| |

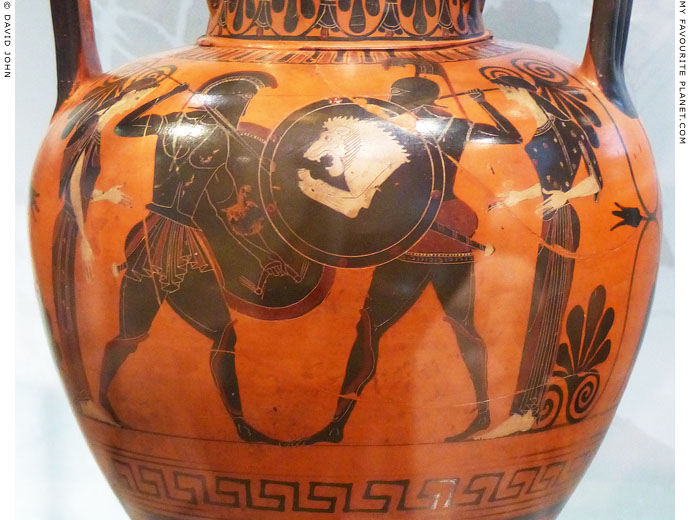

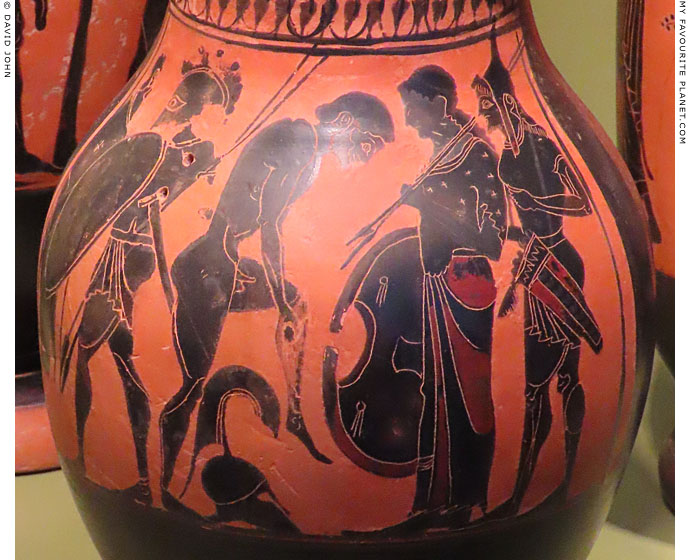

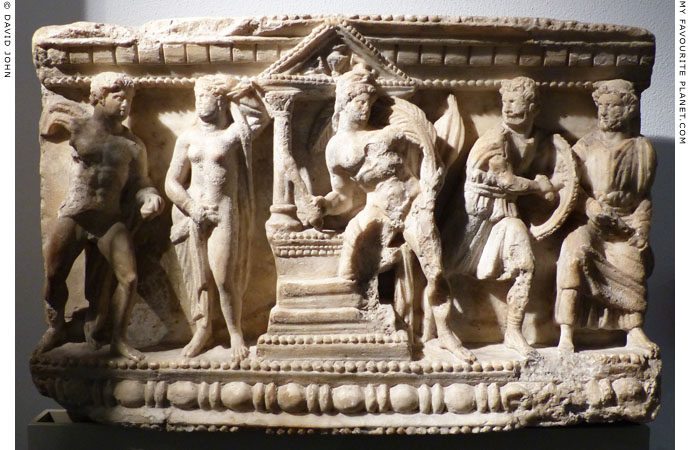

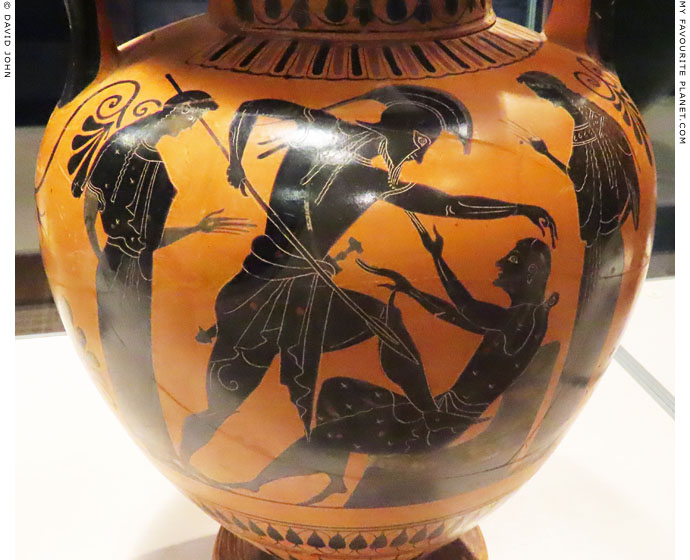

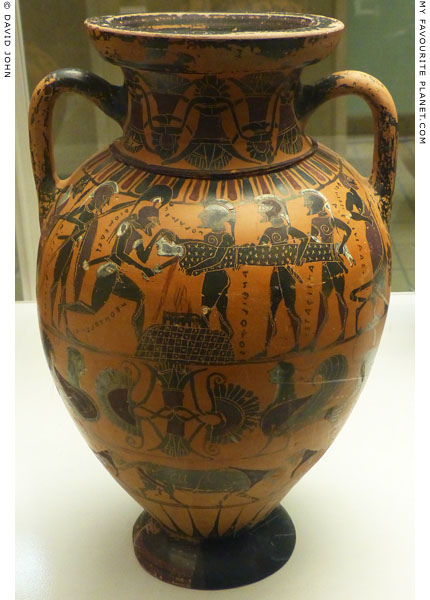

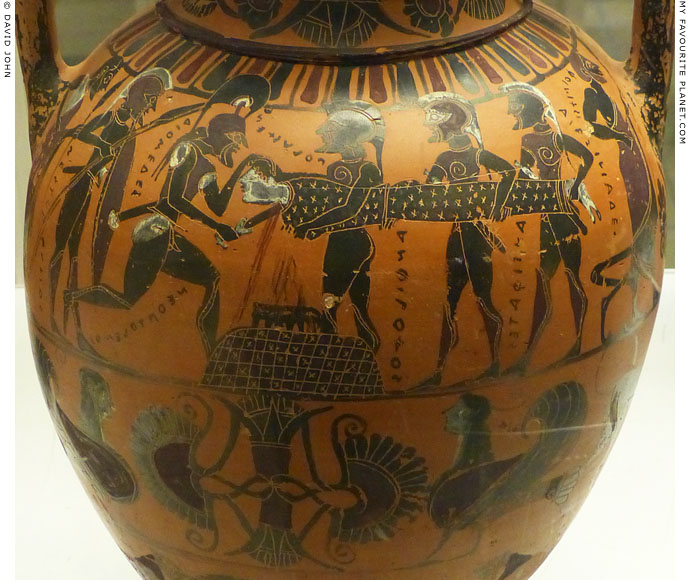

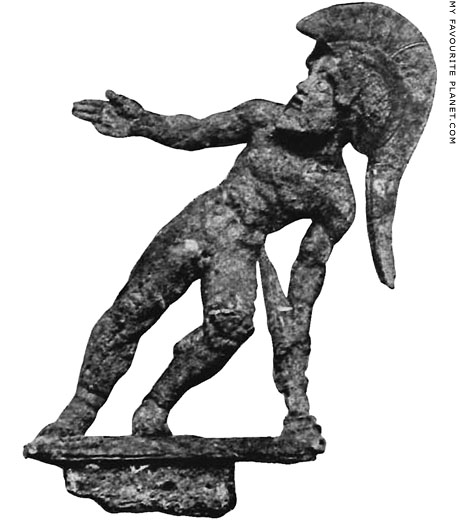

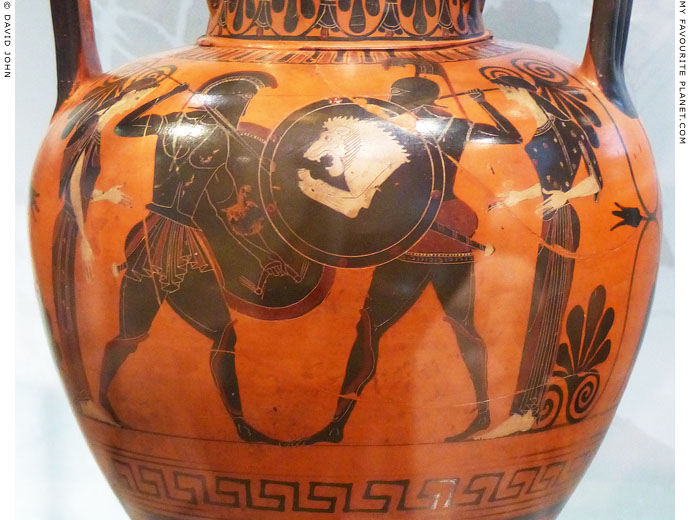

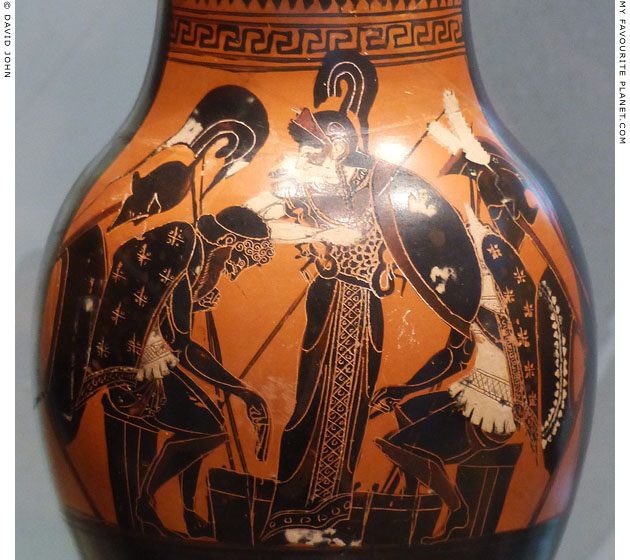

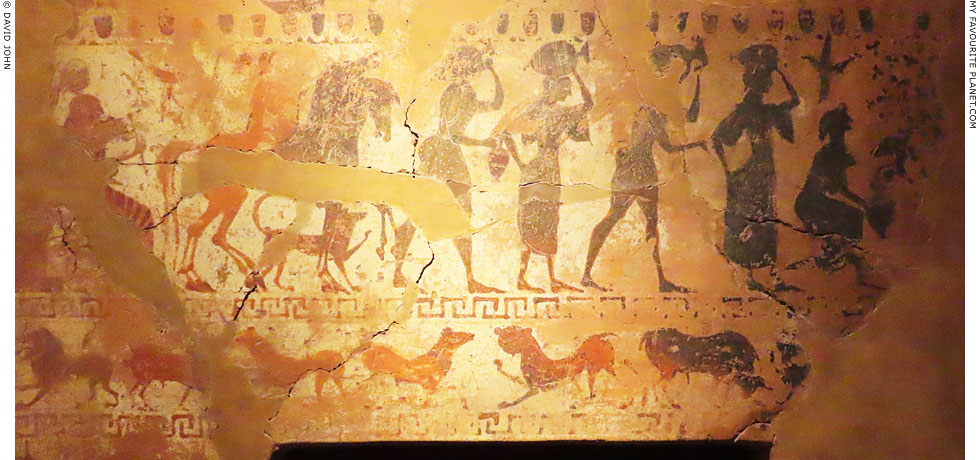

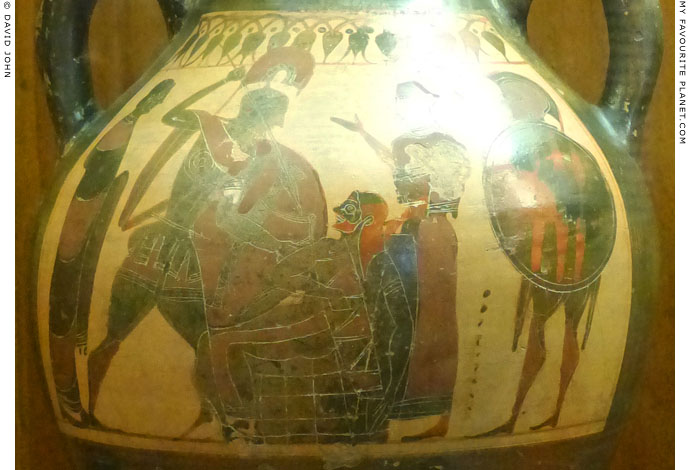

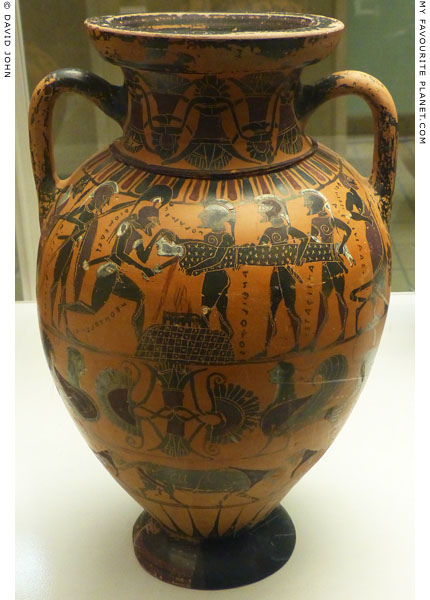

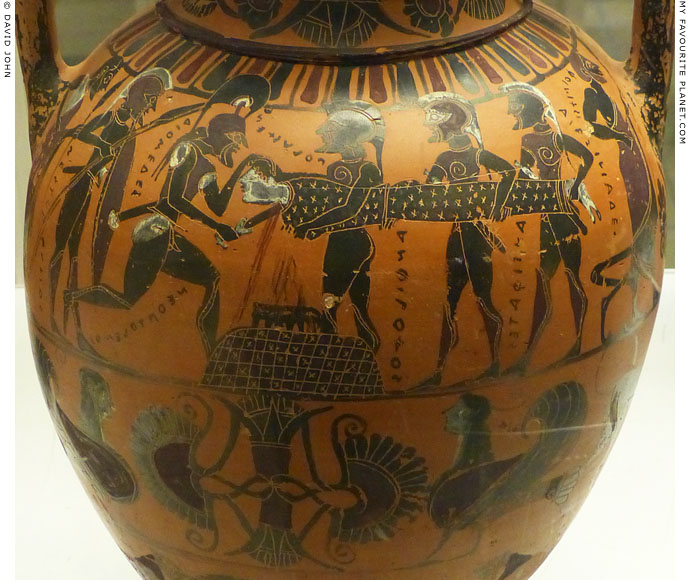

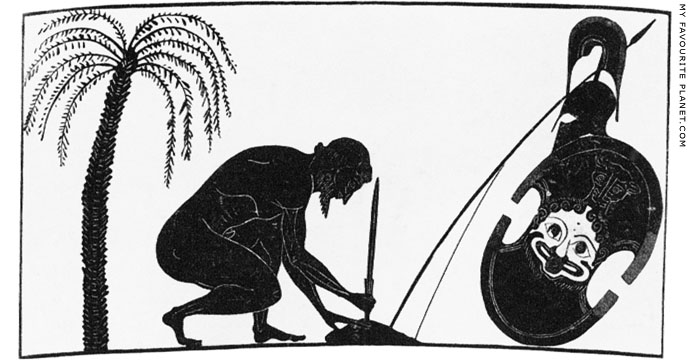

Achilles fights the Ethiopian king Memnon, watched by their divine mothers Thetis and Eos.

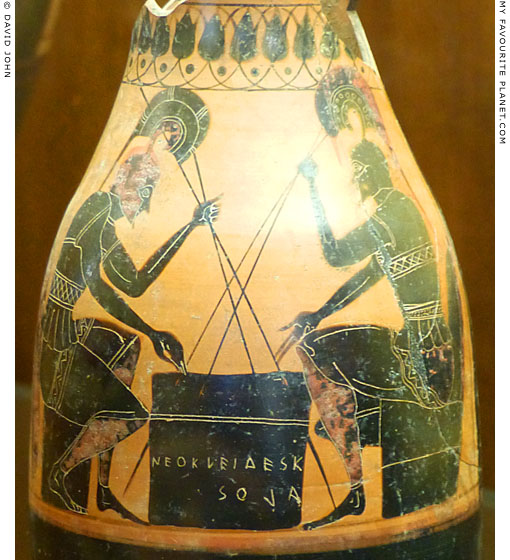

Detail of an Athenian black-figure amphora, attributed to the Antimenes Painter, 550-501 BC.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. 1965-116. Ex Spencer-Churchill Collection. |

| |

Hesiod wrote that "brazen-crested Memnon" (Μέμνων), was the son of Tithonus (a brother of Priam) and Eos (Ἠώς, Dawn), and was king of the Aethiopians (Theogony, lines 984-985). According to an epitome of The Aethiopis (Αἰθιοπίς, the song of the Aethiopians), a lost epic poem of the Trojan cycle, he was an ally of Troy in the Trojan War, and was killed in battle by Achilles. It also states that Memnon wore armour made by the god Hephaistos, who in The Iliad made armour for Achilles (see below).

Homer did not relate the story of the confrontation between Achilles and Memnon, and only refers to Memnon twice in The Odyssey, once just as "the glorious son of the bright Dawn", who killed Antilochus, son of Nestor. However the killing of Memnon by Achilles was mentioned or alluded to by a number of other later writers, including Aischylos, Pindar, Isocrates, Ovid, Apollodorus and Philostratus. In the epic poem Posthomerica (τὰ μεθ᾿ Ὅμηρον) by Quintus of Smyrna (Κόϊντος Σμυρναῖος, Quintus Smyrnaeus), probably written in the 4th century AD, Achilles killed Memnon to avenge Antilochus, an echo of his slaying of Hektor as vengeance for the death of Patroklos (Πάτροκλος, glory of the father) in The Iliad.

The single combat between Achilles and Memnon appears to have been a well known theme in Greek art, and is depicted in paintings on a number of surviving ceramic vessels. Pausanias mentioned that the duel was depicted on two votive offerings in Olympia. The first was one of several mythological scenes, including Homeric themes, on a richly decorated Archaic cedar-wood chest, referred to as the "chest of Kypselos", dedicated by the Corinthians, in the Temple of Hera. The scene of Achilles and Memnon fighting included their respective mothers.

"There is also a chest made of cedar, with figures on it, some of ivory, some of gold, others carved out of the cedar-wood itself. It was in this chest that Cypselus, the tyrant of Corinth, was hidden by his mother when the Bacchidae were anxious to discover him after his birth. In gratitude for the saving of Cypselus, his descendants, Cypselids as they are called, dedicated the chest at Olympia. The Corinthians of that age called chests kypselai, and from this word, they say, the child received his name of Cypselus.

On most of the figures on the chest there are inscriptions, written in the ancient characters. In some cases the letters read straight on, but in others the form of the writing is what the Greeks call bustrophedon..."

"... In the fourth space on the chest as you go round from the left is Boreas, who has carried off Oreithyia; instead of feet he has serpents' tails. Then comes the combat between Heracles and Geryones, who is represented as three men joined to one another. There is Theseus holding a lyre, and by his side is Ariadne gripping a crown. Achilles and Memnon are fighting; their mothers stand by their side."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 17, sections 5-6, and chapter 19, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Kypselos (or Cypselus; Greek, Κύψελος) was the first tyrant of Corinth who ruled circa 657-627 BC. The story of his mother Labda hiding him in a chest when he was a baby was related by Herodotus (Histories, Book 5, chapter 92). If the story was true, and if the chest Pausanias saw was the same, and if the scenes had been carved at the time of Kypselos, or before, they would have been among the earliest Homeric themes in art known from ancient literature. But that is a lot of ifs.

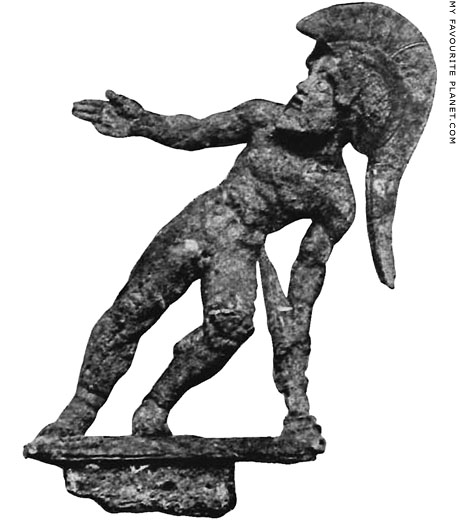

The second depiction of Achilles and Memnon at Olympia was part of a group of statues by Lykios, son of Myron, made for Apollonia on the Ionian Sea, a colony of Korkyra (Corfu). Apart from Achilles and Memnon, the group included four other pairs of Homeric heroes in duels, as well as Thetis (mother of Achilles) and Hemera (Eos, mother of Memnon) pleading with Zeus for the lives of their respective sons.

"By the side of what is called the Hippodamium is a semicircular stone pedestal, and on it are Zeus, Thetis, and Day [Hemera] entreating Zeus on behalf of her children. These are on the middle of the pedestal. There are Achilles and Memnon, one at either edge of the pedestal, representing a pair of combatants in position. There are other pairs similarly opposed, foreigner against Greek: Odysseus opposed to Helenus, reputed to be the cleverest men in the respective armies; Alexander [Paris] and Menelaus, in virtue of their ancient feud; Aeneas and Diomedes, and Deiphobus and Ajax son of Telamon.

These are the work of Lycius, the son of Myron, and were dedicated by the people of Apollonia on the Ionian sea."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 22, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

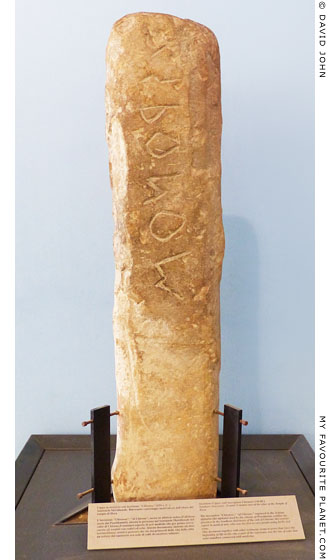

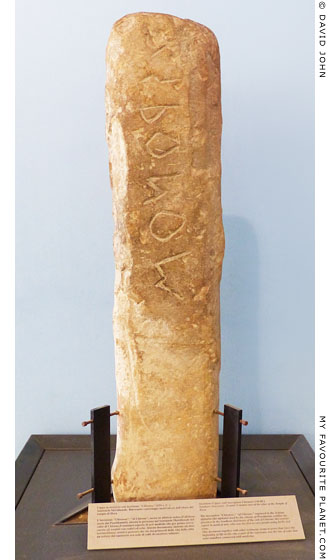

Two fragments of black limestone found at Olympia, inscribed at the edges at which they join with the name Memnon (Μέμνων), are thought to be parts of the semicircular pedestal on which the statue group by Lykios stood.

Μέμνω - ν

Inscription IvO 692 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Height 30.5 - 31.5 cm, combined width 54 cm, depth 88 cm.

See: Ernst Curtius and Friedrich Adler (editors), Olympia: die Ergebnisse der von dem Deutschen Reich veranstalteten Ausgrabung, Wilhelm Dittenberger and Karl Purgold, Textband 5: Die Inschriften von Olympia, No. 692, columns 711-712. A. Ascher & Co., Berlin, 1896. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Pausanias also wrote that the duel was depicted on the "throne" of Apollo (Ό θρόνος του Άμυκλαίου Απόλλωνος, the throne of Apollo Amyklaios) at Amyklai (Ἀμύκλαι), 6 km south of Sparta in the southern Peloponnese. Like the "chest of Kypselos" in Olympia, the throne, made by Bathykles of Magnesia around 550 BC, was covered with relief representations of mythological scenes.

"There is wrought also the single combat of Achilles and Memnon..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 18, section 12. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

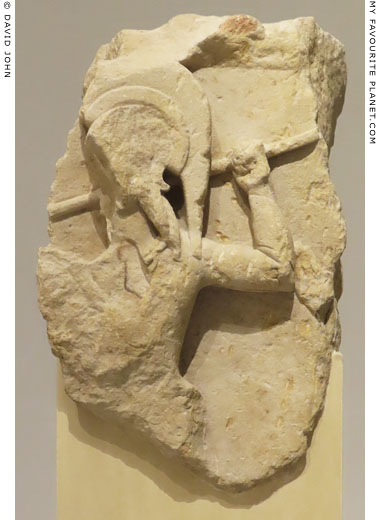

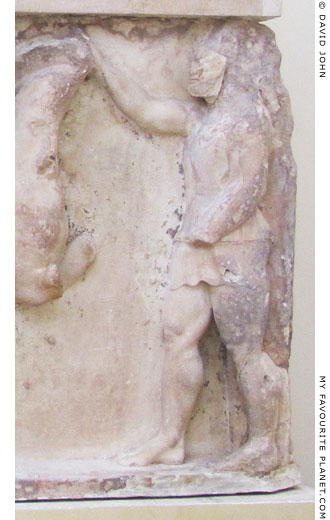

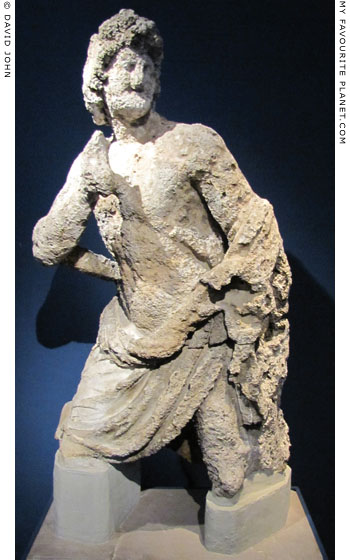

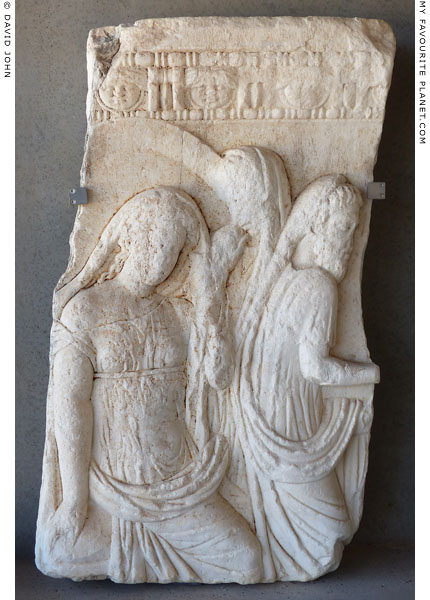

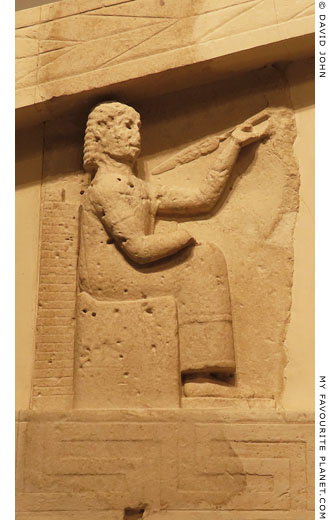

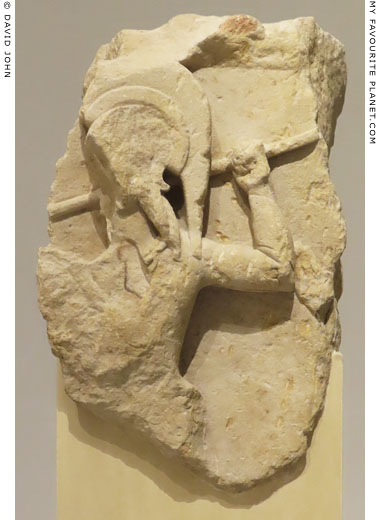

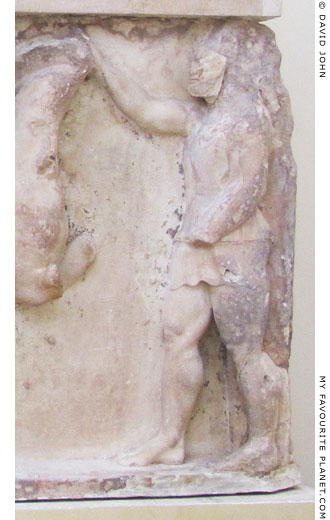

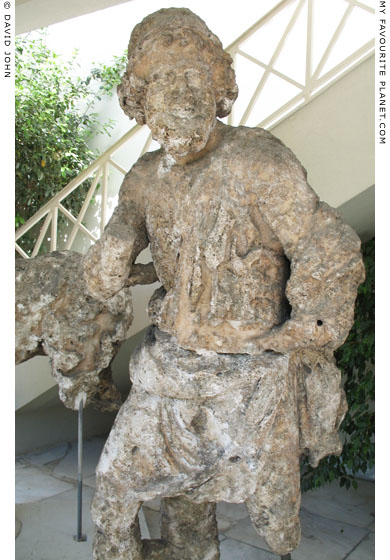

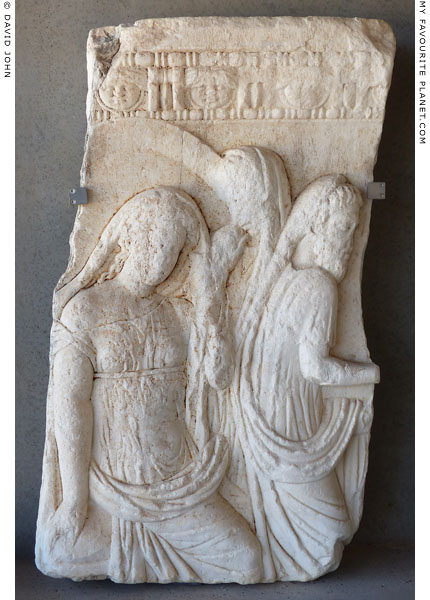

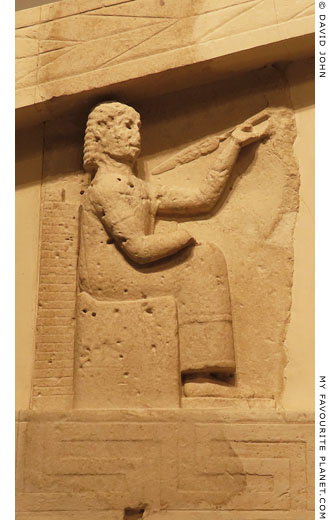

A fragment of a limestone slab with a relief of a warrior

(described by the museum label as a "hoplite"), found

near "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu (see Medusa part 3).

Perhaps part of a metope or frieze from the first

building phase of the temple, circa 590-570 BC.

Height 73 cm, width 46 cm, depth of relief 10.5 cm.

The figure is viewed from behind, facing left with his

head in profile. He wears a crested Corinthian helmet

and aims a spear in his raised right hand. Achilles

fighting Memnon has been suggested as the subject.

To the right of his elbow is part of the right hand of

another figure. Since Memnon is thought to stand to

the right of Achilles in other depictions of the duel,

with the combatants flanked by their respective

mothers, the warrior may be Memnon and the hand

that of his mother Eos.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1982.

See another relief from the temple in Corfu,

thought to depict the death of Priam, below. |

|

| |

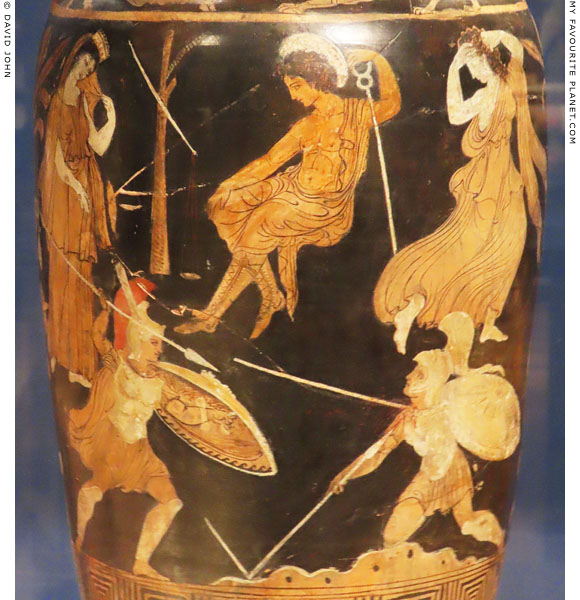

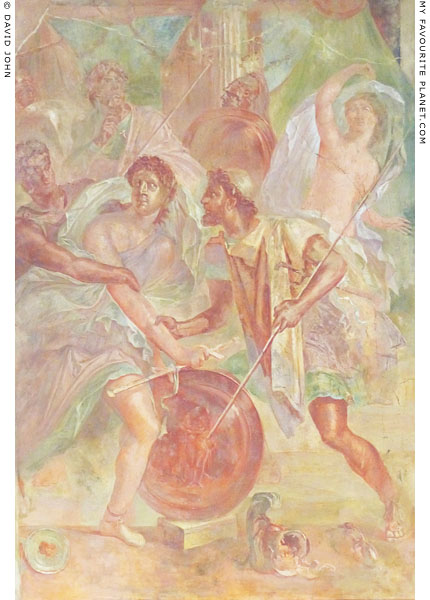

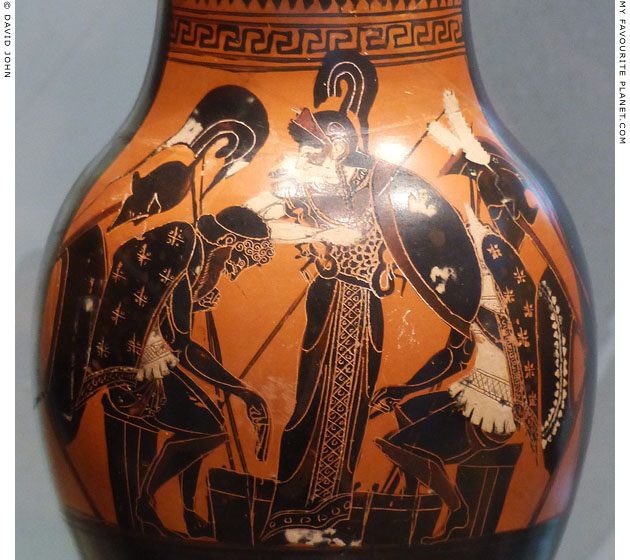

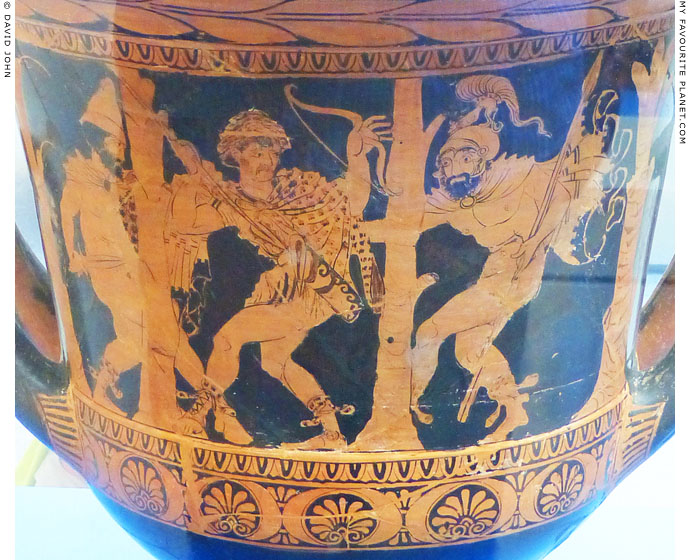

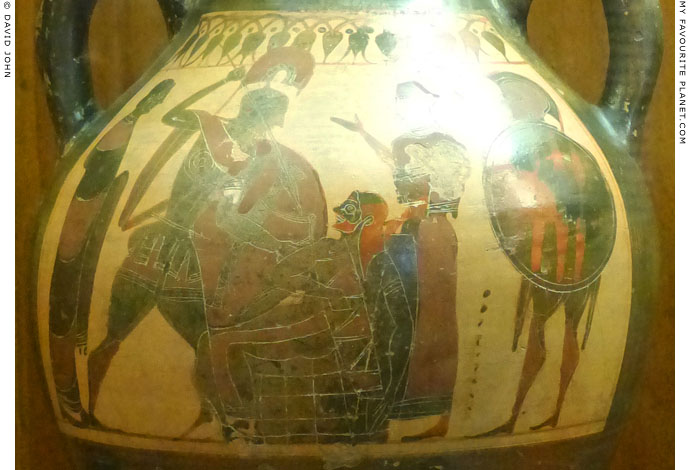

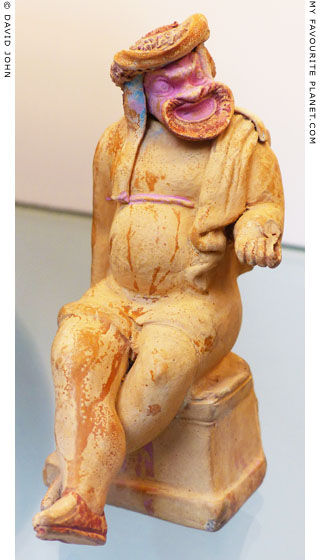

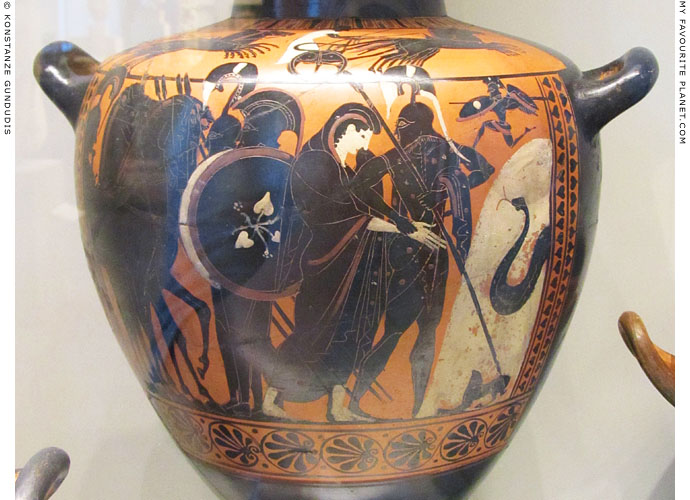

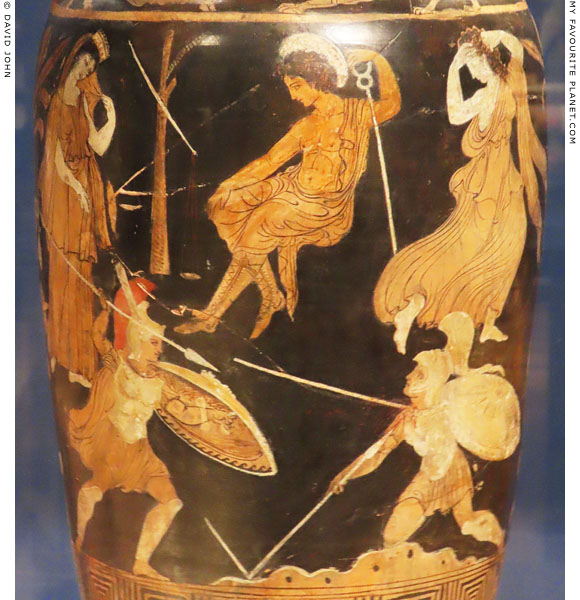

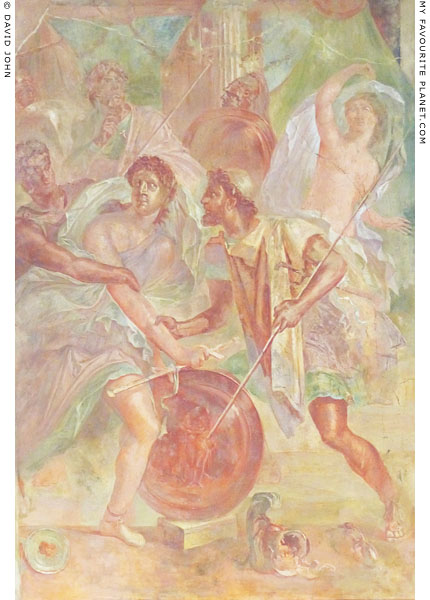

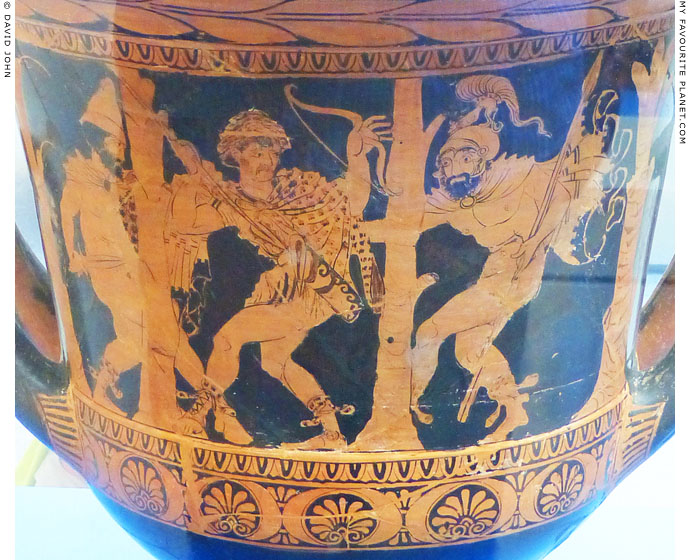

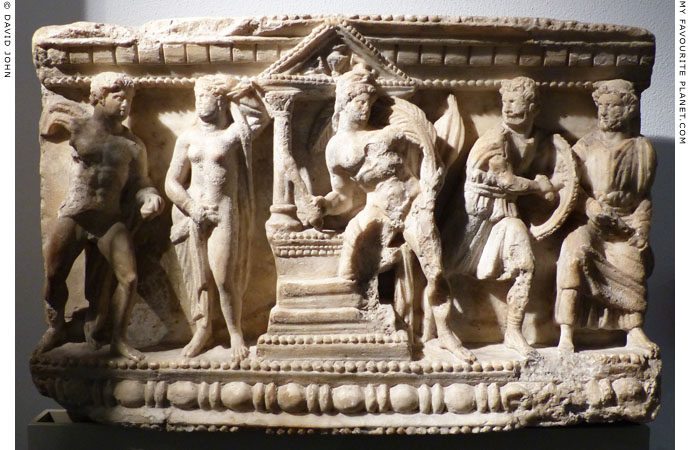

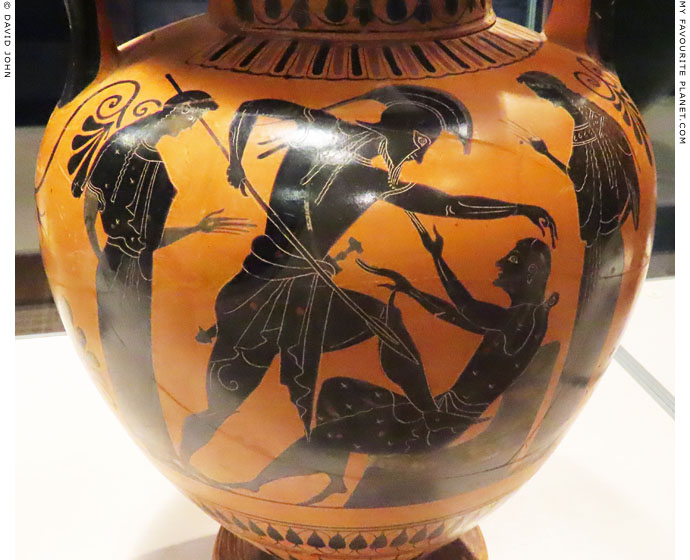

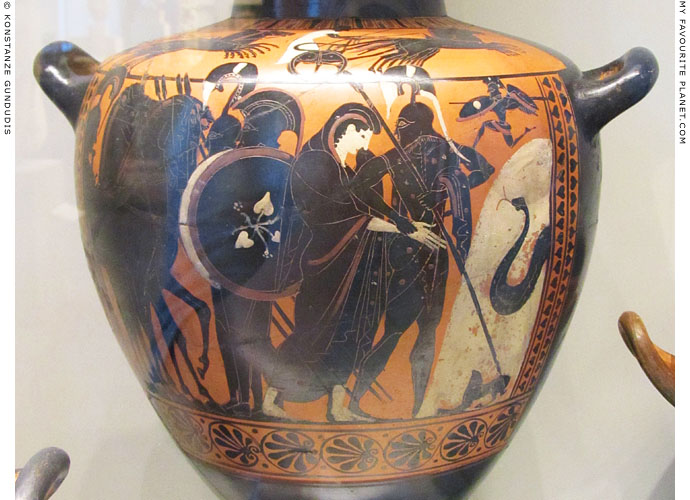

Achilles fighting the Ethiopian king Memnon on

the body of a red-figure Campanian amphora.

From Campania, southwestern Italy, 330-320 BC.

The amphora was made during the period of warfare between the Greek colonies in

Magna Graecia (southern Italy) and the Italic Samnite tribes. The Greek hero Achilles

(left) is shown in Greek armour, while the barbarian Memnon wears Samnitic armour.

Memnon has fallen to his knees, and his mother Eos, shown above him, is evidently

distraught, while Thetis, the mother of Achilles, appears serene. Hermes, holding

his kerykeion (caduceus), sits between the two mothers and watches the duel.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden. |

| |

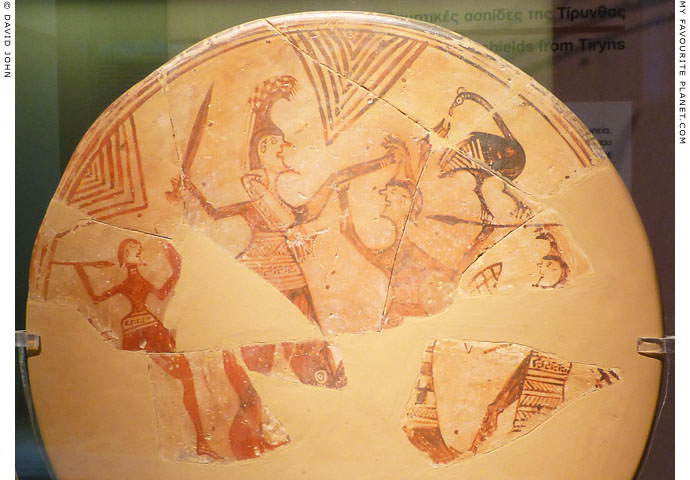

A ceramic plate with a depiction of Menelaos and Hektor fighting over the body of the Trojan hero

Euphorbos (Εὔφορβος), who Menelaos has just killed (Homer, Iliad, Book 17, lines 60-80).

The names of all three characters are inscribed in Argive lettering next to the figures.

Made on Kos, Dodecanese, about 600 BC.

From Kamiros, Rhodes. Diameter 39.37 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1860.4-4.1. Purchased in 1860. |

| |

Detail of a black-figure column krater with a depiction a Homeric duel: two warriors

fighting over the body of a third. On either side is a pair of fighting warriors.

Such scenes depicted in Greek pottery painting include Menelaos and Hektor

fighting over Euphorbos (see above), and Ajax and Hektor fighting over Patroklos.

One of two similar kraters displayed together unlabelled in the Kavala museum

(see the other below). So far I have found no further information about them.

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia, Greece. |

| |

A battle scene around the outside of an Attic black-figure kylix (drinking cup), with

three duelling pairs of warriors on each side, all naked apart from helmet and shield.

What may appear to be inscriptions next to the figures are merely rows of dots.

Around 550-540 BC. Provenance unknown, but probably from Halkidiki, Macedonia, Greece.

Polygyros Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ82. From the Lambropoulos Collection. |

| |

The reconstructed fragments of the pediment and frieze from the east side of the

Siphnian Treasury in Delphi, built for the people of Siphnos around 530-525 BC

(before 524 BC), High Archaic period. The theme of the frieze relief is the Trojan War.

Height of frieze 64 cm, length 6.2 metres. Height of pediment (centre) 74 cm.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

|

The entablature of the Ionic treasury was decorated with a frieze on all four sides, each with a long relief depicting a mythological theme. Above the back of the building on the east side, the pedimental relief, several parts of which have survived, depicts Zeus intervening in the struggle between Apollo and Herakles when the latter attempted to steal the oracular tripod from Apollo's temple at Delphi (see reconstruction drawing below).

The theme of the frieze relief below the east pediment is the Trojan War, divided into two scenes. The scene on the left (south) side is an assembly of the Olympian gods. Those who supported the Trojans are seated on the left (Ares, Aphrodite, Artemis and Apollo, see photo below), and those who sided with the Achaeans (Greeks) on the right (Athena, Hera and Demeter, see photo below). The supreme god Zeus is enthroned in the centre, and a now missing part of the scene is thought to have shown the figure of Thetis, the mother of the Greek hero Achilles, pleading with Zeus for her son's safety (see above).

The scene on the right (north) side of the relief shows a battle around the body of a fallen warrior between Trojans, fighting from the left and Achaeans (Greeks) on the right (see photo below). On the far right, the elderly Nestor (Νέστωρ, identified by a painted inscription) urges the Achaeans on (see photo, right).

Identifications of the characters in the relief are those on the museum labels. Their names were originally painted next to the figures, but most are now partly or wholly illegible. A number of scholars have attempted to reconstruct the inscriptions and identify the figures, leading to much conjecture and debate.

The unknown sculptor of the frieze reliefs on the north and east sides of the Siphnian Treasury has been named "Master B", while the artist who made the south and west reliefs is known as "Master A". See the Aristion of Paros page for further details. |

|

The figure of Nestor, king of Pylos and the

oldest of the Greek heroes at Troy, on the

right edge of the frieze relief from the east

side of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi. |

|

| |

A reconstruction drawing of the east pediment and frieze of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. |

| |

Detail of the assembly of the gods scene on the left side of the frieze relief from

the east side of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi, around 525 BC (see above).

The seated deities in this fragment have been identified as (left-right):

Ares (with shield), Aphrodite, Artemis, Apollo and Zeus.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

|

The assembly scene has survived as two fragments, with the centre now missing. In the left-hand fragment the four deities who supported the Trojans sit facing right. Apollo turns around to face Aphrodite and his twin sister Artemis who are gesturing dramatically with their arms. They appear to be engaged in a lively discussion.

In the centre of the scene, Zeus sits on a throne with armrests supported by small figures, in a similar way to Caryatids. It is thought that he is listening to the plea of the Nereid (sea nymph or sea goddess) Thetis (Θέτις) to protect her son Achilles from his prophesied death in the Trojan War. The part of the relief in which she is believed to have sat or stood is now missing. The supplication of Thetis is known to have been depicted in other ancient Greek artworks (see above), and various events surrounding her marriage to Peleus were to provide the causes of the war (see Hermes and Hephaistos). She also plays an important role in the story of the war due to her constant efforts to protect Achilles, the central character of The Iliad.

According to one theory, based on the interpretation of a faint and fragmentary inscription, the figure identified as Aphrodite may be Eos, the mother of the Ethiopian king Memnon, an ally of the Trojans. Like Thetis, Eos is also said to have petitioned Zeus for the safety of her son in the Trojan War. It has also been suggested that Poseidon may have been shown enthroned facing Zeus, and that Achilles may have also appeared in the centre of the scene.

To the right of this group, another fragment shows three goddesses facing left, identified as Athena, Hera and Demeter, who are also gesticulating with their arms (see photo below). These three sided with the Achaeans (Greeks) and are probably arguing in favour of Thetis' entreaty. The entire scene resembles a debate in a council or law court in which two sides attempt to influence the decision of the judge.

In a broader context, the two scenes on the frieze relief represent the two worlds - the realm of the gods and that of mortals - which collide in and around the Trojan War as related by Homer and other authors of the Epic Cycle. The dealings of the various gods, acting according to their characters and complex relationships with each other, eventually have consequences for mortals. In turn the actions of men and women often provoke the deities to intervene in their lives, thus causing a cycle of seemingly inevitable and inescapable events, often tragic, which have been interpreted as comprising destiny or fate. This theme was to provide the Greek tragedians of the Classical period with the core of their plays. The appearance of mythological themes in Greek art and literature, and particularly on sacred buildings, demonstrates how legends and folk tales became deeply interwoven with religious beliefs and affected the lives and thoughts of the Greeks. |

|

| |

The right-hand fragment of the assembly of the gods relief scene, from the east side of the frieze of

the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi. Three seated goddesses, identified as Athena, Hera and Demeter.

The identification of Hera appears certain. According to interpretations of the fragmentary

inscription near the right-hand figure, usually identified as Demeter, she may be Thetis or

Themis. Although the two goddesses on the right can not now be identified by attributes,

Athena is clearly wearing her trademark snake-tasseled aegis (see Medusa part 6).

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. |

| |

Detail of the battle scene on the right side of the frieze relief from the east

side of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi, around 525 BC (see above).

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

|

Two Trojans on the left face two Achaeans (Greeks) on the right, between them lies a dead warrior. Each of the warriors wears a crested helmet and a cuirass (breastplate) over a short chiton (tunic), carries a round shield and brandishes a spear. Either side of the combatants stands a chariot driver behind four horses, which have presumably delivered the fighters to the battle. The chariots are not represented in the sculpture, but may have been drawn or suggested in paint and perhaps with metal attachments. Traces of paint, particularly red, are still visible.

Since the left hand scene of the relief is thought to represent a specific event, Thetis at an assembly of gods (see above), this scene may well depict a particular battle during the Trojan War. However, the subject is not obvious (at least to the modern viewer) and is open to debate. Was this a fight between four warriors, or part of a larger action, or did the artist abbreviate a more substantial battle, reducing the number of figures due to the confines of space on the frieze?

The identity of the warriors is thus also uncertain. As can be seen in the vase paintings above, a number of fights were depicted taking place over the body of a fallen comrade. Given the appearance of Thetis in the left-hand scene, it may not be too far-fetched to assume a thematic unity in the relief and see Achilles as one of the Achaeans here. The shield of the foremost Achaean is decorated with a Gorgoneion (see Medusa part 6). A Corinthian black-figure hydria, dated around 560-550 BC and now in the Louvre (Inv. No. E 643), shows Thetis and the Nereids mourning over the body of Achilles. Beside the bed on which his corpse has been laid out is a Corinthian helmet with a transverse crest (see Medusa part 6) and a round shield with a Gorgoneion device. This of course, is not evidence that ancient Greeks associated him with such a shield.

According to one theory, partly based on an interpretation of the faint and incomplete painted inscriptions, the figures (left to right) are: Glaukos (charioteer), Aineas, Hektor, dead Sarpedon (a son of Zeus), Menelaos, Patroklos, Automedon (charioteer) and Nestor. |

|

| |

Detail of an Attic black-figure hydria (water jar) showing the chariot of the Trojan prince Hektor (Ἕκτωρ),

the eldest son of King Priam and crown prince of Troy. The charioteer Kebronius stands in the quadriga

(four-horse chariot), and Hektor stands to the left. The names of both figures are inscribed to the right of

their heads. A youth with a spear stands right of the chariot. They are flanked by two warriors in armour.

Made in Athens around 580 BC. Attributed to the Painter of London B76,

who is named after this vase. From Kamiros, Rhodes.

British Museum. GR 1861.4-25.43 (Vase B 76).

See: Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 300790 |

| |

Detail of a black-figure column krater with a depiction a youth in a four-horse chariot.

On either side is a pair of armoured warriors with round shields.

One of two similar kraters displayed together unlabelled in the Kavala museum

(see the other above). So far I have found no further information about them.

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia, Greece. |

| |

The front of a Roman marble sarcophagus (a free-standing stone

coffin; from the Greek, σαρκοφάγος, flesh-eater) with mirrored

reliefs depicting Achilles with his tutor Cheiron at either end.

2nd half of the 3rd century AD. Found in 1946 on the Via Casilina,

in the area of Torraccia, Rimini province, northeast Italy.

Cloister, Baths of Diocletian,

National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 124735.

|

In the centre is an imago clipeata (a portrait in a round frame) of the deceased youth, held by two flying winged erotes and supported by an eagle with outspread wings, which is flanked by the reclining river and ocean god Oceanus (Ὠκεανός, Okeanos) and Tellus Mater (Mother Earth, the Roman equivalent of the Greek Gaia, Γαῖα). Each of the erotes looks behind him towards Achilles and Cheiron at his end of the relief. On either side of the sarcophagus is a relief of a seated griffin (γρύφων, gryphon) which fills the entire surface.

As a boy Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς) was sent by his father Peleus (Πηλεύς) to be raised by the Centaur Cheiron (Χείρων), a kinsman who lived on Mount Pelion (Πήλιον) in Thessaly. Among the skills Achilles learned from Cheiron were medicine (see photo, right and below) and music. Their relationship is mentioned in The Iliad (Book 11, line 830; Book 16, line 140; Book 19, line 387) and by several other ancient authors. [1]

As in other depictions of Achilles and Cheiron in Greek and Roman art, Achilles holds a lyre, and in this case also a plectrum. The boy is shown in heroized nudity, wearing only a cloak that covers his chest and shoulders. He looks at Cheiron, and they appear to have eye contact. Seated very close to him, the Centaur stretches one arm across the boy's chest to point to the lyre, indicating that he is instructing him, but it appears almost as an embrace.

Cheiron was said to have also been the tutor of other Greek heroes, including Herakles, Jason, Theseus and Asklepios. It was near the Centaur's cave on Mount Pelion that the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (Θέτις, Achilles' mother) took place (see Hephaistos). Eris (Ἔρις), the goddess of Discord, was not invited to the wedding, but turned up anyway and caused a chain of events which led to the Trojan War (see Hermes). |

|

The name ΧΕΡΩΝΟΣ (Xeronos, of Cheiron)

inscribed in the Achaean alphabet on a

sandstone horos (boundary stone; Latin,

cippus) from Paestum (Παῖστον; earlier

Poseidonia, Ποσειδωνία), Campania,

southern Italy (Magna Graecia).

Around 550 BC, Archaic period.

Found 25 metres east of the altar

of the Temple of Hera at Paestum.

Along with other evidence, the inscription is

thought to indicate that there was an area

for the cult of the Centaur Cheiron in the

Southern Sanctuary of Poseidonia, and

that since the city's foundation part of the

sanctuary had been dedicated to cults in

some way connected with medicine.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum,

Campania, Italy. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Achilles and Cheiron at the ends of the sarcophagus relief in the Baths of Diocletian. |

|

| |

Achilles among the daughters of Lykomedes on Skyros.

A modern copy of a Roman fresco found in the tablinum of the

House of the Dioscuri (Casa dei Dioscuri, Regio VI, Insula 9, 6-7),

Pompeii. Circa 62-79 AD. Height 130 cm.

Studiendepot, Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden.

|

The original fresco is in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 9110.

The story of Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς) at the court of Lykomedes (Λυκομήδης), king of Skyros, does not appear in The Iliad, but was related in later versions of tales of the Trojan War, including The Achilleid, an epic poem written by the Roman poet Statius in the 1st century AD.

As a boy Achilles was sent by his mother Thetis (Θέτις) to the Sporadic island of Skyros (Σκύρος), because it had been prophesied that he would be killed in war. Lykomedes concealed Achilles by disguising him as a female and placing him among his daughters. Achilles had an affair with Deidamia (Δηιδάμεια), one of the daughters, and they had a son, Neoptolemos (Νεοπτόλεμος, New Warrior, also known as Pyrrhos, Πύρρος, Red, because of his red hair).

The painting, one of several surviving ancient depictions of this scene, shows the moment in which Diomedes (far left) and Odysseus (right) discover Achilles in his disguise. Cunning Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) organized a fake attack on Lykomedes' palace, and when Achilles instinctively reached for his arms his cover was blown. Lykomedes, a guard and Deidamia can be seen in the backgound. Odysseus then persuaded Achilles to fight at Troy. Neoptolemos remained on Skyros, but later also fought in the war.

On the round shield is a relief of the young Achilles and Cheiron, depicted in the same way as on the sarcophagus above.

One of the most striking depictions of the scene is depicted in relief on a panel from a Roman marble sarcophagus, circa 240 AD, now in the Louvre. Inv. No. Ma 2120.

Pausanias mentioned that a painting of this episode by Polygnotus (Polygnotos of Thasos?) was displayed in the Pinakotheke of the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis.

"I think too that he [Homer] showed poetic insight in making Achilles capture Scyros, differing entirely from those who say that Achilles lived in Scyros with the maidens, as Polygnotus has represented in his picture."

Pausanias, Description of Greece Book 1, chapter 22, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny the Elder wrote that Athenion of Maronea, a pupil of Glaucion of Corinth, had also painted this episode: "... an Achilles also, concealed in a female dress, and Ulysses detecting him" (Natural history, Book 35, chapter 40, at Perseus Digital Library). |

|

| |

Mosaic panel of Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς) affronting Agamemnon (Ἀγαμέμνων), illustrating

a scene from Homer's Iliad, Book I. The angry Achilles draws his sword to attack

Agamemnon, seated left. Athena restrains him by seizing him by the hair.

From the House of Apollo (Casa di Apollo, Regio VI, Insula 7, 23), Pompeii.

Height 92 cm, width 110 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 10006. |

| |

Achilles binds Patroklos.

Tondo on the inside of an Attic red-figure kylix (κύλιξ, stemmed drinking cup),

made by the potter Sosias and painted by the Sosias Painter.

Around 500 BC. Signed by the potter Sosias on the rim of the foot: Σοσιας εποιεσεν

(Sosias epoiesen, Sosias made [me]). It is the name vase of the Sosias Painter.

Found by Fossati in 1828 in the Necropolis Campo Scala, Vulci, Etruria (Lazio, Italy).

Height 10 cm, diameter (mouth) 32cm, diameter of tondo 17.5 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. F 2278. Acquired in 1831.

Formerly in the Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin.

|

A scene from the Trojan War. Achilles, who had learned the art of healing from the Centaur Cheiron (see above), binds the arrow wound of his friend Patroklos who is in great pain. The names Πατροκλος (Patroklos) and Αχ[ι]λλευς (Axilleus), inscribed above the figures, are now hardly visible. The painting on the outside of the cup depicts the Apotheosis of Herakles: Athena presenting her protegé Herakles to an assembly gods (named by inscriptions) on Mount Olympus (see Ancient Greek artists – page 10).

The signature on the profile of the foot of the kylix is thought to be that of the potter Sosias, and the painter was named the Sosias Painter by the art historian John Beazley. Other scholars have attributed the painting to the Kleophrades Painter (Robertson) or Euthymides (Ohly-Dumm). |

|

| |

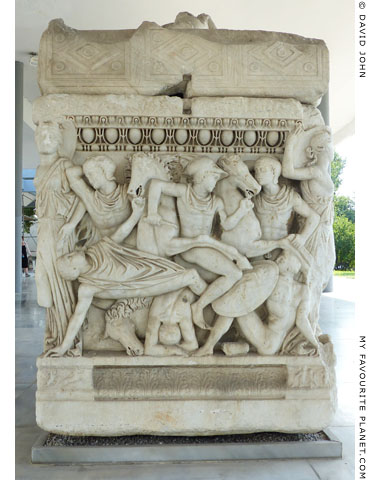

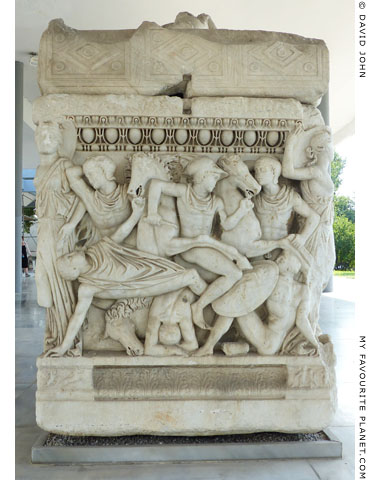

A relief depicting the Epinausimache, the fight at the ships between Greeks and Trojans

(Iliad, Book 13 onwards), on the front of a Neo-Attic marble kline sarcophagus from Thessaloniki.

Made in Athens in the Neo-Attic style of the Roman Imperial period, mid 3rd century AD,

in imitation of Classical and Hellenistic sculpture. Found 1929 in the Roman necropolis

in the Mevle-Hane district (Μεβλε Χανε), on the Langada road, northwestern Thessaloniki.

Pentelic marble. Height 143.5 cm, width 236 cm, depth 99 cm.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1246.

|

The Epinausimache, the fight at the ships, is the name given to the episode in The Iliad when a Trojan counter offensive led by Hektor (Ἕκτωρ) forced the besieging Greeks to fall back to their encampment around their ships on the shore and a battle ensues. The description of the ferocious hand-to hand fighting between the two armies takes up much of the third quarter of The Iliad from chapter 13 onwards. The dominant warrior in the centre may be Hektor killing Periphetes (Περιφήτην), a hero from Mycenae (Iliad, Book 15, lines 637-652). Behind them other Greek warriors stand in two ships, in front of which are sea deities. It has often been pointed out that the Amazon on horseback on the left half of the relief should not be there, since at this phase of the war the Amazons had not yet arrived at Troy (see below).

This is one of two similar, large marble Neo-Attic kline sarcophagi now standing in front of the main entrance to the Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. The other (Inv. No. 1245) has a relief of an Amazonomachy (battle between Amazons and Greek) on the front. The two are among the largest surviving Roman sarcophagi in the world.

Attic sarcophagi were produced in Athens, mainly for export, made of Pentelic marble quarried at nearby Mount Pentelikos. Thessaloniki also produced sarcophagi which were not so elaborately sculpted, and presumably not as expensive as the imported coffins.

Kline sarcophagi are so called because they are in the form of a kline (κλίνη, couch, chaise longue). The separate lid is sculpted to resemble a mattress on which a sculpture of the deceased person or couple reclines as if enjoying a symposium (συμπόσιον, symposion, dinner or drinking party). The upper torsos of the figures are usually supported by the left elbow, and often they hold a cup or some other object in their right hand. The front, sides and sometimes back of the marble coffins in which one or more corpses were deposited, were decorated with reliefs, often depictions of mythical episodes.

On this sarcophagus reclines a now headless couple, with the woman lying in front of the man. Their left elbows rest on pillows, and in his left hand the man holds a scroll which lies on his pillow. The edges and corners of the mattress are decorated with small, shallow reliefs of mythical figures. The coffin has good quality reliefs on all four sides: as well as the Epinausimache on the front, there is another fight scene on the short left side (see photo right); on the right side the Thracian bard Orpheus plays his lyre to wild animals (see History of Thrace); on the long rear side is a scene from the myth of the hunt of the Kalydonian Boar (see Olympiada gallery page 2). While the other three reliefs are in good condition, this last relief is damaged, particularly in the centre. |

|

The battle relief on the left side of the sarcophagus. |

|

| |

Detail of a black-figure amphora with a depiction of the Greek hero Achilles

(Ἀχιλλεύς) fighting the Amazon queen Penthesileia (Πενθεσίλεια).

Made in Athens about 540-530 BC. Attributed to the painter Exekias.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. GR 1849.5-18.10 (Vase B 209).

The fight between Achilles and Penthesileia is not mentioned in The Iliad, but was told in

The Aithiopis, in which the Greek hero falls in love with the Amazon queen and regrets

killing her. One of the best known depictions of the scene is on another black-figure

amphora by Exekias, around 540 BC. British Museum. Inv. No. 1836,0224.127. |

| |

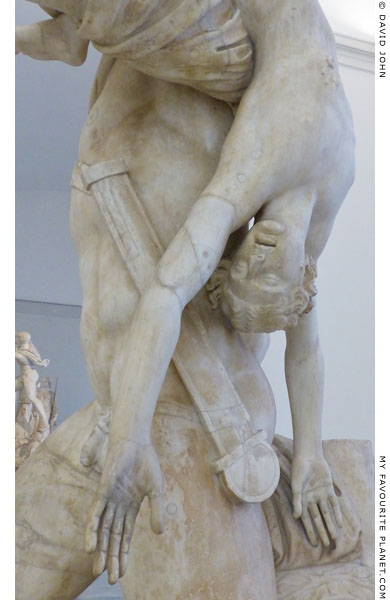

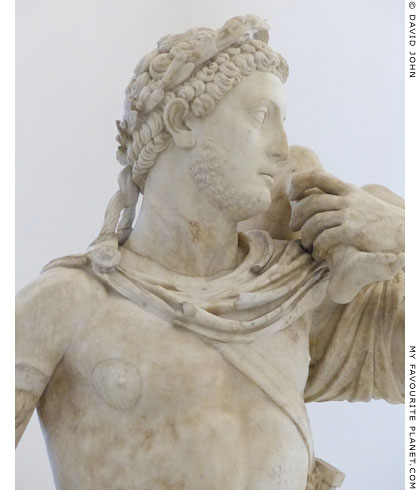

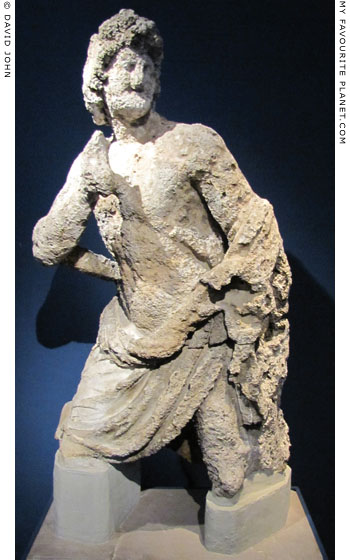

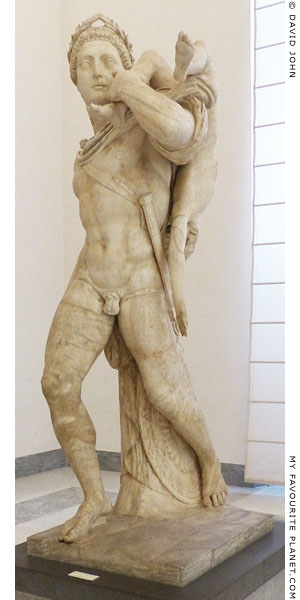

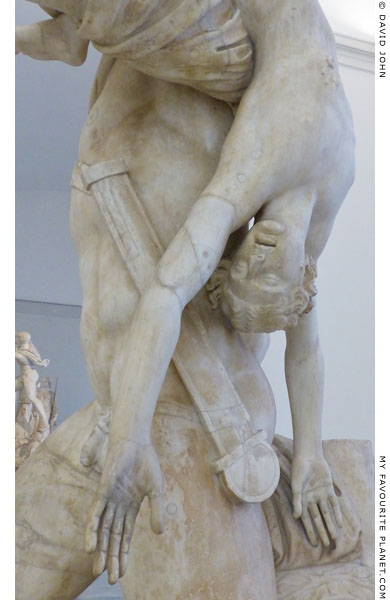

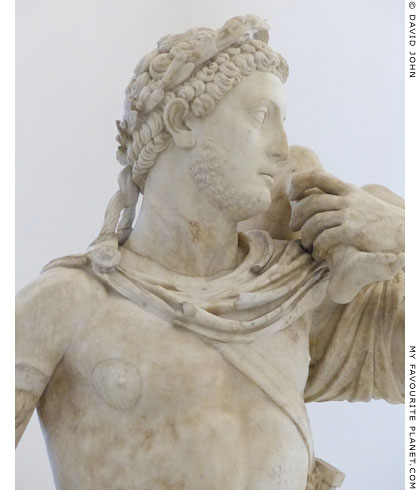

Fragment of a marble statue group of Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς) killing the

Amazon queen Penthesileia (Πενθεσίλεια), on an original ancient base.

2nd century AD, thought to be from a copy of a Hellenistic statue group

made around 250-200 BC. Found before 1912 in the Bufalotta area,

near Settebagni, Rome. White Greek marble.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 108363.

|

| The statue group is not known from ancient literature, but surviving parts of about ten copies of this type have enabled reconstructions of the entire sculpture, including E. Berger's cast reconstruction in Basel, Switzerland. This shows the nude Achilles standing and holding the body of the dying or dead Penthesileia who has fallen to her knees. One of the surviving fragments is a torso very similar to the one above, found in Aphrodisias (Ἀφροδισιάς) in Caria, western Anatolia (Geyre, Aydin, Turkey). |

|

| |

The god Hephaistos, the divine blacksmith, gives the Nereid Thetis the armour

he has made for her son Achilles during the Trojan War (Homer, Iliad, Book 18,

lines 614-615). Achilles used them to avenge the death of his friend Patroklos

by killing the Trojan prince Hektor before the gates of Troy.

The tondo on the inside of an Attic red-figure kylix (drinking cup),

made in Athens 490-480 BC. Diameter 30.5 cm.

Antikensammlung SMB, Berlin (Altes Museum). Inv. No. F 2294.

|

Known as the "Berlin Foundry Cup" (German, Erzgießerei-Schale), it is the name vase of the Foundry Painter, who is named after the scenes on the outside of the cup (Sides A and B) showing men making sculptures at a bronze foundry.

It was discovered by Campanari in Vulci, an important Etruscan city (Lazio, north of Rome), and acquired in 1837 for the Prussian Royal Collection, Berlin by Karl Josias Freiherr von Bunsen. It was previously kept in the Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin.

Achilles' quarrel with Agamemnon led him to withdraw the Myrmidons from participation in the siege of Troy. However, his close companion Patroklos went into battle wearing Achilles's armour, and was killed by the Trojan prince Hektor (Ἕκτωρ), who took the armour as booty. Thetis (Θέτις) persuaded Hephaistos to make new armour for Achilles, and she brought the splendid arms to him at Troy, where he wore it in the duel with Hektor.

On the kylix the bearded Hephaistos, wearing a short chiton (χιτών, tunic) and sitting on a cushioned stool, holds up a helmet in his left hand, and has a hammer in his right. Thetis stands to his right, wearing a cloak over a long chiton and a fillet in her hair, and holds a spear and shield. The device on the shield is a flying bird carrying a snake in its claws, surrounded by four stars, although Homer describes the decoration of the shield as being much more elaborate.

A pair of greaves (shin armour) hangs on the wall of the workshop, between the two figures. A hammer hangs on the right, and beneath it an anvil stands on a mound of earth. The "kalos inscription", running downwards (clockwise) to the right of Thetis, states: Ο ΠΑΙΣ ΚΑΛΟΣ (O PAIS KALOS, the boy is beautiful). |

|

| |

Thetis hands the armour made by Hephaistos to

her son Achilles during the siege of Troy. The shield

is decorated with a Gorgoneion and a lion's head.

The front panel of the Monteleone Chariot.

Around 575-550 BC. Bronze with ivory inlays.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Inv. No. 03.23.1.

|

The Monteleone Chariot was discovered in 1902 in an underground Etruscan tomb by Isidoro Vannozzi, a landowner at Monteleone di Spoleto, in the province of Perugia, southeast Umbria, Italy. He also found bronze, iron and ceramic grave goods in the tomb, and the artefacts were sold on to various dealers and collectors. The chariot ended up on the art market in Paris, where it was purchased in 1903 from O. Vitalini by General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the first director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Etruscan parade chariot has three panels made of bronze inlaid with ivory. The front panel is much larger than those on either side; all three are decorated with reliefs thought to depict episodes from the life of Achilles.

On the front panel (photo above), the veiled Thetis, on the left, faces a bearded Achilles, with both figures in profile. They hold a Corinthian helmet with a crest supported by a ram's head, and a large shield decorated with a Gorgoneion (head of the Gorgon Medusa) above a lion's head. Below the shield is the body of a deer on its back, and above the head of each figure a flying bird of prey descends vertically, head down.

The panel on the left side of the chariot (see image below) depicts a duel between two warriors, perhaps Achilles and the Trojan Memnon, both standing in profile over the body of a fallen warrior. Both warriors wear crested Corinthian helmets and greaves, with a spear raised in one arm and holding a shield in the other. The figure on the left has a round shield, while the shield of the figure on the right is similar to that given to Achilles on the front panel, although here the lion's head is above that of the Gorgon.

The right-hand panel depicts the the apotheosis of Achilles, with the hero ascending in a chariot drawn by winged horses. Other reliefs, over the wheels, are thought to depict Achilles as a youth with his mentor, the centaur Cheiron, and Achilles as a lion killing his enemies depicted as a stag and a bull.

See: metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247020

Source of images: Woldemar Graf Uxkull-Gyllenband, Archaische Plastik der Griechen, Band 3, Abbildungen 21 (above), 22 (below). Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin, 1920. |

|

| |

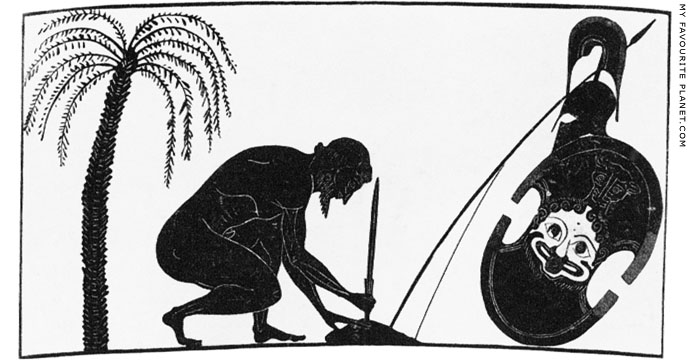

The bronze panel on the left side of Monteleone Chariot, depicting a duel between

two warriors, perhaps Achilles and the Trojan Memnon, both standing in profile over

the body of a fallen warrior. Both warriors wear crested Corinthian helmets and

greaves, with a spear raised in one arm and holding a shield in the other. The figure

on the left has a round shield, while the shield of the figure on the right is similar

to that given to Achilles on the front panel of the chariot (see above), although

here the lion's head is above that of the Gorgon. |

| |

An Attic black-figure plate with a depiction of Achilles putting on the armour

made for him by Hephaistos, in the presence of (left to right) his father Peleus,

his mother Thetis and his son Neoptolemos. All their names are inscribed.

Around 560-540 BC, painted by Lydos. From Vari, Attica. Diameter 26.5 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 507. |

| |

Achilles receiving his armour from his mother Thetis.

Detail of an Attic black-figure olpe (wine jug), about

520 BC. Comparable to the Louvre F535 Painter.

The naked Greek hero, facing right, bends forward to put a greave on his left shin.

A crested Corinthian helmet lies on the ground between his legs. He is watched by

Thetis, to the right, who holds a shield and two spears. Behind her stands a man

wearing a tall cap and a quiver or pouch. To the left stand two armed warriors.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 13.346. |

| |

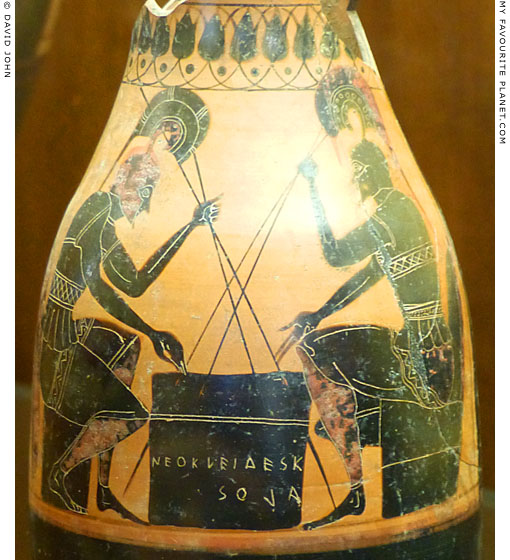

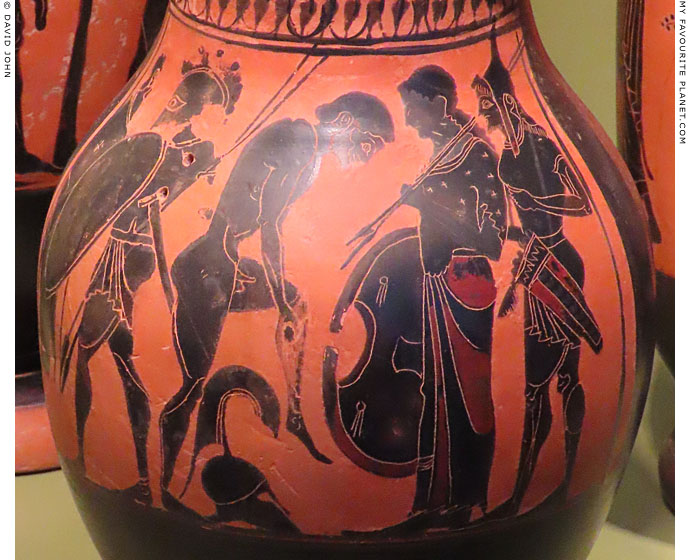

Achilles and Ajax playing a board game.

Detail of an Attic black-figure olpe (jug), about 530 BC. The inscription,

incised on the side of the table: Νεοκλειδες καλος (Neokleides kalos,

Neokleides is beautiful), with the last four letter written backwards.

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC6.

|

The two figures sit facing each other on low, block-like seats, with a small table between them. Each has one leg drawn back, holds two spears and wears armour: a high-crested Corinthian helmet, a corslet over a short tunic and greaves (shin plates). The figure on the left bends further forward with his hand touching the board, as if he is moving a game piece or waiting his turn. The other extends over-long fingers over the board, as though throwing dice or gesturing.

This is one of several surviving vases showing this scene, the best known and probably earliest being the highly detailed Attic black-figure amphora signed by Exekias, made in Athens around 530 BC, now in the Vatican Museums, Rome. [2]. The inscriptions on the amphora name the players and even the score, with Achilles sitting on the left and winning the game 4 to 3.

The scene on the olpe is bold and clear, but painted in a much simpler manner. Although the general composition is the same as that of the Exekias amphora (and other vases of the type), it differs in several ways and lacks the fine drawing, dramatic tension and exquisite detailing.

There have been a number of suggestions about exactly which game they are playing, including an early form of backgammon, dice or knucklebones. Homer makes no mention of the heroes playing a game during the Trojan War, and there are no known references to such a scene in literature from this period.

On a game-board (Εis τάβλαν)

"Seated by this table made of pretty stones, you will start the pleasant game of dice-rattling. Neither be elated when you win, nor put out when you are beaten, blaming the little die. For even in small things the character of a man is revealed, and the dice proclaim the depth of his good sense."

Epigram by Agathias Scholasticus (circa 530-582/594 AD) [3] |

|

| |

A black-figure painting of Achilles and Ajax playing a board game. The poses

of the armoured warriors are the same as in the painting above. Each player

holds two spears, wears a himation as a cloak, suggesting a cool day or

evening outside the walls of Troy. Their crested Corinthian helmets are

perched on the top of the head so that their bearded faces are visible.

Detail of an Attic "bilingual" neck amphora, made in Athens around 520 BC.

This black-figure painting is attributed to the Lysippides Painter. On the

other side of the vase (Side A) is a red-figure scene of Herakles fighting

the Nemean Lion attributed to the Andokides Painter.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1851.8-6.15 (Vase B 211). |

| |

Another vase with Achilles and Ajax playing a board game, here with Athena as spectator.

The players' Corinthian helmets and round shields are hung behind them. Athena stands

in front of the table between the seated figures. Her head is turned to the left. She wears

a high-crested Attic helmet and the snake-fringed aegis, and carries a spear and round

shield. Oddly, her left elbow is shown behind the head of the player on the left, while her

shield is in front of the other player, obscuring his head.

Detail of an Attic black-figure oinichoe (jug), 550-501 BC.

Attributed to the Painter of Oxford 224.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1885.653. Ex-Castellani Collection. |

| |

Fragment of a relief skyphos with a depiction of a scene from

The Iliad featuring Ajax and Achilles whose names are inscribed.

2nd century BC. Found at 4 Karbola Street, Thessaloniki.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MΘ 9972.

See also a fragment of a relief skyphos with a scene from The Odyssey in Homer part 3. |

| |

Odysseus (left) and Diomedes (right) ambush the Trojan spy Dolon (Δόλων),

who wears a wolf skin and a ferret skin cap and carries a bow and spear.

A scene taken from Homer's Iliad, Book X.

Detail of a red-figure calyx krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) made in Lucania,

southeast Italy around 390-380 BC. The name vase of the Dolon Painter.

From Pisticci, Matera, Basilicata, southeast Italy. Height 50.8 cm, diameter 48.26 cm.

British Museum. GR 1846.9-25.3 (Vase F157). Steuart Collection.

|

The figures, cleverly framed by the trunks of four trees, are shown in exaggerated, theatrical poses: Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) and Diomedes (Διομήδης) and creep on tiptoe to surprise Dolon (centre). The representation of the scene may have been inspired by a comedy play.

The Trojan Dolon, son of the wealthy herald Eumedes, is described by Homer as being ugly but a fast runner. He offered his services as a spy to Hektor in return for the horses and chariot of Peleus (Πηλεύς, father of Achilles). Having struck the bargain, he set off at night on his mission:

"Forthwith then he cast about his shoulders his curved bow, and thereover clad him in the skin of a grey wolf, and on his head he set a cap of ferret skin, and grasped a sharp javelin, and went his way toward the ships from the host; howbeit he was not to return again from the ships, and bear tidings to Hector."

Homer, Iliad, Book 10. At Perseus Digital Library.

The bow, wolfskin cloak, ferretskin cap and spear are matched in the vase painting.

Odysseus saw Dolon approaching, and with Diomedes lay among the corpses of battle to ambush him. After they captured him, he blurted valuable information about the Trojans and their allies to save his own skin, including the location of the camp of the Thracian king Rhesus (Ῥῆσος, Rhesos, see note on the Dioskouroi page), his strong white horses, chariot of silver and gold and golden armour. Diomedes killed Dolon by cutting off his head with a single stroke of his sword (although he is carrying two spears in this vase painting, his right hand is hidden behind Dolon's body), and Odysseus hung Dolon's ferretskin cap, wolfskin cloak, bow and spear on a tamarisk tree as an offering to Athena, "the goddess of plunder". They then raided the camp of Rhesus, killed him and other Thracians and stole their horses. |

|

| |

The Greek hero Diomedes (Διομήδης) steals the Palladion (Παλλάδιον; Latin, Palladium), an

ancient statue of Pallas Athena which protected Troy. He is naked apart from a wreath and

a cloak. A helmet (?) hangs behind his shoulders. He runs from the temple of the goddess,

passing a flaming altar, holding the Palladion in his left hand and a sword in the right.

The tondo of an Attic red-figure stemless cup. Made in Athens around 380 BC. From Apulia.

Attributed by Sir John Beazley to either the Diomed Painter or the Jena Painter, who may

have been the same person. He/they may have shared a workshop with the Q Painter.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1931.39.

See: Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 231038.

Debate continues about the identity of the protector goddess of Troy and the surrounding area of northwestern Anatolia before the arrival of the Greeks. Pallas may have originally been a local Anatolian deity, who the Greeks identified with Athena (as Pallas Athena, Παλλὰς Ἀθηνᾶ), in the way that worship of the prehistoric mother goddess of Ephesus (akin to Kybele) was assimilated by the Ionian Artemis cult.

Pausanias reported that a depiction of Diomedes stealing the statue was among the paintings, already by his time considered very ancient, in "a building with pictures" on the the left (north) side of the Propylaia, the Classical entrance to the Athenian Acropolis. This room still exists (although not the pictures), and has become known as the "Pinakotheke" (Πίνακοθηκη, picture gallery) after Pausanias' description.

"On the left of the gateway is a building with pictures. Among those not effaced by time I found Diomedes taking the Athena from Troy, and Odysseus in Lemnos taking away the bow of Philoctetes [see below]. There in the pictures is Orestes killing Aegisthus [see Homer part 3], and Pylades killing the sons of Nauplius who had come to bring Aegisthus succor. And there is Polyxena about to be sacrificed near the grave of Achilles [see below]. Homer did well in passing by this barbarous act. I think too that he showed poetic insight in making Achilles capture Scyros, differing entirely from those who say that Achilles lived in Scyros with the maidens, as Polygnotus [Polygnotos of Thasos?] has represented in his picture [see above]. He also painted Odysseus coming upon the women washing clothes with Nausicaa at the river, just like the description in Homer [Odyssey, Book 6]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 22, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

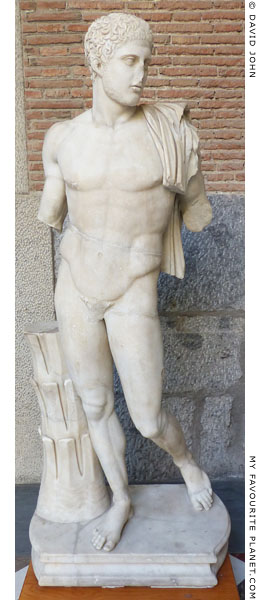

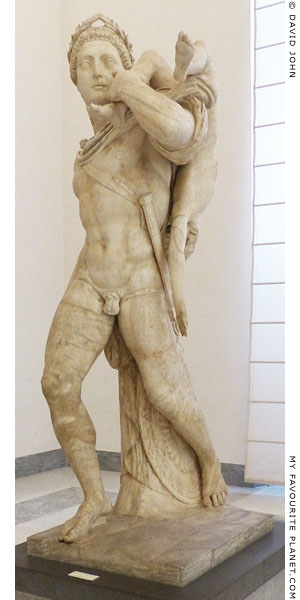

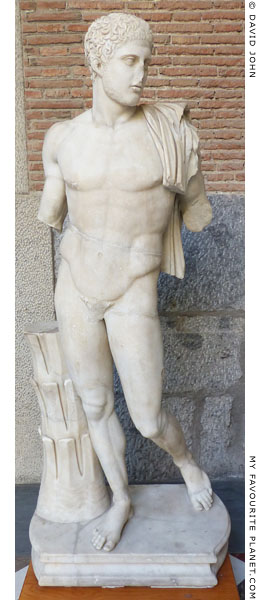

A marble statue of a naked young man,

thought to be a Roman period copy of

a statue of Diomedes stealing the

Palladion, made by the Cretan

sculptor Kresilas around 450-430 BC.

Found in the crypt below the acropolis of

Cumae in the Bay of Naples, Campania,

Italy, during excavations in 1925.

The figure, nude except for a himation

(cloak) draped over his left shoulder,

stands with his weight resting on his

right foot and a palm stump to the right

of the leg. His left leg is bent, with the

right foot, resting on the toes, behind

the torso, In his now missing hands he

probably held a sword and the Palladion.

Inscribed in Greek on the base is the

name Gaius Claudius Piso, maybe the

man who dedicated the statue, perhaps

to Apollo.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 144978. |

|

| |

One of the long sides of a small marble ossuary in the form of a sarcophagus.

Each of the four sides has a relief depicting one or more scenes. Here, on the

left, nude Diomedes carrying off the Palladion, and Odysseus. To the right,

Aphrodite and a nude hero stand either side of a war trophy.

On the opposite long side: on the left, a married couple, presumably at least

one of whose remains were contained in the ossuary; in the centre Aphrodite

writes their names on a shield held up by an infant Eros (Erotideus); on the

right, heroically nude Bellerophon with his winged horse, Pegasus.

On one of the narrow sides, a Centaur wrestles with a bearded man wearing

a short chiton (tunic). On the other narrow side, a Satyr and goat-footed Pan

support a drunken Herakles.

150-200 AD. Marble from Dokimeion, Asia Minor (Anatolia).

Made in an Asia Minor workshop. Found on Megisti (Kastellorizo).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1189. |

| |

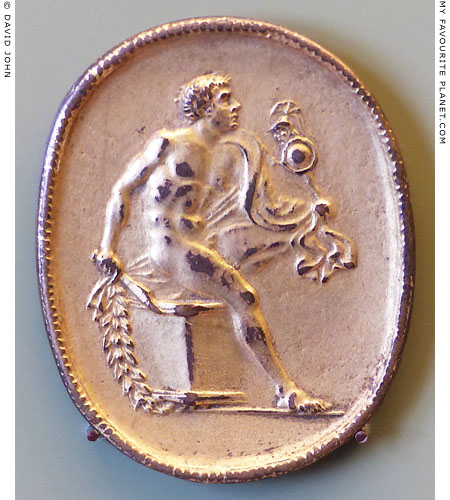

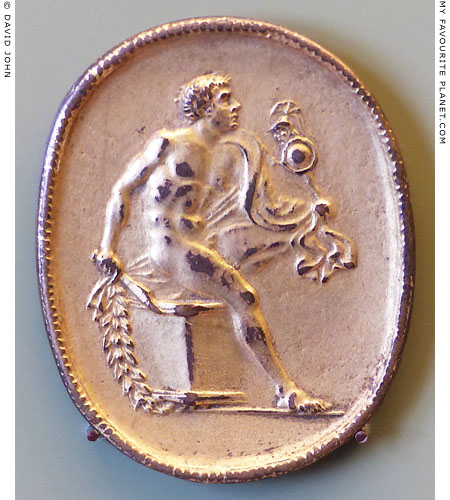

Diomedes with the Palladion on a gilded bronze plaquette.

Diomedes, naked apart from a himation (cloak) over his left shoulder

and arm, kneels as he steps or leaps over a wreathed altar, holding

the Palladion in his left hand hand and a sword in the right hand.

15th - 16th century. Probably made by a Florentine artist, after a Roman

period gem now in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 951. Acquired in 1887.

Another, almost identical but ungilded bronze medallion is also

displayed in the museum. Inv. No. 2626. Acquired in 1904.

|

There are a number of ancient gems engraved with an almost identical scene, which are among several gems with a Greek signature of Dioskourides (Διοσκουρίδης). Pliny the Elder mentioned an artist named Dioscurides (in some editions Dioscorides) among the most famed gem engravers, and said that he "engraved a very excellent likeness of the late Emperor Augustus upon a signet, which, ever since, the Roman emperors have used." (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 37, chapter 4) The ring seal of Augustus by Dioscurides was also mentioned by Suetonius (Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Lives of the Caesars, Book II, The life of Augustus, chapter 50).

A handful of the extant gems in various collections and museums are believed to be the work of this artist, while the others may be replicas or forgeries. Copies of this Diomedes motif from ancient gems have been made in various media since the Renaissance.

The gem which served as a model for this plaquette is a small engraved carnelian now in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, believed to be the one recorded as having once belonged to the humanist Niccolò de' Niccoli. It was acquired by Pope Paul II and in 1471 by Lorenzo de Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent). The Diomedes motif is still to be seen on one of the marble medallions (clipei) with reliefs replicating gems, attributed to Bertoldo di Giovanni (circa 1420-1491), on the walls around the Cortile di Michelozzo (Courtyard of Michelozzo, also known as the Courtyard of the Columns) of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Via Larga, Florence.

Although the gem in Naples is often referred to, details are seldom provided. There may be more than one in the museum with this motif. The only specific reference I have found so far is in an old catalogue of the museum, which lists a carnelian among "Pompeian cameos":

"114564. Cornelian. Diomede seated on an altar."

Domeniconi Monaco, A complete handbook to the National Museum in Naples, page 108. English editor Eustace Neville Rolfe. 10th edition. Naples, 1905. At the Internet Archive. |

|

A cult image of Athena as Palladion,

with raised spear and shield, on the

reverse side of a gold stater.

Circa 336-320 BC. Thought to have been

minted in or near Pergamon, perhaps for

Alexander the Great. The obverse side

shows the head of Herakles wearing

the skin of a lion's head.

Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection),

State Museums Berlin (SMB).

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

These staters are very rare, and while there

is no direct evidence of their origin, some

numismatologists believe they were minted

in or around Pergamon (Mysia), perhaps as

early as 334-332 BC, while Alexander the

Great was still campaigning against the

Persians in Anatolia (Asia Minor), before

his victories gave him control over the area

and allowed him to mint his own imperial

coinage there. This may explain the head of

Herakles on the obverse side, as on other

coins issued by Alexander. On later coins

of his successors, the Hellenistic rulers in

Greece and Asia, Alexander was depicted

as Herakles (see Alexander the Great). |

|

| |

Marble statue of Odysseus.

Parian marble. Late Hellenistic period, before 50 BC. From the

Antikythera shipwreck (see Medusa part 1). Height 203 cm.

Bearded Odysseus strides to the left, but turns his head to the

right. He wears a pilos (πῖλος) conical cap (see Medusa part 6),

an exomis (ἐξωμίς), a type of chiton (χιτών, tunic) fastened only

at one shoulder, leaving the other arm free. A himation (cloak) is

tied around his waist. The statue may be from a group depicting

the theft of the Palladion (see above) during the siege of Troy.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 5745. |

|

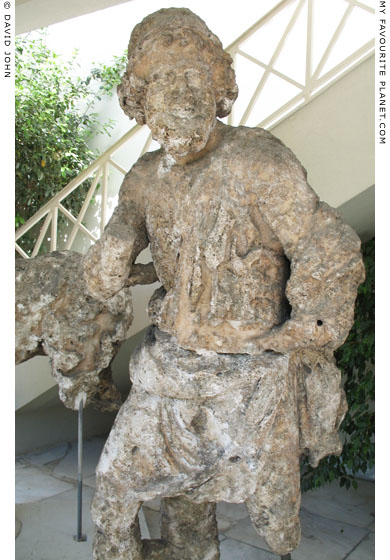

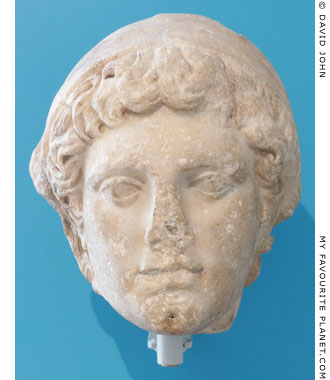

Marble statue of a male, possibly Achilles.

Parian marble. Late Hellenistic period, before 50 BC.

From the Antikythera shipwreck (see Medusa part 1).

Thought to belong to the same sculpture group as

the statue of Odysseus, left. Height 147 cm.

"The young beardless male is depicted moving forcefully

to the right. He is ready to draw the sword from its

sheath with the right hand. The strikingly youthful

appearance of the heroic figure with his unruly, bushy

hair favors his identification as Achilles."

From the museum labelling of an exhibition

about the Antikythera shipwreck, 2013.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 5746. |

|

| |

A marble relief depicting the theft of the bow and quiver of the Homeric hero

Philoctetes (Φιλοκτήτης, Philoktetes) on the island of Lemnos. In the foreground,

Philoctetes, here shown as an old man, lies in a cave, suffering from a snake bite

on his left foot (now missing). Above him two heads appear. To the left the bearded

man wearing a pilos (πῖλος) conical cap is probably Odysseus, while the man with

the curly hair and beard to the right is probably Diomedes. His right hand can be

seen at the top edge of the relief, lifting the strap from which the arrow case hangs.

From Merenda (Μερέντα) in east Attica, in the ancient deme of

Myrrinous (Μυρρινοῦς). Before the middle of the 2nd century AD.

Brauron Archaeological Museum, East Attica. Inv. No. AE 1363. |

| |

As with many Greek myths, the tales concerning the Greek hero Philoctetes related by various ancient authors differ in several ways. He is generally said to have been the son of Poias (Ποίας), king of Meliboea (Μελίβοια) and other cities in Thessaly, who was one of the Argonauts and their best archer. Poias was also said to be a companion of Herakles. As Herakles was dying he asked for somebody to light his funeral pyre for him. Only Poias was willing, and in return the dying hero gave him his bow and quiver, a powerful armament that could not miss its target. According to other versions of the tales, it was Philoctetes not Poias who was an Argonaut and received the Herakles' bow and quiver. Either way, at some point Philoctetes became the owner of the bow by the time of the Trojan War, a generation after Jason and the Argonauts and the adventures of Herakles.

There is only one brief mention of Philoctetes in The Iliad and two even shorter mentions in The Odyssey, but even these are written in a manner that indicates that he was well-known to Homer's Greek audience from other tales, perhaps the now lost poems of the Epic Cycle, particularly The Little Iliad and The Cypria.

Book 2 of The Iliad contains the "catalogue of ships", a long list of the Greek cities and kingdoms which contributed warriors to Agamemnon's military expedition against Troy, including how many ships each sent and who led them. Here we learn that Philoctetes commanded the contigent from Methone, Thaumacia, Meliboia and Olizon in Thessaly, which contributed seven ships collectively, each crewed by fifty men (a total of three hundred and fifty soldiers). But immediately after Homer adds that Philoctetes had not reached Troy but was seriously ill on the island of Lemnos (Λήμνος; Ancient Greek, Λῆμνος) after being bitten by a water snake on the way. His place had been taken by Medon (Μέδων).

"And those that held Methone and Thaumacia, with Meliboia and rugged Olizon, these were led by the skillful archer Philoctetes, and they had seven ships, each with fifty oarsmen all of them good archers; but Philoctetes was lying in great pain in the island of Lemnos, where the sons of the Achaeans left him, for he had been bitten by a poisonous water snake. There he lay sick and in grief, and full soon did the Argives come to miss him. But his people, though they felt his loss were not leaderless, for Medon, the bastard son of Oileus by Rhene, set them in array."

Homer, Iliad, Book 2, lines 716-725. At Perseus Digital Library.

From other literary sources, including the tragic play Philoctetes by Sophocles, first produced in Athens in 409 BC, we learn that the snake bit him on the foot, usually shown in ancient Greek artworks as the left foot. The wound festered and the stench became unbearable for his fellow Greeks, so Odysseus advised Agamemnon to leave him behind on Lemnos. Thus an invalid and suffering great pain, Philoctetes was left alone, abandoned to his fate, to fend for himself for the first nine years of the Trojan war.

In a summary of The Little Iliad, in the tenth and final year of the war the Greek hero Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) captures the Trojan prince and prophet Helenos (Ἕλενος), son of Priam and Hecuba, and twin brother of the prophetess Cassandra. Helenos reveals that Troy can not be captured until Philoctetes is brought there from Lemnos and the invincible bow and arrows of Herakles are used.

"After this Odysseus goes on an ambush and captures Helenos, and as a result of Helenos' prophecy about the city's conquest Diomedes fetches Philoktetes from Lemnos. Philoktetes is healed by Makhaon; he fights in single combat with Alexandros [Paris] and kills him."

Proclus' Summary of the Little Iliad, attributed to Lesches of Mytilene. In Proclus, The Epic Cycle, edited by Gregory Nagy. At web.archive.org (archived from stoa.org).

According to some accounts, Odysseus accompanied Diomedes (Διομήδης)) to Lemnos, where the latter either stole Herakles' bow from Philoctetes or took it by trickery, but then persuaded him to sail to Troy with them. In Sophocles' tragedy Diomedes plays no part, and it was Odysseus and Neoptolemos, the son of Achilles (by this time dead), who took the bow. Philoctetes is only persuaded to fight at Troy by the deified Herakles, who makes a personal appearance, as an epiphany (a physical manifestation of a god) or deus ex machina solution to the plot. Pausanias reported seeing a painting of "Odysseus in Lemnos taking away the bow of Philoctetes" in the "Pinakotheke" of the Propylaia on the Athenian Acropolis (see above).

In the Epitome by Apollodorus (1st or 2nd century AD), it was the Argive Greek soothsayer Calchas (Κάλχας, Kalkhas) rather than Helenos who warned the Greeks that they needed Philoctetes and his bow in order to win the war.

"When the war had already lasted ten years, and the Greeks were despondent, Calchas prophesied to them that Troy could not be taken unless they had the bow and arrows of Hercules fighting on their side. On hearing that, Ulysses went with Diomedes to Philoctetes in Lemnos, and having by craft got possession of the bow and arrows he persuaded him to sail to Troy. So he went, and after being cured by Podalirius, he shot Alexander [Paris]."

Apollodorus, Epitome, chapter 4, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

On his arrival at the Greek camp on the seashore before Troy, Philoctetes' terrible wound was cured either by Podaleirios (Ποδαλείριος) or Machaon (Μαχάων), doctors from Thessaly described by Homer as "sons of Asklepios" (Iliad, Book 2, lines 729-733; see Asklepios). In other versions he was cured by both physicians, or even Asklepios himself. He was one of the Greek warriors who hid in the Trojan horse, and during the sack of Troy killed many Trojans, including Paris who he shot with arrows. In The Odyssey, Odysseus while boasting what an excellent shot he was with a bow, still admits that Philoctetes was a better archer during the Trojan War.

"Well do I know how to handle the polished bow, and ever would I be the first to shoot and smite my man in the throng of the foe, even though many comrades stood by me and were shooting at the men. Only Philoctetes excelled me with the bow in the land of the Trojans, when we Achaeans shot."

Homer, Odyssey, Book 8, lines 215-220. At Perseus Digital Library.

Homer informs us that Philoctetes survived the war.

"Safely, they say, came the Myrmidons that rage with the spear, whom the famous son of great-hearted Achilles led; and safely Philoctetes, the glorious son of Poias."

Homer, Odyssey, Book 3, lines 188-190. At Perseus Digital Library.

Later authors wrote that he ended up in southern Italy, where, according to legend, he founded a number of cities. Eventually he was killed when he took sides with some colonists from Rhodes in a conflict with colonists from Pallene. The inhabitants of Macalla built his tomb as a sanctuary where he was honoured as a divine hero. The bow and arrows of Herakles were placed in the temple of Apollo in Macalla, but were later taken to the temple of Apollo at Crotone, although according to another account the arrows were in the Apollo temple at Thurii, which was also founded by Philoctetes. (The historian Herodotus and the epic poet Panyassis of Halicarnassus are said to have emigrated to Thurii in the 5th century BC.) |

|

The bow and arrow case of Philoctetes on the relief in Brauron. |

|

| |

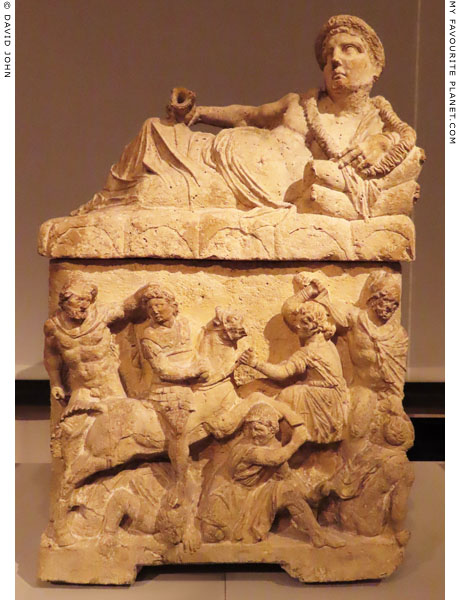

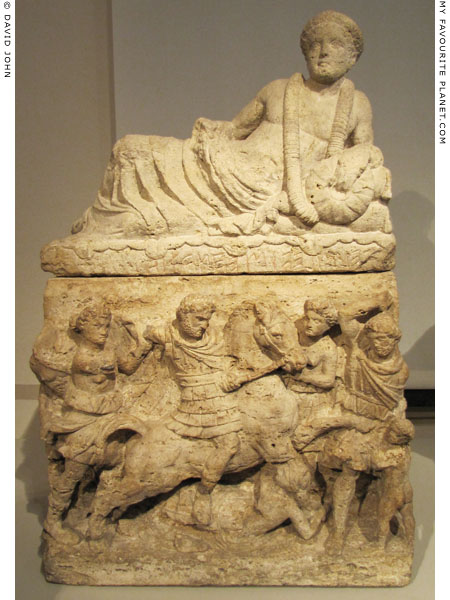

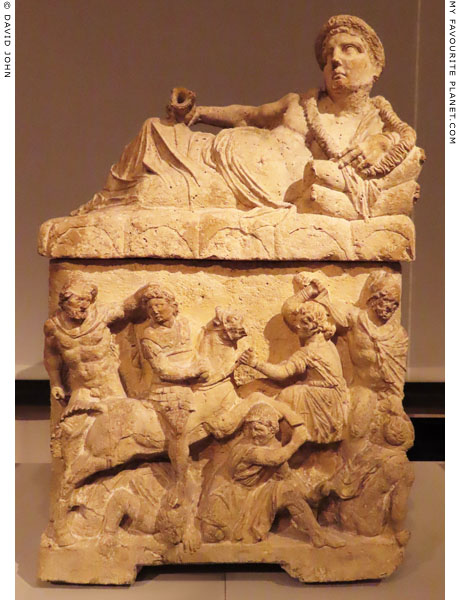

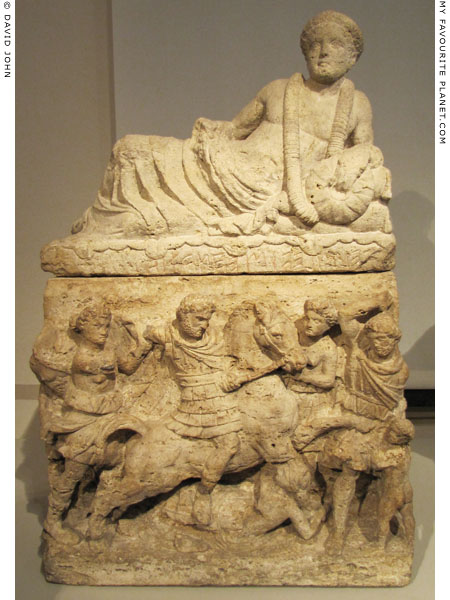

An Etruscan cinerary urn with a high relief depicting the ambush

and murder of the Trojan prince Troilus (Τρωΐλος, Troilos) by

Achilles and Ajax, son of King Telamon of Salamis (Αἴας, Aias;

also referred to by Homer as Τελαμώνιος Αἴας, Telamonian Aias).

The death of Troilus had been prophesied by an oracle, and

symbolizes the inevitability of destiny.

One of the figures attacking Troilus, to the right of his horse,

appears to be a female, and has been referred to as a "Fury".

She holds onto the horse's reins with her left hand while

about to strike with the sword in her raised right hand. [4]

On the lid the sculpted figure of the deceased reclines on a couch,

wearing a wreath on his head, a garland around his neck, and a

mantle covering his lower torso and legs. He rests his left elbow

on cushions, and in his right hand he holds a kantharos (cup).

Travertine, around 150 BC. Found in 1822 in the necropolis of

Strozzacapponi, around 10 km southwest of Perugia, Italy.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. Nos. SK 1289 and Sk 1290.

|

One of several ancient artworks acquired for the Berlin museum in Rome in 1826-1827 from the collection of Jakob Salomon Bartholdy (1779-1825), the Prussian consul-general in Rome (see another Etruscan cinerary urn below).

The story of the murder of Troilus is not related in The Iliad, although King Priam of Troy (Πρίαμος, Priamos) mentions him as one of the three of his sons killed in war when chastising the remaining nine:

"Then he [Priam] called to his sons, upbraiding Helenos, Paris, noble Agathon, Pammon, Antiphonos, Polites of the loud battle cry, Deiphobos, Hippothoos, and Dios. These nine did the old man call near him.

'Come to me at once,' he cried, 'worthless sons who do me shame. Would that you had all been killed at the ships rather than Hektor. Miserable man that I am, I have had the bravest sons in all Troy - noble Nestor, Troilus the dauntless charioteer, and Hektor who was a god among men, so that one would have thought he was son to an immortal - yet there is not one of them left. Ares has slain them and those of whom I am ashamed are alone left me.'"

Homer, The Iliad, Book 24, lines 249-260. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pseudo-Apollodorus wrote that Troilus was the son of Apollo by Priam's wife Queen Hecuba (The Library, Book 3, chapter 12, section 5). It is thought that the episode of his murder by Achilles was included in other works of the Epic Cycle, and it was also mentioned by later writers, including a lost play by Sophocles, and commentators. There are variations to the story, according to which Troilus was either ambushed while riding, or killed at the altar of the temple of Thymbraean Apollo. He is variously depicted as a boy or a young man.

The subject was depicted on number of Etruscan cinerary urns (see below) as well as Etruscan wall paintings. It also appears on Greek sculptures and vases, notably on the body of the "François Vase", the oldest black-figure Attic krater, circa 570-565 BC, signed by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias. National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Inv. No. 4209; Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 300000.

An Attic black-figure neck amphora, painted around 580 BC by the Painter of London B 76 (see above), depicts Achilles, fully armed, waiting in ambush behind a gushing fountain, in front of which Troilus' sister Polyxene stands with a pitcher, while Troilus sits on one of two horses. British Museum, Inv. No. 97.7-21.2. According to one version of the myth, Polyxene was captured by Achilles and Ajax during this ambush (see below). This would eventually lead to the deaths of all three.

See also other Etruscan cinerary urns with depictions of Homeric scenes below:

the Recognition of Paris

Odysseus and Polyphemos (Homer part 3)

Odysseus and Penelope's suitors (Homer part 3) |

|

| |

A high relief depicting the ambush of Troilus by Achilles and Ajax

on the front of an Etruscan alabaster cinerary urn.

2nd century BC. From the Etruscan city Volterra (Pisa), central Etruria, Italy.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Inv. No. H III QQQ 3.

|

Two warriors, wearing crested helmets and armed with swords and round shields, attack a naked young man on horseback. Another male figure lies beneath the horse. On the far right is part of an archway in a wall topped by two blocks, perhaps of a battlement, indicating that the action takes place outside the walls of Troy, or at a fountain house. The Dutch archaeologist L. J. F. Janssen (1806-1869; curator of the Leiden museum, 1835-1868) suggested that the scene may depict a heroic deed outside the gates of Thebes.

This is one of nine well-preserved Etruscan alabaster cinerary urns which provide the focal point for the Leiden museum's small Etruscan section. Several other urns in the collection are not usually on display because of lack of space. They were purchased in Italy between 1826 and 1850 by the Dutch archaeologist Colonel Jean Emile Humbert (1771-1839) on behalf of the museum.

The urns contained the ashes or bones of wealthy Etruscans, and are smaller equivalents of the monumental Greek and Roman sarcophagi. As is usual on this type, the lid is in the form of a statue of the diseased person, depicted as reclining on a couch, enjoying their eternal banquet. The faces and heads of the figures are sculpted in greater detail than the rest of the body and often disproportionately larger.

Many of the reliefs on the front of the urns in the Leiden collection depict scenes from Greek mythology, including several with Homeric themes (see Odysseus and Polyphemos and Odysseus and Penelope's suitors below). Those on display are well sculpted, although without the polished finesse of the best Greek and Roman reliefs, with the figures filling as much of the limited space as possible. The compact scenes present the essence of stories using an effective and accomplished form of visual shorthand. The reliefs are usually framed above and below by representations of architectural decorative elements, such as egg-and-dart motifs, dentils, beading, or triglyphs and metopes.

See: Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen, De etrurische grafreliëfs uit het Museum van Oudheden te Leyden, No. 24, pages 16-17 and plate XI, 24a and 24b. H. J. Brill, Leiden, 1854. At the Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

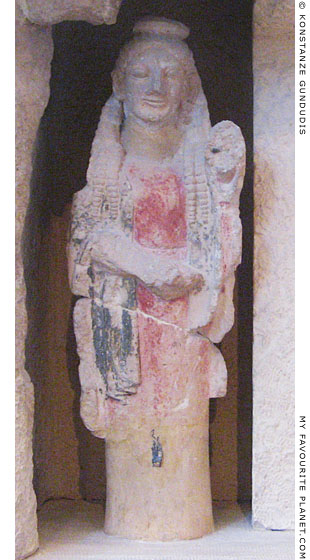

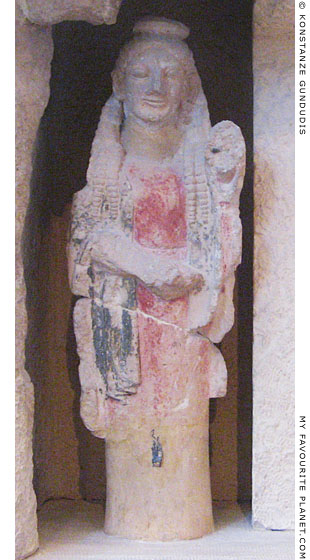

The so-called "Olive Tree Pediment", "Troilus Pediment" or "Fountain House pediment",

a small sculpture group of painted poros limestone from the Athens Acropolis.

Around 575-500 BC. Found in 1888 to the east of the Parthenon. Height 80 cm, width 148 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Acr. 52.

|

The small sculpture group, appearing to the modern eye rather like an ancient doll's house or a diorama, has been restored from several fragments. It is thought to be part of the pediment of an unknown Archaic building on the Athens Acropolis, perhaps the theoretical building known as "Temple A", which may have stood in the area now occupied by the Erechtheion. Another sculpture group of similar size and date, depicting the Apotheosis of Herkales (Acropolis Museum, Inv. No. Acr. 9), may have decorated the pediment at the other end of the same building.

The pediment sculptures consist of figures in front of a projecting building or porch covered by a tiled hip roof (i.e with a sloping side where a pediment would be), which is supported at the front by a long wall to the left of the doorway. Above part of a wall (described as a precinct wall) to the left of the porch are fragments of an incised olive tree, hence the name "Olive Tree Pediment".

Only one female figure and fragments of two other females and a male have survived, but the scene probably included a number of others. The torso of one female is affixed to the wall left of the doorway, and the legs of another, wearing an ankle-length gown with geometric decoration, stand to the right of the porch. Only the relief of part of the male's bare leg can be seen at the left of the fragment of wall left of the porch.

The most complete figure is the free-standing sculpture of a woman, who in the reconstruction stands in the doorway, facing outwards. On her head is a disc which has been interpreted as a cushion, and her left arm appears to be raised. This has led to theories that she was either a hydriaphoros (water jug carrier), with her left hand steadying a jug she carried on her cushioned head, or an early Caryatid supporting the roof.

The hydriaphoros theory led to the building being interpreted as a fountain house, which then led to the scene being seen as depicting Troilus being ambushed by Achilles as he watered his horses. The male figure was thus thought to be Troilus. It has been argued that this story has no apparent relevance to the Acropolis or the mythological history of Athens, which provided the subjects for much of the building decoration on the Acropolis in the Archaic and Classical periods. However, the story of Herakles being introduced to the Olympian gods (the Apotheosis of Herkales) and other subjects, such as the birth of Pandora on the base of Pheidias' statue of Athena Parthenos, were likewise not directly connected with the Acropolis.

A number of other interpretations have been suggested, including theories that the scene depicts mythological figures connected with the history of Athens, such as Pandrosos, one of the daughters of King Kekrops, or even Erechtheus. According to another theory, it may represent the Panathenaic procession approaching the sanctuary of Athena Polias. The olive tree may represent the olive planted by Athena during her contest with Poseidon for the patronage of Athens. |

|

The most complete surviving figure

of the pediment, depicting a female,

who in the reconstruction stands

in the doorway of the building.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

|

| |

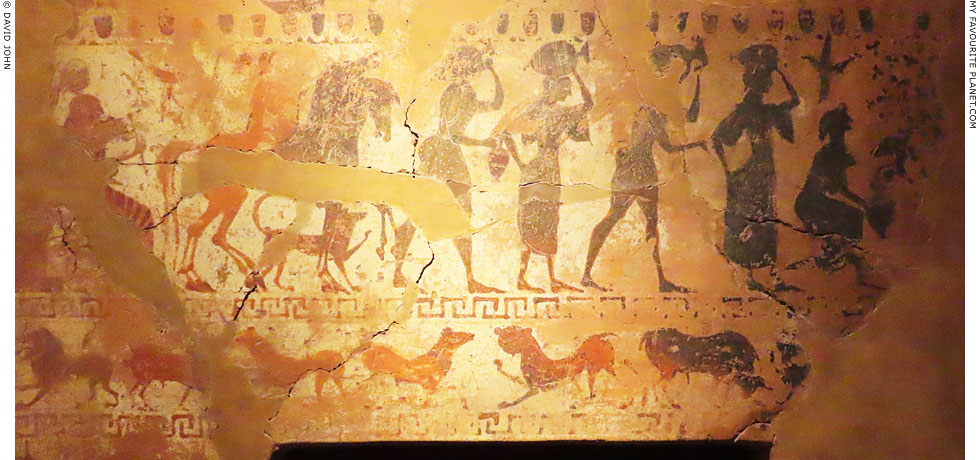

Detail of the headpiece of a Klazomenian sarcopahagus with a black-figure

painting believed to depict a scene from the myth of Troilus.

A chance find in an ancient cemetery of ancient Abdera, Thrace, northeastern Greece.

480-470 BC. Attributed to the Albertinum Group (active around 510-470 BC),

or perhaps a local workshop. Length 219 cm; width 121.5 cm at the top and 74 cm

at the bottom; height 58 cm at the top and 47.7 cm at the bottom.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MA 6922.

(Formerly in Komotini Archaeological Museum.)

|

Like ancient Greek vases, the visually most important area of many Klazomenian sarcophagi is the painted figurative scene on the "headpiece" (see caption, right). Often these were depictions of mythological characters, creatures or events. While many surviving paintings conform to iconographical types known from vases and other artworks of the period, some scenes are not so easily recognizable, and even seem to lack narrative content.

This sarcopahagus is badly damaged and worn, and the subject of the painting is not at all clear, but has been interpreted as a scene from the story of the ambush of Troilus by Achilles and Ajax.

On the right a row of two men and two women stand or walk to the right carrying hydrias on their heads. The man at the back of the line also holds a smaller jug in his left hand. At the front of the line (far right), another woman kneels, apparently filling her hydria from a fountain. This may be one of the earliest depictions of a queue in Greek art. If a fountain was ever shown here, perhaps with Achilles lurking behind it, it is no longer visible. The left and right extremities of the picture have been destroyed by time. But we do appear to have the suggestion of a fountain, and this leads us in the direction of the Troilus myth.

On the left side of the scene stand three or four horses, apparently a chariot team. Below their legs is a hunting dog. On the far left what looks like the head of a seated man, his arm possibly holding a sceptre, and his bent legs, covered by a horizontally striped garment. Behind him stands another (younger?) man. This may be Priam on his throne (presumably at home in Ilion), while Troilus arrives at the fountain on his chariot.

The placing of an enthroned Priam here may be an example of what scholars have considered a typical disregard for time and space by ancient Greek artists. Or perhaps something else is going on in the picture? One may speculate on alternative interpretations, but unless a comparable - and more complete - artwork is discovered, judgement remains elusive.

Now a faint display of faded silhouettes, judging from paintings on other Klazomenian sarcopahagi, this was once a fresh, vivid and lively composition, which revealed as much about daily life as about myth and warfare. Although perhaps not the finest example of late Archaic Greek painting, it remains an intriguing glimpse into another world. Interestingly, although this artist and others who painted this type of sarcophagus uesed the older black-figure painting technique, rather than the more modern red-figure, the effect of the style is not quite as archaic. For example, white paint is used to show contours and details (e.g. eyes, clothing) rather than the conventional black-figure method of incising or scratching away the paint.

Above this scene, separated by a band of egg-and-dart pattern, are the sparce fragments of another, believed to have depicted a fight between pygmies and cranes (not shown in the photo above). Below the Troilus scene is a frieze of standing animals (a lion, a panther, bulls, horses), with a meander pattern above it and another below.

The rest of the painting on the sarcophagus is now even more difficult to see, with parts of the long chain pattern down the right sidepiece, here and there traces of meanders, helixes, a lotus flower, palmettes, stars and egg-and-dart patterns. Remnants of other small figurative scenes are all but indiscernible, but are said to depict a male figure wresting a mythical monster and another male figure driving a chariot.

The paintings on the other, smaller Klazomenian sarcophagui from Abdera are in an even worse condition, with only the scene on the footpiece still visible. This shows a black dog attacking a much larger white rabbit on the left, while two other black dogs run to the right. There seems to have been another animal beneath the right-most dog, but this is no longer decipherable. Late 6th century BC. Inv. No. MA 4500.

The presence of Klazomenian sarcophagi at Abdera may be connected to the fact that the city was initially founded in the mid 7th century BC by colonists from the ancient Ionian city of Klazomenai (Κλαζομεναί, today Urla, Turkey), 32 km southwest of Smyrna (Σμύρνα; today Izmir, Turkey). Although the first settlement is said to been unsuccessful, it was refounded around a century later by refugees from Teos (Τέως, today Sığacık, Turkey), an Ionian neighbour of Klazomenai, and the Abderitans maintained links to their Ionian motherland.