|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Kresilas |

|

| |

Kresilas

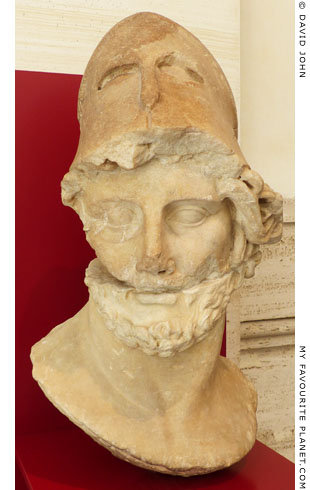

Kresilas (Κρησίλας; Latin, Cresilas; also referred to as Ctesilas or Ctesilaüs; circa 480-410 BC), was a Greek sculptor from Kydonia (Κυδωνία, today Chania), on the north coast of Crete, working on mainland Greece in the mid to late 5th century BC, during the High Classical period.

He is thought to have been a student of Dorotheos of Argos (Δωρόθεος), and may have worked with him at Delphi and at Hermione in the eastern Peloponnese. This theory is mainly based on the discovery of signatures of the two artists on the bases of related statues at both places (see Kresilas signatures below). From literary and epigraphical evidence, he appears to have worked between around 450 and 410 BC mainly in Athens, probably as a follower of the school of Myron, known for its idealistic portraiture.

Five statue bases inscribed with the signature of Kresilas have so far been discovered: three on the Athens Acropolis, one at Delphi and one at Hermione. Another signed base found at Pergamon may belong to a copy of one of his works. See Kresilas signatures below.

Kydonia was colonized by Aegina in 515 BC, and since the lettering on some of the statue bases is thought to be in the Aeginetan alphabet, it has been suggested that Kresilas was from a family of Aeginetan origin [1].

Pliny the Elder mentioned a bronze statue of a dying man and a portrait of the Athenian general and statesman Pericles (Περικλῆς, circa 495-429 BC) by "Ctesilaüs", thought to be an error and meant to refer to Cresilas (Kresilas). He does not tell us where these sculptures originally stood, nor where they were to be found in his time, although he appears to be claiming to have seen them himself.

"Cresilas executed a statue of a man fainting from his wounds, in the expression of which may be seen how little life remains; as also the Olympian Pericles, well worthy of its title: indeed, it is one of the marvellous adjuncts of this art, that it renders men who are already celebrated even more so."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

Later in the same chapter he stated, "Desilaüs made a Doryphoros [spear carrier] and a wounded Amazon". This is also thought to be an error for Kresilas. The names Ctesilaüs and Desilaüs are otherwise unknown.

Pausanias twice mentioned a statue of Pericles on the Athens Acropolis. It is not clear whether he was writing about one or two separate statues. He did not describe the statue (or statues) or name the sculptor(s).

"On the Athenian Acropolis is a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and one of Xanthippus himself, who fought against the Persians at the naval battle of Mycale. But that of Pericles stands apart, while near Xanthippos stands Anacreon of Teos..."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 25, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

"In addition to the works I have mentioned ... There are two other offerings, a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and the best worth seeing of the works of Pheidias, the statue of Athena called Lemnian after those who dedicated it."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 28, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

Plutarch wrote that several artists had made portraits of Pericles.

"His personal appearance was unimpeachable, except that his head was rather long and out of due proportion. For this reason the images of him, almost all of them, wear helmets, because the artists, as it would seem, were not willing to reproach him with deformity."

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Pericles, chapter 3, section 2. At LacusCurtius.

Despite Plutarch's testimony, it has been assumed by some modern writers that Pliny's portrait of Pericles by Kresilas was the same as the statue on the Acropolis mentioned by Pausanias. If Pliny had seen the statue himself, it was either in Athens or had been taken to Italy (perhaps Rome), in which case the portrait Pausanias saw in Athens around a century later was a copy or a work by a different sculptor.

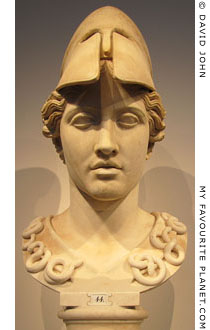

Nevertheless, it is thought that extant marble busts and heads, identified as portraits of Pericles wearing a Corinthian helmet perched on top of his head, are Roman period copies of a bronze statue made by Kresilas around 440-430 BC. The first three of these were found around Rome between 1779 and 1780:

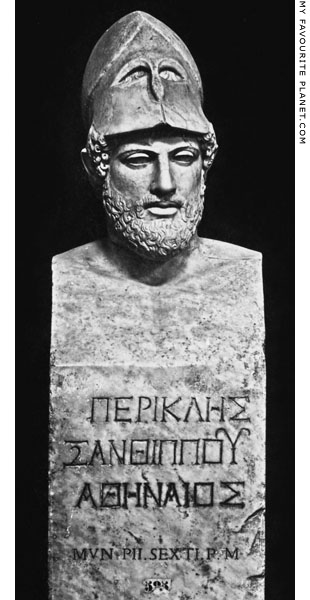

A marble herm bust bearing the inscription ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ ΞΑΝΘΙΠΠΟΥ ΑΘΗΝΑΙΟΣ (Pericles, son of Xanthippos, Athenian), found in 1779 during excavations financed by Pope Pius VI (1775-1799) at the "Villa Tiburtina of Cassius" (Pianella di Cassio or Praedium Cassianum), Tivoli, near Rome. Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 269 (see photo, above right).

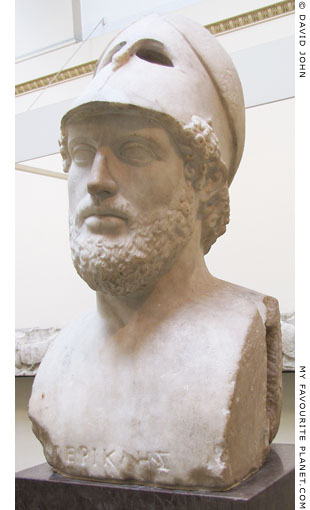

"The Townley Pericles" (see photo, above right), a marble herm bust, inscribed ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ (Pericles). 2nd century AD. Height 58.42 cm. Also found at the "Villa Tiburtina of Cassius", Tivoli, in 1779. British Museum, London. Inv. No. GR 1805.7-3.91 (Sculpture 549, Inscription 1097). [3]

The third, not so well sculpted bust is in the Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums.

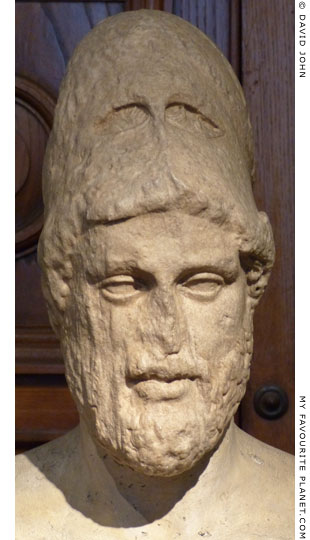

Also a badly damaged head of Pericles made of Pentelic marble, restored as a herm bust, in the Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 96 (see photo, below right). From the Alexandre Castellani Collection.

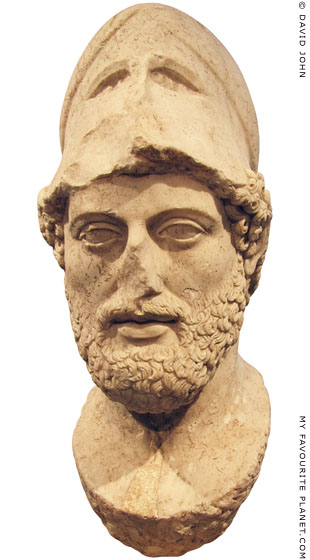

A marble head of Pericles from a statue, found on Lesbos (see photo, below right). Pentelic marble. Height 53 cm. Purchased in 1901 by an anonymous "friend of the museum" from Dr. Kjellberg in Upsala for 6000 marks. Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1530 (K 127). [4]

According to Pliny (Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19), Kresilas made a bronze statue of an Amazon for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus for which he was awarded third place in a competition with his contemporaries Pheidias, Polykleitos, Kydon and Phradmon.

"The most celebrated of these artists, though born at different epochs, have joined in a trial of skill in the Amazons which they have respectively made. When these statues were dedicated in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, it was agreed, in order to ascertain which was the best, that it should be left to the judgment of the artists themselves who were then present: upon which, it was evident that that was the best, which all the artists agreed in considering as the next best to his own. Accordingly, the first rank was assigned to Polycletus, the second to Phidias, the third to Cresilas, the fourth to Cydon, and the fifth to Phradmon."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

The mention of "Cydon" after "Cresilas" is thought to be an error made either by Pliny or a manuscript copyist, and have originally referred to Kresilas of Kydonia. One or more of the Amazon statues resulting from this contest may have been models for several extant copies of the "Wounded Amazon" type [5]. Some scholars have doubted that such a competition ever took place.

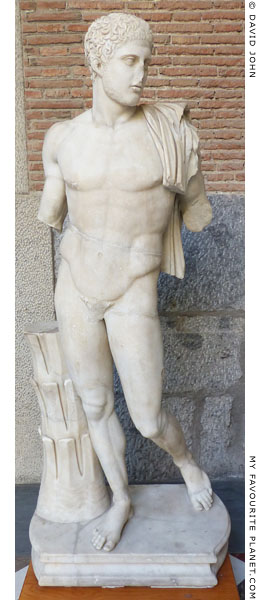

Having attributed the heads of Pericles to Kresilas, scholars since the 19th century, particularly the German archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler [6], have seen sufficient similarities in Roman period statues of the Homeric hero Diomedes (see photo below right) and those of the "Athena Velletri" type, as well as a portrait of an athlete, to ascribe them to the same artist. There is no literary evidence for these conjectures, which have been refuted by several scholars. The "Athena Velletri" type has also been attributed to Alkamenes on equally uncertain grounds. [7]

A bronze statue by a sculptor named Kresilas is mentioned in a fragment of a poem by the ancient Greek epigrammatic poet Poseidippos of Pella (Ποσείδιππος, circa 310-240 BC). The fragment, from the collection of epigrams known as the Milan Papyrus [8], praises his statue of the Homeric hero Idomeneus:

"Unhesitatingly praise that bronze Idoneneus

of Kresilas. How precisely he made it, we saw well.

Idomeneus cries: 'Good Meriones, run!

... having been long immobile'."

Milan papyrus, AB 64 (X 26-29).

Idomeneus (Ἰδομενεύς) was a king of Crete and grandson of Minos, who led the Cretan armies to the Trojan War ( Homer, The Iliad, Book 2, line 645). Meriones (Μηριόνης) was his half-brother and charioteer. The Cretan associations have strengthened speculation that the sculptor mentioned is Kresilas of Kydonia. |

Marble herm of Pericles wearing a Corinthian

helmet. Inscribed on the front of the shaft:

ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ

ΞΑΝΘΙΠΠΟΥ

ΑΘHΝΑΙΟΣ

Pericles, son of Xanthippus, Athenian.

2nd century AD. Found in 1779 during

excavations financed by Pope Pius VI at

the "Villa of Cassius", Tivoli, near Rome.

Restored in 1780 by Guiseppe Pierantoni.

Height 183 cm.

Sale delle Muse (Hall of the Muses),

Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums,

Rome. Inv. No. 269. [2] |

| |

"The Townley Pericles", a marble bust

of Pericles wearing a Corinthian helmet.

The front of the bust is inscribed:

ΠΕΡΙΚΛΗΣ

Perikles

The herm is broken off just below the

inscription, which may have been longer.

2nd century AD. Found at Tivoli in 1781.

Height 58.42 cm.

British Museum, London.

Inv. No. GR 1805.7-3.91 (Sculpture 549).

From the Townley Collection. |

| |

Marble head of Pericles wearing a

Corinthian helmet, on a modern bust.

2nd century AD. Pentelic marble.

Height 63 cm.

Barracco Museum, Rome. Inv. No. MB 96.

Acquired 1884 from the Castellani collection. |

| |

Marble portrait head of Pericles wearing

a Corinthian helmet, made for a statue.

Found on Lesbos, acquired on the

art market in 1901. Height 53 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 1530 (K 127). |

| |

A marble statue of a naked young man,

thought to be a copy of a statue of the

Homeric hero Diomedes made by

Kresilas around 450-430 BC.

Found at Cumae in the Bay of Naples,

Campania, Italy.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 144978. |

| |

| |

| Kresilas |

Kresilas signatures |

|

|

|

The dates of the statue bases from Athens, Hermione and Delphi associated with Kresilas are uncertain and continue to be debated, but they are generally thought to be from around 450-400 BC.

Although the bases have been mentioned in several publications, most authors have discussed the inscriptions rather than the bases as objects. Some of the standard works dealing with the inscriptions [9] provide varying data, such as the dates of the finds and sizes. The current locations of the inscriptions are rarely mentioned. |

|

Acropolis, Athens

Delphi

Hermione, Peloponnese

Pergamon |

|

|

| Three bases of bronze statues found on the Athens Acropolis are inscribed with the signature of Kresilas. All are apparently in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens, although according to some sources, two are (or were) in the Acropolis Museum. A large number of objects from the Acropolis were kept for many years in the National Archaeological Museum and the Epigraphical Museum, but since 2007 many have been moved to the New Acropolis Museum. |

|

|

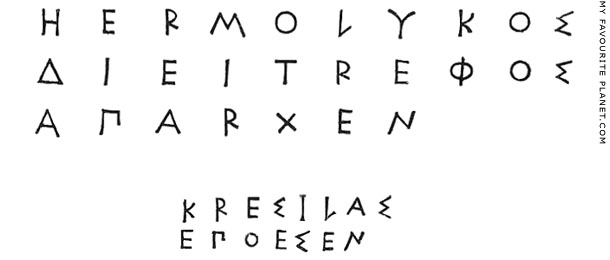

| 1. Dedication by Hermolykos, son of Dieitrephes |

|

|

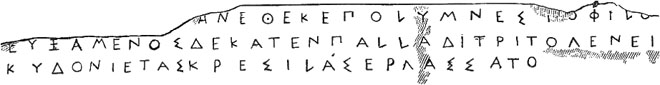

A drawing of the dedication by Hermolykos, son of Dieitrephes,

and the signature of Kresilas inscribed on a marble base of a

bronze statue. Found on the Athens Acropolis in 1839.

Acropolis Museum. Inv. Akr. 13201. Inscription IG I(3) 883.

Source: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer, No. 46, pages 36-37.

B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

A square base of Pentelic marble, discovered on 3 April 1839, built into the wall of a cistern between the Propylaia and the Parthenon.

Ηερμόλυκος

Διειτρέφος

ἀπαρχέν.

Κρεσίλας

ἐπόεσεν.

Hermolykos, Dieitrephos aparchen.

Kresilas epoeson.

Hermolykos, son of Dieitrephes, dedicated it.

Kresilas made it.

Acropolis Museum. Inv. Akr. 13201.

Inscription IG I(3) 883 (also IG I(2) 527; DAA 132).

Height 48 cm, length 70 cm, depth 76 cm.

This may have been the statue of the Athenian general, "Diitrephes shot through with arrows", reported by Pausanias as standing near entrance to the Acropolis:

"Hard by is a bronze statue of Diitrephes shot through by arrows. Among the acts reported of this Diitrephes by the Athenians is his leading back home the Thracian mercenaries who arrived too late to take part in the expedition of Demosthenes against Syracuse. He also put into the Chalcidic Euripus, where the Boeotians had an inland town Mycalessus, marched up to this town from the coast and took it. Of the inhabitants the Thracians put to the sword not only the combatants but also the women and children."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

Since Pausanias could not have discovered the identity of the man portrayed from the inscription on the base, it has beeen suggested that his name may have been written on the statue itself, as in the case of the name Apollo inscribed on the thigh of a statue by Myron and on the inscription on the Archaic "Nikandre Kore". His usual informants were local guides, whose tales he often treated with scepticism.

Diitrephes (Διιτρέφης) and his part the sacking and massacres at Boeotian cities in 413 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, was recorded by Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 7, chapters 29-30). Pausanias' description is so close to the text of Thucydides that this must have been his source.

Following the discovery of the base, scholars believed the inscription was made too early to be for a statue of this Diitrephes. Elsewhere, Thucydides mentioned a "Nikostratos, son of Diitrephes" (Book 3, chapter 75) and the father was assumed to have been an earlier prominent Athenian of this name who would have thus fitted the dating of the base. If this was the same Diitrephes he may have been the father of both Nikostratos and Hermolykos. Thucydides also mentions a Diotrephes (Book 8, chapter 64) and a "Nikostratos, son of Diotrephes" (4.53, 4.119, 4.129), and this Diotrephes (Διοτρέφης) is thought to have been a different person. He does not mention the death of Diitrephes, and only Pausanias wrote that he was killed by arrows, but did not say when or where. More recently it has been suggested that the statue may have been made much later than previously supposed. [10]

This statue may also have been the "man fainting from his wounds" by Kresilas mentioned by Pliny the Elder (see above).

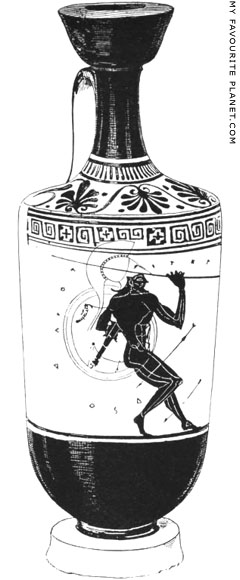

An Attic white-ground lekythos of the same period (around 475-425 BC), has a painting of a warrior pierced by two arrows (see image, right). It has been conjectured that it may represent the death of Diitrephes.

See: Adolf Furtwängler, Masterpieces of Greek sculpture, page 124 [see note 6]. |

Drawing of the top of the

Hermolykos base fragment

with two cuttings.

Source: Same as the drawing

of the inscription above. |

| |

An Attic white-ground lekythos

with a painting of a warrior

pierced by two arrows, one

through the right thigh and

the other in the left shin.

The inscriptions are nonsense.

Around 475-425 BC. Attributed

to the Athena Painter. From

Vulci, Etruria, Italy. Height

19.7 cm, diameter 7 cm.

Cabinet des Medailles, Paris.

Source: Adolf Furtwängler, Masterpieces of Greek

sculpture [see note 6]. |

| |

|

A fragment of a statue base inscribed with the signature of Kresilas, found on

the Athens Acropolis in 1888. Perhaps from a statue of Pericles. Circa 430 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6258. Inscription IG I(3) 884.

Source: Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz, Über ein Bildnis des Perikles

in den königlichen Museen, page 16. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1901. |

| |

A small fragment of a base of Pentelic marble was found in 1888 (or 1889), built into the South Wall of Acropolis, near Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia. The left part of the inscribed dedication and artist's signature are missing. It has been suggested that it may be the base of the statue of Pericles by Kresilas (or "Ctesilaüs") mentioned by Pliny the Elder, although many scholars have found the identification unconvincing.

[- - -] ικλέος.

