|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Medusa > part 2 |

|

back |

Medusa – part 2 |

|

Page 2 of 8 |

|

|

| |

Early depictions of Gorgons

7th - 6th century BC, Archaic period |

| |

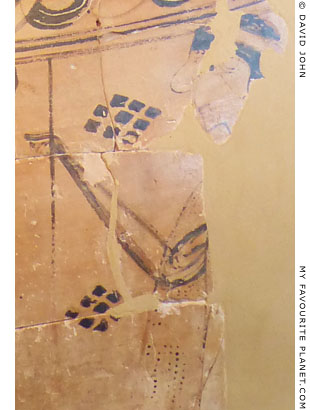

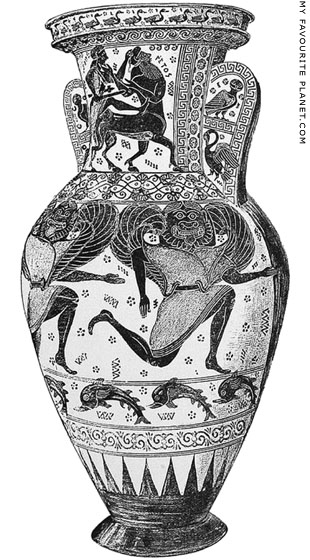

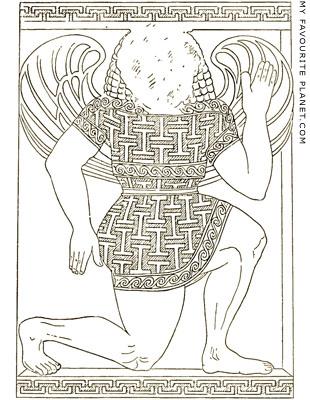

A drawing of a relief depicting Perseus decapitating Medusa on the neck of an Archaic

Cycladic terracotta pithos (amphora) found in 1897 in Thebes, Boeotia, central Greece.

Around 700-660 BC. The earliest known extant depiction of a Gorgon. Height 23 cm.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. CA 795.

Although it is not evident from this drawing, the technique used to depict the figures is

the same as used, for example, on the "Mykonos Vase", a large Cycladic pithos made

around the same time, decorated with scenes of the Trojan horse and the sack of Troy.

Image source: A. L. Frothingham, Medusa, Apollo, and the Great Mother.

In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 15, No. 3 (July - September 1911),

pages 349-377, Fig. 12. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

(See the note in Medusa part 3.) |

| |

The earliest depictions

of the Gorgon myth

Pausanias wrote that near the theatre in Argos stood a stone head of Medusa (somewhat ironic that the Gorgon's head was turned to stone), believed to have been made by the Cyclopes (Κύκλωπες, Kyklopes), a primordial race of giants (see Homer part 3), who served the gods as builders, blacksmiths and craftsmen.

"Beside the sanctuary of Cephisus is a head of Medusa made of stone, which is said to be another of the works of the Cyclopes."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 20, section 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

He also mentioned local legends in the Peloponnese that the Cyclopes had built the massive walls of the Mycenaean cities Mycenae and Tyrins (Book 2, chapter 16, section 5; 2,25,8; 7,25,6; see also the "Cyclopean walls" of the Athens Acropolis), and that at Isthmia there was "an ancient sanctuary called the altar of the Cyclopes, and they sacrifice to the Cyclopes upon it" (Book 2, chapter 2, section 1). Large and crudely made works ascribed to the Cyclopes were considered extremely ancient. Unfortunately, he did not describe the head, so we do not know whether it actually depicted Medusa, or was merely believed to do so, perhaps because it was monstrous.

1) The earliest known extant depiction of a Gorgon is a relief on a Cycladic terracotta pithos (amphora) found in 1897 in Thebes, Boeotia, dated to around 700-660 BC, decorated with an incised and stamped relief depicting Perseus killing Medusa (see drawing at the top of the page).

Medusa is shown as a female centaur: naked, in human form to the waist; the body and hind legs of a horse project behind her, below the waist. Her midriff and front legs appear to be covered by a belted skirt which covers the feet (perhaps a solution to the problem of whether to show the front feet as human or equine). Her head and upper body face frontally, the equine part is shown in profile. A long hair braid hangs from either side of her triangular head. She has large round eyes and sharp, triangular teeth. She also has very long, slim fingers, and both figures look undernourished.

The depiction of Medusa as a centaur may have been due to an association with the story of her sexual relationship with Poseidon, who was also worshipped as Hippios (Ἵππιος), "tamer of horses". According to one myth he mated with a creature who consequently gave birth to the first horse. Pegasus, who sprang from the body or blood of the slain Medusa, was considered by some mythographers to be her child from Poseidon.

Perseus, also with large round eyes and long braids, stands in profile to her left. He wears Hades' cap which makes him invisible, a short chiton and Hermes' winged boots. A scabbard is slung on his back, and from a long strap around his right shoulder hangs the kibisis (κίβισις), the pouch he has taken from the Nymphs to contain Medusa's head. With his left hand he grasps one of Medusa's braids, and with the other he is cutting through her throat with his sword. His head is turned backwards so that he can avoid her deadly glare.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. CA 795 (not on display). Height of amphora 130 cm.

2) A fragment of another amphora from Thebes, also dated to around circa 670 BC, has part of a similar relief showing Perseus in the same way.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. CA 937.

See also an Archaic Corinthian vase in the form of Medusa riding Pegasus below.

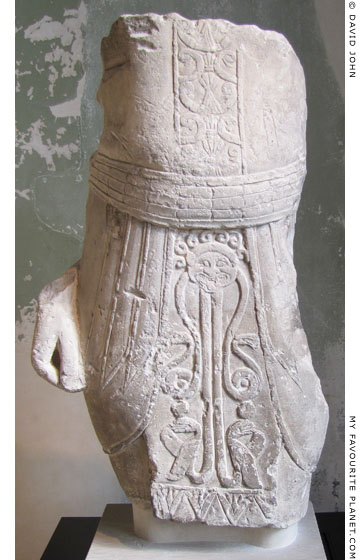

3) Bronze fragments of a large hammered ring (originally a disc), diameter 77 cm, surrounding a cut-out, shallow sheet relief figure of a Gorgon. From the Athens Acropolis, mid 7th century BC. Thought to be an akroterion (roof decoration) from the pediment of a small temple on the Acropolis, perhaps the first temple of Athena Polias, a predecessor of the Erechtheion. This is the earliest known depiction of a Gorgon from the Aropolis.

The remains of the frontal Gorgon figure appear to be of very primitive workmanship, although it is difficult to imagine how it looked when it was complete, with other attachments and probably coloured. The large head sits directly on the remains of the wings; the inner edges of their bases touch on the breast. A long chiton reaches to just above the ankles, revealing feet which are also shown frontally. The garment is drawn at the waist, suggesting it was girdled.

A bow-shaped ridge at the top of the head marks her hairline. The eyebrows, formed by another ridge like a simple drawing of the outline of a flying bird, appears to be attached (i.e. continues on the same raised plane) to a broad flaring nose. The eyes are glaring but unremarkable. The rectangular mouth has rows of square teeth, fangs at each end and a tongue hanging above a squarish cleft chin. It looks like an early attempt at the lion-mask form.

It has been suggested that the figure represents "Potnia Theron", the Mistress of Animals (as on the plate from Kamiros, Rhodes below), and perhaps held a lion with each hand.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 13050. (Formerly in the National Archaelogical Museum, Athens.) |

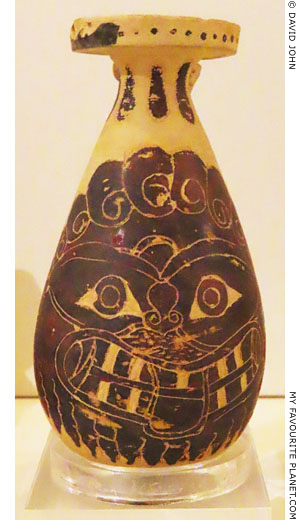

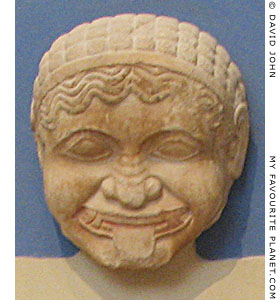

A Gorgoneion on a Corinthian Alabastron.

About 600 BC. Provenance unknown.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 16289. |

| |

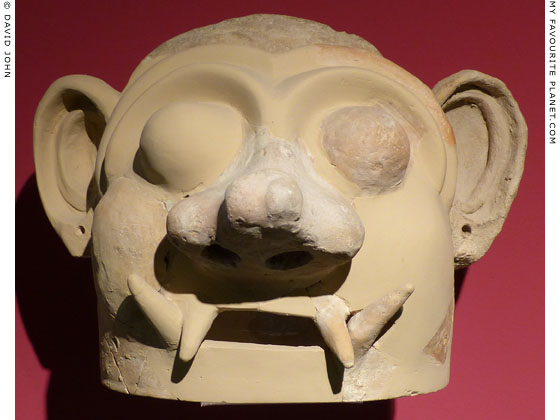

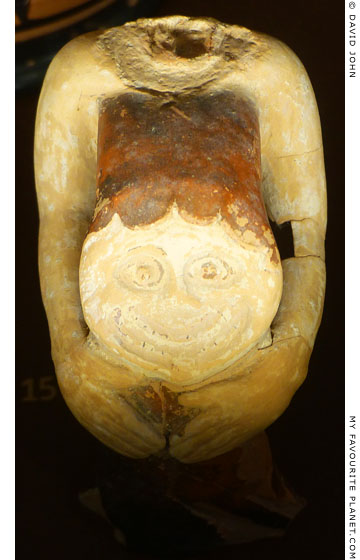

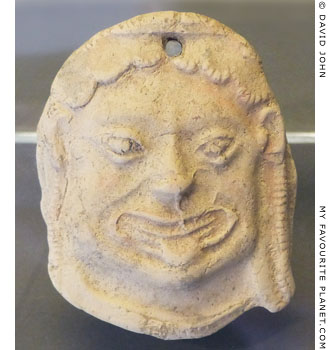

Fragment of a terracotta Gorgon head from

Megara Hyblaea, Sicily. 6th century BC.

Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum,

Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 2010. |

| |

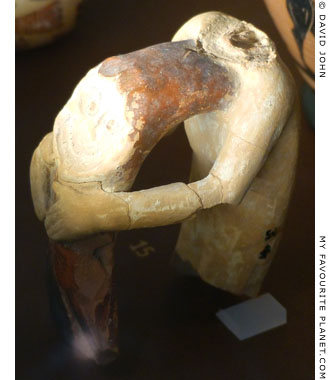

Flying Gorgon pendant from Agrigento,

Sicily. Second half of the 6th century BC.

Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum,

Syracuse, Sicily. |

| |

4) A fragment of an ivory relief from the sanctuary of Hera on Samos, dated to the fourth quarter of the 7th century BC, also shows Perseus killing Medusa. The quality of the carving is superb.

Perseus, with his hair in long braids, faces frontally. He wears a conical cap or helmet, a short chiton, belted at the waist, and a strap passing diagonally from his right shoulder, across his chest to the waist. With his left hand he grasps Medusa's enormous head, and with his right hand he decapitates her with a sword. The frontal head is in the form of the lion-mask, which must be one of the earliest of this type. Her huge winged body can be seen falling behind the head. The head, arm and hand of another figure can be seen on the left of Perseus. This is probably Athena encouraging the hero.

Samos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. E1.

5) Fragments of a small, rectangular ivory relief from Sparta, circa 630-620 BC, showing Perseus decapitating Medusa in a similar way ( see illustration below).

6) A bronze shield band (ochana) from Olympia, circa 560 BC, shows Athena taking an active part in killing the Gorgon. Winged Medusa, in a frontal kneeling/fleeing position, has four snakes rising from her head. Perseus on the left, and Athena on the right (both in profile), each grasp one of the snakes with their left hands. Athena appears to be holding on to Medusa's neck with her right hand. Perseus is looking away from Medusa and about to decapitate her with the sword in his right hand. He wears a cap and a short, belted chiton with a diagonal shoulder strap, but is naked below the waist. All three figures are barefooted.

Medusa wears a short, belted chiton, and her straight wings are lowered. With her bent left arm she reaches up to her right shoulder, perhaps about to defend herself from Perseus' sword. Her right hand appears to be grasping the under side of her left thigh. Her head is shown as a variant of the lion-mask.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. B 975. |

|

|

| |

A terracotta ceremonial mask from the "Bothros" of the Upper Citadel

of Tiryns, in the Argolid, Peloponnese. Late 8th - early 7th century BC.

Nafplion Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4789.

|

One of four similar masks on display in the Archaeological Museum of Nafplion (see photo below; the other three are numbered 4790, 4791 and 9095), they are all badly damaged and have been restored. Five masks were discovered in a pit in the Upper Citadel of the ancient fortified city of Tiryns (Τίρυνς), which had been an important political and cultural centre during the Mycenaean period. The area of the citadel is thought to have been a sanctuary of Hera, and the pit perhaps a bothros (βόθρος), used in sacrificial rituals.

Some scholars believe that the ugly, boar-toothed creatures may be early depictions of the Gorgon's head. Tiryns is one of the Argolid cities associated with the myths of Perseus and Medusa. If these masks were actually worn, they would have covered the entire head, but there are no incisions in the eyes and the wearer would have been "blind". The masks have pierced ears for earrings, identifying them as female.

The Tiryns masks have been compared to terracotta masks of the 7th - 6th century BC discovered in the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, Sparta (see below). According to various theories, the masks were associated with rituals of initiation or coming of age. However, the Spartan masks are very different in form and design.

The artefacts found in the "Bothros" include painted terracotta shields with some of the earliest narrative depictions of mythological scenes in Greek art (see Homer part 2). |

|

|

| |

The four terracotta masks from Tiryns displayed in Nafplion Archaeological Museum. |

| |

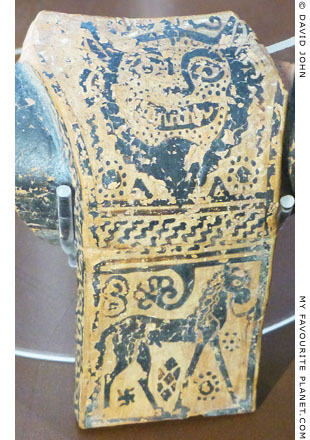

A fragment of a ceramic tripod cauldron (lebes) with a Gorgoneion

on a panel (referred to as a metope) at the top of one of the legs.

First half of the 7th century BC. From the sanctuary

of Herakles, Thebes, Boeotia, central Greece.

Thebes Archaeological Museum.

|

An early type of Gorgoneion, rather than the "lion mask" type that was to become more or less standard around the Greek world from the 6th century BC. The painting on this fragment is on a white background, with the skin of the Gorgon's face in brown, and other details in black.

She has high, pointed ears with earrings, a top knot from which wavy locks, perhaps schematically representing snakes, extend horizontally to either side, and a long, bushy beard around the jaw, ending in a point below the chin. The eyebrows and nose are painted with a single deft contour, and the wide-open eyes have large round dots for pupils. Her grimacing mouth has lips painted with a thick outline, and five widely-spaced, oblong teeth, three above and two below. She appears quite jolly, in a rather manic Halloween way.

Another surviving fragment of a tripod cauldron leg (see photo, right) is displayed in the museum as if it is from the same vessel, but although the Gorgoneion is of the same type, both the painting technique and the drawing style are quite different. The decoration, in black only, appears to have been painted directly on the bare clay. The face is covered with black dots, and the teeth are indicated by several long, tapering brushstrokes. On the lower panel is a depiction of a tethered stallion. The paint seems to have been applied more thickly, forming a slight relief, particuarly evident on the top panel frame.

The museum labelling does not mention where many of the ceramics on display were made, but presumably this is locally produced Boeotian ware. As with many Greek painted vases of this period, spaces around the figures have been filled with plant and geometric motifs, which may have had particular significance to artist and viewer, or were merely decorative. The style may appear crude, but it is certainly lively and engaging: confident, vivid and effective graphic art.

The remains of the Theban sanctuary of Herakles can be viewed in a fenced area along Amphionas Street, near the site of the Elektrai Gates, in the southwest of the modern town. The free booklet Cultural walks in Thebes (Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia, Thebes 2017) includes photos, information and a map marking historical sites. Greek and English versions are usually available at the impressive new archaeological museum and from some hotels. |

|

Another surviving leg of a ceramic tripod

cauldron in the Thebes Archaeological

Museum, with painted panels containing

a Gorgoneion and a tethered stallion. |

|

| |

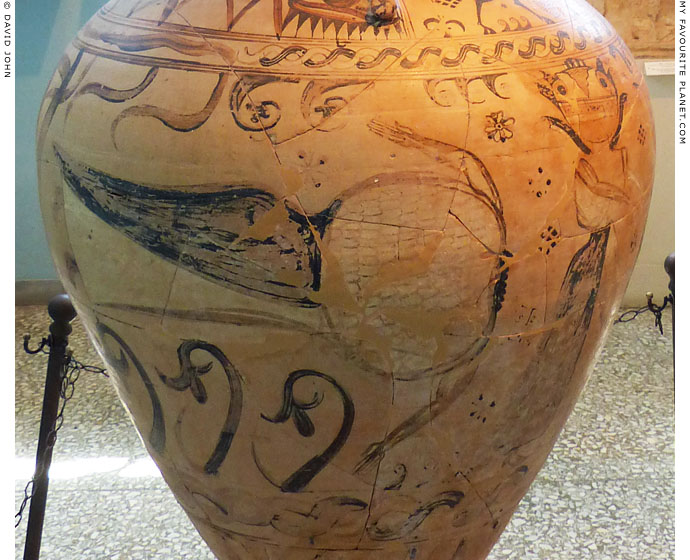

Gorgons on the body of the "Eleusis Amphora", a large Proto-Attic amphora.

Around 660 BC. Excavated in 1954 in the West Cemetery, Eleusis. Pot Burial Γ6.

It had been used as a funeral urn and contained the skeleton of a 12 year old boy.

It is the name vase of the Polyphemos Painter. Height 1.42 m.

Gorgon scene height 52 cm, width 175 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2630.

|

The amphora was discovered in 1954, during excavations at Eleusis led by Greek archaeologist George E. Mylonas (see the note in Demeter and Persephone part 1), among prehistoric burials in soil only 25-30 cm below the modern level. It is thought that the amphora had been damaged and many parts dragged away during centuries of ploughing.

Medusa's sisters, Stheno (mighty) and Euryale (far-springer), are shown with grotesque oval, mask-like heads, enormous eyes, turned vertically, and wide slits of mouths with teeth like spikes. Snakes writhe on either side of their heads and necks, and the Gorgon on the left has griffin heads growing from the top of her head. The shape of their heads and the griffin and snake decorations have led sholars to compare them to the forms of bronze cauldrons used in sacrificial rituals (see photo, below right). Notably, they are not shown with wings.

On the upper garment of the Gorgon on the right are traces of a scaly pattern. In contrast to the hideous heads, the bodies and poses of the sisters appear relatively graceful. Their twig-like arms and ill-defined hands are stretched out in front of them. They wear split skirts from which their surprisingly shapely left legs protrude (as in the plate from Kamiros below). They appear to be running to the right; although, according to the myth, they pursue Perseus after he has killed Medusa, the poses suggest that they are fleeing or even dancing.

Their way is blocked by Athena to the right (see photo, right). Only part of her head, her arm holding a spear or staff, part of her long garment and her feet and ankles peeping from below it, are preserved.

On the other side of the vase, to the left of this scene, Medusa's decapitated and bloated corpse lies or floats horizontally (see photo below). The part of the amphora showing her head has not been preserved, and only the black legs of Perseus can now be seen.

These are among the earliest depictions of figures clearly identifiable as Gorgons, and of the myth of Perseus killing Medusa (see article at the top of the page). It is thought to be an original composition of the painter, and may have been an illustration of oral traditions or even a written version of the myth: Hesiod's poem Theogony [see the note in Medusa part 1] may have been in circulation by this time. At 52 cm high, they are the largest figures yet found on an ancient Greek vase. The depiction of Athena is also one of the earliest in Attic art.

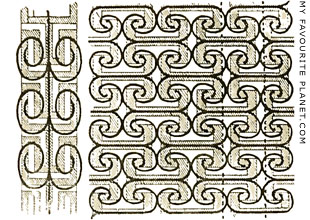

The neck of the amphora shows Odysseus blinding the Cyclops Polyphemos (an article with a photo of the entire amphora on the Homer page). The amphora also features a lion confronting a boar on the shoulder, large intertwining "snakes" formalized as cable patterns, numerous space-filling, orientalizing abstract and floral motifs, and "fretwork" handles. |

Athena on the "Eleusis Amphora".

She holds a spear or staff indicated

by a simple brushstroke. |

| |

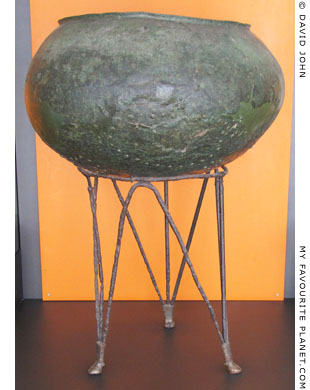

A bronze cauldron on a tripod (from another

cauldron) of iron rods. This type of cauldron

was first made in Greece in the 7th century

BC. The rims were often decorated with

attached heads of griffins and sirens.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

Medusa's decapitated and bloated body on the "Eleusis Amphora". |

| |

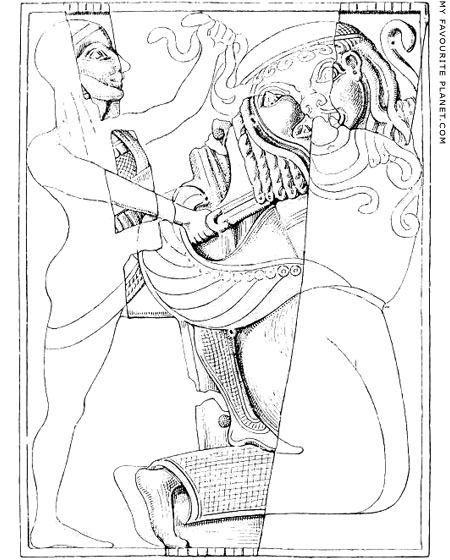

Reconstruction drawing of a fragmentary Laconian ivory plaque

with a carving depicting Perseus decapitating Medusa with a sword.

One of the earliest known representations of the scene.

Circa 630-620 BC. Excavated in front of the temple at the

Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta. Height 11 cm, width 8.25 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 15365.

|

The fragments of the small, rectangular ivory relief are incomplete, but the bearded Perseus appears to be standing in profile, with the sword in his right hand, and his left grasping two of the snakes which grow from Medusa's head. The sickle-winged Gorgon, depicted as much larger than Perseus, with a huge head and wearing a long skirt, has her back to him and has fallen to her knees, with both legs together. Perseus has his left foot on the back of her calves. The archaeologist Alan Johnston, commenting on the similar pose of Odysseus blinding the Cyclops Polyphemos on the "Eleusis Amphora", noted: "He kneels on his opponent like a pharaoh." * The head of Medusa too appears to be influenced by Egyptian art, although the state of the fragments allows no certainty. The plaque has been reconstructed to show her with a potruding tongue.

Two holes can be seen in the horizontal centre of the plaque, one immediately left of Medusa's head and the other behind of Perseus' left heel. These were for nailing or riveting the plaque to another object.

This was one the enormous number of ancient objects discovered by British archaeologists at the Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta during excavations in 1906-1910, including several Archaic representations of Gorgons: on vase fragments (the earliest around 625 BC); terracotta masks (see below); an ivory plaque apparently showing a Gorgon as a sphinx (image, right); a small lead figure of a running Gorgon (see below, right), and a high relief of a Gorgon head on a fragment of a large marble lustral bowl (6th century BC). Many of the objects were dated according to the type of pottery found at the same level in the earth (Laconian I-VI, Protocorinthian, Corinthian, etc).

Most of the finds are now in the Sparta Archaeological Museum, some are in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, and others in the British Museum and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. The majority are in storage and not on display.

* Alan Johnston, Pre-Classical Greece, in John Boardman (editor), The Oxford history of classical art, page 32. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Image source: Richard MacGillivray Dawkins (editor), The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta, excavated and described by members of the British School at Athens, 1906-1910. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, Supplementary Paper No. 5. Macmillan, London, 1929. At the University of Chicago Library.

Perseus and Medusa, Plate CVI, 1, and text on pages 211 and 213. Gorgon/sphinx, plate CII, 1, and text on pages 209-210.

See also ivory combs from the sanctuary with carved reliefs of the Judgement of Paris (on the Hermes page) and the suicide of Ajax (in Homer part 2). |

|

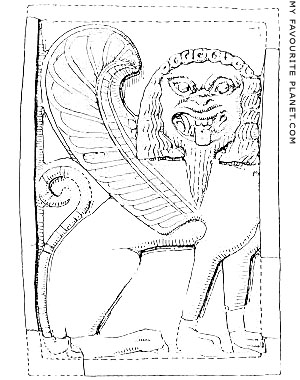

Reconstruction drawing of a Gorgon

on a fragmentary ivory plaque from the

Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, Sparta.

The figure has a lion-mask head

with long wavy hair, a pointed

beard and a sickle shaped wing.

She has the body of a seated lion

as in depictions of sphinxes.

Early 7th century BC.

Height 6 cm, width 4 cm. |

|

| |

|

|

|

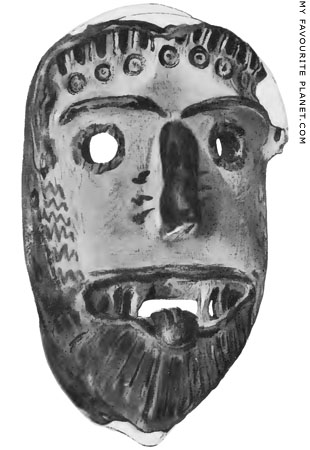

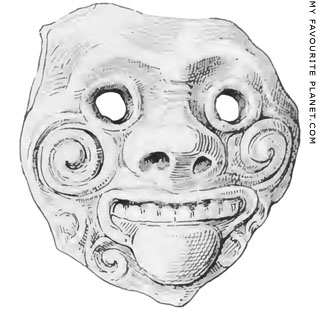

A photo and a drawing of terracotta Gorgon masks

found at the Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, Sparta.

Mid 6th century BC.

Sparta Archaeological Museum.

Mask left, Inv. No. 1948a. On display.

Height 15.5 cm, inside width 7 cm, thickness 1 - 1.6 cm.

Mask right, unknown.

|

|

Two of a large number of small terracotta votive masks and thousands of fragments found at the Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, Sparta during the 1906-1910 excavations. Some date from the early 7th century BC, while the majority are from the 6th century BC, after the building of the second temple of Artemis Orthia around 600 BC, when the dedication of votive masks appears to have become more popular. They depict Gorgons (15 masks and fragments), satyrs, grotesque caricatures with furrowed faces and humans, which may have been females ("old women"), youths and warriors. Some appear more realistic and were perhaps portraits or idealized heroes.

Many were brightly painted in purple, brown and black. Generally, the noses were not hollowed behind, and some had no holes at all. This and their small size led archaeologists to conclude that they were not meant to be worn, but were hung from walls and trees. Along with other types of Spartan ceramic objects, the number, quality and originality of masks diminished from around 550 BC, and no examples were found of Gorgon, satyr or "portrait" type masks from the 5th century BC.

The purpose of the masks is unknown, but perhaps they had an apotropaic function or were used in rituals. Connections with funerary (sepulchral) offerings or ex-votos for cures from illness have been ruled out due of the temple context and because Artemis is not known to have been considered as a healing deity. Their grotesque designs would render most unsuitable as honorific masks. Although there was no developed drama at this time in Sparta, they may have been associated with some sort of theatre or sacred performance, perhaps with the ritual orgiastic dances known to have been performed at Sparta. From ancient sources, it appears that such dances were performed in honour of Artemis by men in feminine masks made of wood (κύριθρα, wooden masks). Such wooden masks have not survived, but these may be replicas. Another suggestion is that the masks may have been connected with the rites of passage undertaken by Spartan boys.

Both of the Gorgon masks illustrated above have round eye-holes and potruding tongues, but, like many of the masks from the sanctuary, neither has ears. The mask on the left has a long, flat face, with an opening for the mouth which has long fangs. It appears masculine, with heavy eyebrows and beard, and a long, straight, rectangular nose, which is not hollow. Details were made with modelled relief and black and purple paint. The spiky hair, side whiskers and the wrinkles on either side of the nose are painted, as are the rings of the hair crest above the forehead (on other Gorgon depictions shown as snailshells, spirals or waves), here represented by a row of dotted circles. Although the design is primitive, the pigments used are thought to correspond with those of Laconian IV pottery, around 550-500 BC. The mask may have been made from a mould, perhaps of wood, but no mask moulds were discovered during the excavations.

The mask on the right, which seems more jolly, has a snub nose with wrinkles, a large, round tongue, and a row of even top teeth. Neither the nose nor the mouth are pierced, and it is considered to be too small to have been worn. Slight traces of red-brown paint have been preserved. The spirals on the cheeks may imitate tattoos.

|

A bearded Gorgoneion on the back

of a scarab-shaped bezel of a lead

votive ring from the Sanctuary of

Artemis Orthia, Sparta. 700-635 BC.

Among around ten thousand

votive lead objects, in a variety of

forms, found during excavations

at the sanctuary, 1906-1910. |

| |

Lead votive figurine of a running

bearded female, probably a Gorgon.

6th century BC. From the Sanctuary

of Artemis Orthia, Sparta.

Drawings from R. M. Dawkins,

The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia

at Sparta, see below. |

| |

Image source (masks): The Annual of the British School at Athens, Volume 12, 1905-1906,

plates X and XIa; text on pages 324-327 (R. M. Dawkins) and 338-343 (R. C. Bosanquet). At the Internet Archive.

The annual contains reports by archaeologists on the first year of excavations at Sparta, with brief descriptions of finds. The photo on Plate X is in colour, but the scanned version is in black and white.

See also: Richard MacGillivray Dawkins (editor), The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta, excavated and described by members of the British School at Athens, 1906-1910. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, Supplementary Paper No. 5. Macmillan, London, 1929. At the University of Chicago Library.

Masks, plate LVI, 2 and 3; text in chapter 5, pages 163-186, particularly 169 and 183. Gorgoneion on scarab ring bezel, Fig. 118, d, text page 255. Lead Gorgon figurine, Fig. 126, k, text page 271.

A scan of the book The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta is also available At the Internet Archive, but only with plates upto CVI (106).

The chapter on the terracotta masks was written by Guy Dickins of the British School at Athens (see the note in Demeter part 2). He called the masks of the first half of the 6th century, "vigorous and individual creations, the more elaborate examples of fantasy and realism" (page 166). He also described one of the masks (Plate LVI, 3, the drawing on the right, above) as "diminutive", but unfortunately he did not state the sizes of the masks. Over a century later, many of the masks have still not been published, and very little has been published specifically about the Gorgon masks.

See also: masks of Dionysus |

|

|

| |

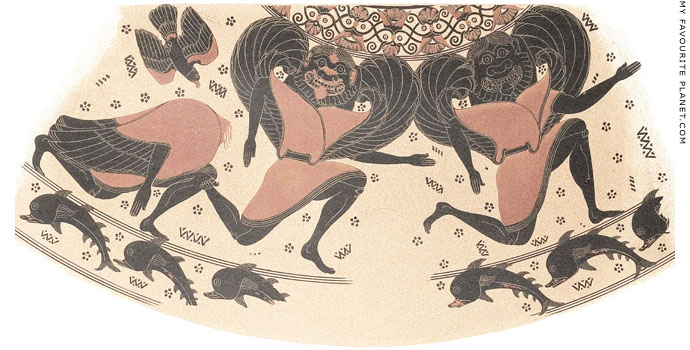

An Archaic vase painting of two running winged Gorgons.

Behind them the body of the decapitated Medusa.

Detail of the body of an Archaic Attic black-figure neck amphora,

circa 620–610 BC. Known as the "Nessos Amphora", it is the name

vase of the Nessos Painter, named after the inscribed painting on

the neck depicting Herakles fighting with the Centaur Nessos.

Watercolour by Émile Gilliéron (1850-1924).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 1002 (CC 657).

|

The 122 cm tall amphora was excavated in Pireaus Street, Keramaikos, central Athens in 1890.

Medusa's sisters, Stheno and Euryale, wearing short, belted chitons, run or fly to the right in the "Knielauf" position. The face of the Gorgon in the centre has detailing in red. Strangely, her left arm is shown behind her wing, which may be an oversight or whimsy of the painter. On the left, the headless body of Medusa slumps forward, her wings and arms lowered, and blood pours from her neck. A bird of prey hovers above the corpse.

The faces of the Gorgon sisters are painted in a variant of the lion mask. Their wavy hair is neatly parted in the middle, and they have what appear to be beards, in the form of thick curls hanging around the line of their jaws. These "beards" may have originated from images of Medusa's head in which dripping blood or bloody veins and sinews hang below her head like spikes (see, for example, the Gorgoneion below). The tips of their noses and nostrils are indicated by an outline shaped like a ram's head (or Ionic capital).

Below the Gorgons are a row of leaping dolphins, perhaps suggesting that the scene is taking place near the sea. Perseus does not appear on the amphora which is only decorated on one side: the rear, although fragmentary, is marked only with three brushstrokes. It has been suggested that Perseus may been painted on a twin amphora, now lost.

The painting on the neck shows Herakles fighting the centaur Nessos. The scene has given the name to the vase and the Nessos Painter.

Source of images: Valerios Stais, Paul Wolters, Amphora aus Athen, in Antike Denkmäler Band I, pages 46-48 and plate 57. Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1891. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

A now lost fragmentary louterion (λουτήριον, wide spouted krater), also attributed to the Nessos Painter, was found in a well in the ancient city of Aegina, among other ceramic fragments, mostly of Corinthian pottery. Two of the inscribed painted panels from around the top of the vessel's body had survived. One showed Athena (name inscribed) standing behind Perseus (name inscribed) running or flying to the right in the "Knielauf" position, pursuing the headless Medusa and her two Gorgon sisters (figures missing). The other panel depicted two winged Harpies (inscription ΑΡΕΠΥΙΕ), running/flying to the right. Fragments of a lower band showed sphinxes and animals (horses, panthers, bulls). Height of louterion 28 cm, diameter 55 cm. State Museums Berlin (SMB). Inv. No. F 1682.

See: Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907), Beschreibung der Vasensammlung im Antiquarium, Erster Band. Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Pages 220-221, No. 1682 (2636). W. Spemann, Berlin, 1885. At the Internet Archive. |

A reconstruction drawing of the front

of the amphora by Émile Gilliéron. |

| |

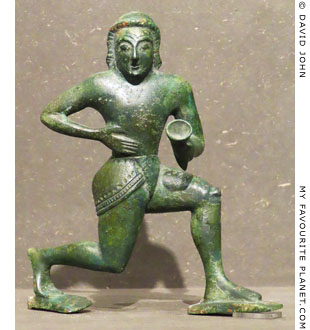

A bronze figurine of a komast (reveller),

holding a rhyton (drinking horn) his left

hand, running in the "Knielauf" position.

Thought to be an attachment from a

bronze cauldron. Probably made in

a Laconian workshop around 570 BC.

Found in the Mon Repos estate, Corfu,

site of the ancient city Korkyra (see the

Gorgon pediment in Medusa part 3).

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 1602. |

| |

| |

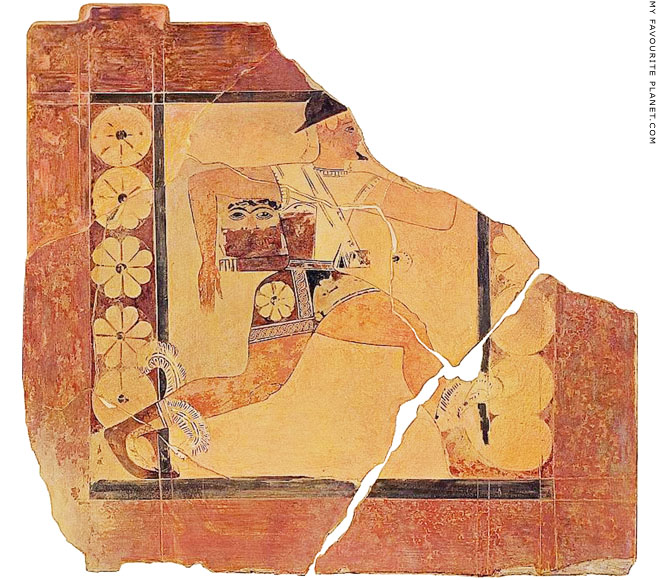

Perseus flies with the head of Medusa.

Fragments of a painted terracotta plaque, probably a metope, from the wooden temple

of Apollo, Thermon (Θέρμος), Aetolia, central Greece. Circa 630-620 BC. Thought to be

the work of a Corinthian workshop. Excavated at Thermon in 1889. Height 87.8 cm.

Watercolour by Émile Gilliéron (1850-1924).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 13401.

|

A youthful Perseus, with a goatee beard, strides to the right in the "Knielauf" position. He wears a black petasos (brimmed sun hat), a short, belted chiton and winged boots. A scabbard hangs from a strap slung diagonally over his right shoulder: part of the sword's hilt can still be seen. Under his right arm the top of Medusa's frontal head appears over the top of the kibisis (κίβισις), the pouch he has been given by the Nymphs. The mouth is visible through the fabric of the pouch.

Image source: Georg Kawerau, Giorgios Sotiriades, Der Apollotempel zu Thermos,

in Antiker Denkmaler Band II, 1902-1908, pages 1-8 and plate 51.1.

Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The Roman mythographer Hyginus summarized the story of Perseus and the Medusa, including the assistance the hero was given by the gods, in an account of the mythical origin of the stellar constellation Perseus:

"He [Perseus] is said to have come to the stars because of his nobility and the unusual nature of his conception. When sent by Polydectes, son of Magnes, to the Gorgons, he received from Mercury [Hermes], who is thought to have loved him, talaria and petasus, and, in addition, a helmet which kept its wearer from being seen by an enemy. So the Greeks have called it the helmet of Haides [the Unseen One], though Perseus did not, as some ignorant people interpret it, wear the helmet of Orcus himself, for no educated person could believe that.

He is said, too, to have received from Vulcan [Hephaistos] a knife made of adamant, with which he killed Medusa the Gorgon. The deed itself no one has described. But as Aeschylus, the writer of tragedies, says in his Phorcides, the Graeae were guardians of the Gorgons. We wrote about them in the first book of the Genealogiae. They are thought to have had but one eye among them, and thus to have kept guard, watch one taking it in her turn. This eye Perseus snatches, as one was passing it to another, and threw is in Lake Tritonis. So, when the guards were blinded, he easily killed the Gorgon when she was overcome with sleep.

Minerva [Athena] is said to have the head on her breastplate. Euhemerus says the Gorgon was killed by Minerva. We shall speak more of this later on."

Hyginus, Astronomica, 2.12, Perseus. At the Theoi Project.

If Hyginus wrote more concerning the claim that Athena killed the Gorgon it has not survived in the manuscript, neither has the passage concerning the Graeae from "the first book of the Genealogiae", which is thought to have been the original title of his Fabulae. For further information about Hyginus, see the note in Homer part 2.

See also Hyginus' summary of the story of Perseus and Andromeda in Medusa part 1. |

|

|

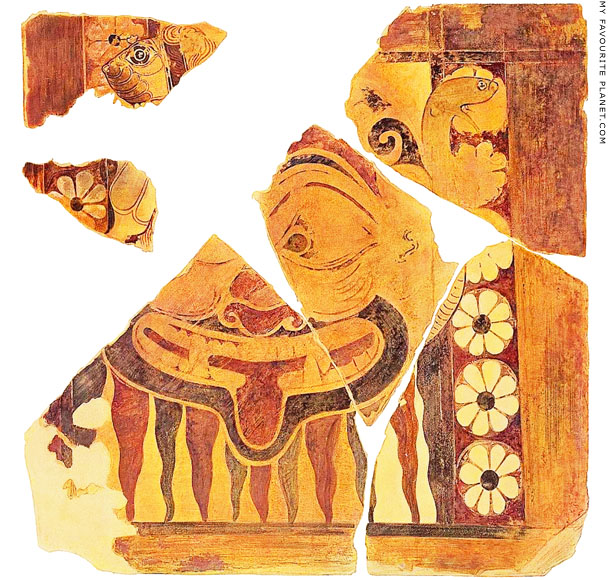

| |

Gorgoneion.

Fragments of a painted terracotta plaque, probably a metope, from the wooden

temple of Apollo, Thermon (Θέρμος), Aetolia, central Greece. Circa 630-620 BC.

Thought to be the work of a Corinthian workshop. Excavated at Thermon

in 1889. Height 87-89 cm, width 99 cm, thickness 5.5 cm.

Watercolour by Émile Gilliéron (1850-1924).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

|

Bloody tendrils hang from the severed head, which has enormous eyes, wrinkled cheeks and a nose indicated by a countoured shape, like a ram's head (as on the "Nessos Amphora" above). The head of a griffin can be seen growing from the head, top left, and a snake on the right.

Ovid wrote that as Perseus flew over the Libyan desert carrying Medusa's head, drops of blood from it fell onto the sand and turned into deadly snakes which infested the land:

"... as he bore

the viperous monster-head on sounding wings

hovered a conqueror in the fluent air,

over sands, Libyan, where the Gorgon-head

dropped clots of gore, that, quickening on the ground,

became unnumbered serpents; fitting cause

to curse with vipers that infested land."

Brookes More (translator), Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 4, lines 604-705.

Cornhill Publishing Co., Boston, 1922. At Perseus Digital Library.

Image source: Georg Kawerau, Giorgios Sotiriades, Der Apollotempel zu Thermos,

in Antiker Denkmaler Band II, 1902-1908, pages 1-8 and plate 52.

Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

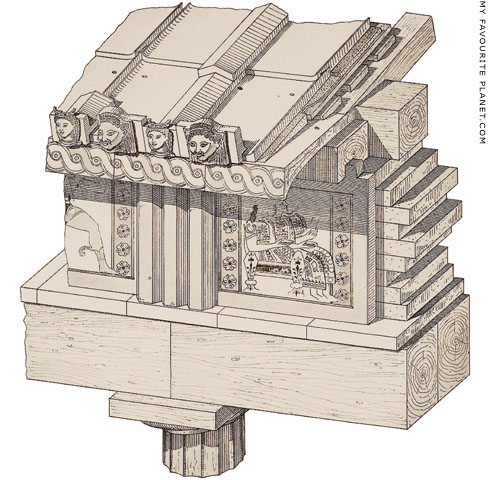

A reconstruction drawing by the German architect and archaeologist

Georg Kawerau (1856-1909) of part of the roof and entablature of the

Doric temple of Apollo at Thermon, showing the antefixes and metopes.

See more about antefixes in Medusa part 4.

Image source: Georg Kawerau, Giorgios Sotiriades, Der Apollotempel zu Thermos,

in Antiker Denkmaler Band II, 1902-1908, pages 1-8 and plate 49-1.

Kaiserlich Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1908.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

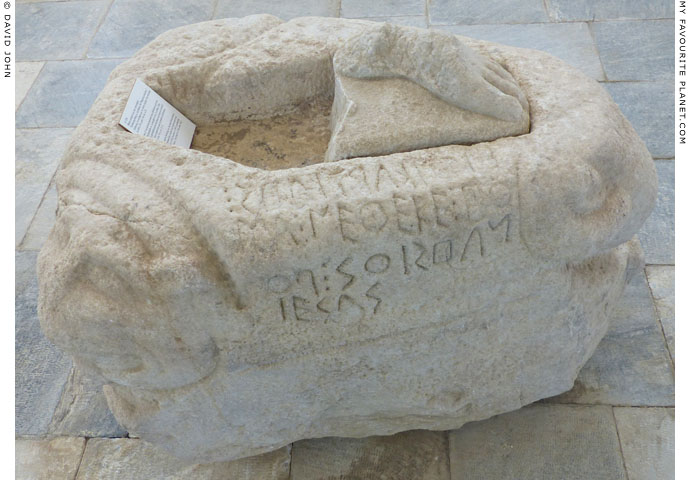

An inscribed triangular statue base from Delos with the relief of a protome (head) at each corner.

At the front (right in this photo) is the head of a ram. At the rear: on the right (top in this photo)

the head of a lion (see photo below), and left (left in photo) a Gorgoneion (see photo below).

Around 650-600 BC. Found in 1885, during excavations by the French Archaeological School,

north of the Prytaneion, on the south side of the Sanctuary of Apollo, Delos. Height 58 cm.

Delos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. A 728.

|

On top of the marble statue base is part of the left foot of a male kouros statue on a wedge-shaped plinth fragment which fits exactly into the front of the hexagonal cavity carved for the sculpture. Part of two toes from the right foot are also visible on the base. Another fragment of the right foot was also discovered, but has been since lost. It is thought that the kouros fragment A 4052 (photo, right) may belong to the base, although this suggestion has been rejected by some scholars.

The face of the ram on the corner at the front of the triangular base is totally smooth: either the features have been destroyed or worn away, or it was left unfinished.

Around the top of the lion head (photo below) on the right corner at the rear of the base is a mane. It has a protruding tongue and the jug-handle shaped ears are set high on its head. The ears are the only features that appear to distinguish it from a Gorgoneion, particularly since the nose is now missing, and some scholars have interpreted it as a head of Gorgon or Phobos (Fear).

The Gorgoneion (photo below) is also very worn, and no ears are visible. It has a protruding tongue, but the nose appears more human than lionine. Depictions of Gorgon heads in the form of a "lion mask" or "humanoid lion" are known from the late 7th century BC (see images above and below). Here we appear to have carvings of a lion and a Gorgon which are very similar. It may be that the features were further distinguished by paint.

The inscription on the right side of the base is the signature of the sculptor and dedicator Euthykartides, one of the earliest surviving signatures of a Greek sculptor. It is written in boustrophedon (βουστροφηδόν, ox-turning, as in ploughing a field), that is with the lettering and direction of the writing reversed on alternate lines. The punctuation is in the form of tricolons (or triple colon).

ευθυκαρτιδες ⋮

μ´α ⋮ νεθεκε ⋮ ηο

Ναησιοσ ⋮ πο

ιεσας

(Euthykartides m'anetheke ho nahsios poiesas)

Euthykartides the Naxian dedicated me, having made [me].

Inscription IG XII 5, 2.

See:

Jeffrey M. Hurwit, Artists and signatures in Ancient Greece, pages 3-10. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Euthykartides' feet: Reflections on signatures, status, and originality in Greek art. A video of a lecture given by Jeffrey M. Hurwit at the Athens Centre, Pangrati, Athens, on 23th July 2013. At YouTube.

See also a Gorgoneion antefix from Delos in part 4. |

|

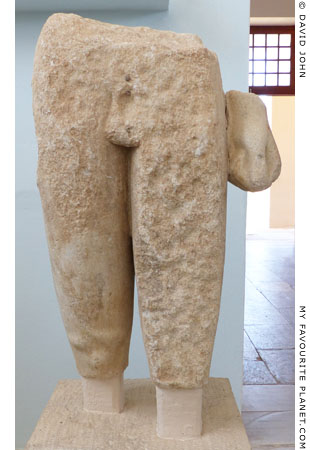

The lower part of the kouros statue

thought to belong to the statue base.

End of the 7th century BC.

Delos Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. A 4052. |

|

| |

The lion protome (head) on the right corner at the rear of the kouros base in Delos. |

| |

The Gorgoneion on the left corner at the rear of the kouros base in Delos. |

| |

Ceramic plate showing a winged goddess with the head of a Gorgon,

wearing a split skirt, and holding in each hand a water bird by its neck.

Made on Kos about 600 BC. Excavated during the 1850s at Kamiros, western

Rhodes by Auguste Salzmann (1824-1872) and Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833-1915),

who sold it to the British Museum in 1860 along with other finds. Height 2.5 cm,

diameter 32 cm, weight: 1.19 kg.

The goddess is thought to be Potnia Theron (Πότνια Θηρῶν), the Mistress of Animals,

depicted in ancient Minoan, Mycenaean, Greek and Etruscan art as a winged goddess

holding animals in both hands. She has been associated with or identified as Artemis

by some scholars. It is not known why the figure on this plate has a Gorgon's head,

or to put it another way, why a Gorgon was depicted as the Mistress of Animals.

See further discussion in Medusa part 3.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1860.4-4.2 (Vase G13/6).

See a Gorgoneion on a Corinthian cup of the same period, also found at Kamiros, below. |

| |

A running/flying Medusa wih sickle-shaped wings on an Attic black-figure plate

by the Anagyrous Painter (or Anagyrus Painter, attribution by John Beazley),

600-575 BC, who was named after the place where this plate was found.

Around its edge is a continuous chain of lotus flowers.

Restored from several fragments. Found during the 1936-1936 excavations

by Greek archaeologists G. Oikonomou and Ph. Stavropoulos at modern Vari

(Βάρη), of the Archaic tumuli cemetery of the ancient deme of Anagyrous

(Αναγυρούντος), on the west coast of Attica. So far pottery attributed to the

Anagyrous Painter has only been found there, and it is thought that he may

have worked in the area, producing for the local market.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No 19171.

Beazley Archive Database, Vase No. 300245 |

| |

Detail of the Medusa by the Anagyrous Painter (see above). |

| |

A running/flying Gorgon on a fragment of a black-figure krater. Much of the colour

has worn away so that it is now difficult to see the details (see drawing below).

Around 600 BC. From the "Agamemnoneion" (see Homer part 2), Mycenae.

Mycenae Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MM 1210. |

| |

Detail of a drawing of the krater fragments in Mycenae.

Mycenae Archaeological Museum.

|

As usual with black-figure pottery painting, outlines and details have been drawn by incising (scratching) lines through the paint into the surface of the clay. On the fragment to the left of the Gorgon is the head of a wild boar, facing right, above a smaller pig walking to the left. On the fragment to the right is part of the tail and hind leg of a hoofed animal.

The Gorgon is under the surviving handle of the broken vessel. She runs/flies to the right, with her lower torso and legs shown in profile, and her upper body and head frontal (facing the viewer) and at an angle so that she seems to be leaning forwards (to the right). She has two sickle shaped wings, shoulder-length hair and wears a thigh-length chiton (tunic) that is belted at the waist. In her raised hands she holds a snake in front of her forehead. The snake's head is above her right fist, and the tail above the left. Her forearms appear to be behind the wing tips. Part of an unidentified object, apparently not attached to the Gorgon, can be seen below her left wing. |

|

|

| |

A Gorgoneion on the inside of a Corinthian black-figure kylix

(drinking cup) by the Cavalcade Painter, 600-575 BC.

Unknown provenance. On the outside of the cup: side A, a boar hunt;

side B, Greek soldiers fighting between horsemen.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No 830. |

| |

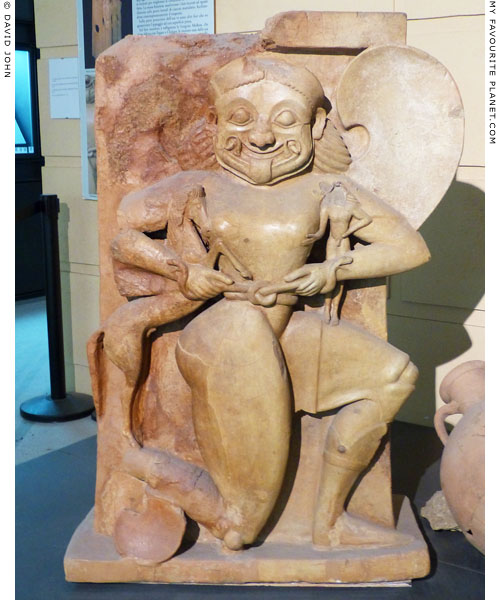

A relief of Medusa holding Pegasus on the leg of a cast bronze tripod.

Made in a Corinthian workshop, around 600 BC.

Excavated at the Sanctuary of Olympia, Greece.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. B 7000.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia.

|

One of several bronze artefacts, tripod legs, furniture covers and shield straps, discovered at Olympia with series of reliefs depicting mythological scenes, in vertically arranged panels (like a film strip or comic strip), comparable to reliefs on the horizontally arranged metopes of ancient Greek temples. This image is in the lowest of six surviving panels on a bronze tripod leg made in Corinth around 600 BC. All of the images are predominatly zoomorphic (featuring animals), and one depicts Odysseus escaping from the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemos by hiding beneath a giant ram (see Homer part 3).

The Gorgon is decidedly of the ugly type, and with her horns, terrible eyes and grimace, quite demonic. She has a snaky fringe and two snakes rise from behind her ears. Although the artist has put considerable effort into the details of her head, the rest of her body is quite plain. She has thin arms and an oblong upper torso, like the head shown frontally. The waist appears to be tightly drawn by a belt (which was perhaps inlaid?), but this is no longer to be seen. She sits awkwardly on what appears to be the capital of an Ionic column, with her lower torso and thighs - shown just as an oval form - shown in profile. The bottom of her long skirt and a foot are visible to the left of Pegasus. She holds her equine child under its stomach with her right hand, and its front legs with the left.

On the wall to the left of her head is a lizard, described by the museum label as "an underworld being symbolizing the gorgon's death". The bottom of the panel's frame is decorated with a meander pattern.

As in a small number of other Archaic depictions of Medusa, she is shown with Pegasus while she is still alive, although surviving versions of the myths say that she gave birth to her two children after being decapitated by Perseus. This apparent inconsistency has caused speculation among historians. Since most of the depictions are thought to have been made by artists from Corinth or its colonies (e.g. Syracuse, Corfu), it has been suggested that it may be due to the fact that Pegasus was a symbol of the city, associated with its mythical history, and appeared on its coins. In the case of the Gorgon pediment in Corfu, for example, it has even led to the theory that the Gorgon was an early form of Artemis.

See other examples of Medusa with Pegasus below:

a plaque in Syracuse;

a metope in Selinunte;

an altar in Gela (also with Chrysaor);

Medusa riding Pegasus on a Middle Corinthian vase from Syracuse.

Also:

the Gorgon pediment in Corfu (also with Chrysaor) in Medusa part 3. |

|

The tripod leg

in Olympia. |

|

| |

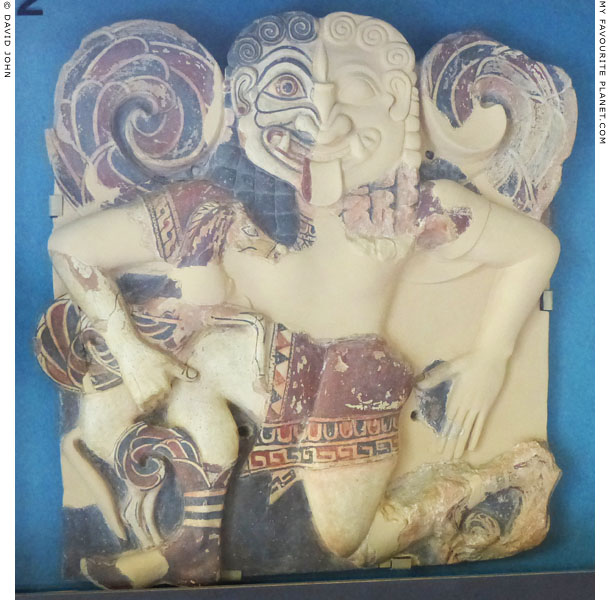

Restored painted terracotta plaque with a relief of a running/flying

winged Gorgon, carrying winged Pegasus under her right arm.

End of the 7th century BC. Found in the Via Minerva, Ortygia, Syracuse, Sicily.

Height 56 cm, width 50 cm.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily.

Inv. No. 34540, 34543, 34895 (fragments).

|

The fragments of the figure were discovered during excavations in 1913-1914 around the site of the temple of Athena on the island of Ortygia (Ὀρτυγία), Syracuse (Συράκουσαι; Italian, Siracusa), founded in 734 or 733 BC by Greek colonists from Corinth and Tenea in Corinthia (see Demeter and Persephone part 1). The first temple was built on the site in the 8th century BC, and enlarged in the second half of 7th century. It was replaced in the early 5th century BC by a Doric temple built by the tyrant Gelon (Γέλων, died 478 BC) to commemorate the Sicilian Greek defeat of the Carthaginian invasion at the Battle of Himera in 480 BC, at the same time as Xerxes' Persian invasion of Greece was thwarted at the Battle of Salamis (Herodotus, The Histories, Book 7, chapter 166, section 1).

The Cathedral of Syracuse was built by Bishop Zosimo in the mid 7th century AD over the remains of the temple, using the ancient columns and other architectural elements which can still be seen inside and outside the building. The Via Minerva is today known as the Piazza Minerva, a large square on the north side of the cathedral which covers part of the sanctuary of Athena. The Gorgon plaque may have decorated an altar or a metope of a Protoarchaic building in the sanctuary.

The plaque, made in a mould and finished by hand, is of orange clay with a pale yellow-beige slip, painted in blue, black, red, purple and yellow, with a black backgound. The four, symmetrically arranged holes indicate that it was nailed to a wooden support.

Medusa, wearing a short tunic, a split skirt and winged boots, runs/flies to the left in the "Knielauf" position. Her frontal, lion-mask head is topped by two symmetrical rows of spiral curls; locks in incised chequered patterns fall over her shoulders. Her three (of originally four) sickle-shaped wings, like those on her boots and Pegasus, are tightly curled like sea waves, with rows of stylized feathers painted red and blue. She has an earring (or hole for one), marked by a red dot on her right earlobe.

She holds her child Pegasus in her lowered right hand, supporting it below the stomach on bent fingers. The reconstruction of the left hand shows her to have very long fingers. It is thought that she originally held her son Chrysaor on her left arm and shoulder (see photo below).

This is one of the earliest of a large number of ancient depictions of Gorgons found on Sicily. According to Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 6, chapter 3), Syracuse was founded by colonists from Corinth around 734 BC, and the iconography of such depictions may have been influenced by Corinthian models [1]. |

|

|

| |

|

|

A fragment of the handle of a painted ceramic vessel in the form

of a figure, now headless, holding a Gorgoneion with both hands.

6th century BC. Possibly an Attic work. Found in

Tanagra (Τανάγρα), Boeotia, central Greece.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

The bone handle of a comb with a relief of a Gorgoneion, 625-600 BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No 15507. |

| |

Fragment of a bronze sheet with a repoussé relief of a Gorgoneion.

6th century BC. From a grave at Akraiphnio (ancient

Akraiphia, Ἀκραιφία), Boeotia, central Greece.

One of two almost identical examples displayed in the museum.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Fragment of a bronze fibula (safety pin) decorated with a relief of a winged

Gorgon in the "Knielauf" position, Next to her right leg is a flying bird.

Late 6th century BC. From a grave at Akraiphnio (ancient

Akraiphia, Ἀκραιφία), Boeotia, central Greece.

Thebes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A bronze fibula (safety pin) decorated with a relief of a Gorgoneion.

Around 500 BC. From Boeotia, central Greece.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 8918. |

| |

|

A small bone plaque depicting a Gorgon in the "Knielauf" position, running/flying

to the left, and holding a snake in each hand. The tops of her wings rise from

behind her shoulders and curl in spirals at either side of her head. A similarly

curled wing emerges from the front of each of her boots.

Made in Ionia, around 575-550 BC.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. |

| |

Fragmentary terracotta arula (small, portable altar) with

a relief of a winged Gorgon in the "Knielauf" position.

From the Sanctuary of Demeter Malophoros, Selinous

(Σελινοῦς; today Selinunte), southwest Sicily. 560 BC.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily.

See another altar with a relief of Medusa from Gela, Sicily, below. |

| |

Metope with a relief of Perseus killing the Gorgon Medusa, with the aid of

Athena (left), from Temple C, on the acropolis of Selinous (Selinunte), Sicily.

540-510 BC. Local limestone from Menfi, northeast of Selinunte. Height 147 cm.

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, Sicily.

|

Medusa, in the "Knielauf" position, holds Pegasus with her right hand. Perseus, wearing winged sandals, averts his gaze from the Gorgon and decapitates her with a sword in his right hand, while with his left hand he grasps the hair on the top of her head. This metope (metope VII) was one of ten which decorated the east end above the entrance of the Doric temple, thought to have been dedicated to Apollo. Corinthian pottery discovered in building's the foundations indicate that its construction began around 560-550 BC, but it is not known when it was completed (see a map of the location of Temple C on the Selinous acropolis in Demeter and Persephone part 1). Three of the metopes, with reliefs of mythological scenes, as well as four triglyphs and other parts of the entablature, are wonderfully displayed in the Palermo museum. The pediment, only fragments of which have survived, was decorated by an emormous polychrome terracotta Gorgoneion mask (see Medusa part 3). |

|

|

| |

Ceramic arula (altar) with a high relief of Medusa carrying Pegasus and Chrysaor.

Pink clay. 500-480 BC. From the emporion (ἐμπόριον, trading centre) of the

Bosco Littorio, Gela, Sicily. Height 116 cm, width 35 cm, length (at base) 77 cm.

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum, Sicily. Inv. No. Sop BL 10. |

| |

One of three similar, well-preserved portable altars with reliefs of extraordinarily fine quality, discovered with fragments of others at the Bosco Littorio archaeological site in December 1999, during excavations by Lavinia Sole under the direction of Sopraintendente Rosalbe Panvini. The relief on one of the other two altars depicts Eos abducting Kephalos, and the third is thought to represent Demeter, Persephone and Hekate or Aphrodite. All three altars are exhibited in the excellent Gela museum.

These light-weight altars, probably made in the same workshop, had apparently never been used, and may have been made for sale or export to customers who for some reason never received them. The site at the Bosco Littorio, on the coast of Gela (Γέλα), south of the acropolis (Lindioi, Λίνδιοι) and west of the mouth of the Gelas river, is thought to have been an emporium due to finds of objects related to trade, including transport amphorae and imported vessels from Attica and Chalcis (Euboea) in Greece. The buildings at the site have been dated to the early 6th to early 5th centuries BC, and the altars appear to have been abandoned there around 480 BC, when the buildings of the area were violently burnt and destroyed.

The bodies of the altars, made of clay slabs, are hollow and perforated by large holes (see photo, right), making them lighter and easier to transport. These are among several portable altars found in Sicily (see, for example, the portable altar from Selinunte above). The reliefs, which were made separately then attached to the bodies before firing, were originally highly coloured, with red used as a background colour, and a yellow pigment which became almost vitrified (glass-like) during firing.

The almost life-size figure of Medusa is made of pink clay and has a highly polished finish. Although the strong, flat colours of the Gorgon plaque in Syracuse (above) have immediate appeal and fascination, the plasticity of this figure lends it a powerful physical presence which may have been enhanced or diminished by the addition of paint. In contrast to the bulky, muscular Gorgon (particularly the thighs), the figures of Pegasus and Chrysaor appear thin and less convincing. Below Medusa's right shin is one of her ankle wings in the form of a concave disc with a semi-circular curve cut out of the top left.

It is not known for which deity sacrifices would have been made at this altar, but it is thought that the figures on this and the other two altars from the Bosco Littorio were in some way associated with fertility, birth and rebirth. On her death Medusa gave birth to Pegasus and Chrysaor, and Ovid wrote that the Gorgon's blood falling on the sands of the Libyan desert gave birth to snakes (see above). It has been suggested that Medusa, or sacrificial blood, may have thus been associated with these three phenomena.

See: Dirk Booms and Peter Higgs, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, exhibition catalogue, pages 58-62. The British Museum, London, 2016.

The archaeological site at the Bosco Littorio is not usually open to the public, but is sporadically opened on special occasions.

See also Gorgon antefixes from Gela in Medusa part 4. |

|

The rear and left side of the altar,

showing the holes in the clay slabs

which form the hollow body. This

construction method made the

altar lighter and easier to transport. |

|

| |

Pegasus and Chrysaor on the altar relief in Gela. Medusa tightens her belt of

snakes, which here appear to protect her children. Pegasus' snout nuzzles her

right breast, while Chrysaor's right arm and hand are attached to her left breast. |

| |

Gorgon Medusa riding Pegasus on a fragmentary

Middle Corinthian vase. 600-575 BC.

From an ancient necropolis of Syracuse, Sicily.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 52244.

|

Only two fragments of the ceramic figure have survived. The upper fragment represents Medusa's lion-mask head and part of her slim-waisted upper torso. Each of her hands grasp a snake, decorated with dark blue dots, which she wears like a scarf around her shoulders, the ends twisted together. Her belt also appears to be a snake (or snakes).

The lower fragment is in the form of the front of a horse with raised forelegs. Part of the Gorgon's right leg can be seen hugging the side of its body. The rectangular base has a chequered pattern painted on the front.

This is the only ancient object I know of with a Gorgon riding Pegasus. As with the ceramic relief of Medusa with Pegasus above, depictions of Medusa with her children are rare, presumably since the myths relate that they were born after she had been killed by Perseus. Her association with horses was suggested in the first known depictions of her, the earliest of which is on apithos found in Thebes, dated to around 670 BC, where she is represented as a female centaur (see the image and article at the top of this page).

So far I have found no literature with further information about this object. The few publications which mention it refer to a short essay by Enrico Paribeni, which I have not yet seen:

Enrico Paribeni, The riding Gorgon, in Lucy Freeman Sandler (editor), Essays in memory of Karl Lehmann (Marsyas Supplementum 1), pages 252-254. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1964.

If you have any further information, please get in contact. |

|

|

| |

A semi-circular gold plate riveted onto a bronze plaque, with a

relief of a running/flying Gorgon holding a snake in each hand.

One of two similar plaques found in Delphi, among several objects

associated with a chryselephantine statue of a female figure, probably

Artemis. They may have been fibulae, attached to the statue's dress

at the shoulders. The Gorgon's head is truly "horrid" and beast-like.

From a workshop in East Greece (Ionia), probably Samos. 6th century BC.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. |

| |

Small bronze figure of a running/flying Gorgon.

A decoration of a bronze vessel. From the Sanctuary

of Hera, Perachora, Corinthia, Greece. 560-525 BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 16149. |

| |

Small bronze figure of a running/flying Gorgon.

Probably a decoration of a bronze vessel. From the

Sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia, Greece. 6th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 6088. |

| |

Small bronze figure of a running/flying Gorgon.

An attachment from a bronze vessel. From the sanctuary

of Apollo Hyperteleatas (Απόλλωνος Υπερτελεάτα), Phoiniki

(Φοινίκι), Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. 6th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 10708. |

| |

A small bronze figure of a winged Gorgon, wearing a

chiton (tunic) and standing on an oversized lion's paw.

Probably a support for a bronze untensil.

6th century BC. From the sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia.

See other Gorgons from Olympia in Medusa part 6. |

| |

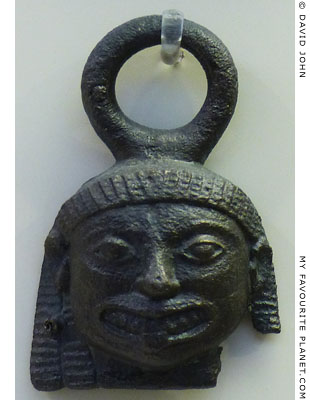

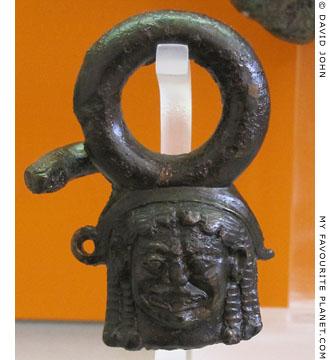

A bronze vase handle with an attachment

in the form of a Gorgoneion.

6th - 5th century BC. From the

sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia.

Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Exhibited in the Museum of the History of

the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Vertical handles of bronze ritual vessels terminating

in Gorgon heads. From Delphi, 6th century BC.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. |

|

| |

Small figure of a winged Gorgon running/flying to the right, flanked by

two gryphon protomes, on part of the bronze handle of a volute krater.

Around 525-500 BC. Acquired in 1868 in Cilicia, south Anatolia (today

southern Turkey), for the collection of Louis de Clercq (1836-1901).

Height 20.5cm, width 18.5cm, depth 9.5cm, weight 2.591 kg.

Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Br 4467. Accession No. MNE 43.

Objects from the Louis de Clercq Collection (see the Antinous page)

were donated in 1967 to the Louvre and the Cabinet des Médailles,

Paris by Henri Louis de Boisgelin, nephew and heir of de Clerq.

Image source: monochrome héliogravure by P. Dujardin, in Anton de Ridder,

Collections de Clercq, Tome III, Les bronzes, No. 423, pages 268-269 and

planche LVIII. Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1905. At Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

| |

Small bronze figure of a winged Gorgon running/flying to the right.

Probably an attachment from the rim of a vessel, perhaps a tripod.

The base does not belong to the figure.

Around 525-500 BC. Acquired in 1868 in Cilicia, south Anatolia (today

southern Turkey), for the collection of Louis de Clercq (1836-1901).

Height 8.5cm, width 10.5cm, depth 2.3cm, weight 223g.

Musée du Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Br 4456. Accession No. MNE 32.

Objects from the Louis de Clercq Collection (see the Antinous page)

were donated in 1967 to the Louvre and the Cabinet des Médailles,

Paris by Henri Louis de Boisgelin, nephew and heir of de Clerq.

Image source: monochrome héliogravure by P. Dujardin, in Anton de Ridder,

Collections de Clercq, Tome III, Les bronzes, No. 329, pages 235-236 and

planche LIII. Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1905. At Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

| |

A Corinthian terracotta plaque in the form of a running/flying Gorgon.

6th century BC. Made with a pale, cream-coloured clay. Traces of red

colour can still be seen on her breast and left wing. Two holes in the

wings above the arms were for hanging or attaching the plaque.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 10185. |

| |

A terracotta plaque in the form of a running/flying Gorgon,

from the site of the Doric temple of Athena Agoriois (Αγοριοις)

at Prasidaki (Πρασιδάκι), Elis, western Peloponnese.

6th century BC.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum.

|

Like the Gorgoneion plaques from the same sanctuary below, the figure was made with a pale, cream-coloured clay. They appear to be mould-made, with very shallow relief, and were probably originally painted (a hint of red can be seen on the breast of this figure). Each depicts the Gorgon quite differently. The museum labelling stresses the association of the Gorgoneion with Athena and also with the Underworld: "The Gorgoneion is one of the characteristic emblems of Athena, with chthonic associations."

The head and body of this running/flying Gorgon are shown frontally, while the legs are in profile in the kneelauf position. Her hands, symmetrically positioned at waist level, probably held the ends of her (painted) snake belt (as on Gorgon figures above and below). The large wings spread behind her back, unusually not sickle-shaped, appear more like those of a bird (perhaps like those on the altar from Selinous above). She also has sickle-shaped wings on her ankles.

A similarly-shaped moulded terracotta plaque with a winged Gorgon in relief, 7.2 cm high, dated to around 480-470 BC, is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. Inv. No. T.25. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Two terracotta plaques in the shape of Gorgoneions, from the site of the Doric temple of Athena

Agoriois at Prasidaki (Πρασιδάκι), Elis, western Peloponnese. The form of the head of the broken

plaque on the left resembles that on a bronze hydria found at nearby Diasella (see below).

6th century BC. The two plaques are shown at approximately the same scale.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

A relief of a Gorgoneion on the base of a handle of an Archaic

bronze hydria. Either side of the Gorgon's head is a seated ram.

6th century BC. From Diasella (Διάσελλα), Elis, western Peloponnese.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum.

|

The Gorgon's face is not quite so hideous, she has a long, thin, unwrinkled nose, a row of six top teeth without fangs, a potruding tongue and pointed ear lobes. Two thick, shoulder-length locks of hair hang from behind each of her ears.

The locks around her forehead taper upwards and are bundled on top by a ring resembling a crown, around which can be seen five spheres. The ring also forms the lower end of the hydria's handle. The attachment of the handle to the vessel's body is strengthened by two metal strips extending horizontally from the sides of the head like antlers. At the end of each strip is a circle in relief, resembling the head of a nail or rivet. A relief of a ram facing outwards sits on top of each strip. It is difficult to tell if this arrangement has a symbolic significance or is merely decorative or functional, but it appears to have been copied on a small terracotta plaque found at nearby Prasidaki (see above). |

|

|

| |

A similar Archaic bronze hydria handle. The arrangement of the Gorgoneion

and rams is the same as on the hydria above. At either side of the top of this

handle are two seated lions. This combination of Gorgon, ram and lion can also

be seen on the roughly contemporary statue base in Delos (see above).

Made in a Laconian workshop. 7th - 6th century BC.

From Neraida (Νεράιδα), Elis, western Peloponnese.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Fragments of an Archaic marble statue of the winged Gorgon Medusa, reconstructed

as an akroterion (roof decoration) on the gable of a temple. It is thought that the

statue was set up above the entrance to the pre-Parthenon Athena temple on

the Athens Acropolis known as the Hekatompedon, built around 575-550 BC.

Reconstruction in the Old Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Acr. 701.

|

The reconstructed figure in the photo above used to be a prize exhibit in the Old Acropolis Museum until 2007, but may no longer exist in the new museum. Recent photos show the fragments of the Gorgon separately, and there is no mention of the reconstruction as an exhibit in the offical guide book, the museum's website or other recent publications. [2]

The story of the reconstruction may be remarkable (although not necessarily unusual), but the few mentions of it by historians and archaeologists are brief and vague.

A number of marble sculptural fragments were found in December 1888, southwest of the Parthenon. The well-executed, life-size head was evidently that of a Gorgon of the lion-mask type. A second fragment, with traces of paint, is not so well sculpted or detailed, and depicts what appears to be a belt tied with a Herakles knot, grasped by two hands, over one of which is part of a snake. Another fragment has parts of toes from a right foot attached to part of a slightly concave base with a low chequered relief. The marble was first thought to be Pentelic, but is now considered to be Hymettian.

Marble head of Medusa. Inv. No. Acr. 701.

Life-size. Height 28.6 cm, width 19.6 cm.

Marble belt fragment. Inv. No. 3798.

Width 25 cm.

Marble foot fragment. Inv. No. 3618.

On part of a broken baseplate,

height 15 cm, width 22 cm, depth 5 cm.

The oval shaped head of the Gorgon is shown frontally. The hair over the forehead is arranged in neat, scalloped waves parted at the centre. Above this is a taneia (band), and the top of the head is covered by a regular chequered pattern relief. The eyes, with incised pupils, are set deep beneath ridged brows and above full, rounded cheeks. The nose is wrinkled by four horizontal grooves. The wide, grimacing mouth has ridged lips, upper and lower fangs at each end, among regular rows of teeth, and a flat, tongue potruding over a broad chin. The ears are placed high, flat against the sides of the head.

The style and carving technique of the head have been compared to those of the famous "Moschophoros" (Calf Bearer) statue from the Athens Acropolis, which has been dated to around 570 BC (see photo, below right).

During the mid to late 19th century archaeological excavation on and around the Acropolis was at its most intensive phase, with the discovery of an enormous number of artefacts and fragments. Sorting, conserving, storing, examining, analysing and identifying the objects were enormous tasks, and many still await detailed study.

