| |

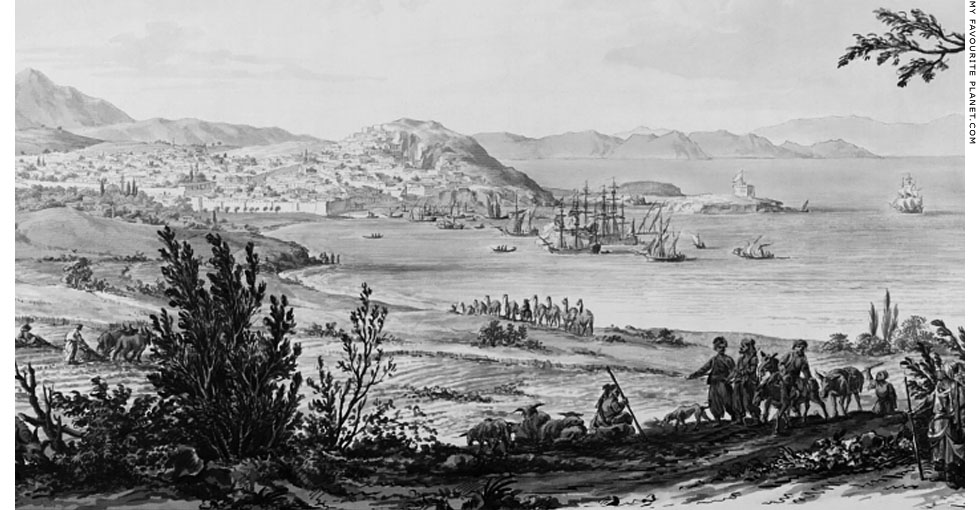

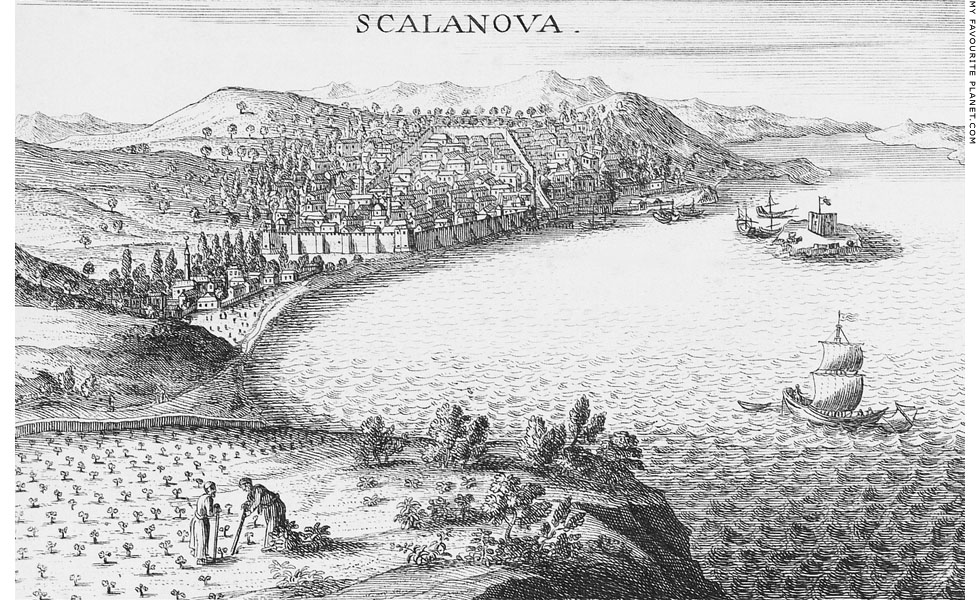

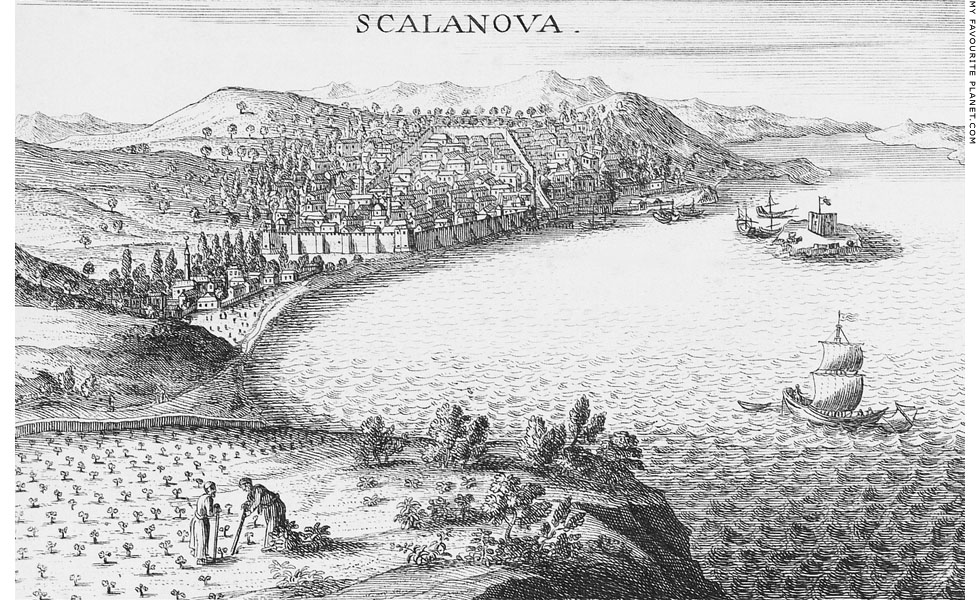

"Veue de Scalanova proche de Smyrne" (view of Scalanova near Smyrna)

from Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, Relation d'un voyage du Levant, 1717.

|

The French doctor and botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708), who visited Scala Nuova in late January 1702, described it as a pretty town, well built and well paved, inhabited by Turks, Greeks, Jews [6] and Armenians. "We left Ephesus on 27th January to see this last place which the Turks call Consada and the Greeks Scalanova, the Italian name given to it by the Franks, perhaps after the destruction of Ephesus." The mosques were small, the Greeks worshipped in the church of Saint George (Άγιος Γεώργιος, Agios Giorgos) in the suburbs ("les fauxbourgs") on the hill, and there was also a synagogue [7]. He reported that the commercial trade of the harbour was not considerable, dealing mainly with wheat and beans, and the port was primarily used by the military, with a small garrison in the fortress and janissaries stationed outside the town. He also noted that there were many ancient marbles to be seen there.

Tournefort's voyage through the Turkish empire from 1700 to 1702 was commissioned by King Louis XIV. His journey took him to several Greek islands, and he travelled through Anatolia to the Black Sea, visiting Mount Ararat and Jerewan in Armenia and Tiflis in Georgia. He was accompanied by the German doctor and botanist Andreas Gundelsheimer (1668-1715) and the French artist Claude Aubriet (circa 1651 or 1665 - 1742), who probably drew the scene of Scala Nuova from which the engraving was made.

Tournefort described his journey in letters addressed to the Comte de Pontchartrain, the king's secretary of state, which were published in 1717, nine years after his death.

Image source: Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, Relation d'un voyage du Levant, Tome second (volume 2 of 2), Lettre XXII, page 524. Imprimerie royale, Paris, 1717. At the Internet Archive. Tournefort's description of Scala Nuova is on pages 523-525. See an English translation of Tournefort's report on Kuşadası below [8].

The view was drawn from the the hills north of the harbour, looking to the southwest. In the distance is the 1,237 metre high Mount Mykale (Greek, Μυκάλη; Turkish, Samsun Daği, Samson's Mountain), and on the extreme right is the southeast tip of the island of Samos. The fortress on Güvercin Ada (Pigeon Island) is shown as it was before the causeway was built in the 19th century. Immediately behind the island is the Yilanci Burnu headland.

A defensive wall stretches across the town's seafront, and the town centre on the hillside is also surrounded by high wall. Tournefort said that the Turks and Jews lived in the fortified centre, and that the Greeks and Armenians lived only in the suburbs outside the walls. The domed roof and what appears to be a courtyard of a building can be seen at the bottom right corner (south) of the walled area, and the minarets of four mosques can also be seen around the town. In front of the nearest mosque is the town beach, which still exists. Among the buildings on the hill outside the walls, none stands out as being a church. The road leading northwards (to the left) from the town leads through a pass between the hills to the River Cayster and Ephesus. This road is still in use, although most traffic now uses the modern highway east of Kuşadası. |

|

|

| |

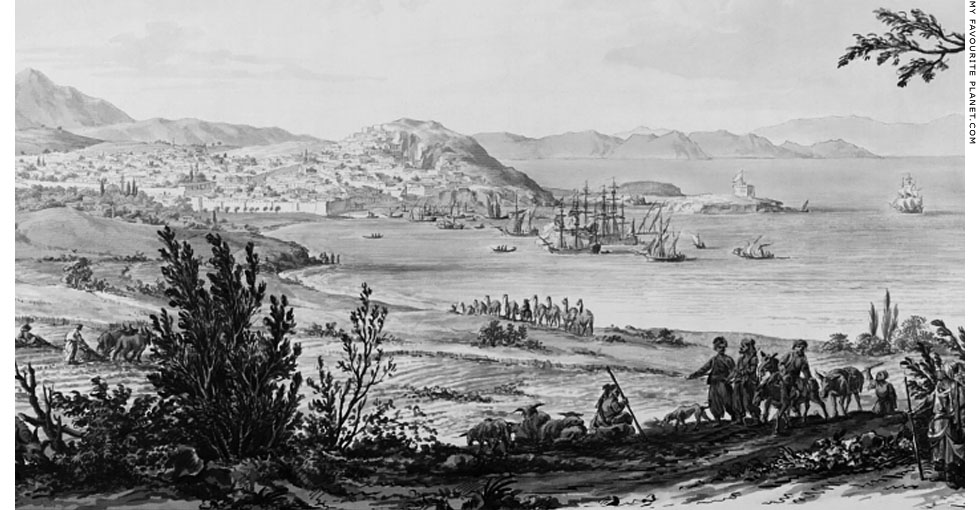

"Vue de Scala nova, port de mer en Asie". Detail of a drawing of Scala Nova

harbour made by the Polish architect Johann Christian Kamsetzer in 1777.

Graphite, black ink and grey wash on paper. Height 49.9 cm, width 71.2 cm.

Marked "Tab:XIII" at the top right of the sheet and "218" at the bottom left.

University of Warsaw Library. Inv. No. Inw.zb.d. 10090.

|

The architect Johann Christian Kamsetzer (or Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer, 1753-1795) was born and studied in Dresden, but spent most of his career in Poland, working from 1773 for King Stanisław II August (King Stanisław August Poniatowski, reigned 1764-1795). The king funded Kamsetzer's journey through Turkey and Greece from November 1766 to December 1777, and requested that the young traveller make drawings of everything "that might be fascinating and interesting" along the way. Arriving at Constantinople in February 1777, he travelled in the spring through western Anatolia and the Aegean islands. Among the places he visited and drew were Smyrna (Izmir), Ephesus, Samos and Scala Nova (Kuşadası). [9]

While many of Kamsetzer's studies of Greek and Turkish locations show his architectural training and interest in ancient, Byzantine and Ottoman buildings, others, such as this view of Scala Nova, are more generalized and picturesque. He also made coloured versions of his drawings on his return to Poland. Several of his works provide details of the landscapes and townscapes of the places he visited, as well as the clothing, living conditions and lifestyles of people of various social ranks. Travelling artists from the mid 18th century were able to provide their northern European patrons and public with more accomplished, accurate and attractive representations of people and places than the cruder woodcuts published by George Wheler (see note below) and Tournefort, and contributed to the romantic fascination with the East and the vogue of Orientalism.

This view shows several vessels of various sizes in the harbour. Although apparently drawn from a lower viewpoint than the Tournefort engraving ( see above), the walls and buildings of the town can also be seen, although you would have to take a magnifying glass to the original to identify individual buildings. It also shows that the tower on Güvercin Ada island was still not surrounded by walls at this period. The steep hill rising above the southern end of the bay is today known as Atatürk Hill or Gazibegendi Hill. In the foreground men tend goats and cattle, and on the left a man drives a plough pulled by oxen. In the centre a row of unladen camels are led down towards the town. |

|

|

| |

During the First World War Kuşadası was besieged by French forces, which surrounded the town on 18th May 1915 and began a long bombardment which eventually devastated it. In February 1916 The Turkish authorities forced around 4000 inhabitants of all religions to evacuate the town and move inland. In May another 800 families were evacuated by train to Denizli, and they settled there. Some of the evacuated people returned to Kuşadası following the ceasefire of 1918. [10]

The Ottoman dynasty ended with the First World War, after which much of Turkey was occupied by the Allies who began carving up the empire. Italy, which gained control of several Turkish territories including the Dodecanese islands (see History of Kastellorizo), occupied Kuşadası from mid April 1919 until 17th April 1922. Following the withdrawal of the Italians, the town was taken by soldiers of a Greek expeditionary force during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, caused by an ill-conceived Greek plan to reconquer Turkey and make it part of Greece. The campaign ended in disaster with the Greek army being driven out of Anatolia, and Greek soldiers were forced to leave Kuşadası in September 1922.

As a result of the Greco-Turkish War, the international Treaty of Lausanne, signed in 1923, caused a massive forced exchange of Muslim and Christian populations between the two countries. Most of the Greeks living in Ionia had to leave the area, and thousands of Turks resettled from Greece had to rebuild their lives there.

The young Republic of Turkey (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti), under its founder Kemal Atatürk, underwent sweeping social and political changes in order to meet the challenges of post-war conditions. As in other countries, the emphasis for much of the 20th century was modernizing and industrializing an economy mainly based on agriculture. From the middle of the century, growth in tourism became a major goal.

Since the 1970s Kuşadası has been developed as a tourist attraction, and has become increasingly popular over the last decade. It is also a port-of-call for many cruise ships whose passengers spend a day here, shopping, sightseeing and visiting local historical sites such as Ephesus (see Ionian spring part 1 at The Cheshire Cat Blog). |

|

A bronze statue of Kemal Atatürk

(1881-1938), founder of the modern

Turkish state, at Kuşadası harbour. |

|

| |

Kuşadası

Turkey |

Ancient Kuşadası - the debate |

|

|

|

Ancient scholars were evidently fascinated by geographical matters, an interest that continued into the Byzantine and Medieval periods. Debate concerning the location of ancient places began anew following the Renaissance and increased as ever more learned European travellers ventured further around the Mediterranean and Near East. During the 19th century, with the development of new methods of historical, topographical and archaeological research, a great number of theories were put forward concerning ancient sites, based on comparisons of inscriptions, coins and other evidence with reports in ancient books, many of which have survived only as fragments (see, for example, the History of Ancient Stageira parts 7 and 8).

Many ancient cities had been destroyed by war, earthquakes and other disasters, their buildings later used as sources of building materials elsewhere, and their ruins buried beneath centuries of accumulated earth and sand. While over 2000 years the alluvial deposits of rivers flowing into the Mediterranean had buried cities and extended coastlines considerably in many places, the sea level had risen over 2 metres, submerging parts of several other settlements. In some cases islands had become landlocked hills, while elsewhere hills had been transformed into islands. The topographical features described by ancient authors therefore appeared very different to Medieval and modern travellers and historians.

The ruins of ancient Ephesus were for centuries buried beneath silt and mud, however, it appears its location was never quite forgotten. The locations of some of the other large Ionian cities, such as Colophon, Teos, Miletus and Priene, were identified from the 17th century by early European travellers to the area, notably Spon and Wheler [11], Tournefort (see above), Charles Robert Cockerell and William Martin Leake. Many of their identifications were later confirmed by archaeological investigation, which in several cases provided a wealth of evidence.

Archaeological evidence for the location of many smaller settlements has proved more difficult to find. Mentions by ancient authors of such smaller places are brief, often unclear, and sometimes apparently contradictory. Archaeologists seldom find obvious evidence identifiying an ancient city, such as inscriptions saying something like "Phygela welcomes careful drivers", and so far no definitive archaeological evidence has been discovered to identify many of these places. In the case of Kuşadası, the port and surrounding area has been built over several times, and since the mid 20th century it has became densely covered by modern buildings, making excavation impossible. It has long been believed that it was once one of the towns along the Ionian coast, between Mount Mykale in the south and Ephesus to the north, listed by the Greek geographer Strabo (circa 64 BC - 24 AD). He was the only ancient author to mention all three of the settlements which since the 19th century became the theoretical candidates for the ancient name of Kuşadası: Neapolis (Νεάπολις, New City), Pygela (Πύγελα, or Phygela, Φύγελα) and Marathesion (Μαραθήσιον). See a 19th century map of the area below. The modern theories, based mainly on interpretations and combinations of literary testimony and topographical factors, remain speculative and continue to be debated.

"After the Samian strait, near Mount Mycale, as one sails to Ephesus, one comes, on the right [east], to the seaboard of the Ephesians; and a part of this seaboard is held by the Samians.

First on the seaboard is the Panionium, lying three stadia above the sea where the Panionia, a common festival of the Ionians, are held, and where sacrifices are performed in honor of the Heliconian Poseidon; and Prienians serve as priests at this sacrifice, but I have spoken of them in my account of the Peloponnesus.

Then comes Neapolis, which in earlier times belonged to the Ephesians, but now belongs to the Samians, who gave in exchange for it Marathesium [Μαραθήσιον, Marathesion], the more distant for the nearer place.

Then comes Pygela, a small town, with a temple of Artemis Munychia [Ἄρτεμις Μουνυχία or Ἀρτέμιδος τῆς Μουνιχίας], founded by Agamemnon and inhabited by a part of his troops. For it is said that some of his soldiers became afflicted with a disease of the buttocks [πυγαλγία, pygaglia], and were called 'diseased-buttocks' [Pygagleis], and that, being afflicted with this disease, they stayed there, and that the place thus received this appropriate name.

Then comes the harbor called Panormus [Πάνορμος, Panormos], with a temple of the Ephesian Artemis; and then the city Ephesus."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, section 20. At Perseus Digital Library. [12]

The Roman geographer Pomponius Mela (mid 1st century AD) and Pliny the Elder (probably taking at least part of his information from Mela) referred to Pygela as Phygela (Φύγελα), from the greek word phyle (φυλὴ), meaning flight or desertion.

"After that, bending in again, the coastline goes around the city of Priene and the mouth of the Gaesus River, and then, the bigger its circuit, the more it embraces. The Panionium is there. It is a sacred district and, for that reason is so designated because the Ionians tend it in common.

There founded by fugitives, as they say (and the name agrees with the report) is Phygela. Ephesus is there, and the most renowned temple of Diana, which the Amazons, rulers of Asia, are reported to have dedicated. The Cayster River is there."

Pomponius Mela, de Chorographia, Book 1, sections 87-88. At ToposText.

"Upon that part of the coast which bears the name of Trogilia is the river Gessus. This district is held sacred by all the Ionians, and thence receives the name of Panionia. Near to it was formerly the town of Phygela, built by fugitives, as its name implies, and that of Marathesium.

Above these places is Magnesia [Magnesia on the Maeander], distinguished by the surname of the 'Maeandrian', and sprung from Magnesia in Thessaly. It is distant from Ephesus fifteen miles, and three more from Tralles [Tralleis, near modern Aydin]."

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 5, chapter 31. At Perseus Digital Library.

It has been suggested that Strabo's story about "diseased buttocks" may have been an anecdote punning Pygela's name, although according to another suggestion, Mela and Pliny's "fugitives" at Phygela, perhaps equally anecdotal, may have been deserters from the army of Agamemnon at the time of the Trojan War. The inhabitants of Pygela are referred to as Pygeles (Πυγελες) on the 5th century BC Athenian tribute lists of the Delian League. The tale is reminiscent of those concerning the military campaign of Alexander the Great, who is said to have left sick and wounded veterans to found towns in Asia (see History of Stageira & Olympiada Part 6). Veterans of Attalus I of Pergamon's garrison on Aegina purchased the island and settled there (see History of Pergamon).

Pygela was also briefly mentioned by other authors, including Xenophon of Athens (circa 430-354 BC; Hellenica, Book 1, chapter 2), and Titus Livius (Livy, circa 64 BC - 17 AD; The History of Rome, Book 37, chapter 11), although they do not provide any information about the port or its location [13]. It appears to have gained some form of autonomy during the 4th century BC, and issued its own coins around 400-281 BC. Examples of bronze and silver coins show the head of a female, believed to be Artemis Mounychia, and on the other side is a standing bull and the inscription "ΦYΓEΛEΩN", ΦY (PHY), ΦYΓ (PHYG) or ΦY-ΓE (PHY-GE). An inscription found at Ephesus indicates that shortly after it was under the control of Lysimachos (circa 360-281 BC), one of the successors of Alexander the Great. [14]

Pliny does not mention Neapolis, and implies that Phygela not longer existed in his time (mid 1st century BC), although Pedanius Dioscorides, writing around 50-70 AD, recommended a wine "which grows in Ephesus, called phygelites". [15] Pygela was mentioned as an Ionian city by Stephanus of Byzantium, Michael Attaleiates and in the Suda in the Byzantine period, but the references may have been historical rather than actual. [16]

According to Strabo's description the order of the places along the coast between Panionion and Ephesus (south to north) were:

Neapolis, Pygela, Panormos.

The position of Marathesion relative to the other three places is unclear, but the term "the more distant for the nearer place" is presumed to mean that Neapolis was nearer to Samos, and Marathesion nearer to Ephesus. Pliny's report may lead us to think that Phygela was closer to Panionion (i.e. further south) than Marathesion.

Strabo, Mela and Pliny did not mention Anaia (Ἄναια), another city along the coast, mentioned by Pseudo-Scylax [17].

Unfortunately, some of the other sources usually helpful in identifying ancient places are silent concerning settlements along this stretch of coast. For example, no settlement is marked on or near the coast between Ephesus and Miletus on the Tabula Peutingeriana. [18]

It is thought an Ionian settlement known as Neapolis (Νεάπολις, New City) was founded on the Yilanci Burnu headland (see Kuşadası gallery page 10), although it seems that so far very little archaeological exploration has taken place here to substantiate this theory.

To be continued ...

As you can see, the reports and theories concerning the geography of various ancient locations around Ephesus and Kuşadası present a complex and involved puzzle. Since first writing this article I have found several further references to and arguments on the subject from various sources. Unfortunately, I have yet to find the time to include them all, particularly since it would involve not only rewriting the article but also restructuring the entire page.

We welcome your opinions and thoughts on the subject. Get in contact. |

|

|

| |

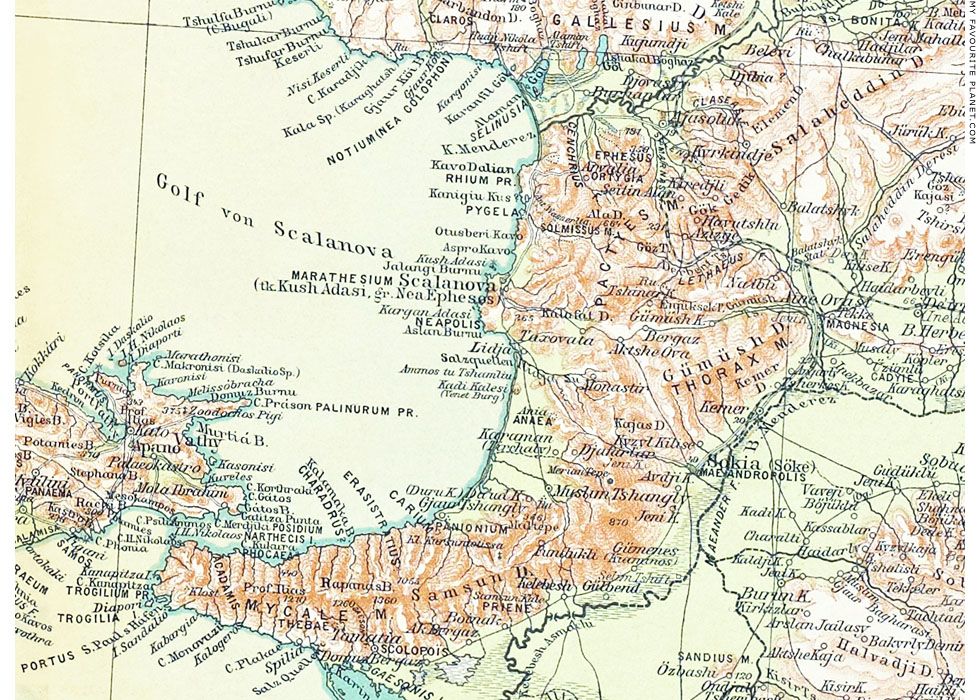

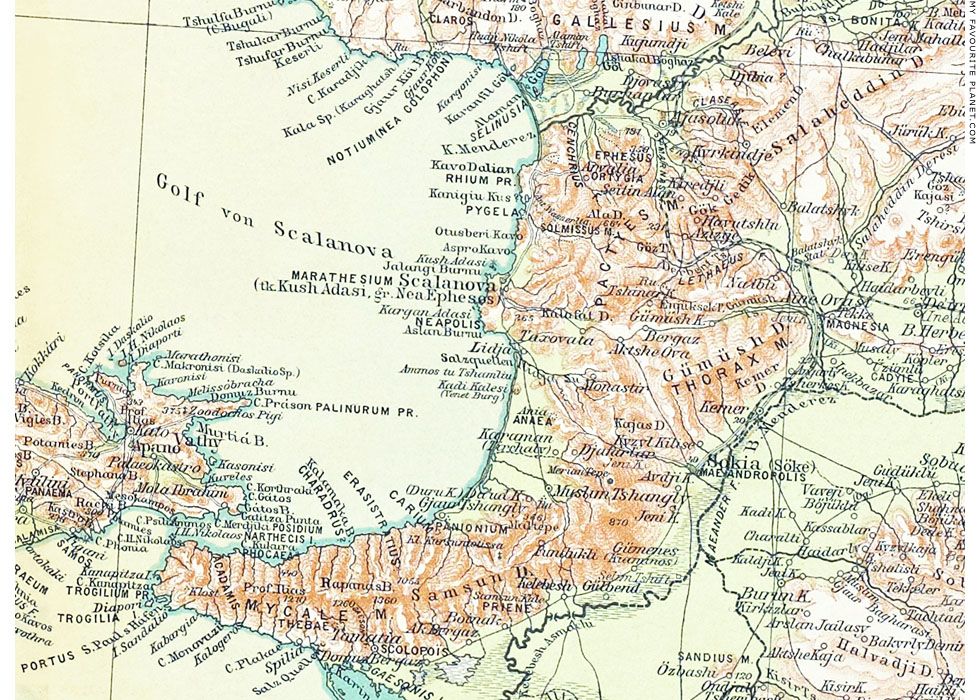

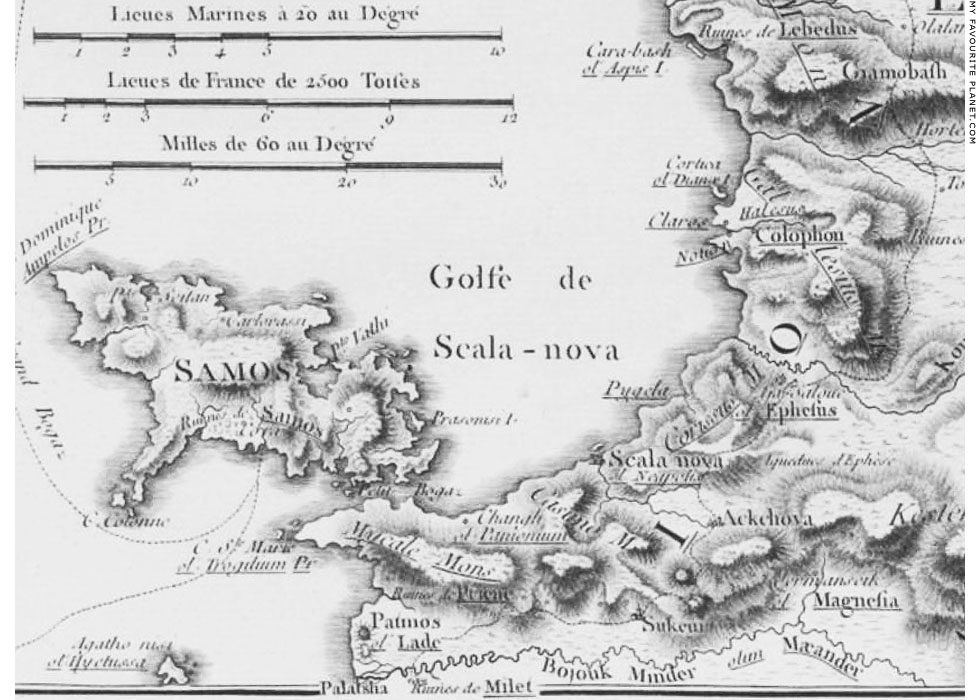

A map of the Ionian coast around Kuşadası, between the River Cayster in the north to the

River Maeander in the south, by the German cartographer Richard Kiepert (1846-1915).

|

Richard Kiepert was one of the 19th century scholars who attempted to identify ancient locations based on available evidence. He continued the work of his father, the geographer and traveller Heinrich Kiepert (1818-1899), who made pioneering historical maps of Anatolia, Karte von Kleinasien, 1843-1845. The Kieperts' speculative identification of ancient places was based on comparing their own observations during visits to Turkey with reports by ancient and Medieval authors as well as the theories of other travellers, historians and archaeologists. Over a century later, these identifications have still not been confirmed beyond dispute.

Source: Richard Kiepert, Karte von Kleinasien, Blatt C1 Smyrna. Dietrich Reimer, Berlin, 1911 (2nd Edition). At the New York Public Library Digital Collections. |

|

Kiepert's identification of ancient coastal settlements south of the Küçük Menderes tiver (River Cayster) and Ephesus:

"Pygela"

"Marathesium, Scalanova (Turkish, Kush Adasi; Greek, Nea Ephesos)"

"Neapolis" between Kargan Adasi and Aslan Burnu

"Ania" at "Anea", a little inland, northwest of Karaman

(Söke or "Sokia", inland, east of Karaman and north of the Maeander valley, is marked as "Maeandropolis"

"Panonium" and "Carium", just south of "Tshangly" |

|

|

| |

A 1908 sketch map of the Ionian coast around Kuşadası, between Ephesus and the

River Cayster in the north and Priene and the River Maeander in the south, by the

Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil (see Selçuk gallery 2, page 4) after Theodor Wiegand.

Image source: Josef Keil, Zur Topographie der ionischen Küste südlich von Ephesos (On the topography of the Ionian

coast south of Ephesus). In: Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien, Band XI,

Beiblatt, Spalten (columns) 135-168, Fig. 92. Alfred Hölder, Vienna, 1908. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

A map of Ephesus and the River Cayster from Joseph Pitton de Tournefort,

Relation d'un voyage du Levant, 1717, page 513 (see above). |

| |

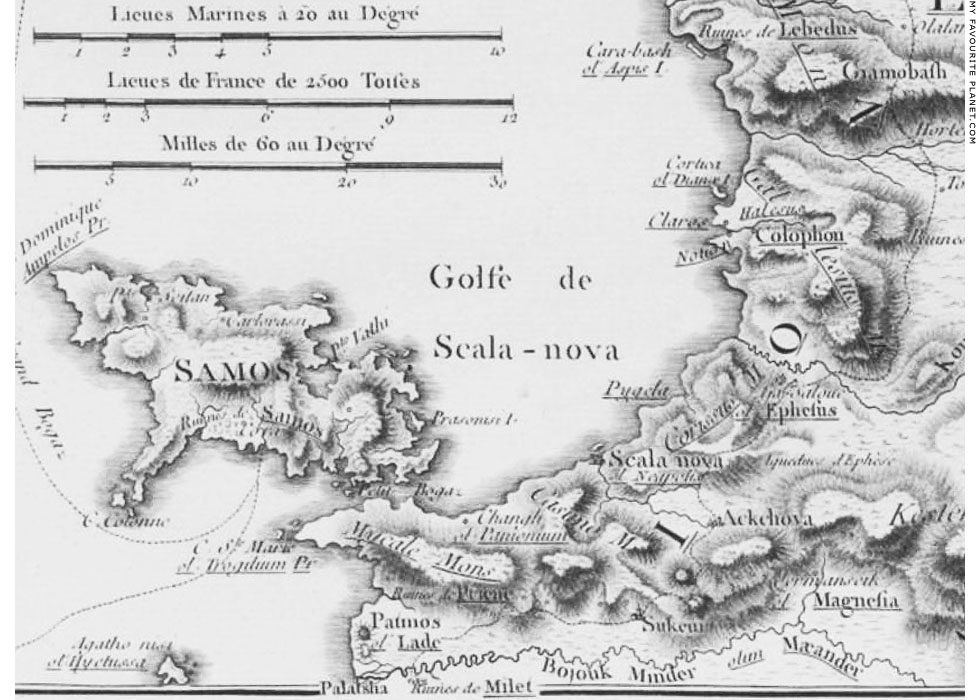

A map of the Ionian coast around Kuşadası, between the the ruins of Lebedos in

the north to the River Maeander in the south. Detail of a map the route taken in

1776 by the French diplomat and traveller Choiseul-Gouffier (1752-1817) along the

west coast of Anatolia, from the Maeander northwards to the Gulf of Adramyttium.

|

"Après y avoir pris quelques heures de repos, nous continuâmes de marcher vers le Nord & nous passàmes à la hauteur de Scala Nova que nous apperçûmes de loin. Cette Ville autrefois Neapolis, apportenoit aux Samiens, qui l'avoient reçue des habitans d'Ephèse, en échange de la ville de Marathesium plus à la convenance de ces derniers (Strabo Lib. XIV). Elle est aujourd'hui assez bien bâtie; les côteaux qui l'environnent produisent d'excellens vins, & elle est habitée par un affez grand nombre de Marchands Grecs, Juifs & Arméniens. Nous marchâmes encore quatre heures, & une lieue avant d'arriver à Ephèse, nous passàmes fous un très-bel aquéduc, que les Planches suivantes seront connoître."

Source: Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste, Comte de Choiseul-Gouffier, Voyage Pittoresque de la Grece, Tome 1, chapitre XII, planche 117, opposite page 187. Text on pages 187-189. Paris, 1782. At the Internet Archive. |

|

|

| |

Kuşadası

Turkey |

Area map |

|

|

|

Map of north-western Turkey and the Aegean area.

See a larger interactive map of this area. |

| |

Kuşadası

Turkey |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

1. Byzantine "Neopolis"

Although many modern sources (in print and on the web) state that Kuşadası was known as Neopolis (Νεόπολις) or Ephesus Neopolis (Ἔφεσος Νεόπολις) during the Byzantine period, they provide no references or citations as evidence. One would imagine that the names of towns would be recorded in official documents, however surviving historical records concerning the area from the Byzantine and Ottoman periods are difficult to access. So far I have found no mention to this name in a Byzantine period document, or even a reference to one in a modern work. If you have any further information, please get in contact.

