|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Sculptors A-D |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 2 |

|

Page 2 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors A - D |

| |

| A B

C D |

The satirist and rhetorician Lucian of Samosata (circa 125-180 AD) wrote that as a youth he was sent to learn to be a sculptor from his uncle "who had the reputation of being an exellent sculptor". He thought it would be a piece of cake, but after the bitterly disappointing first day of his apprenticeship he had a dream in which two women appeared to him. The first introduced herself as "Sculpture" (or "the trade of Sculpture"; Ἑρμογλυφικὴ τέχνη, literally the art of carving Hermes statues), who attempted to persuade him of the benefits of a life as a sculptor. She is described as looking "like a workman, masculine, with unkempt hair, hands full of callous places, clothing tucked up, and a heavy layer of marble dust upon her, just as my uncle looked when he cut stone."

The second woman, "Education" (Παιδεία), more attractive, dignified and elegant, countered Sculpture's arguments, and warned him of the hardships and lowly status he would have to endure as a sculptor:

"What it shall profit you to become a sculptor, this woman has told you; you will be nothing but a labourer, toiling with your body and putting in it your entire hope of a livelihood, personally inconspicuous, getting meagre and illiberal returns, humble-witted, an insignificant figure in public, neither sought by friends nor feared by your enemies nor envied by your fellow citizens - nothing but just a labourer, one of the swarming rabble, ever cringing to the man above you and courting the man who can use his tongue, leading a hare's life, and counting as a godsend to anyone stronger.

Even if you should become a Phidias or a Polycleitus and should create many marvellous works, everyone would praise your craftsmanship, to be sure, but none of those who saw you, if he were sensible, would pray to be like you; for no matter what you might be, you would be considered a mechanic, a man who has naught but his hands, a man who lives by his hands."

The Dream or Lucian's Career (also known as The Vision; Greek, Περὶ τοῦ Ἐνυπνίου ἤτοι Βίος Λουκιανοῦ; Latin, Somnium sive Vita Luciani). In: Lucian, with an English translation by A. M. Harmon, Volume 3 (of 8), pages 218-223. Loeb Classical Library. William Heinemann, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1921. |

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Name / Biographical information |

|

Works / References |

|

| |

Adymos of Veroea

Ἅδυμος (Latin, Adymus)

1st century AD

From Veroea (Βέροια), Macedonia

He was the son of Evandros, perhaps

Evandros of Veroea.

It is thought that Evandros and Adymos belonged to a family of sculptors who undertook commissions around Macedonia and Thessaly. They both made grave monuments and, unusually, signed their name on them; most sculptors of the time remain anonymous. This suggests that they had a high reputation in the region. |

|

The only surviving sculpture by Adymos, is the lower part of a marble grave column, discovered in 1932 at the village of Marvinci, Valandovo, Republic of North Macedonia (near the border with Greece), probably the site of the ancient Paeonian city Idomeneo. It has a bas-relief of the lower part of a woman wearing a sleeved cloak, to the right of which is the inscription:

Ἅδυμος Εὐάνδρου Βεροιαῖος ἐποίει

Adymos, son of Evandros, of Veroea, made it.

Inscription SEG 18:272.

Skopje Archaeological Museum.

Height 31 cm, width 28 cm, depth 13 cm. |

|

| |

Aetion

Αετίων

(Sometimes erroneously referred to as Eetion, Hetion or Echion)

Sculptor and painter?

Mid 4th - early 3rd century BC

Perhaps from Amphipolis, Macedonia |

|

A sculptor named Aetion is known from references by Pliny the Elder, Theocritus and Callimachus. Aetion as a painter is mentioned by Cicero, Pliny and Lucian of Samosata, who described a painting of the Marriage of Alexander the Great and Roxana.

See the Aetion page for further details. |

|

|

| |

Agamedes of Argos (?)

Αγαμεδες Αργειος

Or Polymedes of Argos. The existence of either artist depends on the interpretation of a single, incomplete inscription.

Early 6th century BC, from Argos, northeastern Peloponnese

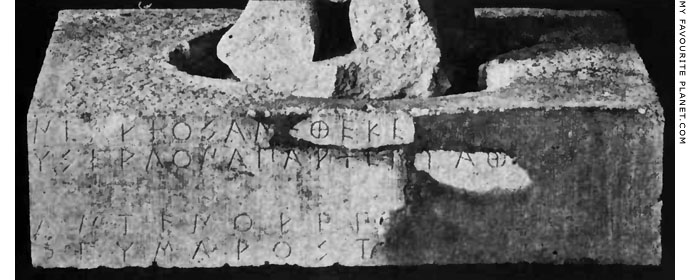

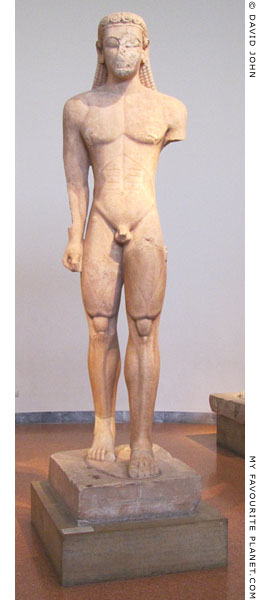

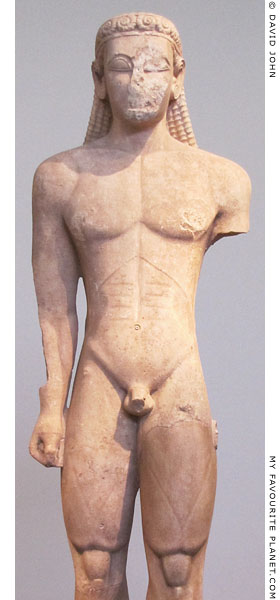

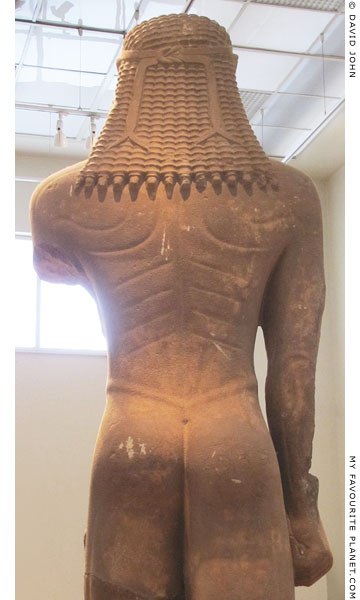

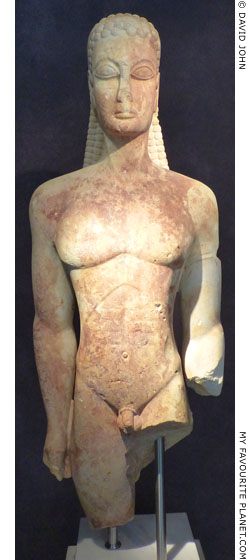

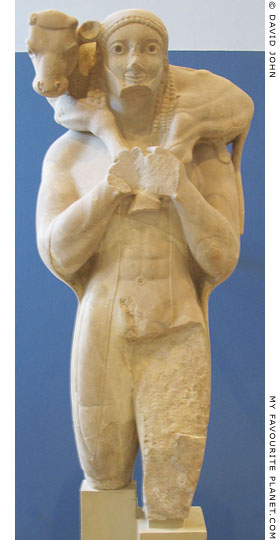

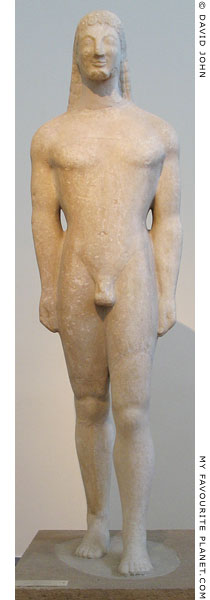

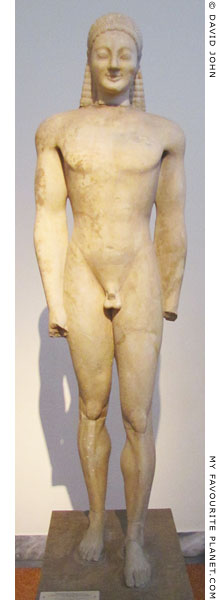

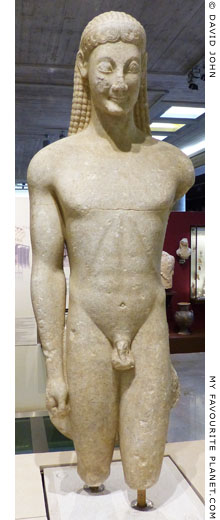

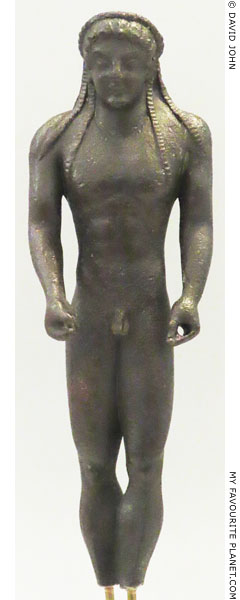

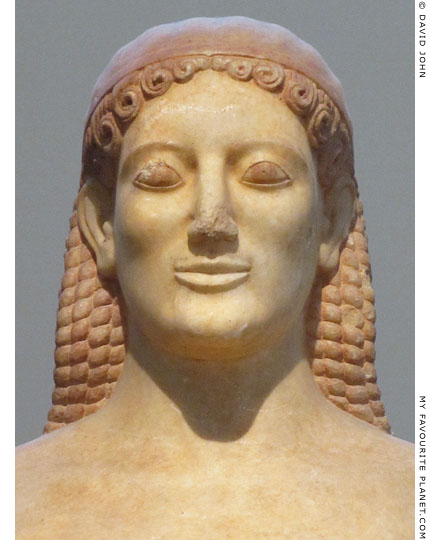

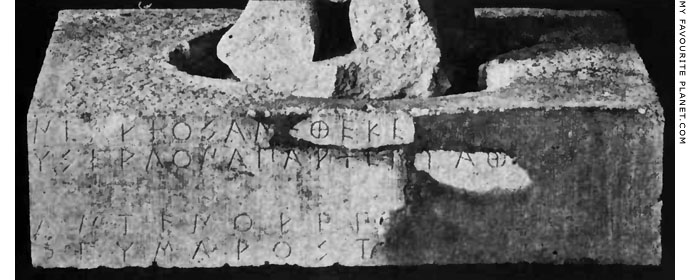

The base of one of the twin marble kouroi statues known as "Kleobis and Biton", excavated at Delphi and dated to around 580 BC, is inscribed with an artist's signature, the first letters of which are no longer legible:

[---]ΜΕΔΕΣ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΗ ΑΡΓΕΙΟΣ

([---]medes of Argos made me)

The name has been reconstructed by some scholars as Polymedes of Argos (Πολυμεδες Αργειος), while others believe it is Agamedes of Argos (Αγαμεδες Αργειος). Both these are otherwise unknown as names of sculptors.

Andrew Stewart is one of those who prefer Agamedes:

"Before Hageladas, the only known Argive sculptor is [Aga]medes, who signed the twins at Delphi ca. 580 (Delphi, Kleobis and Biton; Stewart 1990, figs. 56-57)."

Hageladas of Argos in the chapter The Archaic Period. In: Andrew Stewart, One Hundred Greek Sculptors, Their Careers and Extant Works. At Perseus Digital Library.

The statues were originally identified as the brothers Kleobis and Biton of Argos. Herodotus related the legend of the brothers and wrote that "the Argives made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best of men". (Histories, Book 1, chapter 31). However, this identification has been questioned, and according to one theory the statues may depict the Dioskouroi.

The brothers Agamedes and Trophonios (Ἀγαμήδης καὶ Τροφώνιος) are mentioned by ancient authors as the architects of the first temple of Apollo at Delphi. While the earliest temple is thought to have been built around the 7th century BC, the stories concerning these brothers are generally considered legend or myth. Strangely, one of the stories concerning their deaths is similar to that of Kleobis and Biton. |

|

|

| |

Ageladas of Argos

Ἀγελάδας; Ageladas or Hageladas; also Agelades (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19)

Working around 520-450 BC

From Argos, eastern Peloponnese

Pausanias mentioned a sculptor named Ageladas eight times (Description of Greece, books 4, 6, 7, 8, 10), six times as "Ageladas of Argos", who he said was a contemporary of Onatas and Hegias of Athens (Book 8, chapter 42, section 10).

The scholiast (commentator) on Aristophanes' Frogs (line 504), named Ageladas as the teacher of Pheidias. However, he also wrote that he made the statue of Herakles Alexikakos (Ἡρακλῆς Ἀλεξίκακος, the averter of evil) set up in the Attic deme of Melite to commemorate the deliverance from the great plague (87th Olympiad, 432 BC; two outbreaks in 430/429 and 427/426 BC, Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 2, chapter 47) during the Peloponnesian War. This is probably too late for the assumed dates of his career. It has been suggested that if the statue was by Ageladas, it may have been renamed or rededicated around the time of the plague.

(A statue of Apollo Alexikakos by Kalamis was set up around the same time in the Athenian Agora. See Kalamis 1.)

Pliny the Elder mentioned a sculptor named Agelades, working in bronze during the 87th Olympiad (432 BC), at the same time as Kallon (probably Kallon of Elis) and Gorgias the Laconian (see Gorgias), after the date he gave for Pheidias in the 83rd Olympiad (448 BC). He also wrote that he was the teacher of Polykleitos and Myron (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19).

In view of his estimated long career of around 70-80 years, it has been suggested that ancient authors may have been referring to two artists of this name, one from Argos and the other from Sikyon, or made errors in their attributions of works. Other scholars have seen the claims that he was the teacher of Pheidias, Myron, and Polykleitos as later traditions or inventions.

Pausanias mentioned three statues by Ageladas of Argos at Olympia, all thought to have been in bronze:

A statue of the pankration champion Timasitheos, from Delphi, who was later executed by the Athenians for his participation in the Spartan-backed attempt by the aristocrat Isagoras (Ἰσαγόρας) to establish a tyranny in 507 BC (also mentioned by Herodotus, Histories, Book 5, chapter 72).

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 8, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

The chariot of Kleosthenes, from Epidamnos, a victor in the 66th Olympic Games.

"Next to Pantarces is the chariot of Cleosthenes, a man of Epidamnus. This is the work of Ageladas, and it stands behind the Zeus dedicated by the Greeks from the spoil of the battle of Plataea. Cleosthenes' victory occurred at the sixty-sixth Festival, and together with the statues of his horses he dedicated a statue of himself and one of his charioteer. There are inscribed the names of the horses, Phoenix and Corax, and on either side are the horses by the yoke, on the right Cnacias, on the left Samus. This inscription in elegiac verse is on the chariot:

'Cleosthenes, son of Pontis, a native of Epidamnus, dedicated me

After winning with his horses a victory in the glorious games of Zeus.'

This Cleosthenes was the first of those who bred horses in Greece to dedicate his statue at Olympia."

Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 10, sections 6-8.

"... Ageladas of Argos made the statue of Anochus of Tarentum, the son of Adamatas, who won victories in the short and double foot-race."

Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 14, section 11.

Pausanias also wrote that Ageladas made the cult statue of Zeus in the sanctuary of Zeus Ithomatas on Mount Ithome, the ancient acropolis of Messenia.

"The statue of Zeus is the work of Ageladas, and was made originally for the Messenian settlers in Naupactus."

Description of Greece, Book 4, chapter 33, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Refugees from Messene, southwest Peloponnese, fleeing from Spartan domination at the end of the Third Messenian War, were settled by the Athenians at Naupaktos (Ναύπακτος), on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, in 456/455 BC. The statue of Zeus would then have been either one of the last works of Ageladas of Argos or by the conjectural Ageladas of Sikyon.

Ageladas made bronze statues of Zeus and Herakles for the city of Aigion (Αἴγιον), Achaia in the northwestern Peloponnese.

"There are at Aegium other images made of bronze, Zeus as a boy and Heracles as a beardless youth, the work of Ageladas of Argos."

Description of Greece, Book 7, chapter 24, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

At Delphi, Pausanias reported on two statue groups dedicated by the Spartan colony Tarentum (Greek, Τάρᾱς, Taras; today Taranto), Apulia, southern Italy. He said the first was by Ageladas of Argos.

"The bronze horses and captive women dedicated by the Tarentines were made from spoils taken from the Messapians, a non-Greek people bordering on the territory of Tarentum, and are works of Ageladas the Argive."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 10, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

The second statue group, made by Onatas of Aegina and perhaps Ageladas of Argos, depicted cavalry and infantry standing by Taras and Phalanthos bestriding the slain native king Opis.

"The Tarentines sent yet another tithe to Delphi from spoils taken from the Peucetii, a non-Greek people. The offerings are the work of Onatas the Aeginetan, and Ageladas the Argive, and consist of statues of footmen and horsemen – Opis, king of the Iapygians, come to be an ally to the Peucetii. Opis is represented as killed in the fighting, and on his prostrate body stand the hero Taras and Phalanthus of Lacedaemon, near whom is a dolphin. For they say that before Phalanthus reached Italy, he suffered shipwreck in the Crisaean sea, and was brought ashore by a dolphin."

Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 13, section 10.

However, the Greek text of this passage is corrupt and the name of the second artist is unclear. It has also been conjecturally interpreted as Kalliteles (Καλλιτέλης) or Kalynthos (Κάλυνθος). Kalliteles has been suggested because Pausanias mentioned him as Onatas' assistant on a statue of Hermes Kriophoros at Olympia, while Kalynthos is unknown as an artist in ancient literature. See the Onatas of Aegina page for further details.

Statues of three Muses as personifications of the diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic styles of Greek music by Aristokles, Kanachos and Ageladas were described in an epigram by the Greek poet Antipater of Sidon (Ἀντίπατρος ὁ Σιδώνιος) in the 2nd century BC.

"Three are we, the Muses who stand here; one bears in her hands a flute, another a harp, and the third a lyre. She who is the work of Aristocles holds the lyre, Ageladas' Muse the harp, and Canachas' the musical reeds. The first is she who rules tone, the second makes melody of colour, and the third invented skilled harmony."

William Roger Paton (translator), The Greek Anthology, Volume 5 (of 5), Book 16, Epigrams of the Planudean Appendix, No. 220, pages 290-291. In Greek and English. William Heinemann, London; G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1925. At the Internet Archive.

It is not known where these statues stood or whether they were all made at the same time, perhaps as a collaboration between three sculptors. |

|

|

| |

Agesander of Rhodes

Άγήσανδρος

(Referred to as Agesandros, Hagesander, Hagesandros, Hagesanderus)

From Rhodes, 1st century BC - 1st century AD, Roman Imperial period

The marble statue group "Laocoön and his sons" (see below), now in the Vatican Museums, is thought to be the work praised by Pliny the Elder, who wrote that it was made by three Rhodian artists, Hagesander, Polydorus and Athenodorus. Pliny is the only ancient author to mention them. After listing a number of marble sculptures by Greek artists, many of which had been taken to Rome, he stated:

"Beyond these, there are not many sculptors of high repute; for, in the case of several works of very great excellence, the number of artists that have been engaged upon them has proved a considerable obstacle to the fame of each, no individual being able to engross the whole of the credit, and it being impossible to award it in due proportion to the names of the several artists combined. Such is the case with the Laocoön, for example, in the palace of the Emperor Titus, a work that may be looked upon as preferable to any other production of the art of painting or of statuary. It is sculptured from a single block, both the main figure as well as the children, and the serpents with their marvellous folds. This group was made in concert by three most eminent artists, Hagesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, natives of Rhodes."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

The names in the Latin text are "Hagesander et Polydorus et Athenodorus rhodii".

The style of the Laocoön Group has been described as "Hellenistic Baroque" or "Pergamene Baroque" and compared with other Hellenistic sculptures such as the reliefs on the Great Altar of Zeus in Pergamon. It is thought that it was made around the first century AD, perhaps before 79 AD, as a copy of a bronze sculpture created around 200 BC in Pergamon.

The Sperlonga sculptures, a collection of fragmented colossal marble statue groups, each depicting a scene of Odysseus' adventures from Homer's Odyssey, was discovered in 1957 in a grotto at the Villa of Emperor Tiberius at Sperlonga (ancient Spelunca), on the west coast of Italy, between Rome and Naples. The Scylla Group, dated to before 26 AD, depicts Odysseus' ship being attacked by the monster Skylla. A signature inscribed on the side of a panel on the ship names the three Rhodian sculptors:

Ἀθαν[ό]δωρος

Ἁγησάνδρ[ο]υ

καὶ

Ἁγήσανδρο[ς]

Πα[ιω]νίου

κ[α]ὶ

Π[ο]λ[ύ]δωρος

Πολυ[δ]ώρου

Ῥόδιο[ι] ἐποίησα[ν].

"Athanadoros, son of Agesandros, and Agesandros, son of Paionios, and Polydoros, son of Polydoros, Rhodians, made this."

Inscription SEG 19:623 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

These may be the three artists mentioned by Pliny, although this has been much debated.

The sculptures also include a group depicting Odysseus blinding the Cyclops Polyphemos.

It has been suggested that the three sculptors were copyists, and also that there may have been more than one Agesander, possibly members of the same family. Scholars have attempted to identify the one or more Agesanders on the grounds of artistic style and from these inscriptions, as well as others found in Rhodes and elsewhere.

The signature of a sculptor named Athanadoros, son of Agesandros has been recorded on a number of undated bases found in Italy:

Ἀθανόδωρος Ἀγησά[νδρ]ου

Ῥόδιος ἐποίησε.

Inscription IG XIV 1227. From Nettuno, Antium (Anzio), central Italy.

[Ἀθανό]δωρος Ῥόδιο[ς]

ἐποίησε.

Inscription IG XIV 1228. Provenance unknown. Now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

[Ἀθαν]όδωρος Ἀγησάνδρου

[Ῥ]όδιος ἐποίησε.

Inscription IG XIV 1230. At Ostia, near Rome. |

|

|

| |

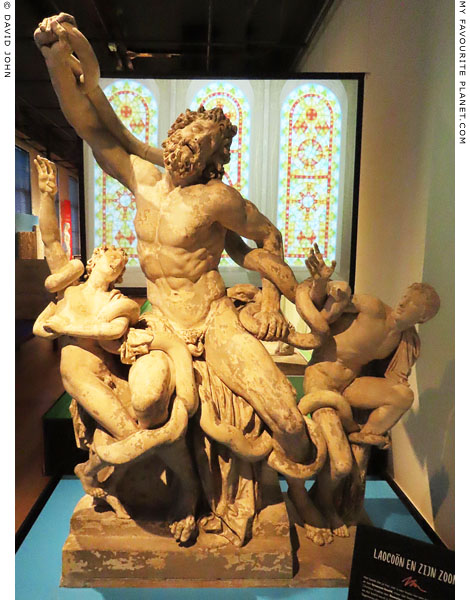

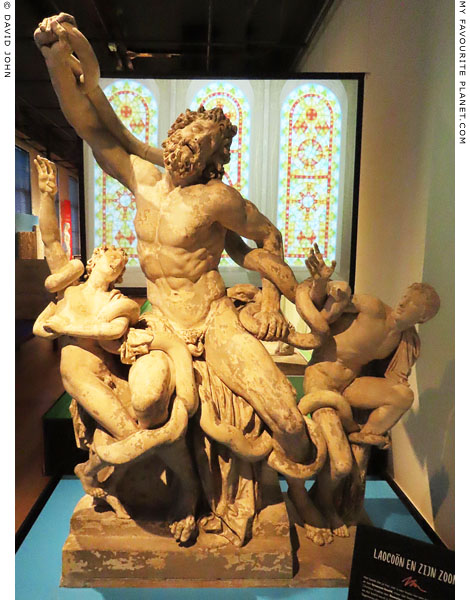

A plaster cast of the statue group "Laocoön and his sons"

by Agesandros, Athenodoros and Polydoros.

1st century BC - 1st century AD, perhaps a copy of

a group made around 200 BC. Height 184 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

The original is in the Cortile Ottagono, Museo Pio-Clementino,

Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. Nos. 1059, 1064, 1067. |

| |

A modern copy of the statue group "Laocoön and his sons" in Rhodes.

Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes. |

| |

"Laocoön and his sons" (also known as the "Laocoön Group") was discovered on 13th January 1506 by Felice de Fredi on his vineyard, in a vault below the Place de Sette Sale, near Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. This was the site of part of the palace of Titus, in which Pliny said it stood. Michelangelo Buonarroti and the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo were among those who witnessed the excavation of the sculpture. Fredi ceded it to Pope Julius II, who awarded him a pension, and it was set up in a courtyard of the Belvedere, Rome.

The group is not made of a single block as Pliny claimed, although it has been suggested that originally the joints in the sculpture may not have been not apparent to viewers. Several parts of the figures were missing, and replaced during a number of restorations. Laocoön's right arm was replaced in 1532 by Giovanni Antonio Montorsoli, a pupil of Michelangelo, with one which was outstretched to the right. Two plaster casts commissioned around 1750-1770 by Anton Raphael Mengs (see note on the Niobe page), one now in Dresden, the other in Florence, record the restored sculpture as it appeared in the mid 18th century (Moritz Kiderlen (editor), Die Sammlung der Gisabgüsse von Anton Raphael Mengs in Dresden, page 95, table 6, No. XXIII. Dresden, 2006).

In 1798 the sculpture was taken by Napoleon's troops to Paris and exhibited in the Louvre. On its return to Rome in 1816, it was further restored by Antonio Canova. The plaster cast in Amsterdam and others were made from this version of the work. In 1905 part of the original arm was found by chance in a builder's yard in Rome by the archaeologist and art dealer Ludwig Pollak, director of the Barracco Museum. This was eventually added to the statue in 1960, and during a major restoration in the 1980s other moden additions were also removed.

The sculpture depicts the Trojan seer Laocoön, priest of the Thymbraean Apollo, and his two sons being killed by two giant serpents. There were several ancient versions of the story of Laocoön's death, including those related by Arctinus (the earliest surviving version), Sophocles (in a lost tragedy), Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Quintus Smyrnaeus, Virgil, Servius, Pseudo-Apollodorus, Hyginus and John Tzetzes. It is not known which version may have inspired the work.

According to Virgil (Aeneid, Book 2) Laocoön warned the Trojans of the Wooden Horse with the words: "Equo ne credite, Teucri. Quidquid id est, timeo Danaos et dona ferentes." ("Do not trust the horse, Trojans! Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks, even bringing gifts.") Poseidon (god of the sea and of horses) then sent two sea serpents to strangle him and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. However, Apollodorus (Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheka, Epitome, chapter 5, sections 17-18) wrote that the two serpents were sent by Apollo because Laocoön had enraged him by sleeping with his wife in front of the divine image.

See:

Bernard Andreae, 36. Die Lakoongruppe, in: Schönheit des Realismus: Auftraggeber, Schöpfer, Betrachter hellenistischer Plastik, pages 213-229. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein, 1998. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

|

Agorakritos of Paros

Ἀγοράκριτος (Latin, Agoracritus)

From Paros; he worked in Athens around 436-424 BC.

According to Strabo and Pliny the Elder, Agorakritos was from the Cycladaic island of Paros. Pliny wrote that he was a pupil of Pheidias at the same time as Alkamenes, adding that he was a "great favourite" of his teacher. Pausanias went further and referred to him as Pheidias' lover (ἐρωμένος, eromenos).

Pliny mentioned a marble statue of Nemesis (Νέμεσις, Retribution) by Agorakritos at Rhamnous (Ῥαμνοῦς), north of Marathon, northeastern Attica (see below) as well as a statue in the Temple of the Great Mother in Athens. The latter is believed to have been a statue of Kybele (Κυβέλη) in the Metroon (Μητρῷον, a sanctuary dedicated to a mother goddess) in the Agora, which also housed the archives of the city.

"Another disciple also of Phidias was Agoracritus of Paros, a great favourite with his master, on account of his extremely youthful age; and for which reason, it is said, Phidias gave his own name to many of that artist's works.

The two pupils entering into a contest as to the superior execution of a statue of Venus [Aphrodite], Alcamenes was successful; not that his work was superior, but because his fellow citizens chose to give their suffrages in his favour in preference to a stranger. It was for this reason, it is said, that Agoracritus sold his statue, on the express condition that it should never be taken to Athens, and changed its name to that of Nemesis. It was accordingly erected at Rhamnus, a borough of Attica, and M. Varro has considered it superior to every other statue.

There is also to be seen in the Temple of the Great Mother [Kybele], in the same city, another work by Agoracritus."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Strabo recorded that some sources attributed the statue of Nemesis to Agorakritos while others credited Diodotus (otherwise unknown):

"Rhamnus has the statue of Nemesis, which by some is called the work of Diodotus and by others of Agoracritus the Parian, a work which both in grandeur and in beauty is a great success and rivals the works of Pheidias."

Strabo, Geography, Book 9, chapter 1, section 17. At Perseus Digital Library.

Some modern scholars have rejected Pliny's tale of a competition with Alkamenes and doubted the idea that a statue of Aphrodite could be modified to depict Nemesis.

Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 33) wrote that Pheidias made a statue of Nemesis for her sanctuary at Rhamnous from a block of Parian marble the Persians had brought to Attica to make a victory trophy, and had presumably abandoned following their defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC (see the first Persian invasion of Greece). He also described the relief on the base of statue, fragments of which have survived, depicting the mythical scene Helen of Troy being led by Leda (her mother) to Nemesis (in some myth versions her real mother, see the Dioskouroi page), attended by associated figures, including Tyndareos and his children, as well as Agamemnon, Menelaos and Pyrrhus (also known as Neoptolemos), the son of Achilles.

"[2] About sixty stades from Marathon as you go along the road by the sea to Oropus stands Rhamnus. The dwelling houses are on the coast, but a little way inland is a sanctuary of Nemesis, the most implacable deity to men of violence. It is thought that the wrath of this goddess fell also upon the foreigners who landed at Marathon. For thinking in their pride that nothing stood in the way of their taking Athens, they were bringing a piece of Parian marble to make a trophy, convinced that their task was already finished.

[3] Of this marble Pheidias made a statue of Nemesis, and on the head of the goddess is a crown with deer and small images of Victory. In her left hand she holds an apple branch, in her right hand a cup on which are wrought Aethiopians. As to the Aethiopians, I could hazard no guess myself, nor could I accept the statement of those who are convinced that the Aethiopians have been carved upon the cup be cause of the river Ocean. For the Aethiopians, they say, dwell near it, and Ocean is the father of Nemesis."

Sections 4-6 are a digression about the geography of Ocean.

"[7] Neither this nor any other ancient statue of Nemesis has wings, for not even the holiest wooden images of the Smyrnaeans have them, but later artists, convinced that the goddess manifests herself most as a consequence of love, give wings to Nemesis as they do to Love. I will now go onto describe what is figured on the pedestal of the statue, having made this preface for the sake of clearness. The Greeks say that Nemesis was the mother of Helen, while Leda suckled and nursed her. The father of Helen the Greeks like everybody else hold to be not Tyndareus but Zeus.

[8] Having heard this legend Pheidias has represented Helen as being led to Nemesis by Leda, and he has represented Tyndareus and his children with a man Hippeus by name standing by with a horse. There are Agamemnon and Menelaus and Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles and first husband of Hermione, the daughter of Helen. Orestes was passed over because of his crime against his mother, yet Hermione stayed by his side in everything and bore him a child. Next upon the pedestal is one called Epochus and another youth; the only thing I heard about them was that they were brothers of Oenoe, from whom the parish has its name."

Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 33, sections 2-3 and 7-8. At Perseus Digital Library.

Byzantine writers (John Tzetzes, Chiliades, 7, 154; Suidas; Photius) said that Pheidias made the Nemesis and presented it to his favourite pupil Agorakritos.

Parts of a statue head in the British Museum and fragments of reliefs from a pedestal in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens are thought to be parts of the statue of the Rhamnous Nemesis, but are said to be of Pentelic rather than Parian marble.

Again, according to Pausanias (and Arrian, Periplous, 9) the cult statue in the Metroon, the sanctuary of the Mother of the gods (Μητηρ Θεων, Meter Theon), on the southwest side of the Athens Agora was made by Pheidias.

"Here is built also a sanctuary of the Mother of the gods; the image is by Pheidias."

Pausanias, (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

It is thought that the cult statue depicted Kybele enthroned, with a lion attendant, and holding a tympanon (drum). Several dozen dedicatory reliefs of this image, perhaps based on the statue, have been found in the Agora (see photo below). It may have been the model for large number of images of Kybele, made all over the Graeco-Roman world into late Antiquity. The type originated in much more ancient Anatolian depictions of the enthroned Phrygian mother goddess, the oldest known example of which may be a terracotta statue, dated to around 6000 BC, from Çatalhöyük, Turkey, now in the Ankara Archaeological Museum.

From around the 7th century BC, the Kybele cult was adopted by Greeks in Anatolia (Asia Minor), from where it spread to Thrace (e.g. Samothraki) and central Greece (e.g. Thebes), and was finally accepted by the Athenians in the 5th century BC. The statue in the Agora is thought to have been made around 440-420 BC, presumably shortly after the sanctuary was established.

The confusion surrounding the authorship of this statue and the Nemesis at Rhamnous appears to be reflected in the comment by Pliny that "Phidias gave his own name to many of that artist's works" and the Byzantine claim that Pheidias gave his Nemesis to Agorakritos. It seems unlikely that two statues of each goddess, one by Pheidias and the other by Agorakritos, were commissioned for or purchased by the respective sanctuaries around the same time. (The temple of Apollo Patroos in the Agora had three statues of Apollo, although two stood outside, and they were made over a longer period. See Kalamis.) The literary sources lead one to speculate that in each case a statue by Pheidias may have been attributed to Agorakritos or vice versa.

Pausanias also reported that Agorakritos made bronze statues of Athena Itonia and Zeus for the goddess' temple near Koroneia (Κορώνεια), Boeotia.

"Before reaching Coroneia from Alalcomenae we come to the sanctuary of Itonian Athena. It is named after Itonius the son of Amphictyon, and here the Boeotians gather for their general assembly. In the temple are bronze images of Itonian Athena and Zeus; the artist was Agoracritus, pupil and loved one [ἐρωμένος, eromenos] of Pheidias."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 34, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

It has been suggested that extant Roman period marble sculptures of the Athena Hope-Albani/Farnese type may be copies of the bronze cult statue of Athena Itonia by Agorakritos. However, some scholars believe the original was the statue of Athena Hygieia which stood near the entrance to the Athens Acropolis (see Pyrrhos of Athens for further details).

Other works attributed to Agorakritos and his school or workshop include:

A fragment of a marble statue group from Rhamnous, circa 430-420 BC (see photo below). Two feet and the bottom of a woman's garment, from a group of two figures depicting the abduction of the Nymph Oreithyia by Boreas, which was part of the central akroterion of the temple of Nemesis at Rhamnous. Attributed to Agorakritos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 2348.

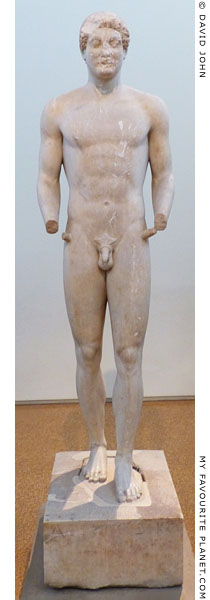

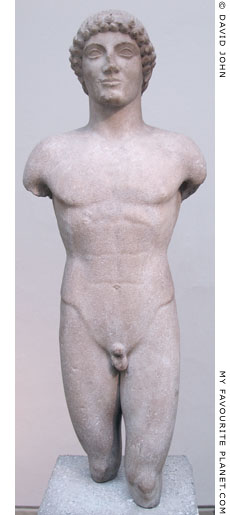

A marble statue of a youth from Rhamnous, circa 450-400 BC (see photo, above right). Probably Neanias, a local hero of Marathon. Probably a work of the school of Agorakritos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 199.

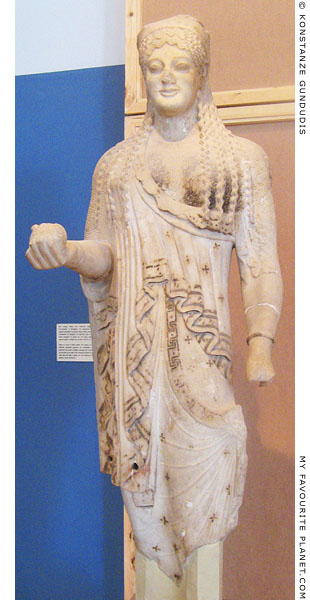

A marble statue of Demeter from Eleusis, circa 420 BC, is thought to have made in the workshop of Agorakritos. Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5076.

A marble statue of Persephone, circa 420-410 BC, found in Piraeus, is attributed to the school of Agorakritos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 176.

A funerary relief found on Aegina (see photo below), possibly by a pupil of Agorakritos. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 715. |

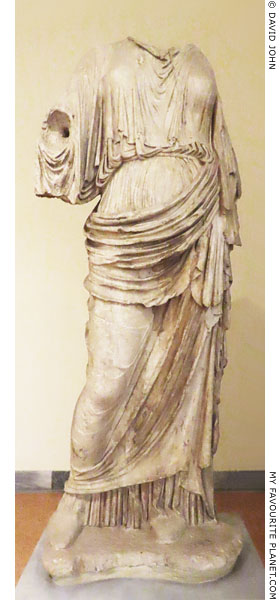

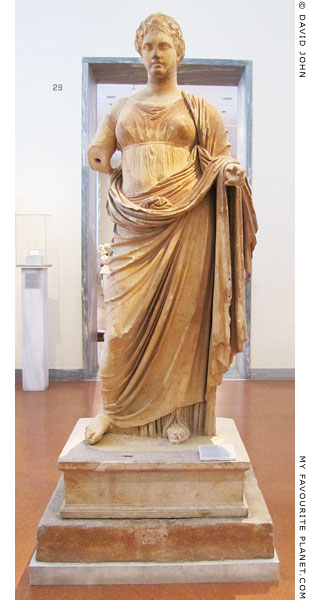

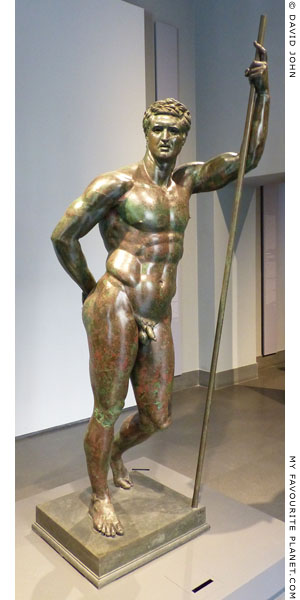

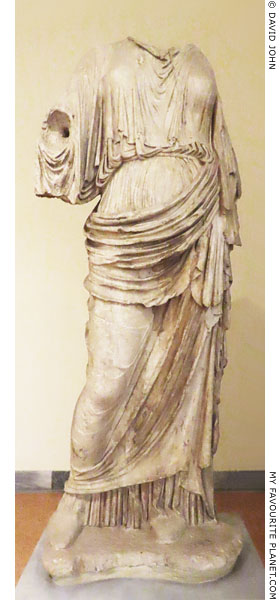

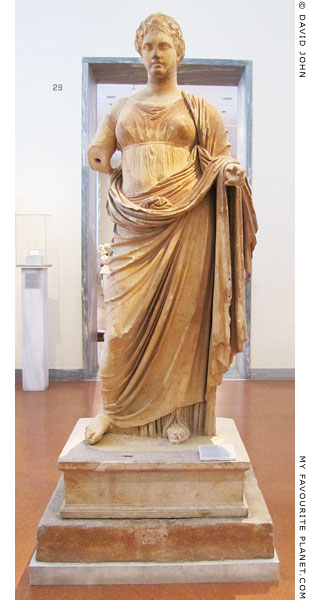

A marble statue of a female, believed

to be a Roman period copy of the cult

statue of Nemesis of Rhamnous, made

by Agorakritos of Paros around 430 BC.

The original depicted the goddess

holding an apple branch and a phiale.

2nd century AD. Found in Athens.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3949. |

| |

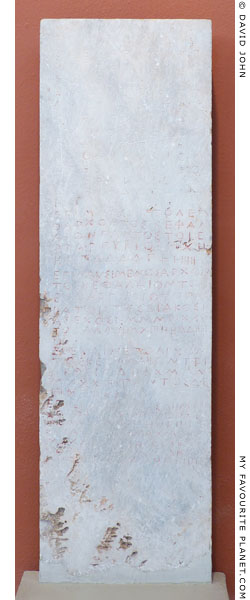

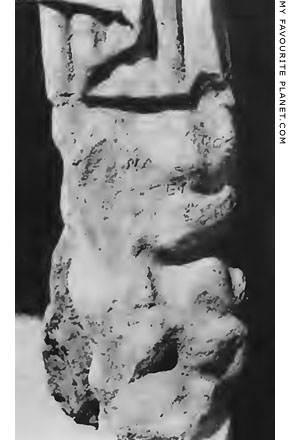

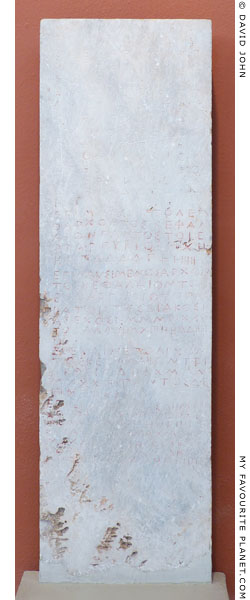

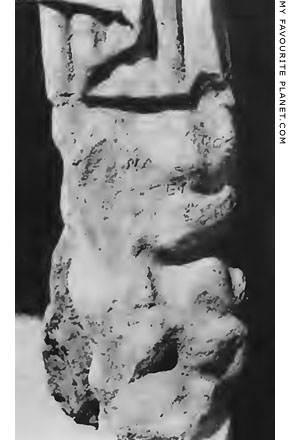

A marble stele inscribed with

the accounts of the sanctuary

of Nemesis at Rhamnous, Attica.

450-440 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. EM 12863.

Inscription IG I³ 248. |

| |

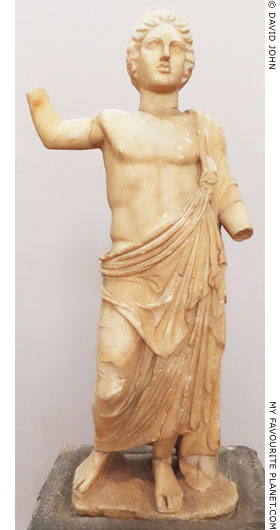

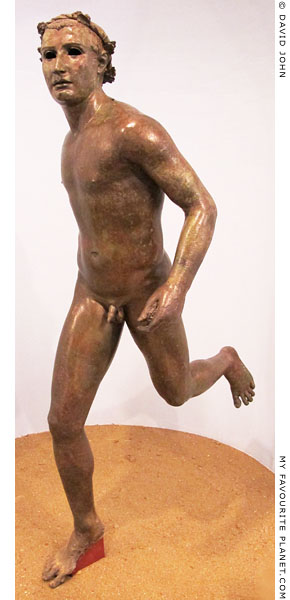

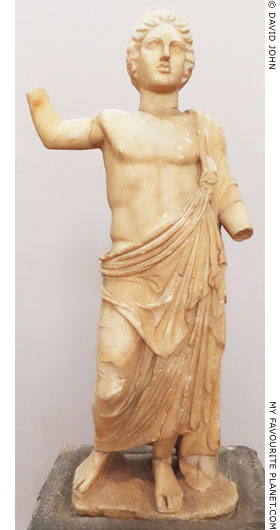

A marble statue of a youth, probably

Neanias (Νεᾱνίᾱς, young man). (At

Marathon Neanias and an unnamed

hero, recieved a third of the sacrificial

budget.) a local hero of Marathon.

Believed to be a work of the school of

Agorakritos. The smaller than lifesize

statue stands on a tall, dark marble

pedestal inscribed with a dedication

to "the goddes" (Nemesis or Themis?)

by Lysikleides, son of Epandrides.

Λυσικλείδης ἀνέθηκ-

εν Ἐπανδρίδο ὑὸς ἀπ{ο}

ἀρχὴν τόνδε θε<ᾶ>ι τῆι-

δε ἣ τόδ’ <ἔ>χει τέμενος

Inscription IG I³ 1021 (also IG I² 828,

Pouilloux, Forteresse de Rhamnonte 36)

Around 450-400 BC. Found in 1890

in the Temple of Themis, Rhamnous.

Pentelic marble. Height 93cm..

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 199. |

| |

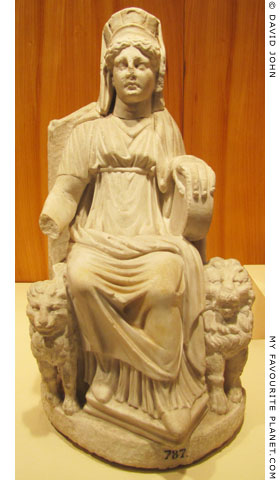

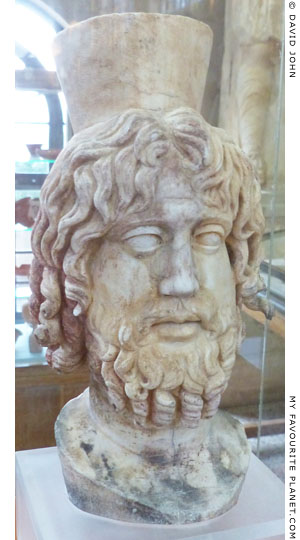

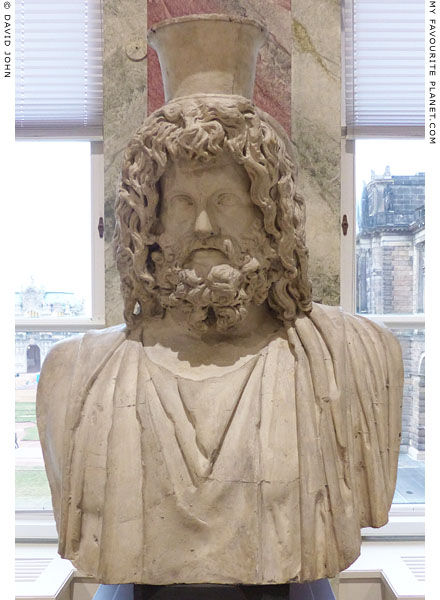

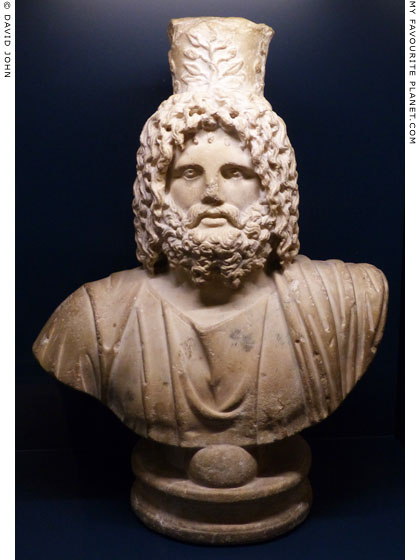

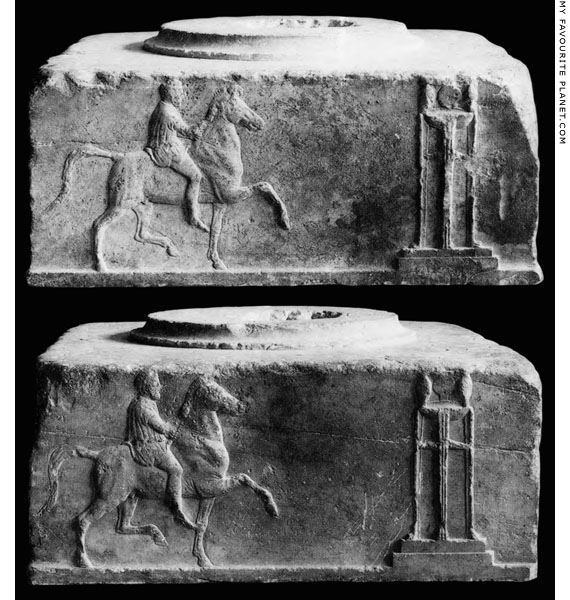

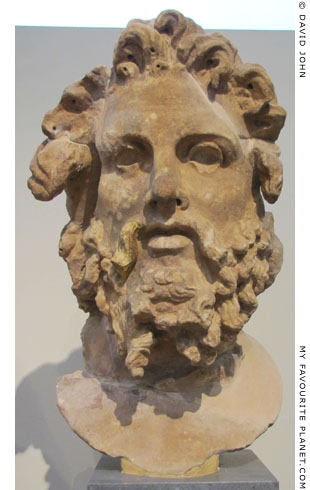

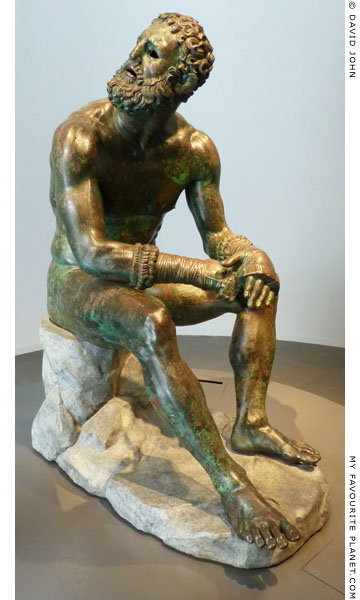

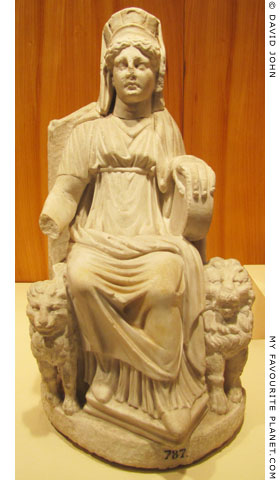

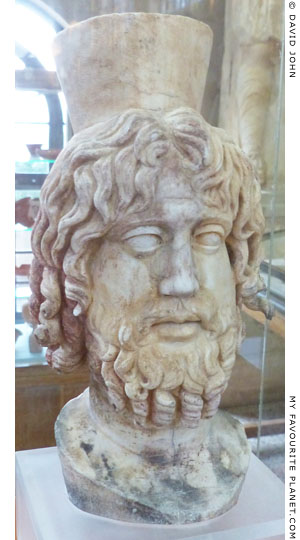

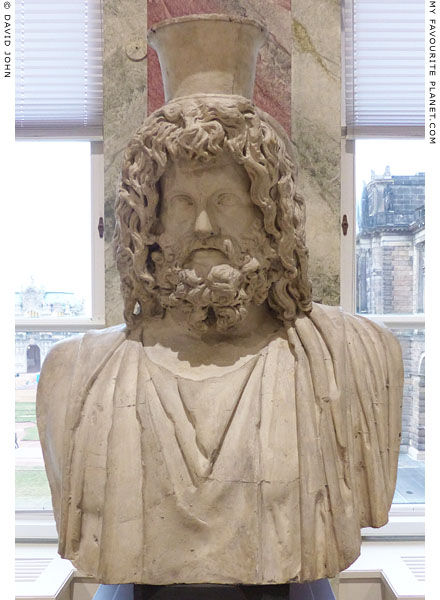

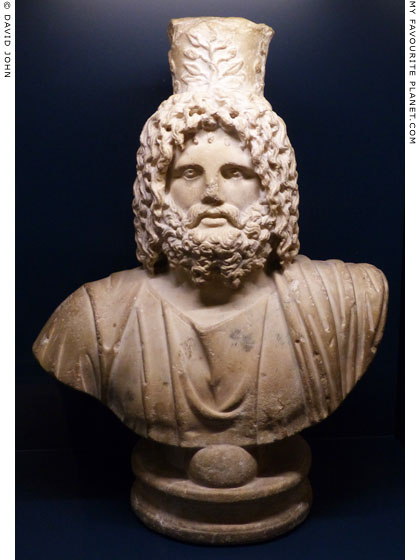

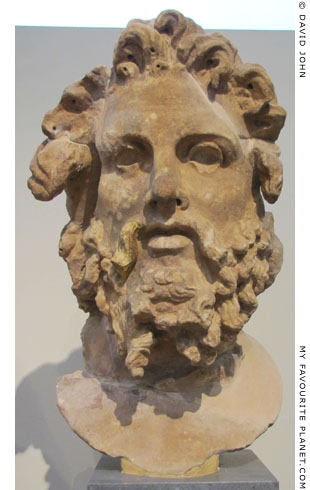

Marble statuette of Kybele sitting

on a throne, on either side of which

is a seated lion. She wears a polos

(or mural crown) and holds a

tympanon (drum) in her left hand.

From Nicaea, Bithynia (Iznik, Turkey).

Roman Imperial period, 2nd century AD,

copy of a Hellenistic original.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 787 T. Cat. Mendel 311. |

| |

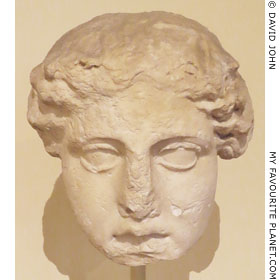

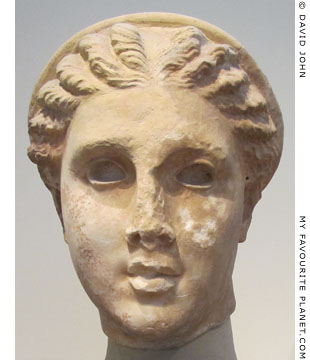

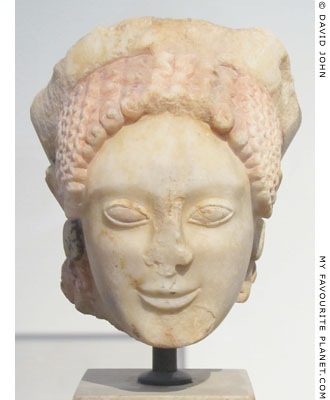

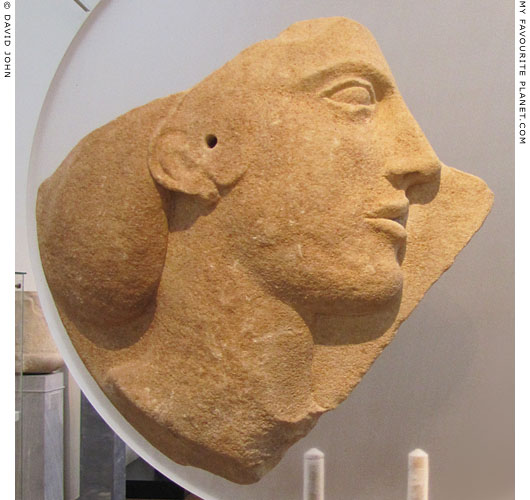

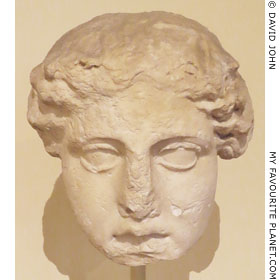

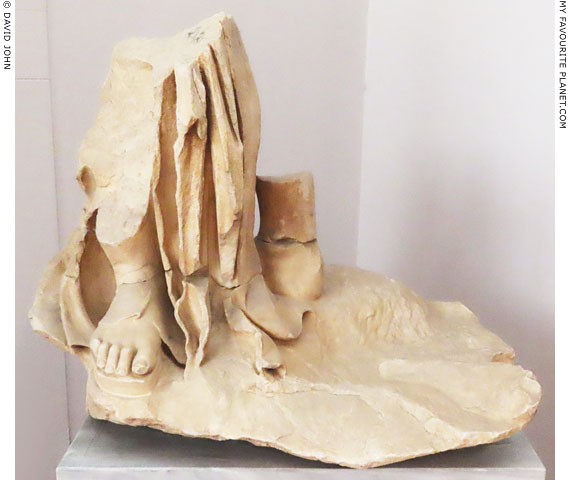

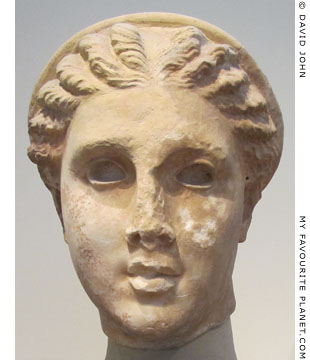

A fragment of a larger than lifesize

marble head of a goddess, probably

from a cult statue. Perhaps unfinished

or reworked. It has been associated

on stylistic grounds with Agorakritos.

Around 420 BC. Unknown provenance.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4491. |

| |

| |

The Sanctuary of Themis and Nemesis, goddesses of Righteousness

and Retribution, within the archaeological site of Rhamnous, north of

Marathon, on the northeast coast of Attica. Viewed from the west.

On the left the surviving platform of the temple of Nemesis, built

around 440-420 BC, and immediately to the right (south) the much

smaller temple of Themis, built around 500-480 BC. |

| |

Rhamnous (Ῥαμνοῦς, buckthorn), over 50 kilometres north of Athens, was an ancient Attic deme, the traditional home of the Aiantis tribe, and the location of a strategically important fortress and harbour on the straits between east Attica and island of Euboea (Εὔβοια). The archaeological site contains the fortified settlement in the valley of Limikon, including a small theatre, gymnasium, temple of Dionysus and a healing sanctuary of Amphiaraos (originally dedicated to the local hero physician Aristomachos), as well as much of its surrounding area, perched high above a long stretch of rocky beaches (linked by a rough coastal path).

Today, the long walk northwards along the old road, now a rough, rocky track, quite steep in places, down from the site entrance to the remains of the fortress affords spectacular views of the settlement, coastal countryside, sea and the mountains of southern Euboea beyond.

The Sanctuary of Themis and Nemesis lay outside the main settlement, on an artificial terrace, partly supported by massive masonry walls, on the brow of a hill above the valley, almost a kilometre south of the main walls of the fortress.

The small Archaic Doric temple dedicated to Themis (Θέμις), built around 500-480 BC, with walls of polygonal limestone blocks and a front porch (pronaos) supported by two columns and the side walls (distyle in antis). Two marble thrones placed in the porch (see below) are taken as evidence that both Themis and Nemesis were worshipped here. Numerous dedications were found in the temple's cella, including a marble statue of Themis, which according to the inscribed base was made by Chairestratos of Rhamnous (see below), although this was made in the late 4th century BC. The temple was used as the treasury of the sanctuary.

Less than half a metre to the north, the much larger, Doric peripteral temple of Nemesis was added to the sanctuary around 440-420 BC. It had 6 columns along its front and back, and 12 along each of its long sides, and its access was oriented a few degrees to the south of that of the older temple. Construction was delayed due to the Peloponnesian War, and eventually many finishing processes, such as the fluting of the columns, were left uncompleted. The cult statue inside the temple is usually attributed to Agorakritos of Paros (see above).

Christians are said to have destroyed the sanctuary in the late 4th century AD.

The first archaeological excavations at Rhamnous were undertaken by the members of the Society of Dilettanti in 1813, and continued in the late 19th century by Dimitrios Filios (1880) and Valerios Stais (1890-1893) of the Archaeological Society of Athens. Following intermittent digs, systematic archaeological investigation of the site was resumed from 1975 by Vasileios Petrakos. |

|

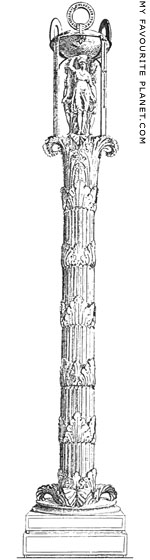

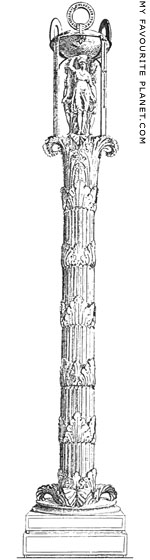

A marble herm of a youth from

Rhamnous. The figure of a youth,

wearing a chiton and a chlamys,

depicted in the round as far as

his knees, stood on a pillar on

an inscribed cylindrical base. The

inscription is a dedication following

a victory in a torch race.

Around 330-320 BC. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 313. |

|

| |

Two marble thrones in the pronaos (front porch), flanking the doorway

to the cella of the Archaic temple of Themis at Rhamnous. |

| |

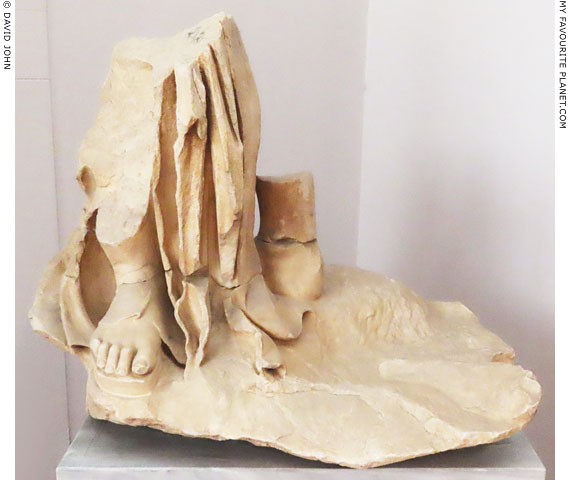

A fragment of a marble statue group from Rhamnous. Two feet and the bottom

of a woman's garment, from a group of two figures depicting the abduction of

the Nymph Oreithyia by Boreas, which was part of the central akroterion

of the temple of Nemesis at Rhamnous. Attributed to Agorakritos of Paros.

Around 430-420 BC. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 2348. |

| |

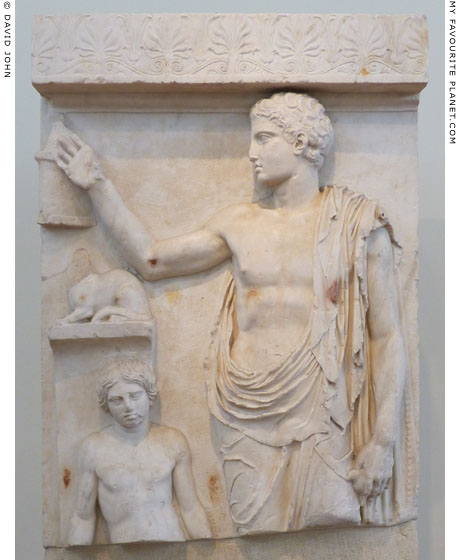

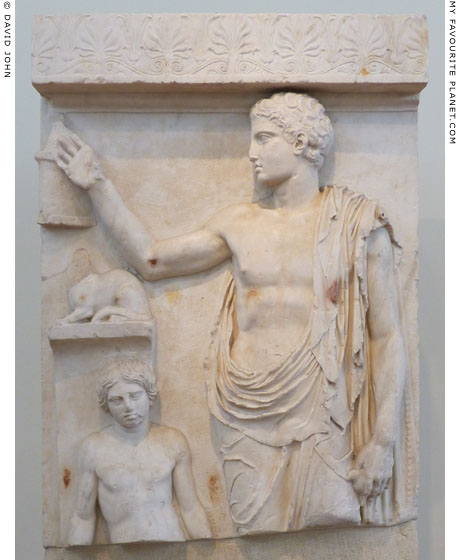

The so-called "Cat Stele", the top of a marble grave stele found

on Salamis or Aegina, with a relief possibly made by a sculptor

who trained in the workshop of Agorakritos of Paros and may

have also worked on the Parthenon frieze.

Around 430-420 BC. Pentelic marble. Height 104 cm.

A standing youth, his head turned to the left, holds a bird in his lowered left hand

and extends his right hand to an empty cage. On the left stands a sad-looking

young attendant (a slave?), depicted at a smaller scale, leaning against a pillar

on top of which is a crouching cat (or sphinx), now headless. If it is a cat, it is

one of the few depicted in Greek art. The horizontal moulding at the top of the

stele is decorated with a relief band of palmettes and lotus flowers.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 715.

Following its discovery the stele was taken to the Aegina museum, newly-independent

Greece's first national archaeological museum, established by Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias

in 1829. The work was first recorded and published by the French architect Guillaume Abel

Blouet (1795-1853), head of the architecture and sculpture team of the Institut de France's

Morea Expedition 1829-1833 (see Herodes Atticus). |

| |

A marble relief of enthroned Kybele in a naiskos (ναΐσκος, small temple).

One of several dozen examples found in the Athenian Agora. Perhaps

a copy of the cult statue by Agorakritos or Pheidias which stood in

the Metroon (Μητρῷον), built in the Agora in the 5th century BC.

Late 4th century BC. Found in the Athenian Agora, 16 May 1937.

Pentelic marble. Height 31 cm, width 23.4 cm, depth 10.3 cm.

The goddess wears a polos and a high-girdled long chiton (tunic). In

other similar reliefs she is shown with a large tympanon (drum) in her

left hand (here missing). Her right forearm is on an amrest of the throne,

and in her right hand she holds a phiale (libation bowl). A lion, shown

at a much smaller scale, lies on her lap, facing left. Her feet are on a

footrest, which is flanked by a small male and female figure.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 922. |

| |

A Marble relief of enthroned Kybele in a naiskos, built into the

east gable of the Byzantine Little Metropolis church in central Athens.

The small Byzantine church of Panagia Gorgoepikoos (Παναγία Γοργοϋπήκοος, the

swift-hearing Virgin), also known as the Little Metropolis (Μικρή Μητρόπολη, Mikri

Mitropoli), and for a short while renamed as the church of Agios Eleutherios (Άγιος

Ελευθέριος), acted as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens during the Turkish

occupation, until the much larger modern cathedral was built next to it 1842-1862.

It is not known when the church was built, perhaps as early as the 9th century or

as late as the 15th century. It was constructed using marble spolia, material from

various older pagan and Christian buildings, so that its walls are covered with a

variety of reliefs and inscriptions from different periods. Ancient inscriptions were

also housed inside the church, as well as a Roman period sundial, which is now in

the British Museum (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 36). Attempts have been

made to identify the parts of ancient reliefs built into the walls of the church.

For further information see Demeter and Persephone part 1. |

| |

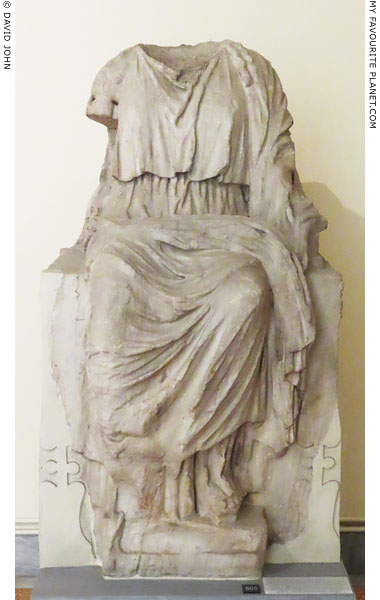

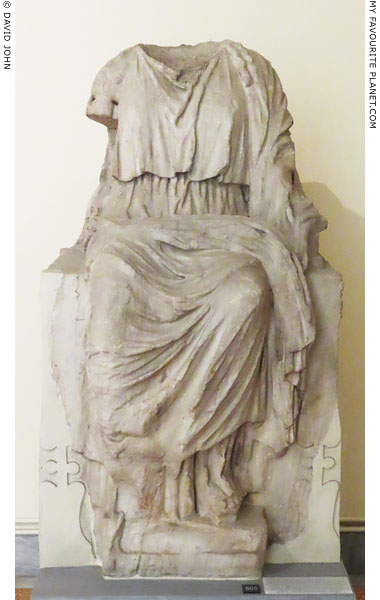

A marble statue of an enthroned goddess, believed to be a

Roman period copy of the cult statue of the Mother of the

Gods by Agorakritos or Pheidias which stood in the Metroon

(Μητρῷον), built in the Athenian Agora around 440 BC.

Found at the junction of Aiolou and Sophokleous streets, Athens.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3265. |

| |

Alexandros of Antioch

Ἀλέξανδρος

or Agesandros of Antioch (Άγήσανδρος)

From Antiochia on the Maeander (Ἀντιόχεια τοῦ Μαιάνδρου), Caria, western Anatolia (today Yenişer, near Başaran, Aydın Province, Turkey).

2nd half of the 2nd century BC

The "Venus de Milo" (Greek, Αφροδίτη της Μήλου, Aphroditi tis Milou, Aphrodite of Milos), now in the Louvre, has become the most famous statue of Aphrodite and one of the best known classical sculptures. Dated to around 130-100 BC, it is thought to depict Aphrodite as Victorious (Latin, Venus Victrix). It was discovered by a Greek farmer on 8th April 1820 on Melos, Greece, when the Cycladic island was still part of the Ottoman Empire. Some scholars have argued that it depicts the sea goddess Amphitrite (consort of Poseidon), who was worshipped on Milos.

The statue was found in two pieces: the head and naked upper torso, and the draped legs attached to part of the base. Also found at the same location were other fragments, including part of the draped right hip, an upper left arm (Inv. No. Ma 401) and a left hand holding an apple (Inv. No. Ma 400), the right side of the base, which was inscribed, as well as two small herms (Inv. Nos. Ma 404 and Ma 405; a third herm, Inv. No. Ma 403, was found later than the other objects). One of the herms depicts Herakles and the other two Hermes.

The inscribed right side of the base (see image below) was examined by scholars when all the fragments were delivered to the Louvre, and it was found to fit exactly to the base fragment below the lower part of the statue. The inscription was an artist's signature:

-----ΑΝΔΡΟΣ -ΗΝΙΔΟΥ

-----ΟΧΕΥΣ ΑΠΟ ΜΑΙΑΝΔΡΟΥ

ΈΠΟΙΗΣΕΝ

The incomplete inscription has been restored as:

Alexandros, son of Menides,

citizen of Antioch of Meander

made it

It has been argued that the name may have been Agesandros (see image below). A number of scholars believed that the statue had been made by Praxiteles, and it was presented to King Louis XVIII as such. (Later it was also suggested the at the statue was by Skopas.) Thus it was assumed that this artist may only have been responsible for a later restoration. Unfortunately - and controversially - the inscribed base fragment disappeared soon after it entered the Louvre.

"Venus de Milo", Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 399 (LL 299). Parian marble. Height 202 cm. A gift of the Marquis de Rivière, the French ambassador to Ottoman Turkey, to Louis XVIII of France, 1821.

At the time when the fragments were reassembled in the Louvre, the upper left arm and hand were considered to be of inferior workmanship and have not been restored to the statue. The restorers probably considered the statue looked better armless, and in this form it has become an "iconic" representative of classical art. The apple (μῆλον) in the hand is thought to be the Golden Apple won by Aphrodite in the Judgement of Paris. It may also have been a punning reference to the island of Melos (Μηλος).

See:

Gregory Curtis, Base Deception, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2003.

Rachel Kousser, Creating the past: The Vénus de Milo and the Hellenistic reception of Classical Greece. In: American Journal of Archaeology 109 (2005), pages 227-250.

Two inscriptions, dated around 150-100 BC, from Thespiai (Θεσπιαί) in Boeotia, central Greece, where poetry and theatre competitions were held, mention an Alexandros of Antioch, son of Menides, as victor in singing and composing. It has been suggested that this may be the same person.

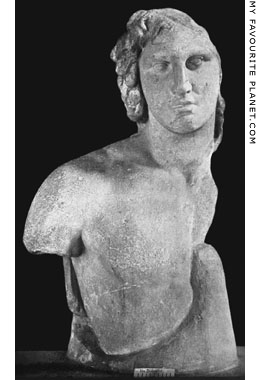

The same sculptor may also have made the "Inopos", a fragment of the upper part of a marble statue found on Delos, and now also in the Louvre (see photo, right). The fragment, which includes the head and right side of the chest, is in the style of portraits of Alexander the Great. It was initially thought to depict the Delian river god Inopos (Ινωπος), but is now considered to be a Hellenistic ruler, either Alexander himself or Mithradates VI, king of Pontus (circa 120-63 BC).

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 855 (MR 235). Circa 100 BC. Height 95 cm. Donated by the painter E. A. Gibelin, 1801.

See: Bust of Alexander the Great, known as the "Inopos", at the Louvre website. |

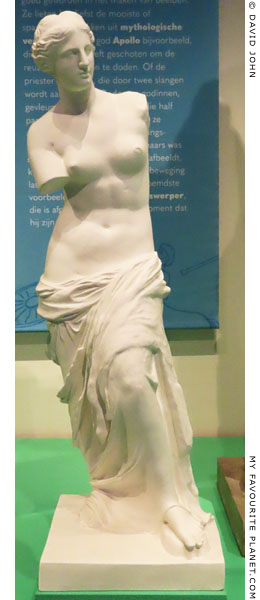

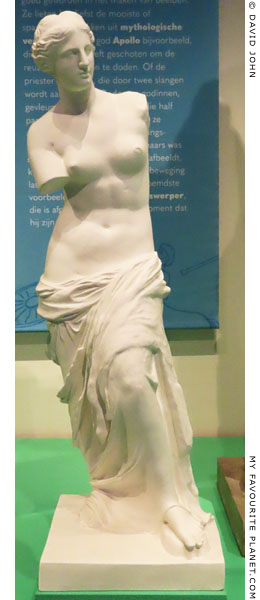

A reduced plaster copy of the

"Venus de Milo" statue, with

the left foot restored.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden,

Leiden, Netherlands. |

| |

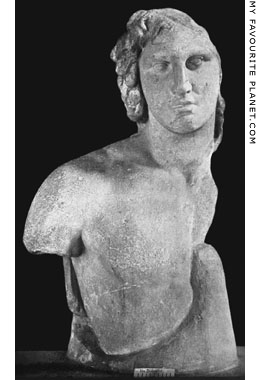

The "Inopos", a fragment of a

statue in the style of portraits

of Alexander the Great.

Around 100 BC. From Delos.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 855.

Source:

Guy Dickens, Hellenistic sculpture,

Fig. 20, page 26. Clarendon Press,

Oxford, 1920. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

| |

The lower part of the "Venus de Milo", part of a drawing made

by Auguste Debay at the request of Jacques-Louis David.

|

The drawing shows the now missing inscribed base fragment, which was attached to the statue soon after the arrival of all the sculpture fragments in the Louvre. The entire drawing was used as a frontispiece for the pamphlet Sur la statue antique de Vénus Victrix written in 1821 by the Comte de Clarac, Conservateur du Musee Royal des Antiques, in which he was the first to publish the claim that the statue was made by Alexandros of Antioch, much to the displeasure of his colleagues.

The rectangular dowel hole in the top of the base is thought to have been a socket for a herm or pillar. The findspot of the statue has been identified as an exedra (niche) of the city's gymnasium, in which an inscription (also now lost) found above the entrance stated that the assistant gymnasiarch Bakchios, son of Satios (Βάκχιος Σατίου) had dedicated "this exedra and this [statue] to Hermes and Hercules" (inscription IG XII.3.1091). Both gods were associated with gymnasia and baths as patrons, and statues and herms were set up in such buildings.

It is possible that one of the herms discovered with the statue stood alongside Aphrodite. "Piedestal d'un des hermes", a drawing made by the French naval officer Olivier Voutier on Melos at the time of its discovery (published in F. Ravaisson, La Vénus de Milo, Paris, 1892), shows that the herm of Herakles stood next to Aphrodite on the same base. The goddess' left arm may have originally rested on the herm so that it acted as a support for the statue. This was refuted by 19th century art historians, including Adolf Michaelis, who considered the herm to be "of mediocre work", "tasteless" and greatly inferior in quality to the "illuminating beauty" of the "majestic woman of Melos". Michaelis was among those who attributed both statue and herm to Alexandros, although he believed the Venus to be a copy of an earlier work:

"No serious doubt can be entertained that the statue is the work of Alexandros. To him is due the addition of the tasteless herm (a restored copy by the French sculptor Claude Tarral makes this evident), and of the apple (Greek μῆλον), an emblem of the island of Melos; on the other hand we are indebted to him for the excellent reproduction of the body and head of a superb original, probably of the time of Scopas."

Adolf Michaelis, A century of archaeological discoveries, page 51. John Murray, London, 1908. At the Internet Archive.

Image source: Adolf Furtwängler, Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik (part 1, text), Fig. 117,

page 607. Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig / Berlin, 1893. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

English version: Furtwängler, Adolf, Masterpieces of Greek sculpture, edited by Eugénie Sellers

(Strong), Fig. 159, page 371. William Heinemann, London, 1895. At the Internet Archive.

Furtwängler dedicated an entire chapter to the Venus de Milo (pages 367-401 in the English edition), and discussed the block with the inscribed signature at length. He seemed convinced that it belonged with the statue:

"The disappearance of the inscription, in my opinion, is only a proof of its genuineness. It was an awkward witness, and had to be quietly got out of the way." page 369

He also commented on the disappearance of the gymnasiarch's inscription:

"The block with the dedicatory inscription has likewise disappeared (another inconvenient witness hushed up!)." page 377

Strangely, he did not quote or discuss the signature inscription itself or the possible identity of the artist, whose name is not mentioned. |

|

|

| |

A reconstruction drawing of the "Venus de Milo" base, hypothetically

restoring the missing left foot of the statue and top left corner of the inscription.

The name of the artist has been restored as ΑΓΕΣΑΝΔΡΟΣ (Agesandros).

Source: Adolf Furtwängler, Meisterwerke der griechischen Plastik (part 1, text), Fig. 118,

page 608. Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig / Berlin, 1893. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

English version: Furtwängler, Adolf, Masterpieces of Greek sculpture, edited by Eugénie Sellers

(Strong), Fig. 160, page 372. William Heinemann, London, 1895. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Alkamenes

Αλκαμένης (Latin, Alcamenes)

Worked in Athens, 2nd half of the 5th century BC

For further details see the Alkamenes page. |

|

|

| |

Alxenor

Ἀλξήνωρ (signature, Ἀλχσήνορ)

From Naxos, early 5th century BC

A grave stele of grey Boeotian marble, dated to around 490 BC, and found in Orchomenos, Boeotia, is signed at the bottom by Alxenor (see photo below). The low relief on the front of the stele is described as typical work of a Naxian workshop. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 39. |

|

|

| |

A marble grave stele from Orchomenos, Boeotia,

signed at the bottom by Alxenor in the Naxian alphabet:

Ἀλχσήνορ [ἐ]ποίησεν ό Νάχσιος ἀλλ’ ἐσίδεσ̣[θε]

"Alxenor of Naxos made this; just look!"

Inscription IG VII 3225 (also CEG 150)

at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Around 490 BC. Grey Boeotian marble.

Height 197 cm, width 61 - 59 cm, depth 18 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 39. |

| |

A drawing of the signature of Alxenor inscribed at the bottom of the grave stele.

Source: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors),

No. 7, pages 10-11. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

|

Most of the surface of the front of the stele is filled with a low relief depicting the full-length figure of an elderly bearded man, wearing a himation (cloak) and supporting himself on a walking stick or crutch. Between the forefinger and thumb of his right hand he holds a grasshopper (or cricket or locust) which he offers to his dog. He is thought to be the deceased honoured by the funerary monument, and the base of the stele (now missing) was probably inscribed with his name (as on the grave stele of Aristion by Aristokles).

The height of the stele given by different sources varies between 197 cm and 205 cm.

The stele was first reported by the Irish painter and traveller Edward Dodwell (1767-1832), who saw it in December 1801 in the churchyard of the village of Romaiko (Ρωμαίικο), on the river Kifissos, 4 km west of the site of ancient Orchomenos (Ὀρχομενός) and 2 km southwest of its acropolis. Dodwell was unable to decipher the Naxian script. He speculatively associated the insect held by the man on the stele with a historical or legendary plague of locusts.

"As the basis of the monument was under ground, I removed the earth, and discovered on it a few letters; which, from their imperfect state, it has been impossible to render intelligible."

"In the Athenian Acropolis there was anciently a statue of Apollo, named Parnopios, because he delivered the country from locusts [a bronze statue near the Parthenon, said to be by Pheidias, Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 24, section 8]. Strabo [Geography, Book 13, chapter 1, section 64] says that the Oitaians honoured Hercules under the name of Kornopion, because he delivered them from locusts, which the Greeks generally called parnopes though the Oitaians called them kornopes. The monument of Romaiko may allude to this circumstance."

Edward Dodwell, A classical and topographical tour through Greece, during the years 1801, 1805, and 1806, Volume 1 (of 2), pages 242-243, with drawing. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819. At the Internet Archive. |

|

A drawing of the Alxenor stele

by Edward Dodwell. |

|

| |

Anaxagoras of Aegina

Ἀναξαγόρας

From Aegina, early 5th century BC

According to Pausanias, Anaxagoras made a bronze statue of Zeus at Olympia, commissioned by the Greek states which had united against the invasion of Xerxes I of Persia (480-479 BC), and fought at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC against Xerxes' general Mardonius.

"As you pass by the entrance to the Council Chamber you see an image of Zeus standing with no inscription on it, and then on turning to the north another image of Zeus. This is turned towards the rising sun, and was dedicated by those Greeks who at Plataea fought against the Persians under Mardonius. On the right of the pedestal are inscribed the cities which took part in the engagement ..."

After listing the various cities, Pausanias continued:

"The image at Olympia dedicated by the Greeks was made by Anaxagoras of Aegina. The name of this artist is omitted by the historians of Plataea."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 23, sections 1-3. |

|

|

|

| |

Antenor

Ἀντήνωρ

Working in Athens around 540-500 BC

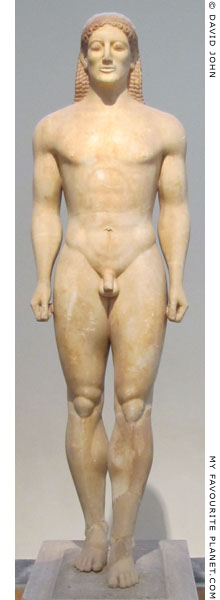

Antenor made bronze statues of the Athenian "Tyrannicides" (Τυραννοκτόνοι) Harmodius and Aristogeiton (Ἁρμόδιος καὶ Ἀριστογείτων), two aristocrats who in 514 BC killed Hipparchos, brother of the Athenian tyrant Hippias, son and successor of the tyrant Peisistratos, and were then themselves killed.

The statue group, which stood in the Athenian Agora, was commissioned by the Athenians after Hippias had been driven out of the city with the help of the Spartans in 511/510 BC and the establishment of democracy. They were the first Greek statues known to depict real persons heroized by a recent historical event. Pliny the Elder thought that they may have been the first public statues of individual mortals. However, it is not known whether many earlier surviving Greek sculptures (particularly kouros and kore statues, see photos below) were meant to represent deities, mythological characters, generic figures or real individuals (for example the "Kleobis and Biton" statues).

"It was not the custom in former times to give the likeness of individuals, except of such as deserved to be held in lasting remembrance on account of some illustrious deed; in the first instance, for a victory at the sacred games, and more particularly the Olympic Games, where it was the usage for the victors always to have their statues consecrated. And if any one was so fortunate as to obtain the prize there three times, his statue was made with the exact resemblance of every individual limb; from which circumstance they were called "iconicae" [portrait statues].

I do not know whether the first public statues were not erected by the Athenians, and in honour of Harmodius and Aristogiton, who slew the tyrant; an event which took place in the same year in which the kings were expelled from Rome [510 BC]. This custom, from a most praiseworthy emulation, was afterwards adopted by all other nations; so that statues were erected as ornaments in the public places of municipal towns, and the memory of individuals was thus preserved, their various honours being inscribed on the pedestals, to be read there by posterity, and not on their tombs alone."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 9. At Perseus Digital Library.

Antenor's Tyrannicides were carried away to Persia by Xerxes I with other booty from his occupation of Athens in 480 BC. Around two centuries later they were returned by the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter, but meanwhile two new statues had been made by Kritios and Nesiotes (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 5; also chapter 29, section 15). The Roman period statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton now in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Inv. No. G 103 and G 104, are thought to be copies these later sculptures.

Pliny the Elder wrote that Praxtiles (4th century BC) also made bronze statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, although he incorrectly believed them to be the sculptures taken by Xerxes.

"He [Praxtiles] also executed a Stephanusa, a Spilumene, an Oenophorus, and two figures of Harmodius and Aristogiton, who slew the tyrants; which last, having been taken away from Greece by Xerxes, were restored to the Athenians on the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Later in the same chapter Pliny mentioned that a sculptor named Antignotus also made bronze statues of the Tyrannicides.

It has been suggested that the akroterion statue of winged Nike (515-505 BC) from the Archaic temple of Apollo in Delphi may be by Antenor. Delphi Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1872.

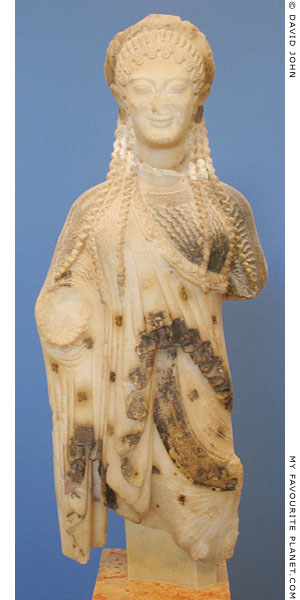

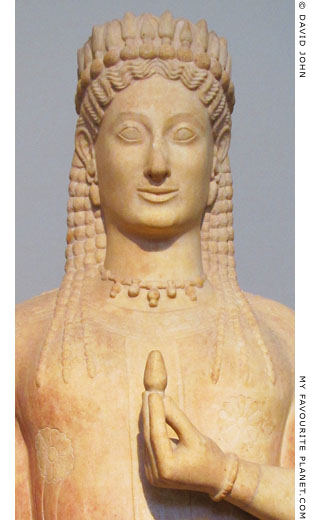

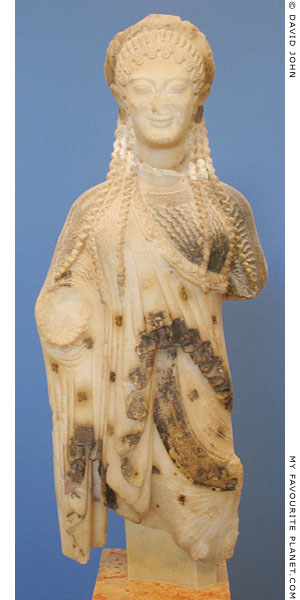

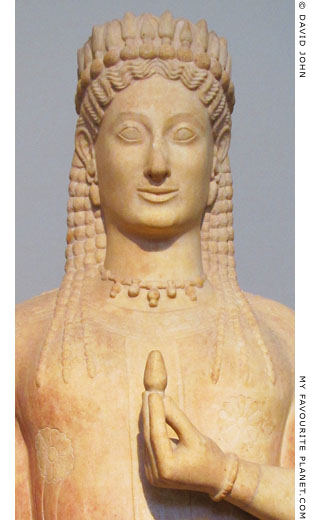

The so-called "Antenor's Kore" (or "Antenor Kore"), the largest of around 200 korai statues found on the Athens Acropolis, is thought to be a work of Antenor from an inscribed statue base on which it is now exhibited. Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 681 (statue and base). Around 530-520 BC. Height of statue 255 cm (including plinth, 4 cm). Inscribed base height 30 cm, width 60.5 cm, depth 60.5 cm.

The feet of the statue and plinth were found in 1882 east of the Parthenon. The upper part and inscribed base were found on 5th and 6th February 1886 northwest of the Erechtheion. The connecting piece between feet and torso was found in 1887.

The fragmentary inscription on the base states that the statue was dedicated by Nearchos (perhaps a potter) and made by Antenor, son of Eumares (see photo below).

Νέαρχος ἀνέθεκεν̣ [ℎο κεραμε]-

ὺς ἔργον ἀπαρχὲν τ̣ἀθ[εναίαι].

Ἀντένορ ἐπ[οίεσεν ℎ]-

ο Εὐμάρος τ[ὸ ἄγαλμα].

Nearkhos [the potter ?] dedicated

this work from the first fruits to Athena.

Antenor, son of Eumares,

made the statue.

Inscription IG I³ 628 (Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 197).

Based on this inscription, it has been speculated that Antenor's father Eumares may have been the painter Eumarus of Athens mentioned by Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 35, chapter 34). Some scholars believe that Nearchos may be the Athenian potter and vase painter of the black figure style, active around 570-555 BC, who is known from surviving works, some of which he signed.

"Antenor's Kore" may have been made 510-500 BC, following the fall of Peisistratids, as part of a revival of the "broad and stocky" Attic type of sculpted figure, and a reaction to the tall, slim, more delicate Ionian statues (see Archemos of Chios) which had been preferred during the tyranny.

See: Guy Dickins, Catalogue of The Acropolis Museum, Volume I Archaic Sculpture, pages 19-24.

Cambridge University Press, 1912. At the Internet Archive. |

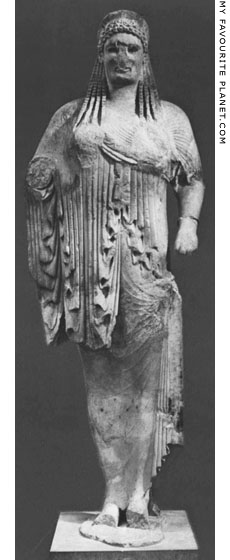

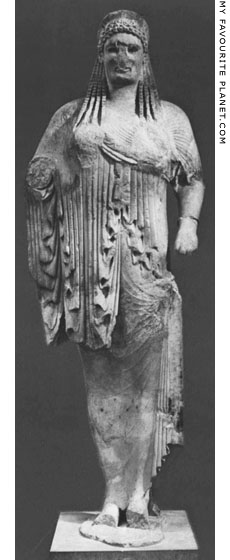

"Antenor's Kore".

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 681. |

| |

A reconstruction drawing of

"Antenor's Kore", showing the

figure holding a phiale in her

right hand, and standing on

the inscribed capital.

Image source:

Alexander Stuart Murray,

A history of Greek sculpture,

Volume 1, Fig. 41, page 158.

John Murray, London, 1890.

At the Internet Archive. |

| |

| |

The statue base from the Athens Acropolis, dedicated by Nearkhos and signed by Antenor.

Source: Edmund von Mach, A handbook of Greek and Roman sculpture, Fig. 3.

Bureau of University Travel, Boston, 1914. |

| |

Antiphanes of Argos

Ἀντιφάνης ὁ Ἀργεῖος

From Argos, northeastern Peloponnese, late 5th century BC

He was a pupil of Periklytos, and teacher of Kleon.

Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 10) mentioned several statues by Antiphanes at Delphi:

Elatos, Apheidas, Erasos, the Dioskouri and a bronze horse, "supposed to be the wooden horse of Troy". |

|

|

| |

Antonianos of Aphrodisias

Αντωνιανος ΑΦροδεισεις

Mid 2nd century AD

From Aphrodisias (Ἀφροδισιάς), Caria, western Anatolia (today near the modern village of Geyre, Aydın Province, Turkey).

See also Aristeas and Papias of Aphrodisias below.

Known from his signature inscribed on a marble relief depicting Antinous as Silvanus, 130-138 AD. Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 374071.

ANTωNIANOC AΦPOΔEICIEYC EΠOIEI

Antonianos of Aphrodisias made this.

Inscription SEG 43, 904.

See photos and details on the Antinous page. |

|

|

| |

Apelleas son of Kallikles

Ἀπελλέας Καλλικλέος, also Apelles (Ἀπελλῆς) or Apellas (Ἀπελλᾶς)

Late 5th - early 4th century BC

Son of Kallikles (Καλλικλῆς), who may have been the sculptor Kallikles, son of Theokosmos, from Megara (Μέγαρα), central Greece.

Part of an inscribed circular stone statue base found by German archaeologists in Olympia in 1879, with a dedicatory epigram for Kyniska and the signature of Apelleas son of Kallikles (see photo below) is thought to belong to a bronze statue group mentioned by Pausanias, although he referred to the artist as Apelles. He wrote that Kyniska (Κυνίσκα, born circa 440 BC), daughter of the Spartan king Archidamos II (Ἀρχίδαμος Β΄, ruled circa 476-427 BC), was the first woman to win Olympic victories.

"Archidamus left sons when he died, of whom Agis was the elder and inherited the throne instead of Agesilaus. Archidamus had also a daughter, whose name was Cynisca; she was exceedingly ambitious to succeed at the Olympic games, and was the first woman to breed horses and the first to win an Olympic victory. After Cynisca other women, especially women of Lacedaemon, have won Olympic victories, but none of them was more distinguished for their victories than she.

The Spartans seem to me to be of all men the least moved by poetry and the praise of poets. For with the exception of the epigram upon Cynisca, of uncertain authorship, and the still earlier one upon Pausanias that Simonides wrote on the tripod dedicated at Delphi, there is no poetic composition to commemorate the doings of the royal houses of the Lacedaemonians."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 8, sections 1 and 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

The epigram is preserved in the Palatine Anthology (Anthologia Palatina, Book XIII, Epigram 16), and was used to help reconstruct the inscription on the statue base.

Kyniska's brother Agesilaos was later to become King Agesilaos II of Sparta (Ἀγησίλαος Β΄, ruled circa 398-360 BC), and her victories may have been during his reign, perhaps in the 96th and 97th Olympics (396 and 392 BC). In his short biography of the king, Xenophon of Athens (Ξενοφῶν, circa 430-354 BC), claimed it was Agesilaos who encouraged his sister to breed chariot horses:

"And what a fine trait this was in him [Agesilaos], and betokening how lofty a sentiment, that, being content to adorn his own house with works and possessions suited to a man, and being devoted to the breeding of dogs and horses in large numbers for the chase and warfare, he persuaded his sister Cynisca to rear chariot horses, and thus by her victory showed that to keep a stud of that sort, however much it might be a mark of wealth, was hardly a proof of manly virtue."

Xenophon, Agesilaus. Translated by Henry Graham Dakyns. The Works of Xenophon, Volume 2, chapter IX. At Wikisource.

Later, Pausanias described the statue group in Olympia and said that it was made by Apelles.

"As for Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus, her ancestry and Olympic victories, I have given an account thereof in my history of the Lacedaemonian kings [Book 3]. By the side of the statue of Troilus at Olympia has been made a basement of stone, whereon are a chariot and horses, a charioteer, and a statue of Cynisca herself, made by Apelles; there are also inscriptions [ἐπιγράμματα, epigrams] relating to Cynisca."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 1, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Only around a third of the circular base has been found. Its original diameter is estimated to have been around 1 metre, and far too small for a statue of a chariot. On its top, along with the inscription, is the trace of a footprint. It is thus thought that this may have been the base of the statue of Kyniska herself.

Earlier in his guided walk around the Altis, the Sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia, he had noted reduced-sized bronze horses, a replica of Kyniska's victory monument, in the pronaos (front porch) of the Temple of Zeus:

"The offerings inside, or in the fore-temple include: a throne of Arimnestus, king of Etruria, who was the first foreigner to present an offering to the Olympic Zeus, and bronze horses of Cynisca, tokens of an Olympic victory. These are not as large as real horses, and stand in the fore-temple on the right as you enter. There is also a tripod, plated with bronze, upon which, before the table was made, were displayed the crowns for the victors."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 12, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias did not write that these horses had beeen made by the same artist. However, on 28 November 1876 part of another inscription with the signature of Apelleas was found on a fragment of a tapering rectangular white marble plinth in the pronaos of the Temple of Zeus. The plinth, dated to the first half of the 4th century BC, and estimated to have originally been 100 cm high, 42 cm wide and 46-47 cm deep, is thought to have been the base for the bronze horses of Kyniska.

[Ἀπε]λλέας Καλλικλέος

[ἐπό]ησε.

[Ape]lleas son of Kallikles

made it

Inscription IvO 634.

IvO = Inschriften von Olympia: Wilhelm Dittenberger and Karl Purgold, Olympia, Textband 5: Die Inschriften von Olympia, Numbers 160 and 634. A. Ascher & Co., Berlin, 1896. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Apelleas may have been the Apellas mentioned by Pliny the Elder as a sculptor in bronze who made statues of worshipping females, among a number of artists who achieved celebrity, "but none of whom have produced any first-rate works".

"Apellas has left us some figures of females in the act of adoration."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

As with many Greek artworks mentioned by Pliny, Kyniska's victory monument may have been taken to Rome. It has been suggested that her statue, like those of other victors in Olympia, showed her as an adorant. In fact, immediately after Pausanias told us that Kyniska's statue was made by Apelles, he mentioned other statues of Lacedaemonians who had won victories in chariot races, including Anaxander (Ἀνάξανδρος), who "is represented in an attitude of prayer to the god [Zeus]." (Book 6, chapter 1, section 7)

Although neither Pliny nor Pausanias tell us about the family or place of origin of Apellas / Apelles, from the fortunate find of the statue base with the dedication to Kyniska and the signature of "Apelleas son of Kallikles", added to the other information provided by Pausanias concerning Theokosmos of Megara and his son Kallikles, it appears that all three were members of the same family of artists. |

|

|

| |

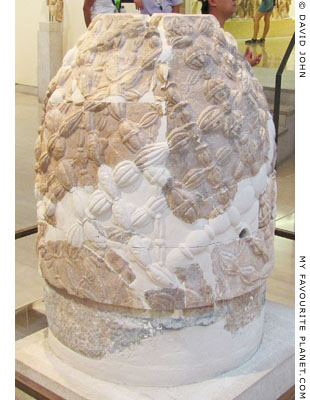

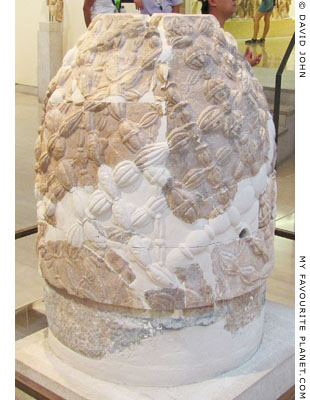

Fragment of an inscribed circular black limestone base for part of a bronze

statue group by Apelleas son of Kallikles to commemorate Olympic race

victories by horses and chariots owned by the Spartan princess Kyniska.

After 390-380 BC. Found on 11 June 1879 in the north part of the Prytaneion,

Olympia. Height 49 cm, thickness 47 cm. Original diameter circa 100 cm.

On top:

Σπάρτας μὲν [βασιλῆες ἐμοὶ]

πατέρες καὶ ἀδελφοί, ἅ[ρματι δ’ ὠκυπόδων ἵππων]

νικῶσα Κυνίσκα εἰκόνα τάνδ’ ἔστασε· μόν[αν]

δ’ ἐμέ φαμι γυναικῶν Ἑλλάδος ἐκ πάσας τό[ν]-

δε λαβε͂ν στέφανον.

On the front side:

Ἀπελλέας Καλλικλέος ἐπόησε.

My fathers and brothers are kings of Sparta.

I, Kyniska, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses,

have set up this statue. I declare myself the only woman

in all Hellas to have ever won this crown.

Apelleas son of Kallikles made it.

Inscription IvO 160.

Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer, No. 99.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 529.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympia. |

| |

Apollonios, son of Archias the Athenian

Απολλωνιος Αρχιου Αθηναιος

Working around the time of the reign of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD)

Apollonios is known only from his signature on the front of a bronze herm with a head of the Doyrphoros type:

Ἀπολλώνιος Ἀρχίου Ἀθηναῖος ἐπόησε.

Apollonios son of Archias the Athenian made me.

Inscription IG XIV 712.

Found in the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 4885. See photo and further details under Polykleitos the Elder. |

|

|

| |

Apollonios and Tauriskos (of Tralles)

Απολλώνιος και Ταυρίσκος (Latin, Apollonius et Tauriscus)

Brothers, probably from Tralles (Τράλλεις), Caria (today Aydın, Turkey), 2nd century BC.

Sons of Artemidorus (Ἀρτεμίδωρος);

pupils and perhaps adoptive sons of Menekrates.

Apollonios and Tauriskos are among the sculptors whose works Pliny the Elder wrote were displayed in the memorial buildings of Asinius Pollio (75 BC - 4 AD) in Rome.

"Asinius Pollio, a man of a warm and ardent temperament, was determined that the buildings which he erected as memorials of himself should be made as attractive as possible; for here we see groups representing, Nymphs carried off by Centaurs, a work of Arcesilas: the Thespiades, by Cleomenes: Oceanus and Jupiter, by Heniochus: the Appiades, by Stephanus: Hermerotes, by Tauriscus, not the chaser in silver, already mentioned, but a native of Tralles: a Jupiter Hospitalis by Papylus, a pupil of Praxiteles: Zethus and Amphion, with Dirce, the Bull, and the halter, all sculptured from a single block of marble, the work of Apollonius and Tauriscus, and brought to Rome from Rhodes. These two artists made it a sort of rivalry as to their parentage, for they declared that, although Artemidorus was their natural progenitor, Menecrates would appear to have been their father."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

It is not clear if the "Tauriscus ... a native of Tralles" who made the Hermerotes is the same person as the brother of Apollonius. Some scholars, believing them to be the same, refer to the brothers as Apollonius and Tauriscus of Tralles.

From what Pliny wrote, their father was Artemidorus (the Perseus translation has "Apollodorus" for the name of the father, but the Latin text and other translations have "Artemidorus"). Menekrates (also referred to as Menekrates of Rhodes) appears to have been their teacher and/or adoptive father.

It is thought that the much-restored marble statue group known as the "Farnese Bull" (Toro Farnese) may be a 3rd century AD copy of the "Zethus and Amphion, with Dirce, the Bull, and the halter" by Apollonius and Tauriscus, probably made in the late 2nd or early 1st century BC. The largest single classical sculpture yet discovered, it was unearthed in August 1545 in the gymnasium of the Baths of Caracalla, Rome, during excavations commissioned by Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese, pope 1534-1549). Height 370 cm. The group depicts the myth of the brothers Zethus and Amphion binding Dirce, queen of Thebes, to an enraged bull to avenge their mother, Antiope. In 1546 it was installed in the Palazzo Farnese, Rome. In 1788 it was taken to Naples with other objects from the Farnese Collection, and is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Inv. No. 6002. |

|

|

| |

Archelaos of Priene

Ἀρχέλαος Πριηνεὐς

Son of Apollonios of Priene, Ionia

3rd or 2nd century BC

The Apotheosis of Homer, a Hellenistic marble relief, also known as "the Relief of Archelaos", signed by Archelaos, son of Apollonios of Priene.

Ἀρχέλαος Ἀπολλωνίου

ἐποίησε Πριηνεύς

Archelaos, son of Apollonios,

made it, of Priene

Inscription IG XIV 1295

The relief, carved on a 117 cm high slab of white Parian marble, is thought to have to have been made in Alexandria, Egypt, 3rd or 2nd century BC. Parian marble. Discovered near Rome in the 17th century, it is now in the British Museum, London. Inv. No. GR 1819.8-12.1. Sculpture 2191. |

|

|

| |

Archermos of Chios

Άρχερμος (Latin, Archermus)

Mid-late 6th century BC

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4) wrote that Archermos belonged to a family of sculptors from Chios: his grandfather Melas of Chios, his father Mikkiades, and his sons, Bupalus and Athenis. He placed Melas even earlier than Dipoenos and Skyllis (early 6th century BC), "the first artists who distinguished themselves in the sculpture of marble", making him one of the earliest known Greek sculptors.

"Before these artists [Dipoenos and Skyllis] were in existence, there had already appeared Melas, a sculptor of the isle of Chios; and, in succession to him, his son Micciades, and his grandson Archermus; whose sons, Bupalus and Athenis, afterwards attained the highest eminence in the art. These last were contemporaries of the poet Hipponax, who, it is well known, lived in the sixtieth Olympiad [540 BC]. Now, if a person only reckons, going upwards from their time to that of their great-grandfather, he will find that the art of sculpture must have necessarily originated about the commencement of the era of the Olympiads."

Concerning Bupalus and Athenis, Pliny continued:

"Hipponax being a man notorious for his ugliness, the two artists, by way of joke, exhibited a statue of him for the ridicule of the public. Indignant at this, the poet emptied upon them all the bitterness of his verses; to such an extent indeed, that, as some believe, they were driven to hang themselves in despair.

This, however, is not the fact; for, at a later period, these artists executed a number of statues in the neighbouring islands; at Delos for example, with an inscription subjoined to the effect, that Chios was rendered famous not only by its vines but by the works of the sons of Archermus as well.

The people of Lasos still show a Diana [Artemis] that was made by them; and we find mention also made of a Diana at Chios, the work of their hands: it is erected on an elevated spot, and the features appear stern to a person as he enters, and joyous as he departs.

At Rome, there are some statues by these artists on the summit of the Temple of the Palatine Apollo, and, indeed, in most of the buildings that were erected by the late Emperor Augustus. At Delos and in the Isle of Lesbos there were formerly some sculptures by their father to be seen."

Pliny, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4.

At Perseus Digital Library.

Bupalos (Βούπαλος) made the cult statue of Tyche (Τύχη; Latin, Fortuna) for the city of Smyrna, on the Ionian coast of Anatolia, near Chios.

"Bupalos a skilful temple-architect and carver of images, who made the statue of Fortune [Tyche] at Smyrna, was the first whom we know to have represented her with the heavenly sphere [the headdress] upon her head and carrying in one hand the horn of Amaltheia [the cornucopia], as the Greeks call it, representing her functions to this extent. The poems of Pindar later contained references to Fortune, and it is he who called her Supporter of the City."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 4, chapter 30, section 6.

Bupalos also made a group of the Graces (Χάριτες, Charites) in gold for Smyrna, as well as another group of the Graces which in Pausanias' time stood in Pergamon.