|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Homer part 1 |

|

back |

Homer – part 1 |

|

Page 1 of 3 |

|

|

| |

| Homer |

| |

Part 1 Introduction (this page)

A short introduction to Homer

Homer in Greek and Roman art |

| |

Part 2 The Iliad

in Greek, Etruscan and Roman art |

| |

Part 3 The Odyssey

in Greek, Etruscan and Roman art

including the Trojan Horse |

| |

Homer (Ὅμηρος, Homeros) is the name given by the ancient Greeks to the author of two important early epic narrative poems in Greek, The Iliad (Ιλιάς) and The Odyssey (Ὀδύσσεια).

Debate has continued since antiquity over the identity of Homer. Did he really exist as a historical individual and literary genius? If so did he compose both epic poems, and perhaps others as well? Was he a bard who composed, memorized and performed the poem or poems without the aid of writing (the alphabet was introduced to Greece in the early 8th century BC)? Or was he the first to write or dictate the poems that he had either composed himself or learned from other poets, a link in a long chain of oral tradition? Or were his name and character later inventions, to represent collectively several early Greek poets and the spirit of Archaic epic verse?

Whether Homer was a real person, a legendary or mythological character, other literary works were also attributed to him, including poems of the Epic Cycle (the Little Iliad, the Cypria, the Nostoi, the Epigoni and the Theban Cycle), the Homeric Hymns, the Margites, the Batrachomyomachia (The frog-mouse war), the Capture of Oechalia and the Phocais. Several of these poems have also been attributed to other poets, and many modern scholars believe that these works are of a later date than The Iliad and The Odyssey.

The Iliad tells of legendary and mythical heroic events around the time of Bronze Age conflicts between Greeks and Anatolians, distilled into the story of the Trojan War. The Odyssey synthesizes seamen's yarns of pioneer Greek military, piratical and merchant sea voyages around the Mediterranean into the wanderings of Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) during his ten year journey to his home in Ithaka (Ιθάκη) at the end of the war.

The stories take place in the late second millenium BC, for later Greeks an era of larger-than-life heroes, great warriors, founders of cities and dynasties, some of whom were descended from gods and other divine figures who interacted with the mortal characters and either actively supported or opposed them. Monsters, magic and the supernatural were part of the characters' lives and adventures.

Many of the stories of this era, true and fictional, were transmitted orally from generation to generation, often in the form of songs and poetry which in themselves contributed to the creation and preservation of the great heroic ethos. Each generation of bards no doubt altered and added details to show off their skills and to appeal to local contemporary tastes of audiences.

In the case of The Iliad and The Odyssey, the questions of how much of the original Bronze Age traditions survived this process, how much was based on historical fact and/or age-old story-telling, and how much was newly created by the writer (or writers) will keep scholars busy for many years to come.

Other "Homeric questions", including the matter of the first written forms of the two epics have also been debated since antiquity. There was a tradition that the legendary Spartan legislator Lycurgus (Λυκοῦργος), who perhaps lived in the second half of the 9th century BC, had first brought Homer's poetry to Greece from Ionia. Modern scholars have a number of objections to this belief. Firstly, Lycurgus may have lived before Homer, and even before Greek literacy had developed sufficiently for sophisticated poetry to be expressed in written form. Secondly, the earliest known reports of this tradition are considered to be quite late, known only from writers of the Roman Imperial period, such as Plutarch (Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD) and Aelian (see below).

Plutarch began his Life of Lycurgus by pointing out that the various earlier accounts (by authors including Aristotle, Eratosthenes, Apollodorus, Timaeus and Xenophon) were of uncertain reliability and contradictory, agreeing neither on dates nor details. Timaeus had conjectured that there were two men named Lycurgus in Sparta at different times, the first of whom lived not long after Homer. Others had written that Lycurgus had even met Homer (chapter 1, sections 1-2). He is said to have travelled around the Mediterranean (or at least the Aegean) and visited Ionia, where he copied and compiled poems of Homer preserved by the Kreophyleioi, a guild of rhapsodes on Samos who claimed descent from Kreophylos (Κρεώφυλος), a legendary Greek epic poet from Samos or Chios (see also below).

"There too, as it would appear, he made his first acquaintance with the poems of Homer, which were preserved among the posterity of Creophylus; and when he saw that the political and disciplinary lessons contained in them were worthy of no less serious attention than the incentives to pleasure and license which they supplied, he eagerly copied and compiled them in order to take them home with him. For these epics already had a certain faint reputation among the Greeks, and a few were in possession of certain portions of them, as the poems were carried here and there by chance; but Lycurgus was the very first to make them really known."

Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, chapter 4, section 4.

At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website.

The fact that he is said to have "copied" the poems, and that a few Greeks were "in possession" of extracts, indicates that some ancient authors believed the works were already written down and in circulation at a very early date.

Since at least the Classical period there was a belief that the Athenian tyrant Peisistratos (Πεισίστρατος, ruled circa 546-527 BC) and Hipparchos (Ἵππαρχος, assassinated by Harmodius and Aristogeiton in 514 BC), one of his two sons, were responsible for introducing Homer's poems to Athens, and the institution of their performance during the Panathenaic Festival, which had been reorganized by Peisistratos (see Athens Acropolis page 3). In the dialogue Hipparchos, attributed to Plato (Πλάτων, 428-347 BC) and named after the tyrant's son, the philosopher Socrates (Σωκράτης, circa 470-399 BC) is made to give credit to him for both achievements:

"Socrates: I mean my and your fellow citizen, Pisistratus' son Hipparchus, of Philaidae, who was the eldest and wisest of Pisistratus's sons, and who, among the many goodly proofs of wisdom that he showed, first brought the poems of Homer into this country of ours, and compelled the rhapsodes at the Panathenaea to recite them in relay, one man following on another, as they still do now."

Plato, Hipparchus sections 228b-228c.

At Perseus Digital Library.

A number of authors during Roman times wrote that Peisistratos commissioned the compilation and editing of Homer's poems, during which they were divided into The Iliad and The Odyssey. Presumably undertaken by one or more scribes, it was seen as the first attempt to produce a definitive or authoritative version of Homer's works. This legendary edition is referred to as the "Peisistratean recension" by modern scholars, though many doubt its existence. [4] One of the earliest Roman authors to record this belief was the philosopher, lawyer and statesman Cicero (106-43 BC), who discussed

"the seven wise men" of ancient Greece:

"But to direct my remarks to the Greeks (whom we cannot omit in a dissertation of this nature; for as examples of virtue are to be sought among our own countrymen, so examples of learning are to be derived from them), seven are said to have lived at one time, who were esteemed and called wise men. All these men, except Thales of Miletus, governed their respective cities. Whose learning is reported, at the same period, to have been greater, or whose eloquence to have received more ornament from literature, than that of Pisistratus? - who is said to have been the first that arranged the books of Homer as we now have them, when they were previously confused."

Cicero, De Oratore, Book 3, section 137. At attalus.org.

The later Roman author Aelian (Κλαύδιος Αἰλιανός, Claudius Aelianus; circa 175-235 AD) also wrote of the purported roles played by Lycurgus and Peisistratos in compiling the Homeric epics.

"The Ancients sung the Verses of Homer, divided into several parts, to which they gave particular names; as the Fight at the Ships, and the Dolonia, and the Victory of Agamemnon, and the Catalogue of the Ships. Moreover the Patroclea, and the Lytra [or redemption of Hector's Body], and the Games instituted for Patroclus, and the breach of Vows. Thus much of the Iliads.

As concerning the other [the Odysseis], the actions at Pytas, and the actions at Lacedemon, and the Cave of Calypso, and the Boat, the Discourses of Alcinous, the Cyclopias, the Necuia [or Necyomantia, Odysseus' descent into the underworld in Book 11] and the washings of Circe, the death of the Woers, the actions in the Field, and concerning Laertes.

But long after Lycurgus the Lacedemonian brought all Homer's Poetry first into Greece from Ionia whether he travelled. Last of all Pisistratus compiling them, formed the Iliads and Odysseis."

Claudius Aelianus, Various History, Book 13, chapter 14. At James Eason's website, Penelope, University of Chicago.

Elsewhere Aelian credited Hipparchos with the introduction of Homer's poems to Athens, and the institution of their performance during the Panathenaic Festival, which had been reorganized by his father (see Athens Acropolis page 3).

"Hipparchus, eldest son of Pisistratus, was the wisest person among the Athenians. He first brought Homer's Poems to Athens, and caused the Rhapsodists to sing them at the Panathenaick Feast."

Claudius Aelianus, Various History, Book 2, chapter 2. At Penelope, University of Chicago.

The two epics became enormously influential works throughout the Greek and Roman world for a millenium; considered exemplary in poetic and literary terms, essential reading and central to the cultural values of the time.

It should not come as a surprise for us to learn that the Greeks built shrines to their author and eventually deified him (see The Apotheosis of Homer below).

Alexander the Great was said to have a particular love of Homer's poetry, especially The Iliad with its typically Homeric ideals of honour and glory. On his campaigns through Asia he carried a copy of the work which Aristotle had annotated and given to him as a gift.

There is no doubt that the works are literary masterpieces, and the language, technique and style of the poetry in which they are written, as well as the structural and narrative qualities, are still influential and universally admired. They are also like gazeteers and a veritable who's who (or all too often who killed whom) of the ancient world. The Greek geographer Strabo (circa 64 BC - 24 AD) called Homer the founder of geography:

"And first, [we maintain,] that both we and our predecessors, amongst whom is Hipparchus, do justly regard Homer as the founder of geographical science, for he not only excelled all, ancient as well as modern, in the sublimity of his poetry, but also in his experience of social life. Thus it was that he not only exerted himself to become familiar with as many historic facts as possible, and transmit them to posterity, but also with the various regions of the inhabited land and sea, some intimately, others in a more general manner. For otherwise he would not have reached the utmost limits of the earth, traversing it in his imagination."

Strabo, Geography, Book 1, chapter 2, section 2.

Many of the geographical, topographical and historical details in Homer's works have in fact been confirmed by archaeologists, historians and scientists over the last two centuries, proving at least that the author based his often incredible tales on a solid ground of facts.

The style, language and several other details have led many scholars to believe that the versions of The Iliad and The Odyssey known from antiquity were probably written by an author from East Greece (western Anatolia and the eastern Aegean islands) about 750-700 BC. This is around the same time as the poet Hesiod is also thought to have lived.

The earliest known mention of Homer was by the philosopher and poet Xenophanes of Colophon (Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος, circa 570-475 BC), who criticized the way in which he and Hesiod represented the gods. [5] An oft-quoted passage of Pausanias stating that a certain Kelainos (or Kallinos) attributed the epic poem Thebais to Homer is questionable. [6]

The Iliad and The Odyssey were first mentioned by Herodotus (circa 484 - circa 425 BC), who considered that Homer and Hesiod virtually invented the names, genealogies, forms and functions of the gods:

"But whence each of the gods came to be, or whether all had always been, and how they appeared in form, they did not know until yesterday or the day before, so to speak. For I suppose Hesiod and Homer flourished not more than four hundred years earlier than I; and these are the ones who taught the Greeks the descent of the gods, and gave the gods their names, and determined their spheres and functions, and described their outward forms.

But the poets who are said to have been earlier than these men were, in my opinion, later. The earlier part of all this is what the priestesses of Dodona tell; the later, that which concerns Hesiod and Homer, is what I myself say." [7]

At some point Homer acquired a biography and became known as the blind bard from Ionia, and at least four East Greek cities, Smyrna, Chios, Kolophon and Kyme, claimed the bard as a native son (see the inscription from Pergamon below).

The Roman author Aulus Gellius (circa 125 - after 180 AD) mentioned even more places making this claim to fame, and repeated the legend that his tomb was on Ios:

"Also as to Homer's native city there is the very greatest divergence of opinion. Some say that he was from Colophon, some from Smyrna; others assert that he was an Athenian, still others, an Egyptian; and Aristotle declares that he was from the island of Ios. Marcus Varro, in the first book of his Portraits, placed this couplet under the portrait of Homer:

'This snow-white kid the tomb of Homer marks;

For such the Ietae offer to the dead.'" [8]

(The Ietae were the inhabitants of Ios.)

The author and date of a famous epigram on the subject of Homer's birthplace are unknown:

"Seven cities contend for the birth of Homer: Smyrna, Rhodes, Kolophon, Salamis [Cyprus], Ios, Argos and Athens." [9]

Pausanias (2nd century AD) discussed the birthplace of Homer when remarking on a statue and accompanying inscription at the entrance to the Temple of Apollo in Delphi:

"... and you can see a bronze statue of Homer on a slab, and read the oracle that they say Homer received: 'Blessed and unhappy, for to be both wast thou born.

Thou seekest thy fatherland; but no fatherland hast thou, only a motherland.

The island of Ios is the fatherland of thy mother, which will receive thee

When thou hast died; but be on thy guard against the riddle of the young children.'

The inhabitants of Ios point to Homer's tomb in the island, and in another part to that of Clymene, who was, they say, the mother of Homer.

But the Cyprians, who also claim Homer as their own, say that Themisto, one of their native women, was the mother of Homer, and that Euclus foretold the birth of Homer in the following verses:

'And then in sea-girt Cyprus there will be a mighty singer,

Whom Themisto, lady fair, shall bear in the fields,

A man of renown, far from rich Salamis.

Leaving Cyprus, tossed and wetted by the waves,

The first and only poet to sing of the woes of spacious Greece,

For ever shall he be deathless and ageless.'

These things I have heard, and I have read the oracles, but express no private opinion about either the age or date of Homer."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 24, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Elsewhere Pausanias related a local legend at the Ionian city of Smyrna (Σμύρνα; today Izmir, Turkey) that Homer had lived in a cave near the city, at the springs of the river Meles (ποταμὸς Μέλης, perhaps today's Yeşildere stream).

"The Smyrnaeans have the river Meles, with its lovely water, and at its springs is the grotto, where they say that Homer composed his poems." [10]

Pausanias, Book 7, chapter 5, section 12. At Perseus Digital Library.

In a rare ancedote concerning Homer related by Strabo, we learn of two poets who were said to have been his teacher, Kreophylos of Samos (Κρεώφυλος ὁ Σάμιος) and Aristeas (Ἀριστέας) of Proconnesos (today Marmara island). The authorship of the poem The Capture of Oechalia (Οἰχαλίας ἅλωσις) was also a matter of debate. While it was said to have been written by Homer who gave it to Kreophylos in thanks for his hospitality, the Alexandrian poet Kallimachos (Καλλίμαχος, circa 310-240 BC) claimed Kreophylos composed it.

"Creophylus, also, was a Samian, who, it is said, once entertained Homer and received as a gift from him the inscription of the poem called The Capture of Oechalia. But Callimachus clearly indicates the contrary in an epigram of his, meaning that Creophylus composed the poem, but that it was ascribed to Homer because of the story of the hospitality shown him:

'I am the toil of the Samian, who once entertained in his house the divine Homer. I bemoan Eurytus [Εὔρυτος, king of Oechalia], for all that he suffered, and golden-haired Ioleia [Ἰόλεια, daughter of Eurytus]. I am called Homer's writing. For Creophylus, dear Zeus, this is a great achievement.'

Some call Creophylus Homer's teacher, while others say that it was not Creophylus, but Aristeas the Proconnesian, who was his teacher."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, section 18. [11] |

|

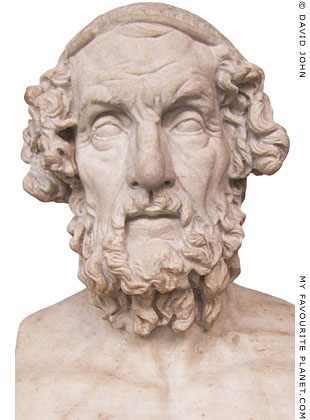

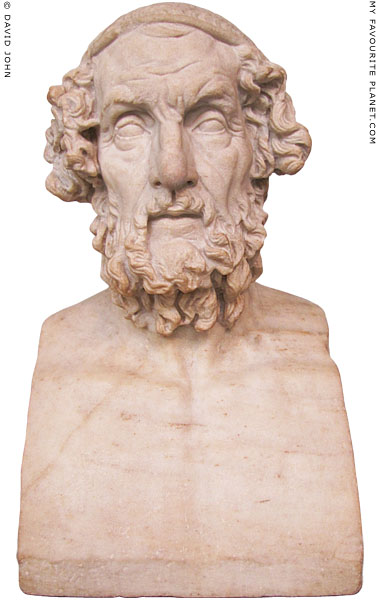

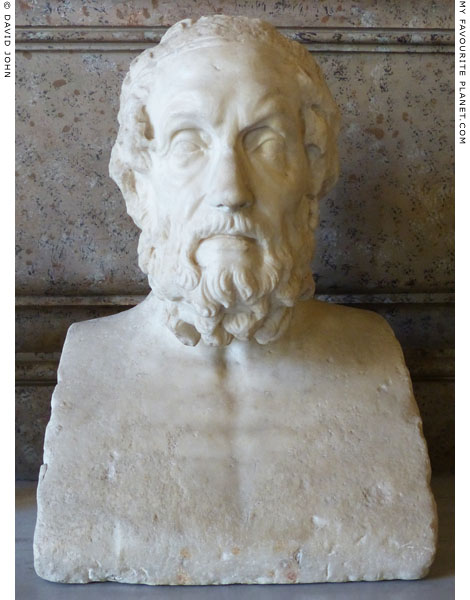

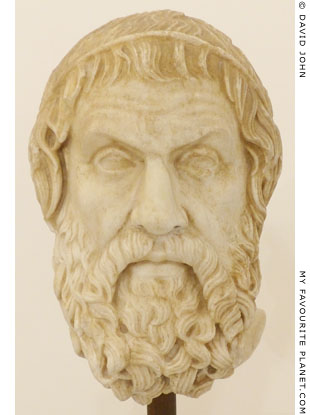

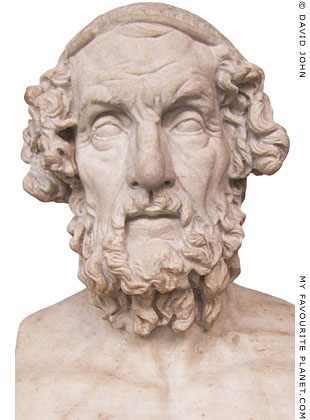

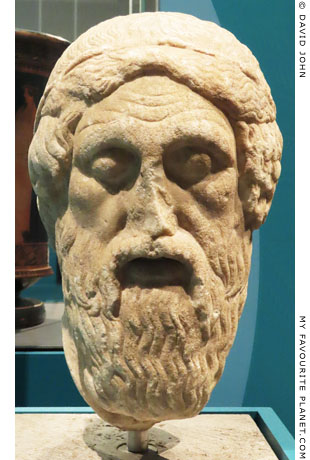

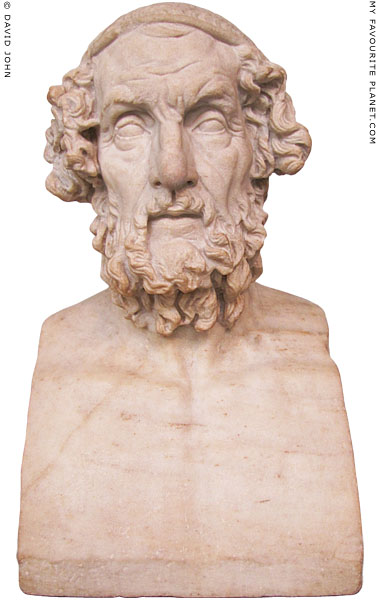

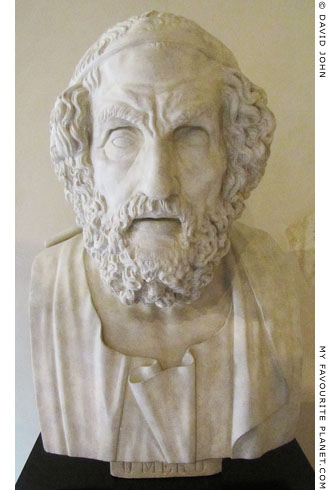

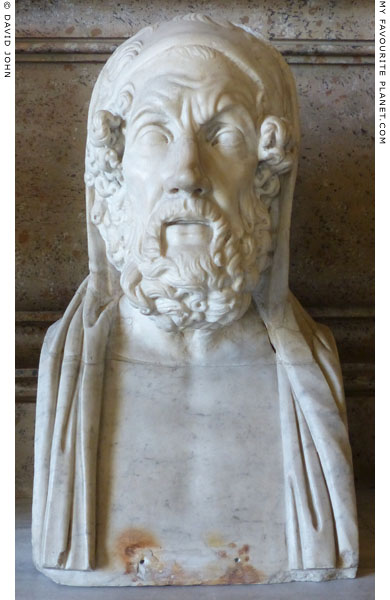

Marble bust of Homer of the "Hellenistic

blind type" or "Pergamon type". Found in

Baiae, Bay of Naples, Campania, Italy. [1]

British Museum, London.

Inv. No, GR 1805.7-3.85 (Sculpture 1825). |

| |

A nicolo intaglio engraved with a head

of Homer of the "Hellenistic blind type",

facing front. Believed to have been

made in the Roman Imperial period,

inspired by a sculpture of this type.

If it is really antique, and not a modern

forgery, it is the only ancient gem with

a portrait of Homer so far known.

Height 1.4 cm, width 1.0 cm.

Once in the Alfred Morrison Collection

and then the collection of British

archaeologist Sir Athur Evans.

Present location unknown. [2] |

| |

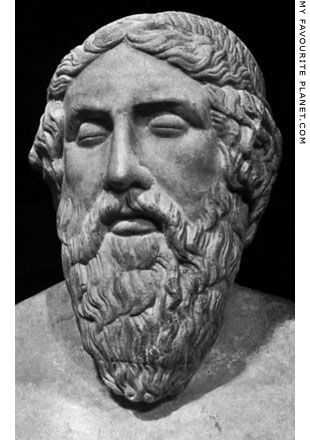

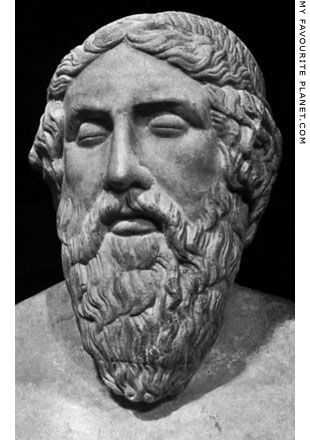

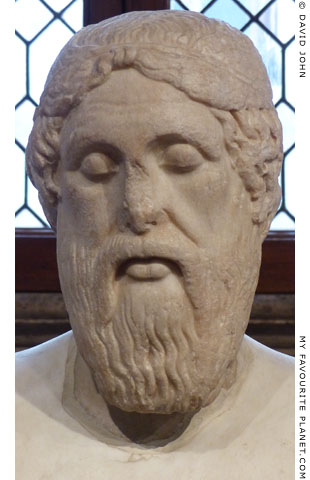

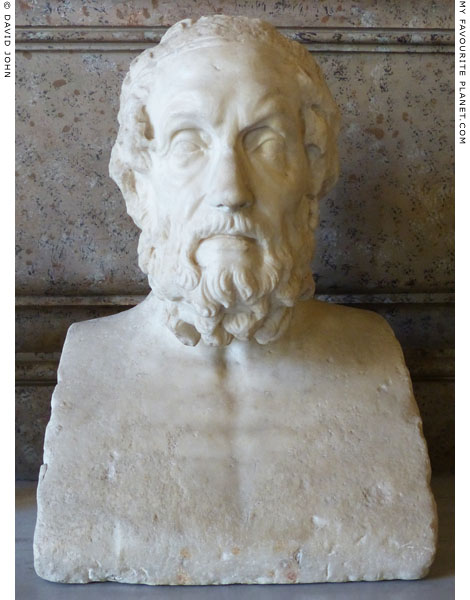

A marble herm bust with a portrait of Homer

of the "Epimenides type" [3], with a long,

straight beard and closed eyes, thought

to imply the poet's blindness.

Roman period. Possibly a copy of a

mid 5th century BC Greek prototype.

Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 315.

Anton Hekler, Greek & Roman portraits,

plate 9a. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York,

1912. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

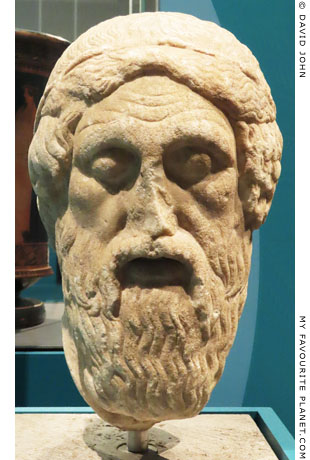

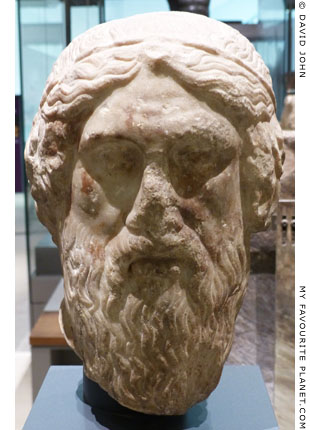

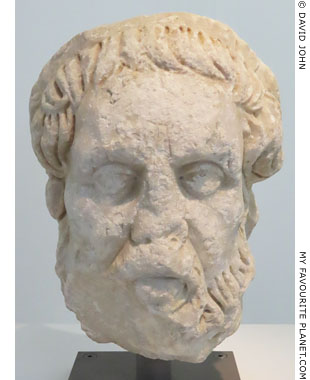

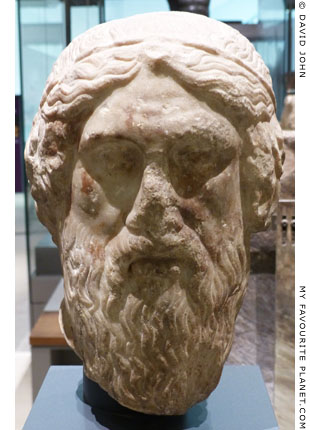

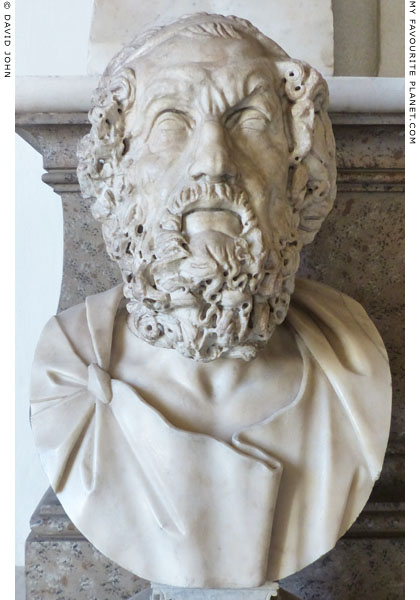

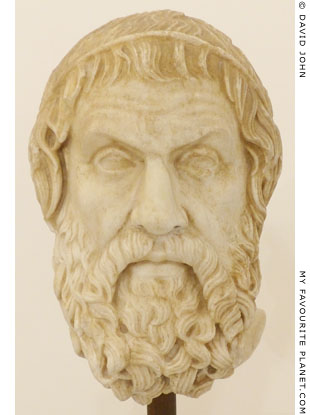

A marble head of Homer

of the "Epimenides type".

Roman period, 1st century AD.

Height 39.7 cm, width 23.6 cm,

depth 25.7 - 30.7 cm.

Staatliche Antikensammlungen und

Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 273.

Purchased in Rome around 1890 by the

German archaeologist Paul Julius Arndt,

who donated it to the museum in 1892. |

| |

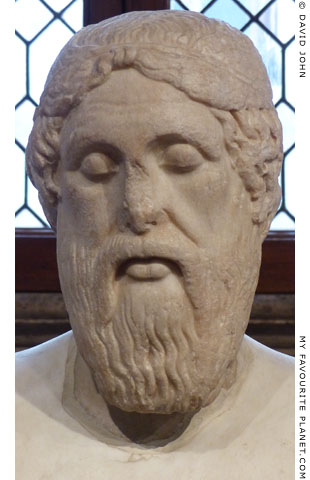

Head of Homer of the "Epimenides type".

Roman period. Parian marble.

Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 123.

Purchased in Rome. |

| |

A marble head of Homer. 1-100 AD.

Similar to the "Epimenides type" heads

above but, unusually, with open eyes.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Inv. No. LI1022.1. On loan from

the Franziska Winters Collection. |

| |

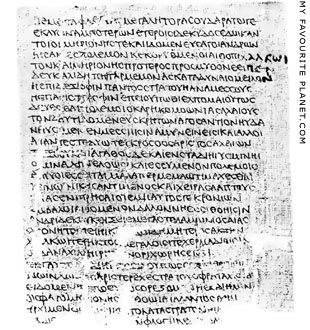

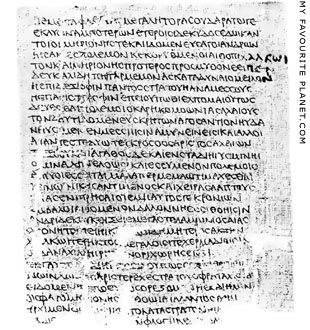

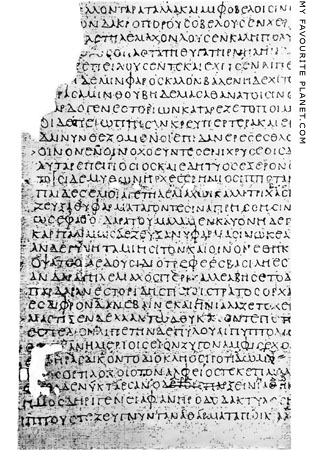

Detail of a papyrus roll with part of Book 13

of the Iliad. The roll is one of the longest

surviving Homer papyri, containing most

of the Iliad Books 13 and 14. From Egypt,

1st or 2nd century AD.

British Museum. Papyrus DCCXXXII.

Source: Frederic B. Kenyon,

The palaeography of Greek papyri,

Plate XIX, page 97.

Oxford University Press, 1899. |

| |

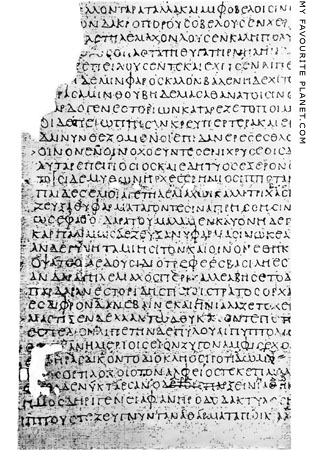

A papyrus fragment of the Odyssey,

the end of Book 3. The earliest surviving

copy of the work. Early 1st century AD.

British Museum. Papyrus CCLXXI.

Source: Frederic B. Kenyon,

The palaeography of Greek papyri,

Plate XV, page 84.

Oxford University Press, 1899. |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| Homer |

Homer in Greek and Roman art |

|

|

|

If Homer lived in the 8th century BC, some time earlier, or even a century later, this was long before realistic portraiture was practised by the Greeks. It is therefore considered that all the portraits of him were works of pure imagination, like those of many other famous people, created throughout antiquity to supply a popular need to have a face to go with a name.

Sculptures representing the legendary poet were made as early as the Classical period (5th - 4th century BC). Pausanias mentioned statues of Homer and Hesiod, among a number of statues dedicated by Mikythos, the former tyrant of Rhegium in the mid 5th century BC, next to the Great Temple of Zeus in the Sanctuary of Olympia. [12]

Statues and busts of Homer, showing him as a scholarly, elderly, blind man, were placed in libraries and sanctuaries, a tradition which continued into Roman times. There were sculptures of this type in the Library of Pergamon and the Homereion of Alexandria, a centre for Homeric studies during the Hellenistic period. [13] The practice of inventing idealized portraits of famous writers and setting them up in libraries was commented on by Pliny the Elder:

"There is a new invention too, which we must not omit to notice. Not only do we consecrate in our libraries, in gold or silver, or at all events, in bronze, those whose immortal spirits hold converse with us in those places, but we even go so far as to reproduce the ideal of features, all remembrance of which has ceased to exist; and our regrets give existence to likenesses that have not been transmitted to us, as in the case of Homer, for example.

And indeed, it is my opinion, that nothing can be a greater proof of having achieved success in life, than a lasting desire on the part of one's fellow-men, to know what one's features were.

This practice of grouping portraits was first introduced at Rome by Asinius Pollio [75 BC - 4 AD], who was also the first to establish a public library, and so make the works of genius the property of the public. Whether the kings of Alexandria and of Pergamus, who had so energetically rivalled each other in forming libraries, had previously introduced this practice, I cannot so easily say."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, chapter 2. At Perseus Digital Library. [14]

Around the end of the 5th century AD, the Egyptian poet Christodorus described a bronze statue of Homer in the Baths of Zeuxippus in Constantinople:

"... the features of an old man, but of a gentle old age, so much so that it gives him an even richer aura of grace: a mix of venerability and admiration, but from which prestige shines through... With his two hands supported by his staff, one on top of the other, like a real man. The right ear bent, as if always listening to Apollo, almost as if he could hear a Muse nearby..."

Anthologia Palatina, II, 311-349 [15]

Many (if not all) of the cities claiming to be Homer's birthplace, as well as other cities around the Greek world as far as the Black Sea (see photo, above right) issued coins depicting the poet. According to Strabo, the inhabitants of Smyrna (today Izmir, Turkey) had a shrine dedicated to Homer known as the Homereion (Ὁμήρειον), and issued bronze coins of the same name:

"There is also a library, and the Homereium, a quadrangular portico, which has a temple of Homer and a statue ("ξόανον", xoanon). For the Smyrnaeans, above all others, urge the claims of their city to be the birth-place of Homer, and they have a sort of brass money, called Homereium."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, section 37. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Greek word xoanon (ξόανον) is usually taken to mean a very ancient or prehistoric statue carved of wood, but Pausanias may have used it to mean cult statue (see note on Athens Acropolis page 11).

The enormous popularity and cultural influence of Homer's epic poems, as well as Homeric stories about the Trojan War and Oysseus by other authors (and perhaps also surviving oral tradions), are evident in the large number of surviving artworks illustrating scenes from the works (see Homer part 2 and part 3) made and traded around the Graeco-Roman world. |

Roman provincial bronze coin showing the

head of Homer in profile, facing right. From

Amastris, Paphlagonia, Black Sea, 100-260 AD.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Inv. No. HCR7895. |

| |

A coin of Amastris, showing the head of Homer

in profile, facing right, around which his name

is inscribed in Greek ΟΜΗ ΡΟΣ.

Such coins were considered important in the

identification of portrait sculptures of Homer

discovered since the Renaissance.

Image source: Wolfgang Helbig, Guide to the public

collections of classical antiquities in Rome, Volume 1,

Fig. 21, page 360. Leipzig, 1895. [see note 16] |

| |

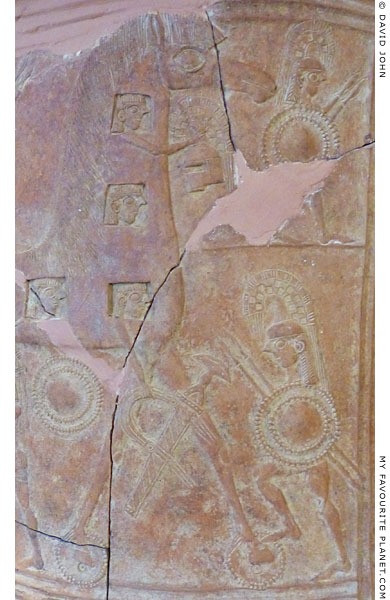

The Trojan Horse (Wooden Horse of Troy) on the

neck of the "Mykonos Vase", around 675-650 BC.

Mykonos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2240.

See the article and photos in Homer part 3. |

| |

| |

Marble bust of Homer of the "Hellenistic blind type"

or "Pergamon type". Found in Baiae, Bay of Naples,

Campania, Italy [see note 1]. Height: 57.15 cm.

British Museum, London.

Inv. No, GR 1805.7-3.85 (Sculpture 1825). |

|

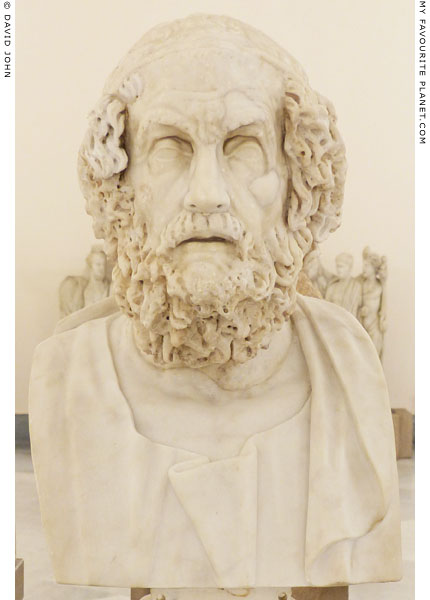

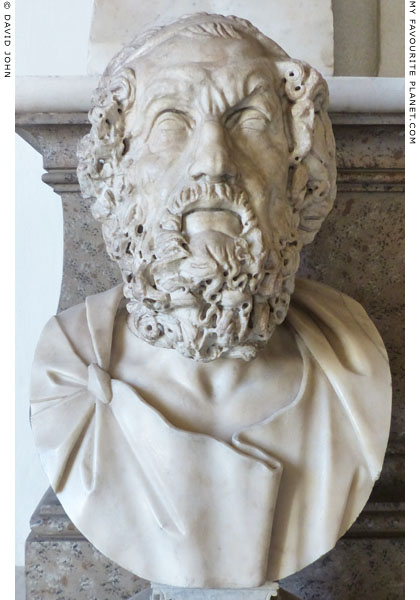

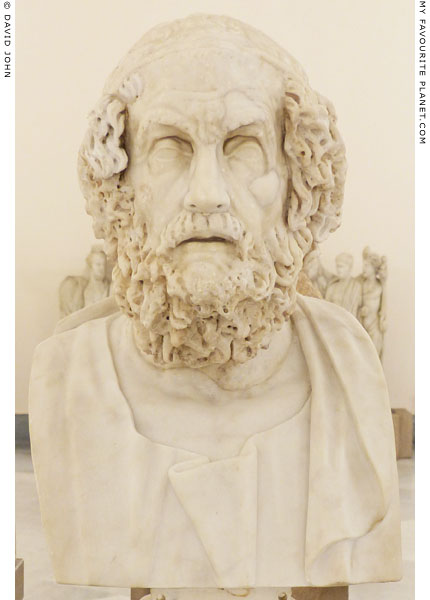

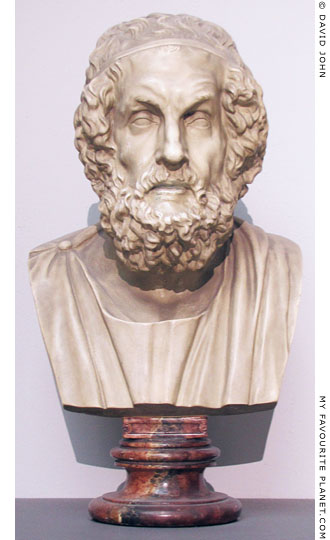

A head of Homer similar to the one in the British Museum

(photo, left) on a modern bust.

Antonine copy (138-192 AD) of a 2nd century BC Greek

original, thought to have been made by the Rhodian School.

Height without bust 33 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6023.

From the Farnese Collection. |

|

| |

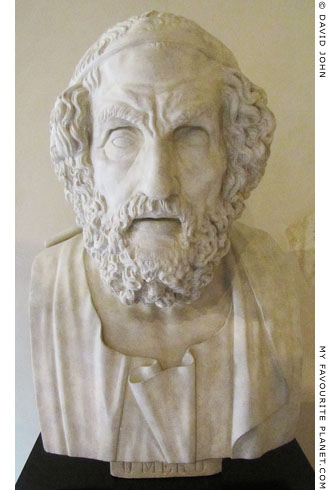

Replica of the Farnese bust of Homer in

Naples, made by Gaetano Rossi in 1875.

Neues Museum, Berlin. |

|

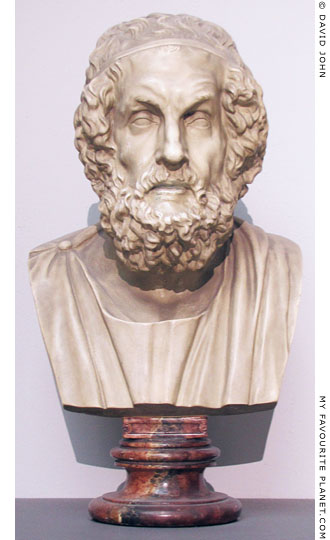

A plaster cast of a plaster cast of the Farnese

bust of Homer. This modern copy, in the

Pergamon Museum, Berlin, was taken from

the cast in the Goethe Nationalmuseum,

Weimar, which is thought to have belonged

to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Berlin, Abguss-Sammlung Antiker

Plastik der Freien Universität, VII 3470.

Rembrandt was also one of several

scholars and artists who possessed

a cast of the Farnese Homer. |

|

| |

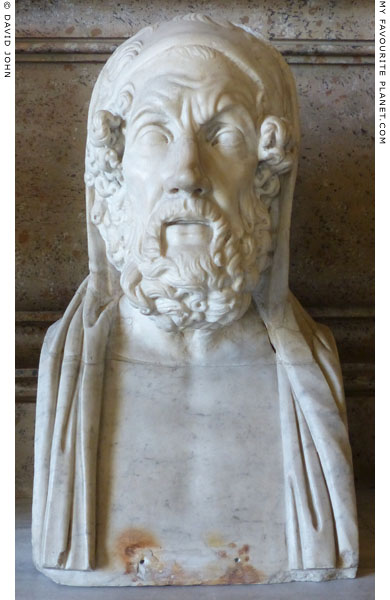

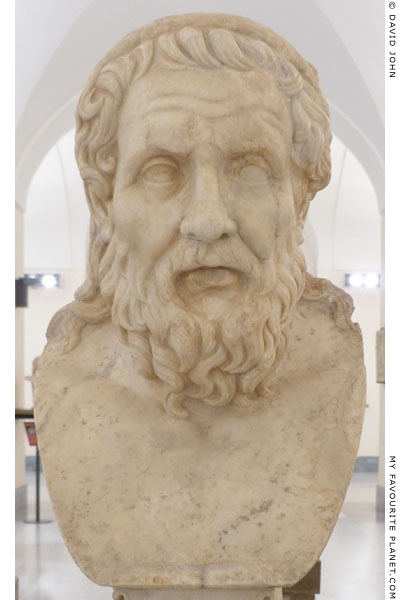

Marble herm bust of Homer of the "Hellenistic blind type".

Roman copy after a 2nd century BC Hellenistic original.

Like the head of the bust, right, it was also reported

to have been found in 1704 in the garden of the

Canonici Regolari di San Antonio Abbate, on the

Esquiline Hill, Rome [16]. Greek marble. Height 53 cm.

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 559.

From the Giustiniani Collection. |

|

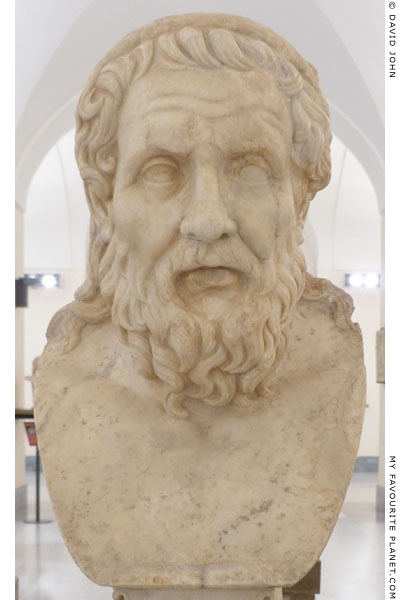

Marble head of Homer of the "Hellenistic

blind type" on a modern bust.

Roman copy after a 2nd century BC Hellenistic original.

Perhaps the head found in 1704 in the garden of the

Canons of San Antonio Abate, Rome [see note 16].

The nose and bust are modern additions. Luna marble.

Height 54 cm, with foot 71 cm.

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 557.

From the Albani Collection (Inv. No. B 10). |

|

| |

Marble herm of Homer of the "Hellenistic blind type".

Roman copy after a 2nd century BC Hellenistic original.

Unusually, the poet is shown "veiled", that is with part of

his himation (cloak) drawn over the back of his head. The

end of the nose and the back of the head as well as most

of the neck and the herm have been restored. Luna marble.

Height 56.5 cm (head 29 cm). [17]

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 558.

From the Albani Collection (Inv. No. B 65). |

|

Marble bust of Homer of the "Apollonius of Tyana" type,

of which there are twelve extant examples, named due

to the previous belief that they were portraits of the 1st

century AD Pythagorean philosopher and miracle worker.

This bust was also once thought to depict Hesiod. [18]

Like the "Modena type" portraits of Homer

(see below), the subject is not evidently blind.

Hadrianic copy (117-138 AD) of a

late 4th century BC Greek original.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6140.

From the Farnese Collection. |

|

| |

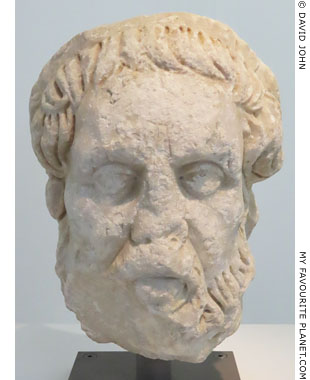

A rather battered marble portrait head of

Homer of the "Apollonius of Tyana" type.

Height 33 cm. Pentelic marble.

Late 3rd - early 4th century AD.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EAM 626. |

|

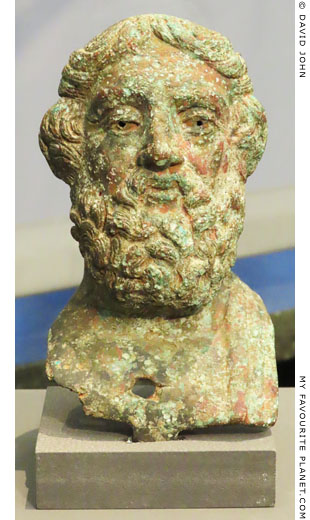

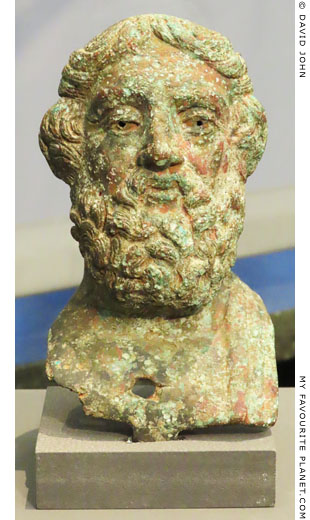

A small bronze bust of Homer of the "Modena type".

1st century AD. Found in Elis, western Peloponnese,

Greece. Height 13.5 cm, with its ancient spigot 14.8 cm.

Antikensammlung, State Museums Berlin (SMB).

Inv. No. Misc. 8091. Purchased in 1888.

Only two almost identical busts of the "Modena type" are known, named after the example currently in the depot of the Galleria Estense, Modena, Italy. (Inv. No. 2121. Height 13.5cm, width 6.5 cm.) The subject of the Modena bust was identified from the inscription ΟΜΗΡΟC (OMEROS, Homer) on the chest. First recorded as being in the collection of Tommaso degli Obizzi at Padua around 1800, it was acquired by Francis IV of Habsburg-Este in 1822. (Read more about the Este family on the Dionysus page.)

It was suspected of being a 16th - 17th century forgery until the discovery of the Berlin bust in Elis appeared to confirm its authenticity. The age of the inscription remains uncertain. Some scholars have commented that the type shows no evident blindness. |

|

| |

|

|

|

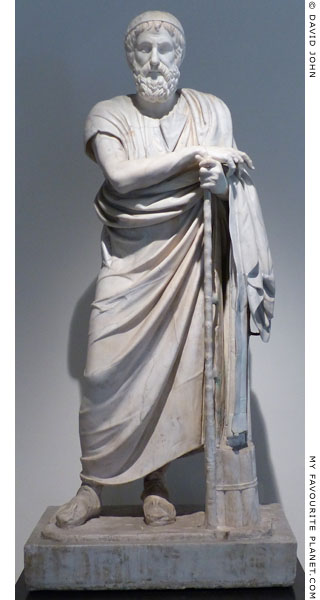

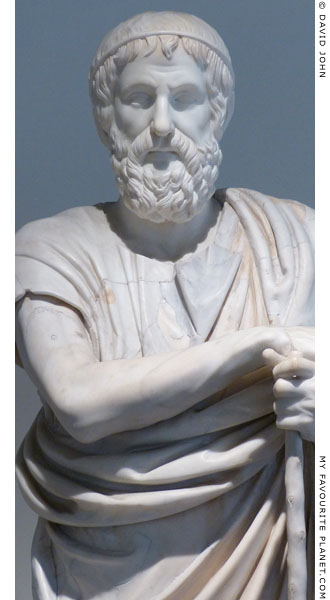

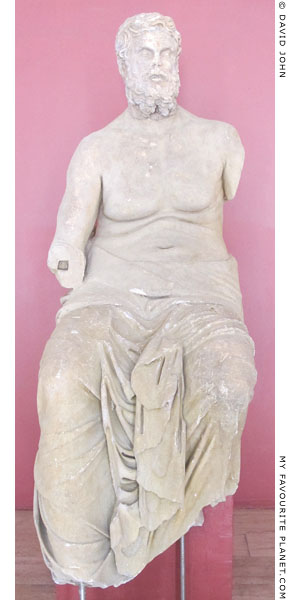

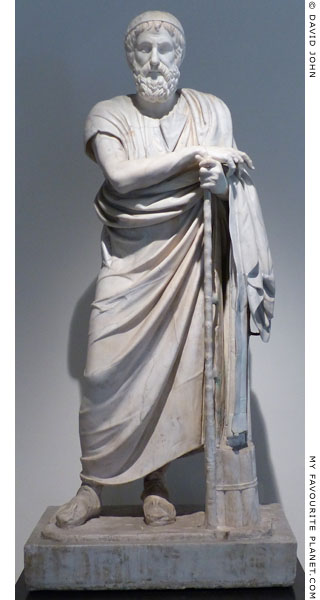

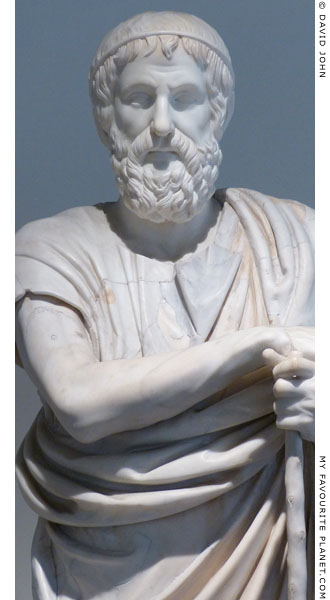

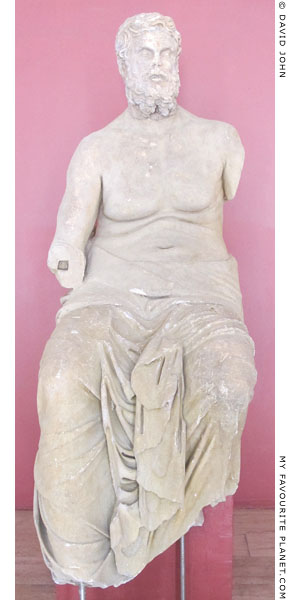

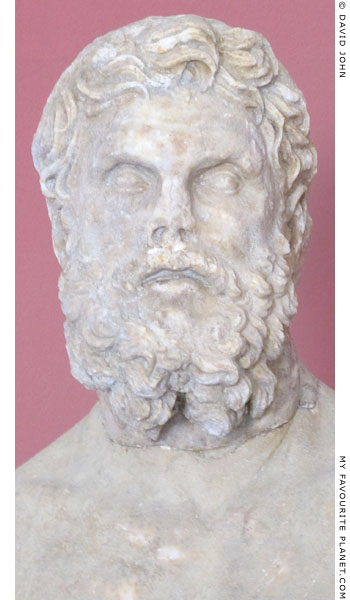

The so-called "Homer" statue, a marble statue thought to represent either Homer or a philosopher.

The head is modern copy of the "Homer-Sophocles" type from a sculpture of the Farnese collection.

Found in 1752 in the rectangular peristyle of the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. Height 198 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6126. |

|

| |

The figure wears a himation (cloak) over a chiton (tunic), indicating that he is a Greek. His clothing and pose identify him as a mature intellectual, perhaps a writer or philosopher. A bundle of papyrus rolls on the base reinforce the identification, as well as providing part of the support for the figure, which also includes part of his himation and a long staff. The pose is reminiscent of the bronze statue of Homer in Constantinople described by Christodorus (see above), which depicted the bard "with his two hands supported by his staff, one on top of the other, like a real man".

As with many ancient sculptures in Italian museums, this statue has been extensively restored, and it is not always easy to spot which parts are modern additions. It was found headless and restorers added a modern head copied from an ancient marble head of the "Homer-Sophocles Farnese type", formerly in the Farnese Collection and now in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples (see photo, right). There are differences in the hair and beard of the copy on this statue, and the features are generally smoother and less severe. The type, of which there are around thirty two extant examples, is named after a Roman period herm bust from the Farnese Collection thought to represent the Athenian playwright Sophocles, copied from a 4th century BC Greek original.

According to the website of the Naples museum, it is currently believed that the statue may have originally represented the Athenian rhetorician Isocrates (Ἰσοκράτης, 436-338 BC). This theory is apparently based on the presence of the papyrus rolls that "represent the art of oratory which the character portrayed was linked to" and "the aspect of an elderly but vigorous man and the quiet attitude of a rhetorician".

See: www.museoarcheologiconapoli.it/en/3598-2/

However, these arguments are not convincing, particularly since there are no extant statues of Isocrates with which it can be compared. Scrolls on statues are not exclusive to those of orators, and the relationship of scrolls to orator statues is much debated. On the "Apotheosis of Homer" relief (see below) Homer is shown holding a scroll, as is the tragic playwright Euripides on the relief from Smyrna in Istanbul. A number of statues have been identified as orators because of scrolls, but those held by statues of Demosthenes, for example, are modern restorations (Braccio Nuovo, Vatican Museums, Inv. No. 2255; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Kopenhagen, Inv. No. 2782; Newby Hall, Ripon, Yorkshire). The scrolls and the posture of this statue could indicate one of a number of mature, learned men of antiquity.

See a bust of Isocrates on Athens Acropolis gallery page 8. |

|

Marble head of Sophocles "Farnese type".

1st century AD copy of a Greek

original of the early 4th century BC.

Found in the Via Ostiense, Rome.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6413. From the Farnese Collection. |

|

| |

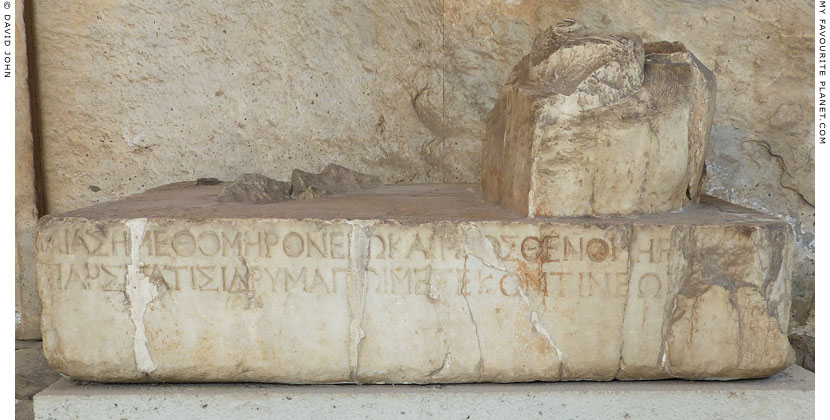

An inscribed limestone base of a statue of Homer from Pergamon.

Late Hellenistic period, 2nd - 1st century BC.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. IvP 203.

|

The blue-grey limestone block was found in May 1881 in the eastern part of the north stoa of the Sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros, the area in which the Library of Pergamon is thought to have stood. Two foot-shaped indentations in the top of the block indicate that it was the base for a standing bronze statue. See below for details of the inscription.

Height 41.5 cm, width 70 cm, depth 75.5 cm. Height of letters 1.2 - 1.4 cm.

Bases for statues of other Greek poets and historians have also been found at the sanctuary: Alkaios of Mytiline, Apollonios, Balakros, Herodotus and Timotheos. The statues were probably part of a collection of monuments dedicated to famous writers exhibited in the library.

See also the base of a statue of Herodotus from the Sanctuary of Athena. |

|

| |

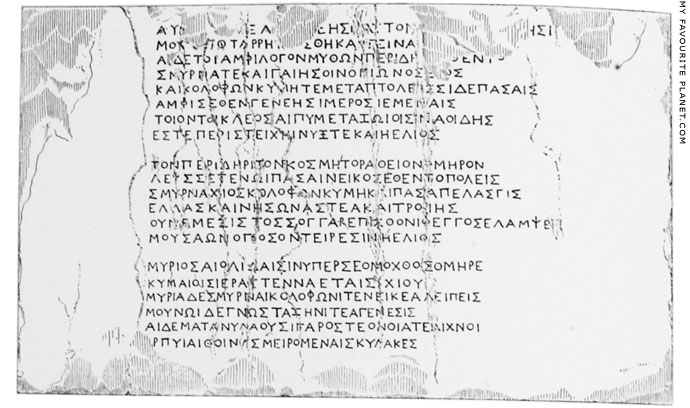

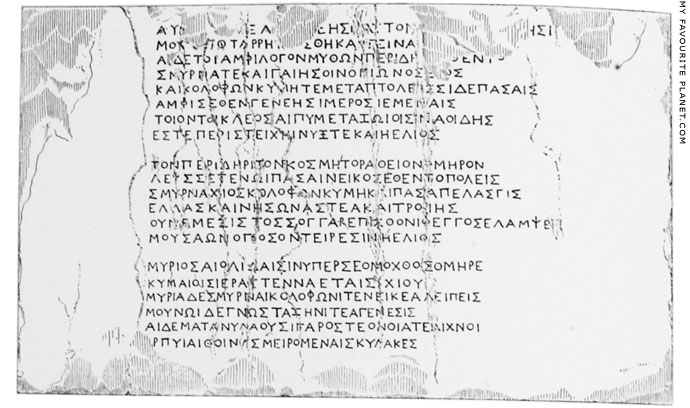

Drawing of the inscription on the Homer statue base from Pergamon by Max Fränkel.

The badly weathered inscription on the front of the block consists of three epigrams

concerning the contending claims of four East Greek cities to be Homer's birthplace:

the Ionian cities of Smyrna, Chios and Kolophon, and Aeolian Kyme.

Inscription IvP I 203.

Image source: Max Fränkel (1846-1903), Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VIII, Band 1:

Die Inschriften von Pergamon, pages 119-121, No. 203. Königliche Museen zu Berlin.

W. Spemann, Berlin, 1890. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

IvP is the common abbreviation for numbered items from the volumes

of Die Inschriften von Pergamon (The inscriptions from Pergamon). |

| |

Greek

αὐ[τὸς δῆ]τα φράζ[ε τ]εῆς κλυτὸν [οὔνομα πάτ]ρης,

μο[ῦνο]ς ὅτ’ ἀρρήτ[ου]ς θήκαο γειναμ[ένους].

α[ἵ]δε τοι ἀμφίλογον μύθων περὶ δῆ̣[ριν ἔ]θεντ̣ο̣·

Σμ̣ύρνα τε καὶ γαίης Οἰνοπ̣ίωνος ἕ̣[δ]ος

καὶ Κολοφῶν Κύμ̣η τε. μέτα πτολέ[ε]σσι δὲ πάσαις

ἀμφὶ σέθεν γενεῆς ἵμερος ἱεμέναις·

τοῖόν τοι κλέος αἰπὺ μετὰ ζώιοισιν ἀοιδῆς,

ἔστε περ̣ιστείχη̣ι νύξ τε καὶ ἠέλιος.

τὸν περιδήριτον κοσμήτορα θεῖον Ὅ̣μηρον

λεύσσετ’, ἐν ὧι πᾶσαι νεῖκος ἔθεντο πόλεις·

Σμύρνα, Χίος, Κολοφῶ̣ν, Κύμη κα̣ὶ πᾶσα πελασγὶς

Ἑλλὰς καὶ νήσων ἄστεα καὶ Τροΐης.

οὐ νέμεσις· τόσσογ γὰρ ἐπὶ χθονὶ φ̣έγγος ἔλαμψε

Μουσάων ὁπ̣όσον τείρεσιν ἠέλιος.

μυρίος αἰολίδαισιν ὑπέρ σεο μόχθος, Ὅμηρε,

Κυμαίοις ἱερᾶς̣ τ’ ἐνναέταισι̣ Χίου,

μυρία δὲ Σμύρναι Κολοφῶνί τε νείκεα λείπεις·

μούνωι δέ γνωστὰ Ζηνὶ τεὰ γένεσις,

αἵδε μάταν ὑλάουσι γὰρ ὄστεον οἷάτε λ̣ίχνοι

[ἅ]ρπυιαι θοινᾶ̣ς μειρόμεναι σκύλακες. |

|

English

"These [cities] have completed, with arguments for and against, about your myths: Smyrna and the place in the land of the Oinopion [Chios], and Kolophon and Kyme: among all cities there is a desire to contend for the fame of your birth. So great is the fame of your singing among the living, as long as night and Helios continue to circle above.

The disputed, divine Homer, the celebrator [of heroes], whom all cities have competed for: Smyrna, Chios, Kolophon, Kyme, and the entire Pelasgian Hellas and the cities of islands and the landscape of Troy. There is no need to be offended: for just as Helios shines among the stars, so does he shine as the light of the Muses on Earth.

Endless effort do we have on account of you, Homer, the Kymeans descended from Aiolos and the people of Chios, endless conflict did you leave behind for Smyrna and Kolophon. But only to Zeus is the place of your birth known; but they [the cities] bark senselessly, just as eager, predatory dogs do for the bones, lusting for a feast." |

|

| |

|

|

|

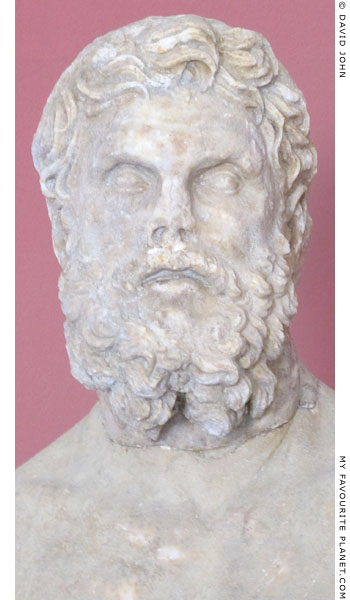

The so-called "Homer" marble statue of a seated man.

Classical period, 4th century BC. Found in 1952 in Klaros (Κλάρος, today Ahmetbeyli,

south of Izmir, Turkey). Height 169 cm, width 64 cm, width 100 cm.

Department of Sculpture, Izmir Museum of History and Art. Inv. No. 3501. |

|

| |

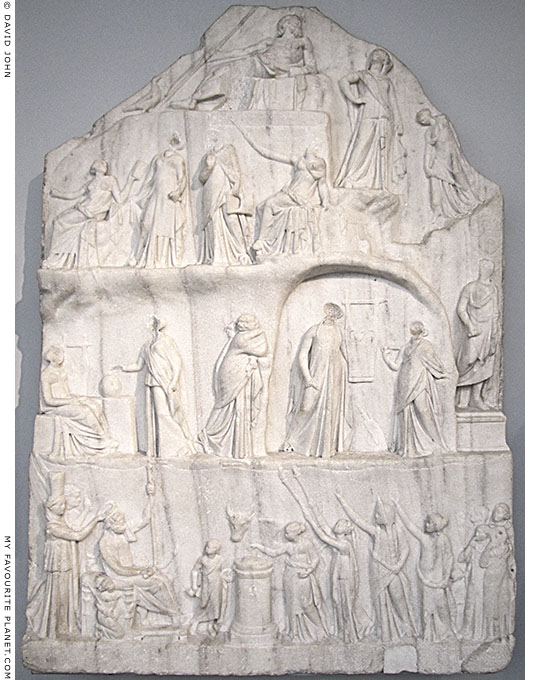

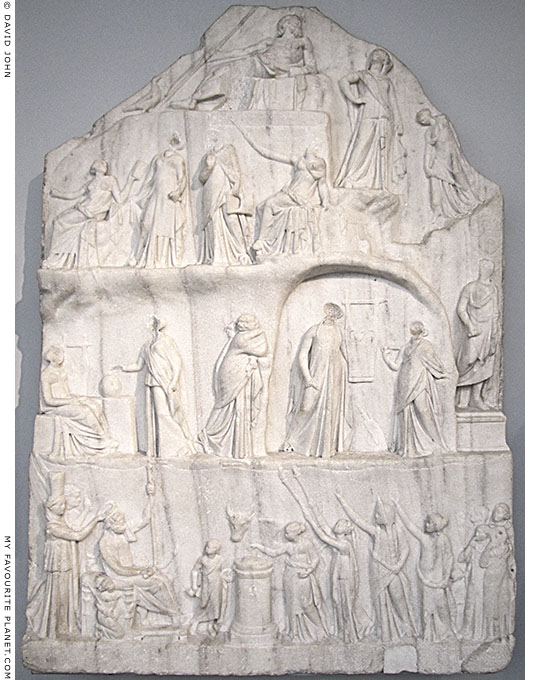

"The Apotheosis of Homer" Hellenistic marble relief.

3rd or 2nd century BC. Said to have been found on the Via Appia at Bovillae, Lazio,

central Italy, in the mid 17th century. Until 1819 in Palazzo Colonna, Rome.

Parian marble. Height approximately 121 cm, approximately width 76 cm. [19]

British Museum. GR 1819.8-12.1 (Sculpture 2191, Inscription 1098).

Purchased from Messrs May in 1819.

|

Also known as "the Relief of Archelaos", signed by the sculptor Archelaos, son of Apollonios of Priene, it is thought to have to have been made in Alexandria, Egypt in the 3rd or 2nd century BC, perhaps during the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopater (222-205 BC) and his queen (sister and wife) Arsinoe III Philopater, who built a temple of Homer in the city. It has been suggested that the relief may have been a prize awarded to a poet, and even that the poet shown standing on a pedeatal (see number 13 in the key below) may be meant to represent the winning bard.

The religious ceremony in which Homer is elevated to divine status by deities, Muses, mythical characters and personifications was a popular subject in the art of antiquity. [20] Here some of the participants are identified by captions in inscribed in Greek below the respective figures (see drawing below):

Οἰκουμένη (Oikoumene, Inhabited World), Χρόνος· (Chronos, Time), Ἰλιάς (Ilias, The Iliad),

Ὀδύσσεια· (Odysseia, The Odyssey), Ὅμηρος· (Omeros, Homer), Μῦθος (Mythos, Myth),

Ἱστορία (Ostoria, history), Ποίησις· (Poiesis, Poetry), Τραγῳδία (Tragodia, Tragedy),

Κωμῳδία· (Komodia, Comedy) Φύσις (Physis, Nature), Ἀρετή (Arete, Virtue),

Μνήμη (Mneme, Memory), Πίστις (Pistis, Good Faith), Σοφία (Sophia, Wisdom).

The bard (Omeros, Homer), enthroned before an altar, holds a sceptre and a scroll. The two smaller-scale figures at Homer's side and directly in front of him, have been identifed as The Iliad (Ilias) and The Odyssey (Odysseia) respectively, perhaps as his "children". The scene is observed from above by Zeus, reclining on a rock (or cloud?), immediately below which is a panel containing the inscribed signature of the sculptor. The seated female figure below (perhaps the Muse Euterpe) appears to point to it with her raised right hand.

Ἀρχέλαος Ἀπολλωνίου

ἐποίησε Πριηνεύς

Archelaos, son of Apollonios,

made it, of Priene.

Inscription IG XIV 1295.

It is thought that Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III may be portrayed standing behind Homer, as Chronos (Time) and Oikoumene (Inhabited World), who is crowning the poet.

The Roman author Aelian (Κλαύδιος Αἰλιανός, Claudius Aelianus; circa 175-235 AD) mentioned Ptolemy Philopater's temple and statue of Homer, as well as a satirical drawing by the artist Galaton.

"Ptolemaeus Philopator having built a Temple to Homer, erected a fair Image of him, and placed about the Image those Cities which contended for Homer. Galaton the Painter drew Homer vomiting, and the rest of the Poets gathering it up."

Claudius Aelianus, Various History, Book 13, chapter 22. At James Eason's website, Penelope, University of Chicago.

See also an inscribed marble relief in honour of Euripides, the Athenian playwright. |

|

| |

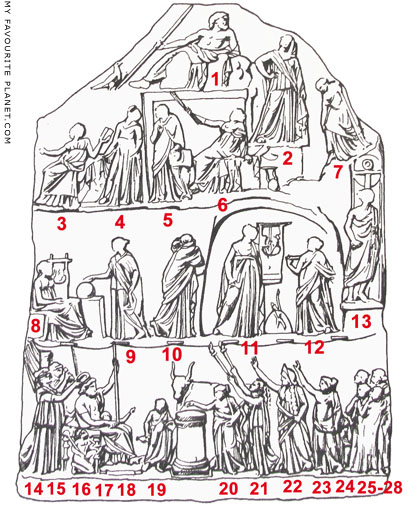

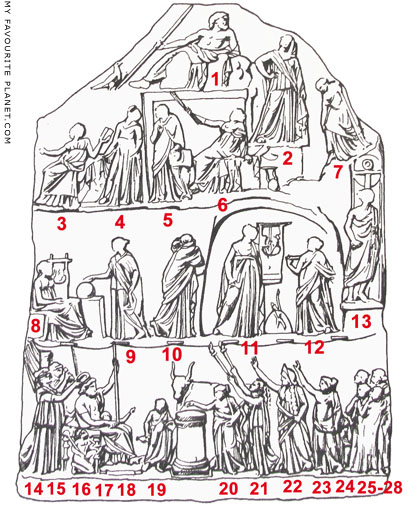

| Key to the Apotheosis of Homer |

| |

|

Tier 1 |

1 Zeus, reclining on a rock or cloud, with his eagle

2 Mnesmosyne ?, mother of the Muses by Zeus |

| Tier 2 |

3 Muse (Klio ?)

4 Muse

5 Muse (Erato ?)

6 Muse (Euterpe ?)

7 Muse |

| Tier 3 |

8 Muse (Terpsichore ?) with lyre

9 Muse (Ourania ?) with the celestial globe (?)

10 Muse (Polyhymnia ?)

11 Apollo Kitharoidos, standing by an omphalos in a cave

12 Muse

13 statue of a poet ? * on a pedestal (perhaps Apollonius,

author of the Argonautica, 2nd century BC) |

| Tier 4 |

14 Oikoumene (Arsinoe III) ? wearing a tall polos, crowning Homer

15 Chronos (Ptolemy IV) ? behind 14

16 The Iliad, as a child, kneeling at the near side of the throne

17 Homer, enthroned

18 The Odyssey, as a child, in the far side of the throne (only her head and raised arm are visible)

19 Mythos (Myth), as a child

A cylindrical altar, behind which stands a sacrificial bull or ox

20 Istoria (History)

21 Poiesis (Poetry), holding two torches

22 Tragodia (Tragedy)

23 Komodia (Comedy)

24 Physis (Nature), as a child

25 Arete (Virtue) standing in a tight group with 26, 27 and 28

26 Mnem(e) (Memory)

27 Pistis (Good Faith)

28 Sophia (Wisdom) |

|

| |

Detail of the Apotheosis of Homer, British Museum. |

| |

Part of a marble statue representing

the personification of The Iliad.

2nd century AD. The identification of the

statue is based on an inscribed base

found with it (IG II² 2776). Height 143 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 2038. |

|

Part of a marble statue representing

the personification of The Odyssey.

2nd century AD. Height 129 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 2039. |

|

| |

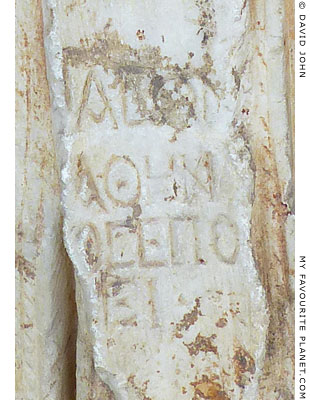

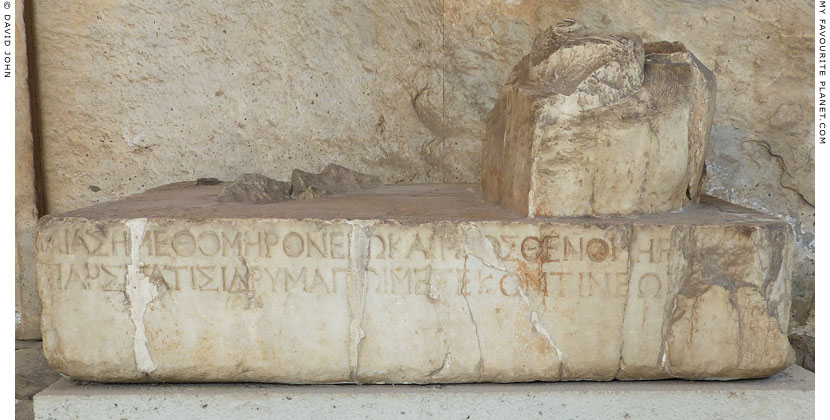

The two statues were found in 1869, during excavations by the Greek Archaeological Society in Athens, built into the walls of the now demolished Church of Panagia Pyrgiotissa (Παναγία Πυργιώτισσα or Chrysopyrgiotissas, εκκλησίας της Χρυσοπυργιώτισσας), constructed in the northern tower of a gate in the Post-Herulian Wall [21], at the south end of the Stoa of Attalos in the Athenian Agora. They were identified as personifications of The Odyssey and The Iliad about twenty years later by the German archaeologist Georg Treu, who also suggested that the object on the left shoulder of the Odyssey may have been part of an acplaston (steering oar). [22]

They are thought to have stood in the Library of Pantainos (Βιβλιοθήκη Πανταίνου), built around 100 AD, just west of the Gate of Athena, the Doric gateway of the market of Caesar and Augustus (also known as the Roman Agora), immediately south of the Stoa of Attalos. [23] The statues were in National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Inv. Nos. 311 and 312) until August 1958 when they were transferred to the Agora Museum.

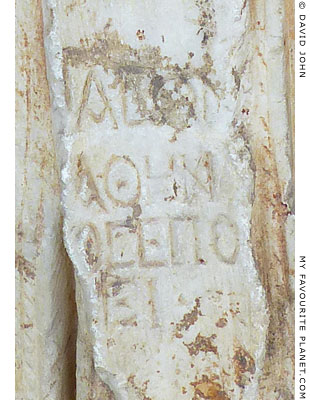

Each of the statues, now missing heads, forearms and legs, was carved from a single piece of Pentelic marble. Each depicts a figure wearing military garb, including a cuirass (breastplate) and cloak. They are both described as being female figures, but although the Odyssey (right) obviously has a right breast, the gender of the Iliad is not easily distinguishable. The Odyssey's cuirass is decorated with reliefs depicting characters from The Odyssey (see photo below), and her pleated skirt is inscribed with the sculptor's signature (see photo right):

ΙΑCΩΝ

ΑΘΗΝΑ[Ι]

ΟC ΕΠΟ[Ι]

ΕΙ

(Ἰάσων Ἀθηνα[ῖ]ος ἐπο[ί]ει.)

Jason the Athenian made it

Inscription IG II² 4313.

In 1953 archaeologists of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) discovered fragments of an inscribed base believed to belong to the Iliad statue (see photo below) in a Byzantine period well near the east end of the Middle Stoa of the Agora. The well had been constructed with ancient stones including fragments of sculpture, inscriptions and architectural members, among them bases and capitals apparently from the Gymnasium, built in this area around 400 AD. Also found were part of a life-size left foot in a heavy boot and a non-fitting left leg, thought to belong to the statue. The statue base of Pentelic marble was reconstructed from over sixty fragments, and the inscribed distich on the front was reconstructed by the American archaeologist Homer A. Thompson to read:

λιὰς ἡ μεθ' Ὅμηρον ἐγὼ καὶ πρόσθεν Ὁμήρ[ωι]

πάρστατις ἵδρυμαι τῶι με τεκόντι νέω[ι].

The Iliad, I that was both after Homer and before Homer,

have been set up alongside him that bore me in his earlier years.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. I 6628. Inscription SEG 29:192.

Thompson pointed to an ancient view that Homer wrote The Iliad in his youth and The Odyssey in his old age, citing a passage by Longinus (On the Sublime, 9, 13). He also suggested that the figures may have been part of a group, and stood either side of a larger scale statue of Homer seated "with sceptre and scroll in his hands".

See: Homer A. Thompson, Excavations in the Athenian Agora: 1953, The Iliad base. In: Hesperia, Volume 23 (1954), No. 1, pages 62-65. PDF at ascsa.edu.gr. With bibliographical references and a photo of the base (plate 14c).

According to one theory, the statue of The Iliad may have originally stood next to a statue of the Athenian general (and perhaps poet) Gaius Iulius Nikanor (Ἰούλιον Νικάνορα, 1st century BC), a friend of Emperor Augustus. The pentameter on the base would then refer to the older Homer, the author of The Iliad, and the "New Homer" ("νέον Ὅμηρον", Neos Homeros) identified as Nikanor, who is known from inscriptions from the Athens Acropolis, Piraeus and Eleusis (IG II² 3786-3789 and I.Eleusis 362) to have been honoured by the Athenians as "the New Homer and New Themistokles".

Nikanor's 1st century BC statue may have later been placed in the Library of Pantainos and added to a group which included the 2nd century AD statues of The Iliad and The Odyssey.

See: Antony E. Raubitschek, The new Homer. In: Hesperia, Volume 23, No. 4 (October-December 1954), pages 317-319. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. PDF at ascsa.edu.gr. |

|

The signature of the sculptor Jason

the Athenian on the Odyssey statue. |

|

| |

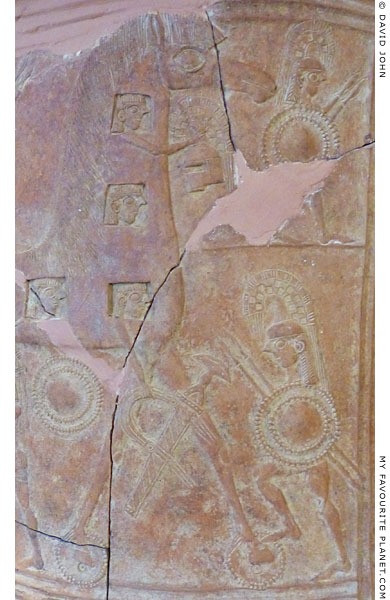

The cuirass of the Odyssey statue in the Athens Agora, decorated with reliefs depicting

characters from The Odyssey. On the cuirass itself, in the centre below the breast is Skylla.

On the upper row of lappets, from left to right: Aiolos, three Sirens, Polyphemos. Two of the

lower row of lappets are missing, but on the three preserved lappets are a helmet, a ram's

head and a winged thunderbolt. The artist's signature is inscribed on one of the long

pendents on the figure's left side, below the lappets.

Lappets are decorative flaps, folds or hanging parts of a garment or headdress. They are also

referred to as pteruges (or pteryges; from Greek, πτέρυγες, feathers), strips of leather or other

material attached to Greek and Roman armour to protect the upper arms or legs. They were

often covered by metal plaques decorated with reliefs, as seen on portrait statues of emperors.

For further information about Polyphemos, Skylla and the Sirens in The Odyssey, see Homer part 3. |

| |

The restored fragments of the inscribed base of the statue of The Iliad.

2nd century AD. Pentelic marble. Height in front 19.5 cm,

width circa 90.2 cm, depth front to back 78.5 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. I 6628. |

| |

A restored bust of Homer on a Roman period floor mosaic from the "Villa of the Muses

and Poets" (named after the mosaic) in Gerasa (Γέρασα), today Jerash, Jordan.

Late 2nd - early 3rd century AD. Natural stone and glass tesserae. Restored 1979-1980.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Mos. 73. Acquired in 1908. Previously in the Pergamon Museum.

|

Part of a large polychrome floor mosaic, measuring around 380 x 440 cm, from a rectangular room of the villa, thought to have been a triclinium (dining room). It was discovered by chance in 1907 by a Circassian family living in the ruins of the ancient city, and excavated between 1907 and 1935. The twenty two fragments of the floor now in the Berlin State Museums (SMB) were purchased in 1908, following the first excavation by Gottlieb Schumacher, and parts uncovered subsequently are in other museums and private collections. [24]

The floor mosaic had a 20 cm wide frame with a continuous guilloche pattern, enclosing a wider border within which ran a series of busts of Muses alternating with ancient Greek writers, including Homer, Thucydides (see the bust on the Thucydides page), as well as the poets Anakreon, Alkman and Stesichoros. Each of the busts is shown above part of a long garland, continuous along each side of the border, festooned with leaves and fruit (in this case pine cones), supported by Erotes (Cupids) and hung with theatre masks. Various birds stand on the garland, flanking the busts. To the left of Homer's head is what appears to be a parakeet (see a mosaic of an Alexandrine parakeet Pergamon gallery 2, page 12), and to the right a duck. At each of the four corners of the border was a round medallion containing a bust of one of the Seasons (Horai).

The centre of the mosaic is thought to have been divided into four large emblemata (panels) with depictions of Dionysian scenes with several figures: one surviving emblema shows a Triumph of Dionysus (see the Dionysus page), and another a Dionysian procession with a drunken Herakles among Satyrs, Silens and Maenads.

The Dionysian themes and the presence of the Muses has led to the suggestion that the villa's owner may have had some connection with the theatre. However, none of the surviving busts portray playwrights, and apart from the actors' masks there is no specifically theatrical imagery. It may be more likely that the central panels reflect the use of the room for symposia (drinking parties), and the Muses and writers were meant to broadcast the owner's claim to literary taste.

Homer's name in Greek is written in black tesserae, in two parts, ΟΜΗ ΡΟC (OME ROS), to either side of his head. Much of the head has been restored, and in its present state does not appear similar to surviving sculpture portraits of the poet; it may have been a product of the mosaic artist's imagination or copied from unknown work, perhaps a painting. He is depicted as a middle-aged man with long dark hair and greying beard, his head turned slightly to face the viewer's left. He wears a white chiton (tunic) and a himation (cloak) over his shoulders. The mosaic fragments in the museum are currently displayed in a large glass cabinet and it is difficult to see whether Homer's eyes have been given irises. In contrast to the detailed and highlighted eyes of all the other faces in the border, including that of Thucydides and the masks, Homer's eye sockets appear dark and empty, and he may have been depicted as blind.

Among the puzzling aspects of this floor decoration is the fact that on the outer border all the portraits face the outside of the mosaic area. In order to appreciate the images and read the inscriptions, the viewer in the villa would have had to stand or sit on the narrow guilloche frame, which was at the edge of the floor next to the walls of the room. Usually the floor would have been covered by dining couches and other furniture, and perhaps carpets. This also applies to other floor mosaics in private homes, leaving us to wonder why their owners went to so much expense commissioning or buying works of art they seldom saw. |

|

| |

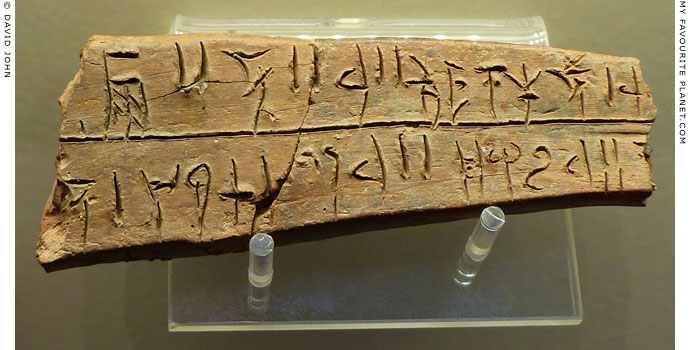

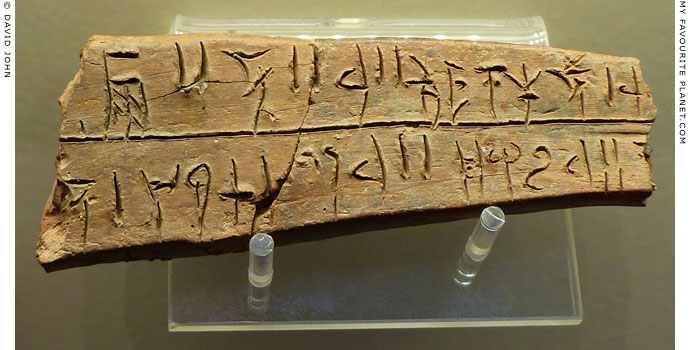

A fragment of a clay tablet inscribed in Linear B script,

mentioning "the man from Troy" (to-ro-wo; Greek, Τρωας).

13th century BC. From the archives of the Mycenaean

palace of Thebes, Boeotia, central, Greece.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

to-ro-wo = the man from Troy

|

In The Iliad Homer referred to the besieged fortified city of Priam as Ilion (Ἴλιον, Ilion, or Ἴλιος, Ilios; Latin, Ilium), hence the title of his poem (ἡ ποίησις Ἰλιάς, the poem of Ilion). He also wrote of Troy (Τροία, Troia, or Τροίας, Troias; Latin, Troia), sometimes referred to as the Troad (Τρωάδα, Troada), the area around the city, the homeland of the Trojans. The names were later confounded and both used to refer to the city and the surrounding country.

The names are thought to be derived from the Hittite Wilusa and Truwisa. However, Homer provided a typically Greek geneaology of a local royal dynasty to explain the names, starting with Dardanos (Δάρδανος), a son of Zeus and founder of Dardania (Δαρδανία), the city and area at the northwestern edge of Anatolia, south of the western entrance to the Dardanelles (Δαρδανέλλια, later known as the Hellespont, Ἑλλήσποντος), the straits between the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara. His son King Erichthonius (Ἐριχθόνιος) was the father of Tros (Τρώς or Τρωός), after whom Troy and the Trojans were named. In turn, Ilos (Ἶλος), a son of Tros and grandfather of Priam, founded Ilion, the city of Ilos.

Just before he is about to fight the Achilles, the Trojan prince Aeneas boasts to the Greek hero of his illustrious lineage.

"Howbeit, if thou wilt, hear this also, that thou mayest know well my lineage, and many there be that know it:

At the first Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, begat Dardanus, and he founded Dardania, for not yet was sacred Ilios builded in the plain to be a city of mortal men, but they still dwelt upon the slopes of many-fountained Ida. And Dardanus in turn begat a son, king Erichthonius, who became richest of mortal men.

Three thousand steeds had he that pastured in the marsh-land; mares were they, rejoicing in their tender foals. Of these as they grazed, the North Wind [Boreas] became enamoured, and he likened himself to a dark-maned stallion and covered them; and they conceived, and bare twelve fillies. These, when they bounded over the earth, the giver of grain, would course over the topmost ears of ripened corn and break them not, and whenso they bounded over the broad back of the sea, would course over the topmost breakers of the hoary brine.

And Erichthonius begat Tros to be king among the Trojans, and from Tros again three peerless sons were born, Ilus, and Assaracus, and godlike Ganymedes that was born the fairest of mortal men; wherefore the gods caught him up on high to be cupbearer to Zeus by reason of his beauty, that he might dwell with the immortals.

And Ilus again begat a son, peerless Laomedon, and Laomedon begat Tithonus and Priam and Clytius, and Hicetaon, scion of Ares. And Assaracus begat Capys, and he Anchises; but Anchises begat me and Priam goodly Hector. This then is the lineage amid the blood wherefrom I avow me sprung."

Homer, The Iliad, Book 20, lines 213-240. At Perseus Digital Library.

The name Erichthonius is also known in connection with the ancient history of Athens (see Athens Acropolis gallery, page 18). In Greek myth Ganymede (Γανυμήδης) was abducted by Zeus, a popular subject in ancient Greek and Roman art. Zeus, sometimes depicted as an eagle, was said to have carried away the handsome youth from Mount Ida (Όρος Ίδη or Ἴδα; Turkish, Kazdağı, Goose Mountain) near Troy. Boreas (Βορέης or Βορίας), the North Wind, was also depicted in Greek art (see Homer part 3).

The archaeological site today identified as Troy (Turkish, Truva or Troya), famously excavated by Heinrich Schliemann between 1871 and 1883, is at Hisarlik, Çanakkale province, in the Southern Marmara Region of Turkey. It is around 30 km southwest of the provincial capital Çanakkale. The Troad is believed to be area around what is now called the Biga Peninsula (Turkish, Biga Yarımadası). |

|

| |

A depiction of a ship on a Middle Bronze Age, matt-painted ceramic pithos (large storage

vessel) from Aegina. Four manned, crescentic (crescent-shaped) ships with bifurcated

sterns (at the right end of the ship above) are shown around the body of the restored

vase, in the central zone. In the registers above and below are typical geometric motifs.

The ships are thought to be warships, perhaps used for pirate activities in the Aegean.

1800-1650 BC. Excavated at Aegina-Kolonna (Town IX), Greece.

Aegina Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2458. |

| |

A fragmentary ceramic dinos (wine bowl) with a depiction of

a ship with oarsmen and a helmsman (naukleros) at the tiller.

On the right a bearded man disembarks onto the land.

Archaic period, late 7th century BC. Excavated at the

Sanctuary of Herakles, Thebes, Boeotia, central Greece.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Homer

part 1 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Head of Homer found at Baiae, Italy

Marble herm bust with an imaginary portrait of the poet Homer as an elderly blind man, with Greek letters carved on each side of the terminus.

White marble. Height: 57.15 cm (22.5 inches).

British Museum, London.

Main floor, Room 22, Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic world.

Inventory Number GR 1805.7-3.85 (Sculpture 1825).

Thought to be a Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original of the 2nd century BC. It belongs to the so-called "Hellenistic blind type" or "Pergamon type" of depictions of Homer, the style of which has been compared with the sculpted figures of the Gigantomachy frieze on the Great Altar of Pergamon (circa 175 BC). The original of the type may have been created for a statue which stood in the Pergamon Library. See also the base of a statue of Homer from Pergamon above.

The bust is in the form of a "terminus", i.e. the top part of a herm. Terminus was the Roman god who protected boundaries, and stone pillars known in Latin as terminii were set up as boundary markers in a similar way to which herms were used by the Greeks. Such busts of gods and famous humans were made for the private collections of wealthy people. See more about herms on Pergamon gallery 2, page 15.

It was found in 1780 among the ruins of the ancient city of Baiae, on the Bay of Naples, Italy. It was purchased in late 1780 for £80 by the wealthy English collector Charles Townley (1737-1805) from the Scottish painter, antiquarian and antiquities dealer Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798). It was acquired, along with around 300 ancient artefacts of the Townley Collection, by the British Museum after Townley's death.

See:

Taylor Combe, William Alexander, George Cooke, A description of the collection of ancient marbles in the British Museum: with engravings. [Marbles in the third room of the Gallery of Antiquities] Part II. W. Bulmer and Co., London, 1815.

G. M. A. Richter, The portraits of the Greeks. Phaidon, London, 1965.

Examples of "Hellenistic blind type" heads of Homer in major collections (including those shown on this page):

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Inv. No. 04.13.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Inv. No. 2818.

Archaeological Museum, Florence. Inv. No. 1646.

Walker Art Gallery Liverpool. Inv. No. 10341 (half sized; possibly modern).

British Museum, London. Inv. No. 1805.7-3.85 (Sculpture 1825).

Prado, Madrid. Inv. No. E00076.

Palazzo Ducale, Mantua. Inv. No. 75.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6023.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 440.

Sanssouci, Potsdam.

University Art Museum, Princeton. Inv. No. 62.134.

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 557.

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 558.

Hall of the Philosophers, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 559.

Galleria Geografica, Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 2890.

Villa Albani, Rome. Inv. No. 721.

Staatliches Museum, Schwerin. Inv. No. 1900.

Biblioteca Capitolare, Salone Capitolare, Verona.

Wilton House, Wiltshire.

2. The gem portrait of Homer

Image source: Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907), Die Antiken Gemmen: Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst im Klassischen Altertum, Band 1 (of 3): Tafeln (The antique gems: History of the art of stone engraving in classical antiquity, Volume 1, Plates), plate LXVI, 9. 1900. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. The link is to a webpage on which all three volumes of the work can be read online or downloaded as PDFs. The descriptions of the gems illustrated in the plates of Volume 1 can be read in Volume 2 (in German).

Alfred Morrison (1821-1897) inherited a considerable fortune, and like his father had a passion for collecting a variety of objects, including autographs, art and gems. It is not known when, where or how he acquired the Homer intaglio. After his death his collections were sold off.

From the catalogue of the sale by auction of the Homer gem among other artifacts from the Alfred Morrison Collection:

"96. Head of Homer, facing, upon a nicolo, of fine work and very deeply cut - Plate I."

Christie, Manson and Woods, London, 29-30 June 1898: Catalogue of the valuable and important collection of Camei, Intagli, Gold Rings, Egyptian Vases in Hardstone, Ancient Greek Vases, Glass etc., including a few statuettes from Tanagra, and a Remarkable Glass Bottle of Venetian Work of the 16th century; richly decorated in gold, formed by Alfred Morrison, Esq., deceased, late of 16 Carlton House Terrace, London, S. W. and Fonthill, Tisbury, Wilts, Plate I, No. 96; text on page 14. At googlebooks. E-book available. (Interestingly, this is a scan of a copy from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

The Homer gem thereafter entered the considerable collection of antiquities acquired by Sir Arthur John Evans (1851-1941), the wealthy British archaeologist who first excavated the Minoan palace complex at Knossos on Crete. He also helped the Ashmolean Museum, of which he became keeper (director), to enlarge its inventory. Much of his personal collection was gifted or bequeathed to the museum, but it turned out that many pieces were forgeries.

The provenance of Morrison's Homer gem is unknown, but it is clear that a large number of so-called "antique" gems on the market and in private collections in the 19th and early 20th centuries were modern fakes. The German archaeologist, historian and museum curator Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907) was convinced the Homer nicolo was "sicher antik" (certainly antique).

However, considering the piece was therefore unique, it does not seem to have attracted much attention. Evans published his own slim volume in 1938, presenting a small selection of antique gems he had "acquired through over sixty years of travel and research in Crete, Mainland Greece, the East Adriatic Coastlands, Sicily, and Magna Graecia", but also some that he had purchased from private collections. In the introduction he made a point of defending their authenticity, comparing his efforts to those of William Martin Leake.

"Of the present Collection - or more rightly 'Selection' - of Ancient Gems it may at least be said that it essentially differs from the ordinary class of collections such as have come under the hammer. It is not the mere product of sale purchases, taken from catalogues, where in nine cases out of ten the original find-spots of the specimens are unrecorded. A few choice examples have been acquired from earlier Collections, such as the Marlborough (including specimens from the Arundel and Praun), the Morrison, and Maskelyne, with some from the recent Guilhou sale. But, as in the case of the Leake Collection, the great bulk of the series has been preeminently the result of almost life-long travel research in those Mediterranean lands that had formed the original cradle of artistic gem-engraving - Crete heading the list."

He also emphasized his connoiseurship, attributing it to the training he received from his father and his keen eye.

"For judgement in such matters, moreover, I had had the advantage of training, from a much a much earlier age, under my father, Sir John Evans, in the artistically and historically kindred study of Numismatics. Nature, too, had given me microscopic vision."

Sir Arthur Evans, An illustrative selection of Greek and Greco-Roman gems: to which is added a Minoan and proto-Hellenic series. Privately printed at the University Press, Oxford, 1938. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Perhaps strangely, although he included other pieces from the Morrison Collection, the Homer gem is not even mentioned, neither did it appear in the 1938 exhibition of his gems in Oxford and the Worcester Art Museum, for which this book was presumably written (although there is also no mention of an exhibition in the volume). It also seems that there was no cast made of the gem for the Beazley Archive in Oxford.

Scholars such as Gisela Marie Augusta Richter (1882-1972) have been unable to discover the gem's whereabouts, and if it was sold, either by Evans or after his death, there appears to be no record of its sale. According to one theory, it may have remained in the possession of his daughter. So long as it remains unfound, its authenticity can not be tested.

See:

Gemme mit Portraitbüste des Homer (?) en face (in German) at arachne.dainst.org.

Gisela Marie Augusta Richter, The engraved gems of the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans. Part 2: Engraved gems of the Romans. A supplement to the history of Roman art, page 84, No. 410. Phaidon Press, London, 1971. At the Internet Archive.

Gisela Marie Augusta Richter, The Portraits of the Greeks, Volume 1, fig. 124. Phaidon Press, London, 1965.

Two other gems featuring portraits of Homer - a sardonyx and a cornelian - appear to be modern fakes, among the 2500 or so gems commissioned by Prince Stanislas Poniatowski (1754-1833), who "encouraged the belief that they were, in fact, ancient".

See the following entries on the Beazley Archive website:

The Poniatowski Collection of gems

1839-2515, [Frontal bust of] Homer

1839-2516, Homer and Demosthenes

3. The "Epimenides type" Homer

The "Epimenides type" head of Homer is named after the first known example, the herm bust in the Museo Pio-Clementino shown here. This was at first named the "Sleeping Epimenides" and believed to depict the 7th century BC Cretan philosopher Epimenides, following a proposal by the Italian antiquarian and art historian Ennio Quirino Visconti (1751-1818), papal Prefect of Antiquities. It was first identified as Homer by the archaeologist Franz Winter (1861-1930) in 1890, and subsequently by Adolf Furtwängler.

All known examples of the type are believed to have been made in the Roman period as copies of a prototype speculatively dated around 460 BC, due to the style of the carving and the features. This period would coincide with the earliest known statue of Homer which, according to Pausanias, was dedicated by Mikythos at Olympia [see above and note below].

Apart from the examples of the type shown on this page, others include:

Vatican Museums, Rome. In storage. Inv. No. 7112;

Rome, Torlonia Collection, Rome. Inv. No. 163;

State Historical Museum, Moscow (half-size).

4. Lycurgus, Peisistratos and Homer

Diogenes Laertius (Διογένης Λαέρτιος, 3rd century AD), a biographer of Greek philosophers, credited the Athenian statesman, lawmaker and poet Solon (Σόλων, circa 630-560 BC, archon 594 BC) with the introduction of public recitations of Homer to Athens.

"He [Solon] has provided that the public recitations of Homer shall follow in fixed order: thus the second reciter must begin from the place where the first left off. Hence, as Dieuchidas says in the fifth book of his Megarian History, Solon did more than Pisistratus to throw light on Homer. The passage in Homer more particularly referred to is that beginning 'Those who dwelt at Athens ...' [Iliad, Book 2, lines 546-558]"

Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book 1, chapter 2, section 57. At Perseus Digital Library.

The subject of early written forms of Homer's works, and the alleged part played by Lycurgus, Peisistratos and others, is too large and involved to go into deeply here. A number of scholars have discussed it in various articles and books.

Having pointed out the late appearance of reports of Lycurgus' involvement, scholars still cite even later commentators, such as the Byzantine poet and grammarian John Tzetzes (Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, circa 1110-1180), and other Medieval witers of scholia (commentaries on literary works). They recorded the tradition that the editor of the "Peisistratean recension" was Onomakritos (Ὀνομάκριτος), thought to be the person mentioned by Herodotus as an Athenian diviner or compiler of oracles and close friend of Hipparchos (Histories, Book 7, chapter 6, sections 3-4), and by Pausanias as a poet (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 22, section 7; Book 8, chapter 31, section 3, and chapter 37, section 5).

The Syrian theologian Tatian (Τατιανός, circa 120-180 AD) wrote that Onomakritos was the author of the songs of Orpheus.

"And Orpheus lived at the same time as Hercules; moreover, it is said that all the works attributed to him were composed by Onomacritus the Athenian, who lived during the reign of the Pisistratids, about the fiftieth Olympiad [580 BC, too early]. Musaeus was a disciple of Orpheus."

Tatian, Address to the Greeks, section 41 (Oratio ad Graecos). At ToposText.

(The same quote appears in Eusebius, Preparation of the Gospels, § 10.11.2, also at ToposText.)

5. Xenophanes on Homer

The works of Xenophanes of Colophon are known only from fragments quoted by later writers and commentators, including the biographer Diogenes Laertius (Διογένης Λαέρτιος, Diogenes Laertios; circa 3rd century AD).

"Xenophanes, a native of Colophon, the son of Dexius, or, according to Apollodorus, of Orthomenes, is praised by Timon, whose words at all events are:

'Xenophanes, not over-proud, perverter of Homer, castigator.'

His writings are in epic metre, as well as elegiacs and iambics attacking Hesiod and Homer and denouncing what they said about the gods."

R.D. Hicks, Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book 9, chapter 2, section 18. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1972 (First published 1925). At Perseus Digital Library.

Fragments criticizing the portrayal of the gods by Homer and Hesiod:

Fragment B11

"Homer and Hesiod have attributed to the gods all sorts of things that are matters of reproach and censure among men: theft, adultery, and mutual deception."

Fragment B12

"...as they sang of numerous illicit divine deeds: "theft, adultery, and mutual deceit."

Xenophanes. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2002.

6. Pausanias on the Thebais, Calaenus and Homer

When discussing the earliest mention of Homer in ancient literature, many modern authors cite a single mention in Pausanias in which an epic poem titled Thebais (Θηβαΐς), about the legendary war between Argos and Thebes, was attributed to Homer by Calaenus (Κελαινός, Kelainos). Pausanias gives us no further information about this person, who appears to be otherwise unknown.

"And this is the war which is celebrated in verse. Calaenus, making mention of these verses, says that they were composed by Homer; and many celebrated persons are of the same opinion. Indeed, I consider these verses as next in excellence to the Iliad and Odyssey. And thus much concerning the war, which the Argives and Thebans waged for the sake of the sons of Oedipus."

Pausanias, The description of Greece, Volume III (of 3), translated by T. Taylor, Book 9, chapter 9, page 19. Richard Priestley, London, 1824. At googlebooks.

However, the translations most referred to by scholars render the name as Callinus (Καλλῖνος, Kallinos), the name of a Greek elegiac poet who lived in Ephesus in the mid 7th century BC. Presumably, when the translators came across the unknown name Calaenus, they considered it an error or corruption and conjecturally substituted it with that of Callinus, who is known to have written poems about war; he may have seemed more fitting and had the added advantage of living at a time closer to Homer, which would give his opinion on the authorship of the Thebais more credibility.

No mention of the Thebais has been found among the surviving fragments of Callinus' works. Although Peter Levi also translated the name as Kallinos, he pointed out in his notes, that "this casual reference is not among his surviving work" (Pausanias, Guide to Greece 1: Central Greece, page 327, note 49. Penguin Classics, 1979).

This error was pointed out by the classics professor John Adams Scott as early as 1921, but few seem to have noticed.

"Not a single manuscript has the word Callinus in this place, but all have Calaenus, so that Callinus is simply an emendation. The word Callinus is a pure conjecture."

John Adams Scott, The Unity of Homer, pages 15-16. Sather Classical Lectures Volume I. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, 1921. At the Internet Archive.

Scott made the same argument in: John A. Scott, Homer as the Poet of the Thebais, Classical Philology, Vol. 16, No. 1 (January 1921), pages 20-26. University of Chicago Press. At Jstor.

The subject of the Thebais was the war for the kingship of Thebes between the brothers Eteocles and Polyneikes (Polynices), sons of Oedipus, in which Polyneikes was supported by King Adrastos of Argos. The content of the poem is known only from a handful of fragments, short quotes and mentions in the works of later writers, none of which are very enlightening. One fragment mentions Homer as the author:

"Homer travelled about reciting his epics, first the Thebaid, in seven thousand verses, which begins: 'Sing, goddess, of parched Argos, whence lords...'"

Hugh Gerard Evelyn-White (translator), Hesiod, the Homeric hymns and Homerica, Thebais, pages 484-487 (seven fragments in Greek and English). William Heinemann, London; Macmillan Co., New York. 1912. At the Internet Archive.

See also: Gottfried Kinkel, Epicorum graecorum fragmenta Volume I, pages 9-13. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1877. At the Internet Archive.

The story of the Theban War became more widely known from Aischylos' play Seven against Thebes, produced in 467 BC. The Thebais is also known from later versions by other poets, including Antimachus (Ἀντίμαχος, Antimachos of Colophon or Claros, flourished about 400 BC, a pupil of Panyassis), and the Latin Thebaid of Publius Papinius Statius (circa 45-96 AD).

The elegiac poet Sextus Propertius (circa 50-15 BC) appears to be referring to a poem on the Theban War by Homer in a Latin elegy addressed to Ponticus (a contemporary of Ovid), who wrote on the same subject:

"While you tell of Thebes and Cadmus, Ponticus,

and the tragedy of fraternal warfare,

and, if I may say, you contend with Homer himself

(may the fates just go easy on your songs),

I pursue my loves, as is my wont,

and look for something against my hard mistress."

Vincent Katz (translator), Sextus Propertius, Elegies, Book I, Elegy VII. Sun and Moon Press, Los Angeles, 1995. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Herodotus on Hesiod and Homer

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 2, chapter 53, translated by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press, 1920. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Iliad and The Odyssey are mentioned in Book 2, chapters 116-117, and Book 4, chapter 29. At Perseus Digital Library.

8. Aulus Gellius on Homer's native city

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights (Noctes Atticae), Book III, Chapter 11. English translation at Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

9. Seven cities contend for the birth of Homer ...

Ἑπτὰ πόλεις διερίζουσιν περὶ ῥίζαν Ὁμήρου,

Σμύρνα, Ῥόδος, Κολοφών, Σαλαμίς, Ἴος, Ἄργος, Ἀθῆναι.

These two lines have been quoted innumerable times without citations or references. One source attributes the epigram to Antipater of Sidon. It has also been paraphrased by several authors, including Vasari and the English playwright and poet Thomas Heywood.

"... even as seven cities contended for Homer, each claiming that he was her citizen..."

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), Lives of the artists (first published in 1550), Part III, "Life of Baldassare Peruzzi painter and architect of Siena".

"Seven cities warr'd for Homer, being dead;