|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Friderikos Versakis |

|

back |

Friderikos Versakis |

|

|

| |

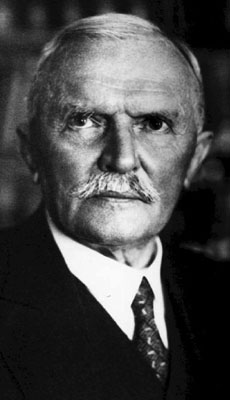

Friderikos Versakis

Friderikos Versakis (or Frederikos Versakes, Φρειδερίκος or Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, 1880-1921) was a Greek archaeologist born in Piraeus, of Italian parents or descent [1]. He was known to his English-speaking colleagues as Frederick, and to Germans as Friedrich.

At the age of 25 he went to Germany to study architecture, but later switched to archaeology. He first studied in Berlin, then Munich and finally in Würzburg, where he submitted his thesis in 1908.

Following his return to Greece, he published studies of ancient monuments south of the Athens Acropolis:

the Theatre of Dionysus (1909) [2];

the Odeion of Herodes Atticus (1910);

the Temple of Olympian Zeus (1910) [3];

the Stoa of Eumenes (1912);

the Asklepieion (1908-1913) [4];

the Choragic Monument of Nikias (1913).

In December 1910 Versakis was appointed Ephor of Antiquities for Corfu, where he helped to establish the archaeological museum ( see below). In 1911, during his excavation of the Archaic "Temple of Artemis" at the Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias, Garitsa, just to the south of Corfu Town centre, he discovered the famous Gorgon pediment. [5] Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, who had purchased the nearby Achilleion palace and was visiting the island at the time, took an active interest in the dig.

Versakis' success in Corfu was somewhat tinged by controversy, particularly concerning his poor relationsip with the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld, who had publicly criticized the quality of his archaeological work in Athens [see note 2]. Both considered themselves to be in charge of the Corfu excavations, causing a competitive friction which led to several disagreements. Following a confrontation between the two men, Versakis was dismissed from his post as ephor in April 1911, perhaps due to the influence of Wilhelm II on the Greek king George I, and replaced by Konstantinos Rhomaios. The excavation of the "Temple of Artemis" was continued under Dörpfeld and financed by the kaiser. [6]

After leaving Corfu, Versakis returned to Athens to continue work on his studies of the south Slope of the Acropolis. He was then sent to the southern Peloponnese to conduct excavations at Lakonia, Messinia and Kythira. [7] Following the description by Pausanias, in 1915 he discovered and excavated the sanctuary of Apollo Korynthos (Κορύνθος Απόλλωνος), near Koroni (Κορώνη) in Messenia. [8] Between 1914 and 1916 he wrote studies of Byzantine churches in northern Epirus, northwestern Greece [9], as well as Byzantine churches in Messenia, the last of which was published posthumously. [see note 7] In 1916 he worked on his final excavation at Lechaion (Λέχαιον), the seaport of ancient Corinth, where he discovered a temple and tombs. [10]

During political upheavals at the end of the First World War, he was dismissed from the Greek Archaeological Service along with many other employees of the Ministry of Education. (According to one account he resigned due to ill health.) He went abroad, only returning to Greece at the end of 1920, shortly before his death.

The few published biographical summaries of his life and work are short, sketchy and rather vague. None reveal what he was like as a person, why he first went to study in Germany at the late age of 25, or why he died so young at 41, apart from mentions of poor health. One recent author wrote of "ill-fated" Versakis without elucidation.

Criticisms of Verskis' work by other archaeologists, especially Wilhelm Dörpfeld, are rarely mentioned. It has been suggested that the antagonism between the two men was essentially a political matter. Many Greeks believed that they should be in charge of archaeological matters in their own country rather than foreigners, a cause of tension which had earlier soured relationships between archaeologists such as Kyriakos Pittakis and Ludwig Ross (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 12). |

Friderikos Versakis during the excavation

of the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu in 1911.

See photo below. |

| |

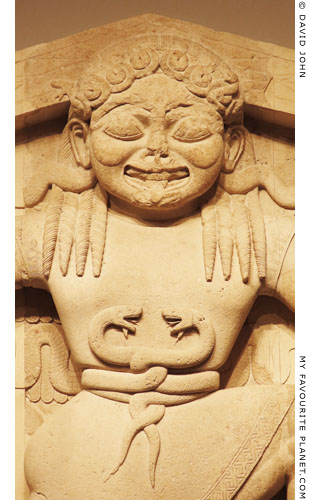

Detail of the Archaic Gorgon Medusa

relief of the Gorgon pediment,

Circa 585 BC, from the "Temple of

Artemis" in Corfu, discovered by

Friderikos Versakis in March 1911.

For further information, see the article

and photos in Medusa part 3. |

| |

| |

|

| |

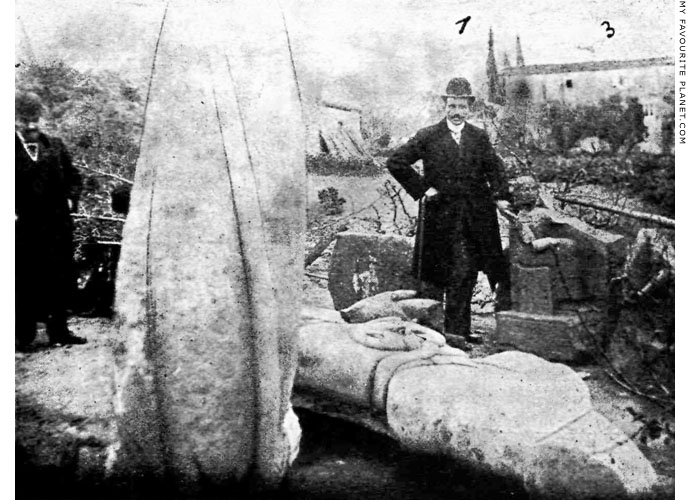

Friderikos Versakis in March 1911, during the excavation of the Archaic "Temple of Artemis" at the

Monastery of Agios Theodoros Stratias, Corfu, where he discovered the famous Gorgon pediment.

Versakis (marked "1" in the photo) poses for the camera among his archaeological finds. Parts

of the pediment lie on the ground around him. In the background is the monastery ("3"). [11] |

| |

The fragment from the apex of the Corfu Gorgon pediment with the head of the

Gorgon Medusa, photographed soon after its discovery by Verskis in 1911. [11] |

| |

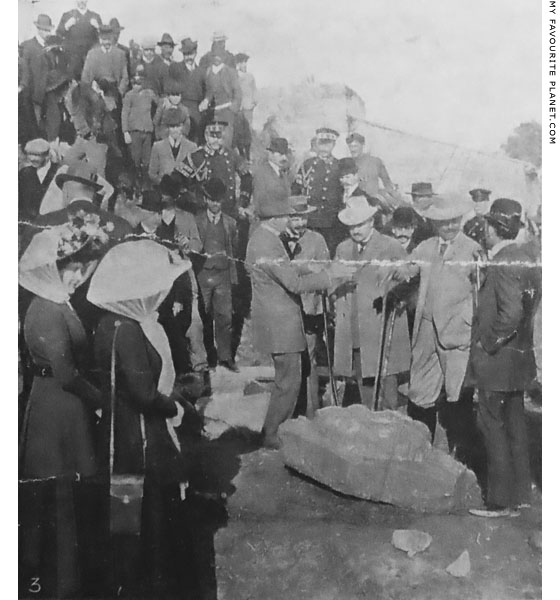

"The Imperial archaeologist on the site whose excavations he will

superintend: the Kaiser inspecting the body of the Gorgon."

A photograph of a public presentation of the finds at the "Temple of Artemis"

in Corfu in April 1911. Versakis may be the figure wearing a bowler hat and

dark suit, his back to the camera, standing next to Kaiser Wilhelm II on the

right of the photo, behind the head of the Gorgon.

|

On 29th April 1911 The Illustrated London News published a full-page spread on the presentation, with six photos showing the kaiser among a number of people and fragments of the Gorgon pediment.

"Fascinated by a Gorgon: the Kaiser as treasure-seeker"

"Greece has paid the Kaiser a graceful compliment by conceding to him all the rights of excavation in connection with the remains at Garitza, for there are few Kings and Governments who are not jealous of the archaeologically inclined stranger in their midst. Naturally, it is understood that all "finds" will remain in the island. Professor Dorpfeld is to have charge of the excavations, with Dr. Versakis, to whom the recent discoveries owe their being, as colleage, and a number of German assistants. It is understood that his Imperial Majesty will supply the funds for extensive work, which will embrace also Govino Harbour, once a Venetian arsenal. The Kaiser is immensely interested in the excavations, and during his stay in Corfu several interesting "finds" have been made, including the head, body and foot of a monster Gorgon. It seems evident that it was the Kaiser's fascination with this Gorgon which prompted Greece to make the above-mentioned concession. So engrossed was he in the digging operations that he stood in the sun all day without food, while the body of the Gorgon was being unearthed. The three Gorgons, it may be recalled, were Medusa, of the snaky locks, Stheno and Euryale."

The Illustrated London News, April 29, 1911, page 613. Photos credited to Record Press.

A copy of the page is displayed in the Museum of Mon Repos, Corfu. |

|

|

| |

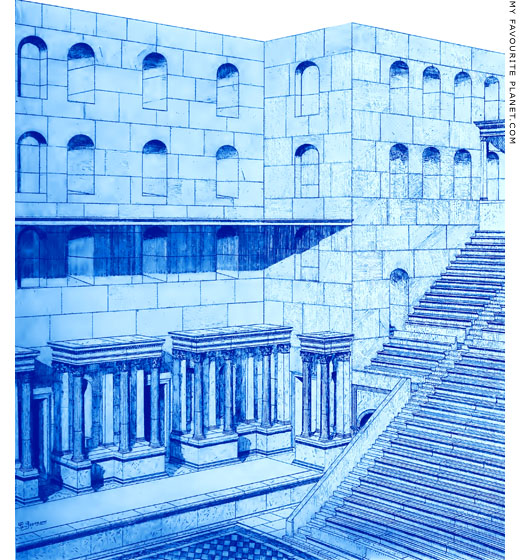

Reconstruction drawing of the interior of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus,

on the south slope of the Athens Acropolis, by Friderikos Versakis, 1912.

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Μνημεία τών νοτίων προπόδων της Ακροπόλεως (Monuments on the

south slope of the Acropolis), Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1912, pages 161-182, Plate 9.

Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological

Society of Athens). At Heidelberg University Library. |

| |

Reconstruction drawing of the Choragic Monument of Nikias by Friderikos Versakis, 1913.

Image source: Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Νικίου Ναός, Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1913, page 75.

Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. At Heidelberg University Library. |

| |

The old archaeological museum of Corfu and the Monument of Menekrates.

|

The old museum was the first purpose-built archaeological museum in Corfu, financed by the Archaeological Society at Athens (Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία), and built 1906-1907. Although the museum had long existed as an institution, established by legislation of the Ionian Assembly in 1833 during the British protectorate (1815-1864), the antiquities of the island had no permanent home. At the beginning of the 20th century they were housed in a room of the Gymnasium of Corfu (referred to as the Gymnasium Museum).

The museum's first curator was Ioannis Marmoras (Ιωάννης Μάρμορας), who made a brief exploratory excavation at the site of the "Temple of Artemis" following its rediscovery in December 1910. Following Versaki's excavation of the Gorgon pediment at the site in 1911, an extension to the museum was planned, but work ceased due to the outbreak of the First World War. [12] It remained in use as a museum until 1930, after which it housed the police station. [13]

The building stands on the site of an ancient necropolis (cemetery) in the Garitsa district, just south of the modern city centre, but north of the ancient city of Korkyra (Κόρκυρα). It was discovered in October 1843 during the demolition of the nearby Venetian fort of San Salvatore by the British army. In the foreground stands the Monument of Menekrates (also known as the Tomb of Menekrates), a circular cenotaph of the 7th - 6th century BC. [14]

Despite conservation and restoration work at the site 2007-2013, the old museum now appears to be going to ruin. The site is surrounded by high metal railings and not usually open to the public, but can be viewed from the adjacent streets. Information boards in Greek and English are within the fenced area and too far from the street to be read.

During the First World War the antiquities were stored in the basement of the Palace of Saint Michael and Saint George. In 1936 they were moved to the "Rolina" building (κτήριο της Ρολίνας, a former casino next to the new museum, today the offices of the 8th Ephorate of Antiquities, Corfu). In 1954 they were returned to the Palace (with the exception of the Gorgon pediment), where part of the collection was exhibited until the opening of the new museum.

The new Archaeological Museum of Corfu, a modern two-storey building just to the northeast of here, was built 1962-1965 and opened in 1967. Following closure for renovation 2012-2017, it was reopened in November 2018. Many antiquities from Palaiopolis, the area of the ancient city of Korkyra, are also exhibited in the villa of the Mon Repos estate. |

|

|

| |

Friderikos Versakis (archaeologist) Street (Οδός (αρχαιολόγου) Φρειδερίκου Βερσάκη),

the main pathway through Mon Repos estate, Corfu.

Visitors can take the path from the estate's entrance, up to the villa, now an excellent museum,

then through the wooded park to the remains of the sanctuaries of Hera and Apollo, and on to the

mysterious Kardaki temple overlooking the Ionian Sea. A pleasant walk in a peaceful landscape,

and a modest tribute to Versakis, who has not been forgotten by the people here. |

| |

Friderikos

Versakis |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Information sources

Very little has been written about the life and work of Versakis, merely a few brief mentions by other archaeologists of some of his contributions to particular archaeological investigations.

A brief obituary for Versakis in English:

Sidney N. Deane, editor, Archaeological News, American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 26, No. 3 (July - September, 1922), pages 339-387 (Versakis obituary on pages 341-342). Archaeological Institute of America, 1922. At jstor.org.

An obituary in French:

Chroniques des fouilles et découvertes archéologiques dans l'Orient hellénique (Novembre 1920 - Novembre 1921). In: Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (BCH), Volume 45, 1921, pages 487-488. At Persée.

An obituary, with brief biographical summary in Greek:

Αλέξανδρος Φιλαδελφενς, Φρειδερίκος Βερσάκης (Alexandros Philadelpheus, Friderikos Versakis), 15th January 1921. Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1919, page 104. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris for 1919, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1921. At Heidelberg University Library.

A brief biographical summary in Greek:

Λεύκωμα της εκατονταετηρίδος της Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 1837-1937 (Centenary scrapbook of the Archaeological Society of Athens 1837-1937), page 10 of the appendix biographies of society members. Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaeological Society of Athens), 1937. At the Digital Library of Modern Greek Studies (Anemi), University of Crete Library.

Another brief biographical summary in Greek (at corfu-museum.gr) appears to be no longer online.

2. Versakis on the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens

Frideriko Versakis, Das Skenengebäude des Dionysos-Theaters (The stage building of the Theatre of Dionysos). In: Jahrbuch des kaiserlich deutschen Archaölogischen Instituts, Band 24, 1909, pages 194-224. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1910. At the Internet Archive.

Versakis's article is followed by a highly critical review by Wilhelm Dörpfeld (pages 224-226).

3. Versakis on the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens

Φρειδερίκος Βερσάκης, Ο περίβολος του Ολυμπιείου επί Αδριανού. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1910.

A short monograph, 16 pages and 1 plate.

Versakis also wrote a monograph on the Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia and the Chalkotheke on the Acropolis.

Friedrich Versakis, Das Brauronion und die Chalkothek im Zeitalter der Antoninen (The Brauronion and the Chalkotheke in the Antonine age). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1910.

4. Versakis on the Sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia, Athens

He wrote a number of articles on the Asklepieion 1908-1913:

Φρειδερίκος Βερσάκης, Αρχιτεκτονική μνημεία του εν Αθήναις Ασκληπιείου (Architectural monuments of the Athenian Asklepieion). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1908, pages 255-284. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Φρ. Βερσάκης, Εργασίαι έν τώ Άσκληπιείω (Work at the Asklepieion). In: Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 1910, pages 279-280. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Praktika, Proceedings of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1911. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Ό του Άθήνησιν Ασκληπιείου περίβολος και τό Έλευσίνιον (On the Athenian Asklepieion and the Eleusinion). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1912, pages 43-59. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Του Αθήνησιν Ασκληπιείου οικήματα. In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1913, pages 52-74. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. (This volume also contains Versakis' article on the Choragic Monument of Nikias, pages 75-85.)

Gordon Allen and L. D. Caskey, who studied the East Stoa of the Asklepieion for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 1905-1906, disagreed with a number of Versakis' conclusions concerning various aspects and details of the sanctuary. Referring to his 1908 study, they commented: "a detailed criticism of this article will not be given here." They added: "Some of its shortcomings have been pointed out by Professor Dörpfeld, Ath. Mitt. XXXVI, 1911, p. 70."

"Most of the buildings seem to the present writers too thoroughly destroyed to admit of a complete restoration. The East Stoa, however, can be restored in almost every important feature on the direct evidence of the remains, - evidence which has in part been overlooked or misunderstood by Mr. Versakes. In view of the importance of the building, both in its bearing on the cult of Asclepius and as an architectural monument, the publication of the accompanying drawings, which differ considerably from those of Versakes, seems justified."

Gordon Allen and L. D. Caskey, The East Stoa in the Asclepieum at Athens. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 15, No. 1 (January - March 1911), pages 32-43. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Allen and Caskey's implied criticisms of Versakis' work appear diplomatically restrained compared to the scathing attack made by Dörpfeld, who began his 1911 report on the Asklepieion with a serious warning to colleagues concerning what he considered to be grave errors in Versakes' 1908 article.

"Vor der schon erschienenen Veröffentlichung von Versakis (Εφ. Αρχ. 1908, 255 und Taf. 9-10) muss ich dagegen die Fachgenossen ernstlich warnen."

He continued with examples of these errors, calling Versakis' analyses and reconstructions of buildings of the sanctuary "more than arbitrary" (mehr als willkürlich) and "bad" (schlecht), and in one case "can impossibly correspond to reality". Some comments end with exclamation marks to indicate his exasperation. He puts these down to Versakis' youth and inexperience, but also accuses him of having little knowledge of construction methods either of modern or ancient buildings. As in his criticism of Versakis' article on the Theatre of Dionysos [see note 2], he was particularly irritated that Versakis had not consulted older, more experienced colleages (such as himself) before publishing the results of his work, but also that Versakis' articles had appeared before planned publications on the same subjects by Dörpfeld himself and other foreign colleagues.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Zu den Bauweken Athens, VII Das Asklepieion. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 36, 1911, pages 70-71. Eleutheroudakis und Barth, Athens, 1911. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

5. The "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu and the Gorgon pediment

Versakis' report on his excavation of the "Temple of Artemis" and his discovery of the Gorgon pediment and other architectural elements was published with photos in 1912:

Φρ. Βερσάκης, Ανασκαφαί Κέρκυρας (Excavations in Corfu). In: Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 1911, pages 164-204. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1912. At Heidelberg University Library.

The volume also contains the accounts of the Archaeological Society of Athens for 1911, including its expenditure on the Corfu excavation 28 March - 16 April 1911 (pages 28-29). This shows that the Society and not the kaiser paid for this first phase of the work there.

Since it was not known for which deity the temple had been built, it was referred to as the "temple at Garitsa", and after the discovery of the Gorgon pediment as the "Gorgo Temple". Following the discovery in 1914 of a fragmentary inscription with a dedication to Artemis, built into a later wall at the site, Wilhelm Dörpfeld claimed it as proof that the temple was dedicated to the goddess. This appeared to be confirmed by the recollection of another dedicatory inscription thought to have been found in the same area in 1813 (see the article in Medusa part 3). |

|

|

6. Versakis, Dörpfeld and the kaiser in Corfu

See an article containing a chronology of the events surrounding the archaeological excavations at the "Temple of Artemis" in Corfu: Γιωργοσ Ζουμποσ, Γιατί χάθηκε ο Βερσάκης; (George Zoumbos, Why was Versakis lost?), in Greek at the Corfu History website.

The article is also available at academia.eu/....

According to the chronology, Versakis first requested funding from the Archaeological Society of Athens for the excavation at the "Temple of Artemis" on 10th February 1911, and again on the 12th. Funding was finally approved on 8th March, and Versakis went ahead with his excavation 13th - 26th March. On the second day he unearthed most of the fragments of the Gorgon pediment, including a lion's head, as well as the head, body and a leg of the Gorgon.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, who arrived at Corfu on 16th March, first visited the archaeological site on 30th March, and thereafter made daily visits. He invited (or ordered) Dörpfeld, at the time Director of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens, to visit Corfu (in the previous seasons he had been excavating at nearby locations, including Ithaka), and he arrived on the island on 3rd April. The kaiser left Corfu on the 17th April.

However, in a memoir the kaiser claimed to have been present at the discovery of the Gorgon.

See: Wolfgang Loehlein, Ausgrabungen auf Korfu, in the brochure for the exhibition Kaiser Wilhelm II. und die Archäologie (Kaiser Wilhelm II and archaeology), Frankfurt am Main Archaeological Museum, 6 June - 6 September 2009. At academia.edu.

Loehlein quotes from the kaiser's memoir of his visits to Corfu, in which he recalled his growing excitement as he spent an entire day watching the slab with the Gorgon head being unearthed:

Kaiser Wilhelm II, Erinnerungen an Korfu. De Gruyter, Berlin / Leipzig, 1924. |

| |

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940),

German architect and archaeologist. |

| |

Wilhelm, who has been accused of being obsessed with the Gorgon, later wrote a book on the subject while in exile in the Netherlands. In this work he went even further and claimed to have unteraken the excavations at the temple in spring 1911 himself:

"Ich wiederhole, daß es mir während meines Aufenthaltes auf Korfu in der Osterzeit des Jahres 1911 gelungen ist, dort einen alten dorischen Steintempel auzugraben, der wohl in der zweiten Hälfte des 8. vorchristkichen Jahrhunderts als Ersatz eines älteren Holztempels errichtet worden war (siehe Titelblatt). Die Einzelheiten meiner archäologischen Arbeit und der damals sich anknüpfenden Forschungen habe ich in meinem Korfu-Buch geschildert."

"I repeat that during my stay on Corfu during Easter 1911, I succeeded in excavating an ancient Doric stone temple, probably built in the 8th century BC to replace an older wooden temple (see frontispiece). I have described the details of my archaeological work and the related investigations in my Corfu book."

Kaiser Wilhelm II, Studien zur Gorgo, chapter 3: "Die Gorgo von Korfu", page 27. De Gruyter, Berlin / Leipzig, 1936. (my translation)

In his memoirs, the former kaiser was even more shameless and claimed he began the excavations. He refers to the discovery of the Gorgon head as "accidental", which is certainly was not, even though the temple site was initially found by chance. He did not mention Versakis or the Greek contribution to the discoveries.

"My sojourn at Corfu likewise afforded me the pleasure of serving archaeology and of busying myself personally with excavation. The accidental discovery of a relief head of a Gorgon near the town of Corfu led me to take charge of the work myself. I called to my aid the experienced excavator and expert in Greek antiques, Professor Dörpfeld, who took over the direction of the excavation work. This savant, who was as enthusiastic as I for the ancient Hellenic world, became in the course of time a faithful friend of mine and an invaluable source of instruction in questions relating to architecture, styles, and so on among the ancient Greeks and Achaeans."

"The excavations begun by me in Corfu under Dörpfeld's direction had valuable archaeological results, since they produced evidence of an extremely remote epoch of the earliest Doric art. The relief of the Gorgon has given rise already to many theories — probable and improbable — combined, unfortunately, with a lot of superfluous acrimonious discussion. From all this, it seems to me, one of the piers for the bridge sought by me between Asia and Europe is assuming shape."

Thomas Russel Ybarra (translator), The Kaiser's Memoirs, by William II, German Emperor, pages 205 and 206. Harper & Brothers, New York and London, 1922. At Project Gutenberg.

See also Dörpfeld's report on his excavations in Corfu in 1914:

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Ausgrabungen auf Korfu im Fruhjahr 1914 (Vorbericht). In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 39, pages 161-176. Eleutheroudakis und Barth, Athens, 1914. At the Internet Archive.

See also an excerpt from Dörpfeld's diary during his work in Corfu in 1912, including his notes, sketches and plans:

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Ausgrabungen in Korfu 1912. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Athen. At Arachne.

Konstantinos Rhomaios (Κωνσταντίνος Ρωμαίος, 1874-1966), who replaced Versakis as ephor of antiquities in Corfu, also took part in the German-led excavations. His report on archaeological work in Corfu in 1914, including the "Temple of Artemis" and the Kardaki Temple, was published in 1915.

Παράρτημα του Αρχαιολογικου Δελτίου 1915 (supplement), pages 77-84. In: Αρχαιολογικον Δελτίον, Τόμος 1, 1915 (Archaiologikon Deltion, Archaeological Bulletin, Volume 1, 1915). Τυπογραφείον Εστία, Athens, 1915. PDF at the University of Thessaly Institutional Repository.

Another version of the discovery and first excavations of the "Temple of Artemis" was written by the German archaeologist Gerhart Rodenwaldt, who had been an assistant to Dörpfeld during his excavation in 1911, and had talked to local people involved with the discovery. Rodenwaldt gave full the credit for the discovery of the Gorgon pediment to the first Greek excavation. He wrote that Versakis, having found fragments of the pediment early in 1911, had discovered all the surviving fragments by the time of his excavation of 7th - 20th April 1911, during which he also unearthed the architectural parts of the temple.

"Die Wiedergewinnung der Bildwerke des Westgiebels ist dieser amtlichen griechischen Ausgrabung zu verdanken."

"The recovery of the figural sculptures of the west pediment is thanks to this official Greek excavation."

The Kaiser first heard of the discovery on 12th April and went to visit the site shortly after. Dörpfeld was at the time in Olympia, and at the call of the Kaiser arrived on Corfu on 18th April, during the last days of Versakis' excavation, in time "to offer his assistance".

Gerhart Rodenwaldt (editor), Korkyra: Archaische Bauwerken und Bildwerker, Band I, Der Artemistempel: Architektur, Dachterrakotten, Inschriften, pages 9-10. Archäologisches Institut des Deutschen Reiches. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 1940. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The French archaeologist and historian Charles Picard (1883-1965, director of l'École française d'Athènes in 1920) certainly thought that Versakis, though inexperienced and "badly informed", had been treated unjustly by the Germans. Picard had a low opinion of the kaiser's claim to be an archaeologist. He was writing after the horrors of World War I, for which the kaiser was given the greater part of the blame, and when the gentlemanly and collegial spirit of competition in archaeological research between nations had sunk to an all-time low.

Charles Picard, Corfou et les "souvenirs" d'un ex-empereur. Impimerie La Haute-Loire, Le Puy, 1926. PDF at tpsalomonreinach.mom.fr. Originally published in: l'Acropole, revue du monde hellénique, Octobre - Décembre 1926.

Thanasis Kalpaxis is one of the writers who has seen hidden political interests at work in archaeological matters, particularly in relation to the excavations of the "Temple of Artemis". See:

Θανάσης Καλπαξής, Αρχαιολογία και Πολιτική ΙΙ. Η ανασκαφή του ναού της Αρτέμιδος, Κέρκυρα 1911 (Thanasis Kalpaxis, Archaeology and Politics II. The excavation of the temple of Artemis, Corfu 1911). Crete University Press, Rethymnon, 1993.

7. Versakis in Lakonia and Messinia

By 1912 he was already writing reports of his investigations at Amyklai (Ἀμύκλαι), 6 km south of Sparta, and Gytheion (Γύθειον), the seaport of ancient Sparta, 25 km north of the city.

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Ό θρόνος του Άμυκλαίου Απόλλωνος (The Throne of Apollo Amyklaios), pages 183-192, and Ή σκηνή του έν Γυθείφ Ρωμαϊκού θεάτρου (The skene of the Roman theatre at Gytheion), pages 193-196. In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1912. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Two further articles were published in the Archaiologike Ephemeris for 1914:

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Το έν τη τέχνη τετράγωνον, pages 25-49, and Βοιωτίας σκύφος εκτυπος έπιγεγραμμένος (An inscribed epigram on a Boeotian relief skyphos), pages 50-57. In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1914. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

His article on Byzantine churches in Messenia appears to have been not only his last report from the southern Peloponnese but also his final contribution to the journal, as it appeared in the same edition as his obituary [see note 1].

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Μεσσηνίας Βυζαντιακοί ναοϊ (Byzantine churches in Messinia). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1919, pages 89-95. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1921. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

8. Versakis and the sanctuary of Apollo Korynthos near Koroni, Messenia

"Some eighty stades beyond Corone is a sanctuary of Apollo on the coast, venerated because it is very ancient according to Messenian tradition, and the god cures illnesses. They call him Apollo Corynthus. His image is of wood, but the statue of Apollo Argeotas, said to have been dedicated by the Argonauts, is of bronze."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 4, chapter 34, section 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

Versakis' report on the excavation was written in Athens in February 1916, and published in 1917:

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Το ἰερόν του Κορύνθου Απολλώνος (The sanctuary of Apollo Korynthos). In: Αρχαιολογικον Δελτίον, Τόμος 2, 1916, pages 65-118 (Archaiologikon Deltion, Volume 2, 1916). Έλληνες Υπουργοί Εκκλησιαστικών και Δημοσίας Εκπαιδεύσεως. Τυπογραφείον Εστία, Athens, 1917. PDF at the University of Thessaly Institutional Repository.

Also reproduced as a single web page: Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Το ἰερόν του Κορύνθου Απολλώνος at aristomenismessinios.blogspot.com.

9. Versakis on Byzantine churches in northern Epirus

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Βυζαντίακοί ναοι της βορείου Ηπείρου (Byzantine churches of northern Epirus). In: Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 1914, pages 243-260. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Praktika, Proceedings of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1915. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Βυζαντίακος ναος έν Δελβίνω (Byzantine church in Delvino). In: Αρχαιολογικον Δελτίον, Τόμος 1, 1915, pages 28-44 (Archaiologikon Deltion, Volume 1, 1915). Τυπογραφείον Εστία, Athens, 1915. PDF at the University of Thessaly Institutional Repository.

Φρ. Βερσάκης, Βυζαντίακοί ναοι της βορείου Ηπείρου (Byzantine churches of northern Epirus). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1916, pages 108-117. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. P. D. Sakellariou, Athens. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

10. Versakis at Lechaion

Versakis' work at Lechaion is mentioned in the obituary in Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, Volume 45, 1921 [see note 1], unfortunately without references:

"il avait récemment quitté le service pour raisons de santé; ses dernières fouilles ont été exécutées à Léchaion, où, en 1916, il avait trouvé un temple et des tombeaux."

So far I have not found a report or article on Lechaion by Versakis himself.

11. Photo of Vesakis in Corfu

This and other photos of Versakis' finds at the "Temple of Artemis" accompanied an article in the Athenian monthly art magazine Πινακοθήκη (Pinakotheke, Art Gallery) in May 1911. The photo of Versakis is not credited, the others are credited to M. Pierris (Μ. Πιέρρης).

Τα ευρήματα της Κέρκυρας (The finds in Corfu). In: Πινακοθήκη, Issue 123, pages 63-65, Εταιρείας των Φιλοτέχνων (Society of Friends of the Arts), Athens, May 1911. At Plia Digital Collection, Library and Information Centre, University of Patras, Greece.

12. The old archaeological museum of Corfu

Perhaps surprisingly, there appear to be few surviving written records of the museum and no photographs of its exhibition.

See: Andromache Gazi, Archaeological museums in Greece (1829-1909), the display of archaeology, Volume 2, pages 277-280. Department of Museum Studies, University of Leicester, 1993.

13. The old archaeological museum of Corfu as a police station

In the 1967 Blue Guide to Greece, the Tomb of Menekrates is described as standing in the garden of the police station.

Stuart Rossiter (editor), Blue Guide Greece, page 456. Ernest Benn Limited, London, 1967.

14. The Monument of Menekrates

The first report, by a British clergyman, on the find of the monument and its identifying inscription was published in December 1843.

Rev. Dr. Hawtrey, On a Greek inscription lately found in Corfu. In: Proceedings of the Philological Society, Volume 1, No. 14, pages 149-151. London, 8 December 1843. PDF at Wiley Online Library.

For details on the monument's inscription, see: Ernest Stewart Roberts, An introduction to Greek epigraphy, Part 1, No. 98, pages 127-128. Cambridge University Press, 1887. At the Internet Archve.

See also a photo of the so-called "Lion of Menekrates", a limestone statue of a crouching lion found near the monument at the same time, which thus became associated with it. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|