1. Herodotus, "pater historiae"

The famous quote from On the laws (De Legibus, Book 1, section 5) by Cicero (Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106-43 BC) is followed by a caveat:

"Quintus: I understand you, my brother; you think that the laws which ought to bind a historian are quite different from those which require to be observed in a poem.

Marcus: Certainly; inasmuch as the main object of the former is truth in all its relations, while that of the latter is amusement; although in Herodotus, the father of history, and in Theopompus, we find innumerable fables [i.e. fabulous or incredible tales]."

C. D. Yonge (translator, editor), The Treatises of M. T. Cicero: On the nature of the gods; On divination; On fate; On the Republic; On the laws; and On standing for the consulship. On the laws, page 400. H. G. Bohn, London, 1853. At googlebooks.

In Yonge's translation Herodotus is described as "the father of Greek history", but the word Greek does not appear in the Latin original:

"Quintus: Intellego te, frater, alias in historia leges obseruandas putare, alias in poemate.

Marcus: Quippe cum in illa ad ueritatem, Quinte, quaeque referantur, in hoc ad delectationem pleraque; quamquam et apud Herodotum patrem historiae et apud Theopompum sunt innumerabiles fabulae."

Georges de Plinval (editor), M. Tullius Cicero, De legibus, Book 1, section 5 (in Latin). Belles Lettres, Paris, 1959. At Perseus Digital Library.

Theopompus of Chios (Θεόπομπος ο Χίος, circa 380-300 BC) was a Greek rhetorician and historian who studied at the school of rhetoric established by Isocrates on Chios. He wrote Hellenika (Ἐλληνικαὶ ἱστορίαι), a continuation of Thucydides, in 12 books covering the period from the Battle of Cynossema (Κυνὸς σῆμα) in 411 to the Battle of Knidos in 394 BC, and Philippika (Φιλιππικὰ), a history of Greece during the reign of Philip II of Macedon (359-336 BC) in 58 books. He also wrote several orations, including panegyrics in praise of Philip II and Alexander the Great, and may have written Epitome of the History of Herodotus (Ἐπιτομὴ τῶν Ἡρρδότου ἱστοριῶν). Only fragments of his works have survived.

2. Halicarnassus

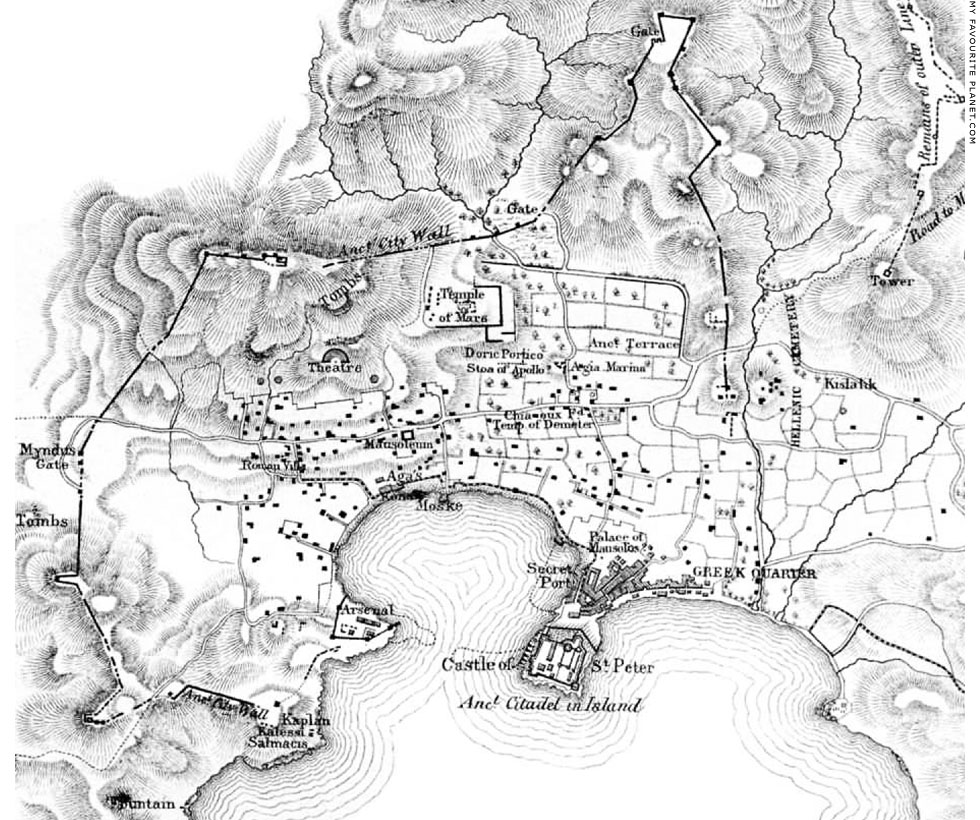

Halicarnassus (Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός, Halikarnassos or Αλικαρνασσός, Alikarnassos) was a city in Caria (Καρία), on the Aegean coast of southwestern Anatolia (Asia Minor), between Ionia (to the north) and Lycia (the south), and opposite the Dodecanese island of Kos.

It never played a significant role in ancient political events and knowledge of its history is scant. The prehistoric population was made up of peoples referred to as Carians and Leleges. There is evidence of a Greek presence in the area from the Mycenaean period, although larger scale colonization by Greeks appears to have begun in the 12th-11th centuries BC. The main settlement is thought to have been called Zephyria (Ζεφύρια, West Wind), on the small island between two bays, now joined to the mainland, on which the Castle of Saint Peter was built by the Knights of Rhodes in 1404. Another significant settlement or district was Salmakis (Σαλμακίς, see Panyassis), at the southwest of the western bay.

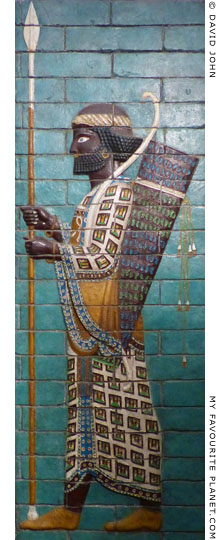

During the mid 6th century BC, along with the other Greek cities of the Aegean coast, it came under the control of the Lydian king Croesus until he was defeated by Cyrus II (the Great) of Persia in 547-546 BC. As part of the Persian Empire it was governed by local tyrants or satraps, the most famous being Mausolus (Μαύσωλος, 377-353 BC), whose tomb, known as the Mausoleum (see Pytheos), was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Two hundred years of Persian rule was ended when Caria was conquered in 334 BC by Alexander the Great. During Alexander's siege of the city it was devastated by fire, and although it was rebuilt it appears to have never to have fully recovered. Today it is the location of the modern port city Bodrum, in the Muğla Province of Turkey.

3. One of the notables of Halicarnassus

The phrase "Ἁλικαρνασεύς, τῶν ἐπιφανῶν", translated here as "of Halicarnassus; one of the notables", has also been interpreted as "Halicarnassian; one of the distinguished men of that place". It has been pointed out that this does not necessarily indicate that his social status there was high, but may refer to his later fame as a historian.

See: Jessica Priestley, Herodotus and Hellenistic culture: Literary studies in the reception of the Histories, page 20. Oxford University Press, 2014.

4. Artemisia, Pisindelis, Lygdamis I and Lygdamis II

Artemisia (Ἀρτεμισία, Artemisia I of Caria), the queen - a tyrant or dynast - of Halicarnassus in Persian controlled Caria, who fought on the side of the Persian king Xerxes I against the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. Herodotus mentioned her several times (see quote below), and wrote that her father was Lygdamis (Λύγδαμις Α', Lygdamis I of Halicarnassus), a tyrant or dynast in the late 6th or early 5th century BC, and that she had a young son. He did not name her husband or her son, who the Suda calls Pisindelis (Πισίνδηλις).

The second Lygdamis (Λύγδαμις, died circa 453/450 BC), often referred to as Lygdamis II (Λύγδαμις Β') of Halicarnassus, is described here and in the Suda entry for "Panyasis" (see the Panyassis page) as the "third tyrant of Halicarnassus", after Artemisia, in the 460s or mid-450s BC. He was the son or grandson of Artemisia, perhaps the son of Artemisia's son Pisindelis.

It was this Lygdamis from whom Herodotus fled into exile on Samos, and who is said to have executed his kinsman, the poet Panyassis, perhaps following an unsuccessful uprising. Herodotus is said to have later returned to Halicarnassus and helped overthrow Lygdamis.

He is sometimes referred to as Lygdamis III: Lygdamis I being the 6th century tyrant of Naxos and ally of Peisistratos, the tyrant of Athens; and Lygdamis II being Lygdamis I of Halicarnassus.

"I see no need to mention any of the other captains except Artemisia. I find it a great marvel that a woman went on the expedition against Hellas: after her husband died, she took over his tyranny, though she had a young son, and followed the army from youthful spirits and manliness, under no compulsion. Artemisia was her name, and she was the daughter of Lygdamis; on her father's side she was of Halicarnassian lineage, and on her mother's Cretan.

She was the leader of the men of Halicarnassus and Cos and Nisyrus and Calydnos, and provided five ships. Her ships were reputed to be the best in the whole fleet after the ships of Sidon, and she gave the king the best advice of all his allies. The cities that I said she was the leader of are all of Dorian stock, as I can show, since the Halicarnassians are from Troezen, and the rest are from Epidaurus."

Herodotus, Histories, Book 7, chapter 99. At Perseus Digital Library.

5. "The Transgressor" - Julian the Apostate

Emperor Julian II (Flavius Claudius Iulianus Augustus, 331/332 - 363 AD, reigned 361-363 AD), also known as Julian the Apostate, was the last pagan emperor and attempted to arrest the growing dominance of Christianity in the empire. He was also a philosopher and author in Greek. The letter quoted in the Suda is thought to be a fragment of one of Julian's many epistles, numbered 155 in the collection edited by I. Bidez and F. Cumont, published in 1922. Herodotus is also cited as "the Thurian historian" in No. 152 (Epistle 22):

"The Thurian historian said that men's ears are less to be trusted than their eyes." (Histories, Book 1, chapter 8)

I. Bidez and F. Cumont, Imp. Caesaris Flavii Claudii Iuliani, Epistulae, leges, poematia, fragmenta varia. Les Belles Lettres, Paris, and Oxford University Press, 1922.

Preface and main text In Latin, quotes in Greek. 152 (Epistle 22), pages 207-208; 155 "Ad ignotum (Suidas Herodotus)", page 209.

English translations of Julian's epistles, epigrams and orations can be found at www.tertullian.org:

Letter 11. To Leontius (No. 152 in Bidez-Cumont)

The shorter fragments, 1. From the Suda, under 'Ηρόδοτος and again under Ζηλωσαι (No. 155 in Bidez-Cumont)

6. Dung-eaters, fish-eaters and flesh-eaters

For the eaters of dung (bread from grain grown in manured soil), fish eaters (Ichthyophagoi, from Elephantine) and meat eaters (Ethiopians), see Histories, Book 3, chapters 19-25 and 30. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Herodotus and the Ionic dialect in Halicarnassus

The claim that Herodotus began writing in the Ionic dialect of Greek when he was in Samos, which like much in the Suda has been variously accepted and dismissed by modern scholars, may be derived from Herodotus' own statement that Halicarnassians were Dorian Greeks from Troezen, made when he was discussing Artemisia (see the quote above).

The fact that Herodotus added "as I can show" ("ἀποφαίνω", often translated as "I declare") suggests that he felt it necessary to emphasize that the Carians were of Dorian stock and that there may have been doubt about this in his time. It is now widely believed that Halicarnassus was founded by both Ionic and Dorian Greeks following the Doric invasion of the Peloponnese in the late 12th to 11th centuries BC, and that the Ionic dialect became prevalent there. Official inscriptions of the Classical period found at Halicarnassus are written in Ionic. Lucian of Samosata referred to Herodotus' language as "his native Ionic" [see note 12].

"On the neighbouring coast of Asia Minor Halicarnassus was founded by Dorians and Ionians from Troezen, Iasus by Dorians from the Argolid, and Cnidus by Dorians from Argolis and Lacedaemonia. These were the farthest outliers of the Dorian invasion. They held a cult of Triopian Apollo on the Cnidian promontory, to which only the Dorians of Cnidus, Halicarnassus, Cos, and the three towns of Rhodes (Lindus, Ialysus, and Cameirus) were admitted." *

"Doric was spoken during classical times in Aegina, Megaris, and the eastern Peloponnese from Sicyonia to Lacedaemonia: in Messenia, where its wide distribution may be partly due to the later conquest of Messenia by Sparta; in the southern Aegean islands; and on the adjacent coast of Asia Minor; except at Halicarnassus, where the settlers were of mixed stock and the Ionic dialect prevailed."

"In Troezen the Ionic dialect survived long enough to be perpetuated in her colony Halicarnassus."

N. G. L. Hammond, A history of Greece to 322 BC, pages 78-79 and 82. Oxford University Press, 1959.

* The Hexapolis, a confederacy of six Dorian colonies on the coast of Caria and the neighbouring islands, with its spiritual centre at the sanctuary of Triopian Apollo at Knidos, was comparable to the Ionian League of twelve Ionian cities which met at the sanctuary of Poseidon at Panionion. Halicarnassus was expelled from the Hexapolis shortly before the birth of Herodotus, and its government was united with that of the neighbouring islands of Kos, Kalydna and Nysirus under Artemisia.

At some point the island of Megisti (today Kastellorizo), off the coast of Lycia, southwestern Anatolia (Asia Minor), was also occupied by the Dorians and later came under control of Rhodes (see A brief history of Kastellorizo).

Pausanias recorded that the Halicarnassians honoured Troezen as their mother city (metropolis) by building a temple of Isis there:

"Having crossed the sanctuary, you can see a temple of Isis, and above it one of Aphrodite of the Height. The temple of Isis was made by the Halicarnassians in Troezen, because this is their mother-city, but the image of Isis was dedicated by the people of Troezen."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 32, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

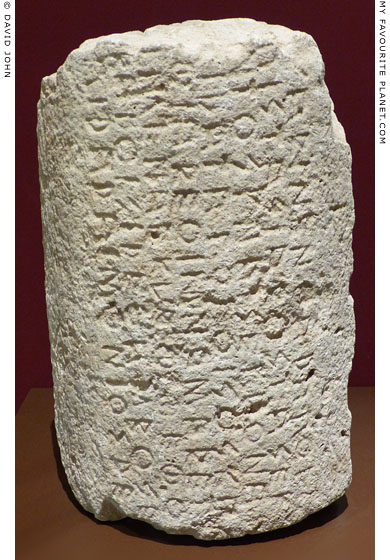

A fragment of white marble in the British Museum, found at Bodrum by Alfred Biliotti and dated to around the 3rd century BC, bears the remains of six lines of an inscription mentioning Troezen, the mother city of Halicarnassus.

British Museum. Inv. No. 2013,5017.73 (Inscription 891). Not on display.

See: C. T. Newton (editor), The collection of ancient Greek inscriptions in the British Museum, Part IV, Section I, Gustav Hirschfeld, Knidos, Halikarnassos and Branchidae, No. DCCCXCI (891), page 57. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1893.

It has been pointed out by several scholars that just about all Greek prose authors of the Classical period wrote in Ionic, including Hippocrates (Ἱπποκράτης, circa 460-370 BC), who was from Kos, another Doric settlement.

8. Herodotus in Athens

There has been much speculation about how long Herodotus spent in Athens and what he may have done there. It is thought that as a metic (foreign resident) he is unlikely to have enjoyed the rights of an Athenian citizen, particularly since a law of 451 BC restricted the granting of citizenship. However, he may have been befriended by eminent Athenians such as the playwright Sophocles and Pericles, who was a principal supporter of the colonization of Thurii. Plutarch quoted the opening of an epigram apparently meant to accompany a song composed by Sophocles at the age of 55 (around 442 BC) for Herodotus, possibly the historian rather than someone else of the same name:

"And here is a little epigram of Sophocles, as all agree:

'Song for Herodotus Sophocles made when the years of his age were

Five in addition to fifty.'"

Plutarch, An seni respublica gerenda sit, section 3 (Whether an old man should engage in public affairs). At Perseus Digital Library.

9. Jerome on Herodotus in Athens

Saint Jerome (Greek, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; Latin, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; circa 347-420 AD), was a priest from Illyria, and a prodigious writer on theology and history. He is best known for his Latin translation of most of the Bible (later known as the Vulgate), and his commentaries on the Gospels.

His Chronicle (Chronicon or Temporum liber, The Book of Times), a universal chronicle compiled in Constantinople around 380 AD, is a Latin translation of the chronological tables from the second part of the now lost Chronicon (Παντοδαπὴ Ἱστορία, Pantodape historia, Universal history), written in Greek by the theologian Eusebius of Caesarea (Ευσέβιος ο Καισαρείας, circa 260-339 AD). Eusebius' Chronicon covered the period from Abraham until 325 AD; Jerome's work added information up to 379 AD.

Jerome, Chronicle pp. 188-332, pages 194/195, 83rd Olympiad, 445 BC. Translated and edited by Roger Pearse and friends, Ipswich, UK, 2005. At tertullian.org.

10. Athenian wages

See: Robert Flaceliere, Daily life in Greece at the time of Pericles, translated from the French by Peter Green. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1965. Paperback edition, Phoenix Press, 2002. Page 130.

11. Plutarch, On the malice of Herodotus

The essay On the malice of Herodotus (Περὶ τῆς Ἡροδότου κακοηθείας) criticizing Herodotus for prejudice and misrepresentation has been attributed to Plutarch (Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), although some scholars believe it may have been written by Pseudo-Plutarch, a name given collectively to the author or authors whose works have been attributed to Plutarch.

Plutarch, De Herodoti malignitate, section 26. William W. Goodwin (editor), Plutarch’s Morals, Volume 4 (of 5). Little, Brown, and Company, Cambridge, MA, 1874. At Perseus Digital Library.

Diyllus (Δίυλλος) was an Athenian historian of the early 3rd century BC, who wrote a now lost history of Greece and Sicily in 26 or 27 books, covering events from the Third Sacred War (356-346 BC) to the death of Philip IV of Macedon (Φίλιππος Δʹ ὁ Μακεδών; died 297 BC), son of Cassander (Κάσσανδρος Ἀντιπάτρου, circa 350-297 BC).

Philippides (Φιλιππίδης) or Pheidippides (Φειδιππίδης) was the runner sent by the Athenians to Sparta to ask for help against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC (Histories, Book 6, chapter 105). See Athens Acropolis gallery page 4.

12. Lucian on Herodotus

Lucian of Samosata (circa 125 - after 180 AD, see Aetion). His claim that Herodotus recited the Histories at the Olympic Games has been refuted, although since Herodotus or Aetion is supposed to have been an introduction or lecture addressed to a large and learned audience in Macedonia, there must have been at least a few present who would have had an opinion on the matter.

"I wish it were possible to imitate Herodotus's other qualities too. I do not mean all and every one (this would be too much to pray for) but just one of them – whether the beauty of his diction, the careful arrangement of his words, the aptness of his native Ionic, his extraordinary power of thought, or the countless jewels which he has wrought into a unity beyond hope of imitation. But where you and I and everyone else can imitate him is in what he did with his composition and in the speed with which he became an established man of repute throughout the whole Greek world.

As soon as he sailed from his home in Caria straight for Greece, he bethought himself of the quickest and least troublesome path to fame and a reputation for both himself and his works. To travel round reading his works, now in Athens, now in Corinth or Argos or Lacedaemon in turn, he thought a long and tedious undertaking that would waste much time. The division of his task and the consequent delay in the gradual acquisition of a reputation did not appeal to him, and he formed the plan I suppose of winning the hearts of all the Greeks at once if he could.

The great Olympian games were at hand, and Herodotus thought this the opportunity he had been hoping for. He waited for a packed audience to assemble, one containing the most eminent men from all Greece; he appeared in the temple chamber, presenting himself as a competitor for an Olympic honour, not as a spectator; then he recited his Histories and so bewitched his audience that his books were called after the Muses, for they too were nine in number.

By this time he was much better known than the Olympic victors themselves. There was no one who had not heard the name of Herodotus – some at Olympia itself, others from those who brought the story back from the festival. He had only to appear and he was pointed out: 'That is that Herodotus who wrote the tale of the Persian Wars in Ionic and celebrated our victories.' Such were the fruits of his Histories. In a single meeting he won the universal approbation of all Greece and his name was proclaimed not indeed just by one herald but in every city that had sent spectators to the festival."

Herodotus or Aetion (Ἡρόδοτος ή Ἀετίων), pages 139-151 (this extract on pages 144-145), in Lucian, with an English translation by K. Kilburn, Volume VI (of eight). William Heinemann, London; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1959. Parallel texts in Greek and English. At the Internet Archive.

13. Markellinos on Herodotus' reading

Markellinos (Μαρκελλῖνος, also referred as Marcellinus), who probably lived around the 6th century AD, wrote a short Life of Thucydides, found in some of the ancient scholia (commentaries) on Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War.

The wording of the two versions of the story are so close that they must be from the same source.

See: Timothy Burns, Marcellinus’ Life of Thucydides, translated, with an introductory essay. In Interpretation, A journal of political philosophy, Volume 38 / Issue 1, pages 3-25. Queens College, Flushing, NY, 2010. (PDF document)

A shorter version of the same story appears elsewhere in the Suda:

"Organ, [Meaning] to desire [to swell with lust, to be eager]. Also [sc. attested is the participle] ὀργῶντες ['they being eager'] in Thucydides meaning they desiring. When Herodotus saw Thucydides weeping because of some enthusiasm, he said, 'I consider you fortunate, Olorus, for your success in fatherhood; for your son has a soul eager for learning.'"

Suda, Ὀργᾶν, omicron, 502. At Suda On Line.

14. Stephanus Byzantius on Herodotus' tomb in Thurii

Stephanus Byzantius, also known as Stephen of Byzantium (Στέφανος Βυζάντιος, Stephanos Byzantios; 6th century AD), the author of a geographical dictionary titled Ethnica (Ἐθνικά), of which only fragments have survived in an epitome compiled by a certain Hermolaus, who is otherwise unknown.

The text of the four-line inscription in Greek:

August Meineke, Stephanus Byzantinus, Ethnicorum quae supersunt (Ethnica), Θούριοι, pages 315-316. Reimer, Berlin, 1849. At the Internet Archive.

15. Markellinos on Herodotus' tomb in Athens

See the note above for the bibliographic reference and link.

Koile (Κοίλη, Hollow) was a deme of Athens, belonging to the Hippothontis (Ἱπποθοντίς) tribe, outside the Melitian Gate which led to the deme of Melite (Μελίτη Κεκροπίδας), in the west of Athens, north of the Pnyx. It is not certain that Thucydides returned to Athens from his exile in Thrace, or was buried there. Kimon was said to have died in Cyprus. The tombs, if they existed, may have been cenotaphs (symbolic empty grave monuments).

16. The muses and the Histories

Lucian is the earliest known writer to note the division of the Histories into nine books, each named after the muses.

See the note above for the quote, bibliographic reference and link.

It has been suggested that the division may have been made by a 1st century BC editor in Alexandria. An anonymous epigram, perhaps from this period, lends a poetical and mythological origin to the titling of the books:

"Ἡρόδοτος Μούσας ὑπεδέξατο: τῷ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἑκάστη

ἀντὶ φιλοξενίης βίβλον ἔδωκε μίαν."

"Herodotus entertained the Muses, and each,

in return for his hospitality, gave him a book."

William Roger Paton (translator), The Greek anthology, Volume III (of 5), Book IX, Epigrams, chapter 160, pages 84-85. Loeb Classical Library. William Heinemann, London; G. P. Putnam's sons, New York, 1915. Greek and English on facing pages. At the Internet Archive.

You can almost hear the clinking of teaspoons in china cups as Herodotus amuses the Muses in his crowded study.

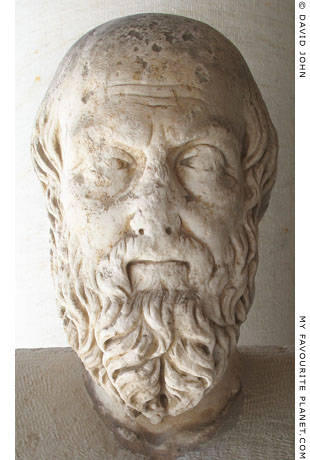

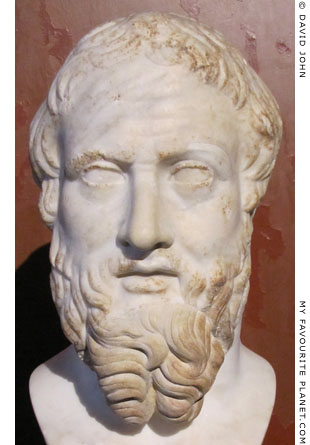

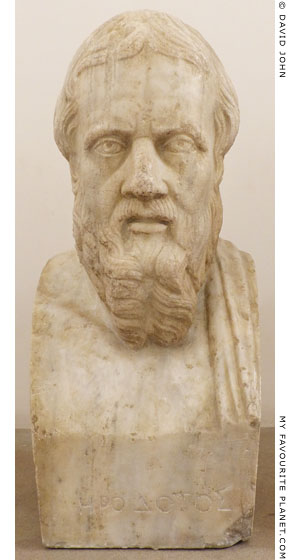

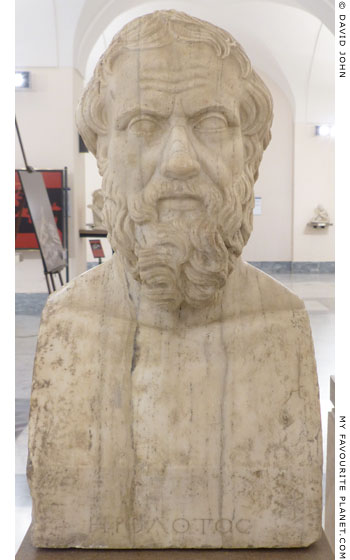

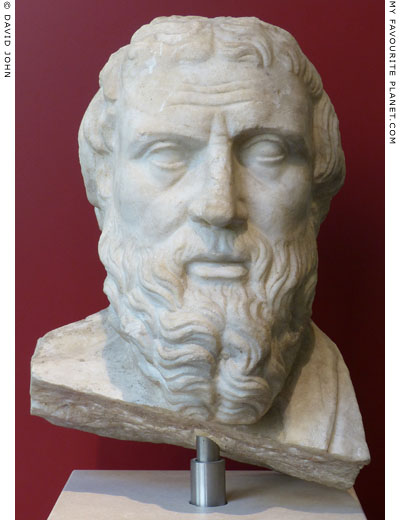

17. "Portraits" of Herodotus

As with several "portraits" of other famous ancient Greeks (see for example Homer, Panyassis and Thucydides), the extant sculptures depicting of Herodotus are thought to be works of imagination, made long after his death. In many cases the modern identifications of the persons depicted are also questionable.

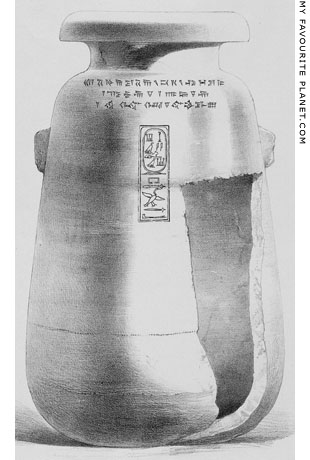

18. Alabastron inscribed with the name of Xerxes from Halicarnassus

According to Newton, the vase is identical to one in the Bibliothèque Impériale in Paris. A similar vase, also inscribed with the name of Xerxes, was excavated at Susa together with fragments of three others, and a porphyry vase with the name of Artaxerxes is in the Treasury of St. Mark's, Venice.

See: Sir Charles Thomas Newton and Richard Popplewell Pullan, A History of Discoveries at Halicarnassus, Cnidus and Branchidae.

Volume I, Plates, Plate VII. Day and Son, London, 1862. At University of Heidelberg Digital Library.

Volume II, Part 1, Chapter IV, pages 91-93. Day and Son, London, 1862. At the Internet Archive.

Volume II, Part 2, Appendix II: S. Birch, On the alabaster vase inscribed with the name of Xerxes, pages 667-670. Day and Son, London, 1863. At the Internet Archive.

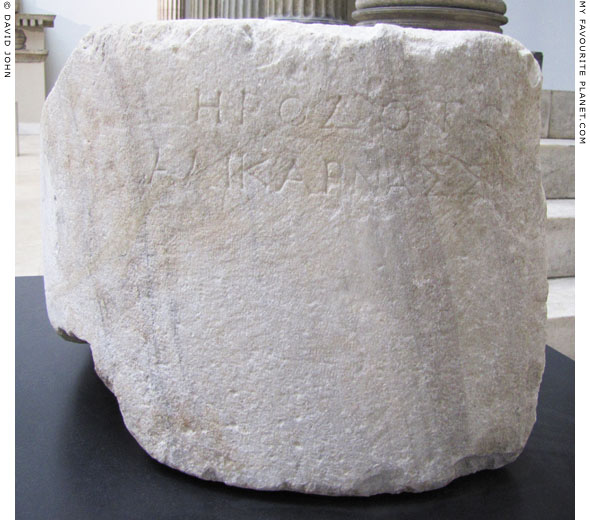

19. Bases of statues of writers from the Library of Pergamon

See: Max Fränkel, Altertümer von Pergamon, Band VIII, Band 1: Die Inschriften von Pergamon, Nos. 198-203, pages 117-121. Königliche Museen zu Berlin. W. Spemann, Berlin, 1890. |

|