|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Middle East > Turkey > Ephesus |

| Ephesus, Turkey |

A brief history of Ephesus |

|

|

page 2 |

|

|

| |

The Gate of Mazeus and Mithridates, the entrance to the Lower Agora of Ephesus. See gallery page 33. |

| |

The archaeological site of Ephesus is 3 km (2 miles)

southwest of the town of Selçuk which has its own guide

with practical information and a photo gallery, including

photos of the Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Selçuk. |

For information about the Temple of Artemis,

see Selçuk gallery 1, pages 3-4. |

Detailed information about Ephesus' sights can be found

with the photos in our Ephesus photo gallery. |

| |

For opening times and admission charges for sites and sights

see Page 4: Sightseeing in Ephesus |

| |

"The empress of Ionia, renowned Ephesus, famous for war and learning."

Greek Anthology, IV. 20, 4.

Ephesus (Ancient Greek Eφεσος, Ephesos) was an ancient city founded by Ionian Greeks who arrived around 1000 BC on the part of the west coast of Anatolia (Asia Minor) which became known as Ionia. The city grew into an important commercial port, a religious centre for the cult of Artemis, and one of the twelve cities of the Ionian League. [1]

The area has been inhabited since the Neolithic Age (about 6200 BC) [2], and archaeological finds from the Ayasuluk Citadel (see Selçuk photo gallery 1, page 2 for further information) reveal that it was already settled during the Bronze Age (e.g. during the Mycenaean era, 1500-1400 BC) long before the Ionians arrived here.

According to legend the Greek founder of Ephesus was Androklos (Ἄνδροκλος), son of Kodros (Κόδρος), a legendary king of Athens. He was said to have driven out the native Carians and Lelegians (probably Lydians).

The city was famed for the Temple of Artemis (see information and photos of the ruins of the temple in the Selçuk photo gallery 1, pages 3-4), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The prehistoric sanctuary of the Anatolian mother goddess Kybele (Κυβέλη) was transformed by the Greeks into a place of worship for Artemis, and they built ever larger temples for her.

The first great temple was completed in 550 BC, and the second even more magnificent temple was finished in the early 3rd century BC. Destroyed and rebuilt several times, its final destruction is alleged to have been by a Christian mob incited by Saint John Chrysostom in 401 AD. |

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin from Ephesus, 365-350 BC [3],

showing a bee, one of the symbols of Artemis and the city,

and the letters Ε Φ. On the other side are other symbols:

the front part of a stag and a palm tree.

Münzkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

Inv. No. AAB1269. Diameter 21.4 mm, weight 15.08 grams. |

| |

Ionia, including Ephesus, was conquered around 560 BC by Croesus, king of the neighbouring kingdom of Lydia. He enlarged the city, financed the rebuilding of the Temple of Artemis and may have introduced coinage to Ephesus. When Croesus was defeated in 546 BC by King Cyrus the Great, Ionia became part of the enormous Persian Empire.

In 498 BC Ephesus joined the Ionian Revolt, backed by Athens, against the Persian King Darius the Great, which led to the Battle of Ephesus and the Graeco-Persian wars. The Greeks thwarted consequent attempts by Darius and his successor Xerxes to conquer Greece, and forced the Persians from the European mainland and most of the Greek islands.

With the help of Athens, the Ionians pushed the Persians from the coastal areas of Anatolia (Asia Minor) in 479 BC, although they still contolled much of the hinterland. A year later the Ionians cities joined the anti-Persian confederacy (known to historians as the Delian League) led by Athens. Ephesus contributed money rather than ships to the league.

In 334 BC Alexander the Great defeated the Persian king Darius III and "freed" the Greeks of Anatolia. After his death in 323 BC, his generals and relations (Διάδοχοι, the Diadochi, successors) waged war on each other for control of parts of his empire. In western Anatolia the main contenders were Lysimachus (360-281 BC), who ruled Pergamon and part of Thrace, the Seleucid dynasty (to become known as the Syrian kings) and the dynasty founded by Ptolemy I who ruled Egypt.

Eventually, in 301 BC Lysimachus took control of Ionia and decided to rebuild Ephesus. At the time the city was situated around the Temple of Artemis (see photos and information on Selcuk photo gallery 1, pages 3-4), on the plain northeast of Panayır Daği (2 km from the archaeological site of Ephesus). As ever in Ephesus' history, the silt deposited by the River Cayster (Greek, Κάυστρος, Kaystros; Turkish, Küçük Menderes, "Little Maeander"; see photo below) was driving the coastline further west. The old harbour was becoming untenable and the marshy plain was (and still is) prone to flooding.

And still the idea of moving the city was apparently so unpopular among some Ephesians, who were very attached to their temple (at the time still under construction), that Lysimachus is said to have had to force them to move by flooding the plain. This seems an odd move, even if it was technically possible, as the area around the temple must have been a vast building site at the time. This would have definitely not endeared him to the locals.

He even renamed the city Arsinoeia (Αρσινόεια), after his wife Arsinoe (316-270 BC, later became Queen Arsinoe II of Egypt), the scheming daughter of Ptolemy I. This never caught on, and after Lysimachus' death the city reverted to its old name.

Lysimachus' new site for the city lay between Mount Koressos (Κορησσός; today Bülbül Daği, Nightingale Mountain) to the south and the 396 metre high Mount Pion (Πίων; today Panayır Daği) to the north. To the east, the valley between the two hills is only about 300 metres wide, then opens up to the north and west towards the harbour. The new king planned the city and the new harbour according to the urban development principles conceived by Hippodamus of Miletus, and this layout remained unaltered for the next 500 years. |

|

| |

| |

After Lysimachus was defeated and killed by Seleucus I in 281 BC, the wars between the Diadochi continued. Although the Selucids now nominally ruled many of the territories formerly ruled by Lysimachus, one of his officers, Philetaerus (343-263 BC), became the de facto ruler of Pergamon and founded the Attalid dynasty which gained control of much of western Anatolia, eventually including Ephesus.

The Attalids allied themselves with the Romans who had become involved in the wars in Greece and Anatolia and were gaining increasing power and influence in the eastern Mediterranean. Pergamon effectively became a Roman client state. The last Attalid king Attalus III (170–133 BC) had no heir and bequeathed Pergamon and its territories to the Roman Republic.

However wars against the pretender Aristonicus, who claimed to be the illegitimate son of Eumenes II, and later Mithridates VI (the Great) of Pontus, meant that it took many years before Rome had the area under its control. Amidst the ensuing mayhem, the Ephesians, encouraged by the successes of Mithridates, revolted against Roman rule in 88 BC, and for a short time became self-governing.

Finally, in 86-85 BC the Romans prevailed, and the new Roman consul Lucius Cornelius Sulla imposed heavy financial punishments and tax burdens on the Asian cities for their revolt and for having taken the wrong side in the conflicts, forcing them into debt and poverty.

Emperor Augustus (reigned 27 BC - 14 AD) was more generous to Ephesus. He reformed the administration of the province of Asia (western Asia Minor) by initiating the rule by proconsul and moving the capital from Pergamon to Ephesus, thus beginning the city's greatest period of prosperity. It was to become the third largest city of the Roman Empire after Rome and Alexandria in terms of wealth, influence and population, estimated to have reached 200,000 during the second century AD.

The Romans brought their own gods, and even deified their emperors, but Artemis was still worshipped into Byzantine times. The Romans also enlarged the city's Great Theatre, though its main use switched from drama to brutal games with wild beasts versus prisoners, and gladiatorial duels, which explains the nearby site of a large gladiators' graveyard. Other architectural gems of the Roman era include the Bouleuterion (2nd century AD), the Temple of Hadrian (117-118 AD), the Library of Celsus (135 AD) and a number of enormous baths and gymnasium complexes.

From the beginning of the Christian era Ephesus became an important spiritual centre from where the new religion was spread, and later a place of pilgrimage. The Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist are said to have lived here, and Saint John is thought to have written the Gospel of John and finally died here (see further information and photos of the Basilica of Saint John in the Selçuk photo gallery). Saint Paul the Apostle also lived and may have been imprisoned here. Ephesus was one of the seven churches of Asia addressed in the Book of Revelation, written by Saint John of Patmos (see our pages on Patmos, Greece).

Hit by several earthquakes during the Roman period, the city was badly damged by a massive quake in 262 AD, and before it had time to recover, it was sacked by the Goths shortly after (262-2363 AD), during their massive invasion of the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean as far as Cyprus. It is thought that they destroyed much of Ephesus, including the Temple of Artemis. Rebuilding work was undertaken from the period of the Tetrarchy (284-312 AD), but the catastrophe marked the end of the city's days of wealth or splendour.

During the 4th century AD Emperor Constantine I rebuilt much of the city, including new public baths. A large 2nd century Roman basilica on the north side of the city was converted into the Aghia Maria church (Church of the Virgin Mary), where the Third Ecumenical Council, also known as the Council of Ephesus, was held in 431 AD during the reign of Emperor Theodosius II. Saint John's Basilica was built in the 6th century AD around the purported grave of Saint John the Theologian, in the area where Selçuk now stands, 3km northeast of the ancient city. The city was again partially destroyed by an earthquake in 614 AD.

Ephesus's importance declined as the harbour was gradually silted up by the River Cayster, until it was finally abandoned. Today the coastline is 5km from the site of Ephesus.

Other cities of the Greek world shared a similar fate (e.g. Miletus and Pella in Macedonia, Greece). It is partly because they were abandonded and forgotten (and also preserved in silt), that some of their buildings have survived the centuries, despite being plundered continually, especially for building material.

The few people who remained in the area lived around the Saint John's Basilica, and the settlement became known as Agios Theologos (Άγιος Θεολόγος, Holy Theologian).

The Seljuk Turks also settled there from the 12th century, and in 1304 the area was conquered by the Aydinid Turks, who built the impressive Isa Bey Mosque in 1374-1375. Later the Ottoman Turks conquered the whole of Anatolia and what had been the Byzantine Empire. Agios Theologos was known to the Turks as Ayasluğ (or Ayasluk). In 1914 the small town was was renamed Selçuk, in commemoration of the Seljuk Turks.

For over a century archaeologists have continued to unearth ever more of Ephesus' history and treasures, and reconstruct many of its buildings. It has been estimated that so far a mere 15-20% has been excavated, which means that the ancient city could still be hiding many surprises.

Many of the artifacts from Ephesus and the Temple of Artemis discovered by British and Austrian archaeologists in the 19th and early 20th centuries are now in the British Museum, London and the Ephesos Museum, Vienna. Other artefacts from Ephesus are also to be found in other museums around the world, including Berlin, Istanbul and Izmir. A fine selection of archaeological finds, especially more recently discovered objects, can be seen in the Ephesus Museum in the nearby town of Selçuk.

The character of the city as it now appears is predominantly Roman, with most of the buildings and monuments dating from the time of Emperor Augustus and his successors. There are few vestiges of the Greek city of the Hellenistic period. This is particularly evident in the case of the city's temples and shrines which, apart from the obvious example of the Temple of Artemis, are mostly dedicated to deified emperors and the Imperial cult, heroized Romans (for example the Memmius Monument) and imported deities such as Serapis and Isis who gained popularity during Roman times. There are still, however, signs that the more ancient gods of the Greeks, such as Apollo, Asklepius, Hermes, Dionysus, Herakles, Hestia, Demeter and Aphrodite, continued to be revered here (see, for example, reliefs of Hermes and Apollo's tripod on gallery page 12, and of Herakles on gallery page 16).

Greeks lived in the area of Ephesus for almost 3000 years, but most of the Greek population here were forced to leave during the population exchanges between Turkey and Greece following the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923. Some of the Greek refugees settled in Stoupi (Στουπί), a small village near Dion, Macedonia. The village was renamed Nea Ephesus (Νέα Έφεσος, New Ephesus) in 1953. Many Turkish refugees, migrating in the opposite direction, settled in Selçuk and surrounding area.

Detailed information about Ephesus' sights can be found with the photos in our Ephesus photo gallery.

For further local information about the Ephesus and Selçuk area, see: travel guide to Selçuk.

Further information for Turkey, including visa details, can be found in our introduction to Turkey. |

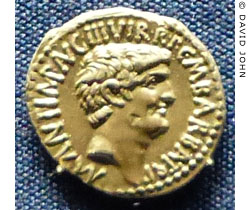

A dinar of Marcus Antonius and

Marcus Barbatius Pollio from

Ephesus. Roman period, 41 BC.

Münzkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. |

| |

A coin from the reign of Hadrian

showing the statue of Artemis

standing in the Artemision, Ephesus.

John Turtle Wood, Discoveries at

Ephesus, page 266. Longmans,

Green and Co., London, 1877.

See a photo of one

of these coins below. |

| |

A small marble altar with a relief

of Pan as a warrior. Roman period,

1st-2nd century AD. Found in 1869

by John Turtle Wood, near the

Temple of Artemis, Ephesus. [4]

Height 53 cm, width 24.13 cm.

British Museum, London.

Inv. No. 1872,0405.10

(Sculpture No. 1270.) |

| |

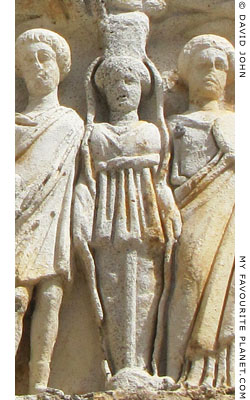

Detail of a marble frieze relief from

the "Temple of Hadrian", showing

Artemis standing between two

figures thought to be members of

the family of Emperor Theodosius I

(reigned 379-395 AD).

See Ephesus gallery page 24. |

| |

| |

A bronze coin of Ephesus showing the cult statue

of Artemis Ephesia in the Temple of Artemis.

Reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD).

Münzkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. |

| |

A cistophor coin of Ephesus showing

the Temple of Augustus and Roma.

Reign of Emperor Claudius, 41-54 AD.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum, Berlin. |

| |

The city Ephesus during the Roman period, as imagined by the British architect Edward Falkener,

who spent two weeks exploring and drawing the ruins in 1845, almost two decades before

John Turtle Wood (1821-1890) began the first archaeological excavations here in 1863.

|

The view is from Mount Koressos (Turkish, Bülbül Daği, Nightingale Mountain), looking north across the lower city. The harbour is on the left and Mount Pion (Panayır Daği) right. Below the Great Theatre, is the city's Lower "Commercial" Agora (the Tetragonos Agora).

Edward Falkener (1814-1896) visited Ionia alone 1844-1845 and spent two weeks at Ephesus.

"I visited the country in the years 1844 and 1845, when I travelled through all the most interesting portions of Asia Minor, visiting every ancient site, and exploring the ruins where these remains were considerable. Being alone, I had no opportunity of excavating at any place, and contented myself with taking such hasty notes and sketches as time would permit.

Here I remained one fortnight, notwithstanding that the ruins are situate on the borders of a pestilential marsh; and during this time succeeded in taking a general plan of the whole city, with detailed measurements of its buildings.

The temple has been swept away, and its very site is undistinguishable: and it was not till my return to England, and sitting down to search into the accounts of ancient writers, with a view to prepare a descriptive accompaniment to the drawings, that I became convinced of the true site which the temple had occupied, and longed to return to those classic regions, that I might reduce my conjectures into certainty: this, although fourteen years have elapsed since I wrote this monograph, I have not been permitted to accomplish, and the task must be left to some future explorer to see whether these conjectures are realized, and to raise for himself a reputation by discovering that temple, which was of such celebrity, that one in olden time thought to acquire reputation by destroying it."

Edward Falkener, Ephesus and the Temple of Diana, pages 12-13. Day & Son, London, 1862. |

|

|

| |

The River Cayster (Greek, Κάυστρος, Kaystros; Turkish, Küçük Menderes, Small Maeander)

southwest of Ephesus, surrounded by marshy land formed by alluvial deposits.

See a photo of two statues of river gods found in Ephesus,

thought to represent the Kaystros, on Ephesus gallery page 61. |

| |

The River Cayster runs into the Aegean Sea, 5 km southwest of Ephesus. |

| |

Ephesus

history |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. The Ionian League

The Ionian League (Ἴωνες, Iones; κοινὸν Ἰώνων, koinon Ionon; or κοινὴ σύνοδος Ἰώνων, koine synodos Ionon), also known as the Panionic League, was a confederation of twelve Ionian cities, founded in the mid 7th century BC.

The original twelve member cities were: Chios, Clazomenae, Colophon, Ephesus, Erythrae, Lebedus, Miletus, Myus, Phocaea, Priene, Samos and Teos.

Smyrna, originally an Aeolic city, joined the league after 650 BC.

The meeting place of the league was at Panionion (Πανιώνιον), at the foot of Mount Mykale, opposite Samos.

According to Herodotus, the various regions of Ionia had different dialects:

"They do not all have the same speech but four different dialects. Miletus lies farthest south among them, and next to it come Myus and Priene; these are settlements in Caria, and they have a common language; Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedos, Teos, Clazomenae, Phocaea, all of them in Lydia, have a language in common which is wholly different from the speech of the three former cities. There are yet three Ionian cities, two of them situated on the islands of Samos and Chios, and one, Erythrae, on the mainland; the Chians and Erythraeans speak alike, but the Samians have a language which is their own and no one else's. It is thus seen that there are four modes of speech."

Herodotus, Histories, Book 1, chapter 142, sections 3-4. At Perseus Tufts.

2. Prehistoric Ephesus

Prehistoric settlements around Ephesus include a complex site at Çukuriçi Höyük, where remains of Neolithic and Bronze Age occupation have been dated as far back as at least 6200 BC.

See, for example: I.1.1.1 Çukuriçi Höyük, Pages 5-9; I.2 Surveys zur Prähistorie im Umland von Pergamon, page 52. In: Dr. Sabine Ladstätter, Wissenschaftlicher Jahresbericht des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts (ÖAI) 2012, Pages 19-20. Vienna, 2013. PDF in German at the website of Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW, Austrian Academy of Sciences).

3. Dating of the Ephesus bee coin in Dresden

According to the museum's website, the reverse of the coin is inscribed with the name ΓΟΡΓΩΡΑΣ (Gorgoras), thought to be the name of a magistrate at Ephesus. Other numismatologists have dated coins struck under this magistrate to 370-360 BC.

4. Altar relief of Pan as a warrior

This very unusual relief depicts the rustic god Pan with a beardless human face and goat's legs, and wearing armour (helmet, cuirass, short sword and round shield). The small altar was discovered by John Turtle Wood in November 1869 while excavating around the Temple of Artemis, Ephesus. On the back is a crested snake; on the left side is a bucranium (bull's skull) surrounded by an olive wreath beneath rosettes; the right side has a snake, "roughly blocked out" (Smith) or partly erased.

The altar has been tentatively dated to 1st - 2nd century AD. It seems similar to the type of altars and votive offerings of Roman soldiers around the empire.

British Museum, London.

Inv. No. 1872,0405.10 (Sculpture No. 1270). Not on display.

Height 53 cm, width 24.13 cm.

John Turtle Wood, Discoveries at Ephesus, page 153. Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1877.

A. H. Smith, A Catalogue of Sculpture in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, British Museum Volume 2. British Museum, London, 1906. |

|

|

Photos, articles and map: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

Some of the information and photos in this guide to Ephesus

originally appeared in 2004 on davidjohnberlin.de. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

|