1. Pliny on Aetion the sculptor

"An almost innumerable multitude of artists have been rendered famous by their statues and figures of smaller size. Before all others is Phidias, the Athenian, who executed the Jupiter [Zeus] at Olympia, in ivory and gold, but who also made figures in brass as well. He flourished in the eighty-third Olympiad, about the year of our City, 300. ... in the hundred and seventh [Olympiad], Aetion and Therimachus..."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19.

2. Pliny on Aetion the painter

"In the hundred and seventh Olympiad, flourished Aetion and Therimachus. By the former we have some fine pictures; a Father Liber, Tragedy and Comedy, Semiramis from the rank of a slave elevated to the throne, an Old Woman bearing torches, and a New-made Bride, remarkable for the air of modesty with which she is portrayed."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, chapter 36.

Pliny also wrote that Aetion (in this translation rendered as "Echion") painted with only four colours. This is thought to have been an "imperfect recollection" of the passage in Cicero's Brutus (see below).

"It was with four colours only, that Apelles, Echion [sic], Melanthius, and Nicomachus, those most illustrous painters, executed their immortal works; melinum for the white, Attic sil for the yellow, Pontic sinopis for the red, and atramentum for the black; and yet a single picture of theirs has sold before now for the treasures of whole cities."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 35, chapter 32.

All Pliny quotes from the translation by John Bostock and H. T. Riley. Taylor and Francis, London, 1855. At Perseus Digital Library.

Another online translation of Pliny's Natural History has the entire book on a single web page:

Pliny's Natural History, translated by H. Rackham, W.H.S. Jones and D.E. Eichholz, in 10 volumes. Harvard University Press, MA; William Heinemann, London, 1949-54. At Jon Lange's masseiana.org.

In this translation, the artists who Pliny wrote used "four colours only" (Book 35, chapter 32) are named as "Apelles, Action, Melanthius and Nicomachus". Aetion is named in the other passages (Book 34, chapter 19; Book 35, chapter 36).

3. Cicero on Aetion the painter

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) was a Roman philosopher, lawyer, orator, politician and political theorist. From a wealthy family, he served as consul, and is considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose authors. Brutus (also known as De claris oratibus) is a history of oratory, written about 46 BC in the form of a dialogue.

"But who that has seen the statues of the moderns, will not perceive in a moment, that the figures of Canachus are too stiff and formal to resemble life? Those of Calamis, though evidently harsh, are somewhat softer. Even the statues of Myron are not sufficiently alive; and yet you would not hesitate to pronounce them beautiful. But those of Polycletes are much finer, and, in my mind, completely finished.

The case is the same in painting; for in the works of Zeuxis, Polygnotus, Timanthes, and several other masters who confined themselves to the use of four colours, we commend the air and the symmetry of their figures; but in Aetion, Nicomachus, Protogenes, and Apelles, everything is finished to perfection *."

* In Latin: "... at in Aetione Nicomacho Protogene Apelle iam perfecta sunt omnia."

Marcus Tullius Cicero, Brutus, a history of famous orators, section 70.

Translated by E. Jones (1776). At attalus.org.

Also: Cicero's Brutus or History of famous orators; also his Orator, or Accomplished speaker. Translated by E. Jones. At Project Gutenberg.

M. Tulli Ciceronis Brutus. At The Latin Library.

4. Roxana

Roxana (Ῥωξάνη, circa 340-310 BC), also referred to as Roxane and Roxandra, was a Sogdian princess of Bactria whom Alexander married in 327 BC. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Roxana and their son Alexander IV were protected by Alexander's mother, Olympias, in Macedonia. Olympias is thought to have been captured around 316 BC at Pydna and perhaps killed by Cassander (see History of Stageira and Olympiada part 6), who is said to have imprisoned Roxana and Alexander in Amphipolis and ordered them to be poisoned around 310 BC.

5. Lucian on Aetion the painter - the Fowler translation

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, Latin, Lucianus Samosatensis; circa 125 - after 180 AD) was a rhetorician and satirist from the Roman province of Syria who wrote rhetorical essays, satirical dialogues and prose fiction in Greek. Around 70 works attributed to him have survived.

Lucian's description of Aetion's painting of the wedding of Alexander and Roxana is part of Herodotus or Aetion (Ἡρόδοτος ή Ἀετίων), a lecture ("introduction") delivered at a festival in a Macedonian city.

"However, I need not have cited ancient rhetoricians, historians, and chroniclers like these; in quite recent times the painter Aetion is said to have brought his picture, Nuptials of Roxana and Alexander, to exhibit at Olympia; and Proxenides, High Steward of the Games on the occasion, was so delighted with his genius that he gave him his daughter."

Herodotus or Aetion, chapter 20, in The Works of Lucian of Samosata, Complete with exceptions specified in the preface, Volume 2 (of 4). Translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler (following the text of Jacobitz, Teubner, 1901). Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1905. ebooks at the University of Adelaide.

6. Lucian on Aetion the painter - the Kilburn translation

"But why need I mention those old sophists, historians, and chroniclers when there is the recent story of Aetion the painter who showed off his picture of The Marriage of Roxana and Alexander at Olympia? Proxenides, one of the chief judges there at that time, was delighted with his talent and made Aetion his son-in-law.

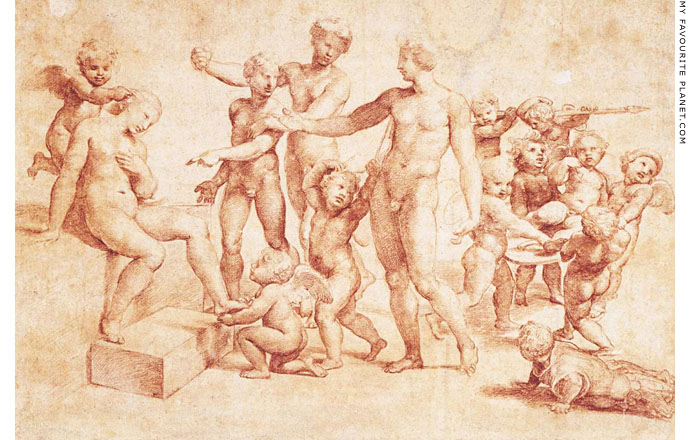

You may well wonder at the quality of his work that induced a chief judge of the games to give his daughter in marriage to a stranger like Aetion. The picture is actually in Italy; I have seen it myself and can describe it to you.

The scene is a very beautiful chamber, and in it there is a bridal couch with Roxana, a very lovely maiden, sitting upon it, her eyes cast down in modesty, for Alexander is standing there. There are smiling Cupids: one is standing behind her removing the veil from her head and showing Roxana to her husband ; another like a true servant is taking the sandal off her foot, already preparing her for bed; a third Cupid has hold of Alexander's cloak and is pulling him with all his might towards Roxana.

The king himself is holding out a garland to the maiden and their best man and helper, Hephaestion, is there with a blazing torch in his hand, leaning on a very handsome youth – I think he is Hymenaeus [god of marriages] (his name is not inscribed). On the other side of the picture are more Cupids playing among Alexander's armour; two of them are carrying his spear, pretending to be labourers burdened under a beam; two others are dragging a third, their king no doubt, on the shield, holding it by the handgrips; another has gone inside the corselet, which is lying breast-up on the ground - he seems to be lying in ambush to frighten the others when they drag the shield past him.

All this is not needless triviality and a waste of labour. Aetion is calling attention to Alexander's other love – War – implying that in his love of Roxana he did not forget his armour. A further point about the picture itself is that it had a real matrimonial significance of quite a different sort – it courted Proxenides' daughter for Aetion! So as a by-product of his Alexander's Wedding he came away with a wife himself and the King for best man. His reward for his marriage of the imagination was a real-life marriage of his own."

Herodotus or Aetion (Ἡρόδοτος ή Ἀετίων), pages 139-151 (the extract on Aetion on pages 144-149), in Lucian, with an English translation by K. Kilburn, Volume VI (of eight). William Heinemann, London; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1959. Parallel texts in Greek and English. At the Internet Archive.

7. Roman looting of Greek art

As the Romans expanded their territory, they conquered Greek cities of the Italian mainland (Magna Graecia) and Sicily. During their military campaigns from the Hellenistic period onwards they also acquired Greek artworks from the Greek mainland, islands, Macedonia, Thrace and Anatolia (Asia Minor). The last Attalid king Attalus III (ruled 138-133 BC) bequeathed the enormous territories of the kingdom of Pergamon to the Roman Republic. The populist politician Tiberius Gracchus (162-133 BC) planned to use the inherited wealth of Pergamon to finance his radical land reforms, and even proposed selling off its artworks to raise capital (see History of Pergamon). Roman authors, particularly Pliny the Elder, mentioned numerous Greek artworks which had been taken to Rome by generals, governors and emperors for private and public collections.

8. The Alexander fresco from Pompeii

Stateira II (Στάτειρα, died 323 BC), also referred to as Barsine, was the daughter of Darius III of Persia and Stateira I. After Alexander defeated Darius at the Battle of Issos in 333 BC, Darius' mother and wife, as well as Stateira and her sisters became Alexander's captives. Stateira became Alexander's second wife in 324 BC at the mass Susa weddings, during which he also married her cousin, Parysatis. She is said to have been killed by Roxana and Perdiccas shortly after Alexander's death.

The wall painting of the early Fourth Pompeiian style (also known as the "Intricate style", circa 50-79 AD) was discovered on the south wall of triclinium 20, overlooking the garden, in the House of Golden Bracelet (Casa del Bracciale d'Oro), initially named the House of the Wedding of Alexander (Casa delle Nozze di Alessandro, also referred to as the House of the Wedding of Alexander and Roxane) after the painting, Regio VI, Insula 17 (Insula Occidentalis), Entrance 42 (VI,17,42), Lower Level. The insula (block) is at the northwestern edge of the Pompeii archaeological site, near the Herculaneum Gate.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 41657.

Height 155 cm, width 143 cm.

Apparently the fresco is now in the Antiquarium of Pompeii, which was reopened in 2016 after being closed for 36 years following an earthquake.

See: www.pompeiiinpictures.com ...

9. Theocritus on Aetion the sculptor

Theocritus (Θεόκριτος, Theokritos, flourished in the first half of the 3rd century BC) is credited as being the inventor of bucolic poetry. Based on the internal evidence of his poems, he is thought to have been from Syracuse, Sicily, to have lived for a while on the Greek island of Kos, and to have worked at Alexandria, Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphos (309-246 BC, ruled 285-246 BC). He is best known for his Idylls (Εἰδύλλια, Eidyllia) and Epigrams (Επιγράμματα, Epigrammata).

It has been generally accepted that the epigram "On a statue of Asklepios" (Epigram 7 in some publications, Epigram 8 in others; in the Palatine Anthology, Book VI, 337) was written by Theocritus. The poem of six lines tells of a cedar wood statue of the healing god set up by his friend Nikias (Νικίας, estimated to have been born circa 310 BC), known as Nikias of Miletus (ἰατρῷ Νικίᾳ Μιλησίῳ), a doctor who had been a pupil of the Epicurean philosopher Metrodoros of Lampaskos (Μητρόδωρος Λαμψακηνός, 331/330 - 278/277 BC).

Nikias is mentioned in three other poems of Theocritus, Idylls 11, 13 and 28. Idyll 11, "The Cyclops" (Κύκλωψ, also known as "Polyphemus in love" or "Polyphemus' complaint"), was addressed directly to Nikias as "a doctor" and "very dear to the Nine Muses". The first two lines of Nikias' reply to this poem were quoted by an ancient scholiast: "What you say is true, Theocritus: The god of love has taught poetry to many who were before without a muse..." Nikias is also thought to be the author of eight of surviving epigrams.

Translations of "On a statue of Asklepios" into English since the 18th century (including Francis Fawkes, 1767) have been based on a Greek text in which the name the sculptor appears as ᾿Ηετίωνι (Hetioni or Eetioni). Eëtion is known as the name of the father of the 7th century BC Corinthian tyrant Kypselos (Herodotus, Histories, Book 1, chapter 14) and a number of legendary or mythical characters (several mentions, for example, in Homer, The Iliad). However, Eetion as the name of a sculptor appears to have been unknown to some scholars, and at least one translator (Charles Stuart Calverley, 1869) simply ignored it and wrote "the sculptor".

Epigram 8, For a statue of Asclepius

Ηλθε καὶ ἐς Μίλητον ὁ τοῦ Παιήονος υἱός,

ἰητῆρι νόσων ἀνδρὶ συνοισόμενος

Νικίᾳ, ὅς μιν ἐπ᾽ ἦμαρ ἀεὶ θυέεσσιν ἱκνεῖται,

καὶ τόδ᾽ ἀπ᾽ εὐώδους γλύψατ᾽ ἄγαλμα κέδρου,

᾿Ηετίωνι χάριν γλαφυρᾶς χερὸς ἄκρον ὑποστὰς

μισθόν: ὁ δ᾽ εἰς ἔργον πᾶσαν ἀφῆκε τέχνην.

R. J. Cholmeley (editor), Theocritus, Epigrams, A Pal vi.337. George Bell & Sons, London, 1901. At Perseus Digital Library.

Cholmeley noted: "The epigram refers to a statue of Aesculapius set up by Nicias and carved for him by Eetion, but it obviously was not intended to be engraved on the pedestal."

Epigram VII, On the Statue of Aesculapius

Literal translation by Rev. J. Banks (1820-1883), page 159 **.

The son of Paean came even to Miletus, to dwell along

with a man that heals diseases, Nicias by name: who ever

day by day approaches him with sacrifices, and has had this

statue carved out of fragrant cedar, having promised the

highest price to Eetion, because of his skilful hand; and he

has thrown all his art into the work.

Epigram VIII, On a statue of Aesculapius

Verse translation by J. M. Chapman, page 297 **.

The son of Paean to Miletus came,

And with the best physician Nicias, staid,

Who, daily kindling sacrificial flame,

From fragrant cedar had this statue made.

The highest price was paid Eetion's fame,

Who all his skill upon the work outlaid.

** Both translations from: The idylls of Theocritus, Bion, and Moschus, and The war-songs of Tyrtreus. Literally translated into English prose by the Rev. J. Banks, with metrical versions by J. M. Chapman. George Bell and Sons, London, 1888. At the Internet Archive.

"The son of Paean" refers to Paean (there are various Greek spellings, including Παιήων, Paion, healer, helper), the physician of the Olympian gods. Although thought by some to have been a separate god, the name became associated with Apollo and was one of his epiphets. Later, it also became an epithet of Apollo's son Asklepios (Latin, Aesculapius), the god of healing.

In the 1980s the British poet Robert Wells translated the Idylls and Epigrams of Theocritus in clear, thoughtful and elegant verse, with an excellent introduction and notes. The original hardback edition is now out of print, but can still be purchased online, as can the Penguin Classics paperback edition. The translations have recently been republished by Carcanet Press in the Collected Poems and Translations of Robert Wells.

The Idylls of Theocritus, translated by Robert Wells. Hardcover. Carcanet Press, Manchester, England, 1988.

Theocritus, The Idylls, translated by Robert Wells. Paperback. Penguin Classics, 1989.

Robert Wells, Collected Poems and Translations. Paperback, 306 pages. Carcanet Press, Manchester, England, 2009.

10. Callimachus on Aetion the sculptor (?)

Callimachus (Καλλίμαχος, Kallimachos, 310/305–240 BC), from the Greek colony of Cyrene, Libya. A poet, critic and scholar at the Library of Alexandria, Egypt during the reigns of the Ptolemaic kings Ptolemy II Philadelphos and Ptolemy III Euergetes.

The epigram has not been given a title and is numbered differently in various anthologies (the order of the epigrams is not canonical), but usually referred to by its order in the Greek Anthology: Anthologia Graeca, Book IX, 336 (see below). The Greek text has been described as difficult, obscure and perhaps corrupt, and the translations and interpretations are so varied as to change the sense of the poem completely.

There is no indication of whether the poem was written for a particular occasion or person, or merely Callimachus musing on something he has seen or heard about. It mentions "Aetion of Amphipolis" (Αἰετίωνος ἐπίσταθμος Ἀμφιπολίτεω), and is thought to concern a small sculpture made by him, depicting an unmounted, unnamed hero with a sword and a snake. However, Aetion ("Eetion" in some of the translations below) could just as well be the name of the dead hero, the commissioner of the sculpture (as Nikias commissioned the statue of Asklepios) or the owner of the building at which it then stood.

Statues and reliefs of heroes, as grave markers and hero cult icons, were set up to honour dead male comrades, relatives, dignitaries and rulers. They became increasingly popular in Thrace and Greece from the late Classical and Hellenistic periods. The deceased hero is usually depicted as a warrior and horseman, and snakes are a usual part of the iconography. See photos and information about hero reliefs on Pergamon gallery 2, page 10.

Translators have conjectured that the sculpted figure is unmounted because he was either killed by a fall from a horse, or because Aetion was of Trojan descent, and hated the idea of a horse because of the wooden horse made by Epeius (see Homer part 3). The notion that the figure stands in front of a stable (according the first translation below) strikes a tone of irony.

Callimachus, Epigram 24

Ήρως Αἰετίωνος ἐπίσταθμος Ἀμφιπολίτεω

ἵδρυμαι μικρῶι μικρὸς ἐπὶ προθύρωι

λοξὸν ὄφιν καὶ μοῦνον ἔχων ξίφος: ἀνδρὶ ιπειωι

θυμωθεὶς πεζὸν κἀμὲ παρωικίσατο.

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (editor), Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams, Epigram 24 (Palatine Anthology, Book IX, Epigram 336). Weidmann, Berlin 1897. At Perseus Digital Library.

Epigram 336 - Callimachus

"I, the hero who guard the stable of Aetion of Amphipolis, stand here, small myself and in a small porch, carrying nothing but a wriggling snake and a sword. Having lost his temper with .... he did not give me a mount either when he put me up beside him."

William Roger Paton (1857-1921), translator, The Greek anthology Volume III (of five), Book IX, The Declamatory Epigrams, pages 180-183, "336 - Callimachus". William Heinemann, London; G. P. Putnam's sons, New York, 1916. Parallel texts in Greek and English. At the Internet Archive.

Callimachus, Epigram XXV

Literal translation by James Davies (Rev. J. Banks, 1820-1883), page 199. ***

"A hero, I am set before the door of Eetion, of Amphipolis, a little hero at a small vestibule, bearing a snake looking askance and a sword only. But being enraged at a horseman, he has placed me also near himself on-foot."

Callimachus, Epigram XXV

Verse translation by Henry William Tytler, page 424.***

Small is my size, and I must grace

Eetion's porch, a little place;

A hero's likeness I appear,

And round my sword a serpent bear.

But since Eetion views with hate

The prancing steed that caus'd my fate,

Resolv'd that we no more should meet,

He plac'd me here upon my feet.

*** Both translations from: The works of Hesiod, Callimachus, and Theognis. Literal translations by James Davies (Rev. J. Banks, 1820-1883); metrical translations by Sir Charles Abraham Elton (1778-1853), Henry William Tytler (1752-1808), John Hookham Frere (1769-1846). H. G. Bohn, London, 1856. At the Internet Archive.

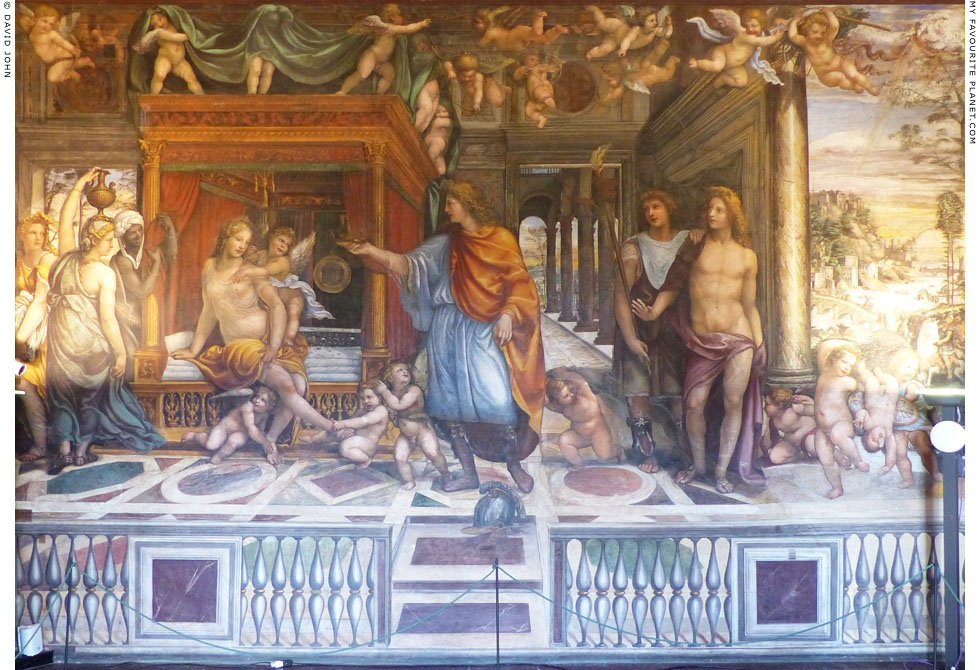

11. The date of Sodoma's Alexander frescoes

The dating of Sodoma's three Alexander frescoes in the Villa Farnesina remains a matter of debate. The traditional date of 1509-1510 is based on the assumption that Sodoma worked at the villa during his first stay in Rome, around 1508-1510, following his first meeting with Agostino Chigi in Siena in 1507. He is known to have been working in a house of Agostino's brother Sigismondo in Trastevere in 1508, and from October 1508 until the middle of 1509 he worked in the Vatican Rooms, before his place was taken by Raphael. By October 1510 he had returned to Siena. However, a letter from the scholar Aretino to Sodoma indicates that both men were at the villa in 1513. Again, Sodoma is known to have been in Siena at the beginning of 1514.

One hypothesis (A. Hayum, 1966, see below) dates the frescoes to 1517, whereas the villa's labelling states 1519, and according to a recent book (Vincenzi, 2014, see below) the bedroom was decorated before Chigi's own wedding to Francesca Ordeaschi on 28 August 1519 (Sant' Agostina's day), which was officiated by Pope Leo X.

It has been pointed out that the other two Alexander frescoes are much harsher in style than the wedding, and thus may have been painted at a later date. The frescoes were restored 1974-1976.

See:

A. Hayum, A new dating for Sodoma's frescoes in the Villa Farnesina, in The Art Bulletin, 1966, pages 215-217.

Elsa Gerlini, The Villa Farnesina alla Lungara, Rome, pages 66-73. Instituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A., Rome, 2006.

Alessandro Vincenzi (editor), The Villa Farnesina in Rome, pages 90-95. Franco Cosimo Panini Editore S.p.A., Modena, 2014.

The illustrated guidebooks by Gerlini and Vincenzi can be purchased in the bookshop of the villa at 10 Euros each.

Some people believe that the Villa Farnesina should be called Villa Chigi after its builder. Vasari referred to it as "the Chigi", but it came into the possession of the Farnese family after being purchased by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese around 1579 (sources differ on the exact date).

12. The fourth Alexander fresco

Although the left side (above the door) and part of the right side of the fourth fresco of the Room of the marriage of Alexander the Great and Roxane, which depict the arches of the Basilica of Maxentius and landscape elements, are by Sodoma, it is thought that the space in between was originally left undecorated and was occupied by Chigi's bed. The present main scene, depicting The young Alexander taming the horse Bucephalos, is a late 16th century work by an unknown Mannerist artist imitating Sodoma. It was probably commissioned to fill the blank space on the wall following the removal of Chigi's bed some time after his death.

13. The lighting of the Farnesina Alexander frescoes

In fairness, it should be noted that the lamps which illuminate the room are fairly inobtrusive and generally provide an effective solution to the problems of lighting a space in which every surface is entirely covered with precious decoration.

See also one of the fresco panels of the room's ceiling, depicting the abduction of Persephone by Hades painted by an artist from Baldassare Peruzzi's workshop. |

|