|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Sculptors N-P |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 5 |

|

Page 5 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors N - P |

| |

| N O P |

|

| |

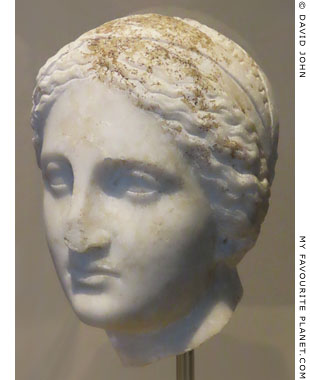

Naukydes of Argos

Ναυκύδης (Latin, Naucydes)

Late 5th - early 4th century BC

From Argos, northeastern Peloponnese.

According to Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 22, section 7), Naukydes was the son of Mothonos (Μόθωνος) and the brother of Polykleitos, who was also a sculptor but perhaps not Polykleitos of Argos (Polykleitos the Elder). Pausanias also mentions another Polykleitos of Argos as a pupil of Naukydes:

"Polycleitus of Argos, not the artist who made the image of Hera, but a pupil of Naucydes, made the statue of a boy wrestler, Agenor of Thebes [at Olympia]."

Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 6, section 2.

It has been suggested that this pupil may have been the son of the more famous Polykleitos of Argos (Polykleitos the Elder), often referred to as Polykleitos the Younger.

Works by Naukydes were mentioned by Pliny the Elder, Pausanias and Tatian. They include: a chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Hebe for the Temple of Hera in Argos; statues of Hekate, Hermes, the poetess Erinna (Ἤριννα, see Menestratos), and Phrixus; a Discobolos (discus thrower), known as the Discobolus of Naukydes, mentioned by Pliny.

"Naucydes is admired for a Mercury, a Discobolus, and a Man sacrificing a Ram."

Pliny, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

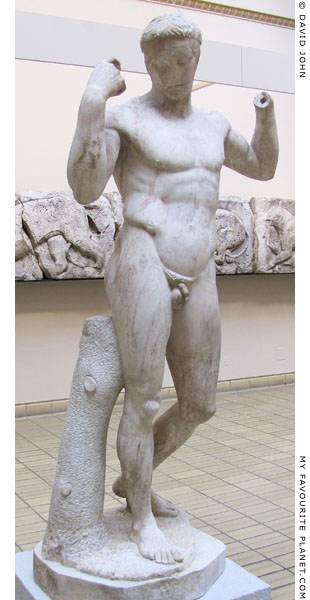

A marble statue of Hermes with a ram, 2nd century AD, is thought to be a copy of a late 5th century BC original by Naukydes. Found in Troezen, northeastern Peloponnese. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 243. |

|

|

| |

Nesiotes

Νησιώτης

Working in Athens, early-mid 5th century BC

Pliny the Elder placed Nesiotes in the 83rd Olympiad (448-445 BC), about the year of our City 300 (years since the legendary foundation of Rome in 753 BC), along with Pheidias, Alcamenes, "Critias" (Kritios) and Hegias.

"He [Phidias] flourished in the eighty-third Olympiad, about the year of our City, 300. To the same age belong also his rivals Alcamenes, Critias, Nesiotes, and Hegias."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

In some old editions of Pliny's work, the name Nesiotes was rendered "Nestocles". Nesiotes means 'island dweller', and some scholars into the the 19th century believed it may have been a surname or nickname of Critias. However, Lucian of Samosata (The rhetorician’s vade mecum) mentioned "the school of Critius and Nesiotes", and a number of statue bases since found on the Athens Acropolis are inscribed with the signatures of Kritios and Nesiotes.

Kritios and Nesiotes made the statue pair of the "Tyrannicides" (Τυραννοκτόνοι) Harmodius and Aristogeiton, set up in the Athenian Agora in 477 BC to replace those made Antenor, which had been taken as booty by Xerxes I of Persia in 480 BC (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 5).

A new article about Kritios and Nesiotes is currently in preparation. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

O |

|

|

|

| |

Onatas of Aegina

Ὀνάτας

Sculptor in bronze, active around 480-450 BC

Son of Mikon from Aegina

For further details, see the Onatas of Aegina page. |

|

|

| |

| Sculptors |

P |

|

|

|

| |

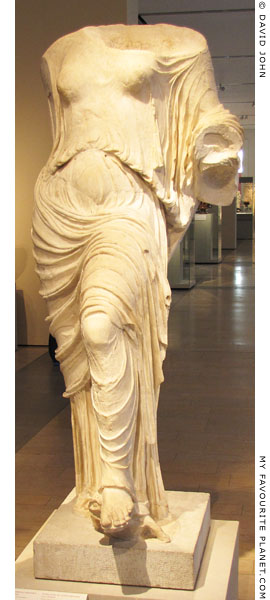

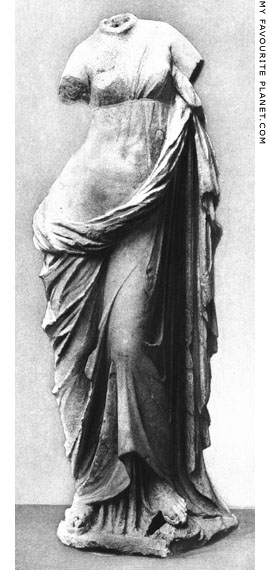

Paionios of Mende

Παιώνιος

2nd half of the 5th century BC

From Mende (Μένδη), on the west coast of the Pallene peninsula, Halkidiki

According to Pausanias, Paionios made the sculptures for the east pediment, above the entrance to the Great Temple of Zeus at Olympia, and those on the west pediment were by Alkamenes. However, Paionios may have made the sculptures on both pediments.

"The sculptures in the front pediment are by Paeonius, who came from Mende in Thrace; those in the back pediment are by Alcamenes, a contemporary of Pheidias, ranking next after him for skill as a sculptor."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 5, section 10. At Perseus Digital Library.

|

|

|

Paionios also made the akroteria for the temple as well as a statue of Nike in Olympia, around 425-420 BC. The fragments of the 1.98 metre high "Nike of Paionios" statue of Parian marble, now reassembled in the Olympia Archaeological Museum (Inv. No. 46-48), were discovered 1875-1880 by German archaeologists at the east side of the temple. The complete figure, with the now missing wing tips, is thought to have been around 3 metres tall. Parts of the 8.81 metre high triangular base of the statue, including the dedicatory inscription of the victory monument, were found at the same time:

"The Messenians and Naupaktians dedicated this to Olympian Zeus as a tithe from their enemies. Paionios of Mende made it and was victorious in making the akroteria for the temple."

Inscription: Olympia 5, No. 259.

The Nike was mentioned by Pausanias:

"The Dorian Messenians who at one time received Naupaktos from the Athenians dedicated at Olympia the image of Nike on a pillar. It is the work of Paionios of Mende, made from spoils taken from the enemy, I think from the war with the Akarnanians and the people of Oiniadai.

The Messenians themselves say that their dedication resulted from their exploit on the island of Sphakteria along with the Athenians, and that they did not inscribe the name of the enemy through fear of the Spartans, whereas they had no fear at all of the people of Oiniadai and Akarnania."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 26.

Paionios is thought to have made the reliefs on the balustrade around the Temple of Athena Nike on the Athens Acropolis, circa 427-421 BC (see also Kallimachos).

It has been suggested that he may have also worked on the interior frieze of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai (see Iktinos under architects), although this has been refuted. Surviving parts of the frieze, now in the British Museum, depict an amazonomachy (a battle between Athenians and Amazons) and a centauromachy (a battle between Lapiths and Centaurs).

It has also been suggested that he may have made the marble statue group known as the Dying Children of Niobe, surviving parts of which are now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. The group has also been conjecturally attributed to Praxiteles and Skopas, although, according to another theory, they may be Roman period copies, perhaps from the reign of Nero (54-68 AD). |

|

|

|

| |

Pasiteles

Πασιτέλης

Also referred to as Pasiteles the Younger

Sculptor, silver chaser and art historian

A Roman citizen from Magna Graecia, Italy, working in Rome in the mid 1st century BC.

He is thought to have had his own school of art.

At the end of Book 33 of the Natural history, Pliny the Elder listed Pasiteles, "who wrote on Wonderful Works", as one of his sources. In Book 36 he said: "Pasiteles speaks in terms of high admiration" of the statues of the Thespian Muses, the "Thespiades" from Thespiae in Boeotia, taken to Rome by consul Lucius Mummius Achaicus (the conquerer of Achaia who destroyed Corinth in 146 BC) and set up near the Temple of Felicity.

"There were erected, too, near the Temple of Felicity, the statues of the Thespian Muses; of one of which, according to Varro, Junius Pisciculus, a Roman of equestrian rank, became enamoured.

Pasiteles, too, speaks in terms of high admiration of them, the artist who wrote five books on the most celebrated works throughout the world.

Born upon the Grecian shores of Italy [Magna Graecia], and presented with the Roman citizenship granted to the cities of those parts, Pasiteles constructed the ivory statue of Jupiter which is now in the temple of Metellus, on the road to the Campus Martius.

It so happened, that being one day at the Docks, where there were some wild beasts from Africa, while he was viewing through the bars of a cage a lion which he was engaged in drawing, a panther made its escape from another cage, to the no small danger of this most careful artist.

He executed many other works, it is said, but we do not find the names of them specifically mentioned."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

Unfortunately Pliny did not describe the statue group of the Thespian Muses, or tell us who made it. In the same chapter he attributed another group of "Thespiades" in the buildings of Asinius Pollio in Rome to Cleomenes, but did not specify which of the artists of this name was meant. See a base of such a group from Thespiai on the Sculptors I - M page.

The "temple of Metellus" was the Temple of Jupiter Stator, thought to have been designed by the Cypriot architect Hermodoros of Salamis, in the Porticus of Metellus (later renamed the Porticus Octaviae). The "Docks" were probably the Navalia, the port on left bank of the River Tiber, also thought to be the work of Hermodoros. See Hermodoros of Salamis under architects.

Citing Marcus Terentius Varro, Pliny also reported that Pasiteles made clay models of his designs before making the sculptures, a practice he said had been introduced to Greek art by Lysistratos of Sikyon, brother of Lysippos.

"Varro praises Pasiteles also, who used to say, that the plastic art was the mother of chasing, statuary, and sculpture, and who, excellent as he was in each of these branches, never executed any work without first modelling it. In addition to these particulars, he states that the art of modelling was anciently cultivated in Italy, Etruria in particular."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 35, chapter 45.

Pasiteles also appears in Pliny's list of most famous artists who worked in silver:

"... and, about the age of Pompeius Magnus, Pasiteles..."

Pliny, Natural history, Book 33, chapter 55.

He applied his mastery to the making of the first silver mirrors:

"However, to finish our description of mirrors on the present occasion, the best, in the times of our ancestors, were those of Brundisium, composed of a mixture of stannum and copper: at a later period, however, those made of silver were preferred, Pasiteles being the first who made them, in the time of Pompeius Magnus."

Natural history, Book 33, chapter 45.

A marble statue group by Stephanus of the Appiades is listed by Pliny among several artworks displayed in the buildings of Gaius Asinius Pollio in Rome (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4). From an inscription on an extant statue, he is supposed to have been a pupil of Pasiteles.

It has been suggested that the "San Ildefonso Group" may be a work by Pasiteles or his school.

Pausanias mentioned that a sculptor named Kolotes (Κωλώτης) made a table of ivory and gold which stood in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. However, he was uncertain whether the artist was from Herakleia (the name of several cities) or a pupil of Pasiteles from Paros. Part of the text, in which Pasiteles' teacher is named, is missing. Some scholars have considered Kolotes to be the Colotes mentioned by Pliny as a pupil of Pheidias who worked at Olympia, while others have seen him as a later artist of the same name.

"The table is made of ivory and gold, and is the work of Colotes. Colotes is said to have been a native of Heracleia, but specialists in the history of sculpture maintain that he was a Parian, a pupil of Pasiteles, who himself was a pupil of .... There are figures of Hera, Zeus, the Mother of the gods, Hermes, and Apollo with Artemis. Behind is the disposition of the games.

On one side are Asclepius and Health, one of his daughters [Asklepios and Hygieia]; Ares too and Contest by his side; on the other are Pluto, Dionysus, Persephone and nymphs, one of them carrying a ball. As to the key (Pluto holds a key) they say that what is called Hades has been locked up by Pluto, and that nobody will return back again therefrom."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 20, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Pheidias

Φειδίας (Latin, Phidias)

Athens, circa 480-430 BC

A sculptor, painter and architect, Pheidias was the son of Charmides of Athens ("Φειδίας Χαρμίδου Ἀθηναῖος", Strabo, Geography, Book 8, chapter 3, section 30), and a friend of Pericles. He may have been a pupil of the Athenian painter Euenor and sculptors Hegias of Athens and Ageladas of Argos.

Pheidias collaborated with several artists, and his large scale sculptural projects in Athens and Olympia meant maintaining a large workshop of artists and workmen. His pupils are said to have included Alkamenes, Agorakritos of Paros and Kolotes (Colotes).

He is thought to have been the prime mover in the design of Classical Greek sculpture, and is considered by many to be the greatest ancient Greek sculptor. He was particularly praised by Pliny the Elder.

"An almost innumerable multitude of artists have been rendered famous by their statues and figures of smaller size. Before all others is Phidias, the Athenian, who executed the Jupiter [Zeus] at Olympia, in ivory and gold, but who also made figures in brass as well. He flourished in the eighty-third Olympiad, about the year of our City 300."

...

"Phidias, besides the Olympian Jupiter, which no one has ever equalled, also executed in ivory the erect statue of Minerva, which is in the Parthenon at Athens [Athena Parthenos statue]. He also made in brass, beside the Amazon [in Ephesus] above mentioned, a Minerva, of such exquisite beauty, that it received its name from its fine proportions [perhaps the "Athena Lemnia" statue]. He also made the Cliduchus, and another Minerva, which Paulus Aemilius dedicated at Rome in the Temple of Fortune of the passing day. Also the two statues, draped with the pallium, which Catulus erected in the same temple; and a nude colossal statue. Phidias is deservedly considered to have discovered and developed the toreutic art."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

"Among all nations which the fame of the Olympian Jupiter [Zeus] has reached, Phidias is looked upon, beyond all doubt, as the most famous of artists."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

Pliny wrote that Pheidias was said to have begun his career as a painter.

"Seeing that Phidias himself is said to have been originally a painter, and that there was a shield at Athens which had been painted by him."

Natural history, Book 35, chapter 34.

It has been suggested that Pheidias' first teacher may have been the Athenian painter Euenor (or Evenor, Εὐήνορ), the father of Parrasios (Παρράσιος) who later designed the relief on the shield of his colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos, dedicated around 430 BC, which stood between the Parthenon and the Propylaia on the Athens Acropolis.

"In addition to the works I have mentioned, there are two tithes dedicated by the Athenians after wars. There is first a bronze Athena, tithe from the Persians who landed at Marathon. It is the work of Pheidias, but the reliefs upon the shield, including the fight between Centaurs and Lapithae, are said to be from the chisel of Mys [Μῦς], for whom they say Parrhasius the son of Evenor, designed this and the rest of his works. The point of the spear of this Athena and the crest of her helmet are visible to those sailing to Athens, as soon as Sunium is passed."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 28, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

During the 470s Pheidias is thought to have learned bronze sculpting from Hegias. This is based on a passage from one of the Discourses (or Orations, Λόγοι) by the Greek orator, philosopher and historian Dio Chrysostom (Δίων Χρυσόστομος Dion Chrysostomos, circa 40-115 AD):

"Interlocutor. Since you make it evident that on general grounds you are an admirer of Socrates and also that you are filled with wonder at the man as revealed in his words, you can tell me of which among the sages he was a pupil; just as, for example, Pheidias the sculptor was a pupil of Hegias, and Polygnotus the painter and his brother were both pupils of their father Aglaophon, and Pherecydes is said to have been a teacher of Pythagoras, and Pythagoras in turn a teacher of Empedocles and Sophocles."

Dio Chrysostom, Discourses, No. 55: On Homer and Socrates. At LacusCurtius.

Soon after he may have moved to the Peloponnese to study with Ageladas. The scholiast (commentator) on Aristophanes' Frogs (line 504), named Ageladas as the teacher of Pheidias, but also wrote that he made the statue of Herakles Alexikakos (Ἡρακλῆς Ἀλεξίκακος, the averter of evil) set up in the Attic deme of Melite to commemorate the deliverance from the great plague (87th Olympiad, 430-427 BC) during the Peloponnesian War. This is probably too late for the assumed dates of the career of Ageladas of Argos, and there may have been two sculptors named Ageladas (see Ageladas of Argos).

See: Antonio Corso, The art of Praxiteles: The development of Praxiteles' workshop and its cultural tradition until the sculptor's acme (364-1 BC), page 8. L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome, 2004.

Plutarch (Life of Pericles, 13) related that Pheidias was accused by enemies of Pericles of stealing gold intended for the Athena Parthenos statue, and of impiety for portraying Pericles and himself among the figures of the Amazonomachy on the statue's shield (see the "Strangford Shield" on Athens Acropolis gallery page 13). Having been warned by Pericles to carefully weigh the gold, Pheidias was able to disprove the charge of theft, but he was found guilty of impiety, and died while in prison.

According to other sources, mentioned by scholiasts, Pheidias was banished from Athens and was condemned to death and executed while in Elis after completing the statue of Zeus at Olympia.

No extant sculpture can be attributed beyond doubt to Pheidias, although many Roman period statues and statuettes are thought to be copies of his works.

Pheidias was responsible for the overall planning of the Periclean Acropolis building project and designed and made many of the sculptures for the new buildings, including the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) Athena Parthenos statue (between around 447 and 438 BC) for the Parthenon (Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4; Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 24, sections 5-7, although he did not mention that the statue was by Pheidias).

(See an illustrated article on a copy of the Athena Parthenos statue from Pegamon.)

He is said to have made a bronze statue of Apollo Parnopios (Ἀπόλλωνος Παρνόπιου, "the Locust God", see photo below) which stood outside the Parthenon (Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 24, section 8).

Around 432 BC he made the colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia (Pliny, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4), later to be included as one of Philo of Byzantium's Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Pliny wrote that he was assisted by his pupil Colotes (Book 34, chapter 19; Book 35, chapter 34). This may be the same Kolotes (Κωλώτης) mentioned by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 20, section 2), who however was uncertain if he was from Herakleia or Paros, a pupil of Pasiteles. According to Strabo (Geography, Book 8, chapter 3, section 30) parts of the statue, particularly the garment as well as the screens around the god's throne, were painted by the painter Panainos (Πάναινος; Latin, Panaenus), a nephew of Pheidias. Pliny (Natural History, Book 35, chapter 34; Book 36, chapter 35) and Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 11, sections 5-6) called him a brother of Pheidias. The statue was later taken to Constantinople.

In 1958 archaeologists at Olympia discovered the remains of a building containing fragments of ivory and semi-precious stone, terracotta moulds and other casting equipment, as well as a small, black-glaze drinking cup inscribed "Φειδίο εἰμί" (Pheidio eimi, I belong to Pheidias, see photo below), from which they concluded that the building was the workshop of Pheidias, mentioned by Pausanias:

"Outside the Altis [the sanctuary of Zeus] there is a building called the workshop of Pheidias, where he wrought the image of Zeus piece by piece. In the building is an altar to all the gods in common."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 15, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

According to Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, section 5), Pheidias made the marble statue of Kybele, the Mother of the Gods, in the Metroon (Μητρῷον, a sanctuary dedicated to a mother goddess) in the Athens Agora. However, it is thought that the statue seen by Pausanias may have been the work by Pheidias' pupil and favourite Agorakritos of Paros mentioned by Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4). The statue is thought to have depicted the goddess enthroned, with a lion attendant, and holding a tympanon (drum). Several dozen dedicatory reliefs of this image, perhaps based on the statue, have been found in the Agora.

Similar confusion surrounds a marble statue of Nemesis that Pausanias wrote was made by Pheidias for the sanctuary of the goddess at Rhamnous (Ῥαμνοῦς), near Marathon, Attica (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 33). Pliny and Strabo wrote that the statue of Nemesis at Rhamnous was attributed to Agorakritos. See Agorakritos of Paros for further details about the Kybele and Nemesis statues.

Pheidias made a statue of Aphrodite Ourania (Ἀφροδίτη Οὐρανία, Heavenly Aphrodite) of Parian marble for the sanctuary of the goddess, near the Hephaisteion in the Athens Agora.

"Hard by is a sanctuary of the Heavenly Aphrodite ... The statue still extant is of Parian marble and is the work of Pheidias."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 14, section 7.

He also made a chryselephantine statue of Aphrodite Ourania (Ἀφροδίτη Οὐρανία, Heavenly Aphrodite) for her sanctuary near the agora of Elis, western Peloponnese. Pausanias described the goddess as standing with one foot on a tortoise. Around a century later, in another sanctuary nearby Skopas later made the bronze cult statue of Aphrodite Pandemos (Πάνδημος, Common) riding a male goat. As in a number of other cases, he made a point of not explaining the significance of the tortoise and he-goat, omissions which have been debated by modern scholars.

"Behind the portico built from the spoils of Corcyra is a temple of Aphrodite, the precinct being in the open, not far from the temple. The goddess in the temple they call Heavenly; she is of ivory and gold, the work of Pheidias, and she stands with one foot upon a tortoise. The precinct of the other Aphrodite is surrounded by a wall, and within the precinct has been made a basement, upon which sits a bronze image of Aphrodite upon a bronze he-goat. It is a work of Scopas, and the Aphrodite is named Common [Pandemos]. The meaning of the tortoise and of the he-goat I leave to those who care to guess."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 25, section 1.

Plutarch also mentioned the statue of Aphrodite "with one foot on a tortoise" at Elis (Moralia, 4, 32, see quote below).

The "Brazza Aphrodite", a marble statue of Aphrodite, thought to be from Athens, and now in the Altes Museum, Berlin (Inv. No. Sk 1459), has been hypothetically identified with Pheidias' Aphrodite Ourania at Elis (see photo below). |

|

|

| |

Two almost identical reconstructed Roman period marble statues of Athena in Dresden (Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Inv. Nos. Hm 049 and Hm 050) were controversially identified by the German archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler as copies of Pheidias' bronze "Athena Lemnia" (Λημνία) from the Athens Acropolis, mentioned by Pausanias and Lucian of Samosata. The statue was dedicated by those who settled in the Athenian colony of Lemnos (see Alkamenes), probably around 450-440 BC.

"There are two other offerings [on the Acropolis], a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and the best worth seeing of the works of Pheidias, the statue of Athena called Lemnian after those who dedicated it."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 28, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

"Lycinus: ... But I should just like to know what you consider to be Phidias's best work.

Polystratus: Can you ask? The Lemnian Athene, which bears the artist's own signature; oh, and of course the Amazon leaning on her spear."

Lucian, A portrait study, in The works of Lucian of Samosata, Volume 3 (of 4). Translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler. At Project Gutenberg.

Pliny the Elder's mention of an exquisitely beautiful bronze Athena by Pheidias is also believed to be a reference the "Athena Lemnia".

"He also made in brass, beside the Amazon above mentioned, a Minerva, of such exquisite beauty, that it received its name from its fine proportions."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19 (see full quote above).

In a speech delivered in January 170 AD in the Bouleterion of Smyrna, the Greek orator and author Aelius Aristides (Αἴλιος Ἀριστείδης, circa 117-180 AD) also referred to a statue known as "the Lemnia" among works of extraordinary artistic merit Oration 34, 28, κατά των εξορχουμενων, Against those who lampoon (The Mysteries of Oratory).

A much later orator, Himerios (Ἱμέριος, circa 315-386 AD) also appears to have been referring to the "Athena Lemnia" when he mentioned a beautiful Athena by Pheidias which showed the goddess without a helmet.

"Pheidias did not always make images of Zeus, nor did he always cast Athena armed into bronze, but turned his art to the other gods and adorned the Maiden's cheeks with a rosy blush, so that in place of her helmet this should cover the goddess's beauty."

Himerios, Oratio 68,4. In: Aristides Colonna, Himerii Declamationes et orationes cum deperditarum fragmentis. Typis Publicae Officinae Polygraphicae, Rome, 1951. |

|

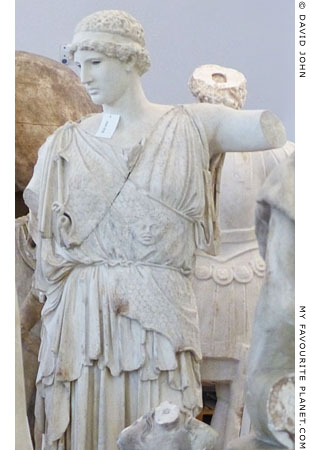

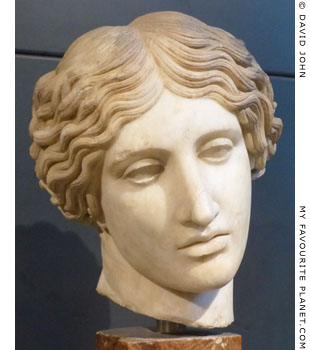

A reconstructed marble statue of Athena

wearing the aegis and Gorgoneion. Roman Imperial period. Late 1st century AD.

Height with restored head 209 cm,

width 72 cm, depth 59 cm.

One of two almost identical Roman period

marble torsos of Athena in the Albertinum,

Dresden (the other Inv. No. Hm 049),

controversially identified by the German

archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler as copies

of the bronze "Athena Lemnia" by Pheidias.

He added to each torso a cast of a marble

head of a female in the Museo Civico

Archeologico, Bologna, Inv. No. G 1060.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden.

Replica B. Inv. No. Hm 050. |

|

| |

Pausanias also wrote that Pheidias helped the Megarian sculptor Theokosmos to make a chryselephantine statue of Zeus for the Olympieion (sanctuary of Olympian Zeus) at Megara. Work on the statue was interrupted by the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) and it was never completed.

"After this when you have entered the precinct of Zeus called the Olympieum you see a noteworthy temple. But the image of Zeus was not finished, for the work was interrupted by the war of the Peloponnesians against the Athenians, in which the Athenians every year ravaged the land of the Megarians with a fleet and an army, damaging public revenues and bringing private families to dire distress.

The face of the image of Zeus is of ivory and gold, the other parts are of clay and gypsum. The artist is said to have been Theocosmus, a native, helped by Pheidias. Above the head of Zeus are the Seasons and Fates [Ὧραι καὶ Μοῖραι], and all may see that he is the only god obeyed by Destiny, and that he apportions the seasons as is due. Behind the temple lie half-worked pieces of wood, which Theocosmus intended to overlay with ivory and gold in order a complete the image of Zeus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 40, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Theokosmos was the father of the sculptor Kallikles of Megara, who made statues of boxers at Olympia, and perhaps the grandfather of the sculptor Apelleas.

Pliny the Elder related a story that Pheidias made a statue of an Amazon for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in a competition with Polykleitos, Kresilas, Cydon, Phradmon (of Argos). This story has been doubted by scholars, although it is believed that one or more of these works may have been provided models for some extant Amazon statues (see photos below).

"The most celebrated of these artists, though born at different epochs, have joined in a trial of skill in the Amazons which they have respectively made. When these statues were dedicated in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, it was agreed, in order to ascertain which was the best, that it should be left to the judgment of the artists themselves who were then present: upon which, it was evident that that was the best, which all the artists agreed in considering as the next best to his own. Accordingly, the first rank was assigned to Polycletus, the second to Phidias, the third to Cresilas, the fourth to Cydon, and the fifth to Phradmon."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny erroneously believed that Pheidias invented the art of bronze sculpture, a claim he repeated a number of times.

"Phidias, besides the Olympian Jupiter [Zeus], which no one has ever equalled, also executed in ivory the erect statue of Minerva [Athena Parthenos], which is in the Parthenon at Athens. He also made in brass, beside the Amazon above mentioned [at Ephesus], a Minerva [Athena], of such exquisite beauty, that it received its name from its fine proportions [perhaps 'Kallimorphos' or 'Kalliste']. He also made the Cliduchus [a female holding keys], and another Minerva, which Paulus Aemilius dedicated at Rome in the Temple of Fortune of the passing day. Also the two statues, draped with the pallium, which Catulus erected in the same temple; and a nude colossal statue. Phidias is deservedly considered to have discovered and developed the toreutic art."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

The exact meaning of "toreutic art." (Artem toreuticen), used by Pliny when referring to working or casting bronze and silver, is unknown.

|

|

| |

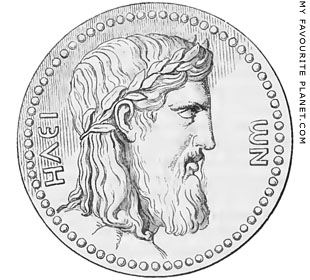

Roman period coins of Elis, which controlled

the Olympic Games, with depictions of Zeus,

thought to be Pheidias' statue of Olympian

Zeus. Issued during the reign of

Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD).

Source of images: Wolfgang Helbig, Guide

to the public collections of classical

antiquities in Rome, Volume 1, The

sculptures at the Vatican, the Capitoline

museum, the Lateran museum. Translated

from German by James Fullarton Muirhead

and Findlay Muirhead. Karl Baedecker,

Leipzig, 1895. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

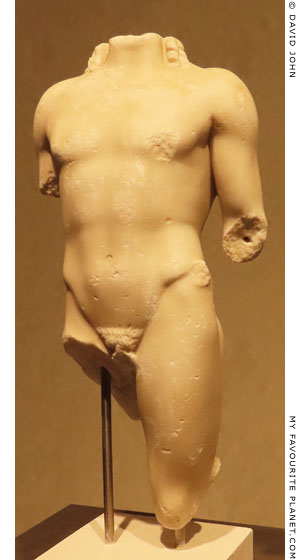

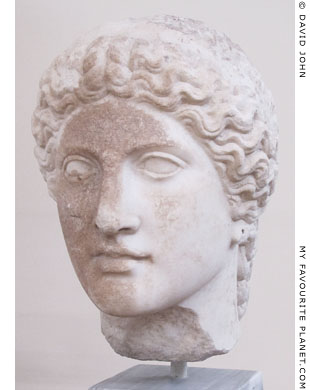

Fragmentary marble statue, thought

to be a copy of Pheidias' bronze

Apollo Parnopios, "the Locust God".

2nd century AD. From Korkyra (Corfu).

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

Pliny also believed that sculpture-making in stone pre-dated the art of painting. Here he also mentioned a marble statue of Aphrodite by Pheidias which had been taken to Rome, his pupils Alkamenes and Agorakritos of Paros, and details of the Athena Parthenos statue:

"We must not omit to remark, that the art of sculpture is of much more ancient date than those of painting and of statuary in bronze; both of which commenced with Phidias, in the eighty-third Olympiad, or in other words, about three hundred and thirty-two years later. Indeed, it is said, that Phidias himself worked in marble, and that there is a Venus [Aphrodite] of his at Rome, a work of extraordinary beauty, in the buildings of Octavia [Porticus Octaviae].

A thing, however, that is universally admitted, is the fact that he was the instructor of Alcamenes, the Athenian, one of the most famous among the sculptors. By this last artist, there are numerous statues in the temples at Athens; as also, without the walls there, the celebrated Venus, known as the Aphrodite ἐν χήποις, a work to which Phidias himself, it is said, put the finishing hand. Another disciple also of Phidias was Agoracritus of Paros, a great favourite with his master, on account of his extremely youthful age; and for which reason, it is said, Phidias gave his own name to many of that artist's works.

...

Among all nations which the fame of the Olympian Jupiter [Zeus] has reached, Phidias is looked upon, beyond all doubt, as the most famous of artists: but to let those who have never even seen his works, know how deservedly he is esteemed, we will take this opportunity of adducing a few slight proofs of the genius which he displayed.

In doing this, we shall not appeal to the beauty of his Olympian Jupiter, nor yet to the vast proportions of his Athenian Minerva [Athena Parthenos], six and twenty cubits in height, and composed of ivory and gold; but it is to the shield of this last statue that we shall draw attention; upon the convex face of which he has chased a combat of the Amazons [Amazonomachy], while, upon the concave side of it, he has represented the battle between the Gods and the Giants [Gigantomachy].

Upon the sandals again, we see the wars of the Lapithae and Centaurs, so careful has he been to fill every smallest portion of his work with some proof or other of his artistic skill.

To the story chased upon the pedestal of the statue, the name of the 'Birth of Pandora' has been given; and the figures of new-born gods to be seen upon it are no less than twenty in number.

The figure of Victory [Nike], in particular, is most admirable, and connoisseurs are greatly struck with the serpent and the sphinx in bronze lying beneath the point of the spear.

Let thus much be said incidentally in reference to an artist who can never be sufficiently praised; if only to let it be understood that the richness of his genius was always equal to itself, even in the very smallest details."

Pliny the Elder Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

"Pheidias' cup", fragments of a small black-glazed ceramic kothos (cup),

with the words "ΦΕΙΔΙΟ ΕΙΜΙ" (I belong to Pheidias) scratched on the base.

Second half of the 5th century BC. Found in Pheidias'

workshop in the sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia, Greece.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. P 3653.

|

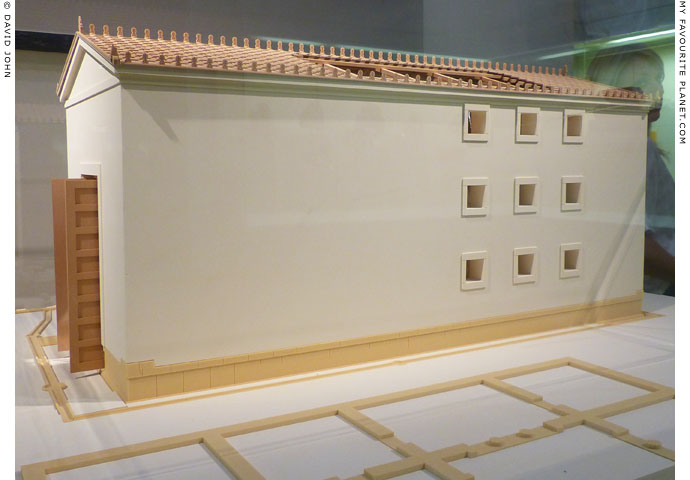

Usually referred to as part of a small drinking cup, it has also been described as an oinochoe (wine jug). It is a kothos (or kothon; κοθως or κοθων), a drinking cup of the type named "Pheidias cup" after the vessel found in Olympia (see photos, right).

Discovered by archaeologists in 1958 in the ruins of the building identified as the workshop in which Pheidias made the sculptures for the Temple of Zeus, including the colossal chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of the god. The workshop (see photo below) stood just to the west (behind) the temple and had the same orientation and dimensions, presumably so that Pheidias could assess the effects of light and space on the statue when installed. In the 5th - 6th centuries AD it was converted into a three-aisled Christian basilica, and was the only building to survive earthquakes in 522 and 551 AD which devastated the sanctuary.

Other inscribed vessels found in the workshop are displayed in the museum so that the inscriptions can be clearly seen. However, for some reason this vessel is now displayed upright, and visitors have to peer deep into the glass case at the tiny scratched inscription - the most important object in the case - reflected in a small mirror beneath it, and in its shadow. Needless to say, it is impossible for mere mortals (even those with zoom lenses) to even see the faint, mirror-inversed graffito. A very poor and disappointing design decision in an otherwise excellent museum.

See also: a plate found in the workshop with a painting of Perseus with the head of Medusa. |

A kothos, a drinking cup of the type

named "Pheidias cup" after the vessel

found in Pheidias' workshop in Olympia.

Found during excavations southwest of

the Kerameikos cemetery, Athens, during

the construction of the first Metro line.

It is thought that many of the dead in a

mass grave in this cemetery extension

were hastily buried victims of the plague

that struck Athens in 430/429 and

427/426 BC (Thucydides, History of the

Peloponnesian War, Book 2, chapter 47).

Kerameikos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A kothos with the word ΚΟΘΩΝ (kothon)

incised (scratched) on its base.

475-450 BC. From the sanctuary

of Poseidon, Isthmia.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. IP 2047. |

| |

| |

A model of Pheidias' workshop in Olympia, after a reconstruction by Alfred and Eva Mallwitz.

Scale 1:50.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. |

| |

|

|

|

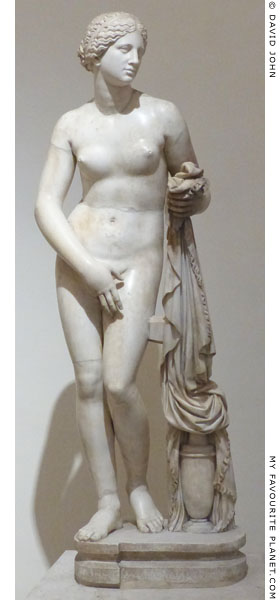

The "Brazza Aphrodite", also known as the "Berliner Aphrodite" or "Aphrodite on a tortoise",

a marble statue of Aphrodite, head and arms now missing. Hypothetically identified on stylistic

grounds with Pheidias' chryselephantine statue of Aphrodite Ourania at Elis, mentioned by

Pausanias and Plutarch. The left foot and tortoise were added by an early 19th century restorer.

430-420 BC. Thought to be from Athens. Height (including modern base) 177 cm,

width 73.5 cm, depth 71.5 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1459. Purchased for the museum

in June 1892 by Reinhard Kekulé from the art dealer Zuber in Venice.

|

|

The "Aphrodite à la tortue", a headless and armless marble statuette of a female with her left foot on a tortoise, 2nd - 3rd century AD, found at Doura Europos in Syria (see photo, right), may depict Aphrodite Ourania. Louvre, Inv. No. AO 20126.

As in many other languages, there is no distinction in ancient or modern Greek between land tortoises and sea, river and marsh turtles, and the word chelone (xελώνη) was and still is used to refer to all in general. If or in what ways ancient Greeks distinguished between the different types of shelled reptiles in daily life, gastronomy, mythology or art is unclear. Attempts have been made by modern scholars to explain the tortoise or turtle of Pheidias' statue of Aphrodite Ourania in terms of attributes of the goddess' celestial origins or aspects, or her emergence from the sea following her birth from the severed genitals of Ouranos (Οὐρανος, Heaven). Perhaps the animal was part of a stellar constellation or her stepping stone across the Mediterranean.

The tortoise was a symbol of Aegina, an ancient rival and enemy of Athens, and tortoises and turtles were depicted on the island state's coins. In 431 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians expelled the Aeginetans from their island and established a cleruchy (a type of colony) there. The Spartans settled the exiles in Thyreatis (Θνρεᾶτις) in the eastern Peloponnese, on the border between Laconia and Argolis, but in 424 BC they were attacked by an Athenian force commanded by Nikias, and most of them were killed or enslaved (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 2, chapter 27 and Book 4, chapters 56-57).

Plutarch saw a quite different significance in the undertrodden tortoise:

"Phidias made a statue of Aphrodite at Elis, with one foot on a tortoise, as a symbol that women should stay at home and be silent. For the wife ought only to speak either to her husband, or by her husband, not being vexed if, like a flute-player, she speaks more decorously by another mouth-piece."

Arthur Richard Shilleto (translator), Plutarch's Morals, IV, Conjugal precepts, section 32, page 78. Bohn's Classical Library. George Bell and Sons, London, 1898.

Read more about tortoises in ancient Greek history and

mythology on Ancient Stageira gallery page 19. |

|

"Aphrodite à la tortue", a marble

statuette of a female with her

left foot on a tortoise.

2nd - 3rd century AD. Found during

excavations in 1922-1923 at Doura

Europos, Syria. Height 57 cm.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. AO 20126.

Source: Franz Cumont, L'"Aphrodite

à la tortue" de Doura-Europos.

In: Monuments et mémoires de la

Fondation Eugène Piot, tome 27,

fascicule 1, 1924. pages 31-44,

Planche III. At Persée. |

|

| |

Philathenaios

Working in Athens in the mid 1st century AD, Roman Imperial period

Known only from the signature of the sculptors Hegias and Philathenaios, thought to be Athenians, on a colossal marble portrait statue of Emperor Claudius found in the Metroon in Olympia.

See Hegias (Roman period). |

|

|

| |

Philon, son of Emporion

Φίλον ℎὀνπορίονος (Philon, son of Emporion)

Early 5th century BC

Athens

It is generally assumed that an artist only mentioned his father in a signature if he was also an artist. However, Emporion does not appear anywhere else as a proper name.

Philon, son of Emporion is not mentioned in ancient literary sources. Pliny the Elder mentions a Philon in a list of sculptors who made bronze statues of "athletes, armed men, hunters, and sacrificers" (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19). However, this is thought to be a Philon of the Hellenistic period associated with a bronze monument of Hephaistion, the friend of Alexander the Great, designed by Lysippos.

The signature of Philon, son of Emporion has survived on the marble bases of three votive dedications, all found near the North Wall of the Athens Acropolis in the 19th century. Nothing else is known about his work, and it has even been suggested that he may have been a stonemason rather than a sculptor.

1. A Fragment of a marble base of a perirrhanterion (περιρραντήριον, lustral basin) inscribed vertically with the signature of Philon, son of Emporion. Around 500-475 BC. Found between 1877 and 1886. See photo below.

2. A fragment of an unfluted column dedication inscribed vertically with the signature of Philon, son of Emporion. Found before 1888.

[Φίλ]ον ℎὀν-

[πορί]ονος

[ἐπ]οίεσεν

Philon,

son of Emporion,

made it.

Inscription IG I(3) 778 (also IG I(2) 509; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 37).

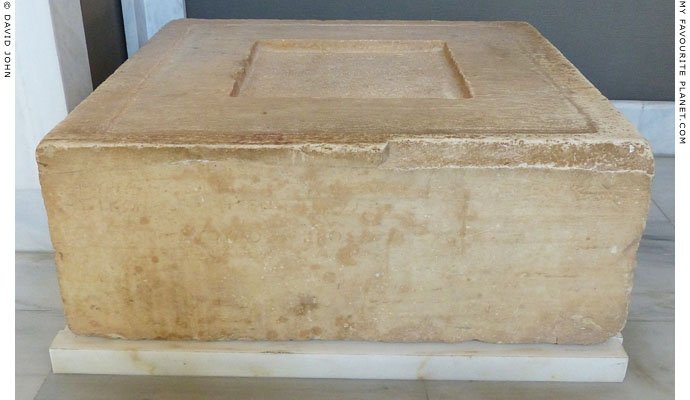

Acropolis Museum (formerly in the courtyard of the old Acropolis Museum). Height without tenon 115 cm, upper diameter 23 cm, lower diameter 26 cm; bottom broken. Diameter of tenon on top 14 cm, height of tenon 5 cm.

3. A fragment of a fluted column dedication of Pentelic marble. Found between 1877 and 1886. Only part of the signature has survived, and has been restored on the basis of the similarity of the letter forms to those of the previous two.

[Φίλον ℎὀνπορίονος ἐποίε]σεν.

[ὁ δεῖνα - - - ἀ]νέθεκεν.

[Philon, son of Emporion,] made it.

[o deina - - - ] dedicated it.

Inscription IG I(2) 519 (Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 12).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6282.

Height 37 cm, diameter circa 20 cm. 18 flutes; width of flute 3.6 - 3.8 cm. |

|

|

| |

A Fragment of a marble base of a perirrhanterion (περιρραντήριον, lustral basin)

inscribed vertically with the signature of the artist Philon, son of Emporion.

Around 500-475 BC. Found between 1877 and 1886 near the North Wall of

the Athens Acropolis. Pentelic marble. Height 48 cm, upper diameter 19 cm.

16 flutes; width of flute 3 cm. Diameter of foot of pedestal 49 cm, height of

foot 10 cm. This is the only marble basin on which an artist's signature is

preserved. The dedication was probably inscribed on the lip of the basin.

Φίλον με ἐποίεσεν

ℎὀνπορίονος {Ἐνπορίονος}

Philon made me,

son of Emporion.

Inscription IG I³ 777 (also IG I² 508; Antony E. Raubitschek,

Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 381).

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6267. |

| |

|

|

|

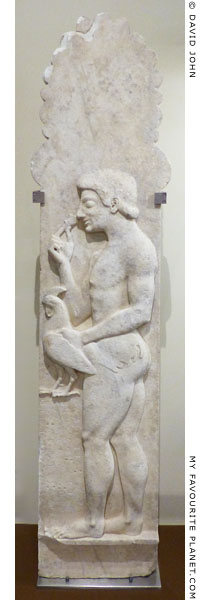

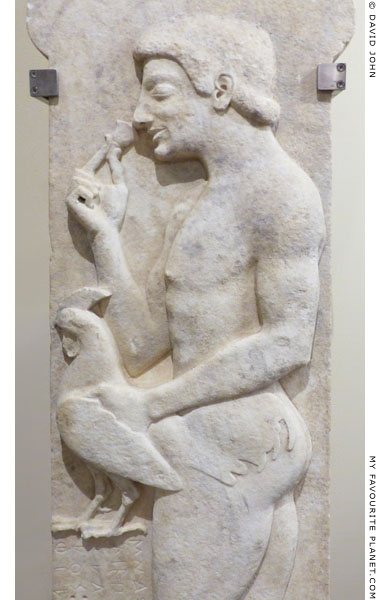

The inscribed marble grave stele of Mnasitheos, with a palmette (anthemion) crowning and

a relief of a naked young man standing in profile, facing left. He smells a flower he holds

in his right hand, and in the left hand he carries a cockerel. The epitaph in the Boeotian

alphabet is carved vertically to the left of his legs, below the cockerel (see photo below).

The signature of the Athenian sculptor Philorgos (Φίλοργος) is inscribed below

the predella (ledge) on which the young man stands (see photo below).

Around 520-510 BC. Discovered in 1992 in the cemetery of ancient Akraiphia, Boeotia.

Hymettian marble. height 165 cm, width at base 37.5 cm, depth 8.85 cm.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 28200.

See: Angeliki K. Andreiomenou, Notes de sculpture et d'épigraphie en Béotie,

I. La stèle de Mnasithéios, oeuvre de Philourgos: étude stylistique. In: Bulletin

de correspondance hellénique, Volume 130, livraison 1, 2006, pages 39-61. At Persée. |

|

| |

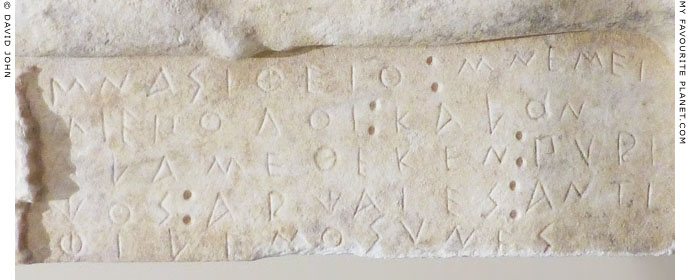

The elegaic couplet in the Boeotian alphabet inscribed on the grave stele of Mnasitheos in Thebes:

Μνασιθείο: μνɛμ ’ εἰμὶ ἐπ’ ὀδõι: καλόν:

ἀλά μ’ ἔθεκεν: Πύριχος: ἀρχαίες: ἀντὶφιλεμοσύνες.

I am the lovely grave of Mnasitheos, but Pyrichos

erected me at the roadside for old friendship's sake.

Inscription SEG 49:505 at The Packard Humanities Institute. |

| |

The signature of the Athenian sculptor Philorgos inscribed on the grave stele of Mnasitheos

in Thebes, below the predella (ledge) on which the relief of the young man's feet stand.

Φιλοργος ⋮ ἐποίε<σ>-

εν.

Philorgos made it.

Philorgos (or Philourgos) is thought to be the same

sculptor as Philergos, who worked with or for Endoios. |

| |

Phyromachos

Φυρόμαχος

Phyromachos of Kephisia and Phyromachos of Athens

Phyromachos is the name of two or more Greek sculptors who worked in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, known from a handful of mentions in ancient literature and inscriptions.

New articles about Phyromachos are currently in preparation. |

|

|

| |

Polycharmos

Πολύχαρμος (Latin, Polycharmus)

Perhaps from Rhodes, late Hellenistic period

At the end of a short passage in the Natural history, in which Pliny the Elder mentioned some of the marble statues exhibited in the Porticus Octaviae (Porticos of Octavia) in Rome, is a clause which is unclear, perhaps corrupt. In most manuscripts it appears as: "Venerum lavantem sesededalsa stantem Polycharmus", which made no sense. However in just one manuscript, the Bamberg Codex, "sesededalsa" appears as "sesedaedalsas". This was separated into two words thus creating the name "Daedalsas" (see Doidalsas for further details). The clause has thus been emended to:

"... venerem lavantem sese daedalsas, stantem polycharmus."

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

"... Daedalsas executed a Venus Bathing and Polycharmus a Venus Standing."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4.

This reading has not been universally accepted and other suggestions have been put forward.

A number of modern scholars have attempted to identify Polycharmos' "Venus Standing". In 1906 the French archaeologist Salomon Reinach (1858-1932) reported that he had made a new emendment to Pliny's mysterious clause, and that it should read:

"Venerem lavantem sese Daedalsas, stantem [pede in uno] Polycharmus."

This led him to suggest that Polycharmos' statue was of the type depicting Aphrodite standing on one foot while adjusting her sandal on the other foot. The original is thought to have stood in Aphrodisias in Caria (Geyre, Aydin, Turkey), and was depicted on coins of that city. He accepted the claim by his younger brother Théodore Reinach that the Venus Bathing by Daedalsas was the original of the Crouching Aphrodite (French, Vénus accroupi) type statues (see Doidalsas): "La Vénus de Daedalsas a été identifiée: c'est la Vénus accroupi." ("The Venus of Daedalsas has been identified: it is the Crouching Venus.")

See: Salomon Reinach, Passage de Pline relatif à la Vénus de Polycharmus. In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 50e année, N. 5, 1906, page 306. At Persée.

It has been suggested that Pliny's Polycharmus may have been the Polycharmos of Rhodes (Πολύχαρμος) whose son Philiskos signed an inscribed statue base in the sanctuary of Artemis Polo, on the Northern Aegean island of Thasos, perhaps around 100-50 BC.

Ἀντιφῶν Εὐρυμενίδου

τὴν αὑτοῦ μητέρα

Ἀρὴν Νέωνος Ἀρτέμιδι Πωλοῖ.

Φιλίσκος Πολυχάρμου

Ῥόδιος ἐποίησεν.

Antiphon son of Eurymenides

(dedicated the statue of) his own mother Are,

daughter of Neon, to Artemis Polo.

Philiskos, son of Polycharmos of Rhodes made it.

Inscription IG XII Suppl. 383 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

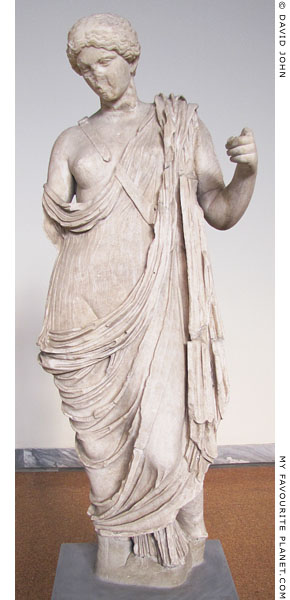

Found in 1909 during excavations by the Turkish archaeologist Theodor Makridi Bey (Θεόδωρος Μακρίδης, 1872-1940, later to become the second director of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum). Near it lay the lower part (waist down) of a draped female statue, made of local Thasian dolomite marble. Now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

See:

Gustave Mendel, Musées impériaux ottomans: Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines, Tome premiere. (Mendel, Catalogue of Greek, Roman and Byzantine sculpture in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, Volume I), no. 136 (Inv. No. 2155), pages 345-346. Constantinople, 1912. At the Internet Archive.

Theodor Macridy, Un Hieron d'Artemis Polo à Thasos. Fouilles du Musée Impérial Ottoman. In: Jahrbuch des kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (JDI), Band 27, pages 1-19, especially pages 11-18. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1912. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Immediately before the passage mentioning Daedalsas and Polycharmus, Pliny the Elder mentioned marble statues by a sculptor named Philiscus of Rhodes, set up near Porticus Octaviae. Naturally, Pliny offers us no connection between his Philiscus and Polycharmus nor any clue as to when or where they worked.

"Near the Portico of Octavia, there is an Apollo, by Philiscus of Rhodes, placed in the Temple of that God; a Latona and Diana also; the Nine Muses; and another Apollo, without drapery."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Polydoros, son of Polydoros

Πολύδωρος (Latin, Polydorus)

From Rhodes, late 1st century BC - early 1st century AD, Roman Imperial period

See Agesander of Rhodes |

|

|

| |

Polyeuktos

Πολυεύκτος (Polyeuctos)

Working in Athens, early 3rd century BC

It has been suggested that he may have been a pupil of Lysippos.

He is known only as the maker of a bronze statue of the Athenian orator Demosthenes (Δημοσθένης), 384-322 BC), which was erected near the Altar of the Twelve Gods in the Athenian Agora in 280/279 BC, 42 years after the orator's death.

The statue was noted by Pausanias as standing between the Tholos, the statues of the Eponymoi (Eponymous Heroes) and the sanctuary of Ares. However, he did not name the sculptor.

"After the statues of the eponymoi come statues of gods, Amphiaraus, and Eirene [Peace] carrying the boy Plutus [Wealth]. Here stands a bronze figure of Lycurgus, son of Lycophron, and of Callias, who, as most of the Athenians say, brought about the peace between the Greeks and Artaxerxes, son of Xerxes. Here also is Demosthenes, whom the Athenians forced to retire to Calauria, the island off Troezen, and then, after receiving him back, banished again after the disaster at Lamia.

Exiled for the second time Demosthenes crossed once more to Calauria, and committed suicide there by taking poison, being the only Greek exile whom Archias failed to bring back to Antipater and the Macedonians."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Plutarch also failed to name the sculptor, but tells us more about the statue, that it was bronze and that it stood with its fingers clasped. Some surviving statues show Demosthenes holding a scroll, but these are modern restorations (see Homer).

"It was to this man, a little while after his death, that the Athenian people paid worthy honour by erecting his statue in bronze, and by decreeing that the eldest of his house should have public maintenance in the prytaneium. And this celebrated inscription was inscribed upon the pedestal of his statue:

'If thy strength had only been equal to thy purposes, Demosthenes,

Never would the Greeks have been ruled by a Macedonian Ares.'

Of course those who say that Demosthenes himself composed these lines in Calauria, as he was about to put the poison to his lips, talk utter nonsense.

Now, a short time before I took up my abode in Athens, the following incident is said to have occurred. A soldier who had been called to an account by his commander, put what little gold he had into the hands of this statue of Demosthenes. It stood with its fingers interlaced, and hard by grew a small plane tree. Many of the leaves from this tree, whether the wind accidentally blew them thither, or whether the depositor himself took this way of concealing his treasure, lay clustering together about the gold and hid it for a long time. At last, however, the man came back, found his treasure intact, and an account of the matter was spread abroad, whereupon the wits of the city took for a theme the incorruptibility of Demosthenes and vied with one another in their epigrams."

Plutarch, Lives, Demosthenes, 31. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

In the essay collection Moralia, several entries of which are attributed to "Pseudo-Plutarch" rather than Plutarch himself, Polyeuktos is named as the sculptor of the statue. Here Demosthenes himself writes the couplet which was later inscribed on his statue base.

"And with that he [Demosthenes] called for a writing-table; and if we may credit Demetrius the Magnesian, on that he wrote a distich, which afterwards the Athenians caused to be affixed to his statue; and it was to this purpose:

'Had you, Demosthenes, an outward force

Great as your inward magnanimity,

Greece should not wear the Macedonian yoke.'

This statue, made by Polyeuctus, is placed near the cloister where the altar of the twelve Gods is erected."

Pseudo-Plutarch, Lives of the Ten Orators, 847. At attalus.org. (Elsewhere referred to as Pseudo-Plutarch, Moralia, 847a.)

In Greek: Plutarch, Vitae decem oratorum, 847a. At Perseus Digital Library.

The elegaic couplet is also quoted in the Suda:

"If your power had been equal to your judgement, Demosthenes, never would the Ares of Macedon have ruled the Greeks."

Demosthenes, delta, 455 at stoa.org.

More than 40 extant portraits identified as Demosthenes, mostly marble heads and busts, are believed to be copies of this work. The identification of the portrait type followed the discovery in 1753 of a small bronze bust, inscribed ΔΗΜΟΣΘΕΝΗΣ (Demosthenes), in the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. Height 13 cm. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 5467.

Three complete figures have survived, but all have been extensively restored:

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Marble statue, said to have been found in Campana in the 18th century. Height 202 cm. Inv. No. 2782.

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Marble head, height 26 cm. Inv. No. 1532.

Ripon, Yorkshire, Newby Hall.

Rome, Braccio Nuovo, Vatican Museums. Marble statue from the Villa Aldobrandini. Height 207 cm. Inv. No. 2255.

The Roman period heads and busts include:

Athens, National Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 327.

Berlin, Neues Museum. Inv. No. Sk 302.

Berlin State Museums (SMB). Inv. No. Sk 303.

London, British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1973.3-3.2 (Sculpture 1840).

Munich, Glyptothek. Herm found in 1825 in the Circus of Maxentius, Rome. Inv. No. 292.

Ostia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 92.

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum. Marble head purchased in Constantinople (Istanbul), said to have come from Eskişehir, Turkey (ancient Dorylaion). Inv. No. AN1923.764.

Rome, Barracco Museum. Inv. No. MB 140.

Rome, Sale dei Filosofi, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums. Herm. Luna marble. Height 51 cm. From the Albani Collection (Inv. No. B 77).

Rome, Palazzo Altemps. Inv. No. 8581.

Also:

A bronze statuette (see photo below), Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Inv. No. 2007.221.

Hellenistic silver medallion with a portrait of Demosthenes, from Miletopolis, Mysia. Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Misc. 10839. |

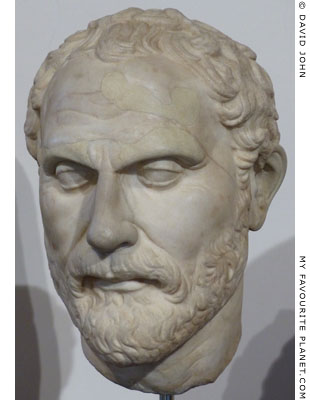

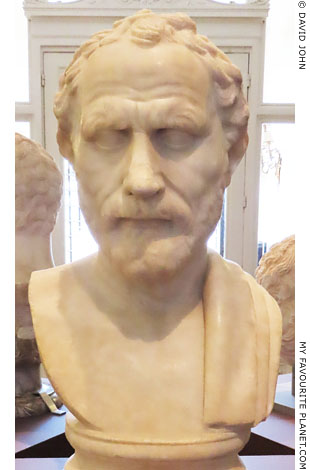

A marble portrait head of Demosthenes.

One of the best preserved examples of

the type thought to be copied from the

bronze statue by Polyeuktos.

Roman period. Pentelic marble.

Purchased in Rome. Height 29 cm.

Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 140. |

| |

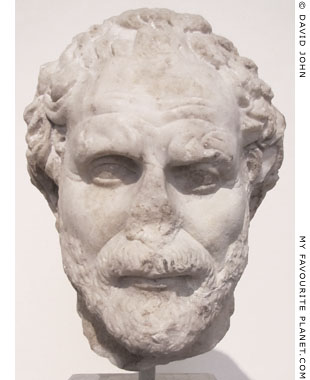

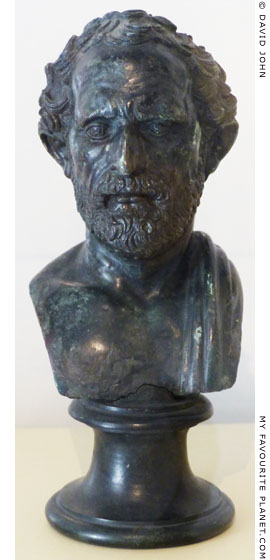

Marble Head of Demosthenes found

in the National Garden, central Athens.

Roman period. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 327. |

| |

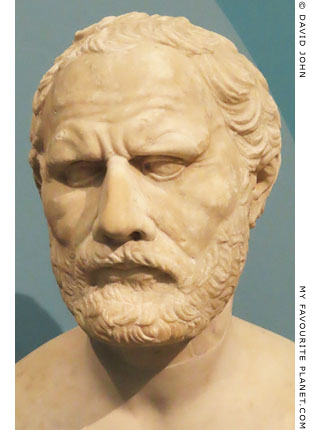

Marble head of Demosthenes

on a modern bust.

Roman period, 2nd century AD.

Antikensammlung, Berlin State

Museums (SMB). Inv. No. Sk 303. |

| |

Marble bust of Demosthenes.

Roman period, 1st - 2nd century AD. Sold

by Prince Barberini in 1798 to the sculptor

and antiquities dealer Vincenzo Pacetti,

who sold it to the Vatican in 1804.

Height 52 cm, height of head 27 cm,

width 31 cm, depth 25 cm.

Chiaramonti Museum, Vatican

Museums. Inv. No. 1555. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

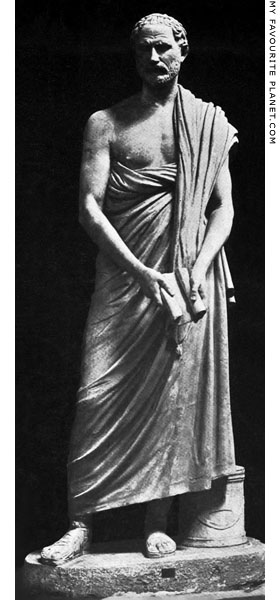

Roman period marble statue of Demosthenes.

Left: restored with the hands holding a papyrus scroll.

Right: Restored "correctly", with the hands clasped, as in the description

by Plutarch, following the find of another fragment. Height 207 cm.

Braccio Nuovo, Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 2255.

Formerly in the Villa Aldobrandini, Frascati.

Source: Anton Hekler, Greek and Roman portraits, plate 56.

G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1912. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

A modern copper-alloy cast of a

Roman period lead-bronze statuette

of Demosthenes, thought to be based

on the statue by Polyeuktos.

1st - 2nd century AD. From central Anatolia.

Height 23.2 cm, width 8 cm, depth 7 cm.

Staatliche Antikensammlung und

Glypothek, Munich. No invoice number.

This aftercast was made from the original

in Munich the 1920s. The original is now

in the Arthur M. Sackler Museum,

Harvard University. Inv. No. 2007.221.

See: www.harvardartmuseums.org/

collections/object/4842 |

|

Small bronze bust of Demosthenes

found in Herculaneum.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 5469. |

|

| |

Polykleitos the Elder

Πολύκλειτος (much-renowned)

Also referred to as Polykleitos of Argos or Polykleitos of Sikyon. Spellings include Polyklitos, Polykletos, Polycletus, Polycleitus or Polyclitus.

5th century BC; thought to have been born circa 480 BC and active around 460-420 BC.

According to Pliny the Elder, he was working during the 90th Olympiad (420 BC), at the same time as Phradmon, Myron, Pythagoras, Skopas, and Perellus (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19).

Like Myron, he was a pupil of Ageladas of Argos (Pliny the Elder, Book 34, chapter 19), who may have taught at Argos.

He was either from Argos (Plato, Protagoras, section 311c; Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 18, section 8) or Sikyon, northern Peloponnese (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19). This may indicate that Pliny and other ancient authors conflated two separate artists, one from Sikyon and the other from Argos. Modern theories suggest that he may have been a native of Sikyon but was given citizenship of Argos following his training there or for his work at the Heraion.

Pliny the Elder named his pupils as Argius, Asopodorus (these two may have been one person, the Argive Asopodorus), Alexis, Aristides, Phrynon, Dinon, Athenodorus, and Demeas the Clitorian (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19). Pupils named by Pausanias were Periclytus (Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 17, section 4) and Kanachos the Younger of Sikyon (Book 6, chapter 13, section 7).

An artist or artists named Polykleitos are mentioned by Cicero, Galen, Lucian, Pausanias, Philo of Byzantium, Plato, Pliny the Elder, Plutarch, Quintilian, Strabo and Vitruvius. As with other artists referred to by ancient authors, it is unclear whether they were writing about the same artist, or even whether the several references to Polykleitos by Pausanias and Pliny the Elder concern one or more artists of this name. It is generally thought that there were at least two.

Since some works ascribed to Polykleitos are thought to have been made after the period estimated by modern scholars for his career, the maker of the later works has been conjecturally named "Polykleitos the Younger", perhaps the son or grandson of "Polykleitos the Elder". It is further thought that the later sculptor may have been responsible for the statues of athletes at Olympia mentioned by Pausanias (see below).

Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, sections 3-5) wrote that Polykleitos designed the tholos and the great theatre at Epidauros. Again, it has been suggested that this was Polykleitos the Younger. However, the theatre is thought to have been built around 340-320 BC (or later), which is considered too late for the dates assumed for the lifetimes of father, son or even grandson. See Polykleitos under architects.

He also mentioned a Polykleitos as a brother of Naukydes (probably Naukydes of Argos, late 5th - early 4th century BC), son of Mothonos, and a Polykleitos of Argos, a pupil of Naukydes (see Polykleitos, son of Mothonos). It is possible that one of these was the "Polykleitos the Younger" responsible for the later works including the buildings at Epidauros, and equally possible that they were the same person. |

|

Polykleitos wrote a treatise, known as the Kanon (or Canon; Κάνον, literally rule or law), concerning the ideal design of a male nude according to his theories of aesthetics, mathematical proportions, rhythm, balance and symmetry. The work has not survived but is known from references by other ancient authors, including Plutarch, Galen and Philo of Byzantium.

The marble head in Berlin, known as the "Polykletian Diskophoros", is thought to be a Roman period copy, circa 140 AD, of a bronze statue made by Polykleitos around 460 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1833.

Pliny the Elder on works by Polykleitos

All Pliny's mentions of works by Polykleitos are in Natural History, Book 34, in the chapters dealing with bronze. This is no guarantee that all the works mentioned were made of bronze, and Pausanias described cryselephantine and marble statues by Polykleitos (see below).

Pliny wrote that while Myron used bronze from Delos, Polykleitos used bronze from Aegina. "They were contemporaries and fellow-pupils, but there was great rivalry between them as to their materials."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 5.

Polykleitos is said to have made a statue of an Amazon for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in a competition with Cydon, Phradmon (of Argos), Kresilas and Pheidias, which may have been a model for one or more extant Amazon statues (see photos below).

"The most celebrated of these artists, though born at different epochs, have joined in a trial of skill in the Amazons which they have respectively made. When these statues were dedicated in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, it was agreed, in order to ascertain which was the best, that it should be left to the judgment of the artists themselves who were then present: upon which, it was evident that that was the best, which all the artists agreed in considering as the next best to his own. Accordingly, the first rank was assigned to Polycletus, the second to Phidias, the third to Cresilas, the fourth to Cydon, and the fifth to Phradmon."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

"Polycletus of Sicyon, the pupil of Agelades, executed the Diadoumenos [Διαδούμενος, Diadem-bearer; an athlete tying a victor's headband], the statue of an effeminate youth, and remarkable for having cost one hundred talents; as also the statue of a youth full of manly vigour, and called the Doryphoros [the Spear-bearer].

He also made what the artists have called the Model statue [Canon; the Doryphoros], and from which, as from a sort of standard, they study the lineaments: so that he, of all men, is thought in one work of art to have exhausted all the resources of art.

He also made statues of a man using the body-scraper [᾿αποξυομενος, apoxyomenos, a man "scraping himself" with a strigil], and of a naked man challenging to play at dice [Talo incessentem]; as also of two naked boys playing at dice, and known as the Astragalizontes [boys playing knuckle-bones]; they are now in the atrium of the Emperor Titus, and it is generally considered, that there can be no work more perfect than this.

He also executed a Mercury [Hermes], which was formerly at Lysimachia [in Thrace]; a Hercules Ageter [the Leader] seizing his arms, which is now at Rome; and an Artemon, which has received the name of Periphoretos [Carried about].

Polycletus is generally considered as having attained the highest excellence in statuary, and as having perfected the toreutic art [metalworking], which Phidias invented. A discovery which was entirely his own, was the art of placing statues on one leg [contrapposto]. It is remarked, however, by Varro, that his statues are all square-built, and made very much after the same model."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

Lucian of Samosata (circa 125-180 AD) also mentioned a Diadoumenos statue by Polykleitos, "the beautiful Polyclitus ... the Youth tying on the Fillet", presumably a bronze copy, in the courtyard of the house of the wealthy Eukrates in Sikyon. (Lucian, The lover of lies, also known as The liar or The doubter. See the full quote under Myron.)

Several extant Roman period marble statues of a Diadoumenos are thought to be copies of Polykleitos' bronze original.

Lysippos "also made the statue of Hephaestion, the friend of Alexander the Great, which some persons attribute to Polycletus, whereas that artist lived nearly a century before his time."

Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. |

|

|

|

Both Cicero (Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106-43 BC) and Quintilian (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, circa 35-100 AD) saw an evolution in technique and aesthetic quality from the time of Greek artists such as Kanachos of Sikyon (the Elder), Kallon and Hegesias (see Hegias), in the late 6th - early 5th century, approaching a zenith in the works of Polykleitos. Quintilian added Pheidias, Alkamenes, Lysippos and Praxiteles to the evolutionary curve.

"But who that has seen the statues of the moderns, will not perceive in a moment, that the figures of Canachus are too stiff and formal, to resemble life? Those of Calamis, though evidently harsh, are somewhat softer. Even the statues of Myron are not sufficiently alive; and yet you would not hesitate to pronounce them beautiful. But those of Polycletes are much finer, and, in my mind, completely finished. The case is the same in painting; for in the works of Zeuxis, Polygnotus, Timanthes, and several other masters who confined themselves to the use of four colours, we commend the air and the symmetry of their figures; but in Aetion, Nicomachus, Protogenes, and Apelles, every thing is finished to perfection."

Cicero, Brutus, a History of Famous Orators, section 70. At attalus.org.

"The same differences exist between sculptors. The art of Callon and Hegesias is somewhat rude and recalls the Etruscans, but the work of Calamis has already begun to be less stiff, while Myron's statues show a greater softness of form than had been achieved by the artists just mentioned.

Polyclitus surpassed all others for care and grace, but although the majority of critics account him as the greatest of sculptors, to avoid making him faultless they express the opinion that his work is lacking in grandeur. For while he gave the human form an ideal grace, he is thought to have been less successful in representing the dignity of the gods. He is further alleged to have shrunk from representing persons of maturer years, and to have ventured on nothing more difficult than a smooth and beardless face.

But the qualities lacking in Polyclitus are allowed to have been possessed by Phidias and Alcamenes. On the other hand, Phidias is regarded as more gifted in his representation of gods than of men, and indeed for chryselephantine statues he is without a peer, as he would in truth be, even if he had produced nothing in this material beyond his Minerva at Athens and his Jupiter at Olympia in Elis, whose beauty is such that it is said to have added something even to the awe with which the god was already regarded: so perfectly did the majesty of the work give the impression of godhead.

Lysippus and Praxiteles are asserted to be supreme as regards faithfulness to nature. For Demetrius is blamed for carrying realism too far, and is less concerned about the beauty than the truth of his work."

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, chapter 10, sections 7-9. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias on works by Polykleitos

The colossal cryselephantine (gold and ivory) cult statue of Hera made for the Heraion near Argos, around 420 BC (see photo below), perhaps his final work:

"The statue of Hera is seated on a throne; it is huge, made of gold and ivory, and is a work of Polycleitus. She is wearing a crown with Graces and Seasons worked upon it, and in one hand she carries a pomegranate and in the other a sceptre. About the pomegranate I must say nothing, for its story is somewhat of a holy mystery. The presence of a cuckoo seated on the sceptre they explain by the story that when Zeus was in love with Hera in her maidenhood he changed himself into this bird, and she caught it to be her pet. This tale and similar legends about the gods I relate without believing them, but I relate them nevertheless."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 17, section 4.

A seated marble statue of Zeus Meilichios (Ζευς Μειλίχιος, Zeus the Gracious) in the city of Argos, probably made shortly after 417-416 BC:

"Passing over a statue of Creugas, a boxer, and a trophy that was set up to celebrate a victory over the Corinthians, you come to a seated image of Zeus Meilichius (Gracious), made of white marble by Polycleitus. I discovered that it was made for the following reason..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 20, section 1.

His reason involves an anecdotal account of events during the violent conflict between democrats and Spartan-backed oligarchs in Argos, 417-416 BC. According to his explanation, the statue was made following the restoration of democracy as an act of propitiation to the god for the bloodshed: "Subsequently they had recourse to purifications for shedding kindred blood; among other things they dedicated an image of Zeus Meilichius".

See: Ephraim David, The oligarchic revolution in Argos 417 B.C., in: L'Antiquité Classique, Année 1986, Tome 55, pages 113-124. At Persée.

Marble statues of Leto and her divine twin children Apollo and Artemis in the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia (Ἀρτέμιδa Ὀρθία) on Mount Lykone (Λυκώνη), along the road south from Argos in the direction of Tegea in Arcadia:

"On the top of the mountain is built a sanctuary of Artemis Orthia (of the Steep), and there have been made white marble images of Apollo, Leto, and Artemis, which they say are works of Polycleitus.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 24, section 5.

A statue of Aphrodite by Polykleitos, among a number of statues beneath tripods set up at Amyklai (Ἀμύκλαι), south of Sparta (see Bathykles of Magnesia):

"Aristander of Paros and Polycleitus of Argos have statues here; the former a woman with a lyre, supposed to be Sparta, the latter an Aphrodite called 'beside the Amyclaean'. These tripods are larger than the others, and were dedicated from the spoils of the victory at Aegospotami."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 3, chapter 18, section 8.

Although Pausanias wrote that the tripods were dedicated after the naval Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC (see Kanachos the Younger), he does not state whether the statues were made at the same time. This date would have been too late for Polykleitos the Elder. Aristander (Aristandros) of Paros may have been the father of Skopas.

Among statues of athletes at Olympia attributed by Pausanias to Polykleitos, was the statue of the boy boxing champion Antipater of Miletus:

"By the statue of Thrasybulus stands Timosthenes of Elis, winner of the foot-race for boys, and Antipater of Miletus, son of Cleinopater, conqueror of the boy boxers. Men of Syracuse, who were bringing a sacrifice from Dionysius to Olympia, tried to bribe the father of Antipater to have his son proclaimed as a Syracusan. But Antipater, thinking naught of the tyrant's gifts, proclaimed himself a Milesian and wrote upon his statue that he was of Milesian descent and the first Ionian to dedicate his statue at Olympia.

The artist who made this statue was Polycleitus, while that of Timosthenes was made by Eutychides of Sicyon, a pupil of Lysippus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 2, sections 6-7.

Pausanias does not tell us which of the tyrants of Syracuse named Dionysios (Διονύσιος) he is referring to. Dionysios I (or Dionysios the Elder, circa 432-367 BC) was tyrant 405-367 BC. His son Dionysios II (or Dionysios the Younger, circa 397-343 BC) ruled 367-357 BC and again 346-344 BC.

Also at Olympia:

"The statue of Cyniscus, the boy boxer from Mantinea, was made by Polycleitus." (see below)

Book 6, chapter 4, section 11.

"Pythocles, a pentathlete of Elis, was made by Polycleitus." (see photo below)

Book 6, chapter 7, section 10.

"Xenocles of Maenalus, who overthrew the boys at wrestling... that of Xenocles is by Polycleitus."

Book 6, chapter 9, section 10.

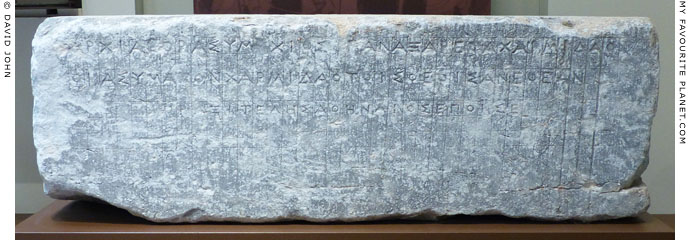

An inscribed marble statue base was found on 16 Januar 1878, built into the Byzantine east wall in the Sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia. The inscribed epigram includes the signature of Polykleitos and the name of Xenokles Euthyphronos of Mainalos (Μαίναλος), a town in Arcadia.

Πολύκλετος ἐποί<η>σε.

Ξενοκλῆς ⋮ Εὐθύφρονος

Μαινάλιος.

Μ̣αινάλιος Ξενοκλῆς νίκασα

Εὐθύφρονος υἱὸς ἀπτὴς μονο-

παλᾶν {μουνοπαλᾶν} τέσ<σ>αρα σώμαθ’ ἑλών.

Polykleitos made it.

Xenokles, son of Euthyphronos

of Mainalos.

Xenokles of Mainalos won,

the son of Euthyphronos, without failing,

the wrestling, taking four bodies.

Inscription IvO 164.

"There are statues of Thersilochus of Corcyra and of Aristion of Epidaurus, the son of Theophiles [Ἀριστίωνα Θεοφίλους Ἐπιδαύριον], made by Polycleitus the Argive; Aristion won a crown for the men's boxing, Thersilochus for the boys'.

Bycelus, the first Sicyonian to win the boys' boxing-match, had his statue made by Canachus of Sicyon, a pupil of the Argive Polycleitus."

Book 6, chapter 13, sections 6-7.

The base of the statue of Aristion son of Theophiles of Epidauros, signed by Polykleitos, was discovered on 30 October 1879, beneath the Byzantine east wall in Olympia.

Ἀριστίων Θεοφίλεος Ἐπιδαύριος.

Πολύκλειτος ἐποίησε.

Inscription IvO 165.

The cult staue of a temple of Zeus Philios (Ζευς Φιλιος, Zeus the Friendly) for the god's temple in the sanctuary of the Great Goddesses (Demeter and Persephone) in the agora of Megalopolis, Arcadia.

"Within the precinct is a temple of Zeus Friendly. Polycleitus of Argos made the image; it is like Dionysus in having buskins as footwear and in holding a beaker in one hand and a thyrsus in the other, but an eagle sitting on the thyrsus does not fit in with the received accounts of Dionysus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 31, section 4.

See: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer (Inscriptions of Greek sculptors), Nos. 90-92, pages 70-71. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

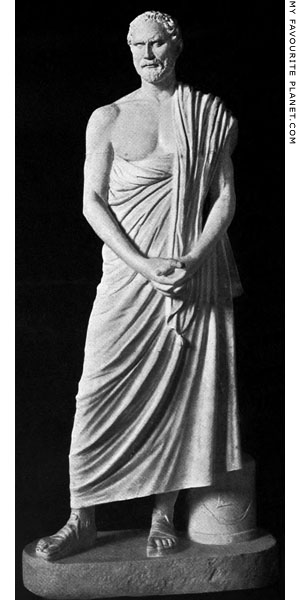

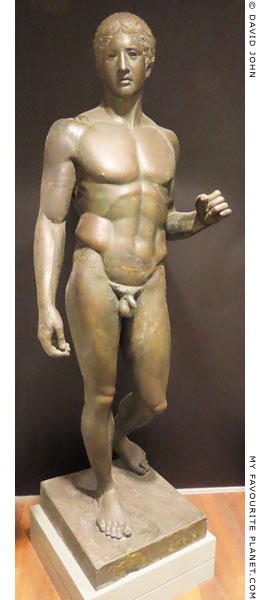

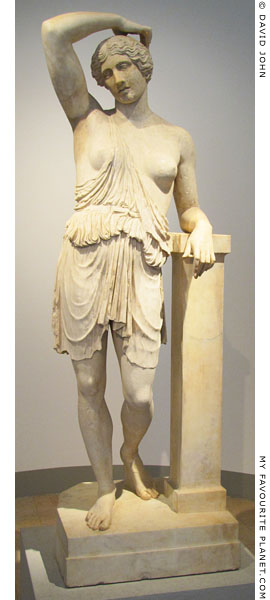

A Roman period marble statue thought

to be a copy of the bronze Doryphoros

(Δορυφόρος, Spear-Bearer), also known

as the Canon (Κάνον, Kanon), made by

Polykleitos the Elder, around 440 BC.

The original bronze figure would not have

needed the support of a tree stump.

Found in 1797 on the south side of

the Samnite Palaestra in Pompeii.

Height 212 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 6011. |

| |

A plaster cast of a Roman period marble

statue of the Doryphoros type.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 16.157.

The statue from which this cast was made,

found in Herculaneum, is in the National

Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 16.157 6146. Height 212 cm. |

| |

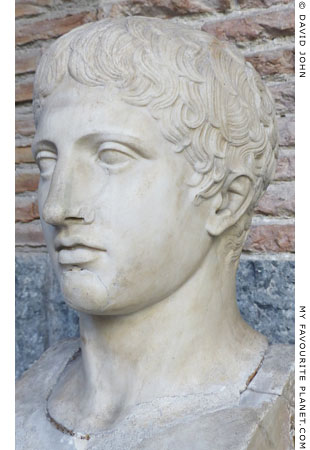

A marble head of the Doryphoros type,

placed on the shaft of a herm.

Roman period. Found in Herculaneum.

Height with herm shaft 187 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 6412. |

| |

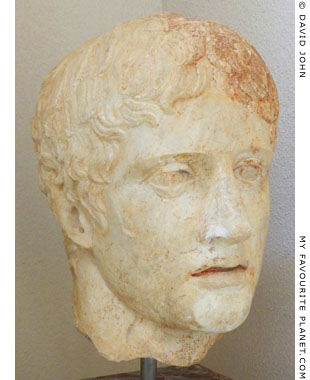

A marble head from a statue

of the Doryphoros type.

Roman period. Found in the

ancient theatre of Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. T 386.

Currently in the Museum of the History

of the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympia. |

| |

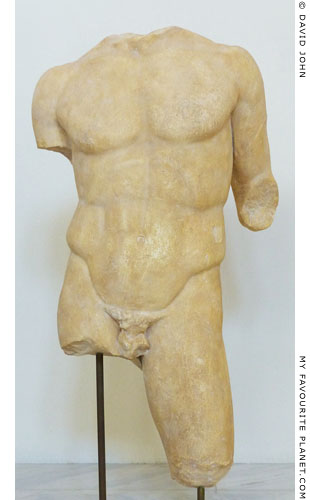

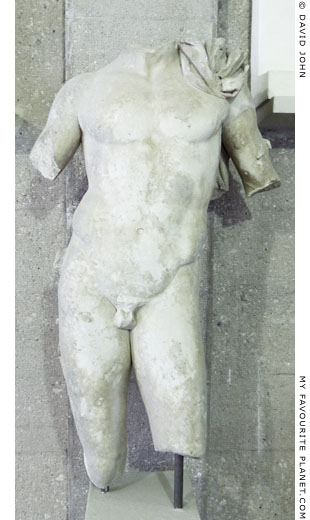

The torso of a marble statue