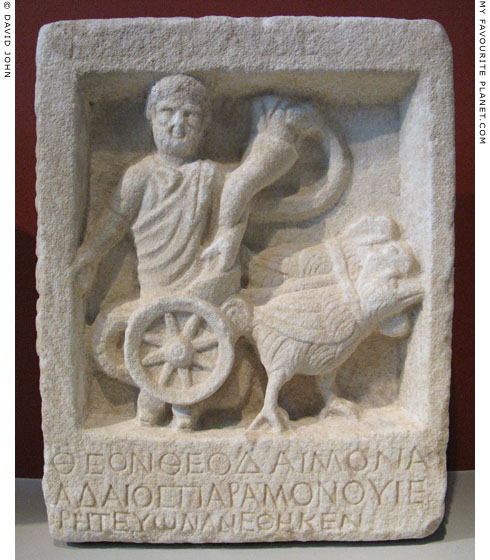

| |

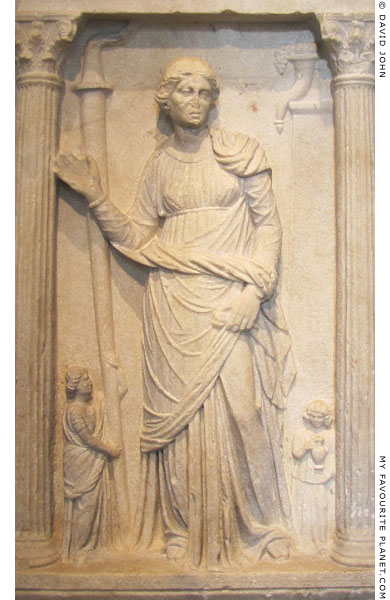

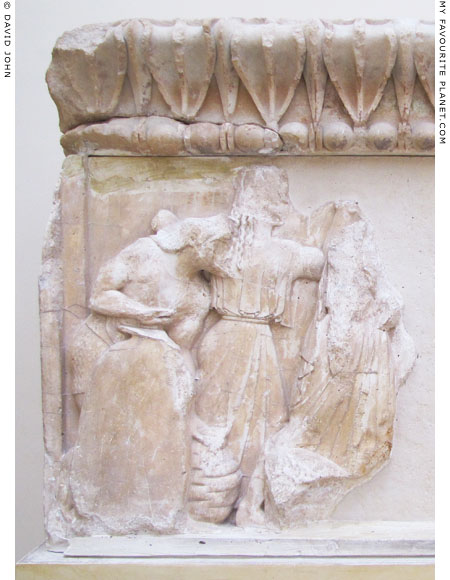

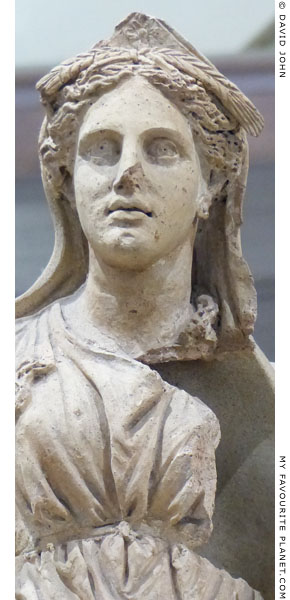

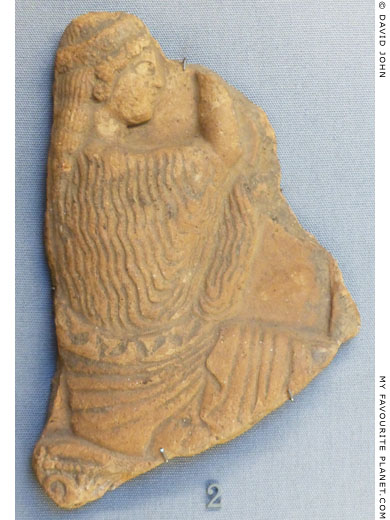

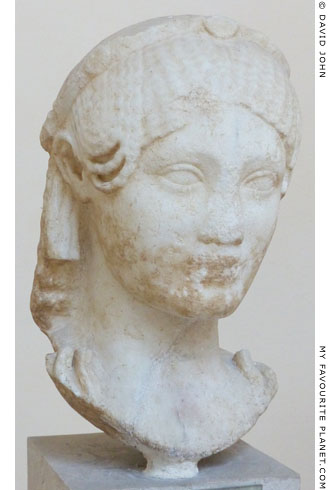

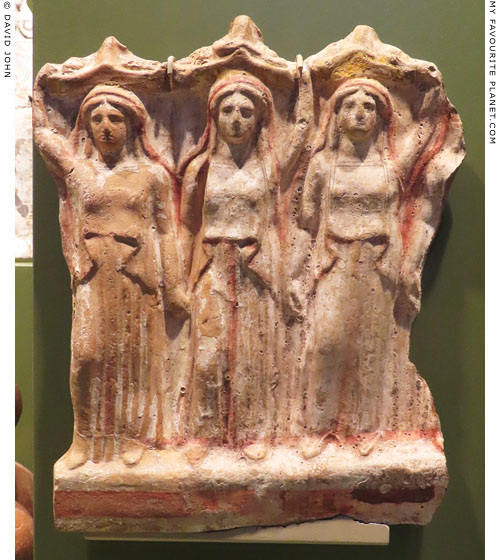

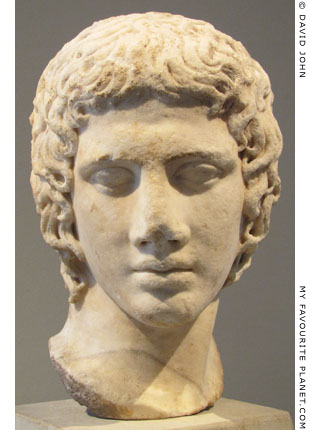

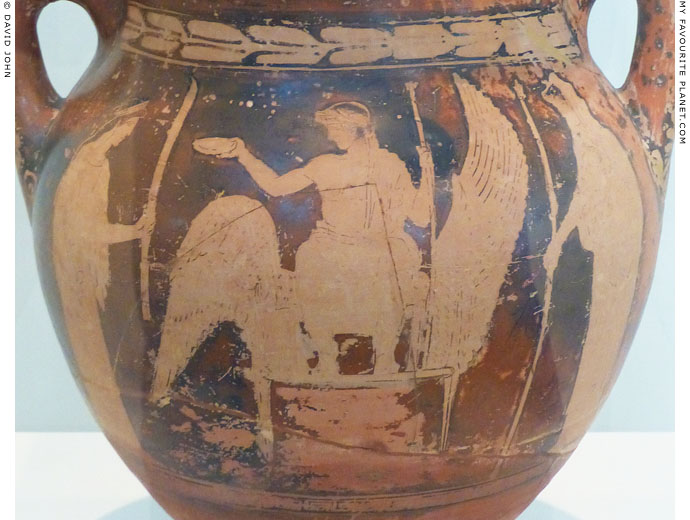

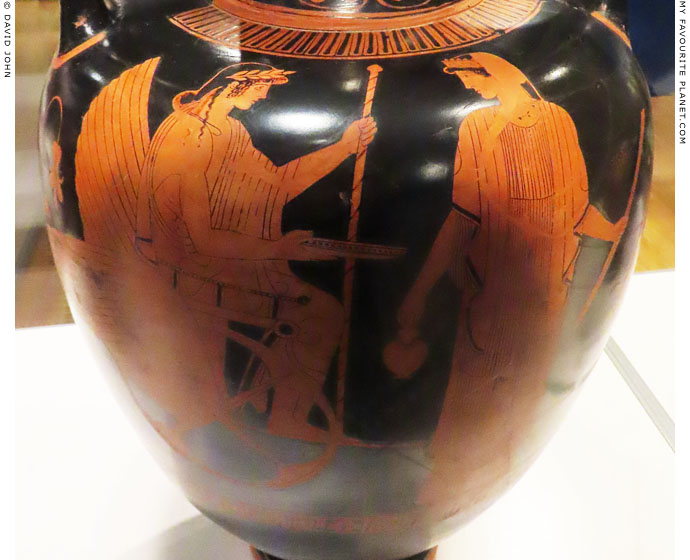

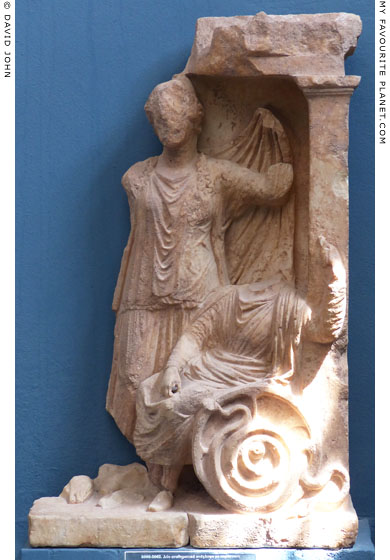

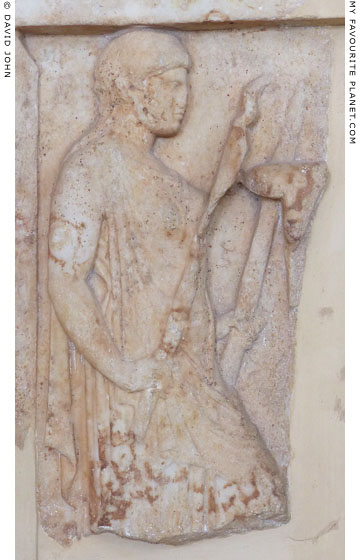

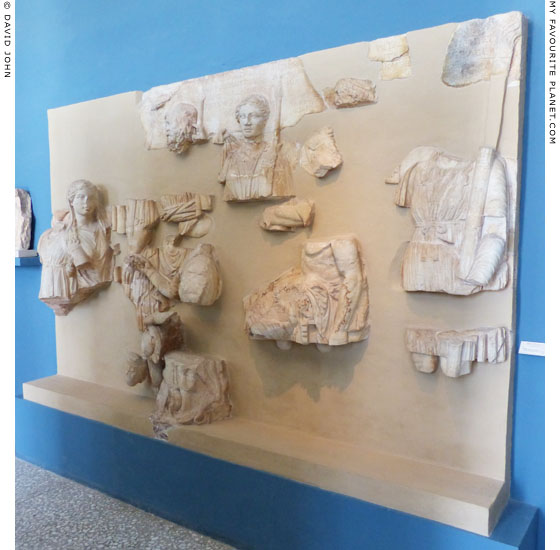

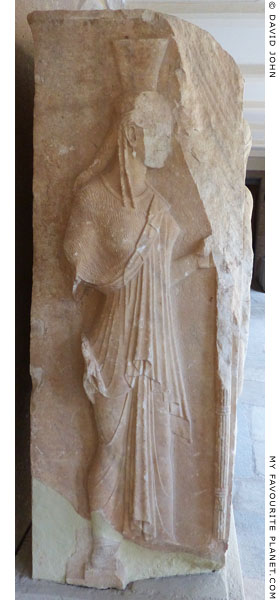

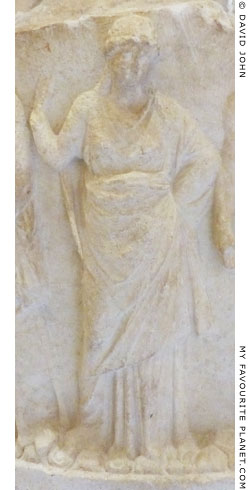

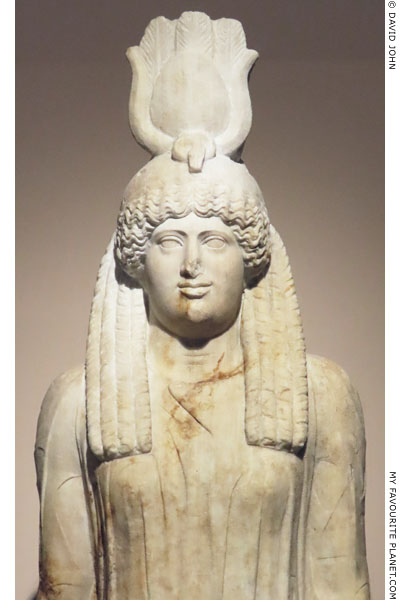

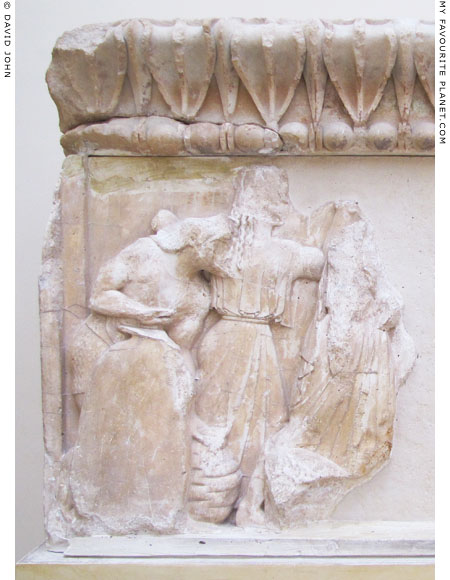

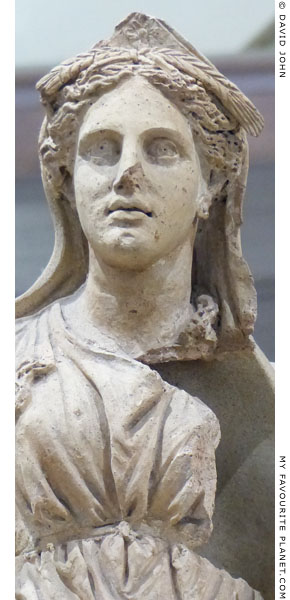

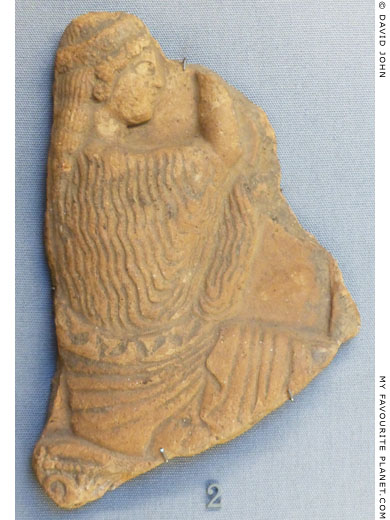

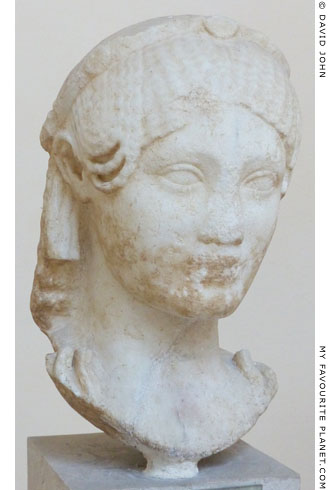

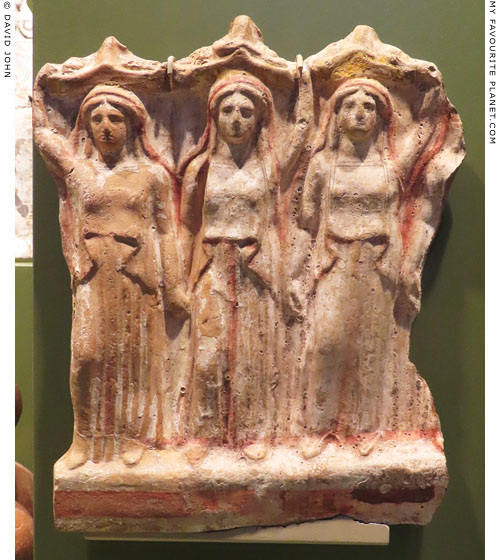

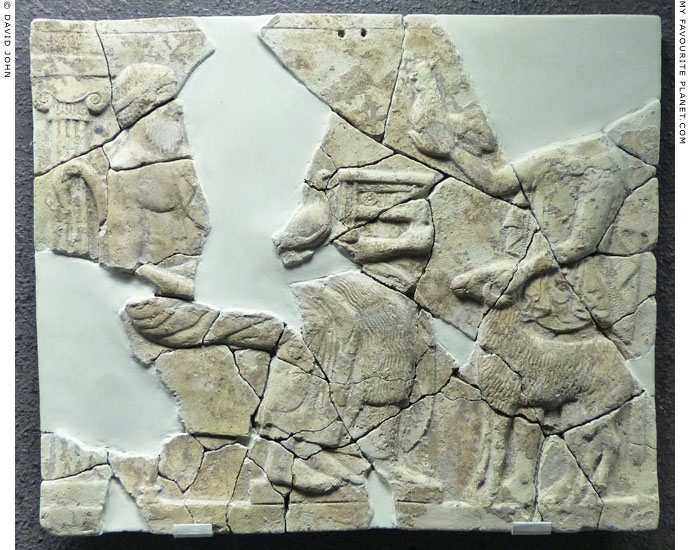

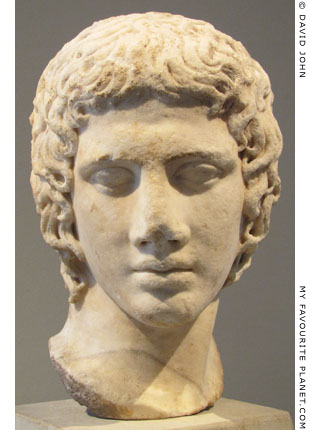

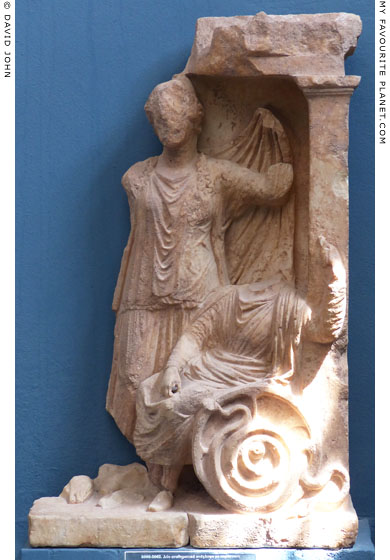

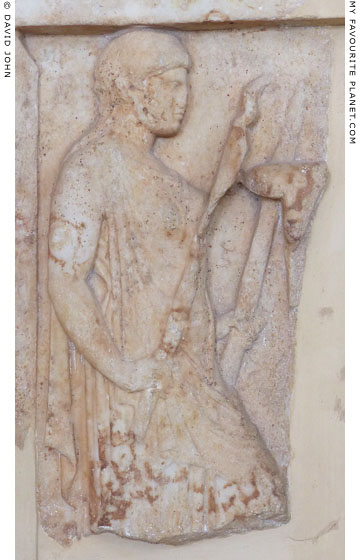

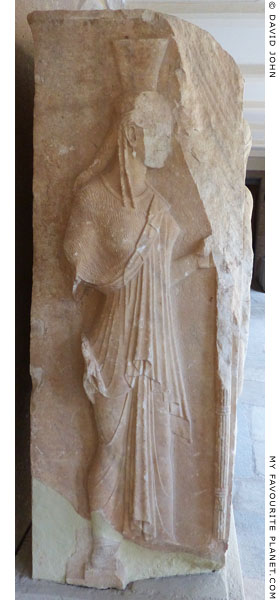

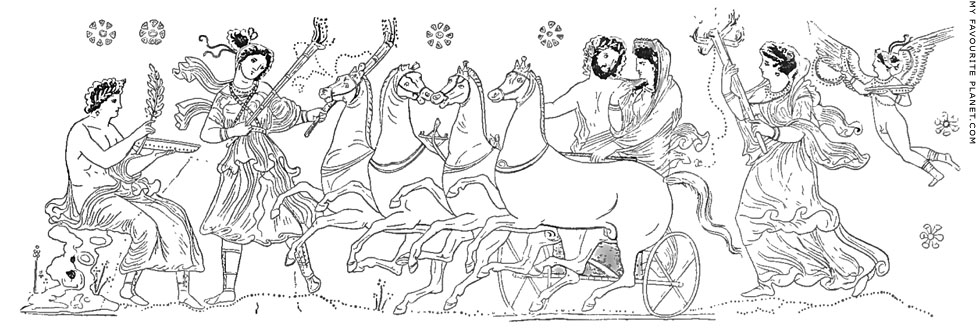

A fragment of a relief with a depiction of three goddesses, identified as Athena,

Hera and Demeter, from the east side of the frieze of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi.

