|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Daidalos |

|

| |

Daidalos

Ancient Greek mythology, religion and art

Daidalos (Δαίδαλος, often translated as Cunning Artificer, perhaps from δαιδάλλω, to work artfully; Latin, Daedalus) was a mythical or legendary sculptor, architect, engineer and inventor; the archetypal "father of artists".

Myths and legends concerning Daidalos are very ancient, and his association with King Minos of Crete and other mythical and legendary characters suggest that the tales point back to the period of the Minoan civilization, during the second millenium BC. However, they were first written down at least 700 years later, from the time of Homer (8th - 7th century BC ?), and most surviving texts are from Roman times, for example Bibliotheca historica by Diodorus Siculus (written 60-30 BC), the Aeneid by Virgil (written 29-19 BC) and Metamorphoses by Ovid (completed in 8 AD). These authors are assumed to have embellished and added to more ancient stories, perhaps also conflating tales originally told of various other characters.

The stories about Daidalos give the impression that he was a universal genius, the consummate artist and practical thinker, comparable to Leonardo da Vinci.

"In natural ability he towered far above all other men and cultivated the building art, the making of statues, and the working of stone. He was also the inventor of many devices which contributed to the advancement of his art and built works in many regions of the inhabited world which arouse the wonder of men.

In the carving of his statues he so far excelled all other men that later generations invented the story about him that the statues of his making were quite like their living models; they could see, they said, and walk and, in a word, preserved so well the characteristics of the entire body that the beholder thought that the image made by him was a being endowed with life.

And since he was the first to represent the open eye and to fashion the legs separated in a stride and the arms and hands as extended, it was a natural thing that he should have received the admiration of mankind; for the artists before his time had carved their statues with the eyes closed and the arms and hands hanging attached to the sides."

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, Book 4, chapter 76, sections 1-3.

In the works of Homer, the word "daidala" (δαίδαλα) is used to mean objects that are finely-crafted, including armour, bowls, furnishings and jewellery. It may well be that Greeks came to believe that many excellent ancient objects and buildings, still in existence or known to have existed, were created by one person whom they called Daidalos.

Modern historians have given the name Daedalic to types of early Archaic Greek sculpture from around 650-600 BC, known as the "Daedalic Period" (see photos, above right).

Pausanias, the second century AD Greek travel writer, noted works which had been attributed to Daidalos and his "pupils" or "sons" Dipoenos and Skyllis:

"Now the sanctuary of Athena Chalinitis [at Corinth] is by their theatre, and near is a naked wooden image of Herakles, said to be a work of Daedalus. All the works of this artist, although rather uncouth to look at, are nevertheless distinguished by a kind of inspiration."

Pausanias Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 4, section 5.

"On the road from Corinth to Argos is a small city Cleonae... Here there is a sanctuary of Athena, and the image is a work of Scyllis and Dipoenus. Some hold them to have been the pupils of Daedalus, but others will have it that Daedalus took a wife from Gortyn, and that Dipoenus and Scyllis were his sons by this woman."

Pausanias, Book 2, chapter 15, section 1.

Dipoenos and Skyllis are thought to have been sculptors from Crete, perhaps brothers, working in the early 6th century BC at Sikyon, in the northeastern Peloponnese. The stories told about them as "pupils" or "sons" of Daidalos in the time of Pausanias, may have been due to a confusion of the myths and legends concerning Daidalos, or a result of traditional ways of speaking, perhaps in the same way as doctors were often referred to as "sons of Asklepios", the Greek god of healing.

As with many myths about prehistoric Crete, for example concerning Erechtheos and Theseus, there was a link with Athens, and Daidalos was said to have been Athenian (even a great-grandson of King Erechtheos) who went to Crete to work for King Minos. According to Diodorus, he had fled from Athens to escape justice after murdering his nephew and pupil Thalos, because he was envious of his pupil's prodigious talent which he feared would eclipse his own. Diodorus tells us that Thalos invented the potter’s wheel and the saw.

