|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Medusa part 1 |

|

back |

Medusa – part 1 |

|

Page 1 of 8 |

|

|

| |

| The Gorgon Medusa |

| |

|

| |

| Medusa |

Medusa and the Gorgons

in Greek myths |

|

|

|

Medusa (Μέδουσα, Medousa, guardian, protectress), also known as the Gorgon (Γοργώ, γοργών, γοργόνων, the Grim One, grim, fierce, terrible), was one of the three monstrous Gorgon sisters (Γόργονες, the Gorgons).

Several versions of myths concerning the Gorgons were related by ancient Greek authors. The earliest known written accounts were by Homer and Hesiod, probably some time between the 8th - 7th centuries BC. Homer only mentions the terrifying Gorgon's head [1] the Gorgoneion (see below).

Hesiod (Theogony, lines 270-303 [2]) was the first to record what came to be considered the essential myth concerning the Gorgons, including their birth, Medusa having sex with Poseidon and her death at the hands of the Greek hero Perseus (Περσεύς). Hesiod tells us that there were three Gorgon sisters, daughters of the chthonic sea deities Phorkys (Φόρκυς) and Keto (Κητώ): Stheno (Σθεννώ, mighty or forceful), Euryale (Εὐρυάλη, far-springer or far-roaming) and Medusa (the queen, or guardian, protectress), who was mortal.

Another, perhaps more extensive account of the myth of Perseus and the Gorgons was written by the poet Pherecydes, around the first half of the 5th century BC, in the second book of his Genealogies. Only fragments of the account survive in an ancient scholion (commentary) on the Argonautica by Apollonius Rhodius. It was also referred to in the Library of Pseudo Apollodorus. [3]

According to the Roman mythographer Hyginus (see Medusa part 2), the sisters were the daughters of Keto and Gorgon, who was one of the many monstrous children of the Titans Typhon and Echidna:

"From Typhon and Echidna: Gorgon, Cerberus, the dragon which guarded the Golden Fleece at Colchis, Scylla who was woman above but dog-forms below [whom Hercules killed]; Chimaera, Sphinx who was in Boeotia, Hydra serpent which had nine heads which Hercules killed, and the dragon of the Hesperides."

"From Gorgon and Ceto, Sthenno, Eurylae, Medusa"

Hyginus, Fabulae, sections 1-49, Excerpts from the Genealogiae of Hyginus, commonly called the Fabulae Preface. At the Theoi Project. [4]

In the play Ion by Euripides, Gorgon was a monster produced by the Earth goddess Gaia to assist her sons, the Giants, in their battle against the gods (the Gigantomachy), during which he/she/it was killed by Athena [5]. The Gigantomachy is the subject of the frieze around the outside of the Pergamon Great Altar of Zeus. (See Pergamon gallery 2, page 23; see also part of another frieze showing Athena fighting the Giants on Pergamon gallery 2, page 14.)

The original home of the Gorgons is uncertain. Hesiod (Theogony, lines 270-303) described them living near the Hesperides, far to the west of Greece, across the Mediterranean in north Africa. Herodotus, Pausanias and Ovid wrote that they were from Libya, the Greek name for northwest Africa. However, Aeschylus locates them to the east of Greece, on the "Gorgonean plains of Cisthene", and another source relates that they lived on an island called Sarpedon, perhaps one of two places said to have had this name in Thrace and Anatolia (Asia Minor). [6, all references]

Theories have attempted to trace the origins of the Gorgon myths to Greek conquests and colonization, and the assimilation or destruction of indigenous religions. According to such theories, the Gorgon or Gorgons may have been one or more local deities. Other theories have explored the roots of the myths in linguistic, psychoanalytical or sexual terms.

The rapid spread of depictions of the Gorgons from the 7th century BC around the Greek world, including Anatolia, Egypt, Italy and Sicily (see below), coincides with a period in which Greeks were establishing colonies and trading posts around the Mediterranean and as far as the Black Sea (see for example the History of Stageira). Such adventurous undertakings brought them into contact and conflict with hitherto unknown cultures, including those of northwestern Africa.

The Phoenicians, their competitors, established colonies around the western Mediterranean, including Carthage in north Africa, with which the Greeks in the west were to wage wars over the coming centuries. Many Greek myths and legends, including the adventures of heroes such as Herakles, Odysseus, Jason and Perseus, reflect historical incursions into unknown geographical areas; dangerous undertakings which promised either death or wealth and fame for the adventurers.

The myths added epic proportions and supernatural elements: the superhuman heroes had magical weapons and devices lent by their supporting deities, and their enemies became terrible monsters with enormous power. But the heroes often had to use their brains as well as brawn to overcome their foes. These tales must have served as encouragement to the Greeks settling in distant lands and surrounded by enemies, reinforcing their cultural belief that faith in their gods and rulers, courage, steadfastness and intelligence would ensure their survival.

Age-old tales developed over centuries of oral transmission, and new elements were added, often borrowed from traditions of other cultures; further embellishments made the tales more exciting as well as providing back-stories to explain the origins of characters and situations.

Ovid, in Metamorphoses (Book 4), tells us that Medusa was originally beautiful, had shining hair and was desired by many males. Her beauty aroused Poseidon to rape her in a temple of Athena. As retribution for this sacrilege, Athena cursed Medusa, turned her hair into a mass of serpents and made her face so terrible that anyone who looked at it was turned to stone. [7]

With the help of Athena, Hermes, Hades, Hephaistos and the Nymphs, the hero Perseus flew, on wings borrowed from Hermes, to Medusa's home and killed her as she slept (see Medusa part 2). He cut off her head, and the winged horse Pegasus (Πηγασος, Of the Spring) and Chrysaor (Χρυσάωρ, Gold Blade; the hero with the golden sword), her children by Poseidon, sprang from her blood (see photo below and Medusa part 2).

The Gorgon's severed head, known as the Gorgoneion (Greek, Γοργόνειος , Γοργόνειον, Gorgon mask), or the gaze of her eyes alone, could turn those who saw it to stone, and it became a fearsome weapon.

In northwest Africa, Perseus used the Gorgoneion to turn the Titan Atlas to stone (the origin of the Atlas Mountains), then flew to the Aegean island of Seriphos, where he petrified King Polydektes, who had schemed to kill him and marry his mother Danae. [8] He then gave the head to Athena who added it to her armament by attaching it to her aegis (see Medusa part 6).

The threat of the supernatural power of the Gorgoneion, or even an image of it, was believed to provide protection from enemies, and possess apotropaic qualities (i.e. it could ward off evil). It was used as a symbol of several Greek cities, appearing on coins, architectural decoration and sculpture. The presence of an image of the Gorgoneion on a building, grave or other object was meant to scare off potential attackers, thieves and evil spirits. Pausanias wrote that the Athenians placed a gilded head of Medusa on the south wall of the Acropolis:

"On the South Wall, as it is called, of the Acropolis, which faces the theatre [of Dionysos], there is dedicated a gilded head of Medusa the Gorgon, and round it is wrought an aegis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, section 3.

Later he described a curtain in the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, saying that it was dedicated by "Antiochus", probably the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who also gave the Gorgon on the golden aegis above the Theatre of Dionysos as a votive offering:

"In Olympia there is a woollen curtain, adorned with Assyrian weaving and Phoenician purple, which was dedicated by Antiochus, who also gave as offerings the golden aegis with the Gorgon on it above the theatre at Athens."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 12, section 4.

The Gorgoneion may have been large enough to be seen by ships arriving at Piraeus, and have been set up both as a symbol of Athena and a protective talisman. [9]

In February 1395, Νiccοlo da Martoni, a notary from Capua, visited Athens on his return to Italy from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and was shown the two columns of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos, below the south wall of the Acropolis. He was told that between them formerly stood an idol which had the power to sink hostile ships as they appeared on the horizon. This may have been a folk memory of the Gorgon mentioned by Pausanias. [10] |

The head of Gorgon Medusa (Gorgoneion)

on an Athenian tetradrachm coin, around

530-520 BC. A "Wappenmünze" (heraldic

coin), a German term used to describe the

earliest coins of Athens, circa 570-510 BC.

Gorgoneions on this type of coin have

horizontal wavy rows of snake-like hair

(drakones), and a deep crease down the

centre of the forehead, emphasizing her

potruding eyes (see other Gorgoneions

of the same period from Athens in

Medusa part 2 and Sicily in part 4).

Altes Museum, Berlin. |

| |

The head of Gorgon Medusa on

an Athenian silver stater coin

("Wappenmünze"), 530-520 BC.

British Museum.

From the Burgon Collection. |

| |

The head of Gorgon Medusa on a silver

stater of Neapolis, Thrace (today Kavala,

Macedonia, Greece). Circa 510-480 BC.

Diameter 18.4 mm, weight 9.84 grams.

The Gorgoneion motif on coins of Neapolis

and other Greek cities may have been

copied from the Athenian coins.

Münzkabinett, Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

Inv. No. AAB599. |

| |

Another silver stater of Neapolis

(Kavala, Macedonia) with the

Gorgoneion, circa 510-480 BC.

Numismatic Collection,

Bode Museum, Berlin. |

| |

The Gorgoneion on a billon stater coin of

Lesbos (Λέσβος). [11] Circa 510-490 BC.

Diameter 20 mm, weight 14.41 grams.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18203113.

Purchased in 1875 with the coin collection

of Austrian diplomat Graf Anton Prokesch

von Osten (1795-1876). |

| |

The head of Gorgon Medusa above a tuna

fish on a white gold stater from Kyzikos

(Cyzicus, Κύζικος) Mysia, northwestern

Anatolia (today Erdek, Balikesir Province,

Turkey). Circa 500 BC.

British Museum, London. |

| |

| |

A nasty, vicious looking Gorgoneion

on a coin from Cyprus.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

The head of Gorgon Medusa on an electrum

half stater (hemistater) from Anatolia (Asia

Minor), perhaps Ionia. 6th century BC.

Diameter 15mm, weight 7.93 grams.

Numismatic Collection, Bode Museum,

Berlin. Inv. No. 18200105.

From the enormous coin collection of

General Charles Richard Fox (1796-1873),

which was purchased by the museum

following his death in 1873.

One of only two known surviving coins of

this type. The other is in the British Museum.

Weight 8 grams. Inv. No. 1877,0704.2. [12] |

|

| |

The head of Gorgon Medusa on a coin

of Parion (Πάριον), Mysia, northwestern

Anatolia. She appears quite jolly and her

centre-parted hair looks coiffured, but her

head is surrounded by telltale snakes.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

A Gorgoneion on a coin of Parion, Mysia.

From the collection of Heinrich Schliemann.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

| |

The winged head of Gorgon Medusa on

a coin of the Aegean island Seriphos

(Σέριφος), in the Cyclades. With her

"normal" looking face, hair and straight

top teeth, she appears quite human, pretty

even. Her tongue portrudes only slightly.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

The Gorgoneion and aegis on a coin of

Amisos (Ἀμισός; today Samsun, Turkey),

northern Anatolia, on the coast of the

Black Sea. The Gorgoneion is very worn

and now hardly recognizable.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

| |

The Gorgoneion on a large bronze die-struck coin

from Pontic Olbia (Ὀλβία Ποντική), a port at the

north of the Black Sea (modern Ukraine), a colony

of Miletus founded in the 7th century BC.

Circa 450-425 BC. Diameter 65 mm, weight 114.01 grams.

Münzkabinett (Numismatic Collection), State Museums Berlin (SMB).

Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 18202514.

One of 28,000 ancient Greek coins acquired in 1906 from

the collection of the banker Arthur Löbbecke (1850-1932). |

| |

This is one of a number of large Olbian coins of various sizes in the Bode Museum, dated 450-325 BC, with the Gorgoneion on the obverse side. On the reverse is an eagle with outstretched wings, flying to the right (some coins of this type show the eagle flying to the left), carrying a dolphin in its talons, a motif thought to have been copied from coins of Sinope and Istrus on the northwest coast of the Black Sea.

The frontal head of Medusa is more or less the same on all the coins of this type. It may be described as more uncanny than hideous, and on some of the coins even attractive. Around the top edge her hair, parted in the middle, is shown as three rows of wave-like ridges on each side, with three curved ridges per wave. The U-shaped head has a single ridge forming the brows and another the cheeks, jaw and chin, which is a slightly raised oval. The wide-open eyes and straight nose with slightly flaring nostrils are more human than monstrous. Her wide mouth has the usual potruding tongue, and the ridge forming the lips on some coins (such as the one above) is more rounded. Many coins show a straight row of regular top teeth with what appear to be indications of fangs at each end (see photo, right).

The coins are exhibited in the museum with other oversized ancient coins, in a group titled "Schweres Geld" (Heavy money). The museum describes this coin as an "as" (Latin for unit; plural, asses), which was actually a Roman denomination: a small Roman bronze or copper coin, first circulated in Italy from around 451 BC. The Greek word assarion (ἀσσάριον) is believed to have been used later for the as in Greek-influenced provinces of the Roman Empire, for example in southern Italy. Some other sources refer to this Olbian coin type as "aes" (bronze) or "aes grave" (heavy bronze, weighing one Roman pound, around 327.45 grams), which are also Roman terms, while yet other sources avoid the matter altogether and merely call them coins or heavy coins. So far I have not discovered what the Olbians or other Greeks may have called these large coins, their value or for what purposes they were minted.

The large coin in the photo above is also described as being die-struck, while many bronze coins of this type were cast in moulds. [13] |

|

The Gorgoneion on a bronze coin

of Pontic Olbia. Circa 450-400 BC.

Alpha Bank Numsimatic Collection,

Athens, Greece. |

|

| |

A silver denarius of Roman Sicily, on the reverse side (right) of which is shown a Gorgoneion

superimposed on a triskeles, the symbol of the island, and three ears of wheat, apparently

growing between each of the legs. Inscribed around the figure is the legend SICILIA.

Issued by Lucius Clodius Macer, the Roman legate

in Africa, and minted in Carthage in 68 AD.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1867,0101.1606 (not on display).

Purchased in 1867 from French collector Louis, Duc de Blacas d'Aulps.

Photos © The Trustees of the British Museum.

See: britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_1867-0101-1606

|

On the obverse side (left) is a draped bust of the personifcation of Roman Carthage, in profile facing right, wearing a turreted crown. At her shoulder, behind her head, is a cornucopia. Inscription: [L CL]ODI MACRI CARTHAGO S C (senatus consulto).

Lucius Clodius Macer was a Roman legate in the province of Africa during the reign of Emperor Nero (54-68 AD). In May 68 AD he revolted and cut off food supplies to Rome (perhaps explaining the ears of wheat on his coins), but he was assassinated in October of the same year.

The ancient symbol of Sicily is known as the triskelion or trinacria (from the Greek tria, three, and akra, promontory), probably alluding to the triangular shape of the island. It consists of the head of Medusa superimposed on a triskelis, three legs running anti-clockwise. It is sometimes also shown with three ears of wheat, referring to Sicily's fertility and its important role as a supplier of wheat to Greece and later to Rome. Today the symbol can be seen on the island's flag and coat of arms, as well as on many tourist souvenirs. However, ancient examples of the Sicilian triskelion are rare, surviving examples known on a few coins and as decoration on objects, including:

• A triskeles, without Gorgoneion or wheat, in the tondo of an Archaic ceramic bowl from Palma di Montechiaro, 650-600 BC. Height 17.3 cm. One of the oldest examples of the symbol from Sicily. Pietro Griffo Regional Archaeological Museum, Agrigento.

• A Hellenistic period gold coin of Agothokles of Syracuse, the first Sicilian tyrant to proclaim himself king. The design of the coin, minted around 300 BC, is copied from gold staters of King Philip II of Macedon (ruled 359-336 BC, see History of Pella). On the obverse side is the head of Apollo in profile, facing left. On the reverse is a man driving a two-horse chariot to the right, around which is inscribed the name Syracuse, and below is a small triskeles. Diameter 1.5 cm. British Museum, London.

• A brass sestertius coin, minted in Rome in 134-138 AD, showing Emperor Hadrian symbolically raising Sicily from its knees. The island is personified as a kneeling female with the three legs of the triskeles potruding from her head. British Museum, London.

• A black and white floor mosaic emblema (panel), circa 200 AD, in situ in a bath-house in Tindari (ancient Tyndaris, Τυνδαρίς), northeast Sicily, depicting a large round Gorgoneion with the three legs of the triskeles radiating from it, and three ears of wheat sprouting like a beard from below the Gorgon's chin.

See: Dirk Booms and Peter Higgs, Sicily: culture and conquest, pages 29, 119, 141. Published to accompany the exhibition of the same name in the British Museum, 21 April - 14 August 2016. |

|

|

| |

| Medusa |

Medusa, Gorgons and the Gorgoneion

in Greek, Etruscan and Roman art |

|

|

|

A number of prehistoric artefacts showing creatures with monstrous heads are thought by some scholars to represent Gorgons, even small ceramic heads or masks of the Neolithic Sesklo culture (in Thessaly and Macedonia) from around 6000 BC. However, the various theories attempting to associate such objects with the Greek Gorgon myths have yet to be proved.

The figure of the Gorgon Medusa, or just the Gorgoneion, appeared in many types of Greek and Etruscan art from as early as the 7th century BC (Archaic period), particularly on pottery, paintings, architectural decoration, gemstones and coins (see The earliest depictions of the Gorgon myth in Medusa part 2). One of the earliest known depictions of figures clearly identifiable as Gorgons was painted around 660 BC on an amphora known as the "Eleusis Amphora" (Medusa part 2).

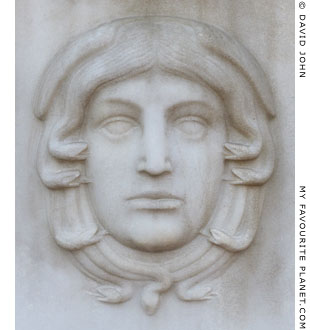

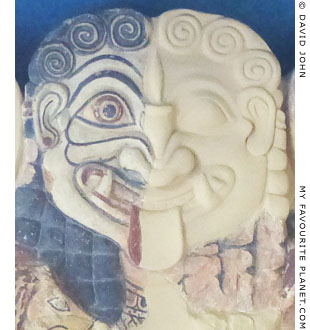

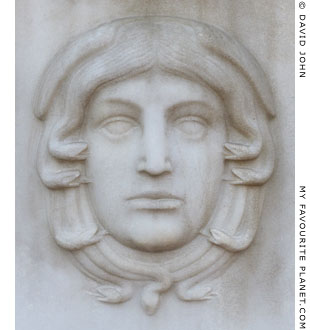

From the 6th century BC the depiction of Medusa's head in the form of a frontal "lion mask" (or "humanoid lion") became standard around the Greek world. The head is usually round, with wavy hair, or topped or surrounded by writhing snakes; the ears are brought forward and stick out frontally; the glaring eyes are large, prominent, sometimes bulging, with thick ridges for eyebrows; the broad nose has a flat ridge, sometimes wrinkled, with a knob at the tip; the cheeks and chin are full and rounded; the wide, grimacing mouth has long fangs in place of upper and lower incisor teeth, and a protruding or "lolling" tongue.

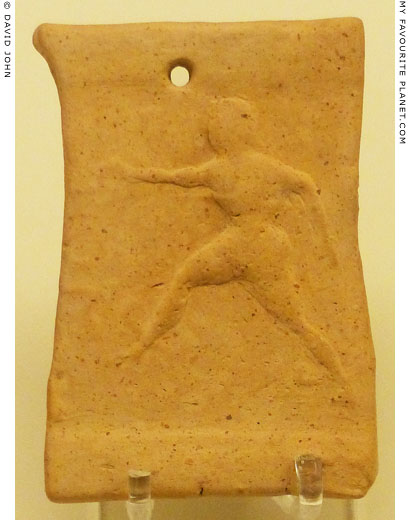

Full figures of Medusa show her winged, wearing a short chiton (tunic), sometimes covered by an animal pelt, and a belt, often of knotted snakes. She is either barefooted or has winged ankles or boots. She is posed in what is often referred to as the "Knielauf" (literally knee-run) schema, a word coined by German archaeologists to describe the kneeling posture favoured by Archaic artists to convey rapid running or flying, for example the Archaic statue of winged Nike from Delos. As with the Nike statue, Medusa's limbs often are arranged in the form of a swastika. The posture is also referred to as the "pinwheel pose".

The Gorgoneion appeared on early Greek coins from at least the second half of the 6th century BC. A rare Athenian didrachm of circa 545-515 BC and several coin types (stater, drachm and trihemiobol) from Neapolis, Thrace (today Kavala, Macedonia, Greece) of circa 510-480 BC show Medusa with a potruding tongue, and later coins minted around the Greek world (for example Athens, Lesbos, Corinth, Korkyra (Corfu) and Cyzicus, see photos above) also bore this motif into Hellenistic times. [14] Although most of the coins with Gorgoneions shown on this page (so far) are from Greece and Greek cities to the east, they were also minted by Greek colonies to the west, such as Himera, Syracuse, Kamarina and Selinous on Sicily. Etruscan cities also issued such coins from the mid 5th century BC, and the Romans were later to put Gorgons on their coins through the Republican and Imperial periods. The last Gorgoneion to appear on a Roman coin was on the shield of a cuirassed portrait bust of the Gallic Emperor Marcus Piavonius Victorinus (reigned around 268-271 AD), just over a century before the prohibition of pagan religion by Emperor Theodosius I in 391 AD.

The Gorgoneion is often shown on representations of Athena (see, for example, "Athena with the cross-banded aegis" on Pergamon gallery 2, page 13). Although the various versions of the myths tell quite different stories, and may be interpretations of local traditions or later inventions, most involve Athena. Apart from the Gorgoneion itself, the strong and ancient association of Athena with snakes is the subject of many myths and images of the goddess. Medusa is often shown wearing a girdle fastened with a knot, as is Athena (for example, the "Altemps" Athena Parthenos statue in the Palazzo Altemps of the National Museum of Rome).

Medusa's appearance later became more common and she remained a popular motif into Roman times, for example on armour, mosaics, column bases, tombs and sarcophagi. However, from the late 6th century BC some depictions of her were already less wild, terrible and ugly and she was gradually transformed from a powerful, dangerous beast - the "horrid type" - to a form more human, attractive, tame, and even benign, typified by "beautiful type" Gorgoneions. [15] Although she mostly appears feminine, many Gorgoneions are androgynous or decidedly masculine. The varieties of representations are illustrated in the photos below.

The famous mosaic from Pompeii of Alexander the Great in battle with the Persian King Darius III shows Alexander wearing a Gorgoneion on the breastplate of his armour (see Medusa part 6). The mosaic is thought to be based on a painting by Philoxenos of Eretria, "Alexander and Darius at the Battle of Issus", of around 315 BC. However, the Gorgoneion in the mosaic and in other artworks of Roman times may be later embellishments. As far as I know, there is no depiction of Alexander made during his lifetime, or of his successors, wearing armour with a Gorgoneion (although, see the "Alexander Aigiochos" type statues).

It is certain that Roman leaders are shown wearing the Gorgoneion on their armour from the time of the first emperors, such as Claudius (see Medusa part 6), and Hadrian seems to have been especially fond of this emblem, as can be seen from many surviving statues of him (see Medusa part 6).

Deified emperors were represented wearing the aegis and Gorgoneion as part of the iconography of imperial religion, which identified them with the ancient mythological deities such as Jupiter/Zeus. According to the Roman author Servius, this breast armour was called aegis when worn by a god, and lorica when worn by a man. [16] |

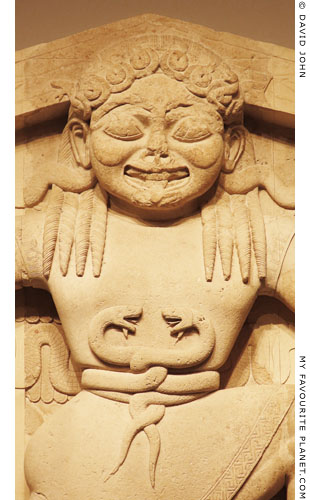

Detail of a terracotta plaque of a Gorgon

in Syracuse, Sicily. Late 7th century BC.

See Medusa part 2. |

| |

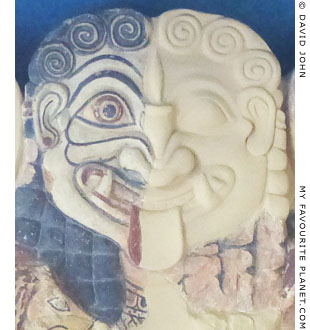

Detail of a terracotta Gorgon figure from

Megara Hyblaea, Sicily. Circa 500 BC.

See Medusa part 2. |

| |

The Gorgoneion on yet another coin

of Neapolis, Thrace (Kavala, Greece).

From the collection of Heinrich Schliemann.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

The Gorgoneion on a coin of

Julius Caesar, 59-44 BC.

Philippi Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The Gorgoneion was a common motif on

richly decorated sarcophagi, particularly

during the Roman Imperial period

(see Medusa part 5).

Manisa Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

| Medusa |

Perseus and Medusa in ancient art |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of an Attic red-figure hydria with a painting of Perseus putting on the winged sandals lent

to him by Hermes before setting off to kill the Gorgon Medusa. He wears a cap in the form of

what appears to be a wolf's head. He is seated with his body facing left, but his head is turned

back to Athena, who stands, wearing a helmet and carrying a shield and spear. On the ground

between them lies the harpe (ἅρπη, a sickle-shaped weapon) with which he will decapitate

Medusa. On the left stands a woman, perhaps his mother Danae, or (anachronistically) his

future wife princess Andromeda (see below).

Around 350 BC. Provenance unknown, but probably from Halkidiki, Macedonia, Greece.

Polygyros Archaeological Museum. From the Lambropoulos Collection. |

| |

Perseus (left) turns away to avoid Gorgon Medusa's deadly gaze as he decapitates

her with a sword. He is watched by Hermes (right), holding a kerykeion (caduceus).

Perseus and Hermes are similarly dressed, and all three figures wear winged boots. Medusa, who like the males wears a short chiton (tunic) and has four wings, stands

frontally in the knielauf position. Two snakes sprout from either side of her head,

and two larger serpents form her girdle. All six snakes are shown with their heads

in profile and have "beards" (see Medusa part 3).

Detail of an Attic black-figure olpe (jug), made in Athens around 550-530 BC. Found

1828/1829 in Vulci, Etruria, Italy, the first vase to be discovered with the signature

of Amasis as potter, Aμασίς μ’ έποίησεν (Amasis m'epoiesen, Amasis made me).

The painting was thus attributed to the Amasis Painter by John Beazley.

Height to top of handle 25.77 cm. Height of body 20.92 cm; diameter 13.25 cm;

diameter of mouth 9.22 cm. Height of figures 10.22 cm.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. 1849,0620.5 (Vase B471). Acquired in 1849.

Previously in the following collections: Lucien Bonaparte; Prince of Canino; W. W. Hope.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

See: britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1849-0620-5

See also: Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 310459 |

| |

Chrysaor and Pegasus are born from the Gorgon Medusa's neck.

Perseus walks away with the kibisis containing Medusa's head.

A low relief on one of the short sides of a limestone sarcophagus,

known as the "Golgoi sarcophagus". 475-450 BC. Discovered by

tomb robbers in November 1873 in the necropolis of Golgoi, Cyprus.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Inv. No. 74.51.2451.

From the Cesnola Collection. Purchased by subscription, 1874-76.

|

The sarcophagus rests on four, large rectangular feet. It is decorated on all four sided with mouldings and low flat reliefs with apparently unrelated figural scenes: on the long sides a banqueting scene and a hunting scene; on the other short side two males riding a two-horse chariot. The surfaces of the gabled lid are plain, but at each corner there is a sculpted recumbent lion with a protruding tongue, facing out towards the short end.

The small figures of Chrysaor (Χρυσάωρ, Gold Blade) and Pegasus (Πηγασος, Of the Spring) emerge from the open neck of the decapitated Medusa. The kneeling Gorgon's body, turned to the left, has four sickle-shaped wings and is dressed in a long belted chiton (tunic) with short sleeves. Her arms are raised to assist the birth of her children. Perseus ignores the birth and walks away to the right with Medusa's head in the kibisis (κίβισις), the pouch he has been given by the Nymphs, which hangs behind him from a staff he carries over his left shoulder. Six incised vertical lines project from above the staff. In his right hand he carries a harpe. The bearded hero wears a conical cap and a short belted chiton, and like Medusa, he is barefooted. A dog sitting in the centre of the scene watches Perseus' departure.

Height of sarcoghagus 96.5 cm, length 202 cm,

width 73.2 cm.

Height of lid 34.3 cm, length 207 cm, width 74 cm. Height of feet 12.7 cm.

Image Source: public domain photo at

metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/242004

See also:

Antoine Hermary and Joan R. Mertens, The Cesnola Collection of Cypriot art - Stone sculpture, Cat. 491: The "Golgoi sarcophagus", pages 363-370. Free downloadable PDF catalogue. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2014. Excellent photos, descriptions and commentaries on a wide range of beautiful ancient sculptures and stone objects from Cyprus.

The catalogue also includes a fragmentary limestone statuette of the triple-bodied monster Geryon, one of the foes of Herakles, holding three shields. The shield on the left (to the viewer) has a lively low relief depicting Athena on the left, and Perseus in the centre about to kill Medusa on the right. Around 550-500 BC. From the sanctuary of Golgoi-Ayios Photios. Inv. No. 74.51.2591, Cat. No. 340, pages 252-253.

Patrick Schollmeyer, Der Sarkophag aus Golgoi: Zur Grabrepräsentation eines zyprischen Stadtkönigs. In Dynastensarkophage mit szenischen Reliefs aus Byblos und Zypern, Volume 2, pages 189-233. Mainz am Rhein, 2007. |

|

The end of the "Golgoi sarcophagus"

with the Perseus and Medusa relief.

See more images of Perseus and

Medusa in ancient Greek art

in Medusa part 2.

See also Gorgons on sarchophagi

and other Roman period funerary

monuments in Medusa part 5. |

|

| |

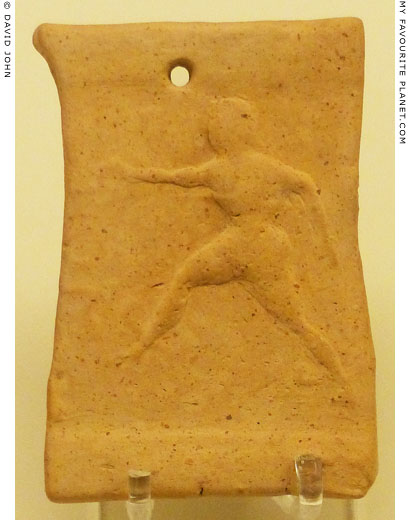

A terracotta plaque with a relief of Perseus, with sickle-

shaped wings on his ankles, running/flying to the left.

6th century BC. From the "Agamemnoneion",

Mycenae (see Homer part 2).

Mycenae Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MM 1208. |

| |

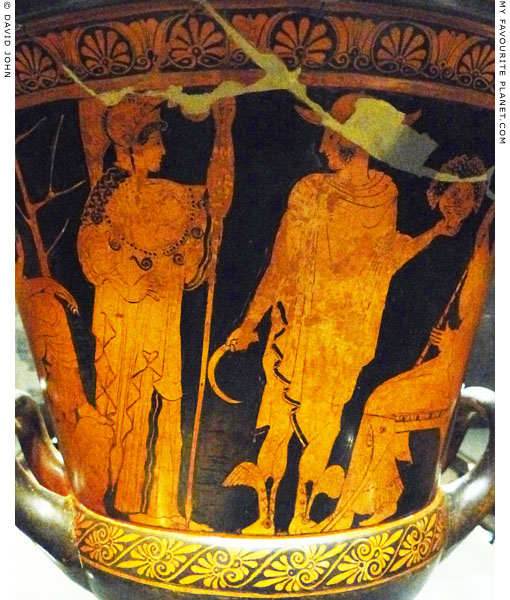

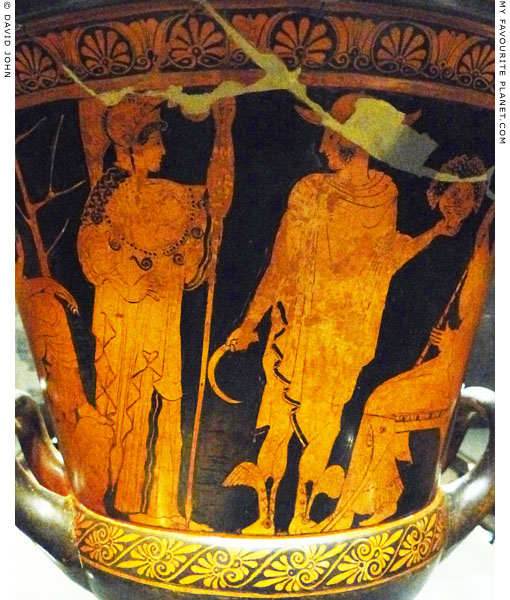

Athena stands next to Perseus who holds the head of Medusa in

his left hand. In his right hand is a harpe (ἅρπη, a sickle-shaped

weapon) with which he decapitated the Gorgon. [17]

Detail of an Attic red-figure calyx-krater, made in Athens about 460-450 BC.

From Kamarina (Καμάρινα), south coast of Sicily (Ragusa province).

Attributed to the Mykonos Painter. Height of krater 53 cm.

Museo Civico, Castello Ursino, Catania, Sicily.

Inv. No. 4399. From the Biscari Collection.

See: Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 205773.

|

Perseus wears a petasos (broad-brimmed hat), a himation (cloak) and winged boots. To the left Athena, her hair in long, thick locks, holds a spear and wears a crested Attic helmet and the aegis over a long chiton. On the far left a draped female figure (Danae or a nymph?) sits on a rock. On the right a male figure with a crown and sceptre (Polydektes?) sits on a chair. This appears to be the scene in which Polydektes is turned to stone by the Gorgoneion on Seriphos. The head of Medusa appears to have Negroid characteristics, perhaps alluding to versions of the myth in which she was from north Africa [see note 6].

The other side (Side B) shows a woman (Andromeda?), a draped male figure leaning on a staff, Poseidon and running Gorgons.

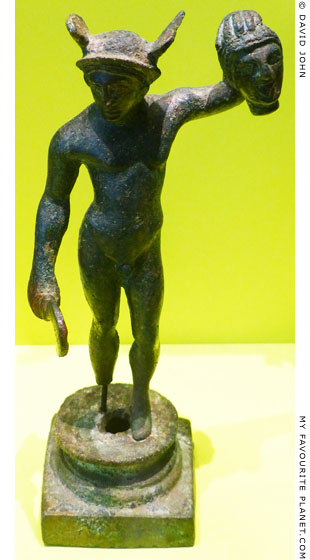

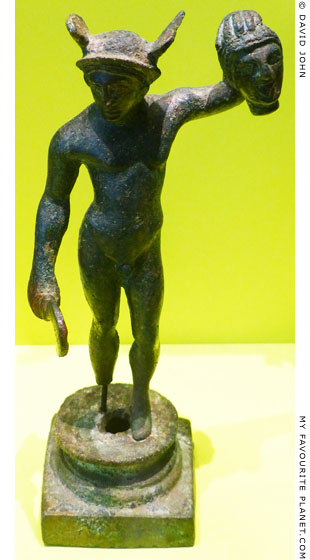

See also an Etruscan statuette of Perseus holding Medusa's head and a sickle below. |

|

|

| |

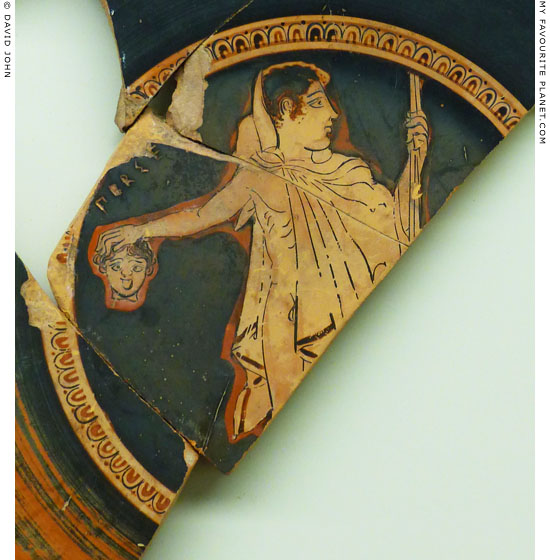

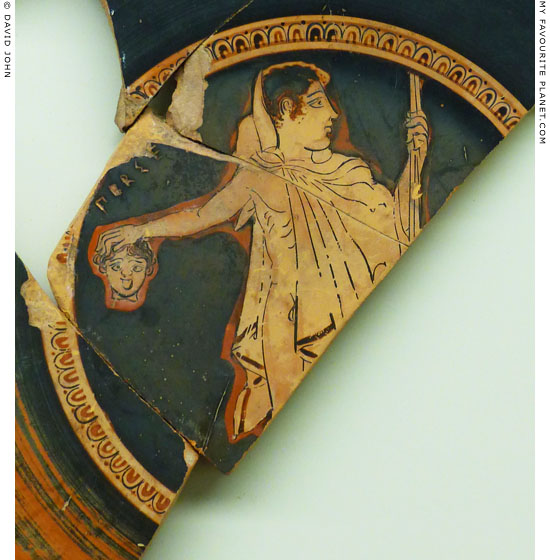

Fragments of a plate with a red-figure painting of

Perseus holding the head of Medusa in the tondo.

Second half of the 5th century BC. Found in Pheidias' workshop

in the sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia, Greece. Diameter 22.6 cm.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. K 3891.

|

Perseus, naked apart from a petasos (πέτασος, a broad-brimmed hat) hanging behind his shoulders and a short cloak, stands frontally with his head turned to the right to avoid the deadly gaze of Medusa, whose severed head he holds in his outstretched right hand. Above it is inscribed ΠΕΡΣΕ, part of the name Perseus. In his left hand he holds what appear to be two spears. Medusa's hair, like that of Perseus, is brown with black contours. She is shown cross-eyed with her tongue hanging out, but appears quite harmless, more like a character from a 1960s American comic strip than a petrifying monster. The background of the tondo is black, with a thick red outline around the figure.

The three fragments of the plate were discovered by archaeologists in the building identified as the workshop where the Athenian sculptor Pheidias made the sculptures for the Temple of Zeus, including the colossal chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of the god. |

|

|

| |

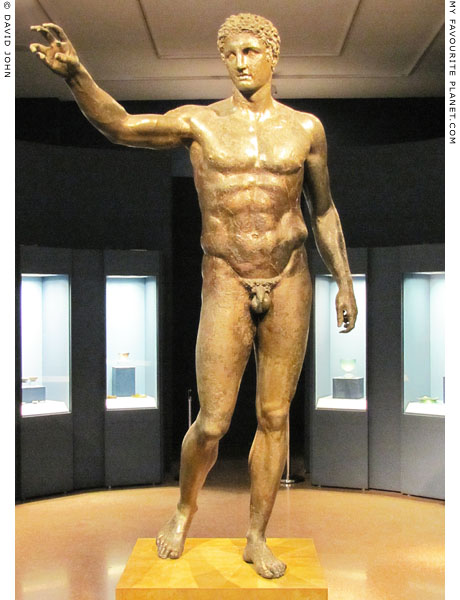

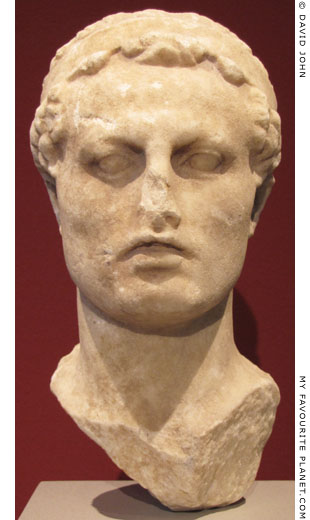

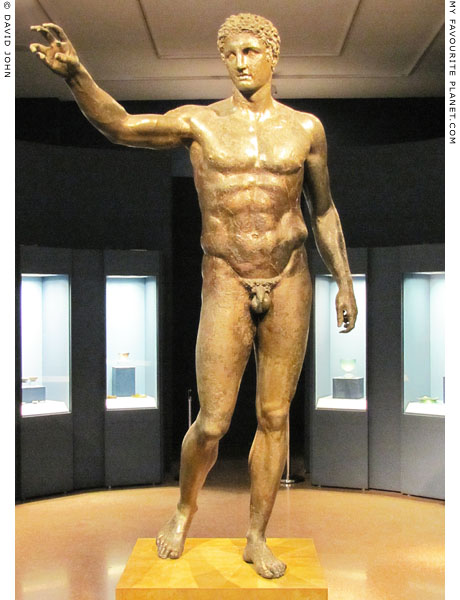

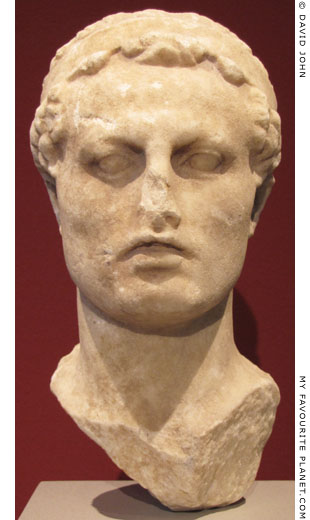

The "Antikythera Youth", also known as the "Antikythera Ephebe"

(Έφηβος των Αντικυθήρων), a bronze statue of a god or hero.

Perseus holding the head of Medusa in his raised right hand

or Paris holding the Golden Apple of Discord are among

the many suggested identifications.

Around 340-330 BC. Probably made in a Peloponnesian workshop.

Euphranor of Corinth is among those suggested as the sculptor.

Found in 1900 by sponge divers in the area of the ancient

Antikythera shipwreck, off the island of Antikythera (Ἀντικύθηρα),

Greece. [18] It has since been restored twice. Height 194 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. X 13396. |

| |

Etruscan bronze statuette of Perseus,

wearing a winged helmet, holding the

head of Medusa in his raised left hand,

and a harpe (a sickel-shaped weapon)

in his lowered right hand.

1st half of the 4th century BC. Height

of figure 13.3 cm. Total height 18.2 cm,

width 7.7 cm, depth 5.6 cm.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg.

Inv. No. 1929.22. From the collection of

Dr. Philipp Lederer, Berlin. Previously

in the Forman Collection, London. |

|

A Roman period coin of Argos showing

Perseus holding the winged head of

Medusa in his right hand, and a harpe in the

left hand, which rests on a standing shield.

This type of coin was issued with little

variation from the reign of Emperor Hadrian

(117-138 AD) to that of Septimius Severus

(193-211 AD). The figure is thought to

represent a statue, perhaps in the hero

shrine (ἡρῷον, heroon) for Perseus in

Argos, mentioned by Pausanias (Description

of Greece, Book 2, chapter 18, section 1).

Source: J. G. Frazer, Pausanias's Description

of Greece, Volume 3 (of 6), Fig. 31, page 186.

Macmillan and Co., London, 1898.

See also: Friedrich Imhoof-Blumer and

Percy Gardner, A numismatic commentary

on Pausanias, page 35, and plate I, xvii

and xviii. Reprinted from The Journal of

Hellenic Studies, 1885, 1886, 1887.

Richard Clay and Sons, London and Bungay,

1887. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

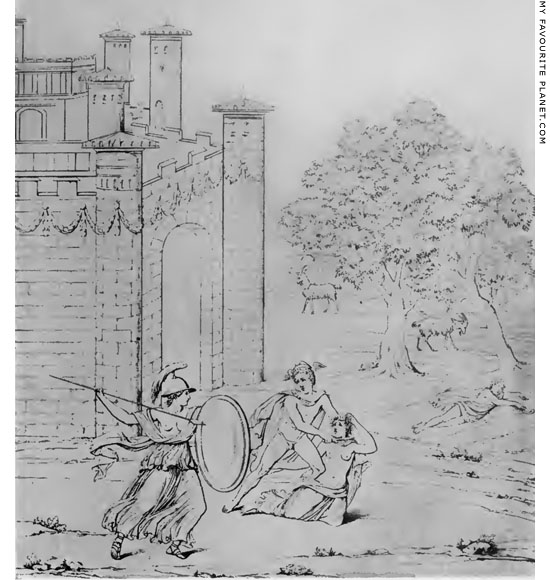

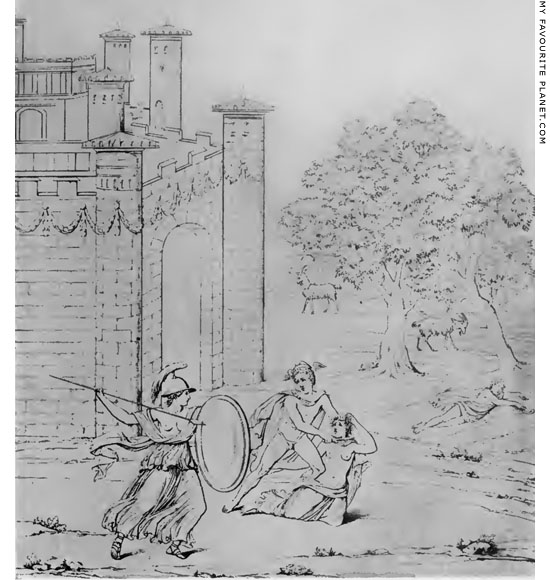

A drawing of a fresco from Herculaneum, depicting Perseus killing Medusa.

Found in 1828 in the tablinum of the House of Aristides, Insula II, 1, Herculaneum.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

|

Perseus stands over Medusa, who he has brought to her knees, leaning his weight on his left foot which rests on the top of her right thigh. She is stripped to the waist, and with her left hand tries desperately to free the grip Perseus has on her hair. He has a small wing on either side of his head, and is naked apart from a cloak over his shoulders. He looks at his reflection in th mirror held by Athena in order to avoid Medusa's gaze, and is about to cut the Gorgon's throat.

The scene takes place in a rural setting in front of the arched gateway of a castle, on the left. On the right two goats graze below two trees, in front of which lies a male figure, presumably a sleeping goatherd.

Image source: Ethel Ross Barker, Buried Herculaneum, drawing after Wilhelm Zahn (see note on the Alexander the Great page), Fig. 55, page 166. Adam & Charles Black, London, 1908. At the Internet Archive. The image was previously (first?) published in a book of prints from drawings of exhibits in the Real Museo Borbonico, Naples, 1824. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

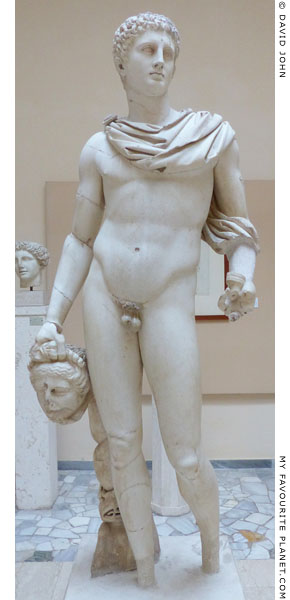

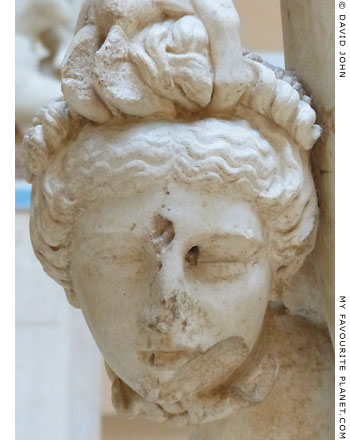

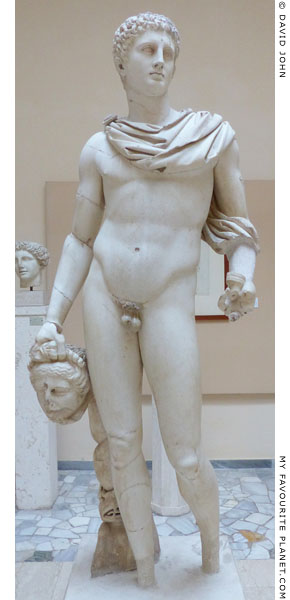

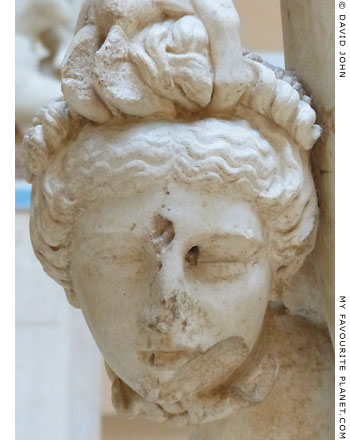

Marble statue of Perseus holding the head of Medusa.

Original creation of the Flavian-Trajanic period, late 1st

or early 2nd century AD. Found in "the Villa of Perseus",

near the baths at Porta Laurentina, south of Ostia.

Ostia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 99. |

|

| |

A marble Neo-Attic relief of Perseus rescuing the Ethiopia princess Andromeda from

the sea monster Ketos. Behind his back the hero hides the head of Medusa. [19]

Luna marble. First half of the 1st century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6686. Farnese Collection.

|

Hyginus on the story of Perseus and Andromeda:

"Cassiope claimed that her daughter Andromeda's beauty excelled the Nereids'. Because of this, Neptune [Poseidon] demanded that Andromeda, Cepheus' daughter, be offered to a sea-monster. When she was offered, Perseus, flying on Mercury's winged sandals, is said to have come there and freed her from danger.

When he wanted to marry her, Cepheus, her father, along with Agenor, her betrothed, planned to kill him. Perseus, discovering the plot, showed them the head of the Gorgon, and all were changed from human form into stone.

Perseus with Andromeda returned to his country. When Polydectes saw that Perseus was so courageous, he feared him and tried to kill him be treachery, but when Perseus discovered this he showed him the Gorgon's head, and he was changed from human form into stone."

Hyginus, Fabulae, section 64, Andromeda. At the Theoi Project.

For further information about Hyginus, see the note in Homer part 2.

See also Hyginus' summary of the story of Perseus and Medusa in Medusa part 2. |

|

|

| |

A plaster cast of the "Medusa Rondanini", a marble

winged head of Medusa of the beautiful type.

Late Hellenistic or Augustan. Height 38.8 cm.

Abguss-Sammlung, Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. ASN 2935. From the

Cast Collection of Anton Raphael Mengs (see the Niobe page for further details).

|

The original, made of Parian marble, is in the Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. 252.

The "Medusa Rondanini" is named after the Palazzo Rondanini, in the Via del Corso, Rome, where it was formerly exhibited. Parts of the snakes and hair and the tip of the nose have been restored. The slightly larger than lifesize marble head first came to the attention of northern European scholars due the praise it received from Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832), who was deeply impressed by it on his visit to the palazzo in December 1786. He acquired a cast of the head but had to leave it in Italy when he returned home.

The head was used by the sculptor Antonio Canova as a model for his marble statue of Perseus with the head of Medusa (1798-1801), made to replace the ancient Apollo Belvedere statue in the Pio Clementino Museum of the Vatican Museums, which had been confiscated by Napoleon's troops.

It was purchased in 1811 (according to another source, in 1814) by Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria (from 1825 King Ludwig I of Bavaria), who had it sent to Munich. In 1826 he gave a new cast of the head to Goethe.

For many years it was widely accepted that the head was a copy of the Gorgoneion on the shield of the Athena Parthenos statue by Pheidias (late 5th century BC), which stood in the Parthenon (Medusa part 6). There appears to have been no evidence to support this theory which has since been rejected. It is now thought that the work was made either in the late Hellenistic period or around the time of the reign of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD).

See also the Medusa head from Aphrodisias in Medusa part 3. |

|

|

| |

Marble bust of Medusa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680),

4th-5th decade of the 17th century AD.

Perhaps made during the early years of the papacy of Innocent X, between 1644 and 1648,

when Bernini was out of favour at the papal court. The myth concerning Athena and Medusa,

as related by Ovid, was retold in verse by Giovan Battista Marino. In Marino's version,

Medusa accidentally sees her own petrifying reflection and is herself turned to stone.

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

An inscribed crowning stone of poros (limestone) from the Perseia (Περσεία), the sanctuary

and fountain of Perseus at Mycenae (Μυκήναι) (see photo below). The ancient city, said to

have been founded by the hero, was destroyed by Argos around 468 BC, but rebuilt in the

Hellenistic period when a fountain house was constructed. [20]

Cuttings in the top and a hole through the circular stone suggest that it may have been

the base for a basin. Around the side is inscribed the final clause of a sacred law, stating

that the hieromnemones (sacred recorders) of the sanctuary of Perseus should also

perform the duties of judges in the case of absence of a demiurge (special judge).

Around 525 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 218. Inscription IG IV 493. |

| |

The site of the Perseia (Περσεία), the sanctuary and fountain of Perseus, next to the entrance

of the Mycenae Archaeological Site, as viewed from the citadel. Among the scanty remains

of the fountain house are deep holes which served as cisterns (see photo below). |

| |

The cisterns of the Perseia at Mycenae from the south, with the citadel in the background. |

| |

Perseus beheading Medusa in a fresco painted in 1512 by Baldassare Peruzzi

on the ceiling of the Loggia of Galatea, Villa Farnesina, Trastevere, Rome.

|

The Sienese painter and architect Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi (1481-1536) designed the villa now known as the Villa Farnesina for the wealthy Sienese merchant Agostino Chigi (1466-1520). The High Renaissance palace, built 1506-1511 on the right bank of the Tiber in the Roman suburb of Trastevere, was decorated inside and out with numerous frescoes by the most prominent painters of the period in Rome. Each fresco depicted a scene from classical history or a mythological tale which also alluded to the life of Chigi himself. The frescoes on the external walls have not survived. For further information about Chigi and the villa, see Aetion.

The garden loggia (loggia del giardino) on the east side of the house was originally open along one side, with a row of archways leading onto the riverside garden. This arcade became known as the Loggia of Galatea after the Triumph of Galatea fresco painted on one of the walls by Raphael in 1511-1512. In 1650 a later owner, Cardinal Girolamo Farnese, closed the archways and fitted them with windows, turning the loggia into a hall.

The long vaulted ceiling of the loggia was designed as a series of alternating curved triangular and hexagonal panels arranged around a centre strip, along which is a row three octagonal panels, one of them a regular octagon between two much longer panels. For 22 of these panels Peruzzi designed frescoes illustrating Agostino Chigi's horoscope, showing the positions of the stars at the exact time of his birth, 9:30 pm, 29 November 1466. Each panel shows one or more astrological constellations along with a scene from a Greek myth associated with them, so that here too the literary and artistic references reflect on Chigi's life. The central ceiling panel originally contained a painting of Chigi's coat of arms, although the arms now displayed are those of a 19th century resident of the villa, the Spanish poet, historian, politician and diplomat Salvador Bermúdez de Castro y Díez (1817-1883).

The photo above shows the left-most of the two long octagonal panels. On the left Perseus, in military garb and with wings on his helmet and ankles, is about to decapitate the kneeling Medusa, whose snaky hair he grasps with his left hand. At his side his mirrored shield hangs from a thread around his right shoulder. Strangely, he is shown facing Medusa. Below, the scene is observed by a row of five white male figures appearing from behind billowing purple clouds. They are said to represent characters turned to stone by Medusa's gaze, although the figure second from left resembles Pan. To the right of these is the head of Pegasus, one of Medusa's children. On the right side of the panel the winged figure of Pheme (Φήμη, Fame; Latin, Fama), the personification of Fame and Renown (and Rumour), trumpets the fame of Perseus' deed.

Depicted on the other long ceiling panel, to the right, are the stars of the constellation Ursa Major (Great Bear) and the nymph Callisto (Καλλιστώ, Kallisto) driving a golden chariot pulled by two bulls. Callisto was turned into a bear by either Zeus or his wife Hera (there are differing version of the myth), before Zeus eventually transformed her into the group of stars and her son Arktos (Αρκτος, Bear) into the neighbouring Ursa Minor. |

|

| |

Modern bronze sculpture (19th century?) of Perseus riding triumphantly in a chariot

pulled by two winged horses and brandishing the head of the Gorgon Medusa.

The sculpture can sometimes be seen parked on a trailer in various streets of Berlin,

Germany, with a for sale sign. Apparently it is an antique dealer's advertising gimmick.

Photos © David John 2008 |

| |

Perseus raises Medusa's head threateningly. The Gorgon looks a little green. |

| |

The head of a demonic monster above the entrance to a ghost train

(Geisterhölle, ghost cave) at a visiting funfare in Speyer, Germany.

The monster's head has been given horns, a moustache and goatee beard to identify him as

the Devil, in the way the "Prince of Darkness" has been represented in European art since the

Middle Ages. He bears an uncanny resemblance to early Gorgoneions, such as the masks from

Tiryns and Thebes (see part 2). Whereas Gorgons are thought to have been intended to scare

away trespassers, here gruesome imagery on the funfare attraction's marquee is designed to entice

customers to enter. People actually pay money in the hope of being frightened out of their wits. |

| |

Medusa

part 1 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. The Gorgon in Homer

In The Iliad, Athena puts on the aegis and the Gorgoneion:

"About her shoulders she flung the tasselled aegis, fraught with terror, all about which Rout is set as a crown, and therein is Strife, therein Valour, and therein Onset, that maketh the blood run cold, and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful, a portent of Zeus that beareth the aegis."

Homer, The Iliad, Book 5, lines 739-740

The Gorgoneion was also part of the decoration on the shield of Agamemnon:

"And thereon was set as a crown the Gorgon, grim of aspect, glaring terribly, and about her were Terror and Rout."

Homer, The Iliad, Book 11, lines 1-46

Homer, The Iliad, translated by A.T. Murray, in two volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.; William Heinemann, London. 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus speaks of his terror of the Gorgon's head during his descent to Hades:

"... so many thousands of ghosts came round me and uttered such appalling cries, that I was panic stricken lest Persephone should send up from the house of Hades the head of that awful monster Gorgon."

Homer, The Odyssey, Book 11, 633

Homer, The Odyssey, translated by Samuel Butler. At Perseus Digital Library.

2. The Gorgons in Hesiod

The poet Hesiod (Ἡσίοδος) is thought to have lived between 750 and 650 BC.

"And again, Ceto bore to Phorcys the fair-cheeked Graiae, sisters grey from their birth: and both deathless gods and men who walk on earth call them Graiae, Pemphredo well-clad, and saffron-robed Enyo, and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean in the frontier land towards Night [i.e. the west] where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two were undying and grew not old. With her lay the Dark-haired One [Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers.

And when Perseus cut off her head, there sprang forth great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus who is so called because he was born near the springs [pegai] of Ocean [Okeanos]; and that other, because he held a golden blade in his hands. Now Pegasus flew away and left the earth, the mother of flocks, and came to the deathless gods: and he dwells in the house of Zeus and brings to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning.

But Chrysaor was joined in love to Callirrhoe, the daughter of glorious Ocean, and begot three-headed Geryones. Him mighty Heracles slew in sea-girt Erythea by his shambling oxen on that day when he drove the wide-browed oxen to holy Tiryns, and had crossed the ford of Ocean and killed Orthus and Eurytion the herdsman in the dim stead out beyond glorious Ocean.

And in a hollow cave she bore another monster, irresistible, in no wise like either to mortal men or to the undying gods, even the goddess fierce Echidna who is half a nymph with glancing eyes and fair cheeks, and half again a huge snake, great and awful, with speckled skin, eating raw flesh beneath the secret parts of the holy earth. And there she has a cave deep down under a hollow rock far from the deathless gods and mortal men. There, then, did the gods appoint her a glorious house to dwell in: and she keeps guard in Arima beneath the earth, grim Echidna, a nymph who dies not nor grows old all her days."

Hesiod, Theogony, lines 270-303.

The myth of Persus and Medusa also appears in the poem Shield of Heracles, attributed to Hesiod, but thought by some scholars to be a later derivative work. It describes the relief of figures and scenes decorating the magic shield.

"There, too, was the son of rich-haired Danae, the horseman Perseus: his feet did not touch the shield and yet were not far from it, very marvellous to remark, since he was not supported anywhere; for so did the famous Lame One [Hephaistos] fashion him of gold with his hands. On his feet he had winged sandals, and his black-sheathed sword was slung across his shoulders by a cross-belt of bronze. He was flying swift as thought. The head of a dreadful monster, the Gorgon, covered the broad of his back, and a bag of silver - a marvel to see - contained it: and from the bag bright tassels of gold hung down.

Upon the head of the hero lay the dread cap of Hades [the cap of darkness which made its wearer invisible] which had the awful gloom of night. Perseus himself, the son of Danae, was at full stretch, like one who hurries and shudders with horror. And after him rushed the Gorgons, unapproachable and unspeakable, longing to seize him: as they trod upon the pale adamant, the shield rang sharp and clear with a loud clanging. Two serpents hung down at their girdles with heads curved forward: their tongues were flickering, and their teeth gnashing with fury, and their eyes glaring fiercely. And upon the awful heads of the Gorgons great Fear [Phobos] was quaking."

Hesiod, Shield of Heracles, lines 216-238

Both quotations from: Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Loeb Classical Library edition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.; William Heinemann, London. 1914. At Perseus Digital Library.

3. The myth of Perseus and the Gorgons in Pherecydes

Pherecydes (Φερεκύδης) was a 5th century BC writer, referred to variously as Pherecydes of Leros (Φερεκύδης ὁ Λέριος) or Pherecydes of Athens (Φερεκύδης ὁ Ἀθηναῖος), with differing opinions on whether they were the same person. He is thought to have been a native of the Dodecanese island of Leros who spent much of his life in Athens.

His Genealogies (οι Γενεαλογίαι), also referred to as Histories, was a work of ten books in the Ionian dialect, recording the popular myths of Greek gods and heroes with a particular emphasis on their genealogies. It was possibly written as propaganda, to demonstrate the divine and heroic pedigrees of prominent families in Attica, who may have been his patrons. The original work is lost, but several passages were quoted or used as sources by later ancient writers.

A fragment of Pherecydes' account of the myth of Perseus and Medusa can be read in:

Stephen M. Trzaskoma, R. Scott Smith, Stephen Brunet, Anthology of classical myth: Primary sources in translation, "Pherecydes, The Histories, fragments", "11 The story of Perseus (fr. 11 Fowler)", page 354. Hackett Publishing, Indianapolis, 2004. At Google Books.

The Library (Βιβλιοθήκη, Bibliotheki) of Apollodorus, an extensive and important source of Greek mythology, was long attributed to Apollodorus of Athens (Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; circa 180 - after 120 BC). However, many scholars now believe it was written at a later date, around 100-200 AD, and the author is often referred to as Pseudo-Apollodorus. He frequently used Pherecydes' works as a source for his retelling of the myths. Book 1 of the Library he discusses the genealogy of the Gorgons:

"And to Sea (Pontus) and Earth were born Phorcus, Thaumas, Nereus, Eurybia, and Ceto. Now to Thaumas and Electra were born Iris and the Harpies, Aello and Ocypete; and to Phorcus and Ceto were born the Phorcides and Gorgons, of whom we shall speak when we treat of Perseus."

He kept his promise, and Book 2 deals at length with the mythical history of Argos and events leading up to Perseus' quest to acquire Medusa's head.

Apollodorus, The Library, Book 1, chapter 2, section 6. Translated by Sir James George Frazer. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, and William Heinemann Ltd., London, 1921. At Perseus Digital Library.

Apollodorus, The Library, Book 2. Same edition. There are several mentions of "the Gorgon" and "Medusa", concerning Bellerophon and Pegasus, Perseus and Andromeda, and Herakles in Hades. The story of Perseus and the Gorgons is in chapter 4, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

The translator's notes: "The following legend of Perseus (Apollod. 2.4.1-4) seems to be based on that given by Pherecydes in his second book, which is cited as his authority by the Scholiast on Ap. Rhod., Argon. iv.1091, 1515, whose narrative agrees closely with that of Apollodorus."

For a brief overview of sources of the Perseus myth, see:

Ulrike Kenens, Greek Mythography at Work: The Story of Perseus from Pherecydes to Tzetzes. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 52 (2012), pages 147–166.

4. Hyginus on Gorgon, child of Typhon and Echidna

The list of Typhon and Echidna's children in the "Fabulae Preface" appears in the Fabulae itself. While Hyginus explains who the other children were, all we learn about Gorgon is that Medusa was his/her/its child. In the Preface Sthenno, Eurylae, Medusa were children of Gorgon and Ceto, normally taken to be female. According to one modern source, "the primal Gorgon was of an indeterminable gender".

"From Typhon the giant and Echidna were born Gorgon, the three-headed dog Cerberus, the dragon which guarded the apples of the Hesperides across the ocean, the Hydra which Hercules killed by the spring of Lerna, the dragon which guarded the ram’s fleece at Colchis, Scylla who was woman above but dog below, with six dog-forms sprung from her body, the Sphinx which was in Boeotia, the Chimaera in Lycia which had the fore part of a lion, the hind part of a snake, while the she-goat itself formed the middle. From Medusa, daughter of Gorgon, and Neptues, were born Chrysaor and horse Pegasus; from Chrysaor and Callirhoe, three-formed Geryon."

Hyginus, Fabulae sections 150-199, section 151, Children of Typhon and Echidna. At the Theoi Project.

5. The Gorgons in Euripides

Euripides (Εὐριπίδης, circa 480-406 BC). A dialogue between Queen Kreusa (Κρέουσα) of Athens and the Tutor (Πρεσβύτης), in the play Ion (Ίων), written around 414-412 BC. In various translations Gorgon is referred to either as "she" or "it".

"Creusa: Listen, then; you know the battle of the giants?

Tutor: Yes, the battle the giants fought against the gods in Phlegra.

Creusa: There the earth [Gaia] brought forth the Gorgon, a dreadful monster.

Tutor: As an ally for her children and trouble for the gods?

Creusa: Yes; and Pallas, the daughter of Zeus, killed it.

Tutor: [What fierce shape did it have?

Creusa: A breastplate armed with coils of a viper.]

Tutor: Is this the story which I have heard before?

Creusa: That Athena wore the hide on her breast.

Tutor: And they call it the aegis, Pallas' armor?

Creusa: It has this name from when she darted to the gods' battle."

Euripides, Ion, lines 987-997

Ion, translated by Robert Potter, in Euripides, The complete Greek drama, Volume 1 (of 2), edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill Jr. Random House, New York, 1938. At Perseus Digital Library.

See also:

Euripides, Ion, translated by George Theodoridis. At Poetry in translation, A. S. Kline's FREE Poetry Archive.

Euripides, Heracles, 977, in Euripides, The complete Greek drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill Jr. in two volumes. 1. Heracles, translated by E. P. Coleridge. Random House, New York, 1938. At Perseus Digital Library.

Euripides is satirized by Aristophanes (circa 446-386 BC) in his comedy Thesmophoriazusae, first produced in 411 BC:

"Euripides now enters, costumed as Perseus.

Euripides: 'Oh! ye gods! to what barbarian land has my swift flight taken me? I am Perseus; I cleave the plains of the air with my winged feet, and I am carrying the Gorgon's head to Argos.'

Scythian Archer: What, are you talking about the head of Gorgos, the scribe?

Euripides: No, I am speaking of the head of the Gorgon."

Aristophanes, Thesmophoriazusae, Lines 1098-1135

Aristophanes, Women at the Thesmophoria, in: Eugene O'Neill Jr., The complete Greek drama, Volume 2. Random House, New York, 1938. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

|

6. The home(s) of the Gorgons

a) Near the Garden of Hesperides

The name of Hesperides (Ἑσπερίδες) is derived from hesperos (evening), the origin of the name Hesperus, the evening star (Venus), and was associated with the west. The Hesperides were the nymphs of evening and the golden light of sunset, the "daughters of the evening" or "nymphs of the west". They lived in the Garden of Hesperides at the western edge of the known world, on the world-encircling ocean (Okeanos, the modern Atlantic Ocean), near the Atlas Mountains in North Africa.

It was here that Herakles received the Golden Apples of Hesperides from Atlas. The famous rocks on either side of the Straits of Gibraltar - the boundary between the Mediteranean and the Atlantic - are known as the Pillars of Hercules.

For Hesiod on the home of the Gorgons near the Hesperides, see note 2 above.

b) Libya

The Greeks used the name Libya (Λιβύη) to refer generally to the area of north Africa west of the Nile, known later as Cyrenaica (Κυρηναϊκή, Kyrenaike) after the city of Cyrene (Κυρήνη; Benghazi, Libya), particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. As the name of an area loosely defined in geographical terms, it may roughly correspond to Hesiod's mythological Hesperides.

See:

Herodotus, Histories, Book 2, chapter 91. At Perseus Digital Library.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 4 lines 604-705. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias briefly discussed mythological tales of Medusa's Libyan origin. The inhabitants of Argos believed that her head was buried at the monument of the Gorgon in their agora, and he attempted a "rational" interpretation of the local myth by making her a daughter and successor of Phorcys (Φόρκυς) as a local ruler in Libya, assassinated at night by Perseus, the commander of a Peloponnesian special forces operation.

He also included the account by the Carthaginian writer Prokles (Προκλῆς), son of Eukrates, whose works are otherwise unknown *, that Medusa was one of the monstrous savages who lived in the Libyan desert, and was killed by Perseus at Lake Tritonis (Τριτωνίδα λίμνην, location unknown, perhaps in the southeast of modern Tunisia).

"Not far from the building in the market-place of Argos is a mound of earth, in which they say lies the head of the Gorgon Medusa. I omit the miraculous, but give the rational parts of the story about her. After the death of her father, Phorcus, she reigned over those living around Lake Tritonis, going out hunting and leading the Libyans to battle. On one such occasion, when she was encamped with an army over against the forces of Perseus, who was followed by picked troops from the Peloponnese, she was assassinated by night. Perseus, admiring her beauty even in death, cut off her head and carried it to show the Greeks.

But Procles, the son of Eucrates, a Carthaginian, thought a different account more plausible than the preceding. It is as follows. Among the incredible monsters to be found in the Libyan desert are wild men and wild women. Procles affirmed that he had seen a man from them who had been brought to Rome. So he guessed that a woman wandered from them, reached Lake Tritonis, and harried the neighbours until Perseus killed her. Athena was supposed to have helped him in this exploit, because the people who live around Lake Tritonis are sacred to her.

In Argos, by the side of this monument of the Gorgon, is the grave of Gorgophone [Gorgon-killer], the daughter of Perseus. As soon as you hear the name you can understand the reason why it was given her. On the death of her husband, Perieres, the son of Aeolus, whom she married when a virgin, she married Oebalus, being the first woman, they say, to marry a second time; for before this wives were wont, on the death of their husbands, to live as widows."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 21, sections 5-7. At Perseus Digital Library.

* For a discussion on the identity of Prokles, see:

Juan Pablo Sánchez Hernández, Prokles the Carthaginian: A North African Sophist in Pausanias' Periegesis. In: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 50 (2010), pages 119-132. At Duke University Libraries. Hernández argues that Prokles was probably was not a historian of the Hellenistic period, as has been assumed, but a Sophist and a contemporary of Pausanias.

Pausanias had previously mentioned the connection between Athena and the Libyan Lake Tritonis (Τριτονίς, also the name of the lake's nymph) when explaining why a statue of Athena outside the Temple of Hephaistos in Athens had blue eyes:

"But when I saw that the statue of Athena had blue eyes I found out that the legend about them is Libyan. For the Libyans have a saying that the goddess is the daughter of Poseidon and Lake Tritonis, and for this reason has blue eyes like Poseidon."

Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 14, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Athena's Libyan origins were also related by other ancient authors. The geographer Ptolemy described the Libyan River Triton (ὁ Τρίτων ποταμός) as having three lakes: the Libya Palus, Pallas and Tritonitis (Claudius Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos, Book 4, chapter 3). Palus and Pallas may have been parts of Lake Tritonis. Pallas (Παλλας, Spear Brandishing) was a nymph associated with Athena's youth, and the name was also an epiphet of the goddess.

Another of Athena's epiphets was Tritogeneia (Τριτογένεια), known since Homer (The Iliad, 4.514; The Odyssey, 3.378), the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod (Theogony), the meaning of which is unknown (and much debated), but may be Triton Born. Pausanias pointed to the competing myths that Athena was so called because she was born or grew up either beside the Triton in Libya or the river of the same name near Alalcomenae in Boeotia, central Greece.

"Here too there flows a river, a small torrent. They call it Triton, because the story is that beside a river Triton Athena was reared, the implication being that the Triton was this and not the river in Libya, which flows into the Libyan sea out of lake Tritonis."

Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 33, section 7.

c) Sarpedon

A number of places named Sarpedon (Σαρπηδών) were mentioned by ancient authors, including locations to the east, rather than west, of Greece:

Cape Sarpedon, east of the river Hebros (Evros), Thrace (Strabo, Geography, Book 7, fragments);

Cape Sarpedon in Cilicia, on the south coast of Anatolia (Asia Minor), opposite Cyprus (Strabo, Geography, Book 5, chapter 5 and Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 5, chapter 22).

However, a commentary on the poem Song of Geryon by the Sicilian Greek poet Stesichorus (Στησίχορος, Stesikhoros, circa 630-555 BC), mentions Sarpedon as an island in Okeanos, west of Greece:

"Stesikhoros in his Geryoneis calls an island in the Atlantic sea Sarpedonian."

Stesichorus, Geryoneis Fragment S86 (from Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius).

See: www.theoi.com/Kosmos/Erytheia.html

A fragment of an Archaic Greek poem (also from the Song of Geryon?) locates the Gorgons on a western Sarpedon island:

"By him she conceived and bare the Gorgons, fearful monsters who lived in Sarpedon, a rocky island in deep-eddying Oceanus."

Herodian, On Peculiar Diction, The Cypria, Fragment 21: the Gorgons. From the Epic Cycle, fragments of epic poems composed between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, describing the Titan war, the Theban saga and the Trojan War.

See: www.theoi.com/Text/EpicCycle.html

The Song of Geryon deals with myths, including Herakles stealing the cattle of the three-bodied giant Geryon, the grandson of Medusa, on the island Erytheia (Νησος Ερυθεια, Red Isle) in the western Mediterranean.

d) Kisthene

In Aischylos' play Prometheus Bound (written around 430 BC), Prometheus tells Io that the Graiae and Gorgons live at a place called Kisthene (Κισθήνη) on "the Gorgonean plains", east of Greece:

"Well, since you are bent on this, I will not refuse to proclaim all that you still crave to know. First, to you, Io, will I declare your much-vexed wandering, and may you engrave it on the recording tablets of your mind.

When you have crossed the stream that bounds the two continents, toward the flaming east, where the sun walks, ...

crossing the surging sea until you reach the Gorgonean plains of Cisthene, where the daughters of Phorcys dwell, ancient maids, three in number, shaped like swans, possessing one eye amongst them and a single tooth; neither does the sun with his beams look down upon them, nor ever the nightly moon. And near them are their three winged sisters, the snake-haired Gorgons, loathed of mankind, whom no one of mortal kind shall look upon and still draw breath."

Aeschylus, Prometheus bound, lines 780-818, translated by Herbert Weir Smyth. Harvard University Press. 1926. At Perseus Digital Library.

"The stream that bounds the two continents, toward the flaming east" must refer to the Hellespont, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus which divide Europe from Anatolia (Asia Minor). The virtual traveller must then cross "the surging sea" to reach the Gorgonean plains of Cisthene. The Gorgonean plains are otherwise unknown, but Kisthene (Κισθήνη) was the name of two ancient Greek settlements in Anatolia:

A coastal city of Mysia, northwest of Pergamon, deserted by the time of Strabo (circa 64 BC - 24 AD), Geography, Book 13, chapter 1;

An island with a city of the same name off the coast of Lycia, southwestern Anatolia (Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 3, section 7), identified by some scholars as Kastellorizo (Megiste).

7. The Gorgons in Ovid's Metamorphoses

The Metamorphoses by Ovid, Book IV, lines 753-803, "Perseus tells the story of Medusa".

At poetryintranslation.com.

A. S. Kline has provided an excellent prose translation in clear modern English. Mythological, historical and geographical names in the text are hyperlinked to a cross-referenced index which also acts as a glossary.

An older, arcane translation:

Brookes More (editor), Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 4, lines 706 to end. Cornhill Publishing Co., Boston, 1922. At Perseus Digital Library.

In several translations of Ovid, Medusa is "violated" (A. S. Kline) or "abused" (Arthur Golding, 1567) by Poseidon. The earlier versions of the myths do not specify that Poseidon raped Medusa. Hesiod, for example, wrote: "With her lay the Dark-haired One [Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers." [see note 2 above] The poetic setting of soft meadow amid spring flowers lends the incident a more tender, almost romantic tone.

8. Perseus and the Gorgon's head in Anatolia

There were other local Greek myths and legends about Perseus' use of the Gorgon's head as a weapon. The Greeks took over an ancient city of Phrygia or Lycaonia in Anatolia which they called Ikonion (Ἰκόνιον, also Εἰκόνιον; Latin, Iconium; today Konya, Turkey). According to local tradition, Perseus defeated the local population there by using the Gorgon's head (εἰκών, icon, image), founded the city and set up the Gorgoneion on a pillar. Coins of Ikonion show Perseus walking left, holding a harpa and the head of Medusa. |

|

|

|

9. Pausanias on the Acropolis Gorgoneion

Antiochus is thought to have been Antiochus IV Epiphanes (Ἀντίοχος Δ΄ ὁ Ἐπιφανής, Antiochos D' o Epiphanes, God Manifest, circa 215-164 BC), king of the Seleucid Empire (ancient Syria) 175-164 BC. It has been suggested that the curtain in Olympia may have been the veil of the Holy of Holies from the Jewish temple in Jerusalem (the Second Temple) which Antiochus had desecrated and looted in 168/167 BC:

"And so he stripped the temple, carrying off the vessels of God, the golden lampstands and the golden altar and table and the other altars, and not even forbearing to take the curtains, which were made of fine linen and scarlet, and he also emptied the temple of its hidden treasures, and left nothing at all behind, thereby throwing the Jews into deep mourning."

Titus Flavius Josephus (circa 37-100 AD), Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, chapter 5, section 4).

Josephus, Volume 7 (of 9), Jewish Antiquities, Books 12-14, translated by Ralph Marcus. Loeb Classical Library, 1957. At the Internet Archive.

Josephus elsewhere provides a fuller description of the veil, which is similar to that in the Old Testament, Exodus, chapter 26, verses 1-37.

The suggestion was first made by Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846-1923), in Le dieu Satrape et les Phéniciens dans le Pélaponèse: notes d'archéalogie orientale, pages 56-63. Extract from the Journal Asiatique. Imprimerie Nationale, Paris, 1878. At the Internet Archive.

See also:

André Pelletier, Le "Voile" du temple de Jérusalem est-il devenu la "Portière" du temple d'Olympie?, in Syria, Revue d'art oriental et d'archéologie, Tome 31, pages 289-307. l’Institut français d'archéologie de Beyrouth, Paris, 1955. At Persée.

Peter Levi (translator), Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Volume 2: Southern Greece, Book 5, chapter 12, section 4, note 110 on page 231. Penguin Books, 1971.

10. Νiccοlo da Martoni on the Acropolis idol

See:

James Morton Paton, Chapters on Mediaeval and Renaissance visitors to Greek lands, edited by L.A.P., Chapter 3 Niccolò da Martoni, pages 30-35. Gennadeion Monographs III. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton, New Jersey, 1951. PDF e-book at ascsa.edu.gr.

Crusader Athens III: Florentine Athens (1388-1456) by John L. Tomkinson. At anagnosis.gr.

11. Billon coins from Lesbos

Billon is an alloy of a precious metal (silver or gold) with a baser metal (e.g. copper, zinc, tin), used mainly for coins and medal production. The earliest staters minted on Lesbos, made of this alloy, contained a high percentage of base metal, because, it is believed, at the time the islanders possesed little gold or silver. Thus their standard of coinage was not compatible with other currencies.

See: Colin Mackennal Kraay (1918-1982), Archaic and Classical Greek coins (1976), No. 107 (circa 500 BC), pages 38-39.

12. Two electrum half staters from Anatolia

The coin in Berlin was acquired by Fox in 1865 from the collection of James John Whittall (1819-1883), a British merchant born in Smyrna (Izmir). See:

id.smb.museum/object/2352970/elektron at the website of State Museums Berlin (SMB).

For further details about the example in the British Museum, see:

britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_1877-0704-2 at the British Museum website.

Both museums appear to agree that the coin type was struck to the Phocaean standard ("Geprägt im phokäischen Münzfuß"), and according to the British Museum description also minted in Phocaea (Φώκαια, Phokaia; today Foça, Marmara Region, Turkey), the northernmost city of Ionia. It has also been suggested that they may be from further north, the Mysian city of Parion (Πάριον; at the modern village Kemer, near Biga, Çanakkale province, Turkey), on the south coast of the Hellespont (Dardanelles), which had a long tradition of putting Gorgons on their coins.

See also: Florian Haymann, Politische und andere Deutungsmöglichkeiten von Gorgoneia auf Münzen. In: OZeAN (Online Zeitschrift zur antiken Numismatik), Jahrgang 4 (2022), pages 1-32. Forschungsstelle Antike Numismatik der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster.

doi: doi.org/10.17879/ozean-2022-3799

Haymann wrote that probably only two extant examples of this coin type are known, and briefly discussed that in the British Museum (pages 6-7, Abbildung 2). Unfortunately, he did not identify the second example. He pointed out that the location of the mint and dating of the type remain subjects of debate, but placed them between early Archaic and Attic (Athenian) types of coins with a Gorgoneion.

His article also discusses the various aspects and significance of the use of Gorgoneions on coins through ancient history and tradition, including their relevance to political propaganda. He saw no evidence that Gorgoneions on coins were intended to have an apotropaic effect or a solar-astral aspect.

13. Cast bronze coins from Olbia

See: Florian Haymann, Politische und andere Deutungsmöglichkeiten von Gorgoneia auf Münzen, page 12 and Abbildung 14. [see note 12]

14. Medusa on coins

The number of articles dealing with coins depicting Gorogons and the myth of Perseus and Medusa is steadily increasing, particularly on the internet. See, for example, the photos and articles at medusacoins.reidgold.com.

15. Medusa: from beast to beauty

See: Susan M. Serfontein, Medusa: from beast to beauty in Archaic and Classical illustrations from Greece and south Italy. M.A. thesis. Hunter College of the City University of New York, 1991.

"The primary aim of this thesis is to determine when the transformation of Medusa from a hideous monster into a beautiful woman initially occurs and whether this transformation is simultaneous with regard to both her full-figure representations and the gorgoneia."

See also: Olga A. Zolotnikova, A hideous monster or a beautiful maiden? Did the Western Greeks alter the concept of Gorgon? In: Heather L. Reid, Davide Tanasi (editors), Philosopher Kings and Tragic Heroes: Essays on Images and Ideas from Western Greece, pages 353-370. Parnassos Press – Fonte Aretusa, 2016. At jstor.

16. Servius on the aegis

Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil, A. 8.435, (in Latin). Edited by Georgius Thilo. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1881. At Perseus Digital Library.

17. Perseus beheading Medusa in New York

See also an Attic red-figure pelike (jar), circa 450-440 BC, attributed to Polygnotos, with a finely drawn depiction of Perseus beheading the sleeping Medusa. Perseus, naked except for cloak, winged cap and boots, looks back to Athena while using a harpe to decapitate Medusa as she sleeps. One of the earliest depictions of Medusa as a beautiful young woman rather than a hideous monster.

Metropolitan Museum, New York. Inv. No. 45.11.1.

See: metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254523 |

|

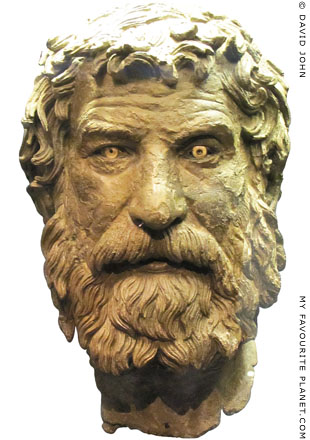

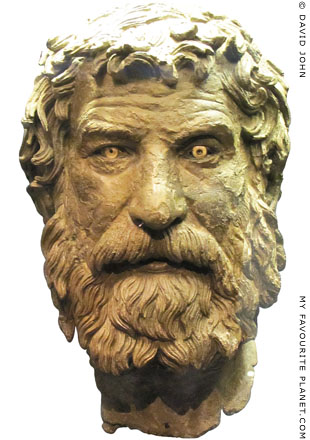

Marble head of Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

Around 175 BC. Provenance unknown,

said to be from the collection of Giampietro

Campana (see note in Medusa part 6).

Height 24.3 cm.

The smaller than lifesize head was made

for a statue. The headband, short hair

and exceptional features match depictions

of the Hellenistic king on coins.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1975.5.

Purchased on the art market in

Frankfurt am Main in 1975. |

|

18. The Antikythera shipwreck