|

| |

| 101-103 |

|

Herodes Atticus born at Marathon |

|

| |

| 122-125 |

|

Agoranomos of Athens (overseer of the market) |

|

| |

| 126/127 |

|

Archon of Athens |

|

| |

| 133 |

|

Praetor in Rome |

|

| |

| 134/135 |

|

Corrector of the Province of Asia under Proconsul Antoninus Pius (later emperor);

Dedication in Alexandria Troas |

|

| |

| 139/140 |

|

Agnothetes (manager) of the Panathenaic Games in Athens;

Start of construction of the Panathenaic Stadium |

|

| |

| 140-142 |

|

In Rome: Teacher of rhetoric to Marcus Aurelius;

Marries Annia Regilla;

Trial of the Athenians against Herodes in Rome concerning his father's will |

|

| |

| 143 |

|

Consul Ordinarius;

Birth and death of Claudius, his first child;

Birth of Elpinike, his second child |

|

| |

| 143-144 |

|

Building of the exedra in Delphi with statues of his family members |

|

| |

| 145-146 |

|

Teacher of rhetoric to Lucius Verus, adoptive brother and co-regent with Marcus Aurelius;

Birth of Athenais, his third child;

Birth of Regillus, his fourth child |

|

| |

| 152-153 |

|

Birth of Atticus Bradua, his fifth child (died after 209 AD) |

|

| |

| 153-161 |

|

Completion and dedication of the Nymphaeum in Olympia;

Professor of rhetoric in Athens;

Death of Regillus;

Death of Athenais;

Death of Annia Regilla and their sixth child;

Building of the Odeion in Athens;

Trial in Rome for the murder of Regilla;

Building of the Triopion in Rome |

|

| |

| 165 |

|

Death of Elpinike, leaving Atticus Bradua as Herodes' last surviving child;

Suicide of the Cynic philosopher Peregrinos Proteus near Olympia (see below) |

|

| |

| 167 |

|

Work on the stadium at Delphi |

|

| |

| 170-174 |

|

Quintilii brothers (Sextus Quintilius Condianus and Sextus Quintilius Valerius Maximus) governors in Greece (correctores Achaeae);

Emperor Marcus Aurelius reconstructs the Telesterion (temple of Demeter and Persephone) at Eleusis |

|

| |

| 174-175 |

|

Trial of the Athenians against Herodes at Sirmium, Pannonia before Marcus Aurelius;

Death of Polydeukes;

Return to Athens following a stay at Orikon, Epirus, due to exile or illness (see below) |

|

| |

| 176 |

|

Herodes may have been mystagogue to Marcus Aurelius, preparing him for initiation into the Mysteries at Eleusis (Philostratus, section 563, page 175 [see note 3]) |

|

| |

| 177-179 |

|

Death of Herodes at Marathon. Despite his wish to be buried there, Athenians take his body for burial at the Panathenaic Stadium. |

|

|

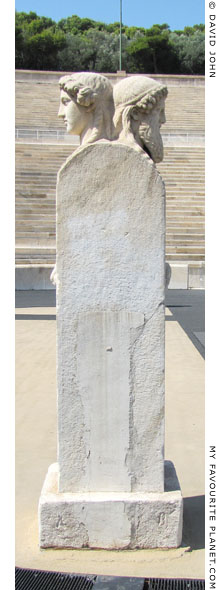

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

Aspasia Annia Regilla |

|

|

|

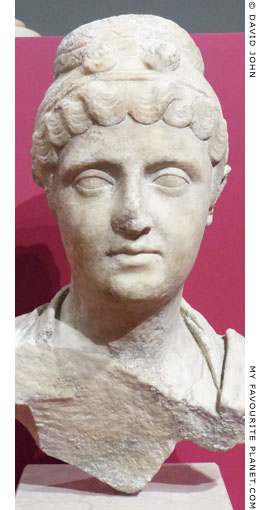

Appia (or Aspasia) Annia Regilla Atilia Caucidia Tertulla (circa 125 - 158/160 AD; known in Greek as Ἀππία or Ἀσπασία Ἄννια Ῥήγιλλα, Aspasia Annia Regilla), Herodes Atticus' wife, was a member of an influential Roman aristocratic family and distantly related to the imperial line. She was married to Atticus around 140 AD, when she was about 14 and he was about 40. Of the six children they are known to have had, only three survived into adulthood (see below).

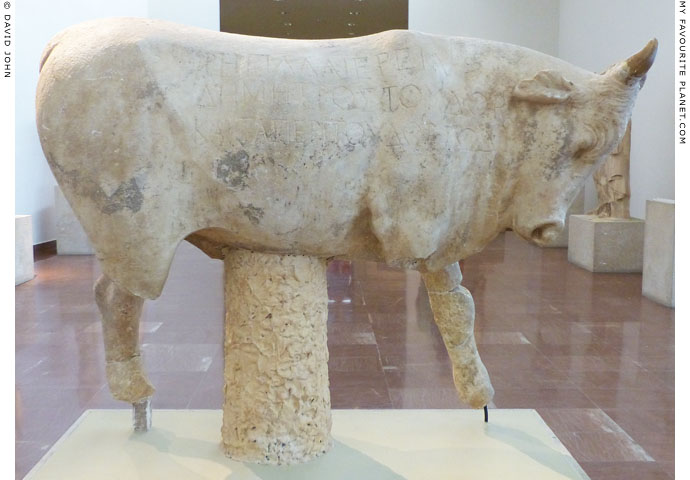

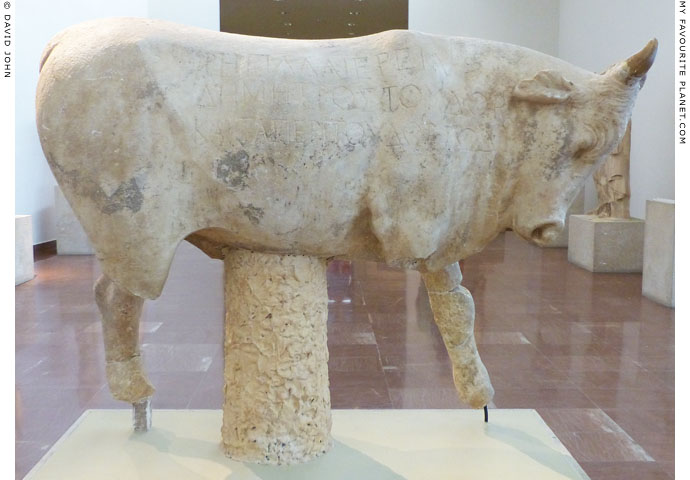

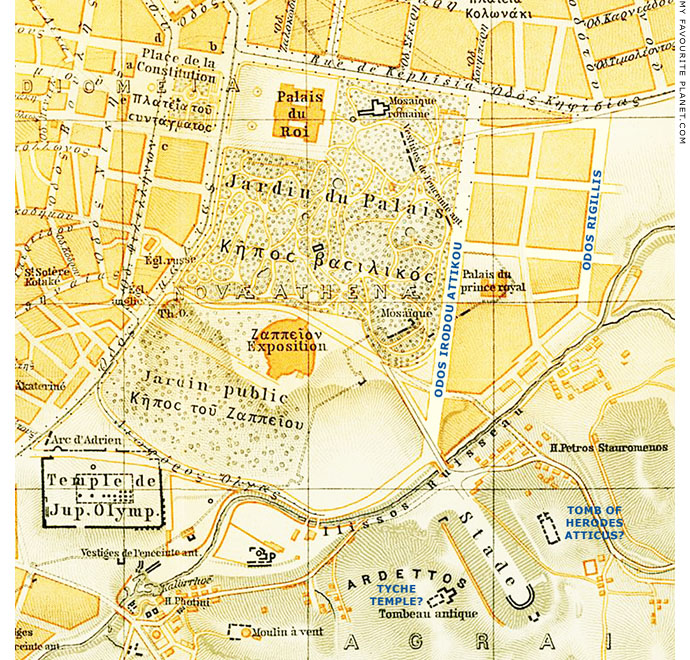

She was the priestess of Demeter at Olympia, the only woman allowed to attend the Olympic Games (see below), and built the Nymphaeum, a monumental fountain, also known as the Fountain or Exedra of Herodes Atticus, decorated with statues of Zeus, members of her and Atticus' families and the imperial family. The fountain also featured a marble statue of a bull, now in the Olympia Museum (see photo below), on the side of which a Greek inscription proclaims: "Regilla, priestess of Demeter, dedicated the water and the fixtures to Zeus."

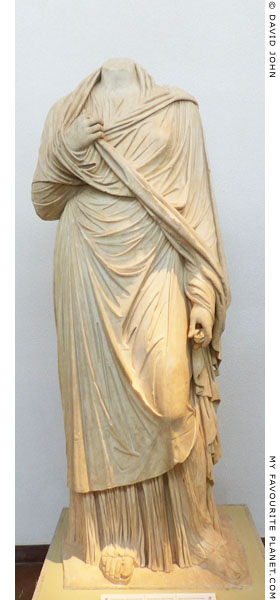

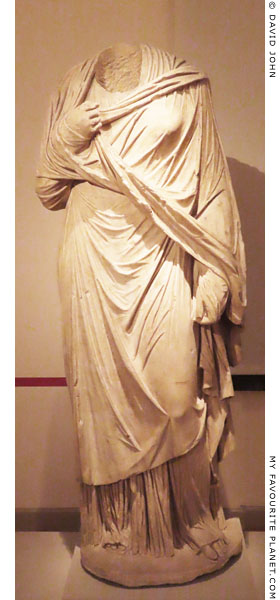

Among her other distinctions, Annia Regilla was also the first priestess of Tyche (Τύχη; Latin, Fortuna) in Athens, probably at the temple of Tyche built by Atticus near the Panathenaic Stadium (see below). A statue of her stood in front of the sanctuary of Tyche in Corinth (see photo, right), and another was dedicated by the traders of Piraeus at the request of the Areopagus. No surviving sculpture head or bust can be definitely identified as a portrait of Regilla, although a now headless statue from the Nymphaeum in Olympia is thought to have depicted her (see photo below).

During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Atticus was accused of murdering Regilla by her brother Appius Annius Atilius Bradua, who was at the time Consul. At the trial in Rome, around 160 AD, it was alleged that she died in premature childbirth after being kicked in the stomach by a freedman of Atticus while she was eight months pregnant with her sixth child (Philostratus, pages 159-163 [see note 3]). It is thought that the child also died, either at the same time or shortly after. Atticus was acquitted, and went on to erect monuments to her, including the Odeion of Herodes Atticus in Athens. The question of whether he was motivated by genuine grief or a sense of guilt continues to be debated by modern scholars.

Herodes Atticus built a temple-like tomb for her on the couple's estate, the Pagus Triopius, just outside Rome ( see photo below). See:

Sarah B. Pomeroy, The Murder of Regilla: A Case of Domestic Violence in Antiquity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2007.

Maud W. Gleason, Making Space for Bicultural Identity: Herodes Atticus Commemorates Regilla, Version 1.0, July 2008. Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics, Stanford University.

Helen McClees, A Study of Women in Attic Inscriptions. Columbia University Press, New York, 1920. At the Internet Archive. |

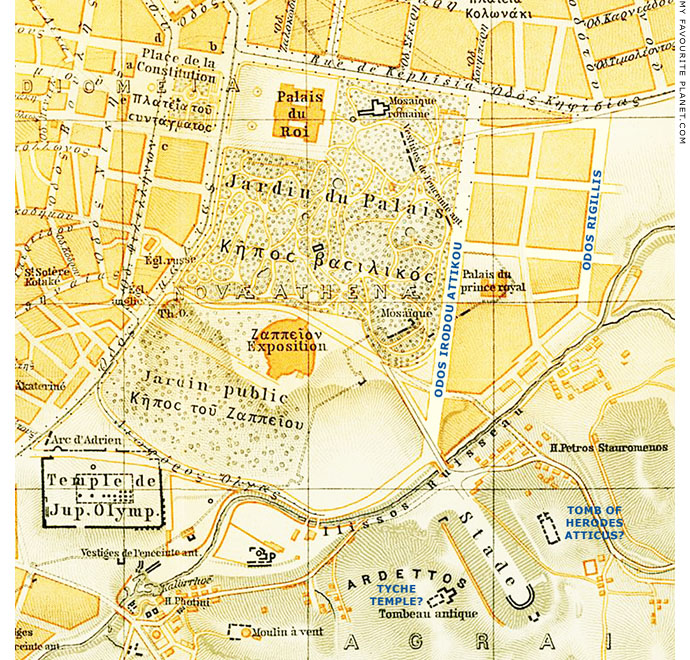

Rigillis Street (Οδός Ρηγίλλης), Athens,

named after Aspasia Annia Regilla.

Rigillis Street is the location

of Aristotle's Lyceum.

See Digging Aristotle

at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

| |

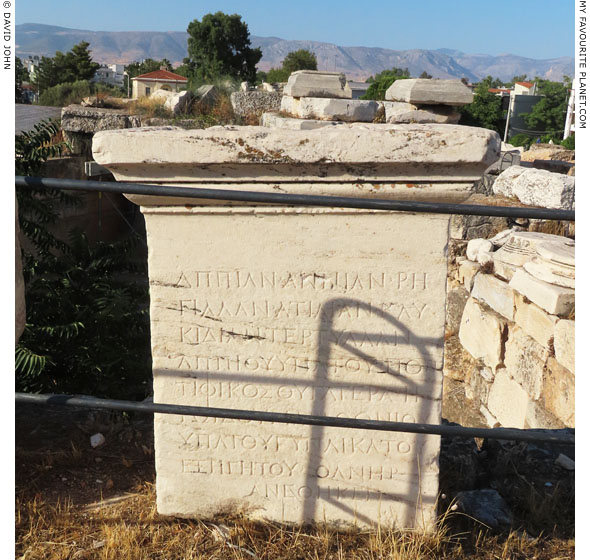

A base of a statue of Annia Regilla, found

in 1935 on the west side of the Forum of

Ancient Corinth. Dated around 143-160 AD.

The inscription on the base refers to a

statue, perhaps made during her lifetime,

dedicated by Herodes Atticus and set up

in front of the sanctuary of Tyche by the

boule (βουλή, city council) of Corinth. [9]

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. I 1658. |

| |

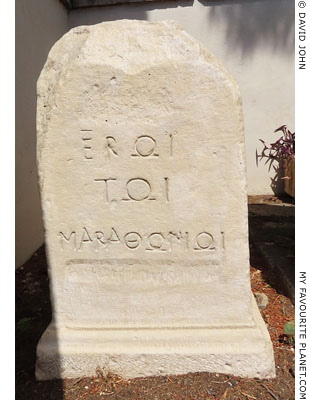

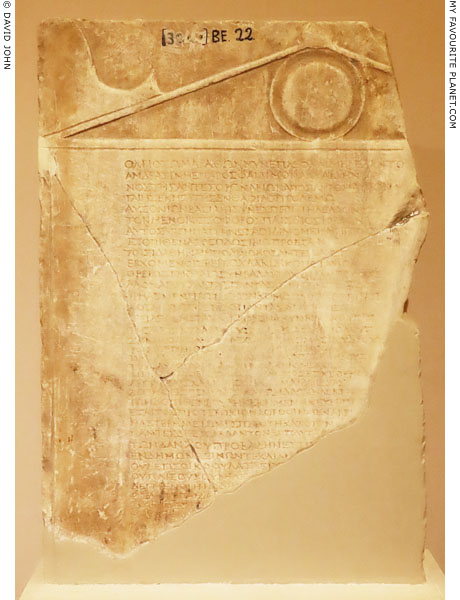

| |

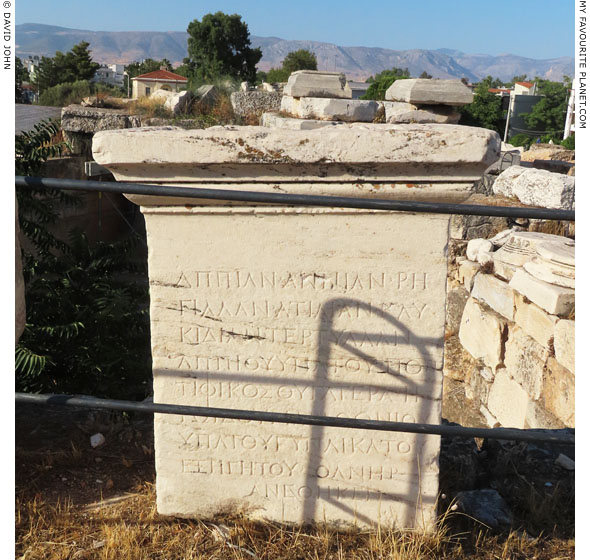

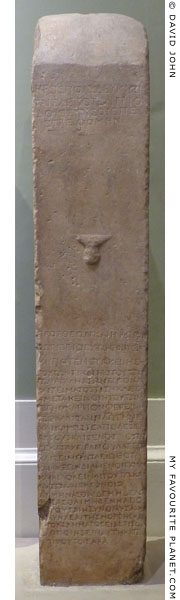

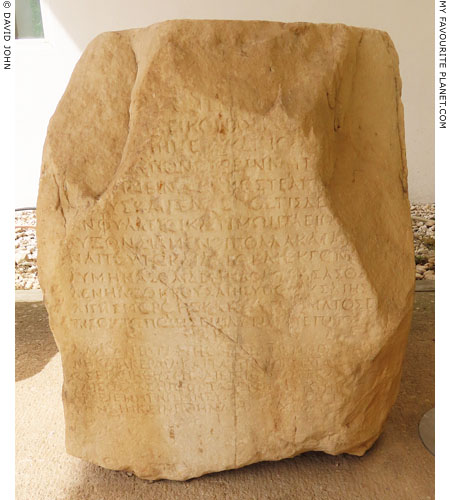

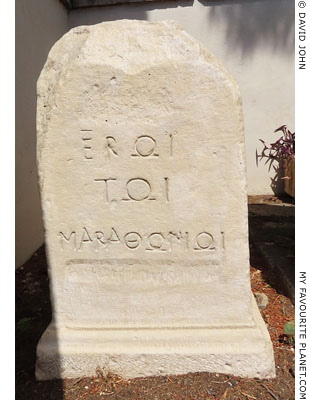

An inscribed marble base of a statue set up at Eleusis by

Herodes Atticus to honour his deceased wife, Annia Appia Regilla.

Circa 161 AD. Found in the court of the Telesterion,

the temple of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis.

Ἀππίαν Ἀννίαν Ῥή-

γιλλαν Ἀτιλίαν Καυ-

κιδίαν Τερτύλλαν,

Ἀππίου ὑπάτου πον-

τίφικος θυγατέρα, Ἡ-

ρώιδου Μαραθωνίου

ὑπάτου γυναῖκα τοῦ

ἐξηγητοῦ ὁ ἀνὴρ

ἀνέθηκεν. |

Appia Annia

Regilla Atilia

Caucidia Tertulla,

daughter of Appius

consul and pontifex,

wife of Herodes of Marathon

consul and

interpreter. Her husband

dedicated [this statue]. |

Inscription IG II² 4072 (= I Eleusis 476)

Eleusis Archaeological Site. Inv. No. E1002. |

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

Children of Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla |

|

|

|

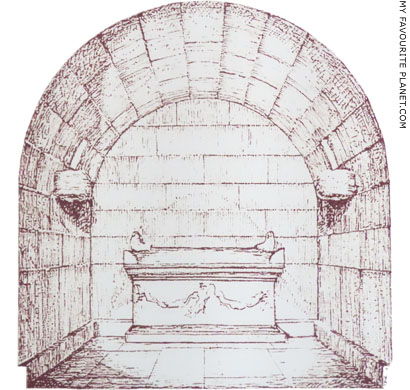

| |

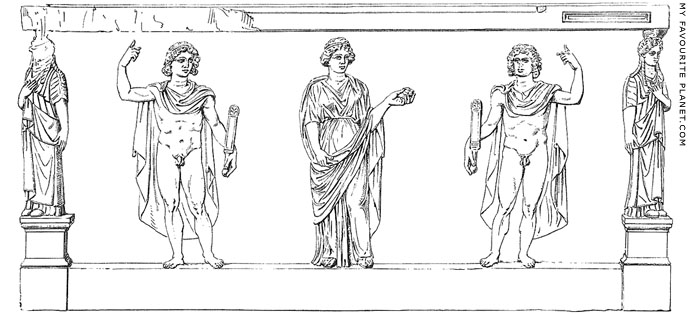

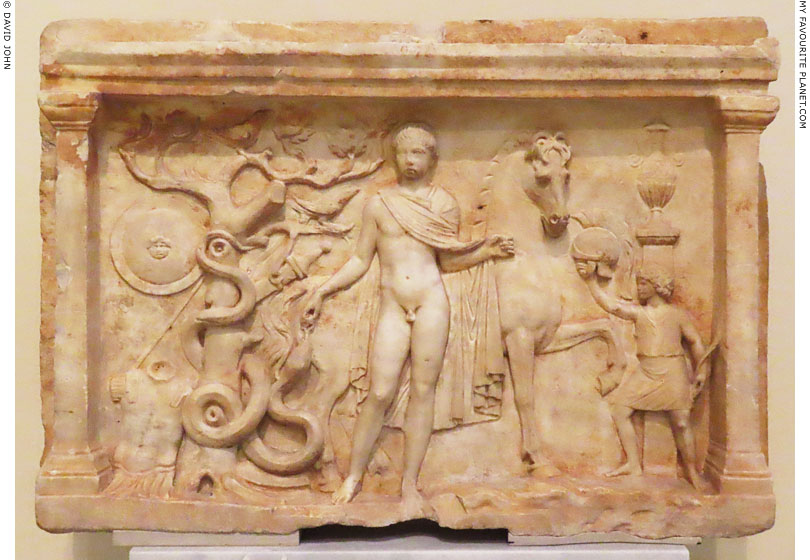

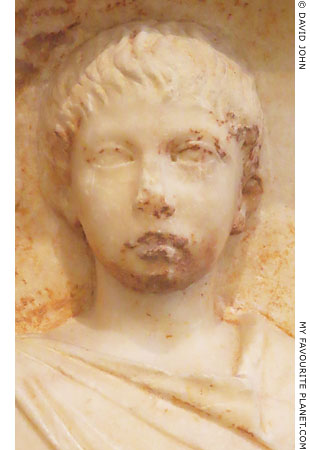

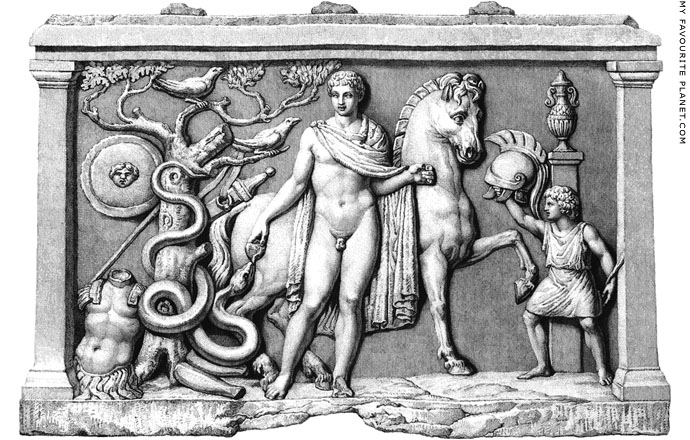

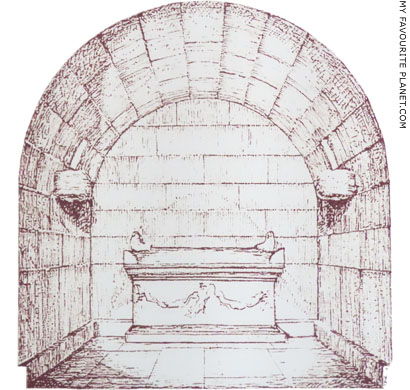

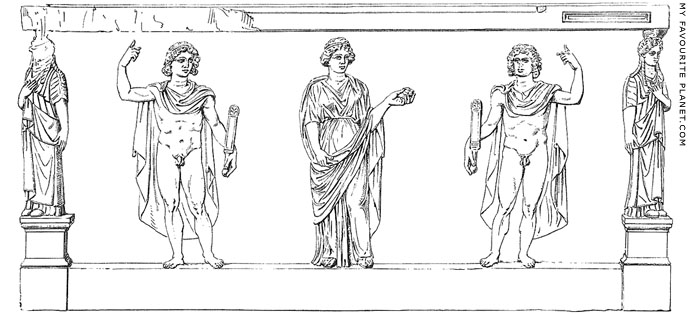

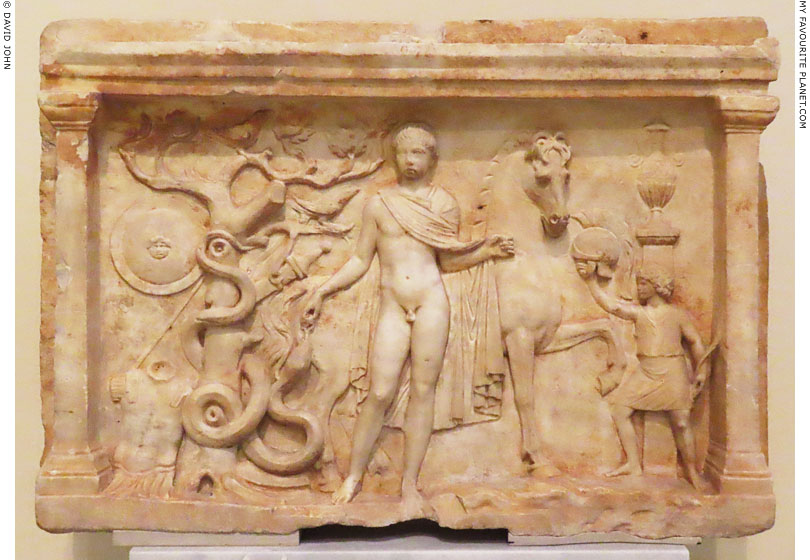

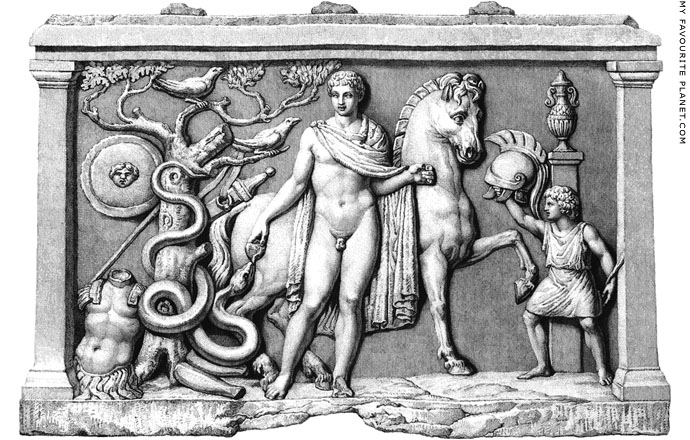

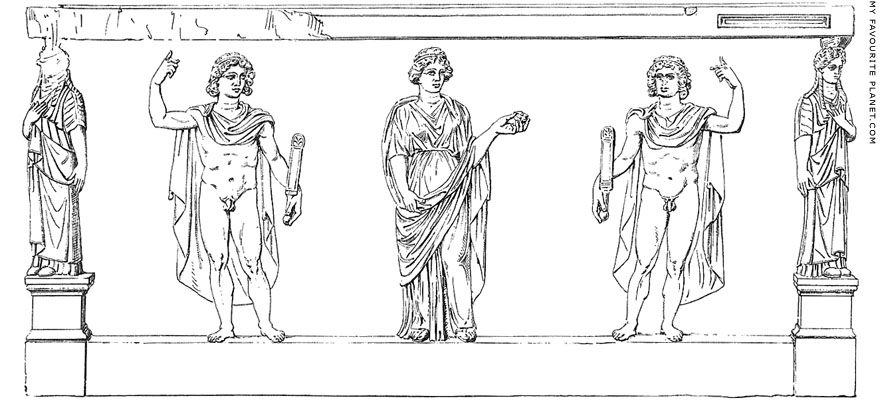

A relief of the Dioskouroi and their sister Helen of Troy on the front of the "Leda sarcophagus",

a marble sarcophagus in Kifissia, northeast of Athens. One of four sarcophagi in a marble tomb

discovered in Kifissia in September 1866, on what is thought to have been part of the estate of

Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla. The sarcophagi are believed to be the graves of four of their

six children who died at a young age (see below). This sarcophagus may have been made for

Elpinike (Ἐλπινίκη), their second child and first daughter.

See further information about the "Leda sarcophagus" below. |

| |

According to available evidence, Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla had six children.

For the conjectural dates of the births and deaths of the children, see the chronology above and note 8.

|

| 1. |

Son, unnamed (Claudius?), died in infancy (around 141-143 AD). Known only from a reference to Herodes grief over his death in a letter of Marcus Aurelius to Marcus Cornelius Fronto (Fronto, Epistulae, 1.6.10 [10]).

|

| 2. |

Daughter, Elpinike (Appia Annia Atilia Regilla Agrippina Elpinice Atria Polla [see note 1], around 143-165 AD). Perhaps named after the daughter of the Athenian general and statesman Miltiades (hero of the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, from whom Herodes claimed descent), and stepsister and lover of the statesman Kimon.

|

| 3. |

Daughter, Athenais (Marcia Annia Claudia Alcia Athenais Gavidia Latiaria, around 145-161 AD). Perhaps buried within the city walls of Athens (Philostratus, The lives of the Sophists, Book II, section 558, see quote below).

|

| 4. |

Son, Regillus (Tiberius Claudius Herodes Lucius Vibullius Regillus, around 146-161 AD).

|

| 5. |

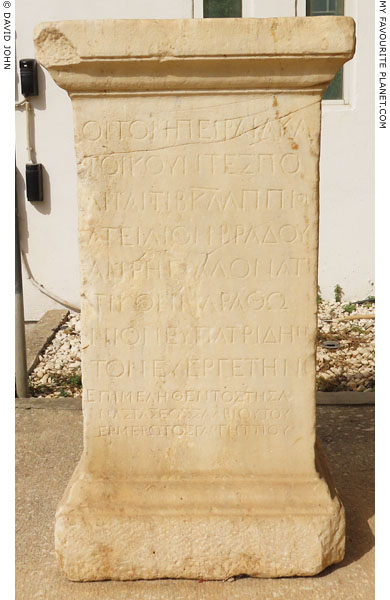

Son, Atticus Bradua (Tiberius Claudius Marcus Appius Atilius Bradua Regillus Atticus, around 152 - after 209 AD). The only child to outlive his parents, he was consul ordinarius in 185 AD, an archon of Athens in 187 AD and some time after proconsul of a Roman Province, perhaps Africa. He was honoured as a herald by the Athenian boule in 209 AD.

|

| 6. |

Unnamed child, thought to have been a son born prematurely, and to have died with Regilla or 3 months later, around 160 AD (see below). |

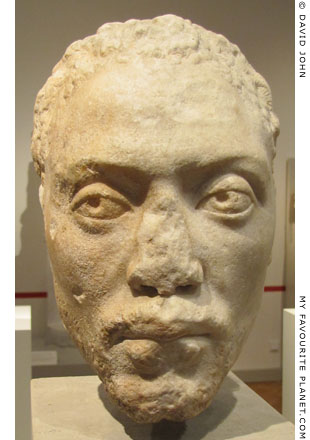

| |

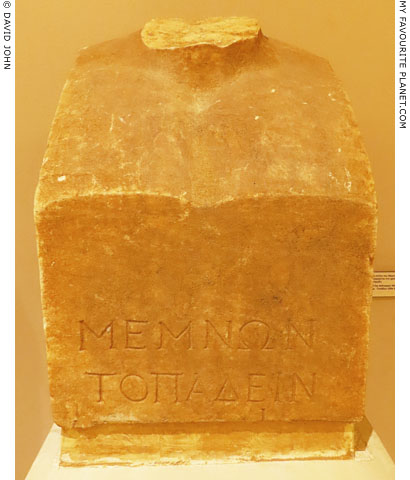

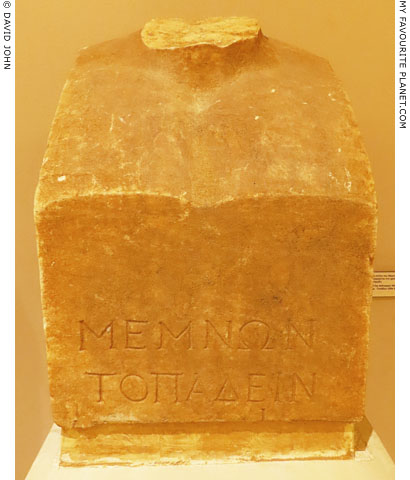

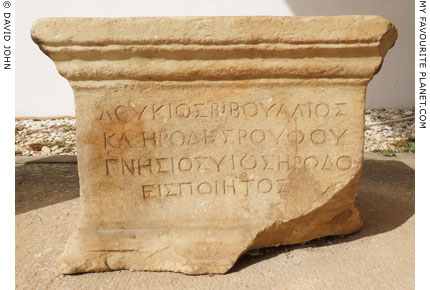

Herodes Atticus' three known adopted sons (dates unknown):

Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς, Achilleus) see below;

Memnon (Mέμνων), an African ("an Ethiopian"), see photo above;

Polydeukion (Πολυδευκίων), also referred to as Polydeukes (Πολυδεύκης), see below.

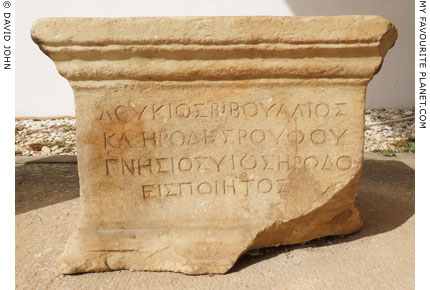

Lucius Vibullius, illegitimate son of Rufus see below. |

|

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

The Triopion estate, Rome |

|

|

|

| |

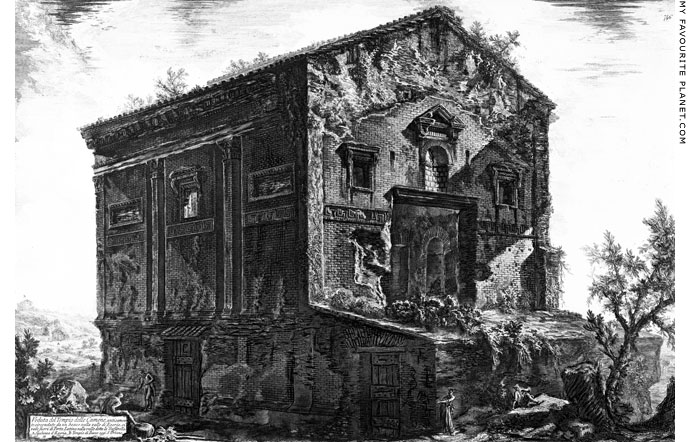

The "Tomb of Annia Regilla" in Caffarella Park, near the Via Appia, southeast of Rome city centre.

|

The tomb was built by Herodes Atticus for his deceased wife on his estate, known as the Pagus Triopius (Triopius Farm), in the Valle della Caffarella, between the Via Appia and the Almone river, outside the Aurelian Wall. Since Annia Regilla is thought to have been buried near Athens (although her tomb has not yet been found, see below), this may have been a cenotaph (κενοτάφιον, kenotaphion, symbolic empty grave) or shrine to her, unless her remains had been returned to Rome.

The area around the tomb is open to the public

on Saturdays and Sundays, 10 am - 4 pm (6 pm in summer).

It is thought that the estate, on the left side of the Via Appia between the second and third milestones, may have originally belonged to the family of Annia Regilla, and have been part of her dowry when she married Herodes Atticus. As part of his efforts to proclaim his grief over her death, Herodes renamed the estate Triopion (Τριόπιον, perhaps after the mythical hero Triopas [11]), dedicated to the gods of the underworld and the funeral cult of Regilla. The area included a temple dedicated to Demeter and Persephone and the "new Demeter", the deified Faustina Major (Annia Galeria Faustina, circa 100-140 AD), wife of Emperor Antoninus Pius. A statue of Annia Regilla, "neither god nor mortal", stood in the temple (see below).

Much of the area of the Triopion was later taken over by the palace of Emperor Maxentius (reigned 306-312 AD). The temple of Demeter was converted in the 9th - 10th century into the church of Sant' Urbano alla Caffarella (see below), an oratory dedicated to Saint Urban who was Pope 222-230 AD. |

|

| |

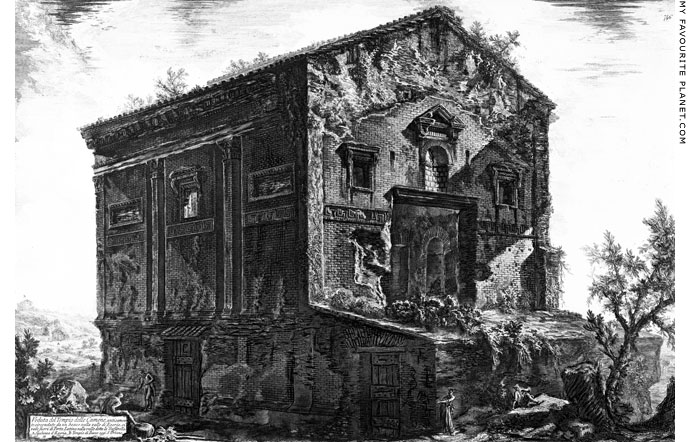

An etching of the tomb of Annia Regilla made 1748-1774 by Giambattista Piranesi (1720-1778).

The view shows the front (east) and south side of the tomb, labelled by Piranesi as the "Tempio

delle Camene". It is surrounded by a number of small imaginery figures, which give the impression

that the building is much larger than actually is. In the background, at the extreme left of the image

is the church of Sant' Urbano, the ancient temple of Demeter and Persephone (see below).

Source: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francesco Piranesi and others, Vedute di Roma, Tomo I

(Volume 1 of 2), tavolo 62. Presso l'Autore a strada Felice..., Rome, 1779. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

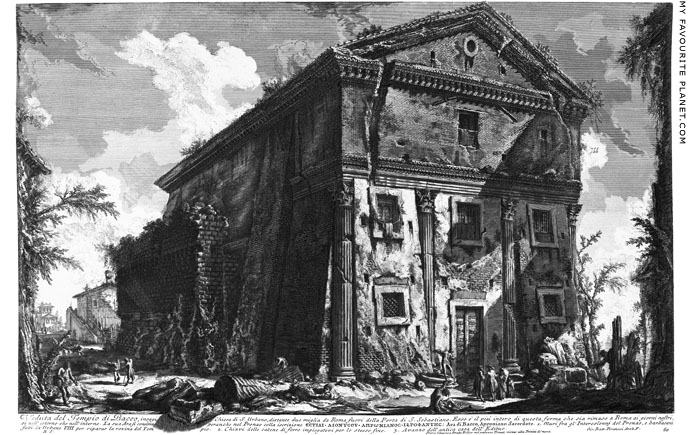

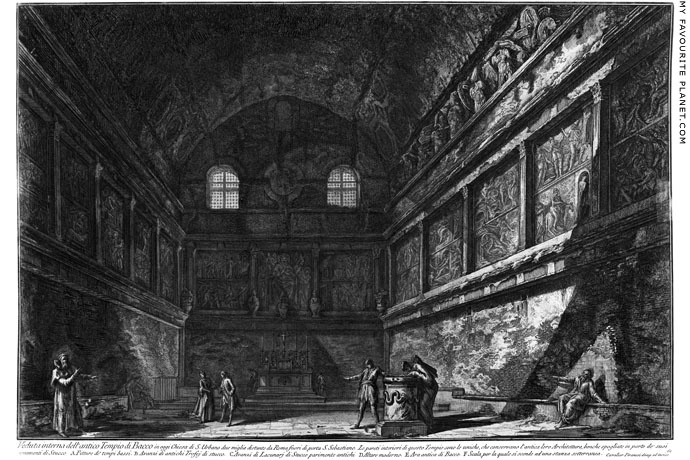

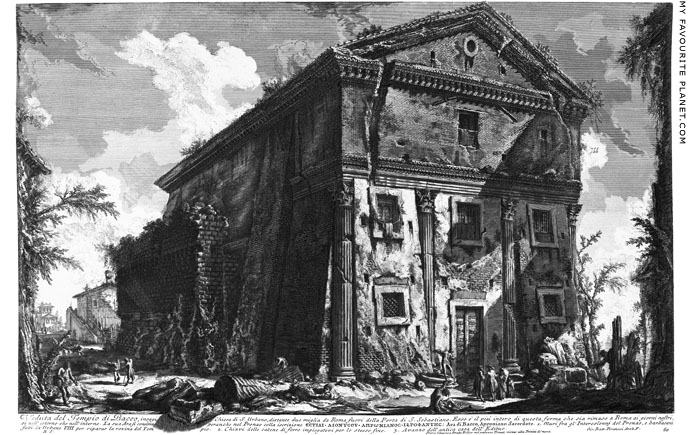

An etching of the church of Sant' Urbano alla Caffarella by Giambattista Piranesi.

Source: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francesco Piranesi and others, Vedute di Roma, Tomo I

(Volume 1 of 2), tavolo 60. Presso l'Autore a strada Felice..., Rome, 1779. At the Internet Archive.

|

| |

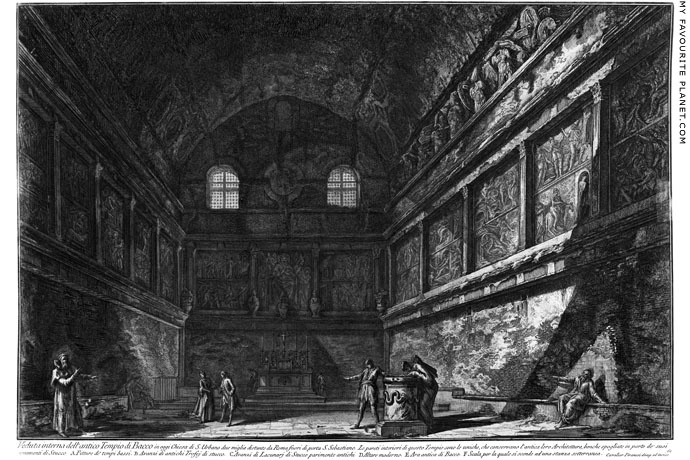

The temple of Demeter and Persephone on the Triopion estate of Herodes Atticus near the Via Appia, southeast of Rome. The ruined building was restored by Pope Urban VIII Barberini in 1634, when it was stabilized by massive buttresses, and the spaces between the four Corinthian columns of the front porch (pronaos) were bricked up.

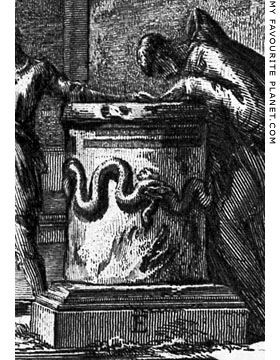

It was believed at the time to have been the Tempio di Bacco (temple of Bacchus), because of an inscribed cylindrical altar found inside (see image, right) that had been dedicated to Dionysus in the second half of the 2nd century by the hierophant Apronianus, a high priest of Demeter at Eleusis.

The barrel vaulted ceiling was decorated with octagonal panels with stucco reliefs, most of which have not survived. The central panel still has part of a relief showing a male and female, thought to represent Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla, walking in a procession bringing offerings to the deity (or deities). Along the base of the ceiling is a frieze with a coat of arms (see Piranesi's etching of the church interior below). In the 11th century the upper walls of the building's interior were covered by paintings with Christian themes, scenes from the New Testament and the martyrdom of Saint Urban and Saint Cecilia, which were restored by the Barberini family in 1637. |

|

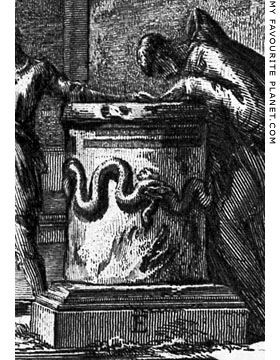

The cylindrical altar inside the church,

decorated with a relief of a snake

coiled around the shaft and inscribed

with a dedication to Dionysus

by the hierophant Apronianus.

Detail of Piranesi's etching of the

interior of the church of Sant' Urbano

alla Caffarella (see below). |

|

| |

An etching of the interior of the church of Sant' Urbano alla Caffarella, by Giambattista Piranesi.

Unfortunately, the picture of the dark interior does not include the stucco relief on the ceiling.

Source: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francesco Piranesi and others, Vedute di Roma, Tomo I, tavolo 61. |

| |

|

|

|

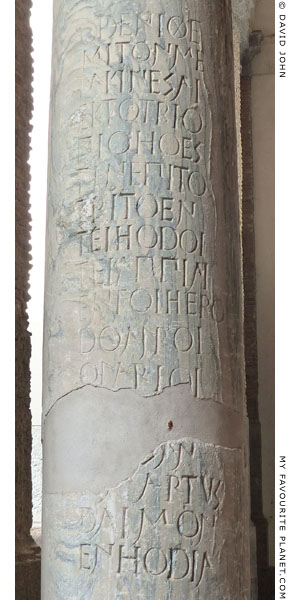

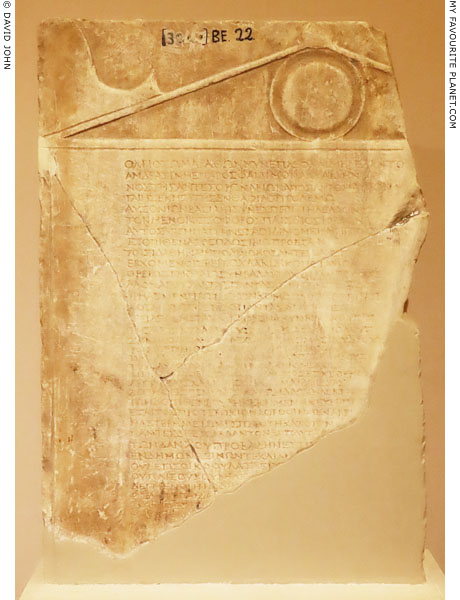

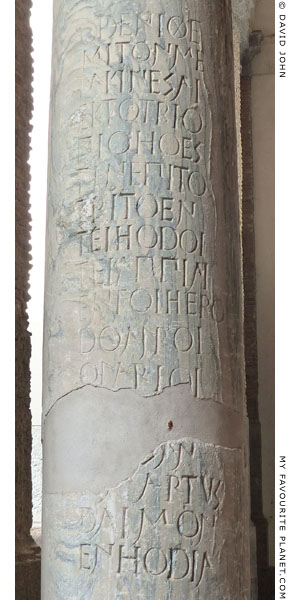

One of two inscribed marble columns from the temple of Demeter and Persephone in the Triopion.

Circa 138-161 AD. Found in 1607 near the

Tomb of Caecilia Metella on the Via Appia, Rome.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. Nos. 2400 and 2401. From the Farnese Collection.

|

|

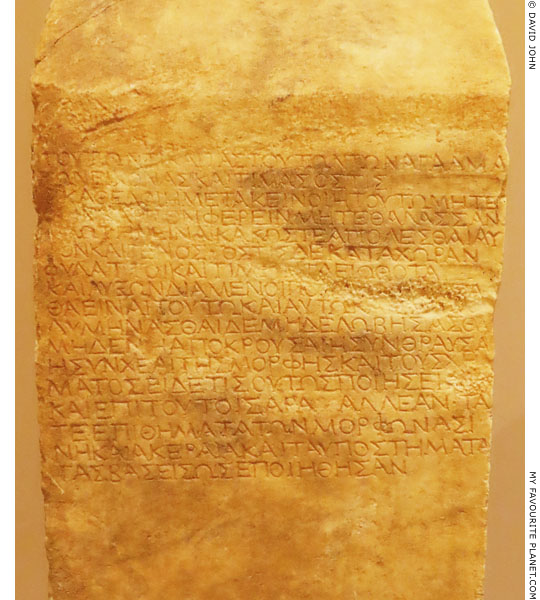

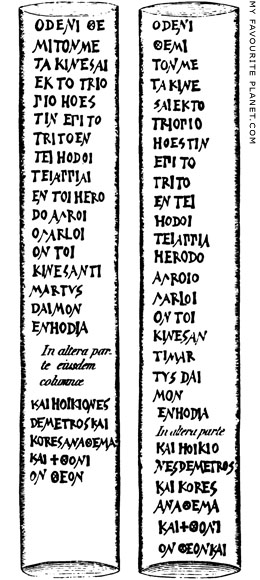

The Greek inscriptions on the two columns as well as those on two marble steles (see below) found at the site of the Triopion are unsurprisingly known as the "Triopian inscriptions". As with other dedications and memorials set up by Herodes Atticus, the dedications include curse texts (see below), threatening thieves and vandals with the wrath of the underworld deities:

καὶ ℎοι κίονες Δέμετρος καὶ Κόρες ἀνάθεμα καὶ χθονίον θεο͂ν· καὶ ὀδενὶ θεμιτὸν μετακινε͂σαι ἐκ το͂ Τριοπίο ℎό ἐστιν ἐπὶ το͂ τρίτο ἐν τε͂ι ℎοδο͂ι τε͂ι Ἀππίαι ἐν το͂ι ℎερόδο ἀγρο͂ι. ὀ γὰρ λο͂ιον το͂ι κινέσαντι· μάρτυς δαίμον Ἐνℎοδία

And these columns are an offering to Demeter, Kore, and the chthonic deity. No one is permitted to remove anything from the Triopion which is at the third [milestone] of the Appian Way in the land of Herodes. No good will come to him who moves it: Enhodia the [underworld] daimon is witness.

Inscription IG XIV 1390 (IGUR II 339a and IGUR II 339b at The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI).

Source of drawings, right:

August Boeckh (editor), Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, Volume I, No. 26, pages 42-46. Officina Academica, Berlin, 1828. At Googlebooks.

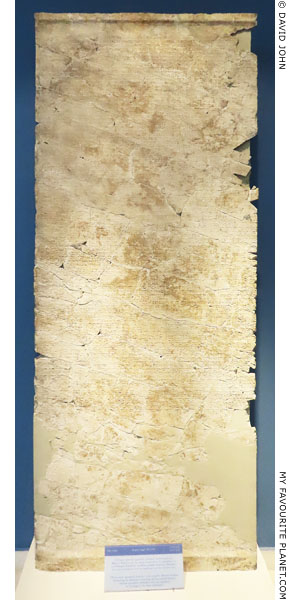

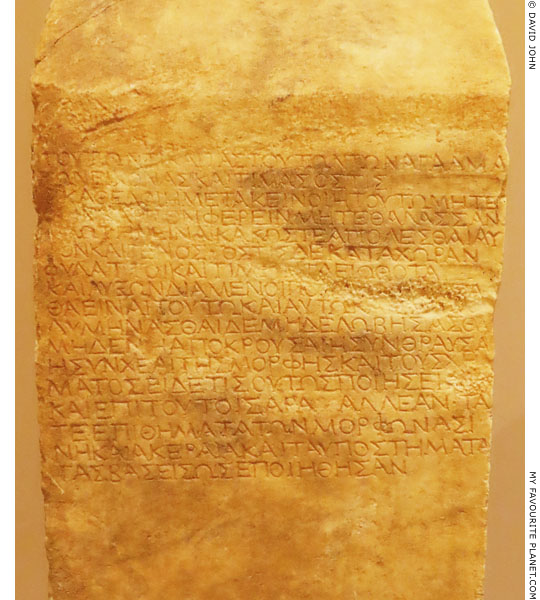

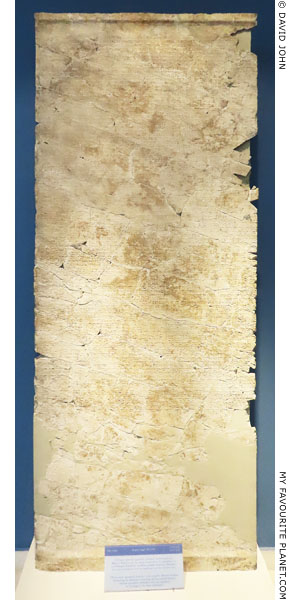

Two marble marble steles, found at the site of the Triopion around the same time as the columns, are inscribed with an epitaph for the heroized Annia Regilla, written in Greek hexameter verse. Stele B was discovered in 1607 and stele A around 1616. They were acquired by Cardinal Scipione Borghese for his collection in the Villa Borghese on the Pincian Hill, Rome, and they remained there until 1808, when they were taken to Paris by Napoleon, and are now in the Louvre.

The first and main part of the epitaph is the fifty nine line poem on stele A, which is 122 cm tall. At the top, written in letters larger than the rest of the text, is the signature of Marcellus (Μαρκέλλου, genitive), believed to be the poet Marcellus of Side (Μάρκελλος Σιδήτης, Markellos Sidetes), otherwise known for long poems on medical remedies, werewolves and fish.

The text, dense with ancient literary allusions to deities, heroes and mythological events, refers to a shrine surrounding a seated statue of Regilla in the sanctuary, "the sacred image of the well-girt wife" dedicated to the New Deo (Faustina Major) and the Old (Demeter). Roman women, addressed as "daughters of the Tiber", are invited to bring her sacred offerings. She is praised as "she of the beautiful ankles", "descended from Aeneas and was of the race of Ganymede". She had been an attendant to Faustina in her youth and a priestess of her cult.

Being "neither mortal, nor divine", Regilla "has neither sacred temple nor tomb, neither honours for mortals, nor honours like those for the divine". This seems to indicate that the nearby "Tomb of Annia Regilla" (see above) had not yet been built. The poem also states that she is buried in Attica: "In a deme of Athens is a tomb for her like a temple". Frustratingly for historians and archaeologists, the name of the deme is not given, and the tomb has yet to be found.

Herodes is described on one hand as a proud descendant of Kekrops, Keryx and Theseus. "In Greece there is no family or reputation more royal than Herodes'. They call him the voice of Athens." On the other hand he is portrayed as a pitiable "grieving spouse lying in the middle of his widower's bed in harsh old age", mourning the loss of his wife and children, who have been snatched from his "blameless house". We are told that "half of his many children" had already died at the time the dedication was made and that "two young children are still left", probably Elpinike and Atticus Bradua, who is also alluded to in the text.

The thirty nine line inscription on the 117 cm high stele B calls upon the goddesses Athena and Nemesis to protect "this fruitful estate of the Triopeion sacred to Deo [Demeter], a place friendly to strangers, in order that the Triopeion goddesses be honoured among immortals". Addressing the reader, the poem continues: "For you Herodes sanctified the land and built a rounded wall encircling it not to be moved or violated, for the benefit of future generations." The last part contains a curse text, threatening divine retribution on anyone who disturbs the sanctity of the estate.

Inscription IG XIV 1389 (= IGUR III 1155 at The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI).

See: Malcolm Davies and Sarah B. Pomeroy, Marcellus of Side’s epitaph on Regilla (IG XIV 1389): an historical and literary commentary. In: Prometheus, Volume 38, pages 3-34. Firenze University Press, 2012. PDF at Firenze University Press Open Journal Systems. The article includes the Greek texts of the inscriptions, English translations and commentary, as well as photos of the two steles. |

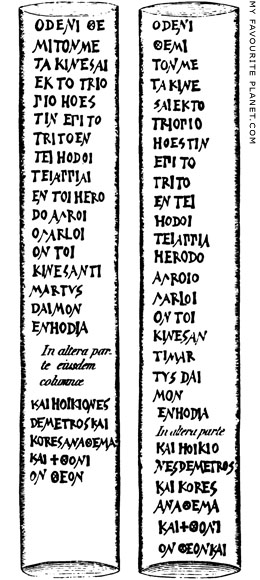

Drawings of the inscriptions

on the Triopion columns. |

| |

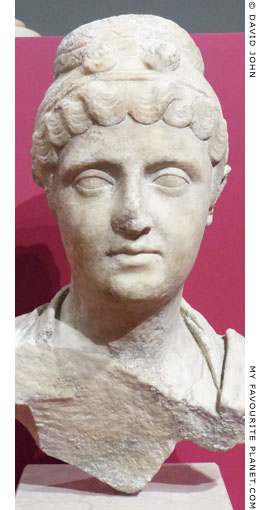

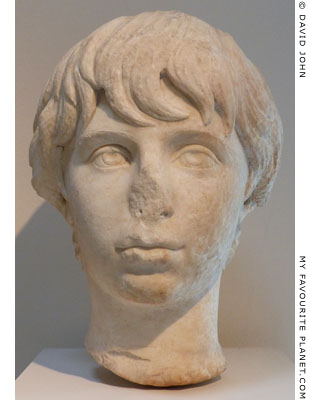

Detail of a marble portrait bust of

Faustina Major (circa 100-140 AD),

wife of Emperor Antoninus Pius.

Portrait of the Dresden type.

Around 150 AD.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

Hamburg.

Inv. No. 11992.337 / St. 3934.

Property of the Stiftung für die

Hamburger Kunstsammlung. |

| |

| |

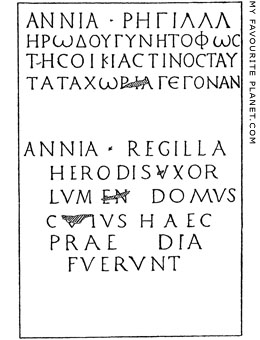

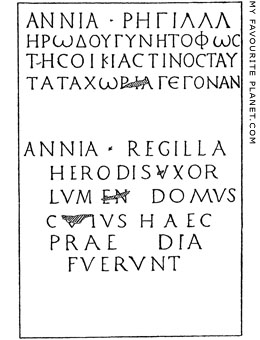

Another inscription from the Triopion is a bilingual dedication to Annia Regilla, in Greek and Latin, on a 198 cm high grey marble column, thought to have been a base for a statue or bust (see drawing, right). Around 309 AD the other side of the column was reinscribed as a milestone (the seventh from the Porta Capena), during repair works to the Via Appia by Emperor Maxentius. In the Middle Ages it was moved to the Sant' Eusebio monastery on the Esquiline Hill, Rome, where it was found in 1698. It was later seen in the monastery garden by Cardinal Alessandro Albani who purchased it for his collection. It is now in the Capitoline Museums. Inv. No. NCE 2532.

Ἀννία · Ῥηγίλλα

Ἡρῴδου γυνή, τὸ φῶς

τῆς οἰκίας, τίνος ταῦ-

τα τὰ χωρία γέγοναν

Annia · Regilla

Herodis uxor

lumen domus

cuius haec

praedia

fuerunt

Annia Regilla, wife of Herodes, the light of the house, to whom these lands once belonged.

Inscription IG XIV 1391 (= CIG 6184 and IGUR II 340 at The Packard Humanities Institute).

The wording is similar to a dedication on an inscribed altar found in the mid 19th century at a ruined church between Kifissia and modern Marousi.

Ἀππία Ἀννία Ῥηγίλλα Ἡρῴδου γυνή, τὸ φῶς τῆς οἰκίας

Appia Annia Regilla, wife of Herodes, the light of the house.

Inscription IG II² 13200 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

It has been suggested that the altar may be associated with Regilla's tomb, the location of which remains unknown. |

|

Drawing of the bilingual dedication

to Annia Regilla on a marble column

from Rome.

Inscription IG XIV 1391.

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. NCE 2532.

Source: Christian Hülsen, Zu den

Inschriften des Herodes Atticus.

In: Rheinisches Museum für

Philologie, Band 45 (1890), pages

284-287. PDF at Rheinisches

Museum für Philologie. |

|

| |

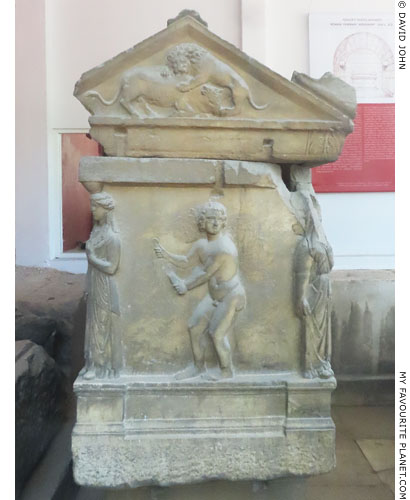

|

|

|

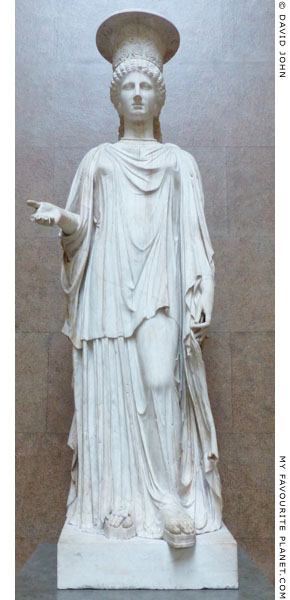

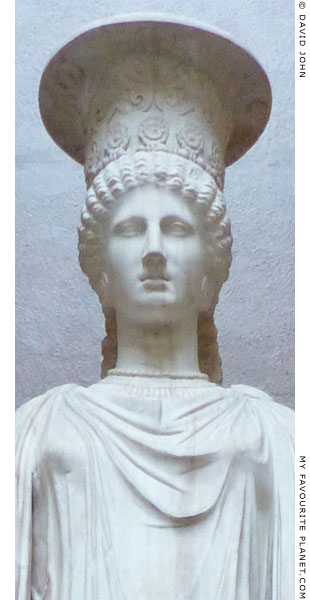

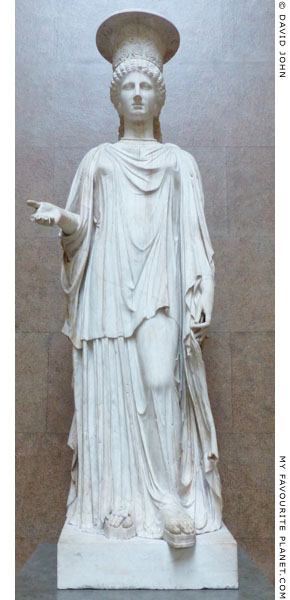

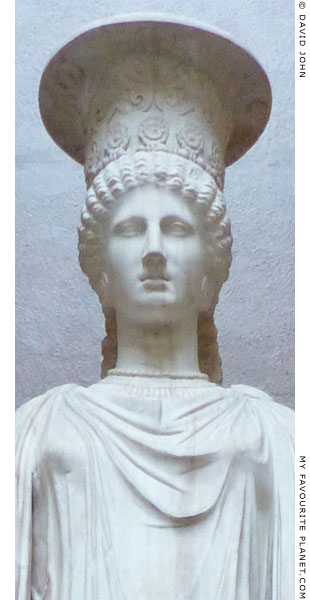

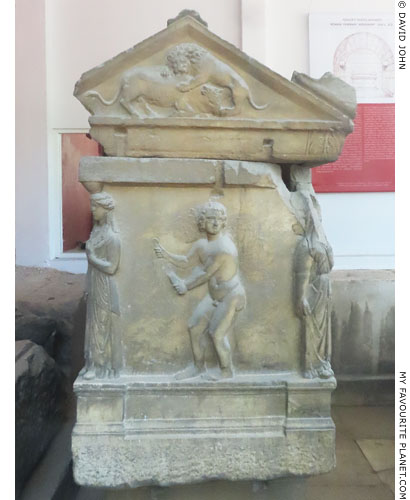

The "Townley Caryatid" from the Triopion.

Circa 140-170 AD. Classicist Neo-Attic style. Found 1585-1590 near the Via Appia.

Pentelic marble. Over lifesize, height 220 cm (237 cm with restored plinth).

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1805.7-3.44 (Sculpture 1746).

Acquired in 1805 from the Townley Collection. |

|

| |

The restored frontal figure wears a tall, tapering kalathos (a headdress particularly associated with the cult of Demeter), decorated with a row of palmettes and lotus buds, a row of rosettes and a bead-and-reel rim; rosette earrings, a bead necklace above a strap necklace with seed-shaped pendants; a peplos and a himation, fastened at the shoulders by large round buttons; and platform sandals. She has a melon hairstyle, with corkscrew locks falling over her back. The head faces forward, the fnely-carved face is expressionless, the lips slightly parted. Her raised right forearm is extended forwards with her open hand palm upwards. Her left arm is at her side. Her bent left leg is visible through the thin peplos, the left foot advanced. The right leg is obscured by the vertical folds of the peplos, beneath which the front of the foot can be seen.

The figure is one of six caryatids, differing in several details, found at the Triopion site. They formed a colonnade in a religious sanctuary, probably of the temple of Demeter and Persephone built by Herodus Atticus. This is one of two caryatids found 1585-1590 at the Triopion site, the other is in the Vatican Museums, Inv. No. 2270. In an 1812 catalogue of the British Museum (see image and citation, right) the findspot was described as "amongst some ancient ruins in the Villa Strozzi, situated on the Appian Road, about a mile and a half beyond the tomb of Caecilia Metella, commonly called Capo di Bove."

Another three were discovered there in 1765/1766 and are now in the Villa Albani-Torlonia, Rome (see Antinous), including a fragmentary caryatid, the head of which is attached to part of a pilaster signed by two unknown Athenian sculptors, Kriton and Nikolaos:

ΚΡΙΤΟΝ ΚΑΙ ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΣ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΙ ΕΠΟΙΟΥΝ

Also found there at this time was a statue identified as Dionysus, prompting Giambattista Piranesi (1720-1778), who was present at the excavation, to believe that the caryatids were part of a temple to the wine god. [12]

A sixth fragmentary caryatid was discovered during excavations in 2003-2005.

The "Townley Caryatid" was acquired by Pope Sixtus V (Felice Peretti di Montalto, 1521-1590) and kept at the Villa Peretti Montalto, which was sold in 1696 to Cardinal Giovanni Francesco Negroni and became known as Villa Negroni. Antiquities in the collection of the villa were sold in 1785 to the art dealer Thomas Jenkins (1724-1798). The caryatid was among a number of artworks from the collection purchased from him in 1786 by the British collector Charles Townley, who believed it to be a statue of Isis.

Professor Olga Palagia has recently reported suggestions that the head of one of three caryatids found in 1882 in central Athens (now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, not on display) is a duplicate of that of the Townley Caryatid, and that the three figures may have originally decorated a now lost propylon of the City Eleusinion near the Athenian Agora [13]. These suggestions may strengthen the association of the Triopion caryatids with the temple of Demeter there.

See also:

The caryatids of the Erechtheion on the Athens Acropolis.

A caryatid from Tralles, Ionia |

|

An engraving of the Townley Caryatid

in an early catalogue of the British

Museum, in which it is described as

"a female statue, larger than life,

with a modius on the head."

Taylor Combe (editor), A description

of the collection of ancient marbles

in the British Museum, Part 1,

Plate IV. Longman, Hurst, Rees,

Orme and Co., London, 1812. |

|

| |

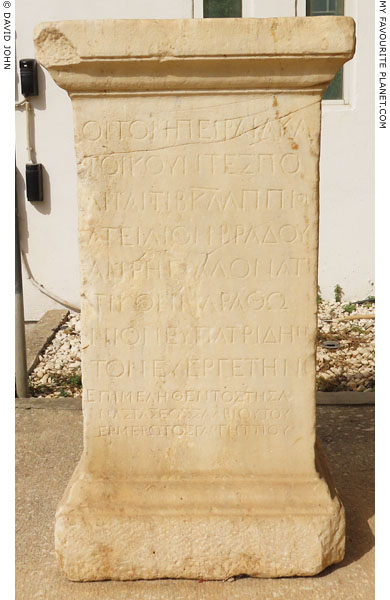

A marble epistyle from a building in Athens with two dedicatory inscriptions

for Herodes Atticus and his second daughter Claudia Athenais by the Council

of the Areopagus, Council (βουλὴ, Boule) of the 600 and the Assembly of the

People (δῆμος, demos). Before 150 AD.

|

ἡ είου πάλὴ καὶ ἡ βουλὴ τῶν ἑξακοσίων καὶ ὁ δῆμος Κλαυδίαν Ἀθηναΐδα εὐεργεσίας ἕνεκεν.

ἡ ἐξ Ἀρείου πάγουλὴ καὶ ἡ βουλὴ τῶν ἑξακοσίων καὶ ὁ δῆμος τὸν ἀρχιερέα τῶν Σεβαστῶν διὰ

βίου Τιβ Κλαύδιον Ἀττικὸν Ἡρώδην Μαραθώνιον εὐεργεσίας ἕνεκεν.

Athens Epigraphical Museum. Inv. No. EM 10313.

Inscription IG II² 3594 / 5 (IG III 664 and IG III 665 [14]).

Marcia Annia Claudia Alcia Athenais Gavidia Latiaria (circa 143-161 AD), usually referred to

as Athenais (Άθηναΐς) or Athenaides (Ἀθηναΐδες), was the third child of Herodes Atticus

and Annia Regilla, and their second daughter (see photo below). |

|

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

The Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in Olympia |

|

|

|

| |

The remains of the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in the Sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia.

|

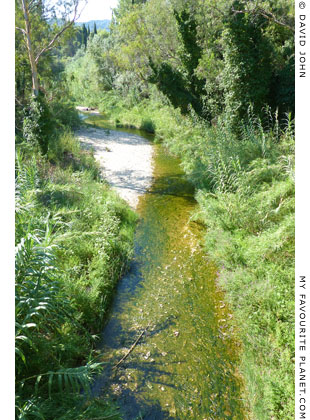

The Nymphaeum (Greek, νυμφαῖον, nymphaion) was an monumental fountain on the lower slope of the Kronion (Κρόνιον, Kronos Hill), on the north side of the Altis, the sacred area of the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia. It stood between the Heraion (Ἥραιον, Temple of Hera) and the terrace of treasuries set up by Greek cities. Supplied with water by a 4 kilometre long aqueduct fed by local springs, it is thought to have been the first construction to provide the sanctuary with running, fresh water in its long history. Previously water was taken from wells and the Kladeos river (Κλάδεος), which was a winter torrent and sometimes dry in summer. Fresh water had often been in short supply during the Olympic Games, which were held in the hottest months July and August. [15]

The 33 metre wide fountain was at least 13 metres tall, perhaps as high as 18 metres, and because of its hillside position at the highest part of the Altis, it stood above the level of the sanctuary's centre. It thus dominated the area, and only the 23.5 metre tall Temple of Zeus was taller.

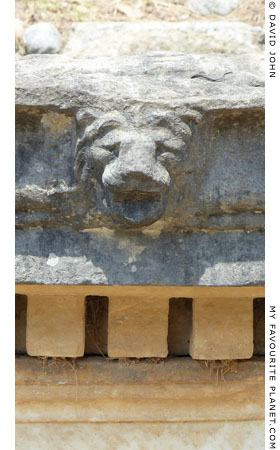

Built of brick and clad in marble, the Nymphaeum consisted of a semicircular basin with a diameter of 16.8 metres into which water poured through a row of bronze spouts decorated with stone lion head reliefs. In turn water from spouts in the front wall of the basin flowed into a 21.9 metre long and 3.43 metre wide rectangular pool 2.5 metres below it. From the front wall of this lower pool spouts fed a long channel which ran along the front of the monument and around the sanctuary. At either end of the long pool stood a monopteros (μονόπτερος, an open, circular, temple-like building [16]) with a conical marble roof supported by a ring of eight Corinthian columns, in which stood a statue, probably of an emperor. Parts of the two monopteroi stand on the site (see photos, right).

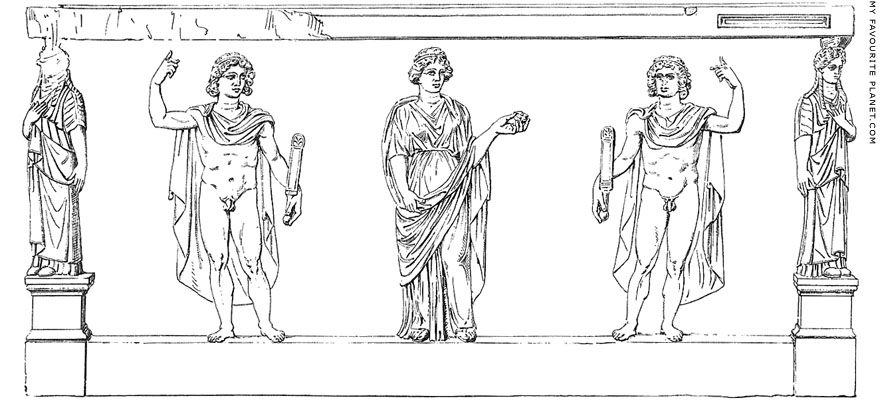

Over and around the curved rear edge of the top basin was a three-storey exedra (semicircular recess) supported at the rear by buttresses, designed as the decorative crown of the monument. The spouts along the front wall of the lowest storey fed water from the aqueduct into the basin below. Each of the two top storeys had a row of 12 arched niches framed by double Corinthian columns, in which stood statues of Herodes Atticus, Regilla, the emperors Antoninus Pius, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius as well as members of their respective families. In a central niche on each storey (probably the sixth niche from the left) stood a statue of Zeus (see photo below).

Regilla's inscribed bull statue (see below) is thought to have stood on top of the centre of the wall of the top basin. According to the inscription on its side the fountain was dedicated by Aspasia Annia Regilla to Zeus. It is thought that she initiated and paid for the building of the Nymphaeum, while her husband Herodes Atticus financed the construction of the aqueduct.

"He [Herodes] also dedicated the stadium at Pytho to the Pythian god, and the aqueduct at Olympia to Zeus..."

Philostratus, The lives of the Sophists, section 551, page 149 [see note 3].

It has been suggested that the fountain should properly be called the Nymphaeum of Annia Regilla, although some scholars believe that Herodes may have been responsible for its construction and dedicated it in his wife's name.

It was for long generally agreed by scholars that the Nymphaeum was built between 149 and 153 AD, particularly since it is thought that Regilla was the priestess of Demeter Chamyne during the 233rd Olympiad in 153 AD and that the building was completed by the opening of the games. However, some scholars believe that it may have been completed around 160 AD or even later, after Regilla's death. It is not mentioned by Pausanias, who visited Olympia around 155 AD. This makes the dating of the various statues more difficult to estimate.

A number of bases of the statues from the Nymphaeum, many in fragments, were found by archaeologists in 1880-1888 in or near the Nymphaeum, and others were discovered in 1877-1878 built into the floor of an early Christian church. Inscriptions on the surviving bases state that the statues of the emperors' and their family members were dedicated by Herodes Atticus, while the statues of Herodes, Regilla and their family members were dedicated by the citizens of the city of Elis (Ἦλις), in whose territory Olympia stood and who controlled the Olympic Games.

Some of the surviving statue bases now stand in front of the remains curved back wall of the Nymphaeum, and can be seen in the photo above. Unfortunately, they are too high and far away from the footpath to read the inscriptions.

Many of the statues (mostly headless), displaced heads and other fragments from the Nymphaeum are now in the Olympia Archaeological Museum, while some are currently in the nearby Museum of the History of the Ancient Olympic Games. Other statues were taken to Berlin by the German archaeologists, as part of an agreement with the Greek government. See photos below.

Attempts have been made to match heads and other fragments to statues, and statues to the inscribed bases in order to identify the individual figures. Several identifications remain subjects of debate. So far we have included below only photos of a few of these statues. |

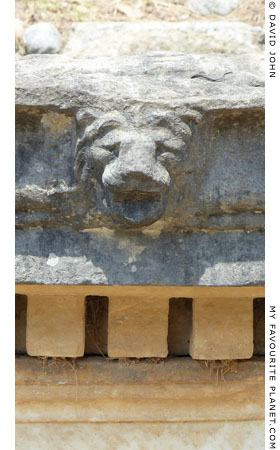

One of the row of lion head reliefs which

decorated the top of the entablature

of each monopteros of the Nymphaeum

of Herodes Atticus, Olympia. They had

no function but imitated the lion head

spouts of the fountain. |

| |

A fragment of a carved marble roof

tile of one of the monopteroi.

Another fragment is in now the

Antikensammlung of the Berlin State

Museums (SMB). Inv. No. SK 1441.

See www.smb-digital.de/... at the

SMB website Collections database. |

| |

A marble Corinthian pilaster capital

from one of the monopteroi.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

A marble statue of a bull from the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in Olympia,

inscribed on the right side with a votive dedication of Aspasia Annia Regilla

as the priestess of Demeter Chamyne (see below):

Ῥήγιλλα, ἱέρεια Δήμητρος, τὸ ὕδωρ καὶ τὰ περὶ τὸ ὕδωρ τῷ Διί

Regilla, priestess of Demeter, dedicated the water and the fixtures to Zeus.

Inscription IvO 610. Wilhelm Dittenberger and Karl Purgold,

Die Inschriften von Olympia (IvO), in Olympia, 5. Berlin 1896.

Around 149-153 AD. Height 105 cm, width 160 cm.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 164.

|

Regilla also dedicated a statue in the sanctuary of the health goddess Hygieia (see Asklepios) in the Altis at Olympia. The surviving marble statue base is inscribed simply:

Ῥήγιλλα Ὑγείαι

Regilla to Hygieia

Inscription IvO 288. |

|

| |

A row of marble statues, now nearly all headless,

from the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. |

| |

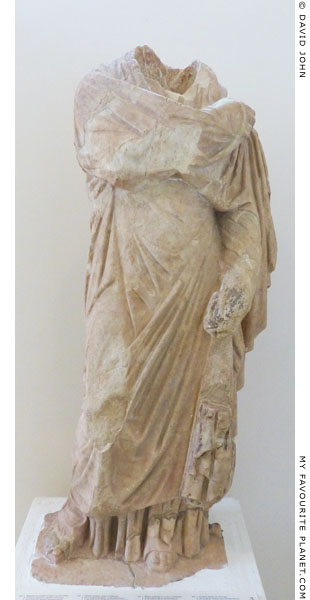

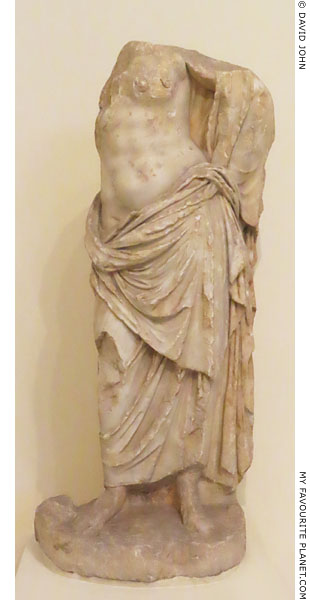

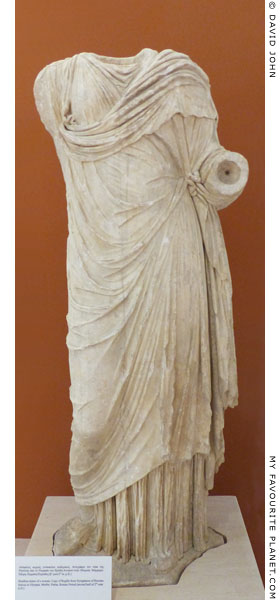

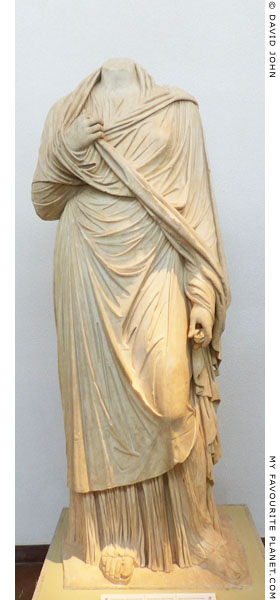

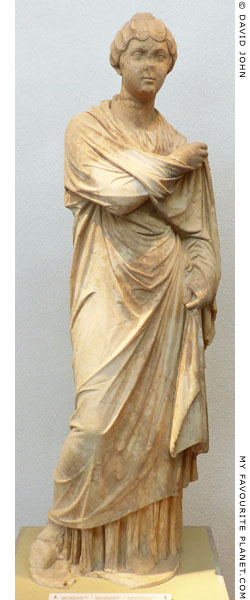

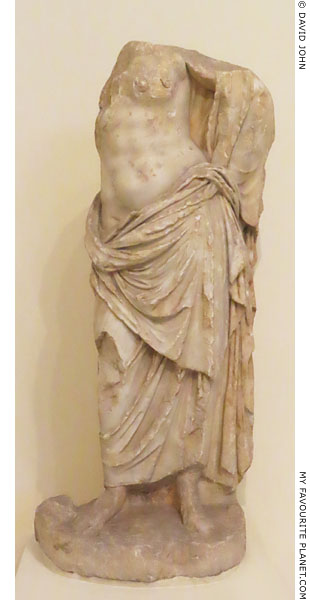

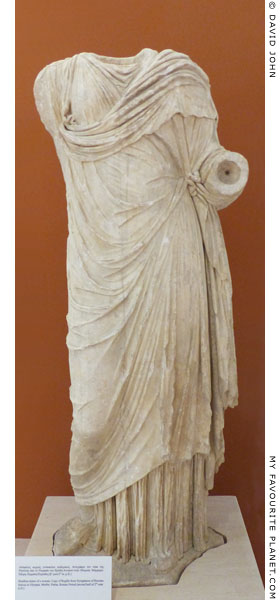

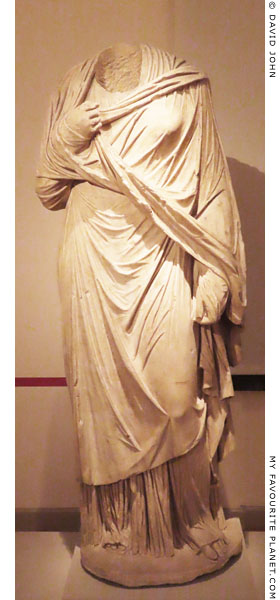

Marble statue of the "Large Herculaneum

Woman" type, now headless, thought

to depict Aspasia Annia Regilla.

From the Nymphaeum in Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD. Height 183 cm.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 156. |

|

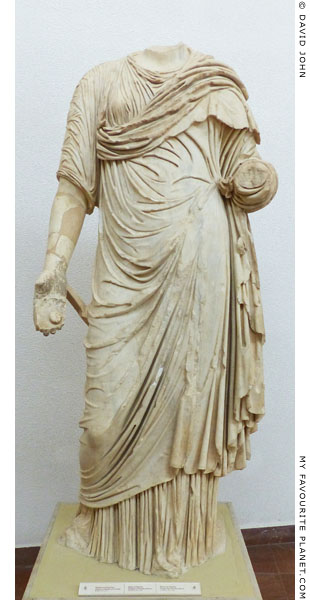

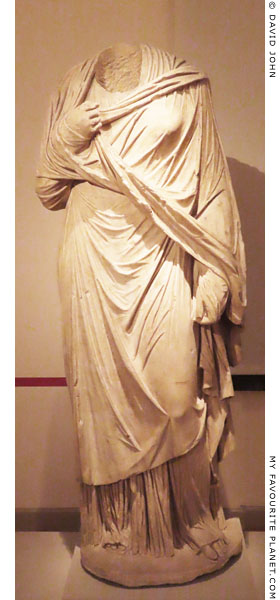

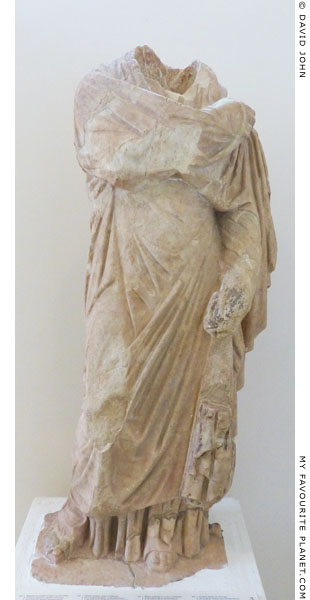

Headless marble statue of the "Large

Herculaneum Woman" type, believed

to depict an empress, perhaps Sabina,

wife of Emperor Hadrian.

From the Nymphaeum in Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD. Height 180 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1398.

Acquired in 1889 from the

excavations at Olympia.

|

The two statue bodies are remarkably similar, even to the individual folds on the garments.

See also two statue bodies from Patras below.

Another similar, unrelated headless statue in Olympia, found in the pronaos of the Heraion

and dated 2nd half of the 1st century AD, is thought to depict a distinguished Eleian woman.

Inv. No. Λ 139 (currently exhibited in the Museum of the History of the Ancient Olympic Games). |

|

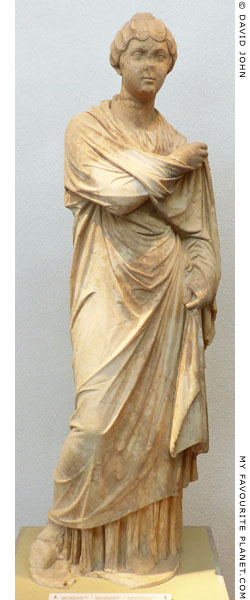

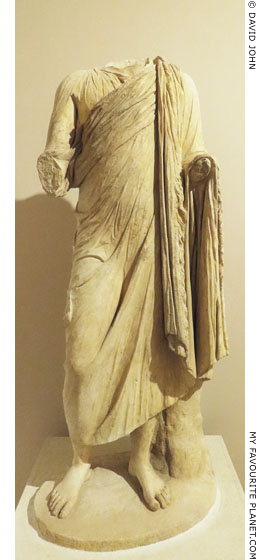

| |

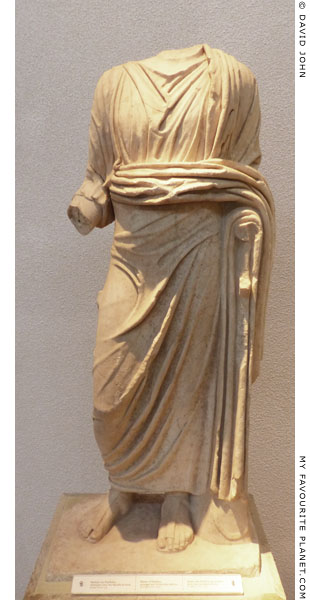

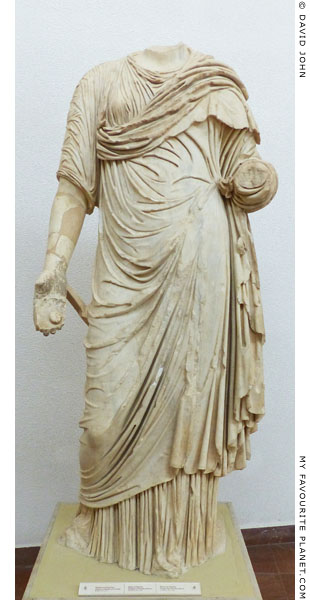

Marble statue of the "Small Herculaneum

Woman" type, thought to depict Athenais,

third child and second daughter of

Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla.

From the Nymphaeum in Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD. Height 180 cm.

The features of the portrait head are

those of an adolescent, although it has

been estimated that Athinais may have

been around ten years old at the time

the Nymphaeum was completed.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 159. |

|

Headless "Small Herculaneum Woman" type

marble statue, thought to depict Athenais,

the second daughter of Herodes Atticus

and Annia Regilla.

Found in the Altis, Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 161.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympia. |

|

| |

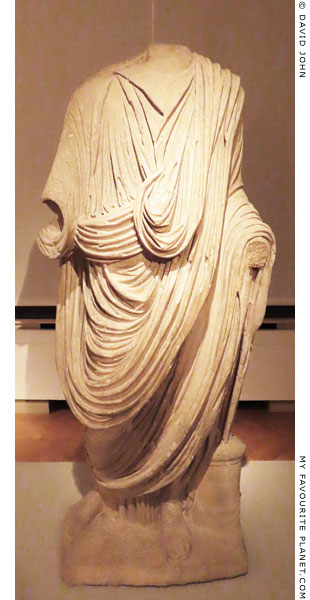

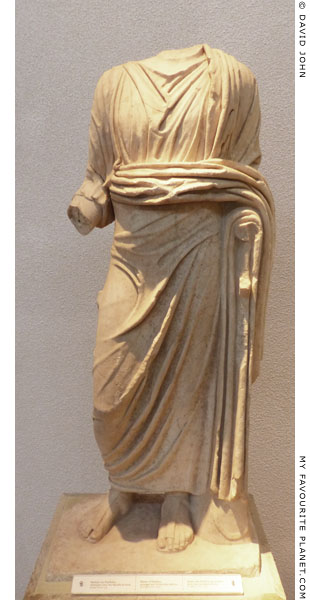

Headless marble statue of a woman,

believed to depict Elpinike, second child

and first daughter of Herodes Atticus

and Annia Regilla. The figure holds a phiale

(libation bowl) in her lowered right hand.

From the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus,

Olympia. Mid 2nd century AD.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. |

|

Headless marble statue of a yound male

in a toga, believed to depict Regillus, fifth

chlid and third son of Herodes Atticus

and Annia Regilla.

From the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus,

Olympia. Mid 2nd century AD.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

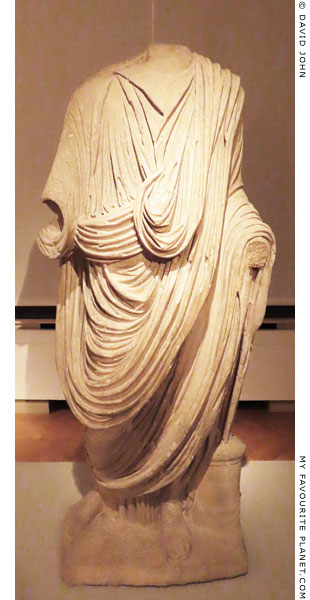

Headless marble statue of a man in a toga,

believed to depict Herodes Atticus.

From the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus,

Olympia. Mid 2nd century AD.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1399.

Acquired in 1889 from the

excavations at Olympia. |

|

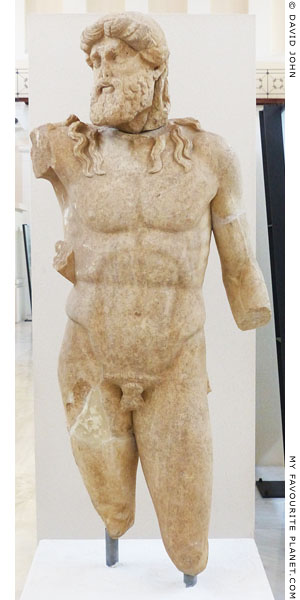

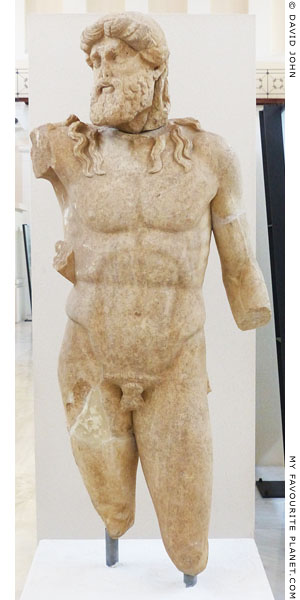

Marble statue of a nude Zeus from the

Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus, Olympia.

Mid 2nd century AD. Thought to by a copy

of a work by Myron, around 460 BC.

Pentelic marble. Height 167 cm.

The torso, parts of the head and other

fragments were found over many years

at the Nymphaeum and various places

around Olympia, some built into later

walls of buildings. The fragments were

first reassembled in 1972.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 109.

(The torso was originally numbered

Λ 170 and the head Λ 109.)

Currently exhibited in the Museum

of the History of the Ancient Olympic

Games, Olympia.

The headless torso and several fragments

of the other statue of Zeus from the

Nymphaeum were found in 1878, built into

a wall between the Gymnasium and the

north gateway of the Altis. The god is

shown wearing a himation. Inv. No. Λ 108. |

|

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

The stadium of Olympia |

|

|

|

| |

The altar of Demeter Chamyne on the low hill north of the stadium of Olympia. 2nd century AD.

|

Built of white stone blocks reused from an equestrian monument, the altar has been dated to the 2nd century AD. It has been suggested that it may have been set up for Regilla when she was priestess of Demeter in 153 AD, or even financed by her.

According to Pausanias, the epiphet of Demeter in the ancient Peloponnesian district of Elis (Ἦλις) was Chamyne (Χαμύνη), and there was a sanctuary of the goddess on the low hill north of the Olympic stadium (race track). At the time of his visit to Olympia, around 155 AD, new Pentelic marble statues of Demeter and Persephone (the Maid) in the sanctuary had been donated by Herodes Atticus.

In 2006 the remains of what are thought to be the sanctuary of Demeter Chamyne were discovered by chance during the digging of a water supply project, around 150 metres northeast of the stadium. They include a large building, dubbed Building A, built of local limestone, oriented east-west and divided into four rooms. Dated to the early 5th century BC, it is thought to have served a cult function, and in one of the rooms was a stone feature, perhaps an altar, surrounded by votive objects.

Objects discovered during the ensuing archaeological excavations of 2007 and 2008 include 34 bronze coins of the 5th - 4th century BC, several terracotta figures, most depicting human female subjects, but also animals, particularly bovines and goats, as well as silens and masks. One depicts a two-headed Kerberos with sacrificial cakes in its mouth, and another Kerberos figure is inscribed [Δά]ματρι, Κόρ[αι], [Βα]σιλεῖ, dedicated to Demeter, Persephone (Kore) and Plouton (Basileus, king of Hades). Part of a Roman period baths was also discovered on the site.

The office of cult priestess of Demeter Chamyne, appointed or "bestowed" (awarded) by the Elians "from time to time", which indicates that it was an honorary and temporary position for the duration of an Olympiad. She was the only woman allowed to attend the Olympic Games, and watched the competitions while seated on the altar of Demeter Chamyne, halfway along the length of the race course, directly opposite the stand of the competition judges (Ἑλλανοδίκαι, Hellanodikai). "Maidens" (παρθένοι, parthenoi, virgins), girls or unmarried young women, were admitted to Olympia, and there were also games for girls, a series of foot races known as the Heraia (Ἡραῖα, in honour of Hera; Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 16, sections 2-8).

"Now the stadium is an embankment of earth, and on it is a seat for the presidents of the games. Opposite the umpires is an altar of white marble. Seated on this altar a woman looks on at the Olympic games, the priestess of Demeter Chamyne, which office the Eleans bestow from time to time on different women. Maidens are not debarred from looking on at the games."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 20, sections 8-9.

"The other side of the course is not a bank of earth but a low hill. At the foot of the hill has been built a sanctuary to Demeter surnamed Chamyne. Some are of the opinion that the name is old, signifying that here the earth gaped for the chariot of Hades and then closed up once more. Others say that Chamynus was a man of Pisa who opposed Pantaleon, the son of Omphalion and despot at Pisa, when he plotted to revolt from Elis; Pantaleon, they say, put him to death, and from his property was built the sanctuary to Demeter.

In place of the old images of the Maid and of Demeter new ones of Pentelic marble were dedicated by Herodes the Athenian."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 21, sections 1-2.

Pausanias also tells us that only one woman was known to have illegally entered Olympia during the games (see the Pausanias page). |

|

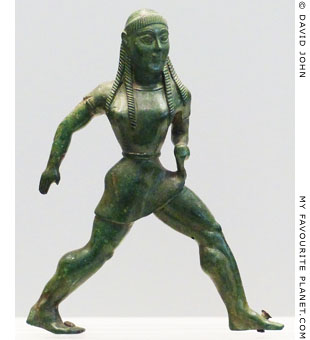

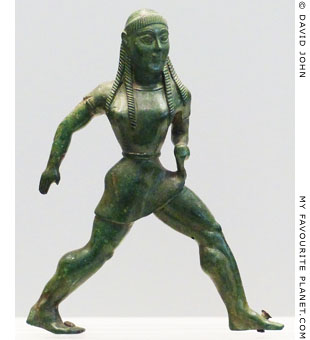

A bronze figurine of a running girl,

thought to be a Spartan female

athlete taking part in the maiden's

races (Heraia) held at Olympia.

From the decoration of a krater (mixing

vase) or cauldron. Made in a Laconian

workshop, 550-540 BC.

Found in 1875 in the Sanctuary of Zeus

at Dodona, northwestern Greece, during

excavations by Konstantinos Karapanos

(see note in Homer part 3).

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. Καρ. 24. From the

Konstantinos Karapanos Collection. |

|

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

The estates of Herodes and Annia Regilla at Marathon |

|

|

|

| |

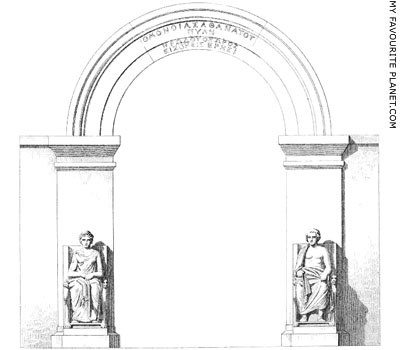

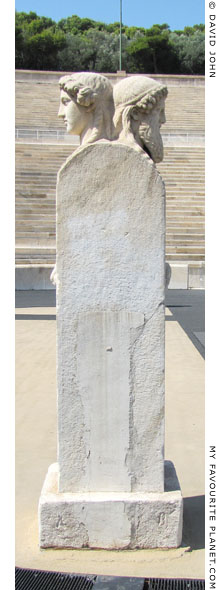

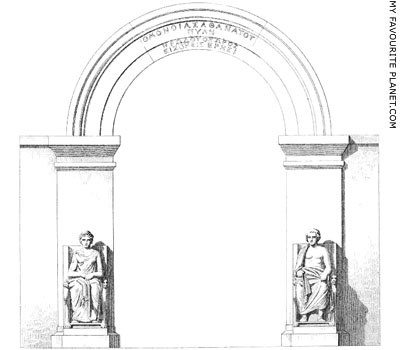

Remains of the monumental arched "Gateway of Immortal Harmony" from the

estates of Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla at Marathon, East Attica, Greece.

The keystone of an arch between two marble statues of enthroned figures:

left, Annia Regilla (Inv. No. 159); right Herodes Atticus (Inv. No. 158).

Mid 2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Herodes Atticus owned extensive areas of land at several locations around Greece, including Astros in Arcadia, Kifissia, and particularly at his ancestoral deme of Marthon, East Attica. The remains of his country estate are around 3 kilometres west of Marathon, just south of Oinoe, the location of the ancient Cave of Pan. He gave part of this property to his wife Annia Regilla, an area containing various buildings and other structures enclosed by a 3,300 metre long perimeter wall of rubble masonry, known today as Mandra tis Grias (Μάντρα της Γριάς), the Old Woman's Sheepfold. After her death this probably became his residence in the area.

The entrance to the estate was a monumental arched gateway, with inscriptions on both sides of the arch. Although several parts and fragments of the gateway have been found, only the three pieces shown above are currently exhibited in the Marathon Museum.

One side of the archway's keystone was inscribed:

Ὁμονοίας ἀθανάτ[ου].

πύλη.

Ἡρώδου ὁ χῶρος

εἰς ὃν εἰσέρχε[ι].

Gateway of Immortal Harmony. The place you enter belongs to Herodes.

Inscription IG II² 5189 (also C.I.G. 537).

The insciption on the other side was identical, except for the name of the owner:

Ὁμονοίας ἀθανάτου.

πύλη.

Ῥηγίλλης ὁ χῶρος

εἰς ὃν εἰσέρχει.

Gateway of Immortal Harmony. The place you enter belongs to Regilla. (see photo below)

Inscription IG II² 5189a.

In front of each of the pillars supporting the arch and acting as jambs for the gate was a statue of an enthroned figure (there is said to have originally been three statues). Though now badly worn and damaged, the two are thought to have been portraits of Herodes and Annia Regilla (Inv. Nos. 158 and 159 respectively) On the right hand pillar, above the statue, is an epigram of three couplets, the first referring to the couple:

"O happy is he who built a new city, naming it after Regilla; his life is full of joy."

The other two couplets beneath this are thought to have been inscribed later, as Herodes' reply to the early euphoria, following the death of his wife and most of his children:

"My life is full of sorrow as I contemplate my existence without my beloved wife, and my house that has remained without heir.

Truly, when the gods mix the mortal cup of life they put in joys and sorrows mingled."

See: Daniel J. Geagan, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 79, 1964, pages 149-156. S.E.G., XXIII, No. 121.

The English traveller Doctor Richard Chandler (1738-1810) wrote the first modern report concerning the gateway and an explanation of the name "the Old Woman's Sheepfold". He visited Marathon in May 1776, accompanied by some local people, who told him of the local folktale which had grown around the ruined gate and the single statue then still visible. He noted the tale, but later regretted not having inspected the ruins more closely.

"In the vale, which we entered, near the vestiges of a small building, probably a sepulchre. was a headless statue of a woman sedent, lying on the ground. This, my companions informed me, was once endued with life, being an aged lady possessed of a numerous flock, which was folded near that spot. Her riches were great, and her prosperity was uninterrupted. She was elated by her good fortune. The winter was gone by, and even the rude month of March had spared her sheep and goats. She now defied Heaven, as unapprehensive for the future, and as secure from all mishap. But Providence, to correct her impiety and ingratitude, commanded a fierce and penetrating frost to be its avenging minister; and she, her fold, and flocks were hardened into stone. This story, which is current, was also related to me at Athens. ... I regretted afterwards my inattention to it on the spot; for I was assured that the rocky crags afford at a certain point of view the similitude of sheep and goats within an enclosure or fold."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, chapter 36, pages 166-167. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

It has been suggested that the local name of the walled area may be much older than the folktale, since the Greek word mandra can mean any enclosed space, not necessarily connected with livestock. The idea of "the rocky crags" resembling sheep and goats in the mind's eye of local people is widespread throughout history. Compare this, for example, with Pausanias' description of the nearby Cave of Pan, or even Osbert Lancaster's reaction to the rocks of Meteora.

In 1892 Louis-François-Sebastien Fauvel (1753-1838), the French painter, diplomat and archaeologist who was very active digging up and taking away ancient artefacts in the area of Marathon over a number of years, recorded the inscription on the arch referring to Herodes Atticus, so that at the latest by then it was evident that the fallen stones were the remains of a gateway. Over the next two centuries the remains were visited and inspected by a number of scholars, and one, Philippe Le Bas even brought with him an artist with whom he attempted to restore the original appearance of the gate in 1843-1844 (see image, right). However, remarkably it was not until 1926 that the Greek archaeologist George Sotiriadis came along and turned the keystone over to find the inscription on the other side. The pillar with the epigram was found by Daniel J. Geagan during excavation work in 1964, when Alfred Mallwitz reexamined the remains and made a new restoration of the portal.

See: George Sotiriadis, The New Discoveries at Marathon. In: The Classical Weekly, Volume 20, No. 11 (January 10, 1927), pages 83-84. At jstor.org.

As has often been pointed out, the inscriptions on the gateway's arch appear to be in imitation of those on Hadrian's Gate (also known as Hadrian's Arch) in Athens, built by the Athenians in honour of Emperor Hadrian, probably in 131/132 AD. He built the Olympieion (Temple of Olympian Zeus) and a new quarter of Athens, beyond the ancient confines of the city around the Acropolis. His new quarter spread over an area between the southeast of the Acropolis and the Ilissos River, on the other side of which, around a decade later, Herodes Atticus built the new Panathenaic Stadium. The gate, built of Pentelic marble in the form of a Roman triumphal arch of the Corinthian order, 18 metres high and 13.5 metres wide, marked the boundary between the old and the new parts of the city. Inscriptions placed above the arch on either side of the gatweway made it clear in which part of town readers found themselves.

On the northwest side, facing the Acropolis and the old town, was inscribed:

αἵδ’ εἴσ’ Ἀθῆναι Θησέως ἡ πρὶν πόλις.

This is the Athens of Theseus, the old city.

On the southeast side of the gate, facing Hadrian's new quarter:

αἵδ’ εἴσ’ Ἁδριανοῦ καὶ οὐχὶ Θησέως πόλις.

This is the city of Hadrian and not of Theseus.

Inscription IG II² 5185.

Many Athenians will have been aware of the legendary or mythical pillar set up on the Isthmus at Corinth, mentioned by Strabo (circa 64-24 AD) and Plutarch (circa 46-120 AD), similarly marking the border between the Ionian Greek mainland of central Greece and the peninsula of the Peloponnese.

"Besides, the Peloponnesians and Ionians having had frequent disputes respecting their boundaries, on which Crommyonia also was situated, assembled and agreed upon a spot of the Isthmus itself, on which they erected a pillar having an inscription on the part towards Peloponnesus:

'This is Peloponnesus, not Ionia';

And on the side towards Megara:

'This is not Peloponnesus, but Ionia'."

Strabo, Geography, Book 9, chapter 1, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

The repective inscriptions in Greek:

On the Peloponnesian (west) side of the pillar: "τάδ᾽ ἐστὶ Πελοπόννησος οὐκ Ἰωνία."

On the Ionian (east) side of the pillar: "τάδ᾽ οὐχὶ Πελοπόννησος ἀλλ᾽ Ἰωνία."

He repeated the anecdote in Geography, Book 3, chapter 5, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

In Plutarch's version of the story, it was the legendary king of Athens and Minotaur-slayer, Theseus himself who set up the boundary pillar:

"Having attached the territory of Megara securely to Attica, he set up that famous pillar on the Isthmus, and carved upon it the inscription giving the territorial boundaries. It consisted of two trimeters, of which the one towards the east declared:

'Here is not Peloponnesus, but Ionia';

and the one towards the west:

'Here is the Peloponnesus, not Ionia'."

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, Theseus, chapter 25, section 3. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

In the case of the Mandra tis Grias gateway, it is not known which inscription faced the outside of the enclosure and which the inside, and apparently there is no physical or technical evidence to indicate the solution. It has been argued, citing the examples of Hadrian's Gate and the Isthmus pillar as evidence of "ancient practice", that the Regilla text must have been on her side of the gate, that is inside the enclosure, and the Herodes text on his side. However, neither of the texts state "This belongs to..." Regilla or Herodes; both inform the reader that they are entering the property of the respective owner, which suggests that the Regilla text must have been on the outside, and that of Herodes on the inside.

See: Eugene Vanderpool, Some Attic inscriptions: Regilla's estate at Marathon. In: Hesperia 39, 1970, pages 43-45, plate 14a. |

An early reconstruction drawing of the "Gateway of

Immortal Harmony", Marathon by Philippe Le Bas.

Salomon Reinach, Voyage archelologique en Grece et

en Asie Mineure sous la direction de M. Philippe Le Bas

(1842-1844), plate 90. Paris, 1888. |

| |

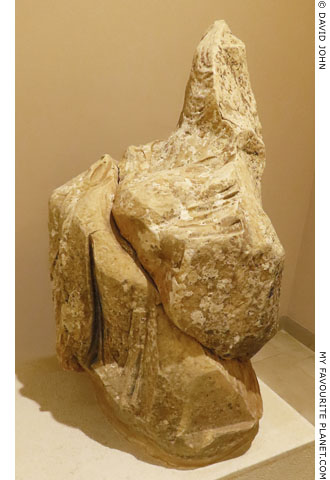

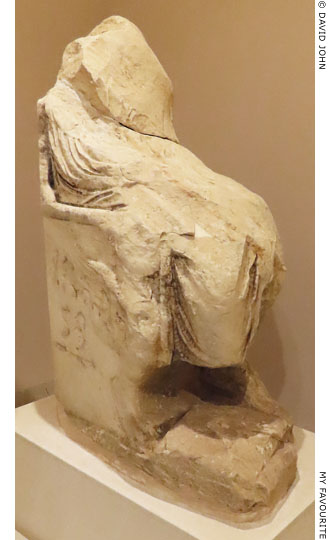

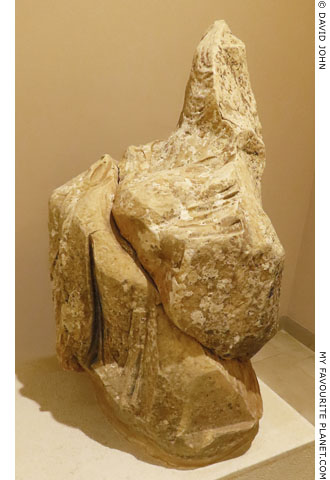

The reassembled fragments of the statue

of Annia Regilla from the "Gateway of

Immortal Harmony" near Marathon.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 159. |

| |

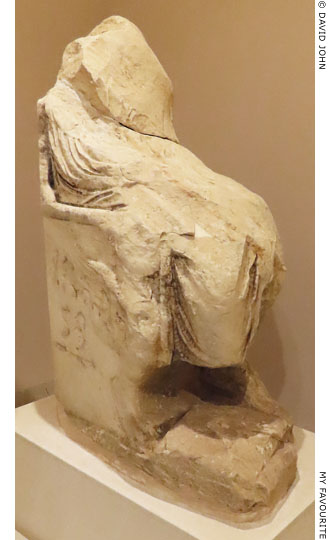

The reassembled fragments of the statue

of Herodes Atticus from the "Gateway of

Immortal Harmony" near Marathon.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 158. |

| |

The southeast side of Hadrian's Gate, Athens,

built around 131/132 AD. The southeast corner

of the Acropolis can be seen through the arch.

The inscription "This is the city of Hadrian and

not of Theseus", still visible on the architrave,

is difficult to read, as much of it is blackened

by age and environmental pollution. |

| |

| |

Fragments of the keystone from the arched gateway to the Marathon

estate Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla. On this side is the inscription:

Ὁμονοίας ἀθανάτου.

πύλη.

Ῥηγίλλης ὁ χῶρος

εἰς ὃν εἰσέρχει.

"Gateway of Immortal Harmony. The place you enter belongs to Regilla." |

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

The Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza |

|

|

|

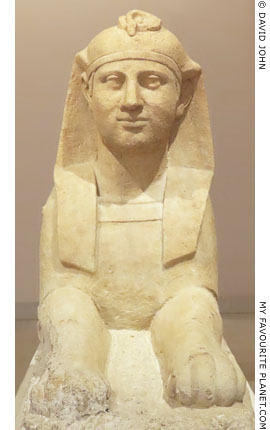

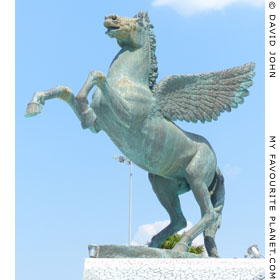

Copies of statues set up in the archaeological site of the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods

at Brexiza (Αιγυπτιακό ιερό στην Μπρεξίζα), built by Herodes Atticus around 160 AD on a

man-made islet in the Mikro Elos (Μίκρο Ἐλος, Small Marsh), southeast of Marathon, Attica. |

| |

Some of the sculptures from the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods

at Brexiza now in the Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The plain of Marathon in northeast coast of the Attic peninsula, lies along the Bay of Marathon, opposite the island of Euboea. To the west, a range of low mountains, including Mount Pendeli (source of Pentelic marble) separates the plain from Athens and west Attica. The modern small town (or large village) of Marathon itself is a the north of the plain, a little inland. At the southern edge of the plain is the modern settlement of Nea Makri. In antiquity the area was a fertile and wealthy deme of Athens. Today it is a seaside resort popular with Athenians at weekends and vactions, and many have a holiday home there.

Around 2 kilometres north of Nea Makri, near the beach where the Battle of Marathon was fought between Greek and invading Persians in 490 BC, is the famous Soros (Σορός) or Tomb of the Athenians, the large funeral mound constructed for the 190 Athenian soldiers who died in the battle.

At Brexiza, just to the south of the Soros, was a marsh known as Mikro Elos (Μίκρο Ἐλος, Small Marsh), which was drained in the mid 20th century. The Egyptian sanctuary was built on an artificial island on this marshland by Herodes Atticus, probably around 160 AD. The building complex included a temple and adjoining courtyard, a large elliptical pool and a bath installation known as a balneum. It is the largest known Egyptian sanctuary in Greece.

Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel (1753-1838), the French painter, diplomat and archaeologist, who conducted excavations around Marathon in the late 18th century (see above), was the first person in modern times to record the location of the sanctuary. He discovered the site by chance in 1789 when he visited the area in order to investigate the tombs from the Battle of Marathon. During his subsequent excavations of the ruins he found three portrait busts, which were sent to France. The busts of Herodes Atticus and Emperor Marcus Aurelius are now in the Louvre Museum, while a bust of Emperor Lucius Verus eventually ended up in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford [see note 7].

More recently, small excavations were undertaken in 1926 and 1968. Systematic excavation of the sanctuary began in 2001 and continued for several years. It was during these latter digs that most of the artifacts now in the Marathon museum were found.

According to Philostratos and the inscriptions found during the recent excavations, the sanctuary was named Canopus (Κάνωπος, Kanopos, or Κάνωβος, Kanobos) [17], after the Egyptian island at the west of the Nile Delta, near Aboukir and 25 kilometres east of Alexandria. King Ptolemy III Euergetes is said to have founded the Sarapeion of Canopus, which became famous as a place of pilgrimage and healing centre. It is thus thought that the Brexiza sanctuary may also have been dedicated to Serapis. Emperor Hadrian also built a sanctuary of Canopus in the grounds of his villa at Tivoli near Rome (see Antinous), which Herodes Atticus may have been attempting to emulate. He had a drainage ditch dug around the sanctuary to create an artificial island, in imitation of the Egyptian original.

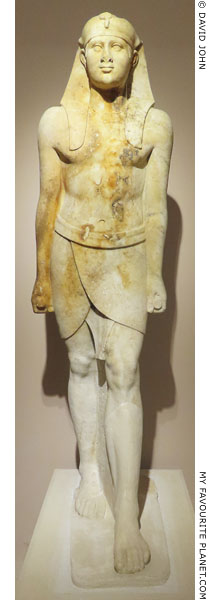

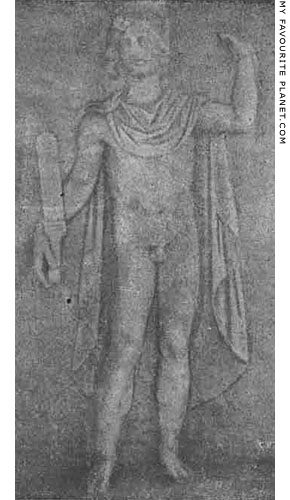

The Sanctuary was surrounded by an almost square peribolos (περίβολος, perimeter wall) within which was a temple with four entrances in the form of Egyptian pylons, one at each of the cardinal points of the compass. Each entranceway was flanked by a statue of Isis and one of Antinous as Osiris. Three of the Antinous statues have so far been found. The first was discovered in 1843 and is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The other two are in the Marathon Archaeological Museum (see photos, right and below). Three of the Isis statues have also been recovered (see below), one depicting her as Isis-Aphrodite and the other as Isis-Demeter. Of the third only a fragment, the feet and legs below the knees, has survived.

All the surviving statues from the entrances are made of Pentelic marble and are joined at the back to one the pillars that framed the entrance. The backs of the statues were evidently not meant to be seen as they are more roughly finished. They are all depicted in the same hieratic pose, characteristic of ancient Egyptian statues: they stand stiffly erect with their hands at their sides, with the left leg placed forewards, as if they are stepping towards the viewer.

A third statue of Isis, also in a hieratic pose, but sculpted in more detail (see below) was found in a room of the sanctuary dubbed by archaeologists "the Room of the Lamps" after the around 70 large ritual lamps found there. A marble sphinx was also discovered here (see below). It is thought that the artifacts were brought here from their original places for protection.

To the east of the temple was a rectangular courtyard with a stoa (colonnade) running around three of its four sides. |

|

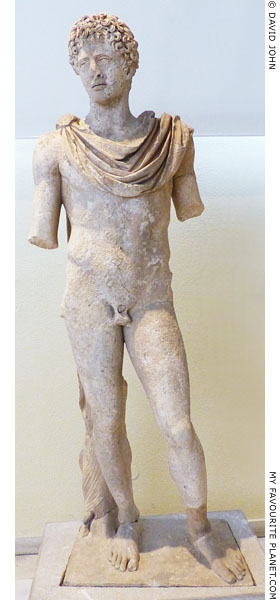

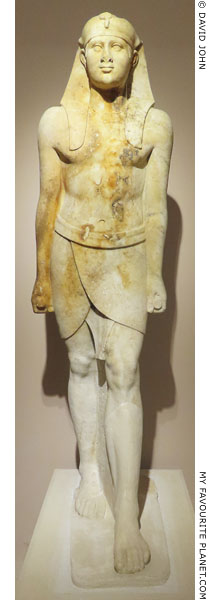

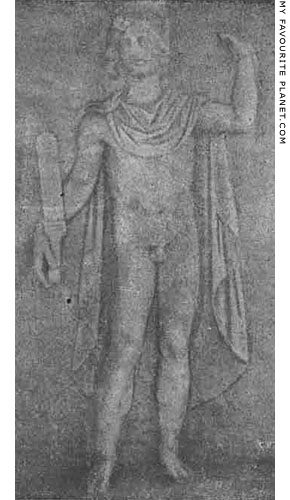

Larger than lifesize marble

statue of Antinous as the

Egyptian god Osiris, from

one of the entrances to the

temple in the Sanctuary of

the Egyptian Gods, Brexiza.

Marble, 2nd century AD.

Found in 1843 at Marathon.

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens. Egyptian

Collection. Inv. No. 1. |

|

Larger than lifesize marble

statue of Antinous-Osiris,

from the west porch of the

Egyptian temple, Brexiza.

2nd century AD. Found in

1968. Height 240 cm.

Marathon Archaeological

Museum. Inv. No. 1. |

|

| |

Larger than lifesize marble

statue of Antinous-Osiris

from the north porch of

the Egyptian sanctuary,

Brexiza. The figure wears

the double crown of Upper

and Lower Egypt in the

form of a tall polos.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological

Museum. |

|

A larger than lifesize marble

statue of Isis-Aphrodite

from the west porch. In

each hand she holds three

dog roses, considered the

flower of Aphrodite. Like

the Antinous-Osiris statue

from the north porch

(photo, left) she wears

a tall polos.

2nd century AD. Pentelic

marble. Height 239 cm. Marathon Archaeological

Museum. |

|

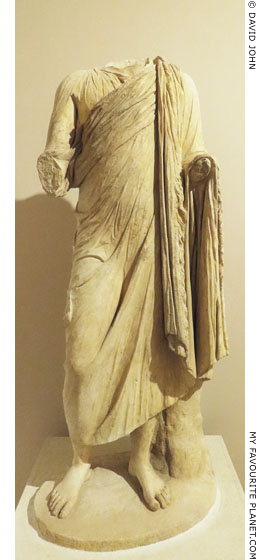

Larger than lifesize marble

statue of Isis-Demeter from

the south porch. She wears

a basileion, a solar disk with

three feathers between the

horns, and above the fore-

head it is decorated with a

uraeus with a twisted tail.

She holds ears of wheat in

her right hand, but most of

the left hand is now missing.

2nd century AD. Pentelic

marble. Height 231 cm.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

Larger than lifesize marble

statue of Isis, found in the

"room of the lamps".

This statue is sculpted in

greater detail and is dressed

quite differently. Her headwear

includes a uraeus with a twisted

tail, though part of the head is

now missing. She wears a long

chiton with short sleeves, over

which is a fringed himation,

tied between her breasts with

the Isiac knot. With her left

hand she holds out the end of

the himation in a way unknown

from any other statue of Isis.

In her lowered right hand she

holds a folded ribbon, the ends

of which fall to either side of her

hand. Such ribbons, symbols of

strength and eternal life, are

usually held by male figures.

2nd century AD. Pentelic

marble. Height 183 cm.

Marathon Archaeological

Museum. |

|

| |

Larger than lifesize marble statue

of Horus as a falcon wearing the

crown of Upper Egypt. From the

Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

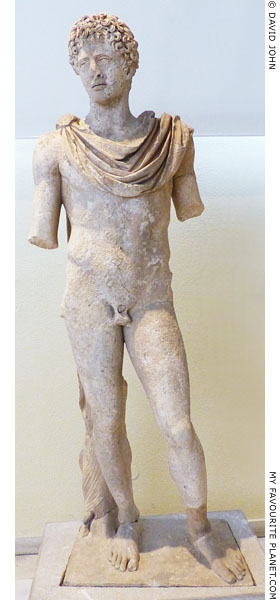

Headless marble statue of a young

man, probably an orator, wearing

a himation (woollen mantle) over a

chiton (tunic). From the Sanctuary

of the Egyptian Gods.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

Marble head of Empress Faustina the

Younger, wife of Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Found in the vicinity of the Tumulus of the

Athenians, but thought to have originally

been set up by Herodes Atticus in the

Egyptian sanctuary.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 16. |

|

| |

|

|

|

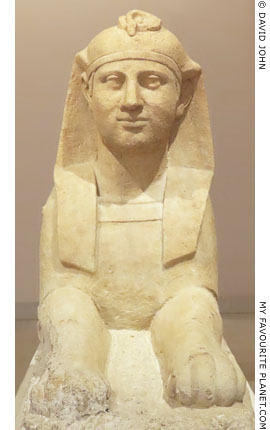

A marble statue of a Sphinx found in the "Room of the Lamps"

in the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Herodes

Atticus |

Polydeukes |

|

|

|

| |

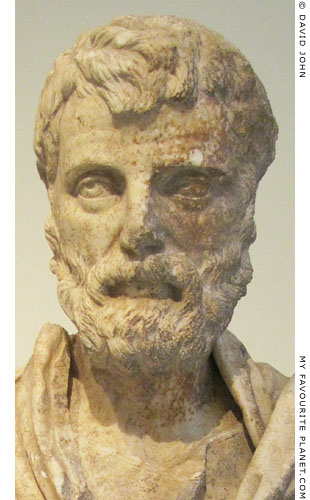

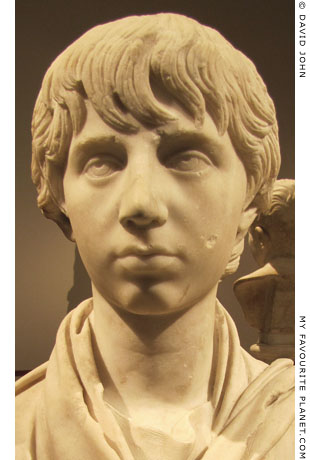

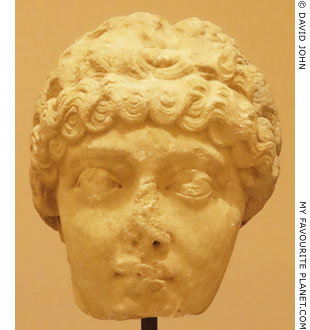

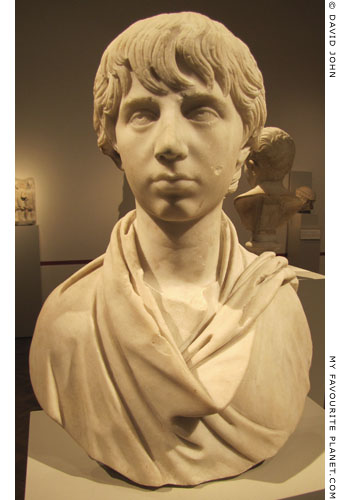

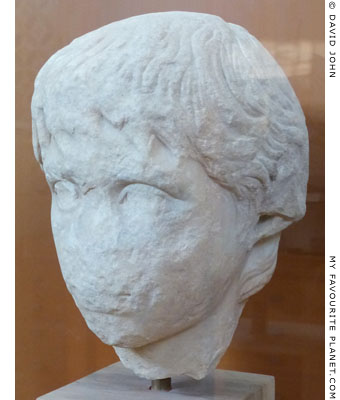

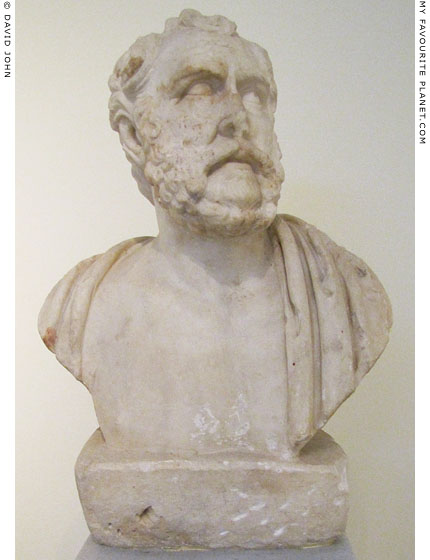

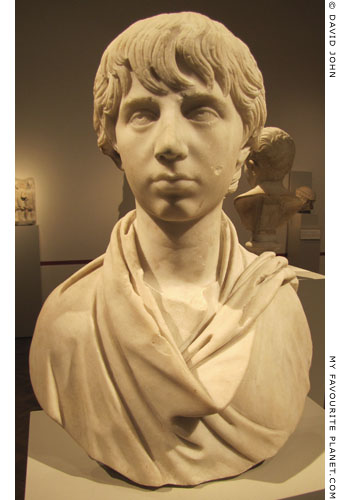

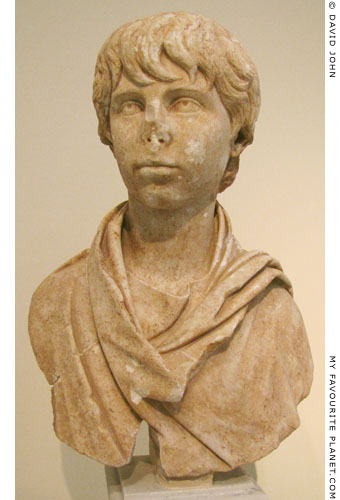

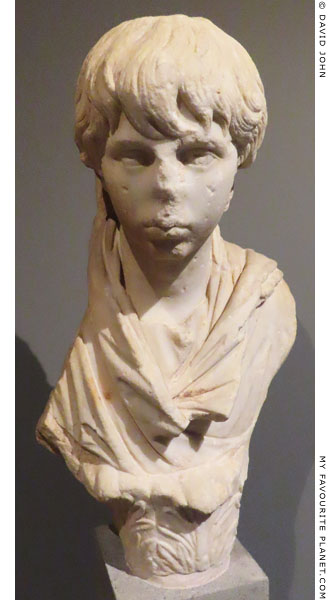

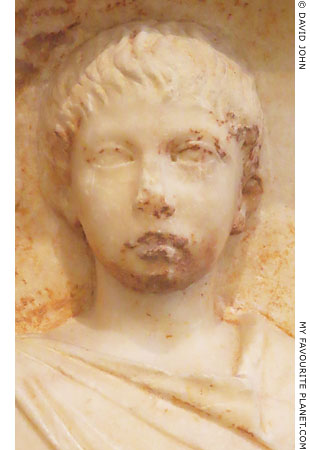

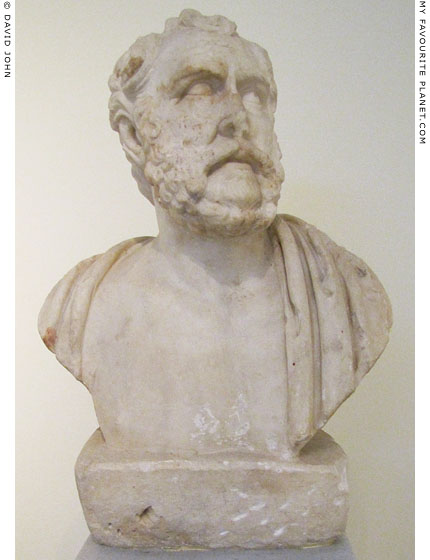

Marble bust of Polydeukes.

Mid 2nd century AD. Purchased in Athens

in 1844, probably by Ludwig Ross.

Height 54.5 cm, width 40 cm, depth 24 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 413. |

|

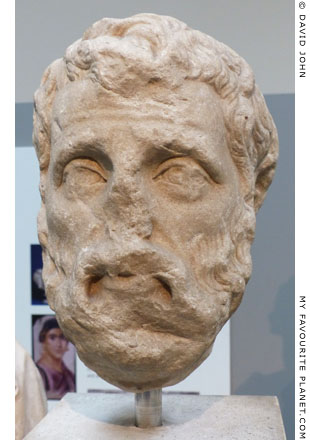

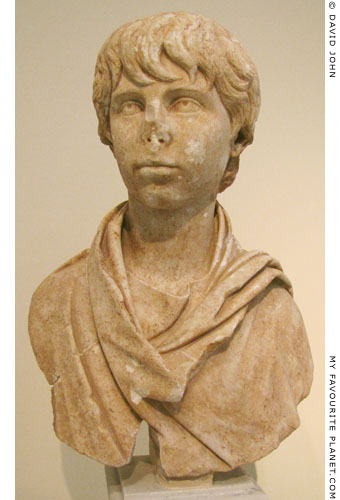

Bust of Polydeukes from Herodes Atticus'

villa in Kifissia (Κηφισιά), Attica.

Mid 2nd century AD. Found in Rangavi Street,

Kifissia in February 1961, together with the

bust of Herodus Atticus at the top of the page.

Parian marble. Height 56 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4811. |

|

| |

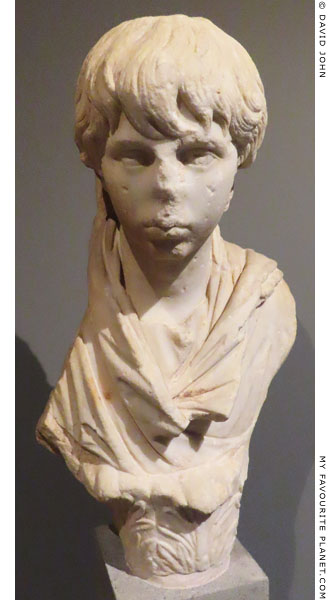

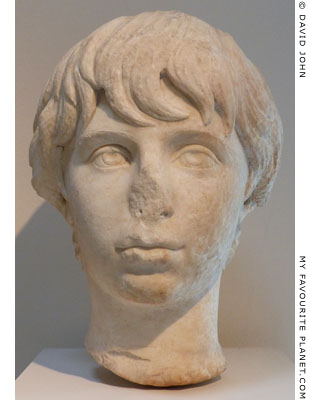

There are twelve portraits of Polydeukes in various Athens museums, including two portrait heads found on the South Slope of the Athens Acropolis:

Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. 2377.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 3468. Height 28.8 cm.

They are not in such a good condition as those above, and are not usually on display.

This foster son of Herodes Atticus is named in inscriptions as Vibullius Polydeukion (Βιβούλλιος Πολυδευκίων), but Philostratus and Lucian [18] refer to him as Polydeukes (Πολυδεύκης, much sweet wine), perhaps a diminutive or nickname and an allusion to Polydeukes (Latin, Pollux), one of the Dioskouroi. Some scholars believe that the nomen Vibullius indicates that he may have been a blood relative of Herodes. There are around thirty four known ancient portraits of the youth who was first recognized as Polydeukes by the German archaeologist Karl Anton Neugebauer in 1931, when only eight ancient examples were known [19].

The statues and monuments for Polydeukes and those of Herodes Atticus' two other adopted sons Memnon and Achilles are thought to have been set up after they died at a young age. It is not known when each of them died, how old they were, or even when Herodes adopted them, although various dates have been suggested [see note 8]. Some museum labelling and literature date the portraits of Polydeukes to around 140-150 AD, but this is probably far too early.

Philostratus reported on Herodes Atticus' grief on the death of two of his daughters, Athenais (he calls her Panathenais, Παναθηναίδι) and Elpinice (Elpinike), on his relationship with his son Atticus (Atticus Bradua) and the statues he set up of his three adopted sons.

"Thus, then, his grief for Regilla was quenched, while his grief for his daughter Panathenais was mitigated by the Athenians, who buried her in the city, and decreed that the day on which she died should be taken out of the year. But when his other daughter, whom he called Elpinice, died also, he lay on the floor, beating the earth and crying aloud: 'O my daughter, what offerings shall I consecrate to thee? What shall I bury with thee?' Then Sextus the philosopher who chanced to be present said: 'No small gift will you give your daughter if you control your grief for her.'

He mourned his daughters with this excessive grief because he was offended with his son Atticus. He had been misrepresented to him as foolish, bad at his letters, and of a dull memory. At any rate, when he could not master his alphabet, the idea occurred to Herodes to bring up with him twenty four boys of the same age named after the letters of the alphabet, so that he would be obliged to learn his letters at the same time as the names of the boys. He saw too that he was a drunkard and given to senseless amours, and hence in his lifetime he used to utter a prophecy over his own house, adapting a famous verse as follows:

'One fool methinks is still left in the wide house.' *

And when he died he handed over to him his mother's estate, but transferred his own patrimony to other heirs. The Athenians, however, thought this inhuman, and they did not take into consideration his foster sons Achilles, Polydeuces and Memnon, and that he mourned them as though they had been his own children, since they were highly honourable youths, noble-minded and fond of study, a credit to their upbringing in his house.

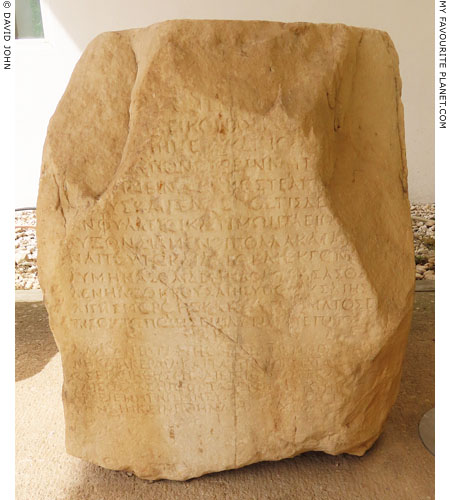

Accordingly he put up statues of them hunting, having hunted, and about to hunt, some in his shrubberies, others in the fields, others by springs or in the shade of plane trees, not hidden away, but inscribed with execrations on any one who should pull down or move them. Nor would he have exalted them thus, had he not known them to be worthy of his praises. And when the Quintilii during their proconsulship of Greece censured him for putting up the statues of these youths on the ground that they were an extravagance, he retorted: 'What business is it of yours if I amuse myself with my poor marbles?'"

* Paraphrase of Homer, The Odyssey, Book 4, line 498, with "house" substituted for "deep".

Philostratus, The lives of the Sophists, Book 2, sections 557-559 (pages 162-167,

see note 3). |

|

A marble high relief with a bust of Polydeukes

wearing a himation. The bust appears to have

grown from the cluster of acanthus leaves

which acts as a base. The broken flat back of

the relief suggests that it was part of a larger

monument, perhaps set in a wall.

Around 150 AD. From an unknown location

on the island of Euboea, central Greece.

New Archaeological Museum "Arethousa",

Chalkis. Inv. No. MX 2179.

Formerly in the Archaeological Museum of

Chalkis (now referred to as the "old museum"). |

|

| |

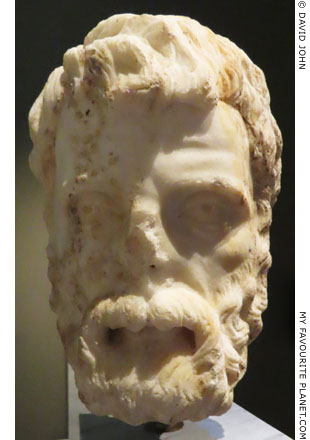

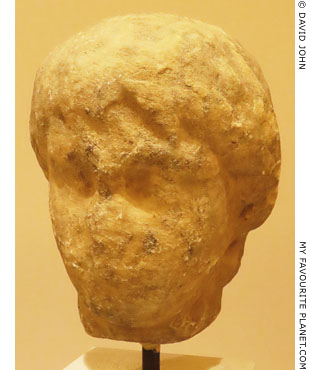

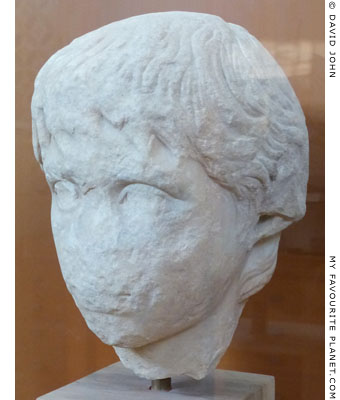

Lifesize marble portrait head of Polydeukes

from the Roman baths at Isthmia.

Mid 2nd century AD.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. IS 78-12.

Found in spring 1978 during excavations

directed by American archaeologist

P. A. Clement. One of two heads of

Polydeukes (the other Inv. No. IS 437,

not on display) found in the area of the

2nd century AD bath complex at Isthmia

(Ισθμία), 16 km east of Ancient Corinth.

It has been suggested that the baths,

which included a large mosaic floor with

depictions of Poseidon (the patron deity

of Isthmia) and Amphitrite, may have

been built by Herodes Atticus as

a dedication to Polydeukes.

Pausanias and Philostratus [see note 3]

mentioned that Herodes donated statues

to the Temple of Poseidon at Isthmia. [20] |

|

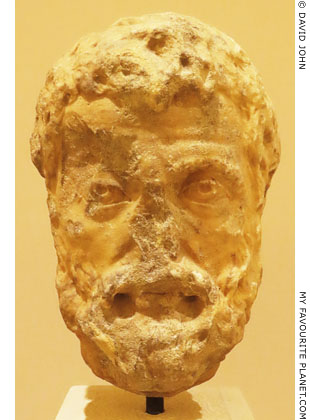

Marble portrait head of Polydeukes

from Corinth.

Mid 2nd century AD. Found 6 April 1964 at

Alonia Ayiannotika, east of the ampitheatre,

1.2 km northeast of Ancient Corinth. Perhaps

from the area of the Kraneion (see above).

It was stolen along with a large number of

antiquities during a violent burglary of the

museum on 12 April 1990. It was recovered

by police and returned to the museum on 25

January 2001. Height 28 cm, height of head

24 cm, width 22 cm, depth 21.5 cm.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. S 2734.

Herodes Atticus financed monumental

building projects at Corinth, including the

renovation of the Odeion and perhaps

the Peirene Fountain (see below). |

|

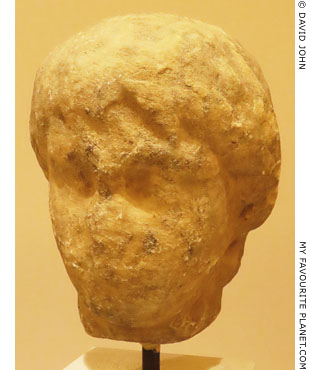

Marble portrait head of Polydeukes

from Marathon, Attica, Greece.

2nd century AD.

Found in 1955, along with a head

of Herodes Atticus (see above),

at Marathon, near the tumulus for

the 192 Athenians who died during

the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.

Marathon Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. BE 12.

Formerly in the National Archaeological

Museum, Athens, Inv. No. 934. |

|

| |

|

|

|

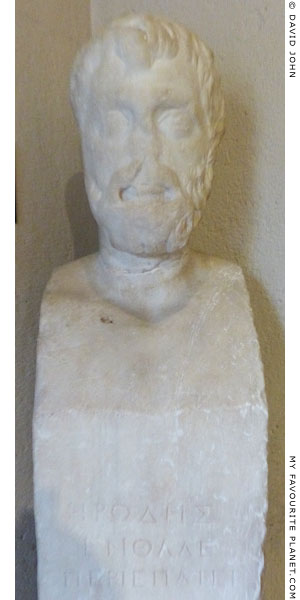

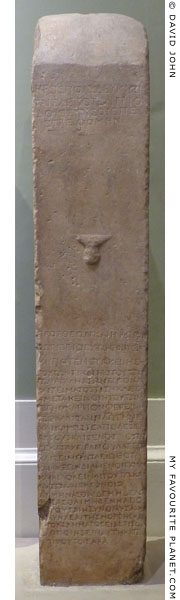

A headless herm with an inscription dedicated to the

"hero Polydeukion", probably by Herodes Atticus.

Mid 2nd century AD. Found in the ruins of a chapel in Kifissia, northeast of Athens,

where Herodes Atticus had a villa (see above). Pentelic marble. Height 155 cm.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. ANMichaelis 177.

Donated in 1759 by R. M. Dawkins.

|

|

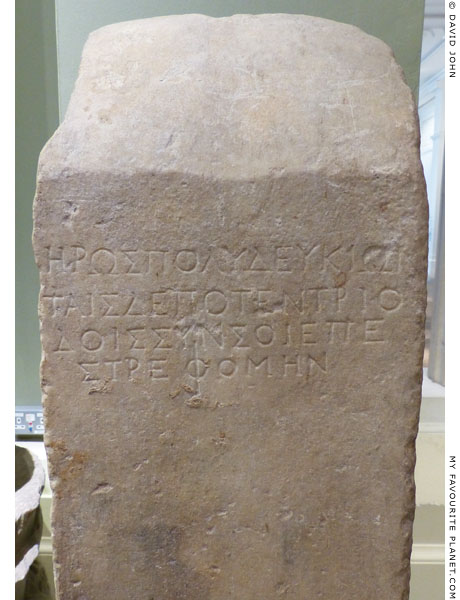

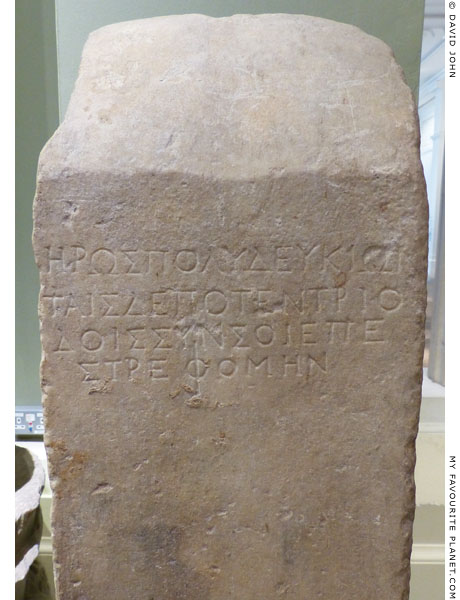

The Greek inscription on the chest of the herm shaft:

Ἥρως Πολυδευκίων

ταῖσδέ ποτ’ ἐν τριό-

δοις σύν σοι ἐπε-

στρεφόμην

Hero Polydeukion, once I walked here with you at this crossroads.

Inscription IG II² 13194.

The longer inscription at the bottom of the herm shaft includes a curse text: the threat of a curse on vandals and thieves, as with the statues "inscribed with execrations on any one who should pull down or move them" mentioned by Philostratus (see above), and the columns from the Triopion in Rome (see above).

For the Greek text of the longer inscription, see:

IG II² 13194 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

The English traveller Richard Chandler (1737-1810), who visited Kifissia on 5th May 1766 on his way from Athens to Marathon (see above), reported on the herm and Herodus Atticus' habit of placing protective inscriptions on memorial sculptures:

"We soon arrived at Cephisia, a village situated on an eminence by a stream near the western extremity of mount Pentele. It was once noted for plenty of clear water and for pleasant shade suited to mitigate the heat of summer. It has a mosque [the old Agia Paraskevi church, see above], and is still frequented, chiefly by Turks of Athens, who retire at that season to their houses in the country. The famous comic poet Menander was of this place.

Atticus Herodes, after his enemies accused him to the emperor Marcus Aurelius as guilty of oppression, resided here and at Marathon; the youth in general following him for the benefit of his instruction. Among his pupils was Pausanias of Caesarea, the author, it has been affirmed, of the description of Greece. *

Atticus Herodes had three favourites, whose loss he lamented, as if they had been his children. He placed statues of them in the dress of hunters, in the fields and woods, by the fountains, and beneath the plane-trees; adding execrations, if any person should ever presume to mutilate or remove them.

One of the hermae or Mercuries was found in a ruinous church at Cephisia, and is among the marbles given by Mr. Dawkins to the university of Oxford. This represented Pollux, but the head is wanting. It is inscribed with an affectionate address to him; after which the possessor of the spot is required, as he respects the gods and heroes, to protect from violation and to preserve clean and entire, the images and their bases; and if he failed, severe vengeance is imprecated on him, that the earth might prove barren to him, the sea not navigable, and that perdition might overtake both him and his offspring; but if he complied, that every blessing might await him and his posterity. Another stone with a like formulary, was seen there by Mr. Wood; and a third near Marathon."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, chapter 34, page 160. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

* "Pausanias of Caesarea" is a reference to the travel writer Pausanias.

Other inscribed herm shafts with dedications to Polydeukes, Memnon and Achilles have been found, usually in rural locations and mentioning hunting or deities associated with hunting and rural occupations, such as Artemis (the huntress) and Hermes as "the protector of shepherds". The inscription on another herm of Polydeukes found at the village of Kato Souli (Κάτω Σούλι), 7 km east of Marathon, states that it was set up by Herodes where he used to hunt with the youth. A longer inscription below this dedication threatens a curse on anyone who disturbs the memorial.

Πολυδευ-

κίωνα, ὃν ἀν-

θ’ υ[ἱ]οῦ ἔστε-

<ρξ>εν καὶ ἐνθά-

δε Ἡρώδης <ἀν>-

έθηκεν ὅτι ἐν-

θάδε καὶ περὶ

θήραν εἶχον. |

|

Here too Herodes dedicated

Polydeukion, whom he loved

as a son, because here too

they hunted together. |

Inscription IG II² 3970 (dedication to Polydeukes) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Below the dedication is a longer interdictory curse.

π]ρὸς θεῶ[ν καὶ ἡρώω]ν ὅ[στις]

[εἶ ὁ ἔ]χων [τὸν χῶρον], μήπο[τε μετ]-

ακεινήσ[ῃς τούτω]ν τ[ι· καὶ τὰς τ]-

ούτω[ν τῶν ἀγαλμάτων εἰκόν]-

ας κα[ὶ τειμὰς ὅστις ἢ καθέλοι ἢ]

μετακεινοίη, [τούτῳ μήτε γῆν κ]-

αρπὸν [φέρειν μήτε θάλασσαν πλ]-

[ω]τὴ[ν εἶναι, κακῶς τε ἀπολέ]-

σθαι αὐτο[ὺς κ]α[ὶ γένος. ὅστις δὲ]

κατὰ χώ[ραν φυλάττοι καὶ τειμῶν]

[τ]ὰ εἰωθό[τ]α [καὶ αὔξων διαμέ]-

[ν]οι, πολ[λὰ καὶ ἀγαθὰ εἶναι τ]-

[ούτ]ῳ κα[ὶ] αὐ[τῷ καὶ ἐκγόνοι]-

[ς]· λ[υμήν]ασ[θαι δὲ μηδὲ λωβή]-

[σα]σ[θαι μηδὲν ἢ ἀποκροῦσαι]

ἢ συν[θραῦσαι ἢ συνχέ]αι [τ]ῆ-

[ς] μορφῆ[ς] κ[αὶ τοῦ σχή]ματος· [εἰ]

[δέ] τις [οὕ]τ[ω] ποιήσει, ἡ αὐτὴ

[κα]ὶ ἐπὶ τού[τ]οις ἀρά. ἀλλ ἐ-

[ᾶ]ν τά τε [ἐπιθέματα τῶν]

μορφ[ῶν ἀσινῆ καὶ ἀκέραια]

[κ]αὶ [τὰ] ὑποστήματ[α, τὰς βάσ]-

εις, ὡς ἐπ[οιήθησαν]. [κ]αὶ ἐπὶ πρώτῳ γε καὶ ἐπὶ π[ρώ]-

[τ]οις ὅστις ἢ προστάξειεν

ἑτέρ[ῳ ἢ] γνώ[μης ἄρ]ξειεν [ἢ]

γνώμη[ι] συμ[βάλ]οιτο π[ερ]-

[ὶ] τοῦ τούτων [τι ἢ κειν]ηθῆν-

αι ἢ συνχυθῆναι. |

|

In the name of the gods and heroes;

whoever you may be master of the

place, never move any of these here; and whoever takes down or moves

these portraits and ornaments, may

his earth bear no fruit, nor his sea

be navigable and may he and his

line be destroyed in a terrible way.

But whoever leaves them in their

place and cares for them and

maintains them as appropriate,

may he and his descendants see

many good things |

Inscription IG II² 13190 (also SEG 21:1092) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Two headless herms of Achilles have been found at Oinoe and Varnavas in the area of Marathon. The Oinoe herm bears the inscription Ἀχιλλεύς (Achilleus) and a 29-line imprecation (curse) by Herodes Atticus (inscription IG II² 13195). In the inscription on the herm from Varnavas, Herodes expressed his friendship with Achilles:

Ἡρώδης Ἀχιλλεῖ·

ὃς βλέπειν σε ἔχοιμι

καὶ ἐν τούτῳ τῷ

νάπει· αὐτός τε

καὶ εἴ τις γ’ ἕτερος,

κἀκεῖνοί [γ’, ἔ]σῃ με-

μνημένο[ς τῆ]ς ἡ-

μετέρας φιλίας ὅ-

ση ἡμεῖν ἐγένετο·

ἱερὸν δέ σε Ἑρμοῦ ἐ-

φόρου καὶ νομίου

ποιοῦμαι. |

|

Herodes to Achilles,

in order to see you

I put you in this wood.

I myself and anyone else,

and all will remember

how great was our friendship.

I make you a dedication to

Hermes, the overseer and pastor. |

Inscription IG II² 3977.

See also an inscribed herm bust of Memnon from Marathon below. |

|

| |

|

|

|

A headless herm (it really is quite orange) inscribed

with a dedication to "hero Polydeukion", sculpted at

the expense of Lucius Octavius Restitutus of Marathon.

ἥρωα Πολυδευκίωνα

Λούκιος Ὀκτάβιος Ῥεστι-

τοῦτος Μαραθώνιος

ἐκ τῶν ἰδίων ἐποίη-

σεν.

Inscription IG II² 3974.

Mid 2nd century AD. From Kifissia.

Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 10208. |

|

| |