The first literary mention of Daidalos is by Homer who mentions "the dancing floor... Daidalos contrived for fair-haired Ariadne [Minos' daughter] in broad Knossos" (Iliad, Book 18).

Some translators have rendered "dancing-floor" (E. V. Rieu) as "labyrinth" (William Cowper) or even "a figured dance" (Alexander Pope), suggesting that he either designed a complex path for dancers or invented the form of the dance itself.

More famously, he is said to have designed the Labyrinth for Minos as a prison for the Minotaur.

When Minos imprisoned Daidalos and his son Ikaros (Ἴκαρος), he made wings for their escape (see below). During their flight, Ikaros fell into the sea and drowned. However, Daidalos flew on and made his way to southern Sicily where he took refuge with King Kokalos (or Cocalos, Κώκαλος) of Kamikos. Minos pursued him there but was either murdered by Kokalos, or in another version of the tales, founded his own city on Sicily.

In Sicily, according to Diodorus Siculus, Daidalos "constructed certain works which stand even to this day".

He constructed a kolumbethra (swimming bath or reservoir) near Megaris.

He designed the city of Kamikos (Camicus) near Akragas (today Agrigento), which "was the strongest of any in Sicily and altogether impregnable to any attack by force; for the ascent to it he made narrow and winding, building it in so ingenious a manner that it would be defended by three or four men. Consequently Kokalos built in this city the royal residence, and storing his treasures there he had them in a city which the inventiveness of its designer had made impregnable."

He transormed a cave in the territory of Selinous (today Selinunte), in which volcanic heat produced steam, into a steam bath where "those who frequented the grotto got into a perspiration imperceptibly because of the gentle action of the heat, and gradually, and actually with pleasure to themselves, they cured the infirmities of their bodies without experiencing any annoyance from the heat".

At Eryx (today Erice) in northwest Sicily, "where a rock rose sheer to an extraordinary height and the narrow space, where the temple of Aphrodite lay [Eryxinian Aphrodite, the Greek name later given to a goddess of the indigenous Sicilians], made it necessary to build it on the precipitous tip of the rock, he constructed a wall upon the very crag, by this means extending in an astonishing manner the overhanging ledge of the crag.

Moreover, for the Aphrodite of Mount Eryx, they say, he ingeniously constructed a golden ram, working it with exceeding care and making it the perfect image of an actual ram.

Many other works as well, men say, he ingeniously constructed throughout Sicily, but they have perished because of the long time which has elapsed."

In the 3rd or 4th century AD the Sophist Kallistratos (Καλλίστρατος), when praising a bronze statue of Dionysus by Praxiteles, compared the then still extant works attributed to the 4th century BC sculptor with the legendary statues said to have been made by the ancient master Daidalos.

"Daedalus, if one is to place credence in the Cretan marvel, had the power to construct statues endowed with motion and to compel gold to feel human sensations, but in truth the hands of Praxiteles wrought works of art that were altogether alive." [1] |

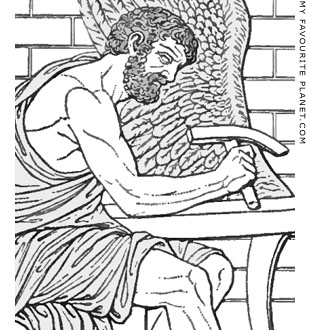

Detail of a Roman relief depicting Daidalos

making wings for his escape from Crete.

See details below. |

| |

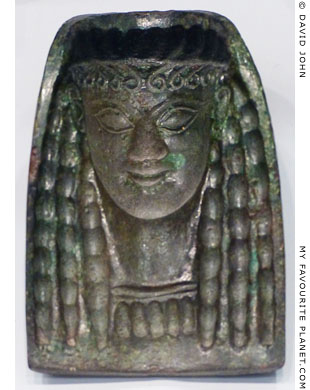

A typical sculpture of the Daedalic style,

around 630-620 BC. Height 40 cm.

A fragment of a limestone metope from

the temple of Athena on the Mycenae

acropolis, depicting the upper body of a

woman, probably a goddess. She draws

a cloak over her head, a gesture of

modesty and rank, characteristic of the

goddess Hera. Late Daedalic, probably

a product of a Corinthian workshop.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 2869. |

| |

Terracotta scent bottle

in the form of a female bust.

Made in East Greece about 610-55 BC.

From Kamiros, Rhodes.

The figure wears a painted necklace with

ornaments in the form of pomegranates.

Her hair is arranged in the Daedalic style.

British Museum.

Inv. No. GR 1860.4-2.24 (Terracotta 1607). |

| |

The inside of a bronze mould for making

terracotta figurines of the Daedalic type.

From the Sanctuary of Olympia,

late 7th - early 5th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 6139. |

| |

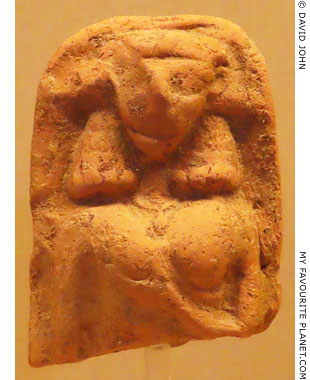

A fragment of a terracotta plaque

with a Daedalic style relief thought

to depict a goddess.

From Abdera Thrace, northeastern

Greece. 7th century BC.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

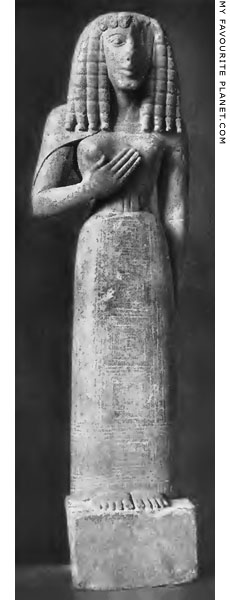

The "Nikandre Kore", a marble kore

statue a standing female in the

Daedalic style, perhaps depicting

Artemis. One of the earliest Greek

monumental statues in stone.

Around 650 BC. Found in 1878 in the

sanctuary of Artemis in Delos. Inscribed

on the left thigh is a dedication to

Apollo by a woman named Nikandre

(Νικάνδρη) from Naxos. Parian marble.

Height 175 cm. [2]

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 1. |

|

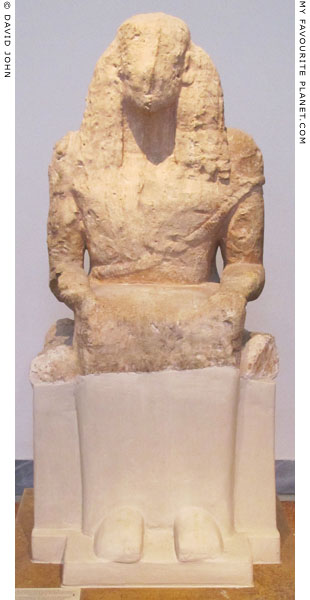

A statue of a seated female, perhaps

a goddess, in the Daedalic style.

The figure wears a himation (cloak)

over a long chiton (tunic).

Around 630 BC. Found at Agiorgitika (Αγιωργητικα) near Tripolis in the

Peloponnese. Local stone.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 57. |

|

| |

Limestone Koure statuette, known as

"La Dame d'Auxerre" (Lady of Auxerre),

with traces of polychrome decoration.

Around 640-630 BC. Provenance unknown. Thought to be from Crete. Height 75 cm.

Discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist and

art historian Maxime Collignon (1849-1917)

in a storeroom of the Municipal Museum of

Auxerre, Burgundy, France. It was acquired

from the museum by the Louvre in 1909

in exchange for a painting by Harpignies

(1819-1916). As with other Archaic kore

statues, it is not known whether the figure

depicts a goddess or a woman, a votive

offering or a funerary monument.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. MA 3098.

Woldemar Graf Uxkull-Gyllenband, Archaische

Plastik der Griechen, Band 3, Abbildung 5.

Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin, 1920. |

|

Bronze statuette of a kouros in the

Daedalic style, with hair in horizontal

layers and a broad belt.

From Delphi, Greece. Made in a

Cretan workshop, around 620 BC.

Delphi Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 2527. |

|

| |

Ceramic pinax (plaque) with a relief of

a standing female of the "Dama 2" type,

a variation of the "Dama di Sibari"

(Lady of Sybaris) figures.

625-600 BC. From Sybaris (Σύβαρις), Gulf

of Taranto, Magna Graecia (today Sibari,

Calabria, Italy), founded in 720 BC by

Greek colonists from Achaea and Troezen

in the Peloponnese. Found at Timpone

della Motta, Sibari. Possibly made in a

local workshop. Height 18 cm.

The "Dama 2" figures, originally painted,

are simpler, usually smaller than the more

elaborately modelled "Dama 1" type. The

frontally facing figure wears a decorated

polos, has a row of snail-shell curls along

the forehead and three tresses hanging

to either side. Her face is expressionless,

eyes wide open and her arms are held

straight against her sides. Around her

shoulders are what appear to be the

corners of a cloak, although they may be

sleeves of her tight-fitting peplos, which

is gathered at the waist by a girdle. Her

small feet peep from beneath the hem

of the garment.

It has been suggested that such figures

were meant to be replicas of statues, and

may represent a goddess, perhaps Athena.

National Archaeological Museum of Sibaritide. |

|

Small bone plaque with the figure

of a goddess in the Daedalic style.

From Megara Hyblaea, Sicily.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum,

Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 84818. |

|

| |

A fragment of a terracotta plaque with a relief

of two female figures in the Daedalic style.

From Corinth. 3rd quarter of the 7th century BC.

Corinth Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. KT 27-1. |

| |

A labyrinth incised on the rear of a Linear B clay tablet from the Mycenaean palace

(the so-called "Palace of Nestor) of Pylos, Messenia, Greece. 13th century BC.

The tablet was part of a large archive of clay tablets inscribed with administrative

records inscribed in the Linear B script, discovered at Pylos in 1939 by the American

archaeologist Carl W. Blegen (1887-1971). Linear B was deciphered in 1952 by the

British architect Michael Ventris with the assistance of philologist John Chadwick.

They proved that the script was written in an early form of the Greek language.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Cn 1287. |

| |

Gold plaque pendant with a depiction of the "Mistress of Animals"

in the Daedalic style. From Kamiros, Rhodes, 720-650 BC.

The figure, thought by some scholars to depict Artemis, wears a long chiton,

has sickle-shaped wings and holds in each hand a lion by a rear leg or tail.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN 1896-1908 G.441. |

| |

Gold necklace plaques with Daedalic female heads.

From Rhodes, second half of the 7th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Helen and Antonios Stathatos Collection. |

| |

|

|

|

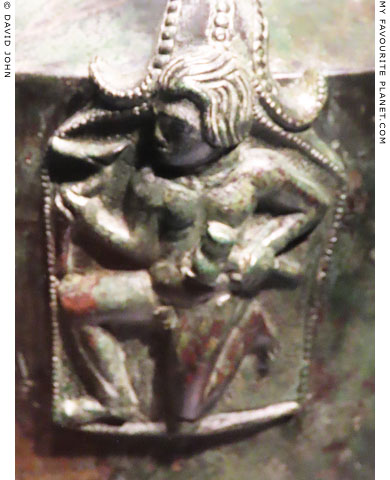

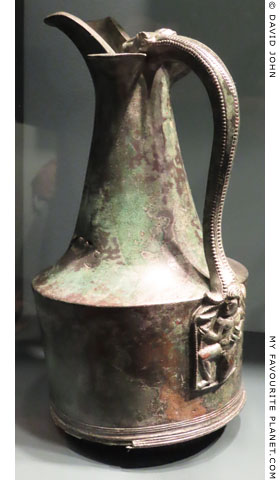

A relief thought to depict Daidalos on the plate of the handle of a bronze beaked jug.

The naked figure holds a hammer in his left hand. The object in his right hand is

described by the museum label as a plane, but it looks more like an anvil.

Circa 400-350 BC. From Etruria, Italy.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 17.768. |

|

| |

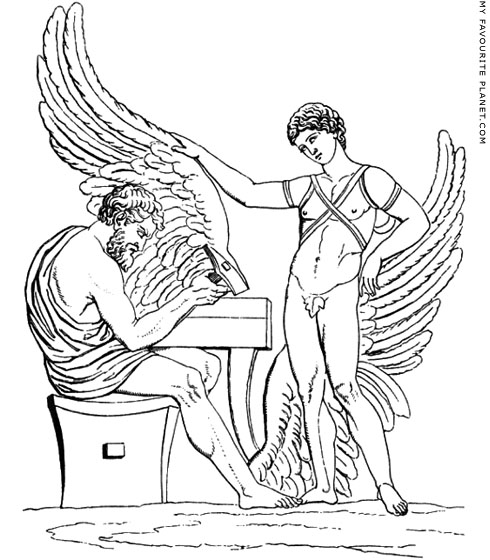

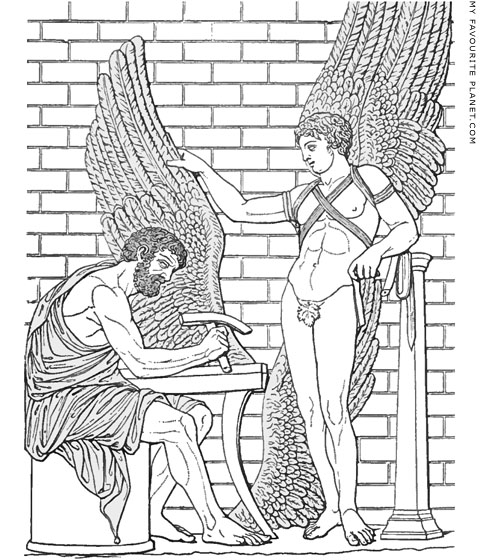

Drawing of a marble relief of Daidalos and Ikaros in the Villa Albani, Rome.

Daidalos, assisted by his son Ikaros, prepares the wings of feathers, thread

and wax that will help them escape from imprisonment by Minos on Crete.

Source: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (1845-1923), Ausfürliches Lexikon

der griechisches und römisches Mythologie Band I, page 934

(page 467 of 721). B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1884-1890. At archive.org.

First published in: August Emil Braun (1809-1856), Zwölf Basreliefs griechischer Erfindung

aus Palazzo Spada dem capitolinischen Museum und Villa Albani, chapter 12. Institut für

archaeologische Correspondenz. Salviucci, Rome, 1845. At the University of Cologne.

|

Two similar marble reliefs depicting Daidalos and Ikaros are recorded in the museum of the Villa Albani, first reported by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in 1767 (with an engraving) and other writers in the 19th century [3]. The first relief, Inv. No. 1009 (drawing above), was restored from a few fragments found on the slope of the Palatine Hill near the Circus Maximus. It was photographed by the Fratelli Alinari (Alinari brothers) in the 1920s.

The second relief, Inv. No. 164 (see drawing below), found later in the area of Naples, was more complete and appeared to confirm the work of the restorer of the first relief. The drawing above, probably copied from a photo by James Anderson (1813-1877) taken around 1890 and now in the Alinari Archives [4], appears to be of this relief. It has been published in a number of books since the 1890s, merely titled "Daedalus and Icarus, Rome, Villa Albani" (or similar) without any further details. Plaster casts were made of the relief, and one is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [5], which also has a (modern?) marble relief of this subject (see photo below).

Strangely, I have yet to find any more recent photos or information about either of the reliefs. Much of the Albani Collection has been dispersed to other museums (for example, the Capitoline Museums, Naples, Dresden and the Louvre), and it is not clear whether they are still in the Villa Albani or elsewhere.

The story of Daidalos making wings in order to escape inprisonment by King Minos of Crete is well known. As he and his son Ikaros flew away over the Aegean, Ikaros flew too close to the sun, the wax that held the feathers of his wings melted and he fell into the sea and drowned. The small island of Ikaria, west of Samos, was said to have been named after him. Daidalos then flew on to freedom.

"Alongside Samos lies the island Icaria (νῆσος Ἰκαρία), whence was derived the name of the Icarian Sea (Ἰκάριον πέλαγος). This island is named after Icarus the son of Daedalus, who, it is said, having joined his father in flight, both being furnished with wings, flew away from Crete and fell here, having lost control of their course; for, they add, on rising too close to the sun, his wings slipped off, since the wax melted."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, section 19. Loeb Classical Library edition, translated by H. L. Jones. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and William Heinemann, London, 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias related quite another version of the tale of Daidalos' escape from Crete when discussing him as an artist, who the Thebans believed made their ancient cult statue of Herakles. In this version it was not wings that Daidalos invented and made but sails for a boat.

"Here is a sanctuary of Heracles. The image, of white marble, is called Champion, and the Thebans Xenocritus and Eubius were the artists. But the ancient wooden image is thought by the Thebans to be by Daedalus, and the same opinion occurred to me.

It was dedicated, they say, by Daedalus himself, as a thank-offering for a benefit. For when he was fleeing from Crete in small vessels which he had made for himself and his son Icarus, he devised for the ships sails, an invention as yet unknown to the men of those times, so as to take advantage of a favorable wind and outsail the oared fleet of Minos. Daedalus himself was saved, but the ship of Icarus is said to have overturned, as he was a clumsy helmsman.

The drowned man was carried ashore by the current to the island, then without a name, that lies off Samos. Heracles came across the body and recognized it, giving it burial where even to-day a small mound still stands to Icarus on a promontory jutting out into the Aegean. After this Icarus are named both the island and the sea around it."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 11, sections 4-5. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

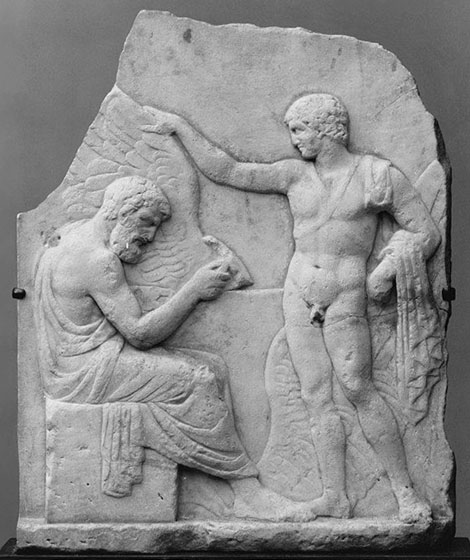

Drawing of the second marble relief of Daidalos and Ikaros in the

Villa Albani. Ikaros leans with his left elbow on a pillar, suggesting

that the relief may represent a marble statue group.

Source: Oskar Seyffert, A dictionary of classical antiquities,

mythology, religion and art (Third edition in English), page 171.

Swan Sonnenschein and Co., London, 1895. At archive.org. |

| |

A marble relief of Daidalos and Ikaros in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Perhaps a modern work. Height 69.9 cm, width 55.7 cm.

Inv. No. 1972.118.115 (not on display). Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971.

Public Domain photo. Source: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255426 |

| |

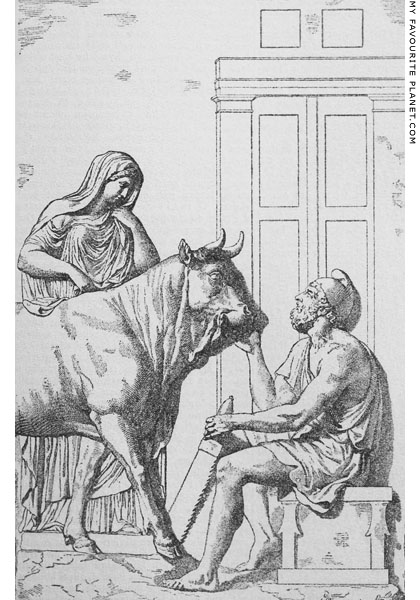

Drawing of a marble relief of Daidalos constructing the hollow

wooden cow for Minos' wife Pasiphae (Πασιφάη, wide-shining).

Corridoio dei Bassorilievi, Palazzo Spada, Rome.

Source: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (1845-1923), Ausfürliches Lexikon

der griechisches und römisches Mythologie Band I, page 935

(page 468 of 721). B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1884-1890. At archive.org.

First published in: August Emil Braun (1809-1856), Zwölf Basreliefs griechischer Erfindung

aus Palazzo Spada dem capitolinischen Museum und Villa Albani, Tafel V. Institut für

archaeologische Correspondenz. Salviucci, Rome, 1845. At the University of Cologne.

|

One of eight ancient marble reliefs found in 1620 during the restoration by Cardinal Verallo of the church of S. Agnese Fuori le Mura, Rome. They had been used as building material for the church steps. Like the reliefs of Daidalos and Ikaros (see above), the restored work attracted the attention of Winckelmann and other scholars during the 18th and 19th centuries [6], and was photographed by James Anderson around 1890, but since has been scarcely mentioned.

According to the Alinari Archives website, the low relief has been dated to the 1st - 3rd century AD, although it has also been referred to as Hellenistic. The treatment of the figures is intense, detailed and realistic with Classicistic features, particularly those of the veiled Pasiphae, which is reminiscent of the female figures on Classical Athenian grave steles. Daidalos is shown wearing a Phrygian cap and holding a saw, perhaps an allusion to his murder of his nephew and pupil Thalos who, according to Diodorus Siculus, invented the saw.

A 1st century AD fresco (Pompeiian Fourth Style), from the northern wall of the triclinium in the Casa dei Vettii (VI 15,1) in Pompeii, depicts Daedalus (Daidalos) presenting the wooden cow to Pasiphae. |

|

|

| |

| Daidalos |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Kallistratos on Daidalos and Praxiteles

Callistratus, Descriptions, No. 8. On the statue of Dionysus (by Praxiteles) (ή εἷς τὸ Διόνυσου ἄγαλμα). In: Philostratus The Elder Imagines, Philostratus The Younger Imagines, Callistratus Descriptions, pages 402-407. Loeb Classical Library edition L256, in Greek with an English translation by Arthur Fairbanks. William Heinemann Ltd, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1931. At the Internet Archive.

2. The "Nikandre Kore"

As with other Archaic kore and kouros statues, it is not known whether it was meant to depict a deity, or the person for whom the statue was made, or was a generic figure. It has been suggested that it depicted either a goddess, possibly Artemis, or Nikandre, perhaps as a priestess. Some sources state that it was found in the Delian sanctuary of Artemis, while others claim it is from "in front of the temple of Apollo". There were thought to have been three separate temples of Apollo, built and rebuilt over different historical periods, and the sanctuary of his twin sister Artemis is a little further north.

Likewise, most authors write that the statue was dedicated to Apollo, while others claim it was for Artemis. The dedication is inscribed in boustrophedon (βουστροφηδόν, ox-turning, as in ploughing a field), with the first line written left to right, and the second line from right to left. It has been restored as:

Νικάνδρη μ’ἀνέθεκεν ℎ(ε)κηβόλοι ἰοχεαίρηι | κούρη Δεινο-

δίκηο το͂ Ναχσίου ἔχσοχος ἀλ(λ)ήον | Δεινομένεος δὲ κασιγνέτη

Φράχσου δ’ἄλοχος μ[ήν?].

Nikandre dedicated me to the far-shooter of arrows, the excellent daughter (kore) of Deinomenes the Naxian, sister of Deinomenes, wife of Phraxos n(ow?).

Inscription ID 2 (also Jeffery, Local Scripts, LSAG 303,2).

Both Apollo and Artemis were shooters of arrows, that is archers (see, for example, Niobe). Apollo is also referred to as "Farshooter" on the dedicatory inscription from Delos signed by the sculptor Archermos of Chios, associated with the Archaic statue of Nike, circa 550 BC (see Nike).

3. Reliefs of Daidalos and Ikaros in the Villa Albani

Restored fragments of a marble relief of Daidalos and Ikaros.

