sits on a folding stool opposite

a woman holding a flower, who sits on a block or rocks. She may be his

mother Semele, Ariadne or one of the god's other consorts.

Antikensammlung SMB, Berlin. Inv. No. F 1809. |

| |

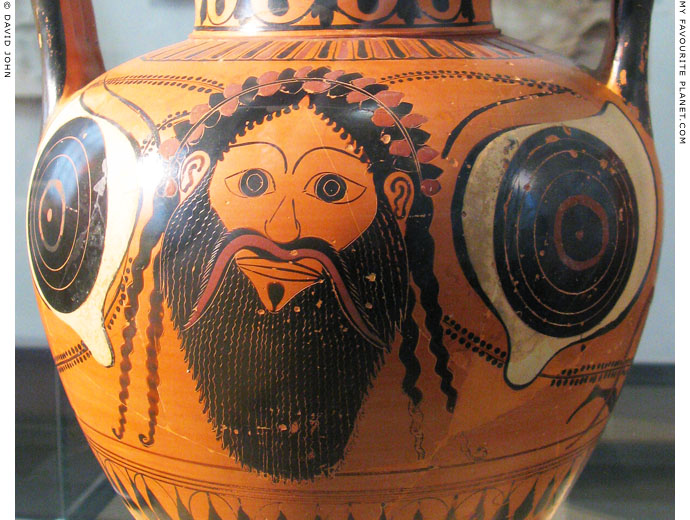

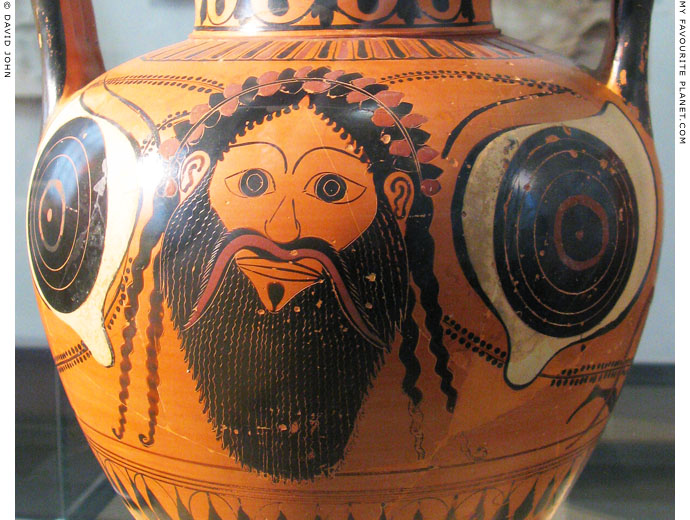

Dionysus mask between two large eyes on an Attic black-figure neck amphora.

Made in Athens around 520 BC, Archaic period. Attributed to the Antimenes Painter.

The other side (Side B) shows a similar mask of a satyr between two large eyes.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. F3997.

Acquired in 1884 from the Castellani Collection. |

| |

Dionysus, holding a rhyton (drinking horn) and an ivy branch, with two ecstatic dancing maenads.

An Attic red-figure stamnos by the Syleus Painter, 480-470 BC. From Tarquinia, Etruria, Italy.

Dionysus, with long beard and locks wears a crown of ivy leaves, and a himation over a long

chiton. He walks to the right, looking to the left, carrying an ivy branch in his left hand and

a rhyton in his right. Both dancing maenads hold krotala (κρόταλα, clappers) in each hand.

The other side (Side A) shows the Judgement of Paris: Paris seated on a rock, Hermes

and Aphrodite with a sceptre and bird; a snake, a deer and a hedgehog on rock.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. F2182.

See: Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 202509 |

| |

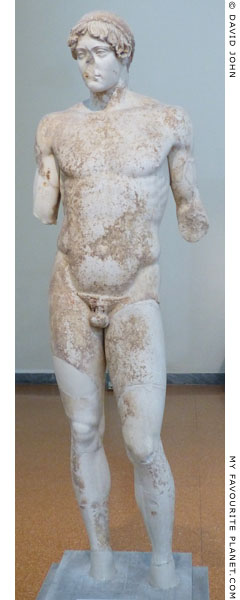

The "Omphalos Apollo" statue, found

in 1862 at the Theatre of Dionysos.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD.

Named after an omphalos-shaped

base with which it was once

associated. Height 176 cm.

For further information, see Antinous

in the MFP People section.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 45. |

| |

Inscribed base of a statue of the tragic poet Thespis (Θέσπις, 6th century BC).

2nd century AD.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 282. Inscription IG II 2 4264.

|

This statue base is displayed in a small open-air area between the entrance to the archaeological site of the South Slope of Acropolis and the Theatre of Dionysos, in which other ancient inscriptions, statues and architectural parts are exhibited. See the statues of Papposilenos above.

According to ancient sources, Thespis was from the deme of Ikaria (Ἰκάρια, today Dionysos, Διόνυσος), in northeastern Attica, where winemaking was first introduced to Attica by Dionysus (see Dionysus in the MFP People section). He was said to have written several tragic plays, and to have been the first actor, that is the first person to perform as a character in a drama, rather than merely telling a story through narration, singing or dancing. He also toured, travelling in a cart with other actors.

"Thespis is said to have invented a new kind of tragedy, and to have carried his pieces about in carts, which [certain strollers], who had their faces besmeared with lees of wine, sang and acted. After him Aeschylus, the inventor of the vizard mask and decent robe, laid the stage over with boards of a tolerable size, and taught to speak in lofty tone, and strut in the buskin. To these succeeded the old comedy, not without considerable praise: but its personal freedom degenerated into excess and violence, worthy to be regulated by law; a law was made accordingly, and the chorus, the right of abusing being taken away, disgracefully became silent."

Q. Horatius Flaccus (Horace), The art of poetry: To the Pisos, line 275 onwards. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

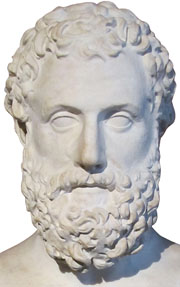

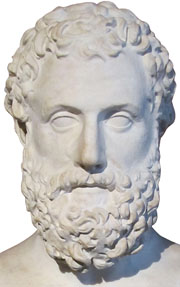

Marble Portrait bust of the

Athenian tragedian Aeschylos

(Αἰσχύλος, circa 525-456 BC).

Roman period copy of a

4th century BC Greek original.

Neues Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 313.

See also article on

Stageira gallery page 19. |

|

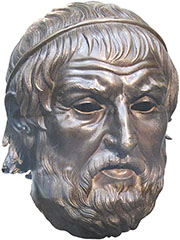

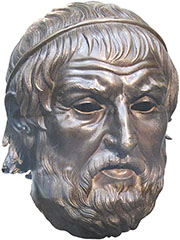

Bronze and copper portrait head,

known as "the Arundel Head",

thought to depict the Athenian playwright Sophokles (Σοφοκλῆς,

circa 496-406 BC). Originally part

of a statue, 300-100 BC, probably

from Smyrna (today Izmir). [14]

British Museum, London.

Inv. No. 1760,0919.1 (Bronze 847).

Photos: © David John |

|

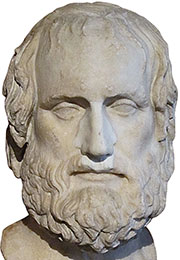

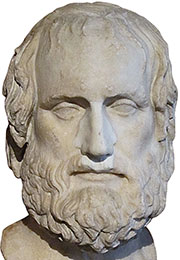

Marble Portrait bust of the

Athenian tragedian Euripides

(Εὐριπίδης, circa 480-406 BC).

Roman copy of a 4th century BC

Greek original. One of over 30

known copies of the "Farnese

type". From Cumae, Italy.

Height 3.2 cm.

Neues Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 297. Purchased 1864

in Naples by Wolfgang Helbig.

See also photo below. |

|

| |

Inscribed marble relief in honour of the Athenian playwright Euripides.

From the vicinity of Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey). Late Hellenistic era.

1st century BC - 1st century AD. Height 60 cm, width 68.5 cm.

The tragedian (centre), seated and holding a scroll in his left hand, hands an actor's mask

of Herakles to Skene, the young female personification of the theatre (left), while an

Archaic statue of Dionysus (right) looks on, holding a kantharos in his right hand.

Gustave Mendel suggested that the relief should be called "the Apotheosis of Euripides"

because of the similarity of subject and treatment to the "Apotheosis of Homer" relief.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1242 T. Cat. Mendel 574.

Purchased from the Misthos antiquities collection in Smyrna; taken to Istanbul in 1900. |

| |

A scene from an Attic comedy on a red-figure calyx krater

made in Poseidonia (Paestum, Campania, Italy).

The vase painting depicts a phlyax play, with actors in Attic comedy costume,

performed on a wooden stage supported by columns. Two thieves try to drag

a miser off his treasure chest, while a frightened slave (right) looks on.

The other side of the krater shows Dionysus and a satyr.

Atributed to the Painter Assteas, around 350 BC. From Nola, Italy.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. F 3044. Acquired in 1875. |

| |

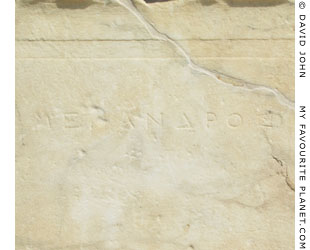

Reconstructed statue of Menander (Μένανδρος, circa 342-290 BC), Athenian

playwright of the New Comedy, in front of the parados (retaining wall) of the

auditorium at the east side of the Theatre of Dionysos.

|

Although the statue's pedestal, inscribed with Menander's name, is original (291/290 BC; excavated in 1862), the statue itself is one of a number of modern composite plaster cast reconstructions made by Klaus Fittschen for the University Collection of the Archaeological Institute of Göttingen, Germany (Inv. No. A 1497a). The original torso is in Naples and the head in Venice. Another copy, also made in Göttingen (completed 2009), can be seen in the Abguss-Sammlung (cast collection) of Marburg University.

The inscribed statue base (see photo right) is signed by the sculptors Kephisodotos the Younger and Timarchos, believed to have been brothers and the sons of Praxiteles. The original bronze statue is thought to have been the portrait mentioned by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, section 1), and said to have been made shortly after Menander drowned while swimming at Piraeus. He wrote over 100 plays, many of which remained popular into the Roman period. It is thought that the many statues of the poet, of which more than 70 have survived, were copied from this original. [15]

"In the theatre the Athenians have portrait statues of poets, both tragic and comic, but they are mostly of undistinguished persons. With the exception of Menander no poet of comedy represented here won a reputation, but tragedy has two illustrious representatives, Euripides and Sophocles.

There is a legend that after the death of Sophocles the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] invaded Attica, and their commander saw in a vision Dionysus, who bade him honour, with all the customary honours of the dead, the new Siren. He interpreted the dream as referring to Sophocles and his poetry, and down to the present day men are wont to liken to a Siren whatever is charming in both poetry and prose.

The likeness of Aeschylus is, I think, much later than his death and than the painting which depicts the action at Marathon. Aeschylus himself said that when a youth he slept while watching grapes in a field, and that Dionysus appeared and bade him write tragedy. When day came, in obedience to the vision, he made an attempt and hereafter found composing quite easy."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, sections 1-2.

See also two mosaics by Dioskourides of Samos, found

in Pompeii, showing scenes from plays by Menander. |

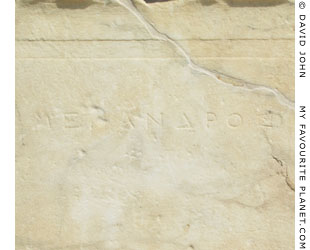

Menander's name inscribed on the statue

base. The signatures of the artists below

it are worn and almost invisible.

Μένανδρος

Κηφισόδοτος Τίμαρχος ἐπόησαν

Menandros

Kephisodotos and Timarchos made it

Inscription IG II² 3775. |

| |

Marble portrait head of Menander from Corfu.

Roman Imperial period, first half of

the 2nd century AD. One of the best

preserved copies of the bronze

statue from the Theatre of Dionysos.

Height 29.5 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 133. |

| |

| |

Inscribed marble base of a statue of the musician Nikokles Aristokleos (Νικοκλῆς Ἀριστοκλέους,

Nikokles son of Aristokles), thought to be the famous kithara player Nikokles from Tarentum

(Νικοκλέους Ταραντίνου) mentioned by Pausanias. The names of the festivals in which he won

musical contests are written in relief wreaths on three sides of the base. Mid 3rd century BC.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 287.

|

The inscriptions and wreaths on all three sides of the base are now very faint, but have been deciphered by patient examination:

Left side:

[․․]ίεια.

Ἑκατόμβοια.

Ἴσθμια

πρῶτος.

Βασίλεια

ἐν Μακεδονίαι. |

Front:

Νικοκλῆς | Ἀριστοκλέους

Πύθια.

Πύθια.

Πύθια.

Παναθήναια

τὰ μεγάλα.

Λήναια

διθυράμβωι.

Πύθια.

Πύθια.

Πύθια. |

Right side:

Βασίλεια

ἐν Ἀλεξανδρείαι.

Ἡλίεια.

Βασίλεια.

Ἀσκληπιεῖα. |

Inscription IG II 2 3779

The victories of Nikokles:

Left side: the [...]leia; the Hekatomboia; Isthmia; the Basileia of Macedon.

Front: Nikokles son of Aristokles. Three victories at the Pythia in Delphi; the Great Panathenaia in Athens; the Lenaia (a festival of Dionysus in Athens), with a dithyramb; another three at the Pythia.

Right side: the Basileia of Alexandria; Ileia; Basileia; Asklepieia.

The inscription does not mention the discipline for which he won these contests, but such a famous musician would have been known to those who saw the statue, which may have depicted him playing his instrument and/or singing. It is thought that he was probably a kitharodos (κιθαρῳδός), a singer who accompanied himself on the kithara.

Pausanias mentioned the tomb of Nikokles from Tarentum (Νικοκλέους Ταραντίνου), a famous kitharodos, at Lakiadai (Λακιάδαι), just outside Athens on the road to Eleusis (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 37, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library). |

|

| |

Inscribed marble base of a statue of the poet Diomedes,

signed by the sculptor Demetrios Pteleasios.

2nd century BC. Found at the Theatre of Dionysos 1862.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 273.

|

Διομήδης.

Δημήτριος Πτελεάσιος

ἐποίησεν.

Diomedes. Demetrios Pteleasios made it.

Inscription IG II 2 4257

The sculptor Demetrios Pteleasios may be the Demetrios Philonos Pteleasios (Δημήτριος Φίλωνος Πτελεάσιος, Demetrios son of Philon, from Ptelea) known from signatures on other statue bases, including one found near the Eleusinion, south of the Athenian Agora.

Nothing is known about Diomedes, but he is thought to have been a playwright of the New Comedy, and may have been the same poet recorded in an inscription as taking part in the Rhomaia festival in Magnesia on the Maeander (Asia Minor), where he is mentioned as Diomedes Athenodorou from Pergamon (Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρου Περγαμηνός). A Diomedes is also honoured on other inscriptions: a statue base from Epidauros, hounouring the comic poet Diomedes Athenodorou of Athens (Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρου Ἀθηναῖον, ποιητὰν [κ]ωμῳδιῶν); Diomedes Athenodoro[u] (Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρο[υ]) appears in a list of participants in the Pythian festival in Delphi. [16] |

|

A drawing of the inscription on the

Diomedes base by the Greek archaeologist

Athanasios Rhousopoulos (Αθανάσιος

Ρουσόπουλος, 1823-1898).

Source: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1862,

page 224 and plate 32, fig. 3. Εν Αθήναις

Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike

Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological

Society of Athens). Athens, 1863. At

Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

The lower part of a marble double-headed herm, found in

1914 in the area of the Odeion of Pericles, during excavations

directed by Greek archaeologist Panagiotes G. Kastriotes.

The front is bisected by a vertical incised line, to the left of which

is a relief of a hydria (or stamnos), and to the right a kerykeion

(caduceus). It has been suggested that the herm may have been

a boundary marker between the Sanctuary of Dionysus Eleuthereos

and an unknown sanctuary of Hermes.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 2342. |

| |

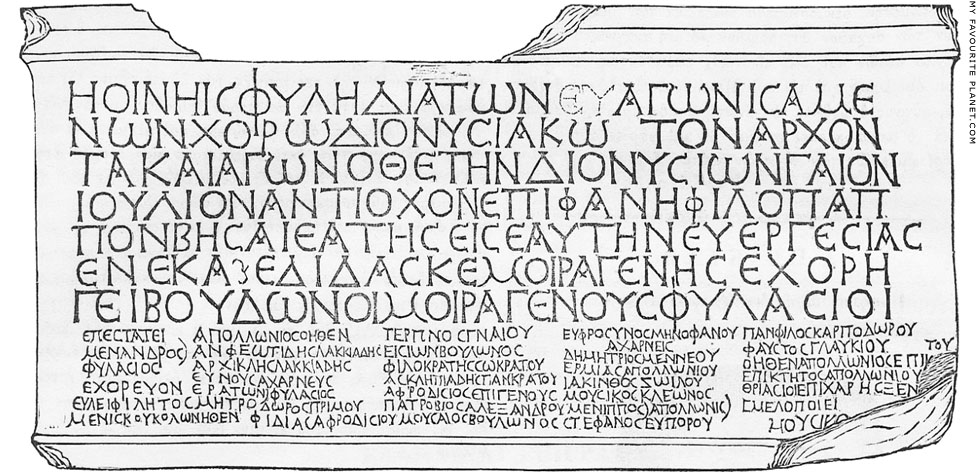

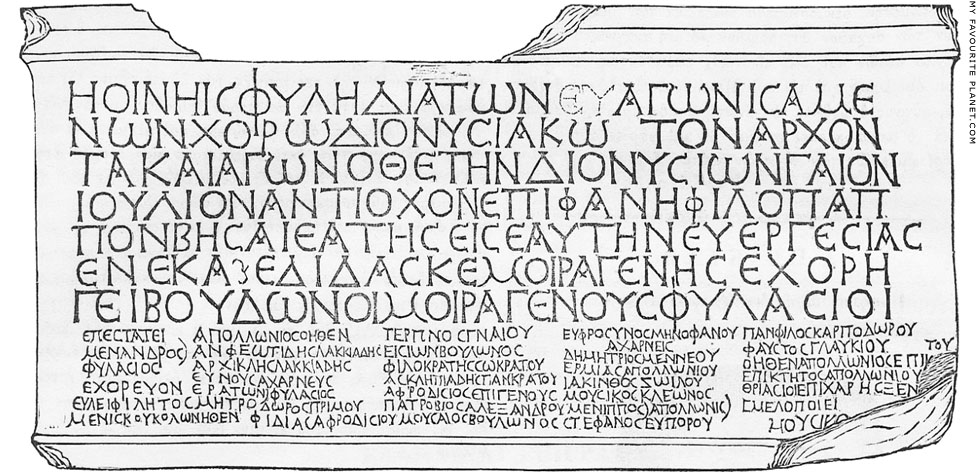

A marble statue base with a choregic inscription, dedicated by the Attic phyle (tribe)

Oinis to honour the archon Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos, and

mentioning the factors of a performance staged at the Dionysia. 75/76 - 87/88 AD.

Found at the Theatre of Dionysos on 20 July 1862.

Theatre of Dionysos, Athens. Inv. No. NK 280. Inscription IG II (2) 3112.

|

Philopappos (Γαίος Ιούλιος Αντίοχος Επιφανής Φιλόπαππος, 65-116 AD), a Greek prince of the Kingdom of Commagene, Syria, is known from his marble tomb monument, the Philopappos Monument, on Mouseion Hill (λόφος Μουσών, also known as the Hill of the Muses, and in modern Greek as Philopappos Hill, Λόφος Φιλοπάππου), southwest of the Acropolis.

He was the grandson of Antiochos IV Epiphanes (Γάιος Ἰούλιος Ἀντίοχος ὀ Ἐπιφανής, before 17 - after 72 AD, reigned 38-72 AD), the last king of Commagene, a client of Rome. Suspecting a planned rebellion, Emperor Vespasian deposed Antiochos in 72 AD and Commagene was absorbed into the Roman province of Syria. However, Vespasian forgave Antiochos, and his family moved to Rome where they became wealthy and respected Roman citizens.

During the reign of Trajan (98-117 AD), Philopappos became a member of the Praetorian Guard, a senator and in 109 AD served as suffect consul. At some point he moved to Athens, where he lived for the rest of his life, acquiring Athenian citizenship as a member of the Besa (Βησα) phyle. He served as an archon, an agonothetes (magistrate of games) and choregos. He was acquainted with several prominent Greeks, including Plutarch.

Philopappos' younger sister Julia Balbilla (Ἰουλία Βαλβίλλα, 72 - after 130 AD) became a poet at the court of Emperor Hadrian.

The inscription (see image below) states that the Oinis (Οἰνηὶς) phyle honoured the archon and agonothetes Philopappos of the Besa phyle for directing a winning chorus during the Dionysia festival, and for his deeds as benefactor (Εὐεργέτης). The chorus was rehearsed by Moiragenes (Μοιραγένης), and the choregos was Boulon, son of Moiragenes (Βούλων οἱ Μοιραγένους).

The Greek text of the inscription:

epigraphy.packhum.org/text/5375 at the Packard Humanities Institute. |

|

The remains of the Philopappos Monument,

viewed from the South Slope of the Acropolis. |

|

| |

A drawing of the inscription on the Philopappos base by the Greek archaeologist

Kyriakos S. Pittakis (Κυριάκος Πιττάκης, 1798-1863, see gallery page 12).

Source: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1862, pages (columns) 221-224 and plate 32, fig. 1.

Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological

Society of Athens). Athens, 1863. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Theatre of

Dionysos |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Dionysus or Dionysos

On this page I have used the usual English spelling for Dionysus, except where the name is used in a quotation or as a title such as Theatre of Dionysos or Sanctuary of Dionysos.

The tradition of using Latinized versions of ancient Greek names seems very outdated, but attempting to correct every instance (Akropolis for Acropolis, Attalos for Attalus, Korinth for Corinth, Perikles for Pericles, etc) can lead to all kinds of complications and muddles. |

|

|

2. Coin showing a plan of the Theatre

The bronze coin is inscribed "ΑΘΗΝ-ΑΙΩΝ", of (the people of) Athens. The obverse side (front) shows the head of Athena in profile, facing right, wearing a crested Corinthian helmet. It was collected by Louis François Sébastien Fauvel (1753-1838), the French consul and antiquarian who lived in Athens 1803-1822. It was later given by Lord Aberdeen to Richard Payne Knight (1750-1824), who left it in his will to the British Museum, where it it is now part of the Payne-Knight collection.

Copper alloy coin.

Weight: 4.361 grams

Die-axis 6 o'clock

Diameter 21 mm

Museum No.: RPK,p36L.7.Ath

The coin is not on display in the museum.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, page 85. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Illustrations of this coin appeared in several books by early modern travellers to Greece, including opposite the title page to William Martin Leake's Topography of Athens:

William Martin Leake (1777-1860), The topography of Athens, with some remarks on its antiquities. John Murray, London, 1821. At the Internet Archive.

A description of the medal from a British Museum coin catalogue of 1888:

"Number 807. Head of Athena right, wearing crested Corinthian helmet.

Theatre of Dionysos immediately surmounted by the Choragic monument of Thrasyllus, behind which rises the southern wall of the Acropolis, on the summit of which are on the left the Propylaea, in the centre the Parthenon, and on the right a third building."

Barclay V. Head, A Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum: Attica, Megaris, Aegina, page 110; Plate XIX, 8. Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1888.

Six coins of this type, found during excavations in the Athenian Agora, were catalogued by John H. Kroll and Alan S. Walker, and described as:

"Theater of Dionysos, seen from south; above, at center, Parthenon; at left, possibly the Chalkotheke or Propylaia; at right of Parthenon, round temple of Roma and Augustus; border of dots."

John H. Kroll (with contributions by Alan S. Walker), The Athenian Agora XXVI: The Greek coins, catalogue No. 375, page 159. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), Princeton, New Jersey, 1993. PDF at ascsa.edu.gr.

Another coin of this type is in the Harvard Art Museums.

Inv. No. 2002.282.2. See photos and details at:

harvardartmuseums.org/art/97279 |

|

The Acropolis and the Theatre of Dionysos

depicted on an Athenian bronze coin.

Around 264-267 AD, late Roman period.

British Museum, London. |

|

3. The audience capacity of ancient theatres

See, for example: Stamatia Eleftheratou (editor), Acropolis Museum guide, page 68. Acropolis Museum Editions, Athens, 2014.

Since the late 18th century architects and scholars, including William Martin Leake, have attempted to estimate the seating areas and audience capacities of ancient theatres using mathematical formulae and other methods. The resulting estimates often vary considerably. Roughly, a width of 50 centimetres is allowed for each of the "bums on seats".

4. Naumachiae

Mentions by ancient authors of naumachiae held in arenas such as the Colosseum have long been disputed by modern scholars, often on technical grounds. Many have considered the difficulties of supplying sufficient water for such spectacles and of the capacity of such theatres and arenas to support and retain such a mass, as well as the problems of the presentation of two or more ships in battle. Recent research appears to confirm that such mock sea battles could have been staged in the Colosseum and elsewhere. Still, the chorus of the Athens theatre could never have been large or deep enough for anything but a mini-naumachia.

5. The invisible theatre

See: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, plate XXXVIII. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The first edition of Volume II, was published after Stuart's death in 1788. Although it is dated "1787", in the preface written by his widow Elizabeth Stuart she refers to "my late husband". It was edited by William Newton (1735-1790), an architect who had worked with Stuart on the design of the Greenwich Infirmary, and who wrote the first English translaion of the Ten books on architecture by Virtuvius. Newton was assisted and advised by members of the Society of Dilettanti, and the second edition, published in 1825, contains more copious notes, some politely pointing to Stuart's errors and further discoveries made since he had been in Greece, such as the location of the theatre. The influence of Richard Chandler, William Martin Leake and Charles Robert Cockerell can be seen in these amendments.

6. Rediscovery of the Theatre by Chandler

"The hill, near this end [of the Acropolis], is idented with the site of the theatre of Bacchus, by which is a solitary church or two... Some stone-work remains at the two extremities, but the area is ploughed, and produces grain."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, Chapter 12, pages 61-64. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

Despite his intelligent efforts to locate ancient monuments in Greece, he sometimes confused references by ancient authors and made several errors. He believed, for example, that the Odeion of Herodes Atticus was the Odeion of Pericles (pages 64-65).

William Martin Leake (1777-1860), The topography of Athens, with some remarks on its antiquities, pages 25-29. J. Murray, London, 1821. At the Internet Archive.

Leake expanded his description of the Theatre of Dionysos and acknowledged Chandler's discovery in the second edition of the The topography of Athens:

"Chandler was the first who gave his opinion that these remains belonged to the theatre of Bacchus. Barthélemy followed him in the Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis *, where, speaking of the choragic monuments found in the vicinity of this theatre, he justly remarks, 'Il convenait que les trophées fussent élevées auprès du champ de bataille.' Jeune Anach. II. 12. But some later authors have still adhered to the opinion of Stuart." Page 184, note 3.

Leake also expressed surprise at James Stuart mistaking the remains of the theatre for the Odeion of Pericles, and the Odeion of Herodes Atticus for the theatre. Stuart may have been aware that what we now know to be the Odeion of Herodes Atticus was a Roman building, but presumed that the Theatre of Dionysos had been rebuilt during the Roman period, which is also now known to be the case.

"The Dionysiac theatre, or theatre of Bacchus, is another point of Athenian topography upon which there can be no doubt, and its position is of such consequence, that a mistake in regard to it led Stuart to several erroneous conclusions on the topography of the city. He supposed that the theatre, the ruins of which are seen under the south-western corner of the Acropolis, was the Dionysiac theatre, and that the building, of which the form only, together with some vestiges of one of the wings, are traced near the south-eastern angle, was the Odeium of Pericles; in which opinion, one is surprised he should have imagined that a building, so entirely of the construction of Roman times as the former, could have been the theatre where the works of Aeschylus and his followers in the drama were first represented, and equally so that he should have conceived that so large an edifice as the latter could ever have been covered by a pointed wooden roof, such as that of the tent-shaped building of Pericles." Pages 183-184.

William Martin Leake, The topography of Athens and the Demi, Volume I: The topography of Athens (The topography of Athens, second edition), Section II, pages 183-188, and Appendix XII, On the capacity of the Dionysiac Theatre, pages 520-

J. Rodwell, London, 1841. At the Internet Archive.

* Jean Jacques Barthélemy (French Jesuit classical scholar, 1716-1795), Voyage du jeune Anacharsis en Grèce, dans le milieu du quatrième siècle avant l'ère vulgaire. Published in 4 volumes by De Bure, l'ainé, Paris, 1788. A fictional story of the journey of a descendant of the 6th century BC Scythian philosopher Anacharsis who travelled from Scythia, on the Black Sea, to Athens.

7. The xoanon of Dionysos Eleuthereos

This statue is often described by modern authors as being made of wood, based on the interpretation of Pausanias' use of the word xoanon (ξόανον) as a wooden image. However, he appears to have used the word for cult images in general, often without specifying the materials from which they were made. See the note on gallery page 11. He called the copy of the statue at Eleutherae an agalma (ἄγαλμα, glory, delight, honour; thence pleasing gift, especially for the gods; used to describe a statue in honour of a god, or more generally a statue, portrait, picture or image).

During the Dionysia, the festival of Dionysus in Athens, the statue was taken in a procession to a small temple of the god near the Academy (Ἀκαδημία, i.e. Plato's Academy), northwest of Kerameikos.

"Outside the city, too, in the parishes and on the roads, the Athenians have sanctuaries of the gods, and graves of heroes and of men. The nearest is the Academy, once the property of a private individual, but in my time a gymnasium ... Then there is a small temple, into which every year on fixed days they carry the image [ἄγαλμα] of Dionysus Eleuthereus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 29, section 2.

Philostratus "the Athenian" (circa 160-249 AD) wrote that the wealthy Athenian Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes (referred to as Atticus, circa 65 - before 160 AD), father of the more famous Herodes Atticus, financed the catering for the revellers during the time of the procession:

"And whenever the festival of Dionysus came round and the image [ἕδος, seated statue of a god] of Dionysus descended to the Academy, he [Atticus] would furnish wine to drink for citizens and strangers alike, as they lay in the Cerameicus on couches of ivy leaves."

Philostratus and Eunapius, The lives of the Sophists, Philostratus, Book II, chapter 1, section 549, pages 144-145. In ancient Greek and English, translated by William Cave Wright. Loeb Classical Library. Heinemann, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1922. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

8. The Odeion of Pericles

The odeion was described briefly by Vitruvius and Plutarch, both of whom attributed its establishment to Pericles.

"Behind the scenes porticos are to be built; to which, in the case of sudden showers, the people may retreat from the theatre, and also sufficiently capacious for the rehearsals of the chorus: such are the porticos of Pompey, of Eumenes at Athens, and of the temple of Bacchus; and on the left passing from the theatre, is the Odeum, which, in Athens, Pericles ornamented with stone columns, and with the masts and yards of ships, from the Persian spoils. This was destroyed by fire in the Mithridatic war, and restored by king Ariobarzanes."

Vitruvius, de Architectura, Book 5, chapter 9, section 1. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

"The Odeum, which was arranged internally with many tiers of seats and many pillars, and which had a roof made with a circular slope from a single peak, they say was an exact reproduction of the Great King's pavilion, and this too was built under the superintendence of Pericles. Wherefore Cratinus, in his Thracian Women, rails at him again:

'The squill-head Zeus! lo! here he comes,

The Odeum like a cap upon his cranium,

Now that for good and all the ostracism is o'er.'

Then first did Pericles, so fond of honour was he, get a decree passed that a musical contest be held as part of the Panathenaic festival. He himself was elected manager, and prescribed how the contestants must blow the flute, or sing, or pluck the zither. These musical contests were witnessed, both then and thereafter, in the Odeum."

Plutarch (Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), The Parallel Lives, The life of Pericles, chapter 13, sections 5-6. Loeb Classical Library edition, Vol. III, 1916. Also at LacusCurtius.

Pausanias took little notice of the building, which he referred to merely as "a structure". By the time of his stay in Athens, somewhere around 143-159 AD, it had probably been superseded by the Odeion of Agrippa (or Agrippeion), built in the Agora following Marcus Agrippa’s visit to Athens in the winter of 16/15 BC (see The Pedestal of Agrippa).

"Near the sanctuary of Dionysus and the theater is a structure, which is said to be a copy of Xerxes' tent. It has been rebuilt, for the old building was burnt by the Roman general Sulla when he took Athens."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 20, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias' mentioned the Odeion of Agrippa in Book 1, chapter 8, section 6, and chapter 14, section 1, where he wrote: "When you have entered the Odeum at Athens you meet, among other objects, a figure of Dionysus worth seeing". Shortly after he saw it, the roof collapsed. It was destroyed by fire and then dismantled in the 3rd century AD, and some of its decorative elements were used in the building of a gymnasium around 400 AD.

See:

Margaret C. Miller, Athens and Persians in the fifth century BC: A sudy in cultural receptivity. Cambridge University Press, 1997. Chapter 9 is a study of theories concerning the history the Odeion of Pericles.

Sebastian Trainor, The Odeon of Pericles: A tale of the first Athenian music hall, the second Persian invasion of Greece, theatre space in fifth century BCE Athens, and the artifacts of an empire. Theatre Symposium Volume 24 (2016), pages 21-40. University of Alabama Press, 2016. At academia.edu. |

|

|

9. The Odeion of Pericles rebuilt by Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia

According to the historian Appian of Alexandria (Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς, Appianos Alexandreus, circa 95-165 AD), the odeion was burnt down, not by Sulla as Pausanias stated (see previous note), but by Aristion (Ἀριστίων), the philosopher and tyrant of Athens who allied the city with Mithridates VI Eupator against Rome, to prevent Sulla using its timber as siege material. After taking refuge on the Acropolis, Aristion was captured by Sulla's troops and executed on 1st March 86 BC.

"A few [Athenians] had taken their feeble course to the Acropolis, among them Aristion, who had burned the Odeum, so that Sulla might not have the timber in it at hand for storming the Acropolis. Sulla forbade the burning of the city, but allowed the soldiers to plunder it."

Appian, Mithridatic Wars, chapter 6, section 38. At Perseus Digital Library.

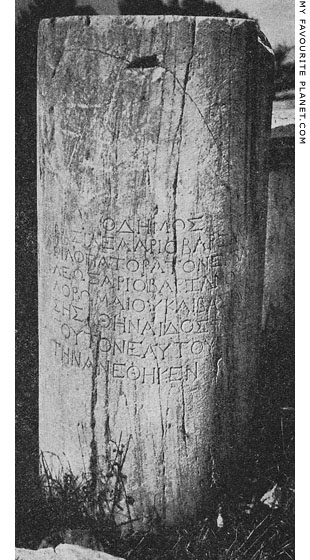

Vitruvius' claim (see previous note) that the rebuilding of the odeion was financed by Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia (Ἀριοβαρζάνης Β΄ Φιλοπάτωρ, Ariobarzanes Philopator, king of Cappadocia circa 63/62 BC - circa 52/51 BC, an ally or puppet of Rome) appears to be supported by two inscriptions from the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos, known since the 18th century. The first is an honorary dedication by the demos (city) of Athens to Ariobarzanes (see photo above and photo right), who is referred to as their euergetes (εὐεργέτης, benefactor, patron):

ὁ δῆμος

βασιλέα Ἀριοβαρζάνην

Φιλοπάτορα τὸν ἐκ βασι-

λέως Ἀριοβαρζάνου Φι-

λορωμαίου καὶ βασιλίσ-

σης Ἀθηναίδος Φιλοστόρ-

γου τὸν ἑαυτοῦ εὐεργέ-

την ἀνέθηκεν.

The demos [dedicated] to King Ariobarzanes Philopator, son of King Ariobarzanes Philoromaios and of Queen Athenais Philostorgos, its benefactor.

Inscription IG II 2 3427.

Although the inscription has been described as a being on a statue base, the label to the inscription, as displayed near the theatre in the archaeological site of the South Slope of Acropolis (Inv. No. NK 284), describes it as an "inscribed column drum of an unfluted dedicatory column". It was found built into a later wall of the skene of the theatre, but may have orginally formed part of the odeion's interior colonnade.

The attribution of the design or supervision of the building of Ariobarzanes' new odeion to Gaius and Marcus Stallius and Menalippos is based on the statue base dedicated by the three men to Ariobarzanes:

βασιλέα Ἀριοβαρζάνην Φιλοπάτορα τὸν ἐκ βασιλέως

Ἀριοβαρζάνου Φιλορωμαίου καὶ βασιλίσσης

Ἀθηναίδος Φιλοστόργου οἱ κατασταθέντες

ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ ἐπὶ τὴν τοῦ ὠιδείου κατασκευὴν

Γάιος καὶ Μᾶρκος Στάλλιοι Γαίου ὑοὶ καὶ

Μενάλιππος ἑαυτῶν εὐεργέτην.

King Ariobarzanes Philopator, son of King Ariobarzanes Philoromaios and of Queen Athenais Philostorgos, [is honored by] those commissioned by him for the construction of the Odeion, Gaius and Marcus Stallius, sons of Gaius, and Menalippos, as their benefactor.

Inscription IG II 2 3426.

Menalippos (here written as Μενάλιππος) is sometimes referred to by modern scholars as Melanippus, as the name is considered to be a misspelling of Melanippos (Μελάνιππος), the name of several mythological characters. Some of these, however, are also named as Menalippos in Greek texts.

The three men have been described as "architects", "supervisors" or "bankers", although it is not known which part any of them played in the construction of the odeion. It is usually assumed that the Stallius brothers were Roman and Menalippos a Greek.

Ariobarzanes may have been educated in Athens, as his name appears on an ephebic decree (IG II 2 1039) which lists ephebes who participated in 80/79 BC at the Sylleia (Σύλλεια), a civic festival with games in honour of Sulla. His father, known as Ariobarzanes I Philoromaios (Ἀριοβαρζάνης Α΄ Φιλορωμαίος, Ariobarzanes Friend of Rome), ruled Cappadocia from 95 BC, and having being deposed several times by Mithridates and each time regaining his throne only by Roman intervention, finally abdicated in favour of his son around 63/62 BC. Nothing is known for certain about his mother, Athenais Philostorgos I (Άθηναἷς Φιλόστοργος Α', Athenais the Loving One, or Lover of her children).

The former inscription (IG II 2 3427) was mentioned by Dr. Richard Chandler, who visited Athens in 1765-1766 (see note 1), although he provides no information about where or when it was found or its location. He also wrote that the latter inscription (IG II 2 3426) was at that time "in a stable" in Athens.

"King Ariobarzanes the second, named Philopator, who reigned in Cappadocia not long after, restored it; and in a stable is an inscription, which has belonged to a statue of him erected by the persons, whom he appointed the overseers. He was honoured also with a statue by the people, as appears from another inscription."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, page 65. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

William Martin Leake reported that a copy of the latter inscription, made in 1743 was sent to Paris. Unfortunately, he also omits further details concerning the object on which the dedication was inscribed.

"An inscription, of which a copy taken by the Consul of France in 1743, was sent to Paris, records the gratitude to Ariobarzanes of the persons who had superintended the repair of the Odeium. The prince is there surnamed Philopator, son of Ariobarzanes Philoromaeus. Hence he appears to have been the son of the prince with whom Cicero describes his interview in Cappadocia. (Cicer. Ep. ad Fam. 1. 15, ep. 2.)"

The references in Cicero of Ariobarzanes an his family: Cicero, epistulae ad familiares, 15, 2, 6; Cicero, de provinciis consularibus, 9.

William Martin Leake, The topography of Athens, with some remarks on its antiquities, page 28, note 1. J. Murray, London, 1821. At the Internet Archive.

It was first published by the French antiquarian Abbé Augustin Belley (1697-1771) who recognized its significance with regard to the odeion as well as an indication of the complex relationships between Rome, Greece and the Anatolian and Syrian kingdoms. According to Belley, the statue base was found by a Turk in Athens on 15th August 1743, during the rebuilding of the foundations of a house. It was subsequently discussed in several publications, including the influential books of Julien David Le Roy and Edward Dodwell.

Despite the interest in the inscriptions during the 18th and 19th centuries, little since has been published about them, or a third Attic inscription mentioning Ariobarzanes and his parents (IG II 2 3428). They have sometimes been cited in more recent publications in terms of their epigraphical significance, but with little regard for the characteristics of the physical objects themselves, and almost never with a mention of their present location. A long inscribed marble base for a statue group of the family of Ariobarzanes II, circa 75-65 BC, is in the Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. E 1094. Inscription IE 272.

See:

Explication d'une inscription antique sur le rétablissement de l'Odeum d'Athénes, par le roi de Cappodoce. In: Histoire de l'Academie Royale des inscripions et belles-lettres..., Tome Vingt-troisieme, pages 189-200. Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1756.

Julien-David Le Roy (1724-1803), Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, page 23. Paris, 1758. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Edward Dodwell (circa 1776-1832), A classical and topographical tour through Greece during the years 1801, 1805, and 1806, Volume 1 (of 2), page 301. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819. At the Internet Archive.

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II. Inscription and translation in the notes on page 91. P. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Although Stuart and Revett were in Athens 1751-1753, before Chandler, Volume II of Stuart's The antiquities of Athens was first published after his death. The notes in this volume and those in the 1825 edition were rewritten by the editor William Newton(1735–1790), with the help of members of the Society of Dilettanti, who added new information gained since Stuart's time in Greece.

See also:

Fabio Augusto Morales, The restoration of Perikles' Odeion at Athens in the first century BC: New and ancient barbarians. In: Revista Heródoto. Unifesp. Guarulhos, Volume 1, Número 1, Março, 2016, pages 73-90. PDF at Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil.

Also at: www.academia.edu/... |

| |

The dedication by the Athenian demos to

Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia (IG II 2 3427).

Source: Παναγιώτης Γ. Καστριώτης,

Το Ωδείον του Περικλέους (Panagiotes

G. Kastriotes, The Odeion of Pericles),

fig. 17, page 159.

In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1914,

pages 143-166. Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική

Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal

of the Archaeological Society of Athens).

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

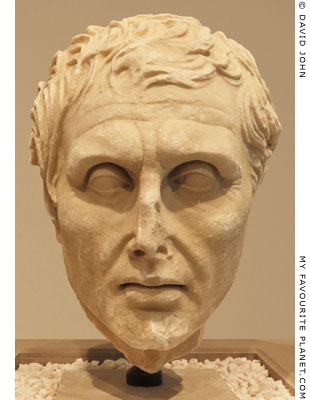

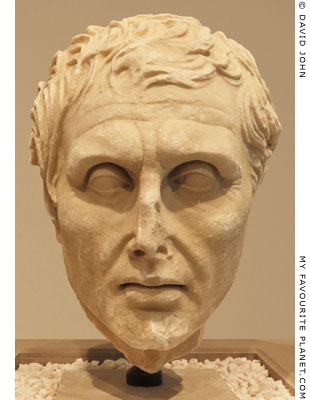

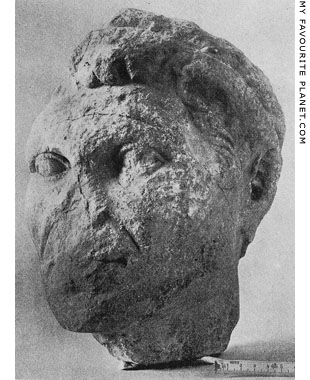

A marble head, perhaps depicting

Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia, whose

portrait is known from coins. Found in

1914 at the Odeion of Pericles, during

excavations led by Greek archaeologist

Panagiotes G. Kastriotes (1859-1931).

Source: Παναγιώτης Γ. Καστριώτης,

Το Ωδείον του Περικλέους (Panagiotes

G. Kastriotes, The Odeion of Pericles),

fig. 20, page 163.

In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1914,

pages 143-166. Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική

Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal

of the Archaeological Society of Athens).

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

10. The location of the Prytaneion in Athens

For further information about the forms and functions of the prytaneion in Greek cities and discussion of theories concerning the location of the Athenian Prytaneion, see:

Stephen G. Miller, The Prytaneion: Its function and architectural form. University of California Press, 1978. At the Internet Archive.

Geoffrey C. R. Schmalz, The Athenian Prytaneion rediscovered?, Hesperia, Volume 75, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar. 2006), pages 33-81. PDF at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA).

11. Phaidros, son of Zoilos

The name Phaidros, son of Zoilos, is otherwise known only from an inscription naming him as the donor of a sundial found in central Athens, now in the British Museum.

Φαῖδρος ⋮ Ζωΐλου

Παιανιεὺς ⋮ ἐποίε[ι].

Phaidros son of Zoilos, from Paiania, made [it].

Inscription IG II 2 5028 (CIG 522)

According to this inscription Phaidros was from Paiania (Παιανία) in eastern Attica, east of Mount Hymettus and 11 km east of the centre of Athens. The claim that he made the sundial himself has led some scholars to believe that he may have been a mathematician or architect.

The sundial was seen in the late 17th century by Jacob Spon and George Wheler in the Byzantine church of Panagia Gorgoepikoos (Παναγία Γοργοϋπήκοος, the swift-hearing Virgin), also known as the Little Metropolis (Μικρή Μητρόπολη, Mikri Mitropoli), and for a short while renamed as the church of Agios Eleutherios (Άγιος Ελευθέριος), which acted as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens during the Turkish occupation, until the modern cathedral was built next to it 1842-1862 (see Demeter and Persephone).

Jacob Spon, George Wheler, Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grece, et du Levant, faités années 1675 et 1676, Tome II, pages 167 and 449. Henry & Theodore Boom, Amsterdam, 1679. At the Internet Archive.

In the early 19th century the sundial was shipped to England by Lord Elgin along with the other "Elgin marbles", and sold to the British Museum. Although it has been dated to around 300 AD, this appears to be connected to the previous dating of the Phaidros Bema, which was discovered in the 1860s. Many scholars now believe the bema was built in the late 4th or early 5th century.

Pentelic marble sundial with four inscribed surfaces.

Inscribed with the name of Phaidros, son of Zoilos.

Height 50.8 cm, length 99.06 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1816,0610.186 (Sculpture 2544, Inscription 72).

Purchased in 1816 from Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin.

12. Date of the Phaidros Bema

For discussion on the date of the Phaidros Bema, see: Alison Frantz, The Date of the Phaidros Bema in the Theater of Dionysos. Hesperia Supplements, Volume 20, Studies in Athenian Architecture, Sculpture and Topography. Presented to Homer A. Thompson, pages 34-39 and 194-195. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), 1982. At jstor.

13. Reliefs of the Phaidros Bema

For detailed descriptions and discussion of the reliefs on the Phaidros Bema, see:

Mary C. Sturgeon, Reliefs from the Theater of Dionysos at Athens. American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 81, No. 1 (Winter 1977), pages 31-53. At academia.edu.

14. "The Arundel Head" of Sophokles

The bronze head is thought to have been found in a well in Smyrna (today Izmir) in the 1620s and taken to Constantinople (Istanbul), where it was purchased for the British art collector Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel (1586-1646). It became part of Howard's large collection of antiquities, known as the "Arundel Marbles" or "Marmora Arundeliana", kept at Arundel House, London, and is therefore referred to as "the Arundel Head".

It featured in a portrait of the earl and his wife Alatheia Talbot, painted circa 1635-1640 by the Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). One version of this painting, known as "the Madagascar Portrait", is now in the collection of the Duke of Norfolk at Arundel Castle, West Sussex, England; the other is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

The head was subsequently acquired by Dr Richard Mead and later Brownlow Cecil, 9th Earl of Exeter, who donated it to the British Museum in 1760.

The long hair, round fillet and beard are typical of Greek portrayals of poets and intellectuals. The inset eyes are now missing. The lips of the slightly open mouth are made of copper, and originally contained teeth, perhaps of silver. Dated to the second to first centuries BC, it was once thought to be a portrait of Homer, and later either a philosopher or Hellenistic king.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. 1760,0919.1 (Bronze 847). Height 29.21 cm.

See: britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/ ...

15. Portraits of Menander

See:

Sarah E. Bassett, The late antique image of Menander. Dept. of Art and Art History, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, 2007. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 48 (2008), pages 201–225.

Olga Palagia, A new interpretation of Menander's image by Kephisodotos II and Timarchos. Estratto da Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane Oriente, Volume LXXXIII, Serie III, 5 - Tomo I, 2005, pages 287-298. SAIA 2006.

16. Diomedes the playwright and Demetrios the sculptor

A statue base of Hymettian marble, signed by Demetrios Philonos Pteleasios, was found on the Late Roman fortification wall, south of the Eleusinion on 3 June 1938.

Δημήτριος Φίλωνος Πτελεάσιος ἐποίησεν

Demetrios son of Philon, from Ptelea, made it

Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens. Inv. No. 1 5486.

See: George A. Stamires, Greek inscriptions, Hesperia, Volume 26, No. 3 (July-September 1957), pages 265-266 and plate 61. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.

Stamires also briefly discussed the identity of Diomedes, based on the inscriptions from the Theatre of Dionysos, Magnesia on the Maeander and Delphi.

The inscription found in the theatre of Magnesia on the Maeander (Asia Minor) mentions comic playwright Diomedes Athenodorou from Pergamon (κωμῳδιῶν Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρου Περγαμηνός) as a participant in the Rhomaia festival.

See: O. Kern, Theaterinschriften von der Agora in Magnesia am Maiandros, in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 19, page 97. Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1894. At the Internet Archive.

An inscribed statue base from Epidauros, on which the polis of Epidauros honours the comic poet Diomedes Athenodorou of Athens (Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρου Ἀθηναῖον, ποιητὰν [κ]ωμῳδιῶν):

ἁ πόλις τῶν Ἐπιδαυρίων

Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρου

Ἀθηναῖον, ποιητὰν

[κ]ωμῳδιῶν, ἀνέθ̣ηκε.

Inscription IG IV 1146.

See: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1883, page (column) 27. Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). Athens, 1884. At the Internet Archive.

A long inscription found on the south wall of the Athenian Treasury in Delphi, dated circa 105 BC, mentions Diomedes Athenodoro[u] (Διομήδην Ἀθηνοδώρο[υ]) in a list of technitai (τεχνῖται, Dionysian artists) participating in the Pythais of 106/105 BC.

See:

Gaston Colin, Fouilles de Delphes, Tome III Epigraphie, 2, Inscriptions du Trésor des Athéniens, No. 49, line 33. École française d'Athènes. E. de Boccard, Paris, 1909.

The Greek text of the inscription (FD III 2:49, line 33): epigraphy.packhum.org/text/239335 at the Packard Humanities Institute. |

|

|

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contents | contributors | impressum | sitemap |

| |