| |

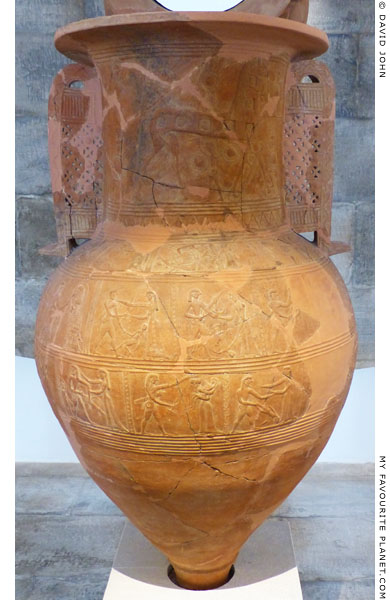

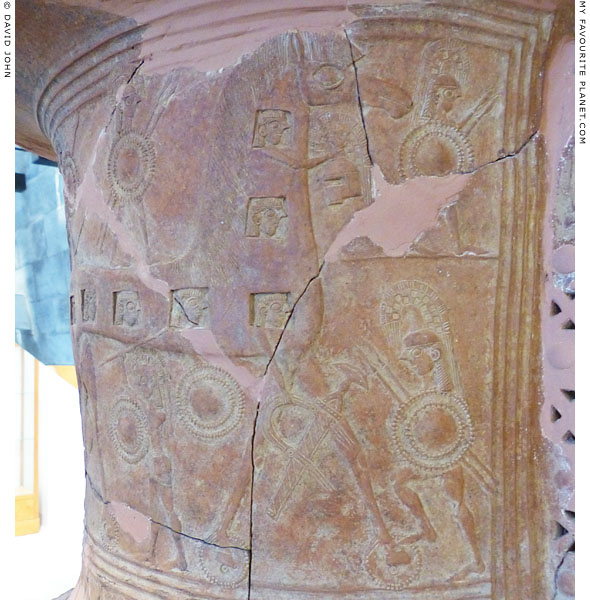

Relief on the neck of the "Mykonos Vase" depicting Greek warriors

inside the Trojan Horse, with other warriors around it. |

| |

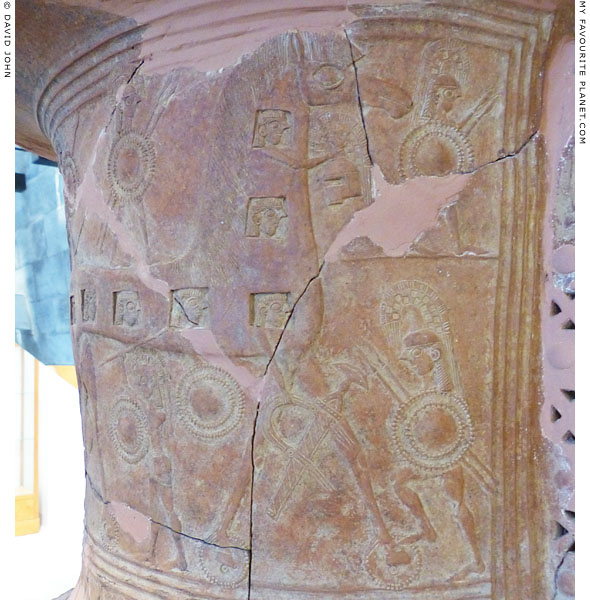

The right side of the neck of the "Mykonos Vase". |

| |

One of the bottom panels on the body of the "Mykonos Vase", depicting a Greek

warrior killing a male child with his sword, with a woman, presumably the boy's

mother, trying to save him. Blood falls in incised wavy lines from the child's body.

The relief panels have been referred to as "metopes" because they are separated

by raised vertical bands in a way similar to architectural triglyphs. |

| |

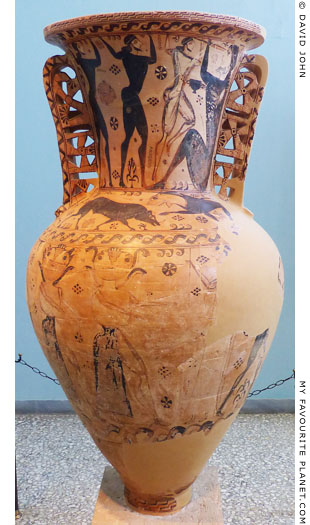

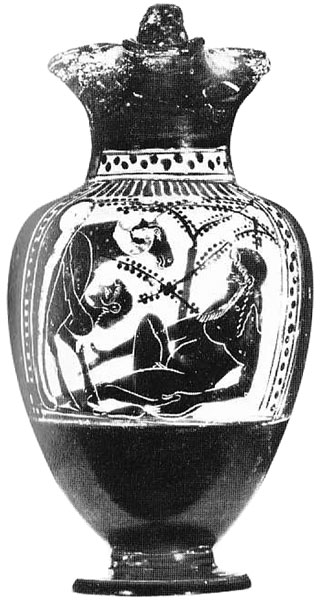

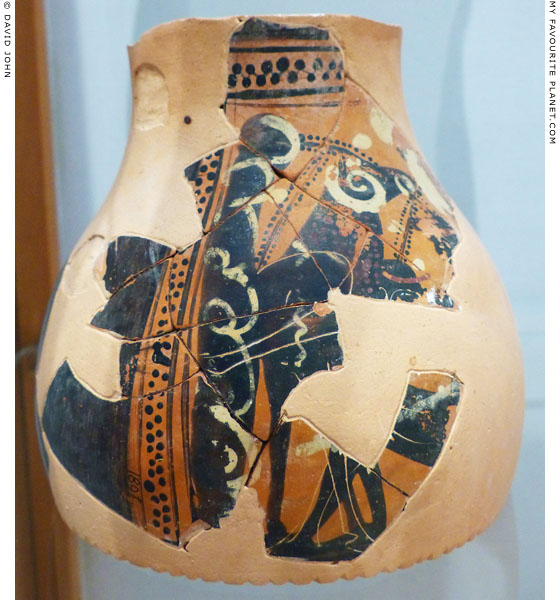

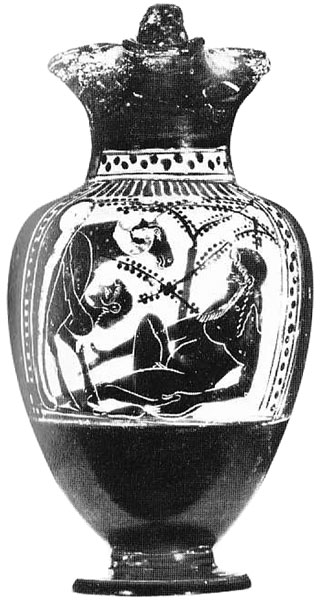

The neck of a large Proto-Attic amphora, known as the "Eleusis Amphora", depicting

the blinding of Polyphemos, a scene from Homer's Odyssey (Book 9, lines 187-542).

Odysseus and two of his companions drive a sharpened, glowing olive stake into

the eye of the Cyclops Polyphemos, who holds a kantharos (wine cup).

Around 660 BC (made about the same time as the "Mykonos Vase" above).

The name vase of the Polyphemos Painter. Excavated in 1954 in the West

Cemetery, Eleusis. Pot Burial Γ6. It had been used as a funeral urn and contained

the skeleton of a 12 year old boy. Height 142 cm. Height of figures around 42 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2630.

|

The amphora was discovered at Eleusis in 1954, during excavations led by Greek archaeologist George E. Mylonas (see the note in Demeter part 1), among prehistoric burials in soil only 25-30 cm below the modern level. It is thought that the amphora had been damaged and many parts dragged away by centuries of ploughing.

Both the neck and the body of the vase are painted with the black and white outline technique, and depict heroes fighting monsters. The body shows Perseus beheading the Gorgon Medusa.

In The Odyssey, Book 9, Odysseus and twelve of his men are trapped in the cave of Polyphemos (Πολυφημος, Many-Voiced, Many Words, or Abounding in Songs and Legends), a son of Poseidon and one of an ancient race of gigantic Cyclopes (Κύκλωπες, Kyklopes; singular, Κύκλωψ, Kyklops, round-eyed). The mouth of the cave, in which Polyphemos lives with his sheep and goats, is blocked by an emormous rock which only he can move. During the evening and following day, the Cyclops eats six of Odysseus' companions, two at a time.

On the second evening, after he has eaten two of the men, the cunning Odysseus offers him strong Maroneian wine (given to him by the Thracian Maron) to wash down his meal. He quickly becomes drunk and falls into a stupor: "and reeling fell upon his back, and lay there with his thick neck bent aslant, and sleep, that conquers all, laid hold on him. And from his gullet came forth wine and bits of human flesh, and he vomited in his drunken sleep." Then, "... when the wine had stolen about the wits of the Cyclops", the seafarers heat in the fire the sharpened end of an olive wood stake a "fathom's length", which they had earlier cut from his shepherd's staff, itself as massive as the mast of a large ship. The glowing end can be seen in the amphora painting, as the three men drive it into the Cyclops' eye. In Homer's account, four men, chosen by lot, carried the stake while Odysseus "leaned heavily over from above and twirled the stake round".

Homer gave a horrifically graphic description of the destruction of Polyphemos' eye, but did not write that he had only one, in fact spoke of his "eyelids" and "brows" in the plural. In ancient depictions of the scene the Cyclops is often shown in profile, so that only one eye can be seen, which may have given rise to the idea that he was one-eyed. However, in several representations (including some shown below) he has two or even three, as in the mosaics in patras and Piazza Amerina, Sicily (see below).

"Then verily I thrust in the stake under the deep ashes until it should grow hot, and heartened all my comrades with cheering words, that I might see no man flinch through fear. But when presently that stake of olive-wood was about to catch fire, green though it was, and began to glow terribly, then verily I drew nigh, bringing the stake from the fire, and my comrades stood round me and a god breathed into us great courage.

They took the stake of olive-wood, sharp at the point, and thrust it into his eye, while I, throwing my weight upon it from above, whirled it round, as when a man bores a ship's timber with a drill, while those below keep it spinning with the thong, which they lay hold of by either end, and the drill runs around unceasingly. Even so we took the fiery-pointed stake and whirled it around in his eye, and the blood flowed around the heated thing. And his eyelids wholly and his brows round about did the flame singe as the eyeball burned, and its roots crackled in the fire. And as when a smith dips a great axe or an adze in cold water amid loud hissing to temper it - for therefrom comes the strength of iron - even so did his eye hiss round the stake of olive-wood.

Terribly then did he cry aloud, and the rock rang around; and we, seized with terror, shrank back, while he wrenched from his eye the stake, all befouled with blood, and flung it from him, wildly waving his arms."

Homer, The Odyssey, Book 9, lines 375-398. At Perseus Digital Library.

The blinded Cyclops removes the door-stone and, sittting at the cave's entrance, lets his sheep and goats out so that he can more easily find the men. But they escape by hiding beneath his huge rams, "well-fed and thick of fleece, fine beasts and large, with wool dark as the violet" (see below). They steal his flocks - adding insult to injury - and drive them to their ship, then sail away. Polyphemos chases after them. and from the shore throws huge rocks at them: "and he waxed the more wroth at heart, and broke off the peak of a high mountain and hurled it at us, and cast it in front of the dark-prowed ship. And the sea surged beneath the stone as it fell". (see below) His efforts prove futile and Odysseus gets away.

This is a key episode in The Odyssey, for as the men sail off Polyphemos calls upon his father Poseidon to avenge him by ensuring that Odysseus never reaches his home:

"... and he then prayed to the lord Poseidon, stretching out both his hands to the starry heaven: 'Hear me, Poseidon, earth-enfolder, thou dark-haired god, if indeed I am thy son and thou declarest thyself my father; grant that Odysseus, the sacker of cities, may never reach his home, even the son of Laertes, whose home is in Ithaca; but if it is his fate to see his friends and to reach his well-built house and his native land, late may he come and in evil case, after losing all his comrades, in a ship that is another's; and may he find woes in his house.' So he spoke in prayer, and the dark-haired god heard him."

The sea god thus prevents Odysseus from returning to Ithaka, and all his men are eventually killed. After ten years of wandering, the hero is only allowed to go home following the intervention of Athena, who pleads his case to her father Zeus. When he finally reaches Ithaka, on another's ship, provided by the Phaeacian king Alkinous (Ἀλκίνους), he finds his palace plagued by "Penelope's suitors", several parasitic nobles determined that one of them should marry his wife Penelope (Πηνελόπη or Πηνελόπεια) and take his place as king (see below).

On the amphora the arms, torsos and legs of Polyphemos and two of the men are filled in with black. The leading man, thought to be Odysseus, is the only figure whose body is painted in outline with a fill of white, clay-based paint, most of which is now worn away. The drawing of his outline appears overworked, perhaps meant to suggest his strength and the speed of the action. The archaeologist Alan Johnston commented on Odysseus' pose: "He kneels on his opponent like a pharaoh." [2] It is notable that here, and on other depictions of Odysseus of the 7th - early 5th century (see images below), he is not wearing a pilos, which was later to be his identifying headgear.

The amphora also features a lion confronting a boar on the shoulder, large intertwining "snakes" formalized as cable patterns, numerous space-filling, orientalizing abstract and floral motifs, and "fretwork" handles.

The blinding scene is shown on a number of other vases of the mid 7th century:

• The "Aristonothos Krater", around 650 BC, found at Caere (today Cerveteri), Etruria, Italy. Signed by Aristonothos, the earliest known signature by a Greek painter/potter (See below).

• A 24.5 cm high fragment of a Proto-Argive krater, circa 650 BC, now in the Argos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. C149. In a panel on the fragment are two naked, bearded men and part of the leg of a third, approaching from the right, and holding the stake above their heads. On the left, Polyephemos, also naked, is shown at around twice the size of the men, lying on a rock or pile of stones. All the figures are shown in profile, with clear, fine, black outlines and light pinkish flesh. Unfortunately, the Argos museum has been closed for some years.

• A "white-on-red", impasto-ware pithos from Etruria, perhaps Caere, attributed to the Workshop of the Calabresi Urn, around 650-625 BC. Height with lid 100.7 cm, diameter 56 cm. Three men blind Polyphemos, who is shown sitting on a stool and at the same scale as the men. All the figures wear short chitons (tunics) and, as in all the depictions mentioned here, headbands. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Villa, Malibu. Inv. No. 96.AE.135 (at getty.edu).

The scene was also depicted on a number of later vase paintings, oil lamps, statue groups, reliefs, mosaics and frecoes into the Roman Imperial period. |

| |

| |

Drawing of the painting depicting the blinding of Polyphemos on the "Aristonothos Krater".

Late Geometric period, around 680-630 BC. Found in a tomb at the Etruscan city

Caere (today Cerveteri), Etruria, Italy. Height 36 cm, maximum diameter 40 cm.

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 172. From the Castellani Collection.

|

The Late Geometric "Aristonothos Krater", dated variously to around 680-630 BC, is inscribed with the earliest known signature by a Greek painter/potter: Ἀριστόνοθος ἐποίσεν (Aristonothos epoiesen, Aristonothos made it; the name means Noble Bastard), thought to be written in the Ionic script of Euboea, although readings of the inscription differ (e.g. Aristonophos, Aristonoos and Ariston of Kos). The only vase attributed to Aristonothos.

Four naked, bearded men with swords slung over their shoulders, shown in profile, advance to the right, holding the stake at waist level and thrusting it into the eye of Polyphemos. The body of a fifth man at the rear (on the far left) is turned in the opposite direction, and he pushes a foot against a wall to add power to the thrust of the stake. The Cyclops, sitting on the ground, is shown in profile at the same scale as the men. His face is now missing. It has been suggested that the object behind (to the right of) Polyphemos is a shelving unit for storing cheese.

The other side of the krater shows warriors on two ships in a sea battle (see Aristonothos).

Image source: Henry Beauchamp Walters, History of ancient pottery: Greek, Etruscan, and Roman, Volume 1 (of 2), plate XVI. Charles Scribner's sons, New York, 1905. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

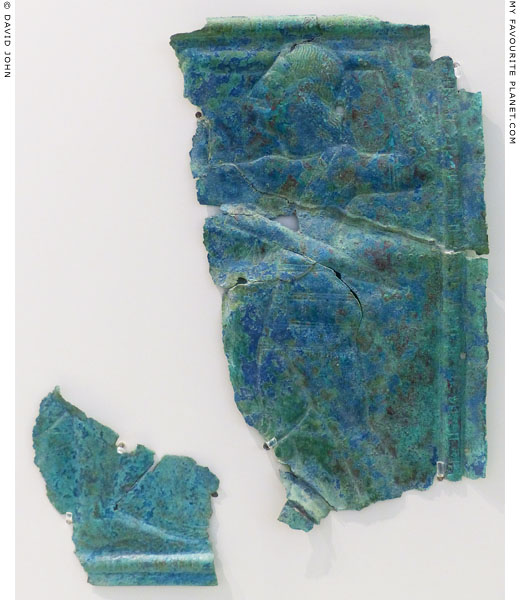

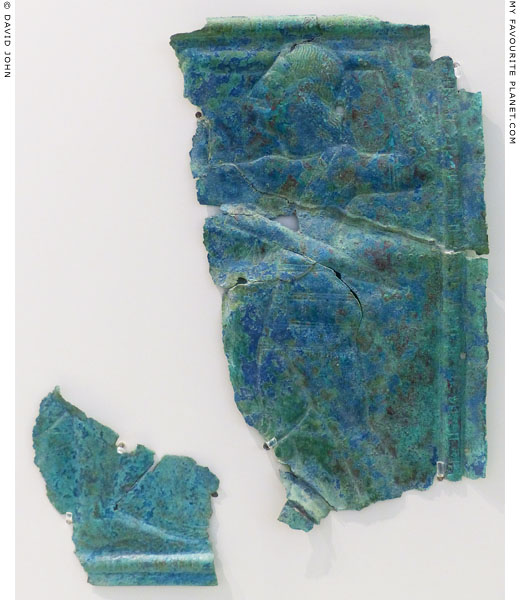

Two fragments of a bronze sheet with a repoussé (hammered) relief. The larger

fragment has a depiction of a man holding above his head an object, described

by the museum label as a sword, presumably because the scabbard hanging

from his shoulder appears to be empty. However, the object looks more like part

of a pole than a sword. The scene may represent Odysseus blinding Polyphemos.

Early 6th century BC. Excavated at the Sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia, Greece.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. Nos. M 108 and M 205.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia. |

| |

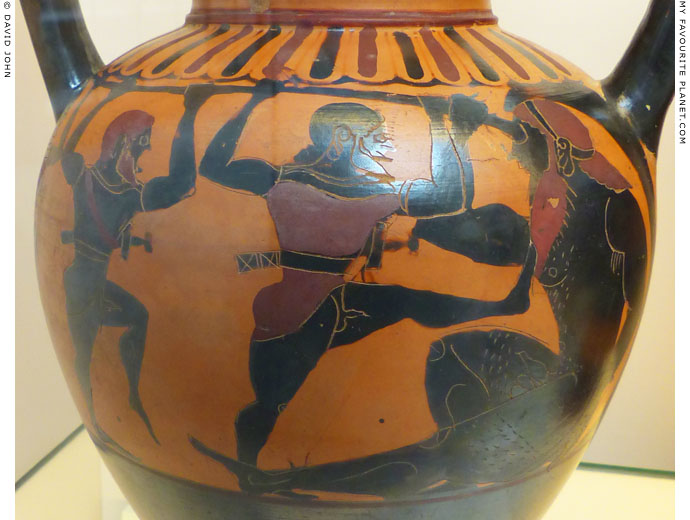

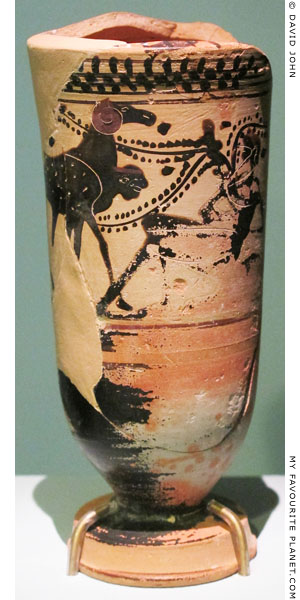

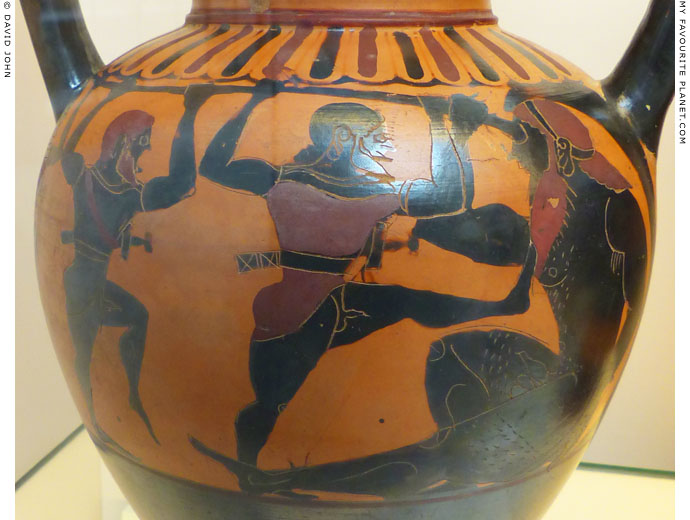

Odysseus and his companions drive a stake into the eye of the Cyclops Polyphemos.

Black-figure neck amphora made in southern Italy around 520 BC.

A "Pseudo-Chalcidian" vase attributed to the Polyphemos Group.

The mariners hold the stake high above their heads as they advance to plunge

it into the eye of the naked Polyphemos. They wear short chitons that do not

cover their genitals. Odysseus presses his raised right foot against the chest

of the seated Cyclops, presumably to prevent him from rising, and perhaps

also as a gesture of triumph over his foe, as on the "Eleusis Amphora" above.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1866.8-5.3 (Vase B 154). Donated by T. S. Smith. |

| |

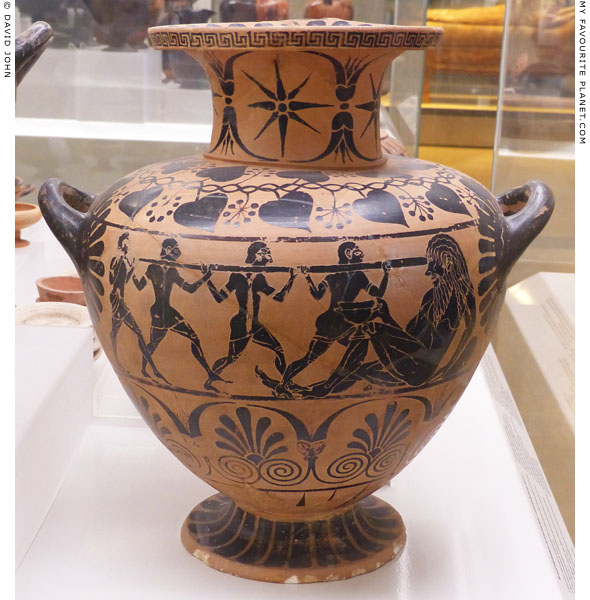

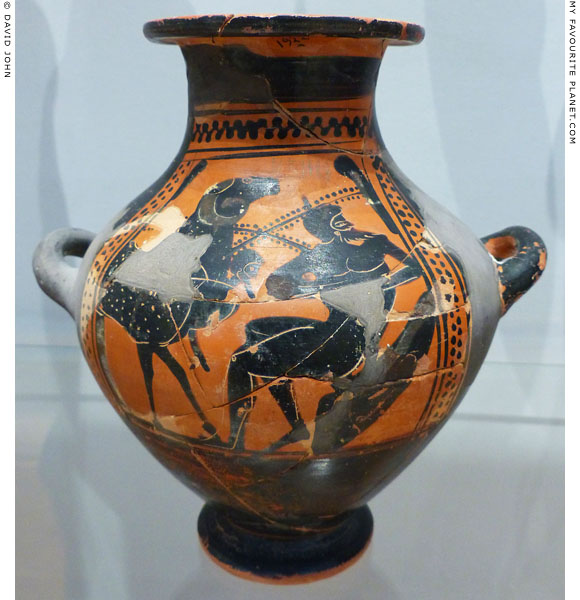

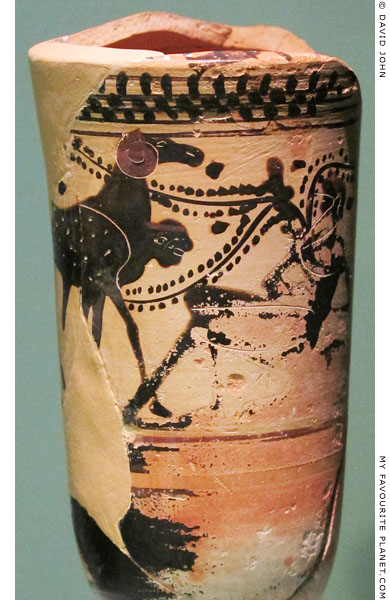

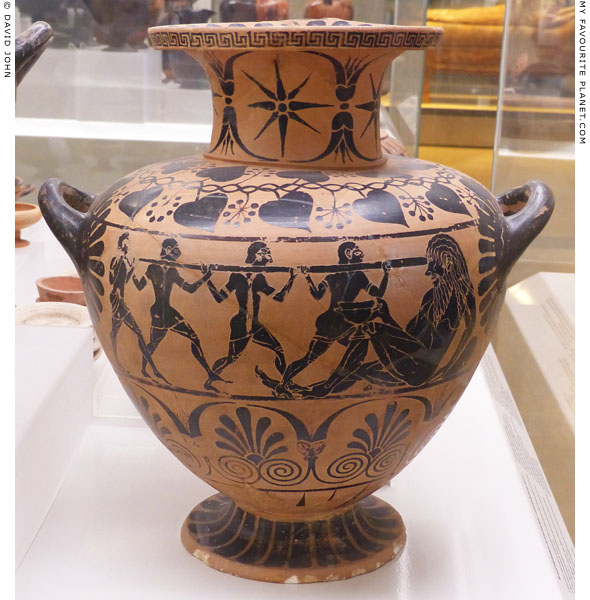

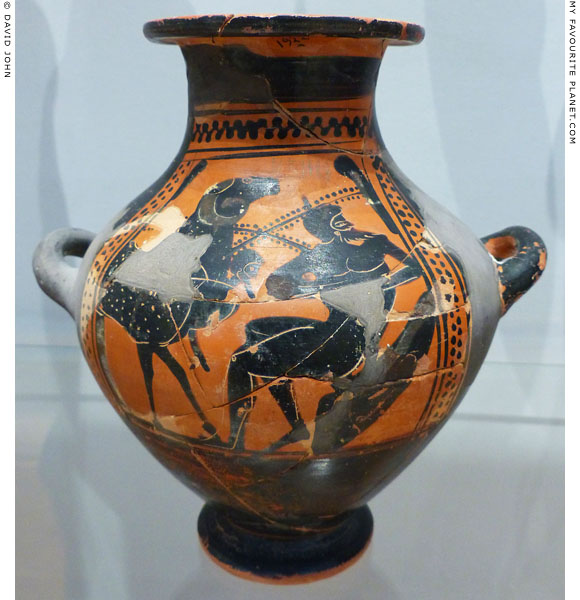

Odysseus and his companions blinding Cyclops Polyphemos.

Etruscan black-figure hydria made in the Etruscan city Caere (today

Cerveteri), around 530-520 BC. Attributed to the Aquila Painter.

The other side shows Herakles shooting the

Centaur Nessos who is abducting Deianeira.

National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia, Rome.

|

Odysseus and his men are shown in profile as a row of four, advancing from the left with the staff, held at shoulder height, entering the eye of Polyphemos, who is also shown in profile, sitting on the ground and holding a large drinking cup. The men all wear short chitons (tunics), while the Cyclops is naked and has long, dishevelled hair and beard.

Odysseus (Ὀδυσσεύς) was known to the Etruscans as Uthuze, from which his Roman name Ulysses may have been derived. The local Greek and Italic variations of his name have given rise to much speculation about its ancient origins and etymology.

The scene is shown in a similar way on a Laconian black-figure cup, attributed to the Rider Painter, around 565-560 BC. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris, Inv. No. 190. The figures on the cup are more detailed than on the Etruscan hydria, with the contours of the hair, musculature and ribs of the naked figures scratched into the black colour. The leading figure of the four holds a cup to Polyphemos' lips. The Cyclops sits on a rock, holding in each hand a leg of one of the men he has just eaten. |

|

| |

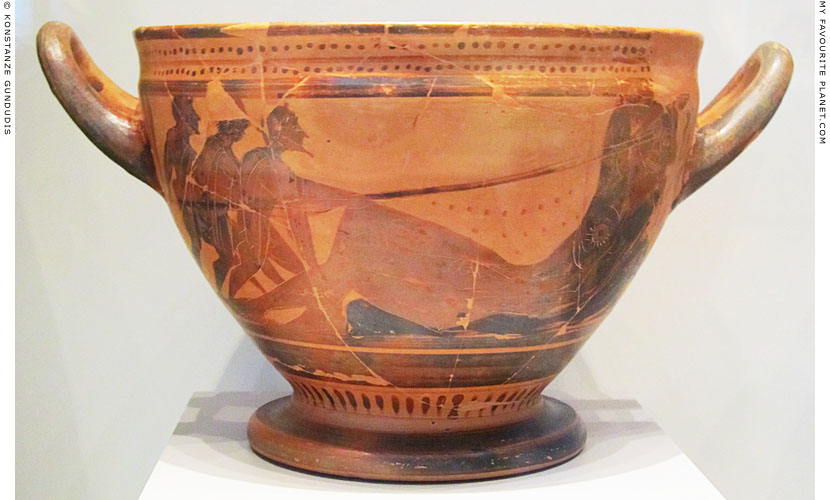

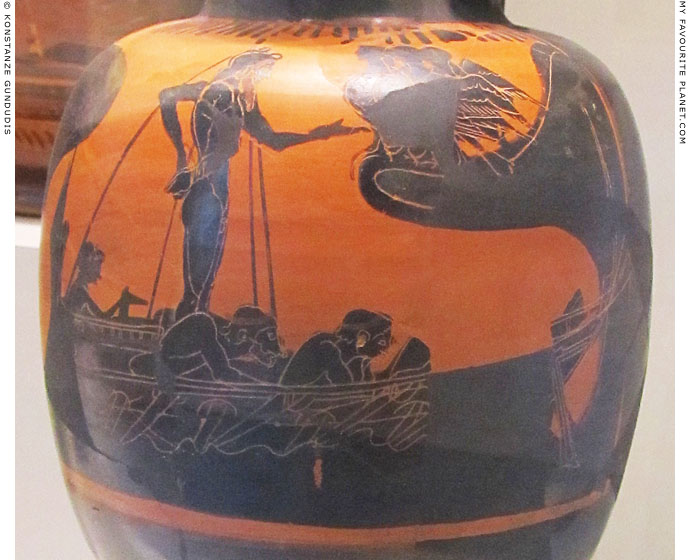

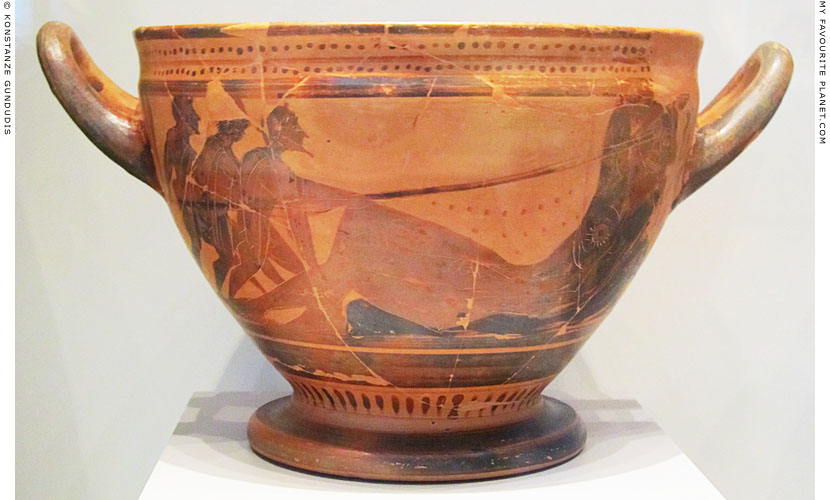

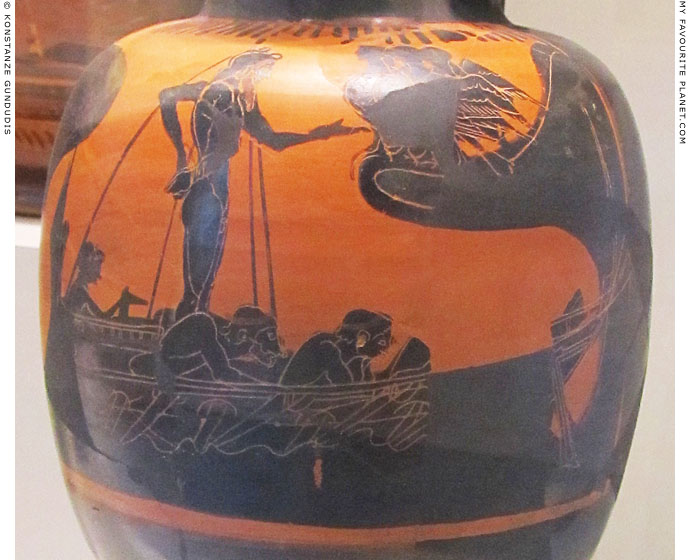

Odysseus and two of his men drive a stake into the right eye of a two-eyed Polyphemos

as the giant Cyclops reclines on a rock, cradling an empty wine cup in his left arm.

Attic black-figure skyphos. Attributed to the Theseus Painter,

490-480 BC. From Boeotia, Greece.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. V.I. 3283.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

Drawing of the blinding of Polyphemos on an Attic black figure oinochoe (οἰνοχόη, wine jug).

6th century BC.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

|

The vase painting shows two overlapping scenes: on the left the stake being heated in the fire; on the right the heated stake is used to blind Polyphemos. Each of the three bearded men is barefoot and wears a petasos (broad-brimmed hat) and a short chiton (tunic). The figure on the left heating the stake has a scabbard in his belt. The lower part of his chiton is decorated with a pattern of dots, as is that of one of the two men blinding Polyphemos. Perhaps both figures represent Odysseus.

The naked, bearded Cyclops, shown at a larger scale than the men, reclines on a rock, cradling a club in his left arm. His normal-looking eye is closed and he is apparently asleep. Above him are wavy branches of the type often shown on vase paintings with Dionysian themes, perhaps indicating Polyphemos' drunken state.

Image source: R. Engelmann and W. C. F. Anderson, Pictorial atlas of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, The Odyssey, Plate VI, Fig. 37, text on page 15. H. Grevel & Co., London, 1892. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

Drawing of an Etruscan wall painting depicting the blinding of Polyphemos.

The third chamber of the Tomb of Orcus at Corneto (ancient Tarqinii), Italy.

"Polyphemus is here depicted as a revolting monster with a huge eye in his forehead.

His name Cuclu (= Cyclops) is inscribed above. Odysseus (inscribed Utusie) unaided is

thrusting into his eye the pointed trunk of an olive tree, to which branches are still attached.

Behind the ogre, in the recesses of the cave, the sheep gaze with interest on the sufferings

of their master, while a goat grazes peacefully on the crag above."

Image and quote: R. Engelmann and W. C. F. Anderson, Pictorial atlas of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey,

The Odyssey, Plate VI, Fig. 38, text on page 15. H. Grevel & Co., London, 1892. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Marble relief from a sarcophagus depicting the blinding of Polyphemos by Odysseus and his men.

Around 180 AD. Discovered in 1733 near the Bastion of San Giovanni, Catania.

Formerly in the Benedictine monastery of San Nicolo [3]. Height 73 cm, width 69.5 cm.

Museo Civico, Castello Ursino, Catania, Sicily. Inv. No. 53. From the Benedictines' Collection.

|

The relief was restored between 1784 and 1801, and several missing or damaged parts were replaced by modern additions, including: the face of the figure on the far left; the right forearm of Odysseus (top, centre); the head and left forearm of the "youth" on the far right. The head of Polyphemos has been so heavily worked that the eye on his forehead is now hardly visible.

In the centre, Odysseus, wearing a pilos (conical cap), a sleeveless chiton (tunic) and cloak, stands over Polyphemos, who wears an animal skin cloak, lying drunk on a rock. His kylix (wine cup) has fallen to the ground beneath his hanging left arm. Next to it sits a sheep. The animal seems rather small, especially considering that Odysseus and his crew later escape from Polyphemos' cave by hiding beneath his giant sheep (see below). On the left two of Odysseus' bearded crewmen stand naked. One appears to be holding an object, perhaps a wineskin, in his right hand. On the right, stands a figure in a short chiton, facing frontally, who the restorers have given the head of a beardless youth.

According to local legends, the 70 metre high Isole dei Cyclopi (the Cyclops Islands) off the coast of Aci Trezza (now named the Riviera dei Cyclopi), north of Catania, are the huge rocks the enraged Cyclops threw at Odysseus and his men as they escaped on their ship (see below).

It is thought that this relief may be a simplified version of a fragmented statue group depicting the blinding of Polyphemos (around 50 BC), discovered in 1957 in a grotto at the Villa of Emperor Tiberius at Sperlonga, on the west coast of Italy (between Rome and Naples), and was used as a basis for the reconstruction. (See also Skylla below.)

Another similar sculpture group was discovered in Ephesus in 1959, in the ruins of the Domitian Fountain (built 92-93 AD), at west end of the Upper "State" Agora. It is thought to have originally formed a pedimental frieze, perhaps on a temple of Dionysus, and to have later been reused to decorate the fountain. [4] The surviving fragments are now displayed in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum, Selçuk. A modern reconstruction of the group has been set up in a pedimental setting outside the museum.

The reconstruction shows the large figure of Polyphemos sitting (rather than lying) in the centre (perhaps in a similar way to the Palazzo Nuovo Polyphemos below), his right arm extended, and thought originally to be taking a wine cup from Odysseus. To the left the smaller figure of Odysseus offering the wine cup (as in the marble statuette below). Behind him two of his companions, one holding a ram. To the right of Polyphemos, three other companions prepare the stake to blind him. The two figures of dead men are thought to have occupied the ends of the pediment. |

|

| |

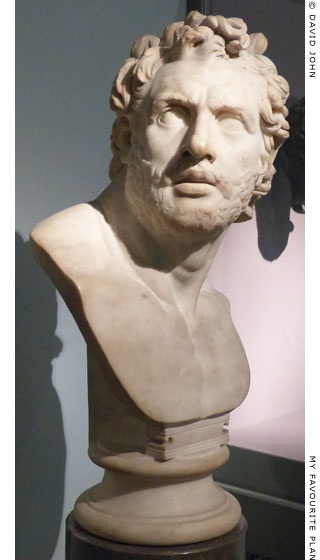

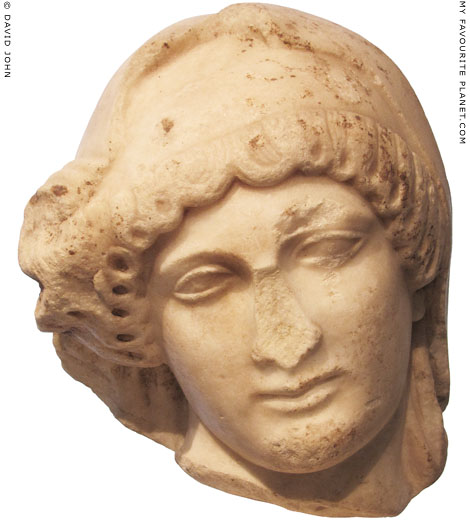

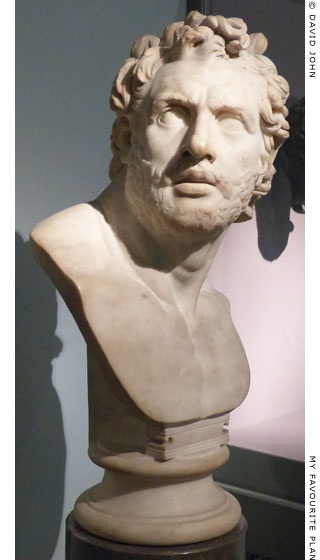

A marble bearded head of a companion of Odysseus,

probably the "wineskin carrier" from a statue group

depicting the blinding of Polyphemos.

Circa 100-150 AD, Roman period copy of a lost Hellensitic original of around 200 BC.

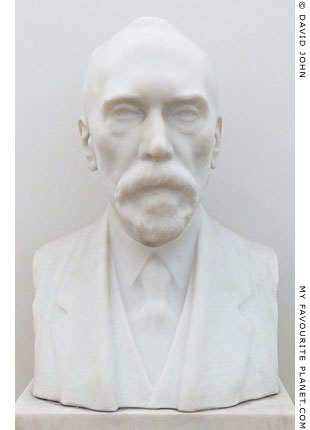

Excavated 1769-1771 by the Scottish painter, antiquarian and antiquities dealer

Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798) in the Pantanello of Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, near Rome.

The nose, lips and bust are modern additions. Height 74 cm.

Another version of this head was found with the body as part of the blinding

of Polyphemos statue group in Sperlonga (circa 50 BC). Although thought to

be by different sculptors, the two heads are remarkably similar, even to the

number and arrangement of the hair curls. [5]

British Museum. Inv. No GR 1805.7-3.86 (Sculpture 1860).

Acquired in 1805 from the Townley Collection. |

| |

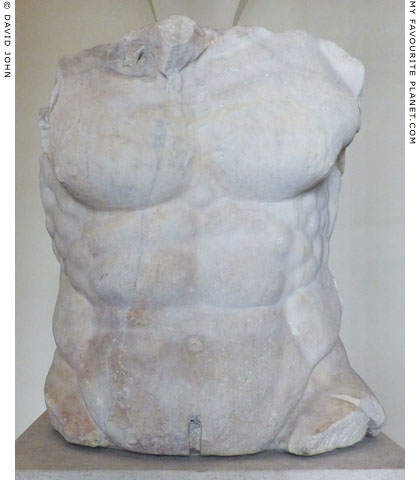

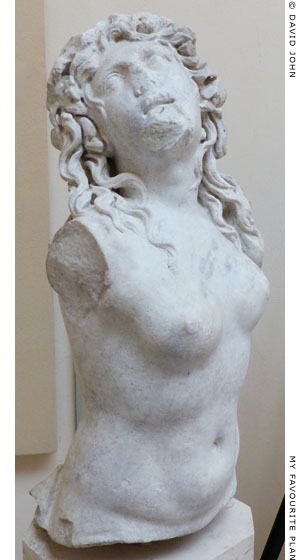

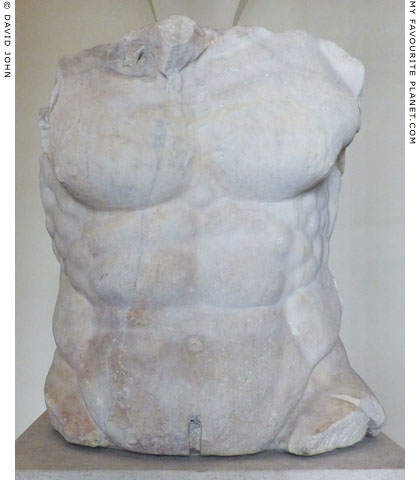

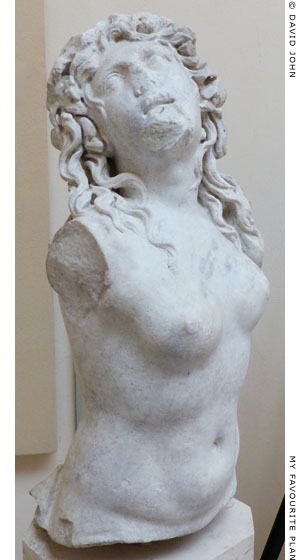

A marble torso, thought to be part of a colossal statue

of Polyphemos from a blinding of Polyphemos group.

Roman period. Previously believed to be from a statue of Hercules,

Polyphemos, or Atlas, it was recently identified as Polyphemos

after comparison with the Sperlonga group (see above).

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 396715.

From the Altemps Collection. |

| |

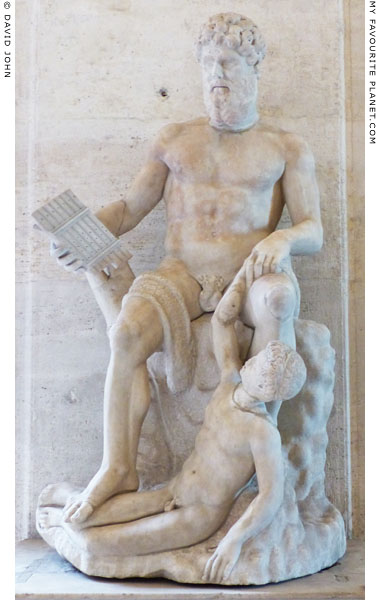

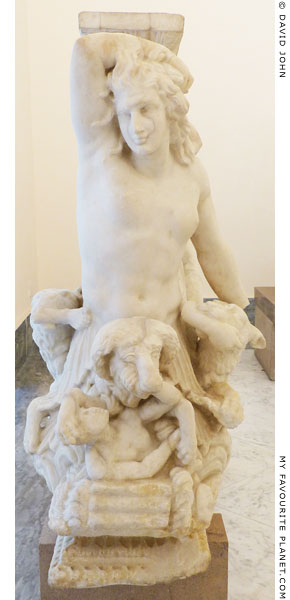

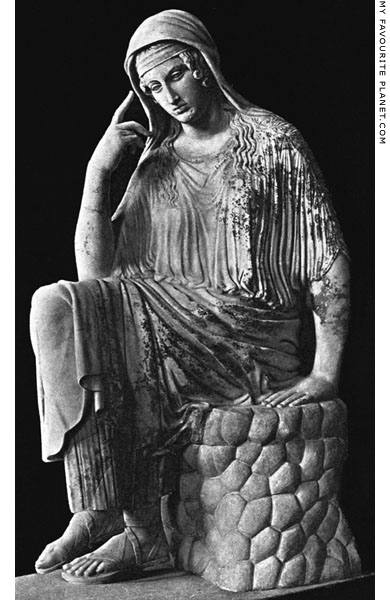

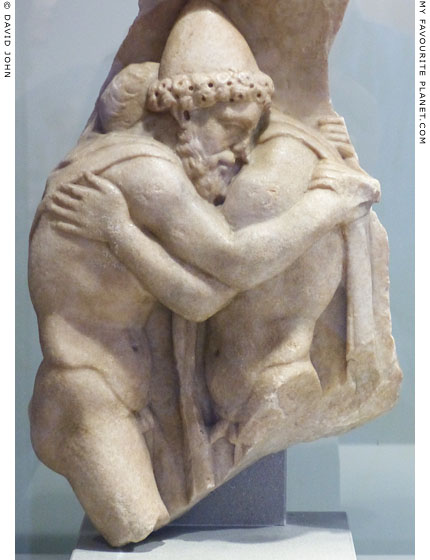

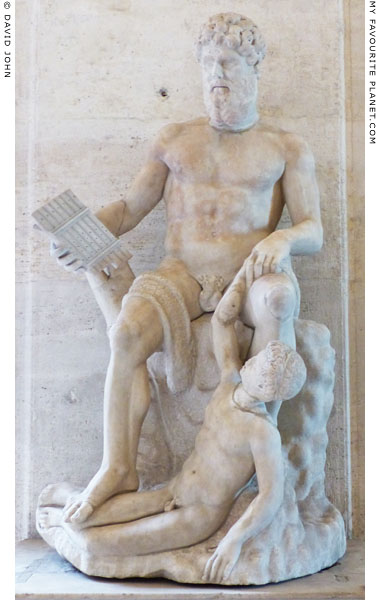

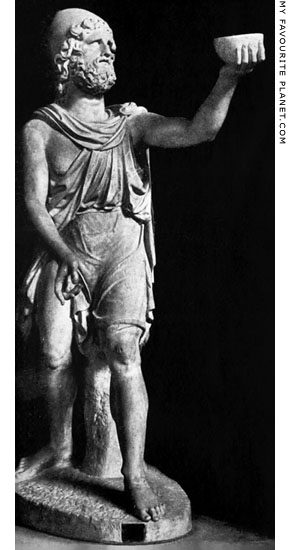

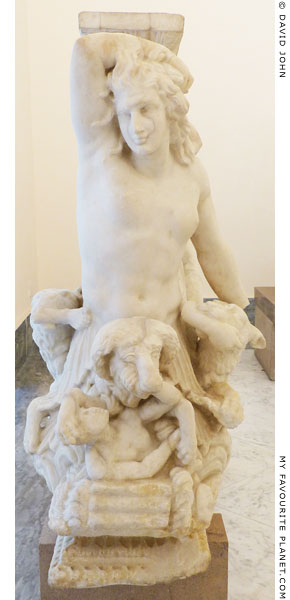

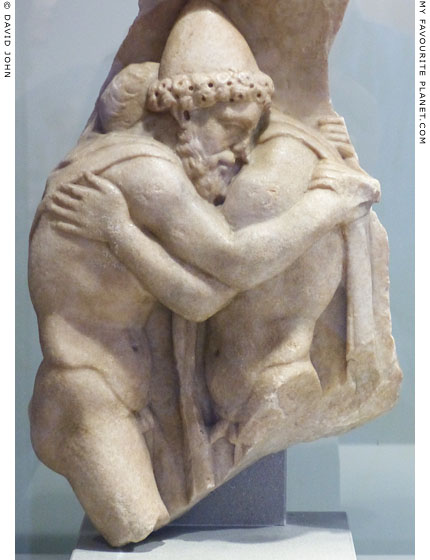

Marble statue group of Polyphemos sitting on a rock

and holding on to one of Odysseus' companions.

2nd - 3rd century AD. Height 157 cm.

The figure of Polyphemos was mistakenly restored as

"Pan and a child", with the addition of a syrinx (Pan pipes).

The Atrium, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 53. |

| |

The statue was found in Rome, although the exact details appear to be unknown; it may have been discovered during building work either at the Basilica of San Stephano on the Caelian Hill, or at the Palazzo Venezia, north of the Capitoline Hill. It was first kept in the Palazzo Venezia, and is known to have been in the Vatican (Inv. No. Boccapaduli 36) after 1550. It was acquired by the Capitoline Collection in 1636, and, according to an inscription on the base, was taken in the same year to the Palazzo Conservatori where it was restored, before being moved to its present location in the mid 18th century.

"Said to have been found near the church of San Stefano Rotondo. Has been restored as the god Pan, and was once the subject of much controversy as to whether the eye in the forehead, was an eye, or a mere flaw in the marble. The hand with the pipes is a restoration. It is work of no artistic merit and doubtful antiquity."

Shakspere Wood, The Capitoline Museum of Sculpture, a Catalogue, page 18, No. 25. Propaganda Fide, Rome, 1872. At the Internet Archive.

The group has been extensively restored:

"The statement that this group was found on the Caelius is insufficiently attested... The right forearm, with the syrinx, and the left hand of the chief figure are restored. The head, which had been broken off, is antique, though it has been retouched, particularly at the top, and belongs to the statue. The head placed by the restorer on the body of the companion of Odysseus is antique, but originally belonged to a vine-wreathed figure of the boy Dionysos.

... Traces of a dark-brown pigment linger on the beard of Polyphemos, of brownish-red on his nude parts, and of greyish-violet on the skins hanging over his knees."

Wolfgang Helbig (1839-1915), Guide to the public collections of classical antiquities in Rome, Volume 1, pages 296-297, The Capitoline Museum, Corridor, No. 409 (35), Group of Polyphemos with a Companion of Odysseus. English translation by James F. and Findlay Muirhead. Karl Baedeker, Lepzig, 1895. At the Internet Archive.

Helbig made the connection between the statue group and the 97 cm high statuette of Odysseus offering the Cyclops a wine cup, now in the Museo Chiaramonti of the Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 1901 (see below). He also drew attention to depictions of the scene in which Odysseus gets Polyphemos drunk before the blinding, on a cinerary urn from Volterra and several terracotta oil lamps (pages 70-72, Museo Chiaramonti, No. 124 (704), Statuette of Ulysses). His Fig. 8 (Fig. 5 in the German edition) is a drawing of a relief on one of the lamps (see image, right), but he gives no further details about it. It is similar to that on a Roman period lamp acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (Inv. No. 83.AQ.377.5) in 1983 from a collection in Germany.

The same drawing of the lamp appeared earlier in R. Engelmann's Pictorial atlas of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, in which it is described as Roman. Engelmann remarked that the Cyclops' eye "seems to be of quite an ordinary shape, whereas literary tradition has represented him as one-eyed. This is, however, the rule in Greek art, and it is only in Roman and Etruscan art that he appears with one or, as is sometimes the case,

three eyes." He did not mention the location of the lamp, merely noting:

"Bought at Naples by Prof. Brunn, of Munich. Ann. d. Inst., 1863, Tav. d'agg., O. 3, p. 430."

R. Engelmann and W. C. F. Anderson, Pictorial atlas of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey,

The Odyssey, Plate VI, Fig. 35, text on page 15. H. Grevel & Co., London, 1892. At the Internet Archive. |

|

Relief on a terracotta oil lamp depicting

Odysseus offering a bowl of wine to

Polyphemos who holds one of the hero's

companions (Odyssey, Book 9, line 345). |

|

| |

A fragmentary multicolured floor mosaic with part of the

scene showing Polyphemos taking wine from Odysseus.

Late 2nd - early 3rd century AD. From Patras, Peloponnese, Greece.

Patras Archaeological Museum.

|

Like the Capitoline Polyphemos statue group above, made around the same time, the polychrome mosaic shows the Cyclops sitting on a rock with his legs apart, facing forewards, his head turned slightly to the viewer's left. With his lowered left hand he holds onto the right arm of one of Odysseus' men (head and left side missing), who is shown around half the size of the Cyclops. With his extended right arm he reaches out to take the bowl of wine offered by Odysseus (see images below). Only the deep, two-handled bowl, the hero's right hand and part of his forearm have survived.

Polyphemos, with a tanned, muscular body, shaggy hair and beard, has two normal eyes plus a third in the centre of his forehead. He wears a grey animal skin, fastened around his left shoulder, falling to the right across his lower torso and upper right thigh. His large right foot is bare. Behind his right leg sits a large, cream-coloured ram, facing left. A grey ram sits, facing left, to the left of his right shoulder, and another grey ram (now headless) sits, facing right, below his right foot. The same scene is shown in a much finer and better preserved, large 4th century AD floor mosaic in the Villa Romana, Piazza Amerina, Sicily. In that work too, Polyphemos has a third in the centre of his forehead. [6]

Surviving parts of the grey background on the right appear to indicate the cave setting, and there are three small sprigs of vegetation. At the top right corner of the scene is part of an inscription: Λ - Α - Ν . ΤΡΟΦ (L - A - N . TROF). The image is surrounded by a border decorated with two rows of geometric patterns, described by the musem label as "dented motif and quirk".

It is a very large mosaic, around 6 metres tall, and the surviving parts show that it was originally an impressively dynamic work of art, although perhaps not of the finest quality. Unfortunately, it is dimly lit and displayed horizontally on the floor of the museum, which makes it difficult to see the details, particularly the Cyclops' face in the centre (photographing it is very tricky). Visitors have to refer to the small drawing displayed next to it (see image, right) to appreciate the composition.

Some other mosaics in the cavernous new archaeological museum in Patras are displayed vertically, so that is easier to appreciate the compositions and imagery (see, for example, a mosaic of Aphdrodite with a mirror), so why not this one too? The design rationale of many museums is that ancient floor mosaics should be displayed on the floor to provide visitors with an impression of how they would have appeared in their original setting (e.g. in a villa or palace). However, this is very unhelpful for those who wish to understand them as works of art.

The new museum is generally under-lit, but otherwise the display of objects and the use of the generously large space is excellent. There is plenty to see, many of the exhibits are very impressive and some delightful surprises. It is definitely an improvement on the cramped environment of the old museum. But whereas the old museum was in the city centre, the new building is on a busy main road out on the eastern end of town, poorly signposted. Its location is outside the area covered by most maps of the city (if you can find one), and the tourist information office has been closed for years. There are frequent buses from the city centre, but it is not easy for first time visitors to discover which bus to take or where to get off.

It would have been interesting to learn more about the topography of the ancient city of Patras, and details of the places where the exhibits were discovered. The museum has included an information board with information (in Greek and English) concerning the description of Patras by Pausanias, who is thought to have visited the city around 170 BC. There is also a map of the modern city centre, marked with the places he mentioned. There is no guide book to the museum, and it is difficult (practically impossible) to find a decent guide book to Patras or publications on its history. There are some interesting historical sites, including the castle, Roman Odeion (see Herodes Atticus) and part of the forum, as well as some older churches, but most of ancient Patras now lies beneath the busy modern city. Locations of many of the archaeological finds, ancient villas and public buildings, are not easy to find or have been built over following rescue excavations. |

|

A drawing of surviving parts of the

Polyphemos mosaic in Patras.

Patras Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

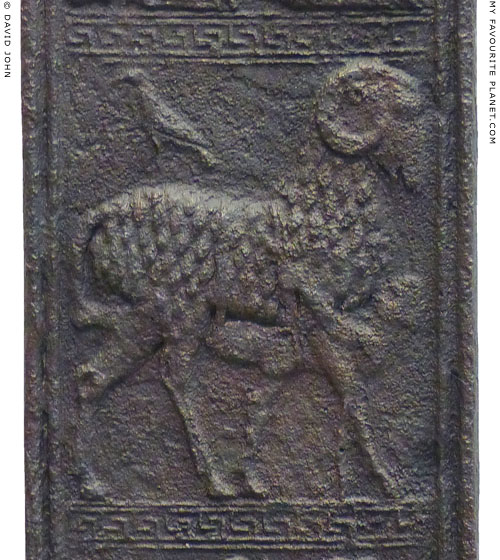

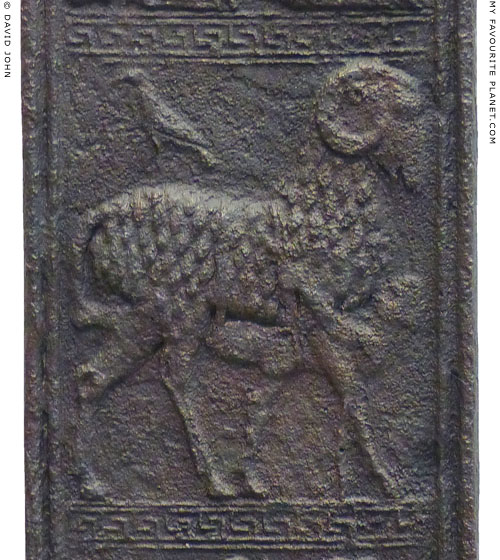

A cast relief of Odysseus escaping from the cave of the blinded

Polyphemos by tying himself beneath one of the Cyclops' huge

rams (Homer, Odyssey, Book IX, lines 425-435), on the leg of a

bronze tripod. Above the ram stands a bird. One of six reliefs in

panels arranged vertically on the tripod leg (see Medusa part 2).

Made in a Corinthian workshop, around 600 BC.

Excavated at the Sanctuary of Olympia, Greece.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. B 7000.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games in Antiquity, Olympia.

|

The figure under the ram is often described as "Odysseus or one of his companions", although it seems most likely that he is the hero Odysseus himself, as the central character and sole survivor of the epic journey in The Odyssey, who would have been the main interest for the artists and their customers and public.

One of the earliest surviving depictions of this scene is on a Middle Proto-Attic, black-and-white-style oinochoe (wine jug), the name vase of the Ram Jug Painter, around 665-640 BC. Found on Aegina. Aegina Archaeological Musem. Inv. No. 566.

There is a lively ceramic statuette of Odysseus under a ram in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Inv. No. 79.AD.37. Height 14.2 cm, width 16.7 cm. Reported to be from Sicily, and perhaps from Enna (northwest Sicily), it is dated to the end of the 6th century BC. Only the head of Odysseus is represented, potruding from between the ram's front legs. Its body was covered by a fleece built up of milk of lime paste applied over the pink clay, but most of it has been worn away. |

|

| |

Odysseus or one of his companions escaping from Polyphemos' cave tied beneath a large ram.

Cast bronze appliqué, which would have been riveted to a fixture or piece of furniture.

From Delphi. Made in a workshop in the northeast Pelponnese, around 540-530 BC.

Details of the figures, particularly the ram's fleece and the way Odysseus lies

along the underside of its belly, holding on by grasping a thong or rope, are

remarkably similar to those on the relief in Olympia above, made around half a

century earlier. It is often tempting to imagine a common prototype for such works.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 2650. |

| |

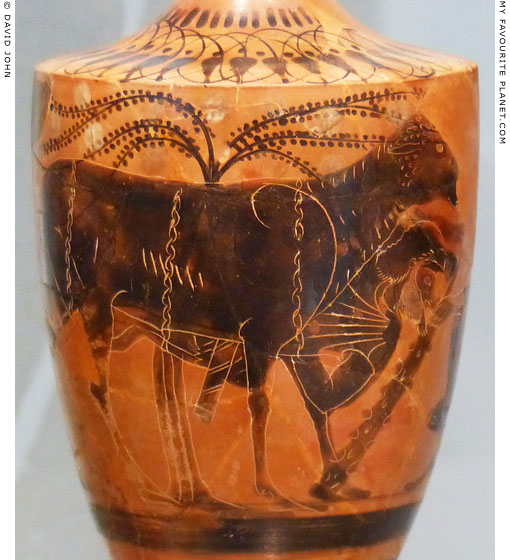

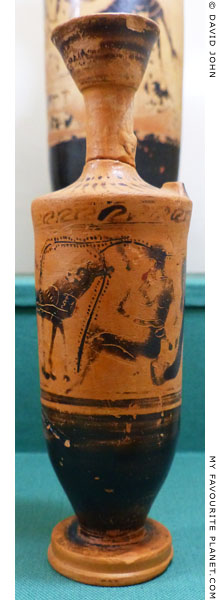

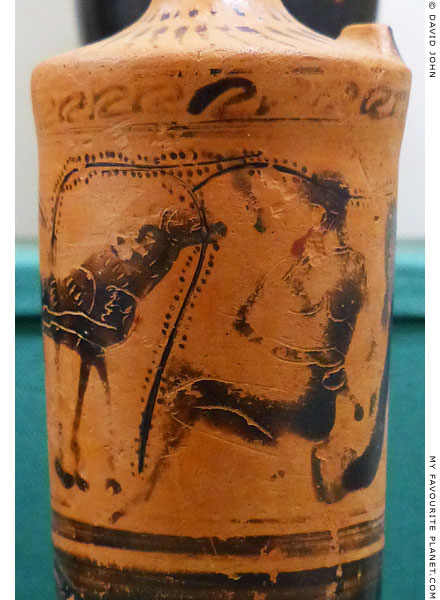

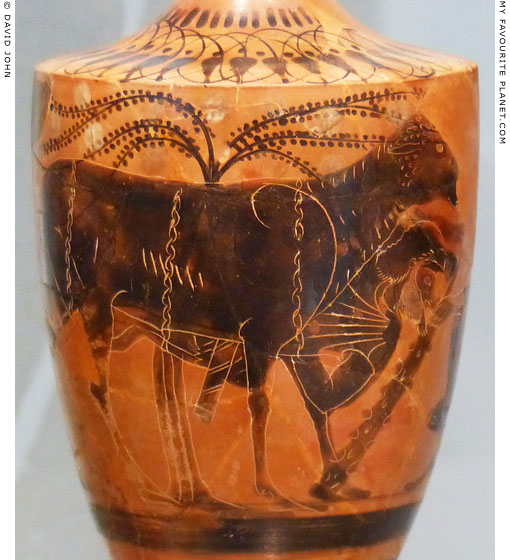

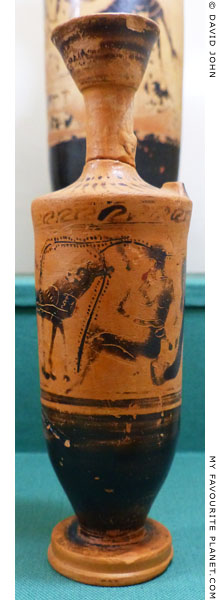

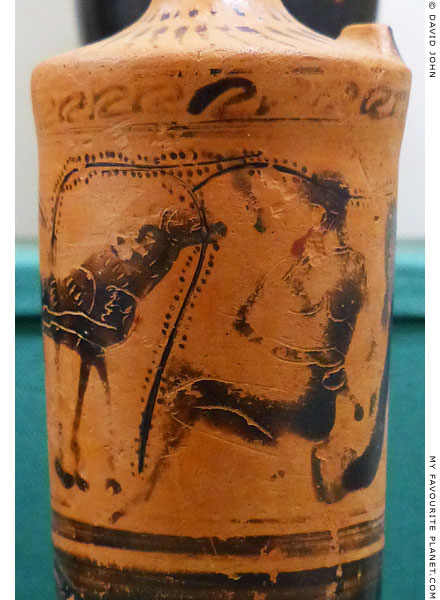

Odysseus or one of his companions escaping from Polyphemos' cave,

tied with three ropes to the underside of one of the Cyclops' rams.

Detail of an Attic black-figure lekythos, 550-501 BC.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1934.249.

Gift of John Davidson Beazley. |

| |

On the right Polyphemos sits on a rock, his head to turned to the right.

On the left Odysseus escapes from his cave, hidden beneath one of his rams.

An Attic black-figure hydria. Found in the "Purification Pit" on the

island of Rheneia (Ῥήνεια), west of Delos (see Mistress of Animals).

Mykonos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. K 31188. |

|

Odysseus escaping from Polyphemos' cave

under a ram (left) as the Cyclops reclines.

An Attic black-figure oinochoe (wine jug)

by the Athena Painter, around 500 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. ABL 260,126

(Vase B 502).

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum. |

|

| |

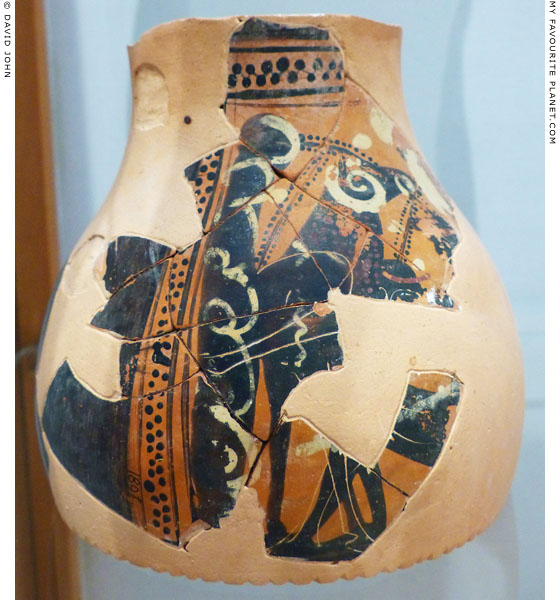

Polyphemos sitting (right), while Odysseus hides beneath a large ram.

Fragments of an Attic black-figure vase.

Found in the "Purification Pit" on Rheneia.

Mykonos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Odysseus, wearing a chiton, escapes from the cave of Polyphemos beneath a large,

docile-looking ram. He may also be wearing a conical pilos cap, although this not clear.

With his left hand the red-bearded hero holds on to the ram's shoulder, and in his

outstretched right hand is what appears to be a sword. Another ram grazes to the

right, and the tentacle-like branches of a vine spread and sway across the background.

Detail of an Attic black-figure pelike. Around 500 BC. From Kerameikos (T HW 195), Athens.

Kerameikos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 4049. |

| |

|

|

|

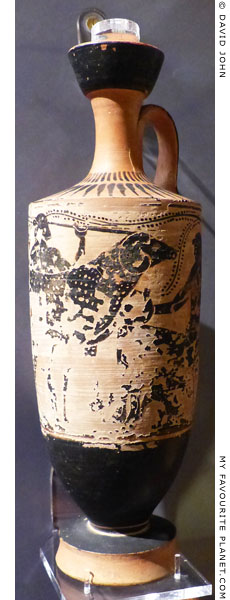

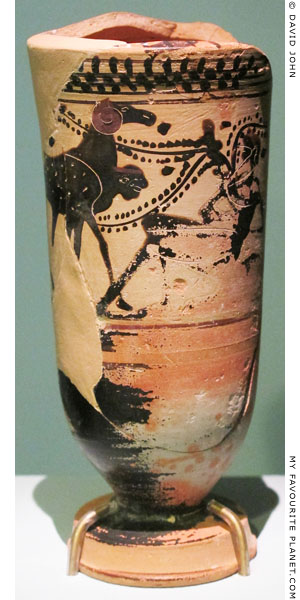

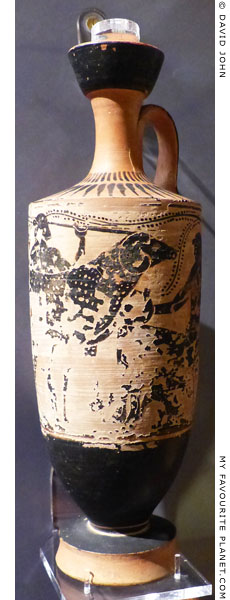

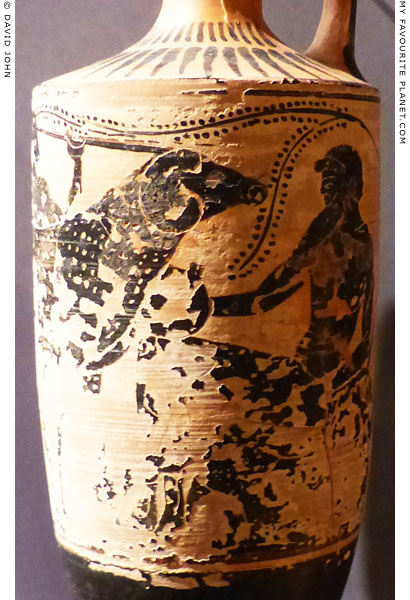

Odysseus or one of his companions, strapped beneath a ram,

escapes from the cave of Polyphemos (seated, right).

Attic black-figure lekythos, 525-475 BC. Preserved height 11.8 cm,

diameter of base 3.6 cm, maximum diameter of body 4.6 cm.

3rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Athens. Inv. No. A7747.

Exhibited during the exhibition The Europe of Greece: Colonies and Coins from the

Alpha Bank Collection (Η Ευρώπη της Ελλάδος Αποκίες και Νομίσματα από τη Συλλογή

της Alpha Bank), Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, 11 April 2014 - 19 April 2015. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Polyphemos (right) sitting in his cave opposite a large ram, under which

is the small scratched figure of Odysseus or one of his companions.

Attic black-figure lekythos, 6th century BC. From Selinous (Selinunte), Sicily.

Museo Civico, Castelvetrano, Sicily. |

|

| |

|

|

|

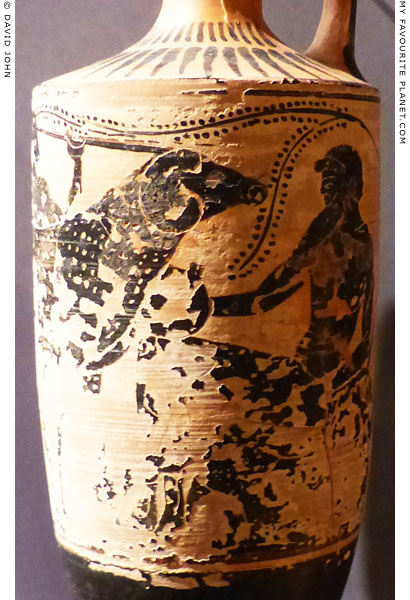

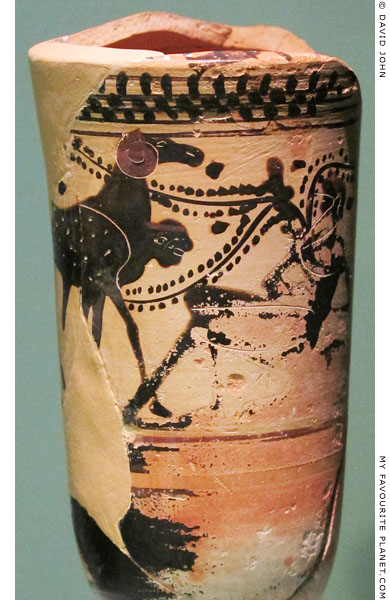

Odysseus or one of his companions, beneath a large ram, escapes from the cave of

Polyphemos, who is seated on the right, holding what may be a large wine cup.

Another member of Odysseus' crew stands behind the ram holding a spear or stake.

An Attic black-figure lekythos, around 500 BC, attributed to the Theseus Painter.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1934.372. |

|

| |

Odysseus escaping from Polyphemos' cave beneath a ram in an emblema of a mosaic floor.

Mid 1st - late 2nd century AD. From the Roman Villa of Baccano, just outside Rome.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome.

|

One of three large polychrome mosaic floors found during excations 1869-1870 at the Roman Villa of Baccano, on mile 16 of the Via Cassia, outside Rome. A lead pipe found there is inscribed with the name of Septimius Geta, brother of Emperor Septimius Severus (reigned 193-211 AD), leading scholars to believe that the villa belonged to the imperial family of the Septimii.

Excavation notes mention that the mosaic floor to which this scene belongs originally had 32 emblemata (mosaic panels). However, it has been restored with 25 small square panels (5 rows of 5), in which only parts of 20 mosaic scenes have survived. The picture panels are separated by a grid frame of double plaits on a black background. Most of the images are of mythical episodes or figures, including Muses, Leda, Ganymede, Marsyas, while others have a marine theme, including an emblema with different kinds of fish. All the emblemata were made using the fine opus vermiculatum (worm-like work) technique, but they vary in style and quality. It is thought that the panels were reused from other mosaics dating from the mid 1st to the late 2nd century AD.

The subject of the Polyphemos panel is not immediately clear, as the pictorial elements seem to be reduced almost to abstraction, as in early 20th century European painting. This may be a result of restoration work. It takes a while to recognize the central naked figure as the Cyclops standing at the mouth of his cave, frisking a white ram as it walks out with Odysseus clinging to its underside. |

|

| |

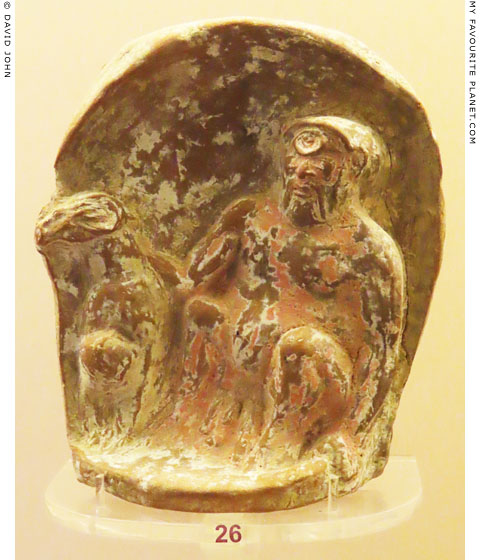

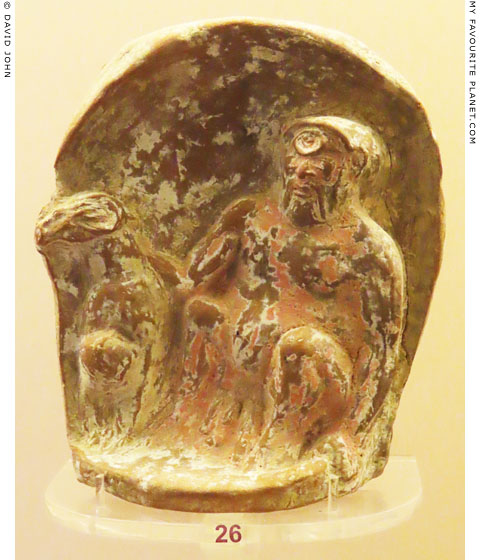

A small ceramic plaque with a relief of Polyphemos, seated right,

and a large ram, under which can be seen the head of Odysseus.

From an inhumation burial of a youth, Macri Langoni T 25 (52).

475-450 BC. Found during excavations in the cemetery at Macri

Langoni, near the ancient city of Kamiros, western Rhodes.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum.

|

This unusual object is exhibited among several other finds from tombs at Macri Langoni, at the back of a large display case in one of the dark Medieval rooms of the Rhodes Archaeological Museum, built between 1440 and 1481-1489 as a hospital by the crusading knights of the Order of Saint John. Details of the once brightly painted relief are now difficult to make out in the gloom. The photo above has been brightened considerably with the help of computer software.

The plaque is shaped like a cave and the space behind the figures is concave. On the right side the bearded giant Polyphemos, naked and with a pot belly, sits on the ground at the cave's mouth. He appears to have two normal eyes, or at least eyelids, as well as a much larger open eye in the middle of his forehead. His left arm is by his side and the hand clutches the side of the plaque's base. With his right hand he feels the back of the ram, searching for Odysseus and his men to prevent them escaping from his cave. The ram stands frontally with its head turned to the left, and between its front legs potrudes the smaller-scale head of Odysseus as he hangs from its underside. |

|

| |

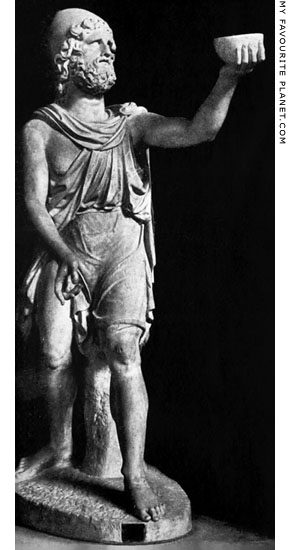

A Roman marble statuette of Odysseus hiding under a ram in Polyphemos' cave.

An engraving published by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in 1767.

Luna marble. Height 78 cm, width 73 cm, depth 35 cm.

From the Albani Collection. Inv. No. 438. Now in the Torlonia Collection, Rome. |

|

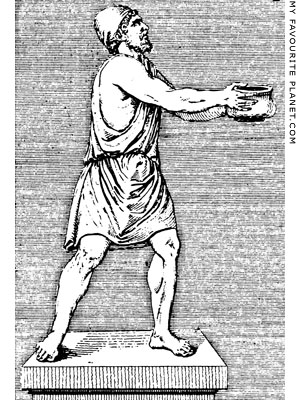

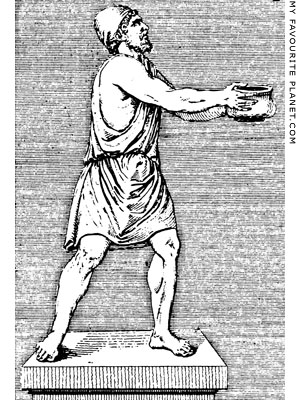

A marble stattuette of Odysseus

offering a bowl of wine to

Polyphemos with both hands. |

|

| |

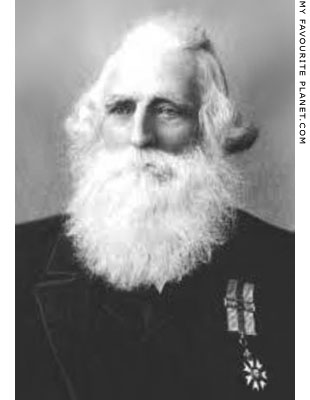

The statuettes of Odysseus hiding under a ram and Odysseus handing wine to Polyphemos, as well as other ancient artworks relating to Homeric tales, were first described and illustrated by the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768).

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Monumenti antichi inediti spiegati ed illustrati da Giovanni Winckelmann, Volume I (Unedited antique monuments, described and illustrated by Giovanni Winckelmann). Rome, 1767. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Engravings: Odysseus handing wine to Polyphemos, plate 154; Odysseus hiding under a ram, plate 155.

Much of the Albani Collection was later sold off and the works are now dispersed among many collections and museums around the world (for example, the Capitoline Museums, Naples, Dresden and the Louvre). However, several works are still in the private collection of the Villa Albani which has belonged to the Torlonia family since 1866. Kept in storage for many years, plans were set in motion in 2016 to finally exhibit the works to the public.

A photograph and short description of Odysseus hiding under a ram also appeared in a catalogue of works in the Torlonia Museum by Carlo Lodovico Visconti (1818-1894).

Carlo Lodovico Visconti, I monumenti del Museo Torlonia riprodotti con la fototipia, descritti da Carlo Lodovico Visconti, Volume II, Tavole, Tavolo CXII ("Ulisse soto il montone"). Tipografia Tiberina di F. Setth, Rome, 1885. At the Arachne website, University of Köln Archaeological Institute.

A similar sculpture of Odysseus under a ram, dated to the 2nd century AD, is exhibited in the Aldobrandini Room of the Doria Pamphili Gallery, Rome.

A Flavian era (69-96 AD) marble statuette of Odysseus offering a wine cup to Polyphemos, thought to be a copy of a late Hellenistic original, is in the Museo Chiaramonti of the Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 1901 (see photo, right). Both this statuette and that above were probably part of groups depicting the blinding of Polyphemos. |

|

The "Chiaramonti Odysseus", a marble

stattuette of Odysseus offering a bowl

of wine to Polyphemos with his raised

left hand.

Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums,

Rome. Inv. No. 1901. Image source:

Guy Dickens, Hellenistic sculpture,

Fig. 35, page 50. Clarendon Press,

Oxford, 1920. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

An Etruscan alabaster cinerary urn with a relief of Odysseus and his companions

escaping from Polyphemos in their ship (Odyssey, Book 9, line 473).

On the lid a statue of a young man, the deceased, reclines on a

couch, resting on his left elbow, and holds a bowl in his right hand.

The high relief on the front of the casket is one of the few surviving ancient depictions of the

dramatic scene in which Odysseus (known to the Etruscans as Uthuze) and his companions

escape fom Polyphemos in their ship, pursued by the enraged Cyclops. See details below.

200-50 BC. From Volterra, Etruria, Italy. Height 92.5 cm, width 77 cm, depth 26 cm.

Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Inv. No. H III C.

For further information about the Etruscan cinerary

urns in the Leiden museum, see Homer part 2. |

| |

The relief on the front of the Etruscan cinerary urn in Leiden.

|

On the far left, the bearded Polyphemos stands at the mouth of his cave about to throw a large rock to the right at Odysseus' departing ship with his raised right hand. With his lowered right hand he clutches the part of his cloak which covers his genitals, as if he has just thrown the garment around him in his haste to catch up with the escaping men. He also wears stylish boots or high sandals. It is notable that he has two eyes, neither of which appears injured, his pose is quite heroic, and he appears almost godlike - similar to depictions of Zeus with his thunderbolt or Poseidon with his trident. He is hardly the savage monster described by Homer. Like the other figures in the relief, his face betrays little sign of emotion, although the expression of the goddess may be one of grim determination, and Odysseus and his men look deadly serious. Behind his legs stand two of his sheep, which appear quite small, even in comparison to Odysseus and his men, who are shown at a slightly smaller scale than Polypephemos and the winged female figure.

This winged figure is thought to be an Etruscan goddess, probably Menrva, the equivalent of the Greek Athena and Roman Minerva, although she is not usually depicted with wings in Etruscan art. In Homer's The Odyssey, Athena constantly helps and supports Odysseus. She also acts as his advocate among the gods, particularly pleading to Zeus the case for his safe return home and against the vengeance of Poseidon, and intercedes on the hero's behalf. However, Homer does not mention Athena helping him in his escape from Polyphemos. It may be that she played a role in another version of the tale, or her participation in the action is an artist's invention, perhaps representing her assistance in a spiritual sense. Odysseus later tells Athena how her support lends him the courage for his most daring undertakings:

"... and stand thyself by my side, and endue me with dauntless courage, even as when we loosed the bright diadem of Troy. Wouldest thou but stand by my side, thou flashing-eyed one, as eager as thou wast then, I would fight even against three hundred men, with thee, mighty goddess, if with a ready heart thou wouldest give me aid."

Homer, The Odyssey, Book 13. At Perseus Digital Library.

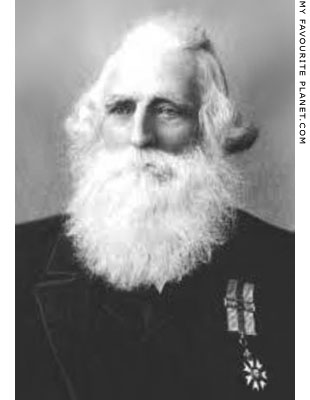

The Dutch archaeologist L. J. F. Janssen (1806-1869; curator of the Leiden museum, 1835-1868) referred to the figure as a "so-called Fury", indicating that he was not entirely convinced by current theories, while some scholars have suggested that she may be the Etruscan winged daemon Vanth, who was usually associated with death and the Underworld. Despite the notion of innumerable versions and variations of the tales associated with Odysseus which may predate the age of Homer or even that of the Trojan wars, it is difficult to imagine how the Etruscans introduced either a Fury or Vanth into this tale. It has been suggested that the Fury is further fuelling Polyphemos' rage caused by the blinding and the taunting words shouted by Odysseus from the ship. Since there are few surviving written vestiges of Etruscan mythology or literature, it also seems impossible to prove one way or the other.

An almost identical figure appears on another Etruscan urn in Leiden, depicting Odysseus, Penelope and her suitors (see below), and in that context she seems most likely to be Menrva/Athena. Here she stands between Polyphemos and the ship, blocking the Cyclops' view and preventing his rock from hitting the vessel by stretching her cloak between her hands. In her raised right hand she also holds a sword. She wears a cap similar to Odysseus' conical pilos, a sleeved and girdled chiton (tunic) over a knee-length peplos (or whatever was its Etruscan equivalent), and diagonal bands, presumably to support her wings, crossed over her breast and fastened together by a rosette (see Athena with the cross-banded aegis).

To the right, the sturdy ship, which takes up around two thirds of the surface of the relief, sails to the right with a billowing sail over a very solid-looking row of waves. Aboard are six men, all dressed similarly and wearing pilos caps, but each has slightly different facial features. Their poses are tense and they all look back towards Polyphemos. One man steers with the rudder and two sit at the oars, although four oars are shown, as well as five shields fixed to the starboard side. Behind them stand another three men, shields raised and poised for action. The figure on the left, with the lower part of his face obscured by his shield, is probably Odysseus. He is the only bearded man aboard, and the only figure in the relief with his back to the viewer. The middle figure holds his shield high as if anticipating an "incoming" rock from above.

See: Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen, De etrurische grafreliëfs uit het Museum van Oudheden te Leyden, No. 34, pages 24-25 and plate XIX. H. J. Brill, Leiden, 1854. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

A similar relief on a 4th century BC Etruscan cinerary urn from Volterra, now in the Florence Archaeological Museum, shows Odysseus tied to the mast of his ship as he passes the land of the Sirens (see below).

Odysseus (Ulysses) and his companions' terrible encounter with Polyphemos and their escape by ship were also described by the Roman poets Virgil (70-19 BC) in The Aenid (Book 3, lines 580-685) and his younger contemporary Ovid (43 BC - 17/18 AD) in Metamorphoses (Book 14). Both placed the home of Polyphemos and "the whole tribe of Cyclopes... that brotherhood of Etna" (Virgil) on the east coast of Sicily around Mount Aetna, "that mountain piled on Typhoeus’ giant head, and the Cyclops’ fields, that know nothing of the plough’s use or the harrow, and owe nothing to the yoked oxen". (Metamorphoses, Book 14, lines 1-5)

Both poets also wrote that in his hasty escape from Polyphemos, Ulysses had left one of his men behind. The stranded Achaemenides finally managed to get away by hailing a passing ship, which turned out to be that of the Trojan prince Aeneas. In Ovid's version, Achaemenides accompanied Aeneas to Carthage. Eventually arriving with the Trojan refugees at Caieta (modern Gaeta) in southern Italy, he related his ordeal to Macareus of Neritos, another of those who had escaped with Ulysses, but had then left him and settled there.

"Macareus now recognised Achaemenides, among the Trojans, he, who had been given up as lost, by Ulysses, long ago, among the rocks of Aetna. Astonished to discover him, unexpectedly, still alive, he asked: 'What god or chance preserved you, Achaemenides? Why does a Trojan vessel now carry a Greek? What land is your ship bound for?'

Achaemenides, no longer clothed in rags, his shreds of clothing held together with thorns, but himself again, replied to his questions, in these words:

'If this ship is not more to me than Ithaca and my home, if I revere Aeneas less than my father, let me gaze at Polyphemus once more, with his gaping mouth dripping human blood. I can never thank Aeneas enough, even if I offered my all. Could I forget, or be ungrateful for, the fact that I speak and breathe and see the sky and the sun's glory? Aeneas granted that my life did not end in the monster's jaws, and when I leave the light of day, now, I shall be buried in the tomb, not, indeed, in its belly.

I watched as Cyclops tore an enormous boulder from the mountainside, and threw it into the midst of the waves. I watched again as he hurled huge stones, as if from a catapult, using the power of his gigantic arms, and, forgetting I was not on board the ship, I was terrified that the waves and air they displaced would sink her.

When you escaped by flight from certain death, Polyphemus roamed over the whole of Aetna, groaning, and groping through the woods with his hands, stumbling, bereft of his sight, among the rocks. Stretching out his arms, spattered with blood, to the sea, he cursed the Greek race like the plague, saying: "O, if only chance would return Ulysses to me, or one of his companions, on whom I could vent my wrath, whose entrails I could eat, whose living body I could tear with my hands, whose blood could fill my gullet, and whose torn limbs could quiver between my teeth: the damage to me of my lost sight would count little or nothing then!"

Fiercely he shouted, this and more. I was pale with fear, looking at his face still dripping with gore, his cruel hands, the empty eye-socket, his limbs and beard coated with human blood. Death was in front of my eyes, but that was still the least of evils. Now he’ll catch me, I thought, now he'll merge my innards with his own, and the image stuck in my mind of the moment when I saw him hurl two of my friends against the ground, three, four times, and crouching over them like a shaggy lion, he filled his greedy jaws with flesh and entrails, bones full of white marrow, and warm limbs.

Trembling seized me: I stood there, pale and downcast, watching him chew and spit out his bloody feast, vomiting up lumps of matter, mixed with wine. I imagined a like fate was being prepared for my wretched self. I hid for many days, trembling at every sound, scared of dying but longing to be dead, staving off hunger with acorns, and a mixture of leaves and grasses, alone, without help or hope, left to torture and death.

After a long stretch of time, I spied this ship far off, begging them by gestures to rescue me, and ran to the shore and moved their pity: a Trojan ship received a Greek!'"

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 14, lines 154-222. Translated by A. S. Kline, 2000. At the Ovid Collection, University of Virginia. |

|

| |

Marble relief of masks of Polyphemos and the Nereid (sea nymph) Galatea.

Polyphemos' unrequited love for Galatea (Γαλάτεια, she who is milk-white), the personification

of sea foam, was the subject of myth and poetry. The Cyclops, with a third eye on his forehead,

is shown as a rustic figure with a crown of wheat and a syrinx (Pan pipes). The head of Galatea

appears above waves and a leaping dolphin.

Late 1st century AD. Found in 1931 at the theatre of the sanctuary

of Diana Nemorensis (Diana of Nemi), Valle Giardino, Nemi, near Rome. Luni marble.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 112157. |

| |

A marble relief of Odysseus (known to the Romans as Ulysses) and the Sirens.

The left side of a panel from the sarcophagus of the Roman knight (eques Romanus)

M. Aurelius Romanus who, according to the inscription in the centre of the panel,

died at the age of seventeen. The relief on the right side shows a bust of the

young man flanked by two cupids and two seated philosophers.

Late Severan age (193-235 AD). Found on the Via Tiburtina, Rome.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome.

|

In Homer's Odyssey, Book 12, the divine sorceress Circe (Κίρκη) warned Odysseus of the perils awaiting him and his men on the next part of their sea voyage. These included the Sirens, the Clashing Rocks, and the monsters Skylla (see below) and Charybdis (a whirlpool).

The enchanting singing of the Sirens (singular, Σειρήν, Seiren; plural, Σειρῆνες, Seirenes) drew seafarers to shipwreck and death on the rocky shore of their island, and Circe knew that Odysseus would not be able to resist the temptation to hear their song for himself. He followed her advice to have his companions wear earplugs of beeswax while they rowed past the Sirens' island, having had himself tied to the ship's mast so that he would not attempt to follow the bewitching music.

Homer wrote that there were two Sirens, but does not describe or name them individually. The earliest known description of them as "winged maidens, virgin daughters of Gaia", appears in Euripides' play Helen (Ἑλένη, line 167), first performed at the Dionysia in Athens in 412 BC. The works of later writers differ in their accounts of their parentage, numbers (between two and four) and names. In Greek, Etruscan and Roman art they are depicted as part woman, part bird, with several variations of forms, though always with human heads.

The Roman mythographer Hyginus (see note in Homer part 2) summarized some of the versions of the myths concerning the Sirens:

"The Sirens, daughters of the River Achelous and the Muse Melpomene, wandering away after the rape of Proserpina [Persephone], came to the land of Apollo, and there were made flying creatures by the will of Ceres [Demeter] because they had not brought help to her daughter. It was predicted that they would live only until someone who heard their singing would pass by. Ulysses proved fatal to them, for when by his cleverness he passed by the rocks where they dwelt, they threw themselves into the sea. This place is called Sirenides from them, and is between Sicily and Italy."

Hyginus, Fabulae, sections 100-149, section 141, Sirens. At the Theoi Project.

In this relief three Sirens are shown with human heads, arms and bodies, and the tails, legs and feet of birds. Standing on rocks in the sea, they wear cloaks and hold musical instruments. Odysseus, wearing a pilos and chiton, stands at the mast of his ship while two of his companions row past the rocks.

The scene on the sarcophagus may have been from one of the deceased young man's favourite tales, or have had some special significance for the family. Such motifs may have been popular for funerary art as they not only reflected the literary and artistic tastes of the families, but also illustrated heroic victories over death (see also the "Recognition of Paris" relief in Homer part 2).

Several scholars, ancient and modern, have attempted to trace Odysseus' route around the Mediterranean and identify the locations of his individual adventures. For many his encounters with the Sirens, Skylla and Charybdis occurred in the narrow Strait of Messina, between Messine (Μεσσήνη; until around 494 BC known as Zankle, Ζάγκλη [7]; today Messina), at the northeast tip of Sicily and the "toe" of the "boot" of the Italian mainland (see photo below). The three kilometre wide strait was evidently feared by ancient mariners because of its currents, whirlpools and heavy storms. Pausanias added swarms of monsters to its dangers.

"The sea in fact at this strait is the stormiest of seas; it is made rough by winds bringing waves from both sides, from the Adriatic and the other sea, which is called the Tyrrhenian, and even if there be no gale blowing, even then the strait of itself produces a very violent swell and strong currents. So many monsters swarm in the water that even the air over the sea is infected with their stench. Accordingly a shipwrecked man has not even a hope left of getting out of the strait alive. If it was here that disaster overtook the ship of Odysseus, nobody could believe that he swam out alive to Italy, were it not that the benevolence of the gods makes all things easy."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 25, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

Aerial view of the Strait of Messina, viewed from the southwest, above Messina

at the northeast tip of Sicily. The sea looks quite harmless from up here. |

| |

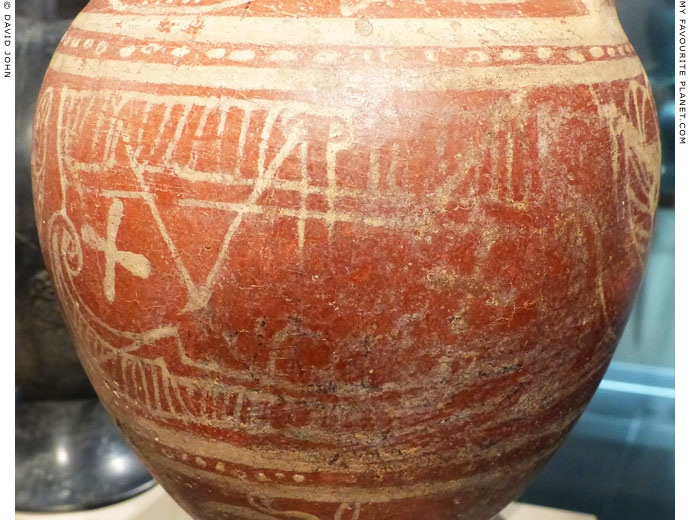

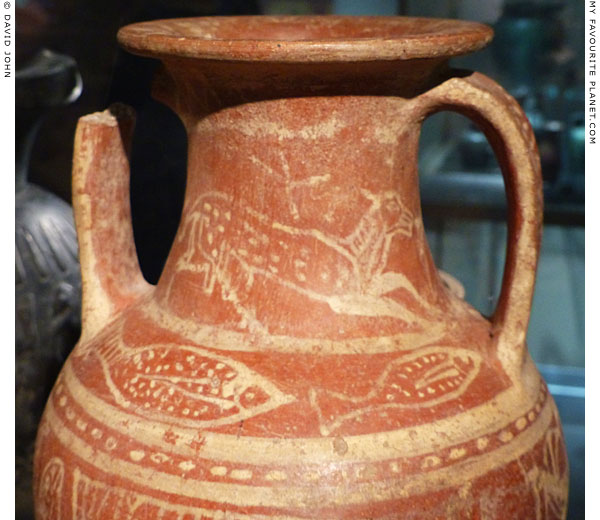

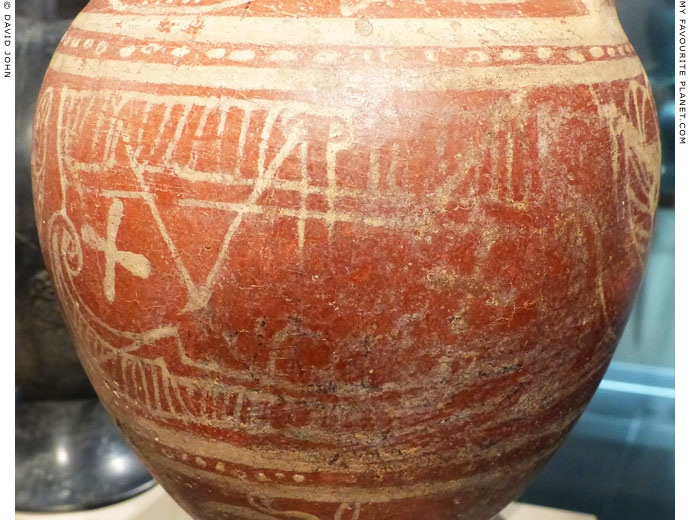

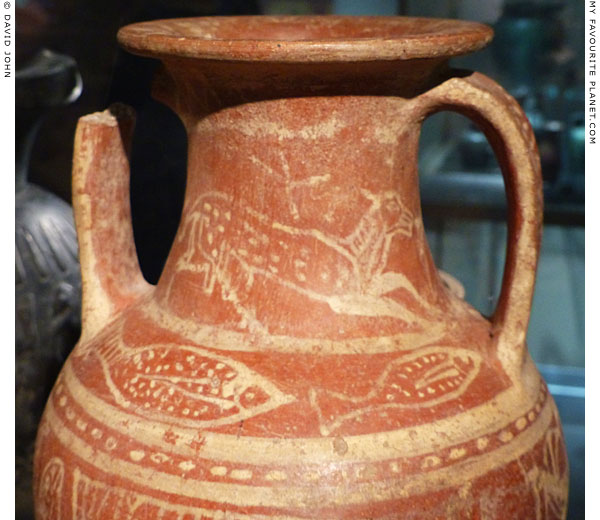

Detail of an Etruscan "white-on-red" impasto-ware amphora with a painting of a man sitting in a ship.

Around 630 BC. From Tomb B 17, Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri (ancient Caere, Etruria).

Attributed to the Painter of the Siren Attachment (Pittore della Sirena-Assurattasche).

Height 44.5 cm, maximum diameter 23.5 cm.

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan. Inv. No. A 0.9.17786. From the Lerici Collection.

|

On the body of the amphora are the faint remains of a man sitting in a sailing ship with oars, which is depicted at a smaller scale than the sailor. To the right of this scene, below one of the handles, is a Siren (see photo right). To the left, below the other handle (not visible in the museum display case), is a winged horse, presumably Pegasus, and an upright fish. On the back of the vase is a large cat resembling a tiger (see photo below). Above and below this frieze, in the bands on the shoulder and lower body of the amphora, are fish and sea creatures. On each side of the neck, between the handles, is a sheep, above one of which (see photo below) is what appears to be the Etruscan letter khe (similar in form to the Greek Ψ, psi).

The fact that the Siren appears behind the ship may signify that the sailor has escaped the danger and is able to sail on, but there is no certainty that the relationship of the separate images were deliberately designed to be read in this way.

Described by the museum as a "marine adventure", the paintings of the ship and Siren may comprise the earliest known representation of the Homeric episode of Odysseus and the Sirens. The oldest representation of a Homeric theme so far discovered in an Etruscan context is "the Aristonothos Krater", also found in a tomb at Cerveteri and dated to around 680-630 BC. One side depicts the blinding of Polyphemos which is also shown on a "white-on-red" pithos, perhaps from Cerveteri, made around 650-625 BC (see above).

Some scholars have proposed that such artefacts indicate that Homeric tales may have been known to the Etruscans by the 7th century BC, although motifs copied from imported Greek works may have had a different significance for aristocratic customers in Etruria.

The fish and marine creatures in the upper and lower bands are appropriate to the two main images, however the feline, winged horse and fish in the central band may be merely decorative space-fillers, typical of Archaic ceramic painting of the Orientalizing period (8th - 6th centuries BC). Etruscans may have considered lions, leopards and other large cats to be as fabulous as winged horses, and the "stripes" may just indicate a shaggy fur. Europeans are thought to have first encountered tigers at the time of Alexander the Great's campaigns in Asia, and they began appearing in western art during the Roman Imperial period when they were among the exotic animals imported for games in arenas.

Little has been published concerning this amphora, and the few authors who briefly mention it refer to:

Marina Cristofani Martelli (editor), La ceramica degli Etruschi: La pittura vascolare, page 10, figs. 17-18. Istituto Geografico de Agostini, Novara, 1987.

Martelli appears to have been the first to attribute the vase painting to the Painter of the Siren Attachment (Pittore della Sirena-Assurattasche), about whom there is also very little literature. His name is derived from the German word Assurattaschen (Assur attachments), used by the archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler to describe the protomes (front parts) of Sirens and other creatures designed as attachments for ancient bronze vessels, particularly cauldrons (see photo below), because of their similarity to depictions of the Assyrian god Assur.

Examination of details of the ship may reveal more about the imagery of the amphora, however I have yet to find more information on this specialist aspect. The ship is briefly described in a catalogue of representations of ships in Etruscan art in:

Olaf Höckmann, Etruskische Schiffahrt, catalogue No. CA 5, pages 278-279. In: Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz, 48,1 (2001), pages 227-308. PDF at Heidelberg University Journals.

Höckmann's illustrated study is primarily concerned with military and commercial shipping and piracy in the Etruscan world. Although he refers to much later illustrations of Odysseus and the Sirens, he does not discuss the iconography of this amphora. |

|

The Siren on the Etruscan amphora in Milan. It is

displayed next to a larger vase, so that the other

side with the flying horse can not be seen. |

|

| |

The tiger-like feline on the Etruscan amphora. |

| |

One of the sheep on the neck of the Etruscan amphora. |

| |

An Archaic bronze Siren protome as an attachment of a vessel.

Probably made in a Peloponnesian workshop around 725-700 BC. From Delphi.

Delphi Archaeological Museum.

Exhibited during the exhibition The Europe of Greece: Colonies and Coins from the

Alpha Bank Collection (Η Ευρώπη της Ελλάδος Αποκίες και Νομίσματα από τη Συλλογή

της Alpha Bank), Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, 11 April 2014 - 19 April 2015. |

| |

Odysseus and the Sirens on the body of an Attic black-figure oinochoe. 525-500 BC.

Odysseus stands tied to the mast of his ship as his companions row. Three Sirens, with

human heads and birds' bodies, stand close together on an overhanging rock above the ship.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 1993.216. A gift from the bequest of Frank Brommer, 1993.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

Drawing of a relief on an Etruscan cinerary urn from Volterra depicting Odysseus and the Sirens.

Volterra Archaeological Museum, Italy.

One the left three Sirens, shown as completely human, sit on a cliff, each playing a musical

instrument: a lyre, a syrinx (Pan pipes) and a diaulos (double pipes). They appear more like

ladies playing for dinner guests than dangerous or monstrous temptresses.

On the right Odysseus stands with his hands behind his back, tied to the mast of his ship which

has just passed the Sirens. He is naked apart from a pilos and a cloak over his shoulders.

His head is turned to the left as he looks back towards the Sirens. He is flanked by two of his

companions, Eurylochus and Perimedes, who tighten his bonds to prevent him diving overboard.

Another crewman sits at the rudder in the ship's stern.

Image source: R. Engelmann and W. C. F. Anderson, Pictorial atlas of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey,

The Odyssey, Plate XII, Fig. 65, text on page 24. H. Grevel & Co., London, 1892. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Odysseus and the Sirens on the body of a Late Corinthian black-figure

aryballos (ἀρύβαλλος, jar for perfume, ointment or oil). Around 575–550 BC.

Odysseus stands tied to the mast of his ship. The five helmeted heads of his companions rowing

the ship can be seen. Three Sirens stand on a rocky cliff. Two huge birds hover above the ship.

A large building (right) is either behind the ship or the Sirens. Height 10.2 cm. diameter 9.5 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. Inv. No. 01.8100. Purchased in Munich

by Edward Perry Warren. Purchased by the museum from Warren in 1901.

See: www.mfa.org/collections/...

Drawing by Karl Reichhold (1856-1919), Munich.

Image source: Heinrich Bulle, Odysseus und die Sirene, in W. Amelung and others,

Strena Helbigiana, pages 31-37. B.G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1887. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

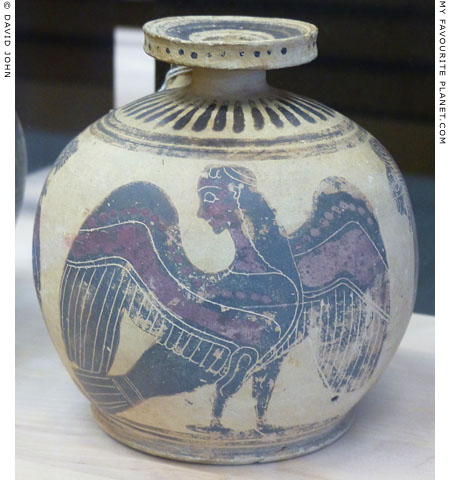

A Siren on a Corinthian black-figure spherical aryballos.

Around 600 BC.

Studiendepot Antike, Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden.

The ceramics and other ancient objects displayed in the temporary

"Studiendepot" room (open Saturday and Sunday only) are not

labelled, and it is not possible to view the other sides of the vases.

The form and painting style are similar to that of an

aryballos with a depiction three Sirens in the Museum

of Fine Arts, Boston. Inv. No. 21.279. Height 14.1 cm.

See: www.mfa.org/collections/object/aryballos-231671 |

|

| |

A Siren on a black-figure tripod pyxis.

Around 580 BC. From Offering Pit Ψ/VI/XV, Kerameikos, Athens.

Kerameikos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 44. |

| |

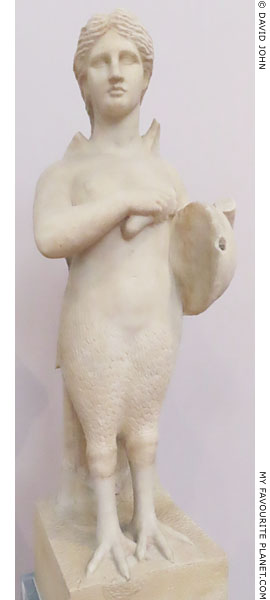

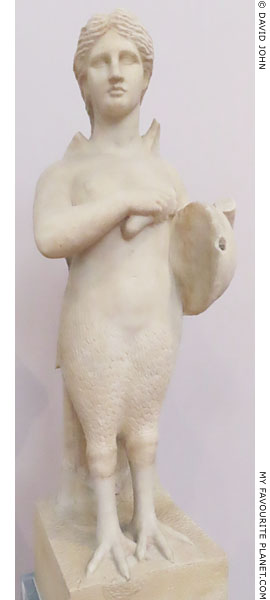

A funerary statue of a winged Siren

with webbed bird's feet, playing a lyre

made from a tortoise shell (see

Ancient Stageira gallery, page 19).

She probably held a plectrum in her left

hand (now missing). Holes in the sound

box indicate that the strings were made

separately, probably of bronze. The

plumage and other details were painted.

370 BC, Classical period. Pentelic marble.

Found in 1863 along with Inv. No. 775

(photo, centre) in the grave enclosure

of the Thorikioi in the ancient cemetery

of the Kerameikos, Athens. Height 83 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 774.

This statue, along with Inv. No. 775 may

have flanked the funerary stele of the

young Athenian horseman Dexileos,

who died near Corinth in 394 BC in a

battle against Sparta. Kerameikos

Museum. Inv. No. P 1130 (I 220).

Yet another Siren, circa 390 BC, found

in the same grave enclosure is also in

the Kerameikos Museum. Inv. No. P 761. |

|

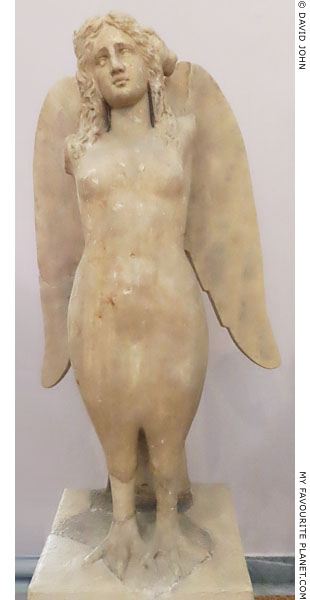

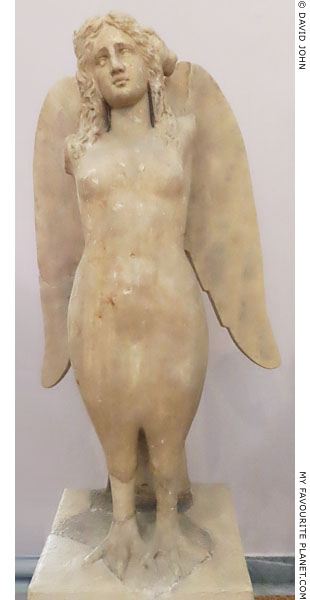

A funerary statue of a winged Siren

playing a lyre made from a tortoise

shell, holding a plectrum in her left

hand. The plumage on her legs is

indicated in relief. The feet and wings

have been restored with plaster.

330-320 BC, Hellenistic period.

Pentelic marble. Found in 1863 along

with Inv. No. 774 (photo, left) in the

ancient cemetery of the Kerameikos,

Athens. Height 99 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 775. |

|

A funerary statue of a winged Siren. The

arms and feet are now missing, although

part of the left hand has been found.

The feet appear to have been restored,

probably with copies from another

Silen statue Inv. No. 774 (photo, left).

330 BC, Hellenistic period. Pentelic marble.

Found in the ancient cemetery of the

Kerameikos, Athens. Height 122 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 2583. |

|

| |

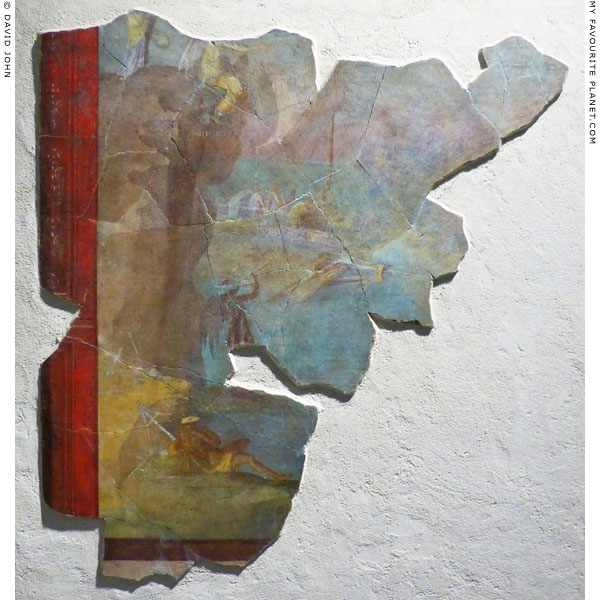

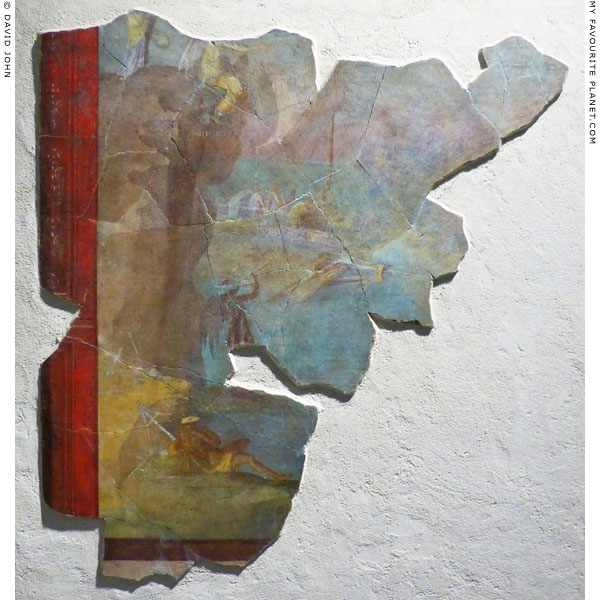

Fragments of a fresco painting depicting Odysseus (Ulysses) and the Sirens.

Late Republican period, mid 1st century BC. The fragments were among frescos from the

same cycle of scenes from The Odyssey excavated in 1848 in the remains of a Roman house

in the Via Graziosa (today Via Cavour) on the Esquiline Hill, Rome (see also image below).

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 261833. From the Gorga Collection.

|

One of the few surviving examples of 1st century BC wall painting, the landscape with figures is thought to have been inspired by Hellenistic models of the 2nd century BC. It has also been compared to frescoes found at the House of Livia on the Palatine Hill, dated around 30 BC.

As in some of the contemporary paintings from Herculaneum and Pompeii, the scenes appear distant, other-worldly, and not always easy to interpret. On the left, parts of three winged female figures, the Sirens, stand on the rocks of a cliff high above the sea, two stretch out one arm, perhaps beckoning sailors. Behind the cliff, figures can be seen aboard part of a passing ship with rigged mast and oars. One of the figures may be Odysseus tied to the mast. In the bottom left corner a male figure reclines on the shore below the cliff. |

|

| |

A reduced watercolour copy of the "Via Graziosa frescos", a cycle of fresco

paintings, here presented as six panels, depicting scenes from The Odyssey.

The originals, now in the Vatican Museums, were painted in the Late Republican period, mid

1st century BC. They were among frescos excavated in 1848 in the remains of a Roman house

in the Via Graziosa (today Via Cavour) on the Esquiline Hill, Rome (see also image above).

Watercolour on paper. Origin and artist unknown.

Hall of Antiquities (Antikenhalle), Semperbau, Dresden. No invoice number.

|

The orginals are in the Sala delle Nozze Aldobrandini (Aldobrandini Wedding Hall) of the Musei della biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vatican Apostolic Library Museums), Rome. Inv. Nos. 41013, 41016, 41024, 41026. Donated to Pius IX in 1851.

The entire fresco, originally divided into eight panels, illustrate the following scenes from The Odyssey, books 10-12:

the meeting between of Odysseus' companions and the daughter of the King of the Laestrygonians;

the Laestrygonians attack Odysseus' ships;

the Laestrygonians destroy Odysseus' ships;

Odysseus' own ship, the only one to survive, sails towards the island of Circe;

Odysseus in the palace of Circe;

possibly Odysseus' companions, transformed back to humans from pigs;

Odysseus in the underworld, meets the shadows of the dead;

Odysseus meets Orion, Sisyphus, Tityus and the Danaids.

We hope to be able to present a more detailed article dealing with the individual images in the not-too-distant future. |

|

| |

A bronze plaque in the form of the Homeric sea monster Skylla. She has an oar in her left

hand and probably held a stone in the right. An attachment from a vase or folding mirror.

Repoussé (hammered) bronze. Made in a workshop of Taras (Τάρᾱς, today Taranto, Apulia,

southern Italy), 350-300 BC. Found in 1875 during excavations by Konstantinos Karapanos

in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, near Ionnina, northwestern Greece. [8]

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. καρ. 82.

From the Konstantinos Karapanos Collection.

|

Skylla (Σκύλλα), who attacked Odysseus' ship in the straits between Italy and Sicily (Homer, Odyssey, Book 12), is depicted as a giant naked female as far as the waist, below which sprout the heads and bodies of dog-like creatures (in modern Greek σκύλα, skyla, means bitch, female dog). The remains of this figure and those below make her human-like part appear attractive, quite harmless, even benign.

The Skylla episode is represented on several types of ancient artefacts, including coins, fragments of a sculpture group found in Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli, and one of the Sperlonga statue groups known as the "Scylla Group", signed by three Greek artists (see Agesander of Rhodes). Skylla also appears on the cuirass of a marble statue representing the personification of The Odyssey from the Athenian Agora (see photos in Homer part 2). |

|

| |

A bronze figurine of Skylla.

Late 4th century BC. From the area of Karditsa,

Thessaly, northeastern Greece.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 21084. |

| |

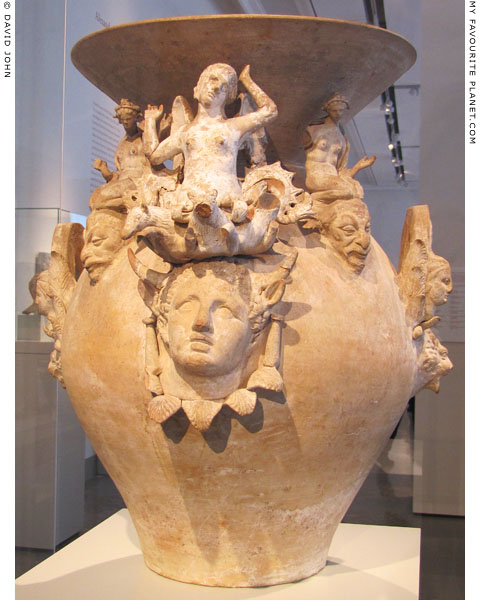

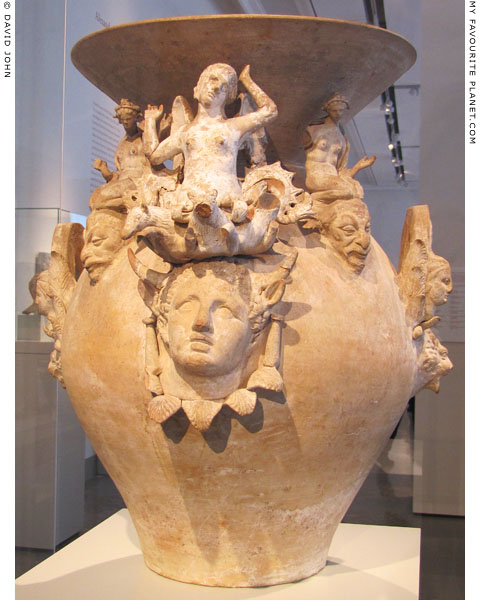

Daunian painted ceramic luxury vessel decorated with several

sculpted figures and protomes (heads) of mythological creatures,

including Skylla (see detail below).

Made in Canosa, northern Apulia, Italy, around 300 BC.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. V.I. 3194. Acquired in 1891. |

| |

Skylla on the Daunian ceramic vessel above, with remnants of paint. |

| |

Terracotta figure of Skylla.

Made in southern Italy around 250-200 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1856.1226-223. |

| |

A large marble trapezophoron (table support) with a high relief of Skylla (left). One of Odysseus'

companions (centre) is caught in the coils of her fish-like tail, while three dogs' heads protruding

from below her torso devour other men struggling in the waves (see photos below).

To the right a centaur, holding a syrinx (pan pipes), with a small eros (cupid) on his back

(see Aristeas and Papias of Aphrodisias). Above him an eagle holds a snake in its talons.

Mid 2nd century AD. From Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, near Rome, where fragments of a larger,

more elaborate, free-standing statue group of the same scene were also discovered.

Heavily restored by the Italian sculptor Carlo Albacini (circa 1739-1807), who

restored several ancient sculptures. Greek marble. Height 108 cm, width 160 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6672. |

| |

The relief of Skylla on the trapezophoron in Naples. |

| |

Skylla's three dogs' heads tear Odysseus' companions

to pieces in the sea on the trapezophoron in Naples. |

| |

Fragment of a marble staue of Skylla

or a Nereid from Ostia, near Rome.

Circa 150 AD. Found near the Nymphaeum

(II,VII,6), at the west of the theatre, Ostia.

Ostia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 183. |

|

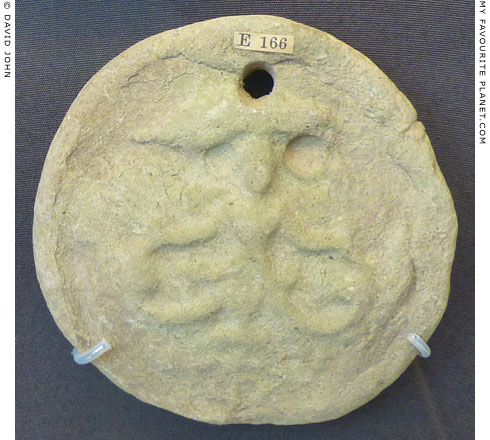

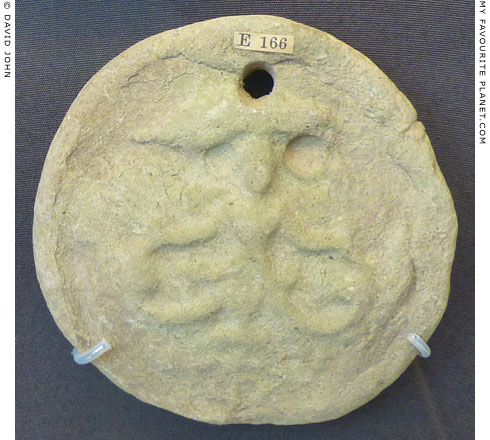

A round ("discoid") terracotta loom weight with a depiction of Skylla.

With each of her outstretched hand she holds one of her fish tails.

Above her head is an unidentified object. Such weights for

weaving looms were often dedicated at sanctuaries.

Made on Sicily around 400-100 BC. From ancient

Akragas or Gela. Diameter 7.94 cm (3 1/8 inches).

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1863,0728.207 (Terracotta E 166).

Donated by George Dennis in 1863. [9]

See also loom weights from Sicily decorated

with Gorgoneions in Medusa part 7. |

|

| |

A silver tetradrachm coin of Akragas (Ἀκράγας, today Agrigento), southern Sicily, inscribed

ΑΚΡΑΓΑΚΙΝΟΝ, with a depiction of a crab above Skylla, who has the fore-parts of two dogs.

On the reverse side two eagles stand on the corpse of a hare, and the letters ΚΡΑΓΑ.

Engraving by Henry Moses from drawings by the English traveller,

architect and archaeologist Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863).

|

"Silver tetradrachm of Agrigentum, selected by permission from the valuable collection of Lord Northwick.

The magnificent workmanship of this coin abundantly displays the taste of the Agrigentines: the Scylla and the Crab (above which ΑΚΡΑΓΑΝΤΙΝΟΝ, imperfectly expressed in the engraving, is distinctly legible) seem aptly to designate the inaccessible coast and treacherous rocks by which their fertile and inviting territory is defended.

In the two eagles on the obverse, the one uttering the piercing shriek so often heard by the traveller in those regions, the other devouring its prey; the imperial dominion, affected by the ambitious Agrigentines, and their triumph over their enemies, may be signified."

Source: Charles Robert Cockerell, The Temple of Jupiter Olympius at Agrigentum, commonly called the Temple of the Giants. Included at an introduction to James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, Antiquities of Athens, Volume 4: The antiquities of Athens and other places in Greece, Sicily etc.: supplementary to the antiquities of Athens. Delineated and illustrated by C. R. Cockerell, W. Kinnard, T. L. Donaldson, W. Jenkins, W. Railton, architects. Illustration on the title page, text on page 4. Priestley and Weale, London, 1830. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

The round central emblema (panel) of a pebble mosaic floor with a depiction of Skylla.

The image is made of relatively large pebbles giving the image a coarse quality with

little detail. According to the museum labelling Skylla is about to throw a stone

with her raised right hand, and in her left hand she holds a helmet (according to

other sources a paddle). The two raging dog protomes emerging from her lower

torso can just about be discerned.

Late 3rd - early 2nd century BC. Found in the andron (symposium room) of the Anyphantes

House in Eretria, Euboea, central Greece. Black, white, yellow and pale red natural pebbles.

The floor mosaic, 265 cm square, is framed by a border with a wave pattern. A field of white

pebbles surrounds the central circular emblema (or medallion), diameter 102 cm.

New Archaeological Museum "Arethousa", Chalkis, Evia. |

| |

A pebble mosaic floor mosaic depicting the marine deity Triton fighting Skylla at sea,

above two leaping dolphins. According to one mythological tale, as a young girl

Skylla refused the advances of Triton, and in his anger he asked the sorceress

Circe to transform her into a monster who would bring death to seamen.

4th century BC. From Eretria, Euboea, central Greece.

New Archaeological Museum "Arethousa", Chalkis, Evia. |

| |

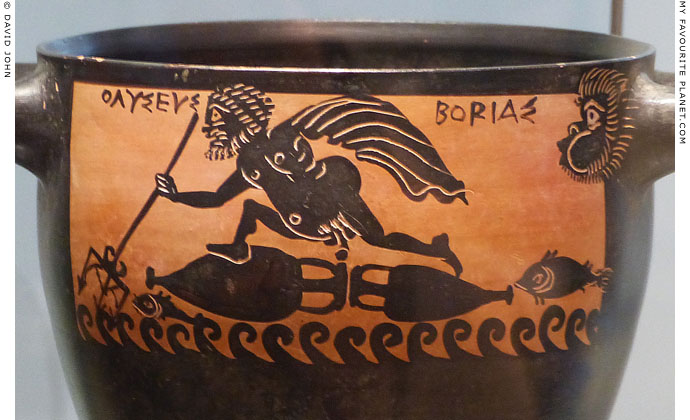

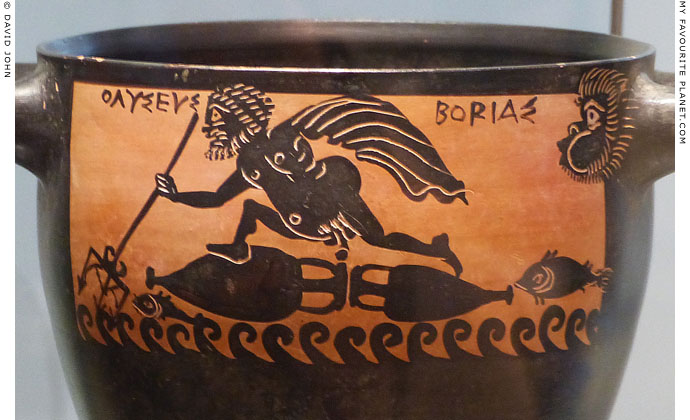

Detail of a Boeotian black-figure skyphos (deep drinking cup) with a depiction

of Odysseus (inscribed ΟΔΥΣΕΥΣ), wearing only a cloak and holding a trident in