|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Pergamon > gallery 2 |

| Pergamon gallery 2 |

Pergamon art |

|

|

10 of 26 |

|

|

|

| |

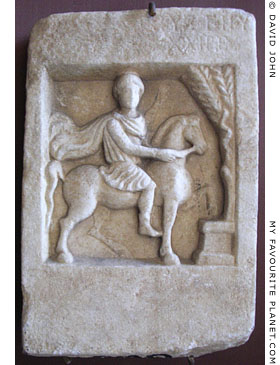

Hellenistic hero relief from Pergamon. Marble, 3rd-2nd century BC.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 362 T. |

| |

The rectangular marble stele, carved in high relief, is thought to be a funerary stele for a heroized man. [1] The finally carved sculpture is damaged and several details, including the head of the deceased, are missing. Originally, the stele was probably surrounded by a frame and carried an inscription.

The athletically built hero, standing in the centre, is the largest figure in the image. He is nude apart from a cloak draped over his left shoulder [2]. In his left arm he held a sword (now missing) and in his right hand is a phiale (φιάλη, known in Latin as a patera), a shallow bowl used for pouring libations.

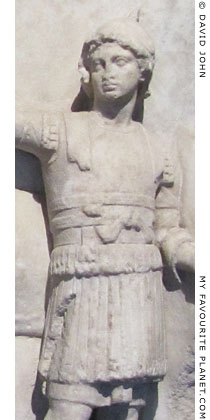

To his left a warrior, perhaps a servant or groom, in full armour and with a shield, holds his horse. The figure's armour has been compared to the type shown in the reliefs of the Athena Sanctuary on the Pergamon Acropolis (see gallery 2, page 20 and page 21).

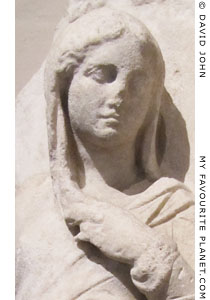

To his right (left side of the relief) stands a young woman draped in a himation (cloak), with her head covered and bowed forward, her right hand resting on a short pillar.

All three figures stand with their weight on one leg while the other leg is bent at the knee, with the foot slightly behind the torso and the heel raised, as if they are stepping forward. This device was first used by sculptors in ancient Egypt and then in Greece from the Archaic period to make figures in otherwise static poses appear more dynamic.

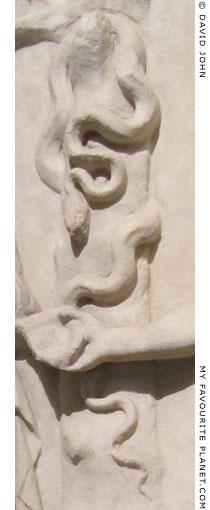

Between the hero and the woman sits a hunting dog (head missing) which was perhaps looking up to its master. The hero appears to be pouring an offering from the phiale onto a round altar behind the dog. Behind the altar is a tree around which a snake is entwined.

Depictions of heroes as mythical or legendary ancestors, founders of communities, helpers, demi-gods and daemons, were widespread in ancient cultures. In Greece cults for heroes, such as Herakles and the Dioskouri, are known to have existed since at least the Archaic period. From the late Classical and Hellenistic periods rulers, such as Alexander the Great and the Attalid kings of Pergamon, were also the subject of official hero cults and depicted as heroes in art.

Lesser mortals were also revered as local, unofficial heroes, within the context of a family, tribe or community. From the 5th century BC, deceased men and women were depicted as heroes and heroines by some Greek communities, particularly in western Anatolia (where the Lycians also built hero tombs), and by the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC the practice had become common throughout the Greek world.

The heroized dead came to be depicted on sarcophagi, grave steles and paintings generally in one of two types of scenes: as a reveller in a banqueting scene (known as "Totenmahl", German for meal of the dead); or as a rider, hunter or warrior. Each type of scene usually contained certain iconographic and compositional elements which became conventional, although their significance is uncertain to modern scholars and a subject of lively debate. In many cities and areas local iconographical elements were included on such monuments, which makes interpretations more difficult.

It may seem that in this relief, for example, the hero is preparing for his departure from his widow by making a sacrifice to a domestic deity for the protection of his family and home, before riding off to battle, his destiny, his heroic death. Such convential narratives of farewell are known from earlier grave images common in the Classical period (e.g. Attic grave steles from Kerameikos in Athens). However, many scholars believe that the "hero" dimension of these later scenes added meanings in terms of spiritual symbolism which also reflected or projected the earthly status of the deceased, and by extension that of his family.

What, for example, is the significance of the snake in tree, found on many such hero reliefs? Some believe that the snake represents the dead man's soul, while others have speculated that it is an attribute of a god such as Asklepios or a chthonic deity or deities, or a status symbol. The tree has been taken by some scholars to be the tree of life, a symbol of rebirth or nature, or a sacred tree.

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods the tradition of depicting a hero as a rider, hunter or warrior became increasingly popular in Thrace, where over 3500 ancient Thracian rider monuments have so far been discovered at more than 350 locations. [3]

See also:

The Hephaistion hero relief from Pella, Macedonia, Greece, showing the heroized companion of Alexander the Great:

Pella gallery page 17

A Roman period hero relief depicting the heroized Polydeukes, an adopted son of the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus who established a cult to the young man after his death:

Athens Acropolis gallery page 32 |

The widow |

| |

The groom |

| |

The snake |

| |

| |

A hero relief on the side of a sarcophagus from Pergamon. Roman period.

A much simpler, cruder relief showing a man wearing a cloak, holding the reigns of his horse.

He stands beside a circular altar in which a flame burns. Behind the horse is a tree

with a snake entwined in its branches.

From the Kestel Dam salvage excavation. Bergama Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A double hero relief from Miletus (Balat), Turkey. Funerary stele, Hellenistic period.

Two naked heroes with cloaks, two grooms or slaves, and two snakes with knotted tails on a pillar.

Izmir Museum of History and Art (Izmir Tarih ve Sanat Müzesi), Izmir, Turkey. |

| |

Large marble grave stele with a hero horseman relief from Thessaloniki, Greece.

1st century BC or 1st century AD; according to other theories, 1st or 2nd century AD;

or even "late Hadrianic period", around 140 AD. Height 180 cm, length 355 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 31 T. Cat. Mendel (Volume 2, 1914) 492. [4]

|

The large size of the stele, made of three tall marble slabs, and the quality of the workmanship points to a commission from a very wealthy family. No inscription was found with the stele to name the dedicators or maker, or to identify it as a grave marker.

The figures are almost life-size. In the centre a horse rider with a spear (missing) and his dog, moving to the right, hunt a wild boar. On the right, the pig crouches, apparently wounded, beneath a tree trunk around which a snake is coiled. The horse's back is covered with an animal skin. On the left of the relief, behind the rider, stand two men, each wearing an exomis (ἐξωμίς), a type of chiton (χιτών, tunic) fastened only at one shoulder. The man in front (right) is bearded and armed with a short sword or dagger. The unbearded man behind him (left) holds a short sword and a shield.

The monument was reused in the building of the Roman period Arch of Galerius (previously thought to be the Porticus of Constantine), on the Odos Egnatia, opposite the eastern entrance to the bazaar of Thessaloniki. It was discovered in 1873, and moved to the old Turkish Imperial Museum in the Agia Irene church, Istanbul in 1874.

Unfortunately the stele is at the top of a dimly-lit stairway which is currently not accessible to the public, so that it is impossible to see it close up. |

|

|

| |

A fragment of a large marble plaque with a relief of a horseman, riding to the right, wearing

a short cloak and a cuirass over a short chiton (tunic) and armed with a spear, confronting

an over-dimensional pouncing lioness. On the left, a dead tree stands behind the horse's

outstretched tail, while behind the lioness is a living tree with a bird standing on one of its

branches. On the right side of the relief, now damaged and barely visible, a hunting dog

attacks the cat's backside, while a second human figure with raised right arm, which

probably held a weapon (perhaps a club), approaches and is about to strike the beast.

Late Hellenistic period. Found during excavations of the Roman Tetrapylon in the city of Rhodes.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The inscribed marble gravestele of Gaeus Cousonios Crispus, set up by Cousonios Titianus.

From Thessaloniki, Greece, 1st century AD, early Roman Imperial period.

The bareback rider, wearing a cloak and short chiton (tunic), approaches an altar in front

of a tree in which a snake is entwined. The man's head is turned to face the viewer.

He raises his right arm in what may be a gesture of greeting/farewell, although some

scholars believe the gesture may be a blessing or benediction, sometimes referred to as the

"benedictio latina". Bluish, large-grained marble. Height 85.5 cm, present width 118.5 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 240 T. Cat. Mendel (Volume 3, 1914) 966.

Entered the museum around 1880. [5] |

| |

Marble funerary relief of a rider from ancient Kalindoia (Kalamoto,

Thessaloniki), Greece. Late 1st - early 2nd century AD.

On the left, the rider, wearing a chiton (tunic) and billowing cloak, approaches an altar

in front of a tree in which a snake is entwined. A small attendant walks behind him.

On the right a mature couple, probably his parents, watch his arrival.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. ΜΘ 6937. |

| |

Hero-horseman relief from a sanctuary in Dion, Macedonia, Greece. Roman period.

A priest throws incense from a casket he holds in his left hand onto the fire on

the altar on the side of which there is a snake. The pig about to be sacrificed in

honour of the deceased horseman (left) stands between the priest and the altar.

Dion Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Marble funerary relief of a rider, from the site of Maximianoupolis (Μαξιμιανούπολις,

also referred to as Maximianopolis in Rhodope), south of the village of Mischos

(Μίσχος Ροδόπης), 7 km west of Komotini (Κομοτηνή), Thrace, northeastern

Greece. Roman period, 1st century BC - 1st century AD.

In Antiquity the city was known as Paisoula (Παισούλα), but is thought to have

been refounded and renamed in the early 4th century AD, perhaps by Eastern

Roman emperor Galerius Valerius Maximianus (reigned 305-311 AD). From

around the 9th century it was known as Mosynopolis (Μοσυνόπολις).

On the left, the heroized horseman, wearing a short chiton (tunic) and billowing cloak,

his right arm raised, rides a rearing horse towards an altar in front of a tree, around

which a snake is coiled. Behind him walks a male attendant, also wearing a short chiton

and cloak. He is clutching something, apparently the horse's tail. To the right of the tree

a woman, covered in a himation (cloak), stands, facing frontally. Below the horse a small

hunting dog confronts a wild boar, which crouches behind the altar.

The relief is cracked and badly damaged; the faces of the three human figures and

the horse have been destroyed. This type of stele was dubbed "Stockwerkstele" by

German archaeologists, since it has reliefs on more than one "storey" or vertical

register. In this case the rider relief is on the lower register, while part of an upper

register and relief, now broken off and missing, can be seen above it. Its subject is

no longer recognizable, but it may have been a nekrodeipno scene (νεκρόδειπνο),

a funerary banquet or symposium in honour of a deceased person; named

Totenmahlreliefs by German scholars (see Demeter and Persephone part 2).

Komotini Archaeological Museum. ΑΓΚ 25. [6]

A modern copy of the relief is displayed, unlabelled, at the gateway to the museum. |

| |

Hero-horseman grave relief from Thasos, Macedonia, Greece. 1st century AD. Height 50 cm.

A young horseman, wearing a short chiton (tunic) and billowing cloak, his right

arm raised, rides a rearing horse to the right where an altar in front of a tree,

around which a snake is coiled. Below the horse a hunting dog confronts a wild

boar, which crouches behind the altar.

The Northern Aegean island of Thasos appears to have had a particularly strong tradition

of hero worship, and a perhaps unique annual civic feast known as the Heroxenia. Since

the mid 19th century over 200 reliefs of heroes, depicted as horsemen or banqueters,

have been unearthed on the island, made over a span of eight centuries. [7]

Thasos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2652. |

| |

Hero-horseman relief from Amphipolis, Macedonia, Greece. Hellenistic period.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 722. |

| |

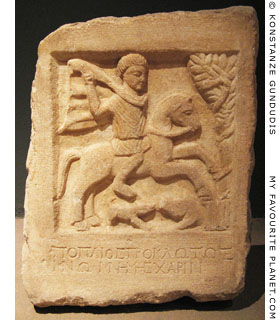

The top of a marble the grave stele of

Proklos with a relief of a horseman

hero, from Thessaloniki, Greece.

The bareback rider on a rearing horse,

wears the usual garb of a short chiton

and cloak, in front of an altar and a

snake-entwined tree. Below the horse

his dog confronts a wild pig. However,

rather than holding a hunting weapon,

with his raised right hand the rider

appears to be making a gesture of

blessing or benediction, sometimes

referred to as the "benedictio latina".

Circa 2nd century AD. It was taken to

the Istanbul Archaeological Museum

at unknown date. Height 42 cm,

width 33 cm, depth 9 cm.

Below the relief is a short two-line

dedication, using a conventional phrase,

typical for such funerary monuments.

The father Publius (Greek, Πόπλιος,

Poplios) dedicated the stele to his

dead son Proculus (Greek, Πρόκλος,

Proklos). Both names are Roman.

Πόπλιος Πρόκλῳ τῷ τέ-

κνῳ μνήμης χάριν.

Poplios [set this up] for Proklos,

his child, in remembrance.

Inscription IG X,2 1 851 at The

Packard Humanities Institute.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 272 T. Cat. Mendel 968

(Volume 3, 1914, pages 181-182). |

|

A Thracian marble horseman relief

found at Varna, Bulgaria, the location

of the ancient Greek colony Odessos,

on the Black Sea coast. The young

bareback rider, wearing a cloak and

short chiton (tunic), approaches an

altar in front of a tree in which a snake

is entwined. His head is turned right

to face the viewer. His left arm, carved

in lower relief than the rest of the

figure, is raised in greeting/farewell.

Height 34.5 cm, width 23.5, depth 6.5 cm.

The two-line inscription in Greek lettering

above the figure is badly worn, and only

the last letters of each line are visible.

[-----] Χρυσογόνου

[-----] χαῖρε

[-----] Chysogonou

[-----] farewell

Inscription IGBulg I² 163

Varna Archaeological Museum, Bulgaria. |

|

| |

Pergamon

gallery 2 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Hero relief relief from Pergamon

White marble. Late 3rd century - early 2nd century BC.

Found in October 1886 during the building of a house in the valley of Kestel Çayı (Ketios river).

Height 67.7 cm, width 81 cm, depth 7 cm (top) - 15.5 cm (bottom).

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 362 T.

Cat. Mendel (Volume 1, 1912) 90.

See:

Franz Winter (1861-1930), Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VII, Text 2: Die Skulpturen mit Ausnahme der Altarreliefs, pages 248-249. Verlag von Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

Gustave Mendel (1873-1938), Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines, Tome premiere (Volume 1 of 3), No. 90, pages 237-239. Musée Impérial Ottoman, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1912.

Volker Michael Strocka, Volkskunst im klassischen Griechenland (Tafeln 50-53), in Angelos Delēborrias et al, Praktika tu XII Diethnus Synedriu Klasikēs Archaiologias, Athens, 4-10 September 1983.

2. This cloak has been referred to as a chlamys (Greek, χλαμύς). However, the chlamys is usually shown as a shorter riding cloak worn by hunters and soldiers.

3. Thracian rider monuments

Thracian riders are also referred to as Thracian horsemen and Thracian heroes.

See:

Nora Dimitrova, Inscriptions and iconography in the monuments of the Thracian rider.

Hesperia Volume 71, No. 2 (April - June 2002), pages 209-229. American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Article on a relief of a Thracian hero, 2nd century AD from Bulgaria, in the UNESCO works of art collection.

4. Large hero horseman relief from Thessaloniki

See:

Gustave Mendel, Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines, Tome second (Volume 2 of 3), No. 492, pages 172-175. Musée Impérial Ottoman, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1914. The second of three volumes in Mendel's sculpture catalogue, and the first to be published in 1914, is sometines referred to as "Mendel 1914a".

Ludwig Budde, Istanbuler Reiterrelief. In: Belleten Volume 17, pages 475-482. Turkish Historical Society (Türk Tarih Kurumu), Ankara, 1953. At the website of Belleten magazine.

Theodosia Stefanidou-Tiveriou, The great mounted horseman relief from Thessaloniki (in Greek and English). In: Michalis Tiverios, Pantelis Nigdelis, Polyxeni Adam-Veleni (editors), Threpteria, Studies in Ancient Macedonia, pages 142-170. Εκδόσεις Α.Π.Θ. – Αuth Press, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, 2012. academia.edu.

5. Gravestele of Gaeus Cousonios Crispus from Thessaloniki

See:

Gustave Mendel, Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines, Tome troisième (Volume 3 of 3), No. 966, pages 178-179. Musée Impérial Ottoman, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1914. The third of three volumes in Mendel's sculpture catalogue, and the second to be published in 1914, sometines referred to as "Mendel 1914b".

6. Hero relief in the Komotini Museum

See:

Dimitra Andrianou (Δήμητρα Ανδριανού) and Lorenzo Lazzarini, Initial archaeometric studies of the Marmaritsa quarry (Maroneia) and twelve Thracian funerary reliefs in the Komotini Museum (Greece). In: ASAtene (Estratto da Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Orient), Volume XCI, Serie III, 13, 2013, pages 387-408. SAIA, 2015. At scuoladiatene.it.

7. Hero reliefs from Thasos

See:

Bernard Holtzmann, Sculpture de Thasos. Corpus des reliefs: Reliefs à theme heroique. Etudes Thasiennes, Band 25. École Française d’Athènes, 2018. |

|

|

Maps, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

|