Archaeologists were eager to trace the history and evolution of the Acropolis and identify the remains of ancient buildings and monuments, some of which had survived only as architectural fragments or traces of foundations. To a great extent they had to rely on mentions of them by ancient authors, and several conflicting theories developed, some of which remain subjects of debate.

Two monumental temples of Athena were thought to have been built on the Acropolis during the Archaic period, before the Classical Parthenon, the identification and history of which are still being debated. The first may have been the temple referred to by ancient authors as the Hecatompedon (ἑκατόμπεδος, Hekatompedos, hundred-footer), although the length of the building may not have been exactly 100 Attic feet (32.8 metres). It has been also referred to by modern historians as the "Parthenon 1", "UrParthenon" (primal Parthenon), "Bluebeard temple" or, less romantically, "Building H". It is thought to have been built around 570-550 BC (later according to some theories), and has been associated with the establishment of the Great Panathenaia festival in 566/565 BC, during the archonship of the aristocrat Hippokleides. Several sculptures from this temple are now in the Acropolis Museum.

The first temple was replaced by the "Pre-Parthenon" or "Parthenon 2", which was under construction around 488-480 BC, but had not been completed by the time of the Persian invasion of Xerxes in 480-479 BC, when the buildings on the Acropolis were burnt down (see a model of the Acropolis as it may have appeared in 480 BC on Athens Acropolis gallery page 2).

The German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940) took a particular interest in the pre-Parthenon temples of Athena, and excavated the foundation of a building he believed was the Hekatompedon. The foundation was named the "Dörpfeld foundation" (or "Dörpfeld temple") after him. [3]

Meanwhile, the Gorgon fragments had been placed in the recently-built Acropolis Museum (the old museum on the Acropolis, completed 1874, with an extension built in 1888). It seems no connection had been made between them, and the two largest (the head and belt) were kept on different shelves. [4]

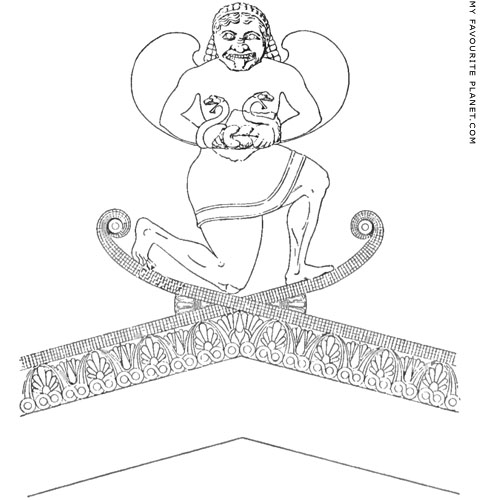

The German archaeologist Johann (Hans) Hermann Schrader (1869-1948), working on the excavations at the Acropolis under Dörpfeld, had been given the task of processing sculptural finds. Based on a handful of small, apparently disparate fragments and the conclusions of other archaeologists (Dörpfeld, Theodor Wiegand) he set about attempting to reconstruct the Gorgon and a marble panther (or leopard) as part of the gable end of the roof of the Hekatompedon. [5] The result of his work is the reconstruction above, showing a running/flying Gorgon in the kneeling position, on the apex of the gabled roof (see Shrader's drawing below).

His bold efforts received encouragement from colleagues at the time [6], and the reconstruction was evidently considered convincing enough to have been exhibited in the museum for many decades. Although there appear to have been no published criticisms of the piece, it is notable that it has ignored by several books on the Acropolis and the museum. Such adventurous reconstructions of ancient sculptures had been de rigeur since the Renaissance, especially in Italy. However, by the end of the 19th century they were frowned upon by more scientific archaeologists, and mostly avoided in Athens.

See photos and articles about the Parthenon

on Athens Acropolis gallery pages 13-17. |

The head and belt fragments of the

reconstructed Gorgon akroterion. |

| |

The head of the Acropolis Gorgon.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 701. |

| |

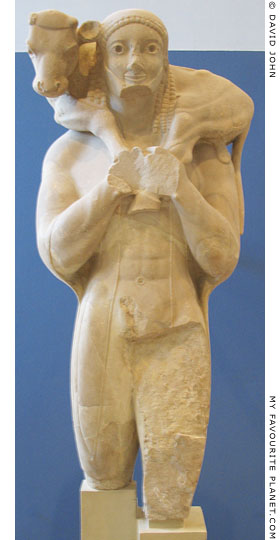

The "Moschophoros" (Calf Bearer)

statue dedicated by a certain

Rhombos on the Athens Acropolis.

About 570 BC. Hymettian marble.

Found in 1864 during the digging

of foundations for the (old) Acropolis

Museum. The base and feet were

found in 1887 in same area.

Restored height 165 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 624. |

| |

| |

Hans Schrader's reconstruction drawing of the Gorgon Medusa

on the roof of the Hekatompedon [see note 5 for source]. |

| |

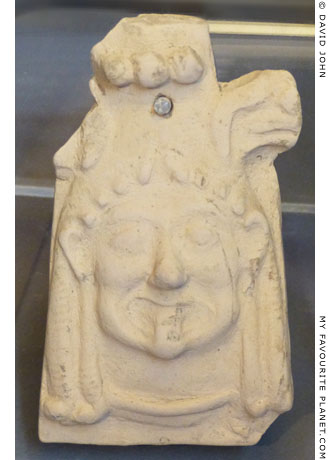

Fragment of a painted terracotta figure of a Gorgon

from Megara Hyblaea, Sicily. Circa 500 BC.

The top part of a Gorgon figure with a Daedelic hairstyle. Her hands grasp

a belt in the same way as the "Hekatompedon" Gorgon above. The hole

under her right arm suggests that it was part of a plaque nailed to a building.

Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily. |

| |

Fragment of a large terracotta plaque in the form

of a running/flying Gorgon in the "Knielauf" position.

Probably an akroterion (roof decoration) from a building.

Around 500 BC. From Gela, Sicily. Height 57 cm, width 42 cm.

Berlin State Museums (SMB). Inv. No. Tc. 140.

Source: Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz, Die antiken Terracotten,

Band II, Die Terracotten von Sicilien, Fig. 95, page 44. W. Spemann,

Berlin & Stuttgart, 1884. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

A modern ceramic pinax (plaque) with a relief of Medusa (right), made from an ancient mould (left).

Second half of the 6th century BC. From Akragas (Ἀκράγας, today Agrigento), Sicily.

Three of the Gorgon's four sickle shaped wings are visible. The figure has

a "lion-mask" head, a short chiton and winged boots, and runs/flies in the

"Knielauf" position. As in the "Hekatompedon" Gorgon and the Megara

Hyblaea figure above, both her hands grasp a belt made of snakes.

Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum, Syracuse, Sicily. Inv. No. 48096. |

| |

Another Medusa pinax relief from an ancient mould from Akragas, Sicily. 6th century BC.

The moulds were found during excavations directed by Pirro Marconi and Pietro Griffo

in and around the Sanctuary of the Chthonic Deities (underworld gods), where traces

of kilns from pottery workshops connected with the sacred area were discovered.

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum. Inv. No S 16. |

| |

|

|

|

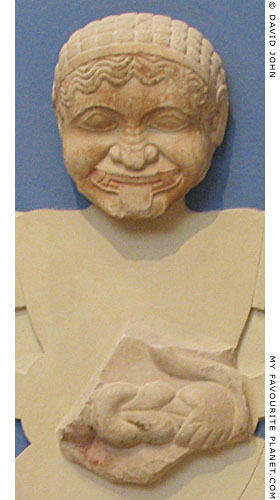

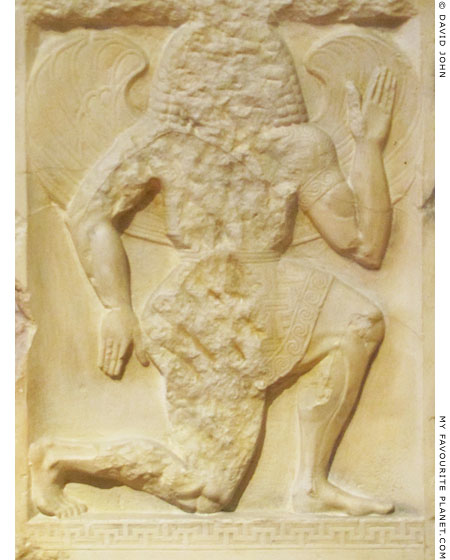

A relief of a winged Gorgon on a marble grave stele, shown in

the kneeling posture that signified rapid motion in Archaic art.

Made of island marble, about 560 BC. From Kerameikos, Athens.

Height of stele 239.5 cm, width 43.5 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 2687.

|

|

The stele, often referred to as the "Gorgon Stele", was found in 1905 in Kerameikos, built into the Themistoklean Wall (built 478 BC). In the main panel is a relief of a slim, young man in profile, facing right, carrying a staff or spear. The Gorgon is in the register below. The figures had been hammered before being fitted into the wall. It is displayed in the museum next to a plaster cast (photo, right), restored with a capital and a crouching sphinx on top.

A number of such tall, slim Archaic grave steles are known to have been made in Athens and Attica around 600-530 BC, and at other places such as Thessaly. One of the best preserved, the "Brother and Sister stele", also topped with a sphinx, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [7]. Part of another 6th century BC Attic marble stele, dated to circa 550-525 BC, in the Metropolitan, known as the "Kalliades Stele", also shows a running/flying Gorgon [8]. The sphinxes, lions, Gorgons and (later) sirens on the steles are thought to have been apotropaic protectors of the graves, perhaps reflecting the Egyptian tradition.

The Gorgon has been very carefully sculpted, with fine detailing. The thickly braided hair is reminiscent of earlier artworks of the "Daedalic Period" (650-600 BC), but the anatomical details and modelling are now much more sophisticated. Some scholars have associated the sculptural style of the stele reliefs with those of Phaidimos (active around 560-540 BC) and the Rampin Master (sculptor of the "Rampin Horseman" around 550 BC).

The figure, in the "Knielauf" position, wears a short chiton (tunic) covered with a geometrical pattern, and the bands around the collar and short sleeves are decorated with continuous spiralling (see drawings, right). The body is muscular, with the thick thighs typical of Archaic sculpture, particularly of depictions of Medusa, and the artist has made an effort to show the weight and forms of flesh, muscle and bone. The feathers of the upraised, sickle-shaped wings are separated by ridged contours.

The Gorgon' face is missing, but she probably had the usual "lion mask" features shown on other depictions of her from the late Archaic and early Classical periods, as on the coins and the head of Medusa from the Athens Acropolis above, and on the "Kalliades Stele". |

Reconstruction drawing showing the

patterns on the "Gorgon Stele". |

| |

Reconstruction drawing of the maeander

pattern on the Gorgon's chiton.

Source of images:

F. Noack, Die Mauern Athens, in Mitteilungen

der kaiserlich deutschen Archäologischen

Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band XXXII,