|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Medusa > part 4 |

|

back |

Medusa – part 4 |

|

Page 4 of 8 |

|

|

| |

| Gorgoneion antefixes |

| |

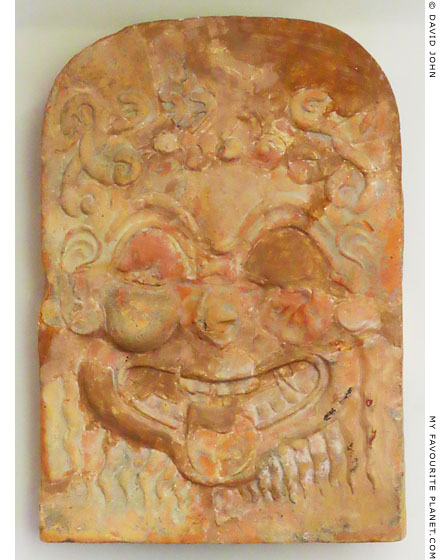

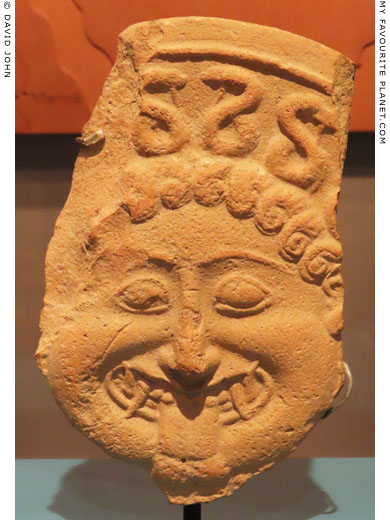

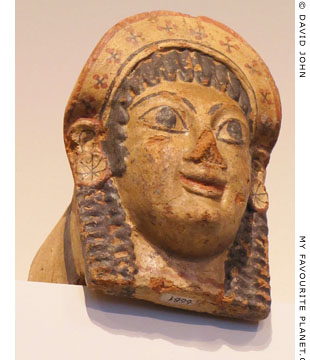

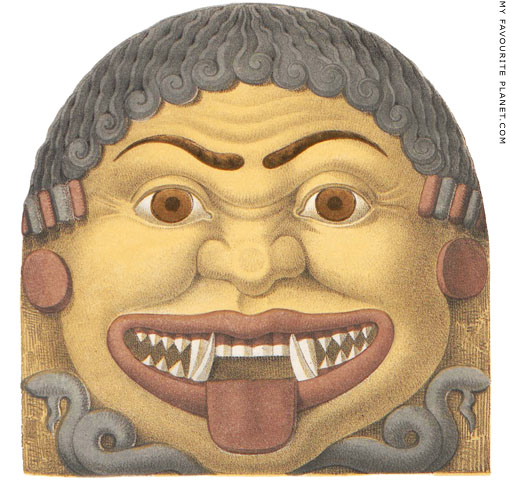

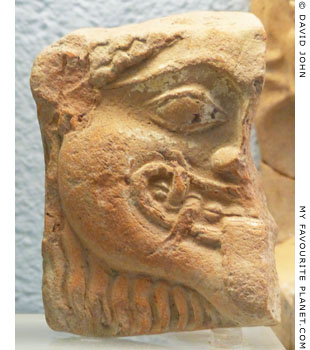

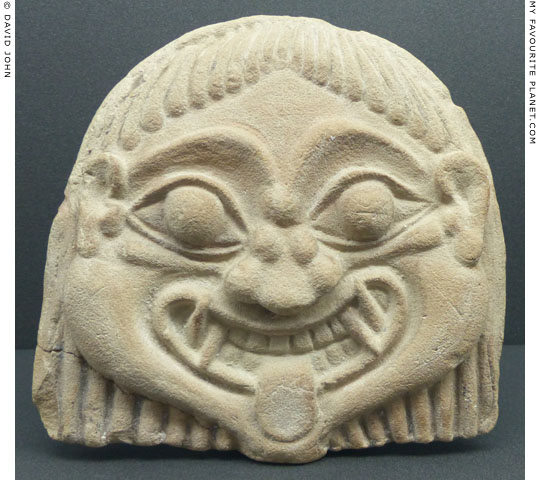

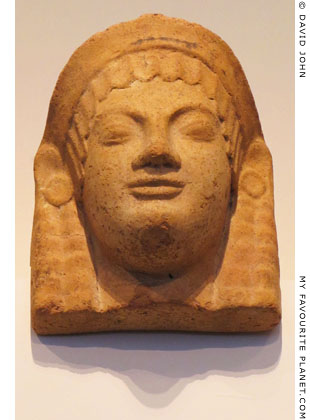

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix (decorated end of a roof tile)

of the "horrid type" with a "beard".

According to the museum labelling, around 580 BC, although the

official guide book (see note in Medusa part 3) states 620-600 BC.

Found in 1914 at the Archaic Temple of Hera Akraia, on the Mon Repos estate, Corfu,

in the area now known as Palaiopolis (Παλαιόπολης, Old City), the site of the ancient

city Korkyra (Κόρκυρα), a colony of Corinth. This antefix was made about the same

time as the Gorgon pediment of the nearby "Temple of Artemis" (see part 3),

during or just after the rule of the Corinthian tyrant Periander (circa 627-585 BC).

Mon Repos Museum, Corfu. Inv. No. MR 730.

Formerly in the Corfu Archaeological Museum.

This is one of three surviving antefixes from the Temple of Hera exhibited in the museum.

The second is of white limestone with a lion's head (MR 1) that served as a water spout;

the third is a fragmentary terracotta with part of a female head in the Daedalic style

(MR 21), which the archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld thought was also a Gorgoneion.

|

An antefix (from Latin, antefixus; in Greek, ακροκέραμο or ακροκέραμος, akrokeramos) is an ornamental ceramic plaque [1] covering the end of a roof tile (kalypter) which covered the lower edge of a wooden framed, ceramic tiled roof or the apex of a gable (sima) of a temple, mostly during the Archaic period. Rows of such antefixes, usually in the form of heads (often referred to as protomes [2]) of mythical figures, often decorated the sides of roofs. Antefixes covering apex tiles were usually larger. See the reconstruction drawing in Medusa part 2, showing the roof of the Archaic wooden temple of Apollo at Thermon, central Greece, decorated with a row of antefixes.

The technique is thought to have been invented in Corinth (but see note in Medusa part 2), and appears to have spread to other Greek cities rapidly, and was already in use in Etruria by the 7th century BC. [3] It was used on several temples in Sicily, where Gorgoneions were among the most common antefix motifs.

A now-lost primitive Archaic antefix found in Thessaloniki, northern Greece, is said to have resembled the masks found at Tiryns (see Medusa part 2), was thus dated to the 7th century BC and thought to be a Gorgoneion. Unfortunately, I have so far been unable to discover more information about the object or a photo or drawing of it. However, if it was a Gorgoneion it would have probably been the earliest example of the motif in Greek architecture. [4]

The antefixes and tiles below show a wide variety on the Gorgon theme, and artists around the Greek world - the mainland and islands of Greece, Thrace, Ionia (East Greece), Magna Graecia (Italy) and Sicily - depicted her in very different ways between the 7th and 4th centuries BC. Although there was a general tendency towards less hideous and more attractive Gorgons, the Archaic types continued into the 4th century BC, as can be seen from an Archaistic antefix from Gela, Sicily below. Antefixes based on Greek models, perhaps from Greek-made moulds, were produced by Etruscans and other Italic peoples (see note 3 and photos below). A fragment of a terracotta Gorgoneion in Milan, believed to be part of an antefix (see below), is dated as late as the 1st century AD.

With the development of architecture from the Classical period (5th - 4th century BC) and the replacement of wood and ceramics with stone, including stone roof tiles, antefixes gradually ceased to be employed. Rows of decorative stone heads (similar to gargoyles), often of lions, continued to be used as water spouts on the edges of roofs (eaves or sima) along the sides of temples and other buildings.

See also examples of Gorgons as architectural decoration

in Medusa part 2 and Medusa part 3. |

|

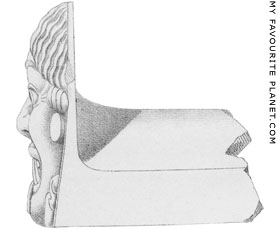

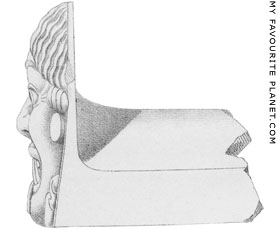

The right side of the Gorgoneion

antefix from the Temple of Hera

in Corfu, showing its construction,

the shallow relief of the decoration

and part of the attached roof tile. |

|

| |

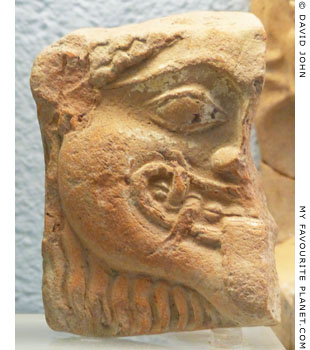

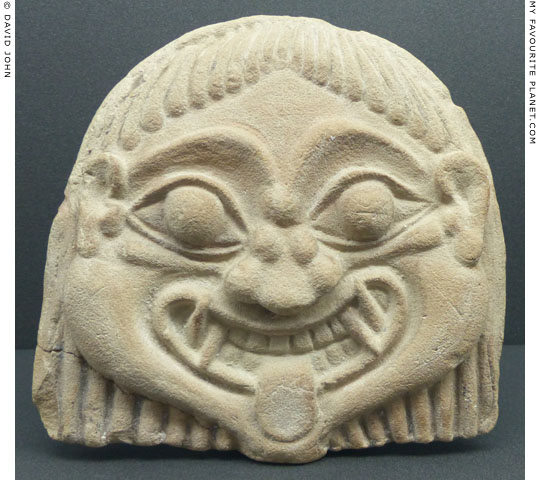

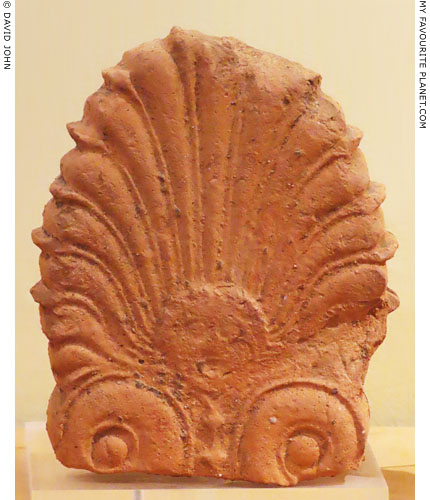

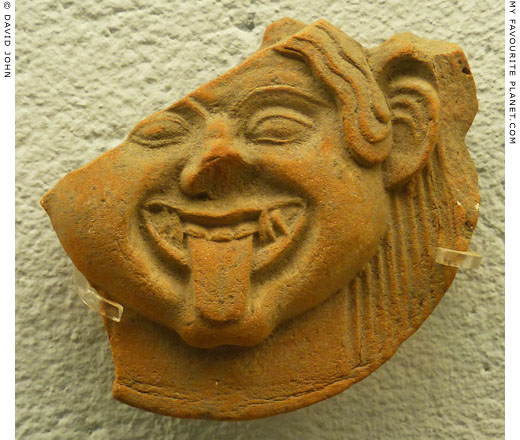

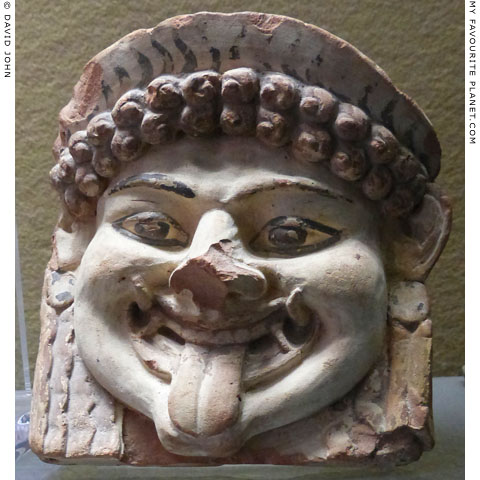

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type".

2nd half of the 6th century BC. From Korkyra (Corfu), a colony of Corinth.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

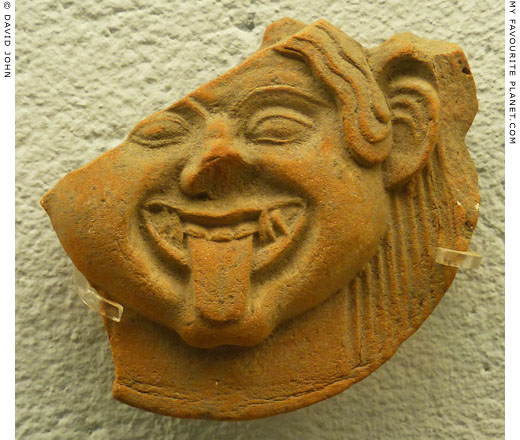

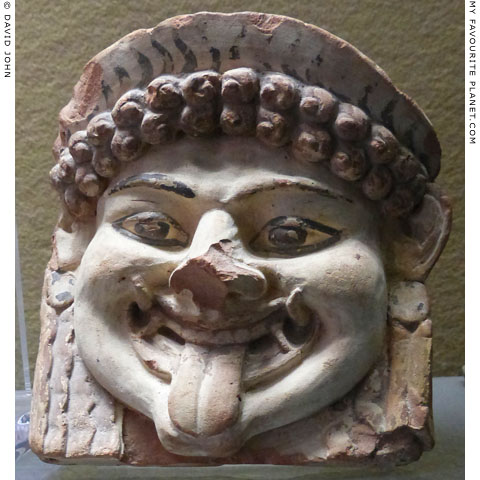

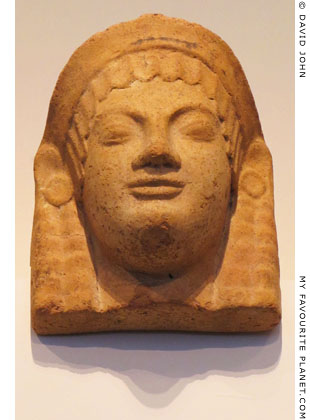

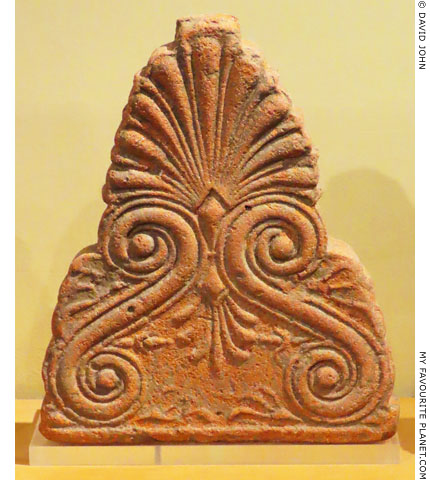

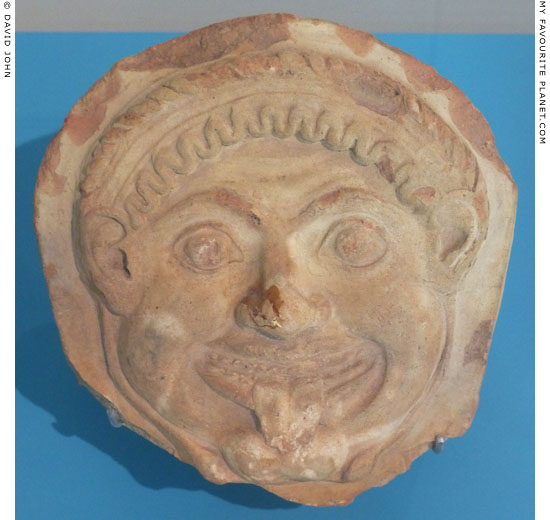

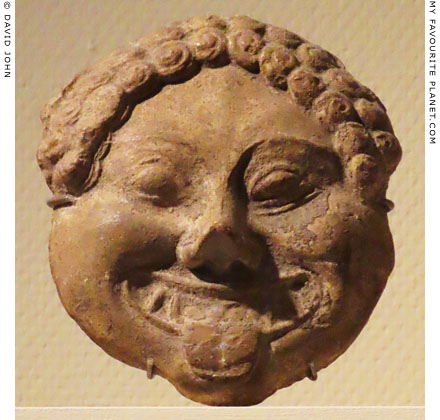

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "beautiful type".

4th century BC. From Corfu.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

|

A very similar antefix, dated to the second half of the 5th century BC, was found in Taranto, southern Italy. [6]

"Beauty", it seems, is not only in the eye of the beholder, but also a matter of taste, fashion and cultural milieu. In a witty dialogue written by the Syrian essayist and satirist Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανός ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, circa 125-180 AD), one of the characters, Lycinus (probably Lucian himself), tells his friend that he has just almost been turned to stone by the sight of a woman's beauty. The piece is thought to have been written in 162/163 AD in praise of Panthea, the mistress of Emperor Lucius Verus. As usual with Lucian, the reader is seldom sure how firmly his tongue was in his cheek, but his interlocutors appear to have stumbled on a fascinating aspect of the power of the Gorgon's stare.

"Lycinus: Polystratus, I know now what men must have felt like when they saw the Gorgon's head. I have just experienced the same sensation, at the sight of a most lovely woman. A little more, and I should have realized the legend, by being turned to stone; I am benumbed with admiration.

Polystratus: Wonderful indeed must have been the beauty, and terrible the power of the woman who could produce such an impression on Lycinus. Tell me of this petrifying Medusa. Who is she, and whence? I would see her myself. You will not grudge me that privilege? Your jealousy will not take alarm at the prospect of a rival petrifaction at your side?

Lycinus: Well, I give you fair warning: one distant glimpse of her, and you are speechless, motionless as any statue. Nay, that is a light affliction: the mortal wound is not dealt till her glance has fallen on you. What can save you then? She will lead you in chains, hither and thither, as the magnet draws the steel."

Lucian, A portrait study (Greek, Εἰκόνες; Latin, Imagines). In: The works of Lucian of Samosata, Volume 3 (of 4), translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler. At Project Gutenberg. |

|

|

| |

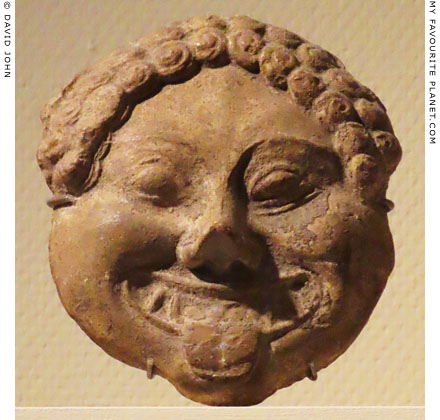

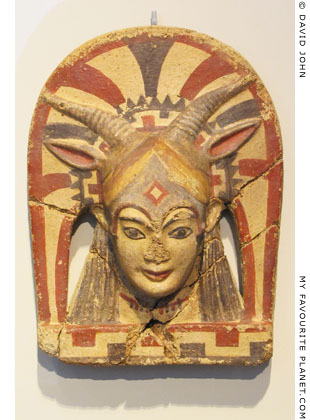

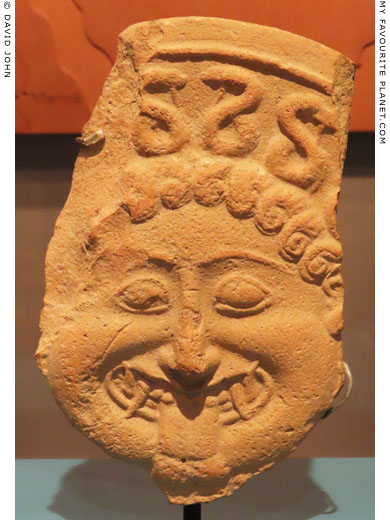

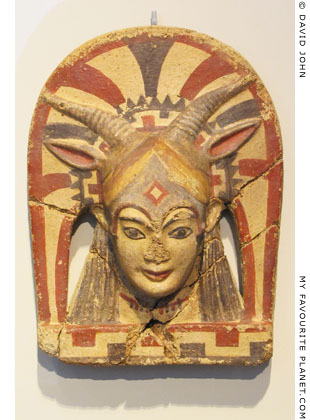

An Archaic painted terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type".

6th century BC. Found in the Archaic level, near the foundations of the later Eastern

Stoa of the Agora, Eretria, Euboea, central Greece, during excavations by the Swiss

School of Archaeology in Greece, 1979-1980.

The antefix is intact, including the covering tile at the rear, and in very good condition,

with fresh-looking colour. As far as I am aware, this is the only Archaic Gorgoneion

antefix on Euboea, and the only one I know of in this part of central Greece. Despite

its age, condition and rarity, it seems it has not so far attracted much attention from

scholars. A very fragmentary 5th century BC Gorgoneion antefix is kept in the

Chaironea Archaeological Museum, Boeotia (Inv. No. 412), but it has no certain

provenance and no information or photos of it have ever been published. [5]

This antefix decorated an unknown building which may have been destroyed

when the invading army of Persian King Darius I sacked Eretria in 490 BC

(see History of Stageira & Olympiada part 4).

Eretria Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Painted Gorgoneion antefix from the Sanctuary of Chthonic Deities,

Akragas (Agrigento), Sicily. Around 520 BC.

One of a number of antefixes discovered during

excavations at the sanctuary in 1953-1955.

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum, Sicily. |

| |

Semicircular marble antefix with an incised Gorgoneion, originally decorated with paint.

From the Oikos of the Naxians (House of the Naxians) in the Sanctuary of Apollo, Delos.

Around 575-560 BC. Height 18 cm, width 29 cm.

Delos Archaeological Museum, Greece. Inv. No. A 7682.

One of six similar antefixes from the oikos exhibited

in the Delos museum, Inv. Nos. A 7677 - A 7682.

|

The long building on the southern side of the Sanctuary of Apollo, known as the Oikos (οἶκος, house) of the Naxians, was built of large granite blocks by the people of the Cycladic island Naxos in the late 7th century BC and dedicated to Apollo. Around 575 BC it was reconstructed with white Naxian marble, and it was the first building ever to have an upper part and roof of marble.

The hall, with porches at the west and east ends, was 19.38 metres long and around 10 metres wide, and had eight Ionic columns along the centre of its long axis, supporting the sloped roof of marble tiles. The porch at the west end was supported by two Ionic columns (distyle) in antis, and that on the east end, which was added later, had four prostyle Ionic columns. There was also a doorway halfway along the long north side, outside which stood the 9 metre tall "Colossus of the Naxians", a kouros statue of Apollo, made from a single piece of marble around 600 BC. The 32 ton inscribed base of the statue still stands outside the northwest corner of the oikos, and the two surviving parts of the kouros, the torso and the pelvis, can still be seen near the remains of the building.

The Oikos may have initially served as an early temple of Apollo, and is thought to been used later as a meeting or dining hall. It has been described as a sort of "clubhouse" or "guildhall". It may have also functioned as a treasury for the storage and display of sacred vessels and votive objects.

See also an Archaic statue base and fragment of a kouros statue from Delos in Medusa part 2. |

|

|

| |

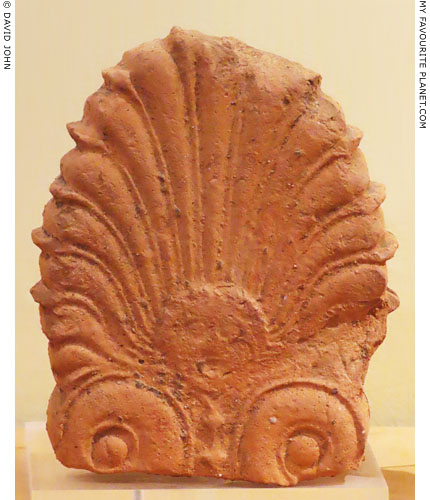

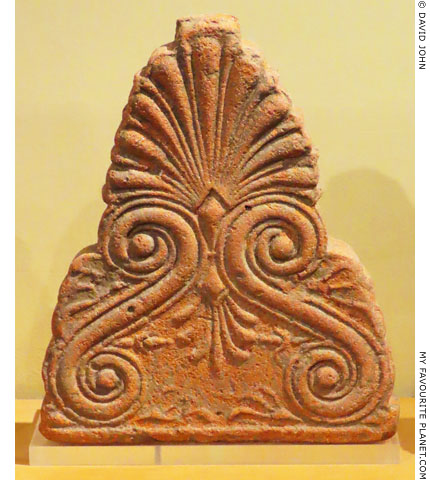

Terracotta antefix with a bearded Gorgoneion "in a seashell". 6th century BC.

Aegean Maritime Museum, Mykonos, Greece.

|

Partially restored, the antefix is in a good condition, and some of the colour has survived. The strongly modelled face of the "horrid type" Gorgoneion is unusual in a number of ways. For example, the centrally parted hair above the forehead is only slightly wavy, The ends of the four braids on either side of the head resemble crabs' claws rather than snakes' heads, and the prominent nose and cheeks are unwrinkled. The sixteen petal-shaped lobes radiating from around the head, painted alternately red and blue, have been interpreted as representing a seashell.

The inside of the shell is separated from the Gorgon's head by an arched frame. Either side of the head, two flat, red-painted bands, representing snaky locks of hair, descend from behind the frontal ears and curl outwards around the lower ends of the frame (or round objects) to form circles.

The countours of the eyebrows and eyes are confidently painted with fine lines and the pupils are concentric circles of red, white and blue, similar to bullseyes. The surviving left ear is painted blue, and the round earring has six red dots around a larger central red dot. The open mouth has finely modelled lips, an even row of top teeth, upper and lower fangs at the corners, and a red protuding tongue. Below the jaw hangs a wavy "beard" (see Medusa part 2).

The excellent Aegean Maritime Museum in Mykonos town is, as the name indicates, primarily concerned with the history of seafaring - in the wider Mediterranean as well as the Aegean Sea. However, it also contains a small number of ancient artefacts not directly connected with sea travel, except in that they were found in shipwrecks or are examples of goods traded by ship. The label of the Gorgon antefix points out that Gorgoneions were used as apotropaic figureheads on the prows of ships.

The exhibits were collected by George M. Drakopoulos (Γεώργιος Δρακόπουλος), who founded the small private museum in 1983 and opened it to the public in 1985. The labelling is informative, but as with many private collections, little or no information is provided about archaeological context or provenance for the objects.

The website of the Maritime Museum Mykonos: aegean-maritime-museum.gr (in Greek and English)

Mould-made shell-frame antefixes of this type are thought to have been invented and developed in Campania, southern Italy around 550 BC as part of a local boom in the production of architectural terracottas influenced by the work of Greek artists in the nearby colonies of Magna Graecia (see another shell-frame antefix below). A large number have been discovered at ancient Casilinum, an Etruscan city just to the northwest of Capua (ancient Etruscan Capeva), on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain, 25 km northwest of Naples. Several types and variations have been identified. Most are decorated with Gorgoneions, although other male and female heads are also represented. The majority of finds are in the Museo Provinciale Campano, Capua, and many others are now in various museum worldwide [7].

Other examples have also been found in Latium and Etruria, suggesting that either moulds were exported or that Campanian artisans went to work there. It would be interesting to discover whether the antefix in Mykonos is from Italy, and how it ended up on an Aegean island. |

|

|

| |

A shell-frame terracotta antefix with the head of a woman.

Made in Campania, Italy. 5th century BC. Height 36.0 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 3594.

One of several Gorgon antefixes of various types in the collection of

the Allard Pierson Museum, most of which are not usually on display. |

| |

A terracotta antefix with a Gorgoneion surrounded by lotus flowers.

From Campania, Italy. Around 540 BC. Height 39.0 cm.

Displayed in 2020 as part of an exhibtion dedicated to the Egyptian god Bes,

with whom Medusa has often been compared: "The Greek Medusa resembles

Bes because she is sticking out her tongue; she is also often combined with

dangerous snakes." From the exhibition labelling.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. APM 3.592. |

| |

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from the Athens Acropolis.

6th century BC.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

|

One of two polychrome antefixes (Acropolis Museum, Inv. Nos. Acr. 78 and Acr. 79) discovered in 1836 in a deposit of objects beneath the southeast corner of the Parthenon, during excavations 1834-1836 led by the German archaeologist Ludwig Ross with architects Eduard Schaubert and Hans Christian Hansen (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 12). The earth around the findspot was burnt, suggesting destruction by a fire, perhaps that caused by the destruction of buildings on the Acropolis during the Persian invasion in 480 BC. It has thus been suggested that they may be from the Archaic Pre-Parthenon temple (Parthenon 2) or the Archaic Propylon, the monumental gateway to the Acropolis which was replaced by the Classical Propylaia.

