|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

The bastion of Athena Nike projecting from the southwest edge of the Acropolis.

To the left and behind the temple are parts of the Propylaia.

To the right is one of the temporary buildings used by the restoration workers. |

|

Temple of Athena Nike part 2

The temple disappears

and reappears - 3 times |

| |

Pausanias is responsible for the fact that many modern visitors to the Acropolis, from the 17th century onwards, took this to be "the temple of Nike Apteros" (Wingless Victory). Since it was too small to be converted into a church, mosque or house, as other ancient buildings had been, it was left almost unmolested for over 2000 years, and was still intact when Jacob Spon and George Wheler came to Athens in 1676. In his short description of the temple, Spon noted that the Turks were using it as a gunpowder magazine. [1]

A decade later, just before the siege of the Acropolis by the army of the Venetian Francesco Morosini in September 1687, the Turkish defenders dismantled the Temple of Athena Nike and used its fabric to reinforce the bastion, fortifications in front of the Propylaia and on the Beulé Gate, and convert them into cannon emplacements (see an early 19th century illustration of the fortified Propylaia on gallery page 10).

Northern European travellers on their "Grand Tour" who arrived in Athens in the 18th and early 19th centuries, having read their Pausanias, Spon and Wheler, were perplexed by the disappearance of the temple. Both James Stuart (1751) and Doctor Richard Chandler (1765) [2], thinking that the previous authors had made an error, assumed it must have been on the left rather than right on the assent to the Acropolis, and therefore mistook the north wing of the Propylaia (the Pinakotheke) for the temple. In 1836 Edward Giffard commented on the confusion over the missing temple:

"... it had subsequently totally vanished from the eyes of modern travellers. Dr. Clarke does not even allude to it, and its disappearance has puzzled the critics. Some suspected the text of Pausanias, and the testimony of Wheeler - others imagined the site to have been on the left instead of the right; in short, it was gone - and the learned began to wonder, that of all the temples in Athens, it should be that of Victory without wings that had unaccountably flown away; so complete was its disappearance." [3]

In 1751 Stuart noted four slabs of the temple's frieze built into a nearby wall. They were removed by Lord Elgin's agents in 1804 and shipped to England along with the other "Elgin Marbles", and are now in the British Museum. [4]

The defensive walls into which parts of the temple were built had been badly battered by the Venetian bombardment, and other pieces lay around amongst centuries of rubble and could not be identified by visiting antiquarians. William Leake wrote that as late as 1837 "Mr. Wilkins still questioned whether the site of the temple of Victory had yet been discovered." [5]

However, while Mr Wilkins was still pondering, the temple was already being reconstructed. The German archaeologist Ludwig Ross had been appointed Ephor of all antiquities in the newly independent Greece and took on the enormous task of restoring monuments on the Acropolis, with architects Eduard Schaubert and Hans Christian Hansen. [6] The Temple of Athena Nike was to be the first monument on the Acropolis to be restored, and by July 1835 all discovered parts had been collected in front of Propylaia.

Such a restoration of an ancient building was unknown territory: up until then most so-called archaeologists had been more interested in purloining pieces of monuments. Also Ross and his team did not know exactly what the temple had originally looked like. They used Stuart and Revett's drawings and measurements of the similar Ilissos Temple (see previous page) as vital references. [7] From November until May 1836 rebuilding continued, but was then halted, due partly to other archaeological priorities and partly to politics.

In 1836 the Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis managed to oust Ross as Ephor of antiquities [8], and completed the rebuilding of the temple in 1843-44. He also added three of the four copies of the "Elgin Marbles" parts of the frieze, donated in 1845 by the British Museum; the fourth copy was broken during the assembly work. |

|

|

| |

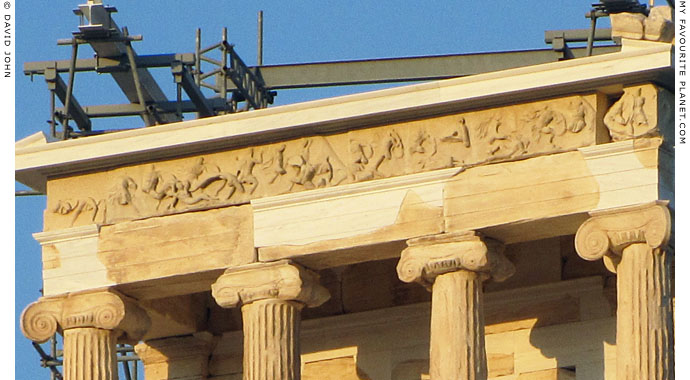

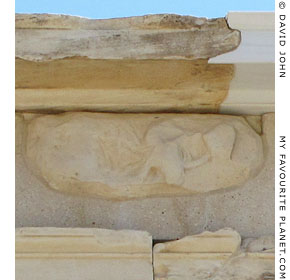

Frieze on the west side of the Temple of Athena Nike

|

This part of the frieze, a copy of the remains of the original now in the Acropolis Museum, is thought to depict a battle between Greeks. The frieze, consisting of 14 marble blocks 45 cm high, ran around the four sides of the cella: the east side (front) depicted a gathering of Olympian gods, the north and south sides Greeks fighting Persians (perhaps the Battle of Marathon), and the west (back) Greeks fighting Greeks. Four of the original blocks were taken to England by Lord Elgin and are now in the British Museum. [4]

Only fragments of other sculptural decoration of the roof and pediment have survived. |

|

|

| |

The figures are badly worn and difficult to make out, especially when standing

directly under the frieze, but it is a wonder that they have survived at all. |

| |

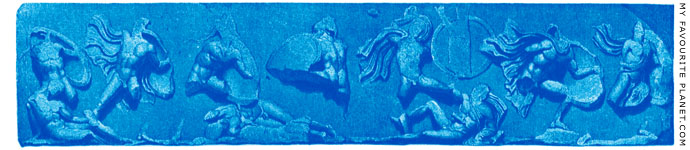

Part of the west frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike (British Museum): battle between Greeks |

| |

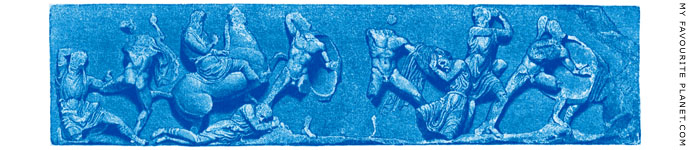

Part of the north frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike: battle between Greeks and Persians |

| |

Part of the south frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike:

battle between Greeks and Persians (the Battle of Marathon?)

Source: Dr Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, page 18.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Library. |

| |

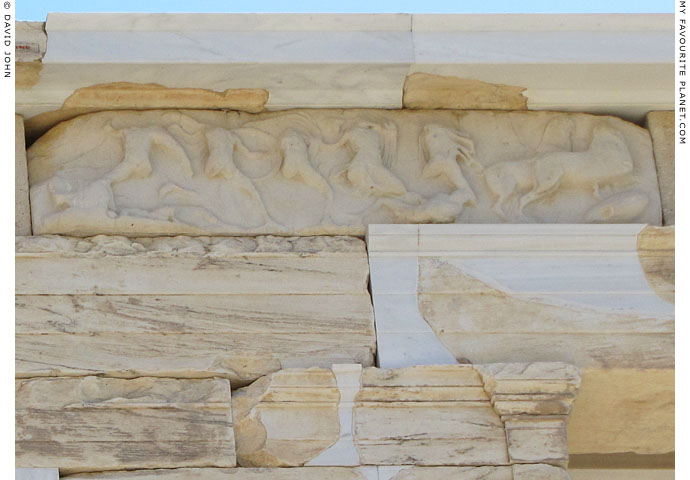

Copy of part of the north frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike, above the rear (west) porch. |

| |

| A copy of another fragment of of the north frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike, to the left (east) of the one above.

See photos of the north side of the temple below. |

|

|

|

| |

Copy of part of the south frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike. |

| |

"The newly-discovered temple of Victory, Athens."

On the left, four of the temple's Ionic columns and two Greek gentlemen in national costume

have been set up to adorn the scene. To the right are the Pedestal of Agrippa and the

western edge of the Propylaia. Below, in the distance, is the Temple of Hephaestos (then

still thought to be the temple of Theseus) at the western end of the Ancient Agora.

Engraving after a drawing by F. W. Newton, made 1836, during the temple's first

reconstruction. Published in Edward Giffard, A short visit to the Ionian Islands,

Athens, and the Morea. John Murray, London, 1837. See note 3 below. |

| |

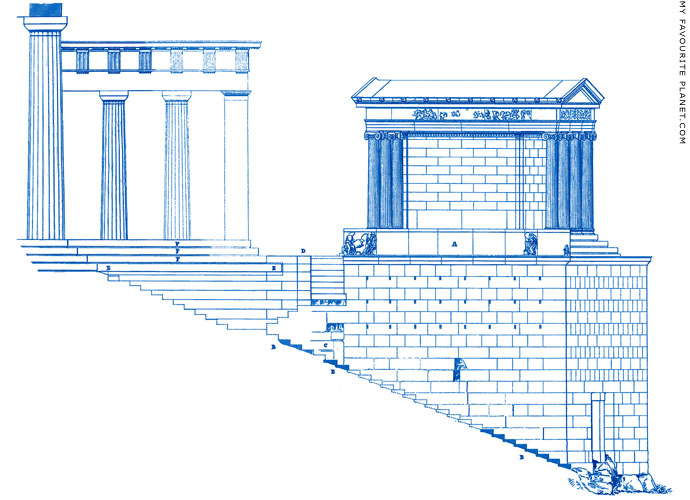

Elevation of the south wing of the Propylaia (left) and the Temple of Athena Nike.