The claim that there was a city known as "Nova Ephesus" appears to be a misinterpretaion of the phrase "... prope novam civitatem Ephesi" (near the new city of Ephesus) used by the German priest and traveller Ludolf von Sudheim (or Ludolph von Suchem). De itinere ad terram sanctam (On the itinerary to the Holy Land), his account in Latin of his pilgrimage through the Eastern Mediterranean to the Holy Land in 1336-1341, was written around 1345-1361 (various dates have been suggested by scholars, the oldest known of 44 manuscripts is dated around 1380).

Ludolf distinguished between the ancient name of Ephesus and that of Theologos, the later settlement around the church of Agios Theologos (Άγιος Θεολόγος, Holy Theologian), outside the area of the Roman period city. He also wrote that when he was there the place was called "Altelot", which he took to be from the Latin "altus locus" (high place), but was presumably his undestanding of Ayasluğ (or Ayasluk), the Turkish name for Agios Theologos which was also mentioned by other European visitors and which remained the name of the village until 1914. It was changed to Selçuk in commemoration of the Seljuk Turks. The place is referred to in Medieval Italian portolane, seacharts and sets of navigational instructions, as Alta Luogo, Altoluoco or Altologo. Ludolf's phrase "the new city of Ephesus", is descriptive, and he did not say that this was the name of the place.

Ludolf von Sudheim on the name of Ephesus and the new city:

"Et est sciendum, quod illa civitas, quae olim Ephesus dicebatur, postea Theologos appellata est a Graecis, et nunc Altelot, id est altus locus, vocatur, quia ad altiorem locum circa ecclesiam, ut dixi, civitas est translata.

Ab hac civitate antiqua Ephesi supra littus maris ad quatuor miliaria in loco, quo est portus, nunc nova civitas est constructa, et a Christianis de Lumbardia per discordiam expulsis est inhabitata, qui habent ecclesias et fratres minores, ut Christiani viventes, licet tarnen prius Christianis maxima damna cum Turchis intulerunt.

Prope novam civitatem Ephesi est fluvius in modum Reni magnus, de Tartaria per Turchiam descendens; per istum fluvium, ut in partibus his per Renum, varia et diversa deveniunt mercimonia. In eodem fluvio Turchi et falsi Christiani, dum contra Christianos intendunt pugnare, navigia et arma ac cibaria solent congregare. Ex hoc etiam fluvio Christianis multa damna evenerunt et detrimenta."

Ludolphi, rectoris ecclesiae parochialis in Suchem, De itinere terrae sanctae, page 24-25. Bibliothek des litterarischen Vereins, Band XXV. Literarischer Verein, Stuttgart, 1851. At Paderborn University Library. Spelling and punctuation as they appear in the edition.

An English translation:

"You must know that the city, which once was called Ephesus, was afterwards called Theologos by the Greeks, and is now called Altelot, that is, High Place (altus locus) because, as I have already told you, the city has been removed to a higher place round about the church.

About four miles from this ancient town of Ephesus a new city has now been built, on the sea-shore at a place where there is a harbour, and it is inhabited by Christians who have been driven out of Lombardy through a quarrel. These people have churches and Minorite friars, and live like Christians, albeit they did in former times together with the Turks do great injury to Christian people.

Near the new city of Ephesus there is a river as large as the Rhine, which runs down through Turkey from Tartary. By this river much merchandise of divers sorts is brought down, even as is done on the Rhine in these parts. It is in this river that the Turks and Christians falsely so called, when they have a mind to fight against the Christians, are wont to collect their ships, arms, and provisions, so that from this river much harm and damage has come to the Christians."

Aubrey Stewart (translator), Ludolph von Suchem's Description of the Holy Land and of the Way Thither, written in the year A.D. 1350, chapter XVIII: The city of Ephesus, pages 30-31. In Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society, Publications, Volume 12, London, 1895. At the Internet Archive.

A translation into Low German, published around 1470:

"Es ist auch gewissen dz die Stat die vor Zeite Ephesi geheyssen waz ist darnach Theologos geheissen worde von den Kriechen und heysset nun Altetot dz ist Hoch. Wan die Stat ist eyn höher Ort da die Kirch stet gesetzet worden.

Vo de'selben alte stat Ephesi vier klein Meyl an dem End do das gepozt ist, ist ein newe Stat gebawe und von Christen auß Lombardia vertriben eynwonber. Unnd hat Kirchen und barfüßer Munch die cristenlich lebent, wie wol sy vor den Christe mit den Türcken groß Schaden habent getan. Und bey der newen Stat Ephefi ist eyn Fluß in Massen wie d' Reyn groß und kombt auß d' Tartari duech die Turcky."

De itinere ad terram sanctam (printed in German, circa 1470), Capi. XXX: von d' Stat Epheso. At Europeana. Spelling and punctuation as they appear in the edition. I have capitalized nouns and names, as in modern German.

My translation:

"It is also known that the city in former times known as Ephesus was after called Theologos by the Greeks, and is now called Altetot (that is, high), since the city is a higher place than where the church stood.

Four small miles from the same old city Ephesus at the end of where it is situated, a new city has been built and is inhabited by Christians who were driven from Lombardy. It has churches and barefoot monks who live as Christians, although they have with the Turks done great injury to Christian people. And near the new city Ephesus there is a river as large as the Rhine, which flows from Tartary through Turkey."

Clive Foss, who has written one of the most influential modern books on the history of Ephesus from Late Antiquity onwards, was adamant that the new town to which Ludolf referred was Panormos, and not Scala Nova or Phygela, and that Scala Nova was not named "Nova Ephesus":

"The passage by Ludolf does not, as has been generally supposed, refer to Scalanova, the Turkish Kuşadası and the ancient Phygela, which was some ten miles further south. In this period, and for some centuries subsequently, Scala nova is regularly called Phygela, or some form of it, on the Italian maps. It is not referred to as 'nova Ephesus' in the Middle Ages, nor is it located anywhere near a large river."

Clive Foss, Ephesus after Antiquity: A Late Antique, Byzantine, and Turkish city, page 150, note 32. Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Foss cited Tournefort's map of Ephesus and the plain of the River Cayster (see above), to show that a channel of the river still flowed to the sea as late as 1700. However, the map does not show any remains of a port along the river, nor does his text mention any. The location of Panormos has not been discovered by archaeologists. While it may be understandable that more ancient ruins had become buried deep beneath the silt, it appears less likely that all vestiges of an entire port city could have diappeared in two centuries. Richard Chandler (1737-1810), who visited Ephesus in 1765, suggested that Panormos may have been the general name of the entire harbour of Ephesus:

"Panormus, it is likely, was the general name of the whole haven, and comprised both the Sacred Port, or that by which the temple stood, and the City Port, now the morass."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Asia Minor and Greece, Volume 1 (of 2), chapter XXXVII, page 164. 2nd edition. Clarendon press, Oxford, 1825. At the Internet Archive.

Some of the assertions made by Foss have been refuted in articles by those who have conducted more recent research in the area. He cited as a "crucial text" for his argument (which is confined to a single footnote) the detailed sailing instructions to the port in the Portolan of Bernardino Rizo, a collection of sailing directions in Italian, written by an anonymous "Venetian gentleman" ("zentilomo veniciano") and published in Venice by Bernardino Rizo in 1490. Unfortunately, Foss did not provide a translation, and neither for the moment can I, except to note that Ephesus is named "efexo", that the castle ("chastello") and the church of Agios Theologos ("la chiexia de san zuoane vangelista", the church of Saint John the Evangelist) stood at "Alto luogo", and that its port was one and a half miles away.

"Alto luogo si e infra terra mia 6 et e chastello la e la chiexia de san zuoane vangelista e dal cavo dalto luogo la e la foxa di efexo.

Efexo si e una gran citade desfacta che e apresso alto luogo a mio uno e dala foxa di efexo fin al statio dele nave entro ostro e garbin mio uno e mezo.

In quel statio sta le nave che va in alto luogo ed e choverto da garbin fin ala tramontana fazando la volta da levante ed e fondi da passa 6 e 8 e meti li prodexi dal ostro. La cognoscenza de statio si e una tore che e sovra un monte alto, lassala un poco dal tramontana e va entro la tore e un cavo alto che tu vederai che beve in aqua che e a cavo dela spiaza.

De la foxa de efexo a figella entro ponente e garbin mia 10.

Entro figella e chipo che e chavo de anea sie lixola che a nome chipo e soura lo chavo de chipo sie una secha e volzando de verso levante e statio entro chipo e anea mio mezo.

anea a apresso lo statio dele nane verso levante mia 2 e mezo."

Portolano per i naviganti, cap. 247. Bernardino Rizo de Novaria, Venice, 1490. In: Konrad Kretschmer (1864-1945), Die italienischen Portolane des Mittelalters: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kartographie und Nautik, page 521. Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Meereskunde und des Geographischen Instituts an der Universität Berlin, Heft 13, Februar 1909. Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, Berlin, 1909. At Harvard Library.

2. Richard Chandler on Kuşadası

Chandler referred to Kuşadası as "Scala Nova" and, like George Wheler (see note below), believed it to be the location of Neapolis. As he and his companions were on their way from "Aiasaluck" (Selçuk) to Scala Nova, he saw some ruins of a small town on a hill south of the mouth of the river Cayster, north of Scala Nova, which he took for Pygela or Phygela. He recalled that "the wine of Phygela is commended by Dioscorides [see note below], and its territory was now green with vines", and noted that "we met a peasant on an ass laden with grapes, and purchased some of admirable flavour".

Like Joseph Pitton de Tournefort before him (see note below), he remarked on the goatskins at Kuşadası, which were prepared for trade. Also, like many travellers before and after him, he complained of some terrible hans or caravanserais (see note below) in Turkey. His positive verdict of the han at Kuşadası was therefore praise indeed.

"Scala Nova, called by the Turks Koushadase, is situated in a bay, on the slope of a hill, the houses rising one above another, intermixed with minarets, and tall slender cypresses. A street, through which we rode, was hung with goat-skins exposed to dry, dyed of a most lively red. At one of the fountains is an ancient coffin, used as a cistern. The port was filled with small craft. Before it is an old fortress on a rock or islet, frequented by gulls and sea-mews. By the water-side is a large and good khan, at which we passed a night on our return. This place once belonged to the Ephesians, who exchanged it with the Samians for a town in Caria."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Asia Minor, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, chapter XL. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1775.

3. Grand Vizier

The Turkish word Vizier comes from the Arabic "wazir", bearer of burdens. The office of Grand Vizier as prime minister to the Ottoman sultan became increasingly important as the political and military complexities of ruling the huge empire grew, and especially when young or inexperienced sultans ascended to the throne.

4. Caravanserai or han

The Persian word caravanserai means literally "caravan palace"; in Turkish kervansaray or han (from Persian khan); in Arabic funduq.

The Seljuk Turks built the first hans in Anatolia soon after their arrival at the end of the 11th century. The earliest known Turkish han is thought to have been built around 1210 by Sultan Ghiyath ad-Din Kaykhusraw I (ruled 1192–1196, and again 1205–1211).

Hans also served many other functions, including headquarters for travelling sultans and officials, barracks for campaigning troops, jails and postal stageposts.

See Katharine Branning's informative website about Seljuk hans in Anatolia: www.turkishhan.org |

|

|

5. Railways in Ionia

William Mitchell Ramsay (1851-1939), The historical geography of Asia Minor, page 59. Royal Geographical Society Supplementary Papers, Volume 4. John Murray, London, 1890. At the Internet Archive.

For further information about Turkish railways, see the following websites:

www.tcdd.gov.tr

Turkish State Railways website, in Turkish and English.

www.seat61.com/Turkey2.htm

Information about train travel within Turkey.

www.trainsofturkey.com

A wiki site for Turkish railways enthusiasts, including history and maps.

Run by Jean-Patrick Charrey in Paris, France.

6. The Jewish community in Scala Nuova

"Scala Nova (Turkish, Kuch Adassi): Important city of Anatolia opposite the island of Samos; seaport of Ephesus. The oldest epitaph in the Jewish cemetery is dated 1682; but the town evidently had Jewish inhabitants in the thirteenth century, for in 1307 a number of Jews removed from Scala Nova to Smyrna, a similar event occurring in 1500. At the time of the expulsion from Spain 250 Jewish families went to Scala Nova; and a number of the local family names are still Spanish.

In 1720 the plague reduced the number of families to sixty (Meserit, v., No. 39); and Tournefort, who visited the city in 1702, found there only ten families and a synagogue (Voyage au Levant, ii. 525, Paris, 1717). In 1800, when an epidemic of cholera caused many Jews to emigrate, there were 200 families in Scala Nova, and in 1865, when a second epidemic visited the city, there were still sixty-five families there. In 1816 Moses Esforbes was the chief of customs for the town, while Isaac Abouaf was city physician for several years, and Moses Faraji and Moses Azoubel were municipal pharmacists.

At present (1905) the Jewish population consists of thirty-three families, some of them immigrants from the Morea [Peloponnese] after the Greek Revolution of 1821. The majority are real-estate owners and have some vines; but the only mechanics are tinsmiths.

The synagogue, erected by Isaac Cohen in 1772, was rebuilt by Joseph Levy in 1900. The community likewise possesses a Talmud Torah, directed by a rabbi who officiates also as shoḥeṭ and ḥazzan. The gabel is enforced. A false charge of ritual murder was brought against the Jews about the middle of the nineteenth century; and a certain amount of anti-Semitism is generally manifested at Easter."

Gotthard Deutsch, Abraham Galante, "Scala Nova (Turkish, Kuch Adassi)", in: The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume XI, page 91, Funk and Wagnalls, New York and London, 1905. At the Internet Archive. |

|

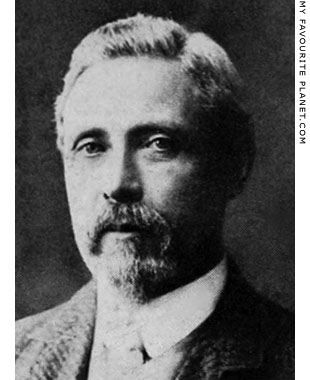

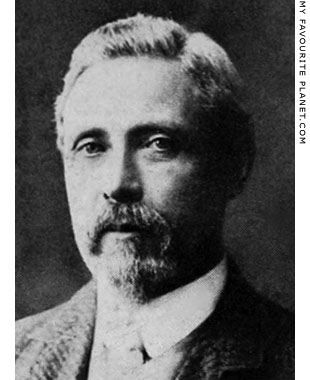

William Mitchell Ramsay (1851-1939),

archaeologist and New Testament scholar.

Source: Camden McCormack Cobern,

The new archeological discoveries

and their bearing upon the New

Testament and upon the life and

times of the primitive church,

page 356. Funk and Wagnalls,

New York and London, 1917.

At the Internet Archive. |

|

7. The church and synagogue of Scala Nuova

It appears that the church or synagogue in Kuşadası no longer exist, and so far I have discovered little information about their history or fate. They may have been destroyed by the French naval bombardment in 1915 which devastated the town. One of the few recent references to the church is a mention of an inscription recorded by the Greek Byzantist Georgios Lampakes (Γεώργιος Λαμπάκης, 1854-1914) in the early 20th century, which recorded the building or restoration of a church dedicated to Saint George in 1019. The stone had been reused in the wall of a later church, built around 1792.

The inscription was first published in: Γεώργιος Λαμπάκης, Οι επτά αστέρες της αποκαλύψεως. Ήτοι ιστορία, ερείπια, μνημεία και νυν κατάστασις των επτά εκκλησιών της Ασίας Εφέσου, Σμύρνης, Περγάμου, Θυατείρων, Σάρδεων, Φιλαδελφείας και Λαοδικείας, παρ' η Κολοσσαί και Ιεράπολις (Georgios Lampakes, The Seven Stars of the Apocalypse. The history, ruins, monuments and current status of the seven churches of Asia: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamon, Thyateira, Sardis, Philadelphia and Laodicea, near Kolossi and Ierapolis), page 126. τύποις Κράτους, Θ. Τζαβέλλα, Athens, 1909.

It was also published in: Henri Grégoire, Recueil des inscriptions grecques chrétiennes d'Asie Mineure, nr. 115/3. Paris, 1922.

See:

Clive Foss, Ephesus after Antiquity: A Late Antique, Byzantine, and Turkish city, page 124. Cambridge University Press, 1979.

M. Whittow, Social and political structures in the Maeander region of Western Asia on the eve of the Turkish invasion, page 113. PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1987.

I have not yet found a photo or drawing of this inscription or a transcription of the text, so I do not know whether it mentions "Phygela". Even if it does, this is not necessarily proof that Kuşadası stands on the site of ancient Phygela. A monastery of Saint George Dyssikos at Phygela is recorded as being annexed by Patmos around 1201-1216. It is conceivable that the inscription was taken to Kuşadası from the monastery church.

See: Angeliki Katsioti, Between princes and labourers: The legacy of Hosios Christodoulos and his successors in the Aegean Sea (11th-13th centuries). In: Emmanuel Moutafov and Ida Toth (editors), Byzantine and post-Byzantine art: Crossing borders art readings, Thematic peеr-reviewed Annual in Art Studies, Volumes I–II, 2017.I – Old Art, pages 91-128 (particularly page 100). Sofia, Bulgaria, 2018. PDF at artstudies.bg.

For a historical overview of the Greek community in Kuşadası, see:

Kuşadası, at the Online Encyclopaedia on the Greeks in Asia Minor, part of the Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World. This entry mentions that "the renovated Church of St. George first operated on April 23, 1792". The Greek Orthodox community was assisted in its building by Manolakis Benli Oğlu, and the architect was Chatze-Antonakis, who also designed the Church of the Virgin Mary at Ano Vathy, Samos.

Σ. Ε. Παπαδόπουλος, Νέα Έφεσος (Stephanos Emmanuel Papadoulos, Nea Ephesos). Athens, 1965.

8. Tournefort on his visit to Scala Nuova

The English version of Tournefort's report is based on the 1718 translation by John Ozell, which I have slightly modified for the modern reader.

"We left Ephesus on 27th January to see this last place, which the Turks call Consada and the Greeks Scalanova, the Italian name given to it by the Franks, perhaps after the destruction of Ephesus. What is observable in the change of the name is, that it answers to the ancient name of this city, which is the Neapolis of the Milesians. Despite the heavy rain, we arrived in there three hours.

When one is near the ruins of the Temple of Ephesus, one must go directly to the south, then to the southeast, to reach the sea. From there one takes to the left at the foot of the hills, where the Prison of Saint Paul stands, leaving to the right the marsh, which empties into the Cayster. This way is very narrow in many places, because of the winding river which beats against the foot of the mountains, after which it runs directly into the sea. One can hardly discern the way because of the great quantity of tamarisk and Agnus Castus. The road of Ephesus terminates at this place, which is to the southwest, by a cape which one must leave on the right, and upon which one must pass to take the way to Scalanova. At length one comes to the shore, from where one discovers the Cape of Scalanova, which extends much farther into the sea.

Two miles on this side this city one passes through the breach of a great wall, which, as they pretend, served as an aqueduct to carry the water to Ephesus; but there are no arches. One sees however the continuation of the wall, which approaches to the city, around the contour of the hills.

The Avenues to Scalanova are very pleasant due by their vineyards. They carry on a considerable trade in red and white wines, and dried raisins. They also prepare a large quantity of goatskins (peaux de marroquin, Spanish leather).

Scalanova is a very pretty town, well built, well paved, and covered with hollow tiles like the roofs in our towns in Provence. Its perimeter is almost square, and such as the Christians built it. There live only Turks and Jews. The Greeks and Armenians inhabit the suburbs (les fauxbourgs) only. One sees a great many old marbles in this city.

The church of Saint George of the Greeks is in the suburbs, upon the brow of a hill which encompasses the port ; over-against it is a ledge on which they have built a square castle, where they keep a garrison of twenty soldiers. The port of Scalanova is a naval station, and looks towards the west and northwest.

There are about a thousand families of Turks in this city, six hundred families of Greeks, ten families of Jews, and sixty of Armenians. The Greeks have there the church of Saint George, the Jews a synagogue, the Armenians have no church. The Mosques there are small. They maintain in and about the city not above one hundred Janissaries. Their trade is not considerable, because they are prohibited from loading any goods for Smyrna; so that they only load wheat and haricot beans. There is in this place a cadi, a disdar, and a sardar.

They reckon it but one day's Journey to Tyre, as much to Guzetlissar, or Fine Castle, which is the famous Magnesia on the Meander, one and a half days' journey from the ruins of Miletus."

See: Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, A voyage into the Levant Volume II (of 2), pages 396-397. Translated by John Ozell. London, 1718. At the Internet Archive.

9. Johann Christian Kamsetzer's travels 1776-1777 and 1780-1782

Most of the drawings and watercolours Kamsetzer made on his travels are now in the collections of the National Museum in Warsaw and the National Museum in Krakow. Several of the drawings he made in Turkey were shown in a special exhibition prepared by the Warsaw museum, Orientalism in Polish Art, in the Pera Museum, Istanbul, 24 October 2014 - 18 January 2015.

See:

Zygmunt Batowski, Podróże artystyczne Jana Chrystjana Kamsetzera w latach 1776-1777 i 1780-1782, in Polish with a summary in German: Johann Christian Kamsetzers Kunstreisen in den Jahren 1776-1777 und 1780-1782 (Johann Christian Kamsetzer's artistic travels in the years 1776-1777 and 1780-1782). In: Prace Komisji Historji Sztuki, Tom VI, page 165-208. Polska Akademja Umiejętności, Krakow, 1935. PDF at the Silesian University of Technology Digital Library, Gliwice, Poland.

A summary of Batowski's article in French: Zygmunt Batowski, Podróże artystyczne J. C hr. Kamsetzera w latach 1776-7 i 1780-2 (Le voyages de J. Ch. Kamsetzer, entrepris de 1776 à 1777 et de 1780 à 1782 en vue d’études artistiques). Séance du 17 mai 1934. In: Bulletin international de l'Académie polonaise des sciences et des lettres, Classe de de Philologie, Classe d'Histoire et de Philosophie, No. 4-6. I-II. Avril-Juin 1934, pages 95-99. Impremerie de l'Université, Krakow, Poland, 1934. PDF at the Digital Repository of Scientific Institutes (RCIN).

Marzena Królikowska-Dziubecka, Listy z podróży: Korespondencja Jana Chrystiana Kamsetzera z królem Stanisławem Augustem i Marcellem Bacciarellim 1776-1777, 1780-1782, 1787 (Letters from the journey: Correspondence of Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer with King Stanisław August and Marcell Bacciarelli). 498 pages, with maps and colour illustrations. Muzeum Łazienki Królewskie, Warsaw, 2017.

10. Kuşadası during the First World War

See: Kuşadası, at the Online Encyclopaedia on the Greeks in Asia Minor

11. Spon and Wheler in Ionia

The French doctor and antiquarian Jacob Spon (1647-1685) and the English botanist (and later clergyman) George Wheler (1650-1723) travelled together through Italy to Greece, Constantinople (Istanbul) and Anatolia in 1675-1676. Using Smyrna (Izmir) as a base, they visited several ancient sites in the area, including Ephesus, but were only able to stay there for one and a half days due to the threat of bandits, and did not venture further south.

In his account of their journey, Wheler related the report of Dr Benjamin Pickering, a doctor of Levant Company in Smyrna, and Jerome Salter, a factor (merchant) of the company, who were part of a group of European merchants which in 1673 had travelled from Smyrna along the Ionian coast, through Scala Nova and Changlee (Güzelçamlı), and on to the valley of the Maeander river.

"Hence I shall take for my guide, an account given me of a journey made by Dr Pickering, Mr Salter, and several other merchants, there begun June 23, 1673.

The first day, after nine Hours riding, they came to a village, called Chillema, south of Smyrna, not far from the foot of the mountain Aleman; and lodged that night in their tent, by a fountain; but were much infested by frogs and flies.

The next day, through a bushy, rocky, and mountainous way, they came to the top of the Aleman; which I esteem the Mountain Gallecius. Whence they had the prospect of the Ephesian plains; and after twelve hours riding the second day, they came to Scala Nova, I suppose, after the Ephesian plains; because they spent so much time, going to it. It is a garrison town, situate in the bottom of a bay: most of the inhabitants, out of town, Greeks; the rest Turks. There was formerly a factory of French, setled there; but were removed to Smyrna, by order of the Sultanes Mother; so that now there is but small trade. I guess this to be the Neapolis, Strabo placeth hereabouts."

George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book III, page 267. William Cademan, Robert Kettlewell, and Awnsham Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks.

Read more about Spon and Wheler on Athens Acropolis gallery page 12.

See also Wheler on Pickering and Salter's visit to Changli (today Güzelçamlı, near the site of ancient Panionion) on Samos gallery page 29.

12. Strabo on Neapolis

According to the footnotes of this modern edition, Marathesium (Μαραθήσιον) was Scala Nuova. Also on Pygela: "Pliny and Mela give a different origin and name to this town: by them it is called Phygela [Φύγελα] from φυλὴ, flight or desertion of the sailors, who, wearied with the voyage, abandoned Agamemnon."

The 19th century traveller and topographer Colonel William Martin Leake believed that Scala Nuova was the site of Marathesium, and that the ancient remains about halfway between Scala Nuova and the Greek village of Tshangli or Changli (today Güzelçamlı) belong to ancient Neapolis.

"Several travellers in passing from Ephesus to Skalanova have remarked the ruins of a small town near the sea, at about one-third of the distance from the former place to the latter. These are probably the remains of Pygela; though I am not aware how far the neighbouring coast will answer to Livy’s description of Pygela as a harbour [see note 13].

Between this spot and Tshangli there are only two places which we can suppose to have been anciently occupied by towns: one is Skalanova; the other is half-way between Skalanova and Tshangli; where, in a valley watered by a stream, is a source of hot water, near the ruins of a fortress, which, although it appears to have been a work of the Lower Greek Empire, contains some remains of an earlier age. This latter I take to be the site of Neapolis, which the Ephesii built, and afterwards exchanged with the Samii; and Skalanova stands probably on the ancient Marathesium."

William Martin Leake, Journal of a tour in Asia Minor, page 261. John Murray, London, 1824. At the Internet Archive.

Other scholars, including the archaeologist and traveller Charles Fellows, identified Neapolis with Tshangli or Changli itself.

Charles Fellows, A Journal written during an Excursion in Asia Minor, 1838, page 271. John Murray, London, 1839. At the Internet Archive.

