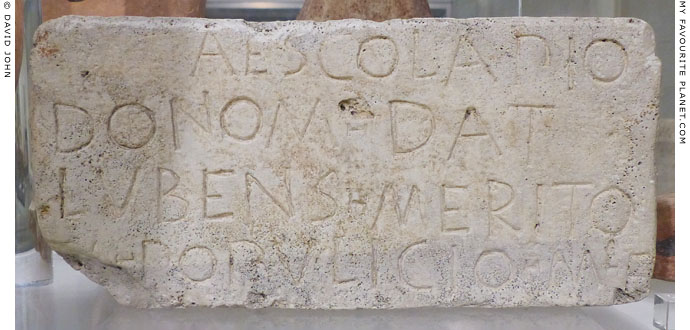

| Asklepios |

Epidauros

Asklepieion |

|

|

|

| |

The Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros from the theatre.

The large white object in the 22 metre wide circular orchestra (ὀρχήστρα, performing

area) is the temporary scenery for an ancient Greek drama performed

in the evening as part of the annual Athens and Epidaurus Festival. |

| |

The site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros covers a large area in a broad valley, around 13 kilometres inland from the ancient port city of Epidauros (Ἐπίδαυρος, today, the seaside village Palaia Epidavros) in the Argolid, northeastern Peloponnese. Its size is comparable with the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi and the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia.

"Epidaurus was called Epitaurus [Ἐπίταυρος]. Aristotle says, that Carians occupied both this place and Hermione, but upon the return of the Heracleidae those Ionians, who had accompanied them from the Athenian Tetrapolis to Argos, settled there together with the Carians. [10]

Epidaurus was a distinguished city, remarkable particularly on account of the fame of Aesculapius, who was supposed to cure every kind of disease, and whose temple is crowded constantly with sick persons, and its walls covered with votive tablets, which are hung upon the walls, and contain accounts of the cures, in the same manner as is practised at Cos, and at Tricca. The city lies in the recess of the Saronic Gulf, with a coasting navigation of 15 stadia, and its aspect is towards the point of summer sunrise. It is surrounded with lofty mountains, which extend to the coast, so that it is strongly fortified by nature on all sides."

H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer (editors), Strabo, Geography, Book 8, chapter 6, section 15. At Perseus Digital Library.

In the Mycenaean period the area of the sanctuary is thought to have been a settlement where there was a cult of Maleatas (Μαλεάτας), probably a hunting hero or deity. During the Archaic period Maleatas appears to have been assimilated into the worship of Apollo, and the remains of an open-air sanctuary of Apollo Maleatas (Ἀπόλλων Μαλεάτας) have been discovered on Mount Kynortion (Κυνόρτιον, Dog’s Climb) to the southeast of the sanctuary, above the theatre. Epidaurians believed that the mythical eponymous founder Epidauros was a son of Apollo. [11] By the fifth century BC Asklepios was seen as a god in his own right and his sanctuary was already established as a healing centre, administered by the oligarchic city state.

In Book 2, chapters 26-27 of his Description of Greece, Pausanias described the sanctuary, including its history and myths, which included the tale that Asklepios was born there.

"That the land is especially sacred to Asclepius is due to the following reason. The Epidaurians say that Phlegyas [Φλεγύας] came to the Peloponnesus, ostensibly to see the land, but really to spy out the number of the inhabitants, and whether the greater part of them was warlike. For Phlegyas was the greatest soldier of his time, and making forays in all directions he carried off the crops and lifted the cattle.

When he went to the Peloponnesus, he was accompanied by his daughter, who all along had kept hidden from her father that she was with child by Apollo. In the country of the Epidaurians she bore a son, and exposed him on the mountain called Nipple [Τίτθιον, Titthion] at the present day, but then named Myrtium [Μύρτιον, Myrtion]. As the child lay exposed he was given milk by one of the goats that pastured about the mountain, and was guarded by the watch-dog of the herd.

And when Aresthanas [Ἀρεσθάνας] (for this was the herdsman's name) discovered that the tale [total] of the goats was not full, and that the watch-dog also was absent from the herd, he left, they say, no stone unturned, and on finding the child desired to take him up. As he drew near he saw lightning that flashed from the child, and, thinking that it was something divine, as in fact it was, he turned away. Presently it was reported over every land and sea that Asclepius was discovering everything he wished to heal the sick, and that he was raising dead men to life.

There is also another tradition concerning him. Coronis, they say, when with child with Asclepius, had intercourse with Ischys, son of Elatus. She was killed by Artemis to punish her for the insult done to Apollo, but when the pyre was already lighted Hermes is said to have snatched the child from the flames.

The third account is, in my opinion, the farthest from the truth; it makes Asclepius to be the son of Arsinoe, the daughter of Leucippus. For when Apollophanes the Arcadian, came to Delphi and asked the god if Asclepius was the son of Arsinoe and therefore a Messenian, the Pythian priestess gave this response:

'O Asclepius, born to bestow great joy upon mortals,

Pledge of the mutual love I enjoyed with Phlegyas' daughter,

Lovely Coronis, who bare thee in rugged land Epidaurus.' [Source unknown.]

This oracle makes it quite certain that Asclepius was not a son of Arsinoe, and that the story was a fiction invented by Hesiod, or by one of Hesiod's interpolators, just to please the Messenians.

There is other evidence that the god was born in Epidaurus for I find that the most famous sanctuaries of Asclepius had their origin from Epidaurus. In the first place, the Athenians, who say that they gave a share of their mystic rites to Asclepius, call this day of the festival Epidauria, and they allege that their worship of Asclepius dates from then. Again, when Archias, son of Aristaechmus, was healed in Epidauria after spraining himself while hunting about Pindasus, he brought the cult to Pergamus.

From the one at Pergamus has been built in our own day the sanctuary of Asclepius by the sea at Smyrna [founded around 165 AD]. Further, at Balagrae of the Cyreneans there is an Asclepius called Healer, who like the others came from Epidaurus. From the one at Cyrene was founded the sanctuary of Asclepius at Lebene, in Crete. There is this difference between the Cyreneans and the Epidaurians, that whereas the former sacrifice goats, it is against the custom of the Epidaurians to do so.

That Asclepius was considered a god from the first, and did not receive the title only in course of time, I infer from several signs, including the evidence of Homer, who makes Agamemnon say about Machaon:

'Talthybius, with all speed go summon me hither Machaon, Mortal son of Asclepius.' [Homer, Iliad, Book 4, line 193] As who should say, 'human son of a god.'"

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 26, sections 3-10. At Perseus Digital Library.

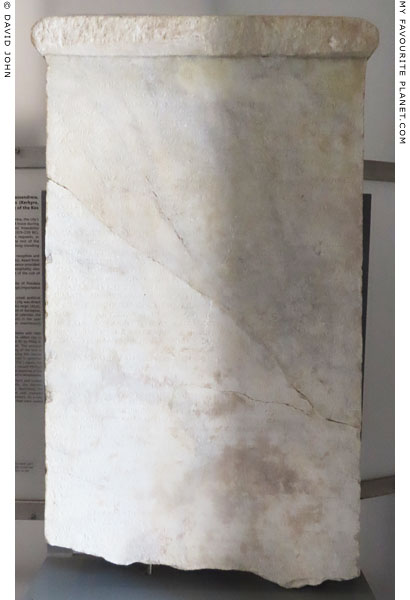

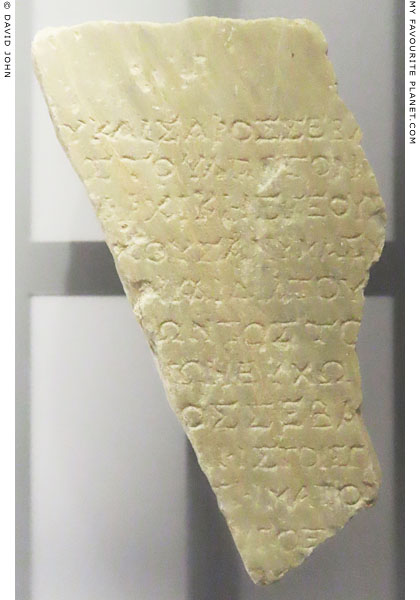

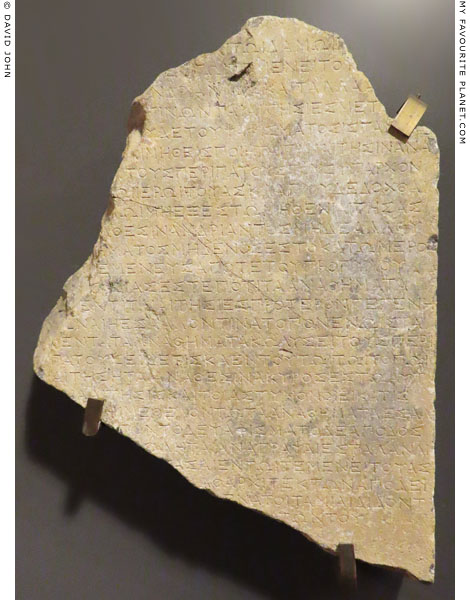

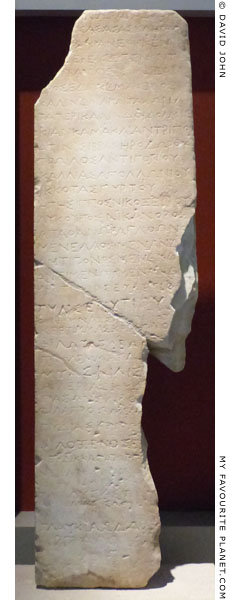

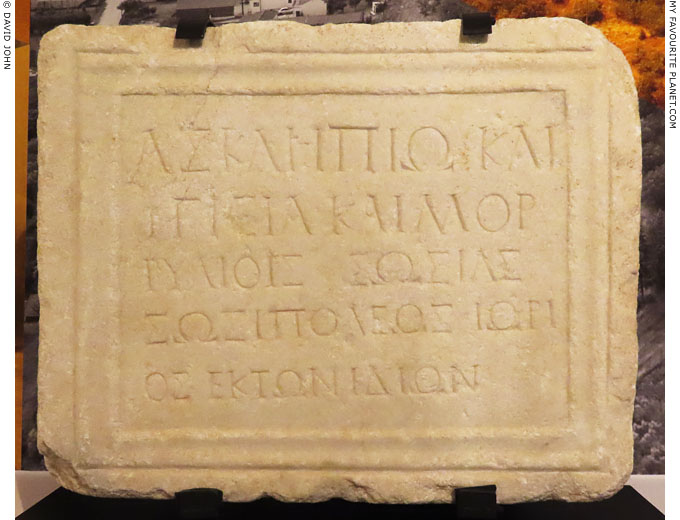

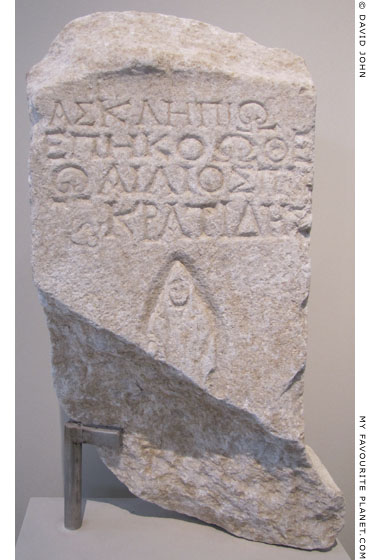

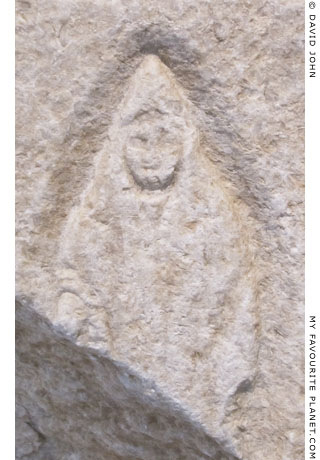

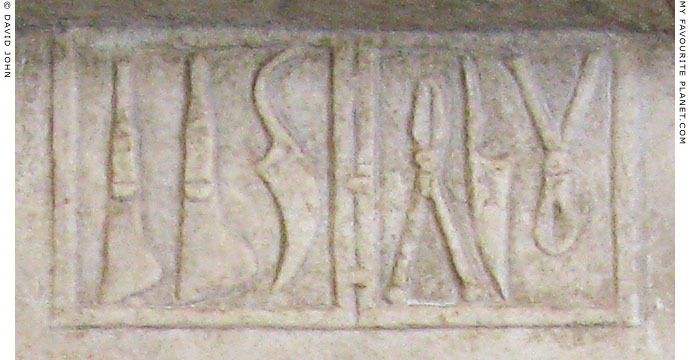

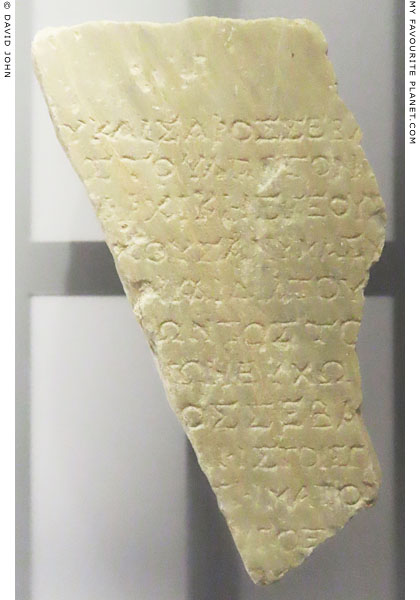

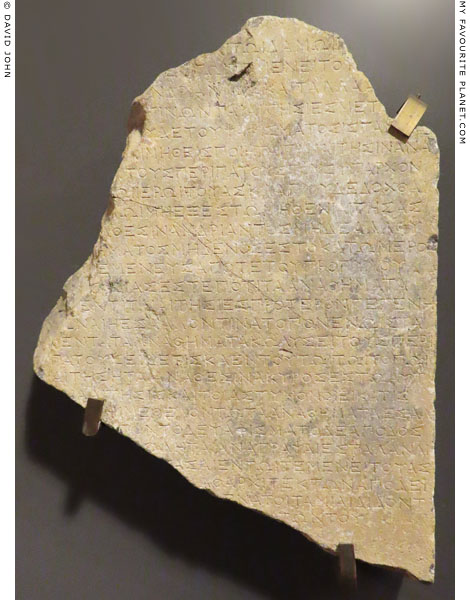

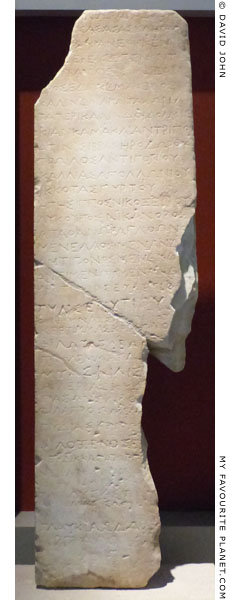

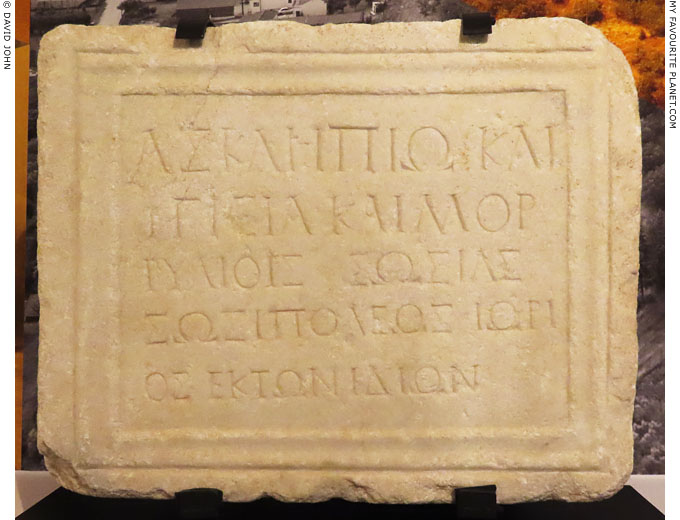

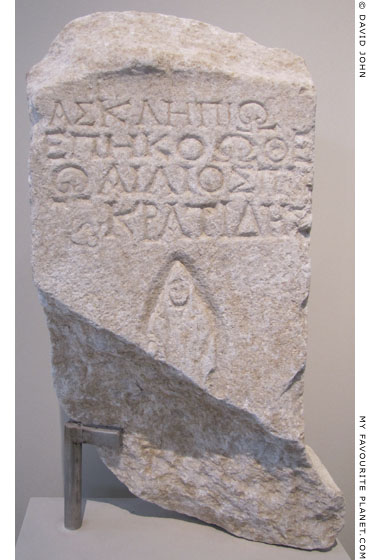

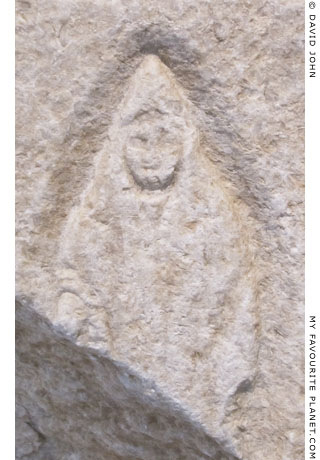

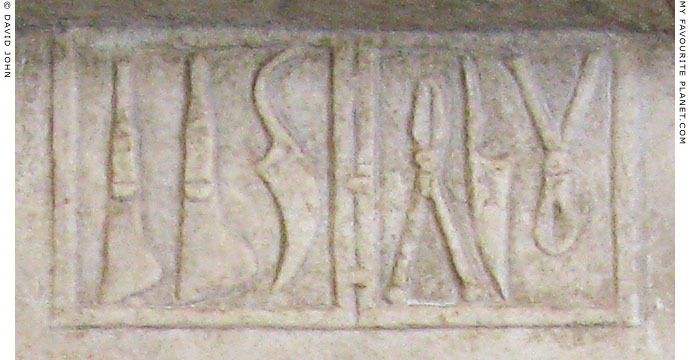

Epidauros' claim to be the birthplace of Asklepios was also supported by the early 3rd century poet Isyllos of Epidauros (Ἴσυλλος Σωκράτευς Ἐπιδαύριος, Isyllos, son of Sokrates, of Epidauros). A limestone stele, dated around 280 BC, discovered in 1885 in the area of the temple is inscribed with a 72 line hymn in honour of Apollo Maleatas and Asklepios, signed by Isyllos. The verse appears to confirm the Delphic oracle mentioned by Pausanias and includes the genealogy of Asklepios: Malos (Μᾶλος) married the Muse Erato (Ἐρατὼ) and they had a daughter Kleophema (Κλεοφήμα). She married Phlegyas and they had a daughter named Aegla (Αἴγλα) or Koronis, who was the mother of Asklepios by Apollo.

Circa 280 BC. Epidaurus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 21.

Inscription IG IV² 1, 128 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

There is also a village called Koroni (Κορώνη) 2.6 km west of the sanctuary.

Today hardly one stone stands on another from the ancient buildings, apart from the large theatre, one of the best preserved ancient Greek theatres and famous for its perfect acoustics. According to Pausanias the architect of both the theatre and the tholos (θόλος, circular building) in the sanctuary was Polykleitos (perhaps the sculptor Polykleitos the Younger).

"Near [the temple of Asklepios] has been built a circular building of white marble, called Tholos (Θόλος), which is worth seeing ... [a description of objects in the tholos] ...

The Epidaurians have a theatre within the sanctuary, in my opinion very well worth seeing. For while the Roman theatres are far superior to those anywhere else in their splendour, and the Arcadian theatre at Megalopolis is unequalled for size, what architect could seriously rival Polycleitus in symmetry and beauty? For it was Polycleitus who built both this theatre and the circular building."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, sections 3 and 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

Built around 340-320 BC, the theatre stands around 500 metres southeast of the sanctuary, built onto the foot of the north slope of Mount Kynortion. 34 rows of white limestone seating were extended to 55 during the Roman period, giving it a seating capacity of around 15,000. Actors performed on the 24.65 metre wide circular orchestra (ὀρχήστρα, performing area), which originally had a surface of beaten earth (see a plan of the theatre below).

It was excavated by the Greek Archaeological Society in 1881-1882. Ancient Greek drama is still performed here in the summer as part of the annual Athens and Epidaurus Festival. [12]

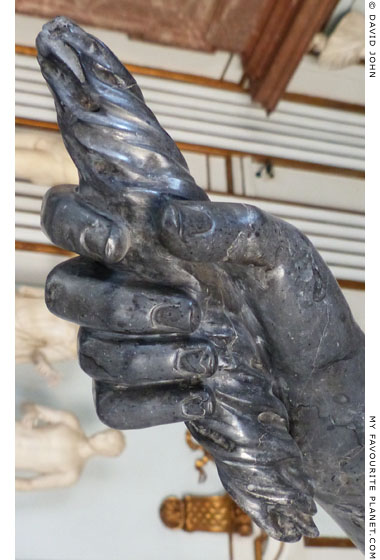

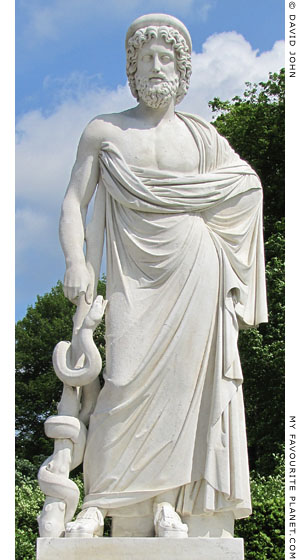

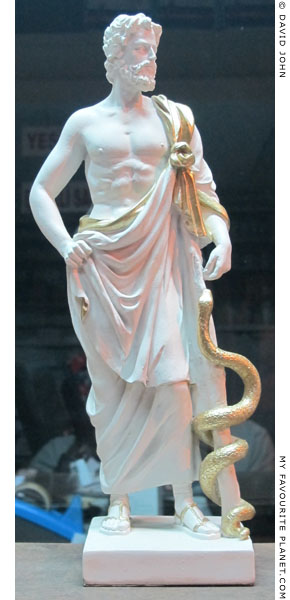

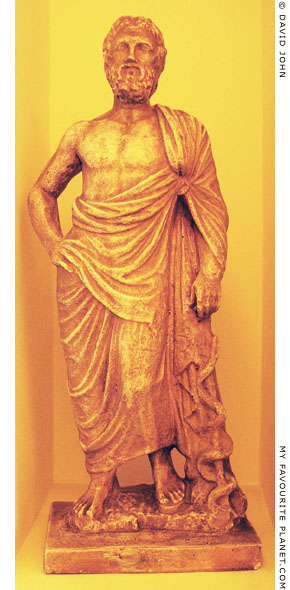

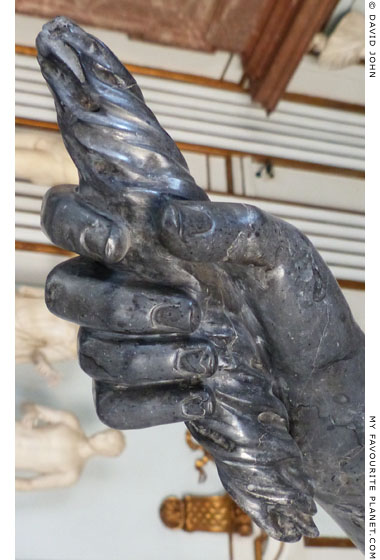

Pausanias also wrote that the cult statue of Asklepios in his temple in the sanctuary was chryselephantine (gold and ivory) and made by Thrasymedes of Paros (early 4th century BC). It depicted the god as enthroned, holding a staff and the head of a snake, and lying by his side was (of all creatures) a dog. The statue, dog and all, are shown on ancient coins of Epidauros.

"The image of Asclepius is, in size, half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold. An inscription tells us that the artist was Thrasymedes, a Parian, son of Arignotus. The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of the serpent; there is also a figure of a dog lying by his side. On the seat are wrought in relief the exploits of Argive heroes, that of Bellerophontes against the Chimaera, and Perseus, who has cut off the head of Medusa."

Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, section 2.

The first excavations were undertaken here in 1881-1887 and 1891-1894 by Greek archaeologists Panagiotis Kavvadias and Valerios Stais for the Archaeological Society of Athens. Among the important finds have been inscriptions containing the accounts of building works at the sanctuary which provide fascinating historical information. The inscription dealing with the building costs of the tholos (IG IV²,1 103 at The Packard Humanities Institute), the circular building, the function of which remains unknown despite several theories, is referred to as a thymela (θυμέλα, or θυμέλη, thymele), usually used to signify an elevation or altar in the centre of the orchestra (circular performing area) of a theatre.

One long inscription (IG IV²,1 102), found in 1885 to the east of the temple of Asklepios in the sanctuary, lists the costs of the Doric temple's construction (around 375 BC), which took four years, eight months, and ten days, and names some of the people who did the work. The project was superintended by the architect Theodotes (Θεόδοτος), who received 353 drachms a year, little more than a labourer's wage. A Thrasymedes (the same artist who made the cult statue?) undertook to execute the roof, wood covered with marble tiles, and the doors, made of ivory at a cost of 3070 drachmas. A sculptor named Timotheos (perhaps the Timotheos from Epidauros, contemporary of Skopas, Bryaxis and Leochares) is named as the maker of models after which various artists executed the figures in Pentelic marble on the pediments (gables) and those that stood on the roof (aktroteria). A sculptor named Hektoridas (Ἑ̣κτορίδας) was paid 1400 drachmas for the sculptures on one of the pediments. The sculptures of the western pediment are thought to have depicted a battle with the Amazons (Amazonomachy), and those on the eastern pediment a battle with the Centaurs (Centauromachy).

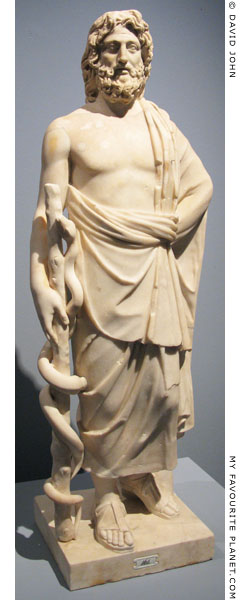

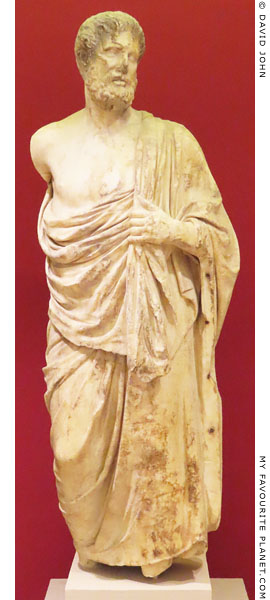

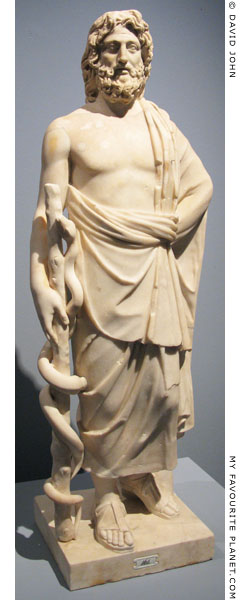

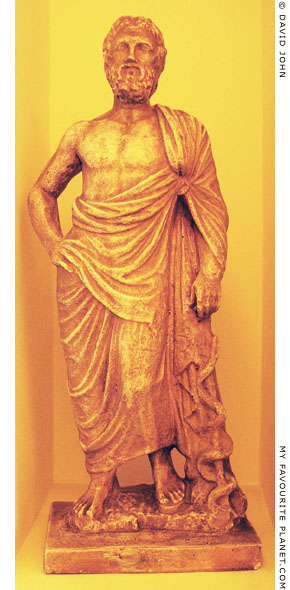

The sanctuary is an important, atmospheric archaeological area in beautiful countryside, and a UNESCO World Heritage site. It has its own small museum, including inscriptions and architectural fragments, although many of the best artefacts (e.g. the statue of Asklepios and a statuette of Asklepios as young man, above, right) are now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, where most are not even on display. |

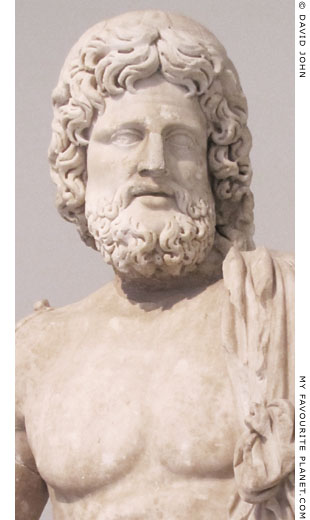

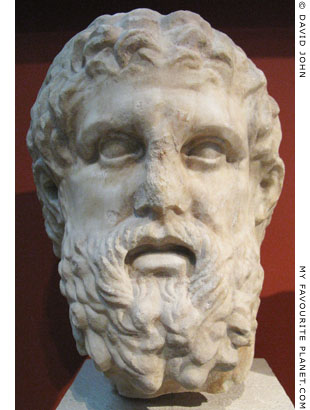

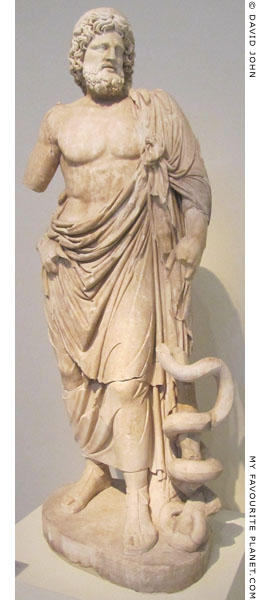

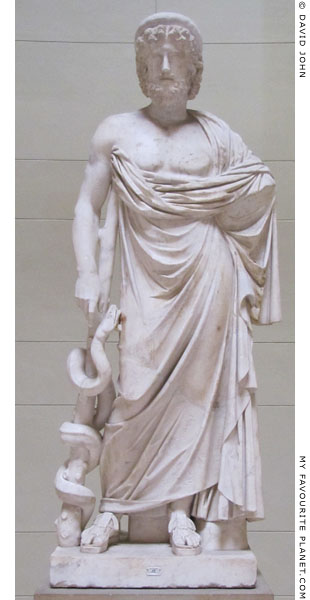

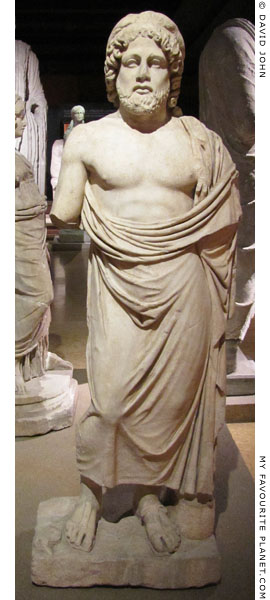

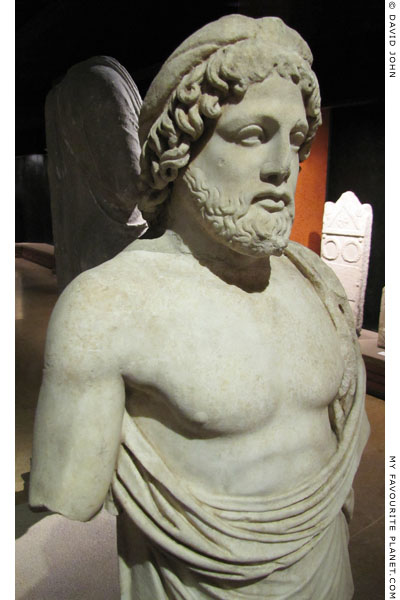

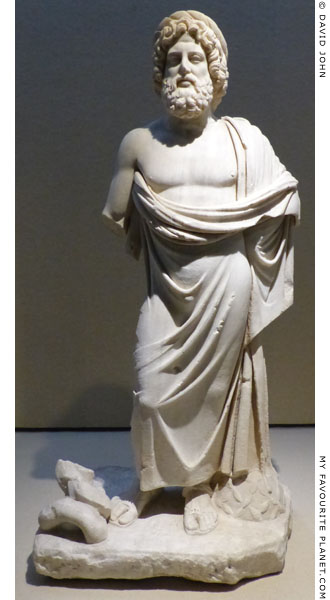

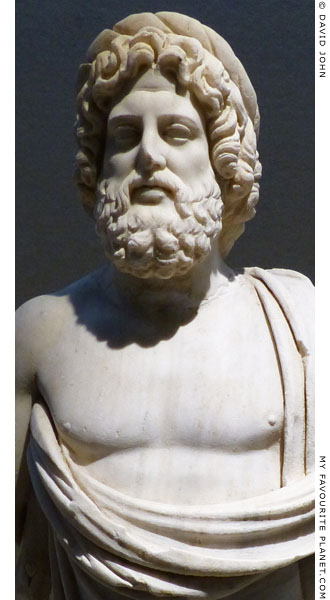

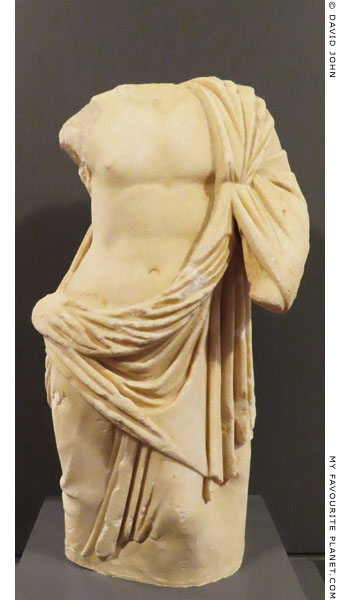

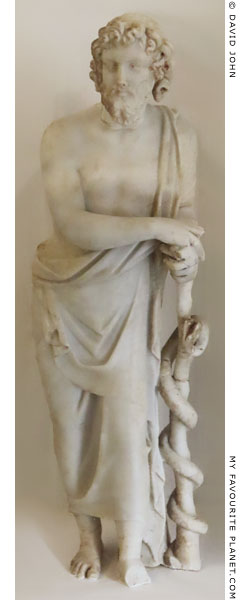

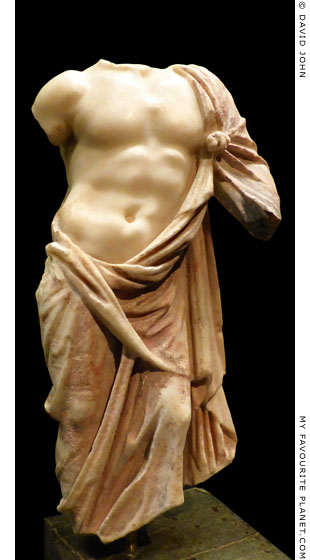

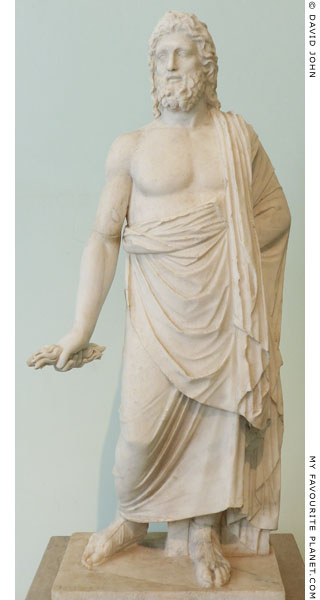

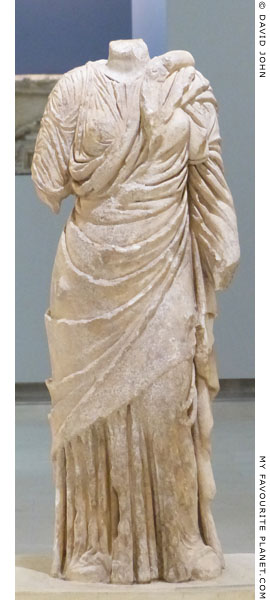

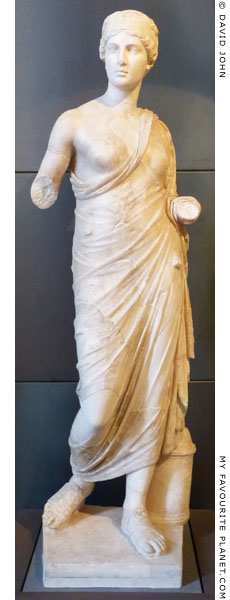

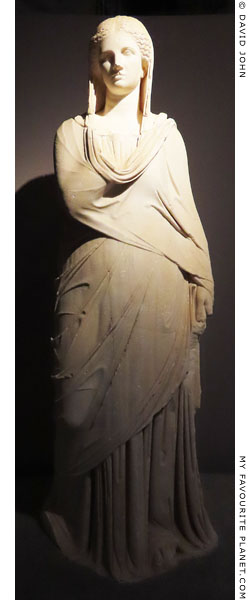

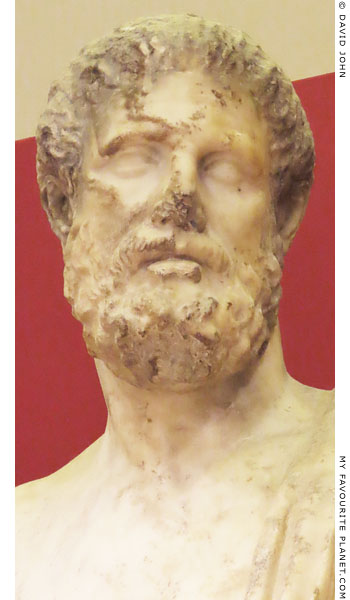

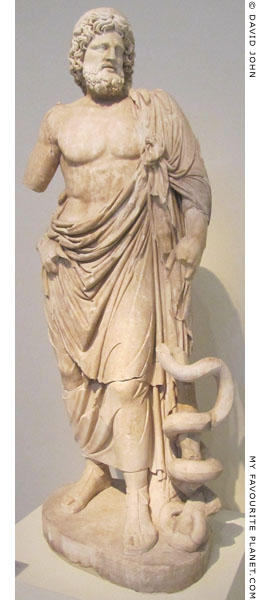

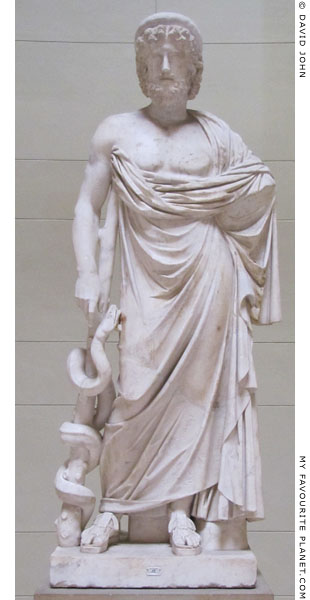

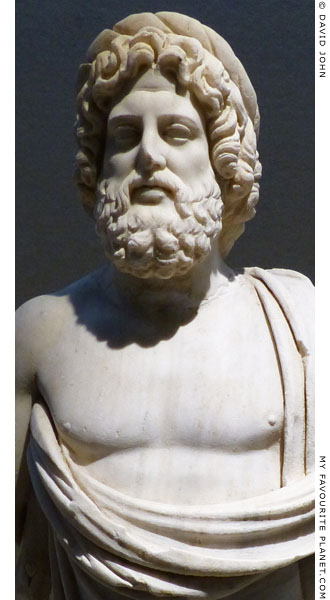

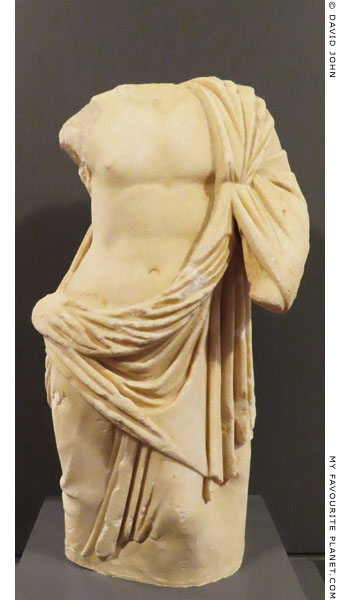

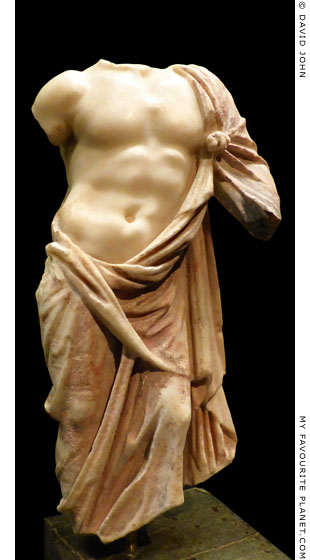

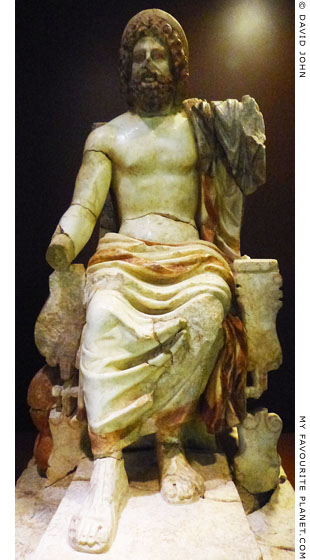

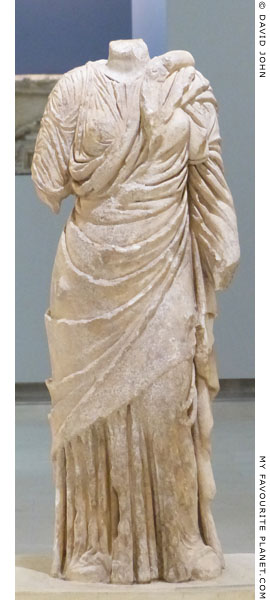

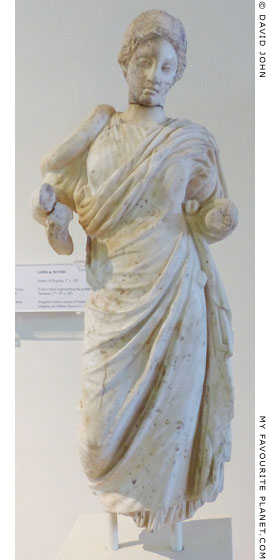

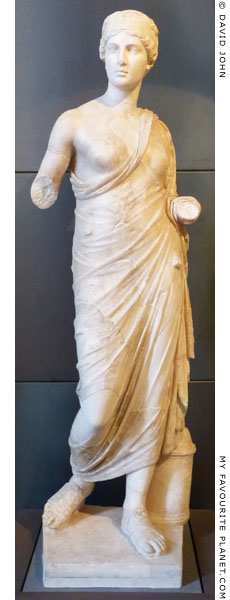

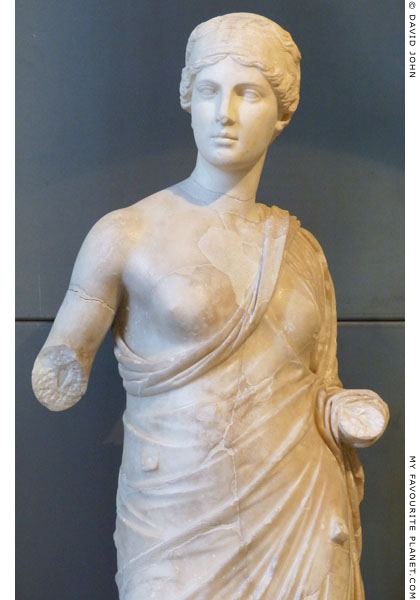

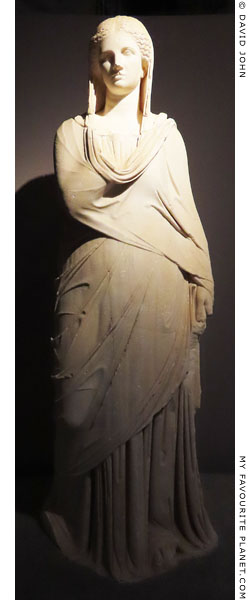

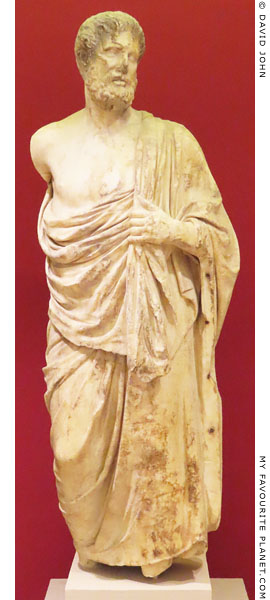

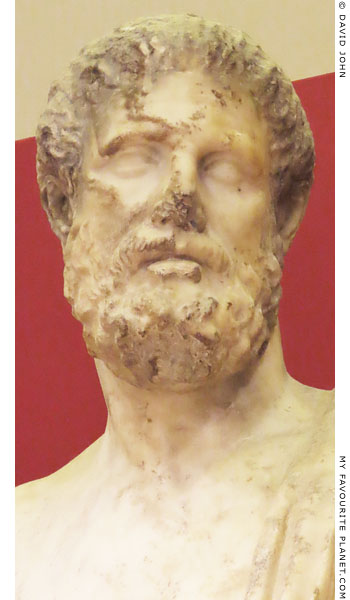

Statue of Asklepios from the

Sanctuary of Asklepios at

Epidauros, Peloponnese, Greece.

Pentelic marble. Circa 160 AD.

The statue belongs to the "Este type"

(variants of the "Chiaramonti type")

copies of a 4th century BC original.

One of the 29 known freestanding

marble figures of Asklepios from

the Epidauros sanctuary.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 263. |

| |

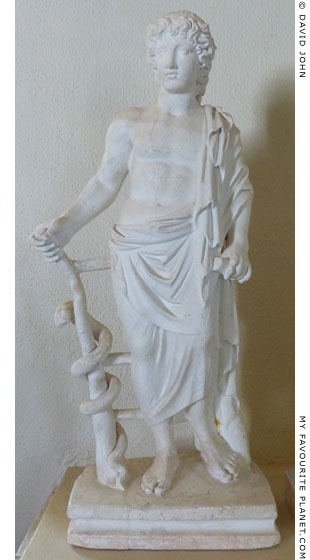

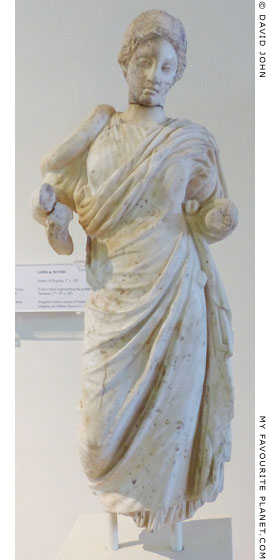

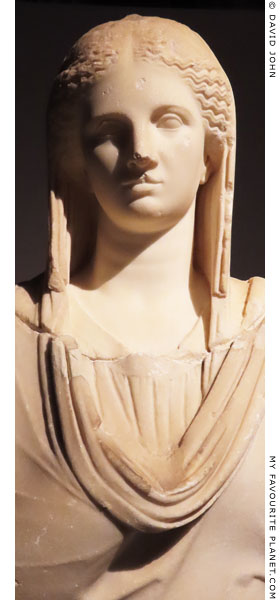

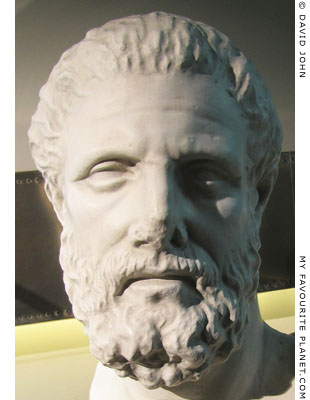

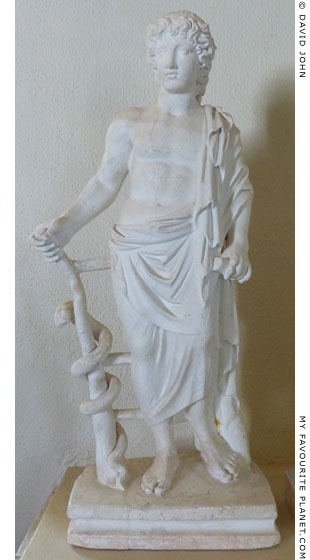

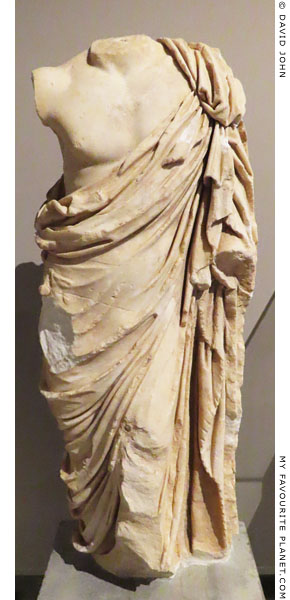

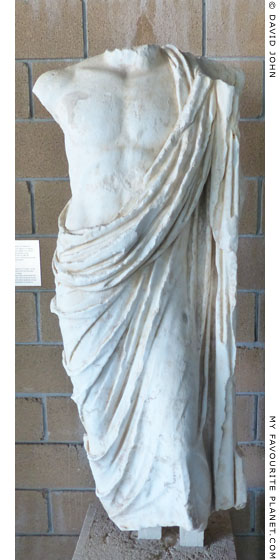

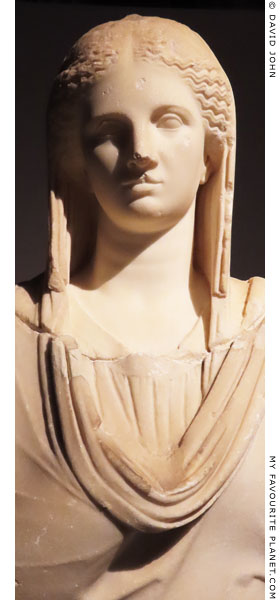

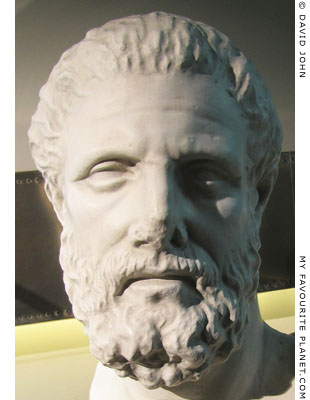

Plaster cast of a marble statuette of

Asklepios as a beardless youth, found

in the Sanctuary of Apollo Maleatas,

Epidauros in 1896.

Epidauros Archaeological Museum.

The original is in the

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. NAMA 1809. |

| |

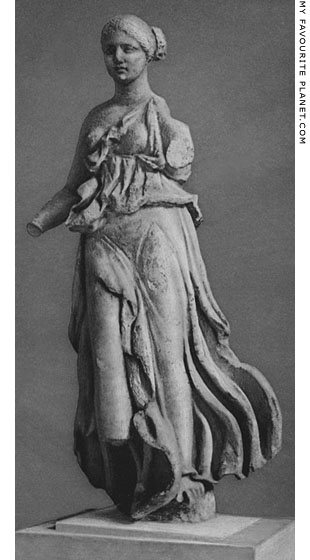

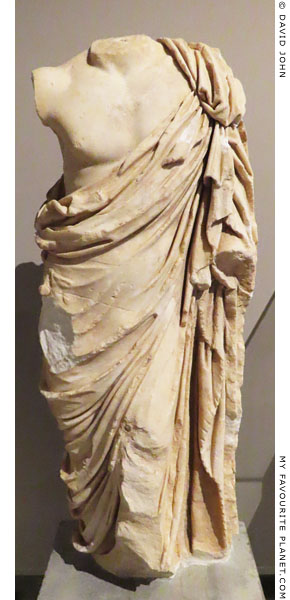

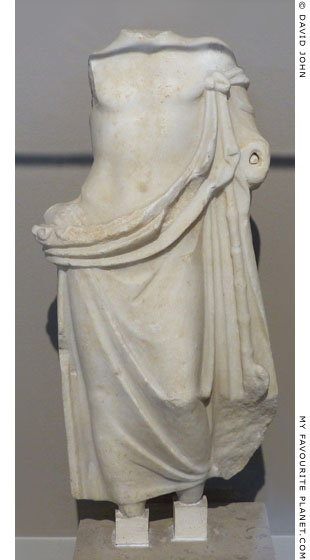

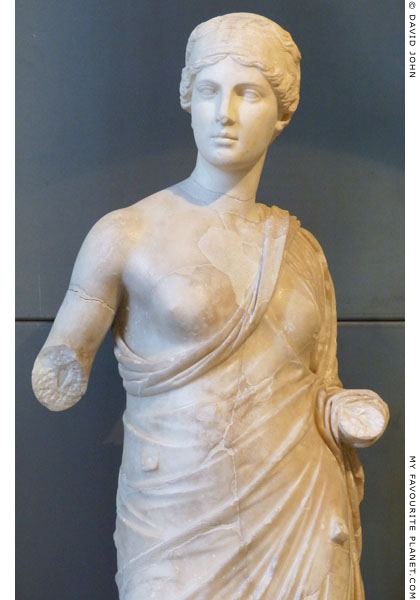

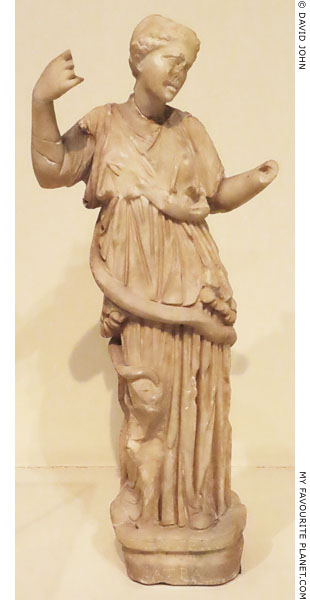

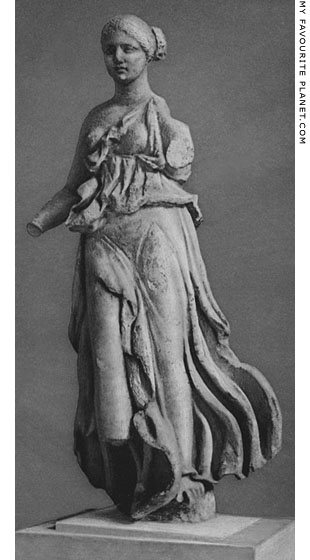

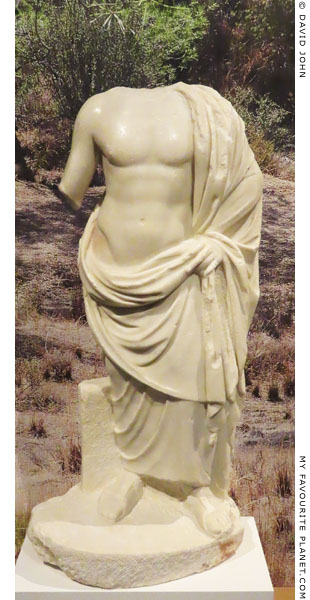

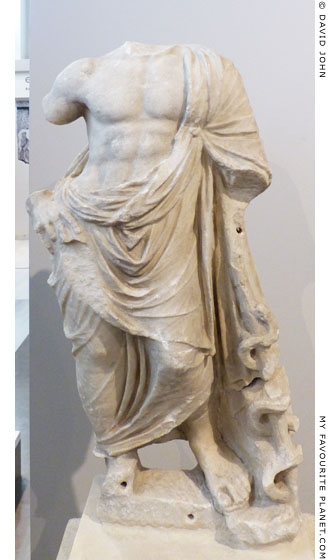

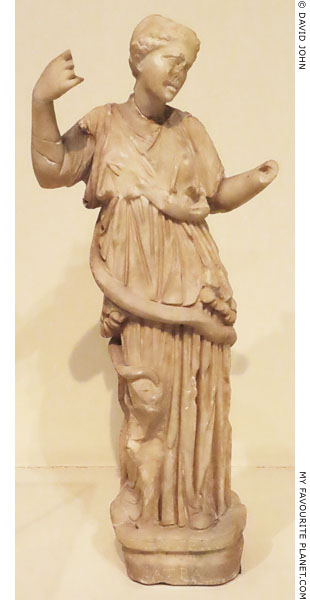

A marble statuette of a flying Nike, wings,

arms and right foot now missing. The best

preserved of three similar statues found

built into a wall in the Sanctuary of

Asklepios, Epidauros. They may have

been akroteria from the roof above the

west pediment of the temple of Artemis

in the sanctuary.

Late 4th century BC. Parian marble.

Height 81 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 159.

Source: Elie Cabrol, Voyage en Grèce

1889, Notes et Impressions. Librairie

des Bibliophiles, Paris, 1890. |

| |

| |

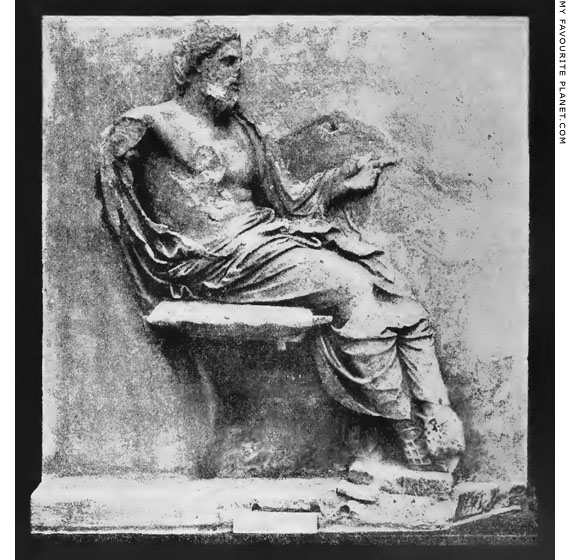

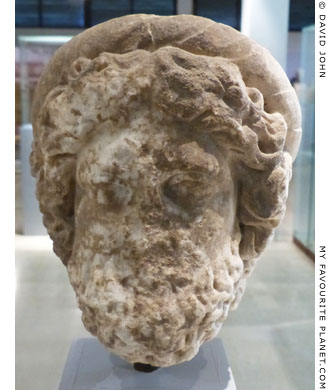

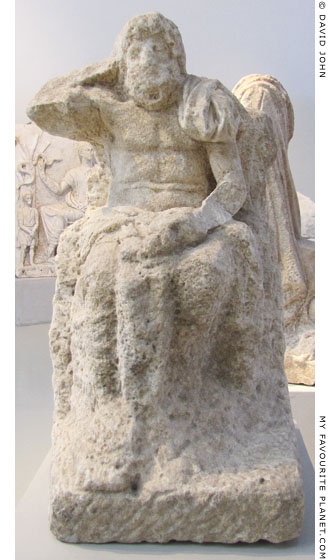

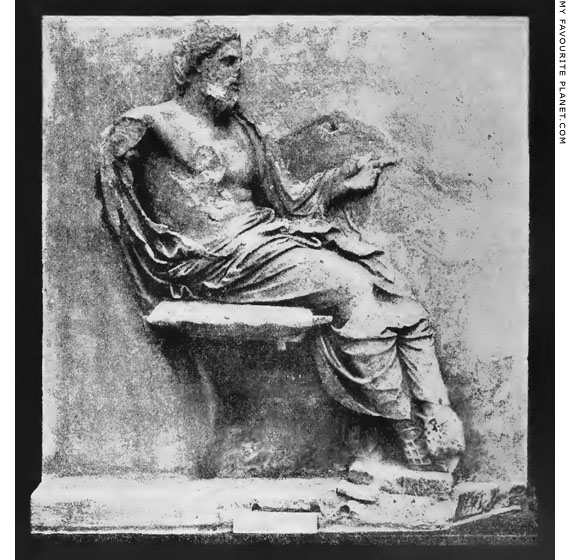

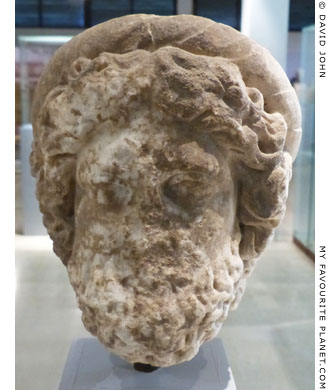

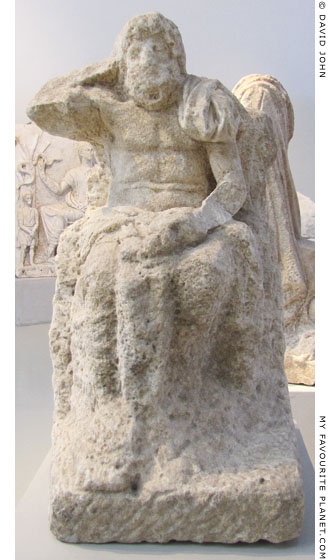

A fragmentary marble relief of Asklepios enthroned, found in 1884, built into

a Medieval wall east of the temple of Asklepios at Epidauros. This is the better

preserved two similar, reliefs of Pentelic marble found in the sanctuary (the

other Inv. No. 174), which may be architectural sculptures, perhaps metopes,

or votive plaques. [13] This image may show the healing god as he was depicted

in the cult statue made by Thrasymedes of Paros (early 4th century BC).

The bearded, male figure, is seated on a cushioned throne, facing right. His sandalled

feet are crossed and his right heal rests on a footstool. His himation is draped over

his left shoulder and arm, falls behind his back and covers his lower body and legs.

His left hand is extended as is the index finger (the only surviving finger). His right

arm and the front parts of his feet are missing, as are the staff, snake and dog said

by Pausanias to have been a part of the statue.

Around 380-370 BC. Height 64 cm, width 58 cm (before restoration 47 cm).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 173.

Source: Pausanias's Description of Greece, Volume 3 (of 6), translated with a commentary

by J. G. Frazer, fig. 39, page 242. Macmillan and Co., London, 1898. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

A plan of the theatre in the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros, built around 340-320 BC.

The width of the cavea (audience seating area) is 119 metres and the diameter of the orchestra

(ὀρχήστρα, circular performing area) 24.65 metres. The original lower 34 rows of white limestone

seating are divided from the later Roman period upper 21 rows by a diazoma (διάζωμα, girdle)

horizontal walkway. The lower rows are divided into 12 wedge-shaped sections known as kerkides

(κερκίδες; sigular, κερκίς, kerkis), by 13 staired aisles called klimakes (κλίμακες; singular, κλίμαξ,

klimax, stairway or ladder), each around 60 cm wide. The upper rows consist of 22 kerkides divided

by 23 klimakes. See some more technical terms for Greek theatres on Acropolis gallery page 36.

Source: Pausanias's Description of Greece, Volume 3 (of 6), translated with a commentary

by J. G. Frazer, fig. 39, page 252. Macmillan and Co., London, 1898. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

| Asklepios |

Athens

Sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia |

|

|

|

| |

The sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia in Athens, below the walls of

the south side of the Acropolis, and directly beneath the Parthenon.

|

The Athenian Asklepieion, the sanctuary of Asklepios and his daughter Hygieia, was founded in 420/419 BC by Telemachos (Τηλέμαχος), an Athenian from the deme of Acharnai (Ἀχαρναί), west of the city. The sanctuary is located to the west of the Theatre of Dionysos, on the South Slope of the Acropolis, between the Peripatos circuit path around the foot of the Acropolis and the rock itself (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 34).

The sanctuary contained a small Ionic temple, an altar, a bothros (pit for sacrifices) and two halls: the abaton, a Doric stoa (see photo below) used as an incubation hall in which visitors slept and were cured by the god who appeared in their dreams; and the katagogion, an Ionic stoa which provided accommodation for the priests and visitors. The cleft in the rock behind the sanctuary contained a sacred spring.

Pausanias briefly mentioned the sanctuary when describing the way from the theatre to the Acropolis:

"The sanctuary of Asclepius is worth seeing both for its paintings and for the statues of the god and his children. In it there is a spring, by which they say that Poseidon's son Halirrhothius deflowered Alcippe the daughter of Ares, who killed the ravisher and was the first to be put on trial for the shedding of blood."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

The sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia in Athens: reconstructed

columns and part of the entablature of the Doric stoa (abaton). |

| |

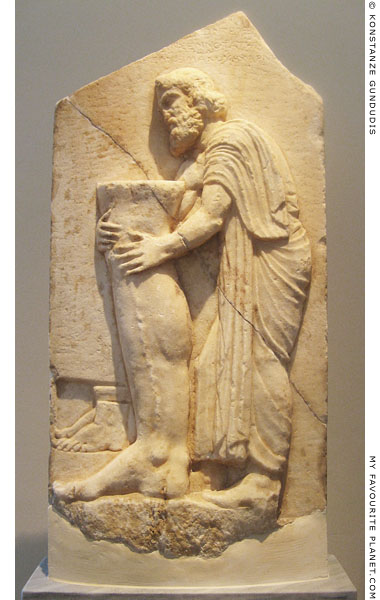

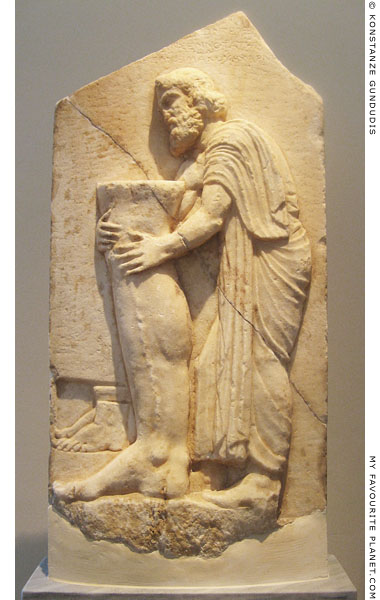

The votive relief of Lysimachides, a fragmentary marble relief

dedicated by Lysimachides (Λυσιμαχίδης) to Asklepios in Athens.

Late 4th century BC. Discovered in Autumn 1892 at the sanctuary

of Amynos, northwest of the Athens Acropolis and south of the

Areopagus hill. Pentelic marble. Height 73 cm, width 35 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3526.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis

|

The bearded male on the relief is thought to depict Lysimachides, although it has also been suggested that he may be Amynos. He is shown in profile facing left, bending forwards as if placing the colossal right leg he is holding with both hands in the sanctuary. The leg has a prominent vein, and he is either appealing to the god to heal his complaint, probably varicose veins, or the relief is an ex voto, dedicated in fulfilment of a vow to thank the deity for his cure. In a niche in the background stand two feet, perhaps previously dedicated to the god. Above the figure is part of the dedicatory inscription naming the man as Lysimachides, son of Lysimachos, from the deme of Acharnai (Ἀχαρναί), west of Athens.

— ο̣ιων τευξα — —

— ων σεμνοτάτην — —

[Λυσιμαχί]δης Λυσιμάχου Ἀχαρνε[ύς].

Inscription IG II² 4387.

See also the "Lysimachides relief" from Eleusis in Demeter and Persephone part 2.

Acharnai was also the deme of Telemachos, who founded the sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia beneath the Acropolis around a century earlier (see above).

Amynos (Ἄμυνος) was a local heroized or deified healer, who is not mentioned in the surviving works of ancient authors. His sanctuary, the Amyneion, became associated with the worship of Asklepios from at least the fourth century BC. The site included a small chapel, a well and a table for sacrifices, and the earliest finds are from the sixth century BC. Several other inscriptions and dedications found there, dating from the fourth to second centuries BC, are related to healing, including anatomical votives with depictions of various body parts. Some inscriptions show that the sanctuary was the meeting place of the sacrificing associates (orgeones) of Amynos, Asklepios and Dexion, while other dedications were to Amynos and Asklepios.

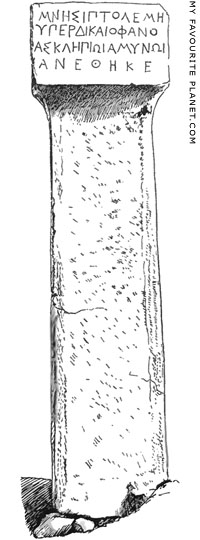

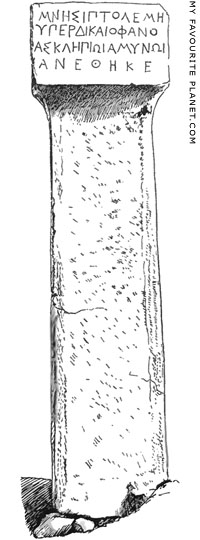

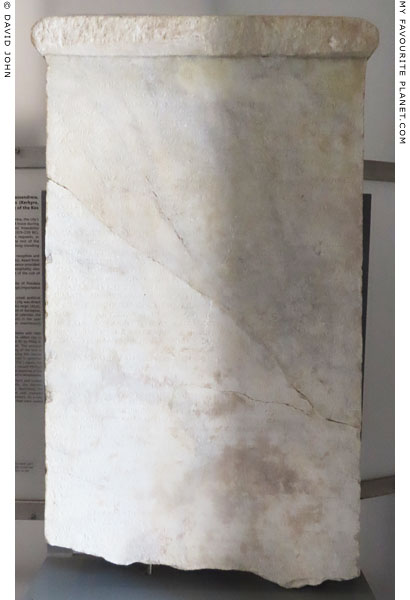

Following preliminary excavations by Wilhelm Dörpfeld in Autumn 1892, during which the relief was discovered, the sanctuary was more thoroughly excavated in early 1895 by Alfred Koerte. Among the many dedications discovered by Koerte was an inscribed stele, dated to the fourth century BC, dedicated by a woman named Mnesiptoleme on behalf of Dikaiophanes to Asklepios Amynos (see drawing, right). This led to debate over whether the cult of Amynos had been assimilated by that of Asklepios. Perhaps Amynos had gradually ceased to be worshipped as a separate deity, and his name had become an epiphet of Asklepios.

The stele of bluish marble was found in the well of the sanctuary. It is in the form of a pillar with a cavatto capital (similar to the base of a statue by the sculptor Onatas). At the top the capital is a cutting (hole), 16.5 cm wide and 7.5 cm deep, for the attachment of the votive offering, perhaps a statue or a relief.

Total height of stele 118 cm. Shaft width bottom 25 cm, width top 23 cm, depth 17 cm. Capital width 32 cm, height 19 cm. Inscription letters 2 cm high.

The inscription on the capital:

Μνησιπτολέμη

ὑπὲρ Δικαιοφάνος

Ἀσκληπιῶι, Ἀμύνωι

ἀνέθηκε.

Mnesiptoleme on behalf of Dikaiophanes

dedicated (this) to Asklepios Amynos.

Inscription IG II² 4365.

See:

Jane Ellen Harrison (1850-1928), Primitive Athens as Described by Thucydides, "The Amyneion", pages 100-105. Cambridge University Press, 1906. At the Internet Archive.

Illustration right, Fig. 32, page 103. Inscription first published in Alfred Koerte, Das Heiligtum des Amynos (see below).

Alfred Koerte, Bezirk eines Heilgottes, in Mittheilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 18, pages 231-256, plate XI (votive relief of Lysimachides). Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1893. At the Internet Archive. The article includes extracts from Dörpfeld's report on the site.

Alfred Koerte, Das Heiligtum des Amynos, in Mittheilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 21, pages 287-332, Tafel XI (plan of sanctuary by Wilhelm Wilberg). Barth & von Hirst, Athens, 1896. At the Internet Archive.

So far I have found no information concerning the present location of the Mnesiptoleme pillar (the Epigraphical Museum, perhaps?). Although several recent publications have mentioned it, and particularly the inscription, none state where it is now kept or include a photo. |

|

A marble pillar from the

sanctuary of Amynos, with

a dedication to Asklepios

Amynos on the capital. |

|

| |

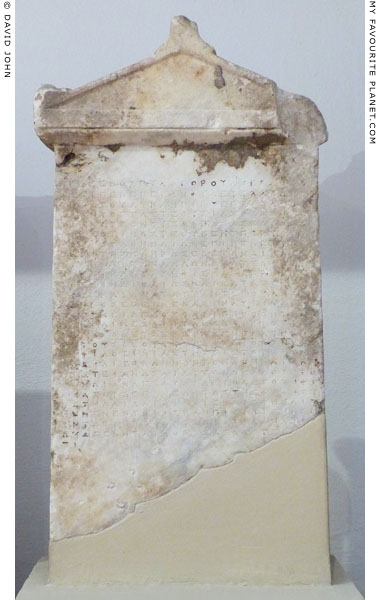

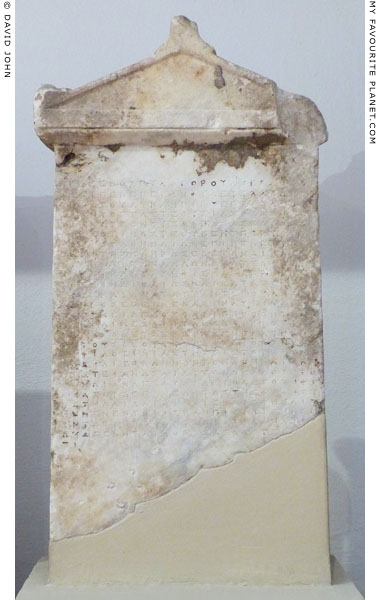

A marble stele inscribed with a decree of the Athenian tribe

Hippothontis (Ἱπποθοντίς) honouring Phyleos (Φυλεος) son

of Chairias from Eleusis, who had been a priest of Asklepios

and successfully undertaken various public duties.

Around 288/287 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 7714.

Inscription IG II² 1163. |

| |

| Asklepios |

Kos

Asclepieion |

|

|

|

| |

The Asklepieion in Kos, Dodecanese, Greece.

The view from the highest of three stepped terraces built onto a north-facing hillside, which comprise

the sanctuary of Asklepios, 4 kilometres west of Kos, the island's main town and port. In the distance

is the island's north coast, just 5 kilometres south of the peninsula of Bodrum (ancient Halicarnassus).

|

| New article about the Asklepieion in Kos currently in preparation. |

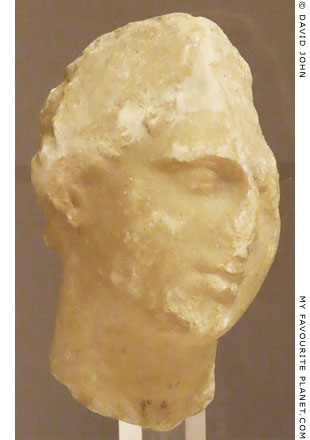

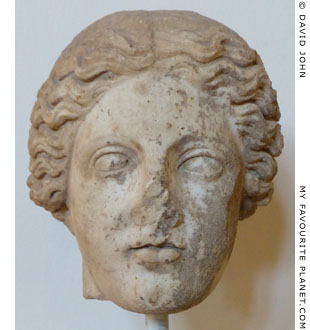

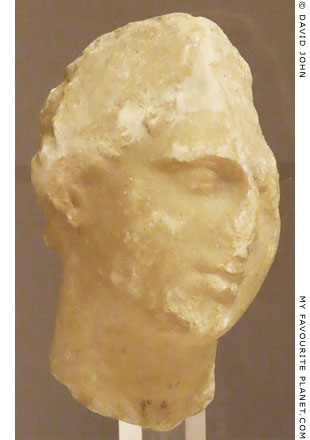

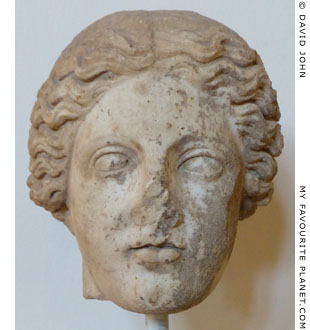

One of two fragmentary marble heads of

female statuettes found in the Asklepieion

of Kos. 340-330 BC. Attributed to the

workshop of Praxiteles' sons, Kephisodotos

the Younger and Timarchos

(see Kephisodotos the Younger).

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

One of the seven reconstructed Corinthian

columns of "Temple C" (see below) on the

middle terrace of the Kos Asklepieion.

2nd century AD. |

| |

| |

The remains of "Temple B", thought to have been dedicated to Asklepios, on the middle terrace

of the Kos Asklepieion. The Ionic temple, distyle in antis, was built around 300-270 BC opposite

the large altar which had been constructed in the mid 4th century BC. |

| |

The remains of "Temple C" on the middle terrace of the Kos Asklepieion. The peripteral

temple, built in the Antonine period (138-193 AD), was possibly dedicated to Apollo. |

| |

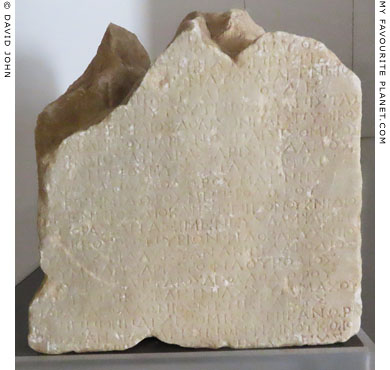

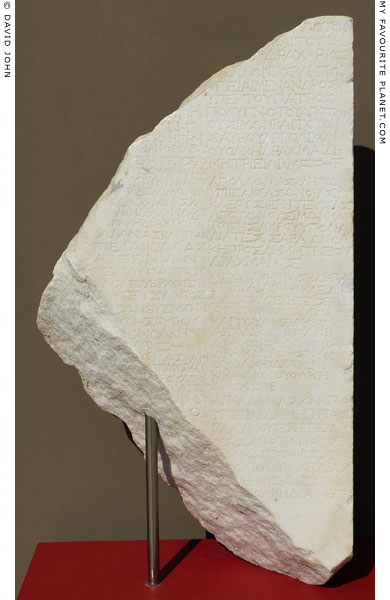

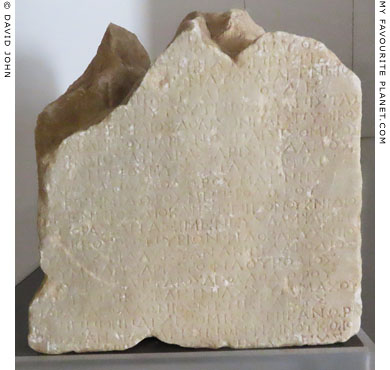

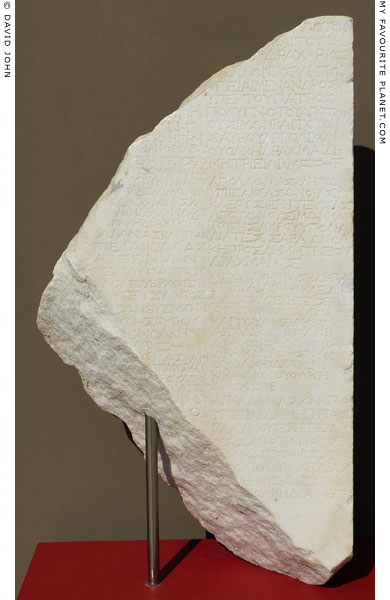

Part of a stele inscribed with decrees of cities of Macedonia

(Kassandreia, Amphipolis, Philippi) and the Ionian islands

(Kerkyra, Leukas) recognizing the asylia (inviolability) of the

Kos Asklepieion. 242 BC.

In 242 BC Kos sent theoroi (sacred ambassadors) to several

Greek cities, including those in Magna Graecia (southern Italy)

and Sicily, with a number of requests, including asylia and a

sacred pan-Hellenic truce during the time of the Great

Asklepieia Games. The granting of these conditions by the

decrees of various cities was important to the prestige of

the Asklepieion and Kos itself. The decrees were published

in the sanctuary. Another surviving (but very worn) stele

records similar decrees from Neapolis (today Naples) and

Elea in southern Italy, as well as Pella in Macedonia and

another city whose name is now missing, perhaps Pydna.

At the time Macedonia was ruled by King Antigonus II

Gonatas (319-239 BC), a rival of the Ptolemies of Egypt

of whom Kos was an ally. Nevertheless, the Koans declared

allegiance to Antigonus and a portrait of the king, painted

by Apelles, was exhibited in the sanctuary (see above).

Epigraphical pavilion, Asklepieion archaeological site, Kos. |

|

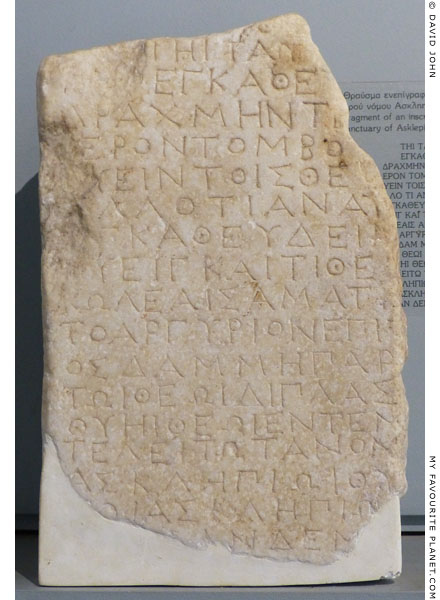

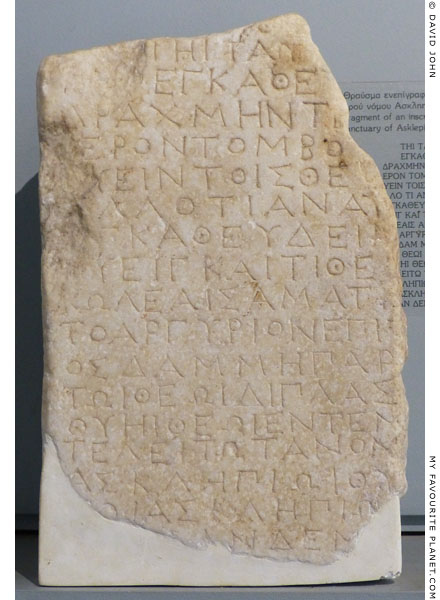

A fragment from the upper part of a marble stele inscribed

on four sides with lists of victors in the Great Asklepieia

Games of 242/241 BC (the 1st games) - 202/201 BC (the

11th games). The surviving names on sides A-D are from

the years 242/241, 230/229, 218/217, 214/213, 210/209

and 206/205 BC.

Another, more complete stele, reassembled from several

fragments, records the victors of 198/197 BC (the 12th

games) - 170/169 BC (the 19th games). In total the two

surviving steles recorded results from 13 of the 19

Asklepieia Games known to have been held in Kos. The

chronological listing for each of the games includes the

name and patronymic (father's name) of the priest of

Asklepios, the monarch (eponymous magistrate of Kos)

and the agonothete (official in charge of the games).

The winner's name, patronymic and ethnic (place of

origin - when other than Kos - were inscribed. In later

years (e.g. the 18th and 19th games) the name of the

second finalist (runner-up) was also recorded.

Epigraphical pavilion, Asklepieion archaeological site, Kos. |

|

| |

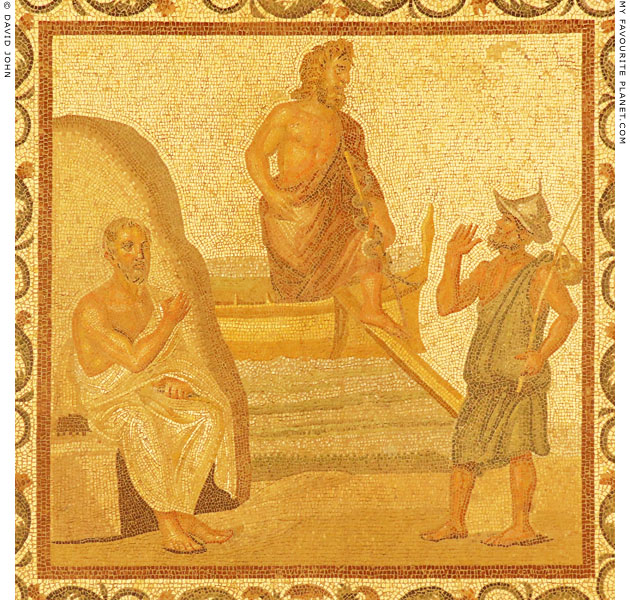

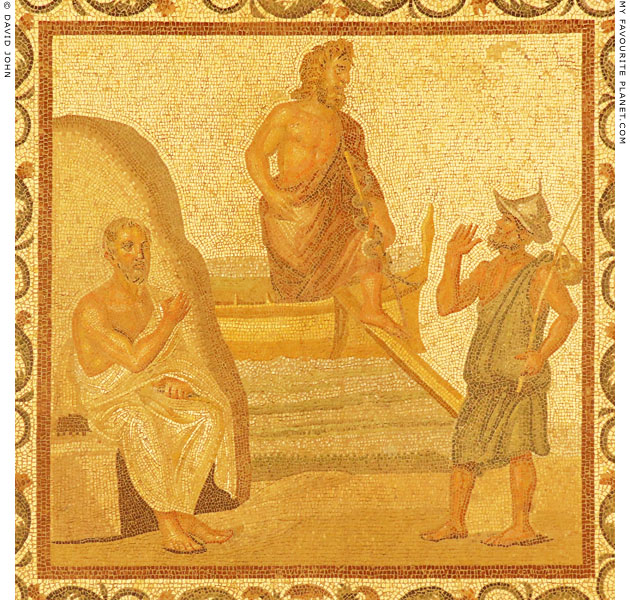

The central panel of a floor mosaic from Kos depicting the arrival of Asklepios on the island by ship.

The bearded god, wearing a himation and carrying a snake-entwined staff with his left hand, steps

with his left foot from the ship onto the gang-plank leading to the shore. He is greeted by a rustic-

looking figure thought to represent a Koan (inhabitant of Kos), standing on the right. On the left

a bearded figure in a white himation, believed to be Hippokrates, sits in front of a large rock.

2nd-3rd century AD. Found in the Roman period "House of Asklepios" on the Seraglio Hill

(λόφο των Σερραγιών, also referred to as the Serayai or Seragia), the ancient acropolis

of Kos, now known as the "Old Town". 115 x 115 cm.

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A drachm coin of Kos with the snake symbol

of the Asklepios cult and the inscription

ΔΙΟΓΕΝΗΣ Α (Diogenes A), surrounded by

a wreath. 200-190 BC.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. N450. |

|

A drachm coin of Kos with the head of Asklepios

in profile, facing right. After 180/170 BC.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. N1524. |

|

| |

Bronze coin of Kos with the head of Asklepios

in profile, facing right, wearing a laurel wreath.

200-180 BC, Hellenistic period.

New Archaeological Museum

"Arethousa", Chalkis, Evia.

Formerly in the Archaeological Museum of

Chalkis (now referred to as the "old museum"). |

|

|

| |

Bronze coin of Kos with the snake

symbol of Asklepios. Circa 20-10 BC.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. N122. |

|

Bronze coin of Kos with a snake-entwined

staff, a symbol of the Asklepios cult. Circa

20 BC - 10 AD, reign of Emperor Augustus.

On the obverse side is the laureated head

of Augustus and the Greek inscription

ΣΕΒΑΣΤΟΣ (Sebastos).

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. N304. |

|

| |

A bronze coin with the head of Asklepios in

profile, facing right, wearing a laurel wreath.

Kos mint. 10 BC - 10 AD, reign of Augustus.

Obverse side: Head of Augustus, facing right.

Casa Romana archaeological site, Kos.

Inv. No. N1442. |

|

A bronze coin with the head of Asklepios in

profile, facing right, wearing a laurel wreath.

Kos mint. 10 BC - 10 AD, reign of Augustus.

Obverse side: Head of Augustus, facing right.

Casa Romana archaeological site, Kos.

Inv. No. N1443. |

|

| |

The inscribed marble pedestal from the monument to the Koan Gaius

Stertinius Xenophon (circa 10 BC - 54 AD), personal physician to Roman

Emperors Tiberius (reigned 14-37 AD) and Claudius (reigned 41-54 AD).

It was later alleged that he was involved in the murder of Claudius with

poison, said to have been instigated by the emperor's fourth (and final)

wife Julia Agrippina (Agrippina the Younger, 15-59 AD), mother of his

successor Nero (Tacitus, Annals, Book 12, chapter 67).

Roman Imperial period, 1st century AD.

Asklepieion archaeological site, Kos. |

|

A fragment of a marble stele inscribed with a letter

from Emperor Nero (reigned 54-68 AD) to the city

of Kos, mentioning Gaius Stertinius Xenophon.

Shortly after 54 AD.

Epigraphical pavilion, Asklepieion archaeological site, Kos.

Inv. No. E 514. |

|

| |

Surgical instruments found in the northwest sector of the ancient city of Kos,

2nd - 3rd century AD, Roman Imperial period. According to the museum

labelling, the functions of the instruments (from left to right) were:

Forceps for applying caustic to uvula; spoon for measuring,

preparing and pouring medicaments; forceps for removing uvula.

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

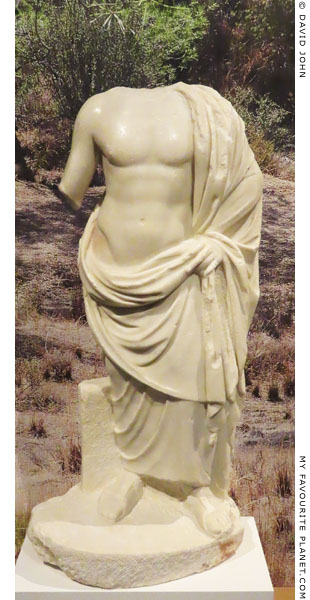

Restored marble statue of Asklepios.

2nd century AD. From Rome. [14]

Height 117.5 cm, with plinth 124.5 cm.

Height of head 19 cm.

Antikensammlung, Berlin State

Museums (SMB). Inv. No. Sk 71.

The room in the Pergamon Museum

in which it usually displayed is closed

until 2019 due to rebuilding work. |

|

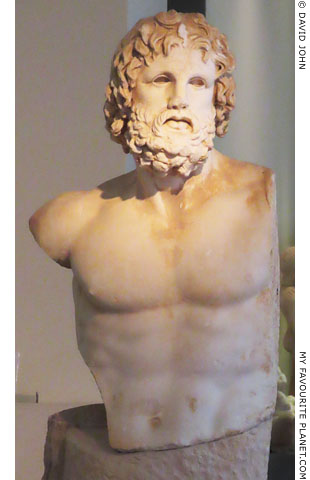

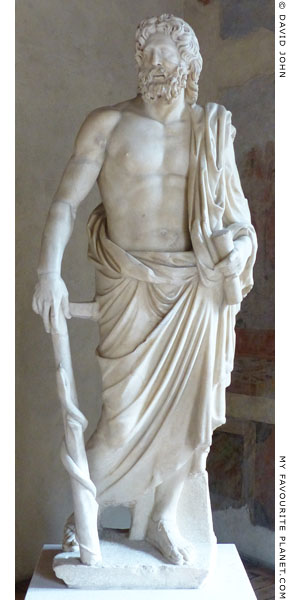

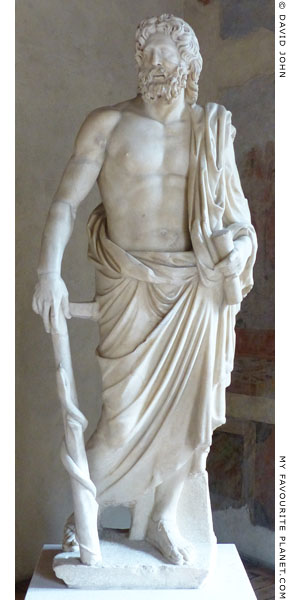

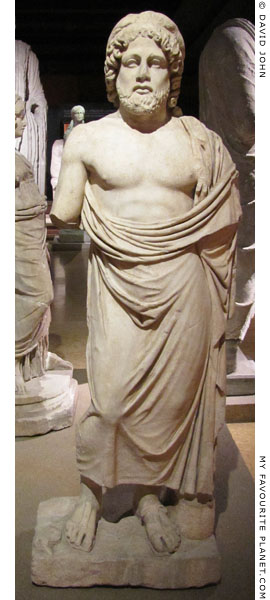

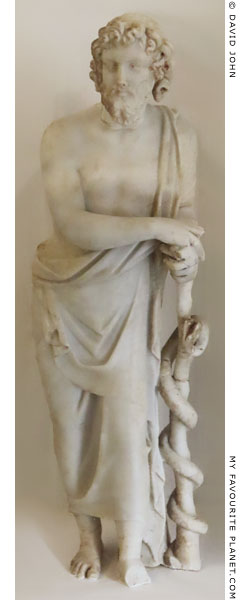

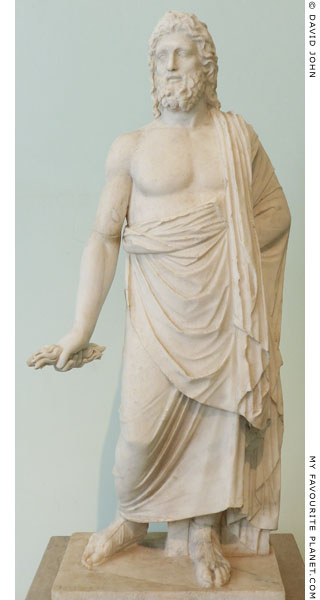

Marble statue of Asklepios

of the "Chiaramonti type".

2nd century AD Roman copy of a Hellenistic Greek original. The right arm and snake-entwined staff are modern additions.

There were several places in Rome

dedicated to the cult of Asklepios,

including the Esquiline Hill and the

Tiber Island (see below).

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum

of Rome. Inv. No. 8645.

Boncampagni Ludovisi Collection. |

|

| |

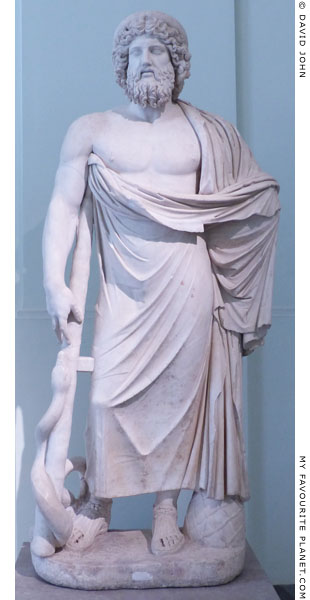

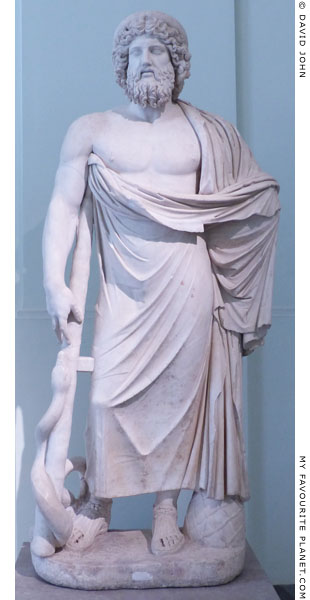

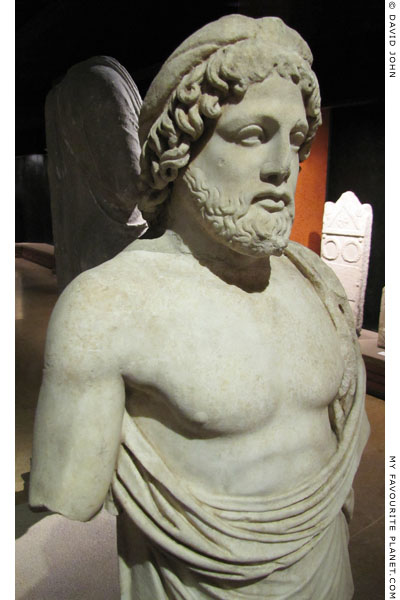

Marble statue of Asklepios of the "Giustini type",

named after a torso of the god now in the

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Late 2nd century AD reworking of an early

4th century BC Greek original attributed to

Alkamenes. Found in the 16th century on the

Tiber Island, Rome, the location of the city's

first sanctuary of Asklepios (see below).

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6360. Farnese Collection. |

|

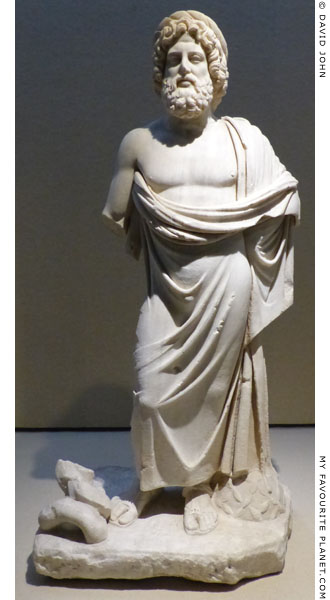

Restored marble statue of Asklepios

of the "Giustini type".

The Roman period head, mid 2nd century AD,

and the body are from separate statues.

Both have been extensively restored.

Purchased in Rome in 1766 by Ludovico

Bianconi for Friedrich II of Prussia. Height

with modern base (Carrara marble) 213.5 cm.

The Rotunda, Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 69.

Formerly in the gardens of the Neues Palais,

Sanssouci, Potsdam, where a 19th century

copy now stands see below. |

|

| |

The Giustini type, one of around seventeen types of Asklepios statue, is named after a statue in the Centrale Montemartini (previously in the Palazzo Nuovo) of the Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 1846. Its head, right arm and staff are now missing, as is the Omphalos beside the god's left foot seen on other statues of the type. Probably made during the reign of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD), it is thought to be a replica of a Greek work of the late 5th or early 4th century BC. The original was at first attributed to Alkamenes, on the basis of a brief mention by Pausanias of a statue of Asklepios in a temple at Mantineia in Arcadia, Peloponnese, that the healing god shared with Apollo, Artemis and Leto (the "Apollonian Triad"; see Nike).

"The Mantineans possess a temple composed of two parts, being divided almost exactly at the middle by a wall. In one part of the temple is an image of Asclepius, made by Alcamenes; the other part is a sanctuary of Leto and her children [Apollo and Artemis], and their images were made by Praxiteles two generations after Alcamenes. On the pedestal of these are figures of Muses together with Marsyas playing the flute."

Pausanias Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 9, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

The type was also associated with a statue group of Asklepios with his family at the sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia on the south slope of the Athenian Acropolis, also mentioned by Pausanias (see quote above). However, he did not describe either statue of the god, making identification based on these brief mentions purely a matter of speculation. According to a more recent theory the original may have been made by a Peloponnesian artist between 420 and 380 BC.

A description of the "Giustini type" statue of Asklepios in Naples (Inv. No. 6360, photo above left):

"The god, clad in a himation, lays his right arm (a restoration) on his club, round which a snake is curled. At his left side is a low Omphalos, this being his attribute as Apollo's son. A picture of perfect health, he stands calmly in an attitude that recalls the school of Phidias.

Alkamenes is generally named as the inventor of this type. In 420 B.C. he made a statue of Aesculapius for Mantineia and perhaps a replica of it for Athens where the cult of the god had been introduced from Epidaurus."

Giulio De Petra (and others, as editors), Illustrated guide to the National Museum in Naples, sanctioned by the Ministry of education. page 27. Richter & Co., Naples, 1897 (?). At the Internet Archive.

The "club" is usually referred to as a staff or crutch. Other modern writers have described statues of the type more thoroughly, noting particular (and often slight) differences in details between the figures, such as pose, positions of limbs and folds in the himation (cloak). Variants of the Giustini type include the Giustini-Neugebauer (see below), Amelung and London-Eleusis sub-types. Another distinctive feature of the statues, though not restricted to this type, is the corona tortilis, a circular, rolled crown worn around the top and back of the head.

The Giustini type, including its variants, is one of the most common types of figures of Asklepion known, particularly in Greece. Many of the statues, statuettes and fragments found in Athens, particularly in the Agora, are of this type as well as 16 of the 29 known freestanding marble figures of Asklepios from the Epidauros sanctuary. Examples have also been found in Italy, north Africa and Anatolia. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Marble statue of Asklepios of the "Giustini type", wearing the

corona tortilis and with the omphalos next to his left foot.

From Kabia (Καβαια) on the Sangarios river, Bythinia (Geyve, Sakarya province, Turkey).

Roman period, 1st century AD. Described on the museum label as "statue of male".

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4910 T. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Marble statuette of Asklepios of the "Giustini-Neugebauer type",

wearing a corona tortilis, with the omphalos next to his left foot.

From Syracuse (Greek, Συράκουσαι; Italian, Siracusa), Sicily.

Roman period, 2nd century AD, copy of an early 4th century BC

Greek original. Height 105.7 cm, with plinth 111.3 cm.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 696.

|

|

Found on 7th December 1803 in the area of the so-called "Nymphaeum of Venus", near the hospital, in Achradine (Ἀχραδίνη, wild pear trees), a suburb of ancient Syracuse north of Ortygia, which contained the agora, a temple of Asklepios and temples of Demeter and Persephone (see Demeter and Persephone part 1). It was unearthed by the Catanian archaeologist and natural historian Saverio Landolina Nava (1743-1814), who was the Royal Custodian of Antiquities for the areas of Val Demone and Val di Noto in southeastern Sicily. His discovery of this statue and that of the "Venus Landolina" [15] just a month later, on 7th January 1804, excited local public interest in the ancient history of Syracuse and helped spur initiatives to form an archaeological museum in the city.

See: Santino Alessandro Cugno, Il collezionismo archeologico siracusano tra XVIII e XIX secolo e la nascita del primo Museo Civico, page 63. At academia.edu. |

|

| |

Marble statue of Asklepios, head, right

arm and lower right arm now missing.

2nd century AD, roman Imperial period.

From Chalkis, Euboea, central Greece.

On the island of Euboea Asklepios was

also worshipped at Eretria and Styra.

New Archaeological Museum

"Arethousa", Chalkis. |

|

Marble statue of Asklepios, head

and lower right arm now missing.

2nd century AD. Excavated at Kourion

(Κούριον; Latin, Curium; modern Episkopi,

Επισκοπή) on the south coast of Cyprus.

Kourion Archaeological Museum, Episkopi.

Exhibited in the exhibition Cyprus - Eiland

in beweging (Cyprus - a dynamic island),

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden,

11 October 2019 - 15 March 2020. |

|

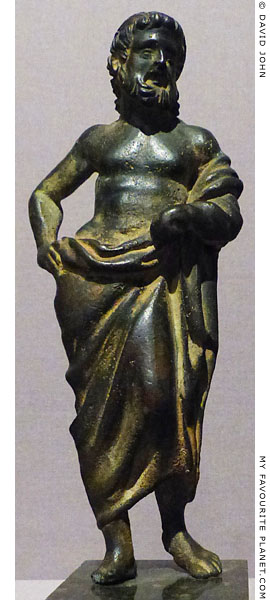

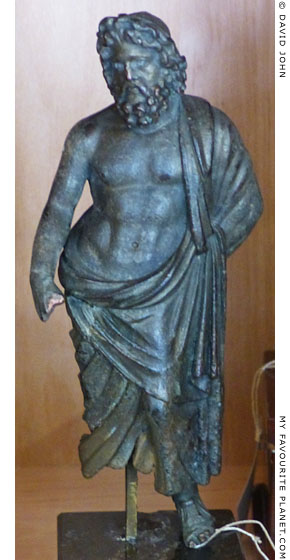

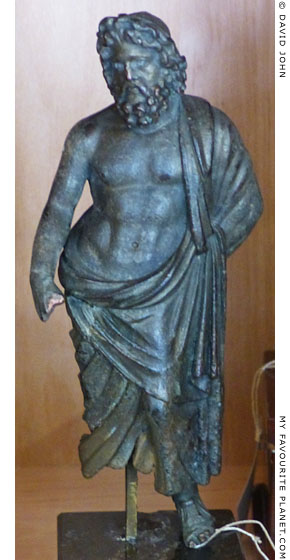

Bronze statuette of Asklepios.

Studiendepot Antike, Albertinum,

Dresden. Inv. No. Z.V. 493. |

|

| |

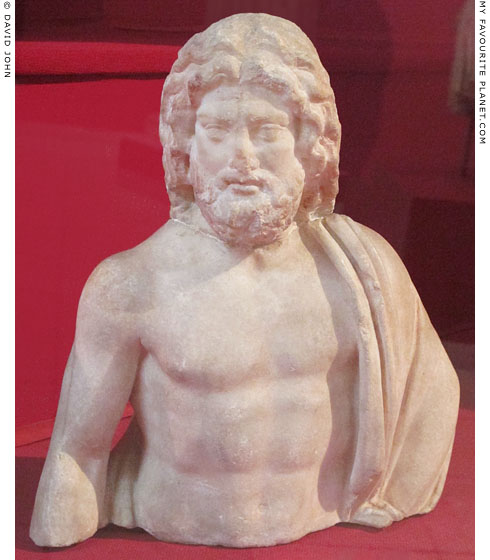

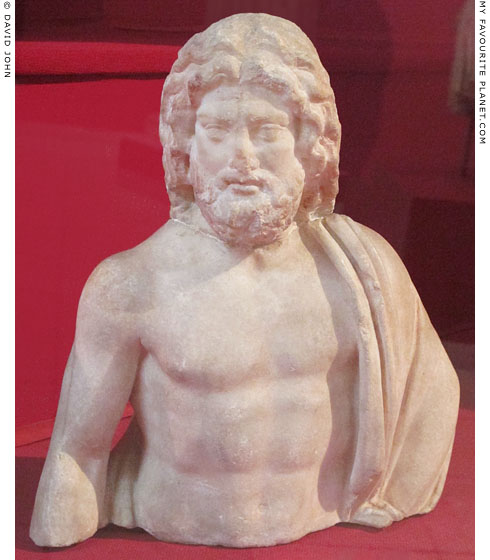

Part of a colossal statue of Asklepios of the "Mouynchia type".

Luna marble (northern Italy). 1st - 2nd century AD, Roman period

copy of a 2nd century BC Hellenistic original. From the Isthmus of

Ortygia, Syracuse, Sicily. Height 154 cm, width 90 cm, depth 37 cm.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 737.

|

The statue was found among other antiquities during the excavation of the Spanish Walls of Ortygia in 1560, and was kept until 1810 in the Castello Maniaca. Since the identity of the statue was unknown (Zeus, Poseidon, Hermes and Timoleon were suggested), it was named "Don Marmoreo". The Spanish inscription on the chest commemorates the dedication of the castle to Sant Iago (Saint James), and of the four angular towers to the patron saints of the city (Peter, Catherine, Philip and Lucia), as well as the granting of permission to fire cannon salvos during Sant Iago's festival.

A plaster cast is on display in the Castello Maniaca, Ortygia, Syracuse, made for the exhibition to celebrate the restoration of the castle in 2008. The construction process included cooperation between archaeologists and information technicians from Catania University to create a 3D model of the fragile sculpture using laser scanning techniques. |

|

| |

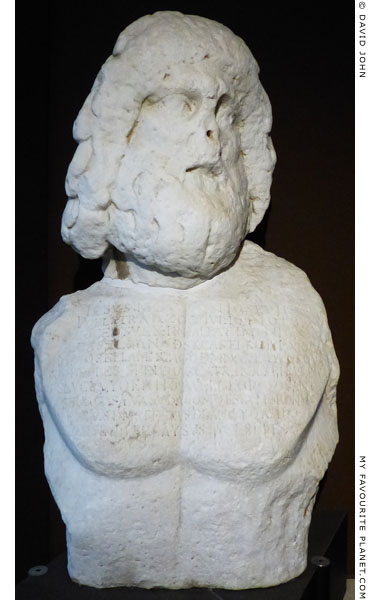

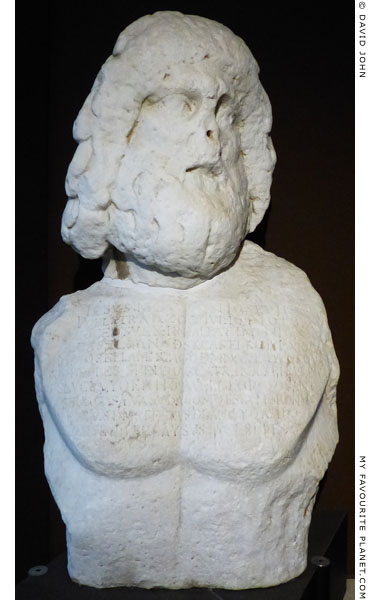

Unfinished bust of Asklepios or Serapis from the Asklepieion of Delos.

Hellenistic period.

Delos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. A 4023.

|

The Asklepios cult arrived at Delos around 100 years after it was established in Athens in 420 BC (see above). The Delian Asklepieion was built between the end of the 4th and the mid 3rd centuries BC, at the Bay of Fourni on the west coast of the island, quite a way south of the Sanctuary of Apollo and the residential districts. The area has not yet been thoroughly excavated, but ruins have been discovered of a propylon, an oikos, and a Doric tetrastyle temple.

There was also a small sanctuary for Esmun-Asklepios, one of the Syrian-Greek syncretic deities, including Baal-Poseidon and Astarte-Aphrodite, worshipped by a guild of merchants, shipowners and warehouse owners from Beirut, at their guildhouse, known as "the House of the Poseidoniastai of Beryttos" (or "Koinon of the Poseidoniasts of Beirut", first half of the 2nd century BC), north of the Sanctuary of Apollo. (See also a statue group of Aphrodite, Eros and Pan from the house, on the Pan page.) |

|

| |

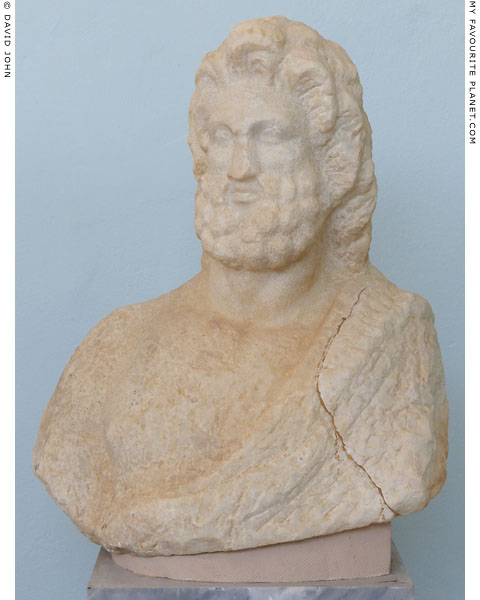

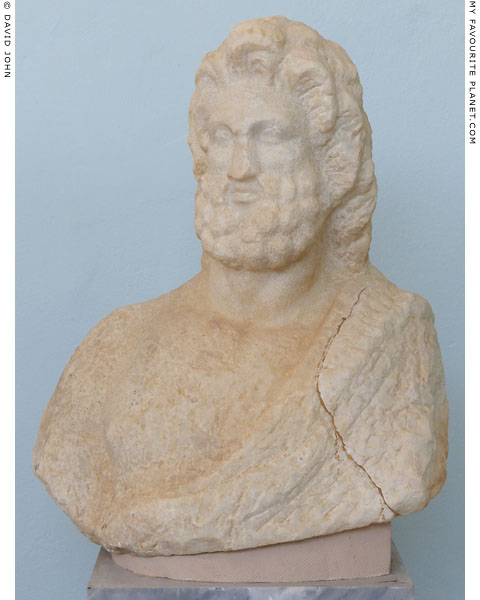

Upper part of a marble statuette of Asklepios.

Roman period. Found in 1928 in the Vedius Gymnasium, Ephesus.

White crystalline marble. Height 36 cm, width 27 cm, depth 16 cm.

There is thought to have been an Asklepieion in Ephesus, although its

location has not yet been discovered (see Ephesus gallery page 62).

However, it is known that doctors such as Galen of Pergamon were

employed to treat gladiators (see Pergamon Gallery 1, page 35).

Izmir Museum of History and Art. Inv. No. 640. |

| |

Part of a marble stele inscribed with a decree by the people of

Rhodes (the demos) concerning the arrangement of dedications

in the sanctuary of Asklepios in the city of Rhodes. From the

inscription it is clear that the sanctuary, also known from literary

sources, was built on a succession of terraces in a similar way

to the Asklepieion of Kos.

First half of the 3rd century BC. Found in the Medieval moat near

the Gate of Agios Athansios at the south of Rhodes Old Town,

where further inscriptions relating to the Asklepios cult and the

Asklepieion have been subsequently discovered, and where the

sanctuary may have been located. It is hoped that the area will

be excavated sometime in the near future.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum.

|

|

A now headless marble statuette of Asklepios

from the city of Rhodes.

Late 2nd - early 1st century BC.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum.

|

Both these objects are currently (2022) part of the extended exhibition

"Ancient Rhodes - 2400 years" in the Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes. |

|

| |

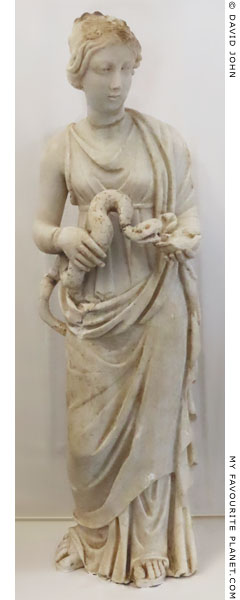

Marble statuette of Asklepios holding

a snake-entwined staff in Rhodes.

Mid 2nd century AD. This statuette and

that of Hygieia (photo, right) appear to

belong together. Unfortunately, the

museum labelling provides no information

concerning their history or provenance.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

|

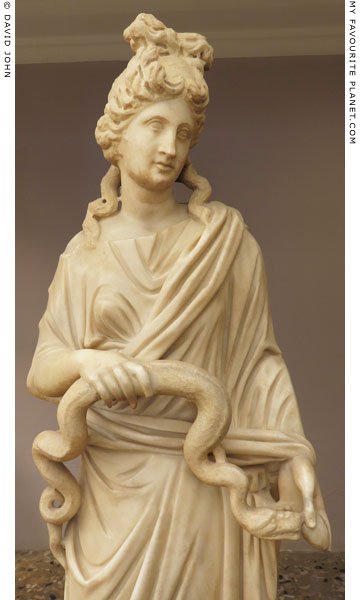

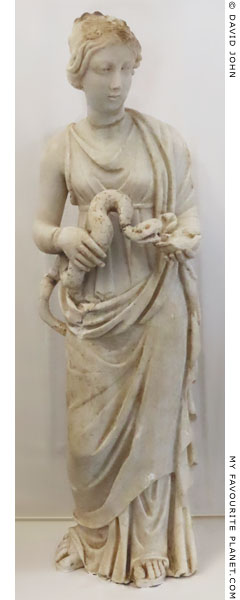

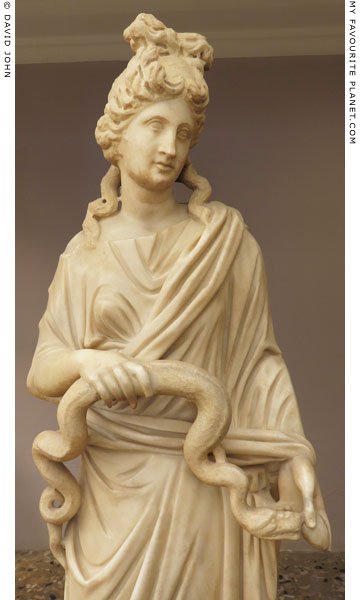

Marble statuette of Hygieia in Rhodes.

Mid 2nd century AD.

The goddess wears a himation (cloak)

over a long chiton (tunic). In her right

hand she holds a large snake which

eats or drinks from the bowl (now

broken) in her left hand.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

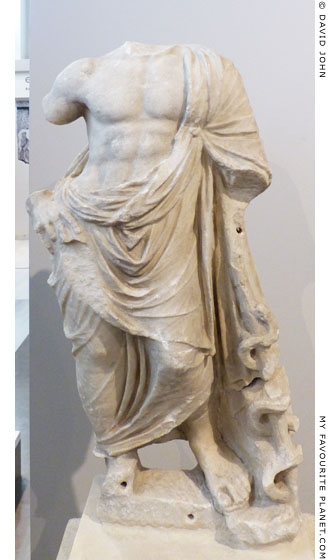

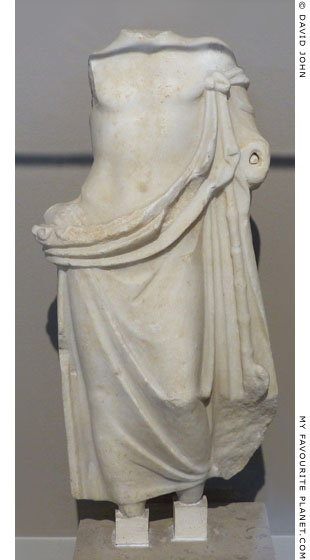

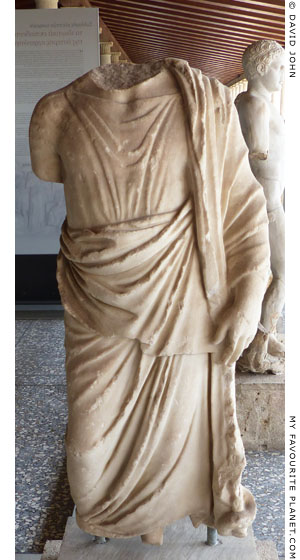

Marble statuette of Asklepios, the head, lower

left arm, right arm and feet of which are now

missing. The work is of the type known as the

Akragas Asklepios or Doria Panfili (or Doria

Pamphili) Asklepios. The original is thought to

have been made by a Peloponnesian artist

around 370-360 BC.

The type is named after the Villa Doria Pamphili,

Rome, where the best-preserved example is

kept. [16] As with a number of other statue

types, the deity is shown wearing a himation

which leaves his right shoulder and most of

his upper torso free to just below the navel.

In this type the himation appears to have

slipped off his left shoulder leaving it bare,

and seems to be kept from slipping further

only by the pressure produced by the arm

being held tightly to the side of the torso.

In the Villa Doria Pamphili statue the god's

staff or crutch can be seen supporting the

cloth. In front of the armpit is what appears

to be a knot or a bunching of the material.

The himation of this type covers the legs

only down to around the mid-calves.

Found in the andron (men's dining room) of

House B vi 7 in Olynthos, Halkidiki, Macedonia.

4th century BC, before the destruction of the

city by Philip II in 348 BC (see History of

Stageira part 6). This is the earliest known

depiction of Asklepios in marble from a

domestic setting. Height circa 35-40 cm.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. MΘ 226. |

|

|

|

| |

Fragment of a marble statuette of Asklepios

with a red himation. The red colour may have

been a base for the application of gold leaf

(see the statuette from Corinth below).

2nd half of the 2nd century BC

after a model of the 4th century BC.

Height 40.5 cm, width 21 cm, depth 10.5 cm.

Found on the Dodecanese island of Kos,

one of the most important asklepieion

healing centres and the birthplace of the

most famous ancient Greek physician

Hippocrates (Ἱπποκράτης, circa 460-370 BC).

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden.

Inv. No. Hm 215 (formerly ZV 966). Purchased

in Munich in 1891 from a private individual.

See also a head of Asklepios from Kos below. |

|

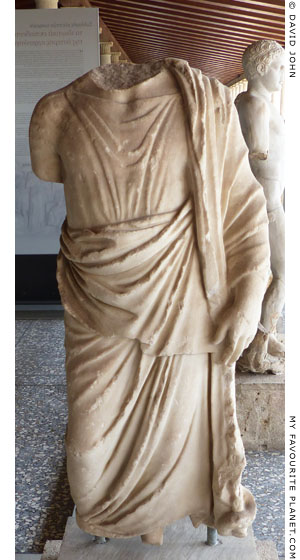

Fragment of a marble statue of Asklepios

from the Asklepieion at Thespiai (Θεσπιαί),

Boeotia, central Greece.

Roman period, perhaps 2nd century BC.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

A snake, a symbol of Asklepios, on the reverse side of a marble imago clipeata bust

of Emperor Hadrian from Thespiai (Θεσπιαί), Boeotia, central Greece (see photo and

article on the Medusa page). The symbol may refer to the Asklepieion at Thespiai.

Mid 2nd century AD.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

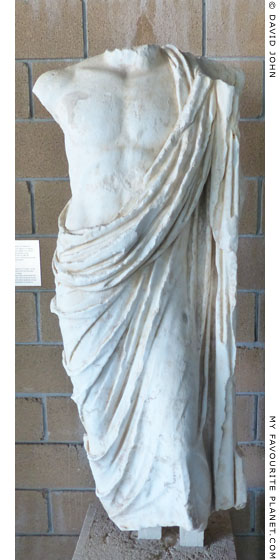

Fragmentary marble statuette of Asklepios

of the Este type, depicting the god holding

a snake-entwined rod.

1st century BC. From Ano Apostoloi,

Kilkis (ancient Morrylos), Macedonia,

Greece. Height 74 cm.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. ΜΘ 947+1165. |

|

Fragment of a small marble statue

of Asklepios-Serapis. [17]

2nd century AD. Found in 7th century AD

destruction debris over the "Omega House",

north slope of the Areopagos, south of the

Athens Agora, 25 May 1938. Height 84 cm,

width circa 37 cm, depth circa 18.5 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 1068. |

|

| |

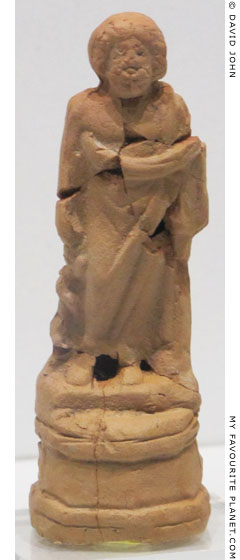

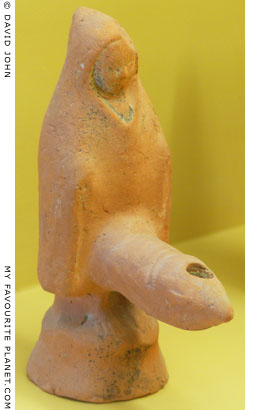

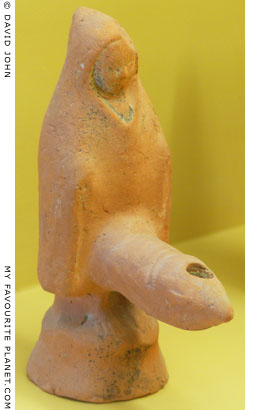

Terracotta votive figurine of

a statue of Asklepios from

the Pergamon Asclepieion.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

Reverse side of a bronze coin from Pergamon

showing Asklepios holding a snake-entwined

staff and Artemis of Ephesus.

Inscription: EΠI CEΞ KΛ - CEIΛI/ANO/

V - ΠEPΓ-AMHN-ΩN // KAI EΦECIΩN / OMON.

Minted during the reign of Emperor Gallienus,

(253-268 AD) by the Asiarch (magistrate)

Sextus Claudius Silianus. The obverse side

shows a bust of Gallenius, facing right,

wearing a laurel wreath and cuirass, and

the inscription: AVT K Π ΛIKI - ΓAΛΛIHNOC.

Diameter 37 mm, weight 27.26 grams.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. 18200358.

Acquired in 1873 with the entire collection

of General Charles Richard Fox. |

|

| |

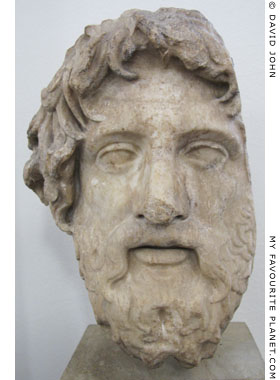

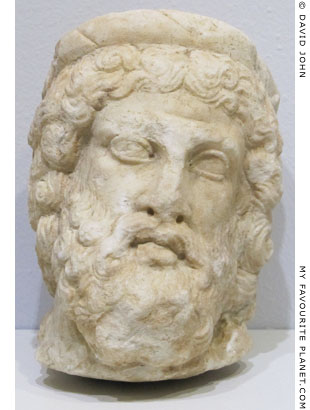

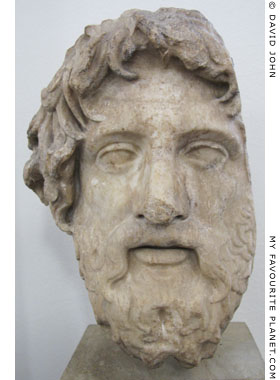

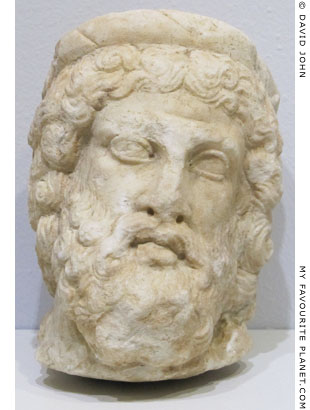

Marble head of a statue of Asklepios.

Around 400 BC. From Rome.

Height 29.8cm, width 22 cm, depth 20 cm.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 1832.

Purchased on the art market in 1829

by the Vereinigung der Freunde

der antiken Kunst as a gift to the

Antiquities Collection in Berlin. |

|

A terracotta mask of Asklepios.

From the Asklepieion of Ancient Corinth,

Greece. 4th century BC. Height 20.7 cm.

Found during excavation of the Asklepieion

and the adjacent resort of Lerna, 1929-1934,

supervised by Professor F. J. De Waele of

Nijmegen University, Netherlands, attached

to the staff of the American School of Classical

Studies at Athens (ASCSA).

Corinth Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. V40. |

|

| |

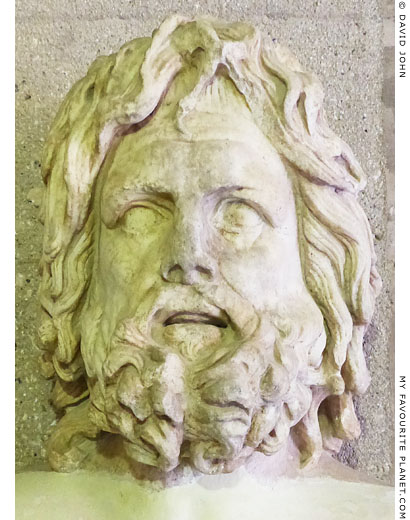

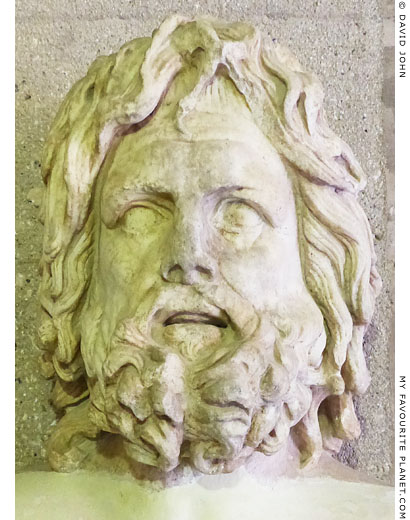

A larger than life-size marble head of

a colossal cult statue of Asklepios.

From the Cycladic island of Melos, Greece.

Hellenistic, around 325-300 BC.

Parian marble. Height 60 cm.

Found in the mid nineteenth century at the

Asklepieion on Melos, along with two votive

inscriptions dedicated to Asklepios and

Hygieia and a votive relief of a leg. It was

acquired by the French diplomat and

collector Louis, Duke of Blacas.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1867.5-8.115

(Sculpture 550). Purchased with the

entire Blacas collection in 1867. |

|

Marble head of Asklepios from a small statue.

As with a number of depictions of Asklepios,

the head appears to incline to the left.

From Kos. Circa 200-160 BC.

British Museum.

Inv. No. GR 1868.6-20.3 (Sculpture 1519). |

|

| |

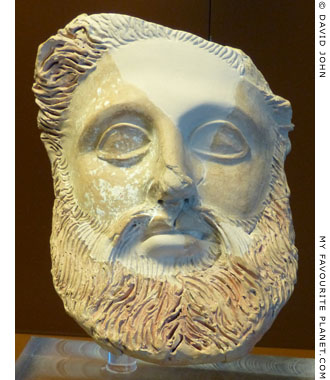

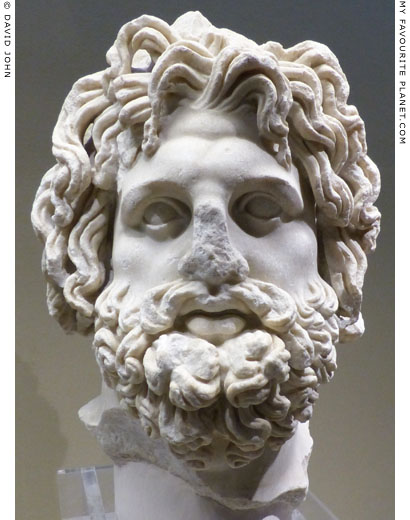

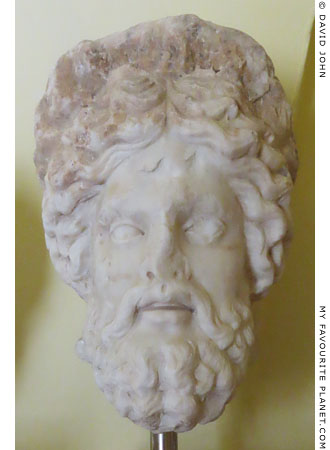

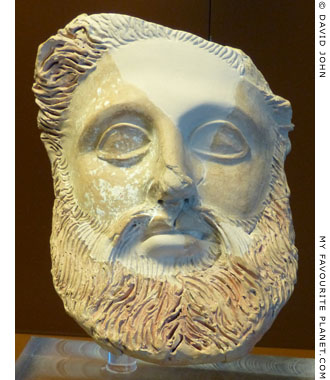

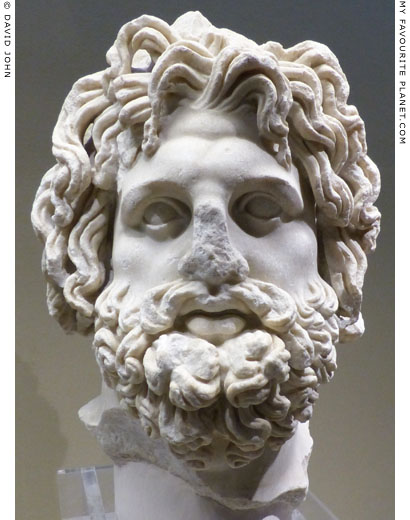

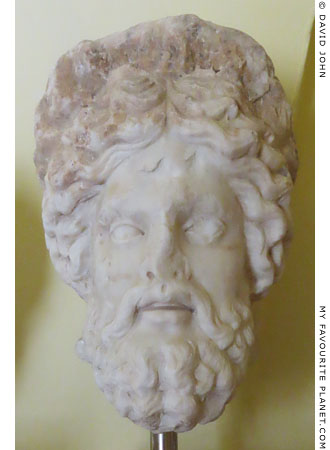

Larger than lifesize marble head of Asklepios.

1st century AD, Augustan period. Believed to be a copy of a

Hellenistic original made around 175 BC by the Athenian sculptor

Phyromachos (Φυρόμαχος) for the Asklepieion at Pergamon.

The sculpting style and technique have been compared to

those of figures on the Gigantomachy frieze on the Great Altar

of Pergamon (circa 175 BC). Found in 1804 at the ampitheatre

in Neapolis, Syracuse, Sicily.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum,

Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 693. |

|

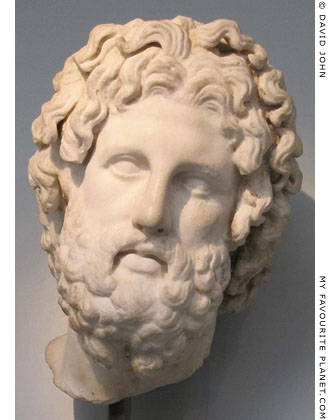

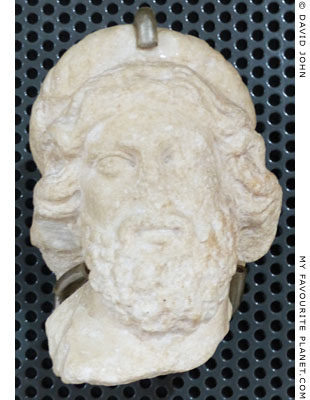

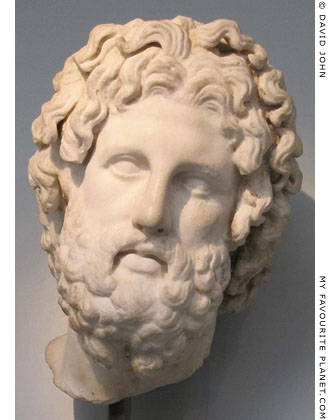

A marble head thought to be from a herm, found

in the Asklepieion of Ancient Corinth. Identified as

a head of the Zeus of Otricoli type, the original of

which is attributed to Pheidias.

Roman period.

Corinth Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. S 1433.

The Zeus of Otricoli type is named after an ancient marble

bust found in Otricoli in 1775, during excavations financed

by Pope Pius VI. It is believed to be a Roman period copy

of a Greek original of the Classical or Hellenistic period,

perhaps the chryselephantine statue of Zeus in Olympia

made by Phidias. Now exhibited in the Sala Rotonda,

Pio-Clementine Museum, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 257. |

|

| |

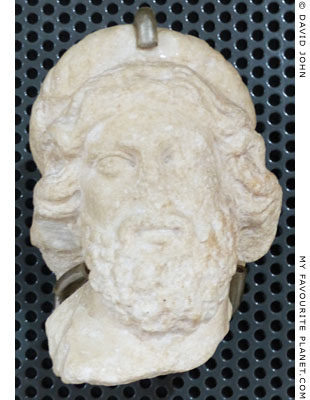

Small marble head of Asklepios

wearing the corona tortilis.

From Crete. 2nd century AD.

Pentelic marble. Height 7 cm.

Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 162. |

|

Small marble head of Asklepios from

the Yortanli Dam salvage excavation,

Allianoi, near Pergamon (see below).

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Small marble head of Asklepios from the

agora of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece.

2nd - 3rd century AD, Roman period.

Museum of the Ancient Agora of Thessaloniki. |

|

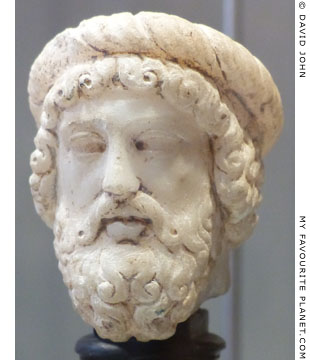

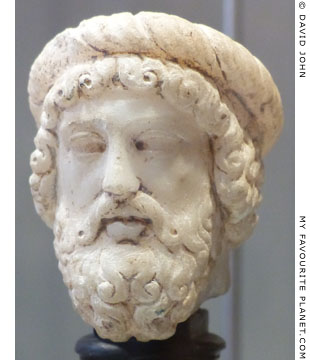

Marble head of a bearded male wearing

a crown, probably Asklepios.

Smaller than life-size. Roman period. Found on

the Mon Repos estate, Corfu, in the area now

known as Palaiopolis (Παλαιόπολης, Old City),

site of the ancient city Korkyra (Κόρκυρα).

Mon Repos Museum, Corfu. |

|

| |

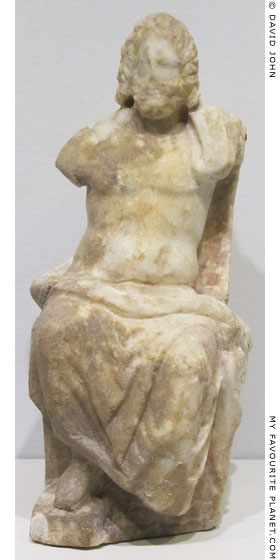

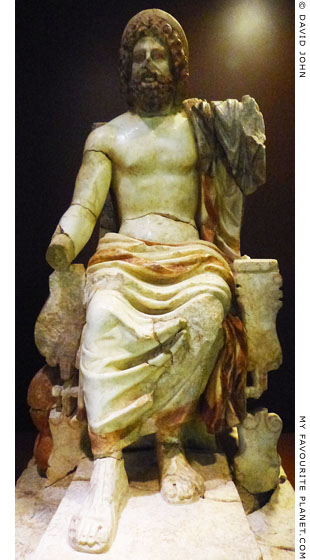

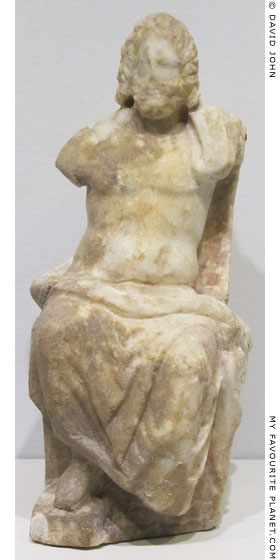

Marble figurine of enthroned Asklepios

from the Pergamon Asclepieion.

Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

|

A marble statuette of enthroned Asklepios.

The red colour was a base for gold leaf

From Corinth. 3rd - 4th century AD.

Height with base 42.3 cm,

height of figure 34.8 cm.

One of nine statuettes of deities, perhaps

small scale replicas of chryselephantine

cult statues, found in 1999 in the room of

a late Roman house, named the Panayia

Domus by archaeologists, southeast of

the Asklepieion of Ancient Corinth. [18]

It is thought that the worship of Asklepios

may have survived at Corinth well into

the Christian era, and although the area

around the Asklepieion was used as a

cemetery in the 6th - 7th century AD,

the site of the temple was not.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. S 1999 008.

See also a terracotta mask of Asklepios

from the Asklepieion of Ancient Corinth above. |

|

| |

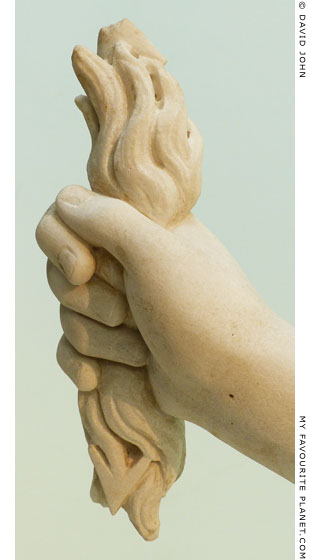

|

|

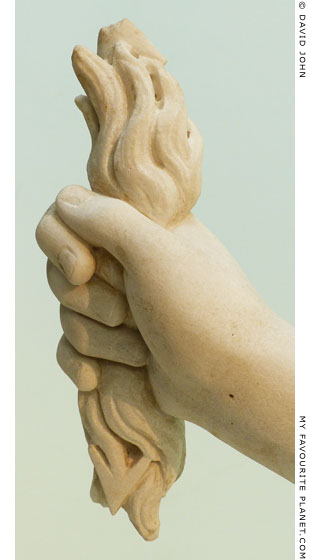

Zeus' thunderbolt |

Marble statue labelled as "Asclepius of the Anzio Type".

Late 2nd century AD copy of a late Hellenistic creation

inspired by a Greek original of the 4th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6265. From the Farnese Collection.

|

|

Although the statue is described as depicting Asklepios, an old catalogue of the Naples museum (around 1897) noted that both arms of the figure have been altered by modern restorers, including the addition of a new right forearm, hand and the thunderbolt, the characteristic attribute of Zeus. The join at the right elbow where the modern forearm has been added can be seen in the photo above.

It was later described in the officially sanctioned guide as: "Statue of Zeus with the thunderbolt. The arms are restored. This frequently recurring type is derived from Phidias. Poor execution." [19] The assumed connection with Pheidias is based on the identification of the restored figure as Zeus.

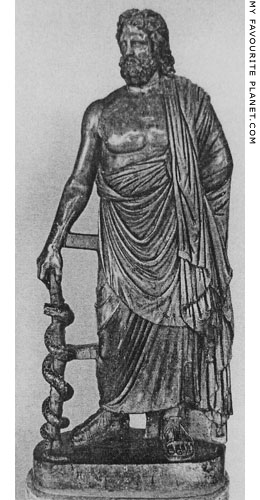

According to the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), four similar statues, also dated to the 2nd century AD, were found together in Anzio (ancient Antium) in 1718, during excavations funded by Cardinal Albani from 1711. Two of the works, made of dark grey bigio morato marble, were formerly in the Albani Collection and are now Capitoline Museums. After their discovery, one was restored as Asklepios with a staff and snake (photo, right), while the other (see photo below), like the statue above, was given a new right forearm and hand with the thunderbolt of Zeus, although it was described in the inventory of the Albani Collection as Aesculapius [20]. The entire straight left arm can be seen, whereas in the other two statues the left arm is bent, with the lower forearm behind the figure's back.

The three statues are almost identical, clearly depicting a god in Classical style, with the same hairstyle, beard, sandals, pose and stance, and with the himation (cloak) draped and folded around the body in the same way. The museums' labelling makes no mention of these alterations, and so far I have found no useful recent literature concerning these statues, but it appears that all three may have depicted Asklepios, but two have been restored as Zeus.

Unfortunately, at the time of my recent visit to the Capitoline Museums, the Asklepios statue (right) was on a long loan to another museum, so I have had to use a very old photo. |

|

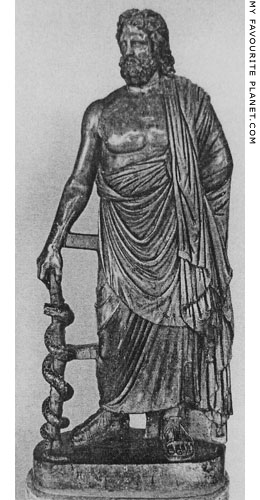

Bigio morato marble statue

of Asclepius, Anzio Type.

Circa 150 AD. From Anzio (Antium),

Italy. The right hand, part of the

staff and snake were added

during restoration. Height 144.5 cm.

Great Hall, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. MC 659.

From the Albani Collection. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Bigio morato marble statue of "Zeus" (see above) holding a thunderbolt.

Found in Anzio in 1718. 2nd century AD version of an early Hellenistic

original of the 4th century BC. Height 141 cm.

The statue stands on an ancient circular marble base with an

Archaistic relief depicting Hermes, Apollo and Artemis (see Hermes).

Great Hall (Salone), Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. MC 655. From the Albani Collection. |

|

| |

A small votive relief, which according to the museum label, depicts

"Asklepios holding the horn of Amaltheia, Hygeia, Podaleirios and adorants".

4th century BC. From Limani Pasha (Λιμάνι Πασσά, Pasha's Harbour),

between Lavrion and Sounion, southeast Attica, Greece. Agrilesa marble.

Lavrion Archaeological Museum.

|

It is not clear on what basis the figures in this relief have been identified as Asklepios, Hygieia and Podaleirios (a son of Asklepios), or why the rhyton (drinking horn) must necessarily be "the horn of Amaltheia" (the cornucopia). There appears to be no inscription or any of the usual identifying attributes. Many reliefs of this type discovered around the Greek world have been identified as nekrodeipno scenes (νεκρόδειπνο; named Totenmahlreliefs by German archaeologists), depicting a funerary banquet or symposium in honour of a deceased and possibly heroized person. Some are thought to represent Hades (Plouton) and Persephone. For further information, see the articles and photos in Demeter and Persephone part 2.

The ancient port at Limani Pasha (the modern name) belonged to the deme of Sounion and was an important commercial centre between the 4th and 1st centuries BC, trading agricultural products, metalwork and pottery. Remains of an agora and other buildings have been discovered there. |

|

| |

Fragment of a marble relief showing Athena and probably Asklepios on a stele

with part of an Athenian honorary decree (a proxeny decree) granting the title

of proxenos (πρόξενος, literally "instead of a foreigner"; an honorary consul)

and benefactor to a citizen of Croton (Κρότων, Kroton), southern Italy.

[θε]οί.

[ἐπὶ - ο]υ ἄρχοντο[ς]

[προξενία καὶ εὐ]εγεσ[ία - - - -]

- - - - - Κροτ[ωνιάτου]

[- - - - - -]

Inscription IG II² 406

From the Athens Acropolis. Around 330 BC.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. NAMA 2985.

(Previously in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.)

See also an Athenian proxeny decree for Sochares of Apollonia, Thrace. |

| |

Inscribed marble stele with a votive dedication to Apollo and Asklepios.

From Kalamoto (Καλαμωτο; ancient Kalindoia, Καλίνδοια), Thessaloniki prefecture, Macedonia, Greece.

334/333 - 304/303 BC. Height 138 cm,

maximum width 36.5 cm, depth 7 cm.

Dedicated by the priest Agathanor,

son of Agathon. 39 verses have

survived, mentioning the names

of all the priests from 334/333 BC

onwards in chronological order.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. ΜΘ 9220. |

|

Part of a marble block with an inscription in two

columns referring to the sanctuary of Asklepios

at Veria, Macedonia, Greece.

Second half of the 3rd century BC.

Height 75 cm, width 44 cm, depth 13 cm.

Veria Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. L 702. |

|

| |

Fragment of a marble stele inscribed with the sacred law

of the sanctuary of Asklepios in Amphipolis, Macedonia, Greece.

Around 350-300 BC. Height 27 cm, width 17 cm, depth 10 cm, letter height 1 cm.

Discovered by chance in spring 1965 during trial excavations in Amphipolis.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 94.

Inscription SEG 44:505 at The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI).

|

| As with many other sanctuaries of Amphipolis, the location of the city's Asklepieion has not yet been discovered. However, its existence has been proved by the discovery of numerous votive offerings, including statues of Asklepios and Hygieia (see below), figurines of Telesphoros (see below), and this fragment of its sacred law (lex sacra). The inscription states the requirements for incubation in the Asklepieion, the payment of one drachma to the priest by visitors to the sanctuary, the offering of voluntary sacrifices, the portion given to the god on the altar, and the offering of sacrifices to other gods in this sanctuary (possibly Apollo, Hygieia and Telesphoros). |

|

| |

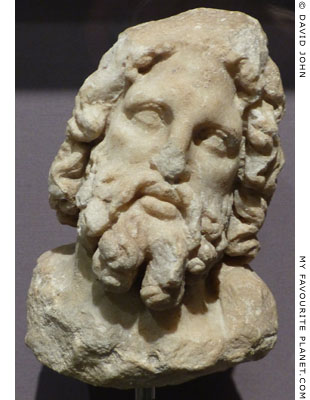

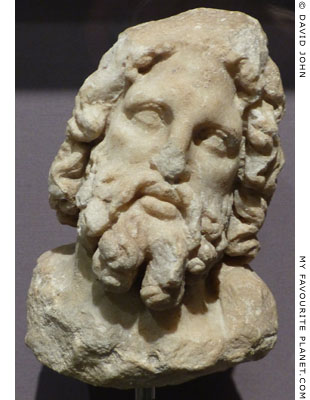

A marble head of a statue of Asklepios

wearing the corona tortilis from Amphipolis.

1st - 2nd century AD, Roman period

copy of a 4th century BC original.

Height 22 cm, width 16 cm.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 110. |

|

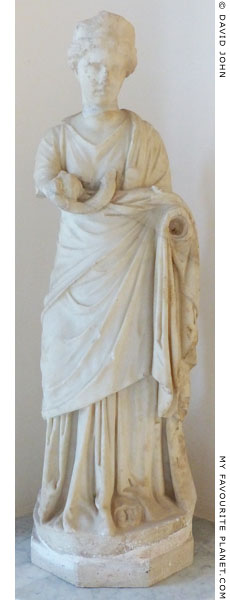

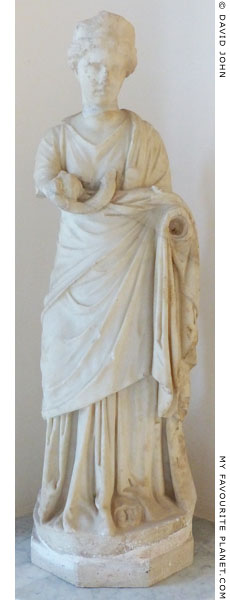

A marble statue of Hygieia (Ὑγιεία),

goddess of health, daughter of

Asklepios. From Amphipolis. Part

of a snake's body can be seen on

her left shoulder.

Roman Imperial period.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 924. |

|

| |

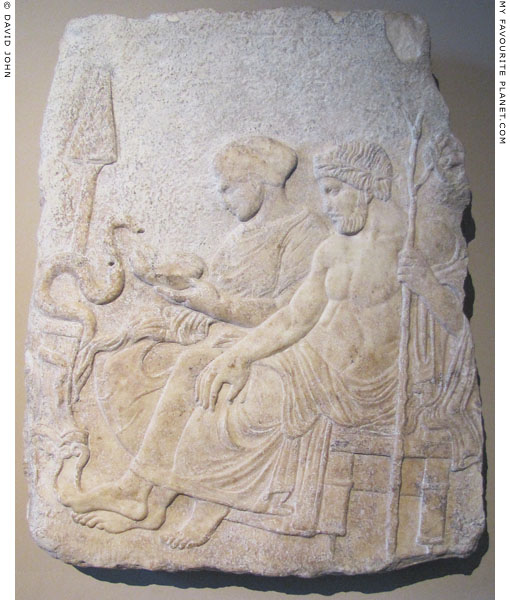

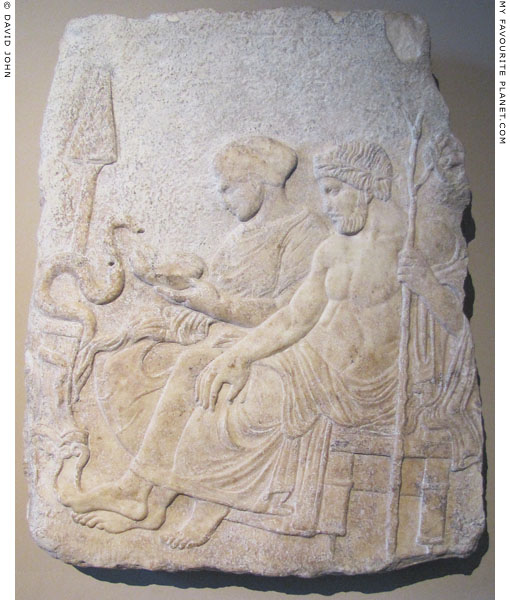

Marble relief depicting the healing god Asklepios seated

with his daughter Hygieia (Ὑγιεία), goddess of health.

In some versions of myths Hygieia is the wife of Asklepios.

Classical period, last quarter of the 5th century BC. From Therme, Macedonia,

Greece. Therme was the ancient name of Thessalonike (Thessaloniki) before

it was renamed by King Cassander of Macedonia, in 316/315 BC (see

History of Stageira and Olympiada part 6). The relief was sent to Istanbul

in 1871 by Sabri Pasha. Height 61 cm, width 40 cm (top) - 52 cm (bottom).

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 109 T. Cat. Mendel (Volume I, 1912) 91. |

| |

Hygieia (left) and Asklepios on a coin of Corinth, issued 161-169 AD,

during the reign of Lucius Verus (130-169 AD), co-Emperor with his

adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius.

Many coins of Corinth during the Roman Imperial period depicted the current

emperor or empress on the obverse side, and on the reverse either Asklepios

or Hygieia alone, or both divine healers together, as in this case. It has been

suggested that these figures represent the marble statues in the temple

of the Corinthian Asklepieion mentioned by Pausanias:

"Above the theatre is a sanctuary of Zeus surnamed in the Latin tongue

Capitolinus, which might be rendered into Greek 'Coryphaeos' (Κορυφαῖος).

Not far from this theatre is the ancient gymnasium, and a spring called Lerna.

Pillars stand around it, and seats have been made to refresh in summer time

those who have entered it. By this gymnasium are temples of Zeus and Asclepius.

The images of Asclepius and of Hygieia are of white marble, that of Zeus is of bronze."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 4, section 5.

At Perseus Digital Library.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

A marble votive relief for Asklepios from the Asklepieion in Piraeus. Around 350 BC.

Asklepios places his hands on the right shoulder of a woman patient, lying on her

side on a couch. To the right, Hygieia stands behind him, and on the far left four

members of the patient's family, three adults and a child, approach as suppliants.

Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 405. |

| |

Marble votive relief depicting Asklepios, Hygieia and worshippers.

From Attica, Greece, 330-320 BC.

The relief in the form of a naiskos (ναΐσκος, small temple), with antae (side walls) or pillars on both sides

supporting an epistyle (architrave). Epistyles on such reliefs often bore a dedicatory inscription,

as on many temples and public buildings. The head of a coiled snake appears from beneath the

god's throne. To the right is a family of worshippers, the dedicators of the relief.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 685.

Acquired in 1827 from the Ingenheim Collection. |

| |

A marble votive relief in the form of a naiskos, dedicated to Asklepios.

From Patras, northwestern Peloponnese, Greece. 4th century BC.

The scene on the relief contains eleven figures. Asklepios stands on the far left, next to

him stands a female, thought to be his wife Epione (Ἠπιόνη, Soothing), and two heroically

naked males, perhaps two of his sons, Machaon (Μαχάων) and Podaleirios (Ποδαλείριος).

The family of the hekete (suppliant) approach an altar in the centre from the right, bringing

a pig as a sacrifice. The inscription on the epistyle (architrave) has not beeen preserved.

Patras Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Terracotta votive relief of a family with children (left) standing before Asklepios (centre),

two of his sons and Hygieia (far right). 4th century BC. Height 40 cm, width 58 cm.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1984.111. |

| |

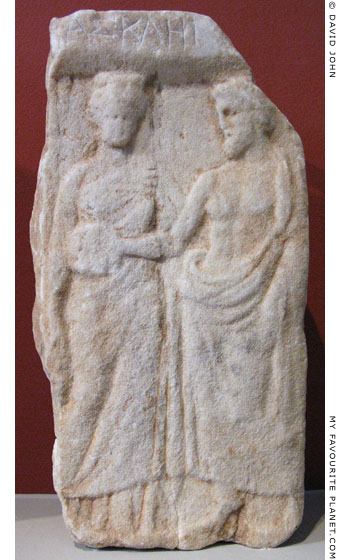

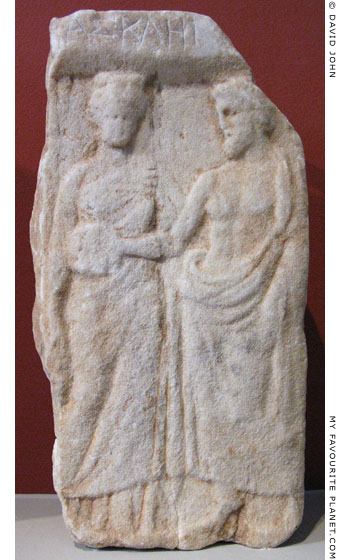

Inscribed marble votive relief dedicated

to Asklepios and his daughter Hygieia.

Unknown provenance. Around 350-330 BC.

Height 47 cm, width 26 cm, depth 13 cm.

The first letters of the name Asklepios, ΑΣΚΛΗΠ

(ASKLEP) are inscribed above the figures.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 10425. |

|

|

|

| |

A marble relief of Asklepios and Hygieia.

On the left, Asklepios, facing right, seated on a klismos placed on a dais or plinth. He places

his left hand over the raised head of a large snake, the body of which is coiled beneath the

god's chair. Hygieia stands on the right, facing him. With her right hand she pours a libation

from an oinochoe (jug) into a bowl in her left hand. Is the libation for the god or the snake?

The image illustrates the perceived superiority of Asklepios over his "daughter", the worship

of whom at places like Athens predated the introduction of the Asklepios cult.

Roman period, 1st century AD, after Attic reliefs of the Classical period, 4th century BC.

From Italy. Rough-grained, yellowish white marble. Part of Hygieia's lower left arm and

the bowl have been restored with marble. Height 52 cm, width 53.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden. Inv. No. 1882: AMM 2. |

| |

A small statue of a child seated on the ground, holding a bird with both hands,

as if strangling it. Possibly a symbolic representation of one of Asklepios' children.

3rd century BC. From the village of Imeros, near Lake Ismaris, Macedonia, Greece.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ80. |

| |

Marble statue group of six children of Asklepios (left-right):

Machaon (Μαχάων), Hygieia (Υγεία), Aigle (Αίγλη),

Panakeia (Πανάκεια), Akeso (Ακεσώ) and Podaleirios (Ποδαλείριος).

From the Great Baths, Dion, Macedonia. 2nd century AD.

Dion Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Marble head of a female member of

the family of Asklepios, perhaps his

wife Epione (Ἠπιόνη, Soothing).

From a marble basin for holy water

in the Great Baths, Dion, Macedonia.

2nd century AD.

Dion Archaeological Museum. |

|

Marble statuette of Hygieia from Dion, Macedonia. Part of a snake can be

seen on her right shoulder.

1st century AD. Height 45 cm.

Dion Archaeological Museum

Inv. No. 298. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Marble statue of Hygieia.

Roman period copy after a Greek original dated 290 BC. Pentelic marble.

Height (including plinth) 142 cm. Found in 1878 in the area of the Auditorium

in the Horti Maecenatis, Esquiline Hill, Rome. [21]

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 1099. |

|

| |

|

|

|

A marble statue thought to depict either Hygieia or a wealthy Roman woman.

1st century BC. Found in the baths of ancient Aidepsos (Αιδηψός),

northwest Euboea (see a gravestone of a doctor from Aidepsos below).

New Archaeological Museum "Arethousa", Chalkis.

For further information about ancient Aidepsos, see the Antinous page. |

|

| |

Marble statuette of Hygieia wearing

a peplos, with a snake wound around

her torso.

Around 200 AD. Pentelic marble. Found in

the Sanctuary of Asklepios, Epidauros. The

inscription in Greek on the base states that

the sculpture was a thanks-offering from

Gaius to "Hygeia", referred to as "Iatra"

(the feminine form of iatros, doctor).

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 271. |

|

Marble statue of Hygieia

holding a snake.

1st - 2nd century AD. Thasian

marble. Found in 1936 in the

Baths of the Sette Sapienti,

Ostia, near Rome.

Ostia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 115. |

|

| |

A relief of Hygieia holding a snake on the capital of a marble pseudopilaster

from the Octagon of the imperial palace complex, Thessaloniki.

Made in a Roman imperial workshop in the city, early 4th century AD.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

See another pseudopilaster capital from the Octagon on the Dioskouroi page. |

| |

A marble slab inscribed with a dedication to Asklepios and Hygieia

and the city of the Morrylians (Morrylos), by Sosias, son of Sosipolis,

from the city Ioron (Ιωρον, perhaps modern Palatiano).

Late 1st century AD. From Ano Apostoloi, Kilkis (Άνω Απόστολοι Κιλκίς;

ancient Morrylos, Μόρρυλος), Macedonia, Greece.

Kilkis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. AEMK 262.

Here seen in the temporary exhibition Metropolis of the Morrylians,

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, 15 February - 31 December 2024. |

| |

A marble stele inscribed with an honorary decree in which Paramonos,

son of Samagoras (Παράμονος Σαμαγόρου) is honoured for offering

to the sanctuary of Asklepios a cow from which an entire herd was

started. The inscription provides information on local history and

the city's public institutions.

185-180 BC. From Ano Apostoloi, Kilkis (Άνω Απόστολοι Κιλκίς; ancient

Morrylos, Μόρρυλος), Macedonia, Greece. Discovered in 1961 during

excavations directed by Ph. Papadopoulou.

Kilkis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. AEMK 27.

Inscription Hatzopoulos, Mac. Inst. II 53 (also SEG 54:602(2)

and SEG 39.606) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Here seen in the temporary exhibition Metropolis of the Morrylians,

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, 15 February - 31 December 2024.

The long inscription is very worn and illegible in places, particularly lower down the stele, but the jist has been deciphered:

"Euxenos son of Samos, Menandros son of Holoichos, Nikanor son of Paramonos, the archontes proposed:

Because Paramonos son of Samagoras, had come to the Assembly of the People when Demetrius son of Sopatros was strategos (general), and had offered to the city and Asklepios a cow from his herd. Due to which and the large number of its offspring, in the fifteenth year, when Epinikos was strategos, although it was resolved by the city to award him with a crown of leaves, the then archontes did not transmit the decree with a document of their own, let it be resolved by the city of Morrylos, because he (Paramonos) acts towards them as a citizen without reproach and in all matters devotes himself to the common interest, that he be praised and awarded a crown of leaves, and to be permitted to erect himself a stele in the most prominent location of the sanctuary of Asklepios, in order that the other citizens, seeing that some gratification is granted to such men, be eager to adopt a similar behaviour, and that the decree be sent to the mnemon.

It was adopted on the 17th of Hyperberetaios." [22] |

|

| |

An inscribed marble votive relief, addressed to "Lord Plouton", with a

shallow relief depicting Hades and Persephone enthroned as rulers

of the Underworld, each holding a sceptre in the left hand. On the left,

in front of an altar, stand the healing god Asklepios, holding a staff

in his right hand, and Hermes Kerdoos (Κερδώος, profit-bringing) with

a kerykeion (caduceus) in his left hand and a purse in the right.

3rd century AD. Found around 1889 in the area of Nevrokopi (Νευροκόπι),

in the Rhodope Mountains. north of Drama, East Macedonia, Greece.

Height 53 cm, width 84 cm, depth 6.5 - 9 cm.

Drama Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 27.

|

This representation of Hades and Persephone resembles depictions of the Egyptian deities Serapis and Isis. Hades' face is no longer visible, but it is clear that his head is surrounded by a nimbus (halo). The faces of Asklepios and Hermes The faces of Asklepios and Hermes have also been worn away by time.

Along the top of the frame is inscribed the salutation "To Lord Plouton" in Greek. Immediately to the left of this address is a small bust of the Sun (Helios / Sol), and to the right a bust of the Moon (Selene / Luna). Two larger eight-pointed stars, one at each side, symbolize the Dioskouri, the heavenly twins.

The dedication in Greek at the lower part of the frame states that Aurelius Mestikenthos and Aurelia Gepepyris, daughter of Ezbenes and wife of Moukianos, dedicated these gods.

κυρίῳ Πλούτωνι

Αὐρ(ήλιος) Μεστικενθος κὲ Αὐρ(ηλία) Γηπεπυρις Εζβενεος

γυνὴ Μουκιανοῦ τοὺς θεοὺς ἀνέθηκαν.

Inscription IGBulg IV 2343.

The names of the dedicants are Thracian rather than Greek or Roman. The name Gepepyris (Γηπεπυρις) has also been read as Eptepyris (Επτεπυρις). IGBulg V 1997, 5927 = 2343.

The dedicants have chosen to appeal to the gods responsible for health (Asklepios), wealth (Hermes Kerdoos and Plouton) and life after death (Plouton/Hades and Persephone).

For further information about this relief, see Demeter and Persephone part 2. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

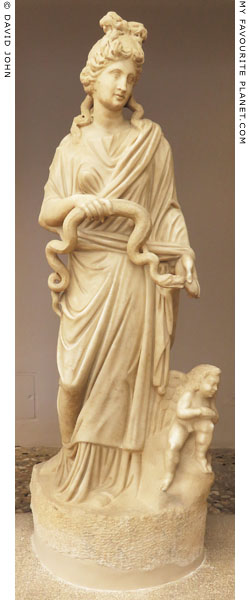

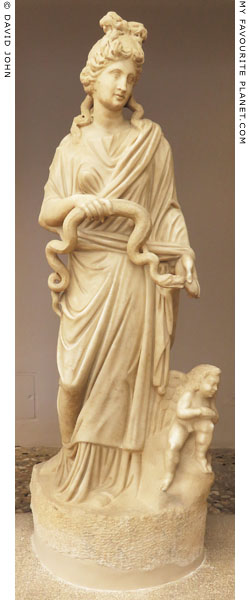

A marble statue of Hygieia and Hypnos (Sleep) in Kos. The standing goddess wears a

himation (cloak) wrapped around a long chiton (tunic). She has an elaborate coiffure,

with her hair tied up into a topknot. In her right hand she holds a large snake, which

appears to be feeding from an agg she holds in her left hand. On a rock to her left side

sits the much smaller figure of Hypnos as a naked, winged infant.

200-250 AD. Found in June 1937, along with six other marble statues, including a statue

of Asklepios and Telesphoros (see below), in Room VIII of the "House of the Rape of

Europa" (la Casa considdetta del Ratto di Europa), in the centre of Kos Town, during

excavations 1936-1940 directed by Italian archaeologist Luigi Morricone (see Hermes).

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 98 (Γ 3084). |

|

|

|

|

|

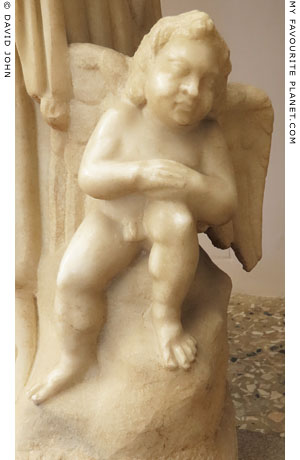

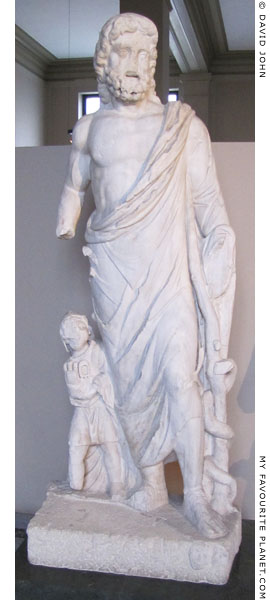

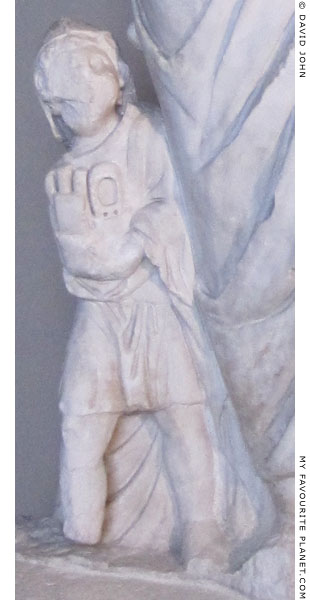

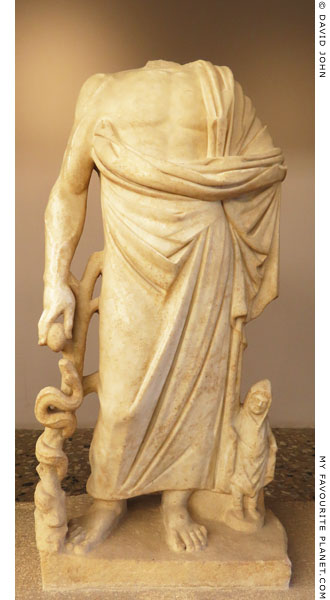

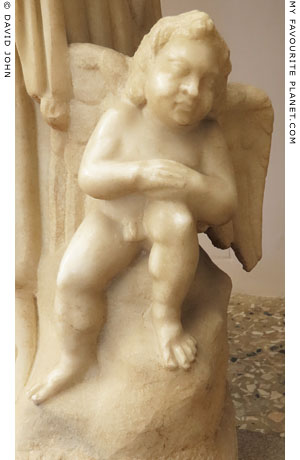

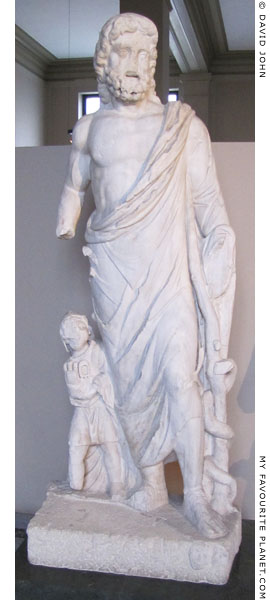

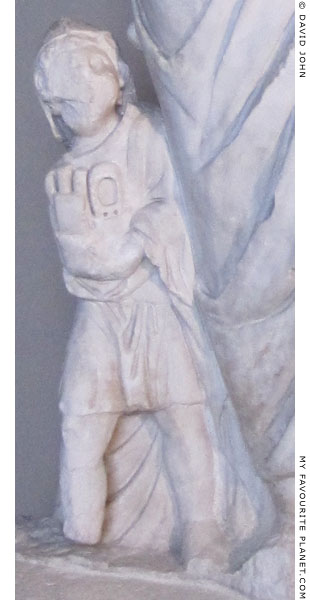

Marble statue of Asklepios and his son Telesphoros. The detail

on the right shows a close-up of the diminuitive daemon.

Excavated in 1906-1907 at the Faustina Baths, Miletus (Balat,

Aydin, Turkey). Height 213 cm; height of Telesphoros 81 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1995.

Cat. Mendel (Volume I, 1912) 124.

|

|

The statue depicts the lofty god Asklepios carrying his symbol of a staff (sometimes shown as a crutch), around which a snake is entwined. A relatively tiny Telesphoros is shown leaning against his father's protective garment, looking up to him, and clutching implements which are probably medical instruments. The implication of this image seems to be that Telesphoros was his father's little helper.

Telesphoros (Τελεσφόρος, "the accomplisher" or "bringer of completion"; Latin, Telesphorus), a son of Asklepios, was worshipped at asklepieions as the helper in recovery from illness. In stark contrast to the powerful images of his father Asklepios and his ancient health-conscious sister Hygieia, Telesphoros is always depicted as a small, sad-looking child or dwarf wearing a hooded cape or conical cap and a short tunic.

This very un-Greek representation of a deity has led to theories that this late-comer to Hellenic religion was of foreign origin, possibly Thracian, Phrygian or Celtic, and that he was originally one of the hooded spirits (genii cuculati), daemons associated with fertility and death. Images of him are also known on the Danube. His worship may have been introduced to the Greek world by the Galatians when they invaded Anatolia in the 3rd century BC. He became associated with Asklepios by the Greeks of Pergamon and other Asklepios centres in Anatolia (Asia Minor).

The spread of his cult westwards to Greece and the Roman Empire was accelerated following his adoption by Epidauros in the 2nd century AD.

The 2nd century AD Greek travel writer Pausanias (Παυσανίας), who may himself have been a doctor, and who spent some time in Pergamon, mentioned Telesphoros in his description of the sanctuary of Asklepios at Titani (Τιτάνη Κορινθίας), in Sikyonia, near Corinth. He tells us that Asklepios' son was known at Titani as Euamerion (Ευαμεριων, Prosperous), and at Epidauros as Akesis (Ακεσις, Cure).

"Alexanor, the son of Makhaon, the son of Asklepios, came to Sikyonia and built the sanctuary of Asklepios at Titane... There are images also of Alexanor and of Euamerion; to the former they give offerings as to a hero after the setting of the sun; to Euamerion, as being a god, they give burnt sacrifices. If my conjecture is correct, the Pergamenes, in accordance with an oracle, call this Euamerion Telesphoros, while the Epidaurians call him Akesis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, Chapter 11, Sections 5-7. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

|

|

|

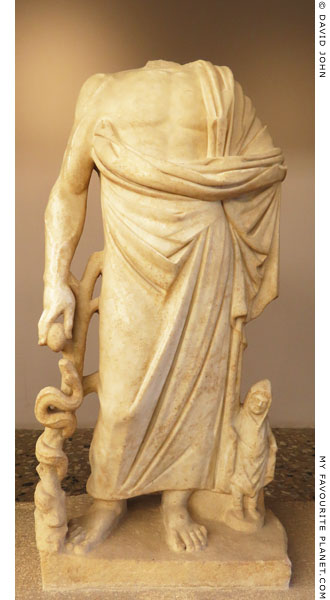

Marble statue of Asklepios, now headless, resting on a snake-entwined crutch.

The snake's head rises towards an egg held in the god's right hand. The tiny

figure of Telesphoros stands at his left side.

Mid 2nd century AD. Found in June 1937, along with six other marble statues,

including the statue of Hygieia and Hypnos above, in Room VIII of the "House

of the Rape of Europa" (la Casa considdetta del Ratto di Europa), in Kos Town,