In 1888 fragments of another seven antefixes (Inv. Nos. Acr. 80, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87), made from the same mould as the first two, were found at various locations to the east and west of the Parthenon. The style of the nine Gorgoneions has been described as Type IX or Ionic (East Greek) type, "in der ältesten Form geschmückt" (decorated in the oldest form), although it has also been compared to West Greek examples of the 6th century BC from Olympia (Olympia Archaeological Museum) and the metope in Selinunte (540-510 BC, see Medusa part 2). One source suggests a date of around 510-500 BC. |

|

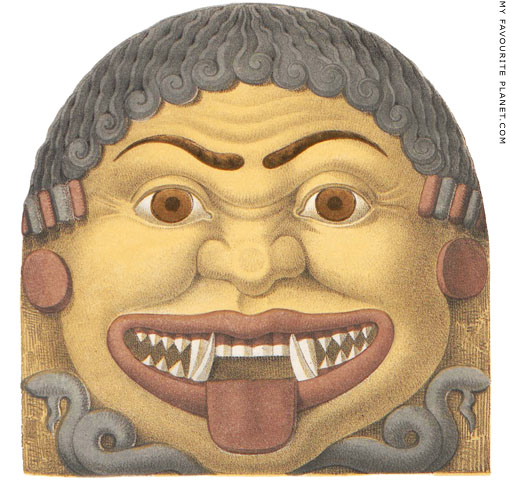

Hansen's drawing of the right side

of the antefix, showing the broken

covering tile behind. |

|

The hair on the top of the head falls in thick wavy bands, ending in a row of thirteen spiral curls above the forehead, and at each side with a row of four long beads, alternately red and black. There are no ears, but large round earrings. The face is broad, with wrinkles on the brow, at the outer edges of the eyes and at the top of the short, flat nose. She has an open grinning mouth with full lips, gums, a row of four regular top teeth, four long fangs in the place of incisors, then rows of pointed top and bottom teeth at the sides, and a potruding tongue. At either side of her chin appears a coiled snake, described as "bearded". The earrings, eyes, lips, tongue and gums are dark red. The hair, eye pupils, eyebrows and snakes are painted black turning to reddish purple. The face and background are pale yellow.

The two best preserved antefixes, Inv. Nos. Acr. 78 and Acr. 79, although broken, are almost complete and still have part of the tile.

Inv. No. Acr. 78. Height 19.5 cm, width 20 cm, length 16 cm.

Inv. No. Acr. 79. Height 21.5 cm, width 20 cm, length 15 cm.

Inv. No. Acr. 85. Only the bottom half of the Gorgnoeion has survived, from just below the eyes, and part of the tile. Height 11.3 cm, width 20.5 cm, depth 12 cm, length of tile at back 7 cm.

The fragments of the other six antefixes are of various shapes and sizes.

A fragment of a larger terracotta Gorgoneion mask (Inv. No. Acr. 88, height 11 cm, width 85 cm), probably an antefix, was also found on the Acropolis. Only an ear and part of the hair have survived, but it appears to have been worked in the round not flat like the others.

Image source: chromolithograph by J. G. Bach of Leipzig, from a drawing by Hans Christian Hansen (1803-1883), in Ludwig Ross (1806-1859), Archäologische Aufsätze, Erste Sammlung: Griechische Gräber; Ausgrabungsberichte aus Athen; Zur Kunstgeschichte und Topographie von Athen und Attika, Tafel 8, Fig. 1; text on pages 105 and 109-110. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1855.

See also:

Stanley Casson, Catalogue of the Acropolis Museum, Volume II, Sculpture and architectural fragments, with a section on the terracottas by Dorothy Lamb Brooke Nicholson, pages 35, 289-290, 322, 426. Cambridge University Press, 1921.

Ernst Heinrich Buschor (1886-1961), Die Tondächer der Akropolis. I. Simen. II. Sternziegel. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin und Leipzig, 1929. |

|

|

| |

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from Ptoon, Boeotia. 6th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 16341. |

| |

A three-quarter view of the Gorgoneion antefix from Ptoon, showing the covering tile behind it. |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

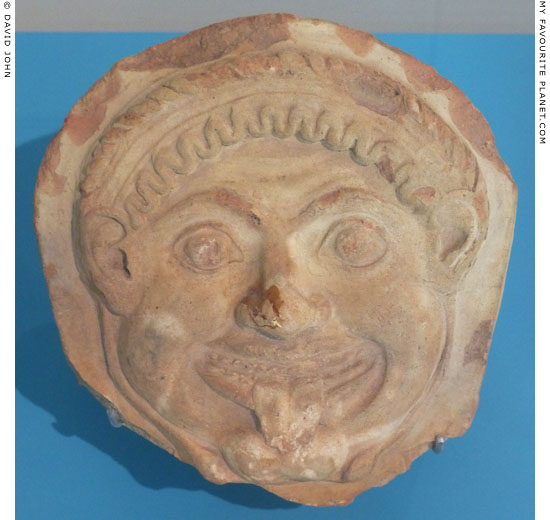

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from the sanctuary on the acropolis

of ancient Oesyme, northern Greece. 550-525 BC.

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia, Greece. |

| |

The ancient Thracian city of Oesyme (Οίσύμη) was located on the North Aegean coast, near the modern settlement of Nea Peramos, just to the west of Kavala (ancient Neapolis), opposite the island of Thasos. It was mentioned by Homer as Aisyme (Αίσύμη), the birthplace of Kastianeira (Καστιάνειρα), "lovely as a goddess", one of the wives of King Priam of Troy (The Iliad, Book 8, lines 253-343).

In the second half of the 7th century BC it became one of the coastal colonies of Thasos and part of the Thasian Peraia. The city's acropolis was on a fortified hill and had an Archaic temple, perhaps dedicated to Athena, which was replaced in the early 5th century BC. Oesyme also had a sanctuary dedicated to the Nymphs. Following the conquest of the city by Philip II of Macedonia around 350 BC, it was renamed Emathia (Ημαθία), after the ancient name for Macedonia and its mythical founder hero.

The features of this round-headed Gorgoneion are in the style favoured around the Aegean and at Athens during the mid 6th to 5th century BC (see, for example, the "Hekatompedon" Gorgon in Medusa part 2, and the coins from Lesbos and Athens in part 1). Although Gorgoneion antefixes have also been found at Naoussa, Langaza, Torone (Polygyros Archaeological Museum, Halkidiki), Thasos (see below), Abdera (see below), Molyvoti (believed to be the site of ancient Stryme) and Mesembria, relatively few Gorgons as architectural decoration from the Archaic or Classical periods have so far been found in the Macedonian and Thracian areas of northern Greece, and it appears that the Gorgon theme generally may not have been so popular here as in other parts of Greece, Italy and Sicily. |

|

Silver stater coin of Neapolis.

510-490 BC.

Obverse: Gorgon's head.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

A fragment of a semi-circular terracotta antefix with a "horrid" Gorgoneion of

the Ionian type from the necropolis of Thasos. 6th century BC. Height 17.5 cm.

|

The German archaeologist Carl Fredrich (1871-1930) visited Thasos during his archaeological tour of the northeastern Aegean April-December 1904, on behalf of the Königliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (Royal Acadamy of Sciences). His reports on Philippi, Imbros and Thasos were published in 1908. The report on Thasos was illustrated by the image above, after a drawing by "Herr Lübke (Berlin)", probably Max Lübke.

Fredrich mentioned that he owned the antefix, which he described as Ionian and of "the old snakeless, bearded type with the wide-open eyes", and compared it to the motif on the early coins of Neapolis (Kavala), "the daughter city of Thasos". "The irises of the eyes and teeth are white, lips, gums and tongue red, the rest is black."

So far I have not discovered what happened to this antefix or its present location. It does not appear to be in the Berlin State Museums. Since Carl Fredrich died in Stettin (since 1945 Szczecin, Poland), perhaps it is there.

Source: G. Fredrich, Thasos, in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 33, pages 215-246, Tafel X. Beck und Barth, Athens, 1908. At the Internet Archive. The volume also includes Fredrich's articles on Philippi and Imbros.

Another similar, more complete antefix from Thasos, dated to the third quarter of the 6th century BC, was in the State Museums Berlin (Inv. No. 94153) until 1945 when it was taken to Russia as war booty along with thousands of artefacts (see also the "Victoria of Calvatone" on the Nike page). It is now exhibited in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Inv. AT 3423 (724). Height 17.7 cm, width 28 cm.

A third antefix of this type is in the Thasos Archaeological Museum, Inv. No. 286π. It was found in the Herakleion, the sanctuary of Herakles, an important cult centre of the ancient city of Thasos. [8] |

|

| |

Fragment of a ceramic sima with a depiction of a running Gorgon. With her right

hand the now headless figure, running to the right, tugs at the fabric of her skirt.

From ancient Abdera, Thrace, northeastern Greece. 6th century BC.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MA 5980.

(Formerly in Kavala Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 657.

At first the running figure was described as a Maenad.)

|

The sparse remains of Ancient Abdera (Άβδηρα) are spread over a large area on the Aegean coast of Western Thrace in northeastern Greece (today part of the decentralized administrative region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace), east of Kavala, around 16 km east of the Nestos River, 22 km south of Xanthi, and northeast of the island of Thasos. It has been suggested that sometime before the 7th century BC it may have been a Phoenician settlement or trading post, like its namesake Abdera on the south coast of Spain. [9]

A Greek myth attributed the name Abdera to the divine hero Abderos (Ἄβδηρος) of Opus in Lokris (central Greece), a son of Hermes (although Pindar wrote that he was a son of Poseidon and Thronia, and Photius claimed he was the brother of Patroklos, companion of Achilles). He was also said to have been the lover (ἐρώμενος, eromenos, loved one) of Herakles and helped him in his Eighth Labour, to capture the four man-eating Mares of Diomedes, king of the Thracian Bistones. Herakles drove the horses into the sea and left Abderos to look after them while he went to fight the Bistones. However, while he was away Abderos was devoured by the horses. After taking revenge by feeding Diomedes to his own mares, Herakles founded the city of Abdera near the tomb of Abderos, where athletic games (ἀγῶνες, agones), consisting of boxing, wrestling and the pankration were held in his honour, while horse races were naturally excluded. [10]

Around 656-652 BC colonists arrived from the Ionian city of Klazomenai (Κλαζομεναί, today Urla, Turkey), 32 km southwest of Smyrna (Σμύρνα; today Izmir, Turkey). According to Herodotus their leader was Timesios (Τιμήσιος), who was later revered as the hero founder (κτίστης, ktistes). However the colony failed to prosper due to attacks by local Thracian tribes. [11] Recent archaeological and pathological investigations have revealed that around 80% of the 7th century BC graves so far discovered were those of infants and young children, many of whom are thought to have died as a result of malaria. The local swampy conditions of the plain on which Abdera stood may thus have contributed to the colony's failure.

A century later, around 545 BC, came settlers from Teos (Τέως, today Sığacık, Turkey), an Ionian neighbour of Klazomenai, fleeing the Persians who had conquered the East Greek city states of Anatolia. It is said that among the refugees was the famous lyric poet Anacreon (Ἀνακρέων, circa 573-495 BC). They appear to have dealt more successfully with the Thracians and their environment, and the town prospered, celebrated in poetry as "Abdera, the beautiful colony of the Teians" (Ἄβδηρα καλὴ Τηίων ἀποικίη). The poem quoted has been ascribed to Anacreon. The Theban poet Pindar (Πίνδαρος, circa 518-438 BC) who praised Abdera, with its "... plentiful vines and bountiful fruits", in his second Paean, apparently commissioned by the city. [12]

Abdera earned well from its agriculture and fishing, and as a port it also profited from the trade between the Thracian hinterland and other Greek cities of the northern and eastern Aegean Sea. As has recently been discovered, it also smelted iron and produced its own pottery. It also produced several poets and philosophers, including Democritus and Protagoras.

After surviving attacks by Thracian tribes as well as invasion by the Persians, Abdera became the most important city in Aegean Thrace, and as an ally of Athens it contributed 15 talents to the First Delian League (see History of Stageira and Olympiada part 5), the third highest tribute. [13] Later, it was subject to the Macedonians then the Romans. Its fortunes waned during the Roman and Byzantine periods, although it survived under the name Polystylon (Πολύστυλον, many columns), corrupted during Ottoman times to Bulustra.

Today the pleasant village Άβδηρα, pronounced Avdira in modern Greek, is 6 kilometres inland from the sprawling archaeological site of the ancient city. In 1950 the first excavations of Abdera were directed by the Kavala-born archaeologist Dimitris Lazaridis (Δημήτρης Λαζαρίδης, 1917-1985). The finds were kept in the Kavala Archaeological Museum and then the Komotini Archaeological Museum. The Archaeological Museum of Abdera was built in the village in the 1990s and opened its doors to the public in 2000. The exhibition, on two floors, contains local finds dating from the 7th century BC to the 13th century AD. It is one of Greece's finest small museums, and well worth a visit before exploring the site.

See also a gold diadem decorated with a Gorgoneion in Medusa part 7. |

|

| |

|

|

|

The top fragments of two ceramic antefixes, each with

a relief of a Gorgoneion at the base of a palmette.

From ancient Abdera, Thrace, northeastern Greece. 4th century BC (?).

Abdera Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

In line with the modern exhibition design concepts adopted by many museums, exhibits in the Abdera Archaeological Museum are grouped thematically (private life, public life, religion, state organization, children, etc) rather than strictly chronologically, and in some cases diverse artefacts from different periods are displayed together without individual labelling. These two antefixes are displayed among a number of others and are labelled simply: "Antefixes. 5th c. BC - Roman period." An information board states that the Corinthian method of roof tiling was the most usual in Abdera, with flat pan-tiles and ridged cover tiles (see photo below).

Several exhibits have been found and handed in by local people over many years, and in some cases a special printed card with the donor's name has been placed next to the object. This is excellent. It does mean, however, that the archaeological context of an object is often lost.

So far I have found little information about these antefixes or the sima (above), or indeed many details about other archaeological finds from Abdera. Similar antefixes, dated to the 4th century BC, have been found at the archaeological site at nearby Molyvoti (Μολυβωτή), thought to be the location of ancient Stryme (Στρύμη), a colony of Thasos (part of the Thasian Peraia) founded in the 6th century BC. The remains of two large neighbouring buildings there have been excavated: one has been dubbed by archaeologists "the House of Hermes" after a gemstone found there, and the other "the House of the Gorgon" because of the discovery of several terracotta antefixes. These buildings have also been dated to the 4th century BC.

From the few published photos I have found so far, the Gorgon antefixes from Molyvoti appear almost identical to these from Abdera. At Abdera pottery kilns and moulds have been found, proving that ceramics were produced here, even though the quality of most surviving objects is rather poor. Whereas no evidence of pottery production has yet been found at Molyvoti. Could it be that the inhabitants purchased their ceramics from Abdera?

The schema of tall palmettes seems to have been very popular at both Abdera and Molyvoti for architectural elements such as antefixes and akroteria, in terracotta as well as stone. A number of other objects, including similar antefixes without Gorgoneia have been found, all with similar basic designs: a fan of convex leaves separated by darts, the tips of which project beyond the edge of the leaves. At the heart of the palmette is an undecorated rhombus. Below the palmette is are a pair of opposing S-shaped convex volutes. In the case of the antefixes above, the Gorgoneia are placed above the place of the rhomboi, and between the tops of the volutes, which have been broken off at the top scrolls. At least one of the antefixes from Molyvoti is almost complete, though cracked in places. [14] |

|

A more intact antefix from Abdera, in a

similar style but without a Gorgoneion.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MA 2568.

Found by a local person and handed

over to the authorites in 1982. |

|

| |

A Laconian cover tile covers the gap between the sides of two adjoining Corinthian pan-tiles.

From ancient Abdera, Thrace. 5th - 4th century BC.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A Laconian type terracotta Gorgoneion antefix, with some surviving red and purple colour.

End of the 6th century BC. One of several similar fragmentary antefixes

found in the ruins of the Bouleuterion (βουλευτήριον, council chamber),

on the south side of the sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia. Width 31.8 cm.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 3L49.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia. |

| |

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type", with traces of colour.

6th century BC. From the southern sanctuary of Poseidonia (today Paestum).

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy.

|

One of a number of Gorgoneion antefixes found in the southern sanctuary of Poseidonia. They are thought to have decorated smaller temples and thesauri (θησαυροί, plural of thesauros, θησαυρός, treasury, storehouse) built soon after the foundation of the city.

Five of the antefixes are exhibited in the Paestum museum. Each is of a different form and type, and the museum label suggests that they are displayed more-or-less in chronological order (see the other four in the photos below). The depictions of the Gorgon are successively less horrid.

The seaside city Poseidonia (Ποσειδωνία) in Magna Graecia (on the west coast of southern Italy) was founded around 600 BC by Greek colonists from either Sybaris (Σύβαρις, Gulf of Taranto, itself founded by Achaeans and Troezenians in 720 BC; today Sibari, Calabria, Italy) or Troezen (Τροιζήν, Argolid Peninsula, northeastern Peloponnese), or perhaps by Achaeans and Troezenians together. In the late 5th century BC it was conquered and renamed Paiston (Παῖστον) by the Lucanians, an Italic people whose culture is known as Oscan. However, archaeological evidence indicates that both cultures continued to thrive alongside each other. The city became known as Paestum following conquest by the Romans in 273 BC. |

|

A fragment of a similar Gorgoneion

antefix from the sanctuary at Linora,

3 km south of Paestum.

Mid 6th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum. |

|

| |

A modern reproduction of the Gorgoneion antefix above, with restored

colours, displayed in the Paestum museum for educational purposes.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy. |

| |

The second terracotta Gorgoneion antefix in the Paestum museum.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy. |

| |

The third terracotta Gorgoneion antefix in the Paestum museum.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy. |

| |

The fourth terracotta Gorgoneion antefix in the Paestum museum.

This is the only intact antefix, and it is still attached to the tile.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy. |

| |

The fifth terracotta Gorgoneion antefix in the Paestum museum.

This antefix is around twice the size of the other four. The round,

plate-like frame has been restored, but enough of the colour has

survived to give an impression of the antefix's original appearance.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy. |

| |

A drawing of a terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from the Greek colony of Selinous

(Σελινοῦς; today Selinunte), on the southwestern coast of Sicily (see photo below).

One of two examples of the same type found around 1876 in the area of Temple C,

on the acropolis of Selinous. Both are now exhibited in the Palermo museum. Height 18 cm.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily.

|

One of several Gorgon antefixes of various styles (see another below) connected with different phases of construction on the acropolis of Selinous from the foundation of the city (circa 650-628 BC), to around the period of the building of Temple C (circa 540-510 BC). Other antefixes found there depict heads of Silenos and a youthful male.

Read more about Selinous on Demeter and Persephone part 1.

In the late 19th century, when discussing architectural terracottas discovered in Sicily, the archaeologist Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz wrote:

"Of plastic figurative terracottas for architectural use, the most numerous are antefixes. Of these, naturally, the most uptil now come from Selinus. However, I know of others from Lilybaion, Motya, Gela, Kamarina, Syracuse and Naxos. The commonest representation is the Medusa head, which appears in various forms, including the later characterless forms. After these come Silen or Satyr heads and undefinable female heads."

Source: Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz, Die antiken Terracotten, Band II, Die Terracotten von Sicilien, Fig. 83, page 42. W. Spemann, Berlin & Stuttgart, 1884. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

A photo of the Gorgoneion antefix from Selinous in the drawing above.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily. |

| |

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from the area of Temple C, on the acropolis of Selinous.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from Selinous, Sicily. Around 500 BC.

Height 18.2 cm, width 18 cm, depth 10.6 cm.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Inv. No. 1984.521.

Formerly in the collection of Dr. Walter Kropatscheck, Helgoland.

Purchased with funds from the Campe'schen Historischen Kunststiftung. |

| |

Part of a terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from the necropolis of Randazzo,

in the valley of the Alcantara river, Catania province, eastern Sicily.

Among artefacts, dating from the 6th to 3rd centuries BC,

excavated 1889-1890 by Antonino Salinas. The ancient Greek city

to which the necropolis belonged has not yet been identified.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily. |

| |

A painted terracotta Gorgoneion antefix.

6th century BC. From Scalo Ferroviario, Gela.

A remarkable and unusual Gorgon antefix, for its time finely modelled

and coloured. Not quite the "horrid type" (most of the Gorgons from

Gela not are truly horrid), but not yet of the "beautiful type". Next to the

head is some sort of note of authentication with an official wax stamp.

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum, Sicily, Italy.

|

The powerful city of Gela (Γέλα), on the south coast of Sicily, was founded circa 688 BC by Dorian Greek colonists from Rhodes and Crete, around 45 years after the foundation of Syracuse. According to Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 6, chapter 4), around 108 years later (circa 582-580 BC) the Geloans founded Akragas (Ἀκράγας, today Agrigento), further west along the coast. The modern town was founded as Terranova di Sicilia by Emperor Frederick II in 1233 AD, and renamed Gela in 1928.

Antefixes were produced in Gelan workshops from the second half of the 6th century BC until the destruction of the city, either in 287 BC by an army of Italian mercenaries known as the Mamertines (Μαμερτῖνοι, Sons of Mars), or in 282 BC by Phintias (Φιντίας), the tyrant of Akragas. Phintias resettled the surviving Geloans at Phintias (today Licata), the new city he founded and named after himself, on the coast between Gela and Akragas. |

|

| |

A terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type".

2nd half of the 6th century BC. One of two identical antefixes (from the same mould)

discovered at the site of a small temple in the residential area of Monte Bubbonia,

20 km north of Gela. Both have been restored, though this one is better preserved.

The deep crease down the centre of the forehead is also a feature of other

6th century BC Gorgoneions, including on Athenian coins (see Medusa part 1).

The site on Monte Bubbonia may be Maktorion (Μακτώριον), mentioned by

Herodotus (The Histories, Book 7, chapter 153) as "a city above Gela".

It is thought to have been inhabited by Greek and native Sicilian Sicians.

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum, Sicily, Italy. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix.

Greek, around 550-500 BC. Found in the sea off the coast of Gela, Sicily. It is

covered by several "worm casts" of sea creatures. Height 50 cm, width 40 cm.

Soprintendenza per i Beni culturali e ambientali del Mare, Palermo. Inv. No. 4237.

Exhibited in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, during the

exhibition "Sicily and the sea", 16 June - 25 September 2016. |

| |

A fragment of a terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from Sicily.

Around 525-500 BC. From Taranto, Apulia, southern Italy (Greek,

Τάρᾱς, Taras, Magna Graecia; Latin, Tarentum). Height 18 cm.

Displayed in 2020 as part of an exhibtion dedicated

to the Egyptian god Bes (see above):

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. APM 1.103. |

| |

Terracotta antefix depicting Medusa's head with a krobylos hairstyle.

From Gela, Sicily. Around 490 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1899,0718.2 (Terracotta 1137, also Terracotta B 580).

Donated by the collector J. Reddie Anderson in 1899.

|

There are a number of antefixes of this type, known as "gorgone con krobylos", including three in Gela Archaeological Museum; the best preserved is Inv. No. 8411. All show the Gorgon wearing a wide, curved headdress or stephane (crown) above rows of black curls and the elaborate krobylos (κρώβυλος) hairstyle popular during the Archaic period, as well as large round earrings with concentric circles.

One fragment from Gela, on which the paint has been well preserved, shows the strong colours used, including "rouged" cheeks. [15] The face is quite human, although to the modern eye with something of a cartoon or clown character. There are no snakes, wrinkled nose or fangs, in fact the teeth are in perfectly even rows. The faded paint in this example suggest a faraway, distance look in the eyes, although the Gela fragment belies this illusion. However, this is not a glance that would petrify or even scare the viewer.

Like the Gorgonians in the two photos further above, this type can not be accurately described as either "horrid" or "beautiful", and it appears to cross a boundary from the type immediately above into the realm of jolly, comical or even downright silly. Whatever the Sicilian Greeks of the Archaic period thought of Gorgons, or however they considered depictions of them, it is difficult to imagine that they would have viewed such a figure with dread. |

|

| |

An Archaistic (imitating the Archaic style) Gorgoneion antefix, harking back to

the "horrid type". From the acropolis of Gela, Sicily. End of the 4th century BC.

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum, Sicily. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix. 6th - early 5th century BC.

Excavated in the area of the railway station, Syracuse, Sicily.

An unusually well modelled, three-dimensional depiction of Medusa,

with a degree of realism heightened by the bold painting.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse. Inv. No. 84845. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion from a temple building in the east of

the ancient city of Naxos, Sicily. First half of the 5th century BC.

Naxos was the oldest Greek colony in Sicily, founded on the east

side of the island in 734 BC by settlers from Chalcis in Euboea.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse. |

| |

An Archaic Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type". Made and found in Taranto, Apulia,

southern Italy. 550-500 BC. Height 19.2 cm.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam. Inv. No. 1105. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix of the "horrid type" from Rubi (ancient Rhyps or Rhybasteion;

today Ruvo di Puglia, Apulia, southern Italy). Made in Taranto about 490-470 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1875.6-15.1 (Terracotta 1251 bis).

Semi-circular Gorgoneion antefixes, made in a mould and finished with a stick, were produced

at Taranto from the mid 6th to the 3rd century BC. One of the earliest surviving examples,

made around 525-500 BC, is in the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto, Inv. No. 17580. |

| |

Terracotta Gorgoneion antefix from Taranto. Made in Taranto about 450 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1889.8-10.1 (Terracotta 1270). |

| |

Etruscan terracotta Gorgoneion antefix.

520-500 BC. Height 29 cm, width 30 cm.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Inv. No. H III YYYY 38.

|

One of an number of Etruscan architectural terracottas, including four Gorgoneions, displayed in the museum on a very high shelf, and therefore difficult to see for most visitors. The individual exhibits are not labelled, and not all are to be found in the Collections section of the museum's website.

See: Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen, De grieksche, romeinsche en etrurische Monumenten van het Museum van Oudheden te Leyden, II. No. 424, page 101. H. W. Hazenberg en Comp., Leiden, 1848. At the Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

Etruscan terracotta Gorgoneion. Part of an antefix?

Unlabelled. See text for antefix above.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. |

| |

Etruscan terracotta Gorgoneion antefix.

Unlabelled. See text for the antefix above. Height 26 cm, width 17.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Inv. No. RG 16. |

| |

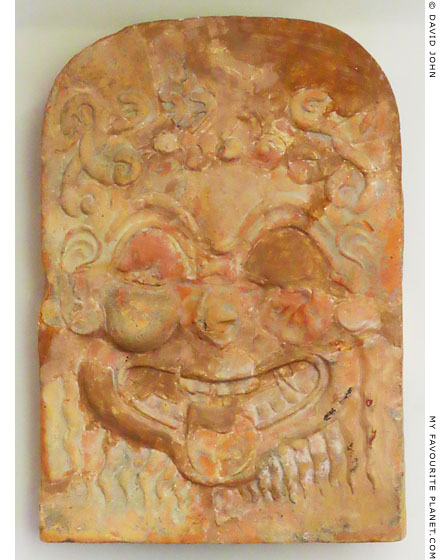

A terracotta Gorgoneion. Part of an antefix? Described by the

museum labelling merely as "mask wth grotesque features".

Found in one of the deposits at the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Rachi,

Isthmia (see Demeter and Persephone part 1). Late 4th - early 3rd century BC.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. IM 967. |

| |

Fragment of a terracotta antefix with a Gorgoneion in a palmette.

Roman Imperial period, 1st century AD. Found in 1936

in Piazza Fontana, Milan (ancient Mediolanum).

An unusual late example of a terracotta antefix with an Archaistic Gorgoneion.

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan. Inv. No. A 0.9.28492. |

| |

| Medusa |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Clay, pottery, ceramics, earthenware and terracotta

In English Ceramic objects are often described as "clay" (in German Ton), but this is technically incorrect. Clay is the raw material, but when it is fired at high temperatures in a kiln, it is transformed chemically and physically into a permanently hard substance. Although baked clay products are generally referred to "pottery", they include a large variety objects which are not pots or vessels, including tiles, antefixes, plaques and statues. The word ceramic, derived from the Greek κέραμος (keramos, pottery or pottery clay), has become the accepted word to describe objects made of fire-hardened clay, as in ceramic art and ceramic artist.

The words earthenware (vessels or other products made of earth) and terracotta (alternatively terra cotta or terra-cotta) are also often used to denote ceramic objects. The Latin term terra cocta means cooked earth, and in Italian terra cotta means baked earth. However, the term has long been used in English to refer to red, reddish or orange-brown earthenware, particularly products such as unglazed red floor tiles, plant pots, etc. (it is also used to describe the type of colour itself.) Many ancient domestic, architedtural and ritual ceramic objects are referred to as terracotta, also when they have been painted. There are many other types of ceramic fabrics, such as porcelain.

2. Protome

A protome (Greek, προτομή, foremost or upper part of something; from the verb προτέμνειν, protemnein, to cut off the front) is a depiction of the head, bust or forepart of an animal, human or fabulous creature, usually a frontal view, in art and architectural decoration, on utensils, coins, etc.

The earliest known use of the word was by the English doctor, clergyman, antiquarian and natural philosopher William Stukeley (1687-1765), who also pioneered the archaeological investigation of Avebury and Stonehenge. The word protome was used - without explanation - in:

William Stukeley, The family memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley, M.D., and the antiquarian and other correspondence of William Stukeley, Roger & Samuel Gale, etc., Volume III, pages 56 and 61 (extracts from diary entries for September 1737 and July 1739). Publications of the Surtees Society, Volume LXXX for the year 1885. Durham, London, Edinburgh, 1887. At the Internet Archive.

William Stukeley, The medallic history of Marcus Aurelius Valerius Carausius, Emperor in Brittain, Book I, pages 29 and 144. Charles Corbet, bookseller, London, 1757. At Google Books.

3. Etruscan ceramic tile roofs

"Roof terracottas from southern Etrutria and Latium

Since the 7th century BC, the Etruscans roofed their buildings with clay tiles like the Greeks. The roof fringes were decorated with colourful, ornamental and figure-shaped terracottas. Antefixes on the cullis were formed in the shape of heads or masks. Clay figures crowned the gables and roof ridges, Caere was one of the centres of this terracotta production."

Exhibit label in the Altes Museum, Berlin.

I have not yet seen an Etruscan antefix from the 7th century BC. The oldest example in the Altes Museum is from the late 6th century (see photos right).

4. "Gorgoneion" antefix from Thessaloniki

See: Janer Danforth Belson, The Gorgoneion in Greek architecture, pages 10-11, catalogue No. G.M. 32. PhD dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1981. At Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College.

5. Eretria antefix

See the report (in German) of the excavations at Eretria, 1979-1980, by the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece:

Clemens Krause, Eretria: Ausgrabungen 1979-1980. In: Antike Kunst, 24. Jahrgang, Doppelnummer (1981), pages 70-87, particularly page 78 and Tafel. 12, 1. Vereinigung der Freunde Antiker Kunst, Basel, Switzerland. PDF available as a PDF document at the website of the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece.

Of the fragmentary Gorgoneion antefix in the Chaironea Archaeological Museum, Boeotia (Inv. No. 412), only the top of the head, left eye and part of the left cheek have been preserved. The piece has no firm provenance, it has never been published, and no photograph has been published. Because it is in the Chaironea museum, it is taken as likely that it is from Boeotia.

See: Janer Danforth Belson, The Gorgoneion in Greek architecture, page 15 and catalogue No. G.M. 6, page 11. PhD dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1981 [see note 4].

6. Beautiful type Gorgoneion antefix from Taranto

The antefix is now in the Collezione Archeologica Paolo Orsi of the Museo Civico di Rovereto, Italy.

See: Ingrid Krauskopf, Gorgo, Gorgones, nu. 108b. In: Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). Band 4, Zürich/München 1988.

Also cited in: Olga A. Zolotnikova, A hideous monster or a beautiful maiden?, fig. 2, page 357, see note in Medusa part 1).

7. Shell-frame antefixes

Professor Birgitta Lindros Wohl reported that in 1995 there were around 59 Gorgon antefixes of a number of sizes and minor variations, some fragmentary, on display in the Museo Provinciale Campano, Capua, with a further unspecified number in storerooms.

See: Birgitta Lindros Wohl, A Campanian Gorgon Antefix, in The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Volume 24/1996, pages 13-20. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, 1997. At jstor.org.

The terracotta shell-frame antefix from Campania now in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, is dated around 550-500 B.C. Preserved height 27.5 cm, width 37 cm. Inv. No. 75.AD.107.

Below is a list of some of the Campanian shell-frame Gorgon antefixes in other museums. All examples are dated around 550-500 BC (some 575-500 BC), are described as Etrusucan and having been found at Casilinum, most with surviving traces of red, black and white colour:

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 21581.

Museo Artistico Industriale, Rome. Inv. Nos. 9 and 26.

British Museum. Inv. Nos. 1877,0802.5 (Terracotta B596) and 1877,0802.4 (Terracotta B597).

Antikensammlung, Berlin State Museums. Inv. No. TC 7154.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Inv. Nos. H 30 and H 30a.

Historisches Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main.

Two are recorded in the Palazzo Chigi, Siena.

Several examples are catalogued in: Herbert Koch, Dachterrakotten aus Campanien mit Ausschluss von Pompei. Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1912.

8. The Gorgon antefixes from Thasos

For further information about the antefix in the Pushkin Museum, see:

Акимова Людмила Ивановна (Akimova Ludmila Ivanovna), 35. АНТЕФИКС С МАСКОЙ ГОРГОНЫ МЕДУЗЫ (Antefix with the mask of the Gorogon Medusa). Part of the online catalogue of the A.S. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, in Russian (250 artefacts from the museum's collection, organized into 12 sections).

Akimova mentions another antefix from Thasos, perhaps Fredrich's fragment illustrated above, which she believes is in the Berlin State Museums: "The closest analogy to the monument is another, somewhat worse preserved antefix, which also originates from Thasos (from the area of the Temple of Hercules and Prytaneus) and now kept in the Antique Collection of Berlin."

Very little has been published on the Gorgon antefixes from Thasos, and I have yet to find a comparison of the three mentioned here. The example in the Thasos museum is mentioned in the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) Volume 4, 1, but the entry is typical of many academic publications in that it unhelpfully terse and the bibliographic references lead the reader to outdated publications which contain little further information about the subject.

"47. Tonantifixe. Thasos, Mus. Vom Herakles-tempel und vom Prytaneion. Fredrich, C., AM 33, 1908, 245 Taf. 10; Daux, G., Guide de Thasos (1968) 103 Abb. 49; Belson II 99-101 EG 26-27. - 3. Viertel 6. Jh. v. Chr. - Typ verwandt 31. Ohrringe, Hauer."

LIMC IV, 1, Eros-Herakles, Gorgo and gorgones, No. 47, page 292. Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Zurich, Munich and Dusseldorf, 1988. At the Internet Archive.

A photo of the antefix in the Thasos museum, taken in the 1960s by the German photographer, art historian and archaeologist Konrad Helbig (1917-1986), can be seen on the website of the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library), along with an equally terse description:

Antefix, Stirnziegel, Bauskulptur, Terrakotta ... at the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek. |

| |

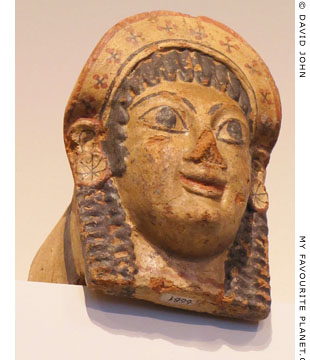

An Etruscan painted terracotta antefix

in the form of a woman's head. Part of

the curved roof tile (kalypter) can be

seen behind the head.

Caeretanian, 530-500 BC. Found during excavations in 1868-1870 at Cerveteri,

Italy (ancient Caere, Etruria).

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 6681. |

| |

An Etruscan terracotta antefix

in the form of a woman's head.

Caeretanian, 530-500 BC. Found during excavations in 1868-1870 at Cerveteri,

Italy (ancient Caere, Etruria).

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

An Etruscan painted terracotta antefix

with a protome of Juno Sospita. Arguably

one of the most beautiful surviving

Etruscan antefixes.

From Latium. 500-480 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. TC 544.

Acquired in 1698 from the Bellori Collection. |

| |

9. Abdera and the Phoenicians

The Phoenician origin and name of Thracian Abdera appear to be speculation, based on the statement of the Greek geographer Strabo that the Abdera (Ἄβδηρα, today Adra, Almería province) on the south coast of Spain was founded by Phoenicians like its neighbour Malaka (Μάλακα, today Malaga) and New Carthage (Καρχηδὼν ἡ νέα, today Cartagena).

"After these comes Abdera, founded likewise by the Phoenicians."

Strabo, Geography, Book 3, chapter 4, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

However, I have yet to find any substantiation of this claim elsewhere. The place on the Iberian Peninsula Strabo called Abdera does indeed appear to have been a Phoenician foundation, but he may have been using a Greek version of the name. There does not appear to be a satisfactory etymology for the Phoenician name, either historical or mythical, perhaps due to the present-day lack of evidence concerning the language. I have heard of no archaeological evidence of Phoenician habitation at Thracian Abdera, although much of the area remains unexcavated.

It has likewise been assumed that Abdera had trading contacts with the Phoenicians, since the city's coinage was said to use Phoenician standards.

