|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Sculptors R-Z |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 6 |

|

Page 6 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors R - Z |

| |

| R S

T X Z |

|

| |

Rampin Master

Also referred to as the "Master of the Rampin Horseman", his real name is unknown.

Working in Athens, mid 6th century BC

The name given to the sculptor of the "Rampin Horseman" statue, which was named after the French collector Georges Rampin (see below). A number of other surviving sculptures found in Athens, including the "Dipylon Discophoros" and the "Peplos Kore", have also been attributed to him.

The reliefs on the "Gorgon Stele", a marble grave stele found in the Kerameikos, Athens, have been associated with the Rampin Master and Phaidimos (active around 560-540 BC). National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 2687.

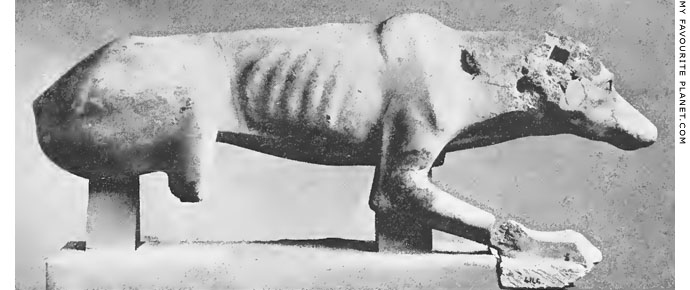

It has also been suggested that the Rampin Master sculpted a pair of lifesize marble hunting dogs, around 520 BC, which may have flanked the entrance to the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia on the Athens Acropolis. From the large number of fragments of the pair found, one has been restored and is on display in the Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. 143 (see photo below).

A marble head of a youth, probably from a statue of a horseman, found at Eleusis and dated around 560 BC, may be the work of one of his pupils (see photo below). National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 61. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

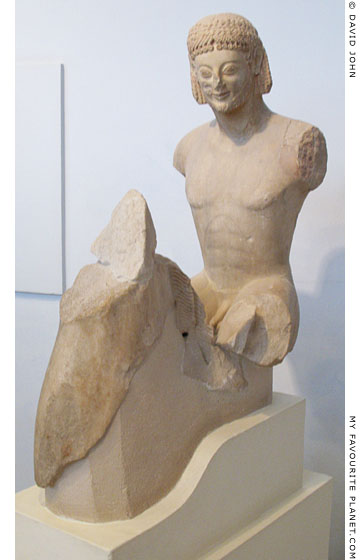

The "Rampin Horseman" or "Rampin Rider", a fragmentary marble statue of a

naked young horseman wearing a victory wreath of oak or wild celery leaves. Around 550 BC. Restored from several fragments. The head is a plaster

cast of the original now in the Louvre (Inv. No. Ma 3104). Island marble.

Height (without head) 81.5 cm. Height of head 27 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 590.

|

|

The head was found on the Athens Acropolis in 1877 and purchased by the collector Georges Rampin, secretary of the French embassy in Athens. He took it to France and later bequeathed it to the Louvre. It entered the museum in 1896.

Fragments of the rider's torso and horse were found in 1886 west of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis. The connection between the head and the torso was first made in 1936 by the British archaeologist Humfry Payne (1902-1936), director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens.

It is the earliest of around eight equestrian statue groups found on the Acropolis. Other fragments discovered led archaeologists to believe that this statue may have been one of a pair, perhaps representing the Dioskouroi or Hippias and Hipparchos, sons of the tyrant Peisistratos. It since appears that the other fragments belong to one or more other sculptures not related to this rider. His wreath may identify him as a victor in one of the games held in Greece. If the leaves are celery, he may have won in the Isthmian or Nemean Games, held near Corinth. |

|

|

| |

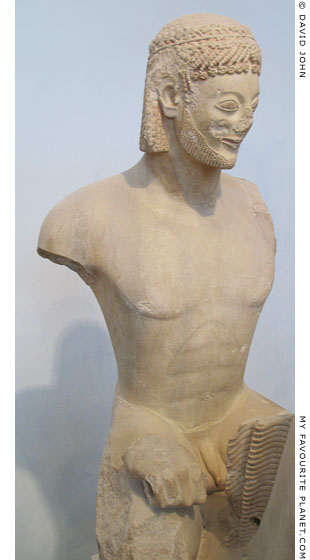

The "Dipylon Discophoros", a fragment from the top of a marble grave stele with a low

relief of the head of a discophoros (or discobolos), a youth shown profile facing right,

holding a discus above his left shoulder. Thought to be a work of the Rampin Master.

Archaic period, around 560-550 BC. Found in 1873 in the Themistoklean Wall, near

the Dipylon Gate in the Kerameikos, Athens. Pentelic marble. Height 35 cm, width 44 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 38. |

| |

|

|

|

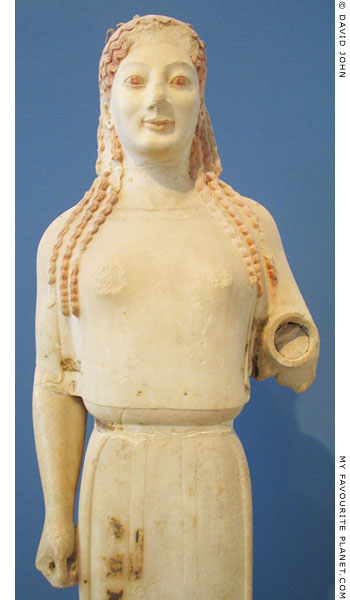

The "Peplos Kore", a marble statue of a young woman wearing a simple Doric

peplos, after which the sculpture was named, over a chiton. Her now missing

left forearm was made separately. She also wears a bronze wreath and earrings.

Surviving traces of colour include red on her hair and lips, black on her eyelashes

and brows, and green on the patterned dress. The figure may depict a goddess,

perhaps Artemis, who would have originally held a bow and arrows.

Around 530 BC. Perhaps by the Rampin Master. Restored from four fragments

found on 5th and 6th February 1886 west of the Erechtheion on the Athens

Acropolis. Parian marble. Height 120 cm (including 2.5 cm high plinth).

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 679. |

|

| |

Restored fragments of a marble statue of a hunting dog from

the Athens Acropolis. Perhaps by the Rampin Master. One of

a pair, perhaps a dedication to Artemis Brauronia, as huntress.

Around 520 BC. Found north of the Parthenon.

Island marble. Height 51 cm, length 125 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 143.

Source: Hans Schrader, Archaische Marmor-Skulpturen im Akropolis-Museum zu Athen,

Abbildung 68, page 77. Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut. A. Hölder, Wien, 1909.

At the Internet Archive. |

| |

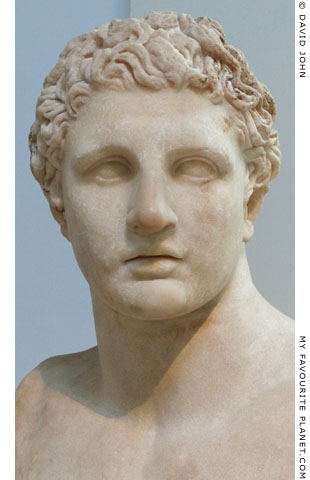

An Archaic marble head of a youth,

probably from the statue of a rider.

Perhaps by a pupil of the Rampin Master.

Around 560 BC. Found in Eleusis,

Attica. Height 18 cm. National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 61. |

|

|

|

| |

Rhoikos of Samos

Ῥοῖκος (Latin, Rhoecus)

6th century BC

Architect and sculptor from Samos.

He was the son of Philaios or Phileas. His sons Theodoros and Telecles were also sculptors in bronze.

Rhoikos and Theodoros of Samos were credited with learning the hollow-casting of bronze for large sculptures from the Egyptians (Pliny, Natural history, Book 35, chapter 43; Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, Chapter 41, section 1).

His name has been found on a fragment of a vase which he dedicated to Aphrodite at Naukratis, a Greek trading post in northern Egypt.

The temple of Apollo at Naukratis, built around 550 BC, has signs of Samian influence. It has been suggested that it was designed by Rhoikos, and that he may have learned Egyptian techniques while working there.

Herodotus (Histories, Book 3, chapter 60) wrote that Rhoikos built the Temple of Hera at Samos, probably the second temple built 580-560 BC, destroyed by fire circa 530 BC.

