| |

The Propylaia viewed from the Areopagus. |

| |

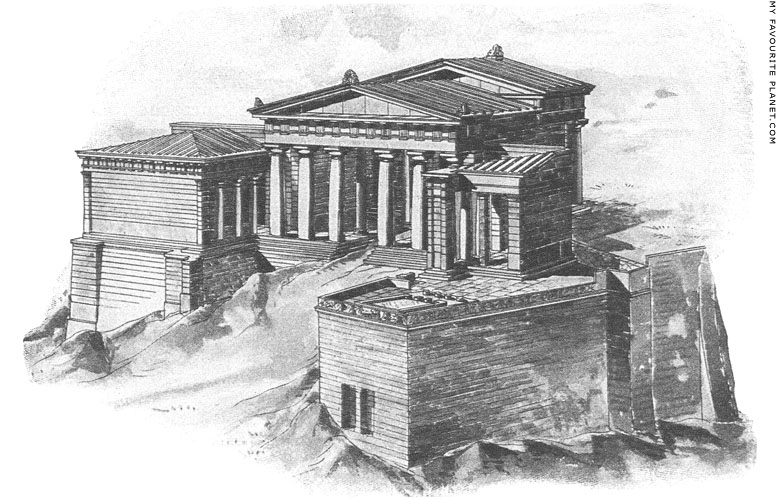

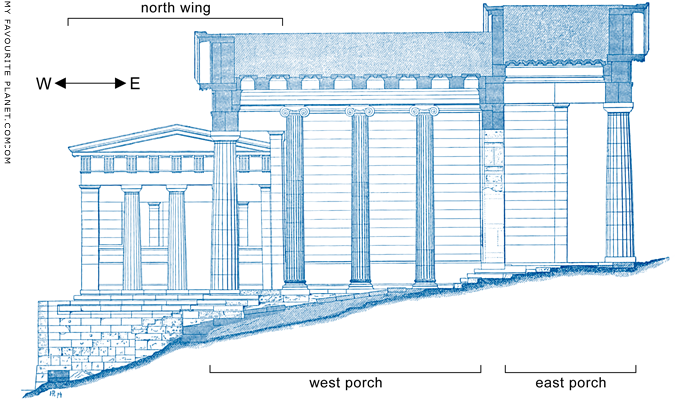

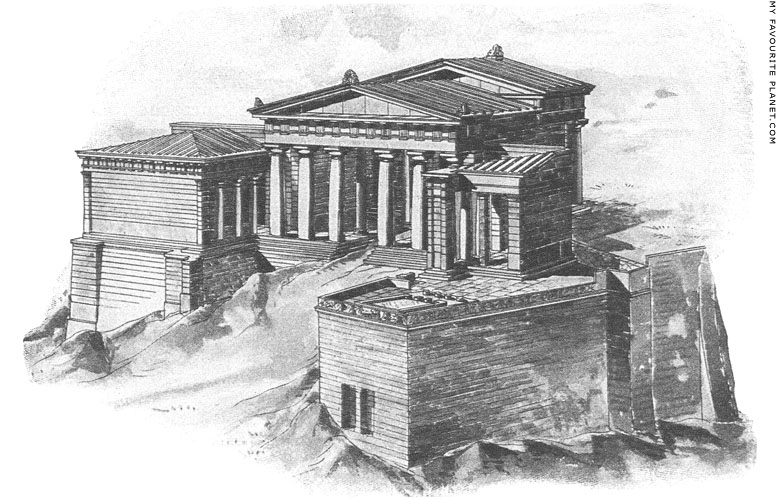

Reconstruction drawing of the Propylaia, viewed from the southwest, as it

may have appeared in the Classical period. The Temple of Athena Nike has

been omitted from the drawing in order to give a clear view of the gateway.

Image source: Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, Fig. 37.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

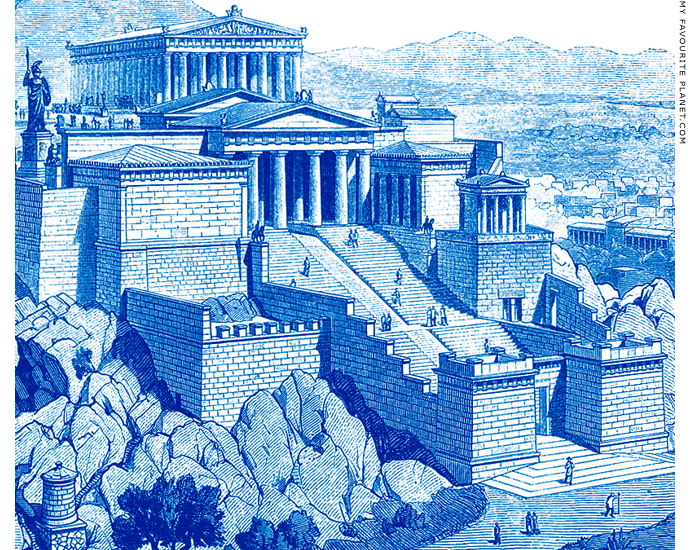

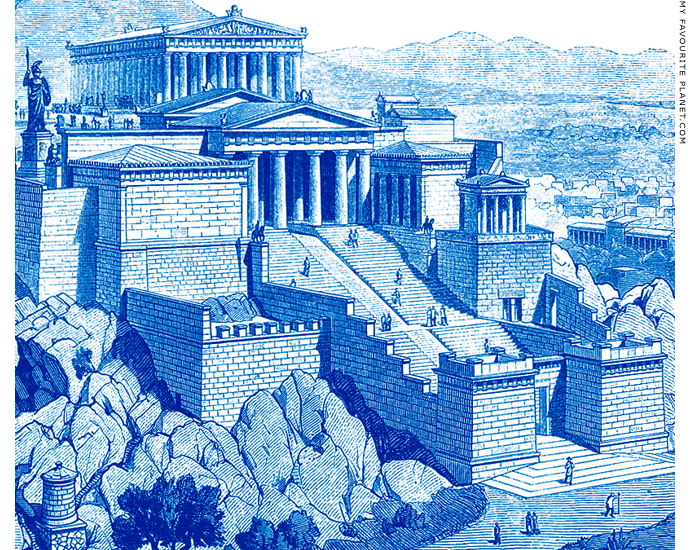

Reconstruction of the entrance at the west side of the Acropolis, as it may have looked

in the late Roman period, after the building of the Beulé Gate in 280 AD.

Image source: Wilhelm Wägner and Fritz Baumgarten, Hellas, Land und Volk der Alten Griechen.

Verlag von Otto Spamer, Leipzig, 1902. Illustration by Friedrich von Thiersch (1852-1921). |

| |

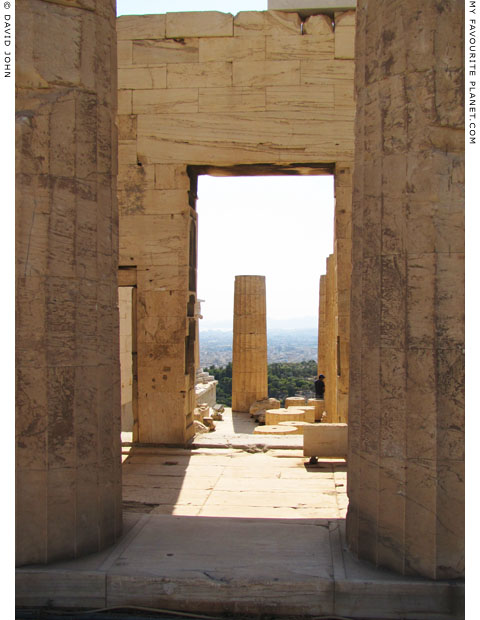

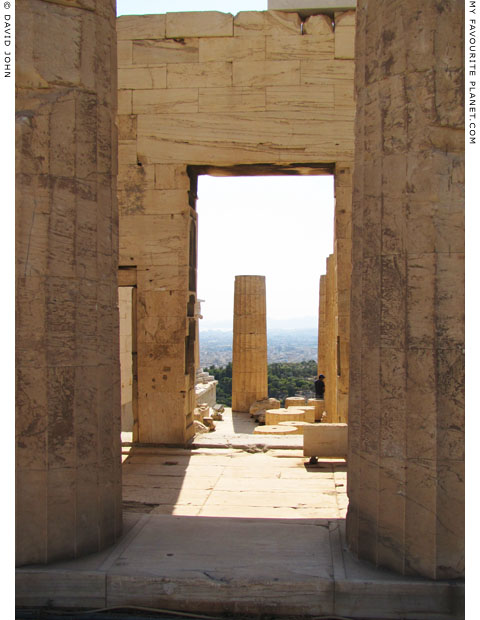

The central gateway of the Propylaia. See also photos on gallery page 7. |

| |

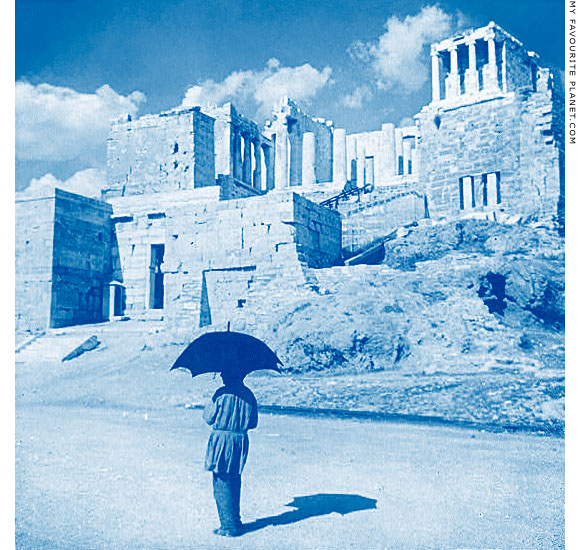

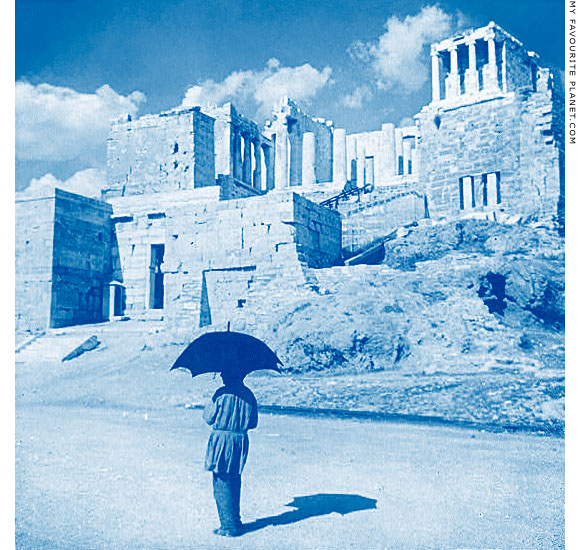

The Propylaia as it looked in 1893, before further restorations and tree plantings.

|

The two towers (or pylons) of the late Roman Beulé Gate can be clearly seen standing in front of the ascent ramp to the Classical Propylaia entrance to the Acropolis. The smaller tower on the right is today invisible from this vantage point because of the trees which have been planted around the modern visitors' entrance.

To ease the flow of visitors at the entrance to the Acropolis, which can get very crowded in summer, you enter between the towers of the Beulé Gate and climb the stairs up to the Propylaia (see gallery page 7). On the way out, visitors are chanelled down a modern metal stairway, on the left (north) as you exit the Propylaia and down through the small gateway in the north tower of the Beulé Gate (see also gallery page 30).

Photo: William Vaughn Tupper, 1893. From the Tupper Scrapbooks Collection

at the Boston Public Library Print Department.

"All that is known of this celebrated city, previous to its decay and ruin, is more accessible in London than on the Acropolis. The story of its former greatness still lives in the classic page; the vestiges of its ancient splendour are now scarcely discernible upon the thinly tenanted and barren site."

Edward John Burrow, The Elgin marbles: with an abridged historical and topographical account of Athens. James Duncan, London, 1837. At Google Books. |

|

| |

Another view of the entrance to the Acropolis, around 1905.

Source: Stereograghic print, circa 1905. Photographer unkown.

At Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C. |

|

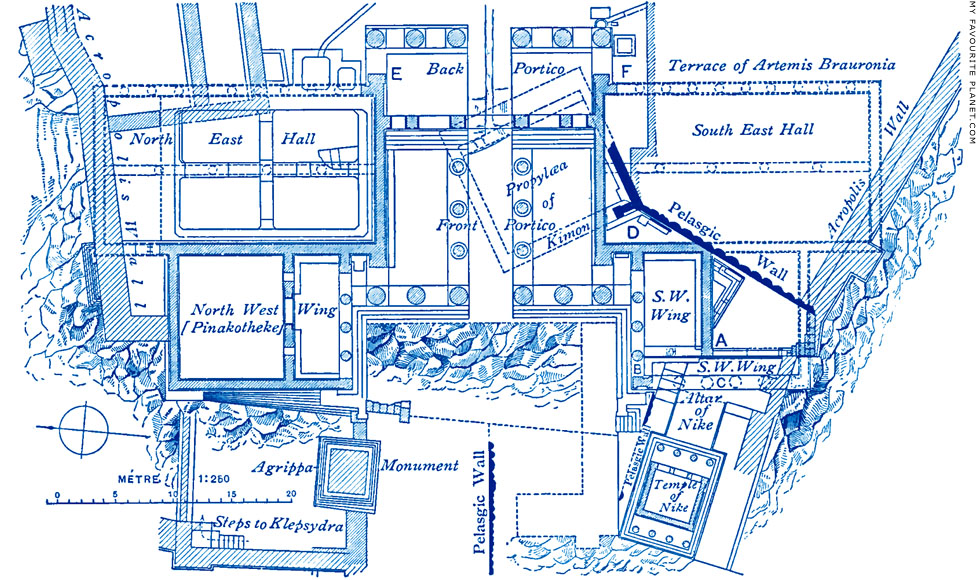

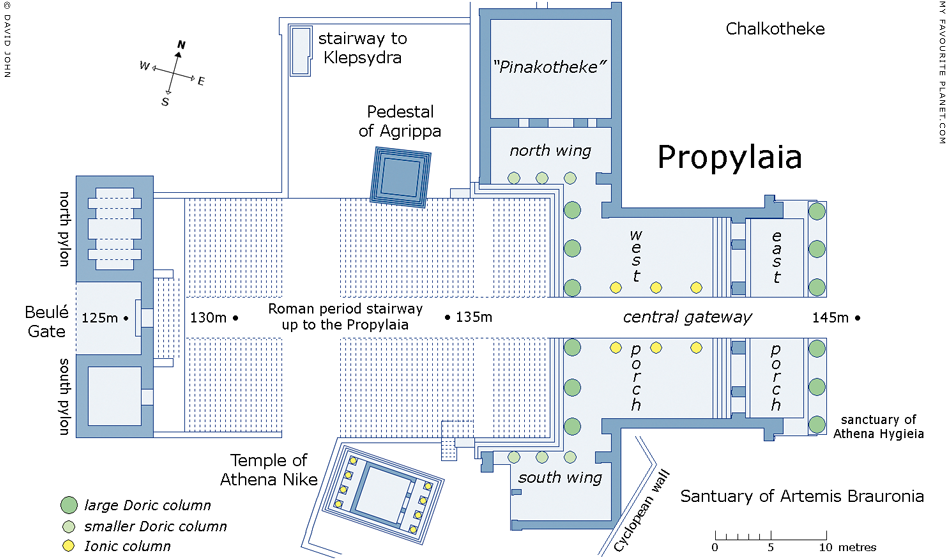

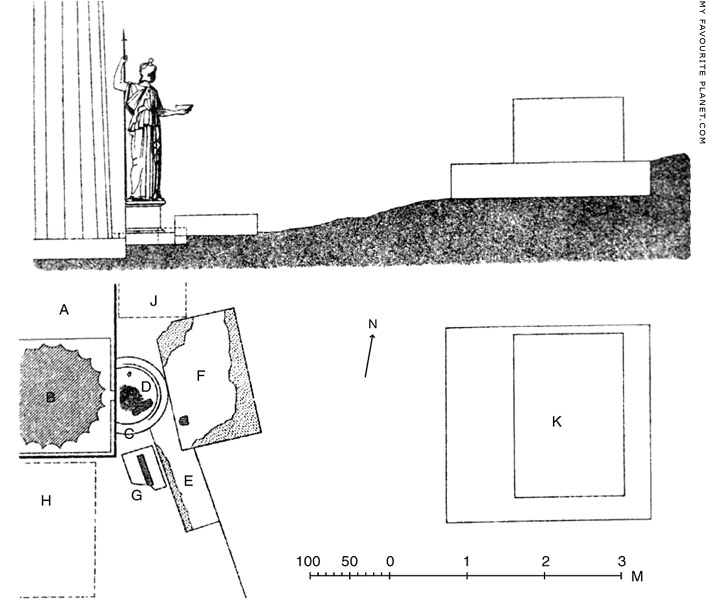

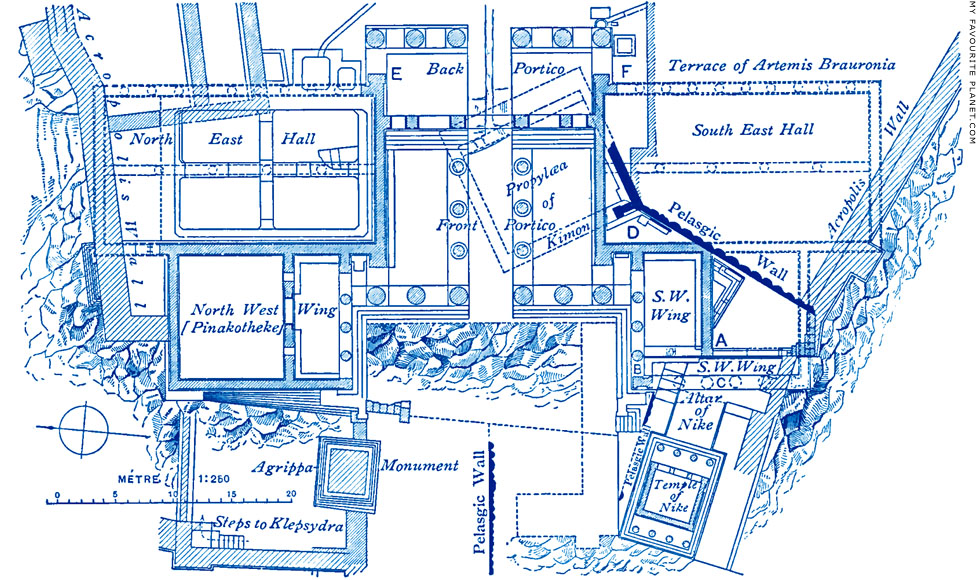

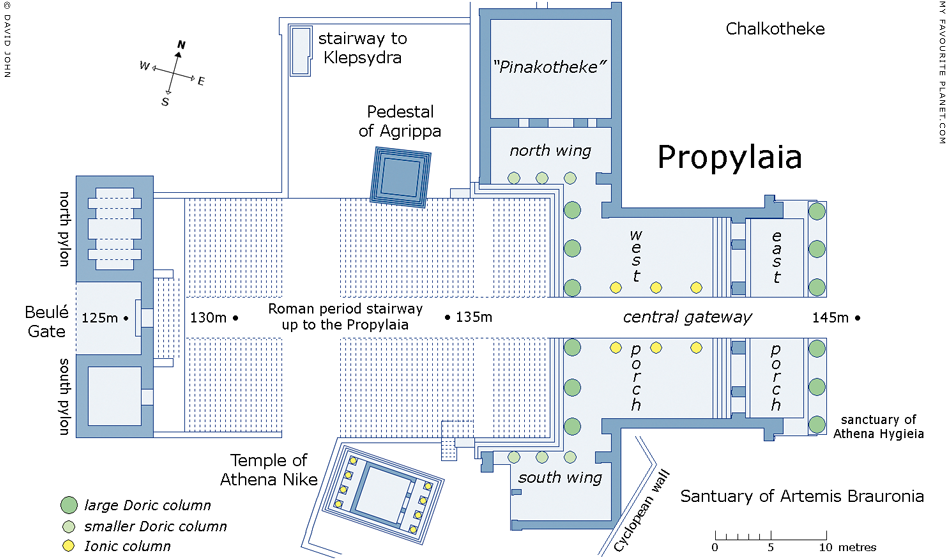

Plan of the Propylaia of the Athenian Acropolis.

Dotted lines have been used to show the locations of the Archaic Propylon (see below)

and the extent of the North East Hall and the "South East Hall", believed by some

scholars to have been originally planned by Mnesikles, but which was never built.

Image source: Margaret de G. Verrall and Jane E. Harrison, Mythology and monuments of

ancient Athens, Division D, fig. 5, page 352. Macmillan & Co., London & New York, 1890.

The plan was also published in: Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach den Berichten

der Alten und den neusten Erforschungen, Fig. 72. page 177. Verlag von Julius Springer, 1888. |

| |

Interactive graphic: click on a building to go to its gallery page.

Simplified plan of the entrance to the Acropolis, with the Beulé Gate (left) and the Propylaia (right).

At the southeast corner of the east porch of the Propylaia

stood the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia (see below).

The climb eastwards up to the Acropolis is a steep 25 metres in 80 metres:

the Beulé Gate is 125 metres above sea level, with the stairway and central

ramp rising to 145 metres just east of the Propylaia. The Parthenon is at the

155 metre mark, the highest point on the Acropolis.

Graphic by © David John 2011, based on various drawings, photos and surveys. |

| |

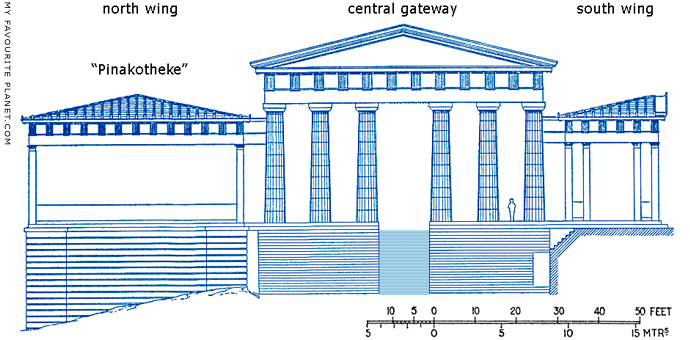

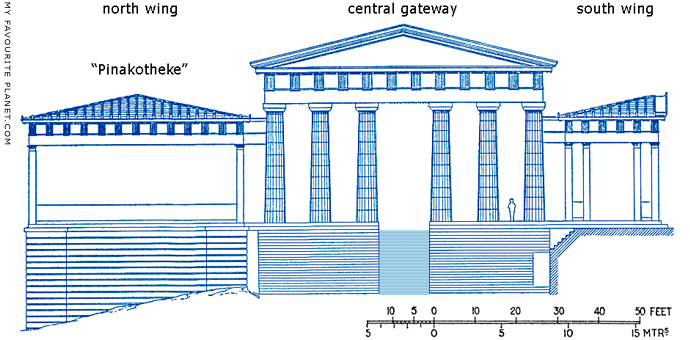

Simplified elvation of the west face of the Propylaia (reconstruction).

width of Doric column base 5 feet 1 inch (154.9 cm); width between columns 6 feet (182.9 cm);

width of central entry-way 12 feet 4 inches (375.9 cm); height of columns 29 feet (883.9 cm)

The tapering of the large Doric columns is indicated, but not the subtle curvature known as

entasis (Greek, ἔντασις, tension), which was first noted in the early 19th century

by the English architect Charles Robert Cockerell (see The Cheshire Cat Blog, July 2011).

Today it seems astonishing that previous modern writers on ancient architecture failed

to recognize this feature, particularly as many of them would have been familiar with

Vitruvius who mentions entasis in his De Architectura. [6]

Illustration after Banister Fletcher and Banister F. Fletcher, A History of Architecture

on the Comparative Method. 6th edition. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1921. |

| |

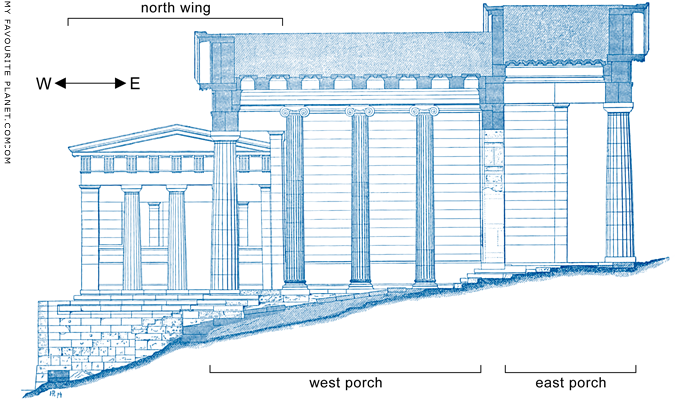

Section of the Propylaia (reconstruction).

From left to right: the smaller porch of the north wing fronted by a colonnade of Doric columns;

the western portico of the central gateway, at the front (left) of which are 3 Doric columns

on either side of the ramp which passed through the centre of the gateway, and on the inner

side 3 Ionic columns; the eastern porch with a higher roof and a front porch (right) supported

again by 3 Doric columns on either side of the ramp and central entryway.

Image source: Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach den Berichten der Alten

und den neusten Erforschungen, Fig. 77, page 183. Verlag von Julius Springer, 1888. |

| |

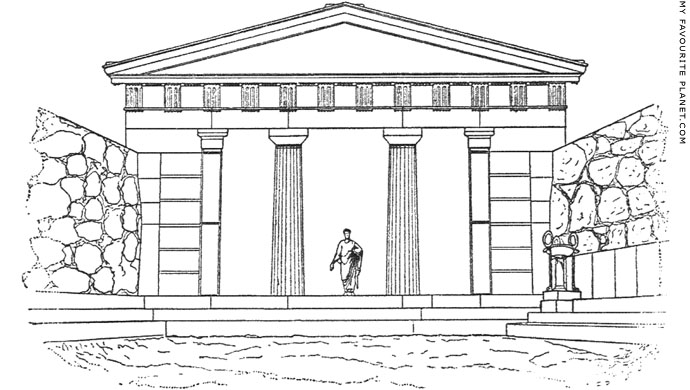

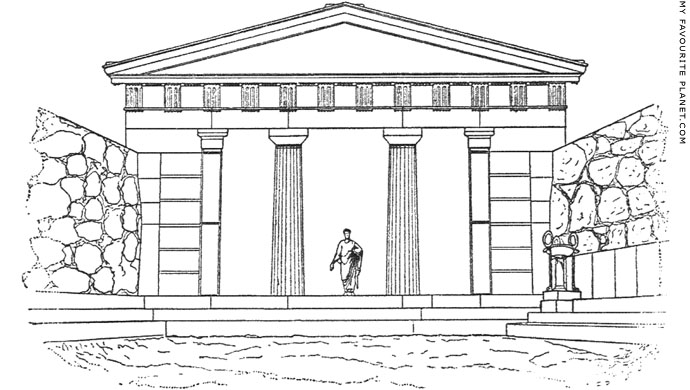

A speculative reconstruction drawing of the late Archaic Propylon, thought to have been built

after the first Persian invasion and the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC and before the second

Persian invasion of 480-479 BC. It was demolished in 437 BC to make way for the new Propylaia.

|

Believed to have been built entirely of Pentelic marble, the Propylon stood in a gap in the Pelasgic Wall (see gallery page 1). The base of the section of the wall on the right (south) was dressed with metope panels from the pre-Parthenon Hekatompedon temple (see gallery page 13), Some of these panels are still in situ to the south of the Propylaia, along with the base of an object which may have been a tripod.

The size, plan and architecture of the gateway are unknown, although several theories have been put forward by archaeologists and architects who studied its remains, including Bundgaard, Choisy, Dinsmoor, Dörpfeld, Michaelis, Stevens and Weller. They range from visons of a wide building with 4 columns in antis at both ends, 4 piers in antis and colonnaded approach, to a much simpler square gateway without columns. It was believed by some scholars to have had a forecourt.

Excavations by Harrison Eiteljorg, who investigated the Propylon in 1975, 1987 and 1989, led him to the conclusion that it was smaller and simpler than previously supposed, and that there were three separate building phases, although these could not be precisely dated. The first phase was probably between 490 and 480 BC, and the second was during repairs following the destruction on the Acropolis caused by Xerxes' invasion in 480-479 BC. It appears that the structure may have been unstable following these repairs, so that further works had to be untertaken before 437 BC.

Image source: Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, Fig. 10, page 7. R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. The Drawing by C. H. Weller originally appeared in the American Journal of Archaeology. |

|

| |

The north wing of the Propylaia. Behind the Doric columns

a window and doorway to the "Pinakotheke" can be seen. |

| |

An Ionic capital from one of the six columns lining the central entrance of the Propylaia

(coloured yellow in the plan above). Pentelic marble. 437-432 BC.

New Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 13304+. |

| |

A panel from the ceiling of the central entrance of the Propylaia with two square coffers.

The ceiling was decorated with painted mouldings and a gilt star in the centre of each coffer.

Pentelic marble. 437-432 BC.

New Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 20504. |

| |

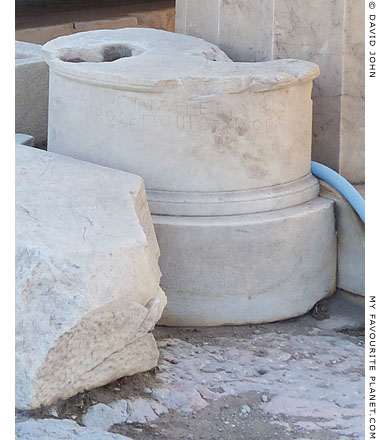

A marble block with a catalogue of the names of Pyloroi, religious magistrates

who were honorary guards of the Propylaia. During their magistrature

a stairway up to the the Acropolis was constructed (around 52 AD).

Roman period, 1st century AD.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 450. Inscription IG II (2) 2297. |

|

The west side (outside) of the Propylaia in the early 19th century, by British architect William Kinnard

(died 1839), showing the Medieval and Ottoman fortifications. The Turkish cannon emplacement (left)

was built in 1687 from parts of ancient monuments, including the Temple of Athena Nike

(see gallery page 12), from the bastion of which this drawing was made. |

| |

"... A late Disdar, or Turkish governor, ascending the Acropolis, accompanied by a dervisch and a servant, when a Greek, seen incarcerated in the dungeon beneath the high tower built over part of the south wing in the middle ages was visited by his friends."

The "high tower" was the 14th century "Frankish Tower", built by the first Florentine Duke of Athens, Nerio I Acciaioli, and used as a prison during the Turkish occupation (see photo below). In 1875 Heinrich Schliemann paid to have the tower demolished amid the general drive to restore the Acropolis to its ancient Greek appearance and remove later Byzantine, Frankish and Ottoman buildings. During this process many parts of ancient monuments, used as building material for the later constructions, were recovered.

Of the fate of the Disdar Aga (see gallery page 32), who lived in the "Palace of the Acciaiuoli" in the Propylaia and kept his harem in the Erechtheion, and the Turks in the Acropolis, the editor adds:

"That venerable octogenary was one of the first victims, who, with a great part of the Turkish garrison of the Acropolis, were ferociously massacred by the Greeks and Christian Albanees, on the 10th of July 1822. They had surrendered, stipulating a safe passage to Smyrna according to a solemn treaty of capitulation! See Waddington's Visit to Greece, 1825."

Source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens (Volume 4): The antiquities of Athens and other places in Greece, Sicily etc.: supplementary to the antiquities of Athens. Antiquities at Athens and Delos, illustrated by William Kinnard, architect, Plate I. Extracts from the description of the plate, A view of the the west front of the Propylaea at Athens, pages 3-5. Priestley and Weale, London, 1830. At Heidelberg University Library. |

|

| |

A mid 19th century photo of the Propylaia, viewed from the east, inside the Acropolis. The 14th century

"Frankish Tower" can be seen at the south end of the gateway, and the five entrances are numbered.

Image source: Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, Fig. 39.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Acropolis

The Propylaia |

The sanctuary of Athena Hygieia |

|

|

|

The remains of the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia (centre), in front of the southern-most

column at the southeast corner of the east porch of the Propylaia (see plan above).

To the left (south) of the Propylaia is a rock wall marking the boundary of

the Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia. In the backgound (left), the south wing

of the Propylaia is surrounded by scaffolding during restoration work (2015).

|

On the right (south) immediately after entering the Acropolis through the east porch of the Propylaia, is the site of the small open-air shrine of Athena Hygieia. The remains consist of several marble bits and pieces, the most recognizable of which are the foundations and sides of the sanctuary's rectangular altar (see photo below) and a semicircular statue base inscribed with a dedication to Athena Hygieia (see photo right).

Athena Hygieia (Athena of Health) is thought to have been worshipped in Athens since at least the 6th century BC, long before the first sanctuary of Asklepios was established in the city (see the sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia on gallery page 34). At some point Hygieia (Ὑγιεία, Health), the goddess of Health, came to be seen as the daughter of Asklepios, and perhaps in some way subservient to the male health god. In Athens she also appears to have become associated with the city's patron goddess Athena, perhaps in a similar way to the victory goddess Nike (see Athena Nike on gallery pages 11-12).

Pausanias wrote that there was a statue of Hygieia and one of Athena Hygieia near the entrance to the Acropolis.

"Near the statue of Diitrephes – I do not wish to write of the less distinguished portraits – are figures of gods; of Health, whom legend calls daughter of Asclepius, and of Athena, also surnamed Health." [7]

The marble statue base, discovered in 1839, is inscribed with a dedication by the Athenians to Athena Hygieia and the signature of the sculptor Pyrrhos:

Ἀθεναῖοι τε͂ι Ἀθεναίαι τε͂ι Ὑγιείαι.

Πύρρος ἐποίησεν Ἀθεναῖος.

The Athenians (dedicated this) to Athena Hygieia.

Pyrrhos the Athenian made it.

Inscription IG I³ 506

The sculptor is thought to be the Pyrrhos (Latin, Pyrrhus) who Pliny the Elder wrote made bronze statues of Hygieia and Minerva (Athena) [8].

According to Plutarch, Pericles set up a bronze statue of Athena Hygieia near the altar of that goddess on the Acropolis after Athena appeared to him in a dream and instructed him how to heal a workman who had been injured during the building of the Propylaia [see note 1]. He also mentioned that the altar was said to have already stood there.

It has been suggested that this story may have been invented later, and that the statue may have been dedicated by the demos (people of Athens) around the time of the devastating plague that struck the city three times between 430 and 426 BC, during the Peloponnesian War. Pericles, who died in 429 BC, is said to have been among the victims of the plague (see the note on the foundation of the Asklepieion on gallery page 34).

One of the grounds for these suggestions is that the inscribed dedication on the statue base mentions "the Athenians" rather than Pericles. However, Plutarch did not write that Pericles set up the statue as a private dedication. It may have been Pericles' idea, but given the political circumstances at the time of the building of the Propylaia, there could have been a number of reasons for making the dedication a public rather than a private one. There is also no certainty that this statue was the one mentioned by Plutarch.

The semi-cylindrical form of the base is thought to have been designed so that the statue could stand directly before the column of the east porch of the Propylaia. This suggests that the statue was set up there after the completion of the gateway, but not necessarily that it was planned or made later. |

|

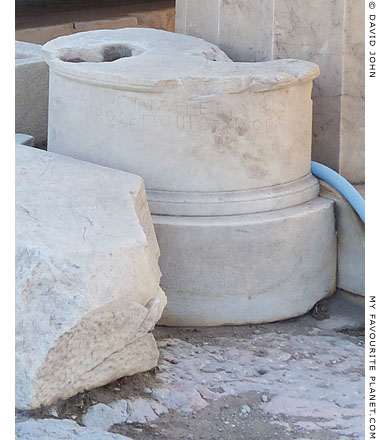

The inscribed base of the bronze statue

of Athena Hygieia, signed by Pyrrhos.

Around 430-425 BC.

Acropolis, Athens. Inv. No. ΜΑ 13259. |

|

| |

The site of the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia, at the southeast corner of the Propylaia.

On the left are the remains of a rectangular altar. On the right, next to a column of the Propylaia,

is the semicircular base of a bronze statue, thought to have been the cult statue of Athena Hygieia,

in front of which is part of the offering table for the statue (see reconstruction and plan below). |

| |

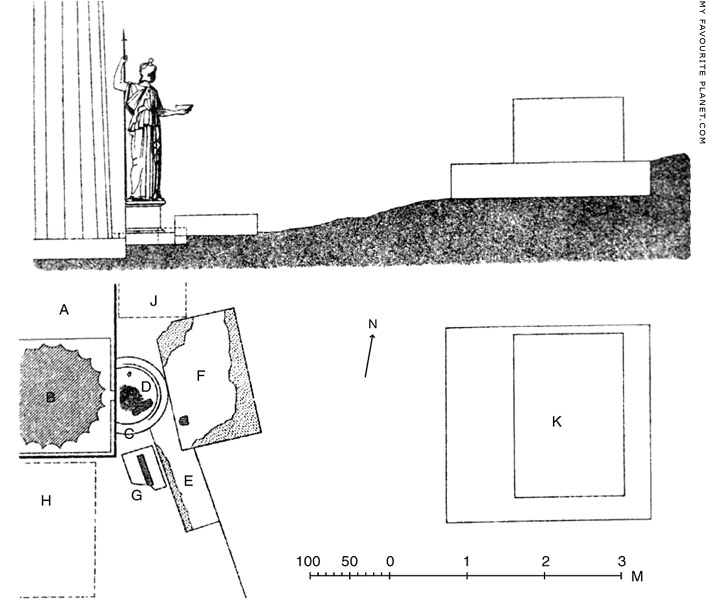

Reconstruction drawing and plan of the shrine of Athena Hygieia by the

German archaeologist and art historian Adolf Michaelis (1835-1910).

On the plan: A the stylobate of the Propylaia; B the southeast corner column of the Propylaia;

C the round block beneath the statue base; D the inscribed base of the Athena Hygieia statue;

F the base of the offering table; K the altar.

Source: Adolf Michaelis, Bemerkungen zur Periegese der Akropolis von Athen,

in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band I, 1876,

Viertes Heft, pages 275-307, plate XVI. Karl Wilberg, Athens, 1876. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Acropolis

The Propylaia |

Notes, references, links |

|

|

1. Plutarch (Πλούταρχος, name as Roman citizen Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, Μέστριος Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), Greek historian, biographer and essayist, born in Chaeronea, Boeotia.

"The Propylaia of the Acropolis were brought to completion in the space of five years, Mnesicles being their architect. A wonderful thing happened in the course of their building, which indicated that the goddess was not holding herself aloof, but was a helper both in the inception and in the completion of the work.

One of its artificers, the most active and zealous of them all, lost his footing and fell from a great height, and lay in a sorry plight, despaired of by the physicians. Pericles was much cast down at this, but the goddess appeared to him in a dream and prescribed a course of treatment for him to use, so that he speedily and easily healed the man. It was in commemoration of this that he set up the bronze statue of Athena Hygieia on the Acropolis near the altar of that goddess, which was there before, as they say."

Plutarch, Parallel lives, Pericles, chapter 13, sections 7-8. English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin. Harvard University Press and William Heinemann Ltd., London, 1916. At Perseus Digital Library.

See also: Plutarch's Lives, Volume I, Life of Pericles, XIII. Translated by Aubrey Stewart and George Long. George Bell & Sons, London & New York, 1894. At Project Gutenberg.

See the sanctuary of Athena Hygieia above.

Pliny the Elder related a similar anecdote concerning Pericles receiving a prescription from Athena in a dream to cure a favourite slave who fell from the roof of a temple on the Acropolis, presumably the Parthenon, during its construction.

"Perdieium or parthenium or, to give it yet another name, sideritis, is another plant, called by some of our countrymen urceolaris, by others astercoin. It has a leaf similar to that of basil, only darker, and it grows on tiles and among ruins. Pounded and sprinkled with a pinch of salt it cures the same diseases as dead-nettle, all of them, and is administered in the same way. The juice too taken hot is good for abscesses, and is remarkably good for convulsions, ruptures, bruises caused by slipping or by falling from a height, for instance, when vehicles overturn.

A household slave, a favourite of Pericles, first citizen of Athens, when engaged in building the temple on the Acropolis, crawled on the top of the high roof and fell. He is said to have been cured by this plant, which in a dream was prescribed to Pericles by Minerva; therefore it began to be called parthenium, and was consecrated to that goddess. This is the slave whose portrait was cast in bronze, the famous Entrail Roaster."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 22, chapter 20. At Jon Lange's Masseiana website.

Pliny also wrote that the bronze statue of the "Entrail Roaster" (σπλαγχνόπτης, splanchnoptes, man cooking intestines) was made by the Cypriot sculptor Styppax (Στύππαξ).

"Stypax of Cyprus acquired his celebrity by a single work, the statue of the Splanchnoptes, which represents a slave of the Olympian Pericles, roasting entrails and kindling the fire with his breath."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19, "An account of the most celebrated works in brass, and the artists, 366 in number". At Perseus Digital Library.

A fragmentary marble statue found in the Olympieon, Athens, is thought to be part of a Roman period copy of the splanchnoptes by Styppax. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 248. The subject was also painted on Greek pottery, including an Attic red-figure stamnos attributed to Polygnotus, 450-430 BC, in the British Museum.

2. Artworks at the Propylaia mentioned by Pausanias

"the statues of the horsemen", see the Pedestal of Agrippa.

"temple of Wingless Victory", see the Temple of Athena Nike.

The paintings in the Pinakotheke mentioned by Pausanias include a number depicting scenes from the Trojan War, most of which were narrated by Homer:

Diomedes taking the statue of Pallas Athena from Troy;

Odysseus on Lemnos taking away the bow of Philoctetes;

Orestes killing Aegisthus;

Pylades killing the sons of Nauplius who had come to bring Aegisthus succor;

Polyxena about to be sacrificed near the grave of Achilles (not mentioned by Homer);

Achilles in Scyros with the maidens, the daughters of King Lykomedes of Skyros (not mentioned by Homer), by Polygnotus (Polygnotos of Thasos?);

Odysseus coming upon the women washing clothes with Nausica at the river by Polygnotus.

Other paintings in the Pinakotheke:

a portrait of Alcibiades, with victory emblems his horses won at the Nemean Games;

Perseus carrying the head of Medusa to Polydectes on Seriphos;

a boy carrying the water jars;

a wrestler by Timaenetus;

a portrait of the poet Musaeus, who wrote a hymn to Demeter for the Lycomidae.

Sculptures in front of the Propylaia:

a Hermes (called Hermes of the Gateway), see Pergamon gallery 2, page 15;

figures of Graces, "which tradition says were sculptured by Socrates, the son of Sophroniscus, who the Pythia testified was the wisest of men". See Sokrates on Ancient Greek artists, page 6.

Pausanias goes on (chapter 23) to mention other sculptures near the Propylaia: a "statue of Diitrephes pierced with arrows" (see Kresilas), some "less distinguished portraits", as well as statues of Hygieia and Athena Hygieia (see above). He also noticed a stone on which, according to legend, "Silenus rested when Dionysus came to the land" (see gallery page 36). |

|

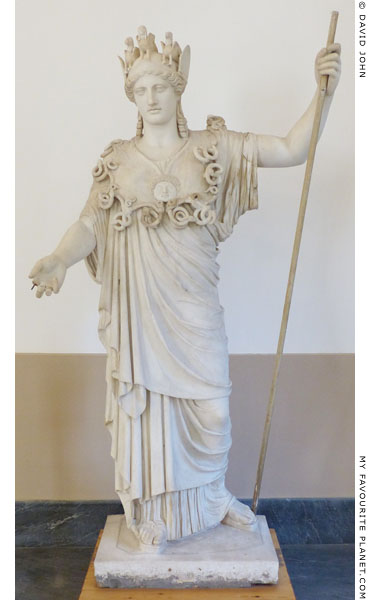

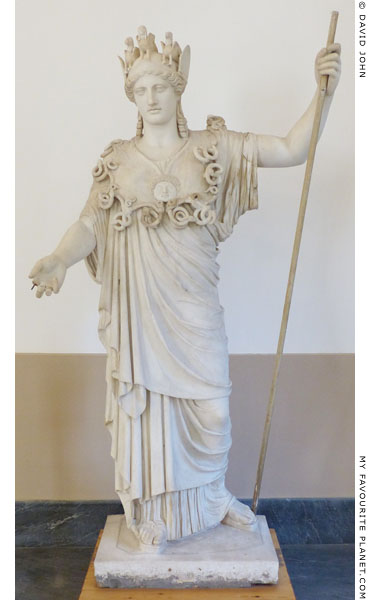

The "Athena Farnese", a restored Roman period

marble statue of Athena. One of a number of similar

sculptures of the Athena Hope-Albani/Farnese type,

thought to be copies of the Classical bronze original

by Pyrrhos, set up by Pericles on the Acropolis.

Found 1743 in Rome. Referred to by the art historian

Johann Joachim Winckelmann as "Pallas Albani",

the statue disappeared for a while, probably due to

Napoleonic confiscation in 1798. It resurfaced in 1805

in Naples as "Athena Albani-Farnese". Height 224 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6024. From the Albani Collection,

then the Farnese Collection.

See details of the Gorgoneion and Aegis

of this statue on the Gorgon Medusa

page in the MFP People section. |

|

|

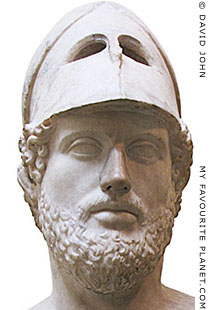

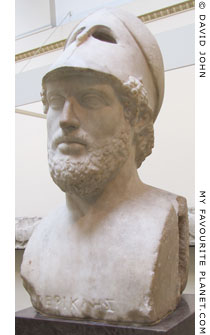

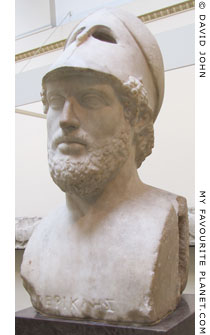

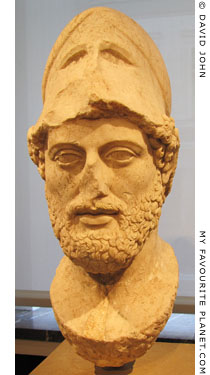

3. Bust of Pericles with the Corinthian Helmet

British Museum, London. Inv. No. GR 1805.7-3.91 (Sculpture 549).

2nd century AD.

Marble. Height 58.42 cm.

Inscription on the base (Inscription 1097) ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ (Perikles).

Museum label: "Roman, 2nd century AD copy of a lost original of around 440-430 BC"

Known as the "Townley Pericles", the bust is in the form of a "terminus", i.e. the top part of a herm. Terminus was the Roman god who protected boundaries, and stone pillars known in Latin as terminii were set up as boundary markers in a similar way to which herms were used by the Greeks. Such busts of gods and famous humans were made for the private collections of wealthy people.

This bust was found in 1780 at Emperor Hadrian's villa in Tivoli, near Rome, and purchased in 1783 by the Scottish artist and antiquities dealer Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798) for the private collection of the wealthy English gentleman Charles Townley (1737-1805). It was acquired, along with around 300 ancient artefacts of the Townley Collection, by the British Museum after Townley's death.

It was one of three similar marble busts of Pericles (circa 495 - 429 BC) found in Rome 1779-1780, one of which, now in the Vatican, bears the inscription ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ ΞΑΝΘΙΠΠΟΥ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ (Pericles, son of Xanthippos, Athenian).

Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 269.

2nd century AD.

Height 183 cm.

Found during the pontificate Pope Pius VI of (1775-1799) at the Villa Tiburtina of Cassius, Tivoli.

The identification of the busts as portraits of Pericles has led scholars to believe that they are copies of a statue of the Athenian general and statesman by Kresilas (Κρησίλας, circa 480-410 BC), mentioned by Pliny the Elder:

"Cresilas executed a statue of a man fainting from his wounds, in the expression of which may be seen how little life remains; as also the Olympian Pericles, well worthy of its title: indeed, it is one of the marvellous adjuncts of this art, that it renders men who are already celebrated even more so."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

A mention by Pausanias of a statue of Pericles on the Acropolis has also been taken as a reference to this work by Kresilas.

"On the Athenian Acropolis is a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and one of Xanthippus himself, who fought against the Persians at the naval battle of Mycale. But that of Pericles stands apart, while near Xanthippos stands Anacreon of Teos..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book I, chapter 25, section 1. Translation by W. H. S. Jones and H. A. Ormerod. Published in 4 Volumes by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1918. At Perseus Digital Library.

He also mentions an Athenian dedication to Pericles in Book I, chapter 28, section 2.

The base of a bronze statue discovered on the Acropolis is thought to be that of the work mentioned by Pausanias. The question of whether the statue was made during the lifetime of Pericles or after his death in 429 BC remains open, as the original has been lost. However, many recent references, including museum descriptions, prefer a date between 440 and 430 BC.

The third, not so well sculpted marble bust from around Rome is in the Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums.

A marble head of Pericles, made for a statue rather than as a bust, is very similar to the examples in the Brtitish Museum and Museo Pio-Clementino. It was found on the Greek island of Lesbos and is now in the Altes Museum, Berlin (see photo right).

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1530 (K 127).

Height 53 cm.

Museum label: "Roman, after an original from around 430 BC"

Found on Lesbos. Purchased in 1901 from Dr. Kjellberg in Upsala for 6000 marks. |

The herm bust of Pericles in

the British Museum with the

inscription ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ (Perikles). |

| |

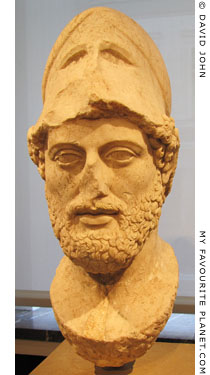

Marble head from a statue

of Pericles. From Lesbos.

Roman period copy "after an

original from around 430 BC".

Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. SK 1530.

Acquired in 1901. |

| |

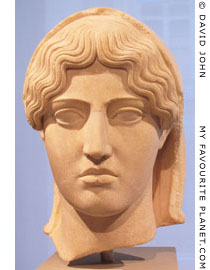

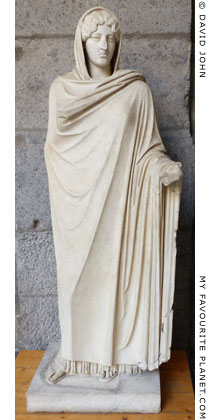

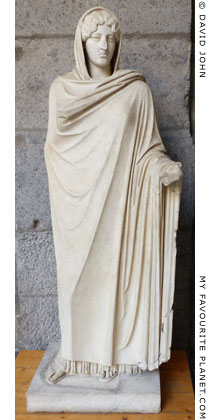

4. Head of so-called "Aspasia"

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 605.

Marble. Height 29.5 cm (approximately lifesize).

Museum label: "Roman, after a model from around 470/460 BC"

Acquired by the old Royal Prussian Collection in 1742. In 1799 in the library of Friedrich II's Neue Palais, Sanssouci, Potsdam. Transferred to the Königliche Museum, Berlin in 1830.

The head is one of over 30 sculptures of a type known variously as "Aspasia", "Sosandra", "Aphrodite Sosandra", "Aspasia/Sosandra", "Europa" or "Amelung's Goddess". All sculptures of the type show a woman draped in a himetion (long woollen cloak), part of which covers the top and back of her head like a cowl. Her hair is parted in the middle and tied back so that it falls diagonally to either side of her forehead in waves. Her face, solemn and austere, has been sculpted in a way which has been associated with the severe style of Classical Greek sculpture.

Statues and reliefs of women draped and "veiled" in cloaks (wearing a καλύπτρα, kalyptra, veil, headdress) were very common in antiquity, most often on funeral monuments showing the subject as the deceased or as a widow. However, men and women were also depicted in this manner as priests, and some deities are also shown hooded.

The association of this statue type with Aspasia of Miletus stems from a marble herm, discovered in 1777 near Civitavecchia, which bears the inscription ΑCΠΑCΙΑ (= ΑΣΠΑΣΙΑ, Aspasia). It is so far the only known sculpture with such an inscription, and many scholars have doubted its authenticity, pointing also to problems of reconciling the style of the sculpture with the time of Aspasia's life, as well as the fact that no statue of Aspasia is mentioned by ancient authors. Wealthy Romans had a preoccupation with acquiring portraits of famous historical personalities, and there are many examples of dubious labelling of statues from ancient collections.

Marble herm bust of "Aspasia" in Rome (see drawing, above right)

Sala delle Muse, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 272.

Height 170 cm.

Identified by the inscription ΑCΠΑCΙΑ (= ΑΣΠΑΣΙΑ) on the base.

Inscription on front of stele: MVN. PIT. SEXTI. P. M

Found in 1777 at Torre della Chiarrucia (Castrum Novum) near Civitavecchia (80 km northwest of Rome).

Thought to be a Roman copy of the first half of the 2nd century AD after an Hellenistic original of the 4th century BC.

Another theory is that the type depicts a statue of Sosandra (Σωσάνδρα, saviour of men) by the 5th century BC sculptor Kalamis (Kαλαμις) which stood on the Acropolis and was mentioned by the Syrian essayist Lucian of Samosata (Greek, Λουκιανός ὁ Σαμοσατεύς; Latin, Lucianus Samosatensis; circa 125-180 AD) in A portrait study (Greek, Εἰκόνες; Latin, Imagines).

See: A portrait study, in The works of Lucian of Samosata, Volume 3 (of 4). Translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler. At Project Gutenberg.

The sculpture mentioned by Lucian has in turn been identified with a statue of Aphrodite by Kalamis which, according to Pausanias, stood near the entrance to the Acropolis, and was dedicated by Kallias (Καλλίας, circa 500-432 BC), the wealthy brother-in-law of Kimon, and a supporter of Pericles.

Pausanias's Description of Greece, Volume 1 (of 6), Book I, Chapter 23, sections 1-2, page 32. Translated with a commentary by James George Frazer. Macmillan and Co., London, 1898. At the Internet Archive.

Possibly the best known statue of "Aphrodite Sosandra" is in Naples (see photo, right):

Statue of "Aphrodite Sosandra" in Naples

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 153654.

Marble. Height 183 cm.

Roman copy of a Greek original of around 460-450 BC.

Found in 1950 in the "Sector of Sosandra" at Baiae, Bay of Naples. The statue was unfinished and almost completely unpolished. It is believed that a workshop at Baiae mass-produced marble or bronze copies of Hellenistic and Greek sculptures for the Roman market from original works. |

| |

Drawing of the marble herm

bust in the Vatican, showing

the inscription "ΑCΠΑCΙΑ"

on the right side.

Height 170 cm.

Sala delle Muse, Museo

Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Museums. Inv. No. 272. |

| |

One of the finest examples of

the "Aphrodite Sosandra" type

marble statue. Roman period.

Found in 1950 at Baiae in the

Bay of Naples. Height 183 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 153654. |

| |

|

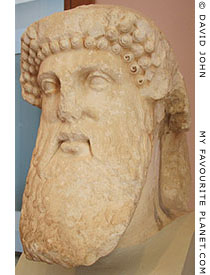

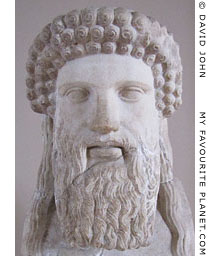

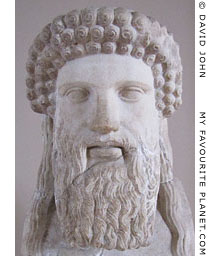

5. Head of "Hermes Propylaios" in the Acropolis Museum

A herm head of the "Pergamon type", made of Pentelic marble in the first century BC. Found on the Athens Acropolis and now in the Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. Acr. 2281.

As with the similar herm of Hermes from Pergamon (see photo, right), which gave this type its name, it has three rows of snailshell curls framing the forehead and symmetrical groups of curls on the beard. It also originally had two long hair locks (ringlets), now missing, which fell from behind the ears, with an end resting on each shoulder.

The head is badly damaged and discoloured, and the missing herm shaft has been replaced by a simplified modern reconstruction. The eyes, cheeks and mouth suggest a cheerful-looking Hermes, with a trace of the enigmatic smile found on Archaic statues, such kores, but rarer on the generally more earnest faces of Classical sculptures (see the portraits of Pericles and Aspasia above).

I have not yet found any recent literature which examines this sculpture in any depth; it is usually mentioned briefly in relation to the Pergamon herm.

See further information about the two types of "Hermes Propylaios" herms - the Pergamon type and the Ephesos type - in the illustrated article about the "Hermes Propylaios" from Pergamon in Pergamon gallery 2, page 15.

See also a short description and photo of this head:

Ismini Trianti, The Acropolis Museum, pages 395 and 402.

Eurobank / Latsis Group. Published by OLKOS, Athens, 1998.

E-book in English and Greek.

This book is part of the excellent series, "The Museums Cycle", produced by the John S. Latsis Public Benefit Foundation. The large, lavishly illustrated volumes are excellent guides to some of Greece's finest museums. However, they are very heavy: the book about the Archaeological Museum of Pella (the best book about Pella I have yet seen), for example, weighs 3.5 kg. This means that visitors are hardly likely to want to lug them around museums or archaeological sites, and they would cerainly put a strain on your airline baggage allowance.

However, since the guides are produced as limited editions for libraries and institutions, they are not on sale in bookshops. Fortunately, the Latsis Group have provided their electronic library, so that they can be read online as e-books. |

|

The head of the Pergamon

"Hermes Propylaios" herm.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 1433 T. Cat. Mendel 527.

See the photos and article on

Pergamon gallery 2, page 15. |

|

6. Vitruvius on entasis

"These proportionate enlargements are made in the thickness of columns on account of the different heights to which the eye has to climb. For the eye is always in search of beauty, and if we do not gratify its desire for pleasure by a proportionate enlargement in these measures, and thus make compensation for ocular deception, a clumsy and awkward appearance will be presented to the beholder. With regard to the enlargement made at the middle of columns, which among the Greeks is called entasis, at the end of the book a figure and calculation will be subjoined, showing how an agreeable and appropriate effect may be produced by it."

See: Ten Books on Architecture by Vitruvius, translated by Morris Hicky Morgan and Albert A. Howard. Book III, Temples and the orders of architecture; Chapter III, The Proportions of Intercolumniations and of Columns, section 13. At wikisource.org.

See the Vitruvius page in the MFP People section.

7. Pausanias on statues of Hygieia and Athena Hygieia near the Propylaia

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

8. Pliny the Elder on Pyrrhos

Pliny mentioned a sculptor named Pyrrhos among a long list of sculptors who worked in bronze.

"Polycles made a splendid statue of Hermaphroditus; Pyrrhus, statues of Hygeia and Minerva; and Phanis, who was a pupil of Lysippus, an Epithyusa."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19 ("An account of the most celebrated works in brass, and the artists, 366 in number"). At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

The view westwards from the east porch of the Propylaia to the Saronic Gulf. |

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contents | contributors | impressum | sitemap |

|

|