|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

The inside of the north tower (pylon) of the Beulé Gate. In the background, the Philapappou Monument. |

| The Beulé Gate |

| |

The Beulé Gate is the late Roman defensive entrance to the Acropolis which leads to the stairway up to the monumental Classical Greek gateway of the Propylaia. Today it is used as the visitors' exit (the small gate, left in the photo).

It is unique among Athens' ancient monuments in being named after an archaeologist [1], Charles Ernest Beulé (1826-1874), who excavated it and the stairs up to the Propylaia in 1852. [2]

Early modern visitors to Athens, including Jacob Spon and George Wheler in the late 17th century [3] and William Martin Leake [4] in the early 19th century, had reported an inscription commemorating a Roman named Flavius Septimus Marcellinus for presenting the gate to the city, suggesting that he financed the gate.

In 1834-1835 architect Gustav Eduard Schaubert and the archaeologist Ludwig Ross cleared away much of the debris covering the grand Roman marble stairway up to the Propylaia (built around 52 AD), work which was continued by Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis from 1836 [5]. But it was Beulé who realized the significance of the Roman gateway and freed it from the Turkish fortifications and centuries of accumulated soil and rubble.

The Beulé Gate was built in 280 AD, following a devastating attack by the east Germanic Heruli tribe in 267 AD (usually referred to as the Herulian invasion), at a time of continuing threat from wandering Gothic tribes. [6] It consists of two massive, unequally sized towers (or pylons), between which was the gateway, and was aligned with the axis of the Propylaia, which itself had been built in alignment with the Parthenon.

It was built with Piraeus limestone blocks [7] and materials taken from other structures, including the Hellenistic Choragic Monument of Nikias (see below) from around 320/319 BC, the foundations of which can still be seen between the Theatre of Dionysos and the Stoa of Eumenes, on the south slope of the Acropolis. The gateway contains the monument's achitrave which bears the inscription:

"Nikias, son of Nikodemos of Xypete, dedicated this monument after a victory as choregos with boys of the tribe of Kekropis; Pantaleon of Sikyon played the flute; the 'Elpenor' of Timotheos was the song; Neaichmos was archon."

While building materials on the Acropolis were continually being recycled, such monuments were generally greatly respected by the Romans, perhaps more than by many Athenians. This suggests that either the Nikias monument had already been destroyed or badly damaged, or that the Athenians were scared and desperate enough to use whatever they considered could be sacrificed for the defence of the citadel. It is generally agreed that the quality of the workmanship is quite poor, which also points to hasty construction.

Just before the siege of the Acropolis by the army of the Venetian Francesco Morosini in 1687, the Turkish defenders dismantled the Temple of Athena Nike and used some of its fabric to reinforce the Beulé Gate and convert it into a cannon emplacement

See the early 19th century illustration of the fortified Propylaia on gallery page 10). |

See plans of the entrance to

the Acropolis, showing the

Beulé Gate, the Temple of

Athena Nike, the Pedestal of

Agrippa, the top of the stairway

to the Klepsydra and the

Propylaia, on gallery page 10. |

| |

Charles Ernest Beulé

Read a profile of Beulé at

My Favourite Planet People |

| |

The Choragic Monument of Nikias

See below |

| |

| |

Visitors to the Acropolis leaving by the Beulé Gate. |

| |

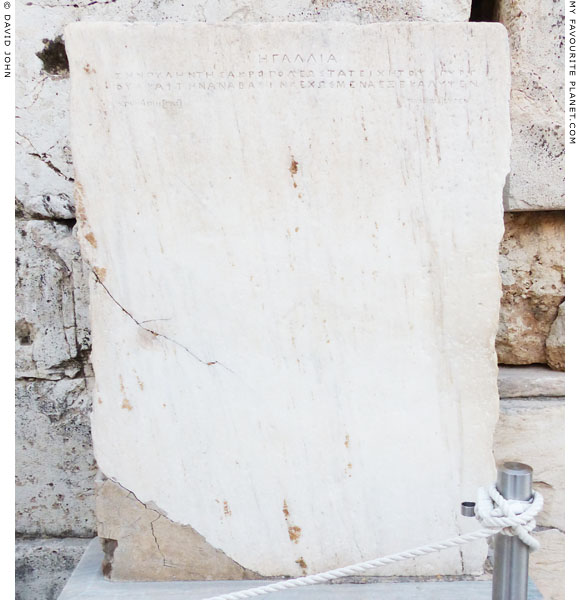

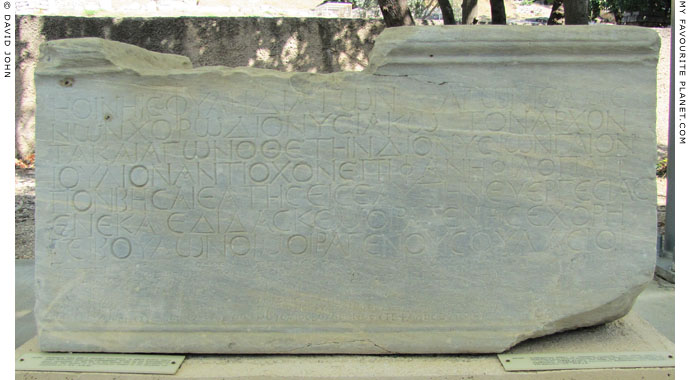

A marble stele to the left of the exit through the Beulé Gate, with an

inscription in Ancient Greek, set up by Beulé to commemorate his work on

the Acropolis with archaeologists of l’École française d’archéologie d’Athènes.

|

Η ΓΑΛΛΙΑ

ΤΗΝ ΠΥΛΗΝ ΤΗΣ ΑΚΡΟΠΟΛΕΩΣ ΤΑ ΤΕΙΧΗ ΤΟΥΣ ΠΥΡΓ

ΟΥΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΗΝ ΑΝΑΒΑΣΙΝ Κ ΕΧΩΣΜΕΝΑ ΕΞΕΚΑΛΥΨΕΝ

ΧΠΗΗΗΠΙΙΙ (1853)

ΒΕΥΛΕ (BEULE) ΕΥΡΕΝ

France,

the gate of the Acropolis, the walls of the tower

and the ascending way, (until then) buried, unearthed.

1853

Beulé

According to Beulé (L'Acropole d'Athènes, 1862 edition, page 61; see note 2), the Greek inscription was followed by a French version. This appears to have been erased; it is certainly no longer legible.

La France

a découvert la porte de l'Acropole,

les murs, les tours, et l'escalier.

MDCCCLIII.

Beulé. |

|

|

| |

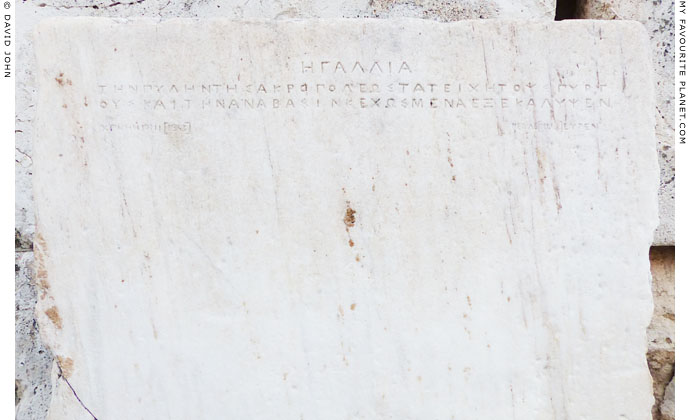

Detail of the inscription on the stele above. |

| |

Two of the three stone stautes of crouching lions

to the right of the exit through the Beulé Gate.

|

The area just inside the gate, to the right of the exitway, are the three lions, a number of stones with inscriptions and a column capital with a Christian cross. The area is roped off and there is no information provided about why these objects are lying here. Several other equally mysterious artefacts can be seen around the Acropolis and on the way down to the Agora, including inscribed steles and statue bases.

So far we have found no further information about these lions. Apparently they are not deemed important enough to feature in printed or electronic guides to the Acropolis, or to have been protected in a museum. A few non-expert internet sources state that they were "sculpted during the Venetian rule of Athens". But if so, why and perhaps more importantly when?