[Κρεσ]ίλας ἐποίε.

[- - -] ikleos.

[Kres]ilas epoie.

[- - -] ikleos.

[Kres]ilas made it.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6258.

Inscription IG I(3) 884 (also IG I(2) 528; DAA 131,b).

Height 18 cm, length 28 cm, depth 12.5 cm.

The epigraphist Antony Eric Raubitschek [see note 9] suggested that another fragment, which had been found before 1840, may have belonged to the same base [11]. However, this theory has been rejected by a number of scholars. Raubitschek also suggested that the inscription could be restored as:

[Per]ikleos

[Kres]ilas epoie (or epoie[se]) |

|

|

| 3. Dedication by Pyres, son of Polymnestos |

|

|

A drawing of the dedication by Pyres, son of Polymnestos, to Pallas Athena

Tritogeneia and the signature of Kresilas inscribed on a marble base of a

bronze statue. Around 440 BC. Found on the Athens Acropolis.

Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. 6978. Inscription IG I(3) 885.

Source: Emanuel Loewy, Inschriften griechischer Bildhauer, No. 47, pages 37-38.

B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1885. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

A fragment of a Pentelic marble statue base with part of an inscription, was found in 1872, built into the top northern side of the west door of the Parthenon. The fragment was removed with the doorway in 1926-1927, when the Parthenon was cleared of Medieval additions.

The inscription is a metrical votive dedication by [Pyre]s, son of Polymnestos, to Pallas Athena Tritogeneia (Τριτογένεια). It was restored according to an ancient epigram (Palatine Anthology XIII,13 = J. Overbeck, Schriftq., No. 876).

[τόνδε Πυρε͂]ς ἀνέθεκε Πολυμνέστ̣ο φίλο[ς ℎυιὸς]

εὐξάμενος δεκάτεν Παλλάδι τριτο̣γενεῖ.

Κυδονιέτας Κρεσίλας ἐργάσσατο.

This [statue] was dedicated for a tithe by Polymnestus' dear son Pyres,

as he had vowed, to Pallas Tritogeneia.

Kydonian Kresilas made it.

Acropolis Museum. Inv. No. 6978.

Inscription IG I(3) 885 (also IG I(2) 529; DAA 133).

Height 27 cm, length 73 cm, depth 84 cm.

|

|

|

| |

|

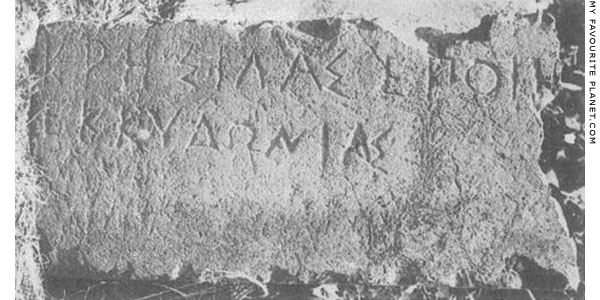

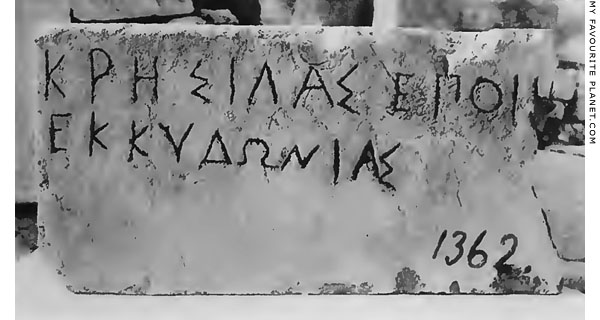

The signature of Kresilas inscribed on a fragment of a dark

limestone statue base, from the sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1362. Inscription FD III 4:194.

Source: Jean Marcadé, Recueil des signatures des sculpteurs grecs, Volume 1 (of 2), No. I,62,

plate XI, 2. l'École Française d'Athènes. Librairie E. de Boccard, Paris, 1953. At Cefael, online

collections of l'École Française d'Athènes. The name of the photographer and date are not given. |

| |

An inscription in the Ionic alphabet on a fragment of a dark limestone base, dated around 500-450 BC, was found in Delphi in May 1894, among the debris to the west of the Temple of Apollo (4th century BC).

Κρησίλας ἐποίη̣[σε]

ἐκ Κυδωνίας

Kresilas epoie[se]

ek Kydonias

Kresilas made it

from Kydonia

Inscription FD III 4:194

Delphi Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1362.

Height 30.5 cm, length 60 cm, maximum depth 45 cm.

See: Émile Bourguet (editor), Fouilles de Delphes, Tome III, Épigraphie. Fascicule 1, Inscriptions de l'entrée du sanctuaire au trésor des Athéniens. No. 502, pages 326-328. E. De Boccard, Paris, 1929. |

|

|

| |

Another early photo of the signature of Kresilas in Delphi. An archaeologist has painted

the inventory number on the front of the limestone block, beneath the inscription.

Source: Théophile Homolle, Fouilles de Delphes, Tome III, Fascicule 4,

planche 29, 3. No. 194. Text on pages 258-259. École française d'Athènes.

E. De Boccard, Paris, 1930. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

|

A large, rectangular limestone base of a bronze statue dedicated by Alexias, son of Lyon, to Demeter Chthonia (Χθωνία, of the earth) at Hermione (Ἑρμιόνη) at the southern tip of the Argolid peninsula, northeastern Peloponnese, Greece. [see note 1]

Ἀλεξίας : Λύονος : ἀνέθε[κε]

τᾶι Δάματρι : τᾶι

[Χ]θονία[ι]

ℎερμιονεύς.

Κρεσίλας : ἐποίεσε : Κυδονιάτα[ς]

Alexias Lyonos anetheke

Tai Damatri tai Xthoniai

Hermioneys

Kresilas epoiese Kydonata[s]

Alexias, son of Lyon, dedicated

to Demeter Chthonia

of Hermione.

Kresilas of Kydonia made it.

Inscription IG IV 683

"Kresilas" has also been read as "Kresidas".

Height 32 cm, width 73 cm, length 202 cm.

This inscription was first recorded by the French priest and antiquarian Abbé Michel Fourmont during his his visit to Greece in 1729-1730 (see Aristion of Paros). It was one of four bases dedicated to Demeter Chthonia found built into a Venetian wall across a headland at the south of the modern town. The base believed to be the earliest is signed by Dorotheos of Argos (IG IV 684), thought to have been Kresilas' teacher. Another is signed jointly by Polykles (perhaps the sculptor mentioned by Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 34, chapter 50; flourished 372-268 BC) and Androkydes of Argos.

The cuttings in the top of the bases suggest that the statues were of animals, and horses or equestrian figures were at first suggested. However, the prevailing theory is that the statues were of cows, based on the description by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 35, sections 4-8) of the annual summer procession by the Hermionians to the sanctuary of Demeter Chthonia outside the city, and the sacrifice of fully-grown cows there. Four cows were shut inside the temple, one by one, along with four old women appointed to kill them: "Whichever gets the chance cuts the throat of the cow with a sickle." The only statues Pausanias mentions seeing at the sanctuary are those of priestesses of Demeter in front of the temple, and inside it "images, of no great age, of Athena and Demeter".

See: Jean Marcadé, Recueil des signatures des sculpteurs grecs, Volume 1 (of 2), No. I, 63, plate XI, 4. l'École Française d'Athènes. Librairie E. de Boccard, Paris, 1953. At Cefael, online collections of l'École Française d'Athènes. |

|

|

| |

|

A fragment of a base for what is thought to have been a small statue (or statuette), found in 1906 on the terrace of the Upper Gymnasium on the Pergamon acropolis, is inscribed ΚΡΗΣΙΛΑΣ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΝ (Kresilas made it). However the style the lettering is that of the Hellenistic period. The statue may have supported an original statue by Kresilas, moved to Pergamon and set up on a new base, or a copy (or even a fake) made for the Attalid royal collection, or a work by a later artist of the same name.

Κρησίλ[ας ἐπόίησεν]

Height 3.1 cm, length 6.5 cm, letter height 0.8 cm.

See: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung, Band 33, No. 60, page 418. Beck und Barth, Athens, 1908. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

| |

| Kresilas |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

|

1. Kresilas and the Aeginetan alphabet

See:

Michael Jameson, Inscriptions of the Peloponnesos, Hesperia, Volume 22, No. 3 (July - September 1953), pages 148-171. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org.

Jameson discusses five inscriptions from Hermione that he and his wife examined in the winter and spring of 1950, while members of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Among them were the four inscribed statue bases associated with the sanctuary of Demeter Chthonia (see above), including the two signed by Dorotheos and Kresilas. He concluded that the lettering of signatures by Kresilas is Aeginetan, and pointed out that the known 5th century BC inscriptions of Kydonia are also written in the Aeginetan alphabet, "in marked contrast to the characteristic Cretan forms of other Cretan cities".

2. Pericles herm in the Museo Pio-Clementino

The photo, taken in 1859 by the British photographer James Anderson (1813-1877), has been cropped to show the only the top half of the herm.

Below the Greek inscription and the modern Latin inscription on the front of the shaft is a label with the original Vatican Museum invoice number 525.

3. "The Townley Pericles"

Museum label: "Roman, 2nd century AD copy of a lost original of around 440-430 BC"

The bust is in the form of a "terminus", i.e. the top part of a herm. Terminus was the Roman god who protected boundaries, and stone pillars known in Latin as terminii were set up as boundary markers in a similar way to which herms were used by the Greeks. Such busts of gods and famous humans were made for the private collections of wealthy people.