Found among remains of other reliefs, perhaps from an imperial palace on the Palatine Hill, Rome.

Flavian period, end of the 1st century AD, perhaps a copy of a Greek 5th century BC original.

Height 178 cm, width 116 cm.

Villa Albani, Rome. Inv. No. 1009.

See: arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/27964. At the University of Cologne (in German).

Restored marble relief of Daidalos and Ikaros. Rosso Antico (pink marble).

From "the Kingdom of Naples". 1st - 2nd century AD (?).

Height 78 cm, width 60 cm.

Villa Albani, Rome. Inv. No. 164.

See: arachne.uni-koeln.de/item/objekt/27965. At the University of Cologne (in German).

See also:

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Monumenti antichi inediti spiegati ed illustrati da Giovanni Winckelmann. Rome, 1767.

Text in Volume II, Chapter XI, Dedalo ed Icaro, pages 129-130.

Engraving of Inv. No. 164: Volume I, plate 95.

Both volumes at Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Wolfgang Helbig, Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen klassischer Alterthümer in Rom, Band II: Die Villen, das Museo Boncompagni, der Palazzo Spada, die Antiken der vatikanischen Bibliothek, das Museo delle Terme. Pages 49-50, No. 777 (1009), and page 64, No. 800 (164). Karl Baedeker, Leipzig, 1891. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

A recent publication has an old photo of a plaster cast of the relief identified here as Inv. No. 1009, but refers to it as Inv. No. 164. Either I have made an error or they have.

"Relief mit Daidalus und Ikarus, Abguss, erworben in den 1780er Jahren (Original Rom, Sammlung Albani, Inv.-Nr. 164), Antikensammlung SMB, Inv.-Nr. I.G. 163"

("Relief with Daidalos and Ikaros, plaster cast, acquired in the 1780s (original in Rome, Albani Collection, Inv. No. 164), Antiquities Collection, State Museums Berlin (SMB), Inv. No. I.G. 163.")

Nele Schröder-Griebel, Berlin und Bonn. Strategien von Aufbau und Aufstellung der Abguss-Sammlungen, page 44, Fig. 2. In: Christina Haak and Miguel Helfrich (editors), Casting: Ein analoger Weg ins Zeitalter der Digitalisierung? Ein Symposium zur Gipsformerei der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin Casting, 26. - 27. November 2015 (Casting: A way to embrace the digital age in analogue fashion? A symposium on the Gipsformerei of the Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, 26 - 27 November 2015), pages 40-51. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2016. Free PDF at arthistoricum.net, Heidelberg University Library.

4. Photos of the Villa Albani Daidalos and Ikaros reliefs in the Alinari Archives

Photos of both reliefs at the Alinari Archives:

Inv. No. 1009, listed as Image ID: ACA-F-027607-0000.

Inv. No. 164, listed as Image ID: ADA-F-001889-0000.

See: www.alinariarchives.it/en/search

5. Cast of a Villa Albani Daidalos and Ikaros relief in the Met

See: Catalogue of the collection of casts, second edition, page 134, No. 884 (no illustration). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1910. At archive.org.

A cast of Inv. No. 1009 is in the War Museum, Athens.

See photo by Robert Wallace at: flickr.com/photos/robwallace/2424875747/in/photostream/

6. The Daidalos and Pasiphae relief in the Palazzo Spada

See:

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Monumenti antichi inediti spiegati ed illustrati da Giovanni Winckelmann. Rome, 1767.

Text in Volume II, Chapter X, Dedalo e Pasifae, pages 127-129.

Engraving: Volume I, plate 94.

Both volumes at Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Wolfgang Helbig, Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen klassischer Alterthümer in Rom, Band II: Die Villen, das Museo Boncompagni, der Palazzo Spada, die Antiken der vatikanischen Bibliothek, das Museo delle Terme. page 165-166, and pages 167-168, No. 939. Karl Baedeker, Leipzig, 1891. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Photo at the Alinari Archives: ADA-F-001986-0000. www.alinariarchives.it/en/search |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|