|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Macedonia > Stageira & Olympiada |

| Stageira & Olympiada |

History of Stageira & Olympiada - Part 8 |

|

|

page 9 |

|

|

| |

MAP 1. Detail of a map of Greece by Nicolas Sanson, 1694, showing the purported location of "Stagyra". |

| |

History of Ancient Stageira - Part 8

Historical maps |

| |

The historical maps on this page reflect the growing knowledge of travellers, scholars and cartographers from the 17th to the early 20th century, as they attempted to identify the locations of ancient places such as Stageira. In many cases - including that of Stageira - the only clues they had to go on were brief, vague and sometimes inaccurate descriptions by ancient historians and geographers such as Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy.

Renewed interest in ancient Greece began in the Renaissance, and by the advent of the Enlightenment European geographers felt confident enough to produce maps based on the texts of ancient authors and the reports of a handful of early travellers, such as Spon and Wheler. The early maps were bold and ambituous attempts to solve the mysteries of ancient Greek geography, although they contain many errors and anomalies. To a certain extent these efforts to match ancient literary descriptions to topographical realities, the knowledge of which remained limited, was rather like playing the game of "pin the tail on the donkey".

By the mid 19th century so many scholars were playing this game and adding their opinions that the early confidence evaporated, and nobody seemed to be at all certain where these cities actually were. In the case of Stageira, it took until 1990 before the tail was firmly pinned down (see History part 7).

The English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) produced the first English translation of History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, first published in 1628, which included a gazetteer with brief geographical information about places in Greece mentioned in the text. This included entries for Stageira and Akanthos:

"Stagirus, a City in the Bay of Strymon, betweene Argilus and Acanthus. Herodot. lib. 7."

"Acanthus, a City neere to the Isthmus of Mount Athos, and (as in the Epitome of Straboes seventh Booke) in the Bay of Singus. But it appeareth by Herodotus in his seventh Booke, that it lyeth on the other side, in the Bay of Strymon; where he saith, that the Isthmus of Mount Athos is of twelve furlongs length, and reacheth from Acanthus to the Sea that lyeth before Torone. And in another place of the same Booke he saith, that the Fleete of Xerxes sayled through the Ditch (which Xerxes had caused to bee made through the said Isthmus) from Acanthus, into the Bay, in which are these Cities, Singus, etc." [1]

The French royal cartographer Nicolas Sanson d'Abbeville (1600-1667) first identified the location of Stageira more exactly in his Graeciae antiquae descriptio, published in 1636. Several improved editions subsequently appeared, including the above 1694 version by his sons Adrien and Guillaume, who continued his work after his death.

Similar identifcations of Stageira's location were made by 18th century map-makers, notably: Guillaume Delisle (1675-1726) in his Graecia Pars Septentrionalis, published in 1700, and later republished in various formats and editions; and The Charta of Greece by the Greek revolutionary Rigas Velestinlis-Feraios (Ρήγας Βελεστινλής-Φεραίος, 1757-1798), printed in Vienna in 1796 and 1797. Only six copies of Rigas' Charta are known to still exist.

Such maps were widely copied, errors and all. However, thanks to the technical innovations introduced by Delisle, particularly in scaling and setting coordinates, new standards were established for map-making. |

Nicolas Sanson d'Abbeville |

| |

Rigas Velestinlis-Feraios

statue, Athens University.

photo: © David John |

| |

| |

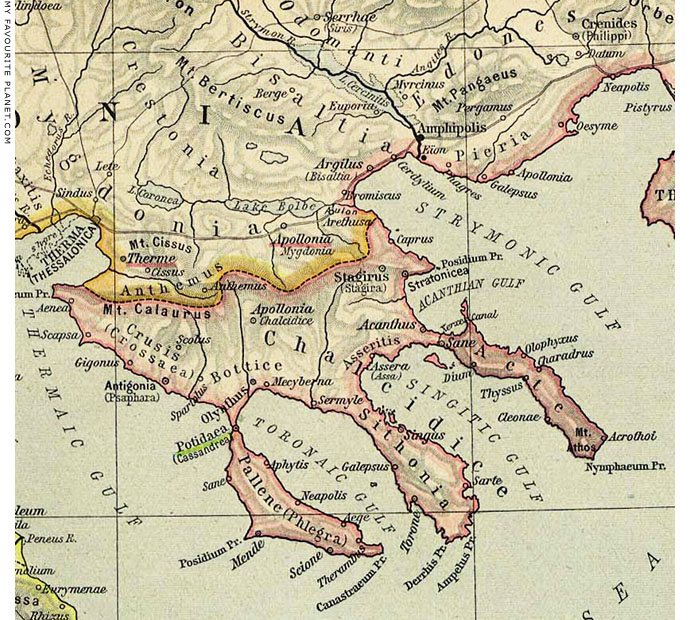

MAP 2. 1854 historical map of Halkidiki, with Ancient Stageira

marked at its correct location as "Stageirus".

Detail of a map of ancient Greece, from The geography of Herodotus by James Talboys Wheeler

(1824-1897). Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, London, 1854. At the Internet Archive. |

|

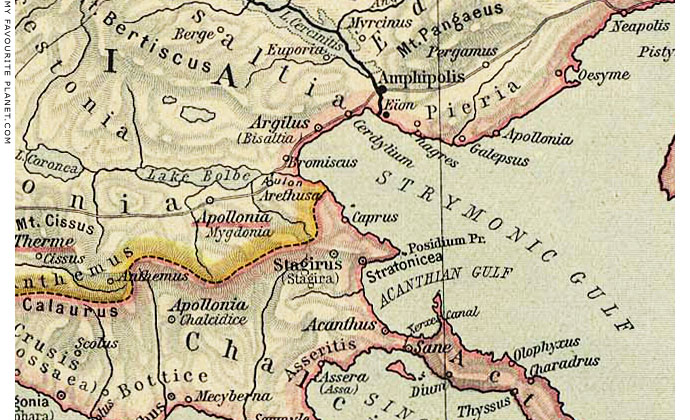

MAP 3. Historical map of ancient Halkidiki, 1908, showing

the location of Stageira, Akanthos and other Greek cities.

Part of a map of Macedonia and Thrace, from Samuel Butler, The Atlas

of Ancient and Classical Geography. J. M. Dent and Co., London, 1908. |

|

MAP 4a. Historical map of ancient Halkidiki made in 1923, before the location of Stageira and other

ancient Greek cities had identified beyond dispute. The harbour of Kapros, marked here as

"Caprus", is correctly marked, but the site of Stageira has been incorrectly placed further inland.

Part of a map of ancient Greece, from Historical Atlas by William Robert Shepherd (1871-1934),

American cartographer and historian. Published by Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1926. |

|

MAP 4b. Detail of the above map: northeast Halkidiki,

with the site of Ancient Stageira marked as "Caprus". |

|

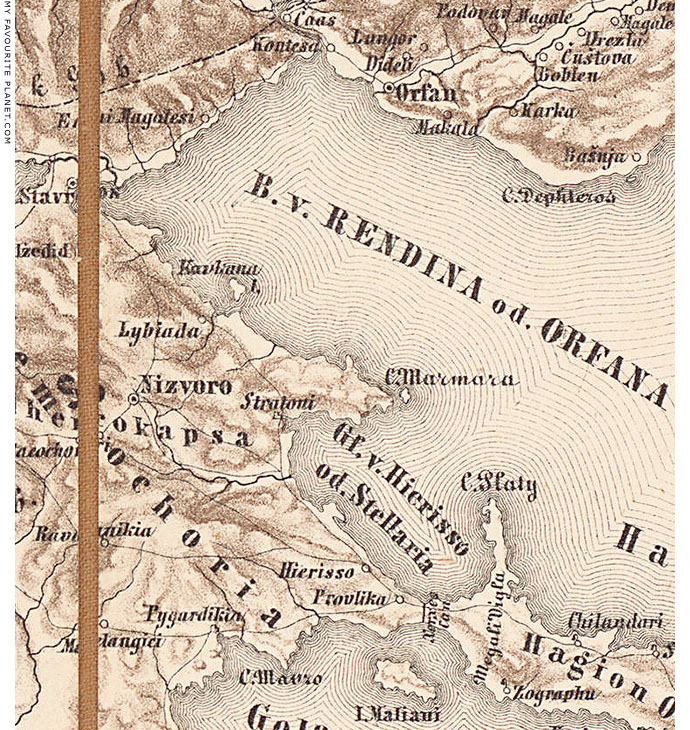

MAP 5. North-east Halkidiki on an Austrian military map, 1860-1870.

|

Detail of a military map of Turkey and Greece, made 1860-1870 by the Militär-geographischen Institut of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, under the direction of cartographer Major General Joseph Ritter von Scheda (1815-1888). Source: wikipedia.

The Austrian military began systematic map-making in the 18th century, though due to the secrecy of the operations, the early maps were not published.

A settlement on the road between Stavros and Stratoni, marked as "Lybiada", is shown slightly inland of the current location of Olympiada (also pronounced Olymbiada). Kafkanas island (or Kavkanas; Greek, Καυκανάς; ancient Kapros) is marked as "Kavkana Insel".

The Strymonic Gulf is marked as the "Bucht" (German, Bay) of "Rendina or Orfana".

Nizvoro, southwest of Lybiada ("Nicalide" on Gerard Mercator's 1662 map Macedonia, Epirus et Achaia), was thought by some scholars during the 19th century to be a possible site of Ancient Stageira, hence the mistaken renaming of the nearby village Kazantzi Machala (Καζαντζή Μαχαλά) as Stageira in 1924. Like nearby Stratoni, this area belonged to the territory of the ancient city Stratonikeia. The Slavicized name of Isvoro (Ίσβορο) was changed in 1924, reverting to the Greek Stratoniki (Στρατονίκη).

The date of the foundation of Stratonikeia (mentioned, though incorrectly located, by Ptolemy, Geography, 3.2.19) remains uncertain, but it may be have been founded by a Macedonian king during the Hellenistic period or even earlier in order to control the local gold and silver mines. It is thought to have been named after one of the many members of the Macedonian royal family named Stratonikis or Stratonike.

Stavros (Σταυρός), the seaside resort 15 km north of Olympiada (see photo below), was also a candidate for the location of Stageira. Its Greek name means "cross", one of many places in Greece with this name. Either the name has religious significance, or simply meant that it stood at a crossroads, in this case a T-shaped junction between the Via Egnatia (History part 7) and the road south through Stageira and Akanthos to Athos.

19th century scholars attempted to see in the name Stavros an abbreviation or corruption of Stageira. Herodotus referred to Xerxes' army crossing "the plain of Syleus (as they call it)" (Συλέος, Syleos), keeping "the gulf off Poseideion" (the Strymonic Gulf) to his left, before passing Stageira (Herodotus, The Histories, Book 7, chapter 115, see History part 4). This description fits the narrow, flattish coastal strip along which modern Stavros now stands. We should remember that the sea level 2,000 years ago was about 2 metres lower than it is today, and the land may have been wider. On the other hand, sand washed ashore and silt deposited by the Richios River (see photo below) may have since added to the land's width.

