|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Selçuk > photo gallery 1 |

| Selçuk gallery 1 |

Selçuk town |

|

|

4 of 30 |

|

|

|

| |

Ruins of the Temple of Artemis (3rd century BC) under water. |

| |

Temple of Artemis

Part 2

Continued from the previous page.

The Ephesians started work on a new, even more magnificent Ionic temple soon after, completing it in the early 3rd century BC. This is the structure whose remains we see today.

Alexander the Great sacrificed at the building site of the temple when he passed through Ephesus in 334 BC and offered to pay for its completion himself, but the Ephesians politely refused his offer. [1]

This enormous building was around 105 metres long, 55 metres wide and 20 metres tall, with a roof supported by 127 columns.

At the end of 2nd century AD the wealthy sophist Titus Flavius Damianus (Damianus of Ephesus) financed the building of a marble portico from the Magnesian Gate of the city to the temple and a lavishly decorated dining hall (ἐστιατήριον, estiaterion) of Phrygian marble in the sanctuary. The portico is thought to have been completed around 210 AD. [2]

The temple was plundered by Nero, and then destroyed by the Goths when they sacked Ephesus in 262-263 AD. It was later apparently partly rebuilt, but allegedly destroyed again in 401 AD on the order of Saint John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople and great opponent of the pagan religions. [3]

What little remained was finally abandoned and left to rot after the cult of Artemis was supplanted by Christianity. Over the centuries its remains were used as building material by the Byzantines, who took many of the temple's columns for the construction of Aghia Sophia in Constantinople. Some of the stones from the temple can also be seen in the walls surrounding Saint John's Basilica and the steps to the entrance of the Isa Bey Camii.

Much later still, during the 19th century, some the temple's reliefs and decorated columns, one of which is thought to have been sculpted by Skopas of Paros, were taken to England and are now in the British Museum (see photo below).

Because of the extensive excavations here by British archaeologists, begun in 1869 by John Turtle Wood (1821-1890), locals named the site of the temple "the British hollow". |

|

Marble statue of a

wounded Amazon.

Found in Rome. Thought to

be a copy of a statue made

for the Temple of Artemis,

Ephesus around 440-430 BC,

perhaps by Polykleitos.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 7.

A relief of a wounded Amazon

in this pose, part of a marble

frieze (350 BC) from the altar

of Artemis, is in the Ephesus Museum, Selçuk.

Inv. No. I 811. Height 65 cm. |

|

| |

A coin from the reign of Hadrian (117-138 AD) showing the statue of Artemis in the Artemision.

John Turtle Wood, Discoveries at Ephesus, page 266. Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1877.

See a photo of a similar coin on the History of Ephesus page. |

| |

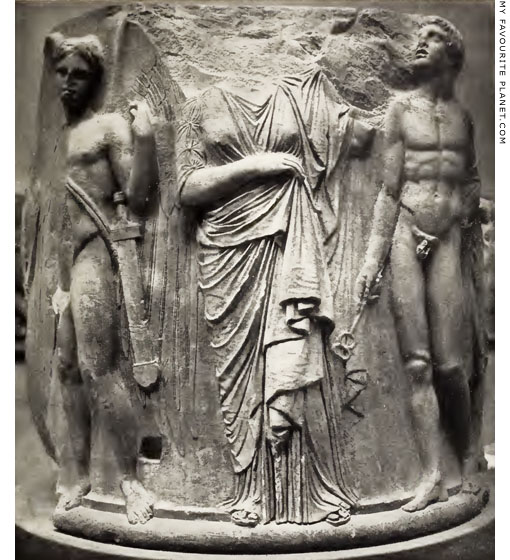

A marble column drum of the later Temple of Artemis at Ephesus,

circa 325-300 BC. Found by the British archaeologist John Turtle Wood

at the southwest corner of the later temple, during excavations in 1871.

|

According to Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 21), thirty six of the temple's columns were decorated with sculpture. Around this column drum, the best preserved, is a sculpted relief of seven figures, two of which have been destroyed.

The three figures in the photo above seem to be the focus of the group. A woman is flanked by two male figures. To her left, the naked, winged youth with a sheathed sword at his side is thought to be Thanatos (Death). The figure to her right is clearly Hermes as Psychopompos (guide of souls to the underworld, see the Hermes page in the MFP People section). The theme of the scene appears to be the death of the woman, whose identity is unknown, but is thought to be one of the tragic heroines of Greek myth, perhaps Eurydike, Alkestis or Iphigenia.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. GR 1872.8-3.9 (Cat. Sculpture 1206).

Height 1.84 metres, diameter 1.97 metres.

Image source: Ludwig Curtius (1874-1954), Die antike Kunst Band II, Tafel XXXI.

Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion M.B.H., Wildpark-Potsdam, 1926.

See also: Reliefs of Hermes on the Sacred Way, Ephesus, on Ephesus gallery page 12.

|

|

|

| |

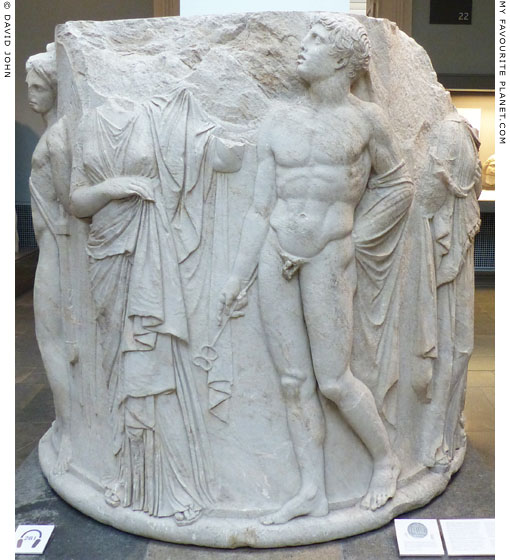

Another view of the column drum showing Hermes Psychopompos.

Hermes stands naked with a cloak wrapped around his left arm.

He holds his caduceus in his right hand. He appears to be stepping

forward and looking up - at what can only be guessed. |

| |

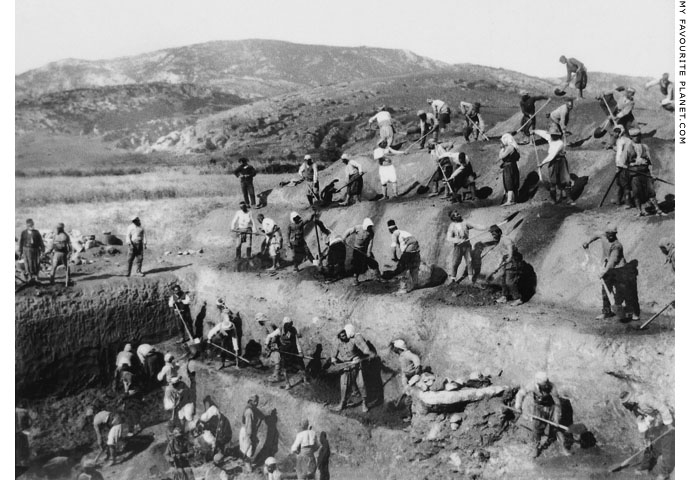

Local workers excavating the Artemision during the 1895 campaign

of the Austrian Archaeological Institute, directed by Otto Benndorf. |

| |

Artemis

Temple

Ephesus

Selçuk |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Strabo on the history of the Temple of Artemis

"As for the temple of Artemis, its first architect was Chersiphron; and then another man made it larger. But when it was set on fire by a certain Herostratus, the citizens erected another and better one, having collected the ornaments of the women and their own individual belongings, and having sold also the pillars of the former temple. Testimony is borne to these facts by the decrees that were made at that time. Artemidorus says:

Timaeus of Tauromenium, being ignorant of these decrees and being any way an envious and slanderous fellow (for which reason he was also called Epitimaeus [Calumniator]), says that they exacted means for the restoration of the temple from the treasures deposited in their care by the Persians; but there were no treasures on deposit in their care at that time, and, even if there had been, they would have been burned along with the temple; and after the fire, when the roof was destroyed, who could have wished to keep deposits of treasure lying in a sacred enclosure that was open to the sky?

Now Alexander, Artemidorus adds, promised the Ephesians to pay all expenses, both past and future, on condition that he should have the credit therefor on the inscription, but they were unwilling, just as they would have been far more unwilling to acquire glory by sacrilege and a spoliation of the temple. And Artemidorus praises the Ephesian who said to the king that it was inappropriate for a god to dedicate offerings to gods.

After the completion of the temple, which, he says, was the work of Cheirocrates (the same man who built Alexandreia and the same man who proposed to Alexander to fashion Mount Athos into his likeness, representing him as pouring a libation from a kind of ewer into a broad bowl, and to make two cities, one on the right of the mountain and the other on the left, and a river flowing from one to the other) - after the completion of the temple, he says, the great number of dedications in general were secured by means of the high honour they paid their artists, but the whole of the altar was filled, one might say, with the works of Praxiteles.

They showed me also some of the works of Thrason, who made the chapel of Hecate, the waxen image of Penelope, and the old woman Eurycleia. They had eunuchs as priests, whom they called Megabyzi. And they were always in quest of persons from other places who were worthy of this preferment, and they held them in great honor. And it was obligatory for maidens to serve as colleagues with them in their priestly office.

But though at the present some of their usages are being preserved, yet others are not; but the temple remains a place of refuge [asylum, see previous page], the same as in earlier times, although the limits of the refuge have often been changed; for example, when Alexander extended them for a stadium, and when Mithridates shot an arrow from the corner of the roof and thought it went a little farther than a stadium, and when Antony doubled this distance and included within the refuge a part of the city. But this extension of the refuge proved harmful, and put the city in the power of criminals; and it was therefore nullified by Augustus Caesar."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, sections 22-23. Loeb Classical Library edition, translated by H. L. Jones. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and William Heinemann, London, 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

|

|

|

2. Damianus of Ephesus

Titus Flavius Damianus (Φλάουιος Δαμιανός, circa 140-210 AD) was a member of one of the most distinguished families in Ephesus and inherited his great wealth. He may have acquired at least some of his fortune when he married Vedia Phaedrina, one of the last of the influential Vedii Antonini family (see the note on Ephesus gallery page 65). The dates of his birth and death are unknown; Philostratus wrote that he died in Ephesus at the age of 70, perhaps around 210 AD. During his career he is thought to have served as consul suffectus and grammateus (γραμματεύς, town clerk) of Ephesus.

Damianus made generous donations to the poor and financed a number of buildings in the city, including improvements to the harbour, and perhaps the construction or restoration of the palaestra of the East Gymnasium and baths complex, as well as the construction of a marble stoa between the Temple of Artemis and the Magnesian Gate, which he dedicated to his wife. Remains of the stoa were first discovered by John Turtle Woods during his archaeological excavations in the 1860s (John Turtle Woods, Discoveries at Ephesus. London, 1877).

He played host to Emperor Lucius Verus (reigned 161-169 AD) on his return from his military campaign against the Parthian Empire in 166/167 AD. Lucius Verus' victories over the Parthians were commemorated by the Parthian Monument in Ephesus, constructed around 171 AD (see Ephesus gallery page 42).

Two inscribed statue bases (inscriptions IvE 67 and IvE 3080, now in the Inscriptions Museum, Ephesus), dated 166/167 AD, with almost identical texts honouring Damianus, state that during his term as grammateus of the demos (γραμματεύς, town clerk or secretary) he was also panegyriarch (president) of the Great Ephesia festival, and hosted the legions returning from the victory over the Parthians, provided 201,200 measures of grain to feed them. At this time he promised to build and decorate a hall (οἴκος, oikos) in the "Baths of Varius" on Kuretes Street. However, the form and function of the building are not stated and its identity remains unknown. He is also praised for leaving the city a financial surplus of 127,816 denarii at the end of his term as grammateus.

See:

Angela Kalinowski, Of stones and stonecutters: reflections on the genesis of two parallel texts from Ephesos (IvE 672 and 3080). In: Gerhard Dobesch et al (editors), Tyche Band 21, 2006, pages 53-72. Holzhausen Verlag, Vienna, 2007.

Angela Kalinowski, Toponyms in IvE 672 and IvE 3080: interpreting collective action in honorific inscriptions from Ephesos. Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes, Band 75, pages 117-132. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna, 2006. PDF at austriaca.at.

Lucius Flavius Philostratus (Φλάβιος Φιλόστρατος, circa 170/172 – 247/250 AD) wrote a short biography of Damianus of Ephesus, who was one of his teachers, in The lives of the Sophists (Βίοι σοφιστῶν).

Damianus was a prominent Sophist at a time when Ephesus was one of the three main centres of the Second Sophistic school of philosophy, along with Smyrna and Athens (see also Herodus Atticus). He taught rhetoric and philosophy, and three discussions he hosted before his death provided Philostratus with the material for the biographies of Damianus' teachers, the Sophists Aelius Aristides (Aristeides of Mysia, teaching in Smyrna) and Hadrianus of Tyre (teaching in Ephesus).

"Damianus, then, was descended from the most distinguished ancestors who were highly esteemed at Ephesus, and his offspring likewise were held in high repute, for they are all honoured with seats in the Senate, and are admired both for their distinguished renown and because they do not set too much store by their money. Damianus was himself magnificently endowed with wealth of various sorts, and not only maintained the poor of Ephesus, but also gave most generous aid to the State by contributing large sums of money and by restoring any public buildings that were in need of repair.

Moreover, he connected the temple with Ephesus by making an approach to it along the road that runs through the Magnesian gate. This work is a portico a stade in length, all of marble, and the idea of this structure is that the worshippers need not stay away from the temple in case of rain. When this work was completed at great expense, he inscribed it with a dedication to his wife, but the banqueting hall in the temple he dedicated in his own name, and in size he built it to surpass all that exist elsewhere put together. He decorated it with an elegance beyond words, for it is adorned with Phrygian marble such as had never before been quarried."

Philostratus and Eunapius; The lives of the Sophists, Philostratus, Book II, chapter 23 (sections 605-606), pages 264-269. In ancient Greek and English, translated by William Cave Wright. Loeb Classical Library. Heinemann, London and Putnam, New York, 1922. At the Internet Archive.

Although Philostratus refers to Damianus' use of Phrygian marble "such as had never before been quarried", the expensive purple-veined marble had also been used for the columns of the Library of Celsus, completed around 50-70 years earlier (see Ephesus gallery page 31).

Philostratus also mentioned Damianus' monumental tomb on his estate outside Ephesus. Remains of a monopteros with a tomb chamber and an inscription that indicates the family of Damianus as the owner were excavated in 1929 southeast of the city.

See: Ursula Quatember, Veronika Scheibelreiter-Gail and Stefan Hagel, T. Flavius Damianus und der Grabbau seiner Familie. In: Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien (ÖJh), Band 86, 2017, pages 221-354. Verlag Holzhausen, Vienna, 2018.

The Byzantine encyclopedia the Suda (Σοῦδα, 10th - 11th centuries AD) mentioned three highlights of Damianus' career:

"Δαμιανός: Damianus, Damianos: Of Ephesus. Sophist. He was raised to consular rank under the emperor [Septimius] Severus, was governor of Bithynia, and constructed the domed stoa which extends to the temple outside Ephesus."

Suda, Δαμιανός, delta 45. At Suda On Line.

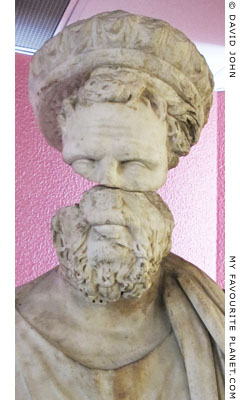

The statue from the East Gymnasium, Ephesus thought to be a portrait of Titus Flavius Damianus wearing a "bust crown" (see photo, above right), a headdress decorated with a row of busts of deities and/or emperors, in this case 15 all around.

A similar statue, also thought to be a portrait of Damianus is now in the Louvre, Inv. No. MA 4705.

According to another theory the statues are portraits of member of the Aphrodisian family of the Vedii Antonini (see Ephesus gallery page 65). The theory that bust crowns were insignia of priests of the Roman imperial cult has also been questioned.

See:

Lee Ann Riccardi, The bust-crown, the Panhellenion, and Eleusis, A new portrait from the Athenian Agora. Hesperia 76 (2007), Pages 365-390. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Barbara Burrell, False fronts: separating the aedicular facade from the Imperial cult in Roman Asia Minor. American Journal of Archaeology 110 (2006), pages 437-469. |

|

Detail of a marble statue (often

referred to as a statue of an

agonothetes) thought to be a

portrait of the Ephesian Sophist

Titus Flavius Damianus as a priest

of the Roman imperial cult,

wearing a bust crown with 15

miniature imperial and/or divine

busts (all now headless).

Circa 193-211 AD. Found in the

exedra of the East Gymnasium,

Ephesus, 1930. Height 232 cm,

height of head 35 cm.

Izmir Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 648.

Another statue thought to be a

portrait of Damianus was found

in the Vedius Gymnasium. |

|

3. Saint John Chrysostom's part in the destruction of the Temple of Artemis

Many internet sources slavishly copy each other in citing John Freely as writing that the Temple of Artemis was destroyed "by a mob led by St. John Chrysostom" (John Freely, The western shores of Turkey: discovering the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts, 2004). John Freely is an acknowleged expert on Turkish history, and can be usually depended on for accurate, interesting and well-written information. However, we have so far found no other reference to Chrysostom's direct action in the destruction. In his splendid book The companion guide to Turkey (1979), Freely makes no mention of this incident.

John Chrysostomos (Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος, circa 349-407 AD) was given the surname "golden-mouthed" because of his eloquence. Born at Antioch, he was Patriarch (Archbishop) of Constantinople circa 397-403 AD.

Chrysostomos visited Ephesus in early 401 at the invitation of several bishops in order to settle church disputes. After deposing six bishops, passing judgement on another and appointing a new archbishop, he returned to Constantinople.

See James Hannam's discussion of reports by early church authors in The destruction of the Temple of Artemis. bedejournal, June 2010.

He points out, among other things, that the report of Chrysostomos' visit to Ephesus in Palladius’ Life of Chrysostom, Book 14, does not mention the Temple of Artemis, and that accounts by other authors of involvement by Chrysostomos or other early Christians in the destruction of the temple (for example a legend in the apocryphal Acts of John) are vague or questionable at best. |

|

|

Map, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your

website, project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

|