The treasury was built for the people of the Aegean island Siphnos

around 525 BC (before 524 BC). Parian marble.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

|

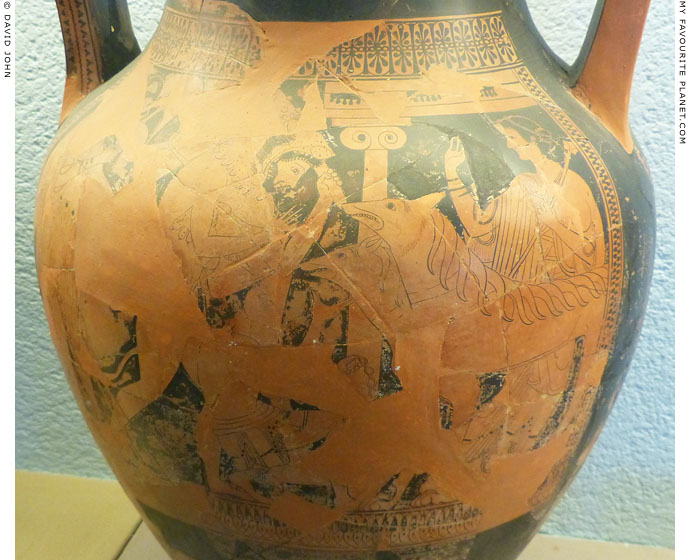

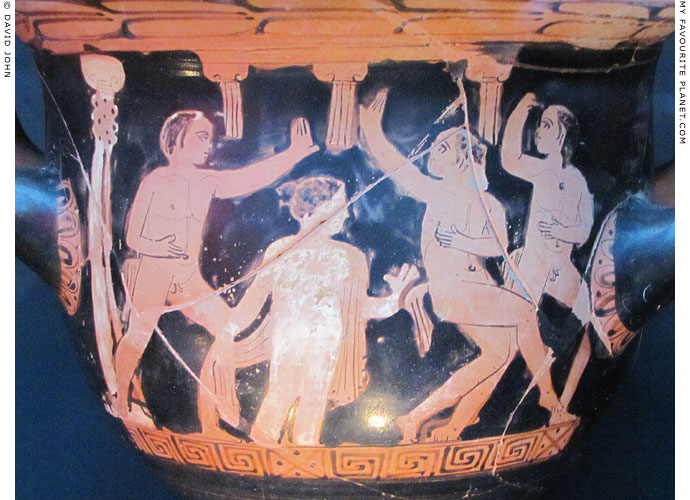

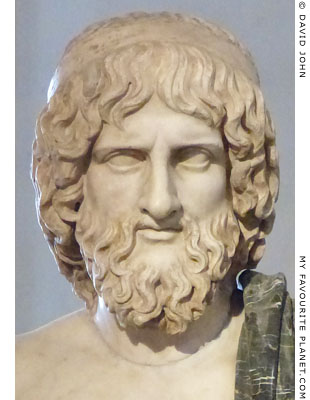

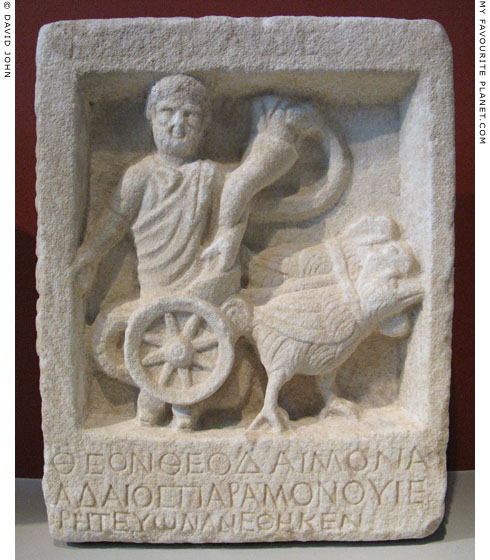

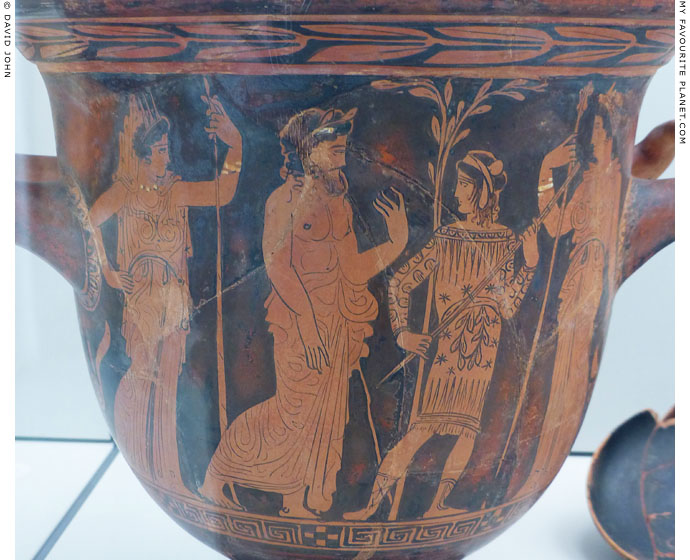

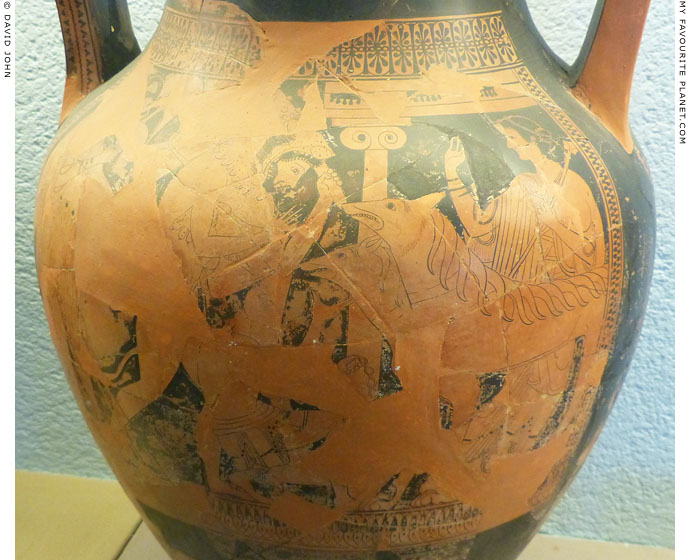

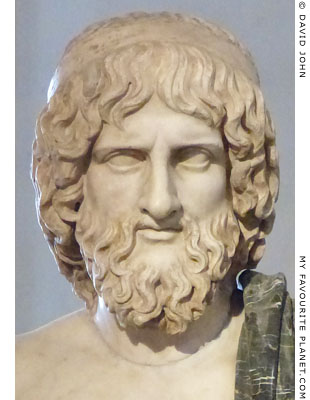

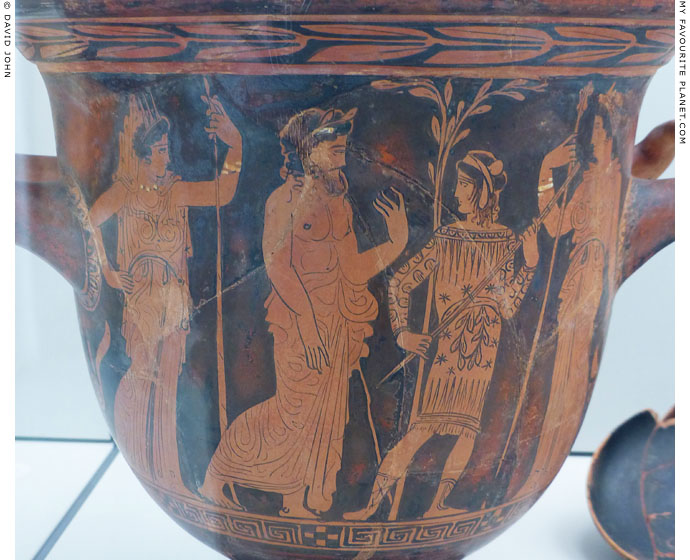

The entablature of the Ionic treasury was decorated with a frieze on all four sides, each with a long relief depicting a mythological theme. The pedimental relief at the rear of the building, the east side, parts of which have survived, depicts Zeus intervening in the struggle between Apollo and Herakles when the latter attempted to steal the oracular tripod from Apollo's temple at Delphi.

The theme of the frieze relief below the east pediment is the Trojan War (see Homer), divided into two scenes. The scene on the left (south) side is an assembly of the Olympian gods. Those who sided with the Trojans (Ares, Aphrodite, Artemis and Apollo) are seated to the left, and the supporters of the Achaeans (Greeks) on the right (Athena, Hera and Demeter). The supreme god Zeus is enthroned in the centre, and a now missing part of the scene is thought to have shown the figure of Thetis, the mother of the Greek hero Achilles, pleading with Zeus for her son's safety (see Homer part 2).

The scene on the right (north) side of the relief shows a battle around the body of a fallen warrior between Trojans, fighting from the left and Achaeans (Greeks) on the right. On the far right, the elderly Nestor urges the Achaeans on.

The identifications are those on the museum labels. The names of the characters in the relief were originally painted next to the figures, but most are now partly or wholly illegible. A number of scholars have attempted to reconstruct the inscriptions and identify the figures, leading to much conjecture and debate. According to other interpretations of a faint and fragmentary inscription, the figure usually identified as Demeter may be Thetis or Themis.

See images of the entire east pediment and frieze relief in Homer part 2.

See also a relief of Demeter and Persephone from the north side of the frieze below.

The unknown sculptor of the frieze reliefs on the north and east sides of the Siphnian Treasury has been named "Master B", while the artist who made the south and west reliefs is known as "Master A". See the Aristion of Paros page for further details. |

|

| |

|

|

|

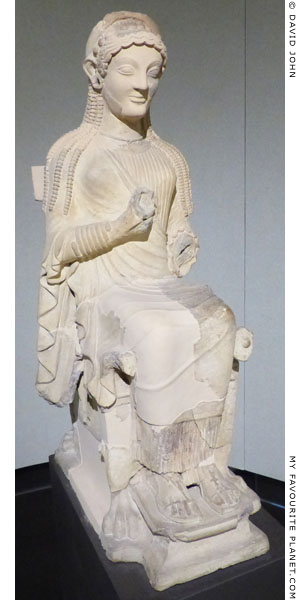

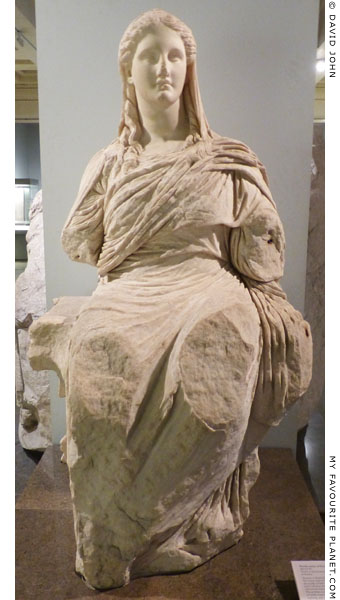

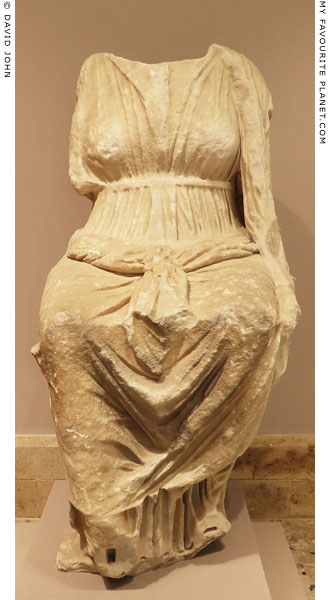

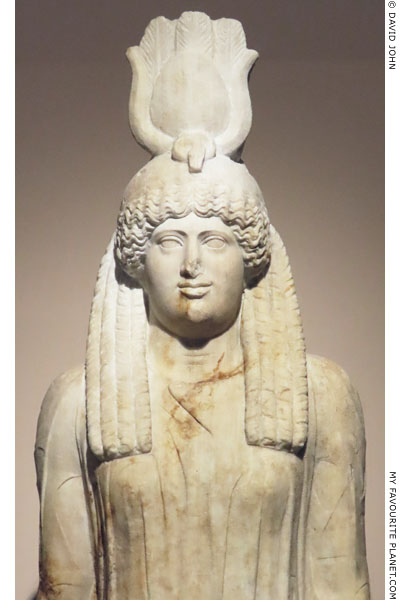

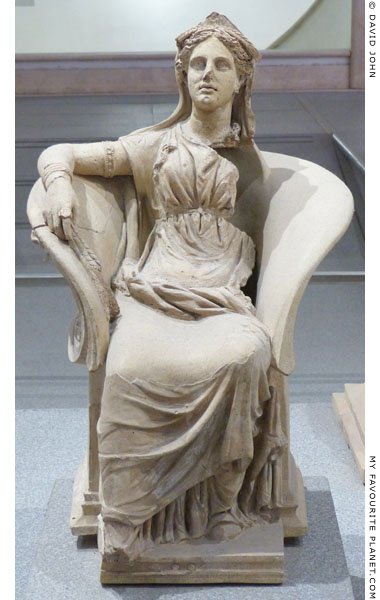

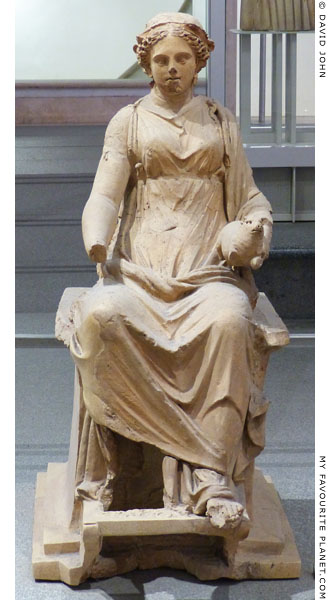

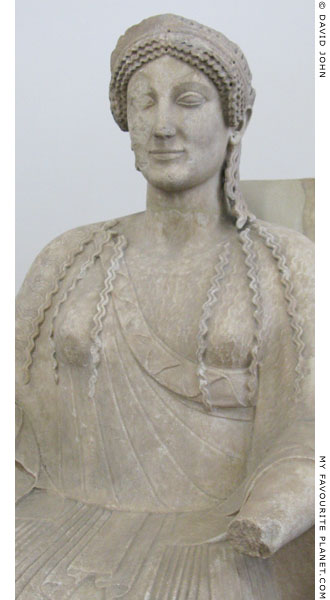

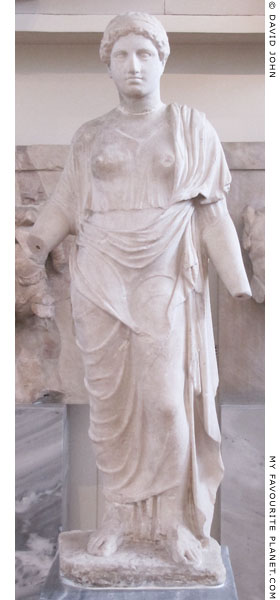

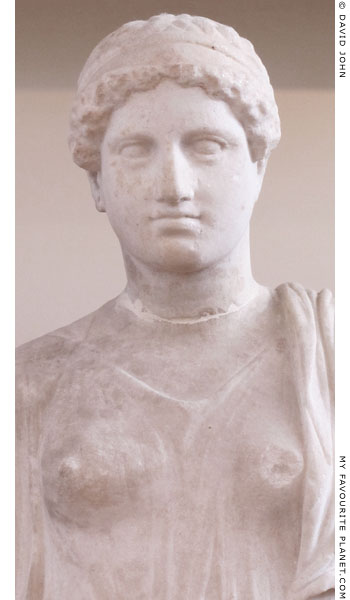

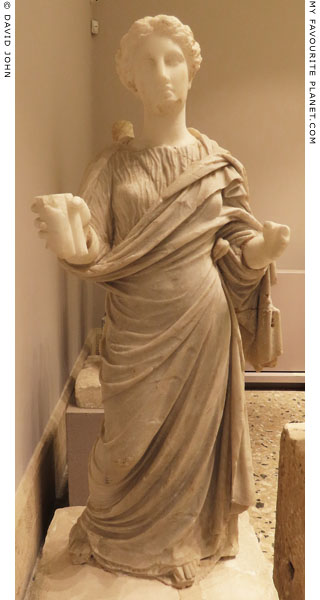

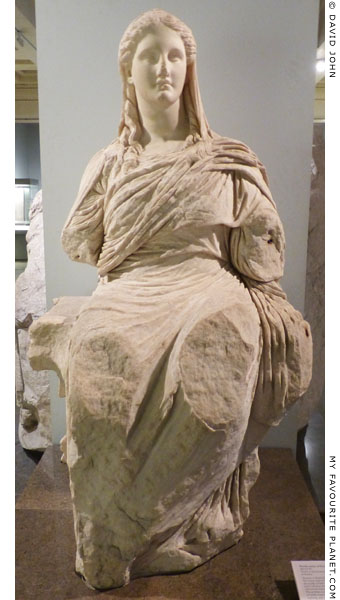

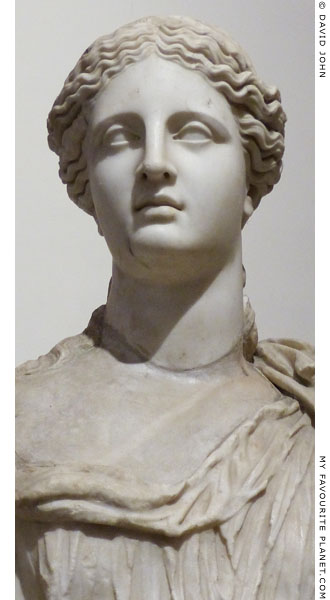

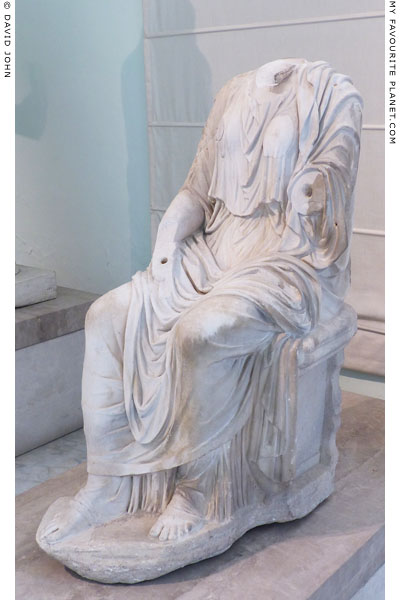

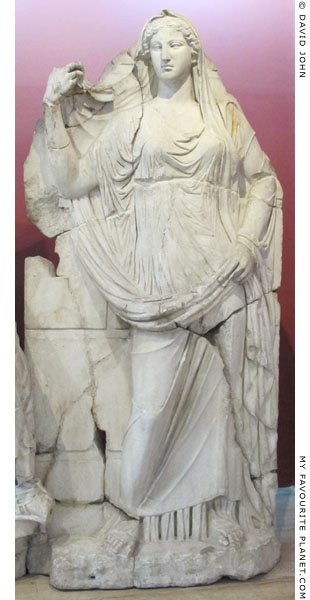

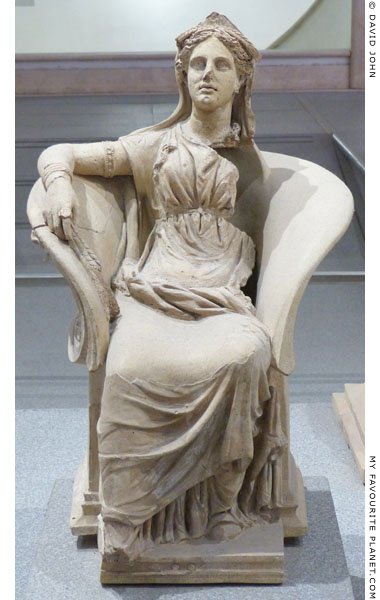

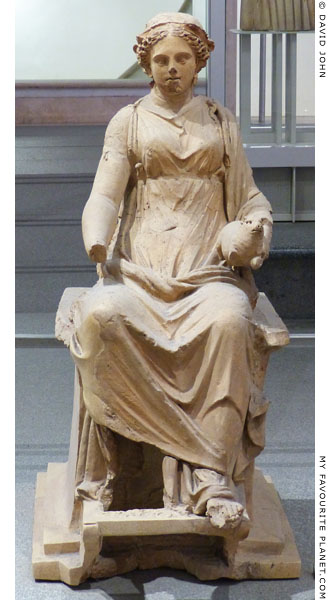

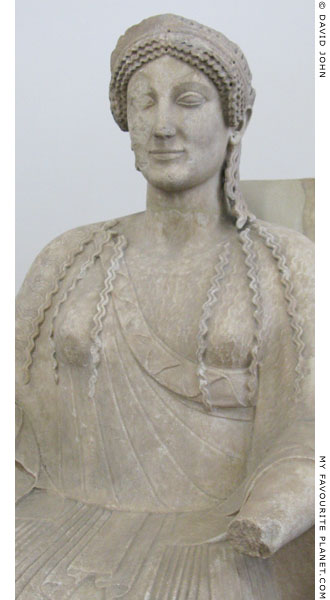

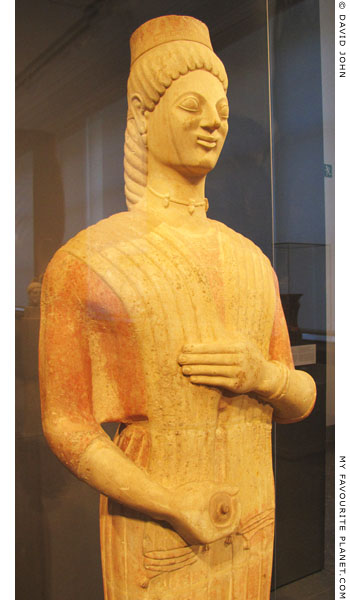

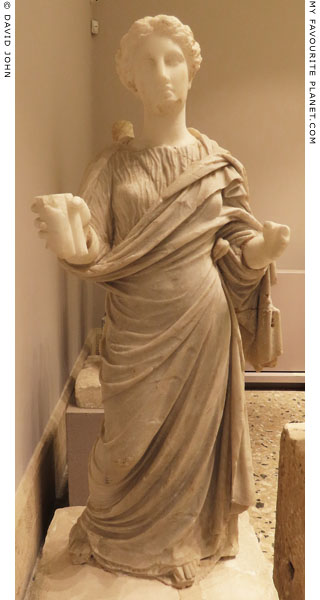

Life-size marble statue of enthroned Demeter, known as "Demeter of Knidos". 350-330 BC.

Excavated in 1858 by the British archaeologist Charles Thomas Newton,

in the sanctuary of Demeter at Triopion (Τριόπιον), Knidos, Caria

(Yazıköy, Muğla Province, Turkey). [1] Height 152 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1859.11-26.26 (Sculpture 1300).

|

|

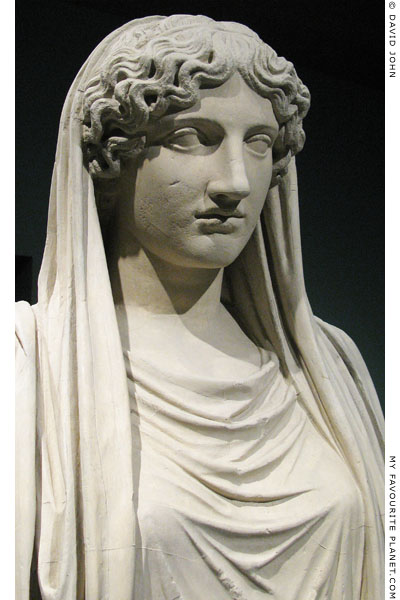

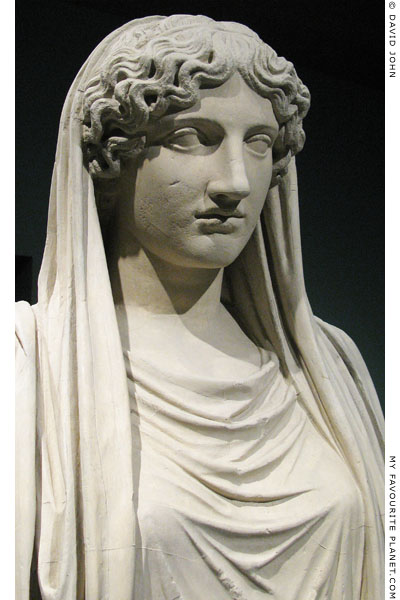

The top and back of the head as well as the torso and legs of the figure are covered by a himation (cloak). In classical art, a person or deity depicted with the the top of the head covered in this way is usually referred to as "veiled".