It is thought that in antiquity Stavros - or rather what today is Ano Stavros (Άνω Σταυρός, Upper Stavros), on the hillside above the plain - was known as Bromiskos (Βρομίσκος), where Thucydides tells us the Spartan general Brasidas stopped to dine on his way to conquer Amphipolis (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 4, chapter 103, see History part 5). He also tells us it was "where the lake of Bolbe runs into the sea", a perfect description of the location of Stavros at the mouth of the Richios River (or Rihios, Ρήχειος ποταμός, mentioned by the Byzantine historian Procopius, De Aedificiis, 4.4; See photo below), the eastern outlet of Lake Bolbe (or Volvi, Βόλβη λίμνη) into the Strymonic Gulf (see photo below).

On Sanson's historical maps Stavros is marked as "Cemnorus" (map 2), while on maps showing contemporary placenames, such as Etats de L'Empire des Turqs en Europe, 1655, it appears as "Contessa", and the Strymonic Gulf as the "Gulf of Contessa". In the map above, "Kontessa" and "Orfan" are marked on the coast, east of mouth of the River Strymon. In some contemporary maps (e.g. Macedonia, Epirus et Achaia by Joan Janssonius and Hendrik Hondius, Amsterdam, 1638-1640), "Contessa" is marked more to the east, where Nea Vrasna and Asprovalta stand today.

In the 1692 edition of Sanson's Etats, Olympiada is marked "Libanotia", one of its many variants (Livasdias, Lipsada, Lipsasa, Lybiada, Libiada, Limbaz...), proving that the name is not a recent invention. It is clear from such maps and other documents that place names became corrupted and mangled over the centuries, due to changes in government, language, dialect and careless pronunciation, as well as errors and misunderstandings by authors and officials. Even today there is no standard system for transliterating Greek names into the Latin alphabet, which still causes headaches for mapmakers, translators, travellers and authors.

The vertical line, east of "Hierisso" (Ierissos, site of ancient Akanthos) and "Provlika" (today Nea Roda), on the narrowest part of the isthmus separating the main part of Halkidiki from the Athos peninsula, is the site of the 2 km long Xerxes Canal (η Διώρυγα του Ξέρξη), built by the Persian king Xerxes the Great in 483-480 BC (see History part 4). The isthmus became known as the Vale of Provlaka, from Pro-Avlaki, the name of the canal (Greek, αυλας; Πρόβλακα = πριν + αυλάκι, prin avlaki, before the small canal; Latin, Proaulax). See detail in map 7 below.

This early military map has no indications of altitudes of hills and mountains, an omission which was rectified in the 3rd Austro-Hungarian Mapping Survey ( see map 6 below). |

| |

| |

The modern port of Stavros on the west coast of the Strymonic Gulf,

15 km north of Olympiada, thought to be the location of ancient Bromiskos.

|

Stavros stands at the foot of Sougliani (Σουγλιάνι Κορυφή, Sougliani Summit, marked as the 554 metre high "Sugljani" on Map 6 below), one of a number of peaks of the steep-sided Mount Stratoniko (or Stratonikos, Στρατονικό Όρος), which stretches from just northwest of Stavros to Stratoni in the south (see Map 5 above). Stratoniko is considered part of the Holomantos (Χολομώντας Όρος) range which spreads across much of central and east Halkidiki. Just northeast of Stavros and the north side of the Richios river valley (see below) is the western end of Mount Kerdylion (Όρος Κερδύλιον), part of the Kerdylia (Κερδύλια) mountain range, which stretches eastwards to the river Strymon.

The British journalist and author George Frederick Abbott (1874-1947), who spent three years (1900-1903, before Macedonian independence in 1913) travelling through Macedonia to study the local folklore traditions, reported that local people called one of the mountains near Stavros "Alexander's Mount":

"Again, near the village of Stavros, or 'The Cross', close to the eastern coast of the Chalcidic Peninsula, and a little to the north of the site where Stageira, Aristotle's birthplace, is generally located, there rises a mountain, unnamed in maps, but known to the peasantry as 'Alexander's Mount' (το Βουνό του Αλεξάνδρου, or, less correctly, της Αλεξάνδρας) — a designation especially appropriate in a neighbourhood which is associated with the name of Alexander's famous tutor."

George Frederick Abbott, Macedonian folklore, page 280. Cambridge, University press, 1903. At the Internet Archive.

Read more about "Alexander's Mount" on the Alexander the Great page in the MFP People section. |

|

|

| |

The south shore of Lake Bolbi, near the site of ancient Apollonia, north of Stageira.

|

The two long freshwater lakes, Bolbi (Λίμνη Βόλβη, Limni Volvi) and Koroneia (Λίμνη Κορώνεια, also known as Lake Langada) to its west, are the oldest in Greece and around 1.8 million years ago formed a single ernomous lake covering the area which became known in antiquity as Mygdonia. The depression in which they lie runs along a geological fault line, part of the Thessaloniki–Rentina Fault System *. Low farmlands south of the lakes rise into the hills which form the boundary between mainland Macedonia and the Halkidiki peninsula.

* See: Markos Tranosa, Eleftheria Papadimitriou, Adamantios Kiliasa, Thessaloniki–Gerakarou Fault Zone (TGFZ): the western extension of the 1978 Thessaloniki earthquake fault (Northern Greece) and seismic hazard assessment. Journal of Structural Geology, Volume 25, Issue 12, December 2003, pages 2109–2123. |

|

|

| |

The River Richios, the only outlet of Lake Bolbi, shortly before it enters the Strymonic Gulf at Stavros.

|

| The Richios river (Ρήχειος ποταμός) exits the east side of Lake Bolbi near the village of Rentina (Ρεντίνα, Rendina), where there are the remains of a medieval castle and the ruins of ancient Arethousa are believed to lie. (Despite road signs at Rendina pointing the way to the "archaeological site of ancient Arethousa" there is nothing to be seen and no ancient ruins have yet been found there!) It flows through a beautiful, narrow, wooded valley, known in antiquity as the vale of Aulon or Arethousa, in which the tomb of Euripides was said to have stood (see History of Pella), opens onto the sandy coastal plain just north of Stavros, and makes its way to the Aegean Sea. At its mouth the stream is surrounded by reeds and grasses, and goats are grazed here. |

|

|

|

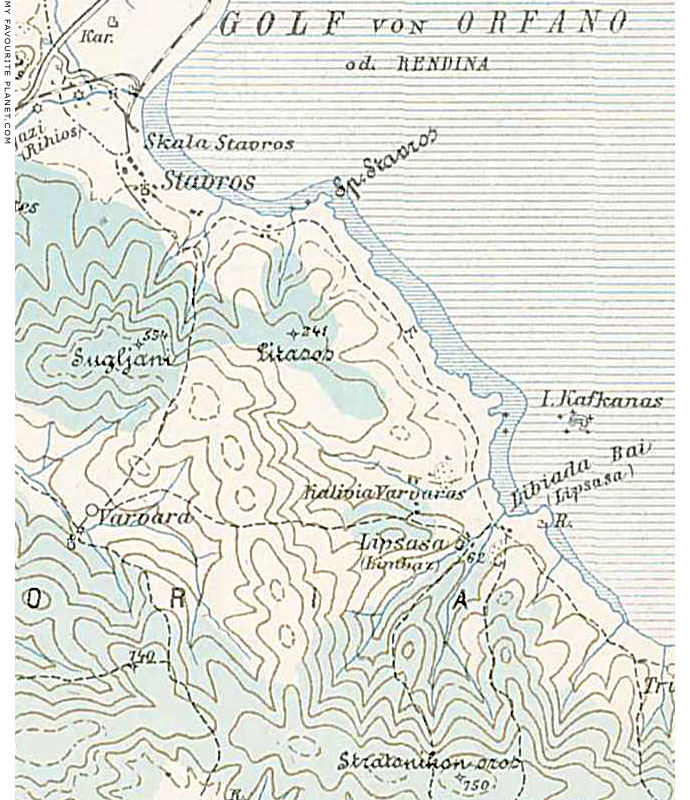

MAP 6. The area of Stavros and Olympiada on an Austrian military map, 1917.

|

This is a more detailed, accurate, modern-looking map design, with height countours, although the handwriting style is difficult to read. Altitudes are marked, some areas, presumably woods, are shaded in blue-green, and different classes of road can be distinguished. The road passing diagonally through the top-left corner is the Via Egnatia (History part 8), the main highway between Thessaloniki and Kavala, and part of the ancient Roman road between the Adriatic coast and Byzantium (later Constantinople, today Istanbul). During the time of the Ottoman Empire it was an important post road.

The dotted lines represent lesser roads through north-eastern Halkidiki. The first proper roads in this area were built by the Persian King Xerxes I (see history part 4). As recently as 1967, The Blue Guide to Greece described some of these roads as "bad" (an understatement) or mere "paths". Things have improved considerably since, although pot-holes are still common on some stretches of minor roads (cyclists beware!).

The location of modern Olympiada is marked as "Libiada Bai" (Bay?) and in brackets as "Lipsasa". A small settlement less than 1 km inland is also marked as "Lipsasa", in brackets "Limbaz", presumably its Turkish equivalent, a corruption of Olympiada.

It was quite usual in the Mediterranean for villages, even of fishing communities, to be built inland for fear of pirates. According to Dr. Kostas Sismanidis' booklet, "Ancient Stageira, the birthplace of Aristotle" (see History part 1), when the Greek settlers arrived at Olympiada as refugees from Turkey in the 1920s "they found a settlement of about 10 rural families".

Once again Kafkanas (Kapros) island is marked as "Kavkana Insel", and enigmatically "R." (the abbreviation of "Ruinen", ruins) and a symbol for buildings appears on the southeast side of Liotopi headland, in the bay below the site of Ancient Stageira (see map on Ancient Stageira photo gallery, page 7).

Also visible in top-left corner of this map is part of a now defunct railway line, marked as black and white striped lines, with a junction and terminus at Skala Stavros (Stavros Port), just north of Stavros. The line ran westwards between the old Via Egnatia and the Richios river, along the Vale of Arethousa in the direction of Thessaloniki. In the other direction, railway ran northeastwards, along the coast of the Strymonic Gulf, crossed a bridge over the Strymon river near the village Nea Kerdilia (Νέα Κερδύλια, the location of the Lion of Amphipolis monument), then continued up the left (east) bank of the river to Amphipolis. Today there is very little of the railway to be seen, apart from the ruins of a narrow bridge over the Richios river near the crossroads north of Stavros, and the old Amphipolis railway station. The complete disappearance of rail tracks and other visible evidence of the railway's existence makes the station building appear like a fish out of water, standing isolated on the river bank near the road up to Amphipoli village.

Detail of a military map of the Thessaloniki area, part of the 3rd Military Mapping Survey of central and south-eastern Europe by the Ministry of War of Austria-Hungary, which began in 1869 and continued until the first years of World War I.

Source: László ZENTAI, http://lazarus.elte.hu/hun/moterkep.htm |

|

|

|

MAP 7. The 2 km long Xerxes Canal, built 483-480 BC, and the "Provlakas" on the isthmus which

separates Halkidiki from the Athos peninsula, east of "Jerisos" (Ierissos, the site of ancient Akanthos).

Part of a map of the Athos peninsula, from the Austro-Hungarian 3rd Military Mapping Survey

(see map 6 above).

|

"Thinking it over, I cannot but conclude that it was mere ostentation that made Xerxes have the canal dug - he wanted to show his power and leave something to be remembered by. There would have been no difficulty at all in getting the ships hauled across the isthmus on land; yet he ordered the construction of a channel for the sea broad enough for two warships to be rowed abreast."

Herodotus, The Histories, Book 7, chapter 24. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt (1896-1962). Penguin Books, 1954.

The British antiquarian and topographer William Martin Leake (1777-1860), who visited Athos in October-November 1806, thought not only had the canal been a good idea, but that it should be rebuilt.

"As history does not mention that it was ever kept in repair after the time of Xerxes, the waters from the heights around have naturally filled it in part with soil in the course of ages. It might, however, without much labour be renewed: and there can be no doubt that it would be useful to the navigation of the Aegean, for such is the fear entertained by the Greek boatmen of the strength and uncertain direction of the currents around Mount Athos, and of the gales and high seas to which the vicinity of the mountain is subject during half the year, and which are rendered more formidable by the deficiency of harbours in the Gulf of Orfana [the Strymonic Gulf, see above], that I could not, as long as I was on the [Athos] peninsula, and though offering a high price, prevail upon any boat to carry me from the eastern side of the peninsula to the western, or even from Xiropotami to Vatopedhi. Xerxes, therefore, was perfectly justified in cutting this canal, as well as from the security which it afforded to his fleet, as from the facility of the work, and the advantages of the ground, which seems made expressly to tempt such an undertaking."

Leake added: "If there be any difficulty arising from the narrative of Herodotus, it is in comprehending how the operation should have required so long a time as three years *, when the king of Persia had such multitudes at his disposal, and among them Egyptians and Babylonians, who were accustomed to the making of canals."

* Herodotus, Book 1, chapter 7.

William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece Volume 3 (of 4), Chapter 24, page 145. Rodwell, London, 1835. At the Internet Archive.

Despite Leake's recommendation, Xerxes' Canal is unlikely to be renovated because of its historical importance and the costs involved. However the 4th century BC canal built by Cassander across the isthmus of Halkidiki's western-most prong Pallene (today called Kassandra), near Nea Potidea (see History part 6), was redug in the 1930s. |

|

|

|

MAP 8. Part of the Ethnographic map of Macedonia, from the point of view of the Bugarians.

Designed by Th. Weinreb, after Vasil Kancov. Librairie Hachette et Cie., Paris, 1914.

|

After successfully fighting for independence from Ottoman Turkey during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Balkan states argued among themselves over who was entitled to which lands and where the new borders should be drawn. Sadly, this controversy continues today. Macedonia and Thrace were particularly affected by these disputes, with the former finally being divided between Greece, Bulgaria (the region of Blagoevgrad, also known as "Pirin Macedonia") and Serbians (today the former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia, since 2019 named the Republic of North Macedonia, see Introduction to Macedonia; also referred to as "Vardar Macedonia" after the Vardar River). |

|

Ethnographic map

colour key |

|

Over the centuries various ethnic groups had settled across the southern Balkans, including Turks, Albanians, Serbs, Bulgarians, Pomaks, Vlachs, Roma and Jews. This complicated the issues, and made nation-building a difficult and dangerous business for those who lived in the areas disputed in an age of rampant nationalism.

Maps such as the one above were produced to provide a graphic context to these territorial disputes from the viewpoints of the various parties. Each of the maps tells a different story. This French map illustrates the Bulgarian claim that Bulgarians inhabited large swathes of Macedonia, a claim that has been refuted as being inaccurate and over-simplified. Many towns and villages of Macedonia and Thrace were ethnically mixed, and some still are.

Halkidiki was mostly agricultural, with small, often poor villages, inhabited mainly by Greeks. Turks had occupied most administrative posts, and there were a few Turkish settlements on the north and west of the peninsula, as well as at Nizvoro from where a Turkish official had ruled and taxed the district (Mademochoria, mining villages) and controlled the local mines. We also see a small pocket of Bulgarians south of Thessaloniki. The other Bulgarians, as well as Russians, living here were monks in the monasteries of Athos (on the map marked as "Hagion Oros", Holy Mountain).

George Frederick Abbott (see above) wrote of the monasteries:

"Out of the twenty monasteries seventeen are purely Greek, one Servian, one Bulgarian [Zographou monastery], and one Russian. There is also a small Roumanian skete of little or no importance."

George Frederick Abbott, The tale of a tour in Macedonia, Chapter 39, page 331. Edward Arnold, London, 1903. At the Internet Archive.

Abbott had much to say about the nationalistic disputes over Macedonia. For example, when describing the railway route eastwards from Serres to Drama, he wrote that there were only three villages where Bulgarian was spoken north of the line, which effectively formed a boundary between mixed populations to the north and the purely Greek-speaking area to the south.

"There are no important towns along the road; Sarmousakli, Zichna, Zeliachova, and Alistrati exhaust the list. They all lie to the north of the line, and can hardly be designated as towns. They are great straggling villages with a mixed population.

The inhabitants of Zeliachova, Christians though they be, use the Turkish language, and are only just beginning to learn or re-learn Greek. There are several other instances of Christians having adopted the language of the Mohammedan conquerors, partly as the natural effect of intercourse and partly as a means of self-preservation.

An example of the reverse is afforded by Lialiova, a township farther north, near Nevrokop. The inhabitants of that place are Mohammedan by religion, and yet until recently they employed the Greek language even in the formula with which the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer from the minaret and which generally is in sacred Arabic.

The populations of the other villages mentioned, though speaking mostly Bulgarian, as a rule side with the Greeks. Alistrati especially is distinguished for its staunch adherence to the Greek cause and for its excellent Greek primary schools. These four villages, in fact, form the boundary line between the debatable territory to the north and the purely Hellenic district which extends to the shores of the Aegean, and which, though it includes several Mohammedan settlements, does not contain a single Slav community.

This fact of elementary geography comes as a surprise to the traveller. The apostles of the Bulgarian propaganda have been so energetic that they have succeeded in colouring the map in accordance with their wishes, and even some English ethnographical works make the mistake of yielding part of this district to the Slavs.

The inhabitants of the villages near the mouth of the Struma [River Strymon] told me how a short time ago Russian naval officers, engaged in surveying that part of the coast, expressed their astonishment at hearing Greek spoken in a district which the Pan-slavist pamphleteers had taught them to regard as Bulgarian.

But geography is not the only subject that is treated as a political question in this curious comer of Europe. In their proclamations the leaders of the Slavo-Macedonian Committee appeal to Alexander the Great as a national hero. After this, I am inclined to believe the statement that in their school text-books Aristotle also is described as a great Bulgarian philosopher."

Ibid, Chapter 33, pages 277-278.

Whether Abbott can be considered to have been an impartial oberver is debatable.

The British topographer William Martin Leake (1777-1860), who travelled through northern Greece several times in the early 19th century, wrote of the people of Halkidiki:

"Notwithstanding the mass of ignorance collected in the monasteries of the Oros [Mount Athos], some recollections of ancient history are still preserved here. This may be attributed in great measure to the Chalcidice and its three smaller peninsulas being inhabited by Greeks unmixed either with the Bulgarian or Albanian race, and having very few Turks among them."

William Martin Leake, Travels in Northern Greece Volume 3 (of 4), Chapter 25, pages 159-160. Rodwell, London, 1835. At the Internet Archive.

See also History of Stageira and Olympiada - Part 7. |

|

|

| |

Stageira &

Olympiada

History

part 8 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Thomas Hobbes on the locations of Stageira and Akanthos in Thucydides

"The names of the places of Greece occurring in Thucydides, or in the Mappe of Greece, briefly noted out of divers Authors, for the better manifesting of their situation, and enlightning the History." In: Thucydides, The eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre, translated by Thomas Hobbes. Richard Mynne, London, 1634. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

Photos, maps and articles: copyright © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: copyright © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide

comprehensive and accurate information across this

website. However, we can take no responsibility for

inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services

mentioned on these pages. |

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|