Drawing made during the first reconstruction 1835-1836. The grand Roman

stairway up to the Propylaia (marked "B" in the drawing) was first excavated

by Charles Ernest Beulé (see gallery page 6).

Drawing by architect Gustav Eduard Schaubert. From Ross, Schaubert and Hansen,

Die Akropolis von Athen nach den neuesten Ausgrabungen, Erste Abtheilung:

Der Tempel der Nike Apteros, plate IV. 1839. See note 6 below. |

| |

The Athena Nike Temple bastion during restoration work, August 2013, seen from

the grand stairway up to the Propylaia. To the left part of the south wing of the

Propylaia can be seen, as well as the top of the steps which led from the bastion

down to the stairway, which before Roman times was a pathway.

See illustrations of the inscriptions found at the top of the stairway on gallery page 8. |

| |

The north side of Athena Nike Temple from below the bastion.

See close-ups of the north frieze of the temple above. |

| |

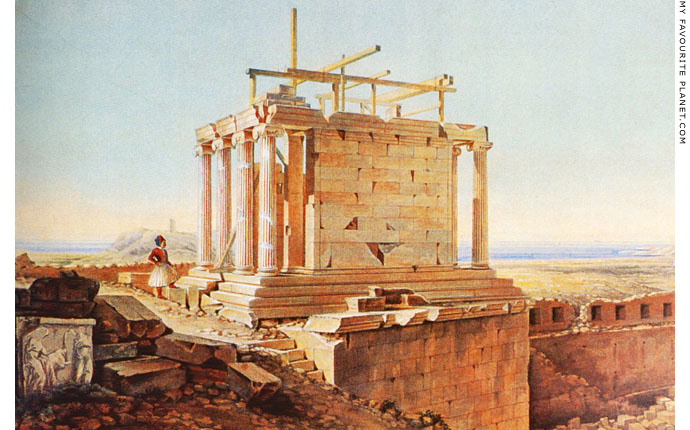

The Temple of Athena Nike during the reconstruction, painted by Hans Christian Hansen in 1836.

A slab of the parapet frieze lies on the ground in the left of the painting. |

| |

By 1934, following a survey of the Acropolis monuments, it became clear that the temple and the bastion itself were unstable and in danger of collapsing. Once again, it would have to be dismantled and rebuilt. The task was entrusted to civil engineer Nikolaos Balanos (1860-1942), Director of the Technical Service of the Greek Ministry of Public Instruction, who had already been involved in restoration work on the Acropolis since the earthquake of 1895 which caused severe damage to the Parthenon and other monuments. [9]

From 1935 Balanos dismantled the Temple of Athena Nike, and excavated the bastion down to the bedrock. It was then that the remains of the older temple were discovered. He took the controversial step of using concrete to support the bastion and as a foundation for the temple; the older cult site was preserved as a walled basement to the temple. By 1939 he had rebuilt the temple as far as the entablature but was then forced to retire due to ill health.

Balanos was succeeded by Greek architect and archaeologist Anastasios Orlandos (1887-1979), a fierce critic of his methods. Having previously made a thorough study of the temple, he corrected what he considered to be errors made by Ross, Pittakis and Balanos, including the position of blocks and architraves, and re-erected the columns and entablature. The reconstruction of the temple was completed in 1940. This was fortuitous timing as Athens was about to be invaded and occupied once again - this time by Nazi Germany.

The Second World War, the Greek Civil War and the ensuing political and economic chaos meant that very little more could be achieved in terms of restoration on the Acropolis. And once again the deterioration of the monuments were causing alarm. In 1971 a report by UNESCO on the state of the monuments pointed to damage caused by environmental pollution and errors made by restorers: for example, the corrosion, expansion and contraction of the iron clamps used to hold marble members together were discolouring and cracking the stone. The use of iron was common in the early restoration of ancient buildings and sculptures, even though many restorers already knew that the ancient Greek craftsmen had sheathed metal clamps in lead to mitigate these problems. At least Pittakis, Balanos and Orlandos must have been aware of this, but Balanos is particularly accused of ignoring many such accepted principles of restoration. [10]

Despite the desperate need for repairs, little was to be achieved during the military dictatorship, the Colonels' Junta of 1967-1974. in 1975, following Greece's return to democracy, the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments (CCAM) was formed, some remedial work was undertaken and discussions began on ways and means to effect larger scale repairs. Radical restoration began in 1979 with the reconstruction of the Erechtheion which took nine years. In 1999 the Acropolis Restoration Service (ARS) was established as part of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture to take over the direct organization of further work. The level of expertise in conservation and restoration techniques had meanwhile improved considerably, enlightened by new attitudes and assisted by new technologies. Careful studies of monuments were made before interventions, and proposals were discussed with invited international specialists.

The "Study for the Restoration of the Temple of Athena Nike" by architects Demosthenes Giraud and Kostas Mamaloungas received initial approval in 1994, and in 1998 the work of dismantling and rebuilding the temple for the third time began under the direction of Kostas Mamaloungas and civil engineer D. Michalopoulou. The first action was the removal of the frieze, which was transferred to the Acropolis Museum (the surviving pieces are now in the new Acropolis Museum), and eventually replaced by stone casts (see photos above).

Initially, the restoration was to be completed by 2004, but due to various unforeseeable technical difficulties, including the removal of metal and concrete used by Balanos, this deadline had to be extended more than once. In 2000 work began on dismantling the temple, which included removing 315 marble sections, each weighing up to 2.5 tons. Balanos' concrete cella floor was removed and replaced by a stainless steel grid, while other concrete additions were replaced with marble. Clamps of titanium were used in the place of iron. Great care was taken to replace the marble blocks of the cella walls in their correct positions, another detail which previous restorers had been unable to achieve - Balanos had even cut ancient blocks to fit spaces for which they were not intended. Two more original blocks had meanwhile been discovered, which meant that only ten blocks had to be replaced by new Pentelic marble.

As a matter of principle, newly added parts of the restored temple were deliberately intended to stand out from the originals, as can be seen in the photo at the top of the previous page. New parts have also be inscribed with the date of their addition. However, as has been observed in other recently restored buildings such as the Erechtheion (completed 1987), the new stone assumes a similar tone to the old quite rapidly.

Finally, the work was finished; the scaffolding around the temple was removed in September 2010. The Temple of Athena Nike now stands a metre taller than it did before the previous restoration, and looks better than it has done since at least 300 years.

Article: © copyright David John, Athens and Berlin, 2007-2011 |

Kyriakos Pittakis (1798-1863),

the first Greek archaeologist. |

| |

Nikolaos Balanos, Greek civil

engineer and archaeologist. |

| |

Anastasios Orlandos, Greek

architect and archaeologist. |

| |

| |

The Temple of Athena Nike in May 2007, surrounded by scaffolding during its third reconstruction. |

| |

Stacks of Ionic capitals at the east side of the Acropolis. |

| |

Restoration workers repair a column, May 2007.

photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

Since 1975 the Acropolis has been undergoing a lengthy, ambitious conservation and restoration programme. Much of the work had become necessary to prevent the ancient ruins from crumbling to pieces due to the damage caused by centuries of abuse, destruction and plundering of architectural elements, faulty earlier restorations, and more recently the effects of Athens' chronic air pollution and acid rain.

After Greece (or at least part of it) gained independence from Ottoman Turkey and the foundation of the new Greek State in 1830, the first task of restorers was to clear the rock of what was considered rubbish, rubble and post-classical buildings, as well as to sort stones and parts of the ancient monuments which had been removed or reused over the centuries. This process of discovering and matching the stones still continues today, and it has been estimated that over 20,000 scattered remnants have so far been discovered *. Restoration was continued by other archaeologists until 1940, with varying degrees of success. Many of the early restorers were either unaware of the techniques used by the ancient builders or were more interested in attaining quick results. The iron, for example, used to hold stonework together oxidized and endangered the structures (e.g. in the ceilings of the Propylaia); the Classical Greek builders had sealed the iron elements with molten lead.

During preparatory research for the modern restoration, much was discovered about the subtleties and precision of the Ancient Greek building methods, and many ideas concerning how the buildings were constructed and originally appeared had to be radically revised. It was decided to completely reconstruct some sections of buildings (the Propylaia, Parthenon, Erechtheion and Temple of Athena Nike) and enhance badly damaged parts with the help modern hi-tech methods. Historians, archaeologists, architects, geologists as well as civil, electrical and chemical engineers and members of many other professions (to say nothing of politicians and accountants) have cooperated to decide on the best ways to preserve the Acropolis. However, much of the implementation of all the careful preparation is down to the skills and labour of handworkers such as these stonemasons.

* Inventorying the Scattered Members of the Acropolis, E. Sioumpara.

The Acropolis Restoration News. 8 July 2008. Acropolis Restoration Service (YSMA). |

|

A restored lion-head

spout from the roof of

the Athena Nike Temple.

The new white marble

used by the restoration

workers contrasts with

the ancient stone. |

|

| |

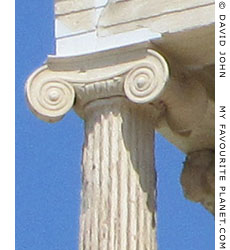

Newly-made capital of an Ionic column for the Athena Nike Temple, during restoration work, 2007. |

| |

The south side of the Athena Nike Temple, August 2013.

|

| It is difficult to be absolutely sure, but the Ionic capital of the south corner of the west porch of the Athena Nike temple (left in the photo above) looks very much like the capital in the photo a little further up the page, taken in 2007. |

|

|

|

| |

Temple of

Athena Nike

part 2 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Spon and Wheler

The French doctor and antiquarian Jacob Spon (1647-1685) and the English botanist (and later clergyman) George Wheler (1650-1723) travelled together through Italy to Greece, Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Levant in 1675-1676. Two of the first modern scholars who travelled to Greece specifically to investigate ancient sites, they recorded the antiquities they saw, transcribed inscriptions, and Wheler particularly collected plants, antiques and ancient coins. On returning to their respective homelands, each published accounts of their travels, which remained important guides for travellers and historians over the next two hundred years.

See:

Jacob Spon, Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grece, et du Levant, faités années 1675 et 1676, Tome II. Henry and Theodore Boom, Amsterdam, 1679. In French. At the Internet Archive.

In this edition, the Temple of Athena Nike is described in Livre V, Description d'Athenes, de Salamine, et du Golfe d'Egina,

pages 105-106.

George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book V, page 358. William Cademan, Robert Kettlewell, and Awnsham Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks. |

|

|

2. Stuart and Revett

James "Athenian" Stuart (1713-1788) and Nicholas Revett (1720-1804), English architects and artists, travelled through Italy, the Balkans and Greece 1749-1755. They arrived in Piraeus on 17 March 1751 and at Athens the following day. Between March and June 1753 they were forced to leave (for Smyrna via Delos and Chios) due to political unrest in the city.

A few months after their return they became involved in a serious dispute over money with Nikolaos Logothetis, the British Consul in whose house they were staying, and Stuart left Athens on 20 September 1753 for Constantinople (although he never got there). Revett finally left Athens on 27th January 1754 to meet him in Thessaloniki. Because of an outbreak of the plague they decided to return to England, arriving in 1755.

Despite the tumult of their stay in Greece, they managed to make the first accurate measurements and drawings of several ancient monuments, which appeared in their The Antiquities of Athens and Other Monuments of Greece, the first volume of which was published in 1762.

Their work had a great influence on the work of historians and architects, and Stuart went on to become a pioneer of the Classical Revivalist movement. He also continued to work sporadically on The Antiquities of Athens, the final volume of which was not published until 1816, 28 years after his death. The finished work consisted of 5 folio volumes, illustrated with 368 etched and engraved plates, plans and maps, all drawn to scale. See also note 7 below.

See: Lionel Cust and Sidney Colvin, History of the Society of Dilettanti, pages 75-81. Macmillan, London 1914, 1898. At the Internet Archive.

See also Acropolis gallery page 32, 8, 35 and 36.

Revett later made a second journey to Greece with Doctor Richard Chandler and William Pars.

Doctor Richard Chandler (1738-1810), English antiquarian, and later clergyman. 1764-1766 he travelled though western Anatolia and Greece with Revett and painter William Pars (1742-1782), on an expedition commissioned by the Society of Dilettanti to explore antiquities. James Stuart, Revett's former travel companion and colleague, was one of the Dilettanti who signed the explorers' instructions. They acquired several antiques, including parts of the frieze and metopes of the Parthenon, over forty years before Lord Elgin removed the so-called "Elgin Marbles" to London (see Losing their marbles, Edwin Drood's Column, 21 June 2011).

See: Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, Chapter IX, page 40. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

See also gallery page 8, 32, 36 and 36.

3. Edward Giffard, A short visit to the Ionian Islands, Athens, and the Morea. John Murray, London, 1837. At Google Books.

Edward Giffard (1812–1867) came from a distinguished Devon family and went on to become Secretary of the Transport Board. He did not pretend to be a great expert on ancient Greek history, art or architecture, and his short account of his journey through Greece with his college friend and artist F. W. Newton during January-February 1836 is modest, courteous, informative and often amusing.

He arrived in Athens just after the capital of the newly-formed Greek state had been moved to Athens and the restoration of the Acropolis, which included rebuilding the Athena Nike temple, had already begun.

Giffard recalls his meetings with Greece's first archaeologist, the Athenian Kyriakos Pittakis (see note 8), who had recently published his guide to Athens, L' ancienne Athènes ou la description des antiquités d' Athènes et de ses environs (1835), and was busy collecting ancient inscriptions, many of which are now in the Epigraphical Museum of Athens. Shortly after Giffard's visit, Pittakis was appointed Inspector of Antiquities.

The "Clarke" to whom Giffard refers, was Edward Daniel Clarke (1769-1822), who travelled 1799-1802 as the tutor of John Marten Cripps through Scandinavia, Russia, Turkey and Palestine. They visited Greece on their return journey to England, and were in Athens in October-November 1801. Clarke's account of this epic journey was published in six volumes as Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa.

During his travels Clarke collected minerals, manuscripts, sculptures and Greek coins. He received a doctorate from Cambridge University, and in 1808 was appointed its first professor of mineralogy.

Clarke's description of Athens can be found in:

Edward Daniel Clarke, Travels in various countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. 4th edition, Volume VI, Chapters IV-VI. T. Cadell and W. Davies, London, 1818. At Google Books. |

James "Athenian" Stuart

engraved by W. C. Edwards, after a painting by Richard Brettingham. |

| |

Portrait of Nicholas Revett

engraved by W. C. Edwards, after a painting by William Wilkins RA.

Portraits from frontispieces

to The Antiquities of Athens. |

| |

|

4. Reliefs from the Athena Nike temple in the British Museum.

See the following pages on the British Museum website www.britishmuseum.org:

The Parthenon Sculptures - Facts and figures.

Photo of a marble block from the west frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike.

5. Colonel William Martin Leake (1777-1860), English antiquarian and topographer, member of the Society of Diletantti. Leake was among the first modern writers to correctly identify the site of the temple following its dismantling by the Turks.

William Martin Leake, The Topography of Athens: with some remarks on its Antiquities. Second edition. J. Rodwell, London, 1841. Volume I, Section VIII, page 322.

The "Mr Wilkins" referred to by Leake was William Wilkins (1778-1839), English archaeologist, classical scholar and Greek Revivalist architect, who designed the National Gallery, London. After graduating from Cambridge, in 1801 he was awarded the Worts Travelling Bachelorship, worth £100 for three years, allowing him to commission the Italian landscape painter Agostino Aglio as a draughtsman to accompany him on his tour of Italy, Greece and Anatolia 1801-1804.

Wilkins' written works include Prolusiones Architectonicae, or Essays on subjects connected with Grecian and Roman architecture (1837) and Atheniensia, or remarks of the topography and buildings in Athens (1816).

"Colonel Leake, with a similar reliance on the judgement of his colleague [Charles Robert Cockerell *], calls a very unimportant building near the entrance to the Propylaia, the temple of Victory. Recent discoveries have brought to light the remains of a building, much more worthy the appellation of a temple, in the immediate neighbourhood. He now abandons his opinion, and leaves the little building to be, what I always considered it - a tomb, similar in design and extent to the numbers which are found on the shores of Asia-Minor [Lycian tombs]. I much question whether the site of the temple of Victory has as yet been discovered."

William Wilkins, Prolusiones Architectonicae, or Essays on subjects connected with Grecian and Roman architecture, page 96. John Weale, Architectural Library, London, 1837.

* For further information about the English architect and archaeologist Charles Robert Cockerell (1788–1863) see The Cheshire Cat Blog, July 2011.

6. Ross, Schaubert and Hansen... and Laurent?

Ludwig Ross (1806-1859), German-Danish archaeologist (son of a Scottish emigrant) who was appointed "Ephor of all antiquities in Greece" in 1832 by King Otto I, on the recommendation of court architect Leo von Klenze (1784-1864). It was Klenze who had proposed that the Classical monuments of the Acropolis should be restored and later additions removed, a concept which prevailed, and was later to be extended - even into the twentieth century - to other archaeological sites such as the Agora, at the expense of Byzantine, Frankish and Ottoman buildings.

Ross was instrumental in having the Acropolis demilitarized by convincing the Greek government to remove the general, who was quartered in the mosque in the Parthenon, and the troops whose barracks were the Propylaia. This also put an end to the daily firing of a cannon from the Acropolis at midday. For the first time in several centuries the Acropolis ceased to be a military fortress, and archaeologists had the freedom to work on recreating a cultural monument of world class.

Working with a variety of architects and archaeologists from several countries in the new field of restoration (or "intervention" as it was to become known), Ross attempted to apply systematic working methods.

Gustav Eduard Schaubert (1804-1860), Prussian architect and student of Karl Friedrich Schinkel. In 1832 he designed the layout of the modern centre of Athens with his college friend, Stamatios Kleanthis (Σταμάτης Κλεάνθης, 1802-1862), the Greek freedom fighter, architect and owner of marble quarries on Paros.

Hans Christian Hansen (1803-1883), Danish architect who spent 18 years in Greece 1833-1751. Following his archaeological work with Ross, Schaubert and others, he was appointed court architect to King Otto in 1834. Together with his brother Theophilus (who arrived in Athens in 1838), he designed several buildings in the new Greek capital, including the original main building for the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, part of the Neo-Classical "Athenian Trilogy", along with the Academy of Athens and the National Library of Greece, on Panepistimiou Street, and Saint Paul's Anglican Church, Filellinon Street.

Eduard Laurent, "an architect from Dresden", is mentioned as taking part in the restoration work on the Acropolis, but so far we have been unable to discover any further information about him or his involvement.

"All the other fragments of the [Nike] temple were discovered by Professor Ross and his coadjutors in the excavations of 1835; they had been built into a Turkish battery, which had in fact preserved them, and the temple was re-erected, chiefly under the superintendence of Herr Laurent, an architect of Dresden."

Thomas Henry Dyer (1804-1888), Ancient Athens its history, topography, and remains. Bell and Daldy, London, 1873. Page 373. At the Internet Archive.

Laurent is mentioned by Ludwig Ross in his own report on the restoration of the temple in 1835-1836:

"Nach einer Unterbrechung der Arbeit auf mehre Monate wurde im December die Wiederaufrichtung des Tempels begonnen, und bis jetzt fast vollendet. Bei diesem letzteren Geschäfte hat der Architekt Herr E. Laurent aus Dresden grösstentheils die Aufsicht geführt. Nur an den drei zerbrochenen Säulen wurden neue Tambours aus Pentelischem Marmor eingefügt, und eine Basis aus demselben Material neu verfertigt, einige mangelnde, oder halbzerbrochene Quadern der Cellamauer aber durch neugearbeitete Stücke aus Porosstein ersetzt."

"Following an interruption of the work lasting several months, the reconstruction of the temple was begun in December and is now nearly completed. This last work was mostly supervised by the architect Herr E. Laurent of Dresden. New drums of Pentelic marble were introduced only for three broken columns, and a new base of the same material was manufactured; a few missing or half-broken blocks of the cella wall were replaced by newly-worked pieces of poros stone." (Translation by David John)

Ludwig Ross, Eduard Schaubert, Christian Hansen, Die Akropolis von Athen nach den neuesten Ausgrabungen, Erste Abtheilung: Der Tempel der Nike Apteros, page 3. Verlag von Schenk und Gerstaecker, Berlin, 1839. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

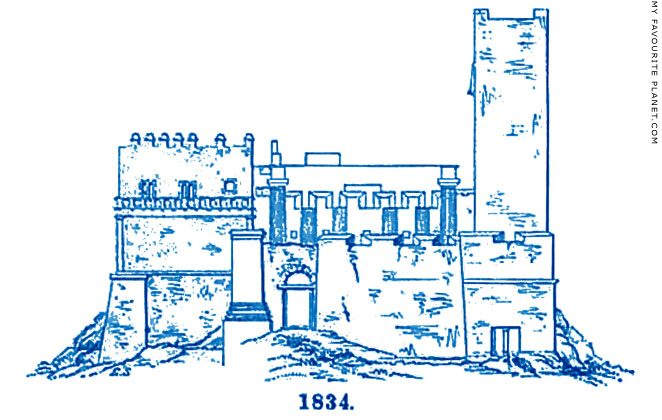

BEFORE: The western end of the Acropolis in 1834, before the beginning of

excavation and restoration work around the Propylaia and the Athena Nike Temple. |

| |

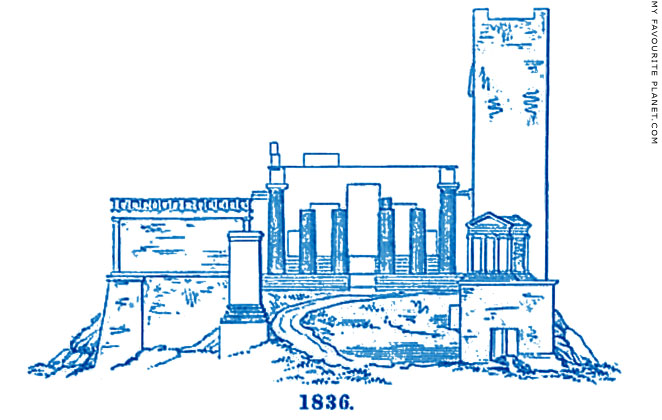

AFTER: The entrance to the Acropolis in autumn 1836, after the first excavations,

demolition of Medieval and Turkish fortifications around the Propylaia and the

reconstruction of the Temple of Athena Nike (right).

The tall 14th century Frankish Tower (right) built by Nerio I Acciaioli,

the Florentine Duke of Athens, was still standing,

but Heinrich Schliemann financed its demolition in 1874.

Title-page vignettes from Ross, Schaubert, Hansen,

Der Tempel der Nike Apteros, 1839 (see note 6 above).

See a painting of the tower and other fortifications, made in the 1750s by

James Stuart, on gallery page 1, and two others painted nearly a century later

by Carl Wilhelm von Heideck (gallery page 8) and William Page (gallery page 32). |

|

7. Stuart and Revett vindicated

There is a certain irony to the growing importance to archaeologists of Stuart and Revett's work. At the time of the publication of their The Antiquities of Athens (see note 2 above), they had been criticized for concentrating too much on minor monuments, such as the Ilissos Temple and the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, but their efforts were later to a certain extent vindicated. At the time of their stay in Athens it was extremely difficult to obtain permission to study the Acropolis and other monuments from the Turkish authorities who distrusted the motives of foreign antiquaries.

8. Ludwig Ross and Kyriakos Pittakis

There were disagreements between Ross and the Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis (Κυριάκος Πιττάκης, 1798-1863), who, as a nationalist, believed that Greeks should be running things themselves. As a result, in 1836 Pittakis took over as Ephor. Ross continued his involvement in archaeological investigation, and became the first Professor of Archaeology at the newly-founded University of Athens in 1837. In 1843, however, the Greek nationalists forced King Otto to install Greeks in posts held by foreigners, and Ross lost his job. He returned to Germany, where, due to his reputation and with the help of influential friends and colleagues such Alexander von Humboldt, he was appointed Professor of Classical Archaeology at Halle University in 1845.

9. Nikolaos Balanos (1860-1942), Greek civil engineer and archaeologist.

Obituary: "Necrology" by "W.B.D" (William Bell Dinsmoor), Archaeological News and Discussions. American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 47, No. 3 (July-September 1943), page 331. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org.

History has not treated Balanos well, and despite his over 40 years of dedication and hard work attempting to save the Acropolis monuments with "unremitting care and skill" (Dinsmoor), he is now remembered mostly for the problems caused by his errors and for abandoning the basic principles of restoration he himself helped develop. Damned by faint praise, he is often decribed as "well-intentioned" but... Very little has been written about the man himself, and he did not publish much of his work, despite having carefully documented it with notes, drawings and photographs.

10. Lead used in Acropolis buildings

A popular anecdote about Pittakis from the time of the Greek War of Independence confirms his knowledge of the use of lead in ancient buildings. He served as a soldier in the Greek army during the siege of the Acropolis in 1821, and heard that the Turkish defenders were melting the lead from the monuments to make bullets. This so alarmed the young archaeologist that he suggested that lead should be sent to the Turks to save the buildings from further damage.

The anecdote was recounted by Greek statesman, archaeologist and poet Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (Ἀλέξανδρος Ῥίζος Ῥαγκαβής, 1809-1892) in the speech he gave at Pittakis' funeral on 24 October 1863.

"After Pittakis had heard what was happening and had conferred with his fellow-soldiers, the Athenians sent a quantity of lead bullets to the Ottomans on the Acropolis so that they might desist from their acts of destruction. Those who in the old days fed their starving enemies performed an act of philanthropy, but no nobler action in time of war than this, worthy of the highest civilisation, can ever have been undertaken."

Quoted in Refutation of certain persistent myths, published by the British Committee for the Restitution of the Parthenon Marbles, 2001.

"In 1821 during the War of Independence, the Acropolis was being besieged by the Greeks. The Ottomans holding the citadel ran out of lead to make bullets with, and started to remove the lead clamps linking the marble pieces, thus threatening those beautiful monuments with destruction. Young Pittakis was then a soldier in the ranks of the besieging army. From the military point of view the embarrassment in which the Ottomans found themselves was welcome, but looking at it from the archaeological point of view Pittakis at once saw the dangers involved. Thanks to his efforts the threat to the monuments from the removal of the lead clamps was averted, when it was agreed that the Greeks themselves should provide the Ottomans with the lead they needed."

From the obituary for Kyriakos Pittakis, in the Greek Journal Chrysalis, October 1863.

Other contemporary references to the function of lead in ancient buildings include a remark by Francis Arundell, a British chaplain at Smyrna (Izmir), on his visit to Sardis in April 1826:

"Of the temple of Cybele, only two pillars remain at present; the Turks have recently destroyed the rest, for the sake of the lead connecting the blocks."

Reverend Francis Vyvyan Jago Arundell (1780-1846), A visit to the seven churches of Asia, page 179. John Rodwell, London, 1828. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

| |

The Temple of Athena Nike. View from the North-East.

Painted by Werner Carl-Friedrich (1808-1894) in 1877.

Benaki Museum, Athens. Inv. No. ΓΕ 23956. |

| |

The Athena Nike Temple bastion in 2015,

after the completion of the latest restoration. |

| |

The Athena Nike Temple in 2015. The newly restored parts are in whiter marble. |

| |

The Athena Nike Temple newly restored.

Unfortunately, because of the continuing restoration work on

the Propylaia, it is still not possible to get closer to the temple. |

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|