10. Abderos, Herakles and the Mares of Diomedes

Varying versions of the myth of the Mares of Diomedes, the Eighth Labour of Herakles, and the involvement of Abderos, were related by a number of ancient authors. Hyginus (Fabulae, chapter 30), wrote that Abderos was a slave of Diomedes, and even gave the horses male names: Podargus, Lampon, Xanthus, and Dinus. See also:

Apollodorus, Library, Book 2, chapter 5, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book 4, chapter 15, sections 3-4. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website.

Philostratus the Elder, "The Burial of Abderus", Imagines, Book II, No. 25. In: Arthur Fairbanks, Philostratus, Imagines and Callistratus, Descriptions, pages 238-241. Loeb Classical Library. William Heinemann Ltd, London; G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1931. At the Internet Archive.

11. Timesios of Klazomenai and the foundation of Abdera

Herodotus, Histories, Book 1, chapter 168

Eusebius places his colony in the 31st Olympiad, around 656-652 BC.

Plutarch mentioned a colony founder named Timesias (Τιμησίας), who is thought to be the same person. It was the custom for potential colonists to consult an oracle (usually taken to have been the Oracle of Pythian Apollo at Delphi) before embarking on their risky enterprise.

"But is impossible for a friend not to share his friend's wrongs or disrepute or disfavour. For a man's enemies at once look with suspicion and hatred upon his friend, and oftentimes his other friends are envious and jealous, and try to get him away. As the oracle given to Timesias about his colony prophesied:

'Soon shall your swarms of honey-bees turn out to be hornets.'

So, in like manner, men who seek for a swarm of friends unwittingly run afoul of hornet's nests of enemies."

Plutarch, On having many friends, section 7. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website.

It has been suggested that the honey-bees turned hornets were the local Thracians, who at first seemed friendly to the colonists but later turned on them.

From Plutarch and Aelian (Κλαύδιος Αἰλιανός, Claudius Aelianus, circa 175-235 AD) we also hear of a ruler called Timesias of Klazomenai (Τιμησίας δ᾽ ὁ Κλαζομένιος or Τιμησίας ὁ Κλαζομένιος), a virtuous man who suddenly decided to leave his city, imagining or realizing that he was hated by the people after he accidentally overheard a schoolboy say, "I'd like to knock the brains out of Timesias."

Plutarch, Praecepta gerendae reipublicae (Precepts of statecraft), section 15. At Perseus Digital Library.

Aelian, Varia Historia, Book 12, chapter 9. At topostext.org.

It is far from certain that this Timesias was the same person as the recipient of the oracle or the Timesios of Herodotus.

12. "Abdera, the beautiful colony of the Teians"

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pindar's second Paean has survived only in fragments. It is thought to have been commissioned by the Abderitans to celebrate their festival of Apollo Derenus and to commemorate a victory in battle against Thracians at a nearby place below Mount Melamphyllon (Ὄρος Μελαμφυλον, Black Leaves; Paean 2, 59-63). The commemoration may have become part of the festival celebrations.

See: Ian Rutherford, Pindar's Paeans: A Reading οf the Fragments with a Survey of the Genre, pages 262-264 and 270-272. Oxford University Press, 2001. At the Internet Archive.

It is not clear from the poem fragments when this battle took place, and although Pliny the Elder also mentioned Melamphyllos as one of the mountains of Thrace, there appear to be no other mentions of such a battle in surviving ancient literature.

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 4, chapter 11, section 50. At Perseus Digital Library.

An information board in Abdera Archaeological Museum displays a chronological "Table of historical events" in Greek and English. Under 545 BC is the following entry:

"Foundation of the colony of the Teians. Clashes with Thracians. Battle of Melamphylo [Μαχι του Μελαμφυλου]. Victory to the Teians."

13. Abdera and Athens

The historian Diodorus Siculus described how the Athenian general Thrasybulus sailed to Abdera to secure its allegiance during the Peloponnesian War against Sparta and its allies (408 BC).

"After this, sailing to Abdera, he brought that city, which at that time was among the most powerful in Thrace, over to the side of the Athenians."

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book 13, chapter 72, section 2. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

For further information about the Delian League and the Peloponnesian War, particularly as it affected northern Greece, see History of Stageira and Olympiada Part 5.

14. Archaeological artefacts from Abdra and Molyvoti

On my most recent visits to archaeological sites and museums in Macedonia and Thrace (2023-2024 including Polygyros, Olynthus, Komotini, Xanthi, Abdera, Kavala, Philppi, Drama) I was dismayed to find that there are no guide books on sale to visitors. The Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports seems to have given up producing the once excellent series of guide books to sites and museums published by its Archaeological Receipts Fund (TAP), although the old editions are still available at those larger sites/museums with shops. Apart from a few publications covering its more prestigious sites such as the Athenian Acropolis, the Ministry seems to have abandoned print altogether. It now seems unlikely that new editions to existing books will appear, or that new volumes will be commissioned. The chances of commercial publishers filling in the market gap are also diminishing, particularly for locations off the main tourist trails. The trend, of course, is increasingly away from print and towards electronic publications, websites and apps. Unfortunately, the official electronic publications remain rudimentary, inadequate and often unreliable.

Fortunately, some archaeologists as well as other scholars and experts kindly make their articles - and sometimes even entire books - freely available online. This is especially welcome to independent researchers, since academic publications are very expensive, and often unavailable to those without access to institutional libraries. Admittedly, some academic articles make for pretty dry reading and are not aimed at the general public, but can offer valuable information, ideas and insights for anyone interested in a particular subject. Recently I have been diving through several such publications dealing specifically with the history of Thrace, and hope to add new information to the articles on this website as time goes by.

Recent excavations at Molyvoti have been organized under the auspices of the Molyvoti, Thrace, Archaeological Project (MTAP), a collaboration between the Ephorate of Antiquities of Rhodope and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). Some of the results of their work have been published online, with hopefully more to follow soon.

In order to present its findings online MTAP has developed a web database, WebDig, on the website of Princeton University. A great idea, but its scope and implementation remain basic, with a very 1990s interface and obscure academic method for displaying queries and results. I am not sure if it is still being maintained or updated.

https://mtap-database.princeton.edu/

Having said all that, I did manage to find the record of one antefix with Gorgoneion of the type also found at Abdera, with a good photo and some basic information:

T024 Artifact - Antefix

Identifier: T024

Category: Terracotta

Locus: Locus L14-069 - Late Roman fill

Source: House of Hermes

https://mtap-database.princeton.edu/app_main.html#

A photo of an identical antefix with Gorgoneion found at Molyvoti (in two fragments, T105, T118) was published in: Αρχαιολογικον Δελτίον, Τόμος 70, 2015 (Archaiologikon Deltion, Archaeological Bulletin, Volume 70, 2015), Fig. 8, page 1168.

15. Gorgoneion with krobylos from Gela

See: Marina Castoldi, Vera da cisterna con Gorgoneia da Gela, Numismatica e antichità classiche (Quaderni Ticinesi), XXXIX, 2010, pages 61-76.

A fragment of a "gorgone con krobylos" antefix from Gela, dated to around 500 BC, with well-preserved colours, is in the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Inv. No. 1984.522.

Height 11.5 cm, width 17 cm, depth 9 cm.

Formerly in the collection of Dr. Walter Kropatscheck, Helgoland. Purchased with funds from the Campe'schen Historischen Kunststiftung. |

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin of Abdera, Thrace.

On the obverse side is a depiction of a seated

Gryphon (Greek, γρύφων), the symbol of the

city, facing left, below the front legs of which

sits a much smaller cricket, facing right.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

| |

Photos on the Medusa pages were taken

during visits to the following museums:

Germany

Berlin, Altes Museum

Berlin, Bode Museum

Berlin, Neues Museum

Dresden, Albertinum, Skulpturensammlung

Dresden, Semperbau, Abgusssammlung

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Münzkabinett

Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

Speyer, Historisches Museum der Pfalz

Greece

Abdera Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Athens, Acropolis Museum

Athens, Epigraphical Museum

Athens, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum

Athens, National Archaeological Museum

Athens, Numismatic Museum

Corfu Archaeological Museum

Corfu, archaeological site of the Temple of Artemis

Corfu, Museum of Mon Repos

Corinth Archaeological Museum

Delos Archaeological Museum

Delphi Archaeological Museum

Dion Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Eleusis Archaeological Museum and site, Attica

Eretria Archaeological Museum, Euboea

Isthmia Archaeological Museum

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Komotini Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Kos Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Marathon Archaeological Museum, Attica

Mycenae Archaeological Site and Museum

Mykonos, Aegean Maritime Museum

Mykonos Archaeological Museum

Nafplion Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia, Museum of the History of the Olympic Games in Antiquity

Patras Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Philippi Archaeological Museum

Piraeus Archaeological Museum, Attica

Polygyros Archaeological Museum

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum, Elis

Rhodes Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Rhodes, Palace of the Grand Master

Thasos Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Thebes Archaeological Museum, Boeotia

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Veria Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Italy

Milan, Civic Archaeological Museum

Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Ostia Archaeological Museum

Paestum, National Archaeological Museum, Campania

Rome, Capitoline Museums, Palazzo dei Conservatori

Rome, National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Baths of Diocletian

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Palazzo Massimo

Rome, Villa Farnesina

Italy - Sicily

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum

Castelvetrano, Museo Civico

Catania, Museo Civico, Castello Ursino

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum

Palermo, Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum

Syracuse, Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum

Netherlands

Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum

Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

Turkey

Bergama (Pergamon) Archaeological Museum

Didyma archaeological site

Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Selçuk

Ephesus archaeological site

Istanbul Archaeological Museums

Istanbul, Basilica Cistern

Izmir Archaeological Museum

Izmir Museum of History and Art

Manisa Archaeological Museum

United Kingdom

London, British Museum

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

Many thanks to the staff of these museums,

especially at Dion, Gela, Manisa and Veria. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |