|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Aristion of Paros |

|

back |

Aristion of Paros |

|

|

| |

Aristion of Paros

Aristion of Paros (Αριστίων Πάριός) was a Greek sculptor, working in Attica around 540-525 BC. He is not mentioned by ancient authors, and his name is known only from four inscribed signatures on surviving parts of funerary monuments, all found in or near Athens. On the first two, the signature of Aristion is certain, the third signature is probable and the fourth is speculative. The only sculpture that can be attributed to him with any certainty is the "Phrasikleia kore" (see below).

He is the only Archaic Parian sculptor whose name is known, although it is not absolutely certain that he was from the Cycladic island of Paros (Πάρος), since the name as Αριστίων Πάριός (Aristion of Paros) is not complete on any of the surviving inscriptions. Nevertheless, debate continues over whether he trained on Paros or in Athens, and to what extent his work may have represented the contemporary styles and techniques of either place. [1]

It has been suggested that "the stele of Aristion", signed by the sculptor Aristokles around 520-510 BC, may be the funerary monument for Aristion of Paros (see Aristokles). It has even been mooted that Aristokles may have been Aristion's successor, and that the two artists were relatives.

Another, more controversial suggestion is that Aristion may have been responsible for the relief sculptures on the north and east friezes of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi [2], built around 530-525 BC ( see below). The sculptor of the reliefs is known as "Master B", and other candidates have been suggested, including Boupalos of Chios and Endoios. |

| |

|

Three fragments of an inscribed base of a funerary monument for Antilochos with the signature of Aristion, dated around 530 BC, were found separately in Athens, near the Temple of Hephaistos (formerly known as the Thesion) in 1839, and the near the "Stoa of the Giants" in the Agora in 1858. The monument probably stood in the Kerameikos cemetery. The circular cutting on top of the base, 50 cm in diameter, suggests that it supported a column which may have been surmounted by a kouros, a sphinx or even a lion.

[Ἀ]ντιλόχο : ποτὶ σε͂μ’ ἀγαθο͂

καὶ σόφρονος ἀνδρὸς /

[δάκρυ κ]ά̣ταρ[χ]σ̣ον̣, [ἐ]π[ε]ὶ κα̣ὶ

σὲ μένει θάνατος.

Written retrograde (reversed) on the right side of the base:

Ἀριστίον

μ’ ἐπόεσεν.

Stranger, shed a tear at the tomb of Antilochus, who was a good and modest [or moderate] man, for death awaits you too.

Aristion made me.

Inscription IG I³ 1208 (also IG I² 972; IGAA 120,8; CIA 1. 466). Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. Nos. of the fragments 10647, 10648 and 10649. |

| |

| |

2. The Phrasikleia kore |

|

|

During his visit to Greece in 1729-1730, the French priest and antiquarian Abbé Michel Fourmont (1690-1746) recorded an inscription on the side of a limestone block in the Panagia church at Merenda (Μερέντα) in east Attica, which was in the ancient deme of Myrrinous (Μυρρινοῦς). The block was a statue base reused as the capital of an engaged column in the 13th century Byzantine church (see drawing below). It is the earliest known Attic inscription written in stoichedon (στοιχηδόν, literally set in a row; with letters aligned vertically and horizontally).

When Greek and German archaeologists visited the church over a century later they found that the individual letters of the inscription had been deliberately destroyed by careful chiselling, perhaps by Fourmont himself. [3] The German archaeologist Habbo Gerhard Lolling (1848-1894) removed the base from the column in 1876, and was able to read the signature of Aristion on its previously hidden left side [4]. It was taken to the Athens Epigraphical Museum in 1968.

σε͂μα Φρασικλείας·

κόρε κεκλέσομαι

αἰεί, / ἀντὶ γάμο

παρὰ θεο͂ν τοῦτο

λαχο͂σ’ ὄνομα.

On left lateral side of base:

Ἀριστίον : Πάρι[ός μ’ ἐπ]ο[ίε]σ̣ε.

The grave marker (sema) of Phraskileia. I shall always be called kore (maiden), having received this name from the god instead of marriage.

Aristion of Paros made me.

Inscription IG I³ 1261 (also IG I² 1014; IGAA 138,46).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 13383.

Height 30 cm, width 53 cm, depth 57 cm.

The scribe who cut the inscription is thought to have been the same person who inscribed bases for the sculptors Phaidimos and Aristokles (see the note on the Aristokles page).

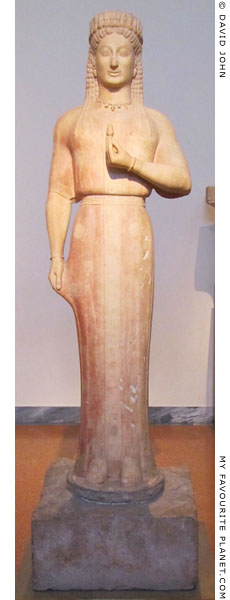

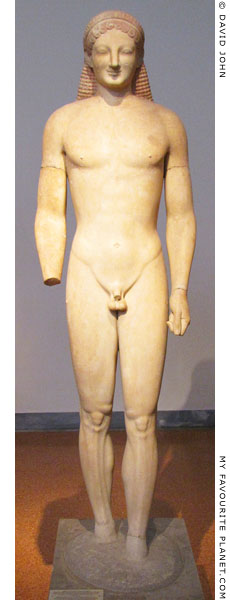

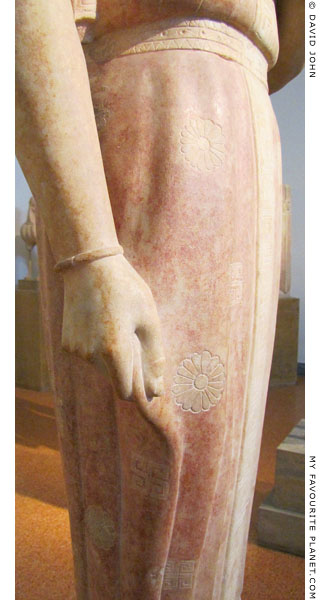

In May 1972, during excavations in the necropolis at Merenda by the Greek archaeologist Efthymios Mastrokostas (Ευθύμιος Μαστροκώστας, 1915-1998), two archaic statues were discovered. The female kore and male kouros (see photos, above right) had been carefully buried together in Antiquity (perhaps around 480-460 BC), in a pit around 200 metres north of the Panagia church. Mastrokostas was able to match the round plinth of the kore and a large lead ring found with it with the inscribed base signed by Aristion, and she was thus identified as Phrasikleia (Φρασικλεία). The male figure, known as the Merenda Kouros (or Kouros of Merenda) and thought to have been made about ten years later, was dubbed "the Brother".

The statues are now exhibited together in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. Nos. 4889 and 4890. They are in excellent condition, although the arms are broken, and the right hand, the feet and plinth of the kouros are missing. Substantial traces of red paint are preserved on both. |

|

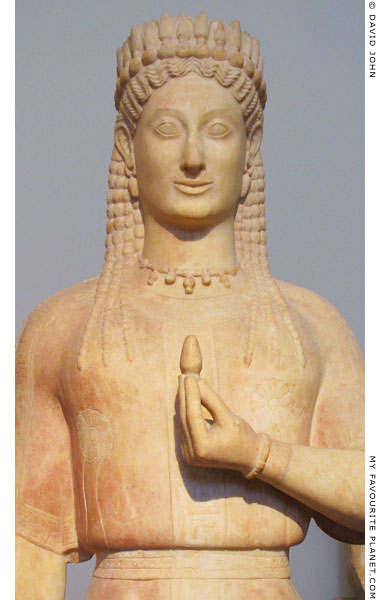

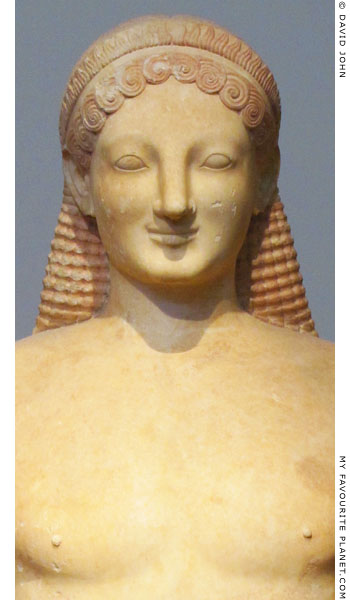

The Phrasikleia kore

statue by Aristion of Paros.

Circa 550-540 BC. Parian marble.

Height 179 cm. Height including

the plinth and base 211.5 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4889. |

| |

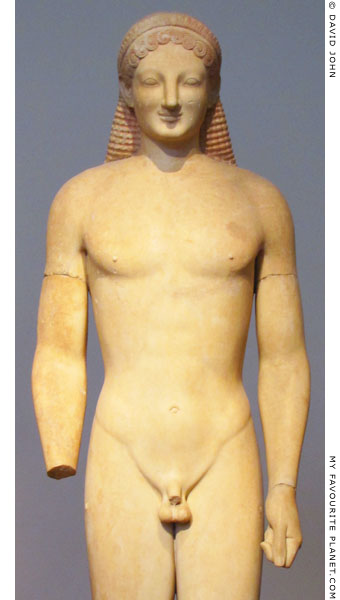

The Merenda Kouros, found

with the Phrasikleia kore.

Around 540-530 BC. Parian

marble. Height 189 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4890. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

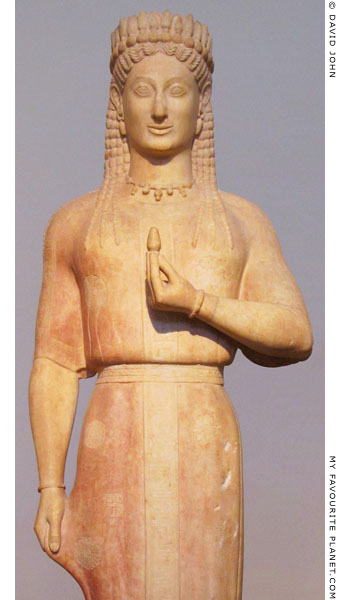

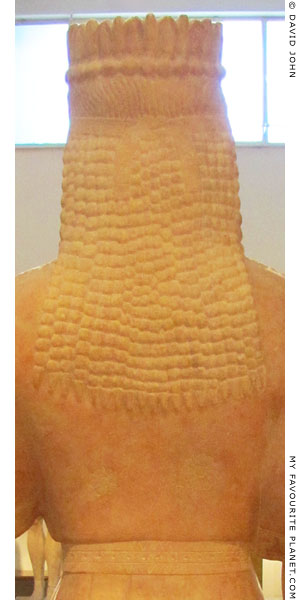

Details of the Phrasikleia kore.

"The elaboration of jewellery and painted dress pattern is the more effective for the foldless

simplicity of the dress and the adolescent body of the girl whom, as her epitaph tells, death

took before a husband. To modern eyes she is perhaps the most beautiful of the korai."

John Boardman, Greek sculpture, the Archaic period: A handbook,

pages 75-76. Oxford University Press, 1978. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Details of the Phrasikleia kore. |

|

| |

|

|

| Details of the Merenda Kouros. |

|

| |

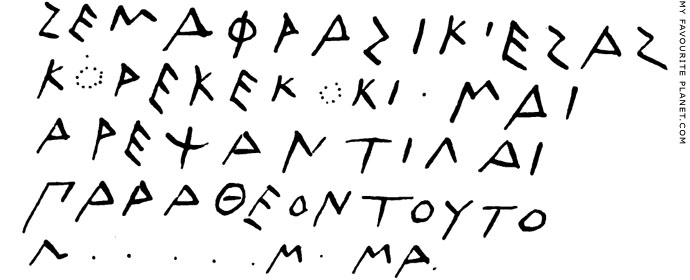

A drawing of the inscription on the base of the "Phrasikleia kore" by Aristion of Paros,

from the Panagia church at Merenda, Attica, after the copy made by the French priest

and antiquarian Abbé Michel Fourmont during his visit to Greece in 1729-1730.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 13383. Inscription IG I(3) 1261.

Source: August Boeckh, Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, Volume I,

No. 28 (CIG I 28), pages 46-47. Officina Academica, Berlin, 1828. At Googlebooks. |

| |

A drawing of the inscription on the "Phrasikleia kore" base, with the

uncertain lettering restored by Habbo Gerhard Lolling [see note 4].

Source: Ernest Stewart Roberts, An introduction to Greek epigraphy, Part 1,

No. 43, page 79. Cambridge University Press, 1887. At the Internet Archve.

(The dimensions of the stone are given as 25.5 cm x 56.5 cm.) |

| |

| |

3. The Xenophantos base |

|

|

An inscribed marble base of a life-size (or slightly larger) kouros statue

by Aristion of Paros, as a funerary monument for Xenophantos

(Χσενοφάντος), dedicated by his father Kleoboulos (Κλεόβουλος).

Around 540-525 BC. Found in 1873 near the Dipylon in the

Kerameikos, Athens. Height 28 cm, width 24 cm, length 44 cm. [5]

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 10642.

|

Only the last part of the sculptor's inscribed signature has survived, ... αριος (... arios), thought to be the end of Πάριος (Parios, of Paros), and it is generally accepted to be that of Aristion of Paros.

σε͂μα πατὲρ Κλέ[.]-

βολος ἀποφθιμέ-

νοι Χσενοφάντοι

θε͂κε τόδ’ ἀντ’ ἀρετε͂ς

ἐδὲ σαοφροσύνες

Written on the left side of the base:

[Ἀριστίον ἐποίε Π]άριος

This grave marker (sema) the father Kleoboulos

erected for (his son) Xenophantos, who died,

in remembrance of his virtue and moderation.

Aristion the Parian made it.

Inscription IG I³ 1211 (also IG I² 986; IGAA 120,9; CIA Suppl. 477 b). |

|

|

| |

| |

4. The Kantza base |

|

|

A drawing from a squeeze of the inscription on the "Kantza base", a fragment of an

inscribed Doric column, found at Kantza, east Attica, and now in the British Museum.

Source: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors),

No. 18, pages 17-18. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

|

Evidence for the fourth signature is more obscure and appears a little thin, particularly since little discussion concerning it has been published. A fragment of an inscribed Doric column, probably from a funerary monument, was found near the Agios Nikolaos church at the village of Kantza (Κάντζα, today Leontario Pallini, Λεοντάριο Παλλήνης), east Attica. It is now in the British Museum. Inv. No. 1823.4-5. Inscription IG I² 988.

Another fragmentary inscription found in the area of Kalyvia Kouvara, in the ancient Deme of Prospalta (Πρόσπαλτα), around 15 kilometres from Kantza, was thought to have been inscribed by the same stonemason, and became associated with the Kanza fragment and attributed to Aristion following a study by Anton Raubitschek in 1939 [6]. The conjecture that both fragments were from the same funerary monument made by Aristion led to the restoration of the inscription as:

[Ἀριστίον(?) Πάριό(?)]ς μ’ ἐποίεσε̣[ν].

[– – τόδ]ε σεμ’ ἀγαθο͂ [καὶ σόφρο]νος ἀνδρὸς.

Aristion the Parian made me.

This is the marker (sema) of ..., a good and moderate man.

Inscription IG I³ 1269 (also IG I² 988+; IGAA 140,49)

As restored, the last phrase would be the same as on the Antilochos base (see above).

Considering the revival of interest in Aristion, it is surprising that there appears to have been no recent reexamination of these fragments. |

|

|

| |

| |

The Siphnian Treasury in Delphi |

|

|

Part of the Gigantomachy, the battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants,

the children of Gaia, on the north frieze of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi, built

for the people of Siphnos around 530-525 BC (before 524 BC). Parian marble.

On this part of Slab Β of the frieze, the twin gods Apollo and Artemis (left) fight a row

of three Giants wearing Corinthian helmets and holding round shields in front of them.

The figures were named by painted inscriptions, and traces of some have survived.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

|

The Siphnian Treasury stood at the southern edge of the Sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi, on the left (south) side of the Sacred Way up to the god's oracular temple. According to Herodotus (Histories, Book 3, chapter 57) and Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 11, section 2) the people of the Cycladic island of Siphnos (Σίφνος; modern spelling Sifnos) paid for the building with a tithe (tenth) of the income from their gold and silver mines, in compliance with a command of Apollo through an oracle. Herodotus wrote that it was as rich as any of the treasuries at Delphi.

The building of the treasury is thought to have been completed before the invasion of Siphnos by Samian exiles mentioned by Herodotus, which has been dated to 525 BC based on other contemporary events and records. It is believed that after the invasion Siphnos did not regain its previous prosperity, and the mines appear to have fallen in to disuse. Pausanias wrote that the mines were flooded by the sea when the Siphnians neglected to pay the tithe to Apollo due to greed, implying divine punishment.

Constructed of Parian and Naxian marble [7] and richly decorated with sculpture, it was one of the earliest marble buildings in Greece and among the earliest there in the Ionic style. 8.27 metres long and 6.09 metres wide, it was built on an east-west axis, with its entrance at the west, on one of its short sides. At the time it was built the front faced the entrance to the sanctuary (the entrance was moved to the east when the Sacred Way was extended during the 5th century BC). Like the other treasuries, it resembled a small temple, and in form it was distyle in antis, that is with a projecting wall (antis) at each the side of the front porch, between which were two columns. In this case the columns were in the form of Caryatids, each wearing a polos decorated with reliefs depicting mythological scenes (see photo, right).

It had the earliest known continuous narrative frieze around the four sides of its entablature, with a sculpted relief depicting a different mythological theme on each side. The east pediment, at the back of the building, depicted the myth of the struggle between Apollo and Herakles over the Delphic tripod. Several fragments of all these sculptures are now in the Delphi Archaeological Museum, but no remains of a pediment from the west side have been discovered.

The difference in styles of the frieze reliefs has led scholars to believe that they were made by two different sculptors and their workshops. The unknown sculptor of the reliefs on the south and west sides has been named as "Master A", while the artist who made those on the north and east sides is known as "Master B".

The flat, frontal style of Master A's work is earlier, and he is thought to have been the senior artist of the two, awarded the privilege of making the sculpture around the building's entrance. The style also indicates that he may have been from East Greece (Ionia and the eastern Aegean islands), and he may also have made the Caryatids.

Master B's work is bolder, livelier and more innovative, with more suggestion of depth and perspective, and he may well have been a younger artist realizing new approaches to monumental sculpture. Some of these representational innovations had already appeared in Attic vase painting, and it is thought that Master B was an Athenian or at least familiar with Athenian practices. It has even been suggested that he may also have been a painter. He may also have sculpted the east pediment.

Unusually for architectural sculpture, the north frieze is inscribed with the signature of the sculptor (presumably "Master B"), finely chiselled around the rim of the shield of the third Giant, who has been identified as Alektos (Ἀληκτος). By a twist of history, the part of the shield with the artist's name has broken off (see photo, above right). A number of scholars have attempted to identify him on various grounds, and Aristion, Boupalos of Chios (Βούπαλος) and Endoios have been suggested, as well as conjectural sculptors, Daippos (Δάϊππος) and Deiochos (Δηΐοχος).

The inscription was altered in Antiquity, the reason for which is unknown but also much debated. What remains shows that the sculptor claimed to have made the reliefs on this side, the north of the building, and at the back, the east side.

... τά]δε καὶ τὄπισθεν ἐποίε

... made these and those behind.

Inscription FD IV,2 82/83[2] (also CEG 449).

See the reconstruction of the east side and fragments of the east frieze in Homer part 2.

See other sculptures from the Siphnian Treasury on the Demeter, Hermes and Medusa pages. |

The inscription on the shield of the third

Giant (figure No. 18), identified as Alektos.

The top right of the shield, on which the

artist's name was inscribed, has broken off. |

| |

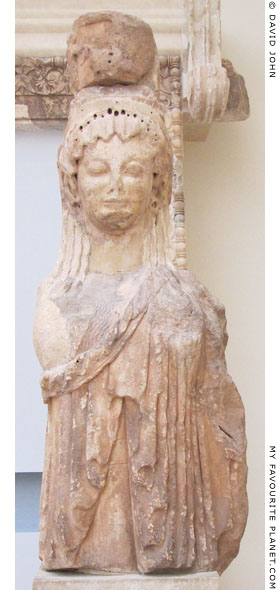

The upper torso of the surviving south

caryatid of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi.

Restored from six fragments, found

1891-1894 in the gardens and houses

of the modern village had been built

over the sanctuary. Parian marble

[see note 7]. Height 175 cm.

The figure wears a polos (or kalathos),

and an oblique himation over a chiton

with thin wavy pleats. A relief carved

all round the side of the polos has a

Dionysian theme with Silens and

Maenads, and Lesbian moulding runs

around the base of the hat. Holes in

the hair beneath the polos were for

the attachment of metal or marble

ornaments. The style of the sculpture

suggests it was made by an artist from

the Aegea islands trained in Ionia.

It is believed that the caryatid was

made by "Master B", and the relief on

the polos (see below) by "Master A".

Delphi Archaeological Museum.

See also:

the "Chiotissa" kore statue

from the Athens Acropolis

the head of a caryatid from Delphi |

| |

Detail of the Dionysian relief and the

Lesbian moulding on the polos of south

caryatid of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

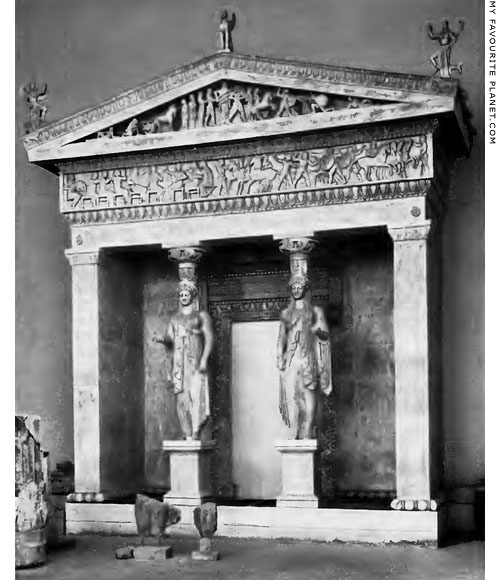

"Antiquated restoration of the Treasury of the Siphnians" in Room 10

of the Delphi Archaeological Museum. A mid 20th century photo of the

treasury entrance as restored according to early theories. Although

impressive, the restoration incorrectly showed the east pediment

and frieze relief as being above the building's entrance, with the

caryatids and doorway which were originally on the west side. Once

one of the museum's star exhibits, it has since been removed.

Source: Pericles Collas, A concise guide of Delphi, illustrated

with photos by Dimitrios Harissiadis. C. Cacoulides, Athens.

Publishing date unknown. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Aristion

of Paros |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Parian sculptors

Later sculptors from Paros included Euphron (working around 470-450 BC) and Skopas (working around 395-350 BC).

Kritonides of Paros, mid 5th century BC, is known from his signature on a fluted marble column, a base for a statue dedicated to Artemis. See:

Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors), No. 6, pages 8-10. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

2. Aristion and the Siphnian Treasury

The suggestion, made by Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, has been refuted on stylistic grounds by Elena Walter-Karydi.

See:

Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, The Archaic style in Greek sculpture, page 270. 2nd edition, Ares, Chicago, 1993.

Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, Prayers in Stone: Greek architectural sculpture circa 600-100 B.C.E., page 392 and note 14 (page 462). The Sather Classical Lectures 1996. University of California Press, 1999. Online edition at the Internet Archive.

Elena Walter-Karydi, Aristion, in: Künstlerlexikon der Antike, page 84. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2007.

3. The destruction of the Phrasikleia inscription

In 1887 the German archaeologist Alexander Milchhoefer (1852-1903) reported that the inscription had been "deliberately destroyed by a former church warden Panussis Dimas Bardsis", but with no further details about this person or the allegation. Other scholars of the time appear to be strangely tacit about the act of vandalism.

"Phrasikleia-Inschrift, vermauert in der Panagia, Merenda. C. I. A. I, 469. Vgl. Loewy N. 12. Von einem früheren Kirchenvorsteher Panussis Dimas Bardsis absichtlich zerstört."

A. Milchhoefer, Antikenbericht aus Attika, No. 160, page 278, in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Volume 12. Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1887. At the Internet Archive.

"Loewy N. 12" refers to the entry on the inscription in:

Emanuel Loewy (1857-1938), Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer, No. 12, page 15. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The inscription may have been defaced by Abbé Michel Fourmont himself, rather than by a zealous Christian, Byzantine or modern. Described as "highly eccentric", Fourmont appears to have been suffering from mental illness while in Greece, and is reported to have deliberately destroyed many ancient artefacts and inscriptions, after first copying their texts, perhaps out of "misplaced patriotism". He was also accused of having invented or forged many of the inscriptions he claimed to have found, particularly in Sparta.

The main testimony for his destruction was provided by the early 19th century traveller Edward Dodwell (1767-1832), who in his account of his second visit to Greece reported that Fourmont was still remembered in Sparta for ordering the destruction of inscriptions, and went on to cite Fourmont's own letter in which he brags of his deeds.