He made a marble statue of Night for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

His sons Theodoros and Telecles made a statue of Pythian Apollo for the Samians. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

S |

|

|

|

| |

Salpion of Athens

Σαλπίων Ἀθηναῖος

Around the reign of Emperor Augustus, early 1st century AD

He is known only from his signature, inscribed on a large marble calyx krater, with a relief depicting Hermes delivering the infant Dionysus to the Muses at Nysa. Probably 1st century AD. Height 127 cm. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6673.

One of only three surviving classical marble vases signed by an artist. The other two are:

A large krater known as the "Amphora of Sosibios", circa 50 BC. Height 67 cm. Louvre, Inv. No. Ma 422.

A Neo-Attic fountain in the shape of a rhyton (drinking horn) by Pontios of Athens, late 1st century BC. Height 112 cm. Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Inv. No. 1101. |

|

|

| |

Skopas

Σκόπας (Latin, Scopas)

Sculptor and architect, active circa 395-350 BC.

He was born on the island of Paros, which at that time was subject to Athens, but he left the island at an early age.

He was a contemporary of Bryaxis, Leochares, Praxiteles and Timotheos.

Pliny the Elder placed him in the 90th Olympiad (420 BC), along with Polykleitos, Phradmon, Myron, Pythagoras and Perellus (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

His father may have been the sculptor Aristandros of Paros (Ἀρίστανδρος δὲ Πάριος, active around 405 BC), mentioned by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 18; see quote under Polykleitos the Elder). Pausanias noted that Skopas was said to have been a prolific artist, having made sculptures in several places around the eastern Mediterranean.

"... Scopas the Parian, who made images in many places of ancient Greece, and some besides in Ionia and Caria."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 45, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

He appears to have worked mainly in marble, and his main subjects were Greek gods, as well as personifications (Love, Desire, Yearning) and mythical heroes (Achilles) and associated figures (Maenads). However, there is no record of portraits or athletes by him, and no inscribed signatures have been found. Since some of the works attributed to Skopas are thought to have been made later than the estimated period of his career (particularly the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, see below), it is thought that there were at least two sculptors of this name, and that two (conjecturally named Skopas I and Skopas II) belonged to a family of Parian artists active over several generations.

Pliny the Elder wrote that "both of the artists named Scopas" made figures of philosophers, presumably in bronze (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19), but the text of the passage may be corrupt or an interpolation. Since it is the only hint by Pliny that Skopas (or two artists of the same name) worked in bronze, some scholars have dismissed it, believing he only worked in marble. However, Pausanias also mentioned a bronze statue of Aphrodite Pandemos by Skopas (see below).

Three statue bases found on Delos are inscribed with the signature of "Aristandros, son of Skopas, of Paros" as restorer (Ἀρίστανδρος Σκόπα Πάριος ἐπεσκεύασεν). Aristandros may have restored the statues, two of which were made and signed in the late 1st century BC by Agasias, son of Menophilos, of Ephesus (Ἀγασίας Μηνοφίλου Ἐφέσιος), following the sack of Delos by Mithradates VI in 88 BC. Inscriptions:

ID 1697; ID 1710 (CIG 2285b); ID 2494.

See: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors), Nos. 287 and 288. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Pliny also mentioned marble statues of Dionysus and Athena by Skopas at Knidos (Κνίδος) in Caria:

"There are also at Cnidos [Knidos, Caria] some other statues in marble, the productions of illustrious artists: a Father Liber [Dionysus] by Bryaxis, another by Scopas, and a Minerva [Athena] by the same hand."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

Later in the same chapter, Pliny listed several other works by Skopas, many of which had been taken to Rome:

"Scopas rivals these artists [Praxiteles, Kephisodotos and others] in fame: there are by him, a Venus [Aphrodite] and a Pothos [Desire], statues which are venerated at Samothrace with the most august ceremonials.

He was also the sculptor of the Palatine Apollo; a Vesta seated, in the Gardens of Servilius [in Rome], and represented with two Bends around her, a work that has been highly praised; two similar Bends, to be seen upon the buildings of Asinius Pollio; and some figures of Canephori [figures of virgins, carrying on their heads baskets filled with objects consecrated to Athena, similar to caryatids] in the same place.

But the most highly esteemed of all his works, are those in the temple erected by Cneius Domitius, in the Flaminian Circus; a figure of Neptune [Poseidon] himself, a Thetis and Achilles, Nereids seated upon dolphins, cetaceous fishes, and sea-horses, Tritons, the train of Phorcus, whales, and numerous other sea-monsters, all by the same hand; an admirable piece of workmanship, even if it had taken a whole life to complete it.

In addition to the works by him already mentioned, and others of the existence of which we are ignorant, there is still to be seen a colossal Mars [Ares] of his, seated, in the temple erected by Brutus Callaecus, also in the Flaminian Circus; as also, a naked Venus [Aphrodite], of anterior date to that by Praxiteles, and a production that would be quite sufficient to establish the renown of any other place.

At Rome, it is true, it is quite lost sight of amid such a vast multitude of similar works of art: and then besides, the inattention to these matters that is induced by such vast numbers of duties and so many items of business, quite precludes the generality of persons from devoting their thoughts to the subject. For, in fact, the admiration that is due to this art, not only demands an abundance of leisure, but requires that profound silence should reign upon the spot.

Hence it is, that the artist is now forgotten, who executed the statue of Venus that was dedicated by the Emperor Vespasianus in his Temple of Peace, a work well worthy of the high repute of ancient times.

With reference, too, to the Dying Children of Niobe, in the Temple of the Sosian Apollo, there is an equal degree of uncertainty, whether it is the work of Scopas or of Praxiteles. So, too, as to the Father Janus, a work that was brought from Egypt and dedicated in his Temple by Augustus, it is a question by which of these two artists it was made: at the present day, however, it is quite hidden from us by the quantity of gold that covers it.

The same question, too, arises with reference to the Cupid brandishing a Thunderbolt, now to be seen in the Curia of Octavia: the only thing, in fact, that is affirmed with any degree of certainty respecting it, is, that it is a likeness of Alcibiades, who was the handsomest man of his day."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

Apart from the statues at Knidos and Samothraki, the other works mentioned (except the "Father Janus" from Egypt) were evidently looted by the Romans from Greece. The "Palatine Apollo" (Latin, Apollo Palatinus) was a marble statue of Apollo playing a lyre, placed by Augustus in the temple of Apollo he built on the Palatine Hill, Rome, in thanks for his victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The statue, also referred to as "Apollo Actius", was mentioned by Tacitus and Sextus Propertius, and appears on several Roman coins. It has been suggested that a 2nd century AD marble statue of Apoolo Musagetes (or Apollo Kitharoidos) found in 1774 at the Villa Cassius in Tivoli, near, Rome, may be a copy of this work (see note on the Kresilas page). Sale delle Muse, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 310.

The temple erected by Brutus Callaecus in the Flaminian Circus was the temple of Mars, said to have been designed by the Cypriot architect Hermodoros of Salamis.

The "Dying Children of Niobe" may have been the marble statue group known as the Dying Children of Niobe, surviving parts of which are now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. It has been suggested that they may be the works of Paionios of Mende, Praxiteles or Skopas, although, according to another theory, they may be Roman period copies, perhaps from the reign of Nero (54-68 AD).

It is doubted that the statue of "Father Janus" (if that is who the figure originally represented) was made by either Skopas or Praxiteles, since Janus was essentially an Italian deity.

Pliny (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 21) also wrote that Skopas sculpted one of the 36 decorated marble columns of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, another of the Seven Wonders of the World. However, he added that "Chersiphron was the architect who presided over the work". Chersiphron is thought to have been the architect of the first great temple at Ephesus, built in the 6th century BC, and burnt down in 356 BC. Construction the second temple began shortly after, and it was completed in the early 3rd century BC. One of the columns from the second temple, now in the British Museum, London (Inv. No. GR 1872.8-3.9; Sculpture 1206), has been dated to around 325-300 BC (see the Hermes page).

Around 350 BC Skopas worked on the sculptures of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus with Bryaxis, Leochares, and perhaps Timotheos and Praxiteles. According to Pliny the Elder, he worked on the east side of the monument. (Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 13; Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4; see Bryaxis)

In Megara, central Greece, Pausanias noted statues of personifications by Praxiteles and Skopas in the temple of Aphrodite.

"After the sanctuary of Dionysus is a temple of Aphrodite, with an ivory image of Aphrodite surnamed Praxis [Πρᾶξις, Action]. This is the oldest object in the temple. There is also Persuasion [Πειθὼ, Peitho] and another goddess, whom they name Consoler [Παρήγορον, Parigoron], works of Praxiteles. By Scopas are Love and Desire and Yearning [Ἔρως καὶ Ἵμερος καὶ Πόθος, Eros and Himeros and Pothos], if indeed their functions are as different as their names."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 43, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias also wrote that Skopas made a stone statue of Herakles for the gymnasium in Sikyon (Σικυών), northeastern Peloponnese (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 10, section 1), and the cult statue for the temple of Hekate in Argos, also of stone (Book 2, chapter 22, section 7).

Some scholars believe that a number of extant marble sculptures may be copies of the Herakles statue. See, for example, marble busts of a young beardless male wearing a wreath of poplar leaves on the Alexander the Great page. |

|

|

| |

Skopas made a bronze cult statue of Aphrodite Pandemos (Πάνδημος, Common) riding a male goat for one of the goddess' two sanctuaries of Aphrodite at Elis in the western Peloponnnese (see image, right). For the other sanctuary, of Aphrodite Ourania (Ἀφροδίτη Οὐρανία, Heavenly Aphrodite), Pheidias had made the chryselephantine cult statue of the goddess standing with one foot on a tortoise. As in a number of other cases, the travel writer made a point of not explaining the significance of the tortoise and he-goat, an omission which has been debated by modern scholars.

"The precinct of the other Aphrodite is surrounded by a wall, and within the precinct has been made a basement, upon which sits a bronze image of Aphrodite upon a bronze he-goat. It is a work of Scopas, and the Aphrodite is named Common [Pandemos]. The meaning of the tortoise and of the he-goat I leave to those who care to guess."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 25, section 1.

He made statues of Asklepios as a beardless youth and Hygieia for the temple of Asklepios at Gortys in Arcadia (Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 28, section 1), and that he was the architect of the temple of Athena Alea (Ἀθηνᾷ Ἀλέᾳ) in Tegea (Τεγέα), Arcadia, built around 345-335 BC to replace the earlier temple destroyed by fire in 395/394 BC.

"The ancient sanctuary of Athena Alea was made for the Tegeans by Aleus. Later on the Tegeans set up for the goddess a large temple, worth seeing. The sanctuary was utterly destroyed by a fire which suddenly broke out when Diophantus was archon at Athens, in the second year of the ninety-sixth Olympiad [395/394 BC], at which Eupolemus of Elis won the foot-race.

The modern temple is far superior to all other temples in the Peloponnese on many grounds, especially for its size. Its first row of pillars is Doric, and the next to it Corinthian; also, outside the temple, stand pillars of the Ionic order. I discovered that its architect was Scopas the Parian, who made images in many places of ancient Greece, and some besides in Ionia and Caria."

The relief on the front (east) pediment of the temple depicted the Kalydonian Boar hunt, and the rear pediment relief depicted Telephos fighting Achilles. Pausanias also mentioned that the cult statue of Athena was flanked by statues of Asklepios and Hygieia made by Skopas in Pentelic marble (Book 8, chapter 45, section 4 - chapter 47, section 3). See also Endoios.

The design of the temple has been more recently described as having a "traditional, rather conservative Doric temple exterior with an innovative interior layout" and "distinctly Peloponnesian" features. (Anna Vasiliki Karapanagiotou, Archaeological Museum of Tegea, pages 69-70. Athens, 2017.)

A marble head of a woman, probably Hygieia, excavated 1900-1901 at Tegea and dated around 350-325 BC, is thought to be an original work of Skopas. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3602. A number of sculptural fragments from the Tegea temple are in the Athens museum and the Tegea Archaeological Museum.

At Thebes Skopas made a stone statue of Athena which stood opposite a Hermes by Pheidias in front of the city's Elektran Gate:

"On the right of the gate is a hill sacred to Apollo. Both the hill and the god are called Ismenian, as the river Ismenus Rows by the place. First at the entrance are Athena and Hermes, stone figures and named Pronai [Of the fore-temple]. The Hermes is said to have been made by Pheidias, the Athena by Scopas."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 10, section 2.

He also made the cult statue for the temple of Artemis of Fair Fame (or Artemis of Good Fame, Ἀρτέμιδος ναός ἐστιν Εὐκλείας) in the agora of Thebes, near the Proetidian Gate.

"Near is the temple of Artemis of Fair Fame. The image was made by Scopas."

Book 9, chapter 17, section 1.

The Greek geographer Strabo mentioned a statue by Skopas of Apollo Smintheus (Ἀπόλλων Σμινθεύς, Destroyer of Mice, mentioned in Homer, Iliad, Book 1, line 38), shown with a mouse, his symbol or attribute (see the Pergamon Asclepieion), at Chrysa (Χρῦσα) in the Troad (northwest Anatolia, near modern Göztepe, Turkey). The myth of Smintheus may have begun as a founding myth of the city, but the cult spread through the surrounding area, including nearby islands such as Tenedos (today Bozcaada, Turkey), and as far afield as Pergamon, Lesbos, Chios, Rhodes and Athens.

"The temple of Apollo Smintheus is in this Chrysa, and the symbol, a mouse, which shows the etymology of the epithet Smintheus, lying under the foot of the statue. They are the workmanship of Scopas of Paros."

Strabo, Geography, Book 13, chapter 1, section 48. Translated by H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer. George Bell & Sons, London, 1903. At Perseus Digital Library.

Surviving Roman period sculpture, believed to be copies of works by Skopas include:

A restored marble head of Meleager (Inv. No. GR 1906.1-17.1, see photo, righ) and reliefs in the British Museum;

The "Meleager Pio-Clementino", around 150 AD, a marble statue of Meleager with a dog and the head of the Kalydonian Boar, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums, Inv. No. 490;

A marble statue of Meleager with a spear and a dog, Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Inv. No. Sk 215 (see photo, right);

The "Ludovisi Ares" in the Palazzo Altemps, Rome;

Several copies of Pothos (Desire), including one heavily restored as Apollo Kitharoidos in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

A Parian marble statue made by Skopas of a Maenad (or Bacchante), referred to as the "Goat Slayer" (Χιμαιροφόνος Chimairophonos), dancing in a state of religious ecstasy or madness and carrying a sacrificial kid, was mentioned by a number of authors. The "Dresden Maenad" marble statuette of a dancing maenad (see photo, below right), may be a reduced copy.

"The Bacchante is of Parian marble, but the sculptor gave life to the stone, and she springs up as if in Bacchic fury. Scopas, thy god-creating art has produced a great marvel, a Thyad, the frenzied slayer of goats."

Glaucus of Athens (Γλαῦκος Αθηναίου, Glaukos of Athens), The Greek anthology, Book 9, 774.

The Greek anthology, Volume 3 (of 5), pages 416-417. Loeb Classical Library edition. In Greek with an English translation by W. R. Paton. William Heinemann Ltd, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1917. At the Internet Archive.

The Sophist and rhetorician Kallistratos (Καλλίστρατος), writing in the 3rd or 4th century AD, had more to say about the Maenad by Skopas. However, it has been pointed out that his fourteen surviving Descriptions (Ἐκφράσεις, Ekphraseis) of statues by distinguished artists are more displays of rhetorical skill than art criticism or description.

"It is not the art of poets and writers of prose alone that is inspired when divine power from the gods falls on their tongues, nay, the hands of sculptors also, when they are seized by the gift of a more divine inspiration, give utterance to creations that are possessed and full of madness. So Scopas, moved as it were by some inspiration, imparted to the production of this statue the divine frenzy within him. Why should I not describe to you from the beginning the inspiration of this work of art?

A statue of a Bacchante, wrought from Parian marble, has been transformed into a real Bacchante. For the stone, while retaining its own nature, yet seemed to depart from the law which governs stone; what one saw was really an image, but art carried imitation over into actual reality. You might have seen that, hard though it was, it became soft to the semblance of the feminine, its vigour, however, correcting the femininity, and that, though it had no power to move, it knew how to leap in Bacchic dance and would respond to the god when he entered into its inner being. When we saw the face we stood speechless; so manifest upon it was the evidence of sense perception, though perception was not present; so clear an intimation was given of a Bacchante's divine possession stirring Bacchic frenzy though no such possession aroused it; and so strikingly there shone from it, fashioned by art in a manner not to be described, all the signs of passion which a soul goaded by madness displays.

The hair fell free to be tossed by the wind and was divided to show the glory of each strand, which thing indeed most transcended reason, seeing that, stone though the material was, it lent itself to the lightness of hair and yielded to imitation of locks of hair, and though void of the faculty of life, it nevertheless had vitality. Indeed you might say that art has brought to its aid the impulses of growing life, so unbelievable is what you see, so visible is what you do not believe. Nay, it actually showed hands in motion — for it was not waving the Bacchic thyrsus, but it carried a victim as if it were uttering the Evian cry, the token of a more poignant madness; and the figure of the kid was livid in colour, for the stone assumed the appearance of dead flesh; and though the material was one and the same it severally imitated life and death, for it made one part instinct with life and as though eager for Cithaeron, and another part brought to death by Bacchic frenzy, its keen senses withered away.

Thus Scopas fashioning creatures without life was an artificer of truth and imprinted miracles on bodies made of inanimate matter; while Demosthenes, fashioning images in words, almost made visible a form of words by mingling the medicaments of art with the creations of mind and intelligence. You will recognize at once that the image set up to be gazed at has not been deprived of its native power of movement; nay, that it at the same time is master of and by its outward configuration keeps alive its own creator."

Callistratus, Descriptions, No. 2, On the statue of a Bacchante (Εἷς τὸ βάκχης ἄγαλμα). In: Philostratus The Elder Imagines, Philostratus The Younger Imagines, Callistratus Descriptions, pages 380-385. Loeb Classical Library edition L256, in Greek with an English translation by Arthur Fairbanks. William Heinemann Ltd, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1931. At the Internet Archive.

See also: Beryl Barr-Sharrar, The Dresden Maenad and Skopas of Paros, pages 321-337, in: Dora Katsonopoulou and Andrew Stewart (editors), Paros III: Skopas of Paros and his world. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on the Archaeology of Paros and the Cyclades, Paroikia, Paros 11-14 June 2010. Athens 2013. At academia.edu. |

A Roman period coin of Elis showing

Aphrodite Pandemos riding a male goat,

rearing or flying to the right. The figure

was the subject of a statue made for

the city by Skopas.

Aphrodite is depicted nude apart from

a himation (cloak) that covers her torso

below the navel and legs. Part of it also

covers (veils) the top of her head.

Source: Pausanias's Description of

Greece, Volume 4 (of 6), translated

with a commentary by J. G. Frazer,

fig. 80, page 105. Macmillan and Co.,

London, 1898. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Marble bust of the mythical

Greek hero Meleager.

Roman period copy of a Greek original

of about 340-330 BC. Parian marble.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1906.1-17.1. |

| |

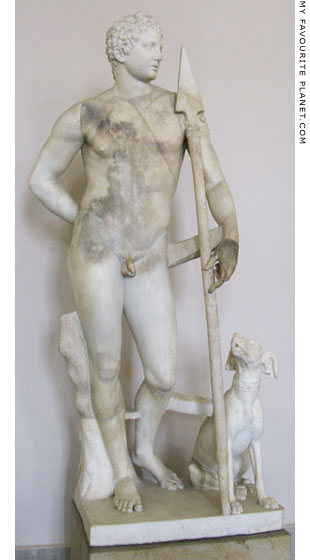

Marble statue of a nude young man,

the so-called Meleager, standing with

a spear. A dog sits by his left foot.

Roman period, 1st century AD, perhaps

a copy of a work by Skopas, 340-330 BC.

Found 1841 near Santa Marinella, Villa

of Ulpian, Civitavecchia, Italy.

Ancient restoration.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 215. |

| |

The "Dresden Maenad" marble statuette

of a dancing Maenad. Possibly based on

the marble "Goat Slayer" statue made

by Skopas of Paros.

2nd half of the 1st century BC.

White, fine-grained, translucent marble.

The arms and the legs beneath the

knees are missing. Height 45.5 cm,

width 14.0 cm, depth 14.0 cm. Original

height approximately 60-75 cm.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum,

Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 133.

Purchased in 1902 from Ludwig

Pollak, a collector in Prague,

who had acquired it in Rome. |

| |

| |

Skyllis

Σκύλλις (Latin, Scyllis)

Early 6th century. From Crete, he worked with Dipoenos at Sikyon, northeastern Peloponnese.

For further details, see Dipoenos and Skyllis. |

|

|

| |

Sokrates

Σωκράτης (Latin, Socrates)

Sokrates was identified by Pausanias and Diogenes Laertius with the Athenian philosopher of the same name, son of the sculptor Sophroniscus (Σωφρονίσκος, Sophroniskos). Diogenes Laertius also wrote that artists had previously represented the Graces (Χάριτες, Charites) naked, but that Sokrates sculptured them with drapery.

Both Pliny the Elder and Pausanias mentioned statues of the Graces by Sokrates at the Propylaia, the monumental gateway of the Athens Acropolis.

"No less esteemed, too, are the statues of the Graces, in the Propylaeum at Athens; the workmanship of Socrates the sculptor, a different person from the painter of that name, though identical with him in the opinion of some."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

"Right at the very entrance to the Acropolis are a Hermes (called Hermes of the Gateway) and figures of Graces, which tradition says were sculptured by Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, who the Pythia testified was the wisest of men, a title she refused to Anacharsis, although he desired it and came to Delphi to win it."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 22, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

"Again, at Athens, before the entrance to the Acropolis, the Graces are three in number. By their side are celebrated mysteries which must not be divulged to the many."

"Who it was who first represented the Graces naked, whether in sculpture or in painting, I could not discover. During the earlier period, certainly, sculptors and painters alike represented them draped."

"And near what is called the Pythium there is a portrait of Graces, painted by Pythagoras the Parian. Socrates too, son of Sophroniscus, made images of Graces for the Athenians, which are before the entrance to the Acropolis. All these are alike draped; but later artists, I do not know the reason, have changed the way of portraying them. Certainly today sculptors and painters represent Graces naked."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 35, sections 3, 6 and 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

Some modern scholars believe that the Graces at the Propylaia may have been made by another Sokrates, an early 5th century BC Boeotian sculptor of the "severe style".

A number of extant ancient artworks have been identified as possible copies of the Graces by Sokrates, notably a marble relief found in Rome and now in the Chiaramonti Museum of the Vatican Museums, Inv. No. 360.

Two reliefs of the Three Graces on marble plaques found in an ancient shipwreck in Piraeus harbour may also have been copied from Socrates statues. See photo below. |

|

|

| |

A marble Neo-Attic relief of the Three Graces, holding hands and moving to the left. Perhaps

copied from the statue group by Sokrates which stood at the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis.

Mid 2nd century AD. The better preserved of two almost identical plaques exhibited in the

Piraeus museum. They were among a number of other reliefs and a marble sphinx found in

an ancient shipwreck in Piraeus harbour during the winter of 1930-1931. All the sculptures,

apart from the sphinx, were made in the same Attic workshop, probably mass-produced for

export to Rome, where another relief from the same workshop has been discovered.

Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2043.

(The other relief Inv. No. 2167.) |

| |

Sostratos

Σώστρατος (Latin, Sostratus)

A number of artists named Sosastros are referred to in inscriptions and works of ancient authors. However, many of these mentions are vague, leading to confusion among modern scholars who have attempted to identify them.

There was also a gem engraver called Sostratos in the late 1st century BC. His signature is engraved on several cameos and an intaglio. He may have worked for the family of Emperor Augustus. |

|

|

| |

Sostratos, nephew of Pythagoras of Rhegion

Σώστρατος (Latin, Sostratus)

Late 5th century BC

Pliny the Elder mentioned a Sostratos said to have been the pupil and nephew of Pythagoras of Rhegion, who he wrote was working during the 90th Olympiad (420 BC).

"Sostratus, it is said, was the pupil of Pythagoras of Rhegium, and his sister's son."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Earlier in the same chapter he had named a Sostratos among artists working in the 113th Olympiad (328 BC), which, if Pliny's dates are correct, is far too late for a pupil of Pythagoras. |

|

|

| |

Sostratos of Chios

Σώστρατος Χῖος

Mid 5th century BC

Although Pausanias did not mention any of works by Sostratos, he wrote that he was the father and teacher of Pantias of Chios (Παντίας Χῖος), who made a statue of an Olympic victor at Olympia.

"Aristeus of Argos himself won a victory in the long-race, while his father Cheimon won the wrestling-match. They stand near to each other, the statue of Aristeus being by Pantias of Chios, the pupil of his father Sostratus."

Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 9, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias also mentioned that father and son were sixth and seventh in a succession of seven teachers and pupils beginning with Aristokles of Sikyon (see Aristokles of Sikyon). However, the name of Sostratos' teacher is unknown.

The Greek historian Polybius (Πολύβιος, circa 200-118 BC) wrote that Sostratus and a certain Hecatodoros made a colossal statue of Athena, which stood on the citadel of Aliphera (Ἀλίφηρα) in Arcadia.

"The citadel is on the very summit of this hill, adorned with a colossal statue of Athene, of extraordinary size and beauty. The origin and purpose of this statue, and at whose expense it was set up, are doubtful questions even among the natives; for it has never been clearly discovered why or by whom it was dedicated: yet it is universally allowed that its skilful workmanship classes it among the most splendid and artistic productions of Hecatodorus and Sostratus."

Polybius, Histories, book 4, chapter 78. At Perseus Digital Library.

Hecatodoros is otherwise unknown, but Pausanias said the statue was made by Hypatodoros (Ὑπατόδωρος) and that it was made of bronze. He also informs us (chapter 26, section 5) that the city was abandoned around 370 BC when its inhabitants moved to Megalopolis (see Demeter and Persephone part 2). It is thus presumed that the statue was made before this date. It may also explain why by the second century BC nobody then in the area knew about the work's history.

"The image of Athena is made of bronze, the work of Hypatodorus, worth seeing for its size and workmanship."

Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 26, section 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

Hypatodorus and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτον) are also said to have made a large statue group dedicated at Delphi by the people of Argos.

"Near the horse are also other votive offerings of the Argives, likenesses of the captains of those who with Polyneices made war on Thebes: Adrastus, the son of Talaus, Tydeus, son of Oeneus, the descendants of Proetus, namely, Capaneus, son of Hipponous, and Eteoclus, son of Iphis, Polyneices, and Hippomedon, son of the sister of Adrastus. Near is represented the chariot of Amphiaraus, and in it stands Baton, a relative of Amphiaraus who served as his charioteer. The last of them is Alitherses.

These are works of Hypatodorus and Aristogeiton, who made them, as the Argives themselves say, from the spoils of the victory which they and their Athenian allies won over the Lacedaemonians at Oenoe in Argive territory."

Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 10, sections 3-4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19) included an artist named Hypatodorus in a list of sculptors working in bronze in the 102nd Olympiad (372 BC) which also included Polycles, Cephisodotus and Leochares.

The signature of Hypatodorus and Aristogeiton of Thebes was found in Delphi on a fragment of a base for a statue of a sports victor from Orchomenos, probably at the Pythian Games. Dated to around the early 4th century BC.

See: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors), No. 101, pages 80-81. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Sostratos of Knidos

Σώστρατος ὁ Κνίδος (or Σώστρατος Κνίδιος), son of Dexiphanes (Δεξιφάνες); Latin, Sostratus Cnidius

Architect. Late 4th - early 3rd century BC. From Knidos (Κνίδος), Caria (today, Yazıköy, Muğla Province, Turkey)

He is said to have been the designer of the Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria in Egypt, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and a new type of monumental promenade at Knidos. He is also thought to have been an engineer, and to have acted as an ambassador for Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II, the first Hellenistic rulers of Egypt.

A larger article about Sostratos of Knidos is currently in preparation. |

|

|

| |

Sostratos son of Euphranor

Σώστρατος Ἐυφράνωρος (Latin, Sostratus)

4th century BC

The son of the sculptor and painter Euphranor of Corinth

A number of statue bases found in Athens and Piraeus are signed by his son Sostratos son of Euphranor (Σώστρατος Ἐυφράνωρος ἐποίησεν). Pliny the Elder mentioned a sculptor named Sostratos as a contemporary of other sculptors working in bronze, including Lysipppos, in the 113th Olympiad (328-325 BC).

"... in the hundred and thirteenth, Lysippus, who was the contemporary of Alexander the Great, his brother Lysistratus, Sthennis, Euphron, Eucles, Sostratus, Ion, and Silanion, who was remarkable for having acquired great celebrity without any instructor: Zeuxis was his pupil."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

This article is currently being rewritten and expanded. |

|

|

| |

Stasikrates (or Deinokrates)

Στασικράτης

Sculptor, architect and city planner

4th - 3rd century BC

Sculptor, architect and city planner

From Macedonia or Rhodes

Thought to be the same artist mentioned but named differently by ancient authors:

Cheirokrates; Deinokrates or Dinocrates, Deinokrates of Rhodes; Dinochares; Diocles of Rhegium ; Stasikrates or Stasicrates; Timochares.

This article is currently being rewritten.

A longer article about this artist will be appearing on a separate page. |

|

|

| |

Sthennis

Σθέννις

Mid - late 4th century BC

Pausanias named him "Sthennis of Olynthos". He is thought to have moved to Athens as a refugee at the time of the destruction of Olynthos, Halkidiki by Philip II of Macedonia in 348 BC (see History of Stageira part 6).

Pliny the Elder placed the height of his career during the 113th Olmpiad (328-325 BC), as a contemporary of Lysippos, Lysistratos, Silanion and other sculptors in bronze (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

Pausanias recorded two statues by "Sthennis of Olynthos" at Olympia depicting Pyttalus and Choerilus, victors from Elis in the boys' boxing contest (Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 16, section 8 and chapter 17, section 5).

"Sthennis made the statues of Ceres, Jupiter, and Minerva, which are now in the Temple of Concord [in Rome]; also figures of matrons weeping, adoring, and offering sacrifice."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19.

He made a statue of Autolycus, the founder of Sinope. When Lucullus captured the city he took the statue to Rome.

He is also mentioned Plutarch, Strabo and Appian.

His signature has been found on a base for a group of five statues in Athens, made around 330 BC. Two statues are signed by Sthennis and two by Leochares. |

|

|

| |

Strongylion

Στρογγυλίων

Athens, Late 5th century BC

Pausanias described Strongylion as "an excellent artist of oxen and horses", and wrote that he made three statues of a group of the nine Muses for the Grove of the Muses on Mount Helikon, Boeotia. Three were made by Kephisodotos the Elder and three by Olympiosthenes (Ὀλυμπιοσθένης).

"The first images of the Muses are of them all, from the hand of Cephisodotus, while a little farther on are three, also from the hand of Cephisodotus, and three more by Strongylion, an excellent artist of oxen and horses. The remaining three were made by Olympiosthenes."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 30, section 1.

Pausanias also mentioned a statue of Artemis Saviour (Ἀρτέμιδος Σωτείρα) by Strongylion at Megara, among a later statue group of the twelve Olympian gods said to have been made by Praxiteles. He explained that the statue of Artemis had been dedicated in thanks to the goddess for her help in defeating a detachment of Persian archers from the army of Xerxes' general Mardonius (479 BC).

"For this reason they had an image made of Artemis Saviour. Here are also images of the gods named the Twelve, said to be the work of Praxiteles. But the image of Artemis herself was made by Strongylion."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 40, section 3.

He made a bronze statue of the Wooden Horse of Troy for the Athens Acropolis, mentioned by Aristophanes in the Birds (v. 1128); a scholiast names Chairedemos as the dedicator. The inscribed base of the statue, dated to around 414 BC, was found near the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia on the Acropolis in 1840. The inscription reads:

Χαιρέδημος Εὐαγγέλου ἐκ Κοίλης ἀνέθηκεν Στρογγυλίων ἐποίησεν

Since no ethnic is mentioned, he is thought to have been an Athenian, although neither Pliny nor Pauanias said where he came from.

This is likely to have been the bronze statue of the Trojan Horse mentioned by Pausanias as standing near sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia.

"There is the horse called Wooden set up in bronze. That the work of Epeius was a contrivance to make a breach in the Trojan wall is known to everybody who does not attribute utter silliness to the Phrygians. But legend says of that horse that it contained the most valiant of the Greeks, and the design of the bronze figure fits in well with this story. Menestheus and Teucer are peeping out of it, and so are the sons of Theseus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 8.

Pliny the Elder wrote that Strongylion made a bronze statue of an Amazon later owned by Emperor Nero, and a bronze figure of a youth admired by Brutus.

"Strongylion made a figure of an Amazon, which, from the beauty of the legs, was known as the 'Eucnemos' [beautiful-legged], and which Nero used to have carried about with him in his travels. Strongylion was the artist, also, of a youthful figure, which was so much admired by Brutus of Philippi, that it received from him its surname [Misoromaeus, Roman-hater]."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. |

|

|

| |

|

|

Styppax

Στύππαξ (Styppax of Cyprus; Latin, Styppax Cyprius;

also referred to as Stypax)

Mid 5th century BC

From Cyprus, working in Athens

Styppax is known only from two mentions by Pliny the Elder of a bronze statue, apparently famous in his time, known as the "Entrail Roaster" (σπλαγχνόπτης, splanchnoptes, man cooking intestines), depicting a favourite slave of the Athenian general and statesman Pericles.

"Stypax of Cyprus acquired his celebrity by a single work, the statue of the Splanchnoptes, which represents a slave of the Olympian Pericles, roasting entrails and kindling the fire with his breath."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19, "An account of the most celebrated works in brass, and the artists, 366 in number". At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny also related an anecdote in which this slave was badly injured by falling from the roof of a temple on the Athens Acropolis, probably the Parthenon, during its construction. Athena appeared to Pericles in a dream and gave him a presciption for a herbal remedy which cured the slave (Natural History, Book 22, chapter 20).

Plutarch reported a similar anecdote concerning an unnamed workman who fell from the roof of the Propylaia, but mentioned a bronze statue of Athena Hygieia set up by Pericles (see Pyhrros).

On the basis of these anecdotes and another mention by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 4) of statues of Hygieia and Athena Hygieia near the entrance to the Acropolis, it is thought that the "Entrail Roaster" may have stood at the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia next to the Propylaia (see Athens Acropolis page 10), among "less distinguished portraits" which he disdained to mention. However, since Pliny referred to the statue as being famous, it may have been removed to Italy before Pausanias' visit to Athens.

A fragmentary marble statue found in the area of the Olympieon (the Temple of Olympian Zeus), Athens, is thought to be a Roman period copy of the Splanchnoptes by Styppax (see photo, right). National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 248. Described by the museum labelling as an "eclectic work".

The subject of the "Entrail Roaster" was also painted on Greek pottery, including an Attic red-figure stamnos attributed to Polygnotos, 450-430 BC, in the British Museum. |

|

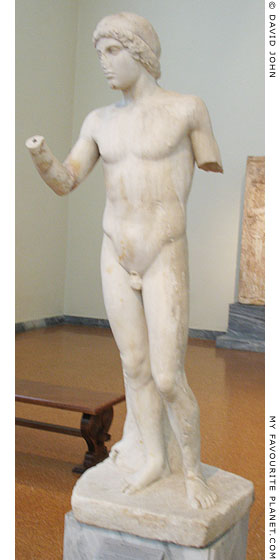

A marble statue of a youth, found in

the area of the Olympieon, Athens.

Thought to have been inspired by

the Splanchnoptes by Styppax.

Roman period, 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 248. |

|

| |

| Sculptors |

T |

|

|

|

| |

Tauriskos of Tralles

Ταυρίσκος ὁ Τραλλιανός (Latin, Tauriscus)

From Tralles (Τράλλεις), Caria (today Aydın, Turkey), 2nd century BC.

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4) twice mentions the name Tauriscus among sculptors whose works were displayed in the memorial buildings of Asinius Pollio (75 BC - 4 AD) in Rome: first was "Tauriscus ... a native of Tralles" who made Hermerotes; the second was apparently the brother of Apollonius, with whom he made a statue group of "Zethus and Amphion, with Dirce, the Bull, and the halter, all sculptured from a single block of marble", which been taken to Rome from Rhodes. It is not clear whether Pliny was referring to the same person twice or two separate artists named Tauriscus. Some scholars, believing them to be the same, refer to the brothers as Apollonius and Tauriscus of Tralles.

For further details see Apollonios and Tauriskos (of Tralles). |

|

|

| |

Theodoros of Samos

Θεόδωρος ὁ Σάμιος

6th century BC

From Samos

Son of Rhoikos of Samos, and brother of the sculptor Telecles.

Along with his father Rhoikos of Samos, Theodoros was credited with learning from the Egyptians the hollow-casting of bronze for large sculptures.

Theodoros and his brother Telecles made a statue of Pythian Apollo for the Samians. |

|

|

| |

Theokosmos of Megara

Θεόκοσμος

Mid - late 5th century BC

From Megara (Μέγαρα), central Greece

A contemporary of Pheidias, he was the father of the sculptor Kallikles of Megara, and perhaps the grandfather of the sculptor Apelleas.

Pausanias wrote that Theokosmos was helped by Pheidias to make a chryselephantine statue of Zeus for the Olympieion (sanctuary of Olympian Zeus) at Megara. Work on the statue was interrupted by the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) and it was never completed.

"After this when you have entered the precinct of Zeus called the Olympieum you see a noteworthy temple. But the image of Zeus was not finished, for the work was interrupted by the war of the Peloponnesians against the Athenians, in which the Athenians every year ravaged the land of the Megarians with a fleet and an army, damaging public revenues and bringing private families to dire distress.

The face of the image of Zeus is of ivory and gold, the other parts are of clay and gypsum. The artist is said to have been Theocosmus, a native, helped by Pheidias. Above the head of Zeus are the Seasons and Fates [Ὧραι καὶ Μοῖραι], and all may see that he is the only god obeyed by Destiny, and that he apportions the seasons as is due. Behind the temple lie half-worked pieces of wood, which Theocosmus intended to overlay with ivory and gold in order a complete the image of Zeus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 40, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

At Delphi Pausanias mentioned a statue by Theokosmos among offerings by Sparta, of which the sculptor had apparently been granted citizenship. A group of statues commemorated the victory of the Spartan navarch (admiral) Lysander (Λύσανδρος, died 395 BC) over the Athenian fleet at the naval Battle of Aigospotami (Αἰγὸς Ποταμοί) in the Hellespont in 405 BC.

"Opposite these are offerings of the Lacedaemonians from spoils of the Athenians: the Dioscuri, Zeus, Apollo, Artemis, and beside these Poseidon, Lysander, son of Aristocritus, represented as being crowned by Poseidon, Agias, soothsayer to Lysander on the occasion of his victory, and Hermon, who steered his flag-ship.

This statue of Hermon (Ἕρμων) was not unnaturally made by Theocosmus of Megara, who had been enrolled as a citizen of that city. The Dioscuri were made by Antiphanes of Argos; the soothsayer by Pison, from Calaureia, in the territory of Troezen; the Artemis, Poseidon and also Lysander by Dameas; the Apollo and Zeus by Athenodorus. The last two artists were Arcadians from Cleitor."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 9, sections 7-8. At Perseus Digital Library.

The bronze statues set up by Lysander from the spoils of Aigospotami were also mentioned by Plutarch in his biography of the admiral (Plutarch, Lysander, chapter 18, at LacusCurtius). The offering is known by modern historians as the "Ex voto of the Lacaedemonians" or "Monument of the Navarchs (or Admirals)". Parts of the base of a bronze statue, believed to be that of Lysander, has been found at Delphi, inscribed with a dedicatory epigram in elegiac couplets, apparently recut around 350–300 BC:

εἰκόνα ἑὰν ἀνέθηκεν [ἐπ’] ἔργωι τῶιδε ὅτε νικῶν

ναυσὶ θοαῖς πέρσεν Κε[κ]ροπιδᾶν δύναμιν

Λύσανδρος, Λακεδαίμονα ἀπόρθητον στεφανώσα[ς]

Ἑλλάδος ἀκρόπολ[ιν, κ]αλλίχορομ πατρίδα.

ἐχσάμο ἀμφιρύτ[ου] τεῦξε ἐλεγεῖον⋮ Ἴων.

Lysander set up his image here on this monument when as conqueror

with swift ships he destroyed the Cecropidan force,

having crowned Lacedaemon undefeated,

the acropolis of Greece, homeland of beautiful dancing-grounds.

Ion, from sea-girt Samos, created this poem.

Inscription Fouilles de Delphes, FD III, 1:50.

Given that Theokosmos was at work in Megara before the start of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC, and completed the statue of Hermon some time after 405 BC, at the end of the war, his career spanned at least three decades, and he appears to have been working at the same time as his son Kallikles and grandson Apelleas. |

|

|

| |

Thrasymedes of Paros

Θρασυμήδης ο Παριανός

Early 4th century BC

From Paros, worked at Epidaurus

Son of Arignotos of Paros (Ἀριγνώτος Πάριο)

Pausanias wrote that Thrasymedes made the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) cult statue of Asklepios enthroned for the temple of Asklepios at the Asklepieion of Epidauros (Επίδαυρος; today Epidavros) in the northeastern Peloponnese. This statue is thought to be the enthroned figure of Asklepios shown on ancient coins of Epidauros, as well as one of two marble reliefs found near the temple (see photo on the Asklepios page).

"The image of Asclepius is, in size, half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold. An inscription tells us that the artist was Thrasymedes, a Parian, son of Arignotus. The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of the serpent; there is also a figure of a dog lying by his side. On the seat are wrought in relief the exploits of Argive heroes, that of Bellerophontes against the Chimaera, and Perseus, who has cut off the head of Medusa."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, section 2.

Elsewhere, when discussing the colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus in Olympia by Pheidias, Pausanias wrote that a pool of olive oil stood around it to prevent the ivory being damaged by the atmosphere. He added that water was used in the same way to protect the same sculptor's Athena Parthenos statue in Athens, but that this was not necessary for the Asklepios statue at Epidauros since it stood above a cistern. Modern scholars have commented that these measures may have been taken more to preserve the wooden frames of the statues than the ivory.

"All the floor in front of the image [the statue of Zeus in Olympia] is paved, not with white, but with black tiles. In a circle round the black stone runs a raised rim of Parian marble, to keep in the olive oil that is poured out. For olive oil is beneficial to the image at Olympia, and it is olive oil that keeps the ivory from being harmed by the marshiness of the Altis. On the Athenian Acropolis the ivory of the image they call the Maiden [Athena Parthenos] is benefitted, not by olive oil, but by water. For the Acropolis, owing to its great height, is over-dry, so that the image, being made of ivory, needs water or dampness.

When I asked at Epidaurus why they pour neither water nor olive oil on the image of Asclepius, the attendants at the sanctuary informed me that both the image of the god and the throne were built over a cistern."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 11, sections 10-11.

An inscription, found in 1885 east of the temple in the Asklepieion of Epidauros (see Timotheos below), details the construction costs of the Doric temple, and names some of the people who did the work. A Thrasymedes undertook to execute the roof, wood covered with marble tiles, and the doors, made of ivory at a cost of 3070 drachms. Financial accounts for the temple: Inscription IG IV²,1 102 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

An inscribed statue base with the signature of Thrasymedes was found at Epidauros in 1894.

Χαρμαντίδας [⋮ Πυ]λ̣άδα

Ἐπιδαύριος ⋮ Ἀπ̣[ό]λλωνι,

Ἀσσκλαπιῶι ⋮ ἀνέθηκεν.

Θρασυμήδης ⋮ ἐποίησεν.

Inscription IG IV²,1 198.

Athenagoras, writing in the mid 2nd century AD, claimed that the statue of Asklepios at Epidauros was a work of Pheidias (Leg. pro Christ. 14, p. 61: ed. Dechair), a statement which appears to have no authority.

Some scholars, attempting to reconcile the testimonies of Pausanias and Athenagoras, thought that Thrasymedes must have been a pupil of Pheidias, and modelled the statue of Asklepios on Pheidias' statue of Zeus at Olympia. However, the temple and the statue are now known to be from the 4th century BC.

See: Harold N. Fowler, The statue of Asklepios at Epidauros. The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Volume 3, No. 1/2 (June 1887), pages 32-37. At jstor. |

|

|

| |

Timarchos

Τίμαρχος

Late 4th - early 3rd century BC (around 345-290 BC)

Athens

Thought to be the brother of Kephisodotos the Younger, son of Praxiteles and grandson of Kephisodotos the Elder.

A sculptor named Timarchus is mentioned by Pliny the Elder, who placed him at the time of the 121st Olympiad with Cephisodotus (Kephisodotos the Younger), Eutychides, Euthycrates, Laippus and Pyromachus (Pliny, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

Pausanias does not mention Timarchos by name, but noted works by "sons of Praxiteles": a statue of Enyo (Ἐνυο, Warlike) in the sanctuary of Ares in the Athens Agora, and an altar that stood next to a bronze statue of Dionysus in the agora of Thebes, Boeotia.

He also mentioned a statue of Menander (Athenian playwright, circa 342-290 BC) at the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens, although he did not say who made it. A pedestal, dated 291/290 BC, discovered at the theatre in 1862, is inscribed with the name "Menandros", below which are the signatures of Kephisodotos and Timarchos.

This is thought have been the base of the statue seen by Pausanias. From this and other epigraphical evidence it is also believed that the two sculptors were brothers and the sons of Praxiteles.

See Kephisodotos the Younger for further details. |

|

|

| |

Timotheos

Τιμόθεος (Latin, Timotheus)

4th century BC

Born in Epidauros, died there circa 340 BC

Pliny the Elder included an artist named "Timotheus" in a list of those who had made "statues of athletes, armed men, hunters, and sacrificers" (Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19).

He may the same person the author elsewhere mentioned as a rival and contemporary of the sculptors Skopas, Bryaxis and Leochares, and who worked with them to make the sculptural decoration for the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (around 350 BC). Pliny said Timotheos worked on the south side of the monument (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4; see the entire quote under Bryaxis). In the same chapter he mentioned a statue of Artemis by Timotheos, which had been taken to Rome.

"There is at Rome, by Timotheus, a Diana [Artemis], in the Temple of Apollo in the Palatium, the head of which has been replaced by Avianius Evander."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. |

|

|

| |

Vitruvius was not so certain that Timotheos worked on the Mausoleum, but believed that Leochares, Bryaxis and Scopas did, and added Praxiteles to the list.

"For men whose artistic talents are believed to have won them the highest renown for all time, and laurels forever green, devised and executed works of supreme excellence in this building. The decoration and perfection of the different facades were undertaken by different artists in emulation with each other: Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas, Praxiteles, and, as some think, Timotheus. And the distinguished excellence of their art made that building famous among the seven wonders of the world."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 13. At Perseus Digital Library.

According to Vitruvius, either Leochares or Timotheos made a colossal acrolithic (wood and stone) statue of the war god Ares for the temple of Ares at Halicarnassus:

"At the top of the hill, in the centre, is the fane of Mars, containing a colossal acrolithic statue by the famous hand of Leochares. That is, some think that this statue is by Leochares, others by Timotheus."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 2, chapter 8, section 11. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias made only one mention of a sculptor named Timotheos, as the maker of a statue in the sanctuary of the hero Hippolytos (Ἱππόλυτος), the son of Theseus, at Troezen in the northwestern Peloponnese.

"The image of Asclepius was made by Timotheus, but the Troezenians say that it is not Asclepius, but a likeness of Hippolytus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, Chapter 32, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

A long inscription, found in 1885 to the east of the temple in the Asklepieion of Epidauros, details the costs of the temple's construction (late 5th - early 4th century BC). A Timotheus is named as the maker of models after which various artists executed the figures in Pentelic marble on the pediments (gables) and those that stood on the roof (aktroteria). The sculptures of the western pediment are thought to have depicted a battle with the Amazons (Amazonomachy), and those on the eastern pediment a battle with the Centaurs Centaurmachy). The inscription also states that the temple building was superintended by the architect Theodotes, who received 353 drachms a year. A Thrasymedes (the Thrasymedes of Paros who made the temple's cult statue?) undertook to execute the roof and doors. Financial accounts for the temple: Inscription IG IV²,1 102 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Timotheos is credited with making a statue of Leda and Zeus as a swan, thought to be the model for several Roman copies (see photo, right).

A marble relief of an Amazonomachy found in Athens and dated to the mid 4th century BC, has been attributed to the school of Bryaxis or Timotheos (see photo and further details under Bryaxis). |

|

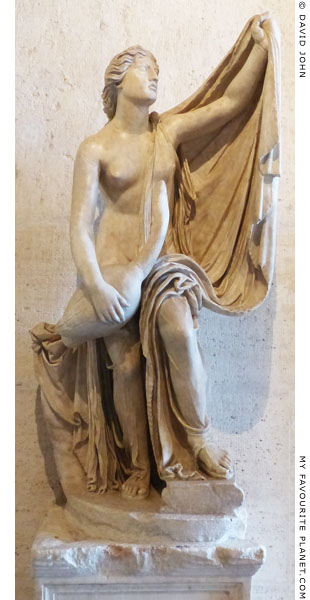

A marble statue of Leda and Zeus

disguised as a swan.

Roman copy, 2nd century AD, after a

Greek original attributed to Timotheos,

around 360 BC. Height 132 cm.

Galleria, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline

Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 302.

From the Albani Collection. Purchased

by Pope Clement XIV from the heirs of

Cardinal Alessandro Albani (1692-1779). |

|

| |

| Sculptors |

X |

|

|

|

| |

Xenophon of Athens

Ξενοφῶν Ἀθηναῖος

4th century BC

Pausanias made two mentions of an Athenian sculptor or sculptors named Xenophon, both connected with references to Kephisodotos, probably the Athenian Kephisodotos the Elder, thought to be the father or uncle of Praxiteles.

In the agora of Megalopolis, Arcadia, Pausanias noted a statue group of Pentelic marble (i.e. marble from Athens) by Athenian sculptors Kephisodotos and Xenophon in the sanctuary of Zeus the Saviour (Διός Σωτῆρος, Dios Soteiros). The city was founded about 370 BC (see Demeter and Persephone part 2), so the statues must have been made at some time after.

"Here then is the Chamber, but the portico called 'Aristander's' in the market-place was built, they say, by Aristander, one of their townsfolk. Quite near to this portico, on the east, is a sanctuary of Zeus, surnamed Saviour. It is adorned with pillars round it. Zeus is seated on a throne, and by his side stand Megalopolis on the right and an image of Artemis Saviour on the left. These are of Pentelic marble and were made by the Athenians Cephisodotus and Xenophon."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 30, section 10. |

|

|

| |

At Thebes he saw a statue of Tyche (Τύχη; Latin, Fortuna) holding the infant Ploutos (Πλοῦτον, Wealth), in the sanctuary of Tyche, partly made by "Xenophon the Athenian" (Ξενοφῶν Ἀθηναῖος). He compared the subject of the work with the statue by Kephisodotos of the goddess Eirene (Εἰρήνη, Peace) holding the infant Ploutos, thought to be the work he elsewhere wrote stood in the Athens Agora (see Kephisodotos the Elder).

"After the sanctuary of Ammon at Thebes comes what is called the bird-observatory of Teiresias, and near it is a sanctuary of Fortune, who carries the child Wealth.

According to the Thebans, the hands and face of the image were made by Xenophon the Athenian, the rest of it by Callistonicus [Καλλιστόνικος], a native. It was a clever idea of these artists to place Wealth in the arms of Fortune, and so to suggest that she is his mother or nurse. Equally clever was the conception of Cephisodotus, who made the image of Peace for the Athenians with Wealth."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 16, section 2.

Unfortunately, neither work is described. However, Since Xenophon is said to have made only the hands and face, the statue group may have been acrolithic (wood and stone), with only the exposed areas of flesh such as heads, arms, hands and feet, in marble, and the rest of the sculpture made of wood, perhaps covered or decorated with other materials. Had the work been chryselephantine (gold and ivory), a much more expensive technique used relatively rarely, Pausanias may well have mentioned the fact (see, for example, Thrasymedes of Paros above). If it was made entirely of marble or bronze, Xenophon may have been considered the better modeller of anatomical details, leaving the presumably less gifted or younger local artist Kallistonikos to complete the clothed parts of the figures. |

|

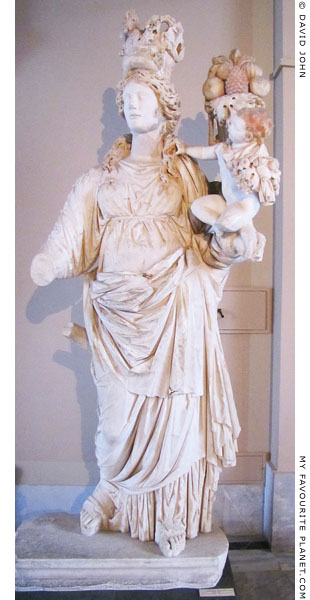

A marble statue of Tyche holding the infant

Ploutos and a cornucopia in her left hand.

Traces of colour have survived, particularly

on Plouton's hair and the fruit in the horn.

Pausanias wrote that Bupalus (6th century

BC) was the first to depict Tyche holding

the cornucopia (see Archemos of Chios).

2nd century AD, Roman period.

From Prusias Ad Hypium, Bithynia

(Üskübü, Bolu, Turkey).

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 4410. |

|

| |

| Sculptors |

Z |

|

|

|

| |

Zenas

Ζηνας

"Zenas son of Alexandros" and "Zenas son of Zenas" each signed the base of one of two marble portrait busts now in the Capitoline Museums, Rome (see photos below).

They were probably father and son, from Aphrodisias (Ἀφροδισιάς), Caria, western Anatolia (today near the modern village of Geyre, Aydın Province, Turkey), and are thought to have worked in Rome during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD). |

|

|

| |

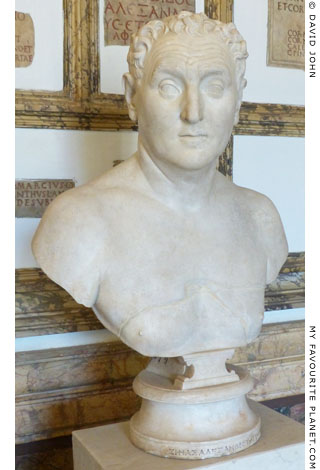

Marble male portrait bust signed on

the base by Zenas son of Alexandros.

ΖΗΝΑΣ ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ - ΕΠΟΙΕΙ

Inscription IG XIV 1241.

Reign of Emperor Hadrian, 117-138 AD.

Luna (Carrara) marble. Height 71 cm.

Sala del Fauno (Hall of the Faun),

Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums,

Rome. Inv. No. MC 579.

From the Albani Collection. |

|

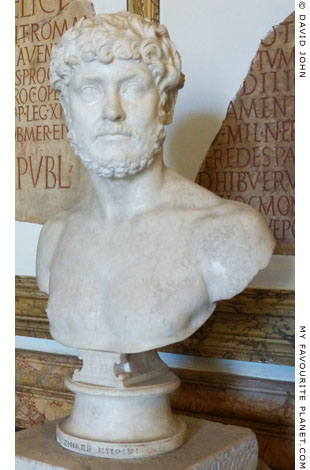

Marble male portrait bust signed on

the base by Zenas son of Zenas.

ΖΗΝΑΣ Β ΕΠΟΙΕΙ

Inscription IG XIV 1242.

Reign of Emperor Hadrian, 117-138 AD.

Luna marble. Height 69 cm.

Sala del Fauno (Hall of the Faun),

Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums,

Rome. Inv. No. MC 459.

From the Albani Collection. |

|

| |

Zenodoros

Ζηνόδωρος (Latin, Zenodorus)

1st century AD, place of origin unknown.

Zenodoros was mentioned only by Pliny the Elder as a sculptor of colossal bronze statues and an engraver of silver vessels. He made the colossal bronze statue in Rome known as the "Colossus of Nero".

See also:

the Colossus of Rhodes by Chares of Lindos |

|

This section is currently being rewritten.

A longer article about Zenodoros

will be appearing on a separate page. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|