| |

The head of Medusa with snakes, in the centre of a floor mosaic from Rome. The circular

composition of such mosaics is often likened to a shield, and the patterning, radiating

from the central emblem, has been described as "imbricated", that is with shapes in

contrasting colours appearing to overlap each other, like roof tiles, scales or feathers.

1st - 2nd century AD. Found in the Via Ardeatina, near the church of S. Palombo, Rome.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome.

See also a small emblema with a bust of Dionysus from the same floor mosaic. |

| |

The head of Medusa in the centre of a floor mosaic from Rome.

Roman Imperial period, end of the 1st - mid 2nd century AD.

Found in 1939 in a necropolis on the Via Imperiale, Rome.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 125532. |

| |

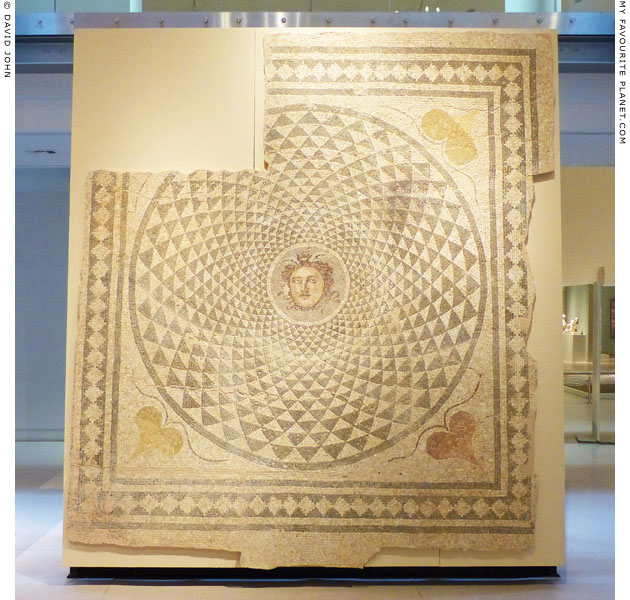

A winged Gorgoneion in the central medallion of a polychrome floor mosaic from the

island of Kos in the Dodecanese. The circular design around Medusa's head is described

as an "imbricated shield" (see above). This is surrounded by a square frame of black

tesserae. At each corner between the shield and this frame is a heart-shaped ivy leaf.

Roman period, Late 3rd - mid 4th century AD.

The Medusa Chamber, Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes.

|

Following the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, Italy took possession of the Dodecanese islands from the Ottoman Turks (see also History of Kastellorizo). On 23 April 1933 the second largest island Kos was devastated by an earthquake which flattened the main town. During the clearing and rebuilding, the level of the ancient city of Kos was discovered and subsequently excavated by Italian archaeologists. [1] The finds among the extensive ruins included several mosaics from the Hellenistic, Roman and early Christian periods, many of fine quality and well preserved, with a wide range of figurative and abstract or geometric designs.

Most of the mosaics can still be seen in Kos, but several where taken to the main island Rhodes. They were set into the floors of the Medieval Palace of the Grand Master of the crusading knights of the Order of Saint John, in the Old Town of Rhodes, which the Italians restored 1937-1940.

Over two the centuries of the knights' rule on Rhodes and neighbouring islands (1309-1522), they constructed several impressive defensive and representative buildings on a grand scale, the palace being the largest and most impressive single example, another being the nearby hospital, built around 1440-1489, now the Archaeological Museum of Rhodes.

While both are imposing edifices, their interiors are quite dark and oppressive, and most of the rooms are dimly lit, not ideal for illuminating the fascinating exhibits. The Medusa Chamber, named after the floor mosaic, is lit by a window with large wooden shutters. When they are open the glare of the sunlight falling in strips, with dark shadows formed by the window frames, makes it impossible to view the mosaic. When they are closed the gloom is too dark to see almost anything at all. [2] |

|

| |

The head of Medusa on a polychrome emblema (panel) of a floor mosaic

in one of the Terrace Houses in Ephesus. Roman period, 3rd century AD.

Terrace House 2 (Hanghaus 2), Dwelling Unit 3, Room 16a.

|

The Gorgon's head is shown in the manner typical of the Roman era, with the tails of two snakes tied in a Herakles knot on her throat. The snake's bodies writhe around the sides of her winged head, and their heads appear above, facing each other. Unusually, they have "horns" and "beards" in the Egyptian manner (see Medusa part 3). Medusa's round face is quite human, feminine and pretty, and she appears to be looking up.

The x-shaped backgound has a pattern of grey scales, probably representing the aegis (see Medusa part 6). The finely executed image has a black oval frame within a thinner black quadrilateral frame, surrounded by a large oblong mosaic area consisting of a black and white recurring pattern of intersecting circles.

The image has been dated stylistically to the 3rd century AD, although some scholars have suggested the 2nd century and even the 5th century (Volker Michael Strocka and Werner Jobst). [3]

In the same room, to the left (west) of this mosaic, is another of the same size and style with an emblema containing a bust of Dionysus.

See also:

a Gorgon relief in the "Temple of Hadrian", Ephesus (Medusa part 3)

a Gorgoneion on the Library of Celsus, Ephesus (Medusa part 3)

Gorgoneions on sarcophagi from Ephesus (Medusa part 5) |

|

| |

| Medusa |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Italian archaeology on Kos

See, for example:

Monica Livadiotti, Giorgio Rocco, Il piano regolatore di Kos del 1934: un progetto di città archeologica. In: Thiasos, rivista di archeologia e architettura antica, 2012, No. 1, pages 3-18. Edizioni Quasar di Severino Tognon, Rome. PDF at thiasos.eu.

2. Light and lighting in museums

This may not be the right place to comment on light and lighting in museums and galleries, but it is an important issue when discussing the exhibition of art of any kind. Having visited hundreds of museums, exhibitions and historical buildings, and having also been involved with exhibition design and organization, it is subject close to my heart. The quality of lighting in an exhibition space has a profound impact on a visitor's experience.

Many museums, particularly those in older older buildings, are dimly or badly lit. Lighting design in such old buildings is a difficult business, particularly where the appearance, material substance and atmosphere of interiors must be preserved. Redesigning and installing new lighting systems can be expensive, complicated and time-consuming: rooms or even entire galleries must be closed during the process.

It is often argued that lighting levels in museums have to be kept low in order to prevent deterioration of the exhibits, particularly pigments. While this may be true, one wonders whether intelligent design and choice of lighting sources could be a better solution than dismal halls. There are also many dingy museum rooms which do not display light-sensitive objects. Some museums and exhibition designers also deliberately darken rooms in order to create a particular "atmosphere" or in an effort to focus the attention of visitors on spotlit exhibits. Unfortunately, this kind of manipulative practice usually has more to do with showbiz than art appreciation.

3. Gorgon mosaic in Terrace House 2, Ephesus

See: David Parrish, Architectural function and decorative programs in the terrace houses in Ephesos, Topoi, volume 7/2, 1997, pages 579-633. At Persée.

An important article on the decoration of the Hanghäuser, with plans, photos and citations of the key studies of the subect. Parrish refers to Terrace House 2, Dwelling Unit 3 (on the plan "Hanghaus 2, Wohnung 3") as House 3. |

|

|

| |

Photos on the Medusa pages were taken

during visits to the following museums:

Germany

Berlin, Altes Museum

Berlin, Bode Museum

Berlin, Neues Museum

Dresden, Albertinum, Skulpturensammlung

Dresden, Semperbau, Abgusssammlung

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Münzkabinett

Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

Speyer, Historisches Museum der Pfalz

Greece

Abdera Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Athens, Acropolis Museum

Athens, Epigraphical Museum

Athens, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum

Athens, National Archaeological Museum

Athens, Numismatic Museum

Corfu Archaeological Museum

Corfu, archaeological site of the Temple of Artemis

Corfu, Museum of Mon Repos

Corinth Archaeological Museum

Delos Archaeological Museum

Delphi Archaeological Museum

Dion Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Eleusis Archaeological Museum and site, Attica

Eretria Archaeological Museum, Euboea

Isthmia Archaeological Museum

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Komotini Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Kos Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Marathon Archaeological Museum, Attica

Mycenae Archaeological Site and Museum

Mykonos, Aegean Maritime Museum

Mykonos Archaeological Museum

Nafplion Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia, Museum of the History of the Olympic Games in Antiquity

Patras Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Philippi Archaeological Museum

Piraeus Archaeological Museum, Attica

Polygyros Archaeological Museum

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum, Elis

Rhodes Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Rhodes, Palace of the Grand Master

Thasos Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Thebes Archaeological Museum, Boeotia

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Veria Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Italy

Milan, Civic Archaeological Museum

Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Ostia Archaeological Museum

Paestum, National Archaeological Museum, Campania

Rome, Capitoline Museums, Palazzo dei Conservatori

Rome, National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Baths of Diocletian

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Palazzo Massimo

Rome, Villa Farnesina

Italy - Sicily

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum

Castelvetrano, Museo Civico

Catania, Museo Civico, Castello Ursino

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum

Palermo, Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum

Syracuse, Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum

Netherlands

Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum

Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

Turkey

Bergama (Pergamon) Archaeological Museum

Didyma archaeological site

Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Selçuk

Ephesus archaeological site

Istanbul Archaeological Museums

Istanbul, Basilica Cistern

Izmir Archaeological Museum

Izmir Museum of History and Art

Manisa Archaeological Museum

United Kingdom

London, British Museum

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

Many thanks to the staff of these museums,

especially at Dion, Gela, Manisa and Veria. |

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |