1. The foundation of the Asklepieion by Telemachos

Telemachos is mentioned as the founder of the Asklepieion on the "Telemachos Monument", a 2.85 metre tall inscribed T-shaped stele of Pentelic marble, dated to around 400 BC, which is thought to have originally stood in the sanctuary. It consisted of a pillar with inscriptions on both sides, topped by a slightly wider rectangular block with relief panels on all four sides. On top of these was attached a pinax (plaque), much wider than the pillar, with reliefs on both sides.

Although it has been destroyed, its original appearance was reconstructed in the 1960s by the archaeologist Luigi Beschi (1930-2015), based on studies of the 14 fragments now in various museums, some of which are from ancient copies of the the original:

National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Inv. Nos. 2477, 2490, 2491 and one uninventoried;

Epigraphical Museum, Athens, Inv. Nos. EM 8821-8825;

British Museum, Inv. No. 1920,0616.1, and a fragment of a copy, Inv. No. 1971,0125.1;

Museo Civico, Padova, Inv. No. 14;

Museo Maffeiano, Verona, Inv. No. 28615;

Louvre.

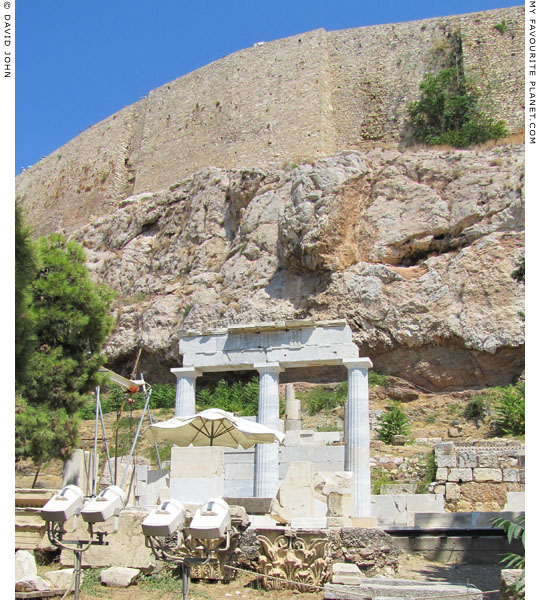

A reconstruction of the monument is usually displayed in the sanctuary, but was removed prior to the recent restoration work at the site.

Not a single complete word remains of the inscription on Face B, but just enough of the long inscription on Face A has survived to read part of a chronicle of the arrival of Asklepios in Athens and the events of the sanctuary's foundation. It was established by a private citizen, Telemachos (Τηλέμαχος) from the deme of Acharnai (Ἀχαρναί), west of Athens, who brought a statue of Asklepios by sea from Epidauros in the Peloponnese, via Zea harbour in the port of Piraeus (where there was also a sanctuary of Asklepios Mounychios and Hygieia).

The inscription lists the stages of progress in the sanctuary's establishment, mentioning the name of the current archon during the year of each phase. Since these names are known from other documents, it has been possible to date the events. The earliest surviving name is that of Astyphilos of Kydantidai (Ἀστυφίλο Κυδαντίδο), who was archon in 420/419 BC, and the last is Kallias of Skambonidai (Καλλίας Σκαμβωνίδης), archon in 412/411 BC. It is not known who dedicated the monument.

Several scholars have studied the inscription fragments, but the key editions are those by Luigi Beschi and Kevin Clinton. For an English translation of the inscription, with references and links to the versions of the text in Greek, see:

SEG 47.232 at Attic Inscriptions Online.

At the top of the monument stood a rectangular pinax with reliefs on both sides (an amphiglyphon), which appears to have depicted Asklepios, Hygieia and Telemachos on one side, and on the other the gateway of the Asklepieion as well the prow of a ship and the crests of two waves, perhaps representing the sea journey of Asklepios from Epidauros. Relief fragments also show participants in rituals relating to the cult, the architecture of the sanctuary and animals (a dog, a horse, a stork).

Two main reasons have been proposed for the introduction of the Asklepios cult in Athens at this particular period. The first is that it was a consequence of the plague that devastated Athens in three outbreaks between 430 and 426 BC, killing many citizens, including Pericles. A plague was also given as the traditional reason for the establishment of the first Asklepieion in Rome around 293-291 BC, when a Roman delegation brought a sacred snake from Epidauros to the city.

According to the second theory the Athenians' motives for introducing Asklepios from Epidauros were political, connected with their imperial aspirations, and part of a strategy to win the good will of the Epidaurians and other Peloponnesian states (Argos, Achaea and Elis) during the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). In 421 BC, during the tenth year of the war and around a year before the foundation of the Athenian Asklepieion, Athens, Sparta and their respective allies signed the Peace of Nikias, and this temporary peace allowed the Athenians to attempt to establish closer ties with Epidauros.

Nothing is known of Telemachos or his motives for bringing Asklepios to Athens. It appears that he established the Asklepieion at his own expense, suggesting that he was a wealthy indivdual fulfilling a personal ambition on his own initiative. Was he a priest of Asklepios, a doctor or a grateful former patient at Epidauros? Or was he perhaps acting unofficially in the political and military interests of the Athenian state?

The protection of the god and the medical services provided by the sanctuary would certainly have been seen as beneficial to Athenian citizens traumatized by war and plague, and the consequent ties with Epidauros perceived as a strategic achievement, so that spiritual, personal, social and political considerations coincided.

The account of a statue (or copy of a statue) of a god being brought to Athens as part of the introduction of a cult to the city is similar to the tradition of a cult statue of Dionysus being brought from Eleutherai (see Theatre of Dionysos). A number of other cults were introduced to Athens in the 5th century BC, including those of Adonis, Adrasteia, Artemis Aristoboule, Bendis, Meter, Pan (see gallery page 4), Pheme and Sabazius.

Beschi first published the results of his study of the Telemachos Monument in 1967:

Luigi Beschi, Il monomento di Telemachos, fondatore dell' Asklepieion atenoese, in Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente (ASAtene) 45-46 (Nos. 29/30, 1967/1968), pages 381-436.

For wide-ranging discussion of the foundation of the Athens Asklepieion, including its religious, social and political contexts, and extensive bibliographies, see:

Bronwen Lara Wickkiser, The appeal of Asklepios and the politics of healing in the Greco-Roman world. PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2003.

Roy van Wijk, Asklepios' arrival at Athens: A perspective on the Athenian introduction of the Epidaurian Asklepios cult (420/419 B.C.E.) in the context of the Peace of Nikias and the interstate relations in Classical Greece. Masters thesis, Utrecht University, 2013.

A recent study has attempted to answer some of the questions posed by generations of archaeologists and historians concerning the original Asklepieion founded by Telemachos, including its exact location and size, and what subsequently happened to the first temple and altar. See:

Michaelis Lefantzis and Jesper Tae Jensen, The Athenian Asklepieion on the South Slope of the Akropolis: early development, ca. 420-360 B.C.. In: Jesper Tae Jensen, George Hinge, Peter Schultz, Bronwen Wickkiser (editors), Aspects of Ancient Greek cult: context - ritual - iconography, pages 91-124. Aarhus University Press, Netherlands, 2009. At academia.edu.

2. The Epidauria festival

See, for example: Jennifer Larson, Ancient Greek cults: a guide, pages 74-75. Routledge, New York and London, 2007.

3. The Zoodochos Pigi

See: Evy Johanne Håland, The Life-giving Spring: water in Greek Religion, Ancient and modern, a comparison. In: Proteus, Volume 26, Spring 2009, Number 1, pages 45-54. Available as a PDF at the website of Shippensburg University, Pennsylvania.

4. The first excavations of the Asklepieion

A brief list of the first reports of the excavations is given in:

Gordon Allen and L. D. Caskey, The East Stoa in the Asclepieum at Athens. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 15, No. 1 (January - March 1911), pages 32-43. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Allen and Caskey, who studied the East Stoa of the Asklepieion for the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 1905-1906, disagreed with a number of conclusions reached by the Greek archaologist Friderikos Versakis concerning the sanctuary. See the Friderikos Versakis page in the MFP People section. |

|

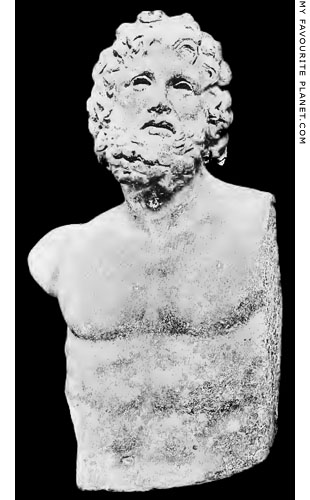

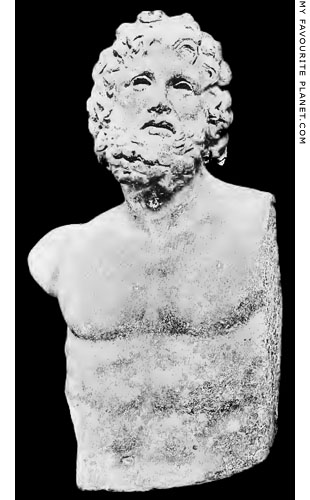

Part of a marble statue of Asklepios

(head and upper torso) found in a

sanctuary, perhaps an asklepieion,

on the Mounychia Hill, Piraeus.

2nd century BC. Pentelic marble.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 258.

Source: Maxime Collignon, Geschichte der Griechischen Plastik, Band 2, Fig. 126, page

266. German translation by Fritz Baumgarten.

Karl J. Trübner, Strassbourg, 1898. |