|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Thrace > Alexandroupoli |

| Alexandroupoli, Greece |

History of Alexandroupoli |

|

|

page 2 |

|

|

| |

Statue of Domna Vizvizi, heroine of the Greek War of Independence, in Alexandroupoli (see below). |

| |

|

| |

| A brief history of Alexandroupoli |

| |

Alexandroupoli is located on the Aeaean coast of the geographical region of northeastern Greece known as Thrace, which represents just a small part of the ancient Thracian territories (see A brief history of Thrace).

The area lies on the ancient land and sea routes between Greece, the Balkans, Asia and the Black Sea. For the people who lived on the Thracian coast these routes brought the advantages of commercial and cultural contacts, but also the dangers of attacks by competing cities, foreign invaders and pirates. |

History of

Alexandroupoli |

Ancient Sale |

|

The modern city of Alexandroupoli stands on the site of the ancient Greek city of Sale (Σάλη; also referred to as Sala), which was founded as a colony of the island of Samothraki in the Archaic period. It appears that Sale never played a significant part in historical events and therefore its name seldom appears in the works of ancient authors.

Thorough archaeological exploration of the site is now impossible because it has been built over, but a number of inscriptions, architectural members and tombs have been discovered. |

|

|

| |

The symbol of

East Macedonia

and Thrace |

| |

The Greek historian Herodotus mentioned Sale as a city bulit by the Samothrakians when describing how the Persian king Xerxes I gathered his army and ships at nearby Doriskos (Δορίσκος) in 480 BC to evaluate the size of his enormous invasion force before his unsuccessful attempt to conquer Greece. The discovery of an ancient inscription on a boundary stone marking the territory of Samothraki near Alexandroupoli appears to confirm Herodotus' remarks. He also wrote that the area along the coast originally belonged to a Thracian tribe known as the Kikones (Κίκονες). [1]

Thrace and Macedonia had been under Persian control since its conquest by Xerxes' predecessor Darius I in 514-513 BC. (see History of Stageira and Olympiada Part 4), and it took several years after the the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) before the Greeks drove the last Persian forces from the European mainland. In 477 BC Athens and its allies formed the confederacy now known as the Delian League with the object of protecting Greek cities from the Persians, and Sale became a member, paying an annual tribute.

During the 4th century BC the Macedonians became the dominant power in Greece and Thrace due to the military victories and politcal cunning of Philip II and his son Alexander the Great. Following Alexander's death in 336 BC his successors fought several wars against each other for the control of parts of his vast empire, and Lysimachus was the first of several Hellenistic rulers who styled themselves king of Thrace. However they mostly controlled only coastal areas which were often under threat of Thracian tribes in the hinterland.

Much of the Thracian coast and several Aegean islands, including Samothraki, came under the control of the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt until the territories were seized by Philip V of Macedonia between 204 and 200 BC.

The constant warring among the various Hellenistic kingdoms made it relatively easy for Rome to increase its influence and power in the Eastern Mediterranean from the late third century BC.

At the end of the Second Macedonian War, following the Battle of Kynoskephalai in 197 BC, the Romans issued a general declaration of "freedom" of Greek cities which had been under Macedonian control in 196 BC. The Thracian cities were conquered by the Seleucid king Antiochus III in 194 BC, but following his defeat by the Romans at Magnesia in 190 BC, they were once again declared free.

Sale's larger neighbouring city Maroneia (Μαρώνεια, originally a colony of Chios, founded in the 7th century BC) became autonomous and the dominant local city on this stretch of the Thracian coast, controlling the strategically important military and trade routes. According to the Roman author Livy, by 188 BC Sale was a village belonging to Maroneia and the location of a Roman military camp. [2]

The area was again occupied by Philip V in 188/187 BC, during the Third Macedonian War. Local inhabitants were massacred following their appeal to Rome for help, however, Philip was forced to withdraw his forces in 185/184 BC.

Having defeated the Macedonians and Seleucids, and inherited the territories of Pergamon from Attalus III (see History of Pergamon), the Romans now controlled Greece, Macedonia, Thrace and Anatolia (Asia Minor). Following a period of autonomy, Thrace was made a Roman province (Romana provincia Thracia) in 46 AD, during the reign of Claudius.

Sale became a road-station (mutatio) along the section of the Roman Via Egnatia between Philippi and Traianopolis. However, at some point it was either destroyed or abandoned, the fate of several other ancient settlements in the area. |

|

A silver tetradrachm coin from Maroneia,

Thrace, with a depiction of a male figure,

believed to be Dionysus, holding a bunch

of grapes (see Dionysus). 89-45 BC.

Münzkabinett, Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. |

| |

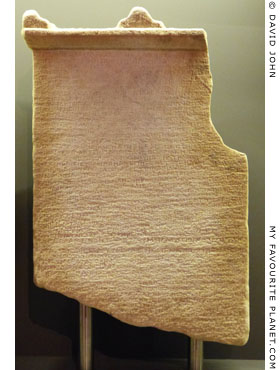

Part of a stele of Thasian marble,

inscribed with a decree of the people

of Maroneia issued in order to secure

their freedom and autonomy. 41-42 AD

or 46 AD, during the reign of Emperor

Claudius. Found in Samothraki. [3]

Samothraki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 88.594. |

| |

| |

History of

Alexandroupoli |

Ottoman Dedeagach |

|

|

|

Not much is known about the place between the Roman period and the mid 19th century, except that it appears to have been a landing place for local fishermen and people from Samothraki.

The later Eastern Roman Empire (known today as the Byzantine Empire) became Christian, and Thrace and Macedonia were invaded by several foreign forces, including Serbian and Bulgarian Slavs. By the mid 15th century the Muslim Ottoman Turks finally conquered the Byzantine territories and went on to expand their empire through the Balkans and into central Europe. Various ethnic groups settled (or were settled by the Ottomans) in the region, including Albanians, Bulgarians, Turks and Jews from Hungary and the Iberian Peninsula. |

|

|

| |

Monument to Domna and Hadji Antonis Vizvizi, heroes

of the Greek War of Independence, in Alexandroupoli. [4]

|

At the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821 people of several settlements in Thrace, including Ainos (Enez), Samothraki and Maroneia, rebelled but the Turks brutally suppressed the uprisings. On Samothraki alone 1,000 inhabitants were massacred. The Greek populations of Thrace were too small, isolated and ill-equipped to continue the war here, and while much of the southern mainland and several islands formed the new Greek state, Macedonia and Thrace were to remain part of the Ottoman Empire for almost a century.

By 1860 there was a small fishing village here known as Dedeagach (Greek, Δεδεαγάτς; Turkish, Dedeağaç). According to legend it was named after a tree (Turkish, ağaç) under which a wise old Dervish (dede, grandfather) lived and was later buried. One theory is that the Dervish may have been from the monastery (tekke) of the Bektashi Order (Bektaşi) at the Baths of Traianopolis. Presumably, the tree and the dede's grave have long since disappeared.

Travellers who visited the area in the 19th century reported that it was marshy, malarial and lacked drinking water, and that travel on the Thracian Sea was dangerous.

In the mid 19th century the Ottoman government decided to build railways connecting Constantinople (Istanbul) and Thessaloniki with Vienna, in an ambitious attempt to modernize the ailing empire and improve trade with Europe. The new railway of the Chemins de fer Orientaux would also enable the Turkish military to move troops and supplies more speedily. Dedeagach was to be an important station on this new rail network and the plan included the building of a port for the shipping of grain, tobacco and timber.

Construction of the branch line to connect with the main line from Constantinople to Edirne (Adrianople) and on through the Balkans to Austria began at Dedeagach in 1871, and was completed in 1873. It took a lot longer to build the port, and although another branch line was built at the same time from Thessaloniki northwards to Serbia, the line connecting Thessaloniki and Edrine, via Serres, Drama, Xanthi, Komotini and Dedeagach, was not completed until 1896.

The building of the railway and port brought workers to Dedeagach, and as it grew into a town it also attracted merchants and businesses. The new settlers included Greeks, Turks and Armenians, the latter being among the first to build their own church here (see page 5: sights in Alexandroupoli).

Russia was one of the European powers which encouraged nationalism in the Balkan lands of the Ottoman Empire, mostly to advance its own geopolitical ambitions, and there were several conflicts between the forces of the Russian tsars and the Turkish sultans. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 the Russians captured Dedeagach, and although they were only able to hold onto it for a short time they initiated several improvements in the town, including the laying out of streets using the grid system which can still be seen today.

The terms of peace with Russia, laid down in treaties thrashed out at a number of international conferences among the Great Powers, meant that Turkey had to give up much of its territory, including Bulgaria, but Dedeagach and Western Thrace returned to Ottoman control.

Dedeagach continued to grow and prosper, facilities at the port were gradually improved and the lighthouse was built in 1880 by a French company. In 1884 the town was made the capital of the new province, the Sanjak of Dedeagach (part of the larger province, the Vilayet of Edirne), replacing the Sanjak of Dimetoka centred at the ancient city of Didymoteicho which had been strategically and symbolically important for the Ottomans since they conquered it in 1359.

Administrative offices and foreign consulates were established in the new local capital, including delegations from Russia and Greece. This meant the building of new offices and houses, and more work for the craftsmen and labourers who built them. Increasing exports of local products such as tobacco, timber and silk also added to the prosperity of the town.

Meanwhile nationalist tensions continued to increase throughout the Ottoman Empire as various ethnic groups struggled for independence. The main actors in the Balkans lands still controlled by the Turks (then known as Turkey in Europe) were Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro. During the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, Greek forces attempted to capture Macedonia but were defeated by the Turkish army. A decisive factor in the Turkish victory was their abilty to move troops quickly by rail. The war was a disaster for Greece which was forced to cede even more territory and pay reparations.

During the First Balkan War of 1912-1913, the Balkan League (Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro) gained considerable territories from Turkey. Bulgaria claimed Western Thrace and occupied Dedeagach in 1912. However, the Balkan League members quickly fell out among themselves over claims to the captured lands, particularly Macedonia and Thrace, which led to the Second Balkan War of 1913 between the former allies.

In August 1913 Greek and Ottoman forces captured Western Thrace from Bulgaria, and in a curious case of cooperation between the two arch-enemies, they declared the Provisional Government of Western Thrace (later known as the Independent Government of Western Thrace) as an independent republic of Turks, Greeks and Pomaks, with its capital at Gümülcine (Komotini). The great powers refused to recognize the government and by October the area was handed back to Bulgaria. |

|

Bust of Domna Vizvizi in Alexandroupoli. |

|

| |

History of

Alexandroupoli |

Modern Alexandroupoli |

|

|

|

Alexandroupoli post office, where Western Thrace

officially became part of Greece on 14th May 1920. [5]

|

The Balkan crises were a major factor leading to World War I (1914-1918), and while Bulgaria sided with the Central Powers, Germany, Austria and Turkey, Greece finally entered the conflict on the side of the Allies, Britain, France and Russia. As a result of further international conferences, in 1919 the Bulgarians were forced to leave Western Thrace which became a French protectorate, and in 1920 part of the Greece.

The official handover of Western Thrace from France to Greece took place in the post office of Dedeagach on 14th May 1920. King Alexander of Greece (1893-1920, ruled 1917-1920) visited the city on 9th July, and shortly after it was renamed Alexandroupoli (City of Alexander) in his honour.

At the time of his visit, Alexander was on his way to join the Greek army's attack on Edirne. The Greeks were determined to take Eastern Thrace, including Constantinople, from Turkey, as part of their "Megali Idea" (Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Great Idea), the dream of reuniting Greek populations living throughout the old Byzantine territories. This dream soon turned into a nightmare when Greek forces embarked on a disastrous military campain in western Anatolia in 1919, sparking off the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) which ended with the Greeks - soldiers and civilians - being driven into the Aegean Sea at Smyrna (Izmir) by the Turkish army in 1922.

Whatever claims to moral justification Greece may have had for military expansionism, the dream ended at Smyrna. The Great Powers had enough of war and were now facing their own enormous political and economic problems nearer to home; and the leader of the new Turkish Republic, Atatürk, stood firm and refused to cede more Turkish territory.

The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, fixed Greece's borders [6], and Western Thrace remained part of the nation, despite continuing claims and objections by Bulgaria. However the treaty also required an enormous exchange of Christian and Muslim populations between Greece and Turkey.

The civilian populations of all the ethnic groups caught up in the Balkan wars had suffered persecution, massacres, dispossession and forced expulsion at the hands of the various armies. Now Muslims in Greece were forced to move to Turkey and many Christians in Turkey had to go to Greece. There were exceptions, including many of the minority Muslims in Western Thrace, such as the Pomaks. However, the loss of Turks living in Greece and the influx of enormous numbers of ethnic Greeks from Turkey caused severe political, economic and social problems for the fledgling Greek state, to say nothing of the terrible personal tragedies caused by the uprooting of people whose families had lived in towns and villages for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Alexandroupoli and the other settlements of Western Thrace took in many thousands of refugees, and all inhabitants would now share in the fate of Greece, which over the coming decades would include invasion by fascist Germany, Italy and Bulgaria, famine, dictatorships and civil war.

In World War II Bulgaria once again attacked Macedonia and Thrace, and occupied Alexandroupoli from 1941 to 1944. During the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), the Communist forces were dominant in Macedonia and Thrace, but were eventually defeated by the US-backed right-wing army. Many of the left-wing fled into exile, including tens of thousands of children who were sent for safety to Eastern European countries.

During the 1980s Greece returned to democracy and became a member of the European Union. Life has definitely improved throughout the country, despite the present economic crisis which continues to have an enormous adverse effect on the lives of working and middle class people. The more isolated areas such as Thrace suffer most, since they do not have the income from tourism enjoyed by Athens and some of the resorts and islands in the south of the country. East Macedonia and Thrace remains primarily an agricultural region and must compete on the global market to sell its products. Many young people are forced to leave the area in search of work.

Having said all that, as we can see from this brief history, the Thracians are strong and tough, and have seen much worse times. Somehow, most manage to keep smiling and getting on with life. They deserve a brighter future. God knows, they have already paid for it several times over.

See also: A brief history of Thrace |

|

|

| |

History of

Alexandroupoli |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Herodotus on Doriskos and Sale

"The territory of Doriscus is in Thrace, a wide plain by the sea, and through it flows a great river, the Hebrus; here had been built that royal fortress which is called Doriscus, and a Persian guard had been posted there by Darius ever since the time of his march against Scythia [513-512 BC]. It seemed to Xerxes to be a fit place for him to arrange and number his army, and he did so. All the ships had now arrived at Doriscus, and the captains at Xerxes' command brought them to the beach near Doriscus, where stands the Samothracian city of Sale, and Zone; at the end is Serreum, a well-known headland. This country was in former days possessed by the Cicones. To this beach they brought in their ships and hauled them up for rest. Meanwhile Xerxes made a reckoning of his forces at Doriscus."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 7, chapter 59. English translation by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1920. At Perseus Digital Library.

Unfortunately, in this edition Sale has been incorrectly rendered as "Sane", perhaps a confusion with the Andrian colony in east Halkidiki (see History of Stageira and Olympiada Part 2) which is also mentioned by Herodotus in Book 7, chapters 22-23. The name is given correctly in the Greek text:

"... Ξέρξεω ἐς τὸν αἰγιαλὸν τὸν προσεχέα Δορίσκῳ ἐκόμισαν, ἐν τῷ Σάλη τε Σαμοθρηικίη πεπόλισται πόλις καὶ Ζώνη, τελευτᾷ δὲ αὐτοῦ ..."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 7, chapter 59. At Perseus Digital Library.

See also:

The History of Herodotus Volume II (of 2), translated by G. C. Macaulay. At Project Gutenberg.

For further information about Herodotus, see Herodotus in the My Favourite Planet People section.

2. Livy on Sale

Titus Livius Patavinus (64 or 59 BC – 17 AD), usually referred to as Livy, was a Roman historian whose only surviving work is Ab Urbe Condita Libri (Books from the foundation of the city), also known as Ab Urbe Condita (History of Rome). The mention of Sale appears in Book 38, chapter 41, section 8, in which Roman soldiers marching through Thrace camped at the village after fighting off an ambush by Thracians.

The History of Rome by Titus Livius, Books 37 to the End. Translated by William A. McDevitte. Henry G. Bohn, London, 1850. At Project Gutenberg.

Livy, From the Founding of the City, Book 38, chapter 41, section 8. Translated by Rev. Canon Roberts, 1905. At Wikisource.

See also:

Edith Schönert-Geiss (editor), Griechisches Münzwerk: die Münzprägungen von Maroneia, pages 1-2. Schriften zur Geschichte und Kultur der Antike, Nummer 26. Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1987.

3. A decree of Maroneia found on Samothraki

The stele of Thasian marble was discovered in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothraki on 3 August 1988, during excavations on the Western Hill, among Byzantine remains at the 3rd century BC Ship Monument building (the "Neorion"). When, how and why it was taken to the island from Maroneia is unknown.

Samothraki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 88.594.

Inscription SEG 53 659 (= AE 2003, 1559).

Height 68.8 cm (including moulding),

60.4 cm (inscribed surface);

width 44.0 cm (at line 44);

Height of letters, 0.7 - 1.2 cm.

See:

Kevin Clinton, Maroneia and Rome: Two decrees of Maroneia from Samothrace. Chiron (Mitteilungen der Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts), Band 33, 2003, pages 379-417. Verlag C. H. Beck, München.

Kevin Clinton, Maroneia and Rome: Two decrees of Maroneia from Samothrace: Further thoughts. Chiron, Band 34, 2004, pages 145-148. Verlag C. H. Beck, München.

Text of the inscription in Greek:

epigraphy.packhum.org/text/326426 at The Packard Humanities Institute. |

|

|

4. Domna and Hadji Antonis Vizvizi

The Monument to Hadji Antonis and Domna Vizvizi, is a bronze sculpture group made by Georgios Megfkoulas (Γιώργος Μέγφκουλας) in 1987. The work is rather melodramatic, and unfortunately has recently been gilded.

The monument, flanked by the busts of Domna Vizvizi and her son Themistocles-Timoleon Visvizis stand on a square named after them, near the Alexandroupoli Lighthouse, on the seafront promenade Odos Vasileos Alexandrou.

Hadji Antonis Vizvizi (Χατζή Αντώνη Βισβίζη, died 1822) was a Greek shipowner and captain from Ainos (Αίνος; today Enez, Turkey), a Thracian port east of the mouth of the River Evros. In 1808 he married Domna Vizvizi (Δόμνα Βισβίζη, 1783-1850) who was from a local landowning family.

The couple became members of the Filiki Eteria (Φιλική Εταιρεία, Society of Friends), a secret society dedicated to creating a Greek state independent of Ottoman Turkey.

In April 1821, at the beginning of the Greek War of Independence, the Greeks of Ainos occupied the town's castle after overwhelming the Turkish troops stationed there. The Turks recaptured the town, but the Psara squadron of the Greek navy arrived on 2nd May and the Greeks regained the upper hand. However, after a few days the Turks once again took Ainos, and many of its inhabitants escaped to join the independence struggle.

The Vizvizis took their five children and all their possessions aboard their ship Kalomira (Καλομοίρα), with 16 cannons and a crew of 140, and set off to join the Greek navy. After taking part in several battles, Hadji Antonis was killed aboard the Kalomira on 21st July 1822 during the siege of Euboea. Domna Vizvizi immediately took command of the ship and went on to take part in further naval actions in the Aegean and become a heroine of the war.

Domna continued fighting until 1824, when she was forced to withdraw from action due to lack of funds. She handed her ship over to the Greek navy which used it as a fireship to destroy the Turkish frigate Chazne Gkemnisi in the same year.

The heroine, now penniless, took her five children to live first on Hydra, then Syros and Nafplion. During the hardships that followed one of her children died of hunger. She wrote to the Greek government pleading for assistance, but received none. In 1829 she was finally granted a small pension by the head of state Ioannis Kapodistrias, but died in poverty and obscurity in 1850 at Piraeus, forgotten by the nation she had sacrificed so much to help create.

One of the couple's sons, Themistocles-Timoleon Visvizis (Θεμιστοκλής-Τιμολέων Βισβίζης) was more fortunate. He was taken to study in Paris by the Philhellenic Komitat of Paris, along with children of Constantine Kanaris and other Greek independence heroes. The handsome young man was treated as a star by Parisian society, and lithographic prints of his portrait were sold for large sums to raise money for the Greek cause. On his return to Greece in 1832 he gained an appointment at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and was the Governor of Naxos 1845-1876.

See also the story of the naval Battle of Samos

in 1824 on Samos gallery page 13. |

| |

Bust of Themistocles Vizvizi by the

Athenian sculptor George Dimitriadis

(1880-1941) in Alexandroupoli. |

| |

Modern bust of Constantine Kanaris

(circa 1795-1877), Greek admiral,

and hero of the Greek War of

Independence. Near the Vizvizi

monument, Alexandroupoli. |

| |

5. The post office of Alexandroupoli

I have not yet discovered the history of the building itself, except that it was built "at the beginning of the 20th century". The French postal service issued postage stamps at several places in the Ottoman Empire (including Constantinople from 1812-1827 and 1835-1914), and at Dedeagach from January 1874 to August 1914, and it may have also built the post office here. During World War I the Bulgarians used their own postage stamps, and it is doubtful that they built this post office. Since it was the location of the handover of Western Thrace from the French protectorate to Greece in 1920, it was presumably built before 1914.

6. Greece's borders

There were several exceptions and anomalies in the case of Greece's borders. For example, the Dodecanese islands were taken by Italy in 1912, and only became part of the Greek state after World War II. See A brief history of Kastellorizo. |

|

|

Photos, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this website.

However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes

made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|