| Medusa |

The Gorgon pediment in Corfu |

|

|

|

The reconstructed Gorgon pediment from the west facade

of the "Temple of Artemis", Corfu. Circa 585 BC.

Local greyish poros (limestone) with traces of paint.

Height 3.18 metres, length 17.03 metres.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. [1]

|

Ancient Korkyra

Corfu (Κέρκυρα, Kerkyra; Ancient Greek, Κόρκυρα, Korkyra) is the nothernmost and second largest of the seven main Ionian islands along the coast of northwestern Greece and Albania, and has been an important stopping point on the sea route between Greece and Italy since prehistory. Around 734 BC Corinthian colonists drove out the inhabitants, who were either Eretrians from Euboea who had settled there earlier in the century, or Liburnians from Illyria on the mainland opposite. [2] This was at about the same time as the Corinthians are said to have founded Syracuse on Sicily (see Demeter).

Difficulties in the relationship between the colonists on Korkyra and their metropolis (mother city) Corinth led to war in 665/664 BC and the earliest recorded sea battle between Greek city states (Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 1, chapter 13). The islanders won and for a while became independent. Korkyra was controlled by Corinth again during the rule of the tyrant Periander (Περίανδρος) around 627-585 BC, but some time after regained independence.

The city of Korkyra was built on a hilly headland, today known as the Kanoni peninsula (η χερσόνησος του Κανονιού), on the east coast facing the mainland, 2.5 km south of the modern city centre. To its west is a narrow-mouthed lagoon, known as Hyllaikos (Υλλαικος, later named Lake Chalkipoulos, λίμνην Χαλκιοπούλο), which was used as the city's main harbour, and there was a smaller military port in the semicircular Alkinoos harbour (Αλκίνοους, now land-filled), in the wide bay (today Garitsa Bay) to the north of the city.

Remains have been found of the city walls, a defensive tower, the agora, baths, and temples and sanctuaries thought to have been dedicated to Hera, Apollo, Dionysus, the Dioskouroi and Artemis, as well as a smaller Artemis sanctuary further to the southwest. Much of the area of the ancient city, today known as Palaiopolis (Παλαιόπολης, Old City), is within Mon Repos, once the estate of the 19th century British governor of Corfu and now a wooded park. The former governor's residence now houses archaeological finds from the area, while many others are in the Corfu Archaeological Museum.

Despite Corfu's size and its assumed political and economic importance in Antiquity, there are surprisingly few archaeological sites across the island, and little published information about those that are known. Relatively few inscriptions or other direct historical evidence have so far been discovered here. Many ancient sites may lie beneath towns, villages, woods and fields, as well as in areas now below sea level, and much has inevitably been destroyed by time, but there is no doubt much still to be unearthed.

The "Temple of Artemis"

The Doric temple now known as the "Temple of Artemis" was built of local poros limestone around 590-580 BC, probably during the rule of Periander, in the northwestern area of the city, today next to the Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias (η ιερά μονή Αγίων Θεοδώρων Στρατιάς, the Holy Monastery of Saint Theodore the Recruit) in the suburb of Garitsa (Γαρίτσα), 2 km south of the modern town centre, and around 450 metres west of the entrance to the Mon Repos estate.

For information about the site of the temple and the monastery, see below.

It is the earliest known Greek temple to have beeen built of stone and to have incorporated all the architectural elements of the Doric style, and the Gorgon pediment is the earliest known example of stone pedimental sculpture. (Compare this, for example, to the temple of Apollo at Thermon, Aetolia, central Greece, built of wood with ceramic decoration around 630-620 BC, just a generation earlier.) The architect and sculptor(s) may have been Corinthians, but there is no direct evidence for this (see the note in part 2 for Corinth and Gorgons on temples). The rectangular building was oriented on an east-west axis, with its entrance at the east end. It was 22.40 metres wide and 47.89 metres long, and around 14 metres high, and its roof is thought to have been suppported by 8 columns at each end and 17 along the sides.

Today only its foundations remain, as well those of surrounding buildings and an 8 metre long section of a rectangular altar, originally 25 metres long and 2.7 metres wide, to the west of the temple (see photos below). Most of the stones from the sanctuary were later reused elsewhere, particularly in the construction of the Monastery of Agios Theodoros. The Byzantine katholikon (main church) was built in the 5th century AD, and the monastery was renovated and expanded in the 16th century, then renovated again in 1815. Surviving architectural members as well as other archaeological finds from the temple have been taken to Corfu's two museums.

Remains of the temple were first discovered during the Napoleonic Wars by French soldiers as they were constructing fortifications in 1812-1813. [3] This was apparently forgotten until December 1910, when farmers showed Theodoros Politis (Θεόδωρος Πολίτης), a local professor, "ancient stones" they had found while digging in the field west of the monastery. The stones would turn out to be parts of the Gorgon pediment. Following a local press report Greek authorities were informed of the discovery, and soon after the local curator of antiquities Ioannis Marmoras (Ιωάννης Μάρμορας, the first curator of the recently-built Corfu archaeological museum), made a limited excavation of the site.

In the same month the young Greek archaeologist Friderikos Versakis was appointed as ephor of antiquities for the area including Corfu, and in January 1911 he was ordered to examine the site. After waiting for some time to receive the necessary funding from the Archaeological Society of Athens, he began excavating the temple on 13th March. Within a few days he had unearthed most of the fragments of the Gorgon pediment, including a lion's head, as well as the head, body and a leg of the Gorgon. Following these discoveries the building became known as the "Gorgo Temple".

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, who had arrived in Corfu to spend the Easter holiday in his nearby Achilleion palace, began visiting the site and took an increasing interest in the excavation. He summoned the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld to the island. However, there had been a history of professional and political antagonism between Dörpfeld and Versakis, and by 22nd April the latter had been replaced as ephor by Konstantinos Rhomaios (Κωνσταντίνος Ρωμαίος), and Dörpfeld was put in charge of the dig (see further details on the Friderikos Versakis page). Dörpfeld has consequently - and incorrectly - been given most of the credit for the discoveries at the sanctuary. The work was continued by German archaeologists until April 1914, and resumed in 1920, after the end of the First World War.

It had become clear early on that not much of the temple remained, and at the time little was known about the history or ancient geography of Korkyra, with almost no clues provided by ancient literature and few surviving inscriptions or other evidence. The identity of the deity for whom the "Gorgo Temple" was built remained a mystery. However, in April 1914 a prismatic limestone stele with part of a short inscription was found to the north of the temple, built into a later wall (see photos, right and below). Dörpfeld speculatively added the missing letters so that it read as a dedication to Artemis by a woman named Mentis, daughter of Aristeas:

Μ]έντις Άρυτέα Άρτάμιτι

Mentis, daughter of Aristeas, to Artemis.

Inscription IG IX 1, 4, 852

Dörpfeld took this to be proof that the temple must also have been dedicated to Artemis [4], and on this slim evidence it has since been known as the "Temple of Artemis". It was later recalled that the French had discovered another inscription with a dedication to Artemis in 1813, although the exact findspot is far from certain. [5]

See also part of an Archaic pediment relief with a symposium scene thought to depict Dionysus, found on the Kanoni peninsula, Corfu. |

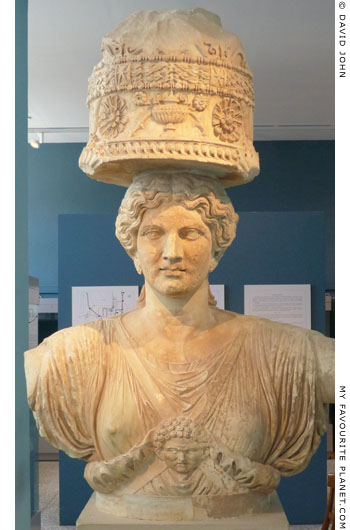

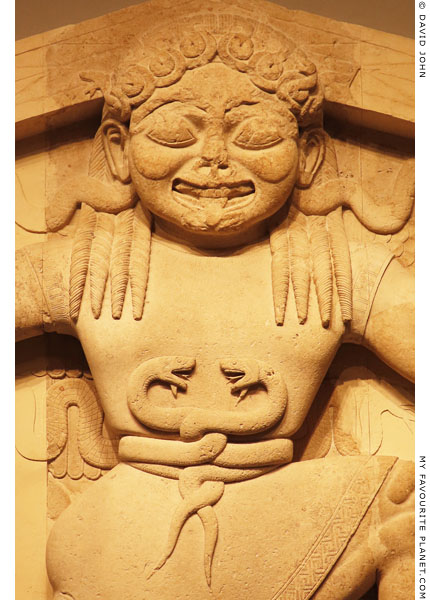

One of a large number of terracotta figurines

thought to depict Artemis, found in a deposit

at the southwest end of the Kanoni peninsula,

Corfu, excavated in 1889 by Henri Lechat of

the French Archaeological School at Athens.

The site is believed to have been a small

sanctuary of Artemis. [6] This partially

reconstructed figure wears a polos and

a peplos. She has a bow in her left hand,

and with her right hand holds a lion by

one of its hind paws in the manner of

depictions of the Mistress of Animals.

Late 6th - early 5th century BC.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A triangular limestone votive stele inscribed with

a dedication to Artemis (see close-up below).

3rd century BC. Found built into a later

analemma (ἀνάλημμα, retaining wall)

north of the "Temple of Artemis" during

Wilhelm Dörpfeld's excavation in April 1914.

Height 73 cm, width of sides 33 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

The stele is exhibited in the Gorgo Hall of the

museum, near the Gorgon pediment, but no

information is provided about its history or

findspot. The round socket at the top of the

stele was for the attachment of a column on

which the votive offering stood. This was

found with the stele and is displayed next

to it in the museum. Height of column base

47.5 cm, width 43.5 cm, depth 34.5 cm

(the rear is broken). |

| |

| |

The top of the triangular stele with a two-line inscription, thought to be a dedication to Artemis.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

|

The centre of the top and the top-right edge of the stele apparently broke off and were lost some time after its discovery. The surviving letters of the inscription appear to read:

— Ε ——— Σ ΑΡΙ —

— Σ ΤΕΑ- ΑΡΤΜΜ —

Günther Klaffenbach, who studied a squeeze of the inscription, made before it was damaged, ascribed the discrepency between the lettering and Dörpfeld's reading of Άρτάμιτι (ΑΡΤΑΜΙΤΙ, Artamiti) to the stonemason's clumsy attempt to correct an error. He read the inscription as:

[.]εντις Ἀρι–

στέα Ἀρτάμ<ι>τι.

"Das letzte Wort ist verschrieben. Wie der alte Abklatsch deutlich zeigt, hatte der Steinmetz zuerst APTMITI eingehauen. Er hat dann das M in A verbessert, aus dem folgenden I ein M gemacht und dann nur das T, nicht auch das vorhergehende I, von neuem eingehauen, so daß nun die neue fehlerhafte Schreibung APTAMTI entstand."

"The last word is written incorrectly. As the old squeeze clearly shows, the stonemason had first struck APTMITI. He then corrected the M to A, made from the following I an M, and then rechiselled only the T, but not the previous I, so creating the faulty text APTAMTI."

Günther Klaffenbach, III. Die Inschriften, No. 2, pages 163-164. In: Gerhart Rodenwaldt (editor), Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker, Band 1, Der Artemistempel: Architektur, Dachterrakotten, Inschriften. Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 1940. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. [7] |

|

| |

A reconstruction drawing of the west facade of the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu by Hans Schleif.

For the pediment sculptures Schleif used a reconstruction drawing by J. Hannover as a basis.

According to the reconstruction the pediment sculptures were carved on seventeen contiguous

limestone slabs, with the Gorgon's head and torso taking up most of the central ninth slab.

Substantial fragments of ten slabs and a small fragment of an eleventh have been discovered

and were used in the restoration of the pediment in the Corfu Archaeological Museum.

Source: Gerhart Rodenwaldt, Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker,

Band 2, Die Bildwerke des Artemistempels, Tafel 1. Archäologisches Institut

des Deutschen Reiches. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 1939. [see note 7] |

| |

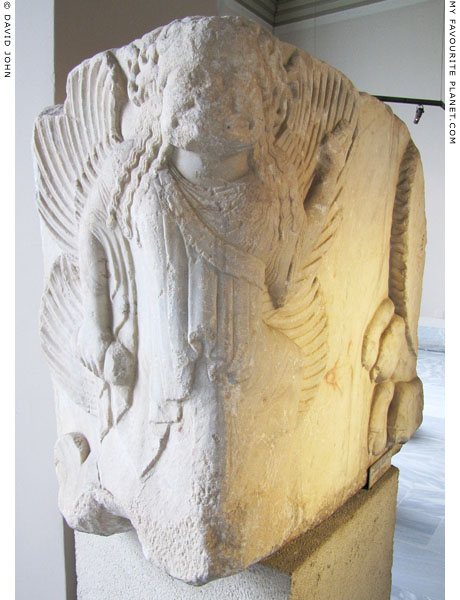

The Gorgon Medusa flanked by two lions (also referred to as panthers, lion-panthers or leopards)

and fragments of the figures of her children on the Gorgon pediment in Corfu. On the left are the

rear legs and part of the wings of Pegasus, and on the right the head and torso of Chrysaor.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

|

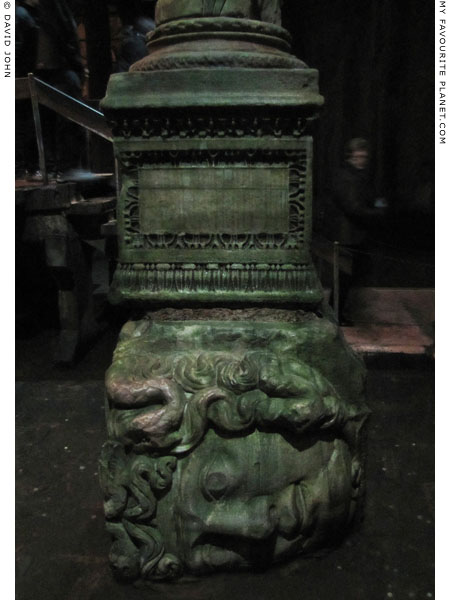

The Gorgon pediment

At around 2.79 metres high, this is by far the largest ancient Gorgon figure yet discovered, although not the largest scale depiction (see, for example, the colossal head in Veria and the Gorgoneion reliefs in Didyma and Istanbul). Her head is 81 cm in height, and the face, from forehead to chin 59 cm.

The figure has been reconstructed from several fragments, from which it is clear that she was originally shown as winged, her head and body facing frontally, running/flying to the right in the "Knielauf" position, with snakes extending from either side of her neck and waist. The remains of the scaly feathers of her wings can be seen behind her left arm and below her right armpit. Unfortunately, her lower left arm and hand and her right hand are missing, so it is not possible to know if she was holding something or touching her children, Pegasus and Chrysaor, shown to the left and right of her. Just below the calf of her muscular left leg, the top of her high boot or sandal is marked by an ornate band, from the front (right) of which sprouts a small, sickle-shaped wing (see photo below), reminiscent of a cockade.

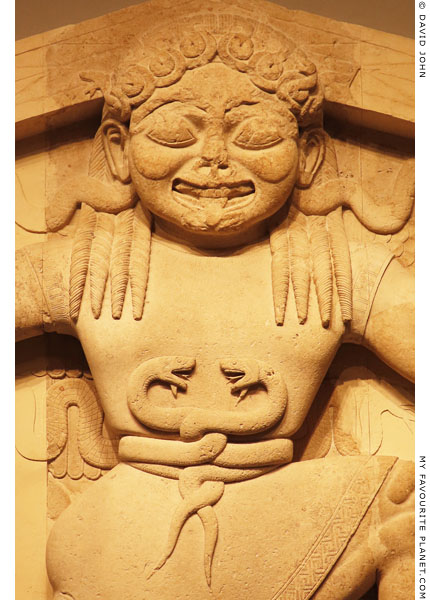

Her head and face are of a type similar to those of Gorgon reliefs from Sicily (the plaque from Syracuse and the altar from Gela, but especially the metope from Selinous) made around the same period, late 7th - 6th century BC. However, like each of the other reliefs, the Corfu Gorgon is a unique and powerful work of art.

The almost circular face is framed by single row of eight spiral curls in the form of coiled snakes over a headband around the forehead, and four tapering braids hanging from behind each frontal ear down to each breast. Above the headband the hair over the crown of her head is shown as neat groups of vertical grooves and ridges. Two thick, curved ridges form the eyebrows above the large, prominent eyes which have incised irises. Most of the nose has been destroyed, but the deep, wide nostrils can still be seen. She has high cheekbones above an oval grinning mouth, with thinly ridged lips and a lolling tongue. The rows of top and bottom teeth are regular; if she originally had fangs (perhaps hanging from the top row of teeth) they have not survived. The space between the rows of teeth has been carved deeply. The raised oval chin is damaged. As in the Sicilian reliefs and the akroterion from the Athens Acropolis, she has no "beard".

She wears a short-sleeved chiton (tunic) with decorated bands around the neck, sleeves and hem. The detailed meander pattern around the hem has been precisely sculpted (see photo below). Around the slim waist is a girdle of two snakes, entwined at the centre, their heads raised and confronting each other (in what is is often described as a heraldic manner), their tails cross then hang together below the waist. All three surviving snakes' heads have pointed beard-like protuberances hanging from below the jaw (see photo, below right), similar to antefixes in Olympia and a mosaic in Ephesus. "Bearded snakes" appeared in Greek and a little later Etruscan art during the the Archaic period, usually in mythological imagery (e.g. Herakles fighting the Lernaean Hydra), and they appear to have had no special association with Gorgons. [8]

Only the hind legs and part of the wings of Pegasus have survived (see photos below), as well as part of a front leg and hoof resting on top the Gorgon's right upper arm. It is therefore difficult to draw comparisons with other representations of the winged horse. It is notable that its flanks appear rather flat in comparison to the other, more rounded figures of the pediment.

Of Chrysaor, the head and torso with most of the left arm have survived (see photo below). When first discovered, no other Archaic sculpture of Chysoar was known, and the figure was thought to be Perseus about to kill Medusa, even if his small size compared to the Gorgon was puzzling. Inevitably, since there are still few known depictions of the hero, this figure can only be compared to the headless Chrysaor on the Gela altar (discovered in 1999). He is much more realistic, with well-developed musculature, particularly the pectorals, and individualized facial features, and appears more convincing than Daedalic sculptures of two generations or so earlier, and even some contemporary kouros statues.

Since Medusa is shown on the pediment still alive (rather than decapitated) with her children Pegasus and Chrysaor as well as wild animals, it has been suggested that the figure may actually represent Artemis "in the figure of Gorgo, as the Πότνια Θηρῶν" (Potnia Theron, the Mistress of Animals).

This theory has been mentioned by a number of writers [9], and Wilhelm Dörpfeld went as far as to exclaim "Gorgo and Artemis are the same goddess" [see note 4]. However, I have yet to see it being thoroughly discussed or rigorously tested. At present, it certainly seems difficult, if not impossible, to prove. Although there does appear to have been some kind of connection between the Gorgon, Artemis and the Mistress of Animals, at least in art (see, for example the plate from Kamiros in Medusa part 2), little is known about the relationship between these three entities in mythology or religion. Questions concerning the part played by lions or other large felines in the iconography of all three also remains moot. Medusa is shown with both her head and her children in other Archaic works (a tripod leg in Olympia, the Syracuse plaque, the Selinous metope, the Gela altar), and she is even depicted riding Pegasus.

There also remains the question of the identification of the deity for whom the temple was built. Although the hypothesis that it was dedicated to Artemis has been generally acepted, this is based on the thin evidence of two dedicatory inscriptions which may not have been connected with the temple or even the sanctuary.

It has been suggested that the Gorgon iconography may be more suitable to Athena, but this too would be difficult to prove. Although the fragments of the Gorgon akroterion from the Athens Acropolis are thought to be from Hekatompedon Athena temple (built a decade or two after the Corfu temple), this has not been established beyond doubt. The Syracuse plaque was found in the area of the Athena temple, but there was also an Artemis sanctuary nearby. The identity of the deity worshipped at Doric Temple C in Selinous, which had a large Gorgoneion in the centre of the pediment, is unknown. Gorgon imagery is also known from sanctuaries of other deities, including Demeter, Hera and the Chthonic deities, as well as temples of Apollo, for example at Thermon, Delos and Didyma. A Gorgoneion also appears in the pediment of a temple on reliefs associated with Dionysus (see an Ikarios relief on the Dionysus page).

The appearance of Medusa on the Corfu temple need not necessarily have been directly connected to the deity worshipped there [10]; it may have had more to do with the apparent surge in popularity of the Gorgon myth in the Archaic period. Artists and their public may have been excited to see her with her children, without bothering too much about the order of events in the tale. The apotropaic power of Medusa's image, along with the presence of two powerful "lion-panthers" may have been believed to provide supernatural protection for the temple. The fact that Pegasus and Chrysaor appear to be standing between the forepaws of the cats may suggest that they were guarding the children. It would probably be too far-fetched to suggest that somehow the cats were meant to represent Medusa's two sisters.

Alternatively, there may have been versions of the myth in which Medusa gave birth to her children before her death, or perhaps she was simply known to have been their mother before the addition of the story in which they sprang from her body after Perseus decapitated her.

The pediment also included smaller reliefs depicting war scenes from Greek myths (see photos below). One of the three surviving reliefs is thought to show Zeus killing a Giant (the realm of the gods), and another King Priam of Troy being killed by the Greek warrior Neoptolemos (the realm of men). Neither scene has direct associations with the Artemis cult, or for that matter the mythological histories of either Korkyra or Corinth. |

The Gorgon Medusa on the Gorgon pediment in Corfu. |

| |

Detail of the Gorgon Medusa on the Corfu Gorgon pediment. |

| |

Entwined bearded snakes form the Corfu Gorgon's girdle. |

| |

The meander pattern of the hem of the Corfu Gorgon's

chiton above the left thigh. |

| |

| |

The Gorgon family group flanked by two crouching "lion-panthers" in the centre of the Gorgon pediment in Corfu.

Left of the Gorgon are the rear legs and wings of Pegasus, and to the right the head and torso of Chrysaor. |

| |

The head, torso, left arm and part of the left foot of Gorgon's son Chrysaor on the

Gorgon pediment. Height of figure around 170 cm, height of head around 26.5 cm.

To the left, part of the Gorgon's left leg with high footwear and a sickle-shaped wing. |

| |

The crouching "lion-panther" on the left of the Gorgon pediment in Corfu.

To the right, the rear legs and part of the wings of Pegasus.

|

| Only the head of the other cat to the right has survived, and is very similar but not identical to this one. Although far from realistic, the figure has been sculpted with great care and attention to details, and it has a powerful presence. It has a neat, trim mane, deep-set eyes and like many Gorgon heads it has a wrinkled nose, above which are two raised round dots. Subtle carving indicates its shoulder and ribcage, although the musculature of the legs has a rather blocky geometric appearance, as if it is wearing greaves (shin armour). Its torso and flanks are covered with an almost regular pattern of dots surrounded by three concentric circles, similar to the pattern of circles on the panther from the Archaic Hekatompedon pediment on the Athens Acropolis, made a few decades later (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 13). |

|

| |

The so-called "Lion of Menekrates", a limestone statue of a crouching lion, probably from a funerary

monument. Formerly thought to have stood on top of the Monument of Menekrates, near to which

it was discovered in October 1843 in the Garitsa district south of Corfu town centre.

From Corfu town (Kerkyra). Probably made by a Corinthian sculptor, around 600 BC,

about a generation or two before the Gorgon pediment. Length 122 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

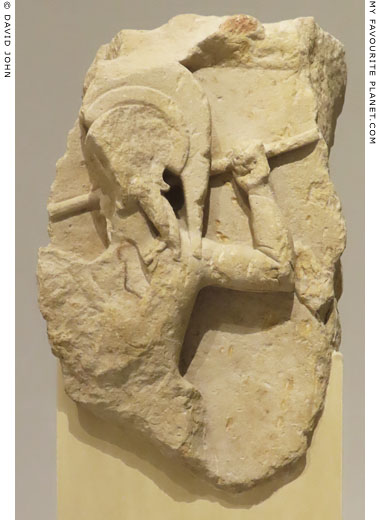

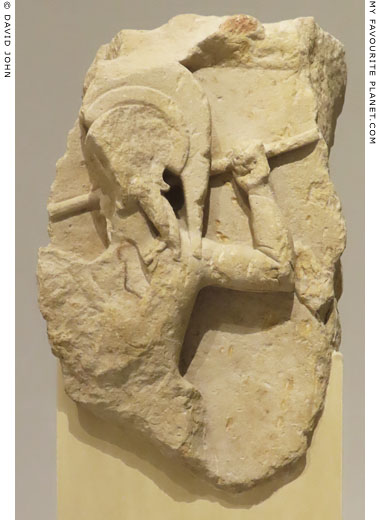

The three surviving limestone reliefs representing mythological scenes on

the Gorgon pediment in Corfu (all shown to approximately the same scale).

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

|

Left: A dying or dead male with a long chin beard in the left (north) corner. An early attempt by the sculptor(s) to solve the problem of filling the confining space of a triangular pediment with figures.

Centre (to the left of the lions and Gorgon): A seated male with raised left hand, and the tip of a spear apparently coming towards him. Thought to depict King Priam of Troy being killed by Neoptolemos at the end of the Trojan War (see Homer part 2), or Poseidon killing a Giant in the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympian gods and the Titans.

Right (to the right of the lions and Gorgon): Two naked males in combat. The kneeling, bearded figure on the right is larger than his opponent, who appears to be winning the fight. Perhaps Zeus (left) killing a Giant with a thunderbolt in the Titanomachy. |

|

| |

A fragment of a limestone slab with a relief of a warrior

(described by the museum labelling as a "hoplite"),

found near "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu. Perhaps part

of a metope or frieze from the first building phase of

the temple, circa 590-570 BC.

Height 73 cm, width 46 cm, depth of relief 10.5 cm.

The figure, viewed from behind, faces left with his

head in profile. He wears a crested Corinthian helmet

and aims a spear in his raised right hand. The scene

of Achilles fighting Memnon during the Trojan War (see

Homer part 2) has been suggested as the subject.

To the right of his elbow is part of the right hand of

another figure. Since Memnon is thought to stand to

the right of Achilles in other depictions of the duel,

with the combatants flanked by their respective

mothers, the warrior may be Memnon and the hand

that of his mother Eos.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1982. |

|

A limestone male head, found to the east

of the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu on

13th May 1911. Perhaps from the east

pediment. Circa 590-570 BC. Height 15 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 434.

Only a few fragments thought to be from the

temple's eastern pediment have been found,

from which it is believed that the composition

of its sculptural decoration may have been

similar to that on the west pediment. |

|

| |

Terracotta sima fragments with relief decoration and traces of colour from

the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu. First building phase, 590-570 BC. Left,

from the narrow sides of the roof. Right, from the long sides of the roof.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Marble architectural parts from the superstructure of the "Temple of Artemis", Corfu.

Second building phase, end of the 6th century BC.

Above, Marble palmette antefixes and pan tile from the the long sides of the roof.

Below, parts of the marble sima from the narrow sides of the roof.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The site of the "Temple of Artemis" in Garitsa, south of the centre of Corfu town.

To the west (background, left) stands the Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias.

|

The site of the "Temple of Artemis"

The long strip of land forming the site stretches west to east from the east end of the Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias (η ιερά μονή Αγίων Θεοδώρων Στρατιάς), which can be seen in the background, left (see also photo below). It lies around two metres below the level of the modern road which runs along its north side. Rows of stones mark the foundations of the temple, which now lie beneath soil and grass.

It is not usually open to the public, but can be viewed from the roadside though the surrounding railings. Unfortunately, trees and bushes growing around the site can obscure the view in summer. Following the most recent archaeological investigations, the site was tidied up and landscaped during a project in 2000-2006. Since then not a lot seems to have happened there. The site still appears to be maintained and the grass around the temple kept short. An information board at the gateway to the site, next to the monastery, provides basic information about the temple's history.

During my visit the monastery church was also closed, and I did not succeed in discovering when it was open. There was not a soul around, not even a tourist. It appears that since there is so little to see here, the only visitors are those with a particular interest in history and archaeology.

It is not easy to find the temple. There are no signposts to the site from the city centre or the entrance to Mon Repos. One signpost to the monastery has been spray-painted with graffiti, and is anyway hidden by tree branches. Once you are there, there are signposts at each end of the site, likewise obscured by vegetation (and spiders webs, see photo, right). Tourist maps of Corfu town, including those in guide books, end just south of the city centre and do not include the site or Mon Repos.

The monastery and the temple are marked on Google Maps, but names of streets and places are often abbreviated. If you ask local people for directions to "Ag. Theodoron" you will naturally be met by puzzled stares, just as you would if you asked the way to "Oxford St." in London.

Directions to the site

The Mon Repos estate is 2.5 km south of the centre of Corfu town. Around 30 minutes walk. The local buses around the town are known as blue buses. No. 2a from San Rocco Square in the town centre to Kanoni, around every 30-40 minutes, stops outside the entrance gate to Mon Repos.

From the bus stop directly opposite and over the road from the Mon Repos entrance, Odos Dairpfeld (Οδός Δαίρπφελδ, Doerpfeld Street) begins to the right of the early Christian basilica (on the corner) and heads northwest. After around 200 metres turn left onto Odos Agion Theodoron (Οδός Αγίων Θεοδώρων). The way to the monastery is signposted on the corner of the two streets but, as mentioned above, it is covered by graffiti and is obscured by vegetation. The monastery and the "Temple of Artemis" are on the left after about 250 metres.

If you are walking from the town centre, take Odos Theodorou Desylla (Οδός Θεοδοροu Δεσύλλα) southwards, then after about 350 metres turn right onto Odos Agion Theodoron.

Odos Dairpfeld and Odos Theodorou Desylla are the same suburban street, but the name changes at the intersection with Odos Theodorou Desylla. At its northern end, at the south end of Garitsa Bay, it begins from Odos Vlachernon (Οδός Βλαχερνών), which runs east-west from Odos Dimokratias, the main road along the bay. A pleasant walk.

An information brochure about blue buses in Greek, German and English, with a basic route map, as well as printed timetables and tickets, are available from the kiosk at the blue bus station at San Rocco Square. You can also buy your ticket from the bus driver. Ask to be let off at Mon Repos. |

The remains of the altar to the west of the "Temple of Artemis". |

| |

A roadsign at site of the "Temple of Artemis". |

| |

Odos Dairpfeld (Οδός Δαίρπφελδ, Doerpfeld Street), named

after the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld, near

the "Temple of Artemis". |

| |

| |

The western end of the site of the "Temple of Artemis", and the Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias.

On the far left is the katholikon (church) of the monastery, the remaining part of the Byzantine basilica

built in the 5th century AD, using stone from the temple. The monastery was renovated and expanded

in the 16th century, and renovated again in 1815 by Sir Thomas Maitland, the British governor of the

Ionian Islands. An inscription over the church door commemorates the renovation. In front of the

monastery is the gate to the site and a wooden walkway down to the level of the sanctuary.

Below the monastery buildings, at the western end of the archaeological site, is the surviving 8 metre

long section of the sanctuary's limestone altar, sculpted all around with reliefs in the form of triglyphs

and metopes. It is estimated to to have been originally 25 metres long and 2.7 metres wide. |

| |

| Medusa |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

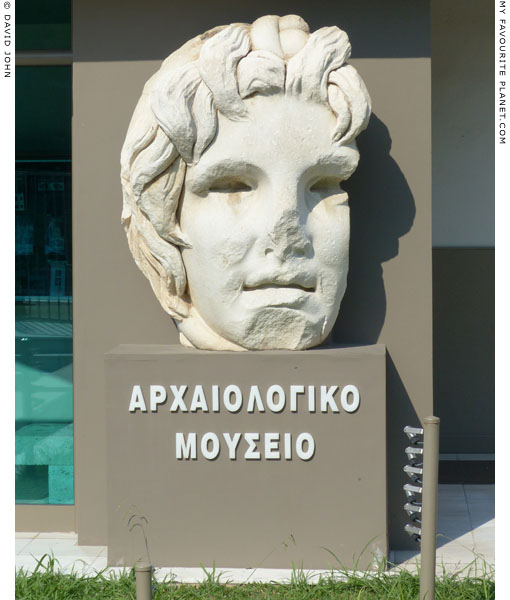

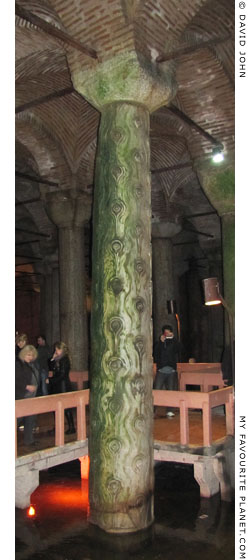

1. The Gorgon pediment in the Corfu Archaeological Museum

The Archaeological Museum of Corfu is a modern, purpose-built, two-storey building around 1 kilometre south of Corfu town centre. It was built 1962-1965 and opened in 1967. The Gorgo Hall was especially designed to display the Gorgon pediment, the museum's star exhibit and by far the most important and popular item in its collection, as well as other finds from the "Temple of Artemis". Following closure in 2012 for renovation, modernization and reorganization of the exhibition, the museum reopened in November 2018. Some objects have been moved to the Mon Repos Museum, and others mentioned in the 1997 guide book [see note 9] and other sources are no longer on display. The reorganization then appears to have included a streamlining or rationalization aimed at making the most of the available space, as well as concentrating visitors' attention on themed displays and making the exhibition more accessible.

On the whole it is an excellent museum, the visitor-friendly space is impressive without being overwhelming, and invites exploration. Exhibits are generally well displayed and labelled in Greek and English, and posters and computer displays provide contextual information, albeit a little generalized. A little more depth and detail about individual items and groups would be appreciated, particularly about findspots, as well as inventory numbers for those of us who would like to find out more about them.

The large Gorgo Hall is quite dark, with spotlights focussing attention on the enormous pediment itself, which takes up the entire length of the room. The lighting has a noticeable red tinge, which makes it difficult to appreciate the natural colour of the stone. For some reason two tall glass cases have been placed directly in front of the ends of the pediment (see photo above), which prevents visitors from being able to view the entire object and rather spoils the effect. It seems an odd design decision, especially as the cases contain a handful of the terracotta figurines from the Kanoni sanctuary that have little or perhaps no direct connection with the temple or the pediment.

Since the information material of both this museum and the Mon Repos Museum accept the theories that the temple was dedicated to Artemis and that she is the Gorgon in the pediment (discussed in the text above and the following notes), it is odd that only one of the two the inscriptions used to support the first theory is on display, and that no mention of is made of its relevance.

2. The colonization of Korkyra by Corinth

Plutarch wrote that Korkyra was colonized by Charicrates (Χαρικράτης) of Corinth who expelled Eretrian settlers, whereas according Strabo the name of the founder (οἰκιστής, oikistes, hearth-founder) was Chersicrates (Χερσικράτης), who forced the Liburnians from the island.

"Who are the 'Men repulsed by slings'?

Men from Eretria used to inhabit the island of Corcyra. But Charicrates sailed thither from Corinth with an army and defeated them in war; so the Eretrians embarked in their ships and sailed back home. Their fellow-citizens, however, having learned of the matter before their arrival, barred their return to the country and prevented them from disembarking by showering upon them missiles from slings. Since the exiles were unable either to persuade or to overcome their fellow-citizens, who were numerous and inexorable, they sailed to Thrace and occupied a territory in which, according to tradition, Methon, the ancestor of Orpheus, had formerly lived. So the Eretrians named their city Methone, but they were also named by their neighbours the 'Men repulsed by slings'."

Plutarch, Quaestiones Graecae, section 11 (Αἴτια Ἑλληνικά, The Greek Questions). Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1936. At Perseus Digital Library.

It has been suggested that the war said to have been waged on the Eretrians on Korkyra by the Corinthians was due to the latter having sided with Chalkis, Eretria's neighbouring city on Euboea, in their political rivalry which led to the pan-Hellenic Lelantine War, circa 710-650 BC (see History of Stageira and Olympiada part 2). This theory presupposes that the story told by Plutarch - rather than Strabo's version - is correct as to the identity of the displaced inhabitants of Korkyra, and that Corinth had become an ally of Chalkis against Eretria at this early date. Whether it was Ertrians, Liburnians or both who were driven from the island, the Corinthian colonizers may have just been opportunist raiders, with the confidence in their own military strength and indifference to the rights of others which characterized the second great wave of Greek colonization during the 8th - 6th centuries BC.

"Syracuse was founded by Archias, who sailed from Corinth about the same time that Naxus and Megara [on Sicily] were colonized ..."

"And when Archias, the story continues, was on his voyage to Sicily, he left Chersicrates, of the race of the Heracleidae, with a part of the expedition to help colonize what is now called Corcyra, but was formerly called Scheria; Chersicrates, however, ejected the Liburnians, who held possession of the island, and colonized it with new settlers, whereas Archias landed at Zephyrium, found that some Dorians who had quit the company of the founders of Megara and were on their way back home had arrived there from Sicily, took them up and in common with them founded Syracuse."

Strabo, Geography, Book 6, chapter 2, section 4. Translated by H. L. Jones. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1924. At Perseus Digital Library.

An inscription on a small limestone pediment of a monument, found in 1914 north of the "Temple of Artemis" and dated to the early 2nd century BC (see photo below), appears to support Strabo as far as the name of the founder is concerned. |

|

|

|

An inscribed limestone pediment of a monument from ancient Korkyra (Corfu), dedicated to

"Chersikrates the forefather". [see note 2] Thought to have been set up by members of

the genus (clan) of descendants of Chersicrates, the legendary Corinthian founder of Korkyra.

However, there is no evidence for the claim that the monument was dedicated to Artemis.

Χερσικρατιδᾶν πατρωϊστᾶν

To Chersikrates the forefather

Inscription IG IX 1, 4, 1140

Around 200 BC. Found in April 1914 north of the "Temple of Artemis", Corfu.

Height 29 cm, width 92 cm, depth 15 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum.

|

3. French discoveries in Corfu 1812-1813

Construction of the fortifications, including an enormous V-shaped earthwork bastion east of the monastery, was ordered by General François-Xavier Donzelot (1764-1843), the French governor of the Ionian islands 1807-1814, in anticipation of attack by the British navy which subsequently blockaded the islands. The measure may have been partly a way of occupying the enormous number of soldiers posted there (estimates vary between 17,000 and 20,000). During the work remains of a number of ancient buildings were unearthed, including part of the temple sanctuary and an aqueduct, as well as inscriptions, statues, coins and other artefacts, some of which are now in the Corfu Archaeological Museum.

See: Konstantinos Rhomaios (Κωνσταντίνος Ρωμαίος, 1874-1966), Les premières fouilles de Corfou. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (BCH), Volume 49, 1925. pages 190-218. At Persée.

The Danish archaeologist and traveller Peter Oluf Brøndsted (1780-1842), who happened to be in the Ionian islands at the time, was invited to assess the finds. He had recently achieved fame through his archaeological exploits, including the excavation of the temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai along with Charles Robert Cockerell and other young adventurers in 1812 (see Do Meteora dogs dream of floating sheep? at The Cheshire Cat Blog, and the Niobe page). Unfortunately, Brøndsted did not publish details of the French excavations, and they are only mentioned briefly in a footnote in the second volume of his book on his travels in Greece (dedicated to Cockerell and the Danish neo-classicist sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen).

In French: Peter Oluf Bröndsted, Voyages dans la Grèce, Deuxieme Livraison (Volume 2 of 2), page 285, footnote to text on Planche XXXVI. A. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1830. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

In German: Peter Oluf Bröndsted, Reisen und Untersuchungen in Griechenland, Band 2 (Volume 2 of 2), page 289, footnote to text on Tafel XXXVI. Verlag J. G. Cotta, Stuttgart; A. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1830. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The first published report of the French finds appeared in the official Paris newspaper le Moniteur universel in 1813. The article is signed "M.", thought to be the French military engineer Captain Teulié, le capitaine du génie Teulié mentioned by Brøndsted as having taken a special interest in the antiquities.

Mélanges - Antiquités. In: le Moniteur universel, No. 79, Samedi, 20 mars 1813, pages 293-294. At RetroNews, the press website of la Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The French Corfu excavations were also mentioned briefly in the memoirs of the French aide-major (adjutant) and doctor François-Victor Lamare-Picquot (1787-1865).

Huber Pernot (editor), Nos anciens à Corfou; Souvenirs de l'aide-major Lamare-Picquot (1807-1814), pages 151-153. Librairie Félix Alcan, Paris, 1918. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

4. Dörpfeld on the Artemis inscription in Corfu

One of two steles found to the north of the temple during Dörpfeld's excavations in March-May 1914, at the time of another visit by Kaiser Wilhlem II to Corfu. Dörpfeld wrote that there were traces of an inscription on the other stele but that they were illegible. Some of the letters of the Artemis dedication are missing, and Dörpfeld reconstructed it speculatively, although it has been pointed out that Μέντις (Mentis) is otherwise unknown as a Greek name (Günther Klaffenbach in Gerhart Rodenwaldt, Korkyra Band I, page 163 [see note 7]). He briefly mentioned the discovery of the inscription in his 1914 preliminary report (Vorbericht) on the excavations in Corfu.

Unusually for the seasoned and methodical archaeologist, he does not describe the stele, referring to it merely as "dreieckig" (three cornered, triangular), and no drawing or photograph was provided (although there is a photograph of the Chersikrates inscription [see note 2]). This now appears to be a serious lapse, especially as it was the only evidence he offered for his claim that Artemis was "the divine owner of the temple". He presumably intended to write a more detailed report, but World War I intervened. It was to take until 1939 before the publication of the more substantial two-volume study of the temple by Gerhart Rodenwaldt [see note 7], who had been an assistant to Dörpfeld during his first excavation in 1911.

The stele is exhibited in the Corfu Archaeological Museum but without explanation, and it seems strange that attention is not drawn to it as identifying the temple's deity. So far I have not found debate about this inscription, and Dörpfeld's reconstruction and association of it with the temple appear to remain almost unquestioned. I have not even been able to find an inventory number for the stele, or discussion of it in works on Greek epigraphy. The only two epigraphic references I have so far discovered (Klaffenbach in Korkyra Band I and Inscriptiones Graecae) do not concur with Dörpfeld's reconstruction, but it seems that the stele itself may not have been reexamined for many decades.

[.]εντις Ἀρι–

στέα Ἀρτάμ<ι>τι.

-entis son of Aristeas, to Artemis.

See: IG IX 1, 4, 852 at Inscriptiones Graecae, Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (BBAW). Notably, the translator has read "-entis" as a male name.

Information material of both the Corfu Archaeological Museum and the Mon Repos Museum [see note 9], as well as well as a number of other sources, state that Artemis was "one of the main deities on Corcyra" without citing literary, epigraphical or archaeological evidence. The main justification for this claim seems to be Dörpfeld's identification of the temple itself, as well as the large quantity of votive ceramics found on the Kanoni peninsula [see note 6].

Such large deposits of votive figurines, paricularly of Artemis, Demeter and Persephone, have been found at other Greek cities, mostly at modest sanctuaries, often outside the city. The worship of these goddesses appear to have particularly required the offering of such votive objects, which accumulated after being dedicated by several worshippers over long periods of time. But they do not necessarily indicate that the cult of the deity in question was of major importance. Although Korkyra issued coins relatively early, I have seen no coins of Korkyra from the Archaic or Classical periods that show Artemis. The paucity of archaeological remains so far discovered on Corfu make it difficult to gain a clear picture of the relative importance of particular cults, or to determine whether the Artemis cult was important enough to require the building of such a large temple at the beginning of the 6th century BC.

It has also been asserted that the cult of Artemis was widespread on the island:

"On the island of Corfu, the cult of Artemis was widespread from the Archaic to the Roman period, as is apparent from sanctuaries, inscriptions and votive offerings. This cult reached its height in the Archaic and Classical period, according to the evidence of votive offerings."

"... during the second half of the 6th and first half of 5th century, the cult of Artemis was very important on Corfu and widespread."

Kalliopi Preka-Alexandri, The cult of Artemis in Corfu. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (BCH), Volume 134, livraison 2, 2010, pages 400-407. At Persée.

This claim is also partly based on the belief that the temple was dedicated to Artemis, as well as the votive ceramics from Kanoni and smaller numbers from other sites (some from domestic or guild contexts). Preka-Alexandri's article, which deals mainly with the types of figurines, only mentions one inscription, κονων αρτεμιτι δωρον, on a small altar found in a workshop district of the city. However, there is insufficient evidence to prove that the cult of Artemis was more widespread here than those of other deities, or than in other Greek city states (Athens, for example, had at least two sanctuaries to Artemis, as Artemis Brauronia and Artemis Agrotera).

Dörpfeld's main argument for identifying the inscription with the temple was his dismissal of the idea that the stele could have been brought there from elsewhere, even though he must have known of other cases of spolia taken considerable distances to be reused (e.g. the Themistoklean Wall in Athens). He also failed completely to entertain the idea that dedications to one deity may have been set up at or near the sanctuary of another god, or that the sanctuary area (if not necessarily the temple itself) may have been shared, as frequently occurred (see, for example, the Sanctuary of Demeter in Syracuse). Several votive offerings to Kybele were found at the Archaic "Kardaki Temple" in Mon Repos, whose deity is unknown (perhaps Poseidon or a chthonic deity), but it has not been suggested that this was a temple of Kybele.

"Da die beiden Stelen schwerlich aus einem anderen Heiligtum in unseren Bezirk verschleppt worden sind, so dürfen wir annehmen, dass Artemis die in unserem Tempel verehrte Göttin war. Das passt gut zu der schon früher ausgesprochenen Vermutung, dass der Tempel der Göttin Gorgo geweiht war, weil diese im westlichen Giebel sicher, im östlichen wahrscheinlich dargestellt war. Gorgo und Artemis sind dieselbe Göttin. Wie in Ephesos und in anderen Städten Kleinasiens die ursprünglich vorgriechische Göttin Kybele, die grosse Mutter, später von den Griechen als Artemis verehrt wurde, so wird auch in Kerkyra unser Tempel ursprünglich der grossen Mutter, der Herrin über Menschen und Tiere, geweiht gewesen sein, und diese ist dann später der griechischen Artemis gleichgesetzt worden."

"Since both steles could hardly have been hauled from another sanctuary into ours, we may assume that Artemis was the goddess worhipped in our temple. That fits well with the previously expressed conjecture that the temple was dedicated to the goddess Gorgo, while she is certainly depicted on the west pediment, and probably also on the east pediment. Gorgo and Artemis are the same goddess. As in Ephesus and other cities in Asia minor the originally pre-Greek goddess Kybele, the Great Mother, later worshipped by the Greeks as Artemis, so in Kerkyra our temple would have been originally dedicated to the Great Mother, the mistress over humans and animals, who was later equated to the Greek Artemis."

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Ausgrabungen auf Korfu im Fruhjahr 1914 (Vorbericht). In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 39, pages 161-176 (the discovery of the inscription pages 169-170). Eleutheroudakis und Barth, Athens, 1914. At the Internet Archive. (my translation and emphasis)

See further references to the excavations of the "Temple of Artemis" on the Friderikos Versakis page.

The idea of the Gorgon as Artemis had been discussed in 1911 by the American art historian Arthur Lincoln Frothingham Jr. (1859-1923), who had studied in Germany (Adolf Furtwängler was one of his teachers) and was in correspondence with Dörpfeld. The article is fascinating, but the hypothesis is not entirely convincing.

"This conclusion is that Medusa was not an evil demon or bogey, but primarily a nature goddess and earth-spirit of prehistoric times identical with or cognate to the Great Mother, to Rhea, Cybele, Demeter, and the "Mother" Artemis. As a procreative and fertilizing energy embracing the action of light, heat, and water on the earth, she became an embodiment of both the productive and destructive forces of the sun and the atmosphere, an emblem of the sun-disk."

A. L. Frothingham, Medusa, Apollo, and the Great Mother. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 15, No. 3 (July - September 1911), pages 349-377. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org. |

| |

A terracotta figurine of Artemis seated on

a panther. Late Archaic period. Found in a

ceramic workshop in ancient Korkyra.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. |

| |

A coin of ancient Korkyra showing a male god

standing in a temple with Corinthian columns.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

|

5. Corfu Artemis inscription found in 1813

The top of an inscribed limestone pedestal with a dedication to Artemis, dated to the second half of the 4th century BC (see illustration, right). Two indentations in the damaged top indicate that it may have been the base for a statue. The bottom of the stone is broken off.

Φιλόξενος Αἰσχρίωνος

[κ]αὶ σύναρχοι [Ἀρ]τάμιτι.

Philoxenos, son of Aischrionos,

and his colleagues, to Artemis.

Inscription IG IX 1, 706 (C.I.G. 1849) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 9. Not on display.

Height approx. 46 cm, width 45 cm, depth 18.5 cm.

The first letter of each line is no longer visible.

Based on other inscriptions from Corfu, it has been suggested that Philoxenos may have been an archon or prytanis of Korkyra, and his colleagues (σύναρχοι, synarchoi) subordinate members of the "college" of the governing body. However, this is not automatically implicit, and little is known of the political history of Korkyra during this period.

The discovery of the base was first mentioned in a pamphlet by the Corfiot Antonio Vracliotti in late 1813. The exact findspot is uncertain, but said to have been in the area of the Monastery of Agios Theodoros. Although in the illustration the inscription appears very clear, the French classical philologist and archaeologist Othon Riemann (1853-1891) noted that the lettering was primitively carved and difficult to read. Andreas Moustoxydis (Ανδρέας Μουστοξύδης; Italian, Andrea Mustoxidi; 1785-1860), the Corfiot historian, philologist and first ephor of antiquities on the island, who first published the inscription in 1814, appears to have misread it. Following correction by August Böckh, both readings were shown in his Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum (C.I.G.). Moustoxydis later added the correction in a later book (1848).

See:

Antonio Vracliotti, Opuscolo intorno alcune iscrizioni lapidarie rinvenute negli scavi fatti ultimamente à Corfu. Nella Stamperia impériale, 1813.

Othon Riemann, Recherches archéologiques sur les îles ioniennes, Volume I: Corfou, inscription No. 18, page 46. Ernest Torin, Paris, 1879. At the Internet Archive.

Andrea Mustoxidi, Illustrazioni corciresi di Andrea Mustoxidi istoriografo dell'isole dello Ionio, Tomo II, inscription XXXIX, page 88. G. G. Destefanis, Milan, 1814. At the Internet Archive.

Andrea Mustoxidi, Delle cose corciresi, Volume Primo, inscription LIII, page 221. Tipogr. del governo, Corfu, 1848. At Googlebooks. (No further volumes were published.)

August Böckh, Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, Volumen secundum (Volume 2), Pars VIII: Inscriptiones Corcyrae, page 26. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1843. At Googlebooks.

Konstantinos Rhomaios pointed out the forgotten inscription in a short article in 1921, and discussed it further in 1925.

Παράρτημα του Αρχαιολογικου Δελτίου 1920 - 1 (supplement), pages 165-166. In: Αρχαιολογικον Δελτίον, Τόμος 6, 1920/1921 (Archaiologikon Deltion, Volume 6, 1920/1921). Τυπογραφείον Εστία, Athens, 1923. PDF at the University of Thessaly Institutional Repository.

Konstantinos Rhomaios, Les premières fouilles de Corfou, BCH, 49, 1925 [see note 3].

The base and its inscription was briefly discussed by Günther Klaffenbach in: Gerhart Rodenwaldt, Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker, Band 1, III. Die Inschriften, No. 1, page 163 [see note 7]

6. The Small Sanctuary of Artemis on the Kanoni peninsula, Corfu

The site was a field in the area known as Figareto (Φιγαρέτο), near the southwest end of the Kanoni peninsula, just north of the village of Kanoni (now a suburb of Corfu town). The first finds were made there in 1879 during excavations by the wealthy Greek businessman, politician and amateur archaeologist Konstantinos Karapanos (Κωνσταντίνος Καραπάνος, 1840-1914; see the note in Homer part 3). He purchased the land and invited Paul-François Foucart, director of the French Archaeological School at Athens (l'École française d’archéologie d'Athènes), to participate in the excavations.

In May-June 1889 the work was continued by Henri Lechat (1862-1925) of the French School, who discovered foundations of buildings as well as around five thousand terracottas (many in fragments), including a large number of figurines of Artemis, which at the time was hailed as "the most important collection of archaic terracottas yet found on Hellenic soil".

See: A. L. Frothingham Jr. (editor), Archaeological News, in: The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Volume 5, No. 3 (September 1889), page 378. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Lechat published his findings in 1891.

Text: Henri Lechat, Terres cuites de Corcyre. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (BCH), Volume 15, 1891, pages 1-112. At Persée.

Illustrations: Planches (plates). In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (BCH), Volume 15, 1891, planches I-VIII. At Persée.

Altogether over 7000 fragments of figurines believed to represent Artemis have been found at the site, dated from the late Archaic to early Classical periods. Moulds for the production of ceramic figurines from the same timespan, including those of Artemis and other female deities have been discovered at the remains of nearby pottery workshops, and other artefacts related to the Artemis cult have been found at other locations around the island.

See: Kalliopi Preka-Alexandri, The cult of Artemis in Corfu [see note 4].

As with most of the area in and around Corfu town, very little archaeological excavation has been undertaken at Figareto, since it is built over with modern suburban houses and businesses. It is thought to have been an area of industrial workshops, particularly for the production of ceramics, similar to the Kerameikos district of ancient Athens. Remains found here include those of eleven pottery kilns, dating from the late Archaic period until the early Roman period, as well as deposits of ceramic objects. The sanctuary of Artemis may have been part of the pottery workshop and the goddess worshipped here as Artemis Epiklivania (Artemis of the kilns). This excavated area now forms the small archaeological site known as "Kerameikos at Figareto" (Κεραμεικός Φιγαρέτο), which is neither easy to find nor signposted.

7. Gerhart Rodenwaldt and others on the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu

So far the only comprehensive study of the temple is Gerhart Rodenwaldt's two volume work, published 1939-1940 (for some reason Volume 2 appears to have been published in 1939, before Volume 1), to some extent based on the notes and reports of Dörpfeld's excavations, as well as his journals. It includes details of the archaeological investigations at the site up to that date, with several photographs, plans and drawings, and attempts to present aspects of the temple and sanctuary in a scientific and methodological manner. The style is thus rather dry, and does not make for easy reading. The presentation of facts and figures is also old-fashioned and often approximate.

Some of the sections are quite terse, particularly Günther Klaffenbach's descriptions of the inscriptions, most of which are not illustrated. One would have hoped for more details about some of them.

Gerhart Rodenwaldt (editor), Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker, Band 1, Der Artemistempel: Architektur, Dachterrakotten, Inschriften. Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 1940. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Sections by Hans Schleif (architecture), Konstantinos A. Rhomaios (roof terracottas) and Günther Klaffenbach (inscriptions).

Gerhart Rodenwaldt, Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker, Band 2, Die Bildwerke des Artemistempels. Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 1939. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Rodenwaldt described and discussed all the surviving sculptural fragments found at the temple and the reconstruction of the Gorgon pediment.

A recent academic paper mentions that the reconstruction of the temple by Rodenwaldt and Schleif "has been criticized in minor respects, but the plausibility of the pedimental sculptures in their proposed position has been generally accepted. In this paper however structural analysis suggests that the current position of these sculptures is inconsistent with stability. This triggers a revised reading of the architectural reconstruction, calling into question the whole plan, with its supposed grand pseudo-dipteral layout."

Georg Herdt, Aykut Erkal, Dina D’Ayala and Mark Wilson Jones (University of Bath, UK), Structural Assessment of Ancient Building Components, the Temple of Artemis at Corfu. In: Phillip Verhagen (editor), Proceedings of the 40th Conference in Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, Southampton, United Kingdom, 26-30 March 2012, pages 130-137. Amsterdam University Press, 2014. At academia.edu. |

| |

The dedication to Artemis by Philoxenos

and his colleagues, found in Corfu in

1813 during the French excavations.

Source: Konstantinos Rhomaios (Κωνσταντίνος

Ρωμαίος, 1874-1966), Les premières fouilles

de Corfou. In: Bulletin de correspondance

hellénique (BCH), Volume 49, 1925,

pages 190-218, fig. 4. At Persée. |

| |

Andreas Moustoxydis (Ανδρέας Μουστοξύδης,

1785-1860), Corfiot politician, historian,

philologist, first ephor of antiquities on Corfu

and founder of the Greek Archaeological Service

following, liberation from Ottoman occupation.

Print in the Spiros P. Gaoutsis Collection, Corfu. |

| |

|

8. Bearded snakes

Bearded snakes are not now known in nature, although two species of Fimbrios in southeast Asia are referred to as such because they have hardly visible scales hanging from their lower jaws. Bearded snakes are mentioned in Hittite and Mesopotamian literature. The beards of serpents in Egyptian art have been compared to the false beards worn by pharaohs, and the art historian John Boardman suggested that the Greeks took the idea of the bearded snake from the Egyptians. From the Classical period they were particularly associated with the chthonic deity Zeus Meilichios, who was often depicted as a giant serpent.

See:

John Boardman, The Greeks overseas, page 151. Thames and Hudson, London, 1980.

Lisa C. Pieraccini, Sacred serpent symbols: The bearded snakes of Etruria. In: Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, Volume 10, September 2016, pages 92-102. University of Arizona. Open Access article at University of Arizona Libraries.

See also bearded snakes on a bronze kerykeion (caduceus) from Syracuse on the Hermes page.

9. The Corfu Gorgon as Potnia Theron / Artemis

"Artemis, one of the main deities on Corcyra, was worshipped as 'Mistress of Animals', that is as the ruler of the world of wild animals. Her cult was practised in the large temple known as the Gorgon temple, after the preserved stone pediment, in which the Gorgon is identified with Artemis."

Information board in the Mon Repos Museum, Corfu.

See also:

Alkestis Spetsieri-Choremi, Ancient Kerkyra, pages 20-22. Greek Ministry of Culture, Archaeological Receipts Fund (ΤΑΠΑ, TAPA), Athens, 1997 (second edition). The official guide book to the Corfu Archaeological Museum, now a little outdated, especially since the recent reorganization of the museum's exhibits, but still worth the price as the only book available for the general reader which deals with the history and archaeology of Corfu in any depth.

See also note 4, for the idea expressed by Wilhelm Dörpfeld and A. L. Frothingham.

10. The Gorgon on the Corfu temple

In her PhD thesis, Elinor Bevan cited Charles Martin Robertson's reminder that the deities and other beings sculptured on temple exteriors were not necessarily the gods housed within:

"C. M. Robertson has pointed out that the god to whom a temple belonged was not necessarily shown in its exterior decoration, and that sometimes another god might appear there."

(Martin Robertson, A history of Greek art, Volume 1, page 166. London, 1975.)

The truth of such a statement can be demonstrated with examples of better documented temples (e.g. Dionysus on the west pediment of the Temple of Apollo in Delphi). However, she too acepted not only that the Corfu temple belonged to Artemis, but that the Gorgon with lions on the pediment "must" identify her as an aspect of the goddess as Potnia Theron.

"Yet some architectural decorations are clearly relevant to the deity, and to his or her cult - like the pedimental sculptures and frieze of the Parthenon. The beasts of prey on the pediment of Artemis' Archaic Temple in Corcyra must express an aspect of the potnia theron to whom it belonged; as the sea-creatures of Poseidon's Hellenistic temple in Tinos express his power over the sea."

"Finally, the pedimental sculpture of Artemis' Corcyra temple, despite the gorgonian nature of the central figure, surely identifies the patron of the sanctuary in this fierce potnia with the beasts of prey."

Elinor Bevan, Representations of animals in sanctuaries of Artemis and of other Olympian deities, pages 8 and 242. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1985. At Edinburgh Research Archive (ERA), University of Edinburgh. |

| |

Medusa with six bearded snakes on an Attic

black-figure olpe (jug), made in Athens around

550-530 BC and signed by the potter Amasis.

The painting is attributed to the Amasis Painter.

See the entire painting of Perseus decapitating

Medusa, watched by Hermes, in Medusa part 1.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. 1849,0620.5

(Vase B471). Acquired in 1849.

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum. |

| |

| |

Photos on the Medusa pages were taken

during visits to the following museums:

Germany

Berlin, Altes Museum

Berlin, Bode Museum

Berlin, Neues Museum

Dresden, Albertinum, Skulpturensammlung

Dresden, Semperbau, Abgusssammlung

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Münzkabinett

Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe

Speyer, Historisches Museum der Pfalz

Greece

Abdera Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Athens, Acropolis Museum

Athens, Epigraphical Museum

Athens, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum

Athens, National Archaeological Museum

Athens, Numismatic Museum

Corfu Archaeological Museum

Corfu, archaeological site of the Temple of Artemis

Corfu, Museum of Mon Repos

Corinth Archaeological Museum

Delos Archaeological Museum

Delphi Archaeological Museum

Dion Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Eleusis Archaeological Museum and site, Attica

Eretria Archaeological Museum, Euboea

Isthmia Archaeological Museum

Kavala Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Komotini Archaeological Museum, Thrace

Kos Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Marathon Archaeological Museum, Attica

Mycenae Archaeological Site and Museum

Mykonos, Aegean Maritime Museum

Mykonos Archaeological Museum

Nafplion Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Olympia, Museum of the History of the Olympic Games in Antiquity

Patras Archaeological Museum, Peloponnese

Philippi Archaeological Museum

Piraeus Archaeological Museum, Attica

Polygyros Archaeological Museum

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum, Elis

Rhodes Archaeological Museum, Dodecanese

Rhodes, Palace of the Grand Master

Thasos Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Thebes Archaeological Museum, Boeotia

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Veria Archaeological Museum, Macedonia

Italy

Milan, Civic Archaeological Museum

Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Ostia Archaeological Museum

Paestum, National Archaeological Museum, Campania

Rome, Capitoline Museums, Palazzo dei Conservatori

Rome, National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Baths of Diocletian

Rome, National Museum of Rome, Palazzo Massimo

Rome, Villa Farnesina

Italy - Sicily

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum

Castelvetrano, Museo Civico

Catania, Museo Civico, Castello Ursino

Gela Regional Archaeological Museum

Palermo, Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum

Syracuse, Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum

Netherlands

Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum

Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

Turkey

Bergama (Pergamon) Archaeological Museum

Didyma archaeological site

Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Selçuk

Ephesus archaeological site

Istanbul Archaeological Museums

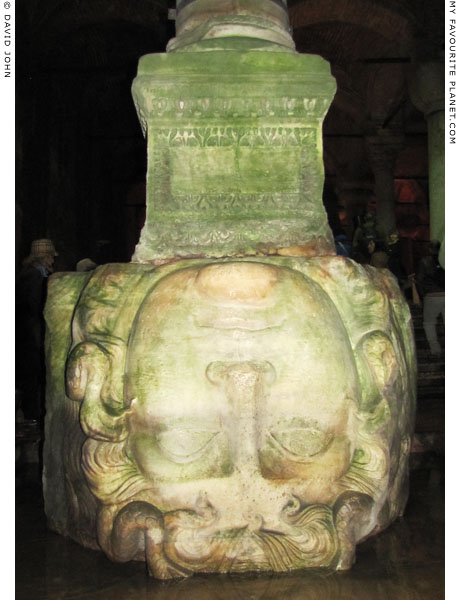

Istanbul, Basilica Cistern

Izmir Archaeological Museum

Izmir Museum of History and Art

Manisa Archaeological Museum

United Kingdom

London, British Museum

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

Many thanks to the staff of these museums,

especially at Dion, Gela, Manisa and Veria. |

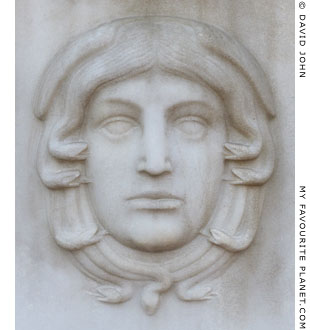

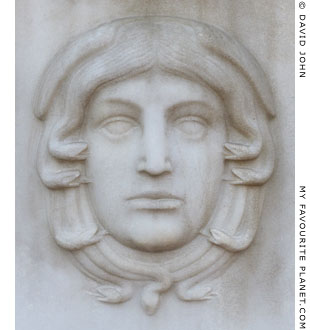

Gorgoneion on a gatepost of the Schiller

Monument (Schillerdenkmal) in Dresden.

1914. White Lasa marble.

The monument to Johann Christoph Friedrich

von Schiller (1759-1805), the German doctor,

historian, philosopher, poet and playwright,

was designed by Dresden architect Oswin

Hempel (1876-1965), with a marble statue

of Schiller and reliefs illustrating his works

by local sculptor Selmar Werner (1864-1953).

Originally conceived in 1905 to commemorate

the 100th anniversary of Schiller's death, it

was completed and unveiled on 9 May 1914.

The relief on the other (right) gatepost

depicts the head of a Silen.

Because the monument is in the form of

a high circular wall surrounding Schiller's

statue, locals have nicknamed it "Schiller in

der Badewanne" ("Schiller in the Bathtub"). |

| |

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |