|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

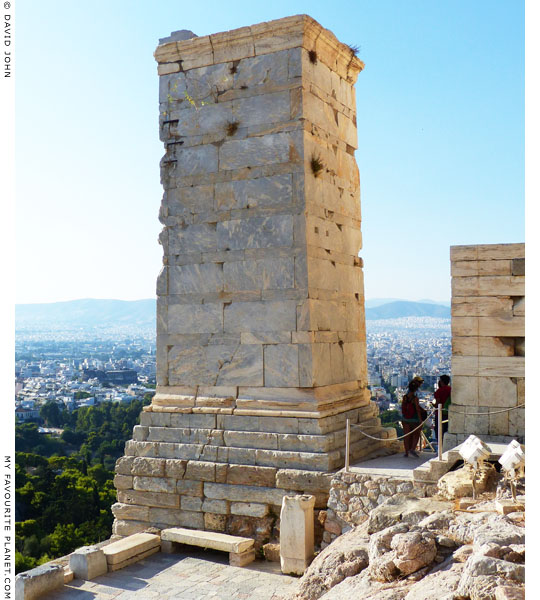

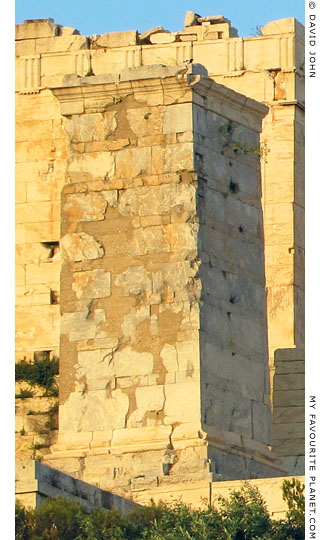

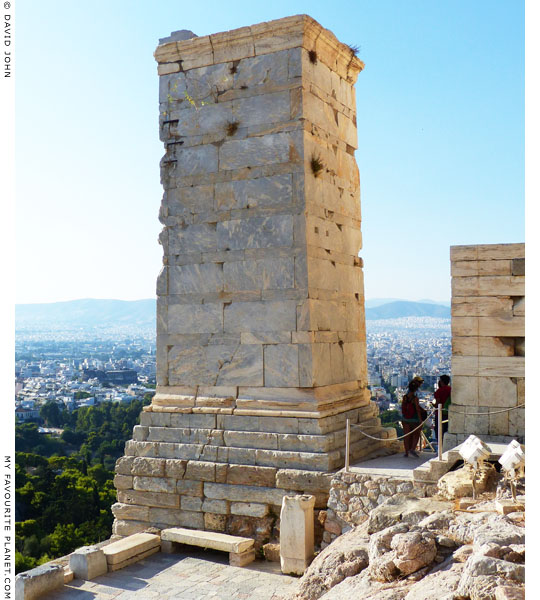

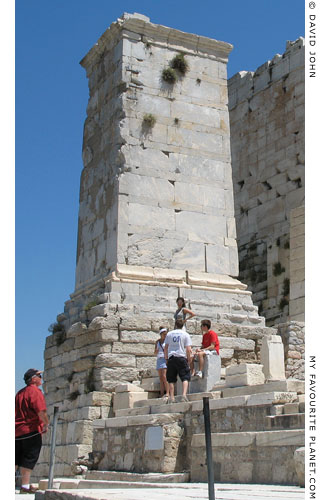

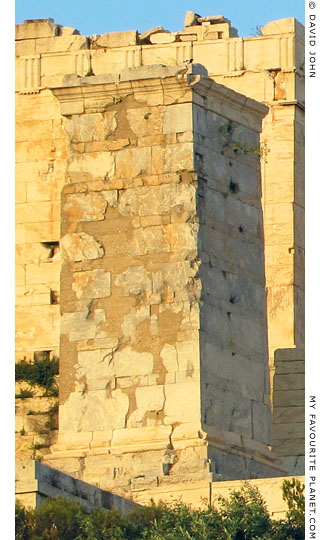

The Pedestal of Agrippa (left) in front of the north wing of the Propylaia. |

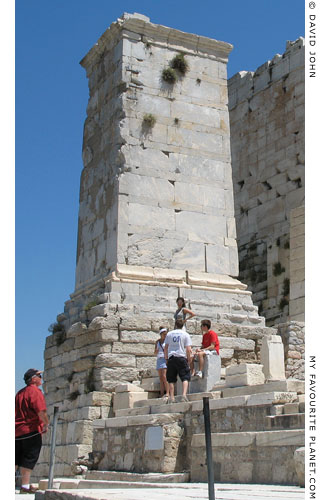

| The Pedestal of Agrippa |

The Pedestal of Agrippa from the southeast, on the stairway up

to the Propylaia. Immediately to the right of the monument is the

stone platform on which the north wing of the Propylaia stands.

See a plan of the entrance to the Acropolis showing

the position of this monument on gallery page 10. |

| |

Since we were unable to find a comprehensive study of this monument's history - which involves some famous Athenians, mythical glimmer twins, chariot races, Antony and Cleoptra and a mischievous ancient travel writer - we thought we would pull together some of the threads of the tale.

The Pedestal of Agrippa stands on a stone platform halfway up the stairway to the Propylaia, directly in front of the monumental gateway's north wing (the "Pinakotheke", see gallery page 10).

This enormous plinth is an obvious feature on the way up to the Acropolis. Of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who pass it by each year, only few stop to wonder at this colossal and mysterious monument, even fewer know what it actually is. There has been very little information published about the pedestal [1], and an information board about it has only recently been set up.

This 8.91 metre tall tapering plinth, with a shaft of blue-grey blocks of marble from Mount Ymittos, tops a 4.5 metre high base of poros limestone blocks, which originally were not visible. [2] It is named after the inscription dedicating the sculpture which stood on top of it to the Roman politician and general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (circa 63-12 BC).

However, the monument is much older and has a curious history, stretching back at least 2,100 years. As with other ancient monuments, the pedestal and other features of this area of the Acropolis have become the subjects of much speculation and several theories concerning their history during the last two centuries of investigations by archaeologists, historians and epigraphists.

One or more statues with various dedications stood on or close to this site in antiquity, referred to by ancient historians either as "chariots" or "horsemen". But whether they were talking about the same statue or successive statues remains a history mystery. The Athenians had a habit of changing the labels on monuments to honour new heroes and rulers. The 19th century historian William Martin Leake called this a "contemptible practice", which he put down to "meanness and base flattery". [3] |

|

| |

| |

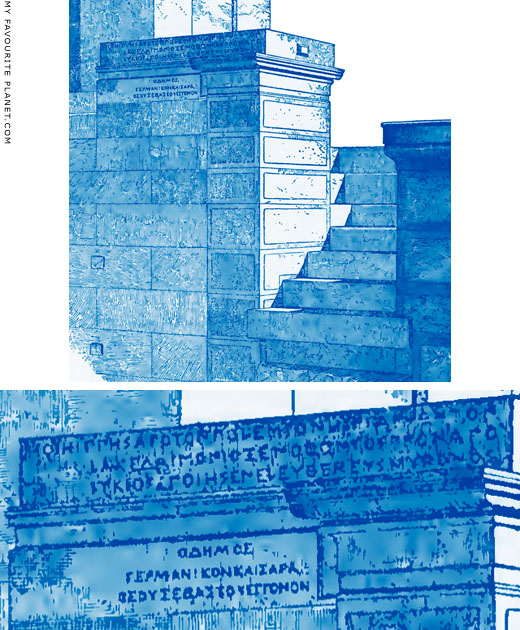

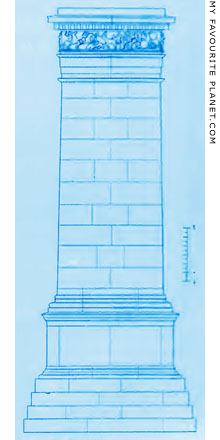

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Classical Athens |

|

|

|

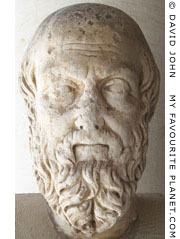

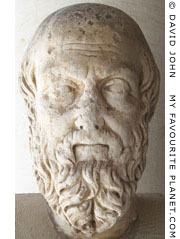

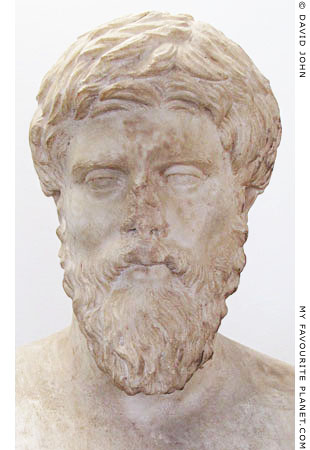

Herodotus, in his Histories, written around 450-425 BC, tells us that a bronze statue of a four-horse chariot (quadriga; Greek, τέθριππον, tethrippon) was erected here to commemorate Athens' military victories over Boeotia and Chalcis (around 506 BC), and that it was paid for with a tenth (tithe) of the ransom demanded for prisoners taken during the battles - two pounds of silver for each hostage.

"The tenth part of the ransom also they dedicated for an offering, and made of it a four-horse chariot of bronze, which stands on the left hand as you enter the Propylaia of the Acropolis, and it bears the inscription:

Athens with Chalcis and Boeotia fought,

Bound them in chains and brought their pride to naught.

Prison was grief, and ransom cost them dear -

One tenth to Pallas raised this chariot here.” [4]

Hardly great poetry - it no doubt loses a lot in translation - but at least an ancient visitor would have known what this statue was about.

Since Herodotus writes that the quadriga was still standing after the plunder and destruction by the Persian army of Xerxes in 480 BC of many monuments on the Acropolis - including the Propylon, the old entrance hall - it must have stood in front of the new Propylaia (built 437-432 BC). This suggests that although the Athenians decided to build this monument after defeating Boeotia and Chalcis, they did not get around to completing it until after they had fought off the Persians and begun to restore the Acropolis. |

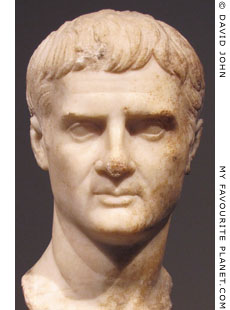

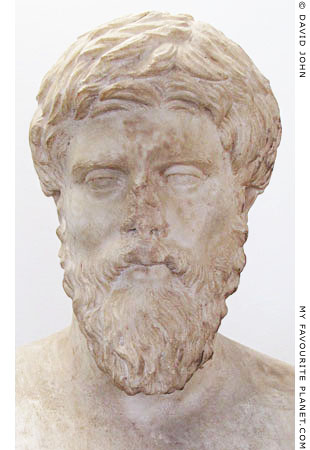

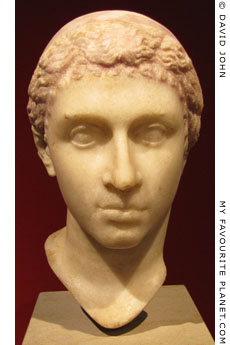

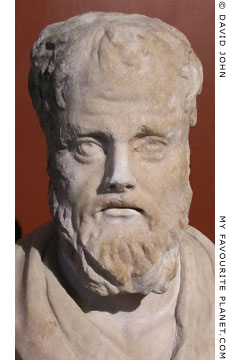

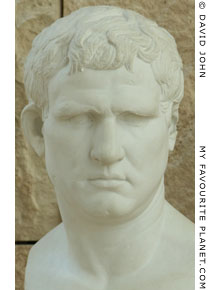

Marble head of Herodotus.

2nd century AD.

Agora Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. S 270. |

| |

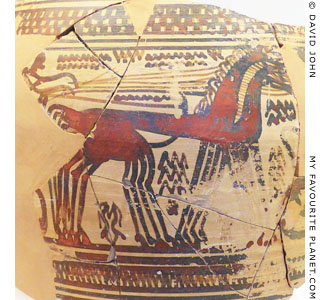

Dekadrachm depicting a quadriga.

Syracuse, Sicily, circa 400-370 BC.

See: Big Money

at The Cheshire Cat Blog. |

| |

| |

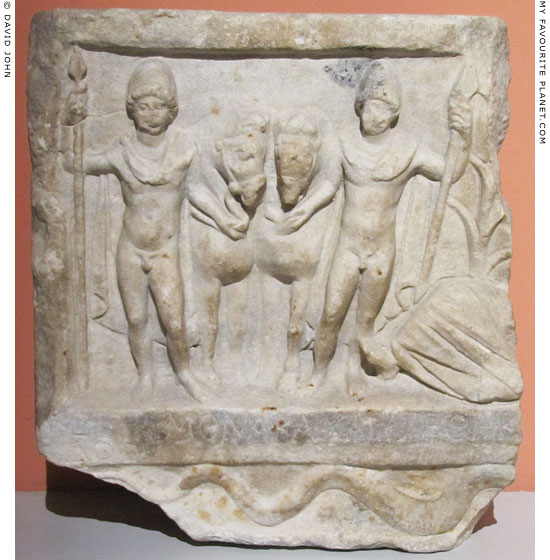

But about 100 years later, it appears that this site was occupied by "horsemen", equestrian statues of Gryllos and Diodoros (Γρύλος καὶ Διόδωρος), the sons of the Athenian-born soldier, historian and philosopher Xenophon (Ξενοφῶν, circa 430-354 BC). They were honoured with the name Dioskouroi (Διόσκουροι, Sons of Zeus) after the heavenly twins Castor and Pollux.

Despite having been exiled by the Athenians, Xenophon sent his sons to fight at the second Battle of Mantinea (Μαντίνεια, in Arcadia, Peloponnese) in 362 BC, at which Athens sided with Sparta against Thebes.

The elder brother Gryllos was killed in action, but the Athenians claimed that he had mortally wounded the Theban general Epaminondas, whose death effectively ended Theban hopes of achieving hegemony in Greece. The Mantineans gave Gryllos a state funeral, erected an equestrian monument above his tomb near their theatre, and placed a large painting of the battle, with him as one of the central figures, in their gymnasium. His bravery was still remembered by the Mantineans when the Greek travel writer Pausanias visited the city around 500 years later.

The painting in Mantinea was a copy of the work by Euphranor, which was displayed in the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios in the Athenian Agora [5]. Many writers, including Isocrates, also wrote speeches and verses praising Gryllos [6].

Not much is known of Diodoros except that he served in the Athenian cavalry at Mantinea, apparently without much distinction, and that he later named a son after his brother (Gryllos was also the name of his paternal grandfather), but he must have achieved fame at least by association with his brother and father.

It has been suggested by some modern historians that the statues of Gryllos and Diodoros were made by Lykios of Eleutherai, son of Myron, based on inscriptions found on the Acropolis, concerning dedications made by Athenian knights (see illustrations and photo below). It has further been suggested that the sculptures originally depicted the mythical Dioskouroi twins [7], and that Pausanias, who mentioned the monument in the 2nd century AD (see the quote from Pausanias below), had merely misread the inscription, understanding it to refer to the sons of Xenophon. [8]

Several equestrian statues of Castor and Pollux are known to have existed in other cities in the ancient world, and a few Roman versions still exist in Italy (see the Dioskouroi page in the MFP People section). There are ancient coins with depictions of the Dioskouroi riding together, which may have been based on such sculptures. For example a coin (photo right) of the Hellenistic Seleucid ruler Antiochus VII Euergetes (ruled 138-129 BC). |

| |

| |

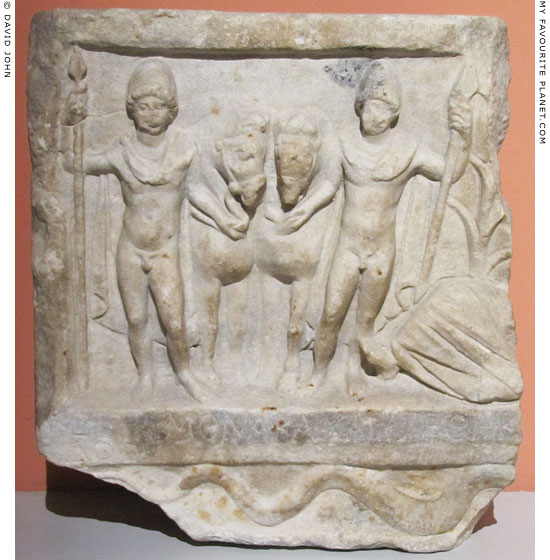

Fragment of an inscribed votive relief of Kastor and Polydeukes, the Dioskouri

with their horses, and part of the reclining local river god Strymon (Στρυμών),

the personification of the River Strymon, which flows though Amphipolis.

From Amphipolis, Thrace, a former Athenian colony. 2nd century AD.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 673. |

| |

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Hellenistic Athens |

|

|

|

An almost obliterated inscription on the plinth proclaimed that a bronze statue of a chariot was erected here in Hellenistic times, dedicated to the victory of King Eumenes II of Pergamon (ruled 197-159 BC) and his brother Attalos (later to become Attalos II Philadelphus) in a chariot race at the Panathenaic Games in 178 BC, one of many they won here. It is thought the plinth now known as "the Pedestal of Agrippa" may have been built at this time.

The kings of Pergamon's Attalid dynasty were great allies and patrons of Athens. Eumenes built the Stoa of Eumenes, a covered walkway between the Theatre of Dionysos, below the South Slope of the Acropolis, and the area where the Odeion of Herodes Atticus was later to be built (around 160-174 AD). Attalus II was to donate the Stoa of Attalus which has now been restored and today is one of the gems of the Ancient Agora, housing the Agora Museum.

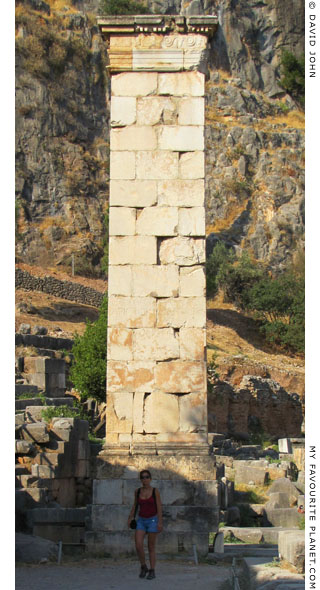

Two similar Hellenistic pedestal monuments once stood in Athens, one at the northeastern corner of the Parthenon and the other in front of of the Stoa of Attalus. Others were built at Delphi, including the Monument of Aemilius Paullus [see note 22], and the Column of Prusias II of Bithynia which can still be seen outside the Temple of Apollo (see photo below).

So what happened to the earlier sculptures? Were they destroyed, or moved elsewhere? Or were the same statues merely rededicated over time? And were references to "horsemen" (see the quote from Pausanias below) errors made when referring to chariots?

Since the statues here were continually associated with two persons (the Dioskouroi or Gryllos and Diodoros, Eumenes and Attalus, and later Antony and Cleopatra, Agrippa and Augustus), the ancient authors seem to be referring to one statue of a two-man racing chariot and/or two statues of horsemen.

Some more recent writers, including Leake and Dr. Richard Chandler, [9] interpreted references by ancient writers Plutarch and Pausanias to mean that originally two statues stood here on matching plinths. Others have also placed these horsemen not on the Pedestal of Agrippa but on two smaller matching plinths either side of the west front of the Propylaia, either immediately before the central colonnade or further forward on the level of the Temple of Athena Nike. These suppositions were reflected in reconstructive images of the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example those by Leo von Klenze (see detail below) and Friedrich M. Thiersch (see illustration on gallery page 10). |

|

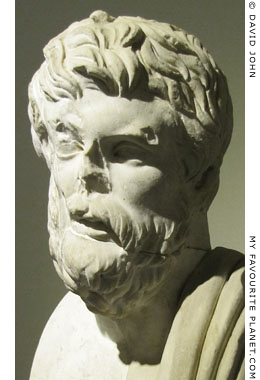

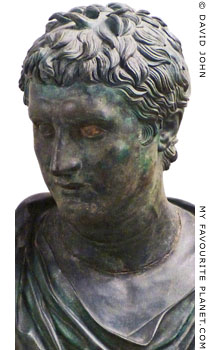

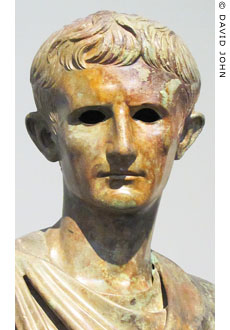

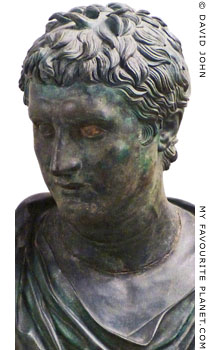

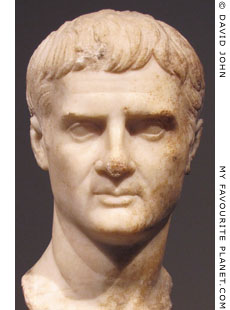

Bronze bust known as

"the Young Commander",

thought to be a portrait of

Eumenes II. Found in the Villa

of the Papyri, Herculaneum.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 5588. |

| |

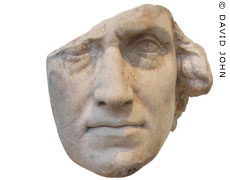

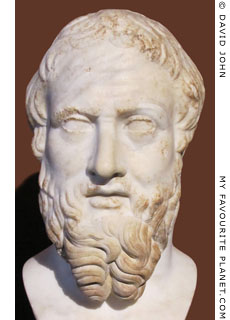

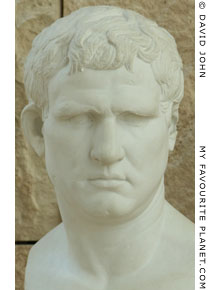

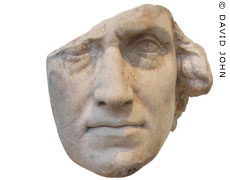

Marble head, dated to the mid

2nd century BC, thought to

depict Attalos II of Pergamon.

Found in the Stoa of Attalos

in the Athens Agora.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3266.

See a larger version of this image

on Pergamon gallery 2, page 5. |

| |

| |

A relief on the marble base of a dedication from the Athens Acropolis depicting competitors

in an apobates race. Circa 400 BC. The apobates was a race of two-man teams in four-horse

chariots in the Panathenaic Games, in which an armed warrior leapt off a moving chariot,

ran alongside it then jumped back on. The composition of the relief has been compared

to that on Block XVII of the Parthenon frieze (Acropolis Museum, Inv. No. Acr. 859).

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. Acr. 1326.

|

The apobates (’ἀποβάτης, dismounter) or apobasia (αποβασία) was a popular event in many ancient Greek cities, and a demanding sport pursued only by the elite [10]. It is probable that the victories of Eumenes and Attalos of Pergamon (see above) were in this event.

According to legend, the four-horse chariot itself was invented in Athens by the mythical serpent-king Erichthonius, who is also said to have founded the Panathenaic festival. [11]

Eusebius of Caesarea wrote that during the 25th Olympic Games in 680 BC, "a race was added for chariots drawn by four horses". [12] |

|

|

| |

"Victorious Apobates". Relief on the base of a monument for the victory of Krates

in the apobates race at the Panathenaic Games. Marble, 4th century BC.

Stoa of Attalus, Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 399. |

| |

Marble Votive relief for a chariot victory from the sanctuary of

the hero Amphiaraus at Oropos, northern Attica, 400-390 BC.

Height 73 cm, width 99 cm, depth 17 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 725. |

| |

Detail from an idealized view of the Acropolis painted in 1846 by

the architect Leo von Klenze (1784-1864). Neue Pinakothek, Munich.

Klenze placed a large statue of a god (Zeus or Poseidon) on the Pedestal of Agrippa,

and an equestrian statue on either side of the central entryway to the Propylaia.

See a photo of the whole painting on gallery page 2. |

| |

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Roman Athens |

|

|

|

Statues of Mark Antony and Cleopatra are said to have later stood here, but were destroyed in 31 BC. However, the Greek historian Plutarch (circa 46-120 AD) wrote that the Athenians merely rededicated the existing statues to their new rulers, and that they were destroyed by a great storm - one of many portentous events he reported as taking place around the Roman Empire when Octavian declared war on Antony and Cleopatra in 31 BC:

"The same tempest fell upon the colossal figures of Eumenes and Attalus at Athens, on which the name of Antony had been inscribed, and prostrated them, and them alone out of many." [13]

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC and the ensuing civil war with Brutus and Cassius, Caesar's successors Mark Antony and Octavian (later to become the first Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus) had effectively divided control of the Roman Empire between them, Antony taking the eastern part which included Greece.

Antony spent considerable time in Athens and was "delighted to be called a Philhellene, and still more to be addressed as Philathenian, and he gave the city very many gifts". [14] Also, he had a large army and was rich and powerful enough to maintain peace in Greece and the eastern Roman Empire. He claimed lineage from Herakles and was dubbed (or dubbed himself) "the New Dionysos"; he certainly seems to have taken full advantage of the wine, theatre, sport and spectacles Athens had on offer. Cleopatra was also made an Athenian citizen, and there was a great exchange of gifts and tributes between the Egyptian queen and the city. So it was not surprising that the Athenians dedicated statues to the couple and sided with them when it came to war against Octavian.

The Roman politician and general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (circa 63-12 BC) was Octavian's close friend and son-in-law (he married Octavian's daughter Julia the Elder), his leading general, and became ostensibly co-ruler of Rome with him. During the power struggle between Octavian and Antony and Cleopatra, Agrippa defeated Mark Antony at the naval Battle of Actium in 31 BC (shortly after the destruction of the sculptures reported by Plutarch). This was the beginning of the end for Antony and Cleopatra, who both fled to Egypt where they committed suicide after their troops had deserted them.

The Athenians no doubt feared reprisals by Octavian for backing his opponents (they had earlier also sided with two of Julius Caesar's assassins, Brutus and Cassius, and of course dedicated statues to them too), and would have considered it expedient to dispose of statues and other tributes to Antony and Cleopatra after their demise. In any case, Octavian moved swiftly to expunge Antony's image from Roman cities:

"But Caesar [Octavian], although vexed at the death of the woman [Cleopatra], admired her lofty spirit; and he gave orders that her body should be buried with that of Antony in splendid and regal fashion... Now, the statues of Antony were torn down, but those of Cleopatra were left standing, because Archibius, one of her friends, gave Caesar two thousand talents, in order that they might not suffer the same fate as Antony's." [15]

Fortunately for Athens, Octavian and Agrippa had a soft spot for the city of Theseus and Pericles, as did most educated Romans, many of whom came here to study philosophy and oratory, wonder at its Classical marvels, and it had become fashionable to pay to be "awarded" Athenian citizenship. Agrippa is said to have interceded for peace with Athens, and Octavian's punishment was relatively mild:

"But from the Athenians he took away Aegina and Eretria, from which they received tribute, because, as some say, they had espoused the cause of Antony; and he furthermore forbade them to make anyone a citizen for money." [16]

Although they can not have been happy about this loss of power, prestige and income, officially the Athenians were grateful to Octavian and Agrippa. Both men visited Athens, on separate occasions, and were greeted with enthusiastic receptions. They too became benefactors of the city. On his visit, around 15 BC, Agrippa commissioned the building of a theatre in the Agora, known as as Odeon of Agrippa or Agrippeion. It appears a cult grew around them here and at other Greek cities. An inscription issued from the Areopagus, found on the sacred island of Delos (which belonged to Athens), praises Agrippa as "benefactor and saviour" (Εὐεργέτης καὶ Σωτὴρ). [17]

Thus, the monument, on a prestigious and highly visible site in front of the Acropolis, which the Athenians passed on their way to religious service, was rededicated to Marcus Agrippa around 27 BC, after his third term as Consul of Rome, and four years after his victory at Actium. The inscription near the top of the pedestal's west side proclaimed:

"The people [dedicated this statue of] Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, thrice consul, their benefactor." [18]

Again, some recent historians have speculated that there was a second, matching statue of Octavian, who, Leake reminds us, "had arrived in that year at such a height of power, that he was made Consul for the seventh time, and was dignified with the title of Augustus".

If Plutarch's sources concerning the destruction of the original statue here were correct, then a new sculpture - or sculptures - must have been erected. Pausanias, writing in the second century AD, appears to be describing equestrian statues when he relates, somewhat enigmatically:

"Now as to the statues of the horsemen, I cannot tell for certain whether they are the sons of Xenophon or whether they were made merely to beautify the place." [19]

Leake, who realized that the masonry of the plinth pre-dated Agrippa and the Roman presence in Greece, conjectured that Pausanias' apparent ignorance of the identity was merely diplomacy, or "that fear of giving offence, which in several instances has caused him to use obscure language, when examples occurred of Roman barbarism, or Greek baseness." Perhaps it was a bit of mischievous Lydian sarcasm on Pausanias' part. |

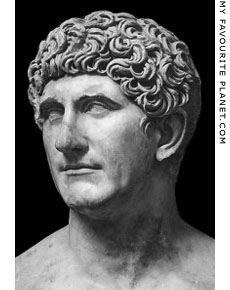

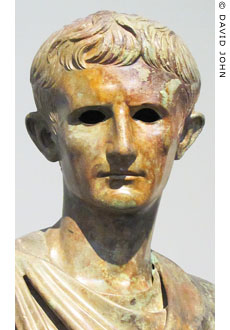

Marcus Antonius |

| |

Cleopatra VII |

| |

Marcus Agrippa |

| |

Caesar Augustus

(formerly Octavian)

Image details:

see note 20 below. |

| |

| |

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Timeline |

|

|

|

In case that's all a bit too much information, here is a brief chronological overview

of the statue - or statues - said to have stood on this site.

Article: © copyright David John, Athens and Berlin, 2007-2012. |

| |

| 506 BC |

|

The Athenians decide to erect a bronze statue of a four-horse chariot, paid for with one tenth of the ransom received for captives taken during Athenian military victories over Boeotia and Chalcis.

|

| before 420 BC |

|

Herodotus states that this statue stands on the left of the entrance to the Propylaia on the Acropolis.

|

| 362 BC |

|

Athens assists Sparta against Thebes at the second Battle of Mantinea. The Theban general Epaminondas wins the battle but is killed, perhaps by Gryllos, who is also killed.

Athenians dedicate a statue or statues, which may have been of "horsemen", either to the Dioskouroi or to Gryllos and Diodoros, the sons of Xenophon.

|

| 178 BC |

|

Statue(s) dedicated to King Eumenes II of Pergamon and his brother Attalus (later Attalus II) to commemorate their victory in a chariot race in the Panathenaic Games.

The plinth known as "the Pedestal of Agrippa" may have been built at this time.

Similar pedestals were also set up in front of the Stoa of Attalus in the Ancient Agora and the Stoa of Eumenes on the south slope of the Acropolis, as well as at Delphi.

|

| 31 BC |

|

After the Eumenes statue(s) has been rededicated to Antony and Cleopatra it is blown down by a storm.

|

| 27 BC |

|

This, or a new statue on this plinth, is dedicated to Marcus Agrippa, and perhaps also to Caesar Augustus.

|

| 2nd century AD |

|

Pausanias mentions "the statues of the horsemen" before describing the Propylaia, but claims not to know who they represent. |

|

| |

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Late Roman period to today |

|

|

|

From late Roman times until the 19th century Athens was attacked, sacked and pillaged by numerous invaders. One of the best-known and most devastating attacks was that of the east Germanic Heruli tribe in 267 AD (see the history of the Beulé Gate on gallery page 6).

Over time artworks and other treasures were either taken away as booty or broken up so that their materials could be sold or reused. At some point, whatever statues stood on the Pedestal of Agrippa also disappeared, perhaps melted down for their bronze.

The stones of several ancient buildings and monuments were redeployed to construct fortifications, houses, churches and mosques; marble blocks and statues were often ground down for the production of mortar. It is therefore remarkable that the pedestal has survived despite having no apparent practical function, although it later provided a useful prop for a crude gateway (see illustration below).

Despite such destruction and the ravages of nature, many buildings of the Acropolis remained relatively intact until the rock was the subject of a series of sieges and bombardments by cannons, mortars, muskets and grenades, the first of which was an enormous artillery assault by the Venetian Francesco Morosini in 1687, and the most recent in 1944 during fighting between British troops and Greek left-wing revolutionaries (see Edwin Droods Column, 21 June 2011).

From 1834, following Greece's independence from Ottoman Turkey, an international group of archaeologists and architects began to clear all post-Roman constructions from the Acropolis. Sorting through the centuries of debris, they were able to identify parts of ancient buildings such as the Temple of Athena Nike, which they have since been reconstructing.

It appears that some investigation and restoration work has been carried out on the Pedestal of Agrippa, but very little information about it has been published. Perhaps scholars believe that there is no more to be discovered about the pedestal, and anyway there are so many other more interesting monuments to be explored. Most recent mentions of the pedestal in archaeological literature merely repeat information contained in the reports of the 18th to early 20th centuries (see notes below, particularly note 18 concerning the inscription). |

|

|

| |

"Aufgang zur Akropolis" (The ascent to the Acropolis),

oil painting by Carl Wilhelm von Heideck, 1835. [21]

|

Although dated 1835, von Heideck probably completed the work from earlier studies. The painting shows the Frankish "Palace of the Acciaiuoli", built by the Florentine Duke of Athens Nerio I Acciaioli (died 1394) onto the north wing of the Propylaia (later used as the residence of the Disdar Aga, the Turkish military commander of Athens) and other crude fortifications constructed from parts of ancient monuments during the Medieval and Ottoman periods, including an arched gateway with one end leaning on the Pedestal of Agrippa. Damage to the ancient monuments caused by successive siege bombardments is also visible.

As with many Romantic paintings, it is difficult to know which features are true to life and which have been altered or invented to suit contemporary artistic taste. For example, damaged areas on the pedestal appear not to match exactly those visible today (see photo below). Whether this is due to artistic license or the skill of restorers is unclear.

Most of the fortifications were dismantled between 1834 and 1836 during enormous excavation and restoration works led by Ludwig Ross (see gallery page 12). By 1835 the west end of the Acropolis was a gigantic building site and this rustic scene no longer existed. Von Heideck left Greece the same year.

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlung, Munich. Inv. No. 9895.

Acquired by King Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1841 from the collection of Leo von Klenze.

Donated to the Bavarian State Collection by a private owner in 1932. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

Pedestal

of Agrippa |

Notes, references, links |

|

|

1. One of the few modern studies of the Pedestal of Agrippa was made by William Bell Dinsmoor (1886-1973), architectural historian at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), in 1913-1914, when he undertook restoration work, primarily aimed at preventing the monument from collapsing. He briefly summarized the project in the abstract of a paper in 1928:

"Although the Acropolis of Athens has been repeatedly investigated, and was, moreover, systematically excavated in 1885-1889, there still remain a few nooks and corners in which it was at that time expedient to leave the earth undisturbed. Among these localities was a portion of the entrance slope, which was not undermined because the huge pedestal of Agrippa (dated about 15 B.C. by an inscription but ascertained by the present investigator to have been erected 160 years earlier) seemed in danger of collapse. This danger having been averted by consolidation of the pedestal in 1914, permission was obtained from the Greek Archaeological Council to penetrate this untouched ground, which it was hoped would still contain some evidence as to the form of the approach to the Acropolis in the great period of Pericles."

William Bell Dinsmoor, Supplementary excavation at the entrance to the Acropolis, 1928. General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, December 27-29, 1928. American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 33, No. 1 (January - March 1929), pages 98-107. Archaeological Institute of America, 1929. At jstor.org.

This further work indeed produced much important information about the Classical path up to the Acropolis, including evidence which forced archaeologists to reappraise several theories concerning the nature of the approachway and the dating of political and social events in the city in antiquity.

Dinsmoor's brilliance, dedication and thoroughness is still celebrated by ASCSA today:

"During 1913–1914 Dinsmoor’s careful work and his surprising grasp of architectural detail enabled him to prove that the base of the Agrippa monument was much older than the first century after Christ and that it had had an earlier use."

A History of the American School of Classical Studies, 1882-1942, Chapter III: The Chairmanship of James Rignall Wheeler of Columbia University, 1901–1918. At ascsa.edu.gr, the website of the ASCSA.

See note 18 below on Dinsmoor's comments on the pedestal's inscription.

2. The Pedestal of Agrippa (Βάθρο του Αγρίππα), also known as the Monument of Agrippa (Μνημείο του Αγρίππα).

The total height of the monument is 13.4 metres, the base being 4.5 metres tall, 3.8 metres long (north-south) and 3.31 metres wide (east-west), and built of large blocks of poros limestone, which may have been originally clad with marble slabs.

Immediately above the base, are three narrow, stepped rows of stone, faced with blue-grey Hymettian Marble (from Mount Hymettos; Greek, Υμηττός, Ymittos, to the south of central Athens), supporting the 8.91 metre tall, slightly tapering pillar which is clad in slabs of the same marble. The slabs of the plinth are arranged in the pseudo-isodomic style (opus pseudoisodomum), that is with alternating courses of different heights. In this case there are eight taller layers alternating with seven layers of around a third of their height.

Another feature of this style is that the slabs, although well cut, are of different widths, with no attempt at vertical alignment or patterning of the joints across the vertical rows. There has also been no attempt to disguise the thickness of the slabs or pass them off as solid blocks, as the sides of the slabs at the end of the west and east faces of the pedestal are visible on the corner of the adjacent faces. Whether the pedestal was covered with a layer of some material or painted is not known. Some restoration drawings, such as Albert Tournaire's 1894 watercolour of the pillar monument of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi [see note 22], show a brightly painted pedestal, suggesting that the stonework may have been covered by a layer of painted plaster.

The pseudo-isodomic style is thought to have been developed in the 3rd century BC, and was widely used during the Hellenistic period.

The cornice (the projection crowning the top) and surviving part of the moulding at the foot of the pedestal itself (above the steps) are made of white Pentelic marble.

Holes on the top of the pedestal indicate where the statue or statues were attached to the stonework. These holes are visible from the top of the north wing of the Propylaia, which is not accessible to the public.

3. Colonel William Martin Leake (1777-1860), English antiquarian and topographer.

The Topography of Athens and the Demi, Volume I, The Topography of Athens: with some remarks on its Antiquities. Second edition. J. Rodwell, London, 1841. At Google Books. |

|

|

|

4. Herodotus on the bronze quadriga at the Propylaia

Herodotus, The Histories, Volume II, Book V, chapter 77. English translation by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, 1920. At Project Gutenberg.

The Greek version actually uses the word Propylaia (προπύλαια), rather than Propylon which was the name of the older gateway to the Acropolis.

καὶ τῶν λύτρων τὴν δεκάτην ἀνέθηκαν ποιησάμενοι τέθριππον χάλκεον: τὸ δὲ ἀριστερῆς χειρὸς ἕστηκε πρῶτον ἐσιόντι ἐς τὰ προπύλαια τὰ ἐν τῇ ἀκροπόλι: ἐπιγέγραπται δέ οἱ τάδε.

"ἔθνεα Βοιωτῶν καὶ Χαλκιδέων δαμάσαντες

παῖδες Ἀθηναίων ἔργμασιν ἐν πολέμου,

δεσμῷ ἐν ἀχλυόεντι σιδηρέῳ ἔσβεσαν ὕβριν:

τῶν ἵππους δεκάτην Παλλάδι τάσδ᾽ ἔθεσαν."

Further proof that Herodotus was talking about the statue after the Persian invasion is provided by his statement that the fetters used on the ransomed captives from Boeotia and Chalcis were put on display at the Acropolis, and that "these were still existing even to my time, hanging on walls which had been scorched with fire by the Mede [Persians]".

An alternative translation of the dedicatory verse, by G. C. Macaulay:

"Matched in the deeds of war with the tribes of Boeotia and Chalkis

The sons of Athens prevailed, conquered and tamed them in fight:

In chains of iron and darkness they quenched their insolent spirit;

And to Athene present these, of their ransom a tithe."

The History of Herodotus, Volume II, Book V, section 77. MacMillan and Co., London, 1914. At Project Gutenberg.

5. Euphranor's painting of the Battle of Mantinea

Pausanias wrote that Gryllos was depicted among the most famous men in Euphranor's painting in the Athenian Agora:

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, sections 3-4. At Perseus Digital Library.

He also mentioned the copy in the gymnasium of Mantineia:

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 9, section 8. At Perseus Digital Library.

He does not mention Diodoros, but Gryllos is mentioned again in Book 8, chapter 9, sections 5 (relief of Gryllos as a horseman on a slab) and 10 (Gryllos as the bravest man in the Battle of Mantineia), and chapter 10, sections 5-6 (the claim that he killed Epaminondas, his state funeral and "his likeness on a slab"). |

|

Marble head of Herodotus.

2nd century AD, Roman Imperial

period copy of a 4th century BC

Greek original.

Neues Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 295. |

|

|

6. The fame of Gryllos in ancient literature

VIII. "... and his sons, Gryllus and Diodorus, as Dinarchus states in the action against Xenophon; and they were also called Dioscuri".

X. "In the meantime, as the Athenians had passed a vote to go to the assistance of the Lacedaemonians [Spartans], he sent his sons to Athens, to join in the expedition in aid of the Lacedaemonians; for they had been educated in Sparta, as Diocles relates in his Lives of the Philosophers.

Diodorus returned safe back again, without having at all distinguished himself in the battle. And he had a son who bore the same name as his brother Gryllus. But Gryllus, serving in the cavalry (and the battle took place at Mantinea), fought very gallantly, and was slain, as Ephorus tells us, in his twenty-fifth book; Cephisodorus being the Captain of the cavalry, and Hegesides the commander-in-chief. Epaminondas also fell in this battle.

And after the battle, they say that Xenophon offered sacrifice, wearing a crown on his head; but when the news of the death of his son arrived, he took off the crown; but after that, hearing that he had fallen gloriously, he put the crown on again. And some say that he did not even shed a tear, but said, 'I knew that I was the father of a mortal man'.

And Aristotle says, that innumerable writers wrote panegyrics and epitaphs upon Gryllus, partly out of a wish to gratify his father. And Hermippus, in his Treatise on Theophrastus, says that Isocrates also composed a panegyric on Gryllus."

Diogenes Laertius (Greek: Διογένης Λαέρτιος, Diogenes Laertios; flourished around 3rd century AD), biographer of Greek philosophers. The lives and opinions of eminent philosophers, Book 2, chapters 48-59, Life of Xenophon. Translated by C. D. Yonge. At Peitho's Web, Classic rhetoric, persuasion, and philosophy.

7. The Dioskouroi (Διόσκουροι; Latin, Dioscuri), the mythical heroes Kastor (Κάστωρ; Latin, Castor) and Polydeukes (Πολυδεύκης; Latin, Polydeuces or Pollux), sons of Leda by two fathers: Zeus and King Tyndareus of Sparta. The twins, who were worshipped by Greeks, Etruscans and Romans, were transformed by Zeus into the stars today known as the Gemini constellation. They were closely associated with horses, often depicted as mounted warriors or hunters (such cult images of mythical horsemen were widespread among ancient cultures) and particularly revered by cavalry soldiers.

See Further information about the twins and depictions of them

in ancient art, on the Dioskouroi page of the MFP People section.

It has been speculated (by H.G. Lolling and others) that their statues were moved from another part of the Acropolis to a position before the Propylaia.

There was a sanctuary of the Dioskouroi, known as the Anakeion (Anekes, translated variously as "protectors", "guardians" and "on high", was one of the titles of the Dioskouri, according to Plutarch, Life of Theseus, 33. 1), beneath the Sanctuary of Aglauros on the east slope of the Acropolis. Pausanias (see note 19 below) describes a sculpture group dedicated to them there:

"The sanctuary of the Dioskouroi is ancient. They themselves are represented as standing, while their sons are seated on horses." Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 18, section 1.

Pausanias also mentions that "at Kephale [in Attica] the chief cult is that of the Dioskouroi, for the inhabitants call them the Megaloi Theoi [Great Gods]". Book 1, chapter 31, section 1.

8. Lykios, son of Myron

Lykios of Eleutherai, son of Myron, was a Classical Greek sculptor from Boeotia, active in the mid 5th century BC. He was the only known son and pupil of Myron of Eleutherai.

See: Lykios and Myron on the Ancient Greek artists page in the MFP People section.

For more about Eleutherai, see gallery page 36.

See also: Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Volume I, Central Greece, translated by Peter Levi. Penguin Books, 1971. Book I, page 62, note 127.

Levi states that "The horseman was by Myron's son Lykios of Eleutherai", without further explanation or reference. In the same note he adds to the mystery concerning the "horsemen" statues: "On the right as you go up [to the Propylaia], the little pedestal overlooking you seems at some time to have carried one of the two horsemen. But this puzzling slab has been inscribed on two opposite sides different ways up, and its material and lettering are apparently not the right date for the originals. To make things worse, the pedestal below the slab was reinscribed to Germanicus Caesar." |

|

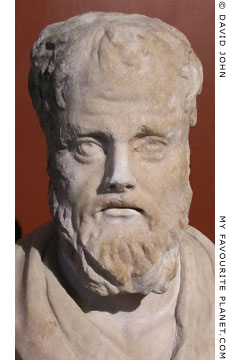

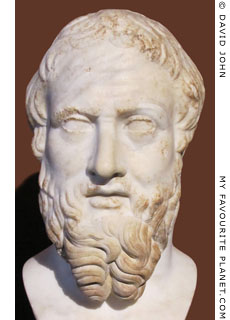

Marble bust of Isocrates

(436-338 BC).

2nd half of the 3rd century AD,

Roman period copy of a Greek

original. Height of bust 40.5 cm.

Neues Museum, Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 301. |

|

|

|

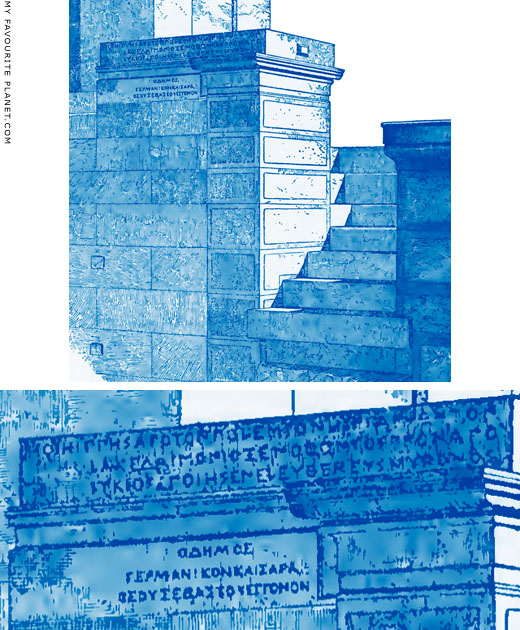

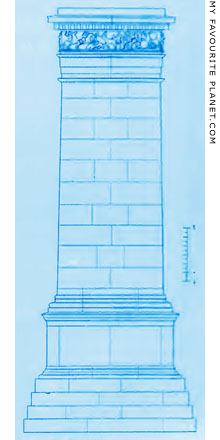

Reconstruction drawings of the inscribed pedestal on the wall flanking the south side of the stairway to the Propylaia (see also photo below), mentioned by Peter Levi and discussed by several other authors. The top drawing shows the small stairway leading to the Bastion of the Athena Nike Temple and the south wing of the Propylaia (see illustrations and a plan of the entrance to the Acropolis on gallery page 10).

Image source: Ernst Curtius, Die Stadtgeschichte von Athen. Berlin, 1891. Republished in Martin Luther D'Ooge, The Acropolis of Athens. Macmillan, New York, 1909.

The upper slab of grey marble (perhaps Pentelic or Hymettian marble) is inscribed stoichedon:

ℎοι ℎι[ππ]ῆς [⋮] ἀπὸ τ̣ο͂ν [πο]λεμίον ⋮ ℎιππαρ[χ]ό[ν]-

τον ⋮ Λακεδ̣αιμονίο [⋮] Ξ̣[ε]νοφο͂ντος ⋮ Προν[ά]π[ο]-

ς ⋮ Λύκιο[ς ⋮ ἐ]ποίησεν [⋮] Ἐλευθερεὺς [⋮ Μ]ύ̣[ρ]ο̣ν̣[ος].

The cavalry [dedicated this] from [the spoils of] the enemy, when the cavalry commanders

were Lakedaimonios, Xenophon, Pronapes.

Lykios of Eleutherai, son of Myron, made it.

Inscription IG I³ 511 (= IG I² 400,Ia; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 135) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

The slab was originally part of a statue base signed by the sculptor Lykios around 450-430 BC. It was found in 1889 near southwest corner of the Parthenon. Holes in the top of the base indicate that the statue was of a horse (with or without a rider), facing right, being led by a man standing next to it. The monument was dedicated by three cavalry generals (hipparchs) to commemorate a battle, although its place and date remain a subject of debate.

In the 1st century BC, during the early Roman Imperial period (probably during the reign of Augustus), the base was turned over and reinscribed on the opposite side with an exact copy of the original dedication in archaistic early Attic lettering. IG I² 400,Ib (DAA 135a). The statue placed on the reused based is thought to have been a newly-made work of a similar type, although probably not a copy of Lykios' work.

Around the same time another, apparently new base of grey Hymettian marble was also inscribed with a copy of the dedication in the same archaistic lettering, but by a different stonemason. Three fragments of the inscription were discovered at different times in various places around the Acropolis IG I² 400,II (DAA 135b). The findspots of two fragments are unknown, but "Fragment b" was found in 1880, built into a late wall to the west of the Pedestal of Agrippa.

It is therefore believed that Lykios' original statues may have been destroyed or moved elsewhere (perhaps taken to Rome?), and later replaced by two equestrian statues on similar bases, perhaps standing on a single pedestal.

The inscription on the block of Pentelic marble below the slab with Lykios' signature states:

ὁ δῆμος

Γερ[μ]ανικ[ὸν Κα]ίσαρα

θεοῦ Σε[βαστοῦ ἔγγονον].

The demos [dedicated this statue of] Germanicus Caesar, descendant of the divine Augustus.

Inscription IG II² 3260 (see DAA 135, 135a, 135b) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

This inscription is believed to be another block of the monument's pedestal. It apparently presents the statue (or statues) as a dedication by the demos (the people) to Germanicus Caesar, the adopted son and heir of Emperor Tiberius (reigned 14-37 AD), and may have been inscribed at the time of Germanicus' visit to Athens in 18 AD.

It is thought that these may have been the statues Pausanias saw on his way up to the Propylaia, and that he may have been confused or bemused by the extra dedication to Germanicus. |

|

| |

The present condition of the inscriptions at the top of the stairway to the Athena Nike Temple bastion.

They far are too high to read from the steps up to the Propylaia, without the aid

of binoculars or a zoom lens. The marble slab with the signature of the sculptor

Lykios is at the top of the pile. Height 22 cm, length 180 cm, width 87 cm.

See a photo of the stairway leading up to the Temple of Athena Nike on gallery page 12. |

| |

9. Doctor Richard Chandler (1738-1810), English antiquary and clergyman. He, Nicholas Revett and artist William Pars (1742-1782) were commissioned by the Society of Dilettanti to study the antiquities of Greece and Asia Minor 1764-1766. They stayed in Athens 31 Aug 1765 - 11 June 1766.

Chandler wrote about the Propylaia: "... before each wing was an equestrian statue." But Leake states that he made several errors, "having misapprehended" works of earlier antiquarians Spon and Wheler (see gallery page 6).

Chandler translated the dedication to Agrippa as: "The people have erected Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, thrice consul, friend of Caius." Caius being a reference to Caesar Octavianus [see note 18 below].

At the end of the same chapter he also mentions, for no apparent reason, that "No dog or goat was suffered to enter the Propylaia".

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, chapter IX, page 43. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

See also: Rev. Edward John Burrow, The Elgin marbles: with an abridged historical and topographical account of Athens, Note, page 118. James Duncan, London, 1837. At Google Books.

10. Apobates as a sport for the elite, referred to in The Erotikes, a 4th century BC essay ascribed to (although probably not written by) the Athenian orator Demosthenes:

"... slaves and aliens share in the other sports but that dismounting is open only to citizens and that the best men aspire to it."

Demosthenes, Erotikos 23. In Demosthenes VII, translated by N. W. DeWitt and N. J. DeWitt. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1949.

It was a demanding and dangerous discipline, requiring strength, stamina and speed, especially on the part of the armed dismounter, who wore a helmet and shield, and excellent coordination between him and the chariot driver. It would also have been an expensive sport since competitors had to have a good racing chariot and four horses at their disposal. Herodotus indicated how wealthy the Athenian Miltiades son of Cypselus was by saying he was rich enough to keep a four-horse chariot, and that he was an Olympic victor in the four-horse chariot race. His brother Kimon won the event three times, despite being exiled from Athens.

"At that time in Athens, Pisistratus held all power, but Miltiades son of Cypselus (Μιλτιάδης ὁ Κυψέλου) also had great influence. His household was rich enough to maintain a four-horse chariot ..."

Herodotus, Histories, Book 6, chapters 35-36 and 103. At Perseus Digital Library.

See: Nancy B. Reed (Associate Professor, Department of Art, Texas Tech University), A chariot race for Athens’ finest: the apobates contest re-examined. In: Journal of sport history, Volume 17, No. 3 (Winter 1990). PDF document.

11. Erichthonius and the invention of the four-horse chariot in Athens

In Greek myths referred to by several ancient writers, Erichthonius (Greek, Ἐριχθόνιος, Erichthonios), the serpent-like king of Athens, was the son of the deities Hephaistos and Gaia (the Earth), adopted by Athena. In other versions he was generated by Hephaistos' semen when the metalworking god attempted to rape Athena. He was the first to use a four-horse chariot. This so impressed Zeus that he made him into the stellar constellation Auriga (Latin, charioteer; Greek, Ηνίοχος, heniochos, charioteer, literally "holder of the reins"), which, according to Hyginus (see below), was referred to as "Erichthonius" by the Greek polymath, mathematician and astronomer Eratosthenes of Cyrene (Ἐρατοσθένης, circa 276-195 BC).

He is also credited with introducing to Athens the plough and silver smelting, as well as erecting the first xoanon (image or statue of a deity) and temple of Athena on the Acropolis and founding the Panathenaic Festival.

There remains some confusion about whether these innovations were introduced by Erichthonius or Erechtheus I (Ἐρεχθεύς), mentioned by Homer ("great-hearted Erechtheus", Iliad ii. 547, and Odysssey vii. 81) who was perhaps a later king, although the myths and legends may be referring to the same person.

"[From when] at the time of the first Panathenaia, [Erich]thonius yoked up a chariot and showed how to race, and [gave] the Athenians [their name, and the glory]..."

Extract from the "Parian Marble" (or Parian Chronicle, το Χρονικό της Πάρου), a stele discovered on the island of Paros, dated to around 264-263 BC, inscribed with a Greek chronology of the years 1581-264 BC. According to the chronological order of events, the first Panathenaic festival is estimated to have take place in 1506/5 BC.

See: The Parian Marble: Translation, A. 1, The lost fragment, introduction & entries 1-10, in Greek with a translation by Gillian Newing. Website of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

"'Twas Ericthonius first took heart to yoke

Four horses to his car, and rode above

The whirling wheels to victory."

The Georgics (Greek Γεωργικά, "On working the earth") by the Roman poet Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro, 70-19 BC), published around 29 BC. See: J. B. Greenough (editor), Vergil. Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics of Vergil, Book 3, lines 134-136. Ginn & Co, Boston, 1900. At Perseus Digital Library.

"The Charioteer. In Latin we call him 'auriga' – Erichthonius by name, as Eratosthenes shows. Jupiter [Zeus] seeing that he first among men yoked horses in four-horse chariots, admired the genius of a man who could rival the invention of Sol [Helios], who first among the gods made use of the quadriga. Erichthonius first invented the four-horse chariot, as we said before, and also first established sacrifices to Minerva [Athena], and a temple on the citadel of the Athenians."

Hyginus, Poeticon astronomicon, 2.13, The Charioteer. At the Theoi Project.

For further information about Hyginus, see the note in Homer part 2 in the MFP People section.

On the other hand, Herodotus, always keen to find foreign antecedents to Greek myths and customs, believed the four-horse chariot originated in Africa:

"And it is from the Libyans that the Greeks have learned to drive four-horse chariots."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 4, chapter 189. Translation by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press, 1920. At Perseus Digital Library.

12. Eusebius of Caesarea (Greek, Ευσέβιος ο Καισαρείας; also known as Eusebius Pamphili; circa 263-339 AD), Christian historian, Bishop of Caesarea in Palestine (from about 313 AD). His Chronicle (Παντοδαπὴ Ἱστορία, Pantodape historia, Universal History), written in two parts in Greek, has been lost but is known from copied excerpts and translations in Latin (by Saint Jerome around 380 AD) and Armenian.

The second part, Chronological Canons (Greek, Χρονικοὶ Κανόνες, Chronikoi kanones), contained tables of parallel timelines of historical events, including a list of Olympic Games and winners (mainly in the stadion running race) from 776 BC to 217 AD.

See: Eusebius' Chronicle, translated from Classical Armenian by Robert Bedrosian.

At rbedrosian.com. |

The Pedestal of Agrippa from the southwest. |

| |

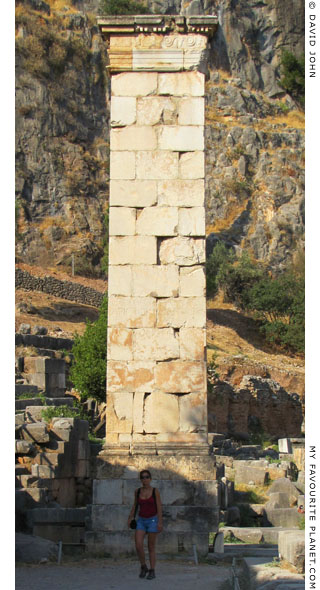

The Column of Prusias II of Bithynia (ruled

182-149 BC), at the northeast corner of the

Temple of Apollo in Delphi. According to an

inscription on the 10.45 metre high limestone

plinth, on which stood an equestrian statue

of Prusias, it was dedicated by the Aetolian

Confederacy in 182 BC. The Bythinian king was

at the time an ally of Eumenes II of Pergamon,

a colossal statue of whom stood nearby.

Another Hellenistic pillar monument at Delphi

was the Monument of Aemilius Paullus [22]. |

| |

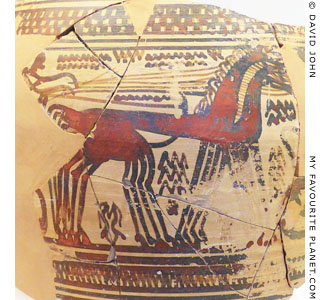

A fragment of the body of an Archaic

Athenian amphora with an early depiction

of a four-horse chariot. 750-700 BC.

Kerameikos Archaeological Museum, Athens. |

| |

|

13, 14 & 15. Plutarch (Πλούταρχος; name as Roman citizen Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, Μέστριος Πλούταρχος, circa 46-120 AD), Greek historian, biographer and essayist, born in Chaeronea, Boeotia, central Greece. His best known surviving works are The Parallel Lives and Moralia. He also served as a priest at the oracle in the Temple of Apollo, Delphi.

Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The life of Antony. Volume 9 of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920. At Bill Thayer's website, LacusCurtius: Into the Roman World, University of Chicago.

16. Cassius Dio (circa 155 or 163/164 - after 229 AD), Roman consul and historian who wrote his Historia Romana in 80 volumes. Roman History, Book LIV. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1914-1927. Also at LacusCurtius.

