Kastellorizo

history |

A visit to Kastellorizo, April 1840 |

|

|

|

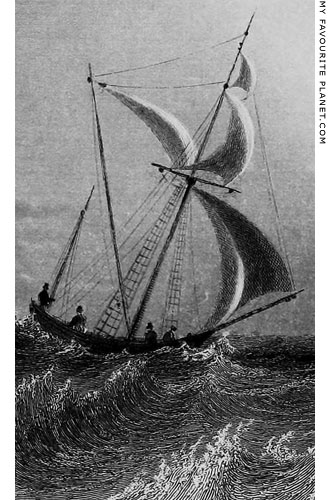

A sketch of Kastellorizo made during the visit to the island

by Charles Fellows and George Scharf in April 1840.

The windmill can be seen on the east (right) side of

the hill, below the Castle of the Knights of Saint John. |

| |

The British archaeologist Charles Fellows (1799-1860) travelled through southwestern Anatolia in 1838 and again in 1840, 1842 and 1843, discovering and exploring a number of ancient Lycian cities, most notably Xanthos, which he described as "my favourite city", and from where he later took artefacts, including the surviving parts of the famous Nereid Monument, for the British Museum (see Museum boom part 1 at The Cheshire Cat Blog). He mentioned Kastellorizo as an "important island" and its proximity to Antiphellos (Kaş) in the journal of his first journey:

"April 18th. This morning we continued the ascent for two hours, and, after passing some richly wooded ravines, we rapidly descended upon the singularly beautiful but wild and barren neighbourhood of Antiphellus, an active little trading harbour for firewood, containing two or three houses for official persons, and one or two boats to communicate with the important island of Castellorizzo, a few miles from the shore. The ancient town of Antiphellus stood on a finely situated promontory, which still presents a theatre, foundations of temples, and other buildings; but the chief objects of interest in the place are the tombs, which are very numerous, and of the largest kind that I have seen."

Charles Fellows, A journal written during an excursion in Asia Minor, 1838, page 219. John Murray, London, 1839. At the Internet Archive.

On his second journey, made under the auspices of the British Museum, he was accompanied by the artist George Scharf (1820-1895), who later became the director of the National Portrait Gallery, London. In April 1840 they rode to Antiphellos, and on the 24th sailed over to Kastellorizo.

Like many travellers before and since, Fellows, as he admitted himself, carried his prejudices with his luggage, but seems to have enjoyed his short visit to the island, and expressed admiration for the Greeks who lived there, "such an intelligent-looking assemblage of people, both male and female". He described the port itself as a thriving and growing town, while at that time Antiphellos consisted of "only three or four houses and a custom-house".

The fact that Fellows and Scharf had to sail to Kastellorizo to buy supplies underlines its importance to the local economy at the time, and indicates how remote the farming villages of mainland Lycia were, and in some respects still are today, even though Kaş now has much more to offer shoppers than the island. This role reversal has only occurred over the last twenty years, as Kaş has grown from a sleepy village into the area's largest tourist resort.

The sketches above and below, made during their visit to the island, appear in Fellows' journal of his second journey. He kept sketchbooks of his journeys, and wrote that he made the drawings illustrating the text of the first journal. However, he did not make clear whether these particular sketches were drawn by him or were by Scharf, who he had engaged as an artist to record the voyage. [9]

Fellows' journal entry, written in Antiphellos on 25th April 1840, the day after his visit to the island:

"Yesterday we went to the island of Kastelorizo, to lay in stores and to refit ourselves with supplies; the distance may be five or six miles from the shore. The town – for it really deserves the name – consists probably of six or eight hundred houses, all built upon one model, being formed like cubes, with two or three open square windows in the front of each, and a door at the back. These are built up the side of a steep rock, and, viewed together, are more singular-looking than picturesque. An old castle of the middle ages crowns the rock, and gives a character to the city.

On landing in this island, the effect was that of visiting a new country: hundreds of Greeks were crowding about the little quay and coffee-houses; wine was being retailed from the cask in the dirty narrow streets; scarcely a dog was to be seen, and pigs supplied their place. We were told that there were five Turks only in the town, the whole population being Greek. A number of small vessels filled the harbour; boats were building, houses rising rapidly, and the whole population seemed active and enterprising: it is quite delightful to see such an intelligent-looking assemblage of people, both male and female, in this busy scene; but a host of pure and simple feelings pass from the mind, and are succeeded by caution and worldliness, which are seldom sufficient to compete with the cunning of the Greek. |

| |

| |

This is a metropolis of trade for the whole of the south-western coast: all provisions, and even coins and treasures of every kind discovered by the peasants, find a ready market here. I have obtained several coins, just brought from the valley of the Xanthus, and also saw some singular gems, but the devices were probably more illustrative of the whims of their former owners than of history.

The island of Kastelorizo, which was the ancient Megiste, is perfectly barren of natural supplies; even the water for the use of the town is collected in large tanks, about a mile up the mountain, whence it is carried by the women, who are continually passing and repassing in most classic groups, with pitchers slung over their shoulders.

The jewelry of these people is particularly interesting, being precisely the same as that seen upon the statues of the ancients. I wished much to purchase a bracelet or armlet, but could not obtain any; they are handed down as heir-looms, and, should an additional one be required, it is made expressly from these models, but they are never kept for sale: by this mode the pattern is perpetuated, and I feel certain that we here see the models of the ornaments of the ancient Greeks: several of these are often seen worn on the same arm, serving as the quartering in an heraldic shield, to register the families centered in the living heiress.

The jewels, or rather gold ornaments, are often thus accumulated to a great value; some of the people we saw with their savings'-bank, if I may use the expression, around their necks, in twenty or forty piastre-pieces of modern Turkish gold – some chains containing the current value of above a hundred pounds. But the characteristic ornament of the peasantry of this island is a row of large fibulae or broaches, of chased silver, three inches in diameter, placed one below the other, from the throat to the waist, which is very low; the rest of the dress is, as I have before described, purely classic in all its forms.

Leaving the path which leads to the fountains, we ascended the heights above the town, to seek the ruins of the city of the early inhabitants of Megiste: some fine Cyclopean walls scattered about the top point out the site, but no further remains are to be traced.

A brisk gale carried us back in less than an hour to our abode at Antiphellus, or, as the little Scala is now called by the Turks, Andiffelo. It consists of only three or four houses and a custom-house."

Charles Fellows, An account of discoveries in Lycia, being a journal kept during a second excursion in Asia Minor, pages 187-190. John Murray, London, 1841. At the Internet Archive. |

|

A drawing of a Kastellorizian woman wearing her

traditional costume and jewellery, from Fellows' journal.

See photos of local costumes on gallery pages 169-173. |

|

| |

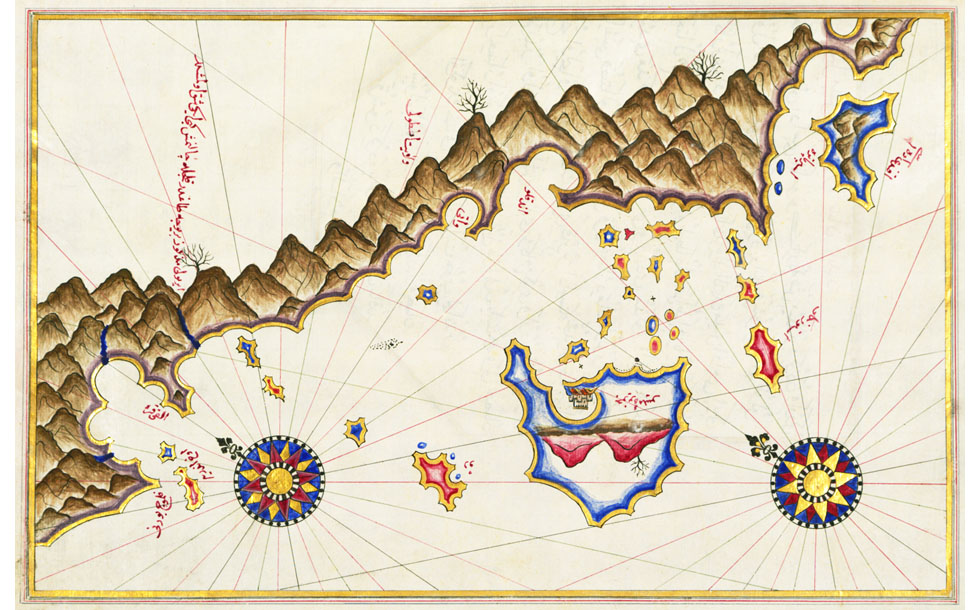

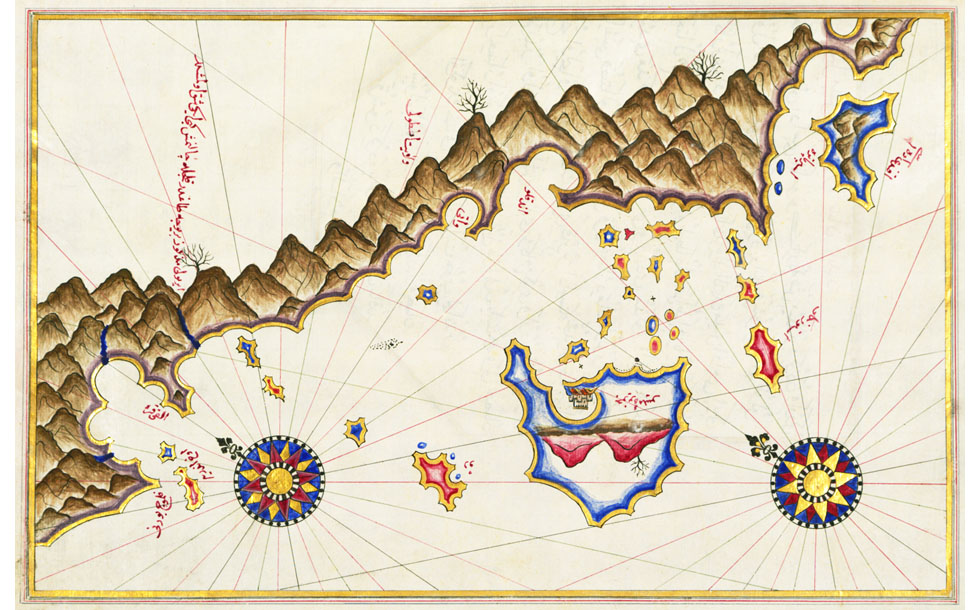

A 16th century map of Kastellorizo and the Lycian coast by the Turkish cartographer Piri Reis.

|

Ahmed Muhyiddin Piri Bey (or Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Piri Bey; circa 1467-1554), better known as Piri Reis (Admiral Piri), was an Ottoman Turkish admiral and cartographer, born either in Karaman in Southern Anatolia (the birthplace of his father; see below), or Gelibolu (Gallipoli), Turkish Thrace, in the Dardanelles. He was in active service as a captain then admiral of the Ottoman navy, around Spain, North Africa and Egypt, in the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean, as well as around the coast of Arabia, from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf.

The two main editions of his Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book of maritime matters, also referrred to as Book of navigation) were completed in 1521 (927 AH) and 1525 (932 AH), although there are a number of different versions, including those produced after his death. He dedicated the second edition to Sultan Süleyman I the Magnificent. The books contains navigational instructions and several maps of specific areas and harbours around the Mediterranean Sea. Some copies of the second edition also included charts of the Black Sea, Arabia and world maps. In 1513 Piri Reis had also made a world map which is the oldest surviving map to show the Americas. He wrote that much of his information was taken from works by ancient and contemporary map makers, and even claimed to have used a map from the age of Alexander the Great, although it is thought more likely that he used a map based on geographical coordinates in the Geographia of the Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy (Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος, circa 100-170 AD), which had been translated into Arabic in the 9th century.

His maps are beautifully drawn, with vivid colours and clear calligraphy, and include topographical hints such as hills, mountains, buildings and sometimes entire cities, although some of these appear works of imagination rather than historical depictions. Each is a outstanding work of art with something of the traditions of Persian and Turkish miniatures and book illumination. Given the conditions and technology of the time, they are appear remarkably accurate. The coastlines of Kastellorizo, the other islands and the Lycian coast are clearly recognizable. Unfortunately, I have not yet found transcriptions or translations of the names or other text, written in Turkish in Arabic script, which these days only a relatively small number of scholars can read.

The map above is taken from the copy of the book in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. Walters manuscript W.658, based on the later expanded version, with around 240 maps and portolan charts, including a world map with the outline of the Americas. The museum has generously put the maps online, including a PDF version of the entire book. The locations on some of the maps, including this one, are subtitled as "unidentified". Map of unidentified islands off the southern Anatolian coast.

Height of entire page 34 cm, width 24 cm.

This folio from Walters manuscript W.658 contains a map

of unidentified islands off the southern Anatolian coast.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. Inv. No. W.658.338B.

Source: Map of unidentified islands off the southern Anatolian coast,

Creative Commons licensed work at the Walters Art Museum.

The start page of the Walters section on the Kitab-ı Bahriye: Book on Navigation, with an introduction and a downloadable PDF of the book. If you scroll further down page you will see thumbnails of individual maps linked to larger, zoomable versions. Very well designed. |

|

Part of the map by Piri Reis, turned

180 degrees to show the Knights' Castle. |

|

| |

Detail of a map of Anatolia (Asia Minor) and the islands, published by Richard Pococke in 1745 [see note 8].

|

This section of the map shows the Lycian coast, between Rhodes in the west and "Satalia" (Antalya) to the east. I have highlighted "I. Castello Rosso" and "Chelidonian" [see note 8] in yellow. Several of the speculative identifications of ancient locations by Pococke and his scholarly contemporaries were later proved to be inaccurate. For example, the River Xanthus and Patera are shown to the east of Kastellorizo, but are actually northwest of the island.

Source: Richard Pococke, A Description of the East and some other countries, Volume 2, Part II, Observations on the islands of the Archipelago, Asia Minor, Thrace, Greece, and some other Parts of Europe, Book II, chapter I, opposite page 33. Printed for Pococke by W. Bowyer, London, 1745. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

A map of "Isle de Chateau Rouge" (Kastellorizo), the surrounding

islands and part of the mainland coast between Kaş and Kalkan,

by the French cartographer Joseph Roux (1725-1793).

|

Joseph Roux was from a family of hydrographers and marine painters specializing in paintings of ships, from Marseilles. He also manufactured and sold navigating instruments and nautical equipment, and published a variety of charts. The charts seem crude and clumsily drawn, and the style belongs to an earlier age of simple woodcuts, but they nevertheless appear to have proved useful to navigators since were reprinted a number of times over several generations, and were still in use during the Napoleonic Wars. Roux was appointed Hydrographe du Roi (Hydrographer to the King), and he dedicated the collection of charts from which this map was taken to "Monsieur Duc de Choiseul, Ministre del la Guerre et de la Marine", indicating that they were of great importance to the French navy. Such maps were produced, then as now, not only as aids to sailors, travellers and scholars, but also as essential tools of military intelligence.

In this map, Kastellorizo's two northern harbours are shown, and the water depths and anchorage points are marked, as well as the Knights' Castle and other buildings. The island of Ro, to the west, is marked as "I. S Georgio" (Isle of Saint George), and Stroggyli, to the east, as "I. des Gouzens".

The mainland is marked "Caraminia" (Karaminia), the unofficial name given by Europeans in the 18th-19th centuries to the entire southwestern and southern coast of Anatolia on the Mediterranean (south of the Aegean), taken from the Ottoman Karaman Eyalet (province), around the town of Karaman (ancient Laranda, Λάρανδα), on the south coast. Three harbours are shown, from west to east: Pt. Vaty (Port Vathy, today Kaş), Pt. Longue and Pt. Senede.

Karaman may have been the birthplace of the Turkish admiral and cartographer Piri Reis ( see above).

Source: Joseph Roux, Joseph Roux, Receuil des principaux plans, des ports, et rades de la Mer Mediterranée. Estraits de ma carte en douze feuilles ( Compilation of the principal plans of the ports and harbours of the Mediterranean Sea. Extracts from my map in twelve sheets), Planche 167. Marseilles, 1764. At Googlebooks. |

|

| |

Kastellorizo

history |

Beaufort map of Lycia |

|

|

|

Part of the coast of Lycia around Kastellorizo. Detail of a map of "South coast of Asia Minor,

commonly called Karamania", made by Captain Francis Beaufort 1811-1812.

Source: Francis Beaufort, Karamania. London, 1817. See details below. |

| |

In 1811-1812 Captain Francis Beaufort (1774-1857), British Royal Navy officer and hydrographer made a survey of the coast of Lycia (the area then generally referred to by Europeans as Karamania) for the British Admiralty, aboard HMS Frederikssteen, a 32-gun frigate which had been stationed in the Greek islands. [10] The survey provided data for maps and nautical charts of the area, and presumably a deal of intelligence for the British military about a region until then seldom visited or explored by westerners. In 1817 Beaufort published an account of his voyage, concentrating mainly on the ancient remains he and his crew encountered during their voyage along the coast.

"From thence we proceeded along a high, rugged shore; and after examining several barren islands, the ship anchored off the harbour and town of Kastelorizo, on the eastern side of a large rocky island of that name. The harbour, though small, is snug; merchant ships of any size can moor within a hundred yards of the houses; and on the other side, they may even lie so close to the shore as to reach it on a plank.

Two old castles command the town, the harbour, and the outer anchorage; but in a former war they were taken by the Russians, and almost destroyed. From the uppermost, which stands on a picturesque cliff, the muzzles of a few small cannon still project; but the Turks, to conceal its weakness, allow no strangers to enter. On the summit of the island, which is about eight hundred feet above the level of the sea, there is another small ruined fortress, which from its situation must have been impregnable. Vertot says, that the knights of Rhodes kept possession of this island for a long time; these castles and fortifications, which appear to have the character of the European architecture of the middle ages, may have been their work.

The island of Kastelorizo produces absolutely nothing; meat, fruit, corn, and vegetables, all come from the continent, which, though barren, and devoid of culture in its external appearance, contains inland, it is said, many spacious and productive vallies. It, therefore, requires some time for a ship to procure a supply of provisions, and especially of live stock. A small bullock of about three cwt. [11] cost eight dollars: and brinjoes (Solanum Melongena), grapes, water-melons, and pumkins, were proportionably cheap.

Water is scarce on this part of the coast: from the valley of Patara to the river of Myra, an uninterrupted range of mountains, abruptly rising from the sea, forbids the passage of any stream: the winter torrents cease with the rains; and from April to November, the inhabitants have no resource but in the capacity of their reservoirs. In summer, therefore, ships are very reluctantly allowed to fill their water-casks.

The town is principally inhabited by Greeks, but under the government of a Turkish Agha,* who is dependant on the Bey of Rhodes. Pilots may generally be met with here, for vessels bound to any part of this coast, or to Syria, and even to Egypt; for Alexandria being supplied, in a great measure, with fuel from the woody mountains of Karamania, there is a constant intercourse between that place and this little port.

From the gulf of Makry to Cape Khelidonia, the sea-shore is composed of a white limestone; but in this island an ochry drip, exuding from between the strata, gives a reddish tinge to the cliffs. From this circumstance it probably acquired the Italian name of Castelrosso; and it is not impossible that the present name Kastelorizo, which has no signification in modern Greek, or Turkish, may be derived from thence; for we find that many sea terms, as well as names of places, have been adopted from European sailors. However that may be, it is now called and written as above; and it appeared to me more judicious to retain the vernacular names, wherever they could be distinctly ascertained, than to adopt those applied by other foreigners. The custom of inventing new names is still more pernicious to the true interests of geography.

This island was undoubtedly the Megisté of Livy, Pliny, and Ptolemy. For by comparing the three passages of the former historian, where that name occurs (Livy, Book 37, 22, 24, 45); we learn that Megiste had a harbour; that it was to the eastward of Patara; and that it was not far distant from that city. From the two latter (Pliny, Book 5, chapter 31; Ptolemy Geog. in Lycia), it appears that it was an island, and to the westward of the sacred promontory. All these circumstances will apply to the island of Kastelorizo, and to no other place. The name Megisté is in itself almost conclusive, for Kastelorizo is by far the largest island of Lycia. It is singular that Strabo does not mention Megisté; but as he gives the name of Cisthené (Strabo, in Lycia), to the most considerable of the Lycian islands, we may safely infer that Kastelorizo was likewise the Cisthené of that geographer.

Kastelorizo forms the west side of a gulf which is crowded with small islands and rocks; and which communicates with two capacious harbours, Sevedo and Vathy [12]. The former has almost every good quality that can be desired ; and a tongue of rock projects from the head of the harbour, forming a natural pier, with sufficient depth of water for a ship of the line to heave down.

In the limestone cliffs, that rise from Port Sevedo, there are several sepulchres, or catacombs, hollowed out of the rock; they contain numerous cells, and were originally closed with stone doors: many sarcophagi are also scattered on the side of the hill. There are no remains of any buildings worth noticing, except a square column standing on the top of a neighbouring mountain; but no inscription was found on it to reveal its origin.

Port Vathy, though very long, and well sheltered, is too narrow and too deep to be a commodious harbour. The high mountain that rises from its northern shore, contains many of the excavated sepulchres mentioned at Sevedo; and on the elevated neck of land that separates it from the gulf, there are remains of considerable buildings. Amongst others, a theatre, with twenty-six rows of seats; rudely built in comparison with that of Patara, but beautifully placed with its front to the sea, and commanding a view of the little archipelago of islands, that dapple the surface of the bay. In a small temple a tesselated pavement was found, but coarse, and without much design; the squares are about half an inch in diameter, black, white, and red; the two former of which are stone, and the latter brick. In the neighbourhood of these buildings are several circular pits; the stucco on the sides and bottoms is perfect, but the tops or coverings have fallen in; they seem to have been either cisterns for water, or perhaps reservoirs for grain. The shore is here faced with masonry, which appears to have supported a terrace, or avenue, extending about half a mile along the margin of the bay, and connecting the theatre and the other public buildings with the town.

Traces of this town may be observed near a small artificial harbour, formed by one of those ancient piers, the remains of which are so numerous in the Levant.

Groups of sarcophagi surround this place; some plain, others ornamented, and generally bearing inscriptions. These inscriptions, and those on the stone doors of the sepulchres, appear, from the rudeness of their execution, to be very antient. Intermixed with the usual Greek letters, there are several uncommon characters, of which the following are specimens.

A few of these sarcophagi have two chambers, one over the other; perhaps for the purpose of receiving two bodies; or one might have been the Soros, to contain the funeral vessels.

This little port is the landing place for boats from the island of Kastelorizo; there is consequently the usual appendage of a coffee-house, to which, and a few huts, the inhabitants give the name of Antiphilo: the similarity of the names affords a strong presumption that this was the Antiphellus of Strabo."

* An Agha is a magistrate, or governor; his district is called an Aghalik. A petty Agha generally holds his government for a year only, at the expiration of which he is removed to another, if he can purchase it; for every employment in the empire is purchased.

Source: Francis Beaufort, Karamania ( or a brief description of the south coast of Asia-Minor and of the remains of antiquity: with plans, views, etc.; collected during a survey of that coast, under the orders of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, in the years 1811 & 1812), pages 7-16. R. Hunter, London, 1817. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Kastellorizo

history |

John Carne on "Castelorizo" |

|

|

|

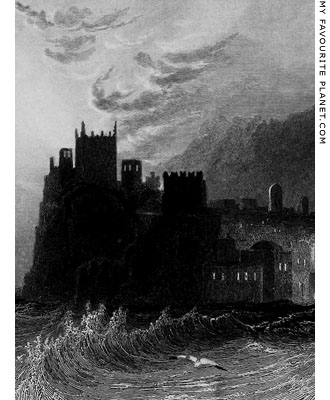

"Castelorizo, near Rhodes", a 19th century steel engraving by Henry Adlard (active 1824-1869),

after a drawing by the English artist and traveller William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854)

Source: John Carne, Syria, The Holy Land, Asia Minor, second series (see details below). |

| |

The Cornish gentleman John Carne (1789-1844) set out from England on 26th March 1821 for Constantinople, and visited Greece, the Levant, Palestine and Egypt. Following his return home a number of books were published about his journey, including two volumes of the letters he wrote along the way and another of recollections of the voyage. [13] Frustratingly for some historians, his letters are not dated, and he did not mention the dates of the events described or stages of his journey. He also wrote short essays as commentaries to prints of scenic views of Greece (Kastellorizo, Rhodes and Syros), Turkey, the Levant and the Holy Land (Palestine) by a number of artists, including Bartlett, William Purser (1785-1856) and Thomas Allom (1804-1872). Syria, The Holy Land, Asia Minor... was published in two volumes, as "first series" and "second series", between 1836 and 1838.

The books are an interesting literary exercise, in that the author provided articles to accompany pre-existing individual images, rather than the more common practice of pictures chosen or commissioned to illustrate text. Most of the images are picturesque depictions of exotic places in the Romantic manner of the 19th century, rather passive landscapes and studies of architecture populated by natives in local costume. The texts provide impressions of the locations with a little geographical, historical and sociological background information. The aim of the works appears to have been to encourage travel to these places, which have "the glory and the brightness of a dream".

"... The sites of empires, awe-inspiring and memorable spots - interesting ruins of temples, tombs, and palaces - these, as they are seen here represented, hold forth no slight inducement to tourists of every class to make them the favourite field of their future wanderings and researches. Compared with every other, it may with truth be said that they impress the mind with all 'the glory and the brightness of a dream'; the sight of them awakens an enthusiasm felt in no other region of the earth; while the general desire to behold them is strengthened by the daily increasing facilities of communication, the various incentives to enterprise held out by science, by commerce, and by the gradual progress of European ideas and civilization, - insomuch that it may almost be averred, that all who read, or write, or travel, like the Artists who first trod this virgin ground, seem to have caught some rays of fresh enthusiasm from the beauty and sacredness of the scenes and recollections brought to mind."

The "Advertisement" (blurb) to the first series (volume 1).

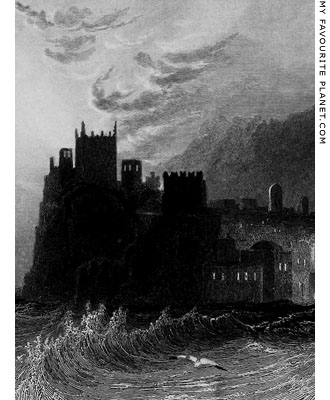

Bartlett's view of Kastellorizo stands out among the other images for its dramatic depiction of the east side of the main harbour, apparently drawn from the sea during a storm. The position of the low sun behind the silhouette of the Knights' Castle indicates it was made in the early morning. The windows of the houses and other buildings are lit from within. The domed building on the waterfront, below and to the right of the castle, is presumably the 18th century Ottoman mosque (see gallery page 163), and the two tall, tower-like buildings directly above it are probably 18th century windmills, one of which is still standing (see gallery page 220). Several boats and ships are moored in the harbour, and in the background the craggy cliffs loom over the scene.

One wonders how the artist managed to capture this scene while standing or sitting on a boat tossed by waves and battered by the wind. Bartlett is known to have used a camera obscura and other devices to make his drawings, and to have prepared sepia-wash drawings especially for the engraver, at the same size as the finished print. One suspects a bit of arty trickery here: he may well have completed the work later specifically for publication, from a combination of memory and preparatory sketches, at least some of which perhaps made during calmer weather. He has certainly played with the perspective to make the castle and the cliffs appear loftier and more imposing. Compare it with photos of the same scene on gallery pages 17-21.

In the introduction to the first series, Carne wrote that "most of the places illustrated in this work had been visited by the writer...". Neither in his Letters nor the Recollections did he mention a visit to Kastellorizo, however, his description of the island is so detailed that it appears to be a genuine first-hand account. It is likely that he stopped here on his return sea voyage, between Cyprus and Rhodes, described in Volume 2 of his Letters.

Castelorizo, near Rhodes

"There is perhaps no navigation in the world so beautiful, varied, and ever-changing, as that of the Grecian archipelago. In his own hired bark, the traveller departs at sunrise from some favourite isle, where he has lingered a few days, and sees afar off in the horizon the hills and cliffs where he is to halt at the close of day; and on the right and left, as he cruises along with a fine breeze and brilliant atmosphere, are other isles, of wild or fantastic form, which tempt him sometimes to tarry, and try the hospitality of their homes, the flavour of their wines, the beauty of their scenery. The sea is sometimes peopled with the isles, and you pass slowly among them; and at sunset such a passage is delightful: the boats of the fishermen on the wave - their hamlets on the beach - the convent on the cliff.

The singular island and town of Castelorizo are situated not far from Macri, on the coast of Asia Minor: their appearance from the sea is wild and witch-like. The island is very arid and barren; an immense rock of a dull red hue, relieved by the blanched tints of some lighter cliffs, by a few olive gardens, and a little stunted vegetation: the latter generally surround a villa, of which even the red isle is not wholly destitute. Most of the provisions are brought from the continent of Asia Minor, and it is rather puzzling to divine whence, for it appears nearly as barren as the island itself.

Several vessels were on the stocks in the port. The servant landed, but could not contrive to bring off a loaf of bread. In stormy weather, when the wind is full on the opposite shore for a long time together, the inhabitants must suffer from scarcity. The vintage song, the shepherd's pipe, the sound of the wind in the grove, is not heard here, only the breakers' dash on the rocky beach. All around the island is what may be called a sponge-diving, which is the occupation of a great number of divers, who may be seen plunging from the rocks into the sea in quest of sponges, in which there is a considerable trade: they are sent to Rhodes and Smyrna.

The aspect of the town is poor; it is thinly peopled; the local attachment must be strong that can bind the islanders to their rock. Castelorizo would be a sea-beat dungeon to the traveller, who should be compelled by adverse weather to spend a few weeks there. Coffee may be had; but fruit, wine, bread, such as may enter civilized lips, fresh meat - all these are apocryphal luxuries: in an auspicious moment these may possibly be found, but rare indeed is their sojourn in the red isle. In some of the steepest streets, steps are cut out of the rock for an easier ascent; the streets are very narrow and winding, cleansed by the rains, that sweep down the rocky pavement all uncleanly and offensive things.

A castle, partly ruinous, stands on the summit of the cliff, several hundred feet above the sea: it was built by the Genoese; its massive walls and battlements have long been almost useless, though the Greeks, once more a nation, will probably put them again into a state of defence, for the isle might be made a strong fortified position.

The bold island-bearing of the Greeks is not visible among these people, who have more the air of captives; the consciousness of poverty and discomfort is in their look: the faces of the women look hard and sea-beat; there may be gentler and lovelier faces even in Castelorizo, but they were not visible in the streets. At noon-day, when the latter were deserted, and the inhabitants enjoying their siesta within doors, or in the shade of their houses, the place looked like a city of the dead, the feet of the traveller and his companions being almost the only ones heard on the precipitous streets.

A walk of an hour along the cliffs leads to the site of the ancient city, on one of the loftiest parts of the isle. The view from the summit of the hill was splendid; beneath lay the barren, rocky isle, with scarcely a tree to relieve its fierce cliffs, and beyond it the broad expanse of the Adalian gulf with its countless isles; and on either side were the mountain shores of Caramania. Of the ancient city, the circuit of the walls can still be traced, about two-thirds of a mile in circumference: a few cisterns and reservoirs yet remain, as well as numerous traces of the industry of the former people, in the steps cut on all sides to lead from one steep to another."

Source: John Carne, Syria, The Holy Land, Asia Minor, etc. Illustrated. In a series of views, drawn from nature by W. H. Bartlett, William Purser, etc, Second series (Volume 2), pages 58-59. Fisher, Son & Co., London, 1836-1838. At the Internet Archive. |

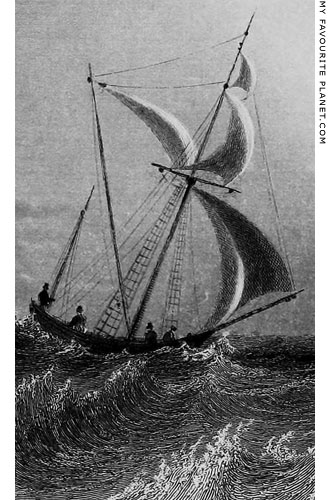

Four men in a boat, a detail from Bartlett's

view of Kastellorizo harbour. They all wear

top hats and appear to be wearing European

clothing, and are perhaps his travelling

companions or ship's officers. |

| |

The Knights' Castle of Kastellorizo, given

the gloomy Gothic look in Bartlett's drawing. |

| |

| |

Kastellorizo

history |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Strabo on Kastellorizo

Strabo (Στράβων, Strabon; 64/63 BC – circa 24 AD), Greek geographer, philosopher and historian from Amaseia in Pontus (today Amasya, Turkey). He described the western coast of Lycia from Xanthus southwards to Antiphellos (today Kaş):

"Next is the river Xanthus, formerly called Sirbis. In sailing up it in vessels which ply as tenders, to the distance of 10 stadia, we come to the Letoum, and proceeding 60 stadia beyond the temple, we find the city of the Xanthians, the largest in Lycia. After the Xanthus follows Patara, which is also a large city with a harbour, and containing a temple of Apollo. Its founder was Patarus. When Ptolemy Philadelphus repaired it, he called it the Lycian Arsinoe, but the old name prevailed.

Next is Myra, at the distance of 20 stadia from the sea, situated upon a lofty hill; then the mouth of the river Limyrus, and on ascending from it by land 20 stadia, we come to the small town Limyra. In the intervening distance along the coast above mentioned are many small islands and harbours. The most considerable of the islands is Cisthene, on which is a city of the same name. In the interior are the strongholds Phellus, Antiphellus and Chimaera, which I mentioned above.

Then follow the Sacred Promontory [Cape Chelidonia, elsewhere translated as 'the promontory Hiera'] and the Chelidoniae, three rocky islands, equal in size, and distant from each other about 5, and from the land 6 stadia. One of them has an anchorage for vessels. According to the opinion of many writers, the Taurus begins here, because the summit is lofty, and extends from the Pisidian mountains situated above Pamphylia, and because the islands lying in front exhibit a remarkable figure in the sea, like a skirt of a mountain."

H. C. Hamilton and W. F. Falconer (translators), The Geography of Strabo, Volume III (of 3), Book 14, chapter 3, sections 6-8. George Bell & Sons, London, 1903. At Perseus Digital Library.

The passage has been translated by others in different ways, including: "Among others is Megiste an island, and a city of the same name, and Cisthene". In all the Greek manuscripts it appears:

"ὧν καὶ μεγίστη νῆσος καὶ παὶ πόλις ὁμώνυμος, ἡ κισθήνη."

See also another translation: H. L. Jones (translator), The Geography of Strabo, Book 14, chapter 3, sections 6-8. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and William Heinemann, Ltd., London, 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

2. Leake on Kisthene

The suggestion that Megiste may have been known in earlier times as Kisthene was first made by the British antiquarian and topographer William Martin Leake (1777-1860).

See:

William Martin Leake, Journal of a tour in Asia Minor, pages 183-184. John Murray, London, 1824. At the Internet Archive.

John Anthony Cramer, A geographical and historical description of Asia Minor, Volume 2, page 251. Oxford University Press, 1832.

3. Aischylos on Kisthene

Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound, lines 780-818, translated by Herbert Weir Smyth. Harvard University Press. 1926. At Perseus Digital Library.

There was another city named Kisthene on the coast of Mysia, northwest of Pergamon. See:

Strabo, Geography, Book 13, chapter 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

See the quote from the play and discussion on the home of the Gorgons

in Medusa part 1, in the MFP People section.

4. Cockerell on Megiste

The inscription discovered by Cockerell was published by Leake in Journal of a tour in Asia Minor, pages 183-184 [see note 2 above].

ΣΩΣIKΛHΣ NIKAPOTA

ΣAMIOΣ EΠIΣTATHΣAΣ

EN TE KAΣTABI KAI EΠI

TOΥ ΠIPΓOΥ TOΥ EN ME

-ΓIΣTAI EPMAI ΠPOΠΥ

-ΛAIΩI XAPIΣTHPION

The inscription can still be seen on a natural rock outcrop below the Castle of the Knights of Saint John. It has not been dated, but is thought to be from the 4th-3rd century BC, when Megisti was part of the Rhodian Peraia.

According to Leake's rendering it is a dedication to Hermes Propylaios at a tower on Megisti by Sosikles Nikatora of Samos. A later interpretation gives the dedicator as Sosikles Nikagoras of Amos (Σωσικλῆς Νικαγόρα{ς} Ἄμιος), epistates in Kastabos and Megista. Amos (Ἄμος) was a coastal settlement of the Rhodian Peraia in Caria (near the modern town of Turunç, Turkey).

Σωσικλῆς Νικαγόρα{ς}

Ἄμιος ἐπιστατήσας

ἔν τε Καστάβ<ω>ι καὶ

ἐπὶ τοῦ πύργου τοῦ ἐν Με-

γίσται, Ἑρμᾶι προπυ-

λαίωι χαριστήριον

See: Rhodian Peraia 58. At epigraphy.packhum.org (the Packard Humanities Institute), which provides the following references: CIG 4301; LW 1268; Holleaux, BCH 18, 1894, 390-395; van Gelder, Mnemosyne 24, 1896, 249, no. 29; *SGDI 4332; van Gelder, Geschichte 446, no. 32a.

Cockerell's own brief account of his visit to Kastellorizo appears in:

Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810-1817: the Journal of C. R. Cockerell, R. A., edited by his son Samuel Pepys Cockerell, pages 164-165. Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1903. At the Internet Archive.

5. Livy on Megiste

In his The History of Rome (Ab Urbe Condita Libri, Books from the Foundation of the City, written 27-9 BC), Titus Livius (64 or 59 BC - 17 AD) described events of the Roman-Seleucid War (192-188 BC) between Rome, allied with Eumenes II of Pergamon, and Antiochus III the Great, ruler of the Seleucid Empire. Various manoeuvres on land and sea eventually led to the defeat of Antiochus at the Battle of Magnesia, fought near Magnesia ad Sipylum (today Manisa, Turkey) in 190 BC.

"It was then resolved that Eumenes should return home, and make every necessary preparation for the passage of the consul and his army over the Hellespont; and that the Roman and Rhodian fleets should sail back to Samos, and remain stationed there, that Polyxenidas might not make any movement from Ephesus. The king returned to Elaea, the Romans and Rhodians to Samos.

There, Marcus Aemilius, brother of the praetor, died. After his obsequies were performed, the Rhodians sailed, with thirteen of their own ships, one Coan, and one Cnidian quinquereme, to Rhodes, in order that they might take up a position there, against a fleet which was reported to be coming from Syria.

Two days before the arrival of Eudamus and the fleet from Samos, another fleet of thirteen ships, under the command of Pamphilidas, had been sent out against the same Syrian fleet; and taking with them four ships, which had been left to protect Caria, they relieved from blockade Daedala, and several other fortresses of Peraea, which the king's troops were besieging.

It was determined that Eudamus should put to sea directly, and an addition of six undecked ships was made to his fleet. He accordingly set sail; and using all possible expedition, overtook the first squadron at a port called Megiste, from whence they proceeded in one body to Phaselis, resolving to wait there for the enemy."

William A. McDevitte (translator), Titus Livius, The history of Rome, Book 37, chapter 22. Henry G. Bohn, London, 1850. At Perseus Digital Library.

6. Pliny on "Megista" and other islands of Lycia

Pliny mentioned Megista among a long list of islands off the Lycian coast, proceeding westwards along the south coast (from Cyprus, Cilicia and Pamphylia), then northwards along the west coast. However, the order of islands listed appears confused, and does follow modern identifications. For example, "Strongyle", probably the island today called Stroggyli Kastellorizou (see gallery page 10) is mentioned in a separate group from Megista. Several islands have still not been identified with certainty.

"In the Lycian Sea are the islands of Illyris, Telendos, and Attelebussa, the three barren isles called Cypriae, and Dionysia, formerly called Caretha. Opposite to the Promontory of Taurus are the Chelidoniae, as many in number, and extremely dangerous to mariners. Further on we find Leucolla with its town, the Pactyae, Lasia, Nymphäis, Macris, and Megista, the city on which last no longer exists.

After these there are many that are not worthy of notice. Opposite, however, to Cape Chimaera is Dolichiste, Choerogylion, Crambussa, Rhoge, Enagora, eight miles in circumference, the two islands of Daedala, the three of Crya, Strongyle, and over against Sidyma the isle of Antiochus. Towards the mouth of the river Glaucus, there are Lagussa, Macris, Didymae Helbo, Scope, Aspis, Telandria, the town of which no longer exists, and, in the vicinity of Caunus, Rhodussa."

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book 5, chapter 35. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Kastellorizo in Medieval sea charts

All the names above are marked or mentioned in "Portolane", Medieval sea charts and navigational instructions.

See, for example: Konrad Kretschmer, Die italienischen Portolane des Mittelalters: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kartographie und Nautik, particularly page 666. Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Meereskunde und des Geographischen Instituts an der Universität Berlin, Heft 13, Februar 1909. Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, Berlin, 1909. At Harvard Library.

8. Richard Pococke on "Castello Rosso"

After visiting Syria, the Holy Land and Egypt, the English clergyman Richard Pococke (1704-1765) sailed from Alexandria on 2nd July 1739 on his way to Chania, Crete (Candia). On 8th July his ship sailed along the southern Lycian coast and passed "Satalia" (Antalya, ancient Attalia, founded by Attalus II of Pergamon), and on the evening of the same day they arrived at Kastellorizo. It seems that the ship did not stop there, since Pococke wrote only that "we came up with the island called Castello Rosso". He did not say who told him that the island had a good water supply and was often attacked by the Maltese, but his informants may have been the crew or other passengers on the ship.

He believed Kastellorizo to be "one of the Chelidonian islands" mentioned by Strabo. However, Strabo lists the Chelidoniai (Χελιδόνιαι, Swallows) further south and east along the Lycian coast (see note above). Today they are thought to be the row of five conical rocks known as Beş Adalar (Turkish, Five Islands) opposite Gelidonya Burnu (Cape Gelidonya, also known as Taşlık Burnu), southeast of Kastellorizo, although both Strabo and Pliny wrote that there were only three islands. Pococke also thought that Kastellorizo may have been the "Rhoge" mentioned by Pliny (see note above). He was evidently unaware of the island's Greek name Megiste (also mentioned by Pliny), and one wonders whether at the time anybody on the island itself or elsewhere knew its ancient name.

"On the second of July one thousand seven hundred and thirty nine I embarked at Alexandria, on board a Scotch vessel bound to Tunis, Algiers, and some other places on the coast of Africa, freighted with Moors on their return from Mecca; I was to be landed at Canea in Candia, if the wind would permit.

On the eighth we saw that part of the coast of Caramania, which by the antients was called Pamphylia, and were almost opposite to Satalia, which was the antient Attalia, and was south of Perga in Pamphylia. Here the apostles Barnabas and Paul embarked for Antioch after the persecutions they had met with at Iconium [Acts, 25, 26].

In the evening we came up with the island called Castello Rosso: This was, without doubt, one of the Chelidonian islands, which Strabo mentions as opposite to the sacred promontory where mount Taurus was supposed to begin [Strabo, Book 14, chapter 2]; and it may be that island which he says, had a road for ships, and probably it is the island Rhoge of Pliny [Pliny Book 5, chapter 35], and the present name may be a corruption from it, as I could see no reason for their calling it the red island; it is high and rocky, and about two miles in length. There is a town and castle on the highest part of it, and the south side of this island seemed to be covered with vineyards; there is a secure harbour to the north, and they told me that it was not above half a mile from the continent, and that they have plenty of good water; it is inhabited by Greeks, and is a great resort for the Maltese, as there is no strong place to oppose them.

Proceeding on our voyage I saw two small islands at a considerable distance, which, if I mistake not, are called Polieti, and seem to be those rocks, which are marked in the sea chart, and in the map I give of Asia minor [see above].

We were now opposite to Lycia ; a little to the north west of these islands the river Lymira probably falls into the sea ; near it was the city Myra of Lycia, to which St. Paul came in his voyage from Caesarea to Italy, and embarked on board a ship of Alexandria bound to that country [Acts, 27, 5]. Further to the west the river Xanthus falls into the sea; Patara was situated to the east of it, where St. Paul embarked on board a ship bound for Phoenicia, in his voyage from Miletus to Tyre [Acts, 21, 1, 2]."

Richard Pococke, A Description of the East and some other countries, Volume 2, Part I, Observations on Palaestine or the Holy Land, Syria, Mesopotamia, Cyprus, and Candia, Book IV, chapter I, pages 236-237. Printed for the author by W. Bowyer, London, 1745. At the Internet Archive.

9. George Scharf in Lycia

George Scharf's personal journals of his visits to Lycia, written in small pocket notebooks, February-May 1840 and October 1843 - March 1844, contain a few small sketches. The journals and other drawings by Scharf are now in the British Museum.

See: F. W. Hasluck, Notes on manuscripts in the British Museum relating to Levant geography and travel, in: The Annual of the British School at Athens, Volume 12 (1905/1906), pages 196-215, Add. 36,488, A-C, page 214. At the Internet Archive.

10. Francis Beaufort and HMS Frederikssteen

Irish born Francis Beaufort, largely self educated, had a great interest in the sciences, including physical geography, mathematics and astronomy. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society, was a council member of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and a founder of the Royal Geographical Society. Following his successful surveying and charting expeditions (including South America and South Africa) he was appointed as the British Admiralty Hydrographer of the Navy in 1829. He reached the rank of rear admiral and in 1848 was knighted, becoming a KCB (Knight Commander of the Bath).

Among his several achievements was his development of the scale of wind strength, later named the Beaufort Scale of wind force, based on a simpler scale created by the civil engineer John Smeaton (1724-1792), and first considered as an aid to mariners by Alexander Dalrymple (1737-1808), the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty (Beaufort's predecessor). Beaufort noted his progressive refinements of the scale in his journals from 1806. He began encouraging its use, particularly after himself becoming Hydrographer of the Navy, and it was adopted by the Admiralty from 1838. The British meteorological service started referring to its version of the system as the Beaufort Scale in 1906.

He also trained Robert FitzRoy, who became commander of the survey ship HMS Beagle, and invited Charles Darwin to take part in the ship's second voyage in 1831.

Beaufort's surveying mission around the Lycian coast came to a sudden end when on 20 June 1812 his boat was attacked by an armed mob at Ayas (near Adana), and he was seriously wounded by a musket ball through his upper leg and hip. Mr. Olphert, a young man midshipman on another boat, was killed during the attack (Karamania, pages 289-291).

The Frederikssteen (also referred to as Friderichssteen, Frederichsteen, Fredericksteen, Frederickstein, etc), a fifth-rate frigate, was originally a Danish ship, launched in 1800, and surrendered to the British, along with most of the Danish fleet, following the Battle of Copenhagen on 7 September 1807. At the end of his account of his Lycian survey (Karamania, page 294) Beaufort remarked that the ship was in a bad shape, and after sailing with a convoy from Malta to England it was sold off and scrapped in 1813.

11. "cwt." = a British hundredweight

1 cwt. (hundredweight) = 112 lb (pounds) = 50.80 kg (kilograms)

12. Sevedo and Vathy harbours

Port Sevedo is today the main harbour of the Turkish resort town Kaş (ancient Antiphellos), and Vathy is the long, narrow harbour to its west, used by private boats.

13. John Carne

John Carne studied at Cambridge University but did not stay to complete his degree. He was also ordained as a church deacon, but only served as a clergyman for a few short stints. As the son of a wealthy merchant and banker, he appears never to have felt the need to pursue a career, and an obituary described him as being "removed by circumstances above the necessity of choosing a profession". However, a volume of poetry, published in 1820, and his travel books earned him a reputation as an author. He went on to write other books and articles, and became a member of literary and intellectual circles in London and Paris. His friends included Sir Walter Scott.

See:

Obituaries, June 1844, in: The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume XXI, January-June 1844, pages 656-657. William Pickering, John Bowyer Nichols and son, London, 1844.

The series Letters from the East was first published 1824-1826 in the New Monthly Magazine, and then republished in two volumes, including a section on Greece. Despite not providing dates, Carne's section on Greece is of interest due to his mentions of events and conditions there at the start of the Greek War of Independence.

John Carne, Letters from the East: written during a recent tour through Turkey, Egypt, Arabia, the Holy Land, Syria, and Greece, in two volumes. Henry Colburn, London, 1826.

John Carne, Recollections of Travels in the East: Forming a Continuation of the Letters from the East. Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, London, 1830. |

|

|

Maps, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this

website. However, we can take no responsibility for

inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services

mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2023 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |