The 57.5 cm high marble bust from a herm of Homer (Ὅμηρος, Homeros), now in the British Museum, London (top of page), was found in 1780 among the ruins of the ancient city of Baiae, on the Bay of Naples, Italy [1]. It is thought to be a Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original of the 2nd century BC. It belongs to the so-called "Hellenistic blind-type" of depictions of Homer (see photos right), which has been compared with figures of the friezes on the Great Altar of Zeus; the original of the type may have been created for the Pergamon Library (see gallery 2, page 20).

We have no idea what Homer really looked like, since the time in which he is thought to have lived (anywhere between the 12th and 6th centuries BC, depending on whose theory you believe, but most probably around 750 to 700 BC) was long before realistic portraiture was practised by the Greeks. Not only that, it is doubted by some scholars that he ever existed at all. Notwithstanding, four Greek cities in Asia Minor, Smyrna, Chios, Kolophon and Kyme, claimed the bard as a native son.

Sculptures of the legendary poet were made as early as the Classical period, representing him as a scholarly, elderly, blind man. These works were placed in libraries and sanctuaries, a tradition which continued into Roman times. There was also a sculpture of this type in the Homereion of Alexandria, a centre for Homeric studies during the Hellenistic period. [2]

Around the end of the 5th century AD, the Egyptian poet Christodorus described a bronze statue of Homer in the Baths of Zeuxippus in Constantinople:

"... the features of an old man, but of a gentle old age, so much so that it gives him an even richer aura of grace: a mix of venerability and admiration, but from which prestige shines through... With his two hands supported by his staff, one on top of the other, like a real man. The right ear bent, as if always listening to Apollo, almost as if he could hear a Muse nearby..."

Anthologia Palatina, II, 311-349 [3]

The two epic narrative poems Homer is credited with writing, the Iliad (Ιλιάς) and the Odyssey (Ὀδύσσεια), tell of legendary heroic events around the time of Bronze Age conflicts between Greeks and Anatolians, distilled into the story of the siege of Troy; and seaman's yarns of pioneer Greek military and merchant sea voyages around the Mediterranean, synthesized into the wanderings of Odysseus.

The question of how much was based on historical fact and/or age-old story-telling, and how much was newly created by the writer (or writers) will keep scholars busy for many years to come.

There is no doubt that the works are literary masterpieces, and the language, technique and style of the poetry in which they are written, as well as the narrative qualities, are still universally admired. They are also like gazeteers and a veritable who's who (or all too often who killed whom) of the ancient world. Many of the geographical, topographical and historical details have in fact been confirmed by archaeologists, historians and scientists over the last two centuries, proving at least that the author based his often incredible tales on a solid ground of facts.

Although the Mysians of northwestern Anatolia are mentioned in the Iliad ("haughty Mysians", "close-fighting Mysians", "undaunted Mysians"), the Odyssey contains the oldest known written references to the area of Mysia around Pergamon, known as Teuthrania, and the people who lived there. In Book XI, Odysseus relates the deadly doings of the Greek Neoptolemos (Νεοπτόλεμος, "New Warrior", also known as Pyrrhos), son of Achilles [4], during the Trojan War, and how he killed the handsome hero Eurypylos, son of Telephos, and his "Cetean warriors".

In blank verse:

Beneath him num’rous fell the sons of Troy

In dreadful fight, nor have I pow’r to name

Distinctly all, who by his glorious arm

Exerted in the cause of Greece, expired.

Yet will I name Eurypylus, the son

Of Telephus, an Hero whom his sword

Of life bereaved, and all around him strew’d

The plain with his Cetean warriors, won

To Ilium’s side by bribes to women giv’n.

Save noble Memnon only, I beheld

No Chief at Ilium beautiful as he."

The Odyssey of Homer, translated by William Cowper.

J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London. BOOK XI, lines 628-638.

A prose version:

"And many men he [Neoptolemus] slew in warfare dread; but I could not tell of all or name their names, even all the host he slew in succouring the Argives; but, ah, how he smote with the sword that son of Telephus, the hero Eurypylus, and many Ceteians of his company were slain around him, by reason of a woman's bribe. He truly was the comeliest man that ever I saw, next to goodly Memnon."

The Odyssey of Homer, done in English prose, by S. H. Butcher and A. Lang.

In the myths, of which there are several versions, and which may have evolved before or after the time of Homer, Telephos (Τήλεφος, far-shining) was a prince of Tegea in the Peloponnese and the son of Herakles and Auge (Αὔγη), a priestess of Athena. Telephos and Auge were forced to escape from their homeland and were given refuge by Teuthras (Τεύθρας), king of Teuthrania, in Mysia, the area in which Pergamon was to be built centuries later.

Teuthras either adopted or married Auge, offered Telephos his daughter in marriage and made him his heir. Telephos thus became, at least in the imagination of later Pergamenes, the founder of a Greek kingdom.

King Priam of Troy needed the help of Telephos' son Eurypylos (Εὐρύπυλος) to fight the invading Greeks, and persuaded Astyoche (either Eurypylos' wife or mother) to bribe him with a golden vine. Hence the reference to "a woman's bribe". The handsome hero Eurypylos led his Ceteians into battle and was killed by Neoptolemos.

The Ceteians were the people who lived around the river Ketios (today the Kestel Çayı), which runs through Bergama (see gallery 1, page 25, including map).

Pausanias adds a curious postscript to the story of Eurypylos' part in the Trojan War: Because he killed Machaon, a physician and "a son of Asklepios", his name was never mentioned in the Temple of Asklepios in Pergamon, although hymns to his father Telephos were sung there. [5]

Pergamus was also the name of the citadel of Homer's Ilium (Troy), which was destroyed by the Greeks at the end of the Trojan War. Another of Pergamon's foundation myths tells that Achilles' son Neoptolemos/Pyrros took Andromache (Ἀνδρομάχη), widow of Prince Hector of Troy, as a concubine, and became king of Epiros, in northwestern Greece. Later, Andromache accompanied her son Pergamus to Asia, where he killed King Areios of Teuthrania in single combat, took the throne and renamed the city after himself. |

|

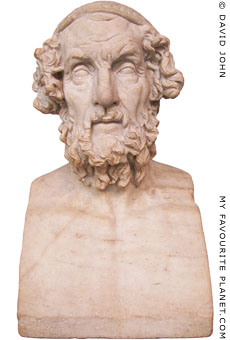

The bust of Homer in the

British Museum, London.

Inv. No, GR 1805.7-3.85

(Sculpture 1825) |

| |

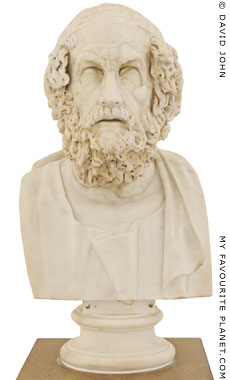

A similar bust of Homer from the

Farnese collection. Antonine copy

(138-192 AD) of a 2nd century BC

Greek original, thought to have

been made by the Rhodian School.

National Museum, Naples, Italy.

Inv. No. 6023. |

| |

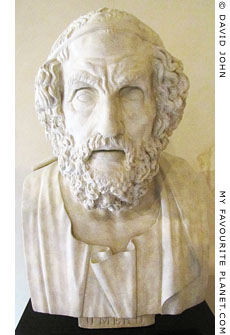

Replica of the Naples bust of Homer,

made by Gaetano Rossi in 1875. Neues Museum, Berlin. |

| |

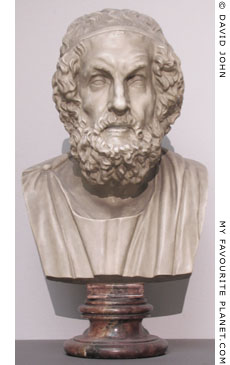

A plaster cast of a plaster cast

of a bust of Homer. This modern

copy, in the Pergamon Museum,

Berlin, was taken from the cast

in the Goethe Nationalmuseum,

Weimar, which is thought to have

belonged to Goethe.

Berlin, Abguss-Sammlung Antiker

Plastik der Freien Universität,

VII 3470. |

|