This bust was purchased in 1783 by the Scottish painter, antiquarian, archaeologist and antiquities dealer Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798) for the private collection of the wealthy English gentleman Charles Townley (1737-1805). It was acquired by the British Museum, along with around 300 ancient artefacts of the Townley Collection, after his death.

The "official" accounts of the date and location of the discovery of this herm and that in the Museo Pio-Clementino are based on the version of events related by Ennio Quirino Visconti (1751-1818), Italian antiquarian, art historian and papal Prefect of Antiquities, in his Museo Pio-Clementino, published in various editions from 1782. They have been brought into question by the examination of a number of contemporary and later documents, and it appears that both herms, as well as a number of other antuques, were actually discovered in April 1779 in an olive grove of the De Matthias family, the site of a Roman Republican villa arbitrarily known as the "Villa of Cassius" (believed to have belonged to Gaius Cassius Longinus), "Pianella di Carciano" and "la Pianella di Cassio". This site has apparently been confused with that of the nearby "Villa of Brutus", which some sources claim as the findspot of "The Townley Pericles".

Other sculptures from the "Villa of Cassius", found in 1774, include marble statues of of Apoolo Musagetes (or Apollo Kitharoidos) and eight Muses, all of which are also in Sale delle Muse of the Museo Pio-Clementino.

See:

Beth Cohen, Perikles' Portrait and the Riace Bronzes: New Evidence for "Schinocephaly". In: Hesperia, Volume 60, No. 4 (October - December 1991), pages 465-502 and plates 113-126. Particularly Appendix: Circumstances of the discovery of the inscribed Perikles herms, pages 500-502. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), 1991. PDF at ascsa.edu.gr.

4. The Pericles head in Berlin

In a monograph written in 1901, shortly after the head was donated to the Berlin museum, Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz reported that it had been acquired in Lesbos. He added that he had been unable to discover further information about its provenance except that it was donated by a "friend of the museum" who wished to remain anonymous.

See: Reinhard Kekule von Stradonitz, Über ein Bildnis des Perikles in den königlichen Museen. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1901. |

|

Marble head of a Greek strategos

(general) wearing a Corinthian helmet.

2nd century AD, Roman period. Pentelic

marble. Thought to be a copy of a bronze

portrait of an Athenian general of the

Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC).

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National

Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 74037. |

|

5. Extant Amazon statues

The English archaeologist Ernest Arthur Gardner (1862-1939) identified three types of Amazon statues.

"Among statues of Amazons, of which many are preserved in our museums, there are some which clearly show the style of the fifth century. To omit minor variations or later modifications, there are three main types:

1. An Amazon, leaning with her left elbow on a pillar, her right hand resting on her head her chiton is fastened only on the right shoulder, leaving her left breast bare; on her right breast, just outside the edge of the drapery, is a wound.

2. The Capitoline type – An Amazon, with her right arm raised, leaning, probably on a spear her head is bent down, her chiton is fastened on the left shoulder, it has been unfastened from her right by her left hand, which still holds the drapery at her waist, so as to keep it clear of a wound below the right breast; there is another wound above it; she wears also a chlamys.

3. The so-called Mattei type representing not a wounded Amazon, but one using her spear as a jumping-pole to mount her horse ; it is on her left side, and she grasps it with both hands, her right passing a cross over her head. Her chiton is fastened on the right shoulder, leaving the left breast bare, and it is curiously drawn up below so as to expose the left thigh."

Ernest Arthur Gardner, A Handbook of Greek Sculpture, Part II, pages 332-336. Macmillan and Co., London, 1897. At the Internet Archive. |

|

Marble statue of a

wounded Amazon.

Found in Rome. Thought to

be a copy of a statue made

for the Temple of Artemis,

Ephesus around 440-430 BC,

perhaps by Polykleitos.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 7.

A relief of a wounded Amazon

in this pose, part of a marble

frieze (circa 350 BC) from the

altar of Artemis, is in the

Ephesus Museum, Selçuk.

Inv. No. I 811. Height 65 cm. |

|

| |

6. Adolf Furtwängler on Kresilas

See: Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907), Masterpieces of Greek sculpture: A series of essays on the history of art. English translation edited by Eugénie Sellers. William Heinemann, London, 1895. At the Internet Archive.

Furtwängler's section on Kresilas and Myron, pages 113-220.

The drawing of the lekythos with the warrior wounded by arrows, Fig. 48, page 124.

7. Diomedes and Athena Velletri type statues

Two of the best examples of the Diomedes type, now in Naples (see photo above) and Munich, were found at Cumae in the Bay of Naples, Campania, Italy. The marble statues are thought to have originally depicted Diomedes stealing the Palladion, the statue of Pallas Athena from the temple of the goddess in Troy (see Homer part 2).

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 144978.

Glyptothek, Munich. Inv. No. 304.

The 23 known statues and heads of the Athena Velletri type are named after first example, found in 1797 in the ruins of a Roman villa near Velletri, Lazio, central Italy. Now in the Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. MA 464 (MR 281). Not on display. |

|

Marble head of Athena

of the Velletri type.

Roman copy of a Greek original,

circa 390-380 BC, or perhaps

of a bronze by Kresilas, circa

430 BC. The bust of this

restored head is modern.

Altes Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 79. |

|

| |

8. The Milan Papyrus

The Milan Papyrus, officially referred to as P. Mil. Vogl VIII 309, dated to the late 3rd - early 2nd century BC, contains over 606 verses from 112 epigrams, all but two of which were previously unknown, and all or most thought to be by Poseidippos of Pella. Discovered by grave robbers in Egypt, among the wrappings of a mummy dated to around 180 BC, the papyrus was purchased in Europe in 1992 by the University of Milan. It was first published in 2001.

See:

Mary Frances Williams, The New Posidippus: Realism in Hellenistic sculpture, Lysippus, and Aristotle’s aesthetic theory (P. Mil. Vogl. VIII.309, Pos. X.7-XI.19 Bastianini = 62-70 AB). Leeds International Classical Studies 4.02 (2005). The epigram on the statue by Kresilas is discussed on pages 15-17.

Posidippus, Epigrams, Pap. Mil. Vogl. VIII 309. Two different translations of AB 64 (X 26-29), under Andriantopoiika (On Statues). At the Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington DC.

9. Greek and Roman inscriptions - standard references

Most ancient Greek and Roman inscriptions are given reference numbers, such as IG IV 683, FD III 4:194, CIG 1194, DAA 132. The first letters and numerals usually indicate the title and volume of an academic book or journal in which they were published, often where their discovery was first announced or where they were first examined and discussed by a particular scholar. Many inscriptions have been discussed several times, their content reappraised and new attempts made to decipher, translate and interpret them. These are therefore referred to by several different reference numbers, the sources of which often provide very different information.

As is often the case in archaeology and ancient history, information provided by debate, fresh viewpoints and research, as well as new discoveries renders many older articles and opinions obsolete. On the other hand, after much discussion on a particular subject, older ideas are sometimes rediscovered or rehabilitated. Discovering, accessing and keeping abreast of the plethora of articles published on such specialist subjects is an enormous task.

A number of institutions and groups are attempting to put ever more information concerning inscriptions online, including original texts, translations and commentaries. At present the most comprehensive source for original texts is the website of the Packard Humanities Institute:

The Packard Humanities Institute, Los Altos, California. Its website contains searchable databases of Greek and Latin inscriptions and classical Latin Texts.

epigraphy.packhum.org

Classical Latin Texts: latin.packhum.org

For some other resources, see the growing bibliography in the Ancient Greek artists section.

In the case of the inscriptions associated with Kresilas, the reference works most often cited are:

DAA, the common abbreviation for Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis: A catalogue of the inscriptions of the sixth and fifth centuries (BC), a definitive reference work by the US-Austrian epigraphist and classical historian Antony Eric Raubitschek (1912-1999).

Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis: A catalogue of the inscriptions of the sixth and fifth centuries. Archaeological Institute of America, Cambridge, Mass., 1949.

The French hellenist historian Jean Marcadé (1920-2012) wrote a standard work on the signatures of ancient Greek sculptors, which provides short descriptions of all the known signatures of Kresilas:

Jean Marcadé, Recueil des signatures des sculpteurs grecs, Volume 1 (of 2). In French. Illustrated with drawings and photos of inscriptions and squeezes. l'École Française d'Athènes. Librairie E. de Boccard, Paris, 1953. At Cefael, online collections of l'École Française d'Athènes.

10. The Hermolykos base

The discovery of the base was first reported by the Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis (Κυριάκος Πιττάκης, 1798-1863) in Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1938, No. 81. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία. (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens).

See:

Jean Marcadé, Recueil des signatures des sculpteurs grecs, Volume 1 (of 2), No. I,62 (with a photo of a squeeze). l'École Française d'Athènes. Librairie E. de Boccard, Paris, 1953. At Cefael, online collections of l'École Française d'Athènes.

Catherine M. Keesling, The Hermolykos/Kresilas base and the date of Kresilas of Kydonia. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Band 147, pages 79-91. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 2004. At jstor.org.

Keesling examined the Kresilas signatures in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens, and reappraised the available evidence concerning the dates of the sculptor's career.

11. Raubitschek's fragment

Found before 1840, findspot unknown.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 6362.

Height 25 cm, length 40 cm, depth 30 cm.

Raubitschek referred to the fragment as "fragment a", and to EM 6258 as "fragment b".

See:

Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis, pages 139-141.

Jean Marcadé, Recueil des signatures des sculpteurs grecs, Volume 1 (of 2), No. I, 63, plate XI, 3. l'École Française d'Athènes. Librairie E. de Boccard, Paris, 1953. At Cefael, online collections of l'École Française d'Athènes. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|