13. Xenophon and Livy on Pygela

In his book Hellenica (Ἑλληνικά), Xenophon of Athens (Ξενοφῶν, circa 431-354 BC) described how in 409 BC the Athenian general Thrasyllos (Θράσυλλος, died 406 BC) sailed from Samos and attacked Pygela:

"In the next year - in which was celebrated [409 BC] the ninety-third Olympiad, when the newly added two-horse race was won by Euagoras of Elis and the stadium by Eubotas of Cyrene, Euarchippus being now ephor at Sparta and Euctemon archon at Athens – the Athenians fortified Thoricus; and Thrasyllus took the ships which had been voted him, equipped five thousand of his sailors so that he might employ them as peltasts also, and set sail at the beginning of the summer for Samos.

After remaining there for three days he sailed to Pygela; and there he laid waste the country and attacked the wall of the town. A force from Miletus, however, came to the aid of the Pygelans, and finding the Athenian light troops scattered, pursued them. Thereupon the peltasts and two companies of the hoplites came to the aid of their light troops and killed all but a few of the men from Miletus; they also captured about two hundred shields and set up a trophy."

Xenophon, Hellenica, Book 1, chapter 2, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

The mention of Pygela by Titus Livius (Livy, circa 64 BC - 17 AD) is even shorter. He mentioned only that during the Seleucid War (192-188 BC) between the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great (Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας, ruled 222-187 BC) and Rome, allied with Eumenes II of Pergamon, the Rhodian Polyxenidas (Πολυξενιδας), a general and admiral of Antiochus, halted his fleet for a day at Pygela on his way to attack Samos (190 BC):

"When all his preparations were made, Polyxenidas brought up the rowers from Magnesia by night and hastily launched the ships which had been beached. He remained there through the day not to complete his dispositions so much as to prevent the fleet from being seen when it left the harbour. Starting after sunset with seventy decked ships, he put into the port of Pygela before daybreak as the wind was against him. Remaining there for the day for the same reason - to escape observation - he set sail at night for the nearest point on Samian territory."

Titus Livius, The History of Rome, Book 37, chapter 11, sections 4-5. At Perseus Digital Library.

14. Phygela on an inscription from Ephesus

An honorary decree of the boule (council) and demos (people) of Ephesus for Melanthios Hermiou of Theangela (in Caria), who had been appointed by Lysimachus to command a garrison at Phygela, in the territory of Ephesus. Inscription IEph 1408. Dated around 294-289 BC.

The Greek text: epigraphy.packhum.org/text/247772. At the Packard Humanities Institute.

An English translation: Ephesos honours Melanthios of Theangela. At Attalus.

15. Pedanius Dioscorides on phygelites wine

Pedanius Dioscorides (Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, Pedanios Dioskourides; circa 40-90 AD), a Greek physician, botanist and pharmacologist from Anazarbus, Cilicia, southern Anatolia (Asia Minor), who served as a doctor in the Roman army. Around 50-70 AD he wrote Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, a 5-volume treatise on medicines and medicinal plants, usually referred to by its Latin title De Materia Medica (On medical material). Manuscripts of the work in Greek, Latin and Arabic, circulated around Europe and the Middle East, and remained an important medical reference throughout late Antiquity and the Medieval period.

In his discussion of the medical properties and effects of various wines, Dioscorides referred to wine from Phygela as "phygelites from Ephesus":

"The Lesbian wine [from Lesbos] is easily digested, lighter than the Chian wine [from Scios in the Aegean Sea] and good for the intestines. That which grows in Ephesus (called phygelites) has the same properties as this, but that from Asia (called messogites), from the mountain Tmolus, causes headaches and hurts the strength."

De Materia Medica, Book 5, chapter 10: Wines from different countries.

"Those without seawater (hard and white) are fitting for use in times of health. Of these the Italian wines excel, such as falernum, surrentinum, caecubum, signenan, many others from Campania, the praepian from the Adriatic coast, and the Sicilian called mamertinum. Of the Greek wines, there is the Chian [from Scios in the Aegean sea], the Lesbian wine [from Lesbos], and the phygelites from Ephesus."

De Materia Medica, Book 5, chapter 11: The effects of wines.

Tess Anne Osbaldeston and RPA Wood (editors), Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, Book 5, chapters 10-11, pages 749-750. After the translation from Latin by John Goodyer, 1655. Ibidis Press, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2000. At the Internet Archive.

The text in Greek and Latin in a 1548 edition: Pedakoiu Dioskoridou tou Anazarbeos Ta sozomena apanta..., Liber V, Cap. X et Cap. XI, page 329. At the Internet Archive.

16. Stephanus of Byzantium, the Suda and Michael Attaleiates on Pygela/Phygela and Marathesion

Stephanus of Byzantium (Στέφανος Βυζάντιος, 6th century AD), wrote a geographical dictionary known as Ethnika (Ἐθνικά), much of which was based on the works of earlier geographers, and which itself exists only as fragments in later works.

Marathesion: Μαραθήσιον, πόλις Καρίας. τὸ ἐθνικὸν Μαραθήσιοι ὡς Βυζάντιοι. ἔστι δὲ πόλις Ἐφεσίων.

Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, § M431.16. At ToposText.

Pygela: Πύγελα, πόλις Ἰωνίας. ὁ πολίτης Πυγελεύς.

Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, § P538.12. At ToposText.

The Suda (Σοῦδα), a Byzantine encyclopedia written in Greek in the 10th - 11th centuries AD (probably around 970 AD). Although the information in the Suda is largely culled from the works of ancient authors, many now lost, its reliability is often considered questionable.

Πύγελλα: Phygela, Phygella, Puygela, Pygella: [Pygella] a place, which we call Phygella; from where it is possible to make the ferry crossing to Crete.

Suda, pi.3107. At ToposText.

Πύγελα: Pygela: Pygela is a city in Ionia. [It is said] to have taken its name because some of those with Agamemnon remained there after they had had a disease of the buttocks [πυγαί].

Suda, pi.3109. At ToposText.

Michael Attaleiates (or Attaliates or Attaliota; Μιχαήλ Ἀτταλειάτης, circa 1022-1080) was a Byzantine judge, legal expert and historian who worked in Constantinople and provinces of the empire. His Historia, published around 1079-1080, is a political and military history of the Byzantine Empire between 1034 and 1079, dedicated to Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates (reigned 1078-1081).

He related a story in which the Byzantine general Nikephoros Phokas (circa 912-969; later Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas; Νικηφόρος Β΄ Φωκᾶς, reigned 963-969) stopped at Phygela with his large fleet of ships while on his way to attack the Arab forces occupying Crete (960 AD). He asked what the place was called, and interpreting the name to be a bad omen, he ordered all those aboard the ships to disembark and walk to a nearby harbour known as Hagias, so that the journey could begin there.

See:

Michael Attaliota, Historia (Bekkeri Editio), pages 23-24. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. Weber, Bonn, 1853. At Documenta Catholica Omnia.

William Mitchell Ramsay, The historical geography of Asia Minor, page 111, note 22 on Anea or Anaia, and note 23 on Attaliota's mention of Phygela. John Murray, London, 1890. At the Internet Archive. (See also note 5 above.)

17. Pseudo-Scylax on Ionian cities

Pseudo-Scylax (or Pseudo-Skylax) is the name commonly given to the author of The Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax (Περίπλους της θαλάσσης της οικουμένης Ευρώπης και Ασίας και Λιβύης, Circumnavigation of the seas of Europe, Asia and Libya), describing the sea route around the Mediterranean and Black Sea. The identity of the author is unknown, but he is thought to have written the work in or near Athens in the 4th century BC, perhaps around 330 BC. The name is due to the fact that the book was mistakenly attributed to the Greek geographer Skylax of Caryanda (Σκύλαξ ο Καρυανδεύς, late 6th early 5th century BC), whose lost works are known from citations by later Greek and Roman authors.

He listed locations along the Ionian coast from north to south: the Kaystros river, Ephesos, Marathesion (near Magnesia), Anaia, Panionion ... Mykale.

"I return to the mainland. Airai, a city with a harbour; Teos, a city with a harbour; Lebedos; Kolophon in the interior; Notion with a harbor; the sanctuary of Apollo Klarios; the Kaystros river; Ephesos with a harbor; Marathesion with, back on the mainland, Magnesia, a Hellenic city; Anaia, Panionion, Erasistratios, Charadrous, Phokaia(?), Akadamis, Mykale; these places are in the country of the Samians. In front of Mykale is Samos island, with a city and a closed harbor."

Pseudo-Scylax, Periplous, § 98. At ToposText.

18. The Tabula Peutingeriana

The Tabula Peutingeriana (also known as the Peutingerian Table or Peutinger Map), a 13th century map (itinerarium) on parchment, possibly based on an ancient Roman original. The original document is in the Austrian National Library (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) at the Hofburg palace, Vienna. |

|

|

Map, photos and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

Some of the information and photos in this guide to Kuşadası

originally appeared in 2004 on davidjohnberlin.de. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contributors | impressum | contents | sitemap |

| |