Alexander

the Great |

Alexander and coinage |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Two silver tetradrachms minted in Macedonia 336-323 BC,

during the reign of Alexander the Great ("lifetime issues").

Alpha Bank Numsimatic Collection, Athens, Greece.

Both coins and the Celtic coins below shown at the same scale.

|

|

The obverse side (left photo) shows the head of Herakles (Ἡρακλῆς) in profile, facing right, wearing the headdress made from the skin of the Nemean Lion. On some coins of this type the lion's head has more elaborate details and the skin is shown tied around Herakles' throat by its forepaws. On this example the design has been reduced to bold, simple forms.

Herakles was most often depicted with a beard in ancient Greek art and on coins, but heads of a beardless Herakles wearing the lionskin appear on some of the oldest known coins, including electrum hekte (= 1/6 stater) coins of Erythrai (Ἐρυθραί), Ionia, issued around 550-500 BC. Beardless Herakles also appears on Sicilian coins of the 5th century BC, and silver tetradrachms of around 425-405 BC from Kamarina (Καμάρινα), on the south coast of Sicily, have a head of beardless Herakles wearing the lionskin, similar to that on the coins of Alexander. [4] Similar heads also featured on coins of previous Macedonian kings Amyntas III (ruled 393 BC and again 392-370 BC) and his son Perdiccas III (ruled 368-359 BC).

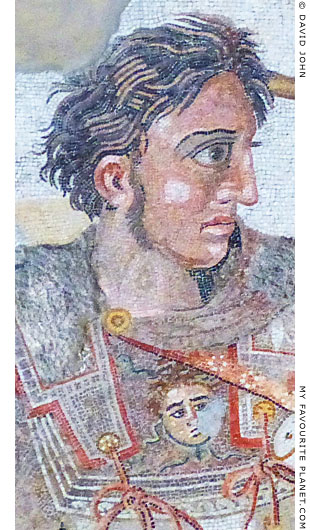

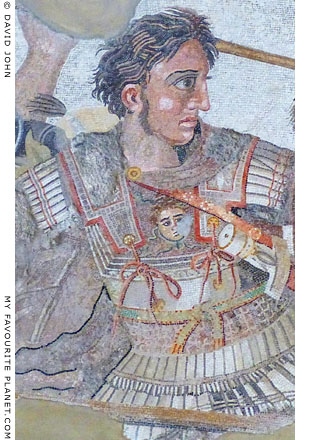

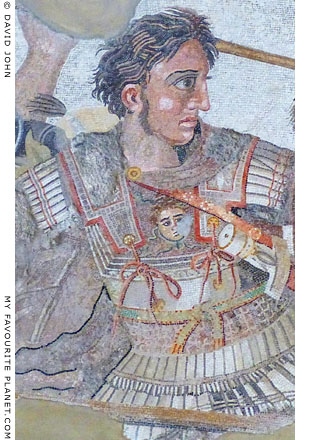

According to theories developed by a number of scholars, the face of Herakles on the coins issued during Alexander's lifetime in Macedonia and other regions he conquered gradually came to resemble portraits of the king himself as he became associated with the invincible hero-god, claimed by Macedonian rulers as an ancestor and founding father. While debate on the matter continues, it seems certain that coins issued by Alexander's successors (the Diadochi) bear portraits of the great king in the guise of Herakles (see photos below).

On the reverse side (right photo) Zeus Aetophoros (Ζευς αετοφόρος, Zeus holding an eagle) is seated on a stool, facing left, holding a sceptre vertically with his left hand, which his held behind him (to the right). On his right hand, stretched out in front of him (to the left), stands an eagle. He is naked to the hips, below which his lower torso and legs are wrapped in a himation (cloak). The lower right leg is drawn back to the right, so that the foot rests behind (to the right of) the left foot. Inscribed vertically to the right: AΛΕΞANΔΡΟΥ (Alexandrou, of Alexander).

In the left field, below the eagle are the marks Λ above a torch (often referred to as a race torch), and below the stool is a cross or star monogram. Coins with these marks are usually said to be from the Macedonian royal mint at Amphipolis, where the majority of Alexander's Macedonian silver tetradrachms are believed to have been minted, made with silver from mines on nearby Mount Pangaion. However, it remains uncertain - yet another subject of debate - where many coins of this type were minted, and it is also thought that at least some of them may be from other Macedonian mints such as the capital Pella and Philippi (on the other side of Pangaion from Amphipolis). [5]

An enormous number of coins of this type have survived and are now in several public and private collections. The Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection) of the State Museums Berlin (SMB) owns over 1400 from different mints and eras, varying enormously in quality and condition (from excellent to totally corroded). The SMB website has a searchable online catalogue, Münzkabinett - Online Catalogue, with images and details of items in its numismatic collection, including coins displayed in the Bode Museum, Altes Museum and Neues Museum. A search for "Alexandros III tetradrachme" returned 1480 results, the vast majority of which are coins of this type and classified as Macedonian.

It is evident that the die-cutters copying the designs at various locations over many generations varied in artistic and technical skills, as well as the ability to identify and imitate details such as the face and the complex forms of the lionskin headdress. Thus it is not so surprising that non-Greeks who copied such coins (see below) had difficulty imitating the iconography and inscriptions. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Two silver tetradrachms minted by the Eastern Celts in the Danube region,

2nd century BC, imitating designs on Macedonian coins such as those above.

Alpha Bank Numsimatic Collection, Athens, Greece.

|

|

| Greek coins were copied by various peoples beyond Hellenized areas, particularly by Celts and Thracians, often for centuries after they were first circulated. The originals were acquired through trade, by mercenaries who had worked for Greeks (both Philip II and Alexander hired Celtic mercenaries), or as war booty. In some cases, as copies were successively made of copies, the motifs gradually became indistinct or stylized to the point of abstraction, and the original iconography, religious significance and political propaganda messages dissolved. Since many were produced by people who could not read Greek, the inscriptions were often reduced to letter-like forms (i.e. nonsense) or simple shapes such as rows of dots. |

|

| |

"Two Macedonian medals of the same device; one barberous, the other elegant work."

An engraving after drawings by Nicholas Revett (1720-1804), showing a Macedonian

coin with the head of Alexander/Herakles and Zeus Aetophoros below an ancient imitation.

Source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated,

Volume 3, chapter IX, plate V. John Nichols, London, 1794. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Macedonian silver tetradrachm with a portrait

of Alexander in the guise of Herakles wearing

the skin of the Nemean Lion's head, facing

right. One of the lion's forepaws is shown

below his jaw. The reverse side shows Zeus

Aetophoros and is inscribed AΛΕΞANΔΡΟΥ,

as in the coin above.

Circa 310-275 BC. Minted in Macedonia

or Greece, perhaps during the reign of

Philip III of Macedon (Philip Arrhidaios,

Φίλιππος Γ΄ ὁ Ἀρριδαῖος; reigned

323-317 BC), Alexander's half brother

and successor as king of Macedonia.

Diameter 28 mm, weight 17.11 g.

Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection),

State Museums Berlin (SMB).

Bode Museum. Inv. No. 18202512.

Purchased in 1875 with the coin collection

of Graf Anton Prokesch von Osten.

See Big Money at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

| |

Silver tetradrachm of Ptolemy I Soter of Egypt

(reigned circa 305-283 BC), showing the head

of the deified Alexander wearing an elephant

hide, over which is the Uraeus, the serpent

symbol of Egyptian pharoahs, and below

it the aegis of Zeus.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

|

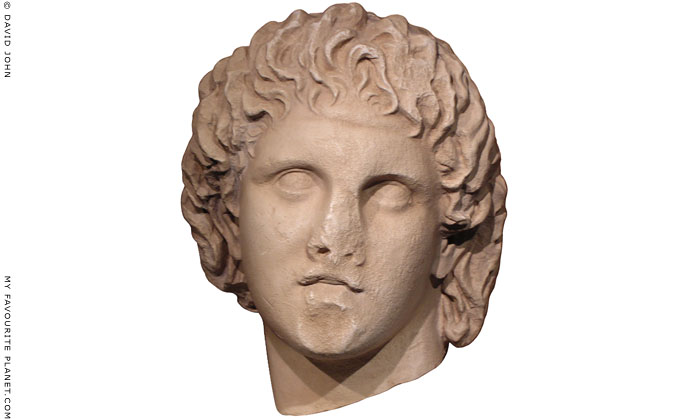

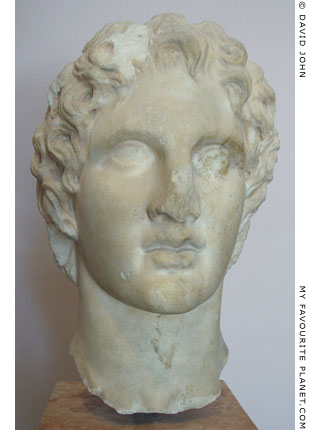

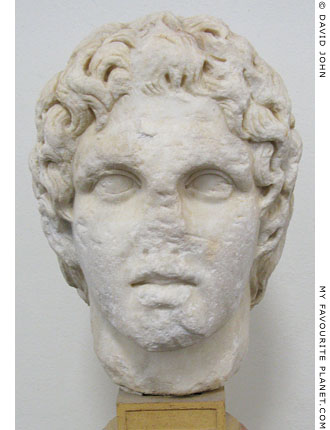

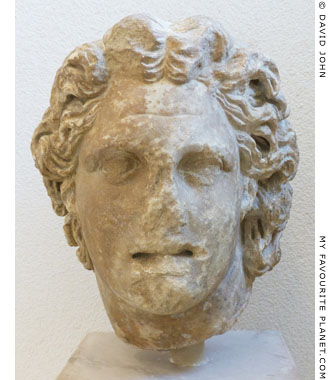

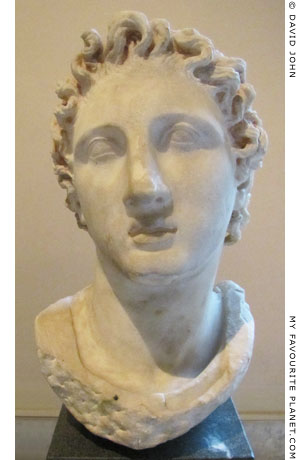

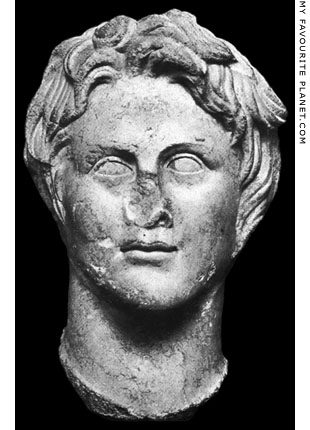

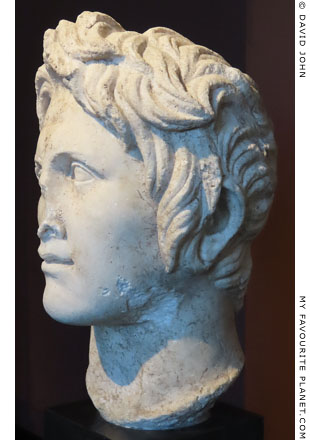

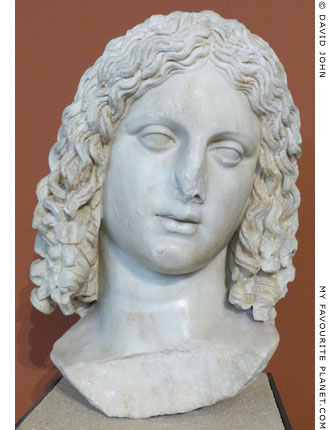

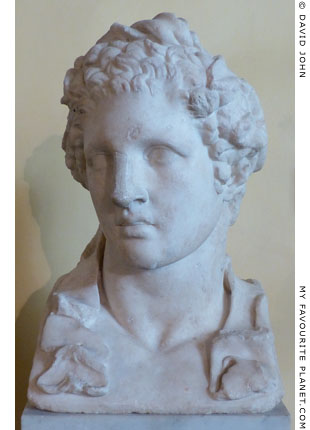

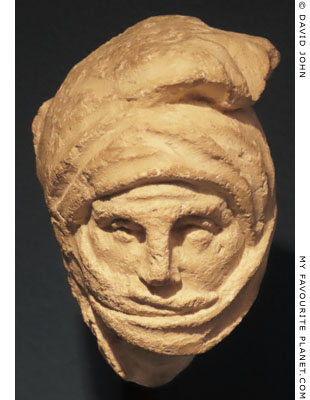

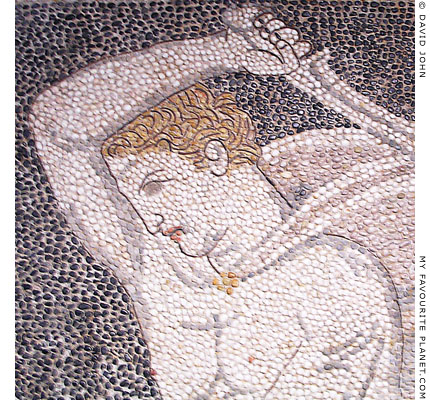

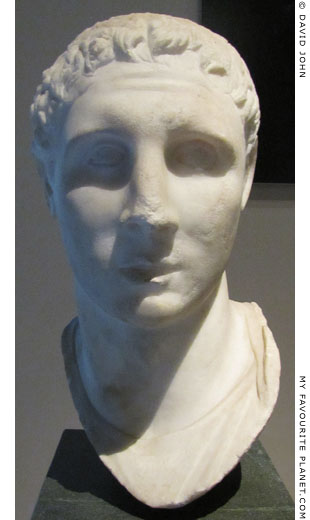

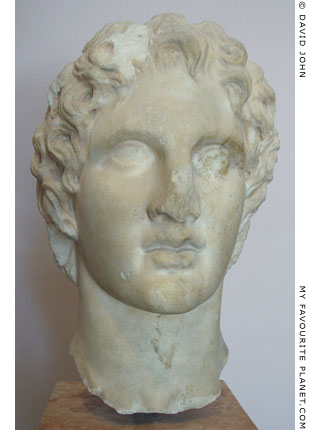

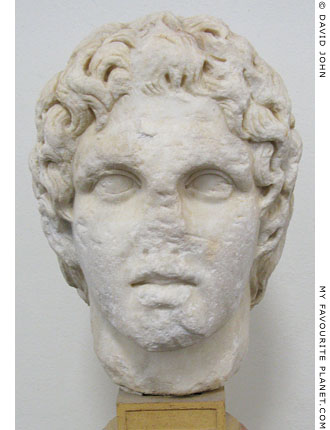

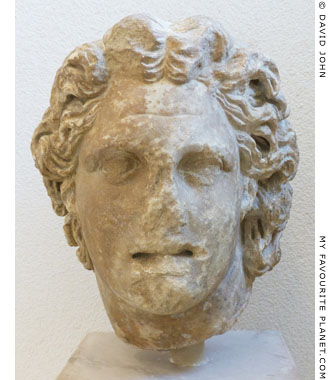

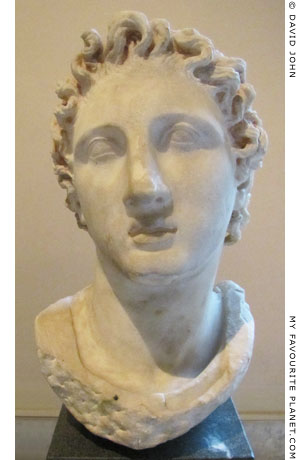

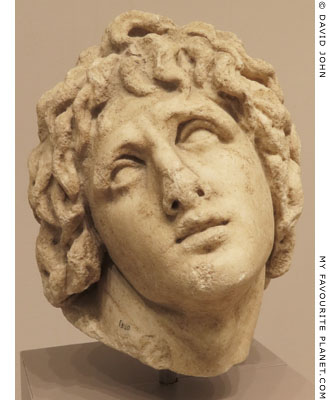

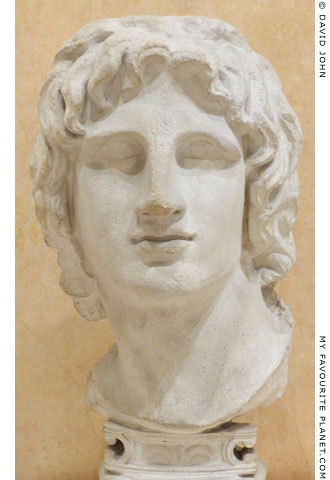

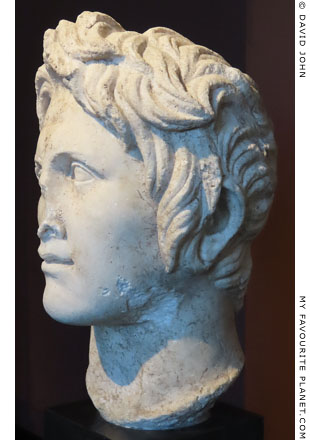

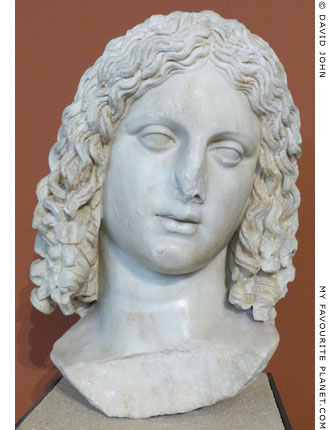

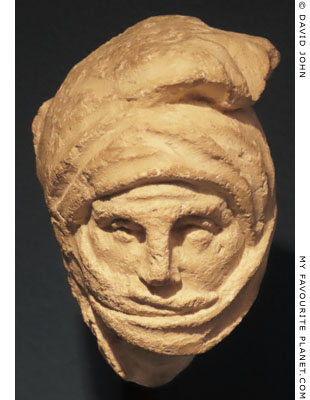

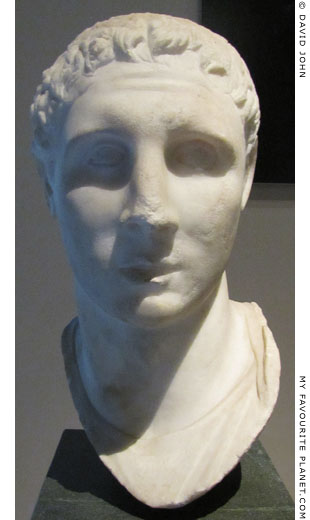

Head of Alexander the Great wearing

a lion-skin headdress. Pentelic marble,

circa 300 BC. Found in February 1873

at the Dipylon Gates, Kerameikos,

Athens. Height 28 cm.

The Greek letters are thought to be magical

symbols scratched on the head later.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. 366.

For decades after its discovery the head

was believed to depict a woman, perhaps

the mythical Lydian queen Omphale.

See: Valerios Stais, Marbres et bronzes

de Musée National, Volume 1, No. 366,

page 71. P. D. Sakellarios, Athens, 1910

(2nd edition). At the Internet Archive. |

| |

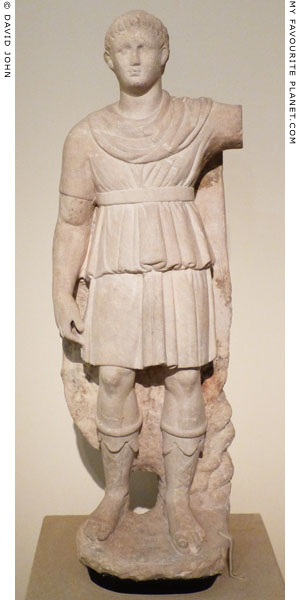

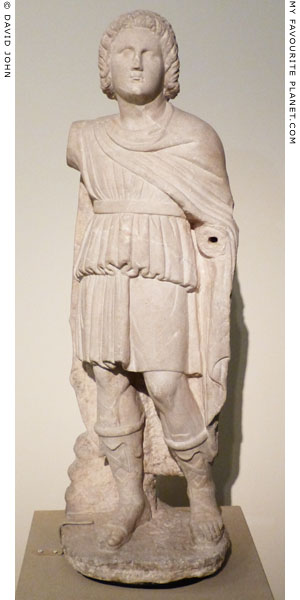

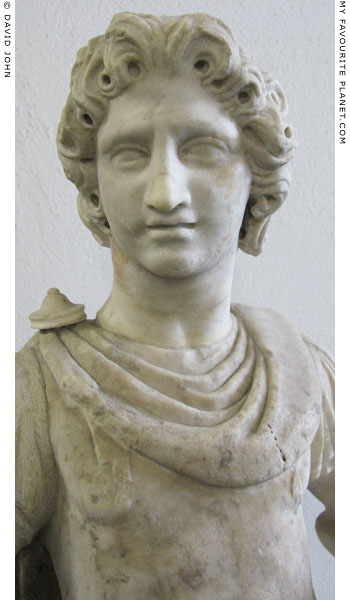

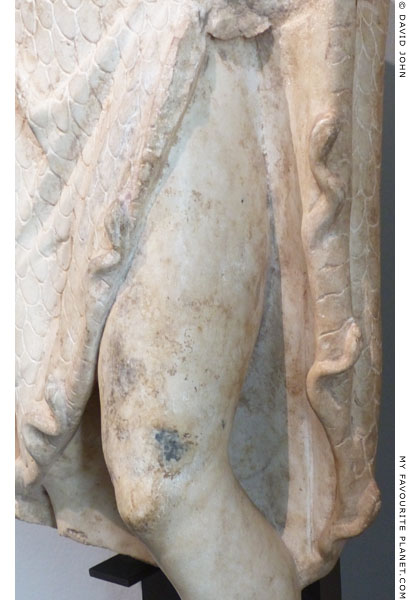

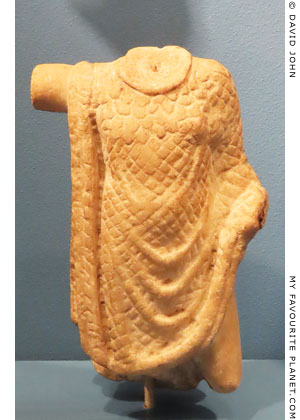

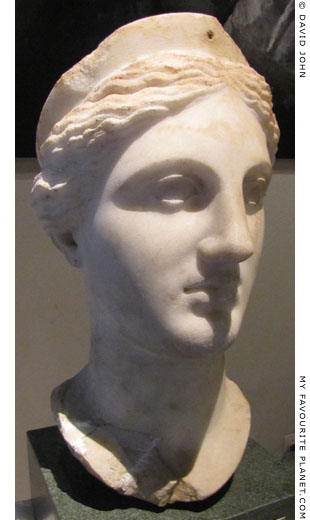

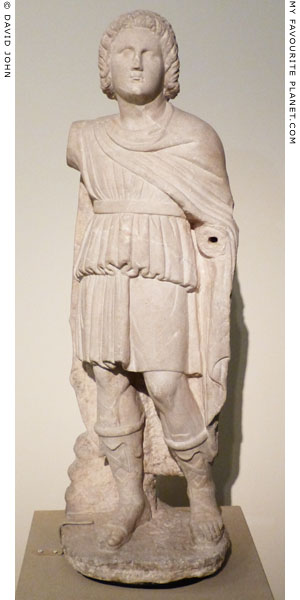

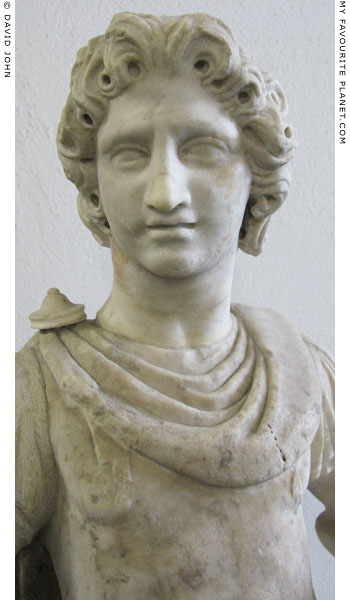

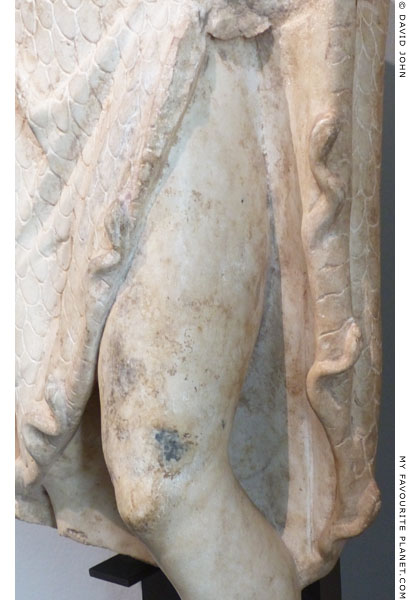

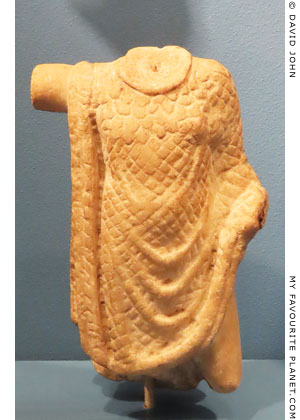

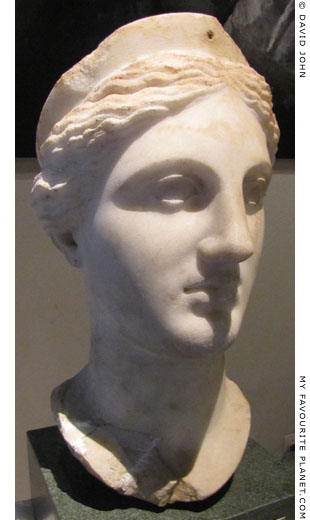

Marble statuette of Herakles wearing

the skin of the Nemean lion.

Pentelic marble, 350-325 BC. Height 54 cm.

Found 1885 near Agia Irene church, Athens.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. NAM 253.

(Photo taken when the statuette was on loan

to the Numismatic Museum, Athens in 2011.) |

| |

| |

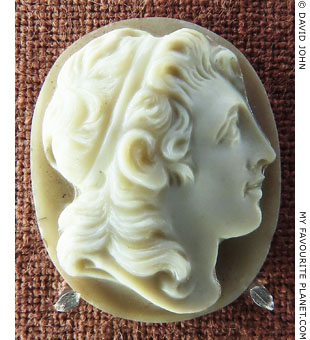

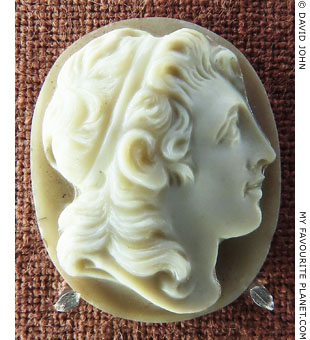

Sardonyx cameo gem with a portrait bust

of Alexander the Great, facing right.

Late Hellenistic period.

Numismatic Museum, Athens.

Collection of K. Karpanos. |

|

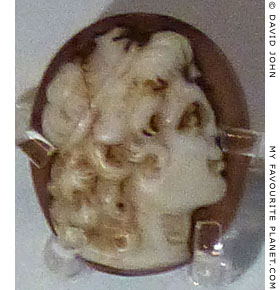

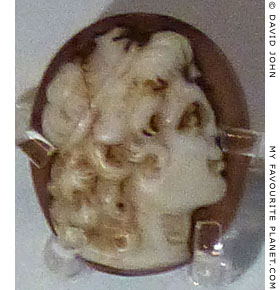

Onyx and chalcedony cameo gem with

a portrait of Alexander the Great.

125-75 BC.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Inv. No. AN1941.403.

Sir Arthur Evans bequest. |

|

| |

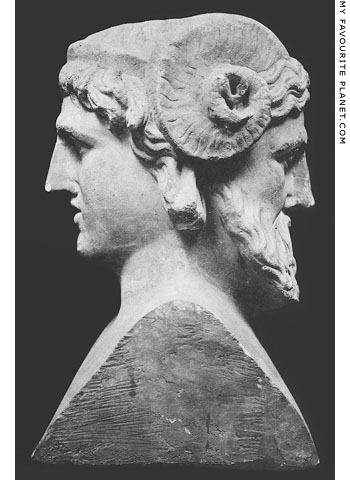

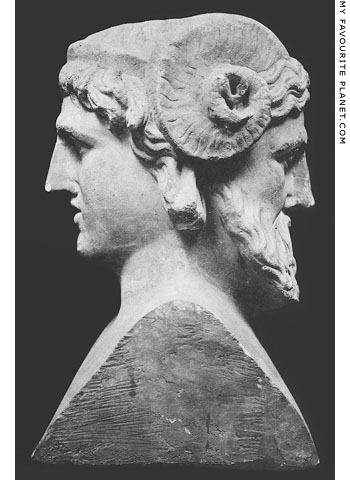

A portrait of Alexander the Great, in profile,

facing right, wearing a diadem (headband)

and the ram's horns of Zeus Ammon, on

a silver tetradrachm of Lysimachus

(Λυσίμαχος, circa 360-281 BC), king of

Thrace 305-281 BC.

Thought to be the earliest depiction of

Alexander the Great wearing ram's horns,

the symbol of the syncretic Egyptian-Greek

god Zeus Ammon. Alexander visited the

sanctuary of Ammon (Amun) at Siwa, in the

Western Desert of Egypt, in 332/331 BC.

This coin type and imitations of it (referred

to as Lysimachi or pseudo-Lysimachi)

continued to be produced at several

Hellenistic mints long after the death

of Lysimachus and into the Roman

period (see below).

Numismatic Museum, Athens.

See also a portrait of Alexander as Zeus

Ammon on an Aboukir medallion below. |

|

A similar silver tetradrachm of Lysimachus,

minted in Lampaskos, Mysia, 297-281 BC.

New Archaeological Museum

"Arethousa", Chalkis, Euboea. |

|

"The Alexander Gem", an elbaite (a rare

variety of tourmaline) sealstone with a

portrait of Alexander the Great wearing

the ram's horns of Zeus Ammon.

325-300 BC. Purchased in Beirut. The tiny

inscription below the neck is carved in

Indian Kharoshti script, suggesting that

the gem was cut in the east of his empire,

perhaps near India. Width 2.4 cm.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Inv. No. AN1892.1499.

Reverend G. J. Chester bequest. |

|

|

Replica of a silver decadrachm coin showing Alexander fighting King Poros

of Paurava (in present day Pakistan) on an elephant, at the Battle of the

Hydaspes River (today the Jhelum) in May 326 BC. Alexander may have

issued the coins in Babylon, 325-323 BC, to commemorate his victory.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. HCR6280.

|

|

Alexander the Great driving a chariot

drawn by four elephants, on a gold stater

of Ptolemy I of Egypt. Minted in Alexandria,

circa 305-298 BC.

Bode Museum, Berlin. |

This type of coin is known as a "Poros medallion" or "Franks medallion", after the historian, museum administrator and collector Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826-1897), who donated the first known example to the British Museum in 1887. It has been suggested that the coin may have been part of a hoard of ancient precious objects known as the "Oxus Treasure", discovered near the Oxus River (the Amu Darya, Afghanistan).

Franks' coin was first published in an illustrated article in The Numismatic Chronicle in 1887, where it was stated that it was "... found two or three years ago at Khullum, in Bokhara, and presented to the British Museum by Mr. A. W. Franks."

The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, Third Series, Volume VII, "VI. New Greek coins of Bactria and India", pages 177-181. Bernard Quaritch, London, 1887. At the Internet Archive.

The reverse side of the coin shows a standing helmeted figure, believed to be Alexander, holding a spear or sceptre in his left hand and the thunderbolt of Zeus in his left, being crowned by a winged Nike (Victory). The coin type is considered historically important for several reasons, particularly because it may have been minted during Alexander's lifetime, and is thought to depict him fighting in a significant battle on one side, and in the guise of Zeus on the other.

Following Alexander's victory at the Hydaspes, he made Poros (Πῶρος, the name given him by the Greeks; his real name is unknown; Latin, Porus) his satrap in the area, abandoned his military expedition through India and returned westwards to Babylon, where he died three years later.

See: Frank L. Holt, Alexander the Great and the mystery of the elephant medallions. Hellenistic culture and society No. 44. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2003.

Holt examines numismatic and iconographic aspects of the medallions, their historical and political significance, the circumstances of finds of the coins, including the Oxus hoard and another large hoard found near Babylon in 1972-1973, as well as arguments concerning when, where and for whom they may have been minted. One suggestion is that Alexander authorized them as a special commemorative issue for veterans of his Indian campaign. The inscriptions on the coins (Alexander's name does not appear) and their poor and uneven quality suggest that they were minted "on the road in the East" or at a local rather than royal mint. |

|

|

|

| |

A portrait of Alexander the Great in profile, facing right,

with a ram's horn of Zeus Ammon around his ear. The

obverse side of an "Aesillas coin", a silver tetradrachm

of the Roman province of Macedonia, around 95-75 BC.

Below the head is the Greek inscription ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΩΝ

(of the Macedonians). Alexander's image was used as

a symbol to encourage the Macedonians in the wars

against King Mithridates VI of Pontus.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

Many coins of the "Aesillas" type have been found, individually or in hoards. On the reverse side they are usually inscribed in the Latin alphabet with the name "AESILLAS" and the letter "Q", an abbreviation for Quastor (investigator), a Roman official who, under the governor of the province of Macedonia, supervised the state treasury. It was one of the lowest ranks of public officials and a first career step for young men aged around 27-30 on the cursus honorum (course of offices, see for example the career of Aulus Claudius Charax of Pergamon). A smaller number of surviving coins are inscribed instead with the name of a certain Sura: "SVVRA LEG PRO Q" (Sura Leg[atus] Pro Q[uaestore]; Sura Legate [acting] in the capacity of Quaestor). Nothing is known for certain about either Aesillas or Sura, although there are theories concerning their identities.

Below the inscription, depicted in relief is the club of Herakles standing vertically, flanked by symbols of Roman authority: to the left by a basket with a lid (cista) representing a money chest, or a cista mystica, a religious symbol (see Demeter and Persephone); and to the right by a quaestor's chair (sella). These and the inscription are surrounded by a laurel wreath.

Coins of the Aesillas type are thought to have been minted in Thessaloniki (θεσσαλονίκη, Thessalonike), the capital of the Roman Province of Macedonia (Latin, Provincia Macedonia; Greek, Ἐπαρχία Μακεδονίας, Eparchia Makedonias). They have been traditionally dated to around 94-88 BC, the time of the First Mithridatic War (circa 89-85 BC), although since 1962 these dates have been challenged, and it has been suggested that some may have been minted as late as the 70s or even the 60s BC, presumably long after Aesillas' period as quaestor. New issues may have been struck during the Second and Third Mithridatic Wars (83-81 BC and 75-63 BC).

On the obverse side (shown in the photo above) Alexander the Great has long, wavy hair and a ram's horn of Zeus Ammon around his ear. The style of portrait is very different from those shown on coins since Alexander's lifetime. The artistic quality of the head is not so fine, and the face seems soft and feminine, not at all the regal warrior of earlier coins. As we have seen in examples above, his successors had exploited the strong, youthful features of the king to broadcast their own propaganda messages of power, strength, invincibility, stability and continuity. Coins of the types first minted by Lysimachus of Thrace (see above) continued to be minted at several locations long after his death (e.g. Byzantium, Lysimachia, Parium, Cius and Mytilene), and were still in circulation at the start of the first century BC.

During the First Mithridatic War (89-85 BC) against the Roman Republic and its client states in Anatolia, King Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus (Μιθραδάτης Στ' Ευπάτωρ; 135-63 BC, reigned 121-63 BC) struck high value gold staters imitating those of Lysimachus and inscribed with his name, BAΣIΛEΩΣ ΛYΣIMAXOY (Basileos Lysimachou, of King Lysimachos).

However, from at least 95 BC Mithradates also issued coins bearing his own portrait which imtitated that of Alexander (see image, above right). The head of the Pontic king, shown in profile, facing right, is depicted as a young man with long, wind-swept hair, wearing a diadem (headband). There appears to be a hint of the ram's horns of Zeus Ammon among his locks.

It is thought that the Aesillas coins may have been designed as a response to these, perhaps imitating them, although it is not certain which were minted first. As is often the case with depictions on coins, it has also been suggested that the Alexander head on the Aesillas coins may have been based on a statue of him, although there appears to be no direct evidence of this. [6] However, statues of Alexander continued to be set up in cities throughout the Roman Empire, including Thessaloniki (see below). |

|

A portrait of King Mithradates VI Eupator

of Pontus in profile, facing right, on a silver

tetradrachm minted in Pergamon, which he

captured during the First Mithridatic War,

89-85 BC. See History of Pergamon.

Image source: woodcut in Henry G. Liddell,

A History of Rome, from the earliest

times to the establishment of the Empire,

page 593. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1859. |

|

| |

Alexander

the Great |

The Aboukir and Tarsus medallions |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of Alexander the Great in profile, facing left, wearing a band diadem

and the ram's horns of Zeus Ammon (see above) on a gold Aboukir medallion.

See the reverse side of this medallion and the other

Aboukir medallions in the Bode Museum below.

211-235 AD. Diameter 54 mm, weight 112.66 grams.

Bode Museum, Berlin (Room 242, BM-035/01). Inv. No. 1903/837.

Object No. 18200006. Dressel 1906, A. Purchased in 1902. |

| |

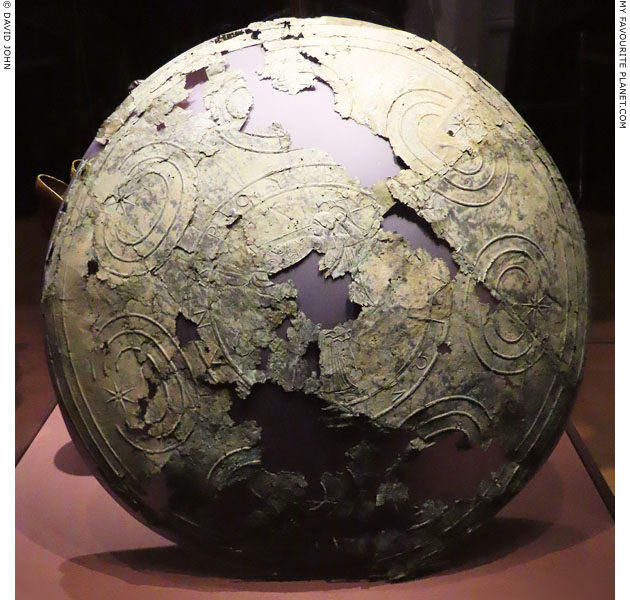

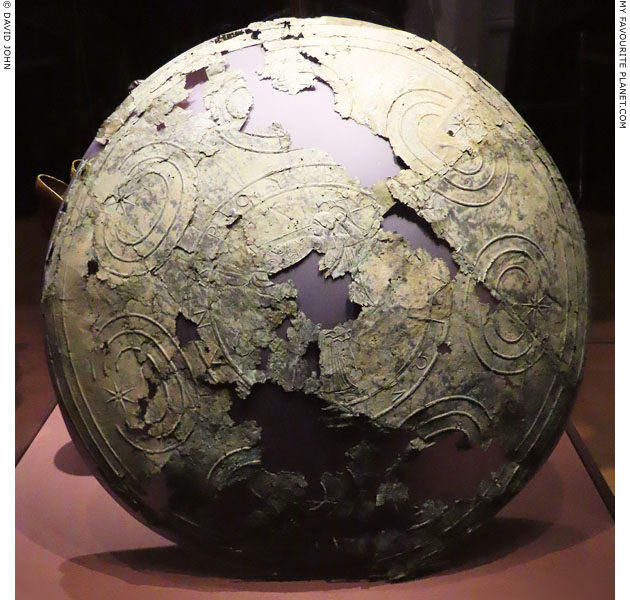

One of twenty large gold medallions discovered in February or March 1902 among a hoard of ancient gold coins in Aboukir (or Abukir), east of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt. They were sold soon after on the art market and are now in four museums: the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (3 medallions); Bode Museum, Berlin (5); the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon (11); and Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum (1, see below). The Aboukir hoard also included 600 gold Aurei coins from around 222–306 AD, and 18 or 20 bars of gold.

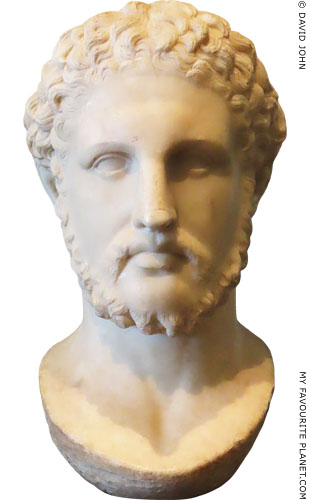

A comparable hoard was found in 1863 (or 1867) in Tarsus (ancient Tarsos, Ταρσός), Cilicia, southern Anatolia (today Turkey), consisting of three similar large gold medallions, two with portraits of Alexander the Great and the third showing Philip II of Macedon, Alexander's father (see below), as well as a large gold medallion of Roman emperor Alexander Severus, issued for his Decennalia of 230 AD, 23 gold Aurei coins minted 72-243 AD, two gold bells (tintinnabula) and jewellery made of gold and lapis lazuli. The four large gold medallions were purchased for 50,000 gold francs in 1868 by agents of Napoleon III and donated by him to the Cabinet des Médailles of the Bibliothèque Imperiale (now the Bibliothèque Nationale de France) in Paris.

The obverse side of each of the twenty three medallions shows one of the following portrait heads: Alexander the Great, Philip II, Alexander's mother Olympias, Apollo, or Emperor Caracalla (reigned 198-217 AD, see below). As is often the case with ancient coins and medals, it is thought that the portraits may have been based on statues. On the reverse sides are depictions of various scenes, some involving Alexander, others featuring Deities (Nike, Athena, Ares, Thetis) and/or fabulous sea creatures.

Although the Tarsus hoard had been quickly accepted as genuine, the exact location and circumstances of the Aboukir hoard's discovery are unknown, and many scholars suspected the medallions were modern forgeries. Following the announcement of the find in March 1902, they were offered to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the British Museum, but both institutions turned them down.

However, their authenticity was argued by Heinrich Dressel (1845-1920) director of the Münzkabinett (Coin Cabinet) of the State Museums in Berlin (then still the Royal Museums). In his 1906 publication, Fünf Goldmedaillons aus dem Funde von Abukir (Five gold medallions from the finds from Aboukir), Dressel described all twenty medallions, assigning each a letter from A to U (for some reason there is no medallion J), which became the de facto standard for identifying individual medallions in later publications. The Münzkabinett purchased four (medallions A-D) from the Paris-based Armenian art dealer Mirhan Sivadjian in July 1902, and the fifth (medallion E) in 1903. The others were bought by private collectors, mostly in the United States, and were later acquired by museums. [7]

Due to their varying sizes, weights and gold purity (around 88-96 %), it seems unlikely that the medallions were issued as coins, but are thought to have been minted during the reigns of Roman emperors Elagabalus (218-222 AD) and Severus Alexander (222-235 BC) as gifts for high-ranking guests, officers and officials at the Alexandrian Olympic games, held in honour of the deified Alexander the Great in Macedonian cities such as Veria (225-250 AD). According to another theory, they were awarded in 242-243 AD for victories in the Olympic festival at Veria, attended by Emperor Gordian III (reigned 238-244 AD). They have been referred to as niketeria (νικητήρια, victory medals). |

|

The reverse side of Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 1

(BM-035/01, see above).

Winged Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, driving a quadriga

(four-horse chariot) to the right. She carries a palm branch and

a taenia in her left hand, and holds the reins in the right.

Inscribed to the left and below the quadriga:

ΒΑCΙΛΕωC ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ

Basileos Alexandrou, King Alexander.

Bode Museum, Berlin.

NOTE: This and the reverse sides of the other Berlin Aboukir

medallions in the photos below are museum copies, exhibited

so that both sides can be viewed by visitors. The copies are

smaller than the originals. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 2.

Obverse side (left): A bust of Alexander the Great in profile, facing left with raised

head, wearing a cuirass covered by a cloak, and a high-crested Attic helmet decorated

with a relief of Artemis riding a bull on the side. The crest is supported by a sphinx.

Reverse side (right): On the left winged Nike, her left foot resting on a helmet, and winged

Eros hold a shield decorated with a relief of two figures (perhaps Alexander and a lover)

clasping hands. On the right, a set of trophy armour (tropaion) with two seated captives.

Inscribed to the left, above and right of the image:

ΒΑCΙ-ΛΕ-ΩC - ΑΛΕ-ΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ (Basileos Alexandrou, King Alexander).

Diameter 60 mm, weight 105.06 grams.

Bode Museum, Berlin (Room 242, BM-035/02). Inv. No. 1905/01.

Object No. 18200012. Dressel 1906, B. Purchased in 1902. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 3.

Obverse side (left): A bust of Alexander the Great, shown frontally with his bare head raised.

He wears a band diadem and a cuirass decorated with reliefs: on the shoulder flap Athena

Promachos, and on the breast a Triton. He holds a spear and a round shield, also decorated

with reliefs. In the central medallion is a bust of Gaia (Earth), above which are the heads of

Helios and Selene (Sun and Moon). Around these are five signs of the zodiac: Aries, Taurus,

Gemini, Cancer and Leo (the period 21st March - 23rd August). The head (and particularly

the hairstyle) has been compared to the marble statue head from Pergamon (see below).

It is thought that the symbolism of the relief figures indicates that this is a depiction of

Alexander as Cosmocrator (see below).

Reverse side: The same as on medallion No. 2 above.

Diameter 56 mm, weight 84.30 grams.

Bode Museum, Berlin (Room 242, BM-035/03). Inv. No. 1907/230.

Object No. 18200016. Dressel 1906, C. Purchased in 1902. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 4.

Obverse side (left): A bust of Olympias (Ὀλυμπιάς, circa 375-316 BC), mother of Alexander the Great,

in profile facing left, veiled (the back of her head covered with part of her cloak), wearing a diadem

and a bracelet in the form of a snake coiled around the wrist of her raised right forearm. In her hand

she holds a sceptre with a small sphere at the top. This type of portrait of Olympias is known from

other Roman period coins, including late Roman contorniates, (bronze medallions, some now in the

Berlin Münzkabinett, e.g. Inv. No. 1912/306; Object No. 18200661).

Reverse side (right): A naked Nereid (sea Nymph), sitting on her garment and facing left,

rides a fabulous sea monster, the front (left) part of which is a bull, and with the tail of a fish.

Her hair is bound, she wears an armband on the upper left arm, and in her raised right hand

she holds a garland which she is placing around the creature's neck. Among the waves are

two shellfish and two dolphins. The image is similar to several in ancient art, including coins

and mosaics, showing the Nereid Thetis riding a sea creature and carrying the arms made

by Hephaistos to her son Achilles at Troy (see Homer part 2). As Alexander has been

compared to Achilles (and Hephaistion to Patroklos), so Olympias is likened to Thetis.

Diameter 58 mm, weight 81.86 grams.

Bode Museum, Berlin (Room 242, BM-035/04). Inv. No. 1907/229.

Object No. 18200020. Dressel 1906, D. Purchased in 1902. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 5.

Obverse side (left): A bust of Emperor Caracalla (reigned 198-217 AD; see also below),

facing left, wearing a laurel wreath and a cuirass. In his raised right hand he holds

a spear which rests on his right shoulder. He carries a round shield, in the centre of

which is the head of Alexander wearing a diadem facing left, and above it Alexander

with a spear on horseback, hunting a lion. Appearing from behind the left side of

the shield is the head of eagle at the end of a sword hilt.

Reverse side (right): On the left, Alexander the Great seated, wearing a diadem and a

cloak over his lower torso and legs, facing right towards winged Nike, who presents

him with a crested Attic helmet she holds up with her right hand. Her left hand supports

an upright round shield on which is a relief depicting Achilles killing the Amazon queen

Penthesileia (see Homer part 2). This scene is known from other Graeco-Roman artworks,

particularly on sarcophagi. On the left stands the Greek hero, naked, holding a sword in his

right hand. With his left hand he grasps the hair of the Amazon who has fallen to her knees.

Inscribed to the left and above the figures:

ΒΑCΙΛΕVC - ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟC (Basileos Alexandros, King Alexander).

Diameter 48 mm, weight 65.12 grams.

Bode Museum, Berlin (Room 242, BM-035/05). Inv. No. 1908/3.

Object No. 18200021. Dressel 1906, E. Purchased in 1903. |

|

| |

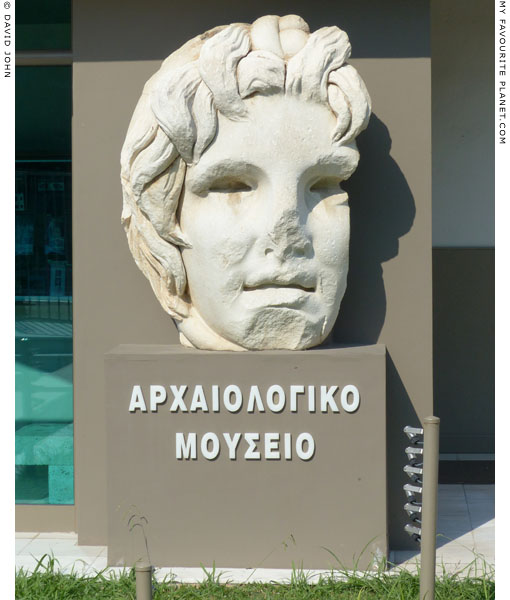

The obverse side of an Aboukir medallion in Thessaloniki, with a depiction

of a veiled bust of Olympias, in profile facing right. She wears a band

diadem, and with her left hand she pulls at the fabric of her veil. The

same die was used to make the obverse of one of the three Aboukir

medallions now in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

On the reverse side is the Nereid Thetis riding a sea monster, made with

the same die as the reverse of Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 4 above.

211-235 AD. Diameter 58 mm, thickness 8 mm, weight 120.06 grams.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. ΜΘ 4304. Dressel 1906, Q.

Purchased at an auction in Basel on 17th November 1962 at the request

of Greek prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, and given to the

museum which had opened to the public a month earlier [see note 7]. |

| |

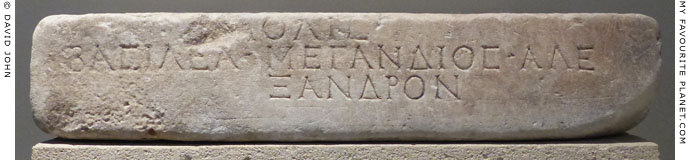

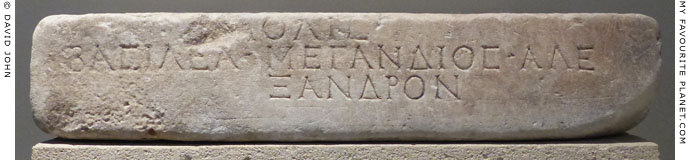

One of the three gold medallions found in 1863 (or 1867) in Tarsus (ancient Tarsos, Ταρσός),

Cilicia, (today southern Turkey), and purchased in 1868 by agents of Napoleon III. On the

obverse side (left) is a portrait bust of Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great,

facing left, wearing a band diadem and a cuirass (in three-quarter view). On the breast,

Zeus, as an eagle, abducting Ganymede. On each shoulder flap, Nike carrying a shield,

and below a thunderbolt. On the reverse (right), winged Nike, carrying a palm branch and

a taenia, driving a quadriga to the right (as on Berlin Aboukir medallion No. 1 above).

Inscribed to the left and below the quadriga:

ΒΑCΙΛΕωC ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΥ (Basileos Alexandrou, [medallion] of King Alexander).

Diameter 64-67 mm, weight 93.85 grams.

Cabinet des Médailles, Paris. Inv. No. 1673.

Image source: Benjamin Ide Wheeler, Alexander the Great: the merging

of East and West in universal history, page 82. G. P. Putnam's Sons,

London and New York, 1900. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Alexander

the Great |

Alexander sculptures

Portraits of Alexander and sculptures associated with him |

|

|

|

| |

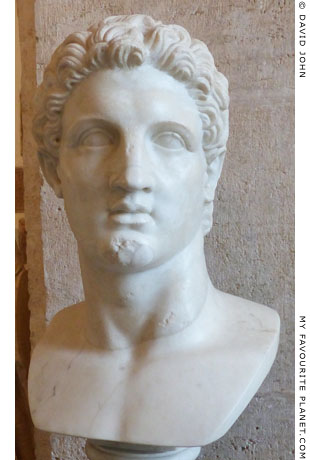

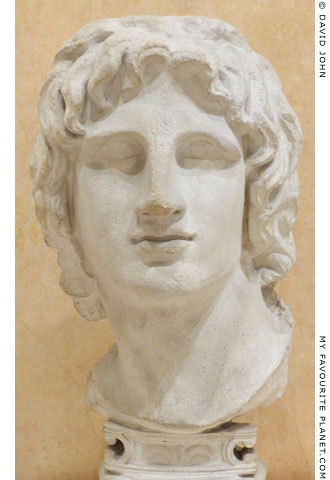

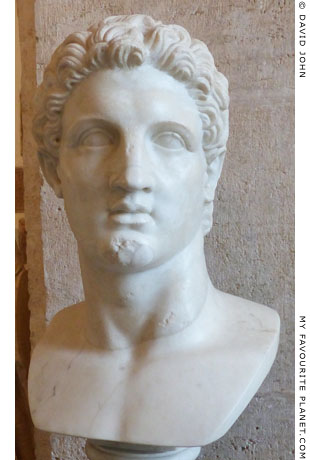

The "Azara Herm", an inscribed marble herm bust

of Alexander the Great.

Roman Imperial period, 1st - 2nd century AD.

Excavated at Tivoli, near Rome in 1779.

Pentelic marble. Height 68.5 cm, width 32.2 cm,

depth 26.5 cm.

Louvre Museum, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 436 (MR 405).

Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen at Wikipedia Commons. |

|

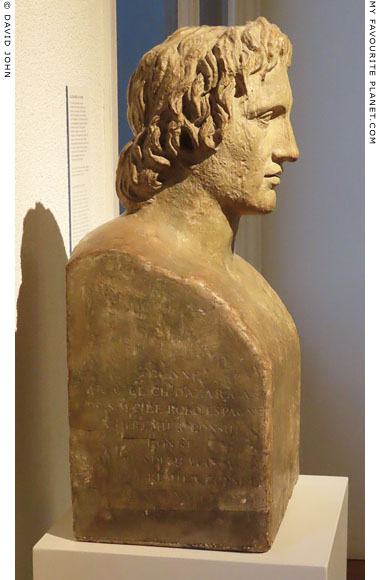

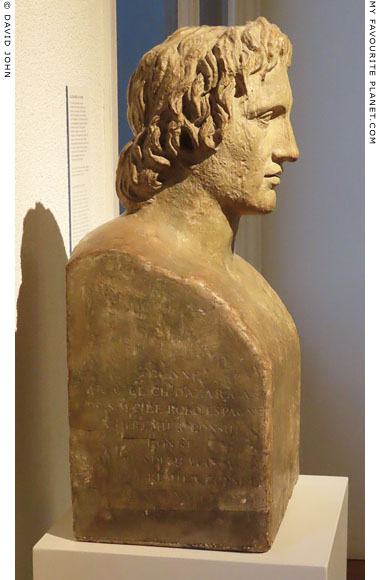

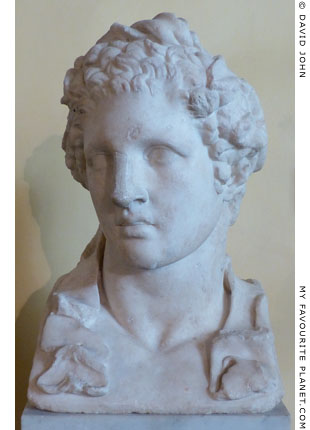

A modern plaster copy of the "Azara Herm",

viewed from the left side on which is an inscription

in French recording Azara's gift of the sculpture to

Napoleon, and the latter's donation to the Louvre.

Part of the University of Amsterdam's extensive

collection of plaster casts of ancient sculptures.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 16073. |

|

| |

The herm and the type of similar portraits of Alexander are named after the Spanish diplomat José Nicolás de Azara (1730-1804), who while ambassador in Rome funded the archaeological excavation of a villa at Tivoli. It was found in 1779 among a number of ancient sculpture portraits of famous men. Later, when ambassador to France, Azara gave it as a diplomatic gift to Napoleon who donated it to the Louvre in 1803. The lips, nose, eyebrows and lower part of the herm bust have been restored, but unlike many other sculptures found in Italy, it has not been over-restored or polished.

This was the first sculpture identifiable as a portrait of Alexander the Great discovered in modern times, and was particularly significant because of the inscription on the front of the herm.

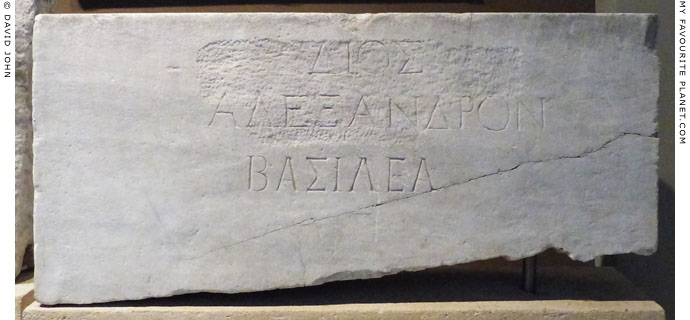

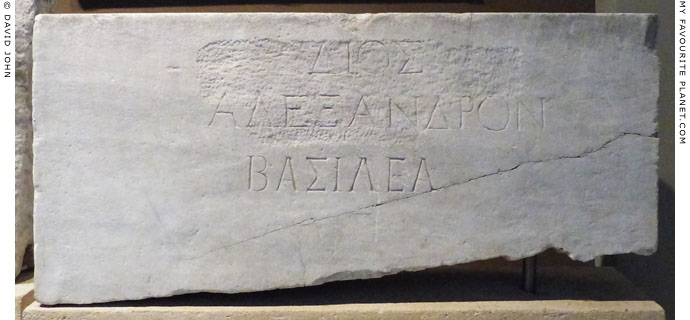

AΛEΞANΔPOΣ

ΦIΛIΠΠOY

MAKEΔ

Alexander, son of Philip, Maced[onian]

Many ancient busts unearthed since the Renaissance have such inscriptions, either ancient or added following their discovery, sometimes with an incorrect identification of the subject. However, scholars appear to be confident that this inscription is genuine and that the bust is a portrait of Alexander based on a Hellenistic original. This has led to the identification of several other heads as portraits of Alexander.

A longer modern inscription, written in Latin on the right side (to the viewer) of the herm bust records its discovery and restoration.

ALEX・M | SIGNVM・IN・TIBURTINO | PISONVM・EFFOSSUM | MDCCLXXIX | IOS・N・AZARA・REST・C

(This representation of) Alexander the Great, discovered in the Pisoni (Villa) in 1779, was restored thanks to Joseph Nicholas Azara. |

|

| |

|

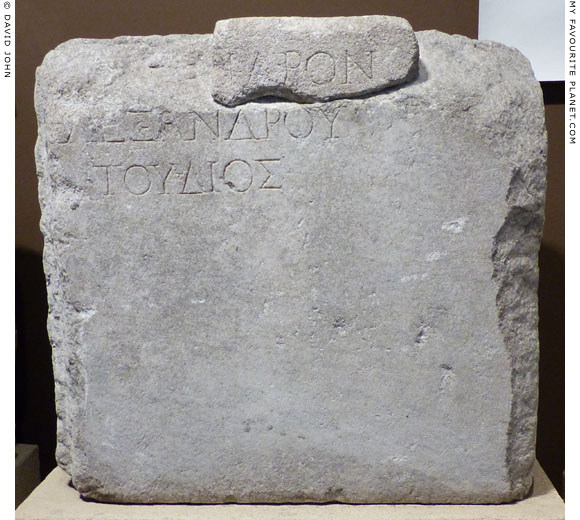

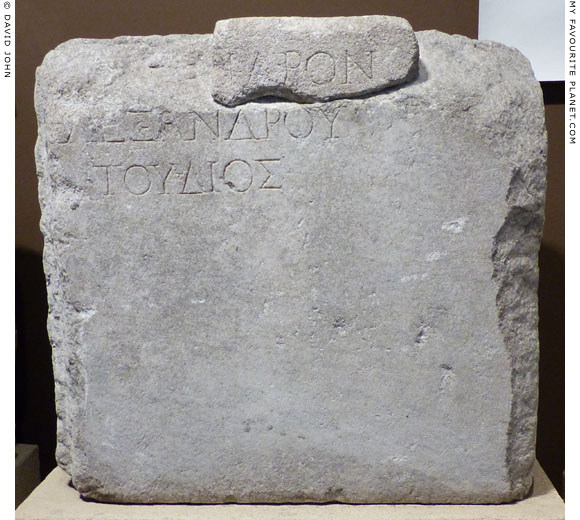

An over life-size marble statue of Alexander the Great, wearing a himation (cloak) around his

left shoulder and lower body, and with his left hand holding the handle of his sheathed sword.

Mid 3rd century BC. Height 190 cm. Excavated in 1895 by K. Buresch at the sanctuary

of Meter Sipylene (Kybele), on the slopes of Mount Syplos, Magnesia ad Sipylum, Lydia

(Manisa, western Turkey). Found with a marble base inscribed with a dedication to

Meter Sipylene, the local mother goddess, and the signature of Menas of Pergamon:

Μηνᾶς Αἴαντος Περγαμηνὸς ἐποίησεν

(Menas Aiantos Pergamenos epoisen)

Menas of Pergamon, son of Aias, made [it]

A date of early 2nd century BC has been claimed for the statue,

based mainly on the letter forms of the inscription. (Margarete Bieber,

The portraits of Alexander the Great, page 393. See details below.)

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 709. Cat. Mendel 536.

Base with the signature of Menas. Inv. No. 744. Cat. Mendel 537. Inscription TAM V,2 1358.

See: Gustave Mendel (1873-1938), Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines,

Tome Second, pages 249-254. Musée Impérial, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1914. |

|

| |

|

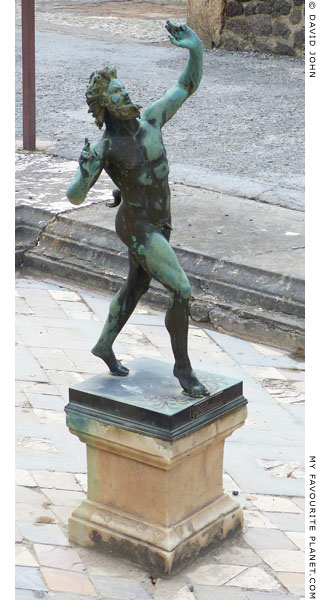

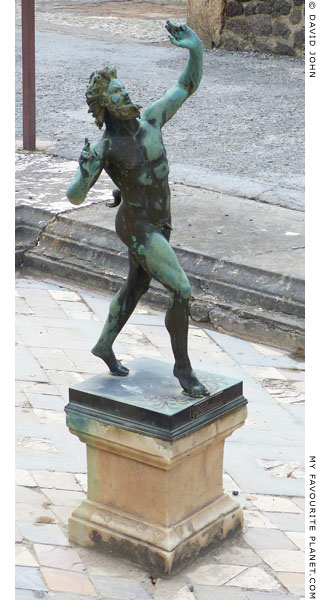

Marble statuette of Alexander the Great as the god Pan.

From Pella, Macedonia. Around 300-270 BC. Height 37.5 cm.

Pella Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. ΓΛ 143.

The figure has two small horns projecting from the top of the head, pointed ears and a goat's tail, in imitation of the rustic half-goat deity Pan, who was popular in Macedonia. It is presumed that the statuette had cloven hooves which are now missing.

Pliny the Elder ( Natural History, Book 35, chapter 36) wrote that the painter Protogenes, who painted a portrait of Aristotle's mother Phaestis, was advised by the philosopher to paint the exploits of Alexander the Great "as being certain to be held in everlasting remembrance". He appears to have ignored this advice but later painted depictions of Alexander as Pan. |

|

| |

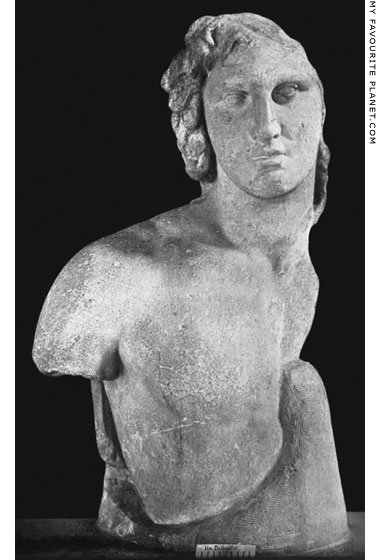

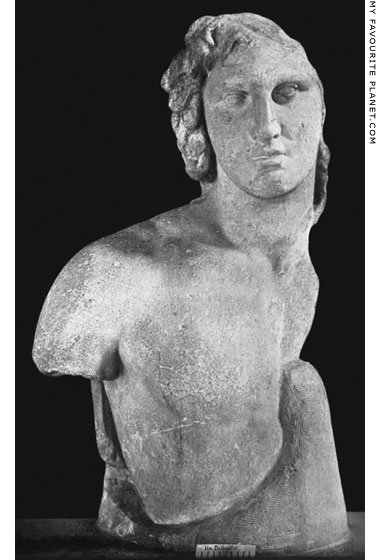

Fragment of a marble statuette of Alexander the Great from Priene.

200-150 BC. Discovered in Priene, Ionia (near Güllübahçe, Turkey) in 1895.

Height 31.6 cm (without arm 28 cm), height of head 12 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1500.

|

Discovered among other sculptures, terracotta figurines and objects associated with religious sacrifice, in the "House of Alexander the Great", during excavations directed by the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand (1864-1936) from 1895 to 1899. The house is in a residential area near the western gate of Priene, east of the temple of Kybele (see photo and map below). It is thought that Alexander may have resided there during his stay in Priene during the siege of Miletus in 334 BC. It is also believed to have been used as a hieron (shrine for a deified hero) dedicated to Alexander after his visit, with the northern hall of the building, in which the statuette was found, as the cult room. An inscription from the Sacred Stoa in the agora of Priene, dated to before 130 BC, documents the renovation of an Alexandreion by private donations.

The statuette was acquired by the Berlin museums as part of the division of archaeological finds agreed between the Turkish and German authorities. A fragment of a sword hilt with fingers of a left hand (Inv. No. Sk 1500a), thought to belong to the statuette, is now missing.

See an inscription from Priene below, naming Alexander as dedicator of the temple of Athena Polias. |

|

|

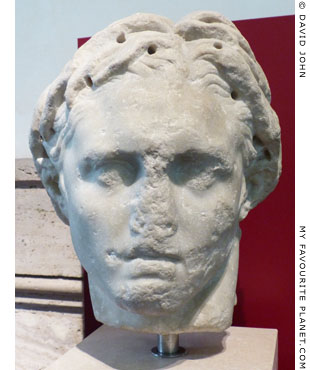

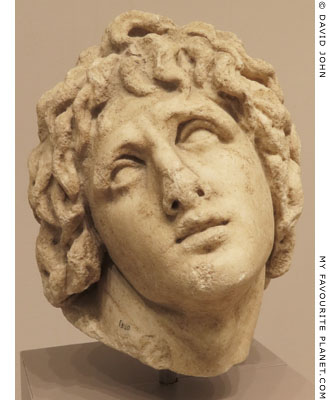

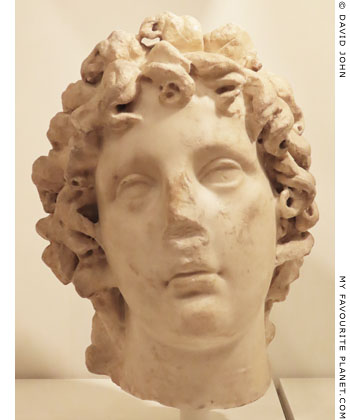

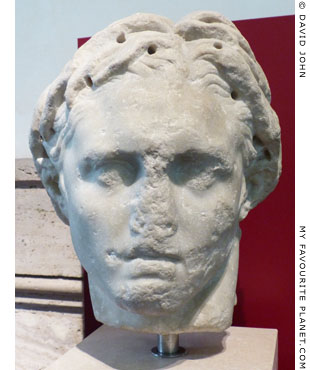

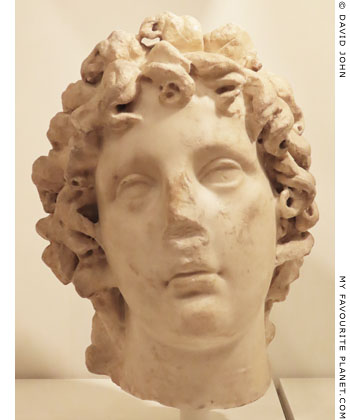

Marble head of Alexander the Great of

the "Acropolis type", found in 1886 near

the Erechtheion of the Athens Acropolis.

Thought to be an original work of the

Athenian sculptor Leochares, made

340-330 BC, perhaps after the Battle

of Chaironeia (338 BC) when Alexander

visited Athens at the age of 18. Either

this or "Erbach type" heads (see right)

represent the earliest surviving portraits

of Alexander. Pentelic marble.

Height 35 cm, width 23 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 1331.

It has been suggested that the statue

of Alexander in the Philippeion at Olympia

(see below) may have been a copy of

this sculpture. |

|

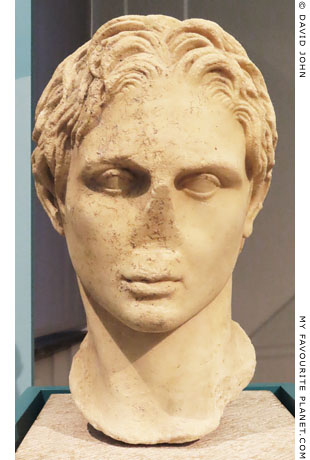

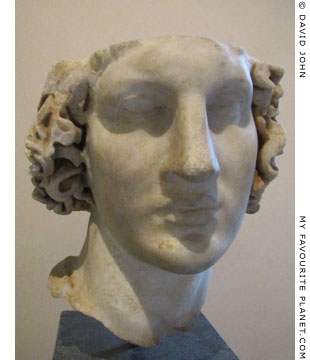

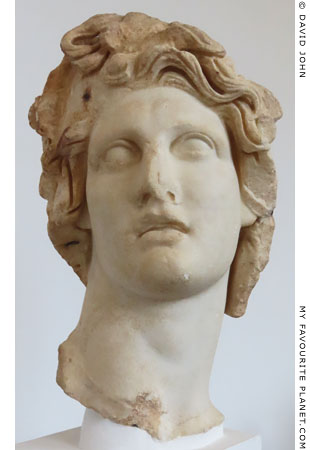

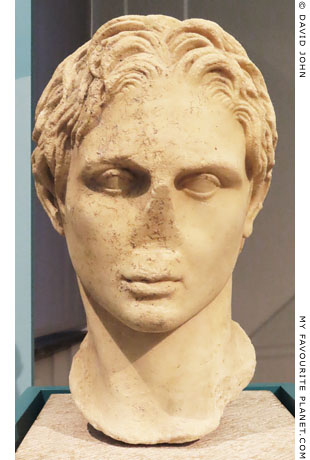

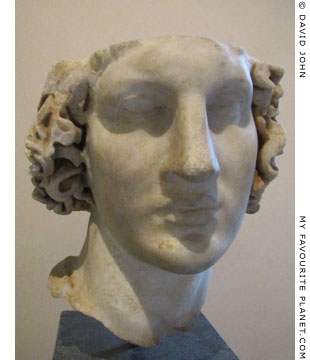

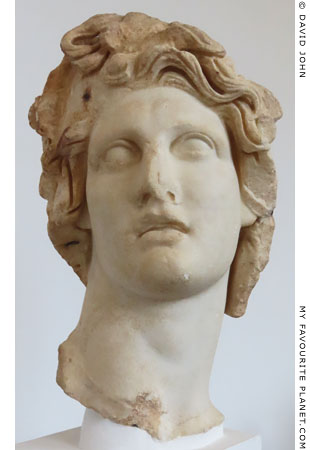

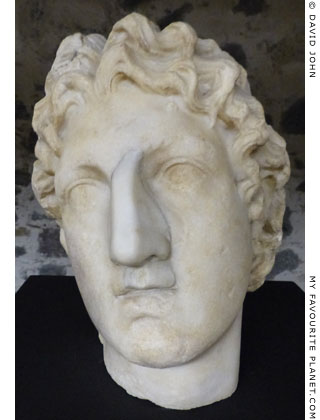

Head of Alexander of the "Erbach type".

Roman period copy of an original from circa

340-330 BC, made perhaps when Alexander

was about 16 years old. Acquired in 1874

in Madytos, Thrace (now Turkey).

The Erbach type is named after the head

found in 1791 at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, now

in Schloss Erbach, Germany, Inv. No. 642.

Also known as the "Acropolis-Erbach type"

due to the similarity to the head from the

Athens Acropolis (photo left).

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 329. |

|

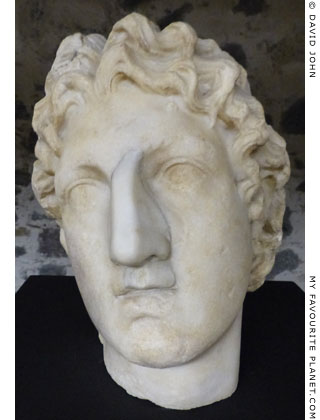

Marble head of Alexander the Great,

found in 1900 among rubble above the

north hall of the Lower Agora in Pergamon.

The head, along with the rubble, may have

fallen from a building uphill from the agora, perhaps the gymnasium.

1st half of the 2nd century BC. Height 42 cm.

According to one theory, this may be the

head of a giant from the Gigantomachy

frieze of the Great Altar of Zeus.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 1138 T. Cat. Mendel 538.

See Pergamon gallery 2, page 2. |

|

| |

Marble head of Alexander the Great found

at Volantza, near Olympia, Elis, Greece.

Hellenistic, circa 200 BC. Perhaps a copy

of a portrait by Lysippos. Height 37 cm.

The village of Volantza (Βολάντζα) was

renamed Alfeiousa (Αλφειούσα) in 1927,

and may be the location of ancient Bolax

(Βώλαχ), a town of Triphylia in Elis. It is

located south of the river Alpheios (Αλφειός)

and the road between Pyrgos and Olympia,

around halfway between the two places.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. Λ 246.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the

History of the Olympic Games of Antiquity,

Olympia. No. 399. |

|

Marble head of Alexander the Great.

Parian marble. 1st century BC.

Found in the portico of the temple

of Hercules, Tivoli, near Rome.

The holes around the top of the head

indicate the attachement of a metal

crown. The find spot suggests that

Alexander was assimilated to

the worship of the god Hercules.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 124507. |

|

| |

Marble head of Alexander the Great, known

as the "Schwarzenberg Alexander" after

the previous owner, Austrian archaeologist

and collector Erkinger von Schwarzenberg,

who purchased it at Christie’s in 1962. Said

to have been found in Tivoli, near Rome.

In 1967 he wrote the first account of the

head, arguing that it is from a copy of a

portrait staue of Alexander with a lance by

Lysippos, mentioned by Plutarch (Moralia,

335F; 360D). This claim has been generally

accepted, [8] although other identifications

have since been suggested, including

Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontos.

Roman period, early 2nd century AD.

Height 35.5 cm. Slightly larger than lifesize.

Staatliche Antikensammlungen und

Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 559. |

|

Marble head of Alexander the Great

from Kyme (Namurt, Turkey). Found

during excavations by Demosthenes

Baltazzi in 1887 [9]. Height 43.5 cm.

At first thought to depict Apollo. The

holes drilled around the top of the

head have led to its identification

as Helios or Alexander-Helios.

Hellenistic, late 3rd century BC or,

according to other theories, circa

125-75 BC. also tentatively linked to

Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontos, in

the context of his war against Rome,

the First Mithridatic War 89–85 BC.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 388 T. Cat. Mendel 597. |

|

Part of a larger than lifesize marble head from

a statue, possibly of Alexander the Great.

Late 4th century BC.

Kos Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

A marble head of Alexander the Great

found in 1904 in the Asklepieion of Kos.

Hellenistic, circa 150 BC. Height 31.5 cm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 1524 T. Cat. Mendel 539. |

| |

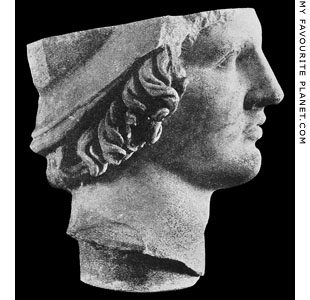

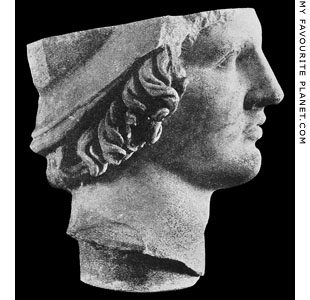

The larger than lifesize head was found on 19th September 1904 during excavations by the German archaeologist Rudolf Herzog (1871-1953) in the Asklepieion of the Dodecanese island Kos (see Asklepios). It was uncovered on the upper terrace of the sanctuary, at the east side of Temple A, near its southeast corner. Directly after its discovery, the head was taken to Istanbul. Three days later, on 22nd September parts of a marble statue of a draped male figure were found at the south side of the temple. It is not known whether the fragments belonged with the head since, although they were given the inventory numbers Nr. 251-3 and 257-260 of the Kos museum, they were not studied, and disappeared some time after.

The top of the head is broken off around the level of mid-forehead. He originally wore a helmet, part of which can still be seen at the back of the head (see photo, right). A reconstruction model made in Berlin (see photo, below right) showed him with an anachronistic Corinthian helmet perched on his head in the manner of Classical portraits of Greek generals such as Pericles (see Kresilas). This was defended by the German-American archaeologist Magarete Bieber (1879-1976), who cited the marble nude statuette of Alexander from Gabii, Latium (Flavian period, 69-96 AD), now in the Louvre, showing him wearing a Corinthian helmet. A number of scholars were sure that the head - and presumably the helmet - belonged to the statue.

See:

Magarete Bieber, Ein idealisiertes Porträt Alexanders des Großen. In: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Band 40 (1925), pages 167-182. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin und Leipzig, 1926. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. Photos of the head and the reconstruction, right, Figs. 3 and 5.

Margarete Bieber, The portraits of Alexander the Great. In: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 93, No. 5 (November 30, 1949), pages 373-421 + 423-427, particularly pages 391-392, figs. 49-50 and 51-52. At jstor.org.

Magarete Bieber commented that the head "seems to represent Alexander as saviour" (Σωτειρα, Soteira), and in the former article (Jahrbuch, 1925) rejected suggestions that it may be a portrait of one of Alexander's successors (the Diadochi), such as Mithradates VI (see above), or even the mythical doctor Machaon, son of Asklepios. She also speculated that it may have belonged to a statue mentioned in a lost work of the second century BC Greek poet and physician Nikander of Colophon (Νίκανδρος ὁ Κολοφώνιος):

"Another idealized portrait of Alexander from the island of Cos, now in Constantinople (Istanbul), about one-third more than life-size, seems to represent Alexander as saviour. This head was found on a terrace dedicated first to Apollo and later to Asklepios. With it were found fragments of a statue to which it belonged, now lost. It was probably the one beheld in the second century by Nikander, as reported by Karystios of Pergamon (in Athenaeus XV, p. 684 E), who saw the ambrosia plant, a symbol of immortality, growing on the head of the figure. Such a plant might well have taken root in the eye opening of the now lost helmet." (page 391)

The lost passage of Nikander was quoted by the late second century BC Greek grammarian Karystios of Pergamon (Καρύστιος) in his Historical Commentaries (or Historical Notes, Ἱστορικα ὑπομνήματα), also now lost, but passed on to us by Athenaeus of Naucratis (Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης), writing in the second - third century AD.

"There is also a flower spoken of under the name of ambrosia by Carystius, in his Historical Commentaries, where he says: 'Nicander says that the plant named ambrosia grows at Cos, on the head of the statue of Alexander.' But I have already spoken of it, and mentioned that some people give this name to the lily."

Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, Book 15, pages 680-692, chapter 32. At attalus.org.

In 1888, nearly two decades before the Asklepieion and the marble head were discovered on Kos, William Roger Paton (1857-1921) was on the island "hunting for inscriptions". In his The inscriptions of Cos, he referred to the passage by Athenaeus (including the quotation only in Greek as a footnote), and speculated on the statue's appearance:

"That there was a statue of Alexander at Cos, we happen to know, because of a curious story which was told of it. It was doubtless a bronze figure, in the manner of Lysippus, the hair having a certain dishevelled wildness: in one of its furrows, it seems, a seedling lily had found soil enough to grow in."

William Roger Paton and Edward Lee Hicks, The inscriptions of Cos, Introduction, page xxx. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1891. At the Internet Archive. |

The right side of the Alexander head

from Kos, showing the remains of the

helmet at the back. |

| |

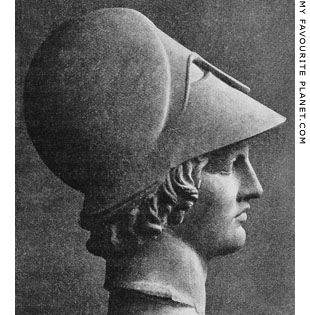

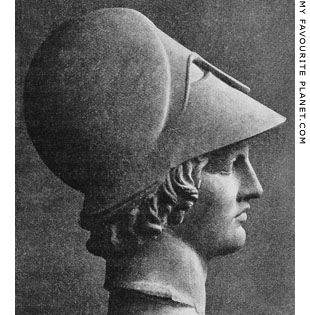

A reconstruction of the head from Kos,

with an added Corinthian helmet. Made

at the state museums, Berlin, under the

supervision of Professor Bruno Schröder. |

| |

| |

Colossal marble head of Alexander the Great.

Greek marble. Found in Piperno Vecchio

(ancient Privernum, Latium; today Priverno),

Lazio, central Italy in April 1831. Given to

the Capitoline Museum in 1839. Perhaps

a Hellenistic original. Greek marble.

Height 64 cm, with foot 81.5 cm. [10]

Galleria, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. MC532. |

|

"Male head after a Greek original

of the 4th century BC."

Sala del Fauno, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. MC701.

From the Albani Collection. |

|

| |

Marble head of Helios from Rhodes, in the

style of portraits of Alexander the Great.

Perhaps from the pediment of the sun god's

temple in the ancient city. Thought to have

been modelled on a work by Lysippos.

Holes were drilled around the hairline for

attaching metal rays of his solar crown.

Hellenistic period, 3rd century BC. Found

behind the "Inn of Provence" of the citadel

of the crusading Knights of the Order of

Saint John in Rhodes Old Town, perhaps

the location of the temple. Height 55 cm.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. E 49. |

|

Marble head of Alexander the Great

as the Greek sun god Helios (Ἥλιος).

1st century AD, "after a Hellenistic original of

the 3rd-2nd century BC" [11]. Height 58.3 cm.

The lower part of the front of the nose and

the bust have been restored. The identification

of the head as Alexander-Helios is based on

seven holes drilled around the top, thought

to have supported metal solar rays. Probably

one of the antiquities ceded by Pope Pius V

to the municipality of Rome in 1566. Taken to

the Louvre, Paris by Napoleon, following the

Treaty of Tolentino in 1791, and returned to

the Capitoline in 1816. In 1817 it was moved

from Stanza del Fauno (Hall of the Faun)

to the Sala del Galata (Hall of the Gaul,

then known as the Stanza del Gladiatore,

Hall of the Gladiator).

Sala del Galata, Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Inv. No. MC732. From the Vatican. |

|

| |

Head of Alexander the Great.

2nd or 3rd century AD, "copy after a

Greek original of the late 4th century BC"

attributed to Euphranor [12]. Pentelic

marble. Height 45 cm.

Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 157.

See also the "Alexander Rondanini"

statue below. |

|

Marble head, described by Kos museum

labelling as a "wounded warrior".

Hellenistic period, 2nd century BC. Found

near the temple of Herakles Kallinikos,

in the ancient Agora of Kos.

Kos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Γ 3160. |

|

| |

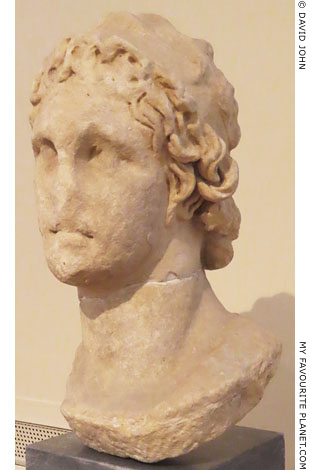

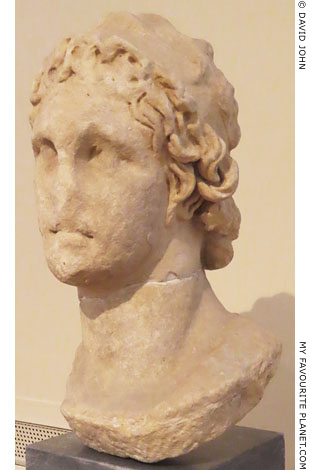

Marble head of a statue of Alexander the

Great from the Court of the Passage of

the Theoroi, at the northeast edge of

the agora of Thasos, Greece.

2nd century AD. Thasian marble. Height 41 cm,

width 30 cm, depth 29 cm.

The findspot is above the foundations of a late

4th century BC temple, which may have been

an Alexandreion. Thasos was one of the first

cities to worship Alexander as a god. An

annual Alexandreia festival (Ἀλεξάνδρεια)

was held there on his birthday. [13] This

head features one of the most obvious

examples of the "anastole" hairstyle

characteristic of several portraits of Alexander.

Thasos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ3719. |

|

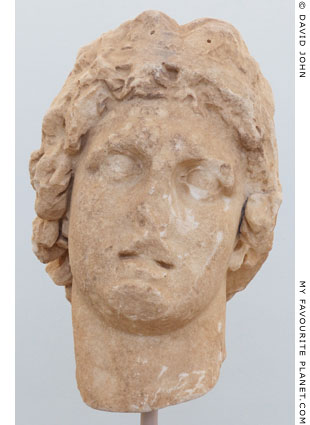

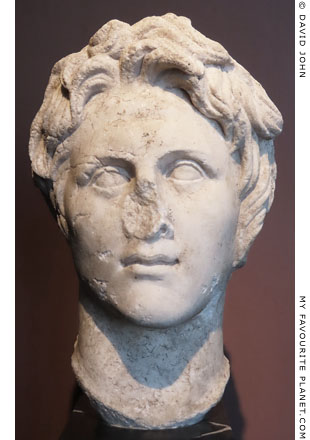

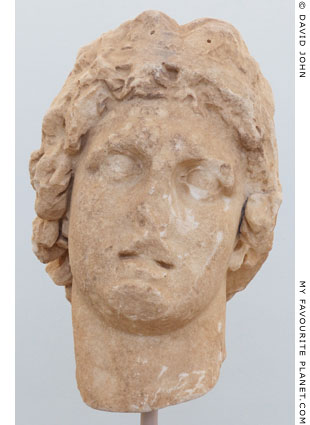

Marble head of a young man of

the type of Alexander the Great.

Mid 2nd century AD. Provenance unknown.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. MΘ 22117.

Purchased at an auction at Christie's,

London in 1996 by the Greek Ministry

of Culture, and donated to the museum. |

|

"Head of a man with characteristics

of Alexander the Great."

Marble. Smaller than life-size. Roman

period? Found on the Mon Repos estate,

Corfu, in the area now known as

Palaiopolis (Παλαιόπολης, Old City), site

of the ancient city Korkyra (Κόρκυρα).

Mon Repos Museum, Corfu. |

|

| |

Plaster cast of the marble head of Alexander

the Great in the British Museum.

University of Leipzig Museum of Antiquities.

Inv. No. G 30.

The original is from Alexandria, Egypt.

2nd - 1st century BC. Height 37 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1872,0515.1

(Sculpture 1857). Acquired in Alexandria, 1872. |

Plaster cast of a "head of the type

of Alexander the Great (?)".

Perhaps 1st century AD. The original was

discovered during excavations at Medinet Madi,

Egypt, 1935-1939 by the papyrologist Achille

Vogliano (1881-1953) of the University of Milan.

Medinet Madi, in the southwestern Fayum

region of Egypt, was known to the Greeks as

Narmouthis (Νάρμουθις). During the Ptolemaic

period a chapel (or cenotaph) for the worship

of Alexander was dedicated there.

CMA Milano. Inv. No. E 0.9.40449.

Temporary exhibition: Milano in Egitto: Gli scavi

di Achille Vogliano nel Fayum (Milan in Egypt:

The excavations of Achille Vogliano in Fayum),

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan,

17 May - 15 December 2017,

extended until 13 May 2018.

Unfortunately, the museum provides little

information about this head, and no

indication of the location of the original. |

Gilded bronze head of Alexander the Great.

2nd century AD. Height 18.5 cm.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 66177.

From the Kircherian Museum. |

|

| |

|

|

|

A marble head of Alexander the Great in Dresden,

known as the "Dresselscher Kopf" (Dressel Head).

Thought to be a Roman period copy of a Greek original

of around 325-300 BC by Lysippos. it was acquired in

Rome in 1885 from the Dressel Collection. Height 39 cm.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 174.

Source: Anton Hekler, Greek and Roman portraits, plate 60.

G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1912. At the Internet Archive.

Until recently, the head had not been on display since 2002.

See below. |

|

| |

|

|

|

A marble head of Alexander the Great in Dresden,

known as the "Dresselscher Kopf" (Dressel Head).

1st or 2nd century AD. Thought to be a Roman period copy of a Greek

original of around 325-300 BC by Lysippos. Acquired in 1885 from the

collection of Heinrich Dressel in Rome. Thasian marble. Height 39 cm.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 174.

Now on display again in the recently opened Antikenhalle

(Hall of Antiquities) of the Semperbau, Dresden. |

| |

Part of a copper alloy statuette from Egypt depicting

Alexander the Great as Cosmocrator Helios.

Cosmocrator Helios was one of the syncretic deities introduced by Greek rulers

of Egypt as part of the Hellenization of Egyptian religion and the religious-

philosophic system of astrology developed during the Hellenistic period.

The name Cosmocrator (Κοσμοκράτωρ, Kosmokrator) has been interpreted as

ruler of the known world (kosmos) or master of the universe. Roman emperors

were also depicted as Cosmocrator Helios, the incarnation of imperial power.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Egyptian Collection, Inv. No. X198. |

| |

|

|

|

A small marble head of a statuette of Alexander the Great.

From Alexandria, Egypt. 200-175 BC. Height 13 cm, width 8.2 cm, depth 9 cm.

A hole in the top of the head is thought to have been for the attachment

of a crown or emblem of an Egyptian deity. On the right is a plaster cast

of the head with a reconstruction of a divine emblem.

University of Leipzig Museum of Antiquities. Inv. No. 99.037.

Donated by E. P. Warren and J. S. Marshall, 1908.

A similar small head of Alexander head with a star symbol attachment,

referred to as "Alexander as Kosmokrator", is in the National Museum

of Denmark, Copenhagen. See the photo at livius.org. |

|

|

Marble head of a colossal statue of

Demetrios Poliorketes (Δημήτριος

Πολιορκητής, Demetrios the Besieger, 337

-283 BC), king of Macedonia (294-288 BC),

in the style of portraits of Alexander the

Great. He originally wore an attached

diadem and goat's horns on the forehead.

3rd century BC. From the Dodekatheon,

(Δωδεκάθεον, Temple of the Twelve

Olympian Gods), Delos. Height 54 cm.

Delos Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. A 4184 + A 197. |

|

Marble portrait head from a statue of a

ruler wearing a diadem. Perhaps Alexander

the Great or Mithridates, king of Pontos.

125-100 BC. Pentelic marble. From

the Sanctuary of Apollo, Delos.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 429. |

|

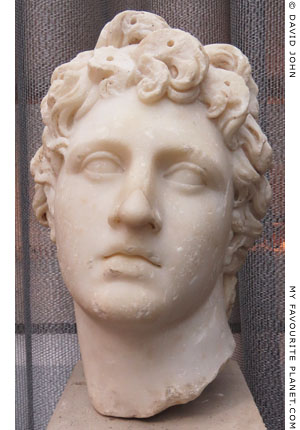

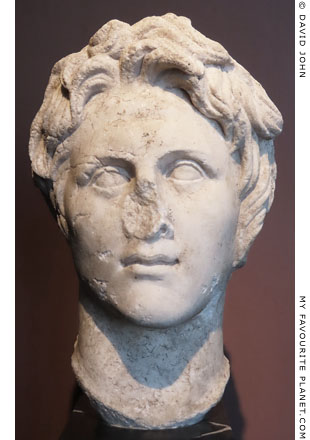

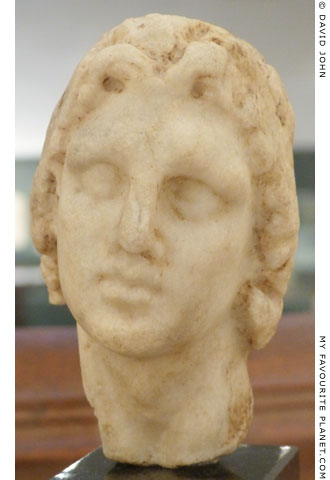

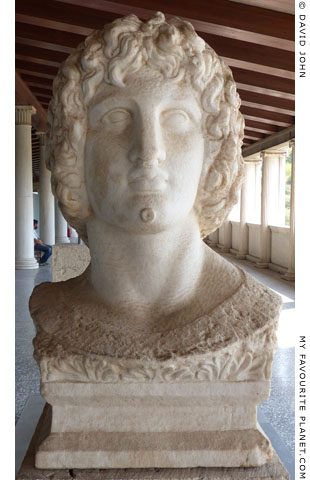

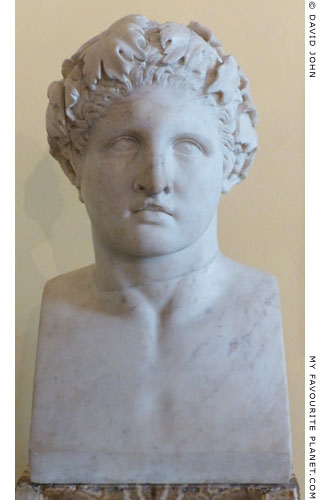

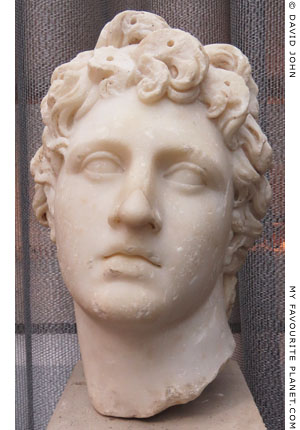

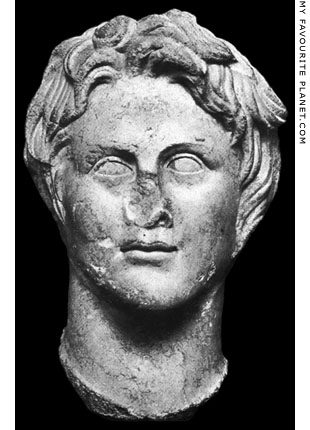

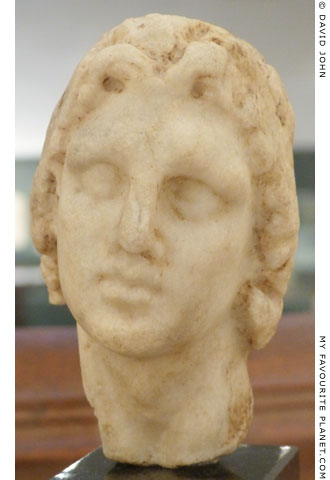

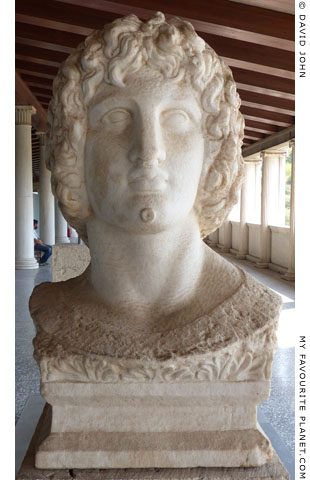

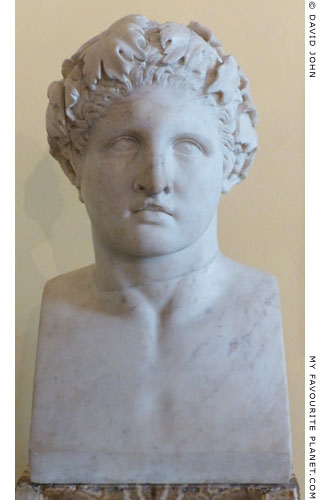

Marble head thought to be a portrait

of Alexander the Great.

175-200 AD. Found in the area of the ancient

agora of Thessaloniki. Perhaps part of a group

of cult statues of the family of Alexander in

the city. The work was previously described

as "head of a woman".

The style of representation, with almost

feminine features and long wavy hair, parted

in the centre, are reminiscent of the depiction

of Alexander on the earlier Macedonian coins

of the Roman Republican period (see above),

and of Medieval or Renaissance sculptures.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

Bust of Alexander or Eubouleus, a god

connected with the Eleusinian Mysteries

(see Demeter and Persephone part 2).

Unfinished 2nd century AD copy of a work

of the 4th century BC. Discovered in 1959

by Dorothy Burr Thompson in the Athens

Agora. Thasian marble. Height 61 cm, height

of base 12 cm, width (at shoulder) 39 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 2089.

A similar marble bust thought to depict

Eubouleus, found in Eleusis and dated

to around 330-320 BC, is in the National

Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 181. |

|

Bust of the sun god Helios with drilled holes

for a solar-ray crown. When first discovered

it was thought to be possibly a portrait of

Alexander. It has been described as being

"related to the so-called Eubouleus type".

2nd century AD. Found 31 July 1970 during

excavations by John McK. Camp II in a well

(Deposit P 21:2) in the east colonnade of the

peristyle of a large late Roman complex

known as Roman House H, on the slope of

the Areopagus, south of the Athens Agora.

Pentelic marble. Height 52.3 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 2255.

Among other ancient objects found in

the well was a marble head of Nike. |

|

| |

Marble head, with reconstructed nose

and upper lip, thought to be a portrait

of Alexander the Great.

Museo Civico, Castello Ursino, Catania,

Sicily. From the Biscari Collection. |

|

"Fragment of a head in the style of

depictions of Alexander the Great."

Late 3rd century AD.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum,

Dresden. Inv. No. ZV 4032.

See also the "Dresselscher Kopf"

of Alexander in Dresden above. |

|

| |

Marble head "of a young god" in the style of

portraits of Alexander the Great. Perhaps Apollo.

Behind the prominent locks the hair around the

crown of the head is tied with a fillet (headband).

Around 150-200 AD. From the vicinity

of Naples, Italy. Height 26.5 cm,

width 20.0 cm, depth 20.0 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 1792.

Catalogue no. 94, pages 77-78, plate 43, a-c.

According to the Catalogue Inv. No. 1793. [14] |

Small ceramic head of Ptolemy I in the

style of portraits of Alexander the Great.

Early 3rd century BC. From Memphis,

Egypt. Height 5.9 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 7431. |

Terracotta votive head "with

features of Alexander the Great".

Hellenistic period, around 330-250 BC.

From Etruria, Italy. Height 28 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 3421. |

|

| |

Marble head in the style of portraits

of Alexander the Great, made to be

inserted into a statuette or bust.

3rd century BC. Provenance unknown.

Perhaps made in Greece, possibly

Athens. Half life-size. Height 16.2 cm,

width 8.9 cm, depth 10.5 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. APM 1613.

Catalogue no. 56, pages 51-52,

and plate 25, c-e [see note 14]. |

|

|

|

|

| |

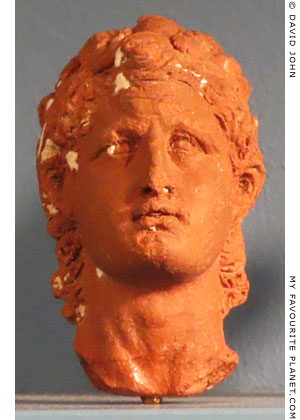

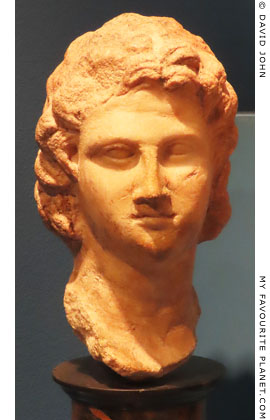

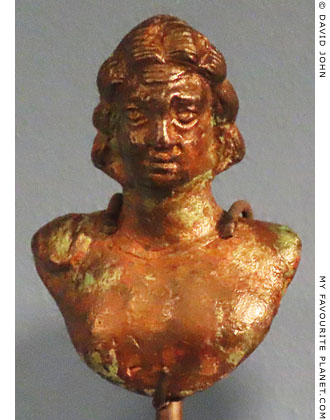

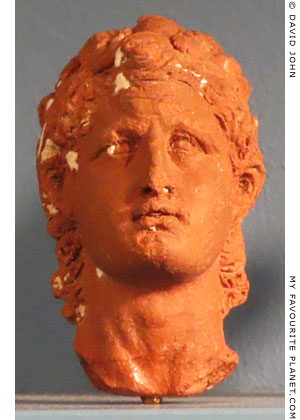

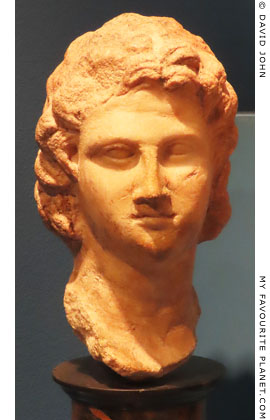

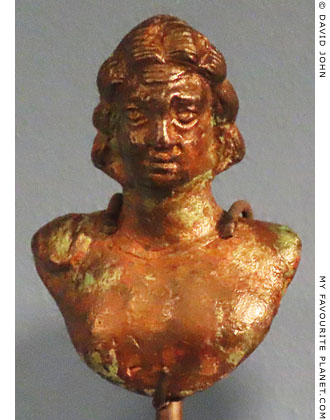

Two small marble heads and a bronze (?) bust in the style of portraits of Alexander the Great,

displayed unlabelled in the "Hellenistic Cabinet" of the Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. |

|

| |

Marble herm bust in the Palazzo dei

Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. |

|

Marble herm bust of a young beardless male

wearing a poplar crown. 1st-2nd century AD.

Perhaps derived from a statue of Herakles

by Skopas, 4th century BC. Found in 1876

on the Quirinal Hill, Rome. Pentelic marble.

Height 45 cm, width of herm (at base)

12.5 cm, length of herm (at base) 29.5 cm.

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline

Museums, Rome. Inv. No. S1133. |

| |

These two marble herm busts, now in the Sale Castellani of the Capitoline Museums' Palazzo dei Conservatori, have been placed either side of the bronze horse associated with Lysippos (see below). They are not labelled, and so far we have found no reference to them in the museum's online database. Another source identifies the left bust as Alexander without giving further details.

The bust on the right was briefly discussed in an article about the "Herakles of Skopas" written by Botho Graef in Rome in 1889. According to Graef the bust, first mentioned in Bullettino Municipale IV (1876), page 217.9, and another similar bust in the Capitoline Museums were derived from a stone statue of Herakles made by Skopas in the first half of the 4th century BC for the gymnasium in Sikyon, mentioned by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 10, section 1). This identification was challenged by, for example, Henry Stuart Jones, who suggested the subject may have been a marble statue of Dionysus by Skopas at Knidos (Κνίδος) in Caria, mentioned by Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4). It should be noted that neither Pausanias nor Pliny described the respective statues, so attempts to identify them remain pure speculation.

See:

Botho Graef, Herakles des Skopas und verwandtes. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung, Band 4, 1889, pages 189-226, particularly pages 190-191 and Tafel (plate) IX.

Henry Stuart Jones, A catalogue of the ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome: The sculptures of the Palazzo dei Conservatori (Volume 2 of 2, text; Volume 1 contains the plates), "Youthful male herm, so-called Scopaic Heracles", Sala degli Orti Lamiani No. 7, pages 130-131 and plate 47; similar bust, "Herm of a young Dionysus", Galleria No. 28, pages 90-92, plate 33. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1926. Both volumes online at Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

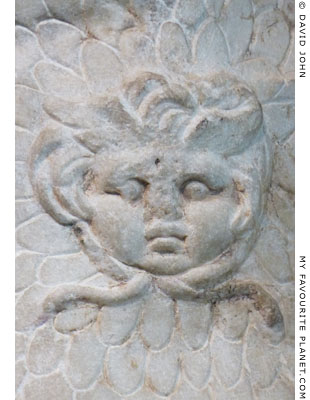

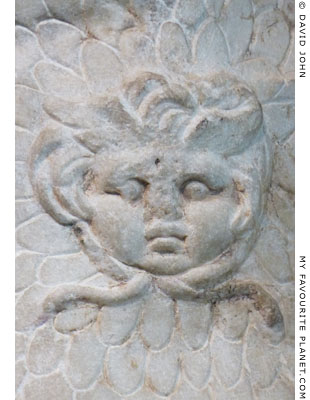

A colossal marble head, thought to be a Gorgoneion,

dated to the first half of the 2nd century BC, at the entrance

to the Veria Archaeological Museum, Macedonia, Greece.

The largest Gorgon head found in Greece, thought to have been attached to the northern

defensive walls of ancient Veria (Βέροια) as an apotropaic symbol to scare off attackers.

The features of the head, particularly the hairstyle, resemble those of Alexander the Great. |

| |

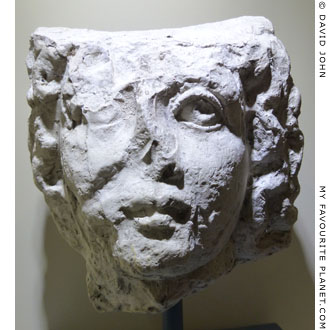

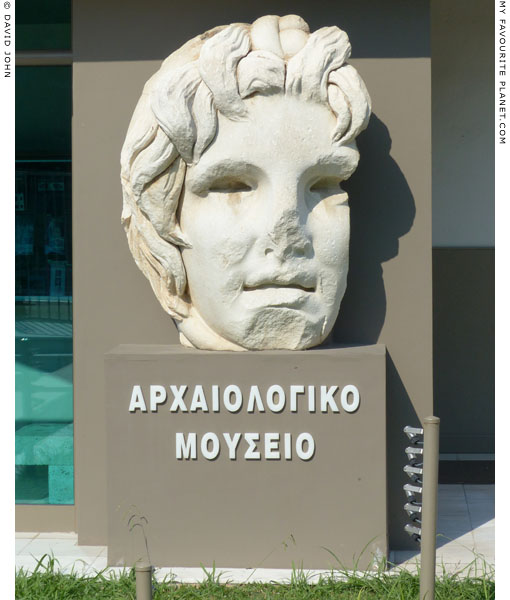

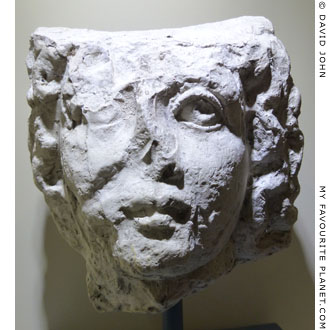

| New portrait of Alexander the Great found in Veria |

| |

A marble head, believed to be a portrait of Alexander the Great and dated to the 2nd century BC, has recently been rediscovered in the storerooms of the Veria Archaeological Museum. The battered head had been stored and forgotten among other finds recovered by archaeologists some decades ago at a nearby village, where it had been built into a wall in the 18th or 19th century. The find was first announced on Facebook on 31 July 2019 by Angeliki Kottaridi (Αγγελική Κοτταρίδη), Director of the 17th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities (prefectures of Imathia and Pella), the 11th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities and four local museums: the archaeological museums of Veria, Pella and Vergina (Aigai), and the Veria Byzantine Museum.

See: facebook.com/angeliki.kottaridi/posts/2578000048901128 (in Greek, with photo)

Now cleaned and restored, the head is due to be exhibited at the end of 2020 in the Museum of the Macedonian Royal Tombs in Vergina. I, for one, hope it will find a permanent home in the excellent Veria Archaeological Museum, which could do with such a "star" exhibit in order to attract more visitors. |

|

|

The "Inopos", a fragment of a marble statue

in the style of portraits of Alexander the Great.

Around 100 BC. From Delos. Height 95 cm.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 855 (MR 235).

Donated by the painter E. A. Gibelin, 1801.

|

The fragment, which includes most of the head and right side of the chest, was initially thought to depict the Delian river god Inopos (Ινωπος), but is now considered to be a Hellenistic ruler, either Alexander himself or Mithradates VI (see above).

It has been suggested that the statue may have been made by Alexandros of Antioch (or Agesandros of Antioch), the sculptor of the Venus de Milo.

Image source: Guy Dickens, Hellenistic sculpture, Fig. 20, page 26. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1920. At the Internet Archive.

See: Bust of Alexander the Great, known as the "Inopos", at the Louvre website. |

|

|

|

|

|

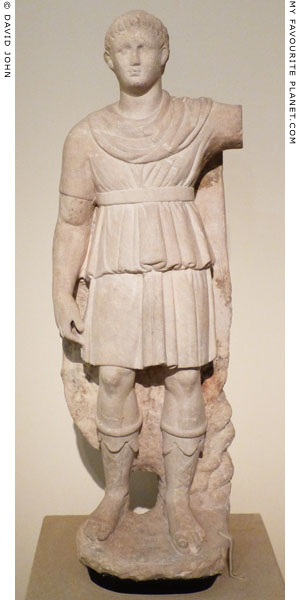

Marble statuettes of Hephaistion (left) and Alexander the Great from Egypt. Probably

1st century BC. Perhaps from a statue group erected in Alexandria in Hephaistion's honour.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Egyptian Collection. Invoice numbers 45 and 44.

|

|

Formerly in the Demetrios Collection, they are often referred to as the "Demetrio Hephaistion" and "Demetrio Alexander". The figures stand in mirrored contrapposto poses, each with the opposite arm raised. Each wears a chlamys, chiton, zona belt and open-toed, lace-up boots. It is tempting to speculate that the figures were placed next to each other, each holding a horse, in the manner in which the twin divine horsemen heroes Castor and Pollux (the Dioskouri) were represented in sculptures and coins.

See also:

A marble head from Kyme below, thought to be a portrait of Hephaistion.

A Hellenistic double hero relief from Miletus, on Pergamon gallery 2, page 10.

A Hellenistic relief from Pella depicting Hephaistion, on Pella gallery page 17. |

|

| |

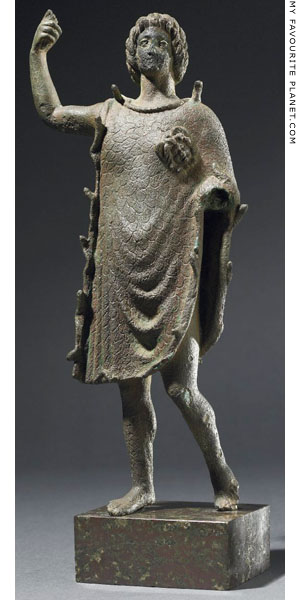

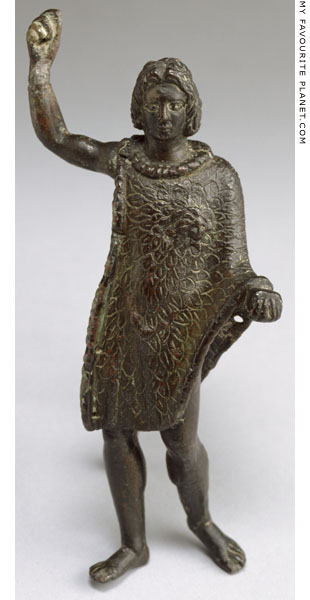

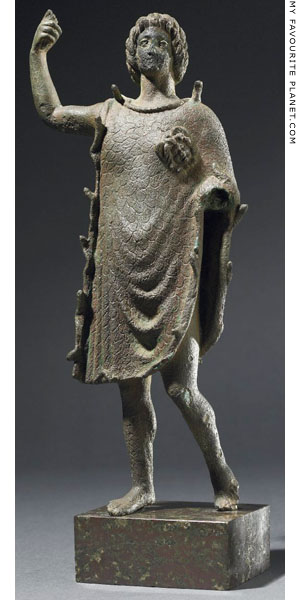

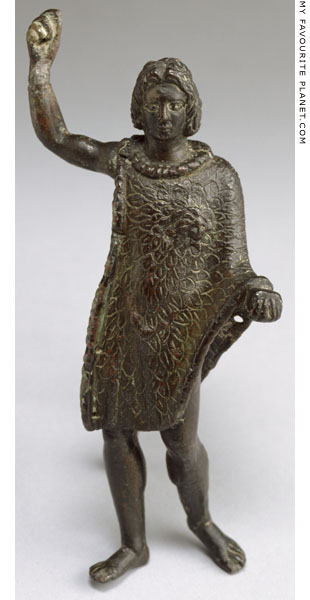

Copper alloy statuette from Egypt depicting

Alexander the Great as a Roman general,

wearing the Gorgoneion on his cuirass.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Egyptian Collection, Inv. No. 2577. |

|

|

|

|

Marble statuette of Alexander the Great. Around 150 AD.

Height 103 cm, width 32 cm, depth 24 cm. Height of statue 95 cm, head (with neck) 17.8 cm.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 304.

|

|

The statuette belonged to the French Cardinal Melchior de Polignac (1661-1742), who lived in Rome 1724-1732, and commissioned the sculptors Lambert-Sigisbert Adam, Edme Bouchardon and Pierre Lestache as restorers for objects in his collection of Roman antiquities. The statuette may have been at first restored as Archangel Michael during this time. It was restored again as a Roman emperor, probably after the cardinal took it with him on his return to Paris.

The entire collection was purchased by King Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great), and the statuette was first mentioned as Alexander in 1742, when it stood in the oval dining room of Schloss Charlottenberg, Berlin. Later it was placed in the "Saal der Hermen" (Hall of the Herms) in the Altes Museum, as No. 398 (number on the base). |

|

|

|

|

|

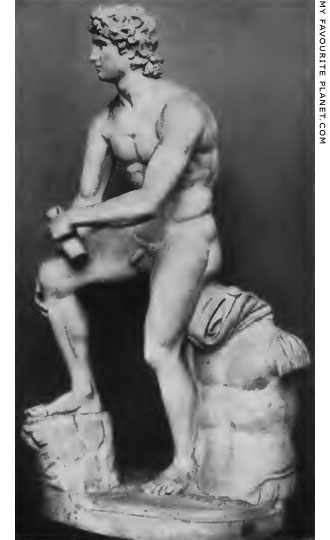

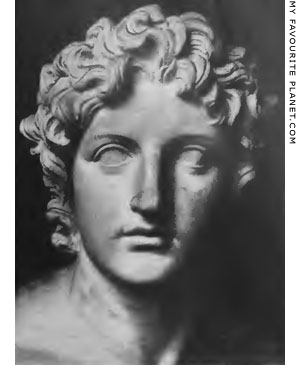

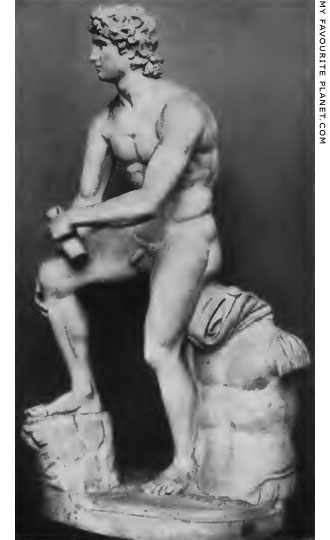

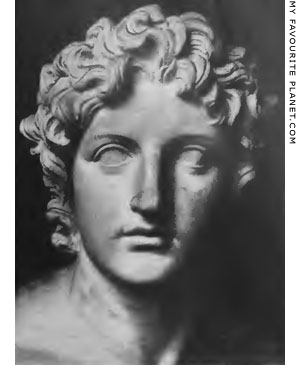

The so-called "Alexander Rondanini" marble statue, thought to represent Alexander the Great.

Right: photo of the head of the statue from a plaster cast.

|

|

The life-sized statue was named the "Alexander Rondanini" due to the fact that it was part of the large private collection of antiquities kept by the wealthy Rondanini family at the Palazzo Rondanini (now Palazzo Rondanini-Sanseverino) in the centre of Rome, from where it was purchased for the Glyptothek museum, Munich in 1814.

Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. GL 298. Height 1.78 metres.

It was first identified as a portrait of Alexander in 1767 by the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), but this identification remains a subject of debate. According to one theory it may be part of a Roman period copy of a bronze statue group by Euphranor of Corinth (Ἐυφράνωρ, circa 390-325 BC), mentioned by Pliny the Elder, depicting King Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander in four-horse chariots.

"He [Euphranor] also executed some brazen chariots with four and two horses, and a Cliduchus of beautiful proportions; as also two colossal statues, one representing Virtue, the other Greece; and a figure of a female lost in wonder and adoration: with statues of Alexander and Philip in chariots with four horses."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Other scholars believe it may be a Roman copy of a late Hellenistic portrait of Alexander as Achilles, or perhaps of Achilles himself. According to one theory, the marble head of Alexander the Great in the Barracco Museum, Rome (see above) may also be a copy of the statue by Euphranor.

Image source: Ludwig Curtius (1874-1954), Die antike Kunst, Band II, page 363, figs. 546 and 547. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Athenaion M.B.H., Wildpark-Potsdam, 1926.

See also:

Ralf von den Hoff, Der "Alexander Rondanini". Mythischer Heros oder heroischer Herrscher?, in Münchner Jahrbuch für bildende Kunst, 48 (1997), pages 7-28.

Olga Palagia, Euphranor. Brill, Leiden, 1980. |

|

|

Sculpted marble metope with a relief of Helios in a quadriga (four horse chariot) rising out of the sea.

The sun god's features, poise of the neck and hairstyle resemble portraits of Alexander.

Hellenistic period, 300-280 BC. The best preserved metope from the temple of Athena Ilias,

Ilion (Troy), northwest Anatolia; today Hisarlik, around 30 km southwest of Çanakkale, Turkey.

Found in 1872 during Heinrich Schliemann's first excavations of 1871-1873 (his second excavations

were in 1878-1879). Height 85.8 cm; width of triglyph block 201.2 cm; width of metope 86.3 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sch 9582; L 21.1.

On loan from the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Berlin. |

| |

Detail of the metope from Troy with the relief of Helios.

|

The metope is from the architrave at the east end of the north side of temple of Athena Ilias, the patron goddess of Ilion (Ancient Greek, Ἴλιον, Ilion, or Ἴλιος, Ilios, and Τροία, Troia; Latin, Troia and Ilium). The Doric temple was built at the beginning of the 3rd century BC by Lysimachus, king of Thrace and Macedonia (see History of Pergamon), allegedly in fulfilment of the wishes of Alexander the Great. It is thought that, as at the Parthenon in Athens, the row of metopes continued with battle scenes, perhaps from the Trojan war, and ended with an image of the moon goddess Selene.

"The present city of Ilium was once, it is said, a village, containing a small and plain temple of Minerva [Athena]; that Alexander, after his victory at the Granicus, came up, and decorated the temple with offerings, gave it the title of city, and ordered those who had the management of such things to improve it with new buildings; he declared it free and exempt from tribute. Afterwards, when he had destroyed the Persian empire, he sent a letter, expressed in kind terms, in which he promised the Ilienses to make theirs a great city, to build a temple of great magnificence, and to institute sacred games.

After the death of Alexander, it was Lysimachus who took the greatest interest in the welfare of the place; built a temple, and surrounded the city with a wall of about 40 stadia in extent. He settled here the inhabitants of the ancient cities around, which were in a dilapidated state. It was at this time that he directed his attention to Alexandreia, founded by Antigonus, and surnamed Antigonia, which was altered (into Alexandreia). For it appeared to be an act of pious duty in the successors of Alexander first to found cities which should bear his name, and afterwards those which should be called after their own. Alexandreia continued to exist, and became a large place; at present it has received a Roman colony, and is reckoned among celebrated cities."

Strabo, Geography, Book 13, chapter 1, section 26. At Perseus Digital Library.

According to Plutarch (Life of Alexander, chapter 15) and Arrian (Anabasis of Alexander, Book 1, chapters 11-12), Alexander visited Ilion before, rather than after the Battle of Granicus, immediately following his crossing of the Hellespont into Asia (Anatolia) in May 334 BC. He visited the temple of Athena Ilias, made sacrifices at the supposed tombs of the Homeric heroes Achilles and Patroklos, and exempted the city from tribute (taxes).

Before Alexander's death in 323 BC, it was said that he made plans to rebuild the temple of Athena Ilias as the largest in the known world. At 16.4 x 35.7 metres, Lysimachus' peripteral temple, with 6 columns at each end and 12 along the sides, was far from being the largest or grandest, and to judge by the metopes, not particularly well sculpted; the building and sculptures probably depended on paint to create an impression.

Ilion was sacked in 85 BC by the Roman commander Gaius Flavius Fimbria during the First Mithridatic War (88-84 BC). In 20 BC Emperor Augustus visited the city and ordered repairs, including the restoration of the temple. Little remains of the temple today, since it has provided building material for local people over the centuries. |

|

Marble bust thought to be

a portrait of Lysimachus,

one of Alexander's generals

and successors.

Augustan copy (23 BC -

14 AD) of a 2nd century

BC Greek original.

National Archaeological

Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6141.

See:

Pergamon gallery 2, page 3. |

|

|

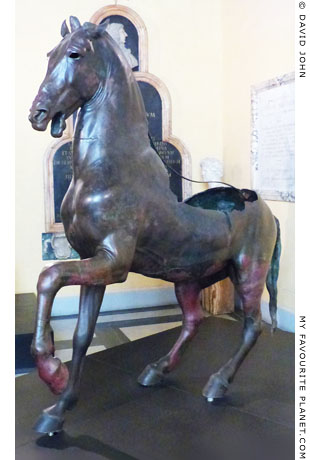

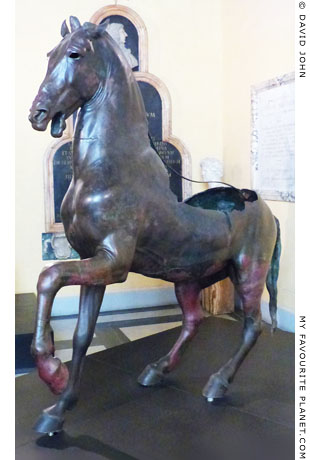

Bronze statuette of Alexander the Great on horseback from Herculaneum.

1st century BC. Found in around 15 fragments in October-November 1761, during

the Bourbon excavations, in a tunnel at the theatre, under the Casa dei Colli Mozzi,

Herculaneum, Campania, southern Italy. The rider's legs and right arm, and the horse's

legs were missing. It was restored over several years from 1762 in the Reale Fonderia

of Portici (the royal foundry of Naples), under the direction of Camillo Paderni, custodian

of the Real Museo Borbonico (Royal Bourbon Museum) in Naples. During the 1770s it was

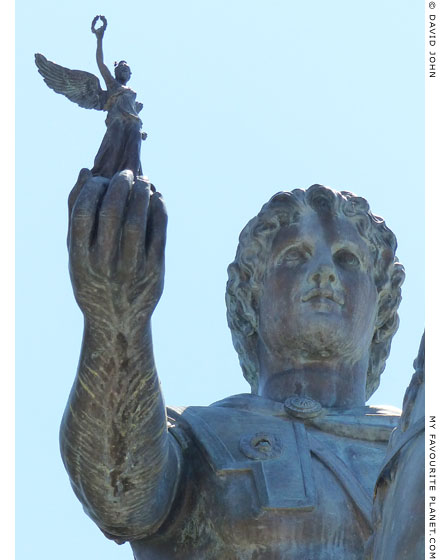

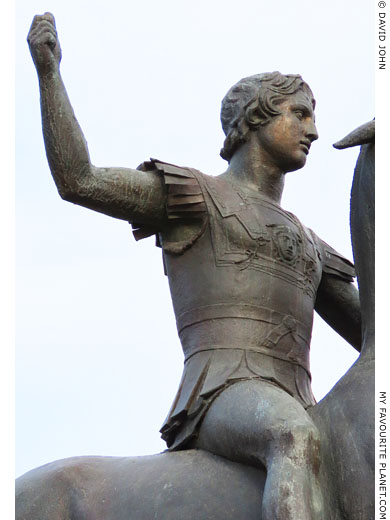

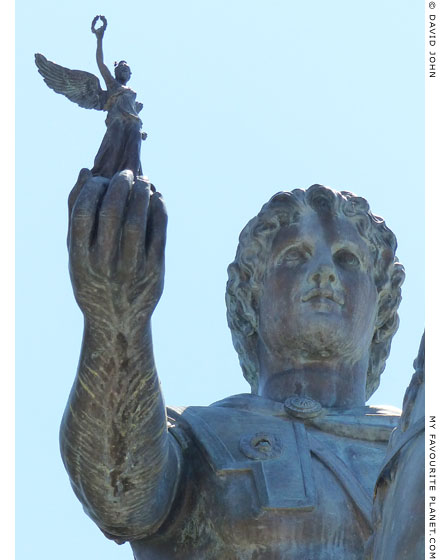

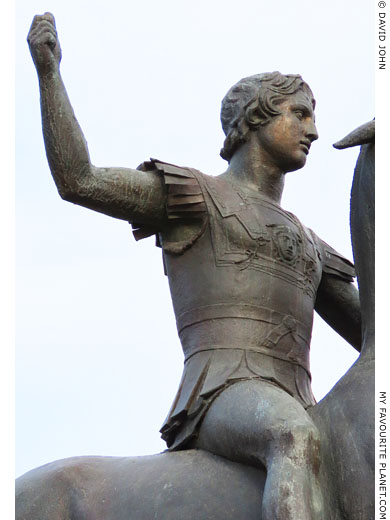

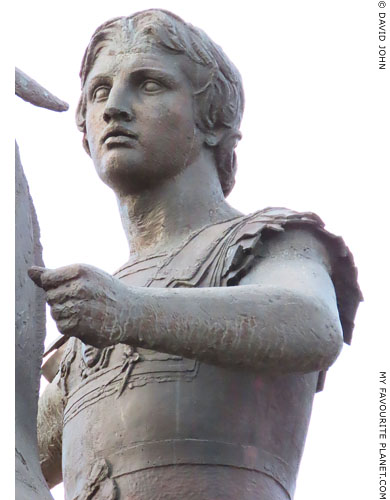

exhibited in the museum in Herculaneum, and first displayed in the Naples museum in 1820.

Height 48.5 cm, Length 47 cm, depth 29 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy. Inv. No. 4996.

|

One of a group of three similar cast bronze equestrian statuettes discovered in the theatre in Herculaneum. The other two are of an Amazon on horseback (Inv. No. 4999, see image, right) and a now riderless rearing horse (Inv. No. 4894).

This figure is thought to be a copy of a statue of Alexander the Great from a bronze equestrian group of 25 mounted figures (there may have been more figures in the work, perhaps depicting Persians), known as the Granikos Monument (or Granicus Monument). The group was commissioned by Alexander and made by the sculptor Lysippos (Λύσιππος) to commemorate members of Alexander's Companion royal guard, recruited from young Macedonian noblemen, who died at the Battle of the Granicus River (Γρανικὸς ποταμός) in 334 BC, and erected at Dion, Macedonia around 330 BC (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Book 1, chapter 16; Plutarch, Life of Alexander, chapter 16).

Alexander, with swept-back, wavy hair, wears a royal diadem, a short chlamys (cloak), a cuirass over a short chiton, and laced high military sandals. He rides without a saddle or stirrups, as the latter were unknown to the ancient Greeks. The rearing horse is thought to be his favourite steed Bucephalos (Βουκέφαλος, Ox-Head). The figure originally held a sword in his right hand, and reins in the left, probably both of silver. Other details of the statuette were also inlaid with silver foil, including the eyes of the rider and horse, the rosette fastening on right shoulder of the rider's cloak, and the mask on the horse’s breastplate.

The Battle of the Granicus River was the first of three major battles fought by Alexander during his ten year campaign in Asia against armies of the Persian King Darius III; the other two were at Issos (or Issus) in 333 BC and Gaugamela in 331 BC (see below). In each case his victory against superior numbers has been put down to his brilliant, innovative and unconventional tactics. These victories and his eventual complete defeat of the Persian Empire astonished the world and cemented his legendary status.

The Granikos Monument was recognized from antiquity not merely as a memorial to fallen soldiers but, perhaps more importantly, as part of Alexander's sophisticated propaganda campaign, aimed at convincing supporters and enemies - in Greece as well as in Asia - of his determination, invincibility and extraordinary persona. The point was certainly not lost on the Romans.

The Roman praetor Quintus Cecilius Metellus took the sculpture group to Rome after defeating of the rebellion of Andriscus (Ἀνδρίσκος, Andriskos, also known as the Pseudo-Philip, pretender to the Macedonian throne, arguably the last Macedonian king) at the Second Battle of Pydna in 148 BC and reducing Macedonia to a Roman province (146 BC), and set it up in a new portico he built there. [15]

Unfortunately, the museum lighting and reflections from the glass case (which is near a large window) make photographing the statue difficult.

See: Salvatore Siano et al, The bronze sculpture of Alexander the Great on horseback: An archaeometallurgical study. In: Jens M. Daehner, Kenneth Lapatin, Ambra Spinelli (editors), Artistry in bronze: The Greeks and their legacy, XIXth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, No. 44. Papers published by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Conservation Institute, 2017. At getty.edu, website of the J. Paul Getty Trust. |

|

The bronze statuette of an Amazon on horseback

from the Herculaneum theatre. Height 48.3 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 4999.

Image source: Drawn and engraved by G. Fusaro.

In: Domenico Monaco and Eustace Neville Rolfe,

Specimens from the Naples Museum, page 13

and plate 90. William Clowes & Sons, London, 1884.

At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

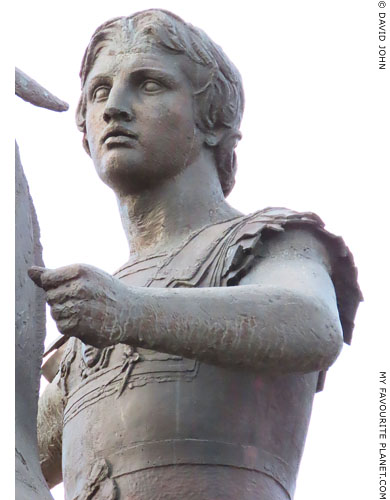

A modern copy of the bronze statuette of Alexander the Great

on horseback from Herculaneum, made in the 1780s.

The replica was made at an unknown date after the restoration of the

original was completed in the 1770s. It has been suggested it was

made either by the Reale Fonderia of Portici (the royal foundry of

Naples), or by one of the craftsmen who worked on the original.

Height 48 cm, Length 55 cm, depth 29 cm.

Museum of Philhellenism, Athens. |

| |

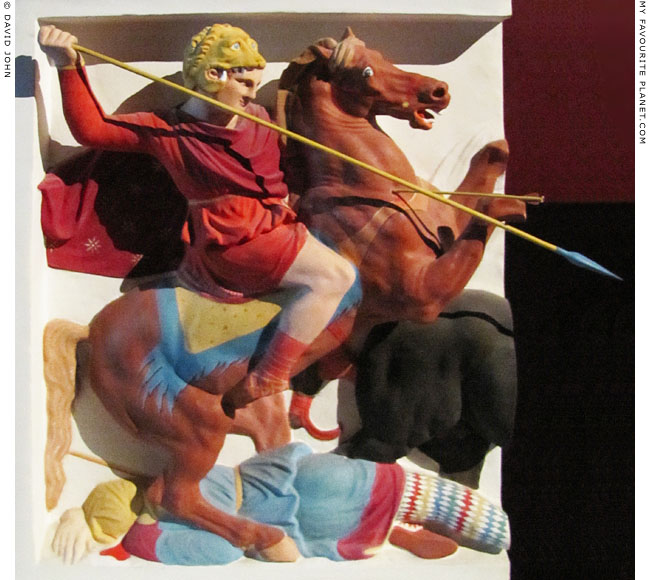

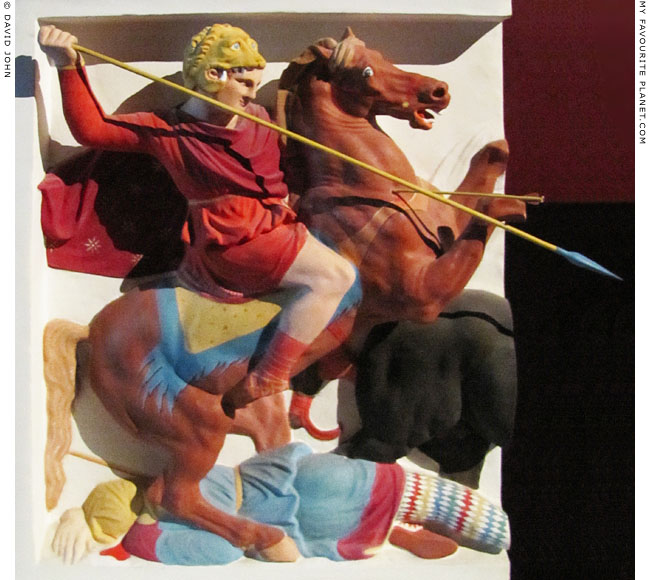

A fragment of an early Hellenistic limestone funerary stele with a relief depicting a Macedonian

cavalryman on a rearing horse in front of a flaming altar on a rock, below which is a snake facing