The head was sculpted separately from the body using finer marble. Her face appears elongated, with a long nose and cheeks, as well as a high forehead and hairline. The folds of the garments are exceptionally deep around her breast and left shoulder. The lower arms and hands are missing, but she probably held a libation bowl or torch. The goddess is depicted as the epitome of Greek womanhood, serene, mature, motherly and modestly veiled. It is thought that a statue of her daughter Persephone may have stood next to her. |

|

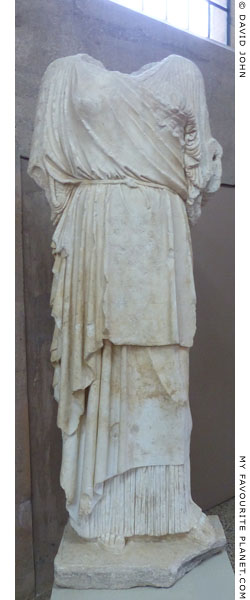

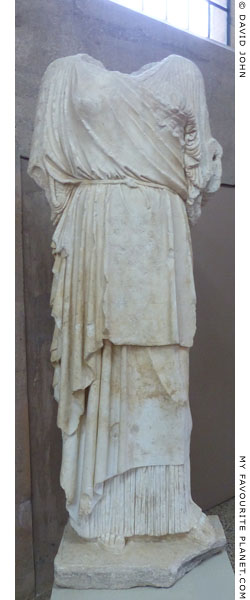

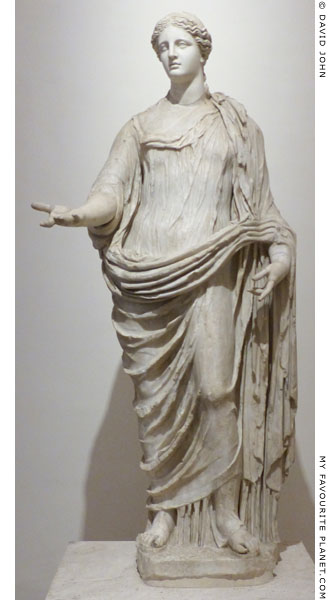

| |

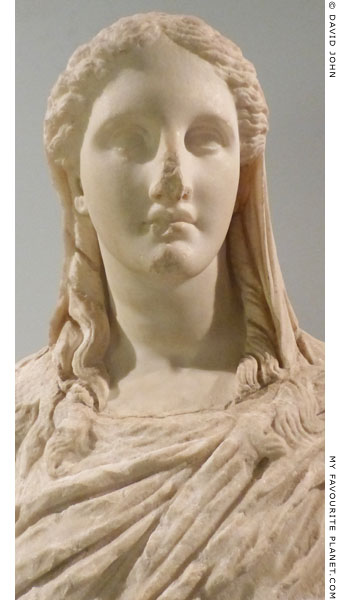

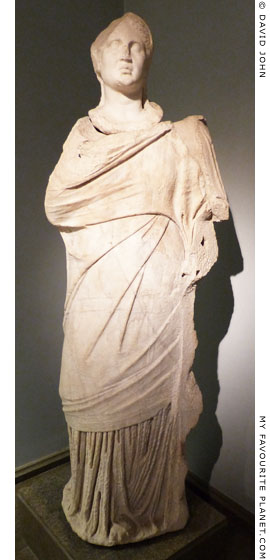

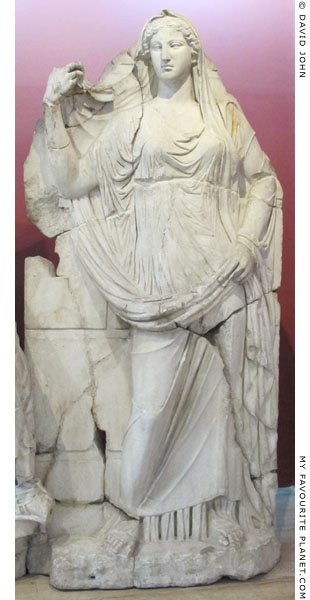

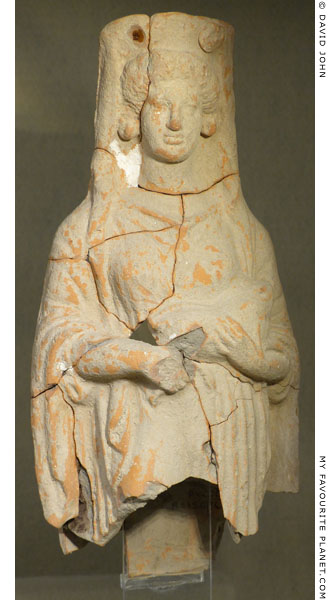

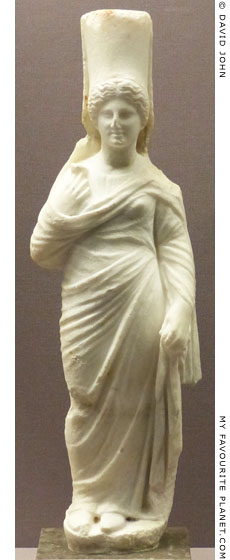

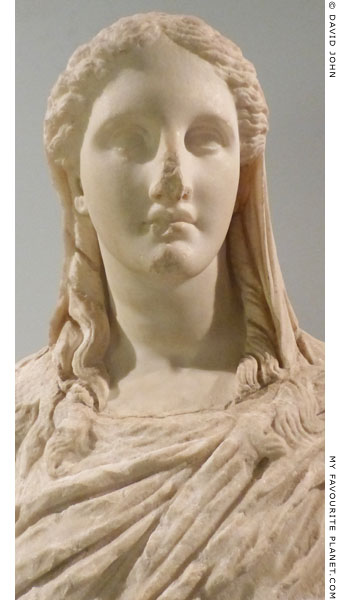

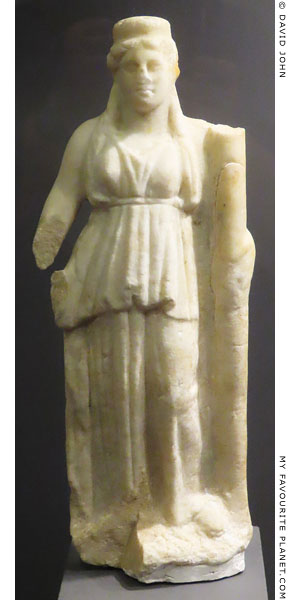

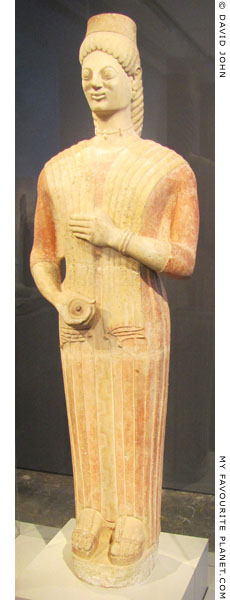

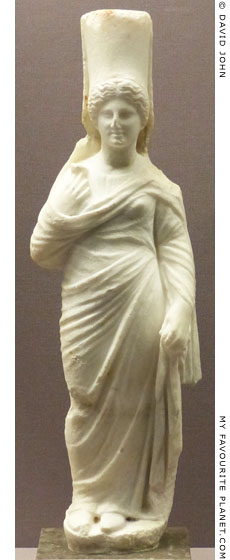

Marble statue, perhaps

a priestess of Demeter.

2nd century BC. Excavated in 1858

by Charles Thomas Newton in the

sanctuary of Demeter, Knidos.

[see note 1]

A mature woman wearing a himation

over a chiton. The head was sculpted separately and inserted into the body.

British Museum.

Inv. No. GR 1859.11-26.25

(Sculpture 1301). |

|

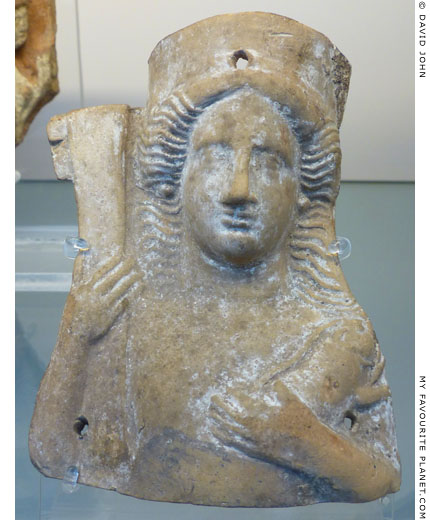

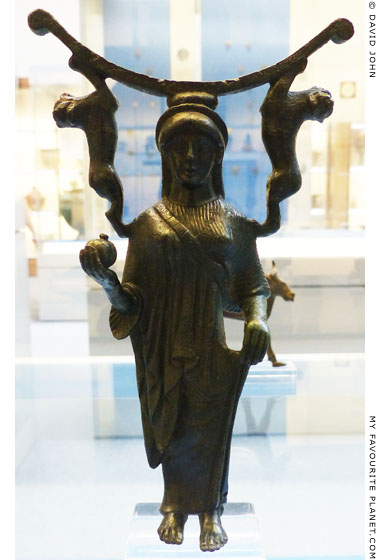

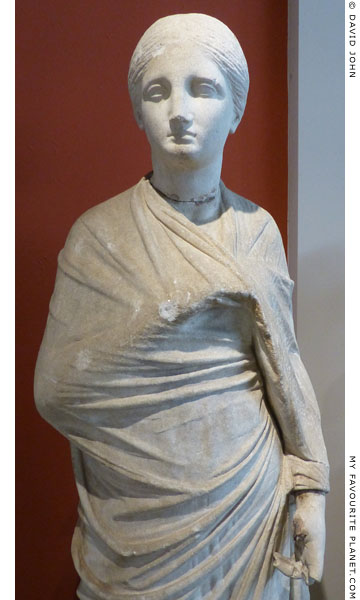

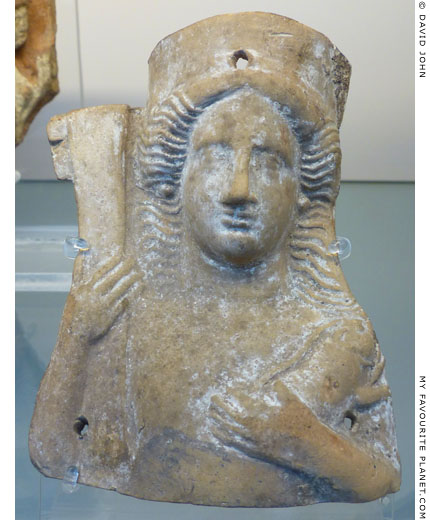

Terracotta head of an old woman, perhaps

Demeter, made at Knidos around 300 BC.

Excavated in 1858 by Charles Thomas Newton,

in the sanctuary of Demeter, Knidos, Caria.

[see note 1]

While Demeter was searching for Persephone

she took on the form of an old woman called

Doso (Δώσω, Giver) and was offered hospitality

in Eleusis by King Keleos and Queen Metaneira.

The object she carries on her head may be the

sacred kiste (cista mystica), which contained

the sacred objects of the Mysteries.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1859.12-26.174.

See also a statuette of Persephone

from Knidos below. |

|

| |

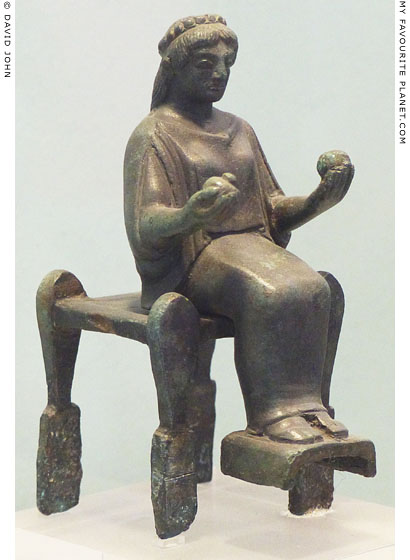

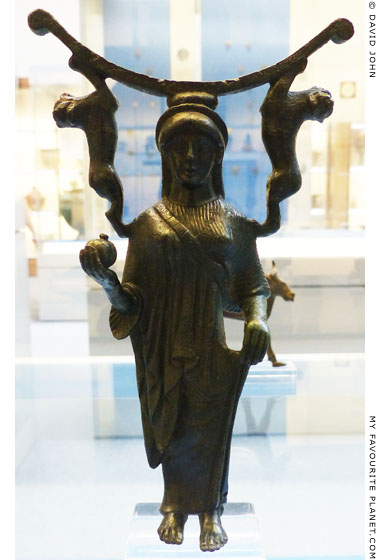

Part of a bronze statue of a veiled female, thought to

depict Demeter. Found in 1953 by sponge fishermen in

the sea near Bodrum (ancient Halicarnassus), Turkey. [2]

Hellenistic period, 4th century BC. Height 81 cm.

Izmir Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 3544. |

| |

|

|

|

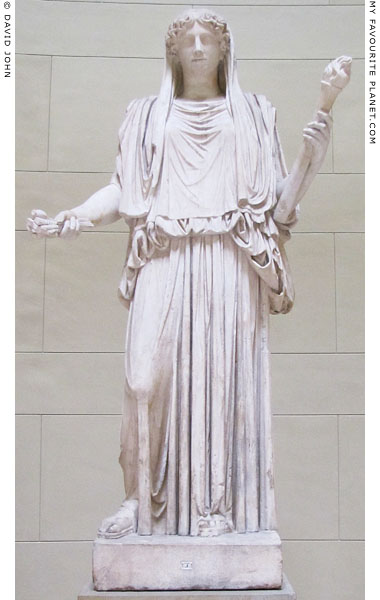

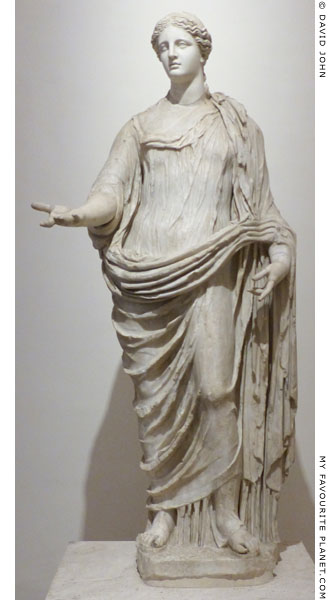

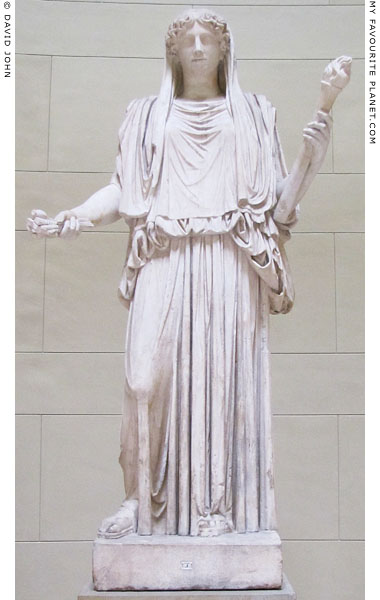

Plaster cast of a "Demeter Cherchel" type statue. Height without base 233 cm.

Antikensammlung, Berlin State Museums (SMB).

|

|

The marble original in the Altes Museum, Berlin (see photo below) is thought to be a Roman period copy, made around 150 AD, of a lost work of circa 450 BC. It is one of a number of similar, over-lifesized statues of the type named after the two examples discovered in Cherchel (Caesarea Mauretaniae), now in the Archaeological Museum of Cherchell, Algeria.

The cast does not include the modern lower arms and attributes which were added to the statue during restorations in the 18th and 19th centuries. The original was recorded by Ulisse Aldrovandi in the mid 16th century (Delle statue antiche ..., in Le antichita de la citta di Roma, 1556, 1558, 1562) as standing in the garden of the Palazzo Soderini, Rome. It was purchased in Rome by the art dealer Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi in 1766 for King Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great, 1712-1786) who placed it outside the Neue Palais, Sanssouci, Potsdam (see photo below). |

|

| |

The "Demeter Cherchel", with the restored arms and hands, in the

dimly-lit rotunda of the Altes Museum, Berlin. The veiled figure holds

a torch in the left hand and poppies and ears of grain in the right.

White, fine crystalline marble with grey discolouring.

Height with base 361 cm, without base 233 cm, width 120 cm,

depth 74 cm. Height of face (hairline to chin) 20 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 83. |

| |

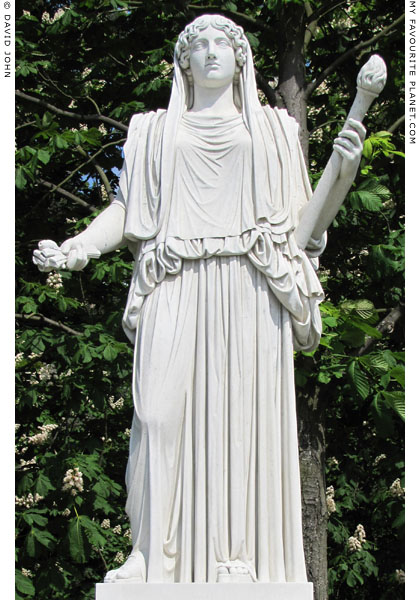

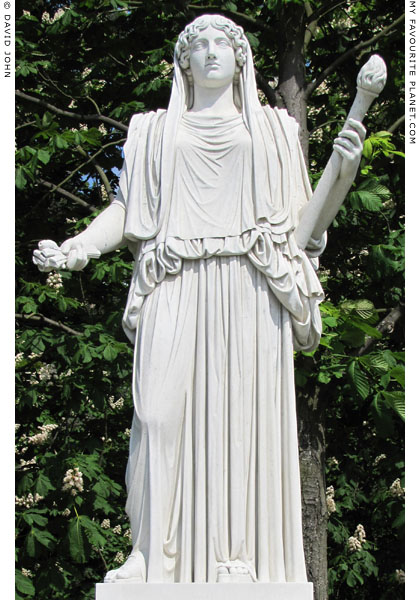

A copy of the restored Berlin "Demeter Cherchel" in Sanssouci.

Made 1848-1859 by Alessandro and Francesco Sanguinetti [3].

Exhibited in the Half Rondel, in the gardens of

the Neues Palais, Sanssouci, Potsdam, Germany. |

| |

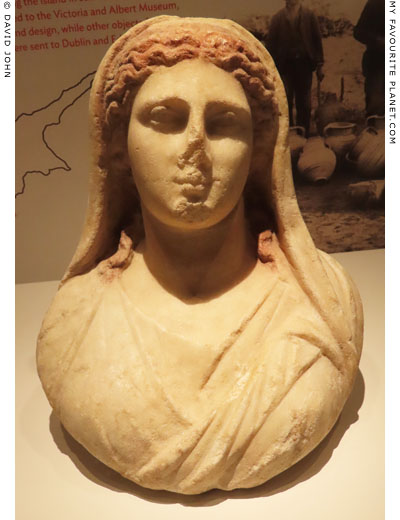

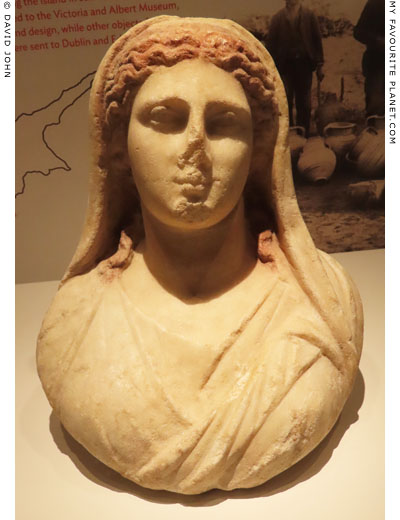

A marble bust of a veiled female from Limassol, Cyprus.

The subject is described by the museum labelling merely as "a woman",

without further explanation. It is not clear whether it is thought to be a

portrait of a mortal or representation of a goddess, perhaps Demeter.

Classical or early Hellenistic period, 475-312 BC. Found on Agkiras Street, Limassol.

Limassol Archaeological Museum.

Exhibited in the exhibition Cyprus - Eiland in beweging (Cyprus - a dynamic island),

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands, 11 October 2019 - 15 March 2020.

See more about the worship of Demeter and Persephone on Cyprus below. |

| |

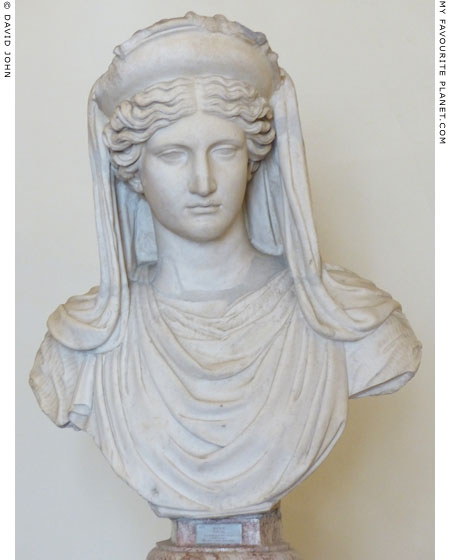

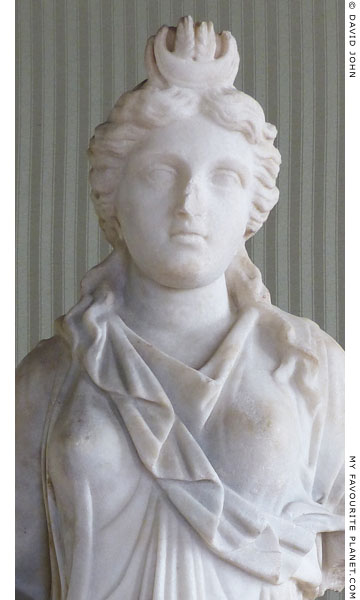

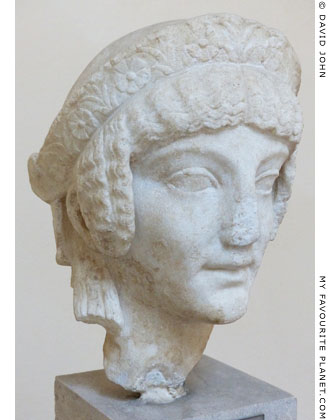

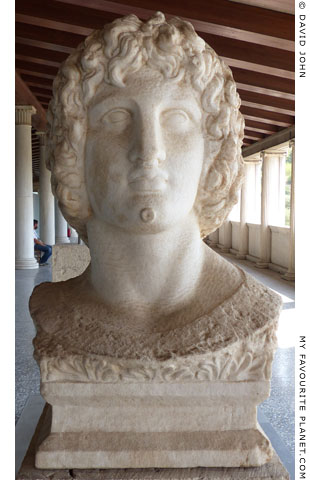

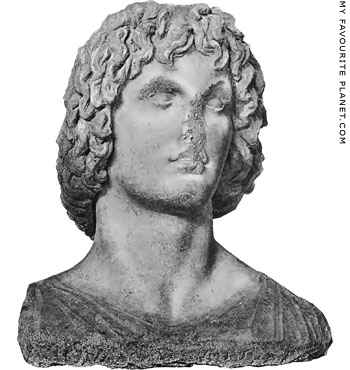

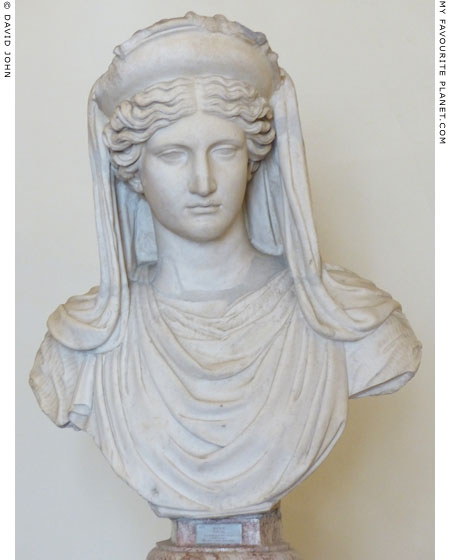

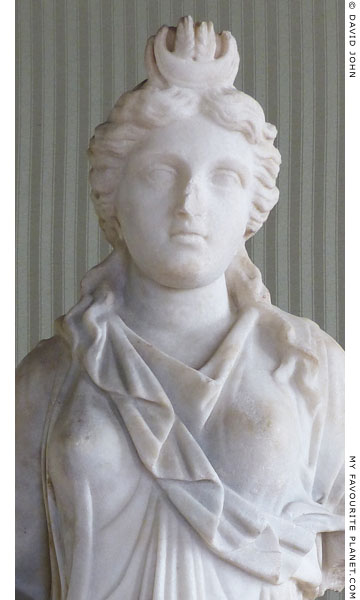

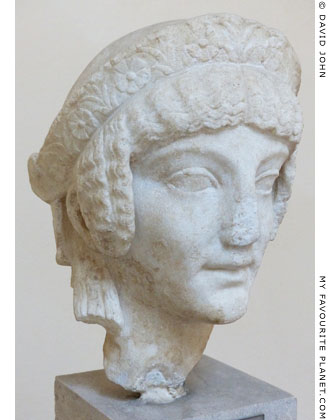

Marble bust of Demeter wearing a veil and high diadem.

Provenance unknown. Coarse-grained marble. A 2nd century AD Roman copy

after Greek prototypes of the 5th - 4th century BC. It may be an idealized

portrait of a member of the Roman imperial family. The diadem was originally

decorated with small pearls, now lost. The tip of the nose has been restored.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome, Italy. Inv. No. 8596.

Boncompagni Ludovisi Collection, from the Cesi Collection. |

| |

|

|

|

Colossal marble statue of Demeter.

Pentelic marble. Roman period copy after a Greek original of the 5th century BC.

From the Horti Maecenatiani (Gardens of Maecenas), Rome. Found in 1876 in the

area of the Auditorium. The statue probably stood in a devotional site in the gardens.

Several ancient artefacts have been discovered at this location, including a number

associated with the worship of Dionysus (see the Dionysus page).

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 905. |

|

| |

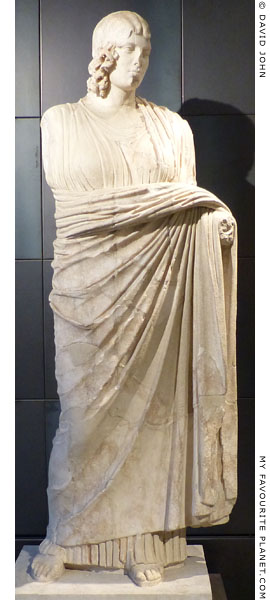

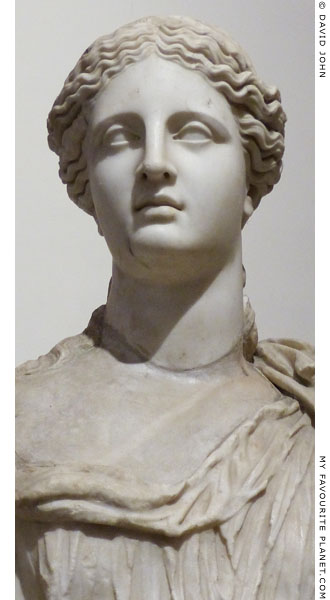

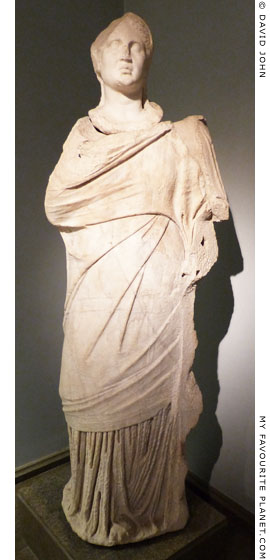

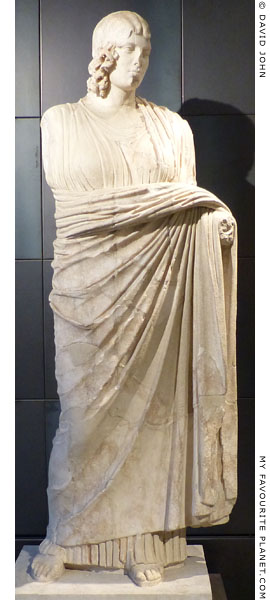

Over lifesize marble statue of Demeter.

Early Roman period. From the Peribolos

of Apollo in the Forum of Ancient Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. S 67. |

|

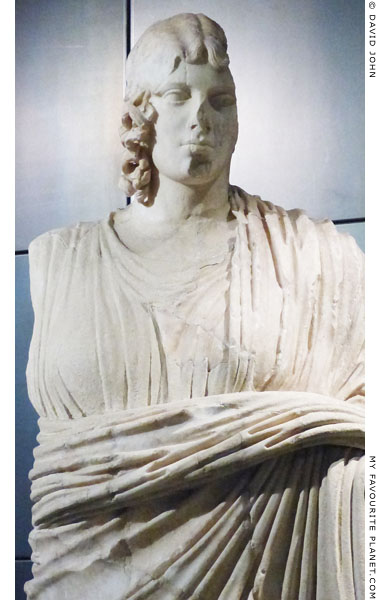

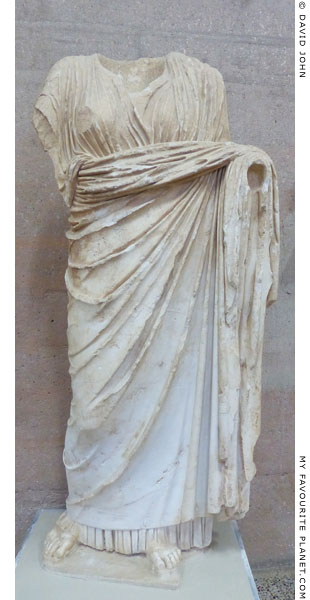

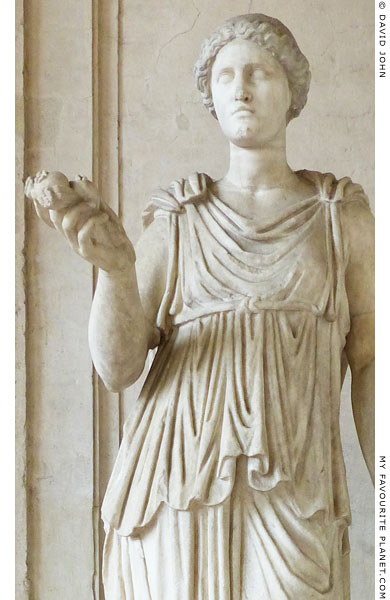

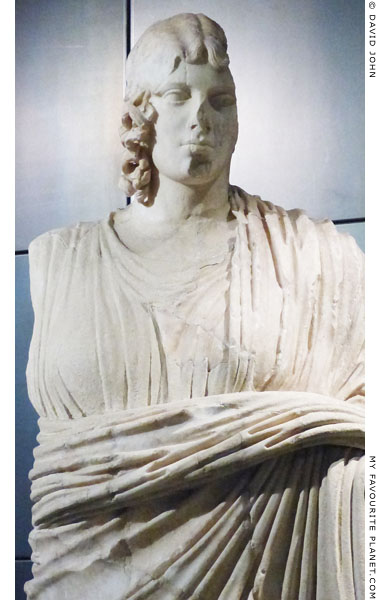

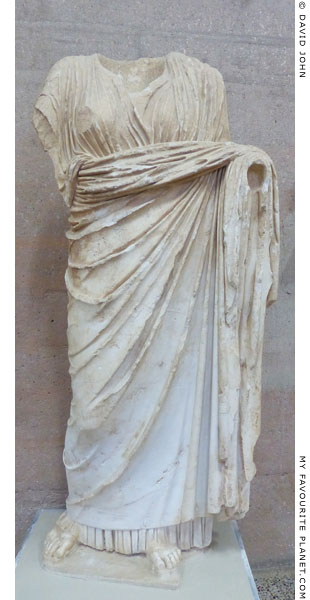

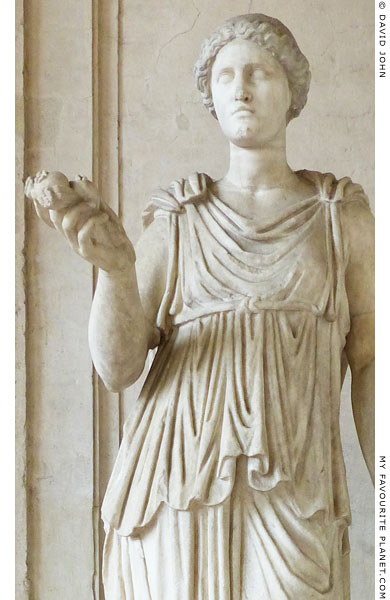

Over lifesize marble statue

of Demeter or Persephone.

Roman copy of a 5th century BC original.

From the Peribolos of Apollo, Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. S 68. |

| |

| See also the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Corinth in Part 1. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Marble statue of Demeter.

Coarse-grained marble. Roman Imperial period.

The figure wears an elegant, tightly clinging garment, slipping at the right

shoulder, typical of statues of Aphrodite and also of portraits of women of

imperial rank. It was restored with arms and a head resembling portraits of

Faustina the Younger (see below), and later the head was replaced with the

present one. The modern identification of the figure as Demeter is based on

the gesture of the outstretched right hand, indicating a product of the earth.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 8546. Ludovisi Collection. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Marble statue of Demeter holding poppies and ears of corn in her raised right hand.

Courtyard of Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Not labelled, Inv. No. 49 (?). |

|

| |

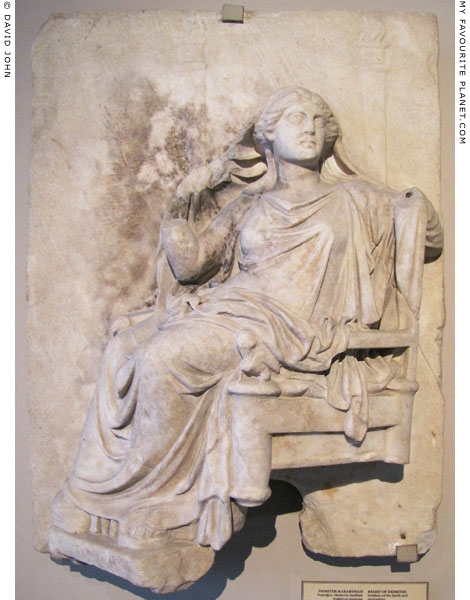

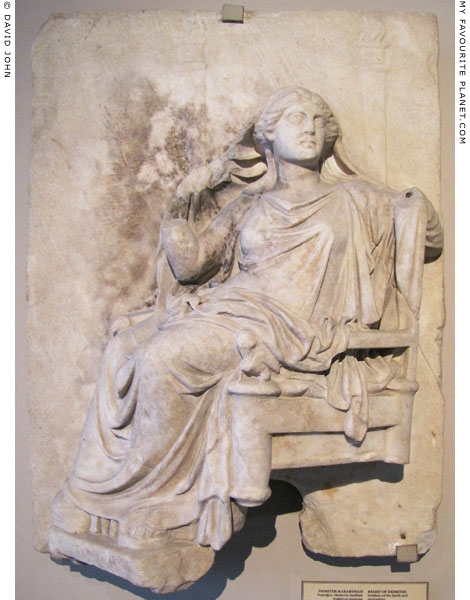

Marble relief of Demeter, veiled and enthroned.

From Kozçeşme village (Biga/Çanakkale), northwestern

Anatolia, Turkey. Late Classical period, 4th century BC.

The enthroned figure turns her head and torso to her left. With her

right hand she pulls at the edge of her himation (cloak), part of

which covers the top of her head. Her left arm rests on the back

of the throne. Behind her stand two long torches in lower relief.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4942 T. |

| |

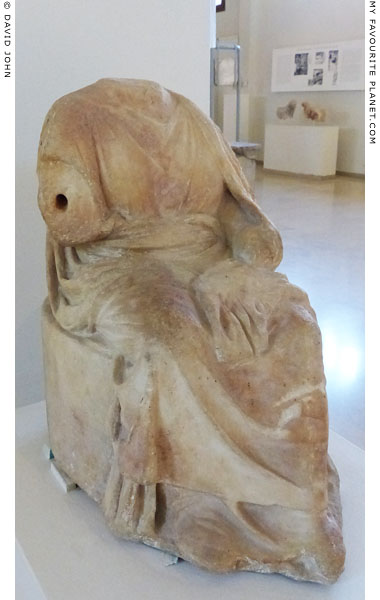

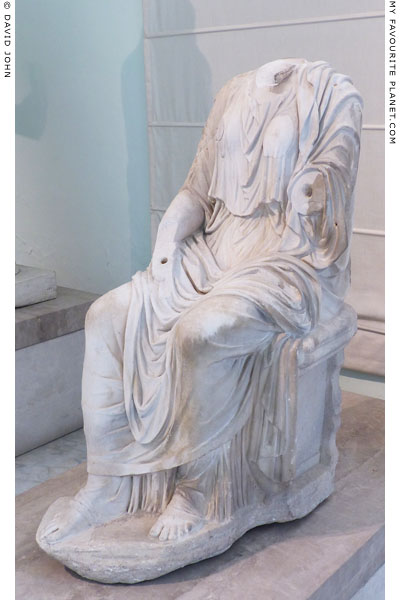

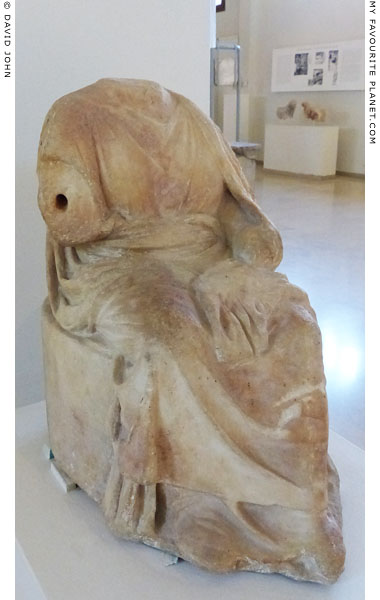

Headless marble statuette of Demeter sitting

on the sacred kiste (cista mystica), the chest

in which the sacred cult objects were kept.

From the Sanctuary of Isis, Dion.

Late 4th century BC.

Dion Archaeological Museum. |

|

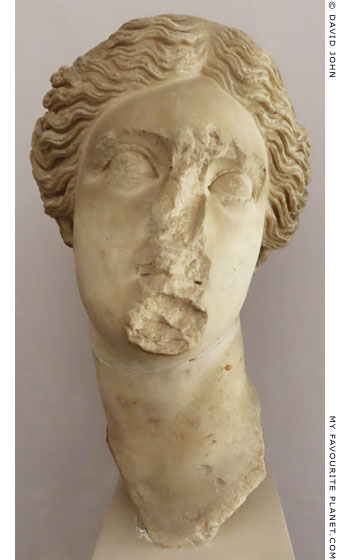

Headless marble statuette of Demeter sitting on the sacred

kiste. Found in the Ancient Agora, Athens. Probably from the

City Eleusinion (see part 1). The gooddess is wrapped in a

himation (cloak) over a chiton (tunic). In her left hand, which

rests on her lap, she holds a poppy and ears of corn.

Roman period copy of an original of the first

half of the 4th century BC. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3989. |

|

| |

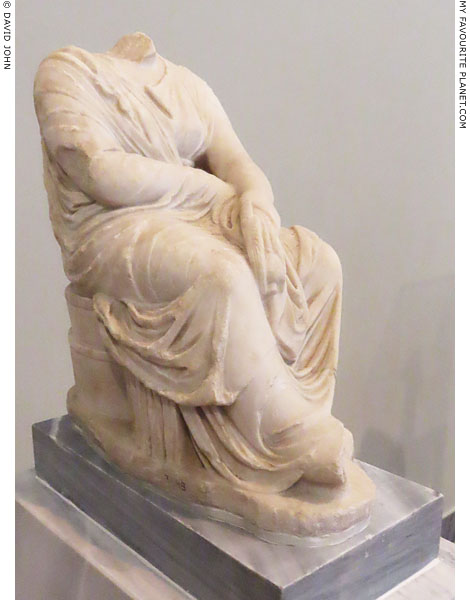

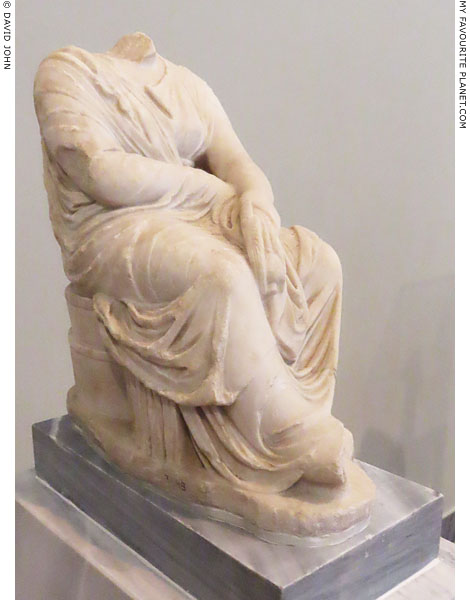

Headless, larger than lifesize marble statue

of Demeter or Kybele enthroned.

Early 1st century BC. Found in Kephalos.

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

|

The so-called Ceres, a marble statue of an

enthroned goddess. End of the 1st century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6263. Farnese Collection. |

|

| |

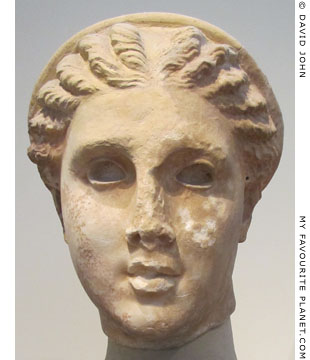

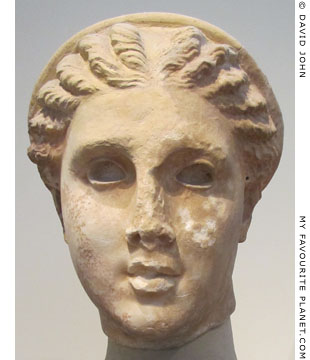

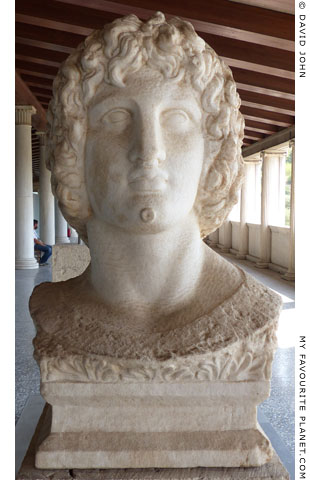

Colossal marble head from a statue of Demeter.

Antonine era (138-161 AD) copy of a 2nd century BC Hellenistic original.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Formerly in the house of Mayor Nikolaides. |

| |

|

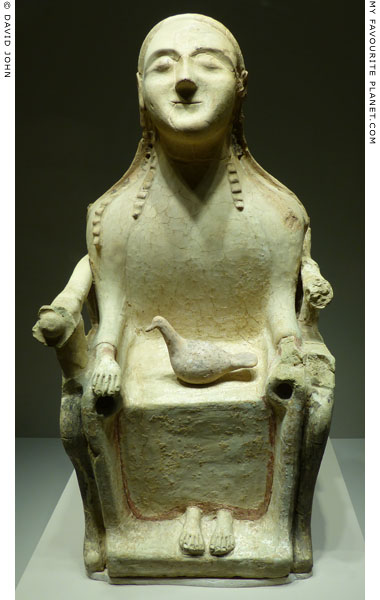

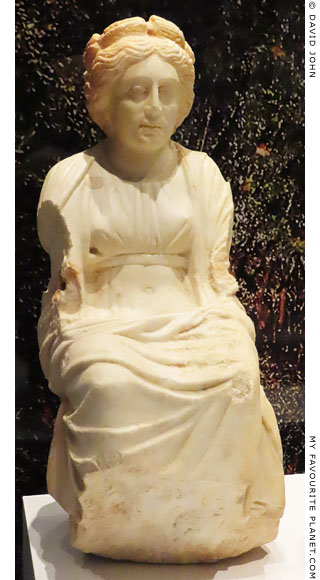

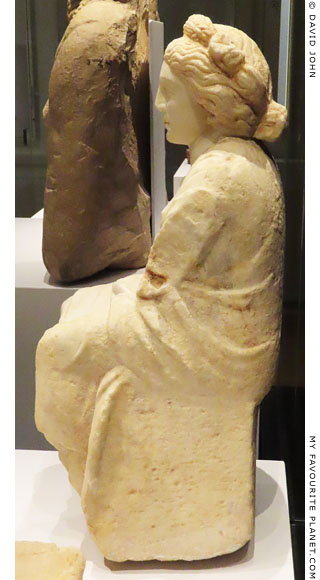

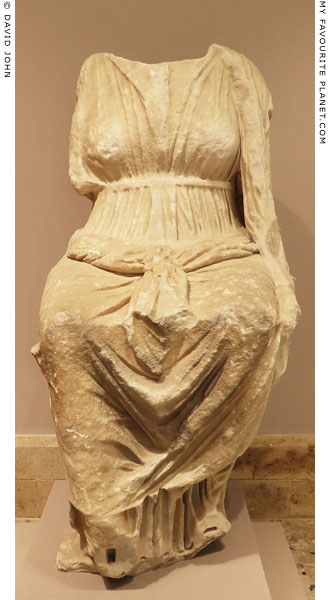

A marble statuette of seated Demeter.

Found in the "Villa of Theseus", Nea Paphos, southwestern Cyprus. 100-300 AD.

Paphos Archaeological Museum, Cyprus.

Exhibited in the exhibition Cyprus - Eiland in beweging (Cyprus - a dynamic island),

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands, 11 October 2019 - 15 March 2020.

|

The head was found by Polish archaeologists in Room 18 of the large Roman period palace or villa known as the "Villa of Theseus" in Nea Paphos (Πάφος), during excavations there in 1966-1967. It was matched with the rest of the statuette which had been found in the area before the excavations. The function of Room 18 and adjoining rooms is unknown, but they may have been used for cult practices.

Named after a floor mosaic with a depiction of Theseus in the Cretan Labyrinth, the villa has become well-known for its mosaics. However, a large number of statues of deities and mythical heroes were also discovered in various rooms. Two other statuettes, perhaps depicting Demeter and Persephone, were also discovered in Room 18 (see below).