The Venetian general Francesco Morosini (1619-1694) ruled Athens for only six moths, during the Morean War, the Christian attack on the Ottoman occupied Greek mainland which caused much destruction and disruption but ended without much territorial or strategic advantage. Morosini's army besieged the Acropolis for six days, 23-29 September 1687, and the artillery bombardment caused great destruction to the ancient buildings, particularly the Parthenon (see gallery page 16).

Following the surrender of the Turkish garrison on the Acropolis, the Venetians soon decided to abandon Athens in order to concentrate inadequate forces on protecting territories they had captured in the Peloponnese and for what proved to be an unsuccessful attack on Negroponte (Chalcis, Euboea). By early April 1688 the Venetians had left the city, taking much of its population with them, and the Turks retook it soon after. Before leaving Morosini plundered Athens and Piraeus, taking booty which included the famous Piraeus Lion (now at the Venetian Arsenal). He also attempted to take the relief sculptures from the west pediment of the Parthenon, but they fell to the goround and were smashed in the process.

The Venetian occupation of Athens occurred at a time of great chaos, and one wonders when anybody would have had the time or resources to sculpt such lions, and for what purpose they would have been made.

If you have any further information about these lions, please get in contact. |

|

|

| |

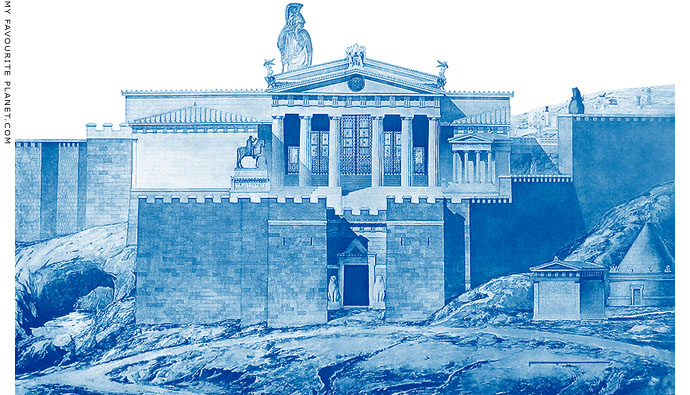

Idealized reconstruction of the west side of the Acropolis in the late Roman period,

showing the Roman fortifications of the Beulé Gate standing in front of the Classical Propylaia.

Like most 19th and early 20th century reconstructions, the artist has attempted to

dignify the Beulé Gate with symmetry by rendering both of its towers as equal in size.

Engraving of a drawing by the French architect Louis Boitte (1830-1906),

published in Le Moniteur des architectes, Volume VII, 1873.

See more illustrations of the Acropolis featuring the Beulé Gate

on gallery page 2 and gallery page 10. |

| |

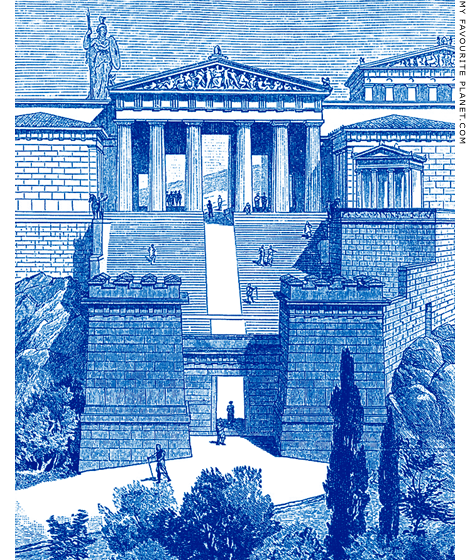

Late 19th century reconstruction drawing of the

entrance to the Acropolis during the late Roman period.

Illustration from Jakob von Falke, Hellas und Rom, eine Culturgeschichte des classischen

Alterthums. W. Spemann, Stuttgart, 1878. Published in English as Greece and Rome,

their life and art. Translated by William Hand Browne. Henry Holt and Co., New York, 1886. |

| |

The outside of entranceway to the Acropolis through the centre of the Beulé Gate,

between the towers. Parts of the architrave of the Choragic Monument of Nikias

(see below), including the triglyphs and metopes, form the top of the central wall.

The gate is in alignment with the Propylaia which can be seen through the entrance. |

| |

| Beulé Gate |

The Choragic Monument of Nikias |

|

|

|

Reconstruction of the Hellenistic Choragic Monument of Nikias, built 320/319 BC.

Image source: Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, page 49.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Library. |

| |

Choragic Monument of Nikias was built around 320/319 BC in the form of a prostyle (with a front porch supported by columns) hexastyle (front row of six columns) Doric temple with the entrance at the west end. The arrangement of the columns is in imitation of the east porch of the Classical Propylaia of the Acropolis.

Choragic monuments were built to display the bronze tripods awarded as prizes to the winning chorus and musicians in contests held at the Theatre of Dionysos. The often lavish monuments were paid for by the winning choregos (χορηγός), a wealthy citizen appointed to sponsor and supervise the training of the chorus.

At some point the monument had been destroyed, perhaps during the Herulian invasion in 267 AD, and its parts reused in other structures. Archaeologists discovered many of its parts scattered around the Acropolis and built into the Beulé Gate, including an inscription identifying the choregos who dedicated it, discovered by Charles Ernest Beulé in 1852.

"Nikias, son of Nikodemos, of the deme Xypete, dedicated this altar being victorious with Kekropis in the boys' contest. Pantaleon of Sikyon played the aulos. The song Elpenor of Timotheos. Neaichmos was Archon."

Inscription IG II² 3055 (also IG II 1246).

The search then began for the original location of the monument. After several false starts, the German archaeologist and architect Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940), who was the first to analyze the monument, identified its foundations in 1885, just south of the east end of the Stoa of Eumenes.

However, the Greek archaeologist Friderikos Versakis (1880-1921) believed that it stood near the Theatre of Dionysos. The American architectural historian William Bell Dinsmoor (1886-1973) agreed with Dörpfeld's conclusion, and having carefully examined all available parts, he excavated the site in 1910. He discovered parts of mouldings which matched those of blocks on the Beulé Gate.

In his monograph on the subject Dinsmoor presented a detailed description of the parts of the Choragic Monument of Nikias used to build the Beulé Gate as well as the foundations and other remains found to the west of the Theatre of Dionysos.

He also discussed the monument's relation to the Stoa of Eumenes and the findings and theories of other archaeologists such as Beulé, Dörpfeld, Versakis and Furtwängler. The various theories included the idea that the Monument of Nikias may be older than the 320/319 BC inscription, and have been built by the welthy 5th century BC Athenian politician and general Nikias, son of Nikeratos (470-413 BC), about whom Plutarch wrote (Life of Nicias, III, 3). The question of when and why/how the monument was destroyed remains a mystery.

Of Versakis' contribution to the investigations of the Nikias Monument, Dinsmoor wrote:

"The most important addition of material made by Versakes is a Doric capital now east of the Parthenon, together with the lower drum of a shaft now in the theatre. The two agree with each other in technique and scale, and are of the right scale for the Nicias monument, though it is strange that one of the capitals should have been transported to the top of the Acropolis. A capital exactly like that identified by Versakes is shown by Stuart and Revett (Vol. IV, ch. V, pl. VIII, 6 *), who saw it in a ruined church in the Turkish cemetery below the west end of the Acropolis, a region full of remains of the monument of Nicias."

Dinsmoor, The Choragic Monument of Nicias, pages 470-471.

* See the drawing of the Doric capital made by Stuart and Revett and photos below.

See an illustration showing the Turkish cemetery west of the Acropolis on gallery page 32.

See:

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Das choragische Monument des Nikias. In: Mittheilungen des deutschen Archäologischen Institutes in Athen, Band 10 (1885), pages 219-230 and Plate VII. Karl Wilberg, Athen, 1885. At the Internet Archive.

William Bell Dinsmoor (American architectural historian, 1886-1973), The Choragic Monument of Nicias. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 14, No. 4 (October - December 1910), pages 459-484. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Also a response to Dinsmoor's monograph: Bernadotte Perrin, The Choragic Monument of Nicias. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 15, No. 2 (April - June 1911), pages 168-169. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

Friderikos Versakis (1880-1921) also published a detailed architectural study of the monument in Greek, in:

Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Νικίου Ναός (Nikiou Naos). In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1913, pages 75-85. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). P. D. Sakellariou, Athens, 1913. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

See also references to Versakis' article examining the southwest slope beneath the Acropolis, including the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, the Stoa of Eumenes and the Asklepieion.

The identification of the Monument of Nikias rested on mentions of Nikias and choragic monuments in Athens by Plato (Gorgias, 472 A) and, more particularly, Plutarch (Life of Nicias, III, 3), about which there has been much debate among historians and archaeologists.

Plutarch, The Life of Nicias. From The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, Loeb Classical Library edition, Volume III, 1916). At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

See also The article about the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos on Acropolis gallery page 35.

We will be discussing the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates (photo, above right) in a future section of the My Favourite Planet guide to Athens. |

Choragic Monument of Lysikrates,

335/334 BC, on Odos Tripodon

(Street of the Tripods), in the Plaka. |

| |

A tall but slightly more humble

base for a choragic tripod, in

the Athens Agora archaeological

site. End of the 1st century AD. |

| |

Wilhelm Dörpfeld |

| |

Friderikos Versakis in 1911,

during the excavation of the

Temple of Artemis at the Agios

Theodoros Monastery, Corfu,

where he discovered the

famous Gorgon pediment. |

| |

| |

Reconstruction drawing of the Choragic Monument of Nikias by Friderikos Versakis.

|

Although Versakis' reconstruction is similar to Dinsmoor's, it varies in several details: Versakis has omitted the inscription on the architrave (see top of page); his Doric columns appear to be monoliths, whereas Dinsmoor shows them in three segments; Dinsmoor shows an akroterion base at the apex of the roof. Dinsmoor estimated that this base would have only been 88 cm wide and thus too small to hold a choragic tripod. He came to the conclusion that the tripod would have been kept inside the building.

Image source: Φριδερίκος Βερσάκης, Νικίου Ναός, Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1913, page 75.

Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

The foundations of the Choragic Monument of Nikias. Several architectural

members have been laid out on the site (see photos below).

Behind the trees is the retaining wall of the Stoa of Eumenes

(see gallery page 33), and in the background above, the

south wall of the Acropolis and the Parthenon can be seen. |

| |

The Doric capital found by Stuart and Revett in a ruined church near the Turkish

cemetery, west of the Acropolis, thought to belong to the Monument of Nikias.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities

of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume IV, Chapter IV,

Plate VIII, fig. 6. J. Taylor, London, 1816. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

A similar (identical?) Doric capital on the site of the Monument of Nikias. |

| |

Architectural members on the site of the Monument of Nikias. Is the Doric

capital the one first discovered by Stuart and Revett? And is the part of a

column the one found by Versakes (see quote from Dinsmoor above)? |

| |

A marble dedicatory base with a choregic inscription honouring archon Gaius Julius Antiochus

Epiphanes Philopappos, and mentioning the factors of a performance staged at the Dionysia.

75/76 - 87/88 AD. Philopappos is known from the Philopappou Monument, his tomb on the

Hill of the Muses, southwest of the Acropolis.

The archaeological site of the Theatre of Dionysus, Athens. Inv. No. NK 280. |

| |

| Beulé Gate |

Notes, references, links |

|

|

1. The foundations of the the pre-Parthenon Athena temple (known as the Hekatompedon temple or "Parthenon I", see gallery page 13), built around 575-550 BC, are sometimes referred to as "the Dörpfeld foundation" after the German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940) who discovered them during excavations on the Acropolis 1885-1890 with Panagiotis Kavvadias and Georg Kawerau.

2. Beulé on his excavations on the Acropolis

See:

Charles Ernest Beulé, L'Acropole d'Athènes, Tome Premier (volume 1 of 2). Firmin Didot, Frères, Paris, 1853. At the Internet Archive.

Also at the University of Heidelberg Digital Library: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/beule1853

Charles Ernest Beulé, L'Acropole d'Athènes, Tome Second (volume 2 of 2). Firmin Didot, Frères, Paris, 1854. At the Internet Archive.

Also at the University of Heidelberg Digital Library: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/beule1854

Republished in a single volume in 1862:

Charles Ernest Beulé, L'Acropole d'Athènes. Firmin Didot frères, fils et cie, Paris, 1862. At the Internet Archive.

3. Spon and Wheler

The French doctor and antiquarian Jacob Spon (1647-1685) and the English botanist (and later clergyman) George Wheler (1650-1723) travelled together through Italy to Greece, Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Levant in 1675-1676. Two of the first modern scholars who travelled to Greece specifically to investigate ancient sites, they recorded the antiquities they saw, transcribed inscriptions, and Wheler particularly collected plants, antiques and ancient coins. On returning to their respective homelands, each published accounts of their travels, which remained important guides for travellers and historians over the next two hundred years.

See: Jacob Spon, Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grece, et du Levant, faités années 1675 et 1676, Tome II. Henry and Theodore Boom, Amsterdam, 1679. At the Internet Archive.

In this edition, the marble inscription dedicated to Flavius Septimus Marcellinus is mentioned in Livre V, Description d'Athenes, de Salamine, et du Golfe d'Egina, pages 104-105. A transcription of the Greek inscription and a translation into French appears at the end of the volume, in an appendix titled Inscriptions Antiques, page 335.

ΦΛ. ΣΕΠΤΙΜΙΟΣ ΜΑΡΚΕΛΛΙΝΟΣ ΦΛΑΜ. ΚΑΙ ΑΠΟ ΑΓΩΝΟΘΕ

ΤΩΝ ΕΚ ΤΩΝ ΙΔΙΩΝ ΤΟΥΣ ΠΥΛΩΝΑΣ ΤΗ ΠΟΛΕΙ

"Flavius Septimius Marcellinus Prêtre des Dieux, et l'un de ceux qui président auy jeux publics, a fait bâtir à ses dépens les portes de la ville."

See also: George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book V, page 358, with a drawing of the inscription. William Cademan, Robert Kettlewell, and Awnsham Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks.

4. Colonel William Martin Leake FRS (1777-1860), English antiquarian and topographer.

The topography of Athens, with some remarks on its antiquities, Section IV, page 102, and Section VIII, page 188. John Murray, London, 1821. At the Internet Archive.

5. Ludwig Ross, Archäologische Aufsätze, Zweite Sammlung. II. 6. Beulé, L'Acropole d'Athènes, pages 268-279. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1861. Preview at googlebooks.

Read more about Ross, Schaubert and Pittakis on gallery page 12, notes 17, 19 and 21.

6. The Herulian invasion, 267 AD

In 267 AD Attica was invaded by the east Germanic Heruli tribe that arrived from the Black Sea coast via Ionia and the Aegean islands. They sacked Athens, destroying most of the ancient buildings and monuments in the lower city. Eventually they were repulsed by a force of two thousand Athenians commanded by the archon Erennios Dexippos (see gallery page 4), who wrote an account of the invasion. Later, stones from the ruins were used in the construction of new defences, including the Beulé Gate and the Post-Herulian Wall around the lower city north of the Acropolis (about 282 AD), parts of which can still be seen in the Ancient Agora.

Other devastating attacks that have left their mark on Athens include: the invasion by Persian King Xerxes I in 480-479 BC, the Roman general Sulla in 86 BC, the Visigoths under Alaric in 395-396 AD, the Vandals in the 470s AD, and the Slavs in 582-583 AD.

7. Piraeus limestone

See an article on Piraeus limestone, as well as other types of local stone used in the building of the Acropolis:

P. Theoulakis and M. Bardanis, The stone of Piraeus at the monuments of the Acropolis Athens, in Vasco Fassina (editor), Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Deterioration and Conservation of Stone, Venice, June 19-24, 2000, Volume 1, page 255. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, 2000. At Google books. |

|

|

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|