"After I had taken copies of some of these inscriptions, I observed Manusaki turning them over and concealing them under stones and bushes. When I inquired his motive for such unusual caution, he informed me that he did it in order to preserve them, because many years ago a French milordos who visited Sparta, after having copied a great number of inscriptions, had the letters chiselled out and defaced. He actually pointed out to me some fine slabs of marble from which the inscriptions had evidently been thus barbarously erased.

The fact is generally known at Misithra, and it was mentioned to me by several persons as a received tradition. This must doubtless have been one of the mean, selfish, and unjustifiable operations of the Abbe Fourmont, who travelled in Greece by orders of Louis XV in the year 1729. In a letter to the Count de Maurepas, he boasts of having destroyed the inscriptions in order that they might not be copied by any future traveller. But it is conjectured by many, and perhaps not without reason, that his principal object in obliterating the inscriptions was, that he might acquire the power of blending forgery and truth without detection, and that his fear of competition was subordinate to that of being convicted of palaeographical imposture.

His manuscript journal and inscriptions are in the king's library at Paris.

See Lettres sur l'authenticité des inscriptions de Fourmont par Mons. Raoul-Rochette, à Paris, 1819. See the first letter, p. 11."

Edward Dodwell, A classical and topographical tour through Greece, during the years 1801, 1805 and 1806, Volume 2 (of 2), pages 405-408 and following pages. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819. At the Internet Archive.

For photos of the statues and the inscriptions as found by archaeologists, see:

Vinzenz Brinkmann, Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, Heinrich Piening, The Funerary Monument to Phrasikleia, in: V. Brinkmann, O. Primavesi, M. Hollein, (editors), Circumlitio. The Polychromy of Antique and Mediaeval Sculpture, Akten des Kolloquium Liebieghaus Frankfurt 2008, pages 188-217. PDF at the Liebieghaus Polychromy Research Project (formerly the website of Stiftung Archäologie).

4. H. G. Lolling on the Phrasikleia inscription and Aristion

See:

H. G. Lolling, Der Künstler Aristion, in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Volume 1, pages 174-175. Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1876. At the Internet Archive.

H. G. Lolling, Zum Grabstein der Phrasikleia, in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Volume 4, page 10. Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1879. At the Internet Archive.

5. The Xenophantos base

The dimensions of the base are those given by the museum. However the inscribed front of the block is clearly wider than it is high.

See, for example:

Charalambos B. Kritzas et al, The Greek script: Catalogue of an exhibition of copies (Χαράλαμπος Β. Κριτζάς, Η Ελληνική Γραφή: Κατάλογος έκθεσης αντιγράφων), No. 34, pages 73-74. Epigraphic Museum, Athens, 2003. An illustrated catalogue, in Greek and English, for a touring exhibition of facsimiles of ancient inscriptions and Byzantine manuscripts.

epigraphicmuseum.gr/ekdoseis/

6. The Kantza fragment

See:

Anton Raubitschek, Zu Altattischen Weihinschriften, Jahreshefte der Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts (Öjh), Beiblatt 31, 1938, col. 59 (IG I² 639).

Vasiliki Barlou, An itinerant Parian before Skopas: Aristion, Phrasikleia and the problem of regional styles. In: Dora Katsonopoulou and Andrew Stewart (editors), Skopas of Paros and his world: Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the Archaeology of Paros and the Cyclades, Paroikia, Paros, 11-14 June 2010, pages 111-132 (particularly pages 111-112 and notes 5-9). Athens, 2013. At academia.edu.

Barilou mentions that the fragment from Kalyvia may be in a storage magazine of the 2nd Ephorate of Antiquities in Athens. Another source states that it is in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens, but does not provide further details. So far I have found no further recent information about either of the inscriptions.

7. The Marble of the Siphnian Treasury

Isotopic ratio analyses of marble samples from monuments in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi have shown that the Siphnian Treasury was constructed with a range of white marbles. Naxian marble was used for the sima

and Parian marble for the pedimental sculptures, the east and west friezes and the caryatids.

See: Olga Palagia and Norman Herz, Investigation of marbles at Delphi. In: J. J. Hermann Jnr., N. Herz and R. Newman (editors), Asmosia 5: Ιnterdisciplinary studies οn ancient stone, pages 240-249. Archetype Publications Ltd., London, 2002. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|