The island of Aegina is said to have been given to Athens by Mark Antony in 41 BC.

17. Marcus Agrippa as "benefactor and saviour"

See: Christian Habicht, Marcus Agrippa Theos Soter, Hyperboreus, Volumen XI (2005), Fasciculus II, page 242. At Bibliotheca Classica Petropolitana. |

|

Detail of a marble bust from a herm

from Delphi, tentatively identified as a

portrait of Plutarch, or the Neoplatonic

philosopher Plotinus.

Roman Imperial period,

2nd or 3rd century AD.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

The top of the Pedestal of Agrippa, crowned by a cornice made of white Pentelic marble.

Part of the stone base on which the statue (or statues) stood can be seen above the cornice.

The inscription dedicating the monument to Agrippa was on the west face of the pedestal, left.

Three metal ties fixed to the left of the south face to hold corner blocks in place. |

| |

The top half of the west face of the Pedestal of Agrippa,

late afternoon (hence the red atmospheric colouring). |

| |

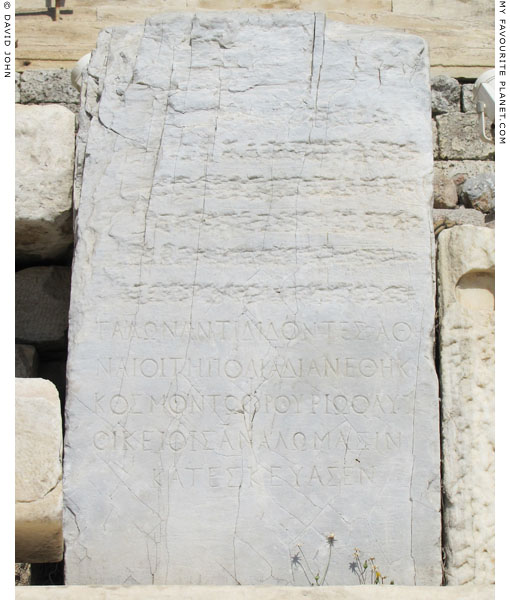

18. The inscription dedicating the Pedestal to Agrippa

What remained of a five-line inscription was noted the west face of the pedestal by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett during their stay to Athens 1751-1753 (see note on page 12).

[Ο δη]μος

Μ[αρκον] Αγρίππα[ν]

Λε[υκίου] υιόν

τρίς ύ[πατ]ον

τον [ε]α[τ]ου ε[υερ]γέτη[ν]

|

The deme [dedicated this]

to Marcus Agrippa,

son of Lucius,

thrice consul,

its benefactor

|

Doctor Richard Chandler also recorded the inscription a decade later (see note 9 above), and relates that he read the badly worn lettering through a pocket telescope. His version differs from Stuart's.

Chandler's version:

[Ο δη]μος

Μ[αρκον] Αγρίππα[ν]

Λε[υκίου] υιόν

τρίς ύ[πατ]ον τον

Γαιω ε[υερ]γέτη[ν]

|

The people [erected]

Marcus Agrippa,

son of Lucius,

thrice consul,

the friend of Caius. |

Following the publication of both versions, scholars - including William Martin Leake and Charles Robert Cockerell - concurred that Chandler was mistaken in his mention of "the friend of Caius" (for Caius Caesar Octavianus, alias Augustus). Stuart's version, edited by the later scholars, has been generally accepted.

See inscription IG II² 4122 (and IG II² 4123) at epigraphy.packhum.org.

On 1st November 1813 the English traveller Thomas Smart Hughes (1786-1847) visited the Acropolis with his travelling companion Robert Townley Parker (1793-1879), later Member of Parliament for Preston, and Giovanni Battista Lusieri (1755-1821), the Italian painter employed by Lord Elgin to supervise the removal and shipping of the Elgin Marbles to England.

Hughes mentions that they stood on top of the Pedestal of Agrippa to enjoy the view of the Saronic Gulf (although he does not tell us how they got up there). Of the inscription he tells us he was able to see the name of Agrippa, and writes (curiously in a footnote and not in the main text), "the whole inscription was visible in Chandler's time", confirming other testimonies that the inscription had by then almost completely disappeared. Nevertheless, he agrees with the amended version of the inscription.

Later travellers complained of not being able to see the inscription at all, and thereafter the only mentions of this inscription are repetitions of the reports of 18th and early 19th centuries.

In a paper on the monument, written in 1919, William Bell Dinsmoor (see note 1 above) referred to a manuscript of Louis François Sébastien Fauvel (1753-1838), the French consul and antiquarian who lived in Athens 1803-1822:

"The inscription, as Fauvel pointed out in manuscript notes, is cut on a surface roughened by the erasure of an earlier inscription, in five lines but with much larger letters, of which a few traces are preserved."

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Monument of Agrippa at Athens, abstract of a paper read at General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, December 29-31, 1919. American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 24, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar. 1920), page 83. At the Internet Archive.

This quote is from an abstract of Dinsmoor's paper, and although this is often cited by recent authors, there is no mention made of the entire paper, which appears not to have been published. In the abstract Dinsmoor offers no new information about the inscription, nor does he give any indication that he or anyone else inspected it closely.

Several more recent authors have written that the Agrippa inscription and the traces of the earlier dedication are still to be seen, and the few who mention its location on the pedestal say that it is on the monument's west face, either at the top or at two thirds of the way up.

"The following inscription is still visible on the west side of the pedestal:

The city (dedicates this) to Marcus Agrippa, son of Leukios, three times consul and benefactor.

Below this inscription are the traces of an earlier one, which probably referred to Eumenes and was erased."

Ioanna Venieri, archaeologist, Pedestal of Agrippa, on Odysseus, website of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, 1912.

Recently an information board was set up near the pedestal to explain the monument to visitors, most of whom ignore it as they head up to the top of the Acropolis, keen to see the Parthenon. The board provides the text and translation of the inscription as recorded by Stuart and Revett, and states:

"Agrippa was a benefactor of the city, as indicated by the incised honorary inscription on the western face of the pedestal."

However, it seems odd that of all the hundreds of photos and drawings of the pedestal published in print and online, there is not one of the inscription. Nor is even a drawing or a squeeze of the inscription to be found.

This author has examined the pedestal several times, from all possible angles, in search of this inscription, in differing lighting conditions and at various times of day (the best time should presumably be early afternoon, when the sun is shining), also with the aid of zoom lenses; he has even asked other visitors to the Acropolis if they could spot it. So far this elusive dedication has failed to reveal itself. (see photo above). One can only presume that the inscription must have been removed from the pedestal at some point, and since it is not to be seen either in the Acropolis Museum or the Epigraphical Museum, it is either lost or stored away somewhere.

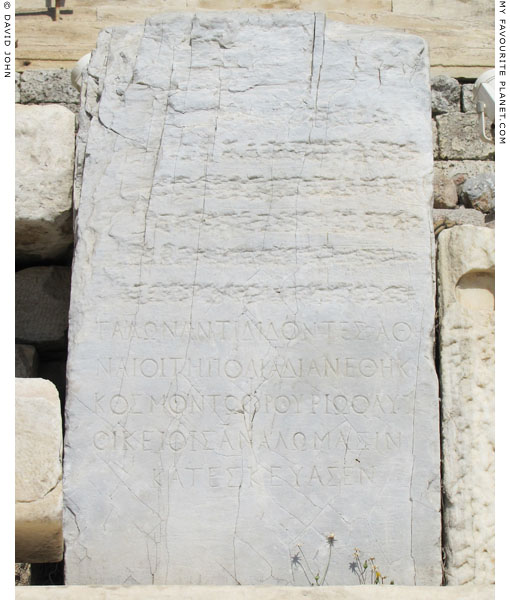

An inscription on a block of blue-grey Hymettian marble, the same stone as on the plinth, has been placed on display, unlabelled (as is the case with other inscriptions displayed on the Acropolis), next to the pedestal (see photo below). This is clearly a dedication to Marcus Agrippa, however, the line mentioning "thrice consul" is missing, even though the block is large enough to have accommodated more than five lines. Either this is a different inscription, or the missing line was inscribed on another block, or the dedication was misread by Stuart, Revett and Chandler. It is also unclear how this large, thick block would have been affixed to the plinth.

See:

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, volume 2 ("new edition"). Notes on pages 101-102. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Library.

Richard Chandler, Inscriptiones antiquae, pleraeque nondum editae, in Asia Minori et Graecia, praesertim Athenis collectae : cum appendice, Pars II, XIV. Page xxiii. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1774. At the Internet Archive.

Chandler adds the Latin translation: "Populus posuit Marcum Agrippam Lucii filium, ter Consulem, Caii amicum."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, chapter IX, page 43. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At Google Books.

Thomas Smart Hughes, Travels in Greece and Albania Volume I. Second edition, page 255. Colburn and Bentley, London, 1830. At Google Books. |

|

The west side of the Pedestal of Agrippa. |

|

| |

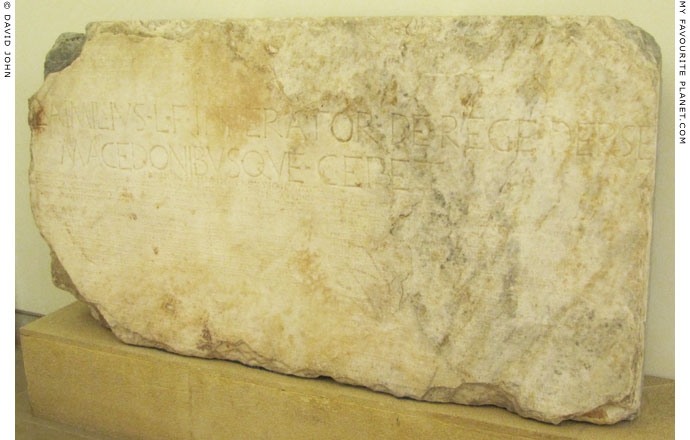

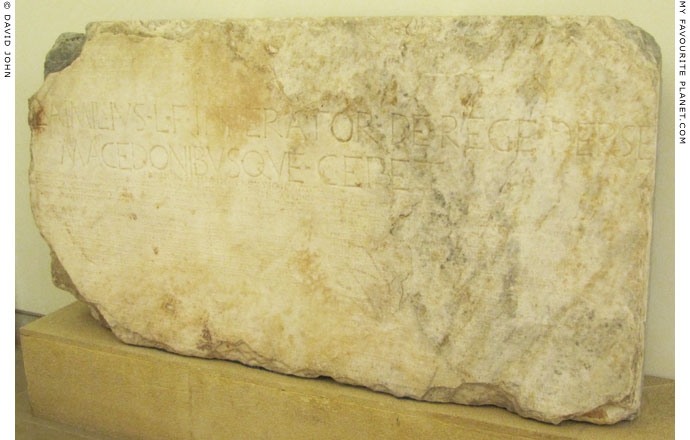

A slab of blue-grey marble inscribed with a dedication in Greek to Marcus Agrippa,

displayed next to the Pedestal of Agrippa on the ascent to the Propylaia.

Ο ΔΗΜΟΣ

ΜΑΡΚΟΝ ΑΓΡΙΠΠΑΝ

ΛΕΥΚΙΟΥ ΥΙΟΝ

ΤΟΝ ΕΑΤΟΥ ΕΥΕΡΓΕΤΗΝ |

The deme [dedicated this]

to Marcus Agrippa,

son of Lucius,

its benefactor |

|

| |

Another inscribed block of blue-grey marble, displayed next to the inscription

above, near the Pedestal of Agrippa. An Inscribed text of six or more lines at

the top of the block has been deliberately erased. |

|

19. Pausanias on the "horsemen" at the Propylaia

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, Chapter 22, Section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

See a profile of Pausanias in the MFP People section.

Leake translates "made merely to beautify the place" as "made only for the sake of ornament or propriety", adding as a footnote, "Possibly Pausanias may have meant by this word 'loyalty, or a due deference to the Roman government'."

Pausanias makes no direct mention of the enormous pedestal or the dedication to Agrippa. Whether this was due to his sense of discretion, diplomacy or taste, he also omits several other monuments on the Acropolis, including the circular temple of Roma and Augustus which stood at the east end of the Parthenon. |

|

|

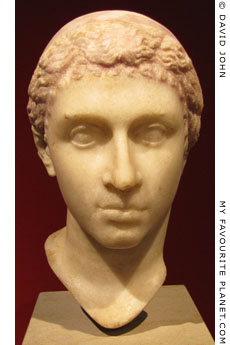

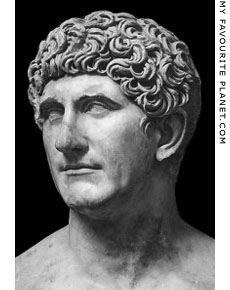

20. Busts of Mark Antony, Cleopatra, Agrippa and Augustus

Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony, 83-30 BC). Marble bust.

Vatican Museum, Rome.

Cleopatra VII (Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ, 69-30 BC), last pharaoh and Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. Marble portrait head made during her lifetime, around 40-30 BC. Probably from a villa south of Rome.

Height 29.5 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1976.10.

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (circa 63-12 BC). Marble head found in 1893 in the Prytaneion of Magnesia on the Meander, Turkey. Thought to be a portrait of Agrippa, dated to 1-25 AD.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 28.6.

Compare the image above to the bust of Agrippa, right, the marble original of which is in the Louvre, Paris. Discovered in 1792 on the site of the ancient town of Gabii, east of Rome. From the Borghese Collection; purchased for the Louvre in 1807.

Height of original 46 cm.

Inv. No. Ma 1208 (MR 402).

Octavian / Augustus (63 BC-14 AD), Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus, formerly known as Gaius Octavius Thurinus before becoming the first Roman emperor. Fragment of a bronze equestrian statue, 12-10 BC, found in the Aegean Sea between the islands of Euboea and Agios Efstratios.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. X. 23322.

21. Carl Wilhelm von Heideck (1788-1861) was a Bavarian military officer and philhellene who fought for Greece in the Greek War of Independence and took part in several battles, including the unsuccessful attempt to relieve Athens from the Turkish siege in 1827.

In 1828 Ioannis Kapodistrias, Governor of Greece, appointed him commander of Nafplion, and soon after he became the military governor of Argos.

He was an honorary member of the Münchner Akademie (Munich Academy), and after leaving Greece in 1835 he devoted his time to painting. |

|

Cast of the bust of Agrippa

from the marble original

(41-54 AD) in the Louvre.

Ara Pacis, Rome. |

|

| |

Detail of the north side of the relief which ran around the top of the pillar of

the Aemilius Paullus Monument at Delphi. The relief depicts the First Battle

of Pydna in 168 BC between Romans and the last Macedonian king Perseus.

The defeated Macedonians, fighting right to left, are distinguished

by their round, decorated shields (see also illustrations on the

Pan and Medusa part 6 pages in the MFP People section).

Delphi Archaeological Museum.

|

22. Aemilius Paullus Monument at Delphi

The monument (also known as the Pydna Monument), which stood in front the Temple of Apollo in Delphi (near the monuments of Eumenes II and Prusias II, see photo above), was originally commissioned by Perseus (Περσεύς, circa 212-166 BC), the last Macedonian king of the Antigonid dynasty. Following his defeat by the Roman consul and general Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus (circa 229-160 BC) at the First Battle of Pydna on 22 June 168 BC *, the victor had the pillar rededicated with an equestrian statue of himself.

Plutarch (who was a priest at Delphi) and Livy both narrated how Aemilius Paullus appropriated the pillar:

"At Delphi, he saw a tall square pillar composed of white marble stones, on which a golden statue of Perseus was intended to stand, and gave orders that his own statue should be set there, for it was meet that the conquered should make room for their conquerors."

Plutarch's Lives: The Life of Aemilius, Chapter 28, section 2. English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1918. At Perseus Digital Library.

"... and with a moderate retinue, [Aemilius Paullus] began his journey, accompanied by his son Scipio, and Athenaeus, brother of king Eumenes [Eumenes II of Pergamon], and directed his route through Thessaly to the famous oracle at Delphi; where he offered sacrifices to Apollo, and, in honour of his victory, destined for his own statues some unfinished columns in the vestibule, on which they had intended to place statues of king Perseus."

Titus Livius (Livy), History of Rome, Book 45, chapter 27. Translated by William A. McDevitte. Henry G. Bohn, London, 1850. At Perseus Digital Library.

The monument's dedication was inscribed in Latin on a marble slab (see photo below):

L. AIMILIUS L. F. INPERATOR DE REGE PERSE MACEDONIBUSQUE CEPET

L. Aemilius, son of Lucius, commander-in-chief, seized [this] from King Perseus and the Macedonians.

The various reference numbers have been assigned to the inscription according to several epigraphical publications, including ILLRP 00323 (page 326).

At the top of the pillar a relief depicting the Battle of Pydna ran around all four sides, with a separate scene on each side. It is thought that each scene illustrates an episode from the battle, and scholars have attempted to equate them with accounts by Livy and Plutarch. There has been much speculation about the possibility that some of the figures of the relief are meant to represent specific individuals (even the riderless horse, to be seen in the photo above). Livy's mention of plural "unfinished columns" intended for statues of Perseus, the type of armour and shields depicted, as well as other inscriptions associated with the monument, have also fuelled much scholarly debate.

Estimated height of pillar 9.58 metres (some sources 9.97 metres).

Upper plinth supporting the statue 1.25 x 2.45 metres.

Frieze height 31 cm; entire length about 6.5 metres.

The monument was excavated by the French Archeological School in Athens 1893-1896. Only the foundation and some of the blocks of the pillar remain at the site in Delphi; the inscription and frieze can be be seen in Room XII of the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

See:

M. F. Courby, Topgraphie et Architecture: La Terrasse du Temple. Fouilles du Delphes, Tome II, Chapitre IX: Les monuments votifs dans la région du temple. École française d'Athènes. Éditions de Boccard, Paris, 1927. At the Internet Archive.

Chapter IX deals with preliminary studies of the remains of votive monuments found around the Temple of Apollo, including the pedestals of Prusias II, Eumenes II and Aemilius Paullus (see illustration, right).

About the inscriptions on the monuments: Fouilles de Delphes, Tome III, Ascicule IV: Inscriptions de la terrasse du temple et de la région nord du sanctuaire. Nos. 1 à 86, Monuments de Messéniens de Paul-Émile et de Prusias par Gaston Colin. École française d'Athènes. Éditions de Boccard, Paris, 1930. At the Internet Archive.

Heinz Kähler, Der Fries vom Reiterdenkmal des Aemilius Paullus in Delphi. Monumenta Artis Romanae, V. Gebr. Mann, Berlin, 1965.

Jerome Jordan Pollitt, Art in the Hellenistic Age, pages 156-157. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Linda Marie Günther, L. Aemilius Paullus und „sein“ Pfeilerdenkmal in Delphi. In: Ch. Schubert und K. Broderson, Rom und der griechische Osten (Festschrift Hatto H. Schmitt), pages 81-85. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1995.

James Allen Yavenditti, Tropaea in Oriente: Roman victory monuments located within the eastern Mediterranean. M.A. thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Athens, Georgia, 2004.

* The second Battle of Pydna was in 148 BC. Quintus Caecilius Metellus defeated the pretender Andriscus (Ἀνδρίσκος, also known as the Pseudo-Philip) who had claimed to be the son of Perseus and declared himself King Philip VI of Macedonia (see Alexander the Great in the MFP People section). |

|

One of the early reconstruction drawings of the Aemilius Paullus Monument, made by members

of l'École française d'Athènes.

A model of the pedestal is

displayed in the Museo Della

Civiltà Romana (Museum of

Roman Civilisation), Rome. |

|

| |

The dedicatory inscription from the Aemilius Paullus Monument at Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The Pedestal of Agrippa in front of the colonnaded porch of the north wing of the Propylaia, which

contains a hall known as the "Pinakotheke" (picture gallery) because paintings were displayed here. |

This page was first written and compiled in 2010.

Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contents | contributors | impressum | sitemap |

| |