|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Doidalsas |

|

| |

Doidalsas

Doidalsas (Δοίδαλσας, also referred to as Daidalos, Daedalsas, Doedalsas, Doidalses, etc [1]), is believed by some modern scholars [2] to have been a Greek sculptor from Bithynia (Βιθυνία), northwestern Anatolia, working in the 3rd or 2nd century BC. The theories underpinning this belief are based on vague or questionable references in works by ancient and Medieval authors, as well as a few inscriptions. Other scholars have refuted the theories concerning his life and work and even doubted that he ever existed.

The debate concerning the existence of Doidalsas may be seen as a good example of how such theories about aspects of ancient history, some resting on a thin literary foundation, may become generally accepted in the academic world, only to slide out of favour when they are seriously challenged. In some cases theories may stand fast or fall like a house of cards according to fresh approaches to research, deeper study or even new archaeological discoveries.

The modern story of Doidalsas began when 19th century scholars were battling with surviving Latin manuscripts of Pliny the Elder's Natural history, all of which are incomplete and contain now illegible passages, errors, corruptions and alterations made by copyists over the centuries. At the end of a short passage in Book 36, chapter 4, in which Pliny discussed marble statues in the Porticus Octaviae (Portico of Octavia) in Rome, is a clause which is unclear, perhaps corrupt. In most manuscripts it appears as: "Venerum lavantem sesededalsa stantem Polycharmus", which made no sense. However in just one manuscript, the Bamberg Codex, "sesededalsa" appears as "sesedaedalsas". This was separated into two words thus creating the name "Daedalsas":

"intra octaviae vero porticus aedem iunonis ipsam deam dionysius et polycles aliam, venerem eodem loco Philiscus, cetera signa Praxiteles. iidem polycles et dionysius, timarchidis filii, iovem, qui est in proxima aede, fecerunt, pana et olympum luctantes eodem loco heliodorus, quod est alterum in terris symplegma nobile, venerem lavantem sese daedalsas, stantem polycharmus."

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

"In the Temple of Juno, within the Porticos of Octavia, there is a figure of that goddess, executed by Dionysius, and another by Polycles, as also other statues by Praxiteles. This Polycles, too, in conjunction with Dionysius, the son of Timarchides, made the statue of Jupiter, which is to be seen in the adjoining temple. The figures of Pan and Olympus Wrestling, in the same place, are by Heliodorus; and they are considered to be the next finest group of this nature in all the world. Daedalsas executed a Venus Bathing and Polycharmus a Venus Standing."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. [3]

Thus at the end of the emended passage there were now two sculptors, Daedalsas and Polycharmus (see Polycharmos), neither mentioned by Pliny elsewhere, each of whom made a statue of the goddess Venus (Aphrodite, Αφροδίτη). As in many cases in the Natural history, the Greek artworks mentioned as standing Rome in Pliny's time had been been looted by Romans from around the Greek world. But we are given no further information about this Daedalsas or told when or where this statue of Venus Bathing (or washing) was made. So who could he have been?

It was recalled that the Byzantine Archbishop Eustathios of Thessaloniki (circa 1115-1196 AD), in his commentary on the lost geographical work by Dionysios Periegetes (2nd or 3rd century AD), cited the Bithynian historian Arrian of Nikomedeia (circa 86-160 AD) as recording that a Daidalos (Δαίδαλος) made an admirable bronze statue of Zeus Stratios for Nikomedeia (Νικομήδεια, modern İzmit, Turkey), the capital of Bithynia (Βιθυνία), northwestern Anatolia. The city was founded on the southeast coast of the Propontis (Sea of Marmara) around 264 BC by the Bithynian king Nikomedes I (Νικομήδες Α΄, ruled circa 280-255 BC), so this sculptor would have been working around or after this time.

"... και δημιουργόν τίνα ίστορεί πάρα Βιθυνοϊς Δαίδαλον χαλοΰμενον, ου έργον εν Νικομήδεία γενέσθαι θαυμαστόν άγαλμα Στρατιού Διός."

"Porro regionem ad Psillium fluvium sitam Rebantiam dicit, atque artificem quendam apud Bithynos, Daedalum nomine, memorat, cujus opus Nicomediae sit admirabile signum Jovis Stratii. Idem Arrianus refert apud alios referri Odrysi filios esse Thynum et Bithgnum, a quibus regiones nominatae sint." [4]

Little is known of the attributes or worship of Zeus Stratios (Διὸς στρατίος, Zeus of Armies, or Warlike Zeus), except that he appears to have been a war god and that the rites of his cult appear to have been adapted from Persian religion. Herodotus wrote that the sanctuary of Zeus Stratios at Labraunda (Λάβραυνδα) in Caria was a "large and a holy grove of plane trees" and that "the Carians are the only people whom we know who offer sacrifices to Zeus by this name". (Herodotus, Histories, Book 5, chapter 119, section 2) [5]

The statue of Zeus Stratios may be the figure on coins of Hellenistic kings of Bithynia minted in Nikomedeia, including silver tetradrachms of Prusias I (Προυσίας ὁ Χωλός, the Lame, ruled circa 230-182 BC) and Prusias II (Προυσίας ὁ Κυνηγός, the Hunter, ruled circa 182-149 BC). The god is shown holding a wreath in his outstretched right hand and a staff in the left ( see image below). |

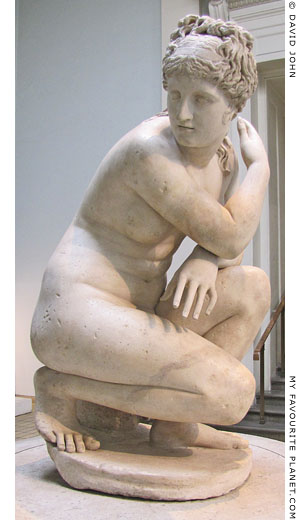

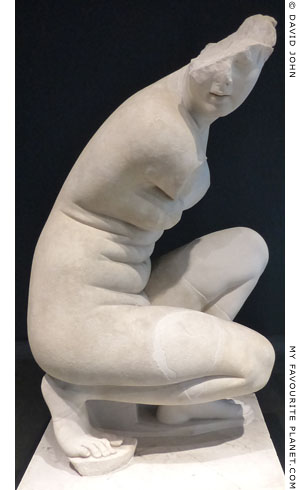

"Lely's Venus", a marble statue of the

Crouching Aphrodite type. 1st - 2nd

century AD Roman copy of a 2nd century

BC Greek original. Height 125 cm.

British Museum. Inv. No. 1963. 10-29. 1.

The statue was first recorded in a 1627

inventory of the Gonzaga collection in

Mantua, where it was seen by the painter

and diplomat Peter Paul Rubens. In

1627-1628 it was purchased for Charles I

of England. Following the king's execution

in 1649 it was purchased by the artist Sir

Peter Lely (1616-1680), after whom it was

named. In 1682, after Lely's death it was

reacquired for the Royal Collection, and

in 2005 was loaned by Queen Elizabeth II

to the British Museum. |

| |

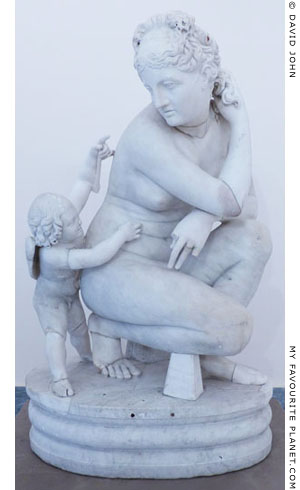

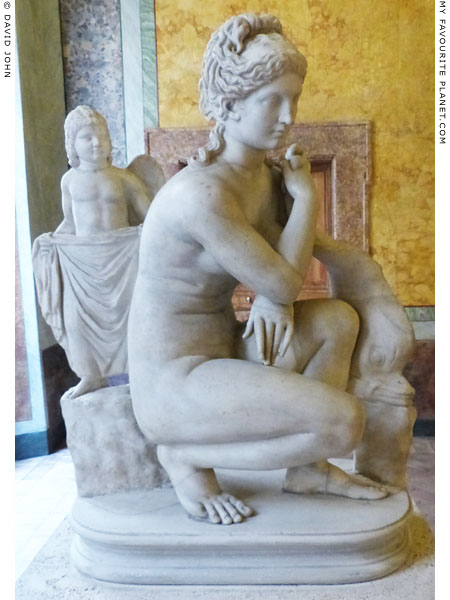

Drawing of "La Vénus de Vienne", a

marble statue of the Crouching Aphrodite

type. Part of Eros' left hand can be seen

on the back of the now headless figure.

1st - 2nd century AD. Parian marble.

Excavated 1828 in the Roman baths of

Saint-Romain-en-Gal, eastern France.

Height 140 cm, width 42 cm, depth 60 cm.

Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 2240.

Purchased 1878 from

the Gerantet Collection.

Source: Théodore Reinach, L'auteur de

la Vénus accroupie. In: La Gazette des

Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1897. pages 314-324,

Drawing on page 319 by Ch. Goutzwiller.

At Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

| |

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin of Prusias I Choloss of Bithynia (Προυσίας ὁ Χωλός,

the Lame; lived circa 243-182 BC, ruled circa 230-182 BC).

On the obverse side (left), the head of Prusias I in profile, facing right. On the reverse side

stands a bearded god, facing left, wearing a himation (cloak), perhaps the statue of Zeus

Stratios at Nikomedeia. He holds an olive wreath in his outstretched right hand and a staff

in the left. To the left of his waist is the god's thunderbolt symbol, above a monogram.

The same figure also appears on silver tetradrachms of Prusias II (ruled circa 182-149 BC).

Cabinet de Luynes, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris.

Source: Théodore Reinach, L'auteur de la Vénus accroupie. In: La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris,

1897, pages 314-324, illustration on page 321. At Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France. |

| |

Despite Eustathios' artist being referred to as Daidalos, the well-known name of the mythical Athenian artist Daidalos and Daidalos of Sikyon, a sculptor of the Classical period, he became identified as Pliny's Daedalsas, who was now thought to have been a Bithynian. As it happens the name Doidalsas (or one of the variants, see note 1) appears to have some importance in the history of the kingdom. The geographer Strabo related how the city of Astakos (Ἀστακὸς) in Bithynia was founded by colonists from Megara and Athens, and some time later refounded by Doidalsos (Δοιδαλσος). [6] After it was destroyed by Lysimachus (circa 360-281 BC), one of Alexander the Great's successors, it was replaced by the nearby Nikomedeia.

"Next follows the coast of the Chalcedonians, the bay of Astacus, as it is called, which is a part of the Propontis.

Here Nicomedia is situated, bearing the name of one of the Bithynian kings by whom it was founded. Many kings however have taken the same name, as the Ptolemies, on account of the fame of the first person who bore it.

On the same bay was Astacus, a city founded by Megareans and Athenians; it was afterwards again colonized by Doedalsus. The bay had its name from the city. It was razed by Lysimachus. The founder of Nicomedia transferred its inhabitants to the latter city."

Strabo, Geography, Book 12, chapter 4, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Much the same information was given by Memnon of Herakleia, who dated the foundation of Astakos to the beginning of the 17th Olympiad (712 BC) and named Dydalsos (Δυδαλσος) as the ruler after "the Athenians sent settlers there to join the Megarians". [7]

Doidalsas (or a variant) is thought to have been or have become a Bithynian name, perhaps a Hellenized form, and related to the name Daidalos. Like other areas of Anatolia (Asia Minor), Bithynia was inhabited by a mixture of peoples: as well as the Greek colonists, there were also indiginous Anatolians and Thracian immigrants from around the Strymon River who had been ousted from their homelands. [8] The name does not seem to have been very common but appears on a small number of ancient inscriptions, including a few from Bithynia.

The British orientalist William Ouseley (1767-1842) found such an inscription by the side of the road at Sabanjeh (ancient Sophon), near Izmit, as he travelled through Bithynia on 30th August 1812, on his way home from Persia (Iran). Reading the Greek name Ἀρριανὸς Δοιδαλσοῦ (Arrianos, son of Doidalsos) on the low base of an ancient funeral monument, he believed he may have found the gravestone of the historian Arrian of Nikomedeia. He sent news of his discovery and a drawing of the inscription to The Classical Journal in London, but it was not received with the enthusiasm or excitement he may have hoped for. [9]

Ἀρριανὸς

Δοιδαλσοῦ

ζήσας ἔτη

μηʹ.

χαίρετε.

Arrianos, son of Doidalsos,

died in the fourty-eighth year of his age.

Fare thee well.

Inscription TAM IV,1 182 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

So, the hypothetical reconstruction was coming along, with attention shifted from "Daedalsas" and his statue in Rome, to "Doidalsas" and his statue in Bithynia. All that was then needed was to establish a connection between Doidalsas and the "Venus Bathing". It had already been suggested (e.g. by Ennio Quirino Visconti, Karl Otfried Müller and Heinrich Brunn) that it had been the model for the several known Roman Imperial period statues of the "Crouching Aphrodite" type, when in 1897 the French archaeologist Théodore Reinach (1860-1928) published an article in which he attributed to Doidalsas the original statue, and dated it to the mid or late 3rd century BC. [10] Reinach's arguments, based on literary and epigraphical evidence, were applauded by many scholars and his hypothesis accepted. Even recent books and articles have referred unquestioningly to examples of Crouching Aphrodite type statues in various museums as being copies "of a work by Doidalsas". [11]

Doidalsos came to be seen as an artist made "famous" by his Bathing Aphrodite, and it was even believed that "he was a member of the school of Lysippus and the official sculptor of the court of the king of Bithynia Nicomedes I". [12] A further belief circulated, based on another report in the Natural history. Pliny twice mentioned a story in which the people of Knidos in Caria refused to sell the marble Aphrodite of Knidos (Venus of Cnidus) statue by Praxiteles to King Nikomedes, even though he offered to pay off their considerable public debt in return. [13] So it was imagined that Nikomedes may have commissioned Doidalsos to make the Bathing Aphrodite as a kind of consolation.

Among the critics of the constructed story of Doidalsas was the British archaeologist Eugenie Sellers Strong (1860-1943), who had in 1896 already completely rejected the emended Pliny clause and the resulting "Daedalsas", as well as the speculative connection of "Venus Bathing" to the Crouching Aphrodite or Daidalos of Bithynia. She noted that one argument for this was the depiction of the figure on Bithynian coins:

"The current attribution of the Venus lavans se to one Daidalos of Bithynia, known only on the authority of Eustathios (Schriftqu. 2045), which seemed to receive support from the recurrence of a crouching or bathing Aphrodite on Bithynian coins (see Bernoulli, Aphrodite, p. 317), must also be renounced; the type on the coins occurs elsewhere, and belongs to a series whose origin can be traced back to high antiquity (cf. Friederichs-Wolters, p. 571)." [14]

The most serious challenge to the Daedalsas / Doidalsas / Crouching Aphrodite construct came in 1969 from the German archaeologist Andreas Linfert (1942-1996) who had made a thorough reexamination of the available evidence. [15] However, it is not as if Linfert cleansed the Augean stables of academic theory from fanciful conjecture using a patented mixture of pure logic and reason. Although, to the satisfaction of some scholars, he appeared to have sluiced out Doidalsas, he also laid his own speculations, including the idea that Polycharmos made both the statues of Aphrodite mentioned by Pliny. Perhaps this will lead to someone imagining a Rhodian school of Polycharmos.

For scholars such as Jane Francis the apparent demise of Doidalsas was seen as liberating: if he was removed as the purportive author of the Crouching Aphrodite type, then so were the geography, chronology and stylistic interpretations associated with him. This allowed study to be focused on the Crouching Aphrodite statues themselves, to see them in a new light and reevalue them as works of art. [16]

While some continued to refer to Doidalsas and "Doidalsas's Aphrodite" [see note 11], in many cases this may have been merely in keeping with what had become a convention, or as Leonard Barkan put it, "he is simply a philological coinage". [17] For over a century there have also been scholars who have refused to deny the existence of Doidalsas when discussing related matters, perhaps out of professional deference or because they had other fish to fry. Other writers appear to either be ignoring the question or avoiding giving an opinion on it - even those who are often quite free with adjectives such as "Lysippean" and "Praxitelean".

There remain some holdouts who refuse to allow Doidalsas / Daedalsas to be killed off so easily. In 2004 Antonio Corso was still ready to come to his defence:

"Attempts to deny the connection of the crouching type of Aphrodite with the sculptor Daedalsas, and even doubt the existence of Daedalsas (see, e.g., J. Francis, The Roman Crouching Aphrodite. Mouseion 6.3.2 (2002) 211-44) seem unconvincing (see Corso (nt. 125) 11-36, particularly 22-3, with nt. 137)." [18] |

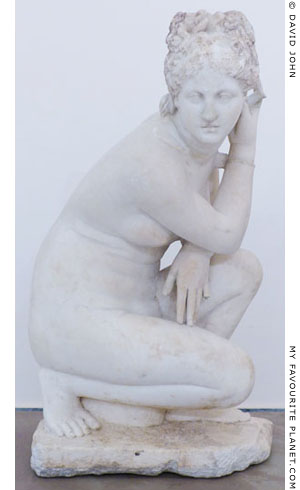

Crouching Aphrodite with Eros (Cupid).

Marble. Mid 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6293. Farnese Collection. |

| |

Crouching Aphrodite statue.

Marble. Mid 2nd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6297. Farnese Collection. |

| |

Crouching Aphrodite statue found in

1914 at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli. Despite its

now fragmentary state, it is considered

artistically the best example.

Marble. Hadrianic period (117-138 AD).

Height 107 cm.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National

Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 108597.

One of two statues of the type on display

in the museum. The other, Inv. No. 60750,

mid 2nd century AD, has no head. |

| |

| |

A marble statue of the Crouching Aphrodite type from Rome.

Behind the goddess a winged infant Eros, standing on a rock, holds up

a towel for her. To her right is a leaping dolphin. Her head, right forearm

and hand, part of her left hand and right foot have been added by

restorers. Also added is Eros' head and part of the dolphin.

Roman Imperial period. Thasian marble.

"The work, a Roman copy of a bronze original by the sculptor Doidalsas,

was commissioned in the 3rd century B.C. by King Nicomedes of Bithynia

in Aisa Minor and it is also known from depictions on Roman coins issued

in the same area." Museum label.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 8564.

From the Boncompagni Ludovisi Collection. |

| |

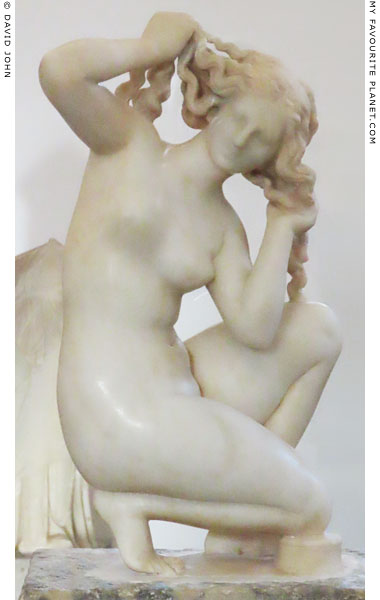

The "Aphrodite of Rhodes" (or "Venus of Rhodes"),

a highly polished white marble statuette of the

goddess bathing, thought to be a reworking of the

idea of Doidalsas' Crouching Aphrodite statue type.

1st century BC.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4685. |

| |

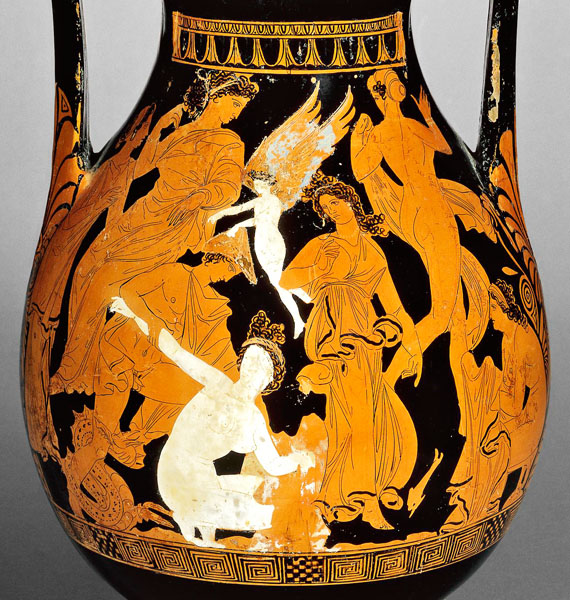

Peleus seizing Thetis on an Attic red-figure pelike by the Marsyas Painter, circa 350-340 BC.

The white figure of Thetis, naked and kneeling at her bath, is considered the earliest known

depiction of the pose in which the Crouching Aphrodite type figures are shown. Even her

hairstyle is similar to that on the statues.

Found in Kameiros, Rhodes. Purchased in 1863 by Charles Newton for the British Museum

from Auguste Salzmann and Alfred Biliotti who conducted excavations and dealt in antiquities

on Rhodes. Height 43.3 cm, width 27.50 cm, weight 4 kg.

British Museum, London. Inv. No. 1862,0530.1 (Vase E 424).

|

In the centre the white figure of Nereid Thetis (Θέτις, later mother of Achilles), while crouching to bathe on a rocky shore, is surprised by the mortal Peleus (Πηλεύς), who she will eventually marry (see Hephaistos). All the other figures are red apart from Eros, who is also white and flies above Peleus holding a wreath. To the left, Aphrodite (mother of Eros), fully dressed in a himation, sits at a higher level and looks down on the central scene. The other female figures are Thetis' Nereid sisters.

Side B shows beardless Dionysus seated between a Satyr and a Maenad.

Another depiction of Peleus capturing Thetis on an Attic red-figure pelike, painted by The Painter of Athens 1472, is so similar in design that it is thought the two artists worked together in the same wokshop. Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, Inv. No. 1993.49. [19]

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum.

See: www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1862-0530-1 |

|

|

| |

| Doidalsas |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Doidalsas - the name variants

There are several variants of what may have been the same name as it appears in ancient Greek and Latin literature, inscriptions and modern publications. Some of the variants are discussed in this article and its footnotes.

The first part of the name (or names) is variously spelled: Daed-, Daid-, Doed-, Doid-, Dyd-.

Varieties of the second part: -alos, -alsas, -alses, -alsos, -alsus.

Daedalos or Daidalos (Δαίδαλος)

Daedalsas

Doedalsas

Doidalsas (Δοίδαλσας)

Doidalses (Δοιδάλσης)

Doidalsos (Δοιδαλσος)

Doedalsus

Dydalsus (Δύδαλσος)

2. "Modern scholars"

The meanings of the terms "modern" and "scholar" may be obvious to many people, particularly those used to reading about historical matters, but not to everybody.

On this website, in articles about history (particularly ancient history), "modern" usually refers to the historical period - especially in "Western world"- since the mid-late 15th century AD, around the beginning of the Renaissance. Key events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the conquest of Granada by the Spanish in 1492 and Columbus' voyage to the Americas in the same year, are seen to mark the end of the Medieval period (the Middle Ages) and the start of a new phase in political, social, religious, philosophical, scientific, technological and artistic activities.

"scholar" is a vague and perhaps old-fashioned term used to mean a person who researches particular subjects in depth. This no longer necessarily implies a reclusive academic working in an ivory tower or an institution such as a university. Many researchers today are independent, and new technologies mean they need no longer be trapped in dusty libraries.

In the context of this page's subject the scholars are mostly historians, archaeologists, philologists and epigaphists, as well as museum directors and curators.

3. Pliny the Elder and "Daedalsas"

The Latin text is from Mayhoff's 1906 edition, online at Perseus Digital Library, which includes the emended sentence mentioning Daedalsas:

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book 36, chapter 4. Edited by Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. Teubner, Leipzig, 1906. At Perseus Digital Library.

I usually prefer to quote from the 1855 English translation of Pliny by Bostock and Riley, which is also at Perseus Digital Library. However, this does not mention Daedalsas, since the emendation was made after they produced their edition. I have therefore replaced the last sentence in the quotation above. Bostock and Riley's version reads like this:

"In the Temple of Juno, within the Porticos of Octavia, there is a figure of that goddess, executed by Dionysius, and another by Polycles, as also other statues by Praxiteles. This Polycles, too, in conjunction with Dionysius, the son of Timarchides, made the statue of Jupiter, which is to be seen in the adjoining temple. The figures of Pan and Olympus Wrestling, in the same place, are by Heliodorus; and they are considered to be the next finest group of this nature in all the world. The same artist also executed a Venus at the Bath, and Polycharmus another Venus, in an erect posture."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. Translated by John Bostock and H. T. Riley. Taylor and Francis, London, 1855. At Perseus Digital Library.

Although the Loeb Classical Library translation by Rackham, Jones and Eichholz does mention Daedalsas, this edition, published around a century after that of Bostock and Riley, seems the more old-fashioned rendering of the text. As you can see there are also several differences in the translations.

"... and in the temple of Juno that stands within the Portico of Octavia the image of the goddess herself was made by Dionysius, although there is another by Polycles, while the Venus in the same place was executed by Philiscus and the other statues by Praxiteles. Polycles and Dionysius, who were the sons of Timarchides, were responsible also for the Jupiter in the adjacent temple, while in the same place the Pan and Olympus Wrestling, which is the second most famous grappling group in the world, was the work of Heliodorus, the Venus Bathing of Daedalsas, and the Venus Standing of Polycharmus."

Pliny's Natural History, translated by H. Rackham (volumes 1-5, 9), W. H. S. Jones (vols. 6-8) and

D. E. Eichholz (volume 10). Loeb Classical Library. Published in 10 volumes by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, and William Heinemann, London, 1949-1954. The entire work on one web page, with an introduction and table of contents. At Jon Lange's fascinating Masseiana website.

In the first complete modern edition of Natural history in Latin, edited by Julius Sillig (published in Leipzig, 1831-1836), the questionable clause had been emended to: "venerem lavantem se, sed et aliam stantem polycharmus." Théodore Reinach was later to comment: "Personne ne défend plus aujourd'hui l'audacieuse correction de Sillig." ("Nobody today still defends Sillig's audacious correction.") L'auteur de la Vénus accroupie, Paris, 1897, page 317 [see note 9].

4. Eustathios of Thessaloniki / Dionysius Periegetes / Arrian on Daedalos

Gottfried Bernhardy, Dionysius Periegetes : [Opera omnia] graece et latine, cum vetustis commentariis et interpretationibus, line 793. Weidmann, Leipzig, 1828. At the Internet Archive.

Also: Johannes Adolf Overbeck, Die antiken Schriftquellen zur Geschichte der bildenden Künste bei den Griechen (The ancient wriitten sources on the history of Greek visual arts), No. 2045, page 394. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig, 1868. At the Internet Archive.

Eustathios of Thessalonica (Εὐστάθιος Θεσσαλονίκης, Eustathios of Thessaloniki, circa 1115-1196), a Byzantine archbishop of Thessaloniki and scholar who wrote several works, including commentaries on Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey. Editions of the commentaries are referred to by titles such as Παρεκβολαὶ εἰς τὴν Ὁμήρου Ἰλιάδα καὶ Ὀδύσσειαν and Eustathii archiepiscopi Thessalonicensis commentarii ad Homeri Iliadem pertinentes, often abreviated, e.g. "ad Hom. Il.". His commentary on the lost geographical work by Dionysios Periegetes (Διονύσιος ὁ Περιηγητής, 2nd or 3rd century AD) is often referred to as Scholia on Dionysios Periegetes (Σχόλια στο Διονύσιο Περιηγητή).

The reference to Daidalos' statue of Zeus Stratios by Arrian of Nikomedeia may be a fragment from his Bithyniaka, a now lost history of Bithynia in eight books, quoted several times by Eustathios.

5. Zeus Stratios and Labraunda

For accounts of rites performed for Zeus Stratios, see: Appian (Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς, circa 95-165 AD), The Mithridatic Wars, chapter 9, section 66 and chapter 10, section 70. Translated by Horace White. The Macmillan Company, New York, 1899. At Perseus Digital Library.

Labraunda was an inland village in the territory of the city Mylasa (Μύλασα), around half way between Miletus and Halicarnassus. Strabo described the situation in the first century AD.

"The Mylasians have two temples of Zeus, Zeus Osogo, as he is called, and Zeus Labrandenus. The former is in the city, whereas Labranda is a village far from the city, being situated on the mountain near the pass that leads over from Alabanda to Mylasa. At Labranda there is an ancient shrine and statue of Zeus Stratius. It is honored by the people all about and by the Mylasians; and there is a paved road of almost sixty stadia from the shrine to Mylasa, called the Sacred Way, on which their sacred processions are conducted. The priestly offices are held by the most distinguished of the citizens, always for life. Now these temples belong peculiarly to the city; but there is a third temple, that of the Carian Zeus, which is a common possession of all Carians, and in which, as brothers, both Lydians and Mysians have a share."

Strabo, Geographica, Book 14, chapter 2, section 23. At Perseus Digital Library.

6. Strabo on Doidalsos and Astakos

Both English translations of Strabo's Geography online at Perseus Digital Library have Latinized versions of Greek names, including "Doedalsus" for Doidalsos, but the Greek text shows "Δοιδαλσος".

Strabo, Geographica, Book 12, chapter 4, section 2. In Greek. Edited by A. Meineke. Teubner, Leipzig, 1877. At Perseus Digital Library.

7. Memnon of Herakleia

Memnon of Herakleia (Mέμνων, circa 1st century AD) was a Greek historian, probably from Herakleia Pontika (Ἡράκλεια Ποντική), a Bithynian city on the other side of the country, north of Astakos and Nikomedeia, on the south coast of the Black Sea (Euxine or Pontos). It was also founded by colonists from Megara around the end of the 8th century BC. Parts of Memnon's History of Herakleia have survived in excerpts summarized by Photios I (Φώτιος Α΄, circa 810/820 - 893 AD), Patriarch of Constantinople, in his Bibliotheka (Βιβλιοθήκη).

"Nicomedes enjoyed great prosperity, and founded a city named after himself opposite Astacus. Astacus was founded by settlers from Megara at the beginning of the 17th Olympiad [712 BC] and was named as instructed by an oracle after one of the so-called indigenous Sparti (the descendants of the Theban Sparti), a noble and high-minded man called Astacus. The city endured many attacks from its neighbours and was worn out by the fighting, but after the Athenians sent settlers there to join the Megarians, it was rid of its troubles and achieved great glory and strength, when Dydalsos was the ruler of the Bithynians.

Dydalsos was succeeded by Boteiras, who lived for 76 years, and was in turn succeeded by his son Bas. Bas defeated Calas the general of Alexander, even though Calas was well equipped for a battle, and kept the Macedonians out of Bithynia. He lived for 71 years, and was king for 50 years. He was succeeded by his son Zipoetes, an excellent warrior who killed one of the generals of Lysimachus and drove another general far away out of his kingdom. After defeating first Lysimachus, the king of the Macedonians, and then Antiochus the son of Seleucus, the king of Asia, he founded a city under Mount (?) Lyparus, which was named after himself. Zipoetes lived for 76 years and ruled the kingdom for 48 years; he was survived by four children. He was succeeded by the eldest of the children, Nicomedes, who acted not like a brother but like an executioner to his brothers. However he strengthened the kingdom of the Bithynians, particularly by arranging for the Gauls to cross over to Asia, and as was said before, he founded the city which bears his name."

Memnon, History of Heracleia, chapter 12. At Attalus.

I have replaced "Doedalsus" in the text with "Dydalsos" (Δυδαλσος) as it appears in the Greek text: Memnon, History of Heracleia, chapter 12 in Greek. At Attalus.

8. Thracian Bithynians

Herodotus wrote that the Thracian Thynians and Bithynians living in Anatolia (Asia Minor) were among the peoples subjugated by the Lydian king Croesus (Histories, Book 1, chapter 28). In 547 BC the Persian king Cyrus conquered Croesus' empire, and from around 514 BC much of European Thrace was also subjected by the Persian kings (see History of Stageira Part 4). The historian also described the clothing and arms of the Thracians in the army of King Xerxes that invaded Greece in 480 BC.

"The Thracians in the army wore fox-skin caps on their heads, and tunics on their bodies; over these they wore embroidered mantles; they had shoes of fawnskin on their feet and legs; they also had javelins and little shields and daggers. They took the name of Bithynians after they crossed over to Asia; before that they were called (as they themselves say) Strymonians, since they lived by the Strymon; they say that they were driven from their homes by Teucrians and Mysians. The commander of the Thracians of Asia was Bassaces son of Artabanus."

Herodotus, Histories, Book 7, chapter 75. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Strymon River flows through Bulgaria and the Central Macedonia region of northern Greece, passing Amphipolis and emptying into the Strymonic Gulf, east of Halkidiki (see map of Macedonia and the North Aegean Sea).

9. William Ouseley in Bithynia

The inscribed stone and Ouseley's claim for it appear to have been forgotten, and I have so far found no information about its current location.

William Ouseley, Travels in various countries of the East, more particularly Persia ... 1810, 1811, 1812, Volume 3, pages 512-513. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1823. At Googlebooks.

Ouseley's letter to The Classical Journal and his drawing of the Arrian inscription were published in:

The Classical Journal, No. XXXII, Volume 16, September and December 1817, page 394. A. J. Valpay, London, 1817. At Googlebooks.

10. Théodore Reinach on Doidalsas and the Crouching Aphrodite

The French scholar Théodore Reinach (1860-1928) was a real polymath, having practised as a historian, archaeologist, papyrologist, philologist, epigrapher, numismatist, musicologist, mathematician, professor, lawyer and politician. He was the younger brother of the archaeologist Salomon Reinach (1858-1932).

Théodore Reinach, L'auteur de la Vénus accroupie (The author of the Crouching Venus). In: La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1897, pages 314-324. 478e Livraison, 3e Période, Tome Dix-Septième, 1er Avril 1897. PDF at Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France, gallica.bnf.fr.

11. Doidalsas in museum guide books

From the official guide book to the Herakleion Archaeological Museum, Crete:

"Along the northern side of the Gallery [Gallery XX] are some extremely important sculptures from Gortys, many of them copies, e.g. a naked torso of a youth (No. 343) which is a copy of the Doryphoros by Polykleitos, a statue of Aphrodite kneeling in her bath (No.43), a copy of a work by Doidalsas, and a statue of Athena Parthenos (No. 347), a copy of a work by Pheidias."

J. A. Sakellaris (Director of the Herakleion Museum and Associate Professor of Archaeological at the University of Athens), Illustrated guide to Herakleion Museum, page 143. Ekdotike Editions, Athens, 1985 (© 1978).

From the official guide book to the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome:

"Doidalsas's Aphrodite". Caption to a photo of the Crouching Aphrodite from Hadrian's Villa, page 36.

page 36, First Floor, Room V:

"Several works come from Hadrian's Villa ... above all the copy, unfortunately lacking its arms, of the squatting Aphrodite by the 3rd-century-BC Bithynian sculptor Doidalsas."

page 37, First Floor, Room VII:

"Images of Apollo, nude and dressed as a cithara player, Artemis, armed with a quiver, Dionysus, Athena, Pan, Venus (another copy after Doidalsas) and two copies of Lysippus's Eros the Archer show the popularity of the Olympic pantheon in the decoration of villas."

Matteo Cadario and Nunzio Giustozzi, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Guide. Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Muzeo Nazionale Romano e l'Area Archeologica di Roma. Mondadori Electa S.p.A., Milan, 2016 (first edition 2012).

12. Doidalsas as pupil of Lysippos and court sculptor

See: Doidalsas or Daedalus, at the Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. |

|

|

13. Nikomedes and Aphrodite of Knidos

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 7, chapter 39, and Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny did not say which King Nikomedes of Bithynia was meant, but Nikomedes I (ruled circa 280-255 BC) is often assumed. Nikomedes IV has also been suggested.

Rulers of Bithynia (dates approximate):

Dynasts

Doidalsos, legendary founder (see above); circa 435 BC ?

Boteiras died 376 BC

Bas 376-326 BC

Zipoetes I 326-278 BC, proclaimed first king (basileus) of Bithynia in 297 BC

Kings

Zipoetes II 278-276 BC

Nicomedes I 278-255 BC

Etazeta (regent) 255-254 BC

Ziaelas 254-228 BC

Prusias I Choloss 228-182 BC

Prusias II Cynegos 182-149 BC

Nicomedes II Epiphanes 149-127 BC

Nicomedes III Euergetes 127-94 BC

Nicomedes IV Philopator 94-74 BC

Socrates Chrestus, ruled briefly, around 90 BC

Under the Roman Empire, Nikomedeia became the capital of the province of Bithynia. |

|

A silver tetradrachm of King Nicomedes II

Epiphanes of Bithynia (ruled 149-127 BC).

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

|

14. Eugenie Sellers on Doidalsas and the Crouching Aphrodite

Katherine Jex-Blake and Eugenie Sellers, The elder Pliny's chapters on the history of art, page 208, and Addenda to page 208 on page 239. Translation by K. Jex-Blake, with commentary and historical introduction by E. Sellers and additional notes contributed by Dr. Heinrich Ludwig Urlichs. Macmillan & Co., London, 1896.

15. Andreas Linfert on Doidalsas and the Crouching Aphrodite

Andreas Linfert, Der Meister der Kauernden Aphrodite (The master of the Crouching Aphrodite). In: Mitteilungen der deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, athenische Abteilung 84 (1969), pages 158-164.

16. Jane Francis on the Crouching Aphrodite

Jane Francis, The Roman Crouching Aphrodite. Mouseion, XLVI - Series III, Volume 2, 2002, No. 2, pages 211-244. At academia.edu.

17. Leonard Barkan on Doidalsas as philological coinage

"Although some scholars remain true to the idea that there was a Doidalsas who sculpted the Crouching Aphrodite (e.g. Storia naturale, 5.585), the suggestion that he is simply a philological coinage, which seems to originate with Andreas Linfert (Der Meister der Kauernden Aphrodite)."

Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the past: Archaeology and aesthetics in the making of Renaissance culture, page 371, note 58. Yale University Press, 1999. At Googlebooks.

18. Antonio Corso on Doidalsas doubters

Antonio Corso, The art of Praxiteles II: The mature years, note 176, page 246. L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2004.

19. The Marsyas Painter and the Painter of Athens 1472

See: Sue Allen Hoyt, Masters, pupils and multiple images in Greek red-figure vase painting. Dissertation, Ohio State University, 2006. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|