This small figure depicts a female, apparently in middle age, wearing a crown, probably of corn, a long chiton (tunic) girdled just below the breast, and a himation (cloak) over her shoulders and back. Her wavy hair is parted in the middle and tied in a bun at the back. The arms, lower legs and feet are now missing. Presumably she originally held one or more objects, perhaps as attributes of the goddess. The statuette may have originally been placed in a niche (although no remains of alcoves have yet been discovered in the room) and designed to be viewed from the front. Her seat is merely a block with no carved details, but may represent the sacred kiste (cista mystica).

See: Panayiotis Panayides, Villa of Theseus, Nea Paphos: Reconsidering its sculptural collection. In: Richard Maguire and Jane Chick (editors), Approaching Cyprus, Proceedings of the Post-Graduate Conference of Cypriot Archaeology (PoCA), University of East Anglia, 1st - 3rd November 2013, chapter 14, pages 228-243, particularly pages 231-234. Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2016. At academia.edu.

The article includes a plan of the Villa of Theseus showing findspots of individual sculptures (with photos) and a bibliography. It provides a good introduction to Hellenistic and Roman period statues from Cyprus and a starting point for discovering further information about a subject rarely dealt with in depth. Unfortunately, there is very little detailed literature on the subject online.

There appears also to be very little current information about the cult of Demeter and Persephone on Cyprus, and few mentions in ancient literature. Grain-harvesting on Cyprus was known as damatrizein (δαματρίζειν).

In Metamorphoses the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BC - 17/18 AD) described the festival of first fruits (the Thesmophoria) in Cyprus as a poetic backdrop to his retelling of the mythical tale of the incestuous liaison between Cinyras, king of Paphos (Cyprus), and his daughter Myrrha, during which Adonis was conceived. In Ovid's version, the story is recited by Orpheus, who relates that the "sinful act" occurred while Cinyras' wife Cenchreis was attending the festival, during which women participants abstained from sex:

"The married women were celebrating that annual festival of Ceres, when, with their bodies veiled in white robes, they offer the first fruits of the harvest, wreathes of corn, and, for nine nights, treat sexual union, and the touch of a man, as forbidden. Cenchreis, the king’s wife was among the crowd, frequenting the sacred rites."

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 10, lines 431-502. Translated by Anthony S. Kline, 2000. At the Ovid Collection, University of Virginia. |

|

| |

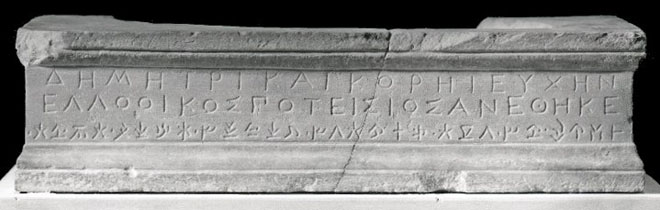

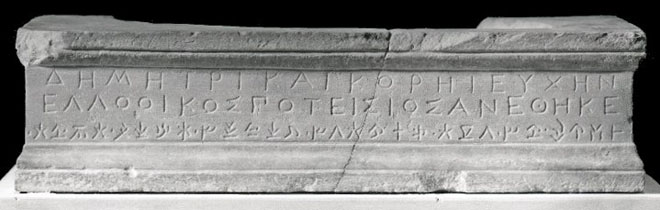

A marble statuette base excavated at Kourion, Cyprus inscribed with an ex-voto dedication

to Demeter and Persephone in Greek and Cypro-syllabic script. The findspot, north of the

acropolis, known as "Site C" or "Temple Site", may have been a rural sanctuary of Demeter.

Around 350-300BC. Found in April 1895 during the British Museum Turner Bequest

excavations at Kourion (Κούριον; Latin, Curium; modern Episkopi, Επισκοπή)

on the south coast of Cyprus. Height 7 cm, length, 28 cm, depth 16.5 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1896,0201.215. Inscription 968.a. Acquired in 1896.

Photo © the Trustees of the British Museum. |

| |

The Greek inscription:

Δήμητρι καὶ Κόρηι εὐχὴν

Ἑλλόοικος Ποτείσιος ἀνέθηκε

Transliteration of the text in Cypro-syllabic script, on a single line with dots between the words:

ta-ma-ti-ri · ka-se · ko-ra-i · e-lo-wo-i-ko-se ·

po-te-si-o-se · a-ne-te-ke · i-tu-ka-i

To Demeter and Kore, Helloikos the son of Poteisis dedicated this as a vow.

Inscription I.Kourion 26 (also ICS² 182)

at The Packard Humanities Institute.

See:

research.britishmuseum.org/...

(British Museum Collection Online)

F. H. Marshall, The collection of ancient Greek inscriptions in the British Museum, Part IV, section II: Supplementary and miscellaneous inscriptions, No. DCCCCLXVIIIA (968 a), page 130. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1916.

The dating of the inscription to the second half of the 4th century BC is based on the style of the Greek lettering.

During the same excavation fragments of marble statues and a large number of terracotta figurines of male and female votaries, horse-riders and charioteers were also discovered at the site. The finds date from the 4th century BC to the end of the Hellenistic period. Coins found also dated to these periods but include Imperial and Late Roman types.

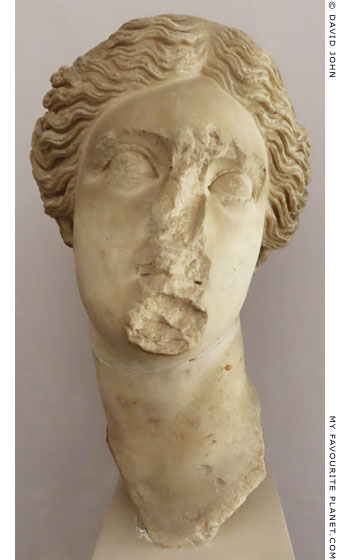

A fragment of a smaller than lifesize marble head (see photo, right) was believed by the excavators to be part of a statue which stood on the base, but was recorded as a representation of "Aphrodite (Knidian type)". Somehow it ended up being registered by the museum with marble heads from Ephesus in 1972, but in 2009 it was identified as the head from Kourion by Dr Peter Higgs, who believed it to be a Hellenistic portrait, probably of the 2nd century BC.

If Dr Higgs' belief is correct, and if the excavators were right in claiming the head belonged to the base, it raises a number of questions concerning the identity of goddess or person depicted, the date of the inscription and the survival of the Cypro-syllabic writing system into the Hellenistic period.

See: research.britishmuseum.org/... |

|

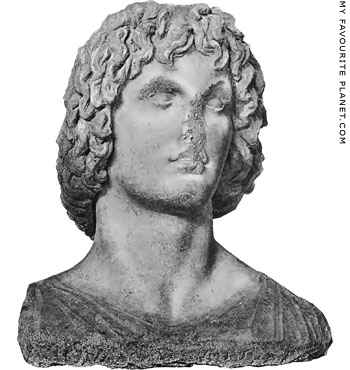

The marble head found with

the statue base at Kourion.

2nd century BC (?).

Height 18.8 cm.

British Museum.

Inv. No. 1972,0118.1.

Photo © the Trustees

of the British Museum. |

|

| |

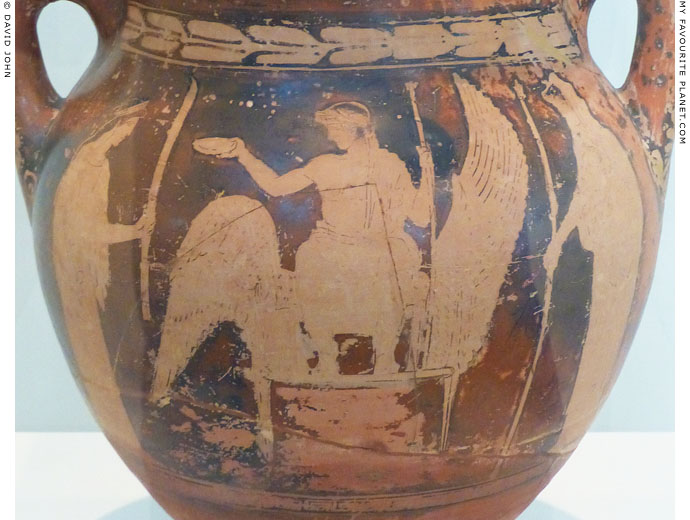

A relief of Demeter sitting on the sacred kiste on the side of a cylindrical

marble altar depicting the Dodekatheon, the twelve Olympian gods

(see the note on the twelve gods on the Dionysus page).

1st century BC - 1st century AD. Discovered in May 1940 during excavations

by Guido Calza (1888-1946) at the temple of Attis in the sanctuary of the

Magna Mater (Campo della Magna Mater, Regio IV, Insula I), Ostia,

near Rome. Pentelic marble. Height 44 cm, diameter 50 cm.

Ostia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 120.

|

One of the fragments, previously kept in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme of the National Museum of Rome, had probably been discovered in 1867, during excavations at the sanctuary of the Magna Mater by Carlo Lodovico Visconti (1818-1894).

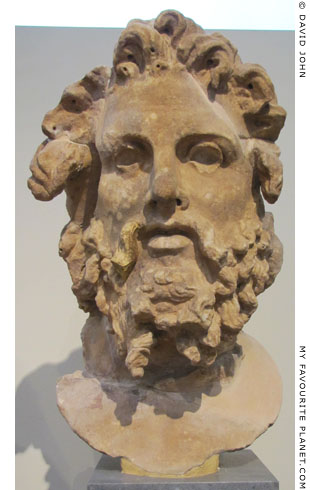

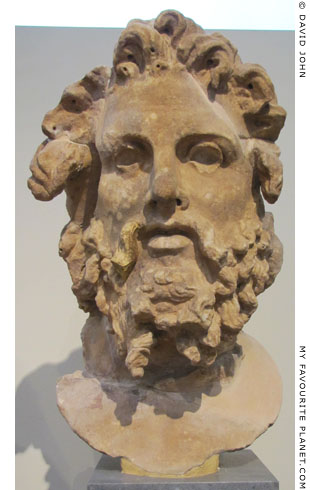

The altar is thought to be a Neo-Attic work, made in Athens between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD. On the front of the altar Zeus sits on a throne facing right, and above him is the inscription Δωδεκάθεον (Dodekatheon, "of the twelve gods").

The work may be eclectic, with the figures sculpted in imitation of a number of Greek sculptors of various periods. It has been suggested that as many as five of the figures, including Zeus, may be copies of those on the frieze on the east pediment of the Parthenon (see below). There has been little debate about the iconography of the relief or the identity of the deities.

The figures in the photo above are to the left and behind Zeus. The seated goddess has also been interpreted as Hestia (῾Εστία, goddess of the hearth), but the objects in her right hand appear to be ears of corn, with her left hand she holds her veil as in other depictions of Demeter (see above and below), and sits on a cylindrical object which may be the sacred kiste (see above).

Left of her is Hermes, naked except for a chlamys cloak, and with a petasos hat behind his head. On the right stands Apollo, holding a kithara (lyre), and to the right of him is his sister Artemis.

The first examination of the relief was written by the Italian archaeologist and art historian Giovanni Becatti (1912-1973), published in 1942 [4]. It had been compared to that on a marble puteal (well head) in the Madrid Archaeological Museum, depicting gods around enthroned Zeus at the birth of Athena (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 13), which in turn had been connected with the scene as depicted on the east pediment of the Parthenon. However, rejecting this connection, Becatti believed that eleven of the twelve figures on the altar were copied from statues of the Olympian gods by Praxiteles which stood in the sanctuary of Artemis Soteira (Artemis Saviour) in Megara, central Greece. No traces of these works have yet been discovered by archaeologists, and the only ancient source concerning the group is a brief mention by Pausanias, who did not describe the statues, merely reporting the claim of his local informants that they were "said to be" by Praxiteles:

"... For this reason they had an image made of Artemis Saviour. Here are also images of the gods named the Twelve, said to be the work of Praxiteles. But the image of Artemis herself was made by Strongylion."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 40, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

In an article published in 1949, the American classical art historian Rhys Carpenter (1889-1980) examined Becatti's claim that eleven of the figures were Praxitelean, and concluded: "Unfortunately, it seems to me to be entirely certain that they are not." [5] Instead, he saw characteristics of works by sculptors such as Lysippos and Polykleitos in some of the figures, and preferred to look to the Parthenon relief as a model.

The gods on the altar were identified by Becatti as:

1. Athena, 2. Zeus, 3. Hera, 4. Demeter or Amphitrite,

5. Poseidon, 6. Aphrodite, 7. Ares, 8. Hephaistos,

9. Hermes, 10. Hestia, 11. Apollo, 12. Artemis.

See a drawing of the relief below.

However, some of the identifications have been made on thin grounds. Becatti thought that the faceless figure 4 (see photo, above right) may be either Demeter or the Nereid Amphitrite (Ἀμφιτρίτη), the consort of Poseidon, because she stands next to the sea god, despite the fact that she is not counted among the twelve Olympian gods. Although Demeter stands next to Poseidon in a relief from Smyrna (see below), it is a very different type of work; Poseidon is seated, and Artemis stands to his right. Figure 4 can not definitely be identified as Demeter on the basis of iconography or attributes: whatever she may have been holding in her raised right hand is now missing; her clothing and pose can be ascribed to depictions of other goddesses; and there is no standard relative positioning of the gods in other comparable groups [6].

Figure 10 has been identified as Hestia, in part by comparison with the female sitting on a rock on the Madrid puteal, who is thought to be Klotho (Κλωθώ, one of the three Moirai or Fates). It has also been suggested that the fact that Hermes stands next to the figure indicates she is Hestia, with whom he was sometimes associated, although the same can be said for Demeter (see below: here, here, here, here and here).

Very few Greek statues of Hestia are mentioned by ancient authors or inscriptions, and even fewer surviving sculptures are known with certainty to depict her. Even the famous "Giustiniani Hestia" (Torlonia Museum, Rome, Inv. No. MT 490) may actually be Demeter or Hera. There are none that can be directly compared with this figure.

Still, one would expect to see Hestia among the twelve, although she was later replaced by Dionysus (who does not appear on the altar), particularly if the relief was made for a customer in Rome, where, as Vesta, she remained an important deity. However, given the scarcity of other sculptural depictions of her, there is no definitive type which would assist positive identification. |

|

Deity No. 4 on the Ostia

Dodekatheon relief,

traditionally identified

as Demeter or Amphitrite. |

|

| |

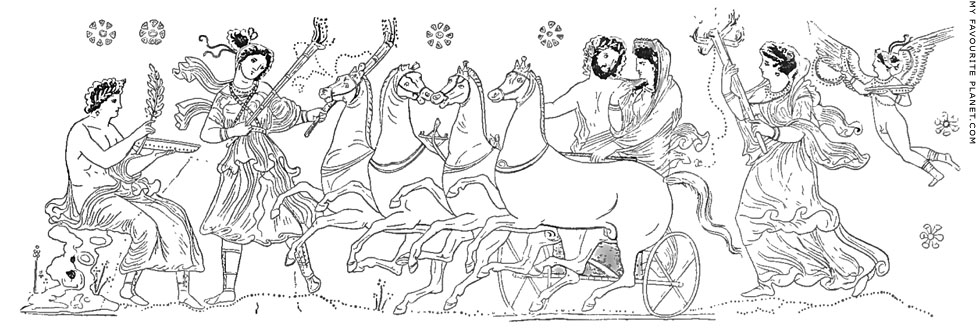

A drawing of the Dodekatheon relief in Ostia.

The gods are shown in a different order to that in Becatti's study. Left - right:

1. Hermes, 2. Hestia or Demeter (seated), 3. Apollo, 4. Artemis, 5. Athena,

6. Zeus (enthroned), 7. Hera, 8. Demeter, Hestia or Amphitrite,

9. Poseidon, 10. Aphrodite, 11. Ares, 12. Hephaistos. |

| |

The remains of a marble cylindrical altar with a relief of the Dodekatheon, the twelve

Olympian gods, around its sides. The gods visible in the above photo (left-right):

Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Zeus. Demeter sits on the sacred kiste, facing right,

holding a sceptre in her left hand and ears of wheat in the right.

Around 350-340 BC. Found in 1877 north of the Stoa of Attalos in

the Ancient Agora, Athens. Pentelic marble. Height approx. 44 cm..

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1731.

|

The broken part of the altar has been restored with plaster, but only seven gods and part of an eighth have been preserved. They have been identified as (left-right):

1) Hestia, facing right, holding her veil with her left hand; 2) Poseidon sitting on a rock, facing left, holding a trident in his raised left hand; 3) Demeter sitting on the sacred kiste, facing right, holding a sceptre in her left hand and ears of wheat in the right; 4) Athena standing, facing left, wearing the aegis over a peplos; 5) Zeus enthroned, facing right, holding a sceptre in his right hand; 6) Hera, facing left, pulling at an edge of her veil with her right hand; 7) Apollo sits, facing right, holding a kithara in his left hand and a plectrum in the right; 8) part of another god, now unidentifiable. |

|

|

Demeter shown seated and holding a long torch, with ears of corn in her hand and hair,

on the side of the "Lovatelli Urn" (Urna Lovatelli), a marble cinerary urn with a low relief

depicting the initiation of Herakles into the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Fine-grained white marble. Early Imperial period, inspired by a late Hellenistic model

from Alexandria, Egypt. Found in the columbarium, the burial ground of the freed slaves

and servants of the gens Statilia, on the Esquiline Hill near the Porta Maggiore, Rome.

Height 29.4 cm, maximum diameter 32.0 cm. Height of figures 22.0 cm.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 11301.

|

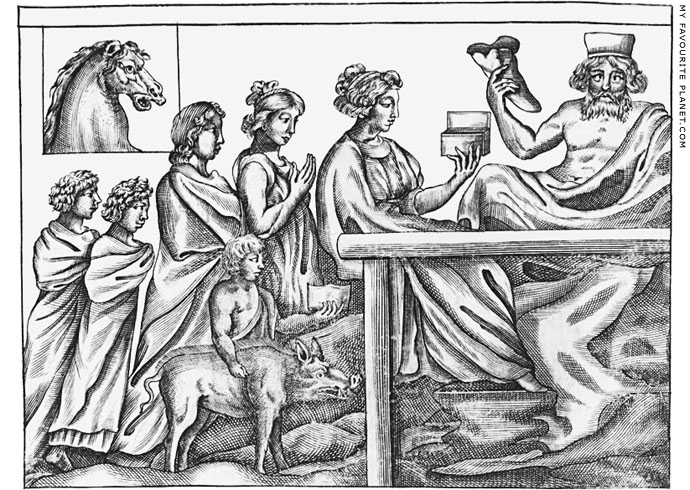

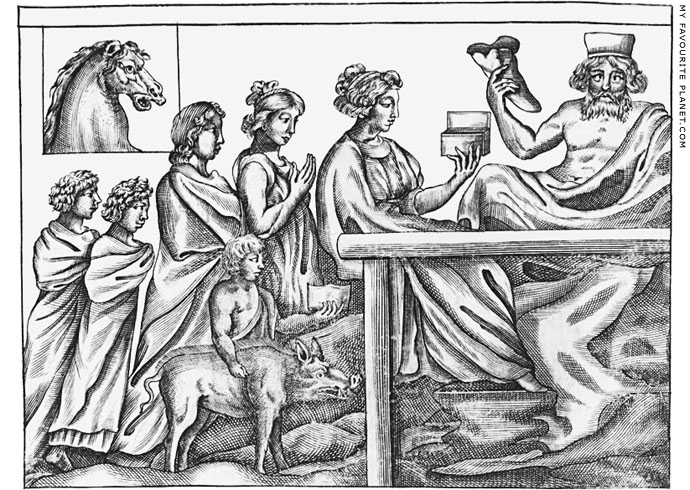

The "Lovatelli Urn" (Urna Lovatelli) was named after Ersilia Caetani Lovatelli (1840-1925) who first published details of the vessel in the article: Di un vaso cinerario con rappresentanze relative aimisteri de Eleusi. In: Bullettino della Commissione archaeologica comunale di Roma 7, 1879, pages 5-18.

The side of the finely sculpted urn is decorated all around with narrative scenes concerning the initiation of Herakles into the Eleusinian Mysteries (see drawing below). To the left of the main scene Demeter is shown seated and holding a long torch, with ears of corn in her hand and hair. The god Iakchos stands in front of her, touching the head (or feeding) a snake in her lap. Demeter turns her head to see Persephone (Kore) approaching from behind.

In the main scene the initiate Herakles sits with a lionskin covering his head and shoulders, while a priestess holds a wicker screen (liknon) above his head. To the right a hierophant (priest), holding a bowl and a jug, accepts the sacrificing of a piglet, placed on a low altar by a male figure (also Herakles?).

Unfortunately, the urn is displayed near a wall and it is difficult to view the side scenes which are unlit. |

|

| |

A "roll-out" drawing of the relief around the side of the "Lovatelli Urn" (Urna Lovatelli).

Image source: Ersilia Caetani Lovatelli, Antichi monumenti illustrati, Tavelo III.

Tip. della R. Accad. dei Lincei, Rome, 1889. At Arachne, University of Cologne. |

| |

Terracotta statuette of Demeter

veiled and holding a long torch.

Roman period, 1st - 2nd century AD.

From Egypt. Provenance unknown.

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan.

Inv. No. E 1998.03.451.

Temporary exhibition: Milano in Egitto:

Gli scavi di Achille Vogliano nel Fayum

(Milan in Egypt: The excavations of Achille

Vogliano in Fayum), Civic Archaeological

Museum, Milan, 17 May - 15 December 2017,

extended until 13 May 2018. |

|

|

|

| |

Fragmentary marble stele with high reliefs of Artemis, Poseidon and Demeter.

Only the lower torso and legs of Artemis have survived.

Discovered in the Agora of Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey) during excavations

by German and Turkish archaeologists 1932-1941. Believed to have

been part of a group of deities on an altar to Zeus in the centre of the

agora. Antonine period (138-193 AD). Height 220 cm, width 270 cm.

Izmir Museum of History and Art. |

| |

The Demeter relief from the Smyrna agora.

Izmir Museum of History and Art. |

|

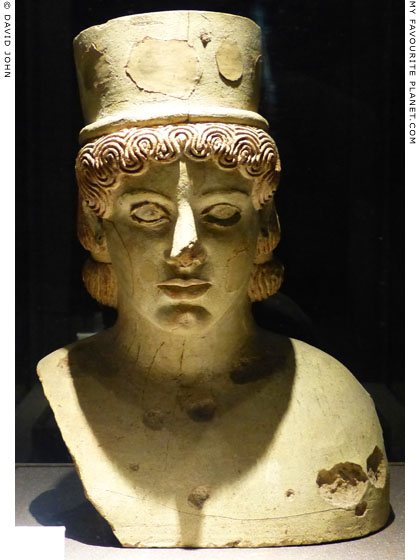

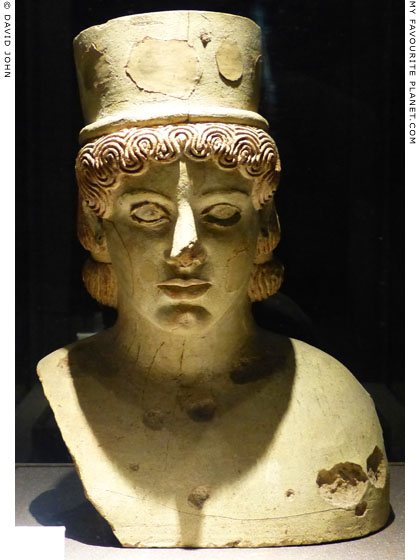

Ceramic bust of Demeter wearing a polos. 5th century BC.

Museo Civico, Castello Ursino, Catania, Sicily.

Inv. No. 5685. From the Biscari Collection. |

| |

One of the larger and finer terracotta votive busts of a goddess wearing a polos,

probably Demeter or Persephone, from the cave sanctuary, known as "Demeter's

Holy Cave", Agrigento (ancient Akragas, Ἀκράγας), southern Sicily.

Late 5th - early 4th century BC.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse. Inv. No. 16085.

|

There are holes in the earlobes for earrings and she wears a necklace with pendants. Below the polos is a headband tied at the front with a Herakles knot, a feature of several similar busts and statuettes from Sicily (see photos below). Also typical of this type of figure is the hairstyle: parted in the middle, the hair is swept up and back from around the face; sometimes as here, grown to below the nape of the neck, sometimes shoulder-length. In this case there are also plaits falling from behind the ears to the shoulders, as seen also on deptions of other gods such as Artemis, Apollo, Dionysus and Hermes.

See also the bust from Syracuse in Demeter and Persephone part 1. |

|

| |

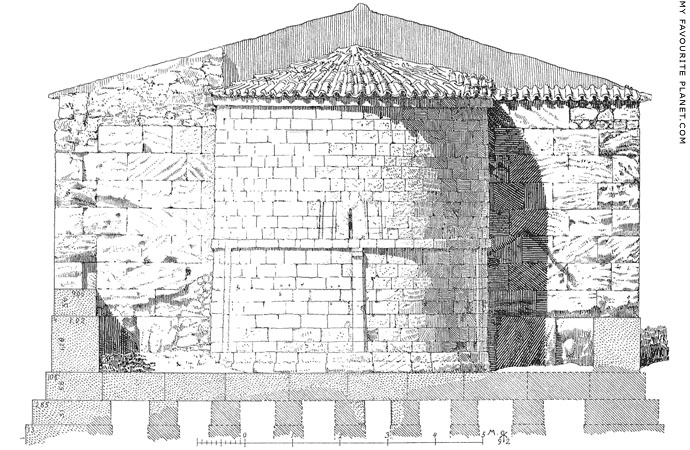

One of several busts (see photos below) of various sizes and other terracotta votive offerings from the cave sanctuary known as "Demeter's Holy Cave" or San Biagio's cave sanctuary, on the cliff-face outside the city wall at the east of Agrigento. The sanctuary may have been founded by native Sicilians before the arrival of the Rhodian and Cretan Greek colonizers from Gela, further east along the south coast of Sicily, around 582-580 BC (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 6, chapter 4), and was in use until the sack of the city by the Carthaginians in 406 BC.

Above this sanctuary, on the top of the cliff, stood the temple of Demeter and Persephone, built 479-472 BC by Theron (Θήρων), the tyrant of Akragas, as part of a building programme following the Greek defeat of the Carthaginian invasion at Himera in 480 BC. The foundations and lower walls of the Doric temple, 13.3 x 30.2 metres, can still be seen beneath the Norman church of San Biagio (see image below), built in the 12th or 13th century with stone from the ancient building. The eastern hill of the Akragas acropolis, known as the Rupe Atenea (Rock of Athena), was also the location of temples of Athena and Zeus Atabyrios (Διὸς Ἀταβυρίος), whose cult was brought from Rhodes by the founders of Gela (Polybius, Histories, Book 9, chapter 27).

The cult of Demeter and Persephone at Akragas (Ἀκράγας) was referred to by the Theban poet Pindar (Πίνδαρος, circa 522-443 BC) at the beginning of one of his odes for a victor at the Pythian Games in Delphi. He wrote that the city, which was named after ther River Akragas, was the abode of Persephone (here written Φερσεφόνας, Fersefonas):

"I beseech you, splendour-loving city, most beautiful on earth, home of Persephone; you who inhabit the hill of well-built dwellings above the banks of sheep-pasturing Akragas: be propitious, and with the goodwill of gods and men, mistress, receive this victory garland from Pytho in honor of renowned Midas, and receive the victor himself, champion of Hellas in that art which once Pallas Athena discovered..." [7]

Pindar, Pythian 12, For Midas of Acragas, winner of the aulos-playing contest, 494 or 490 BC. At Perseus Digital Library.

The cave sanctuary, discovered by chance in the late 19th century, consists of a monumental fountain-reservoir in front of a rock face into which three tunnels had been dug. Two of the tunnels carried water to the city's water supply network, known as "dei Feaci" (of the Phaeacians), dated to the 5th century BC. It is thought that the local water deity Persephone-Nestis, mentioned by the philosopher Empedocles who lived in Akragas, may have been worshipped here.

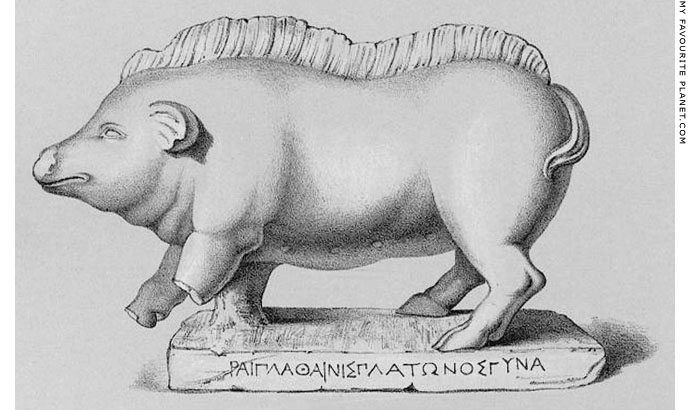

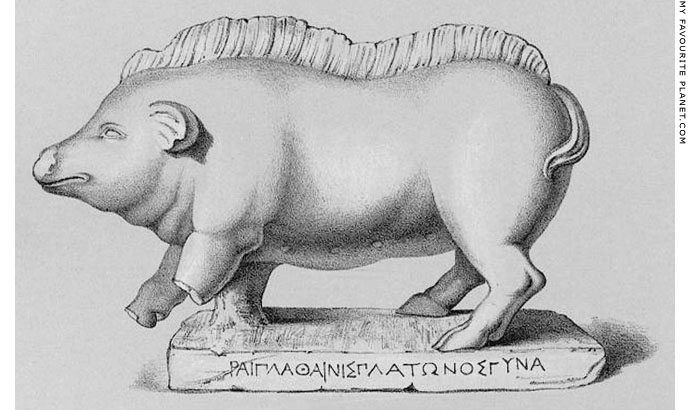

Among the many objects found, dated to between the 8th or 7th and 4th centuries BC, were Geometric and Proto-Corinthian pottery, oil lamps, libation bowls, jugs and wine cups (skyphoi), "piglet offering figures" connected with propitiatory fertility rituals (see photo right) and ceramic sculptures, mostly depicting females, perhaps Demeter and Kore.

The sanctuary was first investigated by Pirro Marconi in 1926, by which time a great number of artefacts had already been looted and sold on the black market, and many smuggled out of Sicily. Some found their way to museums of Agrigento, Palermo and Siracusa. The objects in this group had been dug up by "grave robbers" and sold to antiquities smugglers, but were for some reason delivered in boxes to the Palermo museum on Christmas 1888.

Demeter is also thought to have been one of the deities worshipped in the Sanctuary of the Chthonic Divinities in the Valley of the Temples, below and to the southwest of the city. Although it it not known which deities were worshipped there (perhaps the Dioskouroi), the site contained bothroi (sacrificial pits), and terracotta figurines discovered there are almost identical to those found at other sanctuaries of Demeter in Sicily. |

One of the piglet offering figures

from "Demeter's Holy Cave" in

Agrigento. A terracotta figurine of

a female holding a sacrificial piglet.

Antonino Salinas Regional

Archaeological Museum,

Palermo, Sicily.

See other piglet-offering figures

associated with Demeter and

Persephone below and in part 1. |

| |

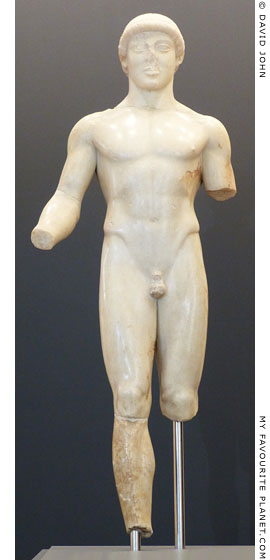

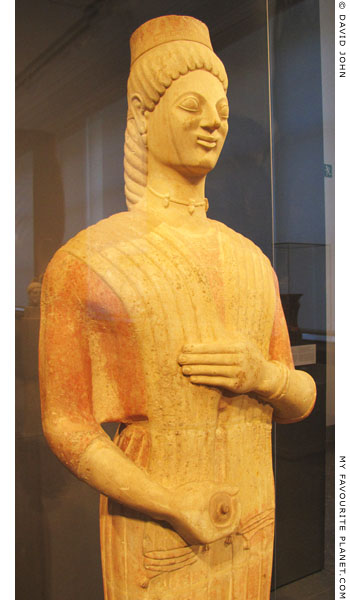

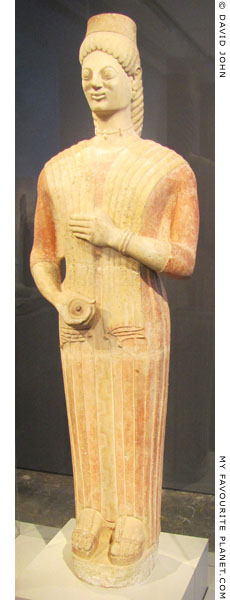

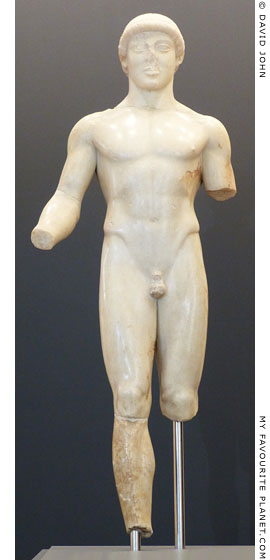

A smaller than life-size marble kouros

statue, found in 1897 in a cistern near

the temple of Demeter and Persephone

on the Rupe Atenea, Agrigento. The

figure, which may have been a votive

offering to the goddesses, has been

compared with the "Kritios Boy"

kouros found on the Athens Acropolis.

Around 480 BC.

Pietro Griffo Regional Archaeological

Museum, Agrigento. |

| |

| |

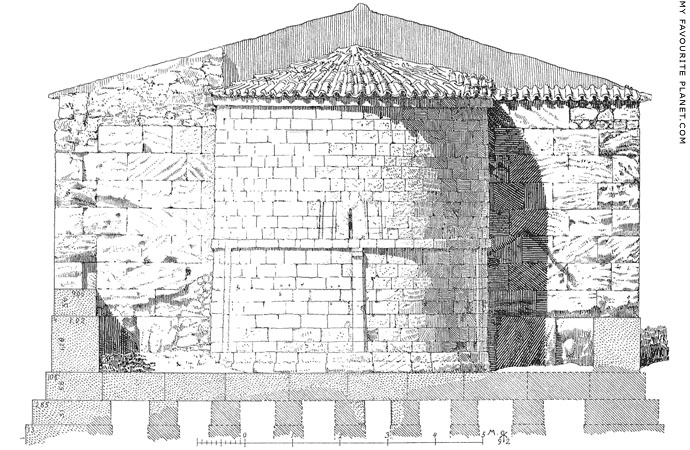

A drawing of the east side of San Biagio church in Agrigento, Sicily.

Source: Robert Koldewey and Otto Puchstein, Die griechischen

Tempel in Unteritalien und Sicilien, Band 1, Abbildung 128, page 143.

A. Ascher & Co., Berlin, 1899. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

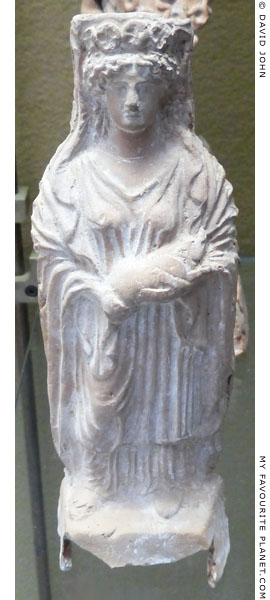

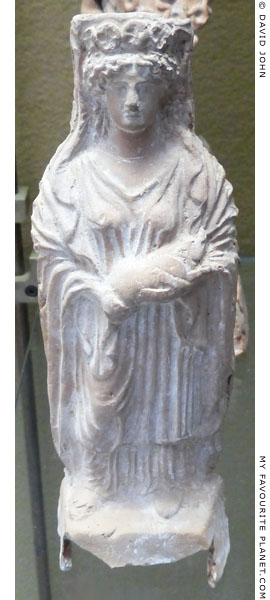

Terracotta votive bust of Demeter or Persephone wearing a polos.

5th - 4th century BC. From Agrigento (ancient Akragas), Sicily.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily. |

| |

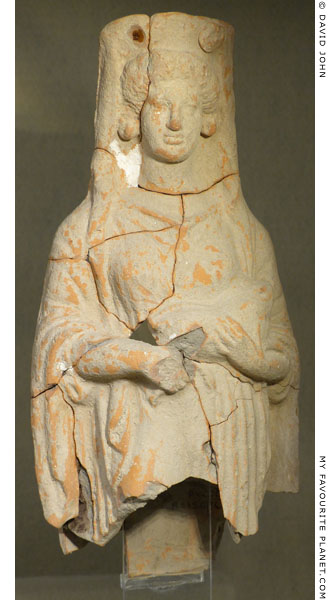

A terracotta votive bust of Demeter or Persephone

from "Demeter's Holy Cave", Agrigento.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily. |

| |

Terracotta figurines of a goddess wearing a polos and holding a piglet,

known as piglet offering figures, from various deposits in the sanctuary

of Demeter and Kore at Kamarina (Καμάρινα), on the south coast of Sicily.

5th - 4th centuries BC.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse.

Inv. Nos. 16347, 16344, 2293, 2294, 1949, 16342, 18475.

Only 7 Invoice Numbers are given on the museum label for the group of

8 figures displayed together, and it is not possible to tell which is which.

|

| The ruins of Kamarina (Καμάρινα) are near the eastern end of the south coast of Sicily, 16 km southwest of modern Vittoria. Like all ancient Sicilian cities it had a tumultuous history. It was founded in 599 BC by Syracuse, which destroyed it in 552 BC. Refounded by Gela in 461 BC, it was sacked by the Carthaginians in 405 BC. Timoleon (see part 1) restored it once again in 339 BC, and in 258 BC it was taken by the Romans. Its final destruction came in 853 AD. |

|

| |

Terracotta figurine of a goddess wearing

a polos and holding a sacrificial piglet.

4th century BC. From the city of

Megara Hyblaia (Μέγαρα Ὑβλαία), Sicily.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological

Museum, Syracuse. Inv. No. 1104. |

|

Terracotta figurine of a goddess wearing

a polos and holding a sacrificial piglet.

From Syracuse (?)

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological

Museum, Syracuse. Unlabelled. |

|

| |

Terracotta bust of Demeter or Persephone holding a torch and a pig.

Made in Taranto, Italy around 420-400 BC. From Rubi.

British Museum. Gr 1856.12-26.325 (Terracotta 1276).

Bequeathed by Sir William Temple. |

| |

Terracotta figurines of a goddess wearing a polos

and holding a liknon (see part 1) in her left hand.

From Syracuse (?)

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse. Unlabelled. |

| |

A terracotta oil lamp with a relief of Ceres standing in the central

tondo, holding an ear of wheat in her right hand. Around the outside

of the tondo are reliefs of bunches of grapes and vine leaves.

Circa 2nd century AD. From Tunisia.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 12.534. |

| |

A painting of a Roman fertility goddess, either Tellus (Terra) or Ceres, on the side of

a plaster-covered stone altar. Below is a black marble head of Dionysus/Bacchus.

From the Roman city Mediolanum (Milan), late 1st - early 2nd century AD.

Found in 1825 in the Via Circo, Milan.

Probably from a domus extra moenia, outside the city walls, perhaps from a collegium

(corporation of craftsmen or merchants). Each of the four sides has a painting of a deity.

The other three sides show Fortuna-Abundantia, Hercules and Nike/Victoria.

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan. Inv. No. E 0.9.1070. |

| |

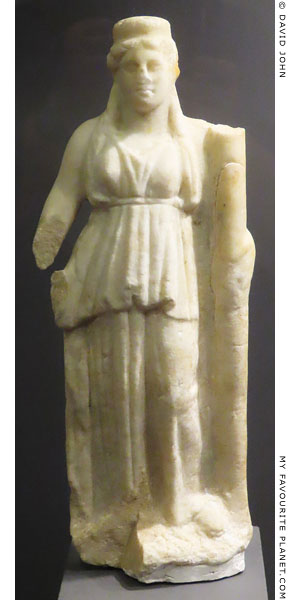

A marble statuette of a goddess,

perhaps Demeter, wearing a polos

and holding a long torch.

1st century AD. Found in the sanctuary

of Demeter in the city of Rhodes.

Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes.

|

|

A ceramic figurine of a young female

(Kore?) draped in a himation (cloak),

holding a tray of fruits.

4th century BC. Found in the sanctuary

of Demeter in the city of Rhodes.

Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes.

|

|

Both objects were found in the 1980s during a rescue excavation at the northeast end of the city of Rhodes (at the northern tip of the island), in what is now the New Town, near the ancient city walls. The excavation was concentrated on the Karayannis-Georgiadis properties at the junction of Kaouli Street and Amerikis Street, an area now occupied by hotels, near the National Theatre, and around 50 metres from the Hellenistic wall.

Only part of the extensive ancient sanctuary discovered there could be excavated, as the rest lies beneath modern buildings. A bronze ladle inscribed with a dedication to Demeter (see photo below) and several other finds of votive objects typical of the worship of Demeter and Persephone at other locations in East Greece (Troy, Pergamon, Priene, Kos and Lindos) convinced the archaeologists that this sanctuary was dedicated to these goddesses.

The finds included figurines thought represent of the Kore (Persephone), as well as worshippers carrying pigs (choirophoroi), water (hydrophoroi) and children (kourotrophoi). There were also hundreds of miniature olpae (jugs) and around three thousand oil lamps (see photo below). No temple has been found, and it has been suggested that the sanctuary may have been a thesmophorion (see part 1).

Remains were found of rectangular structures, three of which were not in alignment with the ancient street grid designed on the urban planning principles of Hippodamus of Miletus (although he probably did not take part in the design of Rhodes) when the city was founded in 408 BC. It is thought that the sanctuary was probably in use from the city's foundation until the early 2nd century BC.

The finds from the sanctuary are part of the collection of the Rhodes Archaeological Museum, but a few are currently (2022) part of the extended exhibition "Ancient Rhodes - 2400 years", in the Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes.

As with much of the archaeological activity on Rhodes since the 19th century, very little information about the excavation of the sanctuary of Demeter has been published.

Prior to the discovery of this sanctuary, very little evidence had been found for the civic worship of Demeter on the island. More particularly, no inscriptions mention priests of the goddess, leading to the suggestion that her cult may have been led here by women who were not mentioned in the epigraphic records.

See, for example: Juliane Zachhuber, The lost priestesses of Rhodes? Female religious offices and social standing in Hellenistic Rhodes. In: Kernos, issue 31, 2018, pages 83-110. At OpenEdition Journals. |

|

| |

A bronze ladle with a handle ending in the head of a duck, and on the back a

dedication to Demeter has been inscribed in lettering formed by series of dots.

ΧΑΙΡΙΩΝ ... ΔΑΜAΤΡΙ

Chairion [dedicated] to Demeter

4th century BC. Found in the sanctuary

of Demeter in the city of Rhodes.

Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes. |

| |

A display case with archaeological finds from Rhodes: ceramic figurines, lamps

and vases. The assembly is not labelled, and it is not clear if these are finds

from the sanctuary of Demeter, from some other dig, or a general display.

Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes. |

| |

|

|

|

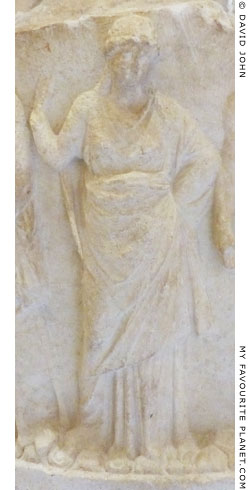

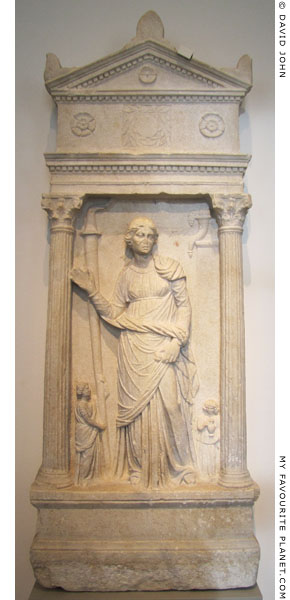

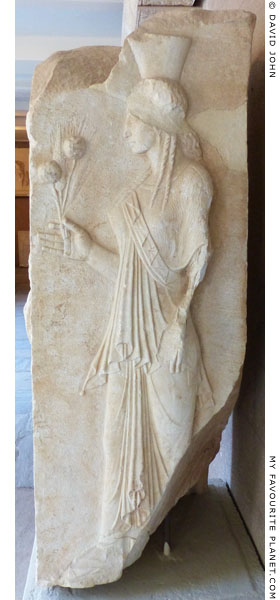

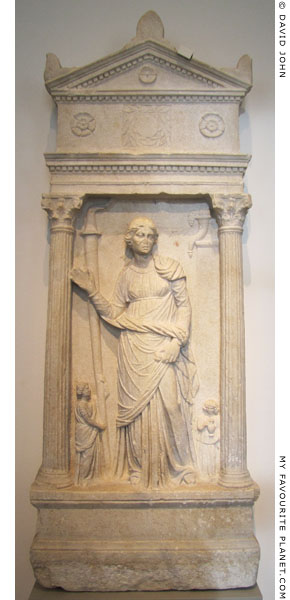

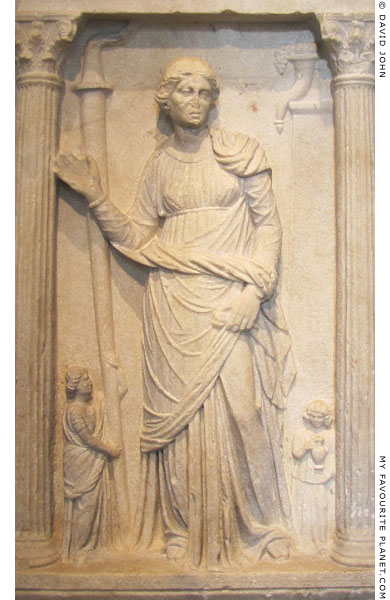

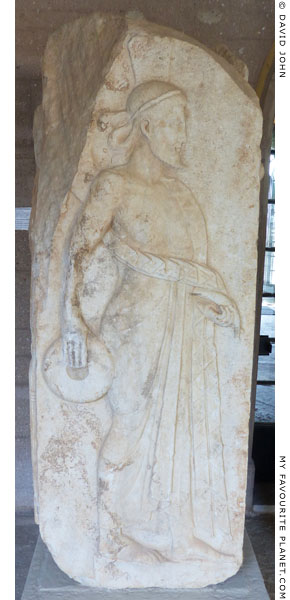

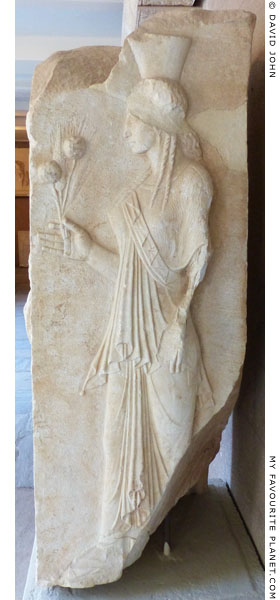

Marble funerary stele with a relief of a woman, perhaps a priestess of Demeter.

Found at the caravan bridge at Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey). Hellenistic period,

around 150-100 BC. Coarse-grained, blue-greyish white marble.

Height 155 cm, width 65 cm, depth 14 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 767. Acquired in 1878.

|

|

| The woman holds poppy capsules in her left hand, and one of her diminuative female servants (slaves) holds a long torch. To the right, a cornucopia stands on top of a pilaster in lower relief. All three symbols are associated with the cult of Demeter and Persephone. However, this does not necessarily indicate that she was a priestess: the iconography, perhaps based on a statue of a prietess of Demeter, was common in Smyrna to depict respected women. The elaborate carving of the main figure and the architectural setting, complete with Corinthian columns and rosettes, suggest that she was from a wealthy family. |

|

| |

The rear of a Taurobolic altar with a relief of Demeter (left) and Cybele enthroned

next to each other. The goddesses are flanked by the Eleusinian deity Iakchos

(far left), holding a torch, and Persephone (far right) holding two torches.

387 AD, late Antiquity. From Attica. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1747.

One of two very similar altars exhibited in the museum. Unfortunately, they are displayed close to a wall, so that it is impossible to get a good look (or photo) of the back of the objects, which were designed to be admired in the round. The other altar, Inv. No. 1746, is dated around 360-370 AD, perhaps during the reign of Julian the Apostate (361-363 AD). It is thought that they are from Chalandri (ancient Phlya), Attica. They are associated with the cult of Cybele-Rhea, particularly with the mystery celebration of the Taurobolia.

Each altar has a relief on three sides and a dedicatory inscription on the fourth. The relief scenes include cult symbols or props, such as long torches, pan pipes, drums and castanets. On the front of each is a relief of enthroned Cybele-Rhea resting her right hand on the shoulder of Attis, who stands to her right. On the left side are crossed torches and symbols, and on the rear side is the group of Iakchos, Demeter, Cybele and Persephone.

The inscription on the fourth side of this altar states that it was dedicated by Mousonios as a symbol of the ceremony of the Taurobolion. According to calendar references mentioned, it has been estimated that the altar was set up on 27 May 387.

Altar 1746 was dedicated by Archelaos of Athens, torch-bearer of Persephone at Lerna and key-bearer of Hera, in return for his initiation into the Taurobolic Mysteries. He also claims to have been the first to celebrate the Taurobolia at that particular location. The inscriptions are indications that there was still interest in pagan eclectic mystery cults even after Chrisitanity had swept through the ancient world and become the de facto official religion of the Roman Empire. But cult devotees like Mousonios and Archelaos were fighting very much a rear-guard action, and shortly after these altars were set up pagan worship would be forbidden and the temples and sanctuaries of the ancient gods forced to close forever. |

|

| |

| |

Demeter on coins |

|

|

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin of Kyzikos (Cyzicus, Κύζικος) Mysia,

northwestern Anatolia (today Erdek, Balikesir Province, Turkey),

with the head of Demeter facing left, her hair held up by a sakkos

(headscarf), and wearing an earring in the form of an ear of wheat.

Above right is the inscription "ΣΩΤΕΙΡΑ" (Soteira, Saviour).

Circa 400 BC. Diameter 23 mm, weight 15.15 grams.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18200339. |

| |

A silver stater coin of Metapontion, Magna Graecia, with an

ear of corn representing the cult of Demeter. Circa 375 BC.

The obverse shows the head of Demeter wearing a wreath,

an earring and necklace, and the signature "APIΣTOΞE" of

the die-cutter Aristoxenos, who also made dies for nearby

Herakleia. Diameter 22 mm, weight 7.88 grams.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18200338.

|

Metapontion (Μεταπόντιον; Latin, Metapontium), on the gulf of Tarentum, southern Italy, was a colony of Achaea in the Peloponnese, founded around 700-690 BC.

At the end of the first century BC Strabo reported the legend that the city had been founded by Greeks from Pylos, southwestern Peloponnese, at the time their aged king Nestor returned from the Trojan War. The Metapontians apparently prospered from the fertility of the land and could afford to send a "golden harvest" (θερος χρυσοῦν) as a votive offering to the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. This is taken to have been ears of grain made of gold.

"Next in order is Metapontium, at a distance of 140 stadia from the sea-port of Heraclea. It is said to be a settlement of the Pylians at the time of their return from Ilium under Nestor; their success in agriculture was so great, that it is said they offered at Delphi a golden harvest."

Strabo, Geography, Book 6, chapter 1, section 5. Edited by H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer. George Bell & Sons, London, 1903. At Perseus Digital Library.

The city appears to have been destroyed long before the time of Pausanias, in the mid second century AD.

"How it came about that the Metapontines were destroyed I do not know, but today nothing is left of Metapontum but the theatre and the circuit of the walls."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 19, section 11. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

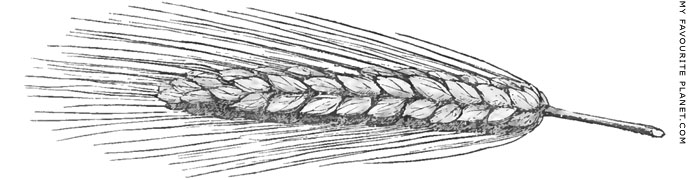

A drawing of an ear of bearded wheat, by the British

traveller and archaeologist Charles Fellows (1799-1860).

|

Charles Fellows travelled through southwestern Anatolia in 1838, 1840, 1842 and 1843, discovering and exploring several ancient Lycian cities. During his first journey he discovered the ancient Lycian capital Xanthos (Greek, Ξάνθος; Lycian, Arnna), which he described as "my favourite city", and from where he later took artefacts, including the surviving parts of the famous Nereid Monument, for the British Museum (see Museum boom part 1 at The Cheshire Cat Blog).

He noted the customs and ways of life of local people as well as the plants and crops in the area. Although the bearded wheat grown in Anatolia reminded him of depictions and symbols of Ceres, he did not report on any evidence of the worship of Demeter and Persephone in Lycia. An entry from his journal, written 19th April 1838, while he was in Xanthos, Lycia (at the village of Kınık, Antalya Province, southwest Turkey):

"The only wheat grown in Asia Minor is bearded, and this is the peculiar kind represented in the figures of Ceres and upon ancient coins."

Charles Fellows, A journal written during an excursion in Asia Minor, 1838, page 235. John Murray, London, 1839. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

A silver stater from Lokri Epizephyrii, Magna Graecia (Ἐπιζεφύριοι Λοκροί,

today Locris, Calabria, southern Italy), with the head of Demeter in profile,

facing left, wearing a grain wreath and an earring with pendants.

Circa 369-338 BC.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. |

| |

A silver stater from Pheneos (Φενεός, Feneos), Arcadia, with the

head of Demeter in profile, facing right, wearing a grain wreath,

a disc and crescent earring with pendants, and a pearl necklace.

Circa 360-340 BC. Diameter 24 mm, weight 11.85 g.

Altes Museum, Berlin. From the collection of Dr. Alfred von Sallet.

Numismatic Collection, Berlin State Museums (SMB). Inv. No. 18214906.

|

Pheneos (Φενεός) was a city in Arcadia, northeastern Peloponnese, Greece. Today it is in the Prefecture of Corinthia. It stood at the foot of Mount Kyllene, the mythical birthplace of Hermes, was an important cult centre for the god, and the location of an annual festival of the Hermaea. It also had sanctuaries for Demeter and Asklepios.

The reverse side of the coin shows Hermes carrying the infant Arkas, and the inscription ΦΕΝΕΩΝ (see the photo of another coin of this type on the Hermes page).

The design of these staters, as well as coins minted around the same time in Messene (Μεσσήνη, southwestern Peloponnese) depicting Demeter, and Opuntian Locris (Λοκροὶ Ὀπούντιοι, central Greece) depicting Persephone, is thought to have been influenced by the dekadrachms of Syracuse, designed by Kimon and Euainetos (see examples on the Nike page). See also Sicilo-Punic and Carthaginian coins with similar heads, identified as Tanit-Persephone, below. |

|

| |

A small bronze coin of the island Kos with

the head of Demeter in profile, facing right.

220-200 BC.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. N712. |

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin of the Cycladic island Syros (Σύρος), with

the head of Demeter facing right, wearing a wreath with ears of corn

and an earring. Circa 150 BC. Diameter 31 mm, weight 15.88 grams.

The reverse side shows a laurel wreath surrounding two Kabeiroi

(or Dioskouroi) standing facing, each nude except for a cloak,

holding a sceptre or spear, and surmounted by a star, and the

inscription "ΘEΩN KABEIΡΩN ΣΥΡIΩN" (divine Syrian Kabeiroi).

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18200337. |

| |

Roman bronze sestertius coin showing Ceres (Demeter) sitting on the

sacred kiste (cista mystica), holding a torch in her left hand and three grain

stalks in the right. Circa 128-135 BC. Diameter 34 mm, weight 25.16 grams.

One of many coin types issued by Empress Vibia Sabina (83 - 136/137 AD),

wife of Emperor Hadrian. In 128 AD she was awarded the title of Augusta

which allowed her to issue her own coinage.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18200340.

See also a statue of Vibia Sabina as Ceres in Part 1.

Read more about the Bode Museum Numismatic Collection

in Big Money at the Cheshire Cat blog. |

| |

| |

Depictions of Isis-Demeter |

|

|

Marble relief of Isis-Demeter from the facade of the main temple

of the sanctuary of Isis, Dion, Macedonia, Greece. 2nd century BC.

Dion Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 410. |

| |

Herodotus was the first known author to identify Demeter with the Egyptian goddess Isis. He, and later others, recognized parallels in the myths of the two deities, both of whom were associated with fertility, the underworld and the cycles of life, growth, decline and death. Like Demeter, Isis undertook a long search for her closest companion, her brother and husband Osiris, who had been killed by their brother Seth. She finally recovered his body and brought him back to life, restoring order and cosmic balance. Greeks living in Egypt and the Levant (Syria) adapted local beliefs and practices, mixing them with their own to suit their religious and cultural preferences, and, particularly from the Hellenistic period, the cults of syncretic deities such as Isis-Demeter, Zeus Ammon and Serapis were spread around the Greco-Roman world.

For further information about the relief and the sanctuaries of Demeter and Isis at Dion, see Dion: the garden of the gods at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

|

| |

|

|

|

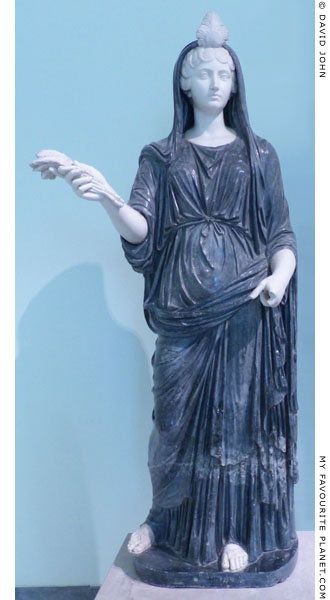

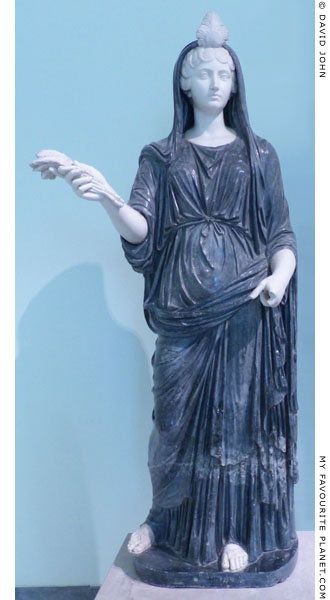

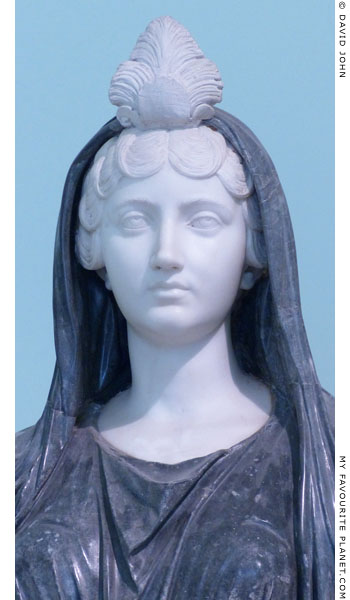

Marble statue of Isis-Demeter wearing a crescent moon topped by two ears of corn.

The frontal pose and garments resemble those of types of statues of Isis.

First half of the 2nd century AD. Proconnesian marble. Provenance unknown.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 126074.

Until 1951 in the Barberini Collection. |

|

| |

|

|

|

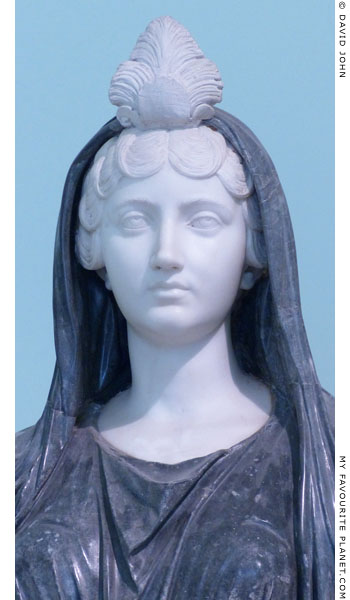

Marble statue of Fortuna-Isis restored as Faustina the Younger dressed as Ceres.

2nd century AD. Bigio morato marble. The head, hands

and legs are modern restorations. Height 192 cm.

Faustina the Younger (or Faustina Minor, Annia Galeria Faustina Minor,

circa 130-175 AD) was the daughter of Emperor Antoninus Pius and

Faustina the Elder. She became empress as the wife of Marcus Aurelius.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6368. Farnese Collection.

For further information about Roman empresses

depicted as Ceres, see Demeter and Persephone Part 1. |

|

| |

Ears of wheat in the right hand of the restored statue of Faustina / Ceres above. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

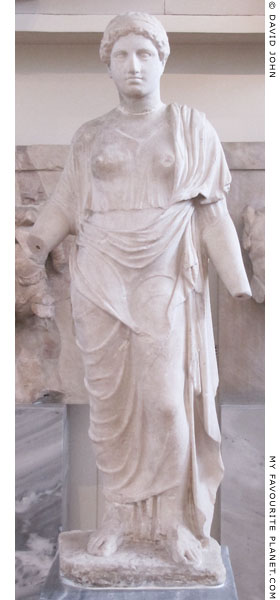

Larger than lifesize marble statue of Isis-Demeter holding ears of wheat in her

right hand; much of the left hand is now missing. From the south porch of the

temple in the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza, near Marathon, Attica,

built around 160 AD by the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus (circa 101-177 AD).

For further information about the sanctuary, see the Herodes Atticus page.

A statue of Isis and one of Osiris flanked each of the four entrances to the temple.

The other surviving Isis, from the west porch, depicts her as Isis-Aphrodite, and

the three Osiris statues found there are of the Antinous-Osiris type (se Antinous).

Mid 2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Fragmentary marble head of Isis-Demeter wearing

a tall diadem, decorated with the uraeus, the snake

symbolizing Egyptian royalty, and ears of corn and

poppies, agricultural attributes of Demeter.

Late 2nd century AD. Provenance unknown.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 75065.

Donated by the marquise Céline Cappelli in 1917. |

| |

| |

Depictions of Demeter and Persephone |

|

|

| |

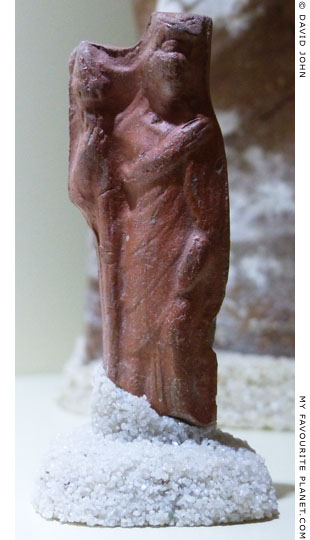

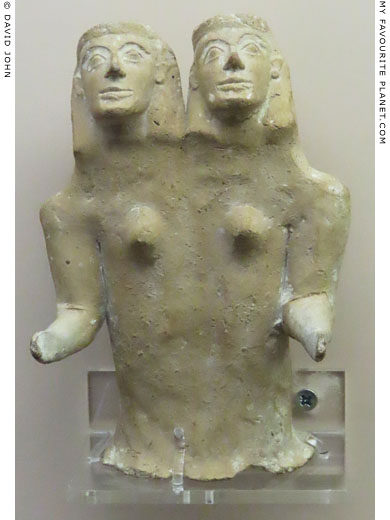

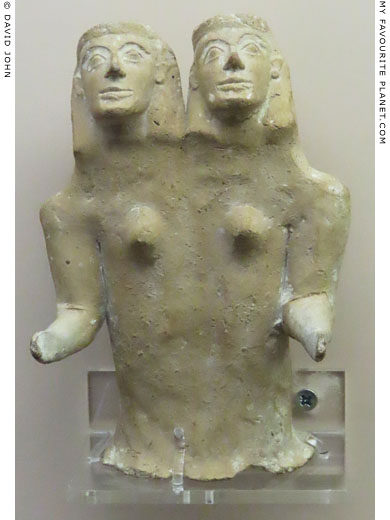

Part of a terracotta figurine depicting a pair of female deities,

probably Demeter and Persephone. The two heads in the

Daedalic style, share a single body, a type of depiction also

known from votive figures of around the same period found

at the Sanctuary of Zeus Meilichios in Selinunte, Sicily.

From an inhumation burial of an adult and a young woman

in a single tomb, Papatislures T 27 (35). 625-600 BC.

Found during excavations in the cemetery at Papatislures,

near the ancient city of Kamiros, western Rhodes.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Terracotta "pappades" or plank idols that may represent Demeter and Persephone.

Made in Boeotia, central Greece. 6th century BC.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. Nos. 15.710, 1317, 597 and 3294.

|

Flat-bodied "board-idols", "plank Idols" or "plank figures" (σανίδες, sanides, from plank, board, piece of wood; sanidomorpha, plank-shaped) were made in various forms around the Aegean from prehistoric times. Pappades (Παππάδες; from παππας, pappas, priest) are types of plank figures made in Boeotia between around 625 and 550 BC, during the Archaic period. Their name is due to the fact that many of the figures wear a polos (e.g. the figure on the far right in the photo above) similar to the tall cylindrical hats worn by modern Greek Orthodox priests. Most pappades have been found in tombs, and the majority for which the provenance is known are from Tanagra in Boeotia.

Some have human faces, while others have oddly-shaped "mouse heads" or "bird beaks". They appear to be females, have a variety of long or short hairstyles, wear jewellery, and their broad, flat bodies are clothed in robes with embroidered patterns, the details painted in black and purple. They are thought to represent Demeter and Persephone (Hera has also been suggested), or were dedicated to the goddesses. |

|

| |

Terracotta "pappades" (plank idols) from Boeotia, central Greece. Mid 6th century BC.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Inv. Nos. 1925.7, 1926.3, 2002.4, 1955.29.

Inv. No. 2002.4 bequest of Herbert Joost, Hamburg. |

| |

Corinthian terracotta figurines of two females, perhaps

Demeter and Persephone, sitting side by side in a cart.

Around 600 BC. Said to be from Thebes.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1895.10-29.5 (Terracotta 897). Acquired in 1895.

|

| The style of decoration resembles that of Boeotian Geometric vases (see the "pappades" above), while the faces of the figures has been described as "somewhat oriental in character". Each figure wears a polos decorated with a frieze of ducks facing right. Their dresses are decorated with cross-hatching. The girdle of the figure on the left has a frieze of two animals (horses?) running to the right. The girdle of the right-hand figure has a band of vertical hatching over one of wavy lines. |

|

| |

Terracotta figurine of two seated goddesses, perhaps Demeter and

Persephone. They have been described as sharing a cover (himation

or cloak). As in the much earlier figurine from Kamiros above, the

bodies of the two figures almost seem to merge with each other. From an inhumation burial of an adult, Macri Langoni T 26 (54).

450-420 BC. Found during excavations in the cemetery at Macri

Langoni, near Kamiros, Rhodes.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

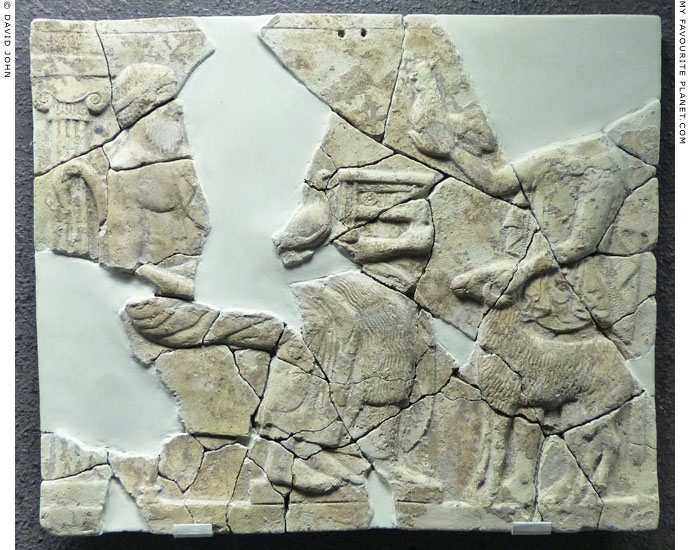

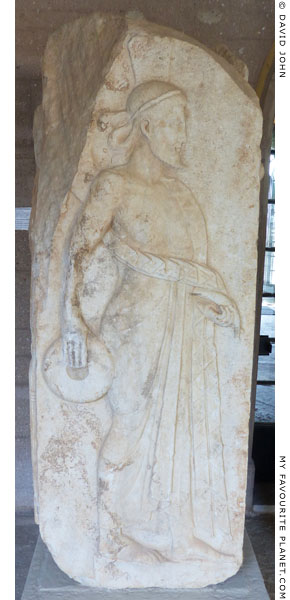

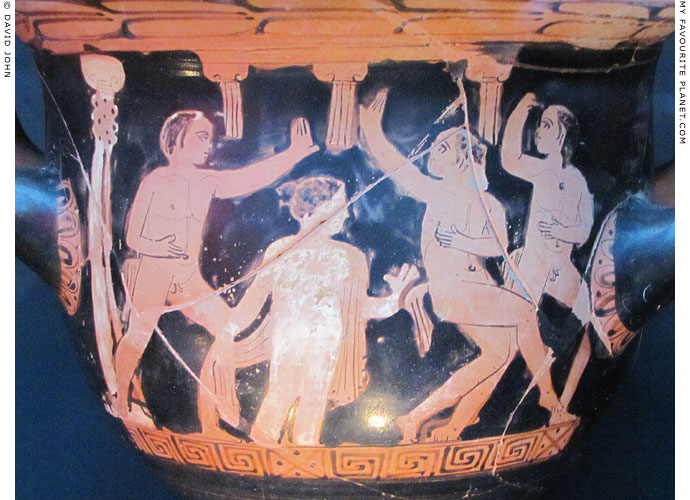

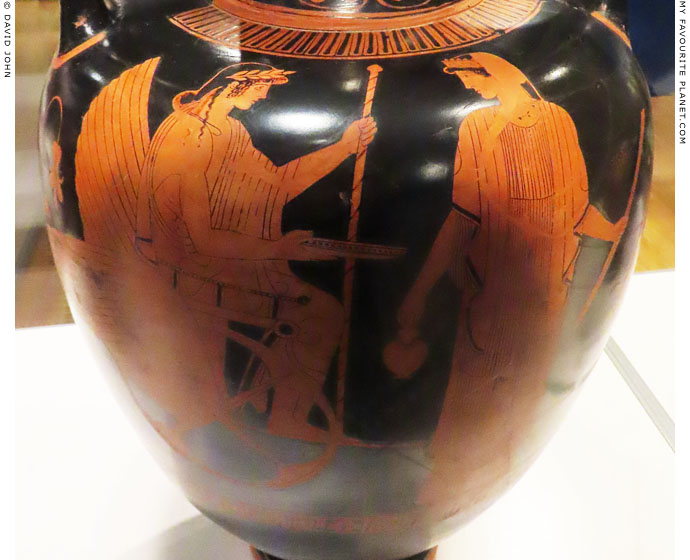

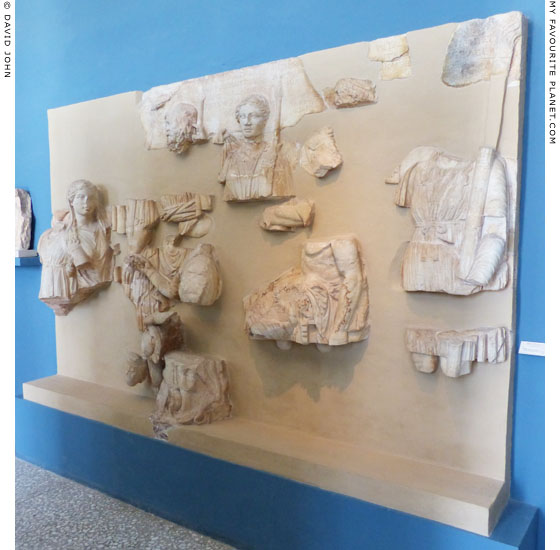

Hephaistos with two goddesses, thought to be Demeter and Persephone, on

a fragmentary Archaic relief depicting the myth of the Gigantomachy (the battle

between the Olympian gods and the Giants), from the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi.

A fragmentary slab of the left (west) end of the north frieze of the Ionic treasury,

built for the people of Siphnos around 525 BC (before 524 BC). Parian marble.

On the far left Hephaistos, wearing a chiton, stands at his bellows preparing

fireballs as weapons for the gods (see detail below). Next to him stand two

goddesses, dressed in long chitons, facing two Giants with Corinthian helmets,

round shields and spears, attacking them from the right.

On another fragment of the relief, part of the signature of the sculptor has

survived on the shield of a Giant, although his name is now missing. He is

referred to as "Master B", and Aristion of Paros, Boupalos of Chios and Endoios

have been suggested. See the Aristion of Paros page for further details.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

See also a relief of Demeter with Athena and Hera

from the east side of the frieze, above. |

| |

The fragment of the Gigantomachy relief from the north frieze of the

Siphian Treasury, Delphi, depicting Hephaistos, Demeter and Persephone. |

| |

Terracotta figurines dedicated to Demeter and Persephone and clay lamps.

Made in Sicily around 500-450 BC. From Gela, Sicily.

British Museum.

Terracottas: GR 1863,0728.273, 274, 266, 268 and 269.

Lamps: GR 1863,2728.117 and 121.

|

The worship of Demeter and Persephone (Kore) was particularly popular in Sicily. In and around Gela, on the south coast, there were several major sanctuaries dedicated to the goddesses at which a large number of terracotta votive offerings and lamps have been found. The lamps suggest that rituals took place in semi-darkness.

Southeast of the city's acropolis (Lindioi) there was a sanctuary of Demetra Thesmophoros, founded in the 7th century BC on a low hill now known as Bitalemi, on the coast east of the mouth of the Gelas river. Excavations at the thesmophorion, led by Piero Orlandini 1964-1967, revealed disctinct phases of development from around 640 BC, including a major restoration about 480 BC, until the destruction of the city and the sanctuary by the Carthaginians around 405 BC. Another sanctuary at Predio Sola may have been dedicated to Demeter, Kore or Aphrodite. |

|

| |

Ceramic arula (portable altar) with a high relief depicting a triad of goddesses,

probably Demeter (centre) and Persephone with Hekate, Aphrodite or Artemis.

In the register above is a zoomachy: a lioness or panther attacking a bull.

Pink clay. 500-480 BC. From the emporion (ἐμπόριον, trading centre)

at the Bosco Littorio, Gela, Sicily. Height 113 cm.

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Sop. BL 30.

|

One of three similar, well-preserved portable altars with reliefs of extraordinarily fine quality, discovered with fragments of others at the Bosco Littorio archaeological site in December 1999, during excavations by Lavinia Sole under the direction of Sopraintendente Rosalbe Panvini. The other two altars have reliefs depicting Medusa carrying Pegasus and Chrysaor, and Eos abducting Kephalos. All three are exhibited in the excellent Gela museum.

These light-weight altars, probably made in the same workshop, had apparently never been used, and may have been made for sale or export to customers who for some reason never received them. The site at the Bosco Littorio, on the coast of Gela, south of the acropolis (Lindioi) and west of the mouth of the Gelas river, is thought to have been an emporium due to finds of objects related to trade, including transport amphorae and imported vessels from Attica and Chalcis (Euboea) in Greece. The buildings at the site have been dated to the early 6th to early 5th centuries BC, and the altars appear to have been abandoned there around 480 BC, when the buildings of the area were violently burnt and destroyed.

The bodies of the altars, made of clay slabs, are hollow and perforated by large holes (see the photo on the Medusa page), making them lighter and easier to transport. These are among several portable altars found in Sicily (see, for example, a portable altar from Selinunte on the Medusa page). The reliefs, which were made separately then attached to the bodies before firing, were originally highly coloured, with red used as a background colour, and a yellow pigment which became almost vitrified (glass-like) during firing.

On this altar, three standing female figures are shown in stiff, frontal poses, typical of the Archaic period, and the braided locks of the figure in the centre are reminiscent of Daedalic style of the 6th century BC. Each wears a polos and a long-sleeved peplos. The central figure also wears a cloak, her hands resting on the braids which hang over the front of each shoulder. The other two, both probably made from the same mould, have formally styled hair with locks tied behind the ears with bands, then spiral down behind the shoulders. Their arms are at their sides and they each hold a wreath or garland in one hand. If the figures were made in the same mould, then the wreaths must have been modelled by hand after moulding.

Described as "triade divinità" (triad of female divinities), the figures have been interpreted as a triad of chthonic (underworld) goddesses. The central figure is thought to be Demeter, one of the other two Persephone, and the third possibly Hekate, Aphrodite or Artemis. The figures have been compared to those on a metope from Selinunte (see Part 1), whose identity is also uncertain.

The relief of a lean lioness attacking a bull in the upper register may further inform the debate over whether such depictions where influenced by Persian Achaemenid iconography, known from the monumental reliefs at Persepolis. It has been argued that the motif belongs to a Greek tradition which predates the arrival of the Persians in the Greek world by several centuries (see, for example, illustrations on Stageira gallery page 30). It has been suggested that the lioness killing the bull to feed her young is a symbolic echo of a priest sacrificing a bull to a deity to ensure the spiritual and physical welfare of the community.

On the sides of the altars are lotus blossoms painted in brown and black, now barely visible. The lotus flower was associated with female sexuality and fertility, birth and rebirth, and, like the poppy, with Demeter and Persephone (see Part 1). The flowers are also thought to have been used as ingredients in narcotic preparations consumed during ritual worship of the goddesses.

During my recent visit to the Gela museum the altar was in London, so I was unable to photograph it. This is a press photo for the fascinating exhibition, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, at the British Museum, 21 April - 14 August 2016. Photo © Regione Siciliana.

See: Dirk Booms and Peter Higgs, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, exhibition catalogue, pages 58-62. The British Museum, London, 2016.

The archaeological site at the Bosco Littorio is not usually open to the public, but is sporadically opened on special occasions. |

|

|

| |

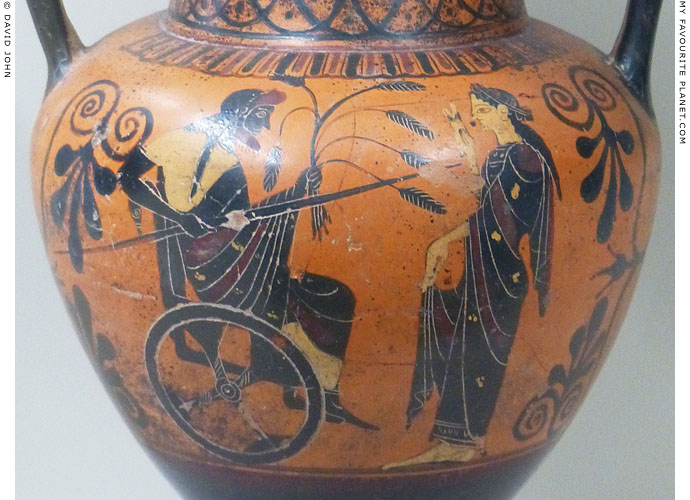

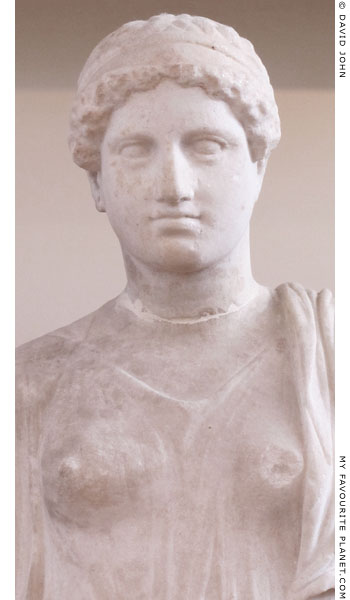

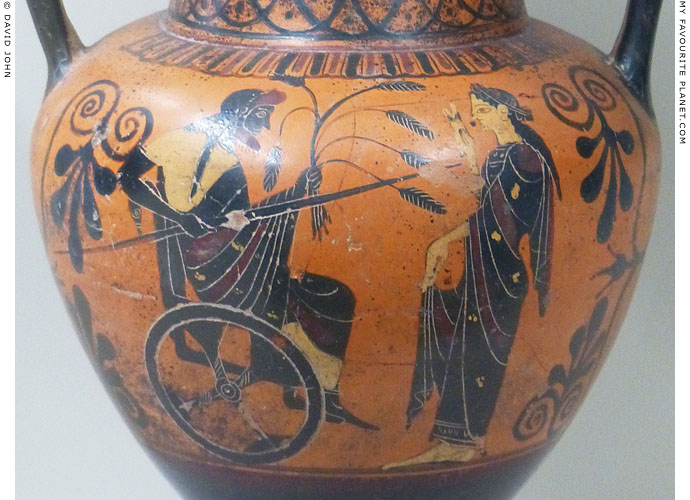

Marble statues of two goddesses seated on chests, from the east pediment of the Parthenon,

thought to depict Persephone (left) and Demeter. 438-432 BC.

British Museum. East pediment E and F. Part of the "Elgin Marbles".

|

The pedimental sculptures of the Parthenon were made of Pentelic marble by Pheidias and his pupils 438-432 BC. According to Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 24, section 5), the theme of the east pediment was the birth of Athena, and that of the west pediment the contest between Athena and Poseidon for the patronage of Athens.

Each of the sculptures is actually a free-standing statue, executed in the round, rather than the type of reliefs known from the pediments of other temples (see for example the high relief of Dionysus from the Temple of Apollo in Delphi). They are remarkably detailed and finished, particularly considering that they stood so high on the Parthenon that many parts would not be visible to the viewer on the ground. An entire pediment can be seen only when standing some distance from the building; the view of the figures from the angle shown in the photo above was not possible when they were in place. Even the details such as drapery of the backs of the figures, although not of the same quality as the fronts, are finished to a surprisingly high degree.

The figure on the left rests her left forearm on the right shoulder of her companion, whose arms are raised. It has been suggested that she may surprised or disturbed by the swiftly moving figure to the right, who may be Artemis or Hebe, the cup-bearer of Zeus. The reclining nude male figure to the left of the pair has been identified as Dionysus.

The composition of this pair may have been copied by Damophon for the statue group he made for the temple of Despoina in Lykosoura (see below). |

|

|

Part of the display of statues and votive objects in the Baths of Diocletian, Rome,

found at the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore (Persephone) at Casaletto, in the

territory of Ariccia, Lazio (ancient Latium), Italy.

End of the 4th - first half of the 3rd century BC. The sanctuary

was discovered by chance in 1927 by farm workers.

Epigraphic Museum, Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome.

|

Ariccia (or Aricia), in the Alban Hills, 25 km southeast of Rome, was founded around 9th - 8th century BC, according to legend by Archilochos, a Siculian (Sicilian) chief. From the late 6th century BC until 338 BC it became one of the most important members of the confederation of 30 settlements and tribes of Latium, known today as the Latin League. In the first century BC Cicero (106-43 BC) described the municipium of Ariccia as "very old" and "federated", that is semi-independent and allied to Rome.

The large number of terracotta votive objects discovered at the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, including many depictions of deities and worshippers, indicate the strong influence of the art and culture of Magna Graecia and Sicily.

The centre of the museum display is a triangular dais on which stand three ceramic statues of enthroned goddesses: the godddess on the left has not been identified, in the centre is Demeter, and on the right Kore holding a piglet. Behind this triad are a headless female statuette, a bust of Kore and a bust of Demeter (not in photo, see photos below). To the right of the dais, a glass case displays votive ceramic heads from the sanctuary.

At the time the following photos were taken the room was being renovated and some of objects were not on display. The bust of Demeter below, for example, is not the one described in the labelling and illustrated in the museum guide book [8]. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Ceramic statue of Demeter sitting on a richly decorated throne.

She wears a long chiton (tunic), a cloak, a diadem with ears

of corn and jewellery, and holds ears of corn in her right hand.

From the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Ariccia, Lazio, Italy.

Rosy-beige clay. End of the 4th - first half of the 3rd century BC.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. |

|

| |

Partly restored ceramic bust of Demeter wearing a headband decorated

with ears of corn, a chiton, a cloak and rosette earrings with triangular

pendants. Her thick wavy hair is tied back and falls over her shoulders

(some of the hair and the back of the head are missing).

From the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Ariccia, Lazio, Italy.

Beige clay. End of the 4th - first half of the 3rd century BC.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. |

| |

|

|

|

Ceramic statue of Kore, enthroned and holding a votive piglet in her left hand.

She wears a chiton, a cloak and jewellery similar in style to that of Magna Graecia.

From the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Ariccia, Lazio, Italy.

Reddish clay. End of the 4th - first half of the 3rd century BC.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. |

|

| |

Ceramic bust of Kore wearing a headdress decorated by

two upright ears of corn and radiating forms which appear

to be snakes, and a high-belted chiton. Her plaits, which fall

over her shoulders, are also decorated with ears of corn.

From the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Ariccia, Lazio, Italy.

Beige terracotta. End of the 4th - first half of the 3rd century BC.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. |

|

Limestone relief of two female figures, possibly Demeter and Persephone.

A metope from a Doric tomb. Made in Taranto, southern Italy around 300 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. Gr 1873.8-20.746 (Sculpture 793). |

| |

Reconstruction drawing of the Lykosoura statue group by Damophon of Messene,

in Lykosoura on Mount Lykaion, Arcadia, southwestern Peloponnese. 190-180 BC.

Left - right: Artemis, Demeter, Despoina (Persephone), the Titan Anytos.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Reconstruction by Guy Dickins of the British School at Athens, 1906.

Based on several fragments discovered during excavations and a

description of the statue group by Pausanias [9]. |

| |

The Lykosoura statue group

The Arcadian city Lykosoura (Λυκόσουρα) on Mount Lykaion and its sanctuary of Demeter and Despoina (Δέσποινα, usually translated as the Mistress, see note in Part 1) are considered to have been very ancient. The only ancient source on the location, Pausanias, reported the claim that it was the oldest city in the world.

"A little farther up is the circuit of the wall of Lycosura, in which there are a few inhabitants. Of all the cities that earth has ever shown, whether on mainland or on islands, Lycosura is the oldest, and was the first that the sun beheld; from it the rest of mankind have learned how to make them cities.

On the left of the sanctuary of the Mistress is Mount Lycaeus. Some Arcadians call it Olympus, and others Sacred Peak. On it, they say, Zeus was reared."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 38, sections 1-2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Demeter and Despoina were worshipped there according to the archaic Arcadian chthonic rites, thought to be quite different from those of the Eleusinian cult, and perhaps closer to those of the oriental Kybele or Magna Mater (Great Mother).

Pausanias wrote that when the Arcadians united (forming a synoikism) to found the city of Megalopolis (Μεγαλόπολις) around 370 BC because of the fear of Spartan expansion, the inhabitants of several Arcadian settlements were forced to move there. Those who dissented were either massacred or fled the Peloponnese. The Lykosourians refused to give up their city but were spared because they took refuge in the sanctuary of Demeter and Despoina (Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 27, sections 1-6). Later the Eleusinian cult spread through Arcadia, probably after being introduced to Megalopolis.

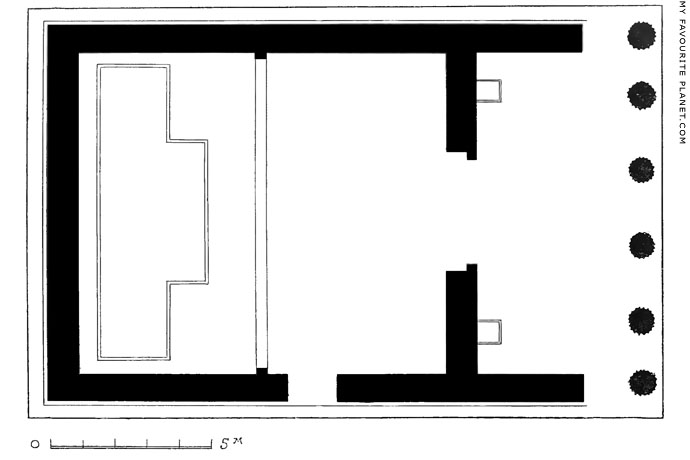

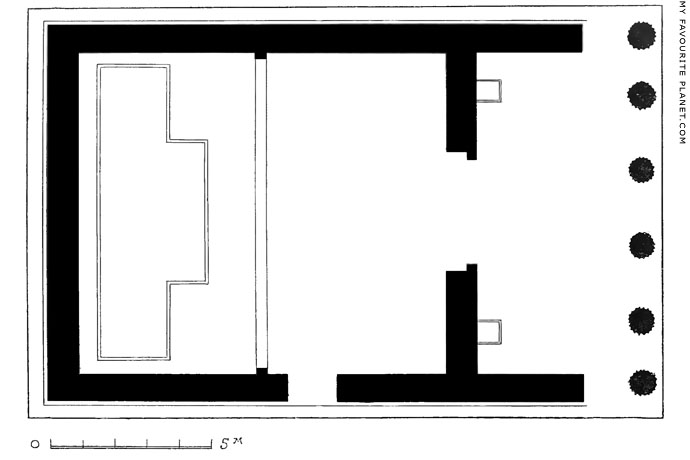

Although the location of Lykosoura was identified by the British traveller Edward Dodwell in 1806, the first excavations there were undertaken by the Greek Archaeological Society in 1889, 1890 and 1895, directed by Panagiotis Kavvadias (Παναγιώτης Καββαδίας, 1850-1928) and Konstantinos Kourouniotis (Κωνσταντίνος Κουρουνιώτης, 1872-1945), who also founded the small museum at the site. During the excavation of the Doric temple of Despoina (see plan below) over a hundred fragments of a group of four larger than lifesize statues were discovered [10].

Guy Dickins of the British School at Athens reconstructed the composition of the statues with the aid of the description of the group by Pausanias (see below). His reconstruction appeared to be largely confirmed a few years later by the publication by the Greek archaeologist Valerios Stais (Βαλέριος Στάης, 1857-1923) of a Roman Imperial period coin minted by nearby Megalopolis (7 km to the east), which had been locked away in the Athens museum (see photo, below right). On the obverse side of the coin is the head of Julia Domna (170-217 AD), second wife of Emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193-211 AD), and on the reverse what is thought to be a representation of the Lykosoura statue group.

The group was around 5.6 metres high, including the 8.4 metre long, T-shaped limestone pedestal. Although Pausanias described the statues he saw as "made from a single piece of stone", this group was constructed of several separately worked pieces joined by iron and lead dowels and cement. Modern scholars have concluded that he may have been misinformed by his local guides, which has led to the question of whether he was also misled into believing the group was by Damophon. Konstantinos Kourouniotis commented:

"One imagines that Pausanias derived the story about the single block of marble, from which the group of Demeter and Despoina was constructed, from servants of the temple who were in the habit of playing on the credulity of tourists in order to enhance the miraculous nature of their